?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Smallholder farmers search for their product buyers in local spot market transactions. In spot market transactions, farmers will not be assured of ready markets for their production, or face volatile market prices. Similarly malt barley farmers used to face challenges of accessing input, farm technology, credit, and information that undermine their livelihoods. Vertically coordinated malt barley supply chain is evolving fast in Ethiopia. The purpose of this study was to analyze nexus between vertical coordination and level of malt barley commercialization in the study area. This study has been conducted in four districts of Arsi highlands known for their malt barley production potentials and presence of active supply chain coordination. A three-stage sampling procedure was employed to collect data using interview schedule from 384 (190 contract and 194 non-contract) randomly selected malt barley farmers. Descriptive statistics and Tobit regression model used to analyze farmer and farm-related factors vis-à-vis vertical coordination and level and determinants of commercialization farm households. Accordingly, the study identified that 11.05% of the respondents had <30% level of commercialization, when 55% were in between 30% and 65% and the rest, 34.21% of sampled malt barley farm households had more than 65% level of malt barley commercialization. Tobit regression revealed that farm size, yield, price, quantity of fertilizer applied, contract agreements, mobile phone ownership and access to credit were determinants of level of malt barley commercialization. Thus, endeavors of malt barley commercialization have to focus on improving access to technology, credit, extension, and organizing farmers in contract farming among others.

1. Introduction

Although agricultural commercialization was anticipated to catalyze increased agricultural productivity, farmers’ incomes and rural livelihoods as stated by Timmer (Citation1997) and Hazell (Citation2005), it was not the case for Africa. Hence, meeting challenges of increasing rural incomes and livelihoods in Africa requires tangible transformations from subsistence, low-input and low-productivity agriculture to high-input and high productivity and commercially oriented production (Aderemi et al., Citation2014). Since subsistence farming entails inefficiency and nonviable to ensure sustainable access to food and fiber in the long run, agricultural development efforts pooled towards smallholder commercialization, thereby enhance productivity, income and food security and poverty reduction (Pingali et al., Citation2005; Zhou et al., Citation2013).

Similar to other countries in Africa, Ethiopia also faces the challenges of low agricultural productivity, high incidences of poverty and food insecurity mainly in rural areas for years. Thus, commercial transformation of subsistence agriculture is central to Ethiopia’s economic, social and political development directions to deal with poverty and food insecurity. Accordingly, investments in agricultural services, credit, and input supply have been directed to those effects over several years (Admassie et al., Citation2016; Lulit et al., Citation2016). Despite such noteworthy efforts, the levels of commercial oriented agricultural production remain unsatisfactory in the country given the available potentials. Instances of under performance of commercial supply chains of wheat (bread and durum), cotton, soy-bean, vegetables and fruits (Shiferaw et al., Citation2014).

In Ethiopia, more than 4 million smallholder farmers pursue their livelihoods from the barley sub-sector. Barley production in Ethiopia comprises food barley that is produced both for self-consumption and market; while malt barley is produced mainly for malt in brewing industries (Alemu et al., Citation2015). Rashid et al. (Citation2015) revealed bottlenecks surrounding both food and malt barley production and marketing. These include complex production system, marketing and financial constraints, and high transaction costs to access inputs, information, new technology and markets among others. As a result, local supply does not satisfy more than half of the total malt requirements and the deficits are being filled by importing. Following the privatization of the state enterprises (including breweries and malt factories) brewing and malting companies have upgraded their production potentials and that have also intensified demand for malt.

Cognizant of this, several efforts have been put in place to exploit malt barley production potentials to make the country self-reliant from local supply. The efforts led to emergence of vertically coordinated malt barley supply chain through contractual arrangements that involve collaboration of key actors that include farmers, breweries, malt factories, cooperatives/unions, research institutions, agricultural offices, micro-finance institutions, and seed enterprises each with defined interests, roles and responsibilities. However, little is known about how the collaboration and coordination of malt barley actors enhance the level and address factors that determine of malt barley commercialization process in the study area. Accordingly, the study was proposed to specify levels and determinants of smallholder malt barley commercialization in vertically coordinated supply chain perspective in Arsi highlands of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. To that end, the study objectives sought to: (1) measure levels of malt barley output commercialization, and (2) reveal the determinants of malt barley commercialization.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical perspectives

High transaction costs and market imperfections constrain most of smallholder farmers’ access to technology and output markets, thereby impairing their productivity and livelihood outcomes. The need to address constraints of agricultural input and out market imperfections drives the emergence of agricultural product supply coordination mechanisms. Contract farming is an institutional arrangement promoted as a tool to organize vertical coordination in agricultural value chain, notably between producers and buyers. Various schools of thought guide firm behavior, property rights, and agency behavior form the theoretical underpinnings of contract farming. But the more dominant theoretical framework is transaction cost economics (TCE), which evolved from the seminal works of Coase (Citation1937) and Williamson (Citation1989). TCE has been expounded on by the proponents of the New Institutional Economics (NIE) School, which recognizes the vital role of the social and legal norms and rules underlying economic activities. TCE asserts that economic agents are rationally bounded and tend to be opportunistic. These conditions give way to market transactions that involve risks and perils, the mitigation of which would entail transaction costs. The degree of transaction costs depends on the transaction characteristics of uncertainty, asset specificity, and frequency of exchange. When these transaction characteristics entail costs that are prohibitive to engage in direct market exchange (i.e., spot markets), the firm will find it more efficient to vertically integrate—that is, to undertake the production of the good that it needs for its own economic activity. In between the extremes of spot markets and vertical integration are “hybrids” of transaction organization options, such as contract farming. The firm will then choose the organization that minimizes transaction costs. Although the TCE approach to explaining contracts is not without criticism, it remains the dominant approach used for this study to investigate the contract-farming in coordination of smallholder agriculture and their process of commercialization.

2.2. Empirical literature

Several studies on contract farming effects have been identified in Ethiopia. Google and Google Scholar searches undertaken to get recent studies conducted since 2015 onwards in Ethiopia. The research assessed based on location, method and results vis-à-vis the current study.

Studies on different effects of contract farming participation show emergence and expansions of contract farming arrangements in African including Ethiopia as institutional mechanizes to address financial, inputs and output market failures. Larger proportions of the studies come up with positive contribution of contract farming participation on farm household income as compared to non-contract comparison groups. Limited numbers of studies are obtained that found contract farming positively influence farm household food security through shortening the length of hunger period over the year as compared to non-contract farming households. In Ethiopia commercial transformation of subsistence agriculture has been overriding policy agenda, though there is little empirical evidence on the extent to which contract farming determine the process of smallholder commercialization, including malt barely farm households in the study area. Thus, this study is proposed to fill this knowledge gap on the effect of contract farming on the level of smallholder malt barley farmers’ commercialization.

3. Methodology

3.1. Descrition of the study area

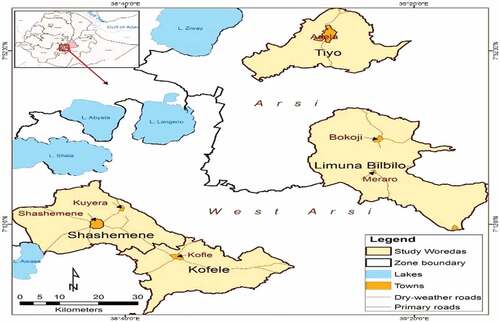

The study was conducted in Tiyyo and Limu Bilbilo districts of the Arsi zone and Kofele and Shashemene districts of west Arsi zones of Oromia Region, Ethiopia respectively Figure . Astronomically the zones lies between 7°08ʹ58” N—8°49ʹ00” N latitude and 38°41ʹ55” E—40°43ʹ56” E longitude where the study areas receive mean rainfall from 1020 mm to 1300 mm per annum. The study area presents suitable climatic and edaphic factors for agricultural production. The major annual crops grown in the two zones include, but are not limited to, wheat, barley (food and malt), bean, pea, maize, teff, sorghum, oats, chickpea, nueg, linseed millet, potato, and other vegetables (Oromia Finance and Economic Development Bureau (OFEDB), Citation2019).

Figure 1. Map of the study area (Arsi and west Arsi zones).

3.2. Data sources and sampling procedure

A cross-sectional household survey was used to collect data for this study. A multistage sampling procedure was employed in the selection of the sampled malt barley farmers. In the first stage, four districts were purposively selected owing to their malt barley production potentials. In the second stage, using a list of major malt barley producer KebelesFootnote1 within the selected districts, two Kebeles were randomly selected making 8 Kebeles in the total study. In the third and final stage, sample farm households were selected by a simple random sampling technique. To determine the sample size, the formula given by Kothari (Citation2004) was used as EquationEq. 1(1)

(1) .

Where n is the sample size needed, Z is the inverse of the standard cumulative distribution that corresponds to the level of confidence, e is the desired level of precision, p is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population and q = 1-p. The value of Z is found from the statistical table, which contains the area under the normal curve of 95% confidence level and p = 0.5 is as suggested by Kothari (Citation2004). Based on this, a total of 384 households were selected for the study from the four selected districts and assuming a 95% confidence level and ± 5% precision; q = 1-p; and N is the size of the total population from which the sample was drawn. Finally, a sample of 384 farm household heads was selected from eight Kebeles by simple random sampling with probability proportional to size (Table ).

Table 1. Effects of contract farming participation on farm household livelihoods

3.3. Analytical techniques

Combinations of analytical tools were utilized to analyze the data. These include descriptive statistics, Household Commercialization Index (HCI) and Tobit regression model.

3.4. Household commercialization index (HCI)

We employed the household commercialization index (HCI) to determine a household-specific level of malt barley commercialization (Govereh et al., Citation1999; Strasberg et al., Citation1999). That is HCI was modified to estimate the level of malt barley commercialization index (MBCI). The index measures the ratio of the gross value of malt barley sales by household i in year j to the gross value of all-malt barley produced by the same household i in the same year j in percentage as specified:

Where is the

household commercialization index for malt barley; the numerator is the total amount of malt barley sold by the

household in the

year (j = 2018/19 cropping season) and the denominator is the total value of the output of malt barley by the

household in the

year. The index measures the extent to which household crop production is oriented toward the market. A value of zero would signify a subsistence-oriented household and the closer the index is to 100, the higher the degree of commercialization. The advantage of this approach is that commercialization is treated as a continuum thereby avoiding a crude distinction between “commercialized” and “non-commercialized” households. Table presents t-test comparisons of means for HCI vis-a-vis socioeconomic and institutional factors were done using STATA 14.

Table 2. Selected study districts, Kebeles and sample household sizes (hhs)

3.5. Tobit model

Tobit /censored normal regression model was employed to identify the factors that determine the level of output commercialization of smallholder malt barley farmers. The Tobit model is the most common censored regression model appropriate for analyzing dependent variables with upper or lower limits (Abu, Citation2015; Liu & Wu, Citation2013). A Tobit model answers both questions of factors influencing the decision to commercialize and the extent of commercialization, as it assumes that both decisions are affected by the same set of variables (Alene et al., Citation2008; Buke, Citation2009). We employed a Tobit model because the dependent variables (output commercialization index) are truncated as latent variables. In this case, the dependent variable HCI is lower censored at 0 and the upper censored at 100 as it can only take values between 0 and 100. Subsistence farmers who sell none of their output would have a 0 HCI; on the other hand, farmers who sell all their output would have an HCI of 100 and are regarded as fully commercialized. The Tobit model avoids bundling of farmers into either commercialized or non-commercialized, since such discrete distinctions do not exist as farmers have diversified cropping patterns. The Tobit or censored normal regression model assumes that the observed dependent variables for observations j = 1, …, n satisfy:

Where the ’s are latent variables generated by the classical linear regression model:

Where denotes the vector of regressors, possibly including 1 for the intercept, and

the corresponding vector of parameters. The model errors

are assumed to be independently normally distributed:

. An observation of 0ʹs on the dependent variable could mean either a “true” 0 or censored data or

would always equal

and the true model would be linear regression and not Tobit.

Tobit model parameters do not directly correspond to changes in the dependent variable brought about by changes in independent variables. According to Greene (Citation2003), the marginal effect on the intensity of market participation due to changes in the explanatory variable is given as:

Following from the above discussion, the empirical Tobit model to estimate the determinants of the level of malt barley commercialization specified below computed using STATA 14:

3.6. Explanatory variables

The study builds on empirical evidence of market participation decisions under transaction costs for specific crops as influenced by household characteristics and resource endowment (Umar, Citation2013; Zamasiya et al., Citation2014). To measure the level of commercialization, the following variables are considered in consultation with related empirical studies. The variables include: sex, age and education of the household head, household size, household assets endowment including number of cattle, off-farm income, farm size and proximity to different agricultural services, etc.

Table summarizes variables with hypothesized influences on commercialization levels of smallholder malt barley farmers. It was expected that the higher the household size, the greater the chances of a household being involved in commercialization due to increased labor supply which may be needed for the cultivation of cash crops. The age of the household head was expected to have either a positive or a negative effect on commercialization (Kabiti et al., Citation2016). The age of the farmer could be associated with increased farming experience. As farmers become increasingly experienced they may have increased access to marketing information. On the other hand, elderly people may be more risk-averse than their younger counterparts, and may not be willing to partake in market-oriented production (Kamoyo et al., Citation2015). Studies have shown that the gender of the household head determines market orientation. For instance, Osmani and Hossain (Citation2015) noted that male participants were found to be more marketed-oriented compared to the female counterparts.

Resource ownership, such as cattle and cultivated land, is expected to influence commercialization positively. This is because availability of more land for cultivation would allow farmers to grow more crops and generate surpluses, which would increase the chances of commercialization. For instance, Abafita et al. (Citation2016) and Gutu (Citation2016) observed that the commercialization level of smallholder farmers increased with an increase in total cultivated land. Martey et al. (Citation2012) also revealed that access to credit is expected to link farmers with modern technology, ease liquidity and input supply constraints, thus increasing productivity and market participation. That is, farmers with better access to finance are more likely to commercialize than those without access to credit. Similarly, access to markets positively influenced the commercialization of smallholders (Ademe et al., Citation2017; Ayele et al., Citation2020). Accesses to extension services are expected to increase the productivity of cash crops, thereby resulting in higher commercialization (David et al., Citation2011). Ahmed and Mesfin (Citation2017) also revealed that membership in different commodity producer or marketing groups enhanced farmers’ capacity to exchange agricultural production and marketing information; thus, it is expected that farmers who belong to producer or marketing groups are in a better position to commercialize than non-members.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics

Demographic and socioeconomics characteristics of the randomly sampled 384 farm households are presented in this section (Table ). Age of the household heads ranged from 23 to 80 years, the average age of these respondents was 44.50 years indicating that more of the sampled households’ are of economically active stage. Ninety five percent of the sampled respondents are married; while the rest are divorced, widowed or single ones. The average family size of the farm household was 7.33 persons, which is larger than the national average of 4.60 persons per-household size (CSA (Central Statistical Agency), Citation2018). The higher the household size, the greater the chances of a household being involved in commercialization due to increased labor supply for more malt barley production. On average, household heads had 6.10 years of schooling, which indicates that farmers can at least read and write farm activity-related information, an important factor in the process of agricultural commercialization.

Table 3. Description of variables and hypothesized influence on malt barley volume of sales

HCrops production and livestock husbandry covered 92% of the farm households’ livelihoods while some others pursued non-farm sources of livelihoods including salary jobs and petty trades among others. The average landholding size with certification is 1.86 hectares, in addition 34% of the respondents also were involved in renting-in land or sharecropped in activities to access more land in the study period. The mean landholding size is an indicator of the dominance of smallholder farmers in the study area. Recently, malt barley contract farming is unfolding fast in the study areas. The average, minimum, maximum and standard deviation of malt barley farming experience of the household head were 6, 1, 4.90, and 24 years with and without contract farming. We did not include experience of farming in the model as it is highly correlated with a respondent’s age. The study household’s livestock husbandry comprised cattle, sheep, goat, horse, donkey, mule, poultry and beekeeping to some extent. Household-level livestock holding was calculated by using the Tropical Livestock Unit (TLU) and the average was 7.30.

Farm households walked on average 60.36 minutes to arrive at the nearest main market and 26.74 minutes to reach the all-weather road. Distance variables are usually proxies of transaction costs in either accessing information or markets, hence are most likely to reduce the uptake of improved agricultural technologies. More than half of the household heads (53.10%) are active members of the farmer association of primary cooperatives. Access to credit seemed one of the major constraints faced by the households as the survey disclosed that there was a quite low accounting; only 14.80% borrowed money from formal or informal sources during the study period. The average farm size planted to malt barley was 0.76 ha, whereas the maximum area cultivated was 5 ha. From average per capita landholding size of the farm households’, malt barley covered only 40% of the total land; that implies that farmers are engaged in a mixed cropping system. The allocated land does not suffice to commercial orientation as Woldemariam et al. (Citation2019) revealed the new malt barley varieties combine well with local teff grain for preparation of quality injera, the traditional Ethiopian flatbread that is a popular staple food.

Dummy variables such as sex, access to credit, access to extension services, contract agreements, access to training, access to improved seeds, ownership of mobile phones among others and the associated influence on the mean HCI were tested by t-statistic as results are presented in Table . Regarding sex of the sampled farm household heads, 95% were male while 5% were female. The result indicated that about 15%, 76% and 96% of the sampled household heads had access to credit, market information and use of improved seeds for malt barley production, respectively. The t-test statistics showed access to credit, market information, improve seed, and mobile ownership significantly affected the mean HCIs (p < 0.05), among others.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of continuous variables (n = 384)

4.2. Level of malt barley commercialization

The level of malt barley commercialization was associated with the volume of total production and quantity of household consumption. Table presents the summary of the malt barley produced, sold, consumed, stored or gifted otherwise by farm households during the study period. At the household level, the mean quantity of malt barley produced was 27.29 qt, out of which 13.568.22 qt was consumed and 17.95 qt was sold. In the survey period, on average 1qt of malt barley was sold for 1452.70 Birr (1 US$ = 28.00 Ethiopian Birr during the survey period).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of categorical variables (n = 384)

Table shows the distribution of respondents according to their HCIs. The HCIs of the respondents ranged from 0–99.16%. Further analysis revealed that 11.05% of the respondents had <30% HCIs, implying that such a farmer’s category falls in a low level of commercialization. While about 55% of the respondents are categorized as a medium level of commercialization by supplying between 30% and 65% of their production. While only 34.21% of sampled malt barley farm households were categorized in a highly commercialized level by supplying more than 65% of their production. The mean malt barley commercialization level was 58.19%, which implies that there was a gap of 41.81% to attain full commercialization level in malt barley production. The gap observed in the commercialization of malt barley implies that malt barley producing farm households are either not utilizing malt barley commercialization potential or there are impediments to be addressed. The 41.81% deficit in the level of malt barley commercialization could have been appropriated to consumption, seed stock or gift to others during the study year at least.

Table 6. Average malt barley produced, consumed or stored and sold (384)

4.3. Determinants of commercialization of smallholder malt barley production

Tobit regression model was used to estimate determinants of malt barley commercialization. Variables examined (i.e., total landholding size, malt barley farm size, average price, the quantity of fertilizer applied, contract agreements, mobile ownership, number of crops grown, cultivated land, malt barley selling price, amount of fertilizer use, and access to credit) were found significant at various probability levels influencing malt barley commercialization levels (Table ). Variables such as sex, age, educational status, household size, and distance to market, livestock holding (TLU) and off-farm income were not significant.

Table 7. Distribution of respondents by level commercialization (384)

Tobit regression (Table ) below revealed that malt barley farm size (ha) was statistically significant at (p < 0.1) and with a positive influence on commercialization level. It was in line with theoretical expectations. Moreover, the marginal effects of the Tobit prediction indicated that an increase in malt barley farm size by 1 unit will lead to 535% point increment in the level of malt barley commercialization. However, given existing population pressures, land degradation and climate change, pushing crop production area further will be difficult. Hertel (Citation2011) and Headey et al. (Citation2014) suggest that productivity growth on existing farmland ease both demands for new farmland being brought into production and help to conserve remaining resources.

Table 8. Parameter estimates of Tobit model for commercialization index

Yield, positively and significantly (p < 0.05), influenced malt barley commercialization. The result indicated that a unit increase in malt barley yield would lead to a 24.60% point increase in the proportion of malt barley output sold. Assuming that other factors are fulfilled, an increase in farm yield to maximum potential will also increase the marketable surplus, and thus lead to more commercialization. In this regard, several studies revealed that technology adoption tends to increase agricultural productivity and agricultural productivity influences farmers’ tendency toward market participation (Ahmed & Mesfin, Citation2017; Malumfashi & Kwara, Citation2013). Also, Rios et al. (Citation2009) see the presence of a bidirectional relationship between agricultural commercialization and farm productivity, as an increase in productivity raises households’ marketable surplus and leads to a higher level of commercialization while the reverse holds false.

The variable unit price of malt barley was statistically significant (p < 0.01) with a positive sign. It indicates that the better price malt barley farmers are offered the more their malt barley production is oriented towards the market. The finding is in line with the assertion of economic theory that output price is an incentive for farm households to supply more products for sale. That is also consistent with the finding of Muriithi and Matz (Citation2015) that price was an incentive for sellers to supply more quantity of vegetables to markets. The quantity of fertilizer applied was significant (p < 0.01) with a positive coefficient. Moreover, the marginal linear prediction effect of the Tobit regression shows that increasing fertilizer application by one unit would have increased the level of malt barley commercialization by 17.34%. One of the pathways by which fertilizers affect farmers’ commercialization is through increased yield advantage in return to investment in land and labor (Headey et al., Citation2014). It is widely recognized that modern agricultural technologies are critical for improving smallholder agricultural productivity.

Contract agreements was found to significant (p < 0.1) with a positive coefficient. The implication is that a farm household with prior malt barley contract farming significantly high level of commercialization than the non-contract counterpart. This finding is in line with previous studies of Dubbert et al. (Citation2019), Khapayi et al. (Citation2018) and Ayele et al. (Citation2020).

Mobile phone ownership was statistically significant (p < 0.05) with a positive coefficient. It implies that owning a mobile phone increases the level of malt barley commercialization. Lack of access to market information is used to constrain agricultural technology adoption, intensification and commercialization of smallholders in Africa (Michelson, Citation2013; Muriithi & Matz, Citation2015). This finding is also in line with findings of Martey et al. (Citation2012).

Number of extension visit was statistically significant (p < 0.01) with positive sign. It implies that as the number of visits increase, so does the level of malt barley commercialization. This may reflect that extension visits provide farmers with new knowledge and skill for enhancing both malt barley production and market supply. The finding is consistent with established fact that access to extension services improves farmers’ production, processing and marketing knowhow.

Access to credit was significantly and positively associated with the level of commercialization (p < 0.01). The finding was both consistent with the expectation and previous studies of Carletto et al. (Citation2011) and Martey et al. (Citation2012). The notion is access to credit increases the farmers’ capacity to purchase inputs (improved seeds, fertilizer, and agrochemicals), pay wages among others and that lead to increased agricultural productivity and better commercialization.

Total landholding size was found statistically significant (p = 0.01) with a negative coefficient. The implication is that as farmer’s total landholding size increases, the lesser would be the level of commercialization. This did not satisfy the hypothesized sign as it was anticipated that as a farmer bring more land under cultivation he or she would have been in a better situation to attempt commercialization. The possible reason for the negative effect could be as farmers get more and more land, they would allocate it for other competing crops. The study areas are known to be geographically amenable for commercial crops production, including wheat, bean and pea, among others. Although total landholding size has a negative effect on malt barley commercialization, the farm size allocated for malt barley maintained its expected positive effects on level of malt barley commercialization. This result is consistent with findings of Ademe et al. (Citation2017) and Dube and Guveya (Citation2016).

5. Conclusions and recommendations

Both descriptive statistics and econometric analysis were used to reveal levels and determinants of commercialization of malt barley essentially from the output side. The results from the descriptive analysis revealed that on average 58.19% of malt barley produced was sold. In terms of levels of commercialization, 11.05%, 54.74% and 34.21% of malt barley farm households were categorized as low, medium and high level commercial farmers. On the basis of these evidences, it can be deduced that malt barley is found at a medium level of commercialization.

The Tobit regression model revealed the significant variables that positively influenced malt barley commercialization, included: farm size, yield, and price, the quantity of fertilizer applied, contract agreements, mobile phone ownership and access to credit at a varying levels of significance. While malt barley output commercialization was significantly but negatively influenced by total landholding size and the constant term.

The findings of this study suggest that future interventions that intend to increase malt barley commercialization to a higher level need to take each significant variable into account in malt barley producing parts of the country in general, and the study area in particular. Accordingly, the study highlights the following recommendations:

The malt barley farm size significantly and positively determined malt barley level of commercialization. In line with established evidences of land shortage, population growth, the result implies that intensifying farming practices through use of improved production technology and management practices recommended to boost malt barley commercialization than seeking additional land for cultivation will be unlikely.

Yield also determined the level of malt barley commercialization significantly and positively. Yield is a function of several factors including the adoption of technologies, such as the use of improved varieties, different agrochemicals and integrated soil management practices, among others. Thus, agricultural services like extension advices and input sourcing and provisioning must focus on malt barley yield increasing packages.

Commonly, farmers are price responsive and the same is observed also in this study that price significantly and positively determined malt barley commercialization. This effect is more pronounced when the demand for the products increases. Thus, enhancing the level of commercialization and its sustainability rely on shortening malt barley supply chains so that transaction costs will be minimized and products will be exchanged with reasonable prices.

Given the positive and significant effects of contract farming on malt barley level of commercialization, contract farming and its associated benefits should be promoted to enhance the commercialization and livelihoods of smallholder malt barley farmers in the study area.

In the end, the variables of mobile phone ownership and credit significantly and positively determined the level of malt barley commercialization. Studies reveal having mobile and credit allow farmers to solve constraints of accessing market information and technology use imperfections respectively. Thus, the findings of the study note that increased facilitation access to alternative mobile phone, mobile information and communication technologies and credit services need to be considered to elevate the level of malt barley commercialization and rural livelihoods transformation at large.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Kebele is the lowest administrative unit in Ethiopia

References

- Abafita, J., Atkinson, J., & Kim, C. (2016). Smallholder commercialization in Ethiopia: Market orientation and participation. International Food Research Journal, 23(4), 1797–17.

- Abu, B. (2015). Groundnut market participation in the upper west region of Ghana. Ghana Journal of Development Studies, 12(1), 106–124. https://doi.org/10.4314/gjds.v12i1-2.7

- Ademe, A., Belaineh, L., Jema, H., & Degye, G. (2017). Smallholder farmers’ crop commercialization in the highlands of eastern Ethiopia. Review of Agricultural & Applied Economics, 20(2), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.15414/raae.2017.20.02.30-37

- Aderemi, E. O., Omonona, B. T., Yusuf, S. A., & Oni, O. A. (2014). Determinants of output commercialization among crop farming households in south western Nigeria. American Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research, 1(4), 23–27.

- Admassie, A., Berhanu, K., & Admasie, A. (2016). Employment creation in agriculture and agro‐industries in the context of political economy and settlements analysis. In Partnership for African social and governance research working paper no. Vol. 016.

- Ahmed, M., & Mesfin, H. (2017). Agricultural and Food Economics. SpringerOpen. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

- Alemu, D., Guinan, A., & Hermanson, J. (2021). Contract farming, cooperatives and challenges of side selling: Malt barley value-chain development in Ethiopia. Development in Practice, 31(4), 496–510.

- Alemu, D., Lakew, B., Kelemu, K., & Bezabih, A. (2015). Increasing the income of malt barley farmers in Ethiopia through more effective cooperative management. Research reported to selfhelp Afica. P.O.Box 1204, Addis Ababa.

- Alene, A. D., Manyong, V. M., Omanya, G., Mignouna, H. D., Bokanga, M., & Odhiambo, G. (2008). Smallholder market participation under transactions costs: Maize supply and fertilizer demand in Kenya. Food Policy, 33(4), 318–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.12.001

- Ayele, S., Thorpe, J., Ayele, G., Chingaipe, H., Teye, J. K., & O’Flynn, P. (2020). Agribusiness investment in agricultural commercialization: Rethinking policy incentives in Africa. In Working Paper (Vol. 33). Future Agricultures Consortium.

- Bezabeh, A., Beyene, F., Haji, J., & Lemma, T. (2020). Impact of contract farming on income of smallholder malt barley farmers in Arsi and West Arsi zones of Oromia region, Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1), 1834662.

- Buke, W. J. (2009). Fitting and interpreting Cragg’s Tobit alternative using Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(4), 584–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900405

- Carletto, C., Kilic, T., & Kirk, A. (2011). Nontraditional crops, traditional constraints: The long-term welfare impacts of export crop adoption among Guatemalan smallholders. Agricultural Economics, 42(Suppl. 1), 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2011.00552.x

- Coase, R. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 4(16), 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x

- CSA (Central Statistical Agency). (2018). the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia central statistical agency agricultural sample survey report on area and production of major crops statistical bulletin. 2016/2017.

- David, J. S., Dawit, K., & Dawit, A. (2011). Seed, fertilizer, and agricultural extension in Ethiopia. Ethiopia strategy support program II (ESSP II). ESSP II working Paper 020.

- Dubbert, C., Mabaya, E., Waithaka, M., & Wanzala-Mlobela, M. (2019). Participation in contract farming and farm performance: Insights from cashew farmers in Ghana. Agricultural Economics, 50(Suppl 1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12522

- Dube, L., & Guveya, E. (2016). Determinants of agriculture commercialization among smallholder farmers in manicaland and masvingo Provinces of Zimbabwe. Agricultural Science Research Journal, 6(8), 182–190. http://resjournals.com/journals/agricultural-science-research-journal.html

- Flores, M. (2017). Contract farming in Ethiopia: Concept and practice. AgriProFocus.

- Getachew, M., & Engdawork, A. (2019). The pursuit for enhancing the net income and sustainable livelihood for smallholder farmers: the case of contract farming in Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 21(4), 146–177.

- Girma, J., & Gardebroek, C. (2015). The impact of contracts on organic honey producers' incomes in south-western Ethiopia. Forest Policy and Economics, 50, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2014.08.001

- Govereh, J., Jayne, T. S., & Nyoro, J. (1999). Smallholder commercialization, interlinked markets and food crop productivity: Cross-country evidence in eastern and Southern Africa. http://www.aec.msu.edu/fs2/ag_transformation/atw_govereh

- Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric Analysis (Fifth ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Gutu, T. (2016). Commercialization of Smallholder Farmers in light of climate change and logistic challenges: Evidence from central Ethiopia. Global Journal of Economics and Business Administration, 1(1), 0001–0013.

- Hazell, P. B. (2005). Is there a future for small farms? Agricultural Economics, 32, 93–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0169-5150.2004.00016.x

- Headey, D., Dereje, M., & Taffesse, A. S. (2014). . Food Policy, 48(October), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.01.008

- Hertel, T. (2011). The global supply and demand for agricultural land in 2050: A perfect storm in the making? American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93(2), 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaq189

- Hirpesa, M., Legesse, B., Haji, J., & Bekele, K. (2021). Determinants of participation in contract farming among smallholder dairy farmers: The case of North Shewa Zone of Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia. Sustainable Agriculture Research, 10(526–2021–493), 10–19.

- Kabiti, H. M., Raidimi, N. E., Pfumayaramba, T. K., & Chauke, P. K. (2016). Determinants of agricultural commercialization among smallholder farmers in munyati resettlement area, Chikomba District, Zimbabwe. Journal of Human Ecology, 53(1), 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.2016.11906951

- Kamoyo, M., Muranda, Z., & Chikuya, T. (2015). Agricultural export crop participation, contract farming and rural livelihood in zimbabwe: The case of cotton farming in rushinga district. Journal of Economics and Finance, 6(6), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.9790/5933-0661110120

- Khapayi, M., van Niekerk, & Celliers, P. R. (2018). Agribusiness challenges to effectiveness of contract farming in commercialization of small-scale vegetable farmers in eastern cape, South Africa. J. Agribus. Rural Dev, 4(50), 375–384. http://dx.doi.org/10.17306/J.JARD.2018.00429

- Kothari, C. (2004). research methodology: methods and techniques (2nd ed.). Wisha, Prakasha.

- Liu, X. W., & Wu, Y. (2013). Group variable selection and estimation in the Tobit censored response model. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 60)80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2012.10.019

- Lulit, M., Bekele, S., Amarendra, S., & Sika, G. (2016). Economy-wide impacts of technological change in food staples in Ethiopia: A macro-micro approach. Working Paper 2016/17, Partnership for Economic Policy.

- Malumfashi, A. H., & Kwara, M. A. (2013). Agricultural commercialization and food security in Nigeria. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management & Social Science, 2(7).

- Martey, E., Ramatu, M., Al-Hassan, J. K., & Kuwornu, M. (2012). Commercialization of smallholder agriculture in Ghana: A Tobit regression analysis. African Journal of Agricultural Research, 7(14), 2131–2141. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR11.1743

- Mebrahatom, M. (2019). Small-Holder farmers' perception and willingness to participate in outgrowing scheme of sugarcane production: The case of farmers surrounding Wolkayet sugar development project in Ethiopia. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition & Development, 19(4).

- Michelson, H. C. (2013). Small Farmers, NGOs, and a Walmart World: Welfare effects of supermarkets operating in Nicaragua. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 95(3), 628–649. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aas139

- Mulatu, G., Haji, J., Legesse, B., & Ketema, M. (2017). Impact of participation in vegetables’ contract farming on household’s income in the Central Rift valley of Ethiopia. American Journal of Rural Development, 5(4), 90–96. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajrd-5-4-1

- Muriithi, B. W., & Matz, J. A. (2015). Welfare effects of vegetable commercialization: Evidence from smallholder producers in Kenya. Food Policy, 50(January), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2014.11.001

- Oromia Finance and Economic Development Bureau (OFEDB). (2019). Physical and socio economic profile of Arsi zone and districts. finfinne (Addis Ababa).

- Osmani, A. G., & Hossain, E. (2015). Market participation decision of smallholder farmers and its determinants in Bangladesh. Journal of Economics of Agriculture, 62(1), 163–179.

- Peter, H. (2005). The role of agriculture and small farms in economic development. paper presented at the workshop on ‘the future of small farms’ Organized by IFPRI, ODI and imperial college, London at the withersdane Conference Center, Wye, Kent, UK. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Pingali, P., Khwaja, Y., & Meijer, M. (2005). Commercializing small farms: Reducing transaction costs. ESA Working Paper/Agricultural and Development Economics Division, FAO, (05–08).

- Rashid, S., Gashaw, A., Solomon, L., James, W., Leulsegged, K., & Nicholas, M. (2015). The barley value chain in Ethiopia. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Rios, A. R., Masters, W. A., & Shively, G. E. (2009). Farm productivity and household market participation: Evidence from LSMS Data. Contributed paper prepared for presentation at the international association of agricultural economists conference, August, Beijing, China. http://ageconsearch.umn.edu

- Shiferaw, B., Kassie, M., Jaleta, M., & Yirga, C. (2014). Adoption of improved wheat varieties and impacts on household food security in Ethiopia. Food Policy, 44(February), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2013.09.012

- Strasberg, P. J., Jayne, T. S., Yamano, T., Nyoro, J., Karanja, D., & Strauss, J. (1999). Effects of agricultural commercialization on food crop input use and productivity in Kenya (pp. 71). Michigan State University International Development Working Papers.

- Tefera, D. A., & Bijman, J. (2021). Economics of contracts in African food systems: Evidence from the malt barley sector in Ethiopia. Agricultural and Food Economics, 9(1), 1–21.

- Timmer, C. (1997). Farmers and markets: the political economy of new paradigms. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 79(2), 621–627. https://doi.org/10.2307/1244161

- Umar, B. (2013). A critical review and reassessment of theories of smallholder decision making: A case of conservation agriculture households, Zambia. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 29(3), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170513000148

- Williamson, O. E. (1989). Chapter 3 Transaction cost economics. In R. Schmalensee & R. D. Willig (Eds.), Handbook of industrial organization, Elsevier B.V (pp. 135–182). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-448X(89)01006-X

- Woldemariam, F., Mohammed, A., Tadesse Fikre Teferra, T., Gebremedhin, H., & Yildiz, F. (2019). Optimization of amaranths–teff–barley flour blending ratios for better nutritional and sensory acceptability of injera. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 5(1), 1565079. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2019.1565079

- Zamasiya, B., Mango, N., Nyikahadzoi, K., & Siziba, S. (2014). Determinants of soybean market participation by smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(2), 49–58. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2013.0446

- Zhou, S., Minde, I., & Mtigwe, J. B. (2013). Smallholder agricultural commercialization for income growth and poverty alleviation in Southern Africa. Afr. J. Agric. Res, 8(22), 2599–2608. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJAR11.1040