Abstract

Access to basic financial services, though, enables destitute and vulnerable individuals in society to promote prosperity, a significant section of rural population is still unbanked in India. Unveiling various small saving schemes, the Indian Government has accelerated the financial inclusion, but the availability of numerous alternative schemes has created a surplus of market information, causing difficulty in building economic judgment for the rural people having no financial socialization through formal and informal education and training. While dismissive investors rely on their own decisions, the convincing behaviour of financial consultants may play a crucial role in shaping the saving habits of the preoccupied population. To analyse the moderation effect of financial consultants on the relationship between small savings schemes, financial literacy and behaviour, and savings habit of rural people, the empirical study employs a two-phase structural equation modelling on the data gathered from 343 adult respondents from 12 Indian districts with a considerable rural population. In order to validate the hypothesized measurement model, a confirmatory factor analysis is carried out and in the next phase, the structural model is used to verify the association between exogenous and endogenous variables. The study exhibits a significant positive impact of predictors and moderation variables on the savings habit. The study recommends integrating consultants into the financial engineering process to advance inclusivity and encourage saving behaviour of rural individuals for personal and economic prosperity.

1. Introduction

Financial inclusion can reduce poverty and promote prosperity. Financial inclusion is one of the panaceas to eradicate poverty from the world and to better the livelihood of people and as such reduces poverty. Also, financial inclusion is envisaged as very key in every economy because it is seen as an enabler to achieving 7 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) such as Eliminating extreme poverty (SDG 1); reducing hunger and promoting food security (SDG 2); achieving good health and well-being (SDG 3); fostering quality education (SDG 4); promoting gender equality (SDG 5); promoting shared economic growth (SDG 8); and promoting innovation and sustainable industrialization (SDG 9) (World Bank, Citation2018a). Given the fact that an inclusive financial system is linked to poverty reduction, prosperity, and promoting sustainable growth, a lower level of financial inclusion poses a challenge in achieving sustainable development goals and becomes a cause of concern for sustainable inclusive economic growth and development (Anthony Yaw et al., Citation2021).

Having access to financial services empowers poor people to save and to borrow, helping them to acquire assets, invest in education, and set up businesses that would enable them to improve their standards of living (Baidoo & Akoto, Citation2019; Sakyi et al., Citation2021). Indeed, financial inclusion is beneficial to less privileged people in rural areas of society, young people and women. Bakari et al. (Citation2019) examined the effect of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa and concluded that rural banking and affordable internet services are also pivotal in reducing poverty. Attempting to establish the relationship between financial inclusion and poverty alleviation in Indonesia, Taufiq et al. (Citation2019) revealed that financial inclusion has the tendency to reduce the probability of households from absolute poverty. Using 45,000 households in India, Sefa Awaworyi and Bhaskar Marisetty (Citation2020) empirically established a negative relationship between financial inclusion and poverty, implying that financial inclusion reduces poverty.

Though there is a consensus that access to basic financial services enables destitute and vulnerable individuals in society to move out of the vicious cycle of poverty and empower themselves and their families, yet 1.7 billion adults globally do not have a bank account, and 46% of these adults live in seven countries, namely China, India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Nigeria, Bangladesh, and Mexico (Grand Thornton, Citation2020). Approximately a quarter of the adult population without a bank account live in China and India. Most of the population globally who do not have access to essential financial services, such as a transaction account, savings, insurances, and credit, are young adults and women. Moreover, 30% of adults without a bank account are aged between 15 and 24 years (Grand Thornton, Citation2020).

Moreover, in countries with a low proportion of adults with a bank account, those without a bank account are even younger. For example, in India, Brazil, and Kenya, approximately 4 in 10 adults without a bank account are aged from 15 to 24 years (Grand Thornton, Citation2020). According to the Global Findex Report, a quarter of adults without a bank account reside in the poorest 20% of households in any economy (Grand Thornton, Citation2020). Even in economies where bank account ownership has expanded to two-thirds or more, poor adults account for a larger proportion of those without bank ownership. Women from poor households in rural areas or those out of the workforce represent approximately half of this population. The gender gap in bank account ownership remains at 9% in developing countries, hindering women from being able to effectively control their financial lives.

According to the Global Findex database 2017, India is ranked 50th, with 80% of its population having a bank account. The number of individuals with a bank account has exponentially increased in India since 2014 (Grand Thornton, Citation2020) mainly due to the launch of government schemes, especially small saving schemes for financial inclusion. Small savings schemes are a set of savings instruments managed by the central government to encourage citizens to save regularly irrespective of their age. These schemes are popular because they not only provide returns that are typically higher than those of bank fixed deposits but also ensure sovereign guarantee and tax benefits. But the availability of numerous schemes has created a surplus of market information related to savings alternatives, causing difficulty in building economic judgment (Elizabeth et al., Citation2019).

In Indian context, Kumar and Laha (Citation2012) and Gwalani et al. (Citation2014) advocate that a greater degree of awareness of basic financial products and service would be the primary step forward towards financial inclusion. Kumar and Laha (Citation2012) attempted measuring the inter-state variations in the access to finance using a composite index of financial inclusion. In their paper, they identified that a greater degree of awareness of basic banking services, diversification of rural non-farm sector, literacy drive to rural households, and an expansion of household-level assets play a crucial role in the process of financial inclusion. Gwalani et al. (Citation2014) found that expansion of bank branch network had little contribution to financial inclusion because of several social and economic barriers experienced by the rural poor including lack of promotion of financial products, such as savings bank account.

Family financial socialization through formal and informal education and training can have a substantial positive impact on financial behavior (Khawar & Sarwar, Citation2021). Adults without a bank account tend to have a low education level (Grand Thornton, Citation2020). In addition, literate household heads and individuals who are educated and employed are more likely to save compared with those who are illiterate and unemployed (Sakyi et al., Citation2021). Age and dependency ratio show insignificant impacts on household savings (Sakyi et al., Citation2021). Higher age, higher education, and higher asset values most often have positive impact savings, while larger number of dependents and secured public sector employment have an adverse impact on savings in the low-income economies like Ghana (Mumin et al., Citation2016).

The lack of formal education and financial literacy hinders the individuals in developing understanding about the institutions and their products. Beckmann and Salvatore Mare (Citation2017) using survey data from 10 emerging markets in central, eastern, and southeastern Europe show that financially literate individuals having trust in financial institutions increase the probability of having formal savings. Similarly, Baidoo et al. (Citation2018), using 600 individuals in Ghana, show that higher income, higher education level, being financially literate, and being employed increase the probability of saving at financial institutions.

In view of the factors like surplus market information, trust deficit between the financial institutions and low literate rural population, lack of awareness and promotion of financial products and services, the role of financial consultants is considered to be of paramount importance as they can be instrumental in reducing the information asymmetry and influence the household decision to save at financial institutions. Though Sofi and Hakim (Citation2018) in their study reveal that small savings scheme features, financial literacy, financial behavior, and financial consultants’ guidance are essential in shaping savings habits, the influence of a financial consultant has not, however, been the focus of many studies. Therefore, the present study attempts to examine the moderation effect of financial consultants on the relationship between small savings schemes, financial literacy and behavior, and savings habits.

2. Literature survey and theoretical framework

2.1. Small savings schemes and savings habit

Literature has shown that communities with access to savings instruments experience increased savings, productive investments, as well as increased consumption and female empowerment (Ashraf et al., Citation2010). Access to financial services also leads to poverty reduction, decrease in the level of inequality, and enhanced private investment and economic growth (Allen et al., Citation2016; Bruhn & Love, Citation2014). It is often argued that economic growth can only be sustained if a significant number of the population has greater access to formal financial services that is associated with high rate of savings, employment, and high-income and low-poverty rate (Ibrahim & Olasunkanmi, Citation2019; Nanziri, Citation2016). Therefore, small savings schemes are generally designed for small investors to mobilize and develop savings habits.

Small savings schemes are mostly developed for low-income groups in rural areas and financially backward urban communities (Ganapathi, Citation2010). Household savings in formal financial institutions work as capital for large corporations. In India, 65% of the population lives in rural areas, and the small savings of rural households become a large reservoir of capital that can be allocated to various needy sectors through formal financial institutions (World Bank, Citation2020). In India, all deposits received under various small savings schemes are pooled in the National Small Savings Fund. The money in the fund is used by the central government to finance its fiscal deficit.

The government has incorporated the financial engineering process by establishing various committees, such as the Malhotra Committee, Rangarajan Committee (1991), Gupta Committee (1998), and Dave Committee (1999), in different time periods to increase the attractiveness and competitiveness of small savings schemes. The schemes are divided into three types: post-office deposits, savings certificates, and social security schemes. Although few schemes provide a monthly return and tax benefits, social security schemes are designed for the betterment of female children and senior citizens and for providing a saving options for long-term goals, such as retirement. These time-tested and safe investment modes do not offer quick returns but are safer than market-linked schemes. Old-age requirements, tax benefits (i.e., those of the National Savings Certificate), safety, security, convenience, liquidity, and assured returns are some of the major attributes that attract people to invest in post offices for their progressive growth (Chawla & Joshi, Citation2021; Gavini & Athma, Citation1999; Mohanta & Debasish, Citation2011).

The majority of school teachers prefer to invest money to fulfil obligations, such as their children’s education and marriage needs, and purchase Kisan Vikas Patra (KVP), Indira Vikas Patra (IVP), and other popular time deposit schemes that cater to and function similar to commercial banks products (Prajapati et al., Citation2021). A survey of the National Council of Applied Economic Research (NCAER) of India indicated that the postal department contributes a significant proportion of total savings to the economy (Annual report NCAER-Citation2017-18) and results in a substantial increase in domestic savings habits (Soni et al., Citation2022). Because of the little contribution of bank branch networks to financial inclusion (Gwalani et al., Citation2014), the postal department is considered the backbone for developing the rural economy and acts as a crucial catalyst of communication (Anand, Citation2019; Velsamy & Amalorpavamary, Citation2015) for developing savings habit by offering different savings schemes with diverse features. Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Small savings schemes contribute to cultivating savings habits.

2.2. Financial literacy, behavior, and savings habit

Several economic theories including the absolute income hypothesis by John Maynard (Citation1936), relative income hypothesis by Duesenberry (Citation1949), permanent income hypothesis by Friedman (Citation1957), and life-cycle hypothesis by Ando and Modigliani (Citation1963) have been used in various literatures to explain the financial behaviours of individuals. But these classical theories focus primarily on earnings, income, and life cycle to explain what influences individuals’ saving and consumption behaviours and ignore several other demographic and individuals’ differences (Yeal & Jiang, Citation2019; Sakyi et al., Citation2021).

A section of literature on savings and reveal that women are less likely to have a defined retirement saving plan compared to men (Sunden Annika & Surrette, Citation1998) and women have different risk preferences as compared to men that influence their saving and spending decisions (Croson, Gneezy, Citation2009). Some researchers also observed that women are less financially informed than men, and the low financial literacy influences their level of saving (Lusardi & Mitchell, Citation2014). In addition, literate household heads and individuals who are educated and employed are more likely to save compared with those who are illiterate and unemployed. Age and dependency ratio show insignificant impacts on household savings (Sakyi et al., Citation2021).

Higher age, higher education, and higher asset values most often have positive impact on savings, while larger number of dependents and secured public sector employment have an adverse impact on savings in the low-income economies like Ghana (Mumin et al., Citation2016). Researchers across the world such as Shawn et al. (Citation2011) in Indonesia, Sadananda (Citation2011) in India, Miriam et al. (Citation2013) in Brazil, Mahdzan and Tabiani (Citation2013) in Malaysia, Tullio and Padula (Citation2013) in 11 countries of Europe, Lusardi (Citation2019) in the USA, Conrad and Mutsonziwa (Citation2017) in Zimbabwe, and Morgan and Long (Citation2020) in Laos have studied the impact of financial literacy on savings and found financial literacy was found to be a significant determinant of household savings.

Financial literacy plays a crucial role in making better economic decisions for the well-being and prosperity of individuals and enables individuals to grab the opportunity that arises in the market, and the maturity levels of investors in terms of their financial literacy and awareness are replicated in their savings and investment behavior (Roa et al., Citation2019). Insufficient awareness prevents people from saving a reasonable portion of their earnings and develops a negative behavioral approach toward savings. The financial literacy level is affected by demographic and socioeconomic factors (Lusardi, Citation2019). The financial literacy level of women is lower than that of men, and women fail to make crucial economic decisions at an appropriate time. However, they wish to maintain adequate liquid money to hedge their families against financial exposure and hardship (Netemeyer et al., Citation2018).

Education accomplishment has been shown to rise linearly in relation to consumption of financial services. This view is supported by Camara et al. (Citation2014) in their study with a nationally representative sample in Peru that found education to be playing a significant role in financial inclusion. Bogale et al. (Citation2017) examined the saving behavior of 325 rural households and revealed a positive relationship between age, income, education, and the probability of saving. Since individual saving benefits the entire nation at the macroeconomic level, implementing financial educational programmes to increase individuals’ financial literacy can be one of the avenues to boost national saving (Mahdzan & Tabiani, Citation2013). Mohammed Ahmar (Citation2020) in his exploratory study examining the effect of financial literacy on savings, advocates that it is important to increase financial literacy as it leads to more savings and thus helps in providing investment for the diversification of the Omani economy. Even Grohmann et al. (Citation2018) confirm that training is more effective in cultivating savings habits and elevating understanding of their own financial circumstances. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Financial literacy and financial behaviour contribute to stimulating savings habits.

2.3. Financial consultants and savings habit

Notwithstanding the importance of, mobilisation of savings by financial institutions, the institutional collapse makes households lose trust in saving their excess funds at those financial institutions. The trust deficit among savers and mobilizers is well documented by many researchers. Helmut (Citation2013) and Goldberg (Citation2014) in their studies found adoption of basic financial services such as saving in many developing countries is not noteworthy as households prefer to hold cash rather than saving in their formal bank account due to distrust and memories of past banking crises. The role of trust in economic decisions has been a key area of interest for many researchers like Adusei (Citation2013), Ajayi (Citation2016), Bachas et al. (Citation2016), Beckmann and Salvatore Mare (Citation2017), and Ogunleye and Ogunleye (Citation2017) who emphasized on boosting individuals’ trust in financial institutions to improve financial inclusion.

The first source of mistrust may be the institutions themselves that fall short on the performances and hesitate to disclose the full information to the public (Baidoo and Akoto, Citation2018). Consequently, if individuals cannot confidently rely on financial institutions due to inadequate information, then their decision to save with them will also be affected. The second source is the lack of formal education and financial literacy that hinder the individuals in developing understanding about the institutions and their products. Beckmann & Salvatore Mare (Citation2017) using survey data from 10 emerging markets in central, eastern, and southeastern Europe show that financially literate individuals having trust in financial institutions increase the probability of having formal savings. Similarly, Baidoo et al. (Citation2018), using 600 individuals in Ghana, show that higher income, higher education level, being financially literate, and being employed increase the probability of saving at financial institutions. Therefore, the role of financial consultants may be of paramount importance as the consultants can reduce the information asymmetry and influence the household decision to save at financial institutions.

People’s psychological, cultural, and emotional connections with money affect their financial behavior and are better explained by financial advisors in the event of financial assessment (Joo & Durri, Citation2018). Dismissive savers are more likely to change their advisors because they rely on their own savings behavior (Bartholomew & Horowitz, Citation1991), whereas preoccupied depositors are more likely to attach only through a detailed discussion on their investment objectives. Therefore, close contact with financial consultants removes inherent limitations and promotes savings behavior. Social penalties considerably affect the saving behavior of people because they are normally imposed when they fail to fulfil their financial obligations in time and are generally declared in a public forum by financial consultants (Breza & Chandrasekhar, Citation2019; Viswanathan et al., Citation2020).

Working women are conservative, and their savings behavior is higher than that of men. They save to ensure a better future and prefer small savings schemes to utilize their earnings effectively. The Indian postal system provides them with a better financial service by entering into nontraditional areas such as e-banking, e-governance, and e-commerce (García-Santillán et al., Citation2021). The social relationship of investors promotes commercial practices (Farzin et al., Citation2022), and when they encounter the decision of a large group, they exhibit herd behavior in terms of the decision-making process (Fromlet, Citation2001; Viswanathan et al., Citation2020). Most individuals obtain information on small savings schemes from their peers, relatives, and financial consultants and modify their decisions on the basis of situations they encounter because their decisions are not predefined (Gulcin & Regan, Citation2015).

In an agent-based framework, financial consultants influence people’s savings habits (Liu et al., Citation2020; Sorropago, Citation2014). Financial consultants can eliminate psychological obstacles, maintain superior customer relationships, and ensure client retention by meeting their multifaceted expectations (Sofi & Hakim, Citation2018). Better disclosure and secure connection eliminate negative concerns and create an optimistic and healthy investment atmosphere (Collins, Citation1996). Furthermore, the government has implemented various measures to improve financial literacy in communities and employed different learning approaches at different levels to bring them to the mainstream in the society (A. García-Santillán et al., Citation2021). Better financial decisions are made only by financially literate groups (Grohmann, Citation2018). Accordingly, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: Financial consultants moderate small savings schemes and individuals’ financial literacy and behavior, thus promoting savings habit

The research framework is presented in Figure .

3. Significance of the paper

The paper gains its importance by dealing with the moderation effect of financial consultants on the relationship between small savings schemes, financial literacy and behavior, and savings habits in underprivileged rural population of India. The financial decisions of people are affected by the structure of the financial service industry, information on intermediaries, and their performance (Brooke et al., Citation2017; Victor et al., Citation2018); service quality and social influence (Jagongo & Mutswenje, Citation2014; Viswanathan et al., Citation2020); referral marketing (i.e., word of mouth); and interpersonal communication, ease of use of information, and impact of herd behavior. As most of the low literate rural individuals are preoccupied investors who would be willing to save only through a detailed discussion with financial advisors regarding their financial objectives, the relationship between financial advisors and poor people in rural areas plays a vital role in making savings decisions (Sofi & Hakim, Citation2018).

The availability of numerous schemes has created a surplus of market information related to savings alternatives, causing difficulty in building economic judgment. The banks in rural India could not contribute much to financial inclusion because of lack of awareness and promotion of basic financial products and services such as savings bank account (Gwalani et al., Citation2014; Kumar & Laha, Citation2012). The role of financial consultants in creating awareness about availability and benefits of financial services is expected to improve inclusion, especially in low-income countries and low literature population.

The systemic collapse of five bad banks including a co-operative bank (Punjab and Maharashtra Co-operative bank) in three consecutive years between 2017 and 2020 has shaken the trust and faith of small savers in the financial institutions. About three lakh account holders lost their savings because of such collapses. The trust deficit among savers and mobilizers can be bridged by financial consultants. Since many other public sector banks are fundamentally strong, there is a need to emphasize on boosting individuals’ trust in financial institutions to improve financial inclusion. Many authors (Ajayi, Citation2016; Beckmann & Mare, Citation2017) presage the application of information asymmetry theory to explain the link between trust and decision-making and indicated the importance of communication and information-sharing in building trust. Since formal education indicator for rural households has remained a big challenge (Atkinson & Messy, Citation2013), the financial consultants can reduce the information asymmetry and influence the household decision to save at financial institutions.

4. Research methods

4.1. Research design

We proposed a structure to examine the predictors of investment decisions and the moderating role of a financial advisor in cultivating savings habits (Figure ). To determine the relationship between exogenous (small savings schemes and financial consultants) and endogenous (savings habit) variables, we used the descriptive research design by considering 12 Indian districts with a considerable proportion of the rural population with a low literacy rate.

4.2. Sample frame and data

In order to obtain the highest response rate, we employed the convenience sampling technique for data collection within a given time frame. Data were collected from 343 participants by using a 13-item 5-point Likert scale that shows 83% of response rate. Although 413 participants completed the survey, we included 343 participants after excluding those with missing values and wrong responses. To examine the reliability and validity of the survey, we conducted a pilot test among 30 respondents. The survey was observed to be adequate and satisfactory. The internal consistency of the survey was examined by calculating Cronbach’s alpha (Nunnally et al., Citation1978) and the observed values were >0.7, indicating the reliability of the instrument. Furthermore, scale reliability and validity were determined by performing exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The survey was used to examine people’s savings habits based on various parameters, and the responses were analyzed using SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 24.0.

4.3. Estimation techniques

With respect to the estimation technique, this study employs Structure Equation modelling (SEM), a powerful, multivariate technique found increasingly in scientific investigations to test and evaluate multivariate causal relationships. In order to measure and analyse the relationships between observed and latent variables, SEM is considered to be a powerful technique and preferred over the regression analysis for its ability to examine the linear causal relationship among the variables while simultaneously accounting for the measurement errors. A confirmatory test of the proposed measurement model is carried out using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

4.4. Scale reliability assessment

The systematic review of prior literature plays a centeral role for the enumeration of the constructs. The review helps in bringing together the theories, constructs and variables. Table presents the scale items with their theoretical background. The reliability of the scale is examined by determining Cronbach’s alpha, and the Cronbach’s alpha values of all exogenous variables presented in Table meets the cutoff value of 0.7 (Nunnally, Citation1978). The Cronbach’s alpha values of small savings schemes, financial consultants, financial literacy and behavior, and savings habits were 0.815, 0.778, 0.711, and 0.835, respectively. A questionnaire for data collection is reliable if the Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.7 and above, though higher alpha values indicate a higher internal consistency among the items on the questionnaire (Field, Citation2009). The high Cronbach’s alpha implies that if the questionnaire is administered again, then the survey responses received from the households would be the same or similar. For two-stage structural equation modelling (SEM) (Hair et al., Citation2013), we initially performed a confirmatory factor analysis to confirm the hypothesized measurement model. Subsequently, we constructed a structural model to validate the association between variables based on the proposed model. To eliminate the common method bias, we adopted Harmon’s single-factor method for factor analysis, which involved the application of the principal component method without any rotation. The extracted single factor explained 41.369% of the total variance (see Table ), which is within the acceptable limit (i.e., <50%). Therefore, a common method bias was excluded.

Table 1. Support for scale items and theoretical background

4.5. Exploratory factor analysis

Before examining the measurement model, we performed an exploratory factor analysis to examine the loads of measured variables (items) on their corresponding factors and to evaluate the association between measured variables and their corresponding factors. By performing the exploratory factor analysis, we extracted four factors, which explained 68.798% of the total variance (see Table A1). Furthermore, the adequacy of the samples for factor analysis was examined by performing Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity tests. We determined a value of 0.872 for KMO statistics (see Table A2), which is >0.50 as used in academic literature. While performing factor analysis in SPSS 24.0, we performed principal component extraction with the varimax rotation method and found an approximate chi-square value of 1618.925 with a degree of freedom of 78 (see Table ). We considered a 5% level of significance. The ceiling points of factor loadings and cross-loadings were determined [i.e., >0.5 (Karatepe et al., Citation2005) and >0.40 (Hair et al., Citation2010)], respectively, and used as an eigenvalue of >1 as the base. The factor loadings are listed in Table .

Table 2. Factor loadings

5. Results

5.1. Measurement model

The goodness-of-fit indices were calculated by performing a confirmatory factor analysis for all four latent constructs in a single model to assess their goodness of fit (Schreiber et al., Citation2006).

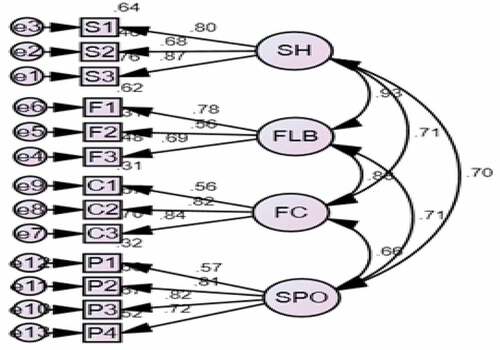

The values of the model fit indices (Table ) CMIN/DF = 2.169, GIF = 0.931, NFI = 0.928, CFI = 0.959, TLI = 0.942, AGFI = 0.901, and RMSEA = 0.071 were within tolerable ranges. The measurement model is presented in Figure .

Table 3. Measurement model fit indices

The construct soundness of the measurement model was measured by determining convergent and discriminant validity. The convergent validity was measured by calculating the average variance extracted (AVE) value, and the composite reliability (CR) was measured by examining the findings of the confirmatory factor analysis. The measurement model had an AVE of >0.5 and a CR of >0.7 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The outcomes of convergent and discriminant validity are presented in Tables , respectively. Diagonal discriminant values were larger than those of correlation values; thus, we validated the discriminant validity of the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 4. Test of convergent validity of measurement model

Table 5. Discriminant validity test of measurement model

5.2. Structural model

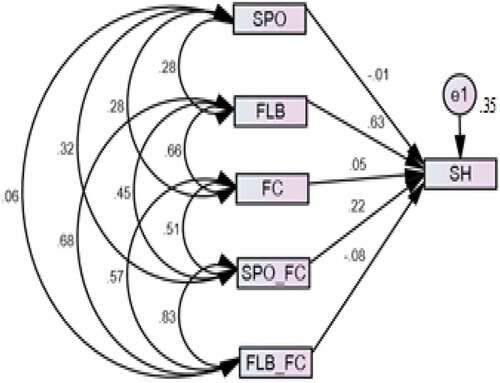

From model 3, we observed that all the predictors, except postal savings, had a positive impact on savings habit and explained 35% of the total variance. Financial consultants had a positive effect on the savings habit of people when the predictor small savings scheme was considered as an interaction variable (SPO_FC). Thus, this finding indicates that financial consultants exert a moderation effect on the savings habit of people. The structural model is presented in Figure .

We validated the hypothesized model by using the maximum likelihood estimation technique and by determining different model fit indices and other parameters. We obtained superior values in our model against the proposed threshold of 0.5–0.8 for model fit indices to be considered superior in social science research (Hair et al., Citation2010). All the values were >0.9, indicating that the proposed model well fits the data. The RMSEA was 0.052 (<0.08), and X2/df was 1.631 (<5.0), indicating the good fit of data for the model. In this model, R2 = 0.35 explained 35% of the variance. The model fit indices are listed in Table .

Table 6. Structural Model Fit Indices

Table presents the path details and effect size of latent constructs observed after due validation and observed to be significant and positive concerning the proposed model. A positive relationship was noted between exogenous variables, namely small savings schemes, financial literacy and behavior, financial consultants, and savings habit.

Table 7. Path details of the structural model

6. Discussion

The findings of the present study support the hypothesized model. We noted that small savings schemes, financial literacy and behavior, and financial consultants exert a significant positive effect on savings habits. The exogenous variables in the model explained 35% variance of the dependent (endogenous) variable because the R2 of the model was 0.35 (Cohen, Citation1988; Falk & Miller, Citation1992). Furthermore, the results revealed that financial consultants play a major role in influencing the savings habit, with a factor loading of 0.29 and an f-squared value of 0.1714, indicating a medium effect size. Small savings schemes (SPO) and financial literacy and behavior exhibited factor loadings of 0.26 and 0.25, indicating small effect sizes of 0.2124 and 0.0423, respectively. We determined that the interaction between financial consultants and small savings schemes and that between financial consultants and financial literacy and behavior exerted a medium effect on savings habits. Therefore, the significant effect of financial consultants, a moderating variable, cannot be refuted. Financial consultants moderate the synergistic impact on the savings habit. Therefore, organizations employing financial consultants to promote their financial products should view them as an asset instead of a liability.

7. Conclusion

This study investigated the impact of predictors on cultivating savings habits and the moderation role of financial consultants in developing countries such as India.

We used SEM to evaluate the impact of predictors on the savings habit. The data were statistically validated using measurement and structural models to evaluate the goodness of fit by using different fit indices. This study exhibited a significant association between hypothesized variables (i.e., exogenous and endogenous). We empirically examined the significant effect of predictors (small savings schemes and financial literacy and behavior) and the moderator (i.e., financial consultants) on the savings habit of people. Financial consultants as the predictor exhibited a better effect size (i.e., medium effect size; f-squared value = 0.1714) than did the other two predictors (i.e., small savings schemes and financial literacy and behavior). In addition, financial consultants exerted a synergistic effect on cultivating savings habits as the moderator and exhibited the highest effect size among all other predictors. The results revealed that financial consultants moderate the relationship between small savings schemes and financial literacy and behavior, thus cultivating the savings habit. Furthermore, the present study divulges the significant role of financial consultants in the financial inclusion process of beneficiaries in attaining the SDG goals for sustainable economic and social development.

Given that this is an emerging discipline, a thorough study can be conducted to examine the relative effect of other predictors, such as emotions and mood, on the savings habit. In addition, studies can identify the causes of the nonparticipation of people in savings and investment activities.

This study determined whether financial consultants predict and moderate the savings and investment habits of people. The findings of this study will be beneficial for policy implications and institutional services. The financial consultants should be formally integrated into the financial inclusion process and encouraged to play a significant role in the inclusive movement, especially in rural areas with low income and low literacy. Financial institutions and other intermediaries can formalize the services of the consultants for creating awareness and promoting their basic products and services to the unbanked population and can contribute significantly to financial inclusion. The financial consultants can also play a crucial role in bridging the trust gap among the savers and mobilizers to speed up the inclusive process. Both the government and financial institutions can develop products for the rural poor with help of the inputs gathered by these consultants, who understand the need of the poor through their interpersonal relationship. Though, this study contributes to the literature by enhancing the knowledge base and providing a roadmap to the academic community for future studies, it suffers from some limitations like small sample size and concentrated focus on the moderation effect of predictors (i.e., financial consultants). Future studies should consider different internal and external factors and widen the scope of the study to examine the savings behavior of people.

Appendix

Table A1. Total Variance Explained

Table A2. KMO and Bartlett’s Test

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adusei, M. (2013). Determinants of credit union savings in Ghana. Journal of International Development, 25(1), 22–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.2828

- Ajayi, K. F., 2016, Consumer perceptions and saving behaviour, Working Paper, Department of Economics and Center for Finance, Law and Policy, Boston University. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/bbe3/c7a90291bbad2c1be081ab939441d621b2ee.pdf .

- Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Peria, M. (2016). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 27(C), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2015.12.003

- Anand, G. (2019). Rural Investors: A study on perception towards postal investments. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 17(2), 1–6.

- Ando, A., & Modigliani, F. (1963). The “Life cycle” hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. The American Economic Review, 53(1), 55–84. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1817129

- Annual report NCAER. (2017-18). available at https://www.ncaer.org/uploads/annual-report/pdf/annual_report_20_Annual%20Report%202017-18.pdf

- Anthony Yaw, N., Yusif, H., Tweneboah, G., Agyei, K., & Tawiah Baidoo, S. (2021). The effect of financial inclusion on poverty reduction in sub-Sahara Africa: Does threshold matter? Cogent Social Sciences, 7(1), 1903138. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2021.1903138

- Ashraf, N., Karlan, D., & Yin, W. (2010). Female empowerment: Impact of a commitment savings product in the Philippines. World Development, 38(3), 333–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.05.010

- Atkinson, A., & Messy, F. (2013). promoting financial inclusion through financial education: OECD/INFE Evidence, policies and practice. In OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions (pp. 34). OECD Publishing. https://mpra.Ub.uni-muenchen.de/81141/1/MPRA_paper_81141.pdf

- Bachas, P., Gertler, P., Higgins, S., & Seira, E. (2016). Banking on trust: How debit cards help the poor to save more, Working Paper, UC Berkeley. https://economics.Yale.Edu/sites/default/files/bachasgertlerhigginsseira_v29.pdf

- Baidoo, S. T., & Akoto, L. (2019). Does trust in financial institutions drive formal saving? Empirical evidence from Ghana. International Social Science Journal, 69(231), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/issj.12200

- Baidoo, S. T., Boateng, E., & Amponsah, M. (2018). Understanding the determinants of saving in Ghana: Does financial literacy matter? Journal of International Development, 30(5), 886–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3377

- Baidoo, S. T., Boateng, E., & Amponsah, M. (2018). Understanding the determinants of saving inGhana: Does financial literacy matter? Journal of International Development, 30(5), 886–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3377

- Bakari, I. H., Donga, M., Adamu, I., Hedima, J. H., Kasima, W., Hajara, B., & Yusrah, I. (2019). An examination of the impact of financial inclusion on poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from sub Saharan Africa. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 9(1), 239–252. http://dx.doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.9.01.2019.p8532

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

- Beckmann, E., & Salvatore Mare, D., (2017), Formal and informal household savings: How does trust in financial institutions influence the choice of saving instruments? Working Paper, Foreign Research Division, Oesterreichische National bank, Vienna, Austria.

- Bogale, Y. L., Amsalu, B., & Melkamu, B. (2017). Determinants of saving behavior of households in Ethiopia: The case Benishangul Gumuz regional state. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 8(13), 27–37.

- Breza, E., & Chandrasekhar, A. G. (2019). Social networks, reputation, and commitment: Evidence from a savings monitors experiment. Econometrica, 87(1), 175–216. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA13683

- Brooke, E. W., Grant, S. M., & Rennekamp, K. M. (2017). How disclosure features of corporate social responsibility, reports interact with investor numeracy to influence investor judgments. Contemporary Accounting Research, 34(3), 1596–1621. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12302

- Bruhn, M., & Love, I. (2014). The real impact of improved access to finance: Evidence from Mexico. The Journal of Finance, 69(3), 1347–1376. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12091

- Camara, N., Pena, X., & Tuesta, D., (2014), Factors that matter for financial inclusion: Evidence from Peru, Working Paper No 14. sep, February. Economic Research Department, BBVA Bank.

- Chawla, D., & Joshi, H. (2021). Attitude as a mediator between antecedents of mobile banking adoption and user intention. Int. J. Business Excellence, 24(3), 321–339. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2021.115838

- Chopra, A., Avhad, V., & Jaju, S. (2021). Influencer marketing: An exploratory study to identify antecedents of consumer behavior of millennial. Business Perspectives and Research, 9(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533720923486

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Collins, N. L. (1996). Working models of attachment: Implications for explanation, emotion, and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 810–832. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.810

- Conrad, M., & Mutsonziwa, K. (2017). Financial literacy and savings decisions by adult financial consumers in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 41(1), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12318

- Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.2.448

- Duesenberry, J. S. (1949). Income, saving and the theory of consumer behaviour. Harvard University Press.

- Elizabeth, B., Dehaan, E., Wertz, J., & Christina, Z. (2019). Why do individual investors disregard accounting Information? The roles of information awareness and acquisition costs. Journal of Accounting Research, 57(1), 53–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12248

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modelling. University of Akron Press.

- Farzin, M., Ghaffari, R., & Fattahi, M. (2022). The influence of social network characteristics on the purchase intention. Business Perspectives and Research, 10(2), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/22785337211009661

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd Edition, Sage publications Ltd., London.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Friedman, M. (1957), The permanent income hypothesis. In A theory of the consumption function, Princeton University Press

- Fromlet, H. (2001). Behavioral finance-theory and practical application. Business Economics, 36(3), 63–69.

- Ganapathi, R. (2010). Investors’ attitude towards post office deposit schemes. BVIMR Management Edge, 3(2), 26–45.

- García-Santillán, A., Lizzeth, N.-I., Molchanova, V. S., & Castro, D. L. Q. (2021). Financial literacy level: An empirical study on savings, credit and budget management habits in high school students. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 10(4), 897–911. https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2021.4.897

- Gavini, A., & Athma, P. (1999). Small saving schemes of post office need to be known more. Southern Economist, 37(20), 13–14.

- Goldberg, J., (2014). Products and policies to promote saving in developing countries. Working Paper, IZA World of Labour. https://wol.iza.org/uploads/articles/74/pdfs/products-and-policies-to-promo.te-saving-in-developing-countries.pdf.

- Grohmann, A. (2018). Financial literacy and financial behavior: Evidence from the emerging Asian middle class. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 481, 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2018.01.007

- Grohmann, A., Klühs, T., & Menkhoff, L. (2018). Does financial literacy improve financial inclusion? Cross country evidence. World Development, 111(C), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.06.020

- Gulcin, G., & Regan, T. L. (2015). Self-Employment and the role of health insurance in the US. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(3), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.01.001

- Gwalani, H., & Parkhi, S. Gwalani Hema and Shilpa Parkhi. (2014). Financial inclusion – building a success model in the Indian context. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 133 15 May 2014 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.203.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.001

- Helmut, S. (2013). Why do people save in cash? Distrust, memories of banking crises, weak institutions and dollarization. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(11), 4087–4106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.07.015

- Ibrahim, A. U., & Olasunkanmi, A. F. (2019). Financial inclusion: Prospects and challenges in the Nigerian banking sector. European Journal of Business and Management, 11(29), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.7176/EJBM

- Jagongo, A., & Mutswenje, V. S. (2014). A survey of the factors influencing investment decisions: The case of individual investors at the NSE. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 4(4), 92–102. http://www.ijhssnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_4_Special_Issue_February_2014/11.pdf

- John Maynard, K. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. Macmillan Publishers.

- Joo, B. A., & Durri, K. (2018). Impact of psychological traits on rationality of individual investors. Theoretical Economics Letters, 8(11), 1973–1986. 811129 https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2018

- Karatepe, O. M., Yavas, U., & Babakus, E. (2005). Measuring service quality of banks: Scale development and validation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 12(5), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2005.01.001

- Khawar, S., & Sarwar, A. (2021). Financial literacy and financial behavior with the mediating effect of family financial socialization in the financial institutions of Lahore, Pakistan. Future Business Journal, 7(27), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-021-00064-x

- Kumar, P. K., & Laha, A. (2012). Determinants of financial inclusion: A study of some selected districts of West Bengal, India. Indian Journal of Finance, 5(8), 29–36.

- Lewellen, W. G., Lease, R. C., & Schlarbaum, G. G. (1977). Patterns of investment strategy and behavior among individual investors. The Journal of Business, 50(3), 296–333. https://doi.org/10.1086/295947

- Liu, J., Zhou, Y., Jiang, X., & Zhang, W. (2020). Consumers’ satisfaction factors mining and sentiment analysis of B2C online pharmacy reviews. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 20(194), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01214-x

- Lusardi, A. (2019). Financial literacy and the need for financial education: Evidence and implications. Swiss J Economics Statistics, 155(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.52.1.5

- Mahdzan, N. S., & Tabiani, S. (2013). The impact of financial literacy on individual saving: an exploratory study in the Malaysian context. Transformations in Business & Economics, 12(28), 41–55. 1

- Miriam, B., de Souza Leão, L., Legovini, A., Marchetti, R., & Zia, B., (2013), The impact of high school financial education: Experimental evidence from Brazil, Policy Research Working Paper, World Bank, https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-6723

- Mohammed Ahmar, U. (2020). Impact of financial literacy on individual saving: A study in the Omani context. Research in World Economy, 11 (5). 123–128. https://doi.org/10.5430/rwe.v11n5p123

- Mohanta, G., & Debasish, S. S. (2011). A study on investment preferences among urban investors in Orissa. Prerna Journal of Management Thought and Practice, 3(1), 1–9.

- Morgan Peter, J., & Quang Long, T. (2020). Financial literacy, financial inclusion, and savings behaviour in Laos. Journal of Asian Economics, 68(C), 101197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2020.101197

- Mumin, Y. A., Mohammed, A., & Kasim, H. (2016). Effects of selected socioeconomic factors and elections spending on aggregate savings (total deposits) in Ghana. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 8(2), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.5897/JEIF2015.0711

- Nanziri, E. L. (2016). Financial inclusion and welfare in South Africa: Is there a gender gap?. Journal of African Development, 18(2), 109–134. https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrideve.18.2.0109

- Netemeyer, R. G., Warmath, D., Fernandes, D., & Lynch, J. G. (2018). How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being, its potential antecedents, and its relation to overall well-being. Journal of Consumer Research, 45(1), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucx109

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Ogunleye, T. S., & Ogunleye Toyin Segun. (2017). Financial inclusion and the role of women in Nigeria. African Development Review, 29(2), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12254

- Prajapati, D., Paul, D., Malik, S., & Mishra, D. K. (2021, 15). Understanding the preference of individual retail investors on green bond in India: An empirical study. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 18(1), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.21511/imfi.18

- Roa, M. J., Garron, I., & Barboza, J. (2019). Financial decisions and financial capabilities in the Andean region. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(2), 296–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12187

- Sadananda, P. (2011). Household saving behaviour: Role of financial literacy and saving plans. The Journal of World Economic Review, 6(1), 93–104.

- Sakyi, D., Opoku Onyinah, P., Tawiah Baidoo, S., & Kojo Ayesu, E. (2021). Empirical determinants of saving habits among commercial drivers in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 22(1), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1695188

- Samuel Tawiah, B., Boateng, E., & Amponsah, M. (2018). Understanding the determinants of saving in Ghana: Does financial literacy matter? Journal of International Development, 30(5), 886–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3377

- Schreiber, J. B., Stage, F. K., King, J., Nora, A., & Barlow, E. A. (2006). Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

- Sefa Awaworyi, C., & Bhaskar Marisetty, V. (2020). Financial inclusion and poverty: A tale of forty-five thousand households. Applied Economics, 52(16), 1777–1788. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1678732

- Shawn, C., Sampson, T., & Zia, B. (2011). Prices or knowledge? What drives demand for financial services in emerging markets? The Journal of Finance, 66(6), 1933–1967. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01696.x

- Shiller, R. J. (2014). Speculative asset prices. The American Economic Review, 104(6), 1486–1517. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.6.1486

- Shiller Robert, J. (2000). Measuring bubble expectations and investor confidence. The Journal of Psychology and Financial Markets, 1(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327760JPFM0101_05

- Singh, A. (2002). Aid conditionality and development. Development and Change, 33(2), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00255

- Sofi, M. R., & Hakim, I. A. (2018). Customer relationship management as tool to enhance competitive effectiveness: Model revisited. FIIB Business Review, 7(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714518798410

- Soni, G., Kumar, S., Mahto, R. V., Mangla, S. K., Mittal, M. L., & Lim, W. M. (2022). A decision-making framework for Industry 4.0 technology implementation: The case of FinTech and sustainable supply chain finance for SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 180(C), 121686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121686

- Sorropago, C. (2014). Behavioral finance and agent-based model: The new evolving discipline of quantitative behavioral finance?. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 7(25), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.3610.6885

- Steinhart, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2019). Securing the future: Threat to self-image spurs financial saving intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(4), 741–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000159

- Sunden Annika, E., & Surrette, B. J. (1998). Gender differences in the allocation of assets in retirement savings plans. American Economic Review, 88(2), 207–211.

- Taufiq, D., Pratama, H., Masbar, R., & Effendi, R. (2019). Does financial inclusion alleviate household poverty? Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Economics and Sociology, 12(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-2/14

- Thornton, G. (2020). Financial Inclusion in Rural India. Grant Thornton India LLP, available at https://www.vakrangee.in/pdf/reports_hub/financial-inclusion-in-rural-india-28-jan.pdf

- Tullio, J., & Padula, M. (2013). Investment in financial literacy and savings decision. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(8), 2779–2792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.03.019

- Velsamy, R., & Amalorpavamary, P. (2015). Post office savings and its relevance in rural areas with reference to Thanjavur district. Ijmssr, 1(7), 141–146.

- Victor, V., Thoppan, J. J., Nathan, R. J., & Maria, F. F. (2018). Factors influencing consumer behavior and prospective purchase decisions in a dynamic pricing environment—An exploratory factor analysis approach. Social Sciences, 7(9), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7090153

- Viswanathan, P., Singh, A. B., & Gupta, G. (2020). The role of social influence and e-service quality in impacting loyalty for online life insurance: A SEM-based study. Int. J. Business Excellence, 20(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2020.106370

- Wang, F., Zhang, R., Ahmed, F., & Shah, S. M. M. (2021). Impact of investment behaviour on financial markets during COVID-19: A case of UK. Economic Research EkonomskaIstraživanja, 34(1), 24472468. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.1939089

- World Bank. (2018). World development indicators.

- World Bank, 2020, Rural population (% of Total population) - India https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=IN

- Yeal, S., & Jiang, Y. (2019). Securing the future: Threat to self-image spurs financial saving intentions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Attitudes and Social Cognition, 117(4), 741–757. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000159de