?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study explores the primary determinants of Indian OFDI in 26 developed and 81 developing countries by integrating a nuanced perspective of institutional distance with conventional location factors (2008–2018). Our findings indicate that asset augmentation and market-seeking motives are the primary OFDI drivers in developed and developing regions, respectively. Overall, the institutional environment demonstrates a positive association between Indian OFDI and the robust governance quality of the host country (excluding RS investments in developing region). However, only robust regulatory quality (RQ) & control of corruption (CC) are the primary IQ determinants significantly attracting OFDI in developed nations. Surprisingly, none of the WGI significantly drives OFDI in developing countries. However, the interaction effect reveals that only market-seeking investors from India are drawn to highly regulated (RQ), rule-based (RL) developing nations. The estimated FDI factors differ significantly depending on the destination, but RQ largely remains the crucial determinant across regions.

1. Introduction

Overseas or outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) has been a significant focus of multinational enterprises from emerging markets (EMNEs; UNCTAD, Citation2017). The recent surge in Indian and Chinese OFDI has intrigued researchers in international business (IB), which in the past was dominated by developed economies. For instance, there has been an extensive jump in OFDI by Indian MNEs from $678 million in 2001 to $12.26 billion in 2018, owing to continuing relaxations in capital account convertibility since 2004 and overseas investment (400% of the company’s net worth) under the automatic route since 2007 (Mohan, Citation2008). Indian OFDI’s CAGR over the previous two decades ranks second (18%) only to China (30%) (https://dea.gov.in/overseas-direct-investment).

The relationship between institutions and OFDI has recently received much attention from researchers and policymakers. Several researchers have examined the OFDI determinants linked to host and home countries’ institutional characteristics and factors such as high institutional quality (IQ),Footnote1 low labor costs, ease of doing business and other macroeconomic

stability-related aspects (Buckley et al., Citation2016; Jung, Citation2020; Ren et al., Citation2022; Zidi & Ali, Citation2016). Nevertheless, most existing research is focused on China’s OFDI, primarily driven by state-created advantages such as preferential access to capital, expedited approvals, technological support, tax advantages, and social networks in foreign markets (Yin et al., Citation2021; Zhu et al., Citation2022). Such preferential treatment enables Chinese OFDI to mitigate the disadvantages of “home country embeddedness” and institutional distances (ID), i.e., the difference between home-host institutional environment (IE) (Angulo-Ruiz et al., Citation2019). It further aids funding presumably least valuable technological and brand-seeking forays, notably in developed nations, which would otherwise jeopardize the investing firm’s long-term survival (Buckley, Citation2018). This confines the application of findings to other Asian developing countries where the state advantages are not ubiquitous and the private sector primarily supports OFDI. India aims to promote OFDI through relaxations in overseas investment norms, significantly strengthened by the Modi government since 2014 through policy interventions and institutional transformations.

North’s (Citation1990) Institutional framework highlighting the significance of institutions and its interaction within the economy provides a basis for investigating the institution-FDI relationship. According to Dunning’s (Citation1977) eclectic paradigm, economic variables such as GDP, population, labor and transportation costs, institutions, and governance quality significantly influence FDI. Literature suggests that institutional variables predict the destination choice of FDI more effectively than economic factors (Kang & Jiang, Citation2012; Altomonte, Citation2000). While conceptual studies exist exploring the effects of Indian OFDI on internationalization and global economic integration (Amendolagine et al., Citation2022; Chiappini & Viaud, Citation2021), empirical knowledge on how home-host ID affects OFDI motives is limited. India’s evolving formal institutional architecture, with the ambition to connect Indian firms with global markets under the Modi regime, presents a unique setting for reexamining Indian MNEs’ OFDI motivations and the influence of ID on OFDI.

Institutional voids distinctively characterize IE in a developing economy on various governance fronts (Wang & Lahiri, Citation2022). This compels EMNEs to indulge in “institutional arbitrage” through “institutional escapism” and “institutional exploitation” to manage the isomorphic burden of home-host ID (Buitrago et al., Citation2020; Luo & Tung, Citation2018; Nayyar et al., Citation2021). Studies report mixed evidence of the OFDI-ID relationship. Few studies demonstrate that EMNEs respond positively to host-country institutional weaknesses (Asaad & Marane, Citation2020; Park, Citation2018; Wei & Nguyen, Citation2017), whereas others report them preferring robust IE to avoid home institutional constraints (Rienda et al., Citation2019; Witt & Lewin, Citation2007). Such disparities demonstrate that IB needs to understand EMNEs’ OFDI across institutional settings completely, and further, the Chinese context could not be generalized due to the limitations mentioned earlier.

The study develops a multi-theoretic framework combining an institution-based view (IBV) with Dunning’s eclectic framework and contributes to theory and practice in multiple ways. First, the study examines primary OFDI determinants, both institutional (host-home ID) and economic (FDI motives), from the perspective of the developing Indian economy. The directionality rationale of ID is an assessment of how well the host country’s institutions work for foreign investors compared to the home country’s institutions (Zaheer et al., Citation2012). When a firm invests in institutionally better-performing (worse) country compared to home, its ID rises (decreases). Second, IE measured by a given set of institutional indicators varies across regions (Ahuja & Yayavaram, Citation2011); hence, categorizing nations into distinct groups (developing and developed) offers a more effective and integrated view of the institution-based overseas investment strategy. Third, assuming ID’s asymmetric impact on OFDI motives (Zaheer et al., Citation2012), the study explores how FDI motivations interact with ID to promote investment. Fourth, instead of an aggregate institutional index (Fon & Alon, Citation2022; Nayyar et al., Citation2021), the study employs six governance aspects of Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) (see methodology section) to capture their impacts separately. The authors believe that findings based on distinct institutional dimensions may enable policymakers to investigate more specific guidelines to attract or boost Indian OFDI. Simultaneously, it will guide Indian firms in aligning their internationalization motivations with the IE prevalent in the host country.

A contemporary understanding of the motivational and institutional forces influencing Indian OFDI in developing and developed regions will be gained by employing a Poisson-Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (PPML) estimation (Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006) with a panel data set. The estimation is based on RBI data on Indian OFDI in 107 host countries, 26 developed and 81 developing, from 2008 to 2018. Findings demonstrate that asset-augmenting efficiency-seeking (ES) motives in developed regions and market-seeking (MS) motives in developing regions are the primary Indian OFDI motivations. In a developing host country, robust IE has an insignificant positive effect on OFDI. However, the interaction effect indicates that the developing economy’s robust rule of law (RL) and regulatory quality (RQ) have a significant and positive influence on MS OFDI (institutional escapism). In contrast, weak PS and VA influence RS OFDI (institutional exploitation) in developing regions. On the contrary, robust RQ and corruption control (CC) are the primary institutional factors attracting OFDI ((institutional escapism) in the developed region.

The remaining paper is organized as follows. The second section reviews the theoretical framework of FDI, the third section explains the empirical methodology, the fourth section discusses empirical findings, and the last section concludes.

2. Theoretical framework

Several theoretical perspectives, such as neoclassical trade concepts (H-O Model), product life cycle model (Vernon, Citation1966), market imperfection theory (Hymer, Citation1976; Kindleberger, Citation1969), eclectic paradigm (Dunning, Citation1977), and knowledge-capital model (Markusen, Citation2002) have been widely used to address why firms invest overseas. Dunning’s eclectic paradigm or the ownership-locational-internalization (OLI) framework, incorporating Hymer’s (Citation1976) monopolistic advantages or asset-exploitation approach and Buckley and Casson’s (Citation1976) internalization theory, has been the most comprehensive theoretical model explaining MNEs OFDI motives. The framework assumes that an MNEs investment decision is characterized by its ability to capitalize on firm-specific ownership and locational advantages. The paradigm investigates MNEs investment location selection in terms of motivations and locational advantages such as large market size, low-cost production factors, natural resources, and strategic assets, which are explicitly referred to as market-seeking (MS), efficiency-seeking (ES), resource-seeking (RS), and strategic asset-seeking (SAS), respectively. In the mid-1980s, researchers classified FDI as horizontal and vertical. MS horizontal FDI seeks to maximize proximity to overseas clients and reduce trade costs (Brainard, Citation1993). Vertical FDI, on the other hand, allows for the fragmentation of manufacturing operations across nations to attain cost efficiency. The knowledge-capital model (Markusen, Citation2002) considers both of these motivations and assumes that knowledge-based assets provide firm-level scale economies, which reveals much about FDI from developed economies.

Nevertheless, the growth of EMNEs questions the classic FDI theory of firm-specific ownership to promote foreign investment. Studies advocate that firm-specific or country-specific disadvantages also encourage EMNEs overseas investments (Bhaumik et al., Citation2016; Liang et al., Citation2021). Through OFDI, EMNEs strive to integrate with global markets to achieve greater cost-efficiency, technological advancements and managerial skills (Buckley et al., Citation2022; Wood et al., Citation2021). Moon and Roehl (Citation2001) challenge the market imperfection theory further by emphasizing ownership imbalances over advantages, insisting that foreign investments seek to rectify imbalances by seeking ownership advantages. According to Ramamurti (Citation2012), EMNEs are yet in the initial phases of internationalization but have plans to catch up. More recently, Hamel and Prahalad’s (Citation1989) SAS intent approach has been used to investigate EMNE internationalization motivation to compete in global markets (Liang et al., Citation2021). SAS intent encourages EMNEs to overcome competitive disadvantages by leveraging their distinct ownership advantages (Mi et al., Citation2020; Nelaeva & Nilssen, Citation2022). Dunning and Lundan (Citation2008) assert that asset-exploiting motivations encourage EMNEs to invest in developing countries, while asset-augmenting motivations to enhance investing firms’ capabilities (Meyer, Citation2015) drive them to developed destinations. Dunning and Lundan (Citation2008) further propose that transaction costs and ownership benefits draw FDI to institutionally sound and better-governed nations. Besides these benefits, institutions strengthen structural and boundary framework for social interaction, shaping the associated people’s behavior and experience. As a result, IB thinkers argue that institutions should be considered explicit situational factors rather than background constraints (Lu et al., Citation2014; M. W. Peng et al., Citation2009).

North (Citation1990) defined institutions as “rules of a game” or “humanly constructed constraints that regulate political, economic, and social interaction” and classified them as informal or formal. In a community, the business environment is defined by formal institutions with stated norms, such as laws and regulations. In contrast, informal institutions are the constraints individuals in a community impose on themselves to manage their relationships with others, such as tradition, language, conventions, and ideals. Formal institutions facilitate effective economic operations and lower transaction costs (North, Citation1990). As the varying IE renders a variation in transaction costs across nations (Williamson, Citation1995), the institutional differences between the host-home country IE exhibit variation in institutional support for economic activities (Beugelsdijk et al., Citation2018). Hence, ID is deemed a crucial determinant of the transaction cost that affects OFDI decisions. MNEs escape constrained home institutions “institutional escapism” by investing in nations with stronger institutions. Moreover, they participate in institutional exploitation by investing in nations with similar institutional quality (Tang, Citation2021; Yoo & Reimann, Citation2017). Thus, the directionality of ID affects EMNEs’ FDI location and motivation choice in different ways (Hernández et al., Citation2018).

The integration of a 21st-century dynamic institution-based view (IBV) proposed by M. W. Peng et al. (Citation2009) with Dunning’s eclectic framework advances IB literature (R. Li & Cheong, Citation2019; McWilliam et al., Citation2020) and the present study approaches it from an emerging Indian economy perspective. The research assesses seven hypotheses on how institutional and traditional variables affect India’s OFDI in emerging and developed regions.

3. Empirical methodology

3.1. Data & variables

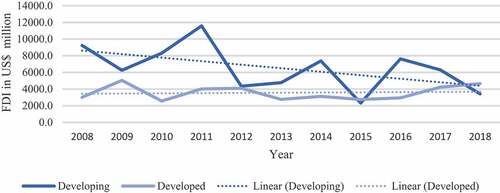

The present study employs PPML methodology to examine the impact of host-home ID on Indian OFDI. Similar to previous research, Indian overseas investment data is retrieved from the RBI’s OFDI database (Nayyar et al., Citation2021; Saikia et al., Citation2020). Monthly OFDI data is compiled annually based on investment destinations from 2008 to 2018. The sample comprises 107 host nations, 26 developed and 81 developing nations. Outflows to offshore financial centers such as Mauritius, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Panama, and the Cayman Islands are excluded from the study since the final destination of FDI funneled through this route is uncertain and may distort outcomes. The institutional and traditional factors are obtained from reliable databases (). Until 2012, developing nations were the top destinations for Indian offshore FDI; however, this tendency changed in favor of developed nations post-2012. ().

Table 1. Variables used in the study

3.2. Dependent variable

The annual Indian OFDI (in USD billion) from 2008 to 2018 is sourced from the RBI database. The destination countries are categorized as developing or developed based on the UN’sFootnote2 classification. The two regions with noticeably distinct IE and locational advantages may hinder or encourage MNEs’ locational preference (Aleksynska & Havrylchyk, Citation2013). Hence, to capture these differences distinctively, this categorization is deemed necessary.

3.3. Institutional quality variables

Study investigates the influence of home-host ID on Indian OFDI using the WGI. Each of the six major governance indicators, i.e., Corruption Control (CC), Government Effectiveness (GE), Political Stability (PS), Regulatory Quality (RQ), Rule of Law (RL), and Voice and Accountability (VA), indicate a specific facet of nation’s institutional excellence. The unbundling of institutional factors allows analysis of their diverse impacts on Indian OFDI across regions. The WGI ranges between −2.5 and +2.5. As multicollinearity between these indicators prevents simultaneous regression estimation, the study examines all six indicators in separate models. We retain the difference sign while estimating the host-home institutional distance (ID). The positive ID sign indicates a preference for robust or better IE, whereas the negative favor weaker or similar IE.

VA assesses citizens’ ability to choose their government and freedom pertaining to expression, and media among others (Kaufmann et al., Citation2009). VA enables the general public to gain information about government performance and voice their opinion. Monitoring and accountability assist the government, and its institutions (public sector) develop effective strategies. However, the incorporation or prohibition of public opinion in investment decisions can either promote or deter FDI (Mondolo, Citation2019; C. Peng et al., Citation2021).

PS measures political unrest. It estimates the risk of violent and illegal removal of the ruling government and signifies its capability to retain power. PS induces FDI by making business easier through stable political regimes. Studies widely suggest that a country’s political stability influences FDI (Akin, Citation2019; Shahzad & Al-Swidi, Citation2013). Despite popular belief, research also demonstrates that PS has a minimal impact on foreign investors because it is just a prerequisite for commencing investments in small developing countries (Kurecic & Kokotovic, Citation2017).

RQ reflects the government’s ability to design rules and regulations encouraging private-sector advancement (Kaufmann et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, the effectiveness with which regulations are created and enforced in society determines a country’s regulatory system (Mariotti et al., Citation2021). The host country’s eased regulatory burden on investments, operational processes, taxation, and market-unfriendly interventions, such as price control and inadequate banking, is thus regarded as critical determinants of FDI (Kiely, Citation2020; Sabir et al., Citation2019).

RL reflects agents’ perceptions about the enforcement of contracts, property rights, law, judiciary, violence, and crimes (Kaufmann et al., Citation2009). Government officials drive the most effective strategy to encourage the rule of law’ and institutions’ adherence to the rule of law standards in society (Teeramungcalanon et al., Citation2020). FDI is drawn to countries with a robust rule of law (Kasasbeh et al., Citation2018; Tiede, Citation2018). Weaker laws pertaining to property rights protection and legal structures discourage investors from taking risks. Findings suggest that property rights protection laws have significantly influenced FDI in developing nations and the former communist bloc (Q. Li & Resnick, Citation2003).

CC quantifies the degree to which public authority is exploited for personal advantage. Government corruption undermines foreign investment globally by allowing patronage to trump talent. More FDI generally flows into countries that crackdown on corruption, strengthen the rule of law and protect private property. Corruption creates market inefficiency and escalates production and management costs, jeopardizing FDI (Bhattacheryay, Citation2020; Lee et al., Citation2022).

GE evaluates the government’s service quality, capacity to design, implement, and adhere to policies and programs, and administrative independence from political restraints (Kaufmann et al., Citation2009). Ineffective policies hinder economic progress, making the country less attractive to foreign investors (C. Peng et al., Citation2021; Deng & Yang, Citation2015). A stable government guarantees policy continuity; hence, government effectiveness and FDI inflows are positively correlated.

As the Indian government continues to improve institutions, research assumes a lot remains to be accomplished. Hence, the paper hypothesizes that Indian OFDI, primarily fueled by private businesses, seeks institutionally distant host countries with robust IE.

H1: Indian OFDI is drawn to developing and developed countries with stronger IE.

H1a: Host countries with stronger VA in both regions attract Indian OFDI.

H1b: Host countries with stronger PS in both regions attract Indian OFDI.

H1c: Host countries with stronger RQ in both regions attract Indian OFDI.

H1d: Host countries with stronger RL in both regions attract Indian OFDI.

H1e: Host countries with stronger CC in both regions attract Indian OFDI.

H1f: Host countries with stronger GE in both regions attract Indian OFDI.

3.4. Traditional determinants

Based on the existing literature, our model includes key macroeconomic variables that are significant determinants of FDI: GDPsum, absolute GDP per capita difference, availability of natural resources, availability of strategic assets, trade openness, and profit tax rate.

Literature suggests that market size drives horizontal FDI (Zhu et al., Citation2022; Chiappini & Viaud, 2020). GDPsum is employed as a proxy for horizontal market-seeking (MS) OFDI. The dependent variable should rise if the home country considers the host a larger market. Indian firms’ MS motivations are seen in recent acquisitions across regions. For instance, Fab India Overseas acquired UK women’s fashion shop East Ltd., and Cox and Kings India acquired Prometheon Holdings. Max, Apollo, and Manipal hospitals have made investments in UAE, Qatar, and South Africa. Study hypotheses:

H2: Indian OFDI is positively associated with the host country’s market size in developed and developing economies.

Absolute GDPpcDiff exhibits skill and capital intensity disparities between home-host nations (Liang et al., Citation2021). Based on H-O factor endowment theory, the variable captures the pertinence of vertical or ES FDI by developed market MNEs (technologically advanced) in poorer host countries (with abundant labor & low production costs), also known as labor-seeking FDI (Hong et al., Citation2019). Technology-difference hypothesis contributes to the H-O’s explanatory power, particularly when EMNEs seek technology, managerial skills, and highly skilled labor in the developed economy (Trefler, Citation1995). Moon and Roehl (Citation2001) established the concept of imbalance against advantage to explain the unconventional FDI flow from poor source nations to wealthier host countries. Hence, EMNEs invest overseas to offset competitive shortcomings.

Asset-enhancement FDI, which seeks strategic assets to support a cheaper workforce, is similar to vertical FDI, which strives for a cheap workforce to support a country’s strategic assets, as long as new MNEs can effectively use the acquired assets (Ghahroudi et al., Citation2018). Since technology is generally associated with economic advancement, developed countries are appealing destinations for EMNEs seeking strategic assets to support cheaper labor (Athari & Adaoglu, Citation2019; Gao et al., Citation2019; James et al., Citation2020). As the study examines South-South and South-North OFDI, the variable’s coefficient is expected to be negative for developing nations indicating low cost (efficiency) seeking investments, and positive for developed nations indicating ES motive for asset augmentation, known as SAS intent (& Y. Kang et al., Citation2021). The asset-augmentation perspective,Footnote3 posits that EMNEs transcend global competition by acquiring knowledge-based strategic assets (Buckley et al., Citation2016; Yang et al., Citation2022). They use internationalization as a “springboard” for their future growth (Luo & Tung, Citation2007). This argument is supported by Tata and Suzlon’s foreign acquisitions. Tata Steel became the fifth-largest global steel manufacturer after acquiring Corus, while Suzlon became the fifth-largest wind turbine producer after acquiring RE Power and Hansen (Buckley et al., Citation2016). Thus, it is hypothesized that:

H3: Indian OFDI is positively associated with efficiency-seeking motivation in developed (asset-augmenting) and developing nations (low-cost).

The percentage of ores and metals exports to merchandise exports is used to estimate natural resource availability (Nresources). Rising resource costs and economic expansion have boosted competition for resources. Historically, MNEs leveraged overseas production facilities to gain host resources (& Y. Kang et al., Citation2021). India’s RS OFDI flows across regions, such as ONGC in Azerbaijan, Colombia, Brazil, Russia, Adani Group in Australia, Sun Petrochemicals and Reliance India in the USA (Varma et al., Citation2020). Flexible environmental policies in developing as opposed to developed economies foster RS investments (Contractor et al., Citation2020; Sutherland et al., Citation2020). Recent environmental protest over Adani’s Australian coal mine project is relevant to the argument. Owing to growing RS investments in both regions, the study hypothesizes that:

H4: Indian OFDI is positively associated with the availability of natural resources in developing and developed economies.

Patent and trademark filings by residents indicate a country’s technological prowess and are a proxy for host country’s strategic assets (Nayyar et al., Citation2021; Sutherland et al., Citation2020). SAS firms either augment home-country knowledge with host-country expertise or generate new knowledge. This classifies SAS FDI by asset type. Kuemmerle (Citation1997) postulates that home- base augmenting FDI substitutes deficient home-based knowledge with foreign knowledge. MNEs build overseas R&D to bolster domestic innovation and output. Home-based FDI integrates R&D with location-specific knowledge to create new businesses. From 2008 to 2018, developed nations attracted Indian OFDI in high-tech while developing in medium and low-tech (Joseph, Citation2019). High-innovation firms are proactive in leveraging external innovation, while low-innovation firms are reactive or passive (Y. Li & Rengifo, Citation2018). The study assumes that the high innovation capabilities of the Indian MNEs promote asset-exploiting SAS investments; hence we hypothesize that:

H5: Indian OFDI is positively associated with the availability of strategic assets (asset-exploiting) in developed and developing economies.

Trade Openness (TO), representing a liberal economic orientation, boosts FDI (Le & Kim, Citation2020). Trade share as a percentage of GDP measures trade openness. Free-trade environments in host nations enable MNEs to learn about local market conditions through FDI (Sajilan et al., Citation2019). Assuming that globalization and liberalized trade policies affect economic activity and attract FDI, the study hypothesizes that,

H6: Indian OFDI is positively associated with trade openness in developing and developed economies.

The effect of tax on FDI, proxied by total tax rate as a percentage of commercial profits, is widely used in empirical studies (Abdioğlu et al., Citation2016). Foreign investors seek to enhance their earnings after tax by transferring investments to countries that offer more tax benefitsFootnote4 (Sanjo, Citation2012). The study hypothesizes that,

H7: Indian OFDI is negatively associated with higher taxes in developing and developed nations.

4. Econometric estimation

Traditionally the log-linearized models were widely estimated by a linear estimator such as OLS. The natural logarithm is taken on both sides to arrive at the log-linearized model. However, OLS is subject to econometric issues. As OFDI assumes non-negative values, linear OLS cannot ensure non-negative predicted values. The problem of negativity can be resolved by applying natural log transformation to both sides. Nevertheless, this methodology works only with positive dependent variables, however in our dataset the OFDI flow to certain nations is zero for some years. The log-linearized model forces the truncation of zero-value observations because the log-linearization is not possible if yi = 0 since ln 0 = —∞. Furthermore, the predicted log-linear residual value will depend on the vector of covariates even though all observations of yi > 0. Consequently, OLS estimates are incongruent. Excluding zero-trade observations creates a truncated dependent variable, resulting in selection bias. Missing data can influence test outcomes and result in skewed conclusions. Silva and Tenreyro (Citation2006) recommended employing the Poisson-Pseudo Maximum Likelihood (PPML) methodology to estimate the nonlinear model. Researchers prefer Poisson regression with robust standard errors over log-transformed OLS linear regression. PPML ensures that fixed effects are equivalent to structural terms even with heteroscedasticity and high zero occurrences. PPML estimation with robust standard errors does not assume E(yi) = Var(yi) nor requires Var(yi) to be constant across all i. Thus, the PPML estimation with robust standard errors (Huber-White-Sandwich linearized variance estimator) is the best alternative to log-linear regressions (Motta, Citation2019).

Therefore, PPML the optimal estimator, is employed in our study.

Our baseline PPML model is as follows:

where OFDIijt is the measure of OFDI flow from home country i to host country j in year t

lnGDPsumtijt (natural log) representing Market, is the sum of GDP of country i and country j in year t

|GDPpcit-GDPpcjt | (natural log) representing Efficiency is the absolute difference between the GDPpc of country i and country j in year t

lnTax jt (natural log) represents tax rate in the host economy, measured by the total tax rate expressed as a percentage of commercial profits.

Metals represent natural resources (Nresources). The proportion of ores and metals exports as a percentage of merchandise exports is used as a proxy for Nresources.

lnpatents represent strategic assets. The total number of patent and trademark applications filed by a country’s citizens divided by the country’s population is used as a proxy for this statistic.

TO represents trade openness of the country measured by the proportion of exports + imports to GDP.

IQjt comprises institutional quality variables represented by World Bank’s six governance indicators, examined individually across six models

δt represent a set of year dummies capturing time FE

θt are host country dummies that capture host country FE.

εijt is the error term of the estimation

The RESET test is employed to ensure that PPML’s conditional mean is correctly specified (Ramsey, Citation1969). The Time FE model eliminates omitted variable bias by removing unobserved variables that vary but are consistent across entities. Country FE, on the contrary, estimates within-country variance and controls time-invariant country-specific factors. The results are computed controlling for time and country FE, which absorb unobserved heterogeneity and economic and contextual factors (Mariotti et al., Citation2021).

5. Empirical results

Our sample of 107 host nations is divided into 26 developed and 81 developing economies, following the UNCTAD classification (Appendix Table ).

Based on extant literature (Camarero et al., Citation2022; Papageorgiadis et al., Citation2020; Wang & Lahiri, Citation2022), time & country FE model is the most appropriate specification for the present estimation purpose. Testparm joint test (Prob > chi2 = 0.000) favors time-country FE.

The descriptive and correlation statistics for developing and developed regions are reported in

& , respectively. Due to the high multicollinearity between governance factors, they are all separately modeled. There is no multicollinearity issue because the variance inflation factor value for all explanatory variables across models is reported to be less than 10 (Hair et al., Citation1998). To avoid the simultaneity problem or reverse causality, time-varying variables are lagged by one year. Our PPML estimation for both developed and developing category models clears the RESET functional test (Prob > chi2 > 0.05). The findings of each region’s best estimators are discussed.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of developing nations

Table 3. Correlation of developing nation

5.1. Developed region

5.1.1. Results controlling for country & time FE

The findings () fully support H3, proving that asset-augmenting vertical FDI or efficiency seeking intent significantly motivate Indian overseas investments in developed nations. Rather than focusing on lower unit labor costs, this efficiency-seeking strategy aims to build new competitive advantages by merging the best global technology with low-cost Indian labor (Buckley et al., Citation2016).

Table 4. PPML estimation—developed nations

Findings reveal that asset exploiting SAS motivation (H5) is not a significant motivation for Indian investors in the developed region. Our findings support previous research indicating that the unconventional internationalization path taken by EMNEs lacking advanced technology and managerial capabilities is motivated by a desire to augment firm’s existing capabilities (Meyer, Citation2015; Stefano & Santangelo, Citation2017). Trade openness (H6) is found to promote Indian OFDI significantly. Studies suggest that the host country’s high trade openness attracts MNEs with efficiency-seeking (asset-augmenting) motivation to integrate into global value chain configurations (Behera & Mishra, Citation2022; Paul & Jadhav, Citation2019). The higher taxes have a negative but insignificant impact on OFDI. Hence, hypothesis H7 could not be proved. Tax haven countries (not part of the study) are the preferred investment destinations to overcome the tax burden; thus, the tax does not appear to be a significant factor influencing OFDI.

Investors are inclined towards robust IE (all β coefficients of WGI are positive); however, robust RQ (H1c) (β = 0.517, p = 5%) and CC (HI e) (β = 0.376, p = 5%) significantly drive OFDI (). Our findings corroborate previous research (Joffe, Citation2017; Prasad & Rajan, Citation2008), which contends that the robust IE in developed countries vis-à-vis home country is a significant motivator for investors. The leading reasons for overseas investments are inadequate infrastructure, poor institutional and financial setup and low-skilled labor. Moreover, as India’s stifling regulatory environment (RQ) creates uncertainty, drives up firms’ expenses, and impedes competitive advantage growth, it becomes even more critical for Indian MNEs to invest in nations with superior RQ (Nayyar & Prashantham, Citation2020). Similarly, to overcome the uncertainty in decision-making, unlike Chinese firms, Indian MNEs prefer to invest in the least corrupt nations (Qureshi et al., Citation2021).

Upon further investigating interaction (ID*RS) findings suggest that robust VA (β = 0.337, p = 1%), PS (β = 0.202, p = 5%) and CC (β = 0.197, p = 1%) qualities are preferred by RS investors (). The ID* SAS suggest that robust RQ (β = 0.043, p = 5%) and CC (β = 0.181, p = 5%) significantly encourage SAS investments. The ID*ES suggest that robust RQ (β = 0.047, p = 5%) and CC (β = 0.091, p = 5%) significantly drive ES OFDI. The ID*MS suggest that robust RQ (β = 0.218, p = 5%) and CC (β = 0.731, p = 5%) significantly drive MS OFDI. Though findings reveal asset augmenting ES motivation to be the primary OFDI motivation in developed nations, the complementary role of the effective institutional infrastructure in driving other investments cannot be ignored. The study assumes that more efficient bureaucratic structures and less corruption attract more private investment, as it provides a risk-free climate for foreign investors. Similar findings are reported by Sabir et al. (Citation2019).

Table 4a. PPML Estimation -Developed Nations: Interaction Effect

5.2. Developing region

5.2.1. Results controlling for country & time FE

The findings () suggest that Indian OFDI is significantly driven by the market(H2) motive in developing nations. Similar findings are reported by Varma et al. (Citation2020). Trade openness (H6) has the expected positive sign but did not reach the required significance level. Higher TO allows exporting enterprises to grasp the host market and regulatory provisions, overcome linguistic and cultural barriers, organize operations, and market their products internationally (Cieślik & Tran, Citation2019). Nevertheless, the literature also highlights that the FDI-trade association is complementary for ES projects and substitutive for MS ones (Swenson, Citation2004). Hence, the prominence of MS motivation may explain the variable’s insignificance in this scenario. Overall, investors are inclined towards robust IE (β values positive but insignificant), but none of the WGI is found to influence OFDI significantly. This could be justified on the ground that developing nations largely have an IE relatively similar to India’s. However, the interaction of WGI with investment motivations (next para) reveals that Indian investors prefer host countries with specific investment climate (factors) when driven by specific motivations. Surprisingly, higher taxes (H7) do not deter OFDI in the developing region but promote it. This could be justified by arguing that a relatively light tax burden cannot make up for an overall weak or unattractive FDI environment. When a higher tax burden is offset by strong infrastructural facilities and other country-specific characteristics such as large market size, countries with low taxation regimes have little influence on location choice (Johansson et al., Citation2008).

Table 5. PPML Estimation – Developing Nations

The interaction of ID*MS () suggests that robust RQ (β = 0.017, p = 1%) and RL (β = 0.014, p = 5%) moderates MS investments. Findings suggest that good governance and transparent, predictable judicial frameworks can boost FDI in developing economies. The World Bank’s (Citation2017) survey also reports a business-friendly legal and regulatory environment driving investments in developing nations. None of the WGI was found to influence the ES and SAS motivation of Indian OFDI. On the contrary, weaker (similar) VA (=−0.025, p = 10%) and PS (=−0.024, p = 10%) attract RS investments (ID*RS) due to reduced competition and a better likelihood of success. Our findings concur with past studies that robust democratic rights enhance the economy, but incorporating public opinion into investment choices hinders foreign investment, especially in mining or natural resource sectors (Jain & Thukral, Citation2022; Sabir et al., Citation2019; Teeramungcalanon et al., Citation2020).

Table 5a. PPML Estimation -Developing Nations: Interaction Effect

5.3. Robustness check

We assess robustness by omitting the nations with the highest OFDI in developed (USA) and developing (Singapore & UAE) regions. The findings remain qualitatively the same and are reported in and . We also performed negative binomial regression, an additional robustness test to identify primary motivational and institutional determinants. The results were found to be consistent. To maintain brevity, results are not reported but are available upon request.

Table 6. Robust PPML Estimation- Developed nation without USA

Table 6a. Robust PPML Estimation -Developed Nations without USA: Interaction Effect

Table 7. Robust PPML Estimation- Developing nations without Singapore & UAE

Table 7a. Robust PPML Estimation -Developing Nations without Singapore & UAE (Interaction Effect)

6. Conclusion

The study extends the understanding and knowledge of significant Indian OFDI determinants, both motivational and institutional, differentiated by regional destination. Findings overall demonstrate a positive association between Indian OFDI and the host country’s robust governance quality (excluding RS investments in developing regions). Robust RQ and CC in developed nations are the primary IQ determinants significantly attracting Indian OFDI. However, none of the WGI significantly influences OFDI in developing countries. The study proposes asset augmentation as the primary motivation for Indian OFDI in institutionally distant, robustly regulated (RQ), and least corrupt (CC) developed nations. Moreover, these qualities are also preferred by SAS (asset exploitation) and MS investments. Nevertheless, the RS investments prefer institutionally distant developed nations with more robust VA, PS and CC. Market seeking is the primary motivation for Indian OFDI in developing regions. Although investors overall prefer robust IE in developing countries, it is not a significant determinant. Nonetheless, the interaction effect indicates that strongly regulated (RQ), rule-based (RL) developing economies are significantly preferred by only MS investors from India. On the contrary, RS investments are largely driven to developing nations with weaker IE concerning PS and VA.

Findings reveal a significant difference between Indian and Chinese OFDI patterns. Unlike in India, the host country’s governance quality has a negative impact on Chinese OFDI (Fon & Alon, Citation2022). Because of their prior home experience in dealing with corruption, political instability, and accountability, Chinese MNEs do not hesitate to operate in economies with unstable IE (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2012). Additionally, the availability of concessional Chinese subsidies and loans also strengthens the risk ability of Chinese businesses to engage with weakly regulated economies (Lu et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, SAS MNEs from China heavily rely on innovation and knowledge-based ownership advantages (Mi et al., Citation2020). This explains why more Chinese MNEs invest in developing economies (asset exploitation & RS motive) vis-a-vis Indian OFDI (asset augmentation motive) in advanced countries (Zhu et al., Citation2022).

The significant OFDI activity in developed countries (USA, UK, Germany, and Australia) by Indian firms, mainly since 2014, is attributed to Prime Minister Modi’s foreign policy and Indian MNEs’ ambitions to acquire strategic assets and innovative technologies (asset-augmentation; Hall & Ganguly, Citation2022). The government’s “Make in India” strategy and institutional backing have boosted domestic manufacturing through knowledge-intensive international initiatives (Zhu et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, the low innovation capability of Indian MNEs raises concerns about ownership disadvantages (Buckley et al., Citation2016). EMNEs internationalise to establish competitive advantages by enhancing strategic assets and resources, which may increase global competitiveness but is insufficient to match international leaders with better strategic assets (Cui & Xu, Citation2019). Thus, the Indian government should invest heavily in R&D to support strategic corporate behaviour, such as collaborative research and technological improvement, because firms with excellent innovation abilities are better at obtaining and assimilating new information (Kang et al., Citation2021; Athari et al., Citation2020). Firms’ innovation skills encourage integrating existing and new knowledge derived from SAS behaviour, boosting innovation performance. Chinese MNEs with advanced technology and industrial prowess have had greater success in acquiring advanced strategic assets abroad (Deng et al., Citation2022).

The findings suggest that policymakers in developing countries should prioritise improving governance to attract FDI. Countries with strong institutions, good governance, and transparent and stable legal regimes are the preferred investment destinations even for emerging nations MNEs (except RS investments in developing region). In terms of managerial and practical ramifications, this study offers Indian investors an intriguing viewpoint on their strategic decisions in various international locations. Our findings help them understand the factors that influence investment across regions better.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leena Ajit Kaushal

Leena Ajit Kaushal is currently working as Assistant Professor in the area of Economics at Management Development Institute, Gurgaon, India. Her teaching interests include Macroeconomic Environment & Policy, Foreign Direct Investments and International Economics. Her research interest lies in the field of Sustainable Development, Foreign Direct Investment, Macroeconomic policy and Sharing Economy. She is Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (HEA), UK and possesses over 15 years of experience across a range of verticals which include University teaching in multinational and cross-cultural teaching environment, Investment banking industry and research fellowship with UGC grant commission. She is credited with research publications in various refereed national and international journals. She has published books on Managerial Economics by Thompson Publishing, “Global Entrepreneurship and New Venture Creation in the Sharing Economy” by IGI Global and FDI-The Indian Experience by BEP publishers. Her email address is [email protected]

Notes

1. High institutional quality characterizes a country’s institutional environment (IE), as determined by the World Bank using the approach of Kaufmann et al. (Citation1999) and based on six Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI).

3. Efficiency-seeking asset augmenting motive in the developed region will also be referred to as asset augmenting motive in the paper.

4. The OFDI routed through offshore financial centers like Panama, the Cayman Islands, and the Bahamas to other host countries, for tax evasion purposes is not part of our main sample study.

References

- Abdioğlu, N., Biniş, M., & Arslan, M. (2016). The effect of corporate tax rate on foreign direct investment: A panel study for OECD countries. Ege Academic Review, 16(4), 599–29.

- Ahuja, G., & Yayavaram, S. (2011). Perspective—Explaining influence rents: The case for an institutions-based view of strategy. Organization Science, 22(6), 1631–1652. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0623

- Akin, T. (2019). The effects of political stability on foreign direct investment in fragile five countries. Central European Journal of Economic Modelling and Econometrics, 4. https://doi.org/10.24425/cejeme.2019.131539

- Aleksynska, M., & Havrylchyk, O. (2013). FDI from the south: The role of institutional distance and natural resources. European Journal of Political Economy, 29, 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2012.09.001

- Altomonte, C. (2000). Economic determinants and institutional frameworks: FDI in economies in transition. Transnational Corporations, 9(2), 75–106.

- Amendolagine, V., Piscitello, L., & Rabellotti, R. (2022). The impact of OFDI in global cities on innovation by Indian multinationals. Applied Economics, 54(12), 1352–1365. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1976383

- Angulo-Ruiz, F., Pergelova, A., & Wei, W. X. (2018). How does home government influence the internationalization of emerging market firms? The mediating role of strategic intents to internationalize. International Journal of Emerging Markets.

- Angulo-Ruiz, F., Pergelova, A., & Wei, W. X. (2019). How does home government influence the internationalization of emerging market firms? The mediating role of strategic intents to internationalize. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 14(1), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJoEM-08-2017-0274

- Asaad, Z. A., & Marane, B. M. (2020). The influence of human development, institutional quality and ISIS emergence on foreign direct investment in Iraq. Technium Society Science Journal, 10, 318. https://doi.org/10.47577/tssj.v10i1.1402

- Athari, S. A., & Adaoglu, C. (2019). Nexus between institutional quality and capital inflows at different stages of economic development. International Review of Finance, 19(2), 435–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/irfi.12169

- Athari, S. A., Shaeri, K., Kirikkaleli, D., Ertugrul, H. M., & Ozun, A. (2020). Global competitiveness and capital flows: Does stage of economic development and risk rating matter? Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, 27(4), 426–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/16081625.2018.1481754

- Behera, P., & Mishra, B. R. (2022). Determinants of bilateral FDI positions: Empirical insights from ECs using model averaging techniques. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 58(3), 710–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2020.1837107

- Beugelsdijk, S., Kostova, T., Kunst, V. E., Spadafora, E., & Van Essen, M. (2018). Cultural distance and firm internationalization: A meta-analytical review and theoretical implications. Journal of Management, 44(1), 89–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317729027

- Bhattacheryay, S. (2020). Multinational enterprises motivational factors in capitalizing emerging market opportunities and preparedness of India. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 12(4), 609–640. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-01-2019-0010

- Bhaumik, S. K., Driffield, N., & Zhou, Y. (2016). Country specific advantage, firm specific advantage and multinationality–Sources of competitive advantage in emerging markets: Evidence from the electronics industry in China. International Business Review, 25(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.12.006

- Brainard, S. L. (1993). A simple theory of multinational corporations and trade with a trade-off between proximity and concentration. https://doi.org/10.3386/w4269

- Buckley, P. J. (2018). Internalization theory and outward direct investment by emerging market multinationals. Management International Review, 58(2), 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-017-0320-4

- Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. (1976). The future of multinational enterprise. Macmillan.

- Buckley, P. J., Driffield, N., & Kim, J. Y. (2022). The role of outward FDI in creating Korean global factories. Management International Review, 62(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-022-00462-5

- Buckley, P. J., Munjal, S., Enderwick, P., & Forsans, N. (2016). Cross-border acquisitions by Indian multinationals: Asset exploitation or asset augmentation? International Business Review, 25(4), 986–996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.10.006

- Buitrago, R., E, R., & Barbosa Camargo, M. I. (2020). Home country institutions and outward FDI: An exploratory analysis in emerging economies. Sustainability, 12(23), 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122310010

- Camarero, M., Montolio, L., & Tamarit, C. (2022). Explaining German outward FDI in the EU: A reassessment using Bayesian model averaging and GLM estimators. Empirical Economics, 62(2), 487–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-021-02040-4

- Chiappini, R., & Viaud, F. (2021). Macroeconomic, institutional, and sectoral determinants of outward foreign direct investment: Evidence from Japan. Pacific Economic Review, 26(3), 404–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0106.12347

- Cieślik, A., & Tran, G. H. (2019). Determinants of outward FDI from emerging economies. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy, 14(2), 209–231.

- Contractor, F. J., Dangol, R., Nuruzzaman, N., & Raghunath, S. (2020). How do country regulations and business environment impact foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows? International Business Review, 29(2), 101640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101640

- Cui, L., & Xu, Y. (2019). Outward FDI and profitability of emerging economy firms: Diversifying from home resource dependence in early stage internationalization. Journal of World Business, 54(4), 372–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.04.002

- Deng, Z., Li, T., & Liesch, P. W. (2022). Performance shortfalls and outward foreign direct investment by MNE subsidiaries: Evidence from China. International Business Review, 31(3), 101952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101952

- Deng, P., & Yang, M. (2015). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions by emerging market firms: A comparative investigation. International Business Review, 24(1), 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2014.07.005

- Dunning, J. H. (1977). Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach. In B. Ohlin, P. O. Hesselborn, & P. M. Wijkman, (Eds.), The international allocation of economic activity (pp. 395–418). UK, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dunning, J. H., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Institutions and the OLI paradigm of the multinational enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(4), 573–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-007-9074-z

- Fon, R., & Alon, I. (2022). Governance, foreign aid, and Chinese foreign direct investment. Thunderbird International Business Review, 64(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22257

- Gao, Q., Li, Z., & Huang, X. (2019). How EMNEs choose location for strategic asset seeking in internationalization? Based on strategy tripod framework. Chinese Management Studies, 13(3), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-06-2018-0573

- Ghahroudi, M. R., Hoshino, Y., & Turnbull, S. J. (2018). Foreign direct investment: Ownership advantages, firm specific factors, survival and performance. World Scientific.

- Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Factor analysis. Multivariate data analysis. NJ Prentice-Hall, 3, 98–99.

- Hall, I., & Ganguly, Š. (2022). Introduction: Narendra Modi and India’s foreign policy. International Politics, 59(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00363-8

- Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (1989). Strategic intent. Harvard Business Review, 67(3), 63–76.

- Hamel, G., & Prahalad, C. K. (2010). Strategic intent. Harvard Business Press.

- Hernández, V., Nieto, M. J., & Boellis, A. (2018). The asymmetric effect of institutional distance on international location: Family versus nonfamily firms. Global Strategy Journal, 8(1), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1203

- Hong, E., Lee, I. H. I., & Makino, S. (2019). Outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) motivation and domestic employment by multinational enterprises (MNEs). Journal of International Management, 25(2), 100657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2018.11.003

- Hymer, S. (1976). A study of direct foreign investment. MIT Press.

- Jain, A., & Thukral, S. (2022). What causes outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) from India into least developed countries (LDCs)? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2022.2097619

- James, B. E., Sawant, R. J., & Bendickson, J. S. (2020). Emerging market multinationals’ firm-specific advantages, institutional distance, and foreign acquisition location choice. International Business Review, 29(5), 101702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101702

- Joffe, M. (2017). Why does capital flow from poor to rich countries? – The real puzzle. Real-World Economics Review, 81, 42–62.

- Johansson, A., Heady, C., Arnold, J., Brys, B., & Vartia, V. (2008). “Tax and Economic Growth,” OECD Economics Department Working Paper No. 620, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/58/3/41000592.pdf

- Joseph, R. K. (2019). Outward FDI from India: Review of policy and emerging trends. Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, Report no, 214,: https://isid.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/WP214.pdf

- Jung, J. (2020). Institutional quality, FDI, and productivity: A theoretical analysis. Sustainability, 12(17), 7057. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177057

- Kang, Y., & Jiang, F. (2012). FDI location choice of Chinese multinationals in East and Southeast Asia: Traditional economic factors and institutional perspective. Journal of World Business, 47(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.019

- Kang, Y., Scott-Kennel, J., Battisti, M., & Deakins, D. (2021). Linking inward/outward FDI and exploitation/exploration strategies: Development of a framework for SMEs. International Business Review, 30(3), 101790. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101790

- Kasasbeh, H. A., Mdanat, M. F., & Khasawneh, R. (2018). Corruption and FDI inflows: Evidence from a small developing economy. Asian Economic and Financial Review, 8(8), 1075–1085. https://doi.org/10.18488/journal.aefr.2018.88.1075.1085

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2009). Governance matters VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996-2008. World bank policy research working paper, (4978), World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-4978

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Zoido-Lobaton, P. (1999). ”Governance matters,” Policy Research Working Paper Series 2196, The World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/4170/WPS4978.pdf

- Kiely, R. (2020). Neoliberalism revised? A critical account of world bank conceptions of good governance and market friendly intervention. In The Political Economy Of Social Inequalities (pp. 209–228). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315231051

- Kindleberger, C. P. (1969). American business abroad: Six lectures on direct investment. Yale University Press.

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2012). What determines Chinese outward FDI? Journal of World Business, 47(1), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.017

- Kuemmerle, W. (1997). Building effective R&D capabilities abroad. Harvard Business Review, 75(2), 61–72.

- Kurecic, P., & Kokotovic, F. (2017). The relevance of political stability on FDI: A VAR analysis and ARDL models for selected small, developed, and instability threatened economies. Economies, 5(3), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies5030022

- Lee, H., Park, J., & Chung, C. C. (2022). CEO compensation, governance structure, and foreign direct investment in conflict-prone countries. International Business Review, 31(6), 102031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2022.102031

- Le, A. H., & Kim, T. (2020). The effects of economic freedom on firm investment in Vietnam. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(3), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no3.9

- Liang, Y., Giroud, A., & Rygh, A. (2021). Emerging multinationals’ strategic asset-seeking M&As: A systematic review. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 16(7), 1348–1372. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2019-1059

- Liang, Y., Giroud, A., & Rygh, A. (2021). Emerging multinationals' strategic asset-seeking M&As: A systematic review. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 16(7), 1348–1372. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2019-1059

- Li, R., & Cheong, K. C. (2019). Going out”, going global, and the belt and road. In China’s state enterprises (pp. 151–194). Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Li, Y., & Rengifo, E. W. (2018). The impact of institutions and exchange rate volatility on China’s outward FDI. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(12), 2778–2798. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1412302

- Li, Q., & Resnick, A. (2003). Reversal of fortunes: Democratic institutions and foreign direct investment inflows to developing countries. International Organization, 57(1), 175–211. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818303571077

- Lu, J., Liu, X., Wright, M., & Filatotchev, I. (2014). International experience and FDI location choices of Chinese firms: The moderating effects of home country government support and host country institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(4), 428–449. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.68

- Luo, Y., & Tung, R. L. (2007). International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 481–498. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400275

- Luo, Y., & Tung, R. L. (2018). A general theory of springboard MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(2), 129–152. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0114-8

- Mariotti, S., Marzano, R., & Piscitello, L. (2021). The role of family firms’ generational heterogeneity in the entry mode choice in foreign markets. Journal of Business Research, 132, 800–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.064

- Markusen, J. R. (2002). Multinational firms and the theory of international trade. MIT Press.

- McWilliam, S. E., Kim, J. K., Mudambi, R., & Nielsen, B. B. (2020). Global value chain governance: Intersections with international business. Journal of World Business, 55(4), 101067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2019.101067

- Meyer, K. (2015). What is “strategic asset seeking FDI”? Multinational Business Review, 23(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBR-02-2015-0007

- Mi, L., Yue, X. G., Shao, X. F., Kang, Y., & Liu, Y. (2020). Strategic asset seeking and innovation performance: The role of innovation capabilities and host country institutions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13030042

- Mohan, R., 2008. ”Capital flows to India,” BIS Papers chapters, in: Bank for International Settlements (Ed.), Bank for International Settlements, Vol. 44, pp. 235–263, Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap44.pdf

- Mondolo, J. (2019). How do informal institutions influence inward FDI? A systematic review. Economia politica, 36(1), 167–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-018-0119-1

- Moon, H. C., & Roehl, T. W. (2001). Unconventional foreign direct investment and the imbalance theory. International Business Review, 10(2), 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-59310000046-9

- Motta, V. (2019). Estimating Poisson pseudo-maximum-likelihood rather than log-linear model of a log-transformed dependent variable. RAUSP Management Journal, 54(4), 508–518. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-05-2019-0110

- Nayyar, R., Mukherjee, J., & Varma, S. (2021). Institutional distance as a determinant of outward FDI from India. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2019-1031

- Nayyar, R., & Prashantham, S. (2020). Subnational institutions and EMNE acquisitions in advanced economies: Institutional escapism or fostering? Critical Perspectives on International Business. https://doi.org/10.1108/cpoib-01-2019-0007

- Nelaeva, A., & Nilssen, F. (2022). Contrasting knowledge development for internationalization among emerging and advanced economy firms: A review and future research. Journal of Business Research, 139, 232–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.053

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge university press.

- Papageorgiadis, N., McDonald, F., Wang, C., & Konara, P. (2020). The characteristics of intellectual property rights regimes: How formal and informal institutions affect outward FDI location. International Business Review, 29(1), 101620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101620

- Park, S. B. (2018). Multinationals and sustainable development: Does internationalization develop corporate sustainability of emerging market multinationals? Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1514–1524. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2209

- Paul, J., & Jadhav, P. (2019). Institutional determinants of foreign direct investment inflows: Evidence from emerging markets. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-11-2018-0590

- Peng, C., Jiang, H., Song, H., & Zhang, T. (2021). Does institutional distance affect the risk preference of enterprises’ OFDI: Evidence from China. Managerial and Decision Economics. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3448

- Peng, M. W., Sun, S. L., Pinkham, B., & Chen, H. (2009). The institution-based view as a third leg for a strategy tripod. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(3), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2009.43479264

- Prasad, E. S., & Rajan, R. G. (2008). A pragmatic approach to capital account liberalization. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 149–172. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.22.3.149

- Qureshi, F., Qureshi, S., Vo, X. V., & Junejo, I. (2021). Revisiting the nexus among foreign direct investment, corruption and growth in developing and developed markets. Borsa Istanbul Review, 21(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2020.08.001

- Ramamurti, R. (2012). Competing with emerging market multinationals. Business Horizons, 55(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2012.01.001

- Ramsey, J. B. (1969). Tests for specification errors in classical linear least‐squares regression analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 31(2), 350–371.

- Ren, S., Hao, Y., & Wu, H. (2022). The role of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) on green total factor energy efficiency: Does institutional quality matters? Evidence from China. Resources Policy, 76, 102587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102587

- Rienda, L., Claver, E., Quer, D., & Andreu, R. (2019). Family businesses from emerging markets and choice of entry mode abroad: Insights from Indian firms. Asian Business & Management, 18(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-018-00053-z

- Sabir, S., Rafique, A., & Abbas, K. (2019). Institutions and FDI: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Financial Innovation, 5(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-019-0123-7

- Saikia, M., Das, K. C., & Borbora, S. (2020). What drives the boom in outward FDI from India? International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(5), 899–922. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-12-2017-0538

- Sajilan, S., Islam, M. U., Ali, M., & Anwar, U. (2019). The determinants of FDI in OIC countries. International Journal of Financial Research, 10(5), 466–473. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijfr.v10n5p466

- Sanjo, Y. (2012). Country risk, country size, and tax competition for foreign direct investment. International Review of Economics & Finance, 21(1), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2011.08.002

- Shahzad, A., & Al-Swidi, A. K. (2013). Effect of macroeconomic variables on the FDI inflows: The moderating role of political stability: An evidence from Pakistan. Asian Social Science, 9(9), 270. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n9p270

- Silva, J. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.641

- Stefano, E., & Santangelo, G. D. (2017). The evolution of strategic asset-seeking acquisitions by emerging market multinationals. International Business Review, 26(5), 855–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.02.004

- Sutherland, D., Anderson, J., Bailey, N., & Alon, I. (2020). Policy, institutional fragility, and Chinese outward foreign direct investment: An empirical examination of the Belt and Road Initiative. Journal of International Business Policy, 3(3), 249–272. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00056-8

- Swenson, D. L. (2004). Foreign investment and the mediation of trade flows. Review of International Economics, 12(4), 609–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2004.00470.x

- Tang, R. W. (2021). Pro-market institutions and outward FDI of emerging market firms: An institutional arbitrage logic. International Business Review, 30(3), 101814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101814

- Teeramungcalanon, M., Chiu, E. M., & Kim, Y. (2020). Importance of Political Elements to Attract FDI for ASEAN and Korean Economy. Journal of Korea Trade, 24(8), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.35611/jkt.2020.24.8.63

- Tiede, L. B. (2018). The rule of law, institutions, and economic development. In C. May, & A. Winchester (Eds.), Handbook on the rule of law. (pp. 405–418). London, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Trefler, D. (1995). The case of the missing trade and other mysteries. The American Economic Review, 1029–1046. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/aeaaecrev/v_3a85_3ay_3a1995_3ai_3a5_3ap_3a1029-46.htm

- UNCTAD., 2017. World investment report 2017, available at: https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2017

- Varma, S., Bhatnagar, A., Santra, S., & Soni, A. (2020). Drivers of Indian FDI to Africa–an initial exploratory analysis. Transnational Corporations Review, 12(3), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2020.1803186

- Vernon, R. (1966). International trade and international investment in the product cycle. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.2307/1880689

- Wang, D., & Lahiri, S. (2022). Bilateral foreign direct investments: Differential effects of tariffs in source and destination countries. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2022.2080246

- Wei, Z., & Nguyen, Q. T. (2017). Subsidiary strategy of emerging market multinationals: A home country institutional perspective. International Business Review, 26(5), 1009–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.03.007

- Williamson, O. E. (Ed.). (1995). Organization theory: From Chester Barnard to the present and beyond. Oxford University Press.

- Witt, M. A., & Lewin, A. Y. (2007). Outward foreign direct investment as escape response to home country institutional constraints. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 579–594. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400285

- Wood, G., Pereira, V., Temouri, Y., & Wilkinson, A. (2021). Exploring and investigating sustainable international business practices by MNEs in emerging markets. International Business Review, 30(5), 101899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101899

- World Bank., 2017. Global investment competitiveness report 2017/2018: Foreign investor perspectives and policy implications, available at: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-1-4648-1175-3

- Yang, Y., Xu, J., Allen, J. P., & Yang, X. (2022). Strategic asset-seeking foreign direct investments by emerging market firms: The role of institutional distance. International Journal of Emerging Markets, (ahead–of–print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-04-2020-0346

- Yin, T., De Propris, L., & Jabbour, L. (2021). Assessing the effects of policies on China’s outward foreign direct investment. International Business Review, 30(5), 101818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101818

- Yoo, D., & Reimann, F. (2017). Internationalization of developing country firms into developed countries: The role of host country knowledge-based assets and IPR protection in FDI location choice. Journal of International Management, 23(3), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2017.04.001

- Zaheer, S., Schomaker, M. S., & Nachum, L. (2012). Distance without direction: Restoring credibility to a much-loved construct. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.43

- Zhu, Y., Sardana, D., & Tang, R. (2022). Heterogeneity in OFDI by EMNEs: Drivers and trends of Chinese and Indian firms. International Business Review, 102013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2022.102013

- Zidi, A., & Ali, T. (2016). Foreign direct investment (FDI) and governance: The case of MENA. Journal of Research in Business, Economics and Management, 5(3), 598–608. http://www.scitecresearch.com/journals/index.php/jrbem/article/view/629

Appendix

Table A1. List of Developed & Developing Nations