?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examines spillover effects of foreign direct investment (FDI) through horizontal, backward, and forward linkages, and how these spillovers are driven by the exporting ability for Vietnamese manufacturing enterprises. Those participating in export activity can increase the spillover absorption from FDI through the horizontal and backward linkages although local firms are less likely to take advantage of productivity spillovers during this period. In addition, these exporting firms confront the productivity protection of the FDI firms in the same industries. In contrast, the higher their exportability is, the better their learning from the foreign firms in the same downstream sectors becomes. The findings of this paper provide valuable evidence and implications for policymakers in managing and enhancing export ability for firms in the emerging market.

1. Introduction

Productivity growth always plays an indispensable role in the prosperity of the country in general and of the local firms in particular (Dieppe, Citation2021). Contributing to the important part of capital and labor in increasing productivity has been proven by previous research. However, the factor greatly concerned and studied recently is that how total factor productivity (TFP) is used to measure the productivity of both labor and capital. In previous studies regarding the role of FDI in the country’s economy, the direction to indirect spillover effects on the productivity of local firms has always been the subject interested by a huge number of researchers as well as policymakers around the world (Görg & Greenaway, Citation2004; Kuswardana et al., Citation2021). Foreign-invested enterprises are likely able to affect productivity to local firms through different channels (Huynh et al., Citation2019; Javorcik, Citation2004).

The fact that horizontal spillover effects are associated with the existence of FDI enterprises in the same industry has put the pressure on local firms through the observation process, learning, and competitiveness in business. The movement of skillful and competent labors from FDI enterprises to local firms is one of the significant factors to better the technology absorption process in host countries (Bruno & Cipollina, Citation2018; Glass & Saggi, Citation2002; Keller, Citation1996). Furthermore, FDI companies in the same industry can increase intense competition and domestic enterprises become more forceful in the quest for new technology (Blomström & Kokko, Citation1996; Bruno & Cipollina, Citation2018). Numerous recent studies in developing countries demonstrate that horizontal linkages cause negative impacts leading to reducing productivity of enterprises in host countries (Ni et al., Citation2017); therefore, FDI enterprises can easily increase their market share from local firms upon creating crowding-out effects with the advantages of technology and market data (Aitken et al., Citation1997; Kim & Choi, Citation2019; Kokko, Citation1996).

Vertical linkages occur between FDI enterprises and local firms operating in different industries; on the other hand, those have commercial activities with each other, including backward linkages from FDI enterprises to local suppliers (backward) and forward linkages from FDI suppliers to local firms (forward). Backward linkages create technological spillovers through different mechanisms. Firstly, demanding requirements for product quality and on-time delivery which are extremely considered by FDI enterprises bring positive incentives to local firms to enhance the production process or technology. Secondly, direct technology transfer to local suppliers by training or technological support increases product quality (Javorcik, Citation2004). Forward linkages from supplying intermediary machinery and production processes help to reduce cost and increase productivity for local firms due to global research activities (Huynh et al., Citation2019; Meyer & Sinani, Citation2009).

Productivity spillovers are being studied extensively for these three linkages despite the variable results, depending on the absorptive capacity of the host country (Iršová & Havránek, Citation2013; Meyer & Sinani, Citation2009). What matters is that the researches on spillover effects through exports have been limited (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2014; Kim & Xin, Citation2021). Although there are a number of studies researching about spillover effects of FDI export to local firms, their results are different. Kokko (Citation1996) believes that the difference is due to the absorptive capacity of domestic enterprises. In terms of one Vietnamese case, Huynh et al. (Citation2019) showed that spillover effects depend upon the derivation of FDI companies; in contrast, Anwar and Nguyen (Citation2011) proved that spillover effects derive from exporting activities of FDI firms. Due to the fact that emerging countries like Vietnam with FDI enterprises accounting for 70% in the export proportion results in the authors’ concentration on examining whether firms participating in export increase total factor productivity in this paper. Vietnam, an emerging country with diverse changes after joining the World Trade Organization in 2007, has witnessed the attraction of massive FDI sources. As a result, in the period after the global crisis in 2008 with the policy of promoting export and increasing FDI attraction, there were many progresses in the period to help overcome the crisis and to have outstanding growth points. Currently, FDI capital, in the post-Covid period and the US-China Trade War, is looking for other countries in Southeast Asia, in which, Vietnam, with the 24th position after Indonesia at the 19th position, is a bright spot to attract FDI globally (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Citation2021). The spillover effects of FDI on TFP of Vietnam manufacturing enterprises are clarified through export activities; at the same time, identifying the roles of horizontal, backward, and forward linkages with this effect will definitely be a valued experience for other emerging nations.

Our study contributes to the literature in the following respects. First, this is a pioneering study that contributes to the theory of productivity spillovers from the FDI sector to the domestic sector through exports in an emerging market, since previous studies have all worked on with developed countries. Second, the aggregate productivity of domestic firms engaged in exporting is increased through horizontal linkage and backward linkage, whereas the forward linkage has a negative effect. In terms of enterprises with better export ability, the backward linkage is an important productivity spillover channel. Third, the authors believe that our findings offer direct insights and implications for the policymaker in emerging markets, with respect to policies that target the firm’s export ability.

Following this introduction, the remainder of this study is structured as follows: Section 2 presents Literature review. Section 3 discusses the Research methodology and data. Empirical findings and discussions are presented in Section 4, followed by the conclusions and policy implications in Section 5.

2. Literature review

2.1. Spillover effects of FDI to local firms

The topic that spillover effects from FDI enterprises to local firms are indirect effects has been of interest by international researchers and policymakers. FDI firms are equipped with massive mechanisms to improve technological spillovers to local firms (Blomström & Kokko, Citation1996; Girma, Citation2005). Horizontal spillovers are related to understandings obtained in the same industry because of the presence of FDI enterprises. On the other hand that the vertical spillovers occur between FDI and domestic firms in different industries may take place through backward linkages (from buyers to suppliers) and forward linkages (from suppliers to buyers). J. Y. Wang (Citation1990) continues to develop Findlay’s model and acknowledges that global labor mobility helps to better technological spillovers and the host country absorbs technology more quickly if connectivity is expanded. Nonetheless, the results of spillovers are considerably different (Huynh et al., Citation2019; Meyer & Sinani, Citation2009; Villar et al., Citation2020).

Both Driffield (Citation2001) analyzes with industry data in the UK in 1986–1992 and Imbriani et al. (Citation2014) based on the data of manufacturing enterprises in Italia in 2002–2007 conform that the study does not have spillover effects from FDI to local firms. More empirical studies show that the impact of FDI on domestic enterprises is positively increasing productivity. Haskel et al. (Citation2007), Görg and Strobl (Citation2003), and Keller and Yeaple (Citation2003), in accordance with the data from the industry data in England in 1991–1995; of manufacturing enterprises in England in 1973–1992; regarding the manufacturing enterprises in Ireland during 1973–1996; concerning manufacturing enterprises in the US in 1987–1996, respectively, affirm that the horizontal and backward linkages have a positive impact on productivity of local firms; yet, forward linkages create negative effects.

In terms of the industry-level data, the positive spillover effects increase productivity compared to the analysis of the micro-level data at enterprise level, diverse results of spillover effects are acknowledged. Blomström and Wolff (Citation1997) with Mexican industry data in 1970 and 1975; Kokko (Citation1996) with the study on Mexican industry; Kokko (Citation1996) with research on industrial results in Uruguay in 1990, Thuy (Citation2005) with Vietnamese industry data during 1995–1999 period and 2000–2002 period; Anwar and Nguyen (Citation2011) with Vietnamese industry data in 2000–2005 period recognize the positive impacts of FDI to local industry. In terms of the data of enterprises upon analyzing spillover effects of FDI to local firms, no similarity among countries is identified. Positive impacts could be seen from the research of Blomström and Sjöholm (Citation1999) who analyze the data of manufacturing firms in Indonesia in 1991; Kokko et al. (Citation2001) who examine business data in Uruguay in 1988; Görg and Strobl (Citation2003) who examine firm-level data in Ghana in 1991–1997. These studies state that the impact is not significant, listed as Kathuria (Citation2000) with data of manufacturing enterprises in India from 1976 to 1989. Additionally, some studies have detected a positive effect on those linkages but negatively reduced productivity on the others. Javorcik (Citation2004), with firm-level data Lithuania in 1996–2000, points out an increasing impact on horizontal linkages; backward linkages; and no significant effects on forward linkages. Blalock and Simon (Citation2009) studied Indonesian enterprises during 1988–1996 and discovers that horizontal linkages are not significant in affecting productivity, whereas backward linkages help to increase. In the recent years, some studies with Vietnamese firm-level data have been contradictory. Le et al. (Citation2021) with firm-level data from 2000 to 2005 demonstrate positive impacts of horizontal and backward linkages without any negative effects of forward linkages. Ni et al. (Citation2017) emphasize that the impact of horizontal linkages does likely reduce local firms’ productivity while the backward linkage adds values to increase.

The difference of empirical results of spillover effects is found in researches regarding the economies at different stages in both developed and developing countries (Kim & Choi, Citation2019; Meyer & Sinani, Citation2009; Salem & Ritab, Citation2022). The reason for this discrepancy can be explained due to the technology gap between the host country and FDI firms and the procrastination of new technology adoption (Le & Pomfret, Citation2011; Villar et al., Citation2020). Kokko (Citation1994) affirms that technology absorptive capacity and technology gap of domestic enterprises are those factors that influence the emergence of spillovers from FDI. Recently, some studies by Hamida (Citation2013) strongly confirms and clarifies by practical researches applied in different industries. It is shown that in the manufacturing and processing industry, domestic firms with high-tech potential benefits from spillover effects of FDI owe to increasing competitiveness whereas the enterprises with medium potential of technology tend to derive these benefits from the development of specialized production besides the enterprises with low technology development by making use of labor force of FDI firms. This study asserts that if local firms invest more in technology absorptive capacity enhancement, these local firms will receive huge positive spillover effects from FDI (Hamida, Citation2013; Hamida & Gugler, Citation2009; Villar et al., Citation2020).

2.2. Interaction between FDI and exports

Exporting is the simplest method for enterprises to join global market, which is to increase their productivity. Two types of exports are: passive and proactive exports. Passive exports occur when enterprises produce with domestic production in excess while proactive exports takes place when the company’s strategy aims to export. Sinking costs are an element attracting exporters (Bernard & Jensen, Citation2004). These costs encompass the setting of distribution system, market research, and product analysis for export (Bernard et al., Citation2006; Kneller & Pisu, Citation2007; Moralles & Moreno, Citation2020). With the advantage of deep understandings concerning the global markets and customers, local firms participating in export could learn from FDI enterprises. Knowledge spillovers from FDI can help local firms reduce the sinking costs (Aitken et al., Citation1997; Greenaway & Kneller, Citation2007) or the entry costs (Kneller & Pisu, Citation2007). Only a few enterprises with high labor productivity as well as productive efficiency could enter the export market due to their advantage of passing the sinking costs (Kneller & Pisu, Citation2007). Export spillovers from FDI to domestic firms are studied by Aitken et al. (Citation1997) who use panel data of Mexican enterprises between 1989 and 1990 and realize that horizontal linkages and being in the same region could increase productivity of domestic firms engaging in export. Kokko et al. (Citation2001), with cross-sectional data of manufacturing firms in Uruguay in 1998, state that their productivity is increased with export participation. From panel data of Spanish manufacturing enterprises from 1990 to 1997, Barrios et al. (Citation2003), based on Tobit Model, present export spillovers in accordance with R&D investment of FDI firms to export rate of local business. Ruane and Sutherland (Citation2005), analyzing panel data of manufacturing firms in Ireland in 1991–1998, expose positive impacts from FDI to local firms to their decision related to export participation as well as the export proportion to total revenue. Making use of the Heckman model and business data in the manufacturing industry in England in 1992–1999, Kneller and Pisu (Citation2007) analyze the impact through horizontal and vertical linkages to answer whether or not enterprises participate in export and how much can be exported. In the same research direction regarding horizontal and vertical linkages, Girma et al. (Citation2008) focus on the role of absorptive capacity; with manufacturing business data in England in 1992–1998, they research to explore the effect of horizontal and vertical linkages on two groups including exporters and enterprises targeting domestic market and claim that exporters have more positive impact than non-exporters. Benli (Citation2016) with manufacturing panel data in Turkey in 2003–2013 claims that spillover effects are only limited through backward linkages with new absorptive capacity for positive effects, whereas no impact by horizontal and vertical linkages and no competitive influence upon FDI firms entering the industry is identified and the sinking costs are high within the export market.

Although evidence of spillover in export is unclear, some studies report the positive spillovers in export (Aitken et al., Citation1997; Kneller & Pisu, Citation2007; Yohanes et al., Citation2022); neither impacts nor negative effects on spillovers (Barrios et al., Citation2003; Benli, Citation2016; Bernard & Jensen, Citation2004; Ruane & Sutherland, Citation2005). The results are different due to the dependence on the characteristics of local firms, industries, human capital or technology gap between FDI and host countries (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2014; Kneller & Pisu, Citation2007; Teamrat & Sun, Citation2022). Consequently, this study adds some practical understandings concerning the spillover effects of FDI on the aggregate productivity of domestic enterprises through export activities upon clarifying the role of horizontal, backward, and forward linkages and technology gap in the stage of economic integration.

3. Research model and data

Data used in this research, as a panel data set of 489,347 Vietnamese enterprises within the 2009–2015 period, is selected from the annual enterprise surveys of the General Statistics Office of Vietnam. The number of exporting enterprises accounts for 4.75% in the survey sample and the number of FDI enterprises accounts for 2.83%. Enterprises with survey data in this period have a surveyed export value that is suitable for research objectives; nevertheless, enterprise exports, from 2016 onwards, can only be studied through tax surveys. The Input-Output Table in 2012 is used to calculate horizontal and vertical linkages.

The empirical model used in this paper is developed in two stages. Stage one specifies a standard Cobb–Douglas model that can be used to estimate TFP. TFP is the dependent variable whereas FDI-related spillovers are the independent variables. In stage two, we also identify a number of control variables that can affect TFP while the focus of the empirical exercise is on the impact of FDI-related spillovers on TFP. The inclusion of the control variables in our regression equation serves to reduce the severity of omitted variable bias, which can reduce the reliability of the estimated results.

In stage one, TFP is calculated by Levinsohn and Petrin (Citation2003) method. Accordingly, the production technology is assumed to be Cobb-Douglas function. Stage two, in order to correctly estimate the impact of FDI-related spillovers on TFP, specifies an empirical model where FDI-related spillovers and other variables appear as independent variables. As all identified independent variables cannot be directly measured, following the existing literature, we use several proxies. Similar proxies are widely used in the existing literature (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2014; Javorcik & Spatareanu, Citation2011; Y. Wang, Citation2010).

For this note, the production technology is assumed to be Cobb—Douglas function:

=

+

+

+

+

ŋt

Demand for the intermediate input is assumed to depend on the firm’s state variables ωt and capital stock

:

Levinsohn and Petrin assumptions about the firm’s production technology, Levinsohn and Petrin that the demand function is monotonically increasing in .

LP write the sample residual of the production function as

And estimate of

is defined as the solution to

An additional moment condition is needed to identify separately from

. LP use the previous period’s level of material usage

as instruments applies the GMM estimator

Thus, with ≡ (

,

), one candidate estimator solves

Additional over identification conditions are given by

Accordingly, stage two, in order to correctly estimate the impact of FDI-related spillovers on TFP, specifies an empirical model where FDI-related spillovers and other variables appear as independent variables. As all identified independent variables cannot be directly measured, following the existing literature, we use several proxies. Similar proxies are widely used in the existing literature (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2014; Javorcik & Spatareanu, Citation2011; Y. Wang, Citation2010).

As shown in Table , Model 1 explains how the firm’s export participation impacts TFP. Model 2 assesses the TFP change of Vietnamese enterprises through export activities which appeared at least two times in panel data; then, further processing the three pervasive interaction variables (horizontal, backward, forward) with export activity (export intensity). In addition, the variables in the models are explained as presented in Table .

Table 1. Regression models

Table 2. Variables used in the study

4. Empirical results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

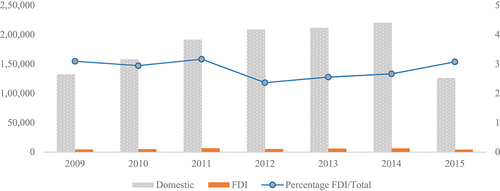

As shown in Figure , the number of enterprises in Vietnam increased gradually between 2009 and 2014. However, there was a decrease in 2015. The proportion of exporters in the total number of enterprises in Vietnam during this period changed over the years.

Meanwhile, Figure shows that the proportion of FDI enterprises in Vietnam tends to increase in the period 2012–2015. In fact, Vietnamese Government has policies to attract foreign direct investment during this period to contribute to the realization of economic growth goals.

4.2. Correlation analysis

Table presents the correlations among the variables. As a rule of thumb, a correlation of 0.70 or higher in absolute value may indicate a multicollinearity issue (Tran & Vo, Citation2022). Our results in Table denote that the correlation coefficient between all variables is lower than 0.7.

Table 3. The pairwise correlation coefficients

For definitions of the variables, see, Table .

This study utilizes modified Wald and Wooldridge tests to examine the group-wise heteroskedasticity and auto correlation in the two models in this study. The results in Table indicate that heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation do exist.

Table 4. Modified wald and wooldridge tests

We use Hausman (Citation1978) test to identify the appropriate model, with the null hypothesis (H0) is that the random-effects model is consistent and efficient. The results of Hausman test in Table decide the fixed-effect method, the estimates in this model are robust standard errors.

Table 5. Hausman test

4.3. The impact of absorbing productivity spillover on export ability

The results are presented in Table with corresponding for Model 1. It is shown that enterprises participating in exports have 43.5%, which is higher total productivity than those not participating in exports. This result is similar to that of the study by Salas et al. (Citation2022): enterprises participate in exporting with the purpose of increasing their TFP. However, the study also found that: the spillovers through horizontal linkages in the presence of FDI have no significant impact. Vertical linkages increase the supply to FDI enterprises by 1% whereas TFP decreases by 0.26% and forward linkages have no impact. This indicates the export-promoting spillover effect of FDI on domestic firms in emerging countries (Villar et al., Citation2020). Labor quality variables, HHI and Scale have estimated signs with previous research expectations (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2011). Labor quality variables, HHI and Scale have estimated signs with previous research expectations (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2014). In addition, the horizontal linkages have not recorded any impacts, whereas the backward linkages channel has a negative impact. However, export participation increased the impact of horizontal linkages on TFP by a growth of 0.44%. This result is different from that of the study by Lu et al. (Citation2017) which points out an effect through this linkage channel. This difference is explained by the differences within the development stages of the FDI-receiving countries (Meyer & Sinani, Citation2009). In terms of the backward channel, it decreased by 0.28% of TFP. Being negative backward, the export capacity of the backward channel helps reduce the negative impacts of the backward channel; in other words, the increase by 0.27% means that the export growth improves absorption through the supply of FDI goods. Forward channel has no significant effects on TFP; nevertheless, that an increase in exports causes a negative forward reduction of 0.15% implies that FDI enterprises can limit the spread of technology or productivity to Vietnamese corporate customers. In terms of exporting, it is possible that Vietnamese enterprises are less dependent on buying FDI enterprises but shifting to buying inputs from imported or Vietnamese enterprises.

Table 6. Estimated results of impacts to export participation—Model 1

To examine the impact of export roles more extensively and export activity on the TFP spillover effects, Table presents the estimated results of the Model 2. The increase in the export rate to 1% helps enterprises improve TFP by 0.015%. When participating in exports, the increase in supply for FDI enterprises through backward channel encourages domestic enterprises to increase total productivity by 0.49%. This result is consistent with that of the study by Kim and Xin (Citation2021), in which, domestic enterprises will benefit through backward linkages with FDI partners. Therefore, learning from the supply chain for FDI enterprises will help Vietnamese businesses upon participating in the world market in the context of deeper and deeper world integration. Meanwhile, the impact has not been recorded to decrease by 0.44% through cross-linking channels. In addition, horizontal linkages cause negative impacts on TFP by diminishing 0.54%, which results from competitive pressure of FDI firms in the same industry. However, with the export’s influence, it reduces these impacts by 0.29%. Recognizing the important impact for TFP of domestic enterprises through backward linkages, this channel helps exporting enterprises increase by 0.56% of their TFP. Nevertheless, promoting export and involving in backward linkages lessen by 0.16% of firms’ TFP due to their excessive spending on improving quality to fulfill the requirements of FDI enterprises. If enterprises reduce their technology gap by 1% to FDI firms, their TFP will increase by 0.075%.

Table 7. Estimated results of export ability and spillover effects to TFP of local firms—Model 2

4.4. Robustness check

The previous studies (Tran & Vo, Citation2022; Van et al., Citation2022) have confirmed that the fixed-effect method does not guarantee validity while the model exists autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity. This paper, to overcome this problem, utilizes the generalized method of moments (GMM) method. From the results of Column 1 of Table , the export participation has a positive effect on productivity with a positive impact coefficient (δ2 = 0.29). This effect is consistent with the results above as export participation increases the TFP of domestic firms. The spillover through cross-linking on the productivity of exporting enterprises helps to increase productivity as well as the interaction variable (Exp*Hor) has a positive impact coefficient (δ6 = 2.89). From Column 2, the higher export capacity the domestic enterprises are, the more FDI enterprises learn in the same industry. The fact that the interaction variable (ExI*Hor) has a positive impact coefficient (δ6 = 4.3) is statistically significant.

Table 8. Estimated results of export ability and spillover effects to TFP of local firms—with GMM technique

5. Conclusions and policy implications

This paper contributes to the existing Literature review on the impact of joining exports on spillovers arising from the linkages generated by FDI between domestic and foreign firms. Recent studies have suggested that the export performance of domestic firms may be affected by horizontal and vertical linkages (Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2011; Kim & Xin, Citation2021; Kneller & Pisu, Citation2007). The study clarifies the effect of learning on the aggregate productivity of domestic firms through exports and the association with FDI firms’ spillover effects, in the context of a developing country actively integrating deeply into the world market and increasing investment attraction for development (Villar et al., Citation2020).

That the research provides further evidence of the spillover effects of FDI to domestic enterprises through export ability is very crucial to a developing country like Vietnam where the FDI sector accounts 71% of total exports. The results show that export participation of local firms not only promotes the productivity of enterprises but spurs an improvement in productivity spillover absorption from the FDI in the same and downstream industries, equivalent to 0.44% and 0.27%, respectively. Due to the selection effect, firms participating in exports are likely to be more efficient to minimize the competition effect and take advantage of the supplying relationship with FDI partners.

More interestingly, for local exporters, those with higher share of industry exports, which represent the higher export ability, will lessen their limited leaning ability from the foreign competitors. The fact that they perform better than non-exporters when taking advantage of the positive backward effect means that they can absorb the spillover from selling to foreign buyers. However, the higher their export ability is, the lower this spillover is. It is possible that the strong exporter may put more attention to international buyers in the world market than the FDI sector, or vice versa. The FDI can have low demand from these companies’ products and prevent the possible technology leakage. The forward channel is found to leave no impact on Vietnamese firms’ productivity.

From the above results, policymakers should create incentives and transparent mechanisms to foster local firms in export participation. They can create a legal consultancy center for exporting enterprises in different markets, which are easy for them to participate in global market easily. Furthermore, the government and the local enterprises need to increase business training on practical knowledge in exporting in order to cut down market entry costs and increase opportunities for firms to export their goods. Human resources of Vietnamese enterprises are currently equipped with inadequate and insufficient knowledge in export commodity as well as their ability to find trading partners. Consequently, the market entry cost of Vietnamese enterprises is being high and their operation faces limitation in effectiveness.

Regarding the local enterprises, some proposals are as follows. Firstly, they should pay attention to invest in labor quality and technology to reduce the gap with leading companies. Secondly, it should be improving learning and job quality standards to participate in the supply chain of FDI firms. The government needs to support capital to help local firms invest more heavily in technology research, create a legal sharing center about technology to help enterprises participate in exporting and learning and also improve the quality of domestic human resources. Because of low quality of human resources and the scarcity of high-quality labor supply, it is difficult to conduct R&D activities in Vietnamese enterprises. Therefore, improving the quality of domestic human resources is one of the right and necessary directions for Vietnam to be able to enhance the positive spillover effects from FDI to exports of manufacturing and processing industries through technology transfer, knowledge sharing, learning experience, and labor movements.

Moreover, the government should encourage domestic enterprises to actively seek foreign partners for business cooperation. Being proactive in finding partners helps firms in the industry to plan their business strategy actively, leading to appropriate and more effective preparations for connecting with foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in the industry. This is the basis for firms in the industry to be able to actively obtain spillover effects from FDI. The government should create promising conditions for foreign enterprises to succeed in looking for domestic trade partners, and also organize regular events as a bridge for foreign investors to approach the local business community. Through the activities of FDI management groups, trade and investment promotion organizations, technology exhibitions, seminars, etc., foreign investors can gain more information about the domestic manufacturing enterprises in their field of operation, which helps them easier to find cooperative partners in Vietnam.

Last but not least, this research paper has some limitations. First, this study has not been separated into low- and high-tech industries because FDI enterprises, upon investing in developing countries, will focus on a number of industries with advantages. Further research should clarify the impact of export spillovers of FDI enterprises on the TFP of local enterprises under the institutional influence of the host country. Second, this study has not assessed the effect of origin of FDI on spillover effects of domestic firms’ TFP in the receiving country. Countries with high technological prowess will have different effects on export spillovers (Kim & Xin, Citation2021; Ni et al., Citation2017). Therefore, further studies can examine the effect of FDI origin on firm’s TFP spillover, how FDI coming from developed and developing countries will affect the ability of domestic enterprises to export. Third, this study only studies the spillover effects on those enterprises in one particular emerging country; therefore, further research needs to study in more diverse countries in the similar developing group classification as well as to expand the diversity effects of FDI. Fourth, it will be more interesting to understand the spillover effects and absorptive capacity of businesses in terms of the contexts of pre- and post-national accession to the WTO, the US and China Trade Wars.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pham Thi Bich Ngoc

Pham Thi Bich Ngoc is a senior lecturer of the International School of Business, University of Economics HCMC, Vietnam; former Dean of Faculty of Logistics- International Trade/ former director of Institute of Development and Applied Economics, Hoa Sen University, HCMC. Her researches have been published in more than 5 articles listed as: Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Asian Journal of Economics and Banking. Email: [email protected]

Pham Dinh Long is Associate Professor of Economics, a senior lecturer of the International School of Business, University of Economics HCMC, Vietnam; former Vice Provost of Binh Duong Economic and Technology University. His researches have been published in more than 5 articles listed as: Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Email: [email protected]

Pham Dinh Long

Pham Thi Bich Ngoc is a senior lecturer of the International School of Business, University of Economics HCMC, Vietnam; former Dean of Faculty of Logistics- International Trade/ former director of Institute of Development and Applied Economics, Hoa Sen University, HCMC. Her researches have been published in more than 5 articles listed as: Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Asian Journal of Economics and Banking. Email: [email protected]

Pham Dinh Long is Associate Professor of Economics, a senior lecturer of the International School of Business, University of Economics HCMC, Vietnam; former Vice Provost of Binh Duong Economic and Technology University. His researches have been published in more than 5 articles listed as: Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Email: [email protected]

Huynh Quoc Vu

Huynh Quoc Vu is a PhD candidate/researcher at Ho Chi Minh City Open University, Vietnam.

References

- Aitken, B., Hanson, G. H., & Harrison, A. E. (1997). Spillovers, foreign investment, and export behavior. Journal of International Economics, 43(1–2), 103–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(96)01464-X

- Anwar, S., & Nguyen, L. P. (2011). Foreign direct investment and export spillovers: Evidence from Vietnam. International Business Review, 20(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.11.002

- Anwar, S., & Nguyen, L. P. (2014). Is foreign direct investment productive? A case study of the regions of Vietnam. Journal of Business Research, 67(7), 1376–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.015

- Barrios, S., Görg, H., & Strobl, E. (2003). Explaining firms’ export behaviour: R&D, spillovers and the destination market. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 65(4), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.t01-1-00058

- Benli, M. (2016). FDI and export spillovers using Heckman’s two step approach: Evidence from Turkish manufacturing data. Theorical and Applied Economics, 23(4), 315–342. https://store.ectap.ro/articole/1241.pdf

- Bernard, A. B., & Jensen, J. B. (2004). Why some firms export. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(2), 561–569. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465304323031111

- Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., & Schott, P. K. (2006). Trade costs, firms and productivity. Journal of Monetary Economics, 53(5), 917–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2006.05.001

- Blalock, G., & Simon, D. H. (2009). Do all firms benefit equally from downstream FDI? The moderating effect of local suppliers’ capabilities on productivity gains. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.21

- Blomström, M., & Kokko, A. (1996). The impact of foreign investment on host countries: A review of the empirical evidence. Policy Research Working Paper, 1745. World Bank.

- Blomström, M., & Sjöholm, F. (1999). Technology transfer and spillovers: Does local participation with multinationals matter? European Economic Review, 43(4–6), 915–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00104-4

- Blomström, M., & Wolff, E. N. (1997). Growth in a dual economy. World Development, 25(10), 1627–1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00058-2

- Bruno, R. L., & Cipollina, M. (2018). A meta‐analysis of the indirect impact of foreign direct investment in old and new EU member states: Understanding productivity spillovers. The World Economy, 41(5), 1342–1377. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12587

- Dieppe, A. (Ed.). (2021). Global productivity: Trends, drivers, and policies. World Bank Publications.

- Driffield, N. (2001). The impact on domestic productivity of inward investment in the UK. The Manchester School, 69(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9957.00237

- General Statistics Office. (2020). https://www.gso.gov.vn/default.aspx?tabid=716

- Girma, S. (2005). Absorptive capacity and productivity spillovers from FDI: A threshold regression analysis. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 67(3), 281–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2005.00120.x

- Girma, S., Görg, H., & Pisu, M. (2008). Exporting, linkages and productivity spillovers from foreign direct investment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 41(1), 320–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.00465.x

- Glass, A. J., & Saggi, K. (2002). Intellectual property rights and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Economics, 56(2), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(01)00117-9

- Görg, H., & Greenaway, D. (2004). Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign investment? World Bank Research Observer, 19(2), 171–197. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkh019

- Görg, H., & Strobl, E. (2003). Multinational companies, technology spillovers and plant survival. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 105(4), 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0347-0520.2003.t01-1-00003.x

- Greenaway, D., & Kneller, R. (2007). Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment. The Economic Journal, 117(517), F134–F161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02018.x

- Hamida, L. B. (2013). Are there regional spillovers from FDI in the Swiss manufacturing industry? International Business Review, 22(4), 754–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.08.004

- Hamida, L. B., & Gugler, P. (2009). Are there demonstration-related spillovers from FDI?: Evidence from Switzerland. International Business Review, 18(5), 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.06.004

- Haskel, J. E., Pereira, S. C., & Slaughter, M. J. (2007). Does inward foreign direct investment boost the productivity of domestic firms? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3), 482–496. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.89.3.482

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 46(6), 1251–1271. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913827

- Huynh, H. T. N., Nguyen, P. V., Trieu, H. D. X., & Tran, K. T. (2019). Productivity spillover from FDI to domestic firms across six regions in Vietnam. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 57(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1562892

- Imbriani, C., Pittiglio, R., Reganati, F., & Sica, E. (2014). How much do technological gap, firm size, and regional characteristics matter for the absorptive capacity of Italian enterprises? International Advances in Economic Research, 20(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-013-9439-7

- Iršová, Z., & Havránek, T. (2013). Determinants of horizontal spillovers from FDI: Evidence from a large meta-analysis. World Development, 42, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.07.001

- Javorcik, B. S. (2004). Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. American Economic Review, 94(3), 605–627. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041464605

- Javorcik, B. S., & Spatareanu, M. (2011). Does it matter where you come from? Vertical spillovers from foreign direct investment and the origin of investor. Journal of Development Economics, 96(1), 126–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.05.008

- Kathuria, V. (2000). Productivity spillovers from technology transfer to Indian manufacturing firms. Journal of International Development, 12(3), 343–369. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328(200004)12:3<343::AID-JID639>3.0.CO;2-R

- Keller, W. (1996). Absorptive capacity: On the creation and acquisition of technology in development. Journal of Development Economics, 49(1), 199–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(95)00060-7

- Keller, W., & Yeaple, S. R. (2003). Multinational enterprises, international trade, and productivity growth: Firm-level evidence from the United States. NBER Working Paper 9504. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, MA.

- Kim, M., & Choi, J. M. (2019). R&D spillover effects on firms’ export behavior: Evidence from South Korea. Applied Economics, 51(28), 3066–3080. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1564120

- Kim, M., & Xin, D. (2021). Export spillover from foreign direct investment in China during pre-and post-WTO accession. Journal of Asian Economics, 75, 101337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2021.101337

- Kneller, R., & Pisu, M. (2007). Industrial Linkages and export spillovers from FDI. The World Economy, 30(1), 105–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00874.x

- Kokko, A. (1994). Technology, market characteristics, and spillovers. Journal Of Development Economics, 43(2), 279–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(94)90008-6

- Kokko, A. (1996). Productivity spillovers from competition between local firms and foreign affiliates. Journal of International Development, 8(4), 517–530. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328(199607)8:4<517::AID-JID298>3.0.CO;2-P

- Kokko, A., Zejan, M., & Tansini, R. (2001). Trade regimes and spillover effects of FDI: Evidence from Uruguay. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 137(1), 124–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02707603

- Kuswardana, I., Nachrowi, D. N., Falianty, A. T., & Damayanti, A. (2021). The effect of knowledge spillover on productivity: Evidence from manufacturing industry in Indonesia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1923882. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1923882

- Le, Q. H., Do, A. Q., Pham, C. H., & Nguyen, D. T. (2021). The impact of foreign direct investment on income inequality in Vietnam. Economies, 9(27), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9010027

- Le, H. Q., & Pomfret, R. (2011). Technology spillovers from foreign direct investment in Vietnam: Horizontal or vertical spillovers? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 16(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2011.564746

- Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. The Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-937X.00246

- Lu, Y., Tao, Z., & Zhu, L. (2017). Identifying FDI spillovers. Journal of International Economics, 107, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.01.006

- Meyer, K. E., & Sinani, E. (2009). When and where does foreign direct investment generate positive spillovers? A meta-analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1075–1094. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2008.111

- Moralles, H. F., & Moreno, R. (2020). FDI productivity spillovers and absorptive capacity in Brazilian firms: A threshold regression analysis. International Review of Economics & Finance, 70, 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2020.07.005

- Ni, B., Spatareanu, M., Manole, V., Otsuki, T., & Yamada, H. (2017). The origin of FDI and domestic firms’ productivity—Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Asian Economics, 52, 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2017.08.004

- Ruane, F., & Sutherland, J. (2005). Export performance and destination characteristics of Irish manufacturing industry. Review of World Economics, 141(3), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-005-0038-4

- Salas, N. A., Alvarez, I., & Cantwell, J. (2022). Two-way knowledge spillovers in the presence of heterogeneous foreign subsidiaries: Evidence from an emerging country. International Journal of Emerging Markets. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-11-2021-1690

- Salem, A. Z., & Ritab, A. (2022). Revisiting volatility spillovers in the gulf cooperation council. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2031683. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2031683

- Teamrat, K. G., & Sun, Y. (2022). The foreign direct investment-Export performance nexus: An ARDL based empirical evidence from Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2009089. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.2009089

- Thuy, L. T. (2005). Technological spillovers from foreign direct investment: The case of Vietnam. School of Economics, University of Tokyo: School of Economics.

- Tran, N. P., & Vo, D. H. (2022). Do banks accumulate a higher level of intellectual capital? Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 23(2), 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-03-2020-0097

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2021). World Investment Report 2021: INVESTING IN SUSTAINABLE RECOVERY. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/wir2021_en.pdf

- Van, L. T. H., Vo, D. H., Hoang, H. T. T., & Tran, N. P. (2022). Does corporate governance moderate the relationship between intellectual capital and firm’s performance? Knowledge and Process Management, 29(4), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.1714

- Villar, C., Mesa, R. J., & Barber, J. P. (2020). A meta-analysis of export spillovers from FDI: Advanced vs emerging markets. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 15(5), 991–1010. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOEM-07-2019-0526

- Wang, J. Y. (1990). Growth, technology transfer, and the long-run theory of international capital movements. Journal of International Economics, 29(3–4), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1996(90)90033-I

- Wang, Y. (2010). FDI and productivity growth: The role of inter-industry linkages. Canadian Journal of Economics, 43(4), 1243–1272. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5982.2010.01613.x

- Yohanes, M. D., Wihana, K. J., Samsubar, S., & Evita, H. P. (2022). Why do some regions exhibit a greater degree of manufacturing export and entrepreneurship activities than others? Evidence from Indonesia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2037251. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2037251