?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Africa is one of the continents with the least inclusive finance. However, with increasing use of mobile phones for financial services or financial technology (Fintech), there are improved opportunities to ‘bank the unbanked”. Also, there is a significant increase in both the presence of foreign banks and Fintech usage. Hence, we examine the moderating role of foreign bank presence on the Fintech-inclusive finance nexus over the period, 2000–2018. The results show that foreign bank presence does not directly affect inclusive finance, but increases the link between Fintech and inclusive finance. We recommend that African countries need to provide the conducive environment improving the use of Fintech.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The paper examined how ICT can be used to improve the access of financial products to all the populace (Fintech) in an effective and efficient manner. We looked at how the influx of foreign banks into Africa can improve the access of financial products to all the populace. Our empirical results suggested that indeed, using ICT such as using mobile phone to send money and paying bills can help the poor, those living in the rural and other stakeholders to get access to financial products efficiently and effectively. However, we found that the inflow of foreign banks into Africa form synergies with Fintech to enhance efficient and effective access to financial products.

1. Introduction

As one of the accelerating goals of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), financial inclusion (henceforth inclusive finance) has always been a priority for most underdeveloped economies. Inclusive finance is when businesses and individuals have the opportunity to obtain sustainable financial products including inter alia, savings, micro-credit, payment, remittances, insurance of which a transaction account is considered as a foundation (World Bank, Citation2018). It can also be seen as a key empowering influence to decreasing poverty and inducing economic welfare. Despite the fact that policy makers stress the role of inclusive finance, a huge number of adults across the world are excluded from access to formal financial administrations (World Bank, Citation2018). For instance, about one- third of adults (1.7 billion) still do not have a bank account, and these are mostly women and poor people in rural areas (World Bank, Citation2018). Also, most markets in least developed economies are associated with information asymmetry which causes large financial institutions to cream skim in allocating financial services (Gormley, Citation2010; Sengupta, Citation2007).

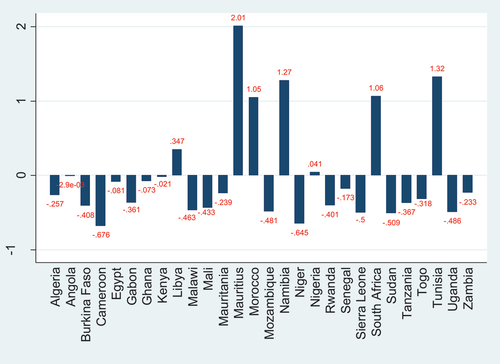

Furthermore, majority of the population has insufficient official documents and information to access financial services and Africa is often associated with the problem of information-deficient borrowers (Léon & Zins, Citation2020). As a result, the region is one of the least financially inclusive areas in the world (Zins & Weill, Citation2016). In other words, while Africa is undergoing several changes in the financial sector, it has less inclusive finance than other continents (Beck et al., Citation2015; Chikalipah, Citation2017; Kebede et al., Citation2021). Unlike other developing regions such as Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) recorded the least financial participation indicators between 2011 and 2014 (Fouejieu et al., Citation2020). Additionally, while 63% of adults held accounts in developing economies as at 2017, only 4% was attributed to SSA (Demirguc-Kunt et al., Citation2018). The African sample presented in Figure also shows that Africa is underperforming as far as inclusive finance is concerned.

For instance, in Figure , it can be seen that on average only one country (Mauritius) has 2.1% access to financial services, whereas most of the countries used for the study have below 2.1% access to financial services. Hence, it is imperative to identify ways to induce inclusive finance in these countries. As a result, the G20 policy aims to increase access to finance globally by implementing its high-level principles of digitally inclusive finance (World Bank, Citation2018). Digitally inclusive finance which is also called financial technology (Fintech), advanced from information technology which incorporates the internet, smartphones and other technological devices which enhance faster and cheaper delivery of financial services (Batunanggar, Citation2019). In terms of innovation, Fintech can be classified as (i) payment, settlement and clearing (ii) electronic aggregator (iii) risk and investment management, and (iv) peer lending (Aba & Linardy, Citation2021). Fintech provides comfort and convenience for users with the goal to make financial services more convenient to use. These services aid more people to easily get access to financial services at lower cost even in rural areas (Dabla-Norris et al., Citation2015; Ozili, Citation2018; Zetzsche et al., Citation2017).

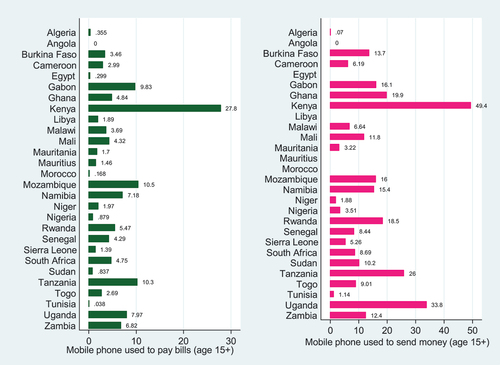

In SSA for instance, mobile money account ownership rose from 12% to 21% (World Bank, Citation2018), therefore offering women and the poor in the rural areas to get access to financial services in a more convenient way and at a low cost of use. Since the use of mobile phones has increased, it can be assumed that there are greater opportunities for the unbanked to be banked (Maurer, Citation2012). Therefore, countries with high mobile money accounts, are more accessible to financial services, thus the need for Fintech (World Bank, Citation2018). This study is necessary in Africa because Fintech is emerging in this continent. For instance, as shown in Figure , most countries use mobile phones to transfer money and settle bills.

Also, there are some Fintech companies and application platforms in Africa (see, Table ). These platforms over time have increased and have presented financial resources in their simplest form to the populace in Africa. For instance, countries such as Kenya, Nigeria, Ghana, Tanzania and Uganda have head offices of these Fintech companies that provide financial services to the poor, those in rural areas and other stakeholders (see, Table ).

Table 1. Some Fintech companies and platforms in Africa

Also, the Coronavirus Diseases 2019 (COVID-19) has led to a greater adoption and usage of Fintech. There has been growth in the adoption of pure-play lending apps in emerging markets and developing economies which includes Africa in times of COVID-19 (Fu & Mishra, Citation2022). Therefore, one of the questions this study seeks to answer is “can the evidence of these Fintech increase inclusive finance in Africa?”

Furthermore, the banking sector, one of a country’s conventional and conservative sectors, has been confronting difficulties with, possibly disruptive, technology-based development and internet-based solutions (Navaretti et al., Citation2018). To lessen these challenges, most Fintech companies have developed more user-friendly advanced applications in the banking enterprises, prompting an increased use of Fintech (Kohtamäki et al., Citation2019). Additionally, some banks have invested more in innovation in order to provide financial services through digital applications (Navaretti et al., Citation2018). This aids the banking sector to be involved in Fintech. For instance, in Africa, banks engage in the provision of mobile money services through linking mobile money accounts to bank accounts.

However, it has been suggested that, foreign banks are known to be more engaged in Fintech than the domestic banks. For example, in Ghana, AFB bank (Azerbaijan bank) has partnered with MTN mobile money to provide loans (Qwick Loan) to the users of MTN mobile money (Bucker, Citation2021). Since foreign banks are seen to be involved in Fintech and Africa has more share of foreign bank (Beck et al., Citation2014; Léon, Citation2016), can foreign banks act as catalyst to induce Fintech to further improve inclusive finance in Africa? Even the African sample present evidence that foreign banks have a greater share (more than 50%) in the banking sector in Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Tanzania and Zambia. This therefore raises concern as foreign banks move to host countries with adequate capital, modern banking regulations, best in obtaining customer’s among others. Aside from foreign banks serving as catalyst to help Fintech to induce inclusive finance, another concern is; are these banks helpful in improving inclusive finance?

Conspicuously, we identified scant empirical studies on the direct nexus between Fintech and inclusive finance. For example, Demir et al. (Citation2022) found that Fintech had a positive effect on inclusive finance in Africa. Although there are studies such as Jack and Suri (Citation2011), Mbiti and Weil (Citation2015), Ghosh (Citation2016), Gosavi (Citation2018), and Tchamyou et al. (Citation2019), most of these studies are focused only on cell phones usage. While there is evidence for greater cell phone use, it does not specify whether the phones were used for financial services. The fact that people are using mobile phones doesn’t guarantee that they use such phones for financial services. Hence, the current study used mobile phones used for paying bills and sending money as a measure of Fintech. In terms of the measurement of inclusive finance, most studies apart from Kebede et al. (Citation2021) and Anarfo et al. (Citation2020) used a single indicator as a proxy. However, it has been seen that, inclusive finance has no less than two principal estimations: demand side variables (utilization) and supply side components (access) (Chakrabarty, Citation2012; Shah & Dubhashi, Citation2015). To capture both the demand and supply sides, the current study agrees with the study of Anarfo et al. (Citation2020)Footnote1 and generated inclusive finance index as a measure of inclusive finance.

The study complements the literature by empirically testing the role of Foreign Bank Presence (FBP) on the nexus between Fintech and inclusive finance in Africa. We also depart from using a single indicator as a measure of inclusive finance and focus on both the demand and supply side of inclusive finance in Africa. In addition, we employ quantile regression as the estimation technique to see which quantile of inclusive finance is induced by Fintech and FBP. The findings are relevant for policy makers since they will know which policies to formulate to engage foreign banks in inclusive finance. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the extant literature; Section 3 describes the methodology; Section 4 includes discussion of the results, and finally section 5 includes the conclusion and policy implications.

2. Literature review

McKinnon (Citation1973) and Shaw (Citation1973) financial inclusion theory was used as the underpinning theory, which stresses the elimination of controls on interest rates and allows the real rate of interest to increase to an equilibrium (where investment = savings). When interest rates reduce, investments will increase, which in turn induces the average productivity of capital. Also, when the required reserve is reduced, it reinforces the effects of higher savings on the supply of bank lending. In a nut shell, McKinnon (Citation1973) pointed out the relevance of the policy of financial liberalization in decreasing financial constraints, improving the proficiency of financial mediators and boosting macroeconomic execution. However, Arestis and Demetriades (Citation1997) argue that the events following the financial reforms do not provide much support for the theory of financial liberalization. The intuition of this assertion can be attributed to some pre-condition for financial reform. For instance, Villanueva and Mirakhor (Citation1990) showed that an important precondition for financial inclusion include macroeconomic stability whereas Honohan (Citation2004) also argue that institutional quality (good governance and quality institution) is a precondition for financial reforms. Voghouei et al. (Citation2011) also point out that proper sequencing of financial liberalizationFootnote2 is another precondition for financial reform.

Empirical studies regarding the nexus between Fintech and financial inclusion show positive relationship with the exception of some few studies. For example, Jack and Suri (Citation2011), Mbiti and Weil (Citation2015), Ghosh (Citation2016), Gosavi (Citation2018), and Tchamyou et al. (Citation2019) identified that inclusive finance is related to more significant levels of Fintech and ICT. For instance, Andrianaivo and Kpodar (Citation2012) and Ghosh (Citation2016) showed that cell phone penetration enhances inclusive finance. There is, additionally, proof of a positive connection between the utilization of mobile money from one perspective and the financial investment of families and organizations on the other. Moreover, Jack and Suri (Citation2011), Mbiti and Weil (Citation2015), Morawczynski (Citation2009) and Ouma et al. (Citation2017) contend that households with versatile cash accounts are more likely to join a bank, pay/send to some extent, and collect more cash. Mobile money has been seen to induce SMEs’ access to financial service through the provision of bank advances (e.g., Gosavi, Citation2018).

However, Peruta (Citation2018) has shown that Fintech is a hindrance to financial inclusion. A study by Demir et al. (Citation2022) showed that Fintech induces inclusive finance using ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation and 140 countries as a sample size. This study proxy Fintech with mobile phones used to pay bills whilst they used three different indicators for inclusive finance (i.e., account, savings and borrowing) and was referred to demand side of inclusive finance. They concluded that despite the proxy (i.e., account, savings and borrowing) of inclusive finance, Fintech still enhances inclusive finance.

Likewise, there is the evidence that expanding access to microcredit significantly advances entrepreneurship and investment, allowing current private companies to develop (Banerjee et al. Citation2015). The essential wellspring of inclusive finance is the banking sector. Regardless of such extension of formal banking channels, admittance to the credit market is as yet one of the challenging areas for less well-off individuals driving a considerable number of them towards the subprime credit market (Credit Companies) with higher yearly loan costs (Collard & Kempson, Citation2005). Foreign banks might set out open doors for new business visionaries by eliminating obstructions to access and improving business sector competition (Zingales & Rajan, Citation2003).

Studies on FBP and the measurement of inclusive finance can be in two forms. For example, in the first form, inclusive finance was proxied with the scope of the banking involvement (see, Beck et al., Citation2007; Detragiache et al., Citation2008; Beck & Peria, Citation2010; Memon et al., Citation2021; Kebede et al., Citation2021; Demir et al., Citation2022). Detragiache et al. (Citation2008) used panel data for 2003–04 for 18 low-income countries whilst the ratio of bank credit to the private sector (% GDP) was used as a measure of inclusive finance. Their results showed that any level of foreign bank presence decreases inclusive finance in low-income countries. Although Beck et al. (Citation2007) used a different sample of 99 countries 2003–04, where inclusive finance was measured with branch penetration, ATM penetration, loan account and deposit account, they found similar results as that of Detragiache et al. (Citation2008). Beck and Peria (Citation2010) used share of municipality branches, branches per 100,000 people, deposit account per 1000 people and loan account per 1000 people as a proxy for inclusive finance and also had similar results, that presence of foreign banks in Mexico impeded inclusive finance. Kebede et al. (Citation2021) also focused on the role of institutional quality on FBE-inclusive finance nexus in Africa. Their findings suggest that high FBP per se leads to low inclusive finance whereas in the presence of institutional quality, FBP induces inclusive finance. Kebede et al. (Citation2021) used multidimensional inclusive finance which captures both usage and access variables. However, contradictory results were obtained by Memon et al. (Citation2021) who identified that FBP induced inclusive finance, when inclusive finance was measured with the usage of ATM per 1000 adults.

The second way of measuring inclusive finance by foreign bank studies utilized miniature aspect, which centers around the genuine effect of foreign banks on access to credit by both firms and households. For example, Léon and Zins (Citation2020) examined the presence of regional foreign bank (Pan-African bank) and inclusive finance, where their findings suggest that regional FBP increases financial inclusiveness. They used, for example, factors such as access to corporate credit (choice of company to apply for an advance, choice of bank to obtain an advance, loan terms), and access to household loans as a proxy for inclusive finance. It was reported by some authors, for example, Clarke et al. (Citation2006), Beck and Brown (Citation2015), Gormley (Citation2010) that, foreign banks generally select a sub-set of the borrowers who are low risk and extend credit facilities to such borrowers. They termed this act as “cherry-picking” and this behavior of the foreign banks reduces inclusive finance and deny small firms the opportunity to access financial resources.

In summary, it can be seen that most studies on inclusive finance focused more on the demand side whilst few paid attentions to the supply side. Also, individual indicators of inclusive finance were considered among most, which does not capture the multifaceted nature of inclusive finance. Additionally, the moderation role of FBP on the nexus between Fintech and inclusive finance is hard to find most especially in Africa. Therefore, we fill this gap by examine the moderation role of FBP on the nexus between Fintech and inclusive finance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Empirical strategy

Financial liberalization seeks to allow access of financial resources to every citizen in a nation without any constraints. Therefore, for these to be possible, there are some factors as suggested by McKinnon (Citation1973) and Shaw (Citation1973) which influence financial liberalization. Among these factors include entry of foreign banks, Fintech, institutions, bank-specific characteristics and some macroeconomic variables (Detragiache et al., Citation2008; Beck et al., Citation2007; Beck & Peria, Citation2010; Memon et al., Citation2021; Kebede et al., Citation2021; Demir et al., Citation2022). Following these theoretical and empirical studies, we utilised some of these variables due to availability of data and African characteristics as presented in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) .

Where IFI is inclusive finance index, Fintech is financial technology, BS is bank spread, COM is competition, BC is bank concentration, InstQ is institutional quality, Edu is education, Pop is population growth, and STAB is bank stability.

Since most foreign banks engage in using digital application to provide services, we empirically test if FBP matters in the nexus between Fintech and inclusive finance. Hence, we specify the model by including FBP and the interactive term of Fintech and FBP to Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) as shown below;

Where FBP is foreign bank presence and the rest of the variables are defined above.

We took a partial differential of Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) with respect to Fintech to obtain the net effect of Fintech on inclusive finance as shown in Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3)

Where = the mean value of foreign bank presence

We used a quantile regression method in estimating our regression, which helped to determine the effect of Fintech on all levels of inclusive finance. The quantile regression methodology considers relationships between variables outside the mean of the data, which makes it valuable to understand the results of abnormal distribution between the variables under study (Le Cook & Manning, Citation2013). The following are the situations in which quantile regression are appropriate to use (Koenker & Hallock, Citation2001), (i) when the error terms are not necessarily constant across a distribution which violates the assumption of homoscedasticity, then quantile regression will be the best estimation technique to use. (ii) If an estimation focuses on the mean as a measure of location, then the information about the tails of distribution is lost. (iii) Outliers in a data set could provide inconsistent results if we use estimation techniques other than quantile regression. Hence, it will be laudable to use quantile regression estimation technique when interested in other information of the variable. We estimated our quantile regression as follows;

Where: =

conditional quantile of inclusive finance

on the various independent variables = the coefficients to be estimated for the different quantile of inclusive finance (i.e., 25th 50th 75th and 90th).

= conditional distribution function of inclusive finance.

= error term where

= 0. We used a bootstrap method of quantile regression to estimate our parameters as proposed by the following studies (Buchinsky, Citation1995, Citation1998; Efron, Citation1981). 1000 bootstrap replications are adopted because it computes robust parameters (Buchinsky, Citation1995).

3.2. Data and description

We employed annual data for 28 African countriesFootnote3 for 19 years spanning 2000 to 2018 due to the availability of data. As shown in Table , six variables were used to construct the Inclusive Financial Index (IFI). We also use two different proxies for Fintech such as cell phones used to make payments (age 15+) and cell phones used to send money (age 15+) as shown in Table . As a measure of the FBP, we used the percentage of assets of foreign banks in relation to the total assets of universal banks (see, Table ).

Table 2. Data and description of variable

We used some set of control variables as suggested by literature (see, Anarfo et al., Citation2020; Dabla-Norris et al., Citation2015; Demir et al., Citation2022; Didier & Schmukler, Citation2013; Kebede et al., Citation2021; Rojas-Suárez, Citation2016; Rousset et al., Citation2021). However, all control variables of inclusive finance were not utilized due to the availability of data and region’s characteristics. The control variables include; bank competition, bank spread, bank concentration, institutional quality, bank stability, education and population growth. Boone indicator is used to measure banks competition (see, Anarfo et al., Citation2020; Kebede et al., Citation2021) and sourced from GFD. The rationale behind the indicator is that higher profits are made by more efficient banks, therefore efficient bank will be willing to provide financial resources at a low cost which will then increase the demand for financial service. We proxy bank spread with bank lending-deposit spread which is sourced from GFD as displayed in Table . Since high levels of lending-deposit may decline inclusive finance, we utilized lending-deposit spread (%) in the case of African settings. Bank concentration (%) was employed as a measure of bank concentration (see, Didier & Schmukler, Citation2013; Rousset et al., Citation2021). This variable is relevant for the study because an increase in inclusive finance is associated with high levels of bank concentration.

We considered population growth based on the extant literature that when there is increase in population growth, inclusive finance will reduce, hence, we used population growth rate (% annual) as a proxy for population changes as presented in Table . We utilized an average of six indicators of institutional quality to make a composite institutional quality index (Nawaz et al., Citation2014). These six (6) indicators include 1. corruption control, 2. rule of law, 3. government effectiveness, 4. quality of regulation, 5. political stability and absence of violence, and 6. voice and accountability. We consider institutional quality as a control variable due to its effect on the access to financial resources (Dabla-Norris et al., Citation2015; Rojas-Suárez, Citation2016) and was collected from the WGI. Another reason for using institutional quality is its ability to ensure efficient allocation of financial resource (Nanivazo et al., Citation2021; Dabla-Norris et al., Citation2015; Rojas-Suárez, Citation2016). When people attain higher education, the more likely they will get access to all financial resources (see, Zins & Weill, Citation2016; Allen et al., Citation2016; Fungáčová & Weill, Citation2015). Therefore, we utilized education as part of the predictors for the study and proxied it with secondary school enrolment. The stability of financial sector builds confidence for the financial sector which reduces fear and panic of depositors. Based on that premise and extant literature, we controlled for banks’ stability and proxied it with bank’s Z-score (Anarfo et al., Citation2020).

4. Discussion of empirical results

We showed the behavior of the data, which is presented in Table . The results showed that our inclusive finance index has an average value of 7.91e-07 with the minimum value of -0.90 and 4.66 as the maximum value (glimpse Table ). This suggests that on average, the 28 countries have low inclusive finance because the mean value falls within the low range of the index. On country level, we found Mauritius (2.01) to have the highest access to all financial services and this is followed by Tunisia (1.32), Namibia (1.27) and South Africa (1.06) whereas the country with least financial resources access is Burkina Faso (−0.676; see, Figure ).

Table 3. Descriptive summary

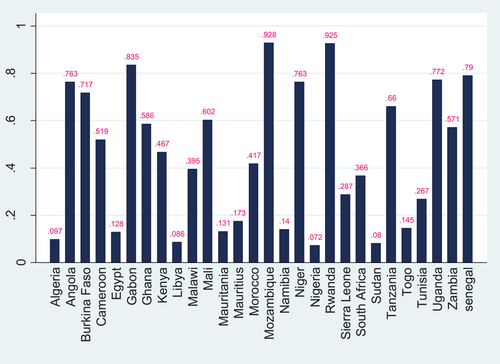

From Table it can also be seen that out of 100,000 adults, only 11. 98% on average use ATM to access financial services. In the same vein, the data indicates an average bank account and bank branches value of 288.9339 and 6. 2819. It can also be seen from Table that, in the African sample, domestic banks outperform foreign banks, on average. This is because the share of foreign banks (measured by the ratio of total assets of foreign banks to total assets of universal banks) is 0.4529, which means that the assets of foreign banks account for about 45% of the total bank assets in the sample. As shown in Figure , Mozambique (93%) and Rwanda (93%) have the highest share of foreign banks, as against Sudan (8%) who has the least inflow of foreign banks.

As mobile phone used to pay bills has a mean of 4.87%, mobile phone used to transfer money has 13.19% of the population. The data for Kenya (FT1 = 28% and FT2 = 49%) indeed shows that mobile money started in Kenya. In the case of Angola (0.0001 and 0.0002), mobile money usage is very minimal. The composite index of institutions has a mean of −0.5048, which suggests that Africa has weak institutions and governance since the mean value is in the range of low institutions and governance. This conforms with the study by Mensah et al. (Citation2018), who argue that SSA are characterized by poor institutions and weak governance. Also as shown in Table , the lending-deposit spread has an average value of 8.89 suggesting that the banks of the African sample have more spread (i.e., they charge high rates of interest while low rates are applied to deposits). This can discourage savings since savers are not motivated to save their surplus funds.

On average, most citizens of the African sample do not have access to secondary school education. This is because education, has a maximum of 357 whereas the minimum value is 1. However, the mean value is approximately 120 with a standard deviation of approximately 119. This also suggests that the enrolment level in Africa is inconsistent. The data shows that the population in Africa is growing since it has a maximum value of 5.605, the mean value is 2.42. The data for population growth could mean that, Africa is increasing therefore, there is the need for more financial infrastructure to meet the banking and financial need of the increasing population.

4.1. Quantile regression results of Fintech, foreign bank entry and inclusive finance

The results in Table reveal that using cell phone to make payment (FT1) was used as a proxy for Fintech, Fintech induces inclusive finance index (IFI) at all levels of inclusive finance (see column 1–4). However, when Fintech was measured with mobile phone used to transfer money (FT2), we saw that Fintech spike inclusive finance index at two levels (i.e., q.25 and q.50). This means that at the 75th and 90th quantile, mobile phones used to transfer money do not significantly impact inclusive finance. Our cross-country results showed that regardless of the measure of Fintech (either cell phone used to make the payment or cell phone used to transfer money), inclusive finance increases when a country engages in using digital applications to provide financial services. This positive effect corroborates with both cross-country studies and single-country studies that Fintech induces inclusive finance in Africa (see, Demir et al., Citation2022; Gosavi, Citation2018; Mbiti & Weil, Citation2015).

Table 4. Fintech and inclusive finance

Turning to the control variables, we found financial stability to have significant effect on the 75th quantile of the IFI as shown in Table . This shows that financial services and resources can be easily utilized when the banking system is stable. In other words, a stable banking sector can boost depositor confidence, while instability can lead to fear and panic and reduce access to finance. We found that a decrease in inclusive finance is associated with an increase in lending-deposit spread. This effect was realized at the 50th quantile of the IFI when FT1 was used as a proxy for Fintech and at 50th and 90th quantile of IFI when FT2 was used as a measure for Fintech (see Column 2, 6 and 8 of Table ). Also, the decrease in inclusive finance was high at the 90th quantile of IFI, when FT2 was used as a measure for Fintech. The negative significant effect of lending-deposit spread could be as a result of broadening spreadsFootnote4 which then reduces efficient financial allocation with respect to access to financial resources. Due to information asymmetry in the financial sector in most African countries, the financial institutions charge higher interest rates to cover such risks of repayment default (Anarfo et al., Citation2020). Such activity then prevents borrowers’ ability to access more financial resources, rates on deposit on the other hand, seems to be low in Africa, hence disincentivizing those with a cash surplus to deposit their excess funds with the financial institutions (Anarfo et al., Citation2020).

Surprisingly, we found education to hamper inclusive finance as shown in Table . This is evident when FT2 was used as proxy for Fintech and affected the 25th and 90th quantile of IFI. Although the more educated people are, the more likely they are to be financially included (see Zins & Weill, Citation2016; Allen et al., Citation2016; Fungáčová & Weill, Citation2015), we obtained the opposite results. This could be that regardless of the higher education, when some factors such as distance to financial institution and unemployment persist, highly educated persons may not be financially included. Hence our results disagree with Demir et al. (Citation2022) who conducted similar study in the same region and found that higher education helped people to get access to credit facility. As shown in Table the institutional quality index deepens inclusive finance at most levels of IFI. As a result, the quality of the African sample institutions encourages inclusive finance. The result is similar to that of Demir et al. (Citation2022), Dabla-Norris et al. (Citation2015), and Rojas-Suárez (Citation2016) who argue that quality institutions improve access to finance. Population growth exhibited a negative significant effect. We have observed that the column (8) of Table has the highest coefficient, indicating a greater increase in inclusive finance in the 90th quantile of IFI. In column (8), where Fintech was proxied with FT2, population reduces the 90th quantile of IFI. This implies that when population growth of Africa increases, it will prevent most of the citizens from getting access to financial services.

The study also examined the direct effect of FBP on inclusive finance by including FBP to model 1 and excluding Fintech in model 1 to see how FBP will influence inclusive finance. We present the results of FBP and IFI nexus in Table . FBP do not spike any levels of IFI (see, Table ). Also, some control variables exhibit different signs as compared to the unconditional effect of Fintech.

Table 5. Foreign bank present and financial inclusion

Since foreign banks in Africa engage in Fintech, we introduced FBP and the interactions (i.e., an interaction term of Fintech and FBP) to model 1 to see if foreign bank matters in the relationship between Fintech and inclusive finance. We show the results in Table . The results in Table show that FBP and the interaction term are very important. For instance, when we include these two variables, both FT1 and FT2 induce inclusive finance at all the levels of IFI.

Table 6. Moderation role of foreign bank presence on Fintech-inclusive finance index nexus

We also found FBP induces IFI but statistically insignificant. It was realized that the interaction term dampens inclusive finance at the 90th quantile of IFI as shown in column (16) and also in column (18) to (20) of Table , the interaction term hamper inclusive finance at the 50th, 75th and 90th quantile of inclusive finance index. However, to determine the net effect for the interaction term for column (16) of Table , we partially differentiate inclusive finance index with respect to Fintech as computed below based on Equationequation (5)(5)

(5) ;

Where represents the unconditional effect of Fintech on inclusive finance,

connotes the coefficient of the interaction of Fintech and foreign bank presence and

is the mean of FBP. A similar approach was used to compute the net effect for columns (14) to (16) as shown below;

The values of ,

and

are the coefficients of the net effects of column (18), (19) and (20) respectively. These results suggest that in the presence of foreign banks, Fintech can spike inclusive finance through the integration of Fintech into traditional banking. For example, when foreign banks link account numbers to mobile phones, the creation of banking applications, partnering with mobile services providers to extend credit facilities to the less privileged, will help increase the levels of inclusive finance.

4.2. Robustness checks

4.2.1. Robustness checks for inclusive finance index

The p-value of 0.000 in chi-square 1693.198 and the Bartlett test provide further evidence for a relationship between variables (see, Table ). As shown in Table , KMO of 0.840 indicates that our 6 variables are sufficient to compute the IFI.

Table 7. KMO and bartlett’s test

According to the Kaiser rule, an index created with PCA should at least have 1 component with its eigenvalues above 1. Therefore, we computed our index since the eigenvalue of 3.661 is greater than 1 and also the index generated is appropriate as the component used as the index has a proportion of 61.019% of the entire 100% component (see Table .

Table 8. Principal components and eigenvalues for inclusive finance index

4.2.2. Robustness checks using single indicators of inclusive finance

Next, we examined the impact of Fintech on the various indicators of inclusive finance. Our results show that both FT1 and FT2 influence bank account positively (see, Table A2) unlike in the case of ATM per 100, 000 adults whereas FT1 induces all levels, FT2 spike the 50th and 75th quantile (see, Table A1). With respect to bank branches, while FT1 spike the 75th and 90th quantile, FT2 induce only 50th (check Table A3). The results suggest that when people are able to use mobile phone to pay bills and transfer money, banks will have the opportunity to establish more branches. We realize that FT1 affected the 75th and 90th quantile of borrowers of commercial banks whereas FT2 deepens inclusive finance in all the quantile used for the study (see, Table A4). Different results were obtained from Table A5, when compared with Table . For example, Table A5 showed that FT2 hampers inclusive finance at 50th and 75th quantile of commercial bank branches whilst it enhances 90th quantile of commercial bank branches. Notwithstanding that, we found FT2 to have no significant effect on all the levels of depositors of commercial banks. This means that the increase in the amount of cell phones used to send cash does not encourage people to deposit money in commercial banks.

FBP do not spike any levels of inclusive finance index (see, Table ). Withal, this, FBP is able to influence the levels of the individual inclusive finance variables. For example, FBP has negative effects on the levels of the individual indicators of inclusive finance6 with the exception of the 90th quantile of commercial bank branches which had opposite results (see, Table A7 to Table A9).

We also estimate the moderation role of FBP on all the six indicators of inclusive finance. Different from Table where the inclusion of additional variables increased the significance level of Fintech, Table A9 showed that when the additional variables were included, most of the coefficients were not statistically significant (see, Table A9). Also, when ATM per 100,000 was used as inclusive finance variable, the interaction term was not significant suggesting that FBP has no impact on the relationship between Fintech and ATM per 100,000. This is evident as FBP dampens the levels of ATM per 100,000 as shown in shown in Table A9. However, in the case of the other indicators we noticed that FBP magnifies the nexus between Fintech and inclusive finance as presented in Table A10 to Table A15. The interaction term showed a negative effect on all the individual variables of inclusive finance with the exception of commercial bank branches.

5. Conclusion and implications

The study used 28 countries over a 19-year period, 2000–2018 and using quantile regression, we found that, Fintech affects inclusive finance. The study shows that mobile phones used to make payment tends to trigger Fintech than mobile phones used to send money. Furthermore, the results show that multidimensional inclusive finance provides higher significant results as compared to individual indicators of inclusive finance. We realized that foreign bank presence does not directly affect inclusive finance, but increases the net effect of Fintech on inclusive finance (i.e., when the inclusive finance index is used as a proxy for inclusive finance). Different results were obtained when the indicators of inclusive finance were used.

The study provides some policy implications for policy making. Firstly, because Fintech is a bank financing tool for non-bankers, African countries can expand, make better use of accessible financing, and create a favorable environment for Fintech operations. Secondly, the central banks of these countries should encourage most organizations in Africa to be innovative enough to engage in digital payment systems (by accepting e-cash) since mobile phone used to pay bills is a driving force of inclusive finance. This will help most people to appreciate the services of Fintech. Thirdly, the presence of foreign banks is crucial to using Fintech as an opportunity to enhance access to finance. Because these foreign banks use modern techniques, policymakers need to encourage their participation in the domestic financial sector, but good governance must be exercised through improved regulatory bodies.

A drawback to this study is that we do not consider all the countries in Africa due to data constraint. Additionally, we do not consider how the characteristics of each foreign bank can influence the level of inclusive finance or Fintech-inclusive finance nexus. Lastly, the paper did not investigate whether Fintech and foreign bank presence interactions matter for reducing poverty in Africa. Therefore, we leave these limitations for future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The study published its data in Mendeley Data Repository and can be found from Iddrisu, khadijah; Abor, Joshua; Banyen, Kannyiri (2022), “Fintech, Foreign Bank Presence and Inclusive Finance”, Mendeley Data, V1, doi: 10.17632/dshngs52gs.1

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Khadijah Iddrisu

Khadijah Iddris’ is a PhD candidate of Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies. She holds an MPhil in Finance from University of Professional Studies, Accra, a BSc. Accounting from the University of Development studies and also an Executive Mini MBA in corporate governance and financial management both from Accra Business School.This paper is part of Khadijah Iddrisu’s PhD Business Administration (Finance) research. The research reported in this paper is related to UN’s Agenda 2030 and World Bank project on both inclusive finance and Fintech.

Joshua Yindenaba Abor

Joshua Yindenaba Abor is a Professor of Finance, financial economist and qualified accountant. He is experienced in development finance and economics research. He holds a PhD in Finance from Stellenbosch University, a Fellow of Association of Certified Accountants, UK. He is a former Dean of the University of Ghana, Business School.

Kannyiri T. Banyen

Kannyiri T. Banyen is a senior lecturer in the Department of Finance at the Simon Diedong Dombo University of Business and Integrated Development Studies and a researcher at African growth institute, South Africa. He holds PhD in Business Administration specializing in Development Finance from the University of Cape Town and an MPhil in Finance from University of Ghana.

Notes

1. Anarfo et al. (Citation2020) identified that inclusive finance index gave more robust findings than that of single indicator in the context of Africa

2. Liberalisation of financial markets to follow liberalization of goods market

3. Algeria, Angola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Libya, Mali, Malawi, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Morocco, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Togo, Uganda and Zambia.

4. broadening spreads such as decrease in deposit rates as against average banking lending rates.

References

- Aba, F., & Linardy, D. (2021). Financial technology in financial inclusions and its implications on poverty from Indonesia. Preprints. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202111.0061.v

- Allen, F., Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., & Peria, M. S. M. (2016). The foundations of financial inclusion: Understanding ownership and use of formal accounts”. Journal Of Financial Intermediation, 27, 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2015.12.003

- Anarfo, E. B., Abor, J. Y., & Osei, K. A. (2020). Financial regulation and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does financial stability play a moderating role? Research in International Business and Finance, 51, 101070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.101070

- Andrianaivo, M., & Kpodar, K. (2012). Mobile phones, financial inclusion, and growth. Review of Economics and Institutions, 3(2), 30. doi: 10.5202/rei.v3i2.75

- Arestis, P., & Demetriades, P. (1997). Financial development and economic growth: Assessing the evidence. The Economic Journal, 107(442), 783–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.1997.tb00043.x

- Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., & Kinnan, C. (2015). The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation.: American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 22–53. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w18950/w18950.pdf

- Batunanggar, S. (2019). Fintech development and regulatory frameworks in Indonesia (ADBI Working Paper Series No. 1014). Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/222781

- Beck, T., & Brown, M. (2015). Foreign bank ownership and household credit. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 24(4), 466–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2013.10.002

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2007). Finance, inequality and the poor. Journal Of Economic Growth, 12(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-007-9010-6

- Beck, T., Fuchs, M., Singer, D., & Witte, M. (2014). Making cross-border banking work for Africa. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

- Beck, T., & Peria, M. S. M. (2010). Foreign bank participation and outreach: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2009.03.002

- Beck, T., Senbet, L., & Simbanegavi, W. (2015). Financial inclusion and innovation in Africa: An overview”. Journal of African Economies, 24(suppl_1), i3–i11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/eju031

- Buchinsky, M. (1995). Estimating the asymptotic covariance matrix for quantile regression models a Monte Carlo study. Journal of Econometrics, 68(2), 303–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01652-G

- Buchinsky, M. (1998). Recent advances in quantile regression models: A practical guideline for empirical research. Journal of Human Resources, 33(1), 88–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/146316

- Bucker, L . (2021). 5 loans without collateral in Ghana that you can access. Oze. https://www.oze.guru/oze-blog/5-loans-without-collateral-in-ghana-that-you-can-access

- Chakrabarty, K. C. (2012, November). Financial inclusion: Issues in measurement and analysis. In Irving fisher committee workshop on financial inclusion indicators (pp.2227-2270). Malaysia.

- Chikalipah, S. (2017). What determines financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa? African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 8(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-01-2016-0007

- Clarke, G. R., Cull, R., & Peria, M. S. M. (2006). Foreign bank participation and access to credit across firms in developing countries. Journal of Comparative Economics, 34(4), 774–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2006.08.001

- Collard, S., & Kempson, E.(2005).Affordable credit: The way forward. Policy Press.

- Dabla-Norris, M. E., Deng, Y., Ivanova, A., Karpowicz, M. I., Unsal, M. F., VanLeemput, E., & Wong, J. (2015). Financial inclusion: Zooming in on Latin America. International Monetary Fund.

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2018). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank Publications.

- Demir, A., Pesqué-Cela, V., Altunbas, Y., & Murinde, V. (2022). Fintech, financial inclusion and income inequality: A quantile regression approach”. The European Journal of Finance, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2020.1772335

- Detragiache, E., Tressel, T., & Gupta, P. (2008). Foreign banks in poor countries: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 63(5), 2123–2160. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2008.01392.x

- Didier, T., & Schmukler, S. L. (eds.). (2013). Emerging issues in financial development: Lessons from Latin America. World Bank Publications.

- Efron, B. (1981). Censored data and the bootstrap. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 76(374), 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1981.10477650

- Fouejieu,A., Sahay, R., Cihak,M, and Chen S. (2020). Financial inclusion and inequality: A cross-country analysis. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 291, 1018–1048. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2020.1785532

- Fu, J., & Mishra, M. (2022). Fintech in the time of COVID-19: Technological adoption during crises. Journal of Financial Intermediation,50,1–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2021.100945.

- Fungáčová, Z., & Weill, L. (2015). Understanding financial inclusion in China. China Economic Review, 34, 196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2014.12.004

- Ghosh, S. (2016). Does mobile telephony spur growth? Evidence from Indian states”. Telecommunications Policy, 40(10–11), 1020–1031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2016.05.009

- Gormley, T. A. (2010). The impact of foreign bank entry in emerging markets: Evidence from India. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19(1), 26–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2009.01.003

- Gosavi, A. (2018). Can mobile money help firms mitigate the problem of access to finance in Eastern sub-Saharan Africa? Journal of African Business, 19(3), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2017.1396791

- Honohan, P. (2004). Financial development, growth and poverty: how close are the links?. In Financial development and economic growth (pp. 1–37). Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230374270_1

- Jack, W., & Suri, T. (2011). Mobile money: The economics of M-PESA. No. w16721. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w16721

- Kebede, J., Selvanathan, S., & Naranpanawa, A. (2021). Foreign bank presence, institutional quality, and financial inclusion: Evidence from Africa. Economic Modelling, 102, 105572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2021.105572

- Koenker, R., & Hallock, K. F. (2001). Quantile regression. Journal Of Economic Perspectives, 15(4), 143–156.

- Kohtamäki, M., Parida, V., Oghazi, P., Gebauer, H., & Baines, T. (2019). Digital servitization business models in ecosystems: A theory of the firm. Journal of Business Research, 104, 380–392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.027

- Le Cook, B., & Manning, W. G. (2013). Thinking beyond the mean: A practical guide for using quantile regression methods for health services research. Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 25(1), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.1002-0829.2013.01.011

- Léon, F. (2016). Does the expansion of regional cross-border banks affect competition in Africa? Indirect evidence. Research in International Business and Finance, 37, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2015.10.015

- Léon, F., & Zins, A. (2020). Regional foreign banks and financial inclusion: Evidence from Africa. Economic Modelling, 84, 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.03.012

- Maurer, B. (2012). Mobile money: Communication, consumption and change in the payments space. Journal of Development Studies, 48(5), 589–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2011.621944

- Mbiti, I., & Weil, D. N. (2015). Mobile banking: The impact of M-Pesa in Kenya. In Edwards, S., Johnson, S., & Weil, D. N. (Eds.) African successes, volume III: Modernization and development. University of Chicago Press.

- McKinnon, R. I. (1973). Money and capital in economic development. Brookings Institution. McKinnonMoney and Capital in Economic Development1973

- Memon, A. A., Ghumro, N., Rajput, O., Kumar, S., & Memon, A. A. (2021). Role of foreign banks entry in promoting financial inclusion, Available at SSRN 3850307. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3850307. .

- Mensah, L., Bokpin, G., & Boachie-Yiadom, E. (2018). External debts, institutions and growth in SSA. Journal of African Business, 19(4), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2018.1452466

- Morawczynski, O. (2009). Exploring the usage and impact of “transformational” mobile financial services: The case of M-PESA in Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 3(3), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050903273768

- Nanivazo, J. M., Egbendewe, A. Y., Marcelin, I., & Sun, W. (2021). Foreign bank entry and poverty in Africa: Misaligned incentives?. Finance Research Letters, 43, 101963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.101963

- Navaretti, G. B., Calzolari, G., Mansilla-Fernandez, J. M., & Pozzolo, A. F. (2018). Fintech and banking .Europeye srl. http://european-economy.eu/

- Nawaz, S., Iqbal, N., & Khan, M. A. (2014). The impact of institutional quality on economic growth: Panel evidence. The Pakistan Development Review. 15–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24397923

- Ouma, S. A., Odongo, T. M., & Were, M. (2017). Mobile financial services and financial inclusion: Is it a boon for savings mobilization?. Review of Development Finance, 7(1), 29–35. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-83159723e

- Ozili, P. K. (2018). Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability”. Borsa Istanbul Review, 18(4), 329–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003

- Peruta, D.M. (2018). Adoption of mobile money and financial inclusion: a macroeconomic approach through cluster analysis. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 27(2), 154–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2017.1322234

- Rojas-Suárez, L. (2016). Financial inclusion in Latin America: Facts, obstacles and central banks’ policy issues.

- Rousset, M., Torres, J. L., Lambert, F., Herrera, L., Ramos, G., & Gershenson, D. (2021). Fintech and Financial Inclusion in Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Salampasis, D., & Mention, A. L. (2018). FinTech: Harnessing innovation for financial inclusion. In Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion, Volume 2 (pp. 451–461). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812282-2.00018-8

- Sengupta, R. (2007). Foreign entry and bank competition. Journal of Financial Economics, 84(2), 502–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.04.002

- Shah, P., & Dubhashi, M. (2015). Review paper on financial inclusion-the means of inclusive growth. Chanakya International Journal of Business Research, 1(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.15410/cijbr/2015/v1i1/61403

- Shaw, E. S. (1973). Financial deepening in economic development.

- Tchamyou, V. S., Erreygers, G., & Cassimon, D. (2019). Inequality, ICT and financial access in Africa. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 139, 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.11.004

- Villanueva, D., & Mirakhor, A. (1990). Strategies for financial reforms: interest rate policies, stabilization, and bank supervision in developing countries. Staff Papers, 37(3), 509–536. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867263

- Voghouei, H., Azali, M., & Jamali, M. A. (2011). A survey of the determinants of financial development. Asian‐Pacific Economic Literature, 25(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8411.2011.01304.x

- World Bank. (2018). Financial Inclusion overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview#1

- Zetzsche, D. A., Buckley, R. P., Barberis, J. N., & Arner, D. W. (2017). Regulating a revolution: From regulatory sandboxes to smart regulation. Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, 23, 31. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1450&context=jcfl

- Zingales, L., & Rajan, R. (2003). Banks and markets: The changing character of European finance. https://doi.org/10.3386/w9595

- Zins, A., & Weill, L. (2016). The determinants of financial inclusion in Africa. Review of Development Finance, 6(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2016.05.001

Appendices

Table A1. Fintech on ATM per 100, 000

Table A2. Fintech and bank account

Table A3. Fintech and bank branches

Table A4. Fintech on borrowers from commercial banks

Table A5. Fintech on commercial bank branches

Table A6. Fintech on depositors of commercial bank

Table A7. Foreign bank presence and inclusive finance (ATM per 100,000 adults and banks accounts)

Table A8. Foreign bank presence and inclusive finance (borrowers and depositors of commercial banks)

Table A9. Foreign bank presence and inclusive finance (bank branches and commercial banks branches)

Table A10. FBP on Fintech and ATM per 100, 000 nexus

Table A11. Moderation role of foreign bank presence on Fintech-bank account

Table A12. Moderation role of foreign bank presence on Fintech-bank branches

Table A13. FBP on Fintech-borrowers from commercial banks

Table A14. FBP on Fintech-commercial bank branches

Table A15. FBP on Fintech -depositors from commercial bank