Abstract

Credit activities are an essential commercial bank activity. Therefore, preventing and limiting credit risks is vital for their credit activities. The Covid-19 epidemic is still ongoing. In 2021, 30 banks listed bad debts of more than 113 trillion VND, a 26% increase relative to 2020. Vietnam has the dual goal of fighting the outbreak while continuing with socio-economic development. In this context, credit activities are still essential. Banks require the necessary and appropriate management solutions to adapt to the new situation to ensure safe and sustainable credit activities. This study analyzes some current problems and leading causes of the credit risk of commercial banks. The author has primary data from detailed questionnaires distributed directly to 300 credit risk managers based on a random process. This study examines the descriptive statistics, and compares, analyzes, and synthesizes the statistical reports of commercial banks. The study is novel in that it analyzes more than 60% of commercial banks affected by Covid-19 in terms of risks from subjectivity and risks due to objective causes. Therefore, the results suggest several policy recommendations for minimizing Vietnamese commercial banks’ credit risks after the Covid-19 pandemic.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Credit risk management is essential in ensuring the bank’s credit activities’ safety and contributes to minimizing banking activities’ risks. Therefore, the prevention and limitation of credit risks are vital for the credit activities of commercial banks. Besides, credit is the lifeblood of the economic development of a country and is one of the critical conditions promoting the economic development of any country. Moreover, the Covid-19 epidemic has seriously affected the world, leading to a decline in the socio-economic situation. In the context of both anti-epidemic and production, while ensuring safety, the difficulties of enterprises will undoubtedly lead to banks’ problems. Vietnam has been implementing the dual goal of fighting the outbreak while striving to fulfill socio-economic development goals. In this context, credit activities are still essential. Banks need to have necessary and appropriate management solutions to adapt to the new situation for safe and sustainable credit activities.

1. Introduction

For the years 2020 and 2021, Vietnam’s economy has been negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, the State Bank of Vietnam has actively and flexibly managed monetary policy, solving difficulties for businesses, meeting the economy’s needs for credit capital effectively, and drastically handling bad debts. However, the new reality requires more solutions to meet credit capital needs for sustainable economic growth. Credit activities are a basic banking activity, providing the primary source of revenue for commercial banks (Antunes et al., Citation2021). However, commercial banks are facing credit risk. Credit risk causes financial loss, reduces the market value of the bank’s capital, and in more severe cases, makes the bank’s business operations unprofitable or even lead to bankruptcy. The impact of the Covid-19 epidemic is increasing bad debts at banks, which are difficult to collect and handle. Notably, in 2021, debt collection was 90.1 trillion VND, only reaching 50% compared to the end of 2020. In the last 2 years, the Covid-19 epidemic seriously affected the world, leading to a decline in the socio-economic situation. In the context of anti-epidemic measures and the need for safe production, the difficulties of private enterprises undoubtedly creates problems for banks, causing a rapid increase in bad debts.

When the principal and interest are due, it causes financial losses and difficulties in the business operations of commercial banks. Moreover, credit risk arises from the borrower’s failure to comply with credit contract terms, which manifest as late, incomplete, or non-payment of debt (Antunes et al., Citation2021). The causes of risk can be environmental; like the activities of other economic actors, the credit activities of commercial banks are influenced by many factors in the economic, political, and regulatory environment, as well as cultural characteristics and the overall regional and local impact. Credit is still the most critical activity of commercial banks because it accounts for a large proportion of their revenue and profit; therefore, the impact of this risk can have burdensome negative consequences.

From the bank’s side, risk can arise from its risk appetite; that is its attitude towards risk-taking to a specific limit. Within that limit, the bank is able and willing to withstand and overcome risks. Along with the weakness of the bank’s staff, there is an exceedingly high risk of credit risk. This factor is one of the subjective causes of credit risk. In addition, excessive credit expansion means poor selection of customers, reduced supervision of credit officers, and decreased compliance by strictly following loose credit pricing (Channar et al., Citation2015; Cheng et al., Citation2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic severely affected most economic organizations and individuals using banking credit services. Therefore, the State Bank of Vietnam and commercial banks have had to implement several policies to support all economic sectors, such as allowing credit institutions (CIs) to restructure loan repayment terms, exempting CIs, and exempting them from debt. Reducing loan interest and easing loan difficulties for customers or commercial banks reduced lending interest rates by 0.5 to 1.5% annually for borrowers. Commercial banks committed more than 70,000 billion VND to support businesses and individuals affected by Covid-19. As of 5 April 2021, CIs restructured the payment term debt for about 262,000 affected customers with an outstanding balance of nearly 357,000 billion VND.

On the customer side, risk arises from the many loans taken to invest in investment portfolios sensitive to market fluctuations or deliberate fraud by customers. Additionally, some companies guarantee or authorize their branches to borrow money from commercial banks to avoid supervision by leading lending banks (Ferreira, Citation2021). When the loan unit is insolvent, the guarantor and proxy refuse to pay the debt on its behalf. Measures to prevent and limit credit risks should be researched and devised in accordance with the business characteristics of each bank. Thus, the author offers several policy recommendations for minimizing Vietnamese commercial banks’ credit risks in the Covid-19 pandemic.

2. Literature review

2.1. Credit

Credit is the transfer of capital based on credit. Credit appeared with the appearance of money and commodity exchange to meet society’s capital regulation needs. Capital is the object of transfer in a credit relationship, which can be cash or assets with cash value. After using the capital as agreed upon in a credit relationship, the recipient of the capital must return it to the person who transferred it to him (Khalid & Amjad, Citation2012). Before discussing this concept, let us first understand the concept of credit. Credit is the relationship between a borrower and a lender. The lender must transfer the right to use the loan money or goods to the borrower within a specific time (Abu Hussain & Al-Ajmi, Citation2012; Laar & Adjei, Citation2020). The borrower must pay the borrowed amount or goods in full when due, with or without interest.

In legal terms, a credit relationship is a property loan relationship. It differs from normal property loan relationships in that the object of repayment is not an object of the same type, but money. In economic-commercial relations, the repayment obligation is to return a value more significant than the amount transferred, including the assigned value and credit interest (Alshatti, Citation2015; Shafique et al., Citation2013). Credit interest is calculated according to the interest rate, which is the price of credit. Bank credit is a credit relationship between banks, CIs, and businesses or individuals (borrowers). The bank or CI will transfer the property to the borrower for use within a certain period (Atlman, Citation2001; Williams et al., Citation2006). The borrower must repay both the principal and interest to the CI when due.

2.2. Risk

Risk is an objective and unforeseen cause in the four aspects shown in the figure above. A risk is an unforeseeable event in terms of probability, time, place of occurrence, and severity and consequences (Gaganis et al., Citation2021; Richard et al., Citation2008). Vietnam often has storms in the summer in the North and Central regions, but it is impossible to predict precisely where and when the storm will occur, its intensity, and the damage it will cause. Hence, storms are a risk (I-Tamimi & Al-Mazrooei, Citation2007; Peter & Peter, Citation2011). A risk damages one property but not another, such as in the cases of hail, showers, waterlogging, and drought, which affect different crops differently. Thus, what people intentionally cause to themselves and what is predictable in space and time is not a risk (Fatemi & Fooladi, Citation2006; Henseler et al., Citation2016).

In the banking, credit is the main profit-making business of the bank, though it is potentially hazardous. Risks are unexpected events that lead to a loss of the bank’s assets, a decrease in actual profit relative to expectations, or an additional cost to complete a business with specific financial services (Boahene et al., Citation2012; Fan & Shaffer, Citation2004). Credit risk in general and risk in lending activities is one of the leading causes of losses and seriously affects the quality of the bank.

Credit risk is the potential change in net income and capital market value resulting from the customer’s non-payment or late payment. Credit risk means that costs are delayed or not paid in full. This risk is the risk that the borrower will not be able to pay interest or repay the principal within the time limit specified in the credit agreement (Barnhill et al., Citation2002; Hahm, Citation2004). This factor is an inherent attribute of banking operations. When the bank holds a profitable asset, the risk occurs when the customer does not pay the principal and interest as agreed. This causes problems with cash flows and affects the bank’s liquidity.

2.3. Credit risk

Credit risk in banking operations translates into potential loss on a loan for a CI or foreign bank branch due to the customer’s failure or inability to perform part or all its obligations. Credit risk is the possibility that the borrower or counterparty will not meet the payment obligation according to the agreed terms (Hu & Zhang, Citation2021; Masood et al., Citation2012). Thus, credit risk arises when one of the parties in a credit contract cannot pay the remaining parties. Such credit risk is an inevitable part of a bank’s business (Gizaw et al., Citation2015; Kaaya & Pastory, Citation2013).

Credit risk is the risk that the borrower will not be able to pay interest or repay the principal in the period specified in the credit contract. This risk is an inherent attribute of banking operations. Credit risk means delayed or only partial payment. This causes problems with cash flows and affects the bank’s liquidity (Carey, Citation2001; Hassan, Citation2009; Tchankova, Citation2002).

Thus, from these previous studies, the author summarizes the idea of credit risk as follows: Credit risk of commercial banks is a type of risk that causes bank loss. Commercial transactions occur when customers fail to perform or fulfill their debt payment obligations according to their commitments to the bank (Anwen & Bari, Citation2015; Bono, Citation2020).

2.4. Impact of credit risk on bank operations

When credit risk occurs, bad debts will arise, and capital stagnation leads to decreased bank capital turnover, and higher administrative costs, debt collection supervision, and so on. These costs are higher than the income from the increase in interest rates on overdue debt because these are just virtual incomes and a measure the bank implements. It is not straightforward for the bank to recover them fully (Colesnic et al., Citation2020; Henseler et al., Citation2015). In addition, the bank still must pay interest on the money mobilized, while some of the bank’s assets neither earn interest nor convert into cash for others to borrow and earn interest. The result is decreased bank profits (Kozarevic et al., Citation2013; Lotto, Citation2018).

Banks often plan to balance cash outflows by paying interest and principal on deposits, loans, new investments, and cash inflows (deposits, collection of principal and interest, etc.). The two cash flows affected are loan contracts that are not paid in full and on time (Nazir et al., Citation2012; Vatsa, Citation2004). Customers’ savings deposits must still be paid on time, while their loans are not repaid on time. If the bank does not borrow or sell its assets, then its solvency will be weakened, leading to payment risk.

If insolvency occurs many times, or the information about the bank’s credit risk is disclosed to the public, impairing its reputation. The managers will reduce the importance and standing of the bank in the financial market. This is an excellent opportunity for investors. Competitors vie for markets and customers (Rosman, Citation2009; Shafiq & Nasr, Citation2010).

If many bank customers have difficulty repaying substantial loans, it can lead to a crisis in banks’ operations. When the bank does not prepare contingency plans and are unable to meet a high demand for withdrawals, it will quickly lose its solvency, leading to its collapse and bankruptcy (Rehman et al., Citation2019; Salas & Saurina, Citation2002).

3. Research methods

This study aims to answer the above questions, using a combination of the following methods.

The main scientific methodology is dialectical materialism and historical materialism This method combines the premise with other methods to show a logical debate in theoretical and practical research, which is applied for banks. The study also used statistical methods by collecting primary and secondary data related to credit risk management at commercial banks over time from internal reports and reports of State management agencies. Additionally, other data were collected via direct observations at the exchange and some branches for the research (Hair et al., Citation2021).

The author interviewed and consulted with experts, credit officers, and managers at some branches of commercial banks directly via email to get more information to serve the research process and complete the research. A survey questionnaire on credit risk management capacity at branches of commercial banks was distributed to get more information for assessing credit risk control at banks (Hair et al., Citation2021). The author selected branches for the survey to ensure representativeness. In big cities, branches in rural areas in Vietnam have high bad debt ratios and low lousy debt ratios.

The primary data were collected through a focus group discussion with 15 experts, specifically credit risk managers of 30 commercial banks in Vietnam. The author processed the data resulting from the survey and expert interviews using Microsoft Excel and SPSS software, and analyzed the reliability of each component and the measurement and verification criteria. The author also applied descriptive statistics to compare, analyze, synthesize the statistical reports of commercial banks to assess the current situation of risks. In addition, the author analyzed credit and credit risk management at commercial banks from 2020 to 2021.

The author adjusted and completed the official questionnaire for distribution directly to bank leaders to collect preliminary data. The sample was selected using the simple random method. The survey was sent to 300 credit managers of 30 commercial banks in Vietnam. The author must use the questionnaires to distribute and fill out the survey. The aim was to collect 275 valid responses from 300 credit managers of 30 commercial banks in Vietnam as the correct rate is 91.67 % (Hair et al., Citation2021). Based on the identified problems and applying theoretical and practical insights, the author proposes solutions to address the shortcomings, weaknesses, and relevant factors in credit risk management at commercial banks, the author makes logical deductions to propose solutions and recommendations to strengthen credit risk management at commercial banks. The questionnaire items were assessed using the following 5-point Likert scale: (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Neutral, (4) Agree, (5) Strongly agree (Hair et al., Citation2021).

The author used the basic theoretical knowledge of credit risk management and credit risk management capacity in line with international practices and current regulations in Vietnam to analyze and evaluate the current credit risk management capacity in commercial banks systematically. The author analyzed banks’ current credit risk situation with qualitative and quantitative methods. With a rich, up-to-date, transparent data source, the study illustrates the limitations and causes of the regulations in a realistic manner. This method of assessing the situation has more advantages than similar published studies, from which the author’s proposal implies a policy of minimizing credit risk (Facchinetti et al., Citation2020). From those studies, the author gives reliable, practical research results.

The independent variables include X1: Improve governance capacity in line with international practices and Basel II standards; X2: Improve credit risk handling capacity; X3: Improve the quality of human resources; X4: Strengthen the capacity to build and apply management information systems and informatics infrastructure; and X5: Complete the credit risk early warning system (Bussmann et al., Citation2020; Facchinetti et al., Citation2020; Giudici et al., Citation2020).

The dependent variable is Y: Commercial banks’ credit risks based on the increasing bad debt.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the banking industry

The research results show that the decline in the business performance of banks in the context of the COVID-19 epidemic is due to the negative impact of credit size and the decreased credit efficiency during the pandemic. The Covid-19 period has a below-average beta relative to the full period. The implementation of social distancing to prevent and control the Covid-19 epidemic partly influenced enterprises’ production and business processes and reduced banks’ business performance. From 2020 to now, the world economy, including Vietnam, has been seriously affected by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Through data collected from commercial banks listed in Vietnam’s stock exchange and extracted from their own reporting, this study analyzes the impact of the Covid-19 epidemic on the business performance of commercial banks. The results showed a decline in the business performance of banks in the context of the Covid-19 epidemic. Further, credit size during the pandemic was smaller than the average for the entire operating period.

In general, the covid-19 pandemic affected the financial ability of both individual and corporate customers. This result is shown through macro indicators. Given the timely and effective government support, the banking industry has not faced significant disadvantages compared to the rest of the economy. However, there are potential concerns that the effects have been deferred and will play out in the future.

Facing the general difficulties of the economy in 2020, the State Bank lowered the operating interest rate three times and issued Circular No. 01/2020/TT-NHNN, dated 13 March 2020. Besides regulating CIs, foreign bank branches restructured debt repayment terms, exempted or reduced interest and fees, and maintained debt groups to support customers affected by the Covid-19 epidemic as a legal basis for CIs. Accordingly, commercial banks agreed to lower lending rates from 1.5% to 2% per year to maintain customers affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. Consequently, lending interest rates decreased by 1% per annum compared to the end of 2019. The maximum short-term lending interest rate in VND for some priority sectors and fields is 4.5% per annum. As of December 2020, CIs restructured repayment terms for about 270 thousand customers with outstanding loans of nearly 355 trillion VND. Banks also reduced and lowered interest rates for about 590 thousand customers with outstanding loans of over 1 million billion VND. New loans with preferential interest rates with accumulated sales from 23 January 2020, to the end of December 2020 reached nearly 2.3 million billion VND for more than 390 thousand customers. It is estimated that the total payment service fees that banks waived or reduced for customers until the end of 2020 after 02 fee reductions are about 1.004 billion VND.

4.2. The state of credit risk in the banking system in 2019-2020

Commercial banks are also facing many difficulties and challenges. Due to the epidemic, many businesses could not pay their debts, leading to an increase in the bad debt ratio, which affects the operational safety of the commercial banking system. Therefore, credit demand and the Covid-19 epidemic significantly affected credit quality. By the end of the third quarter of 2020, bad debt at 17 listed banks was more than VND 97,280 billion, which increased by 31% compared to the end of 2019. The bad debt ratio on the balance sheet of the commercial banking system also increased to 2.14% from 1.8% at the end of the second quarter.

Implementing Circular No. 01/2020/TT-NHNN, banks actively implemented debt restructuring, keeping the debt group unchanged to support businesses. Therefore, the bad debt ratio tended to decrease in the fourth quarter of 2020, though bad bank debts still have many potential risks.

According to the Credit Department, by 2020, commercial banks restructured repayment terms for about 200,000 customers with outstanding loans of about 355 trillion VND of the total outstanding loans of VND 8.5 million billion. The potential lousy debt of all structured debt is 4%. If 50% of the restructured debt returns to good debt status, but the bad debt ratio is also about 2%, plus the current lousy debt ratio is more than 2%, then the bad debt is up to 4%. This will create great challenges for banks in 2021. Thus, the current bad debt of banks does not fully reflect reality because many debts have rescheduled payment according to Circular No. 01/2020/TT-NHNN, but in essence, it is bad debt.

On 27 July 2020, the steering committee to restructure the banking system. Many businesses have overdue debts that are not eligible for repayment period restructuring according to Circular No. 01/2020/TT-NHNN; however, they are continuously petitioning and creating pressure for commercial banks. The bank had a meeting to evaluate the results of the implementation of Resolution No. 42/2017/QH14, dated 21 June 2017, of the National Assembly on piloting inadequate debt settlement of CIs and Decision No. 1058/QD-TTG, dated 19/7/2017, of the Prime Minister’s approval of a project on restructuring the system of CIs associated with bad debt settlement for the period 2016–2020. The banking system handled 557,000 billion VND of bad debts, of which CIs alone account for over 76%. This result helped to reduce the on-balance sheet terrible debt ratio to 1.63%. The percentage of on-balance sheet terrible debt, including debt sold to VAMC and contingent obligation, stood at about 4.43%, a sharp decrease compared to the previous level of 10.08%.

Additionally, excess capital is the reality for many banks in 2020, when the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic spurred strong capital inflows to banks as a safe investment channel, while the demand for loans severely weakened. Usage improved significantly from the beginning of October 2020 to the end of the year. As of 24 November 2020, capital mobilization increased by 10.65% compared to the beginning of 2020, credit increased by 7.93%, and total means of payment increased by 10.31%. Thus, the gap between capital mobilization and credit growth continued to widen despite the credit growth rate, from 2.58% in September 2020 to 2.72% in November 2020.

Compared to industries directly affected by the Covid-19 epidemic, the banking industry was initially assessed to have suffered minor damage. However, the deterioration of this industry is not minor, as interest income still make up about 70% of the total income of commercial banks. If credit growth is not promoted, then banks will fall into the dual difficulty of lacking their primary source of revenue to make up for the shortfalls due to debt freezing, rescheduling, and provisioning for old and new debts. Meanwhile, loosening lending conditions is very risky. Therefore, the synchronous implementation of solutions with flexible and effective operating policies to minimize the impact of the Covid-19 epidemic on the banking industry is meaningful in the current period.

4.3. Credit risk in the banking system during the Covid-19 pandemic

There are many ways to define and conceptualize credit risk. Credit is still the most critical activity of commercial banks because it provides a large proportion of revenue and profit to most commercial banks. Therefore, the impact of this risk will create long-term, burdensome negative consequences. Still, generally, credit risk is understood as the risk that occurs when the obligor in a credit relationship is unwilling or unable to repay in full to the other party as agreed.

In the 17 principles of credit risk management in the Basel II accord issued by the Basel Committee (issued in September 2000), credit risk is the possibility that the borrower or counterparty will not meet its payment obligations under the agreed terms.

Circular No. 13/2018/TT-NHNN dated 18 May 2018, of the State Bank of Vietnam regulating the internal control system of commercial banks defines risk as the possibility of loss (loss of financial assets or non-financial losses) that reduces income and equity, leading to a decrease in the capital adequacy ratio or limiting the ability of commercial banks or foreign bank branches to achieve business goals.

There are many ways to classify credit risk, though this study addresses two. For risks with objective causes, the assessments seemed to be subjective because commercial banks all have risk assumptions, according to which they have corresponding response measures. Often, banks control such risks well because shocks are rare.

Consider the following two perspectives on identification. Objective-subjective identification is the cause of force majeure risks occurring beyond the will and control of people at a specific time. In a healthy growing economy, society’s production and consumption potential is still significant. Production and business activities still have many good conditions for development and vice versa. On the other hand, when the economy has soaring inflation, the domestic currency will depreciate, leading to domestic production and business difficulties and complicating the ability to recover credit capital.

The legal environment is a critical factor affecting the possibility of credit risk and the direct cause of threats in the production and business of bank’s businesses, causing overdue debts. Among the reasons for risk, objective causes are the most difficult to avoid. However, reducing losses is possible if the trend is correctly predicted, and banks can enforce a reasonable risk dispersion policy. Further, with this subjective identification, one often believes that losses due to objective causes usually account for a small proportion.

Regarding risk identification during the Covid-19 pandemic, this event fundamentally changed many forecasts, even classical predictions and theories. The Covid-19 epidemic changed many people’s behaviors, habits, and practices, including those of commercial banks. The Covid-19 pandemic occurred almost beyond all expectations of banks in the design phase of the identification—measurement—reduction—monitoring/handling process. The business operations had to change, requiring banks to adjust the management strategy and identify and manage credit risk. The impact of risk with objective causes will be extraordinarily complex and large, changing the credit process design. Therefore, commercial banks must approach risk identification according to different criteria.

In terms of the material risks from subjectivity, credit risk with commercial banks has two sides. First, from the borrower’s side, in the context of Covid-19, in addition to the factors that affect the risk in the lending process, the subjective risk brought by the pandemic is profound. Due to the customer’s limited qualifications, capacity, and management experience, market fluctuations and the pandemic itself would disrupt the enterprise plans. For example, the pandemic affected the supply of raw materials and buyer behavior led to changes in sales plans.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, all banks were almost beyond their forecasts. Thus, customers are naturally late in their plans, leading to losses that thereby lead to delays or defaults on loans. Additionally, borrowers’ financial capacities became weak and unhealthy. Financial capacity is a key indicator reflecting the customer’s status that banks use to determine their capacity to repay banks and partners, as well as fulfill payment needs during operations.

The borrower’s following creates the worst case of personal causes of credit risk. Customers’ repayment plans are affected when (i) they have to pay temporary expenses that are too large, thereby reducing their overall solvency; (ii) their forecasted cash flow in their own financial model is wrong; (iii) they experience a shock; or (iv) they face external circumstances. In the case of Covid-19, all plans changed, decreasing financial capacity. In this case, the Covid-19 factor is not affected). This factor is the cause of the moral hazard of borrowers and borrowers for banks.

Borrowers often make detailed plans to deal with the bank as soon as the loan is received, and in this case, the borrower takes the initiative to plan the next course of the loan process. Banks often face difficulties due to this risk. It becomes more complicated to collect debts, even if banks must take the last vital measure to sue customers in court to collect debts. The lender may have objective or subjective motivations, including a system of inspection and control processes, people, credit policy, and risk management. The bank’s risks include information based on the appraisal, as the bank does not have enough standard, correct, and appropriate (financial and non-financial) information to fully evaluate the borrower. Thus, the bank’s loan judgments will not be standard, skewing the loan amount, loan term, repayment terms, and so on.

In the context of the Covid-19 epidemic, the accuracy of information changed, creating additional unpredictability. The loan supervision loophole is the failure to inspect and supervise quickly enough or to improperly perform all stages of the lending process. This would include techniques to check the purpose of capital use through the documents proving this process, determining whether the progress of the production plan/project is delayed compared to the plan, and learning if the product quality of the plan/project is unsatisfactory, or if the suppliers or contractors are not able to meet their requirements, or the technology of the project/option is faulty/unsecured, making the project/lending plan’s efficiency unsatisfactory. These factors can mean that customers are unable to repay their loans.

Many lenders believe only in collateral, guarantees, and insurance, considering it these the best channels for debt collection, which can lead wrong decisions. The loan design must be appropriate to ensure that the loan is paid in full, regardless of conditions and circumstances. In the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, the stage of initiation and design of an appropriate (prognostic) loan for customers is critical and necessary to ensure that all stages of the lending process are followed, as in Figure .

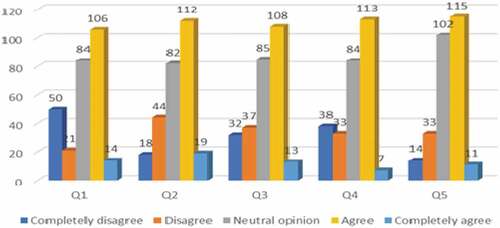

Figure 2 shows that the improved governance capacity in line with international practices and Basel II standards (Q1) agrees with 38.5 % of the responses. The expert interviews reveal that although commercial banks are issued and reviewed every year, they are still unable to meet Basel standards. Therefore, banks need to improve their governance capacity. Further, the improved credit risk handling capacity (Q2) agrees with 40.7 % of the responses. Credit risk management strategies, policies, and processes that correspond to other risks should be place and must be developed in a methodical, precise, and unified manner throughout the banking system. Improving the quality of human resources (Q3) is agreed upon by 39.3% of the responses. Strengthening the capacity to build and apply management information systems and informatics infrastructure (Q4) is approved by 41.1 % of the responses, and completing the credit risk early warning system (Q5) meets with 41.8 % agreement. Thus, commercial banks need to review and make appropriate adjustments to credit activities and credit risk management policies, such as those related to the credit process, risk management, and management. Banks require credit portfolio management, a risk classification policy, and a risk provisioning policy to ensure reasonableness, avoid duplication, and ensure consistency with the bank’s overall development strategy.

After qualitative research, the author launched a preliminary questionnaire and conducted a pilot survey to determine the difficulties for potential respondents. The instrument was amended based on the responses. After designing a complete survey and selecting a sample to conduct the study, the author formally interviewed credit officers to get information to fill in the questionnaire.

Table summarizes the results. The author sent a consultation form to credit managers and credit officers via email, face-to-face meetings, and posts to 300 credit managers, from deputy heads of departments and specialists of 30 commercial banks in Vietnam. The sample includes head offices of commercial banks, directors and deputy directors, heads and deputy heads of transaction offices, and officers of credit departments of commercial bank branches. The author obtained 275 valid responses. The results of the responses are aggregated with objective evidence, supplementing the author’s evaluations. The table provides the means and standard deviations in terms of the policy recommendations for minimizing Vietnamese commercial banks’ credit risks during the Covid-19 pandemic based on the factors affecting the credit risks of commercial banks.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (sample size = 275)

Table shows five factors affecting commercial banks’ credit risks based on the increasing bad debt with a significance level of 0.01. Table presents the analysis to evaluate the fit of the multivariate regression model. The adjusted R-squared is 0.591. That is, a 59.1 % variation of the dependent variable of credit risks is explained by five independent factors. This result shows that this linear regression model fits the sample’s data set at 59.1%. That is, the independent variables explain 59.1% of the variation of the dependent variable of credit risks. Table also shows the results of the tests of the model’s overall fit. The F-value is 80.190, significant at 000 < 1.0 %, indicating that the R-squared of the population is different from 0.0. Hence, the proposed linear regression model is suitable for the population. While it is not possible to calculate the R-squared population specifically, it will definitely be non-zero, where non-zero means that the independent variables impact the dependent variable.

Table 2. Factors affecting credit risks of commercial banks

Table shows that all five independent variables have a statistically significant impact on the dependent variable. That is, the five hypotheses are accepted. The results are tested for multicollinearity between the independent variables using the variance inflation factor (VIF), where VIF > 10 would indicate multicollinearity. In fact, VIF is often compared with 2. For this study, the VIF values are all less than 2, showing that there is no multicollinearity. Note that the relationship between Tolerance and VIF is inverse; VIF = 1/Tolerance, so only one of these two values needs to be evaluated.

Loan officer ethics are not part of the credit granting process, from loan initiation to the final stage of loan collection. At any stage, a favorable condition for the customer (more strongly than help) can cause credit risk with the loan. Commercial banks, according to their strengths or strategy, created loan products to meet the borrowing needs of customers in the context of the epidemic. An unsuitable loan product design will affect the borrower because the borrower is the beneficiary of the product. The bank’s role is to consult the borrower on each loan solution, in terms of the short-, medium-, and long-term consequences. This factor may cause the customer’s business plan to fail. Based on regression results and descriptive statistics, the author offers conclusions & policy recommendations below.

5. Conclusions and policy recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This study examined commercial banks’ credit risk management in the two years of 2019 and 2020. Credit risk is an objective fact, but CIs significantly impact the socio-economic environment. Based on the theoretical framework of credit risk, this study conducted a survey on credit risk management capacity and the current credit risk management capacity status in commercial banks in Vietnam. The author tested five factors affecting commercial banks’ credit risks based on the increasing bad debt with a significance level of 0.01. Based on regression results and descriptive statistics, the author proposed policies to improve credit risk management capacity at commercial banks. These implications are offered based on the theoretical framework, the actual data in consultation with the survey respondents, interviews with experts and with reference to the documents of the survey. The implications provide a scientific and practical basis for commercial banks to research and consider the credit risk management orientation and business strategy of commercial banks’ future trade.

5.2. Policy recommendations

In line with the trend of integration, the economy’s health is reflected through the circulation of finance, specifically through CIs. Preventing and limiting risks in lending by CIs is a complicated issue. Economic difficulties and weak corporate governance can bring unpredictable dangers to the process of CIs. Therefore, this article presents the following policy recommendations based on the results above.

First, improve governance capacity in line with international practices and Basel II standards (3.0473). Commercial banks’ management capacity includes developing appropriate credit strategies/policies and revising the organizational structure and credit risk management apparatus. Banks must improve governance capacity in line with international practices and Basel II standards. The following solutions should be implemented: (1) Risk management before loan disbursement. In this context, at the time of loan consideration, the bank needs to design a loan in consultation with the customer and accounting for the process of customer downsizing, the production and business process, and the sale and collection of money from the customer. During this initialization stage, it is necessary to pay attention to the percentage fluctuations (%) that may be affected by the Covid-19 epidemic to establish a credit contract. (2) To ensure compliance with Basel II standards, for example the risk management of commercial banks must be developed following business strategies. Business decisions must balance between capital, profit, loss profits, and risks while adhering to international practices, and simultaneously must be developed in line with each industry, field, and customer. On the other hand, risk management is based on stakeholders’ expectations (shareholders, Board of Directors, Management Board, customers, employees, and State management agencies) to protect the stakeholders’ interests. (3) Improve the risk management culture in the bank. Risk management culture comprises values, strategies, goals, beliefs, and attitudes towards risk, shaping each bank’s views on the trade-off between risk and return. Risk management culture recently received significant attention from bank administrators. To make changes across the bank and impact all levels, from staff to management, commercial banks must build a strong risk culture that can create great intrinsic value to enhance and improve risk management capacity in general and credit risk management capacity in particular. Finally, the government should have flexibly administered credit solutions to control the scale of and moderate credit growth, targeting production and business fields and priority areas according to the government’s policy. The government should also strictly control credit for potential risk areas, orienting credit structure in line with economic transformation to contribute to sustainable economic growth and development.

Second, improve credit risk handling capacity (3.2545). Banks’s credit products are designed based on customer loan efficiency, production, and business efficiency. In the context of many fluctuations, periodic production, and the Covid-19 epidemic, many flexible credit products are needed. These should include (1) term (short-, medium-, and long-term). Banks should have product categories for different credit-granting processes. (2) Banks should continue depending on customer size, providing credit product packages. Banks need to analyze seasonal supply/demand carefully. Each season will have different credit needs for capital according to the customer characteristics, such as management capacity, which will allow the bank to provide suitable products. Customers of the same business, size, or requirements may have different capacities, therefore, it is necessary to design products according to the management capacity of customers. (3) Following the Covid-19 disease control policy of the Government and the State Bank, banks must also issue flexible credit products that can convert terms to loan terms, terms to debt collection, and the amount of debt payment according to the cash flow corresponding to the evolution of the business during the epidemic. Credit is an activity that must accept a certain level of risk. In the current epidemic, banks sometimes have to deviate in terms of weight number, industry, or industry that fluctuates in response to Covid-19. (4) Improve appraisal quality. To control borrowers in this situation, banks need to improve the appraisal stage significantly; it should not stop at the loan appraisal and approval stage, but also include the credit granting process. According to the epidemic situation, there should be re-appraisals to ensure appropriate responses. At the same time, the bank needs to upgrade the appraisal stage into an appraisal consulting service (to achieve two goals: secure loans and help customers perform well in their business). Finally, the government should continue to evaluate credit activities in terms of industries, fields, roles, resilience, and the sustainable development of sectors and areas in the economy so mas to direct CIs to have priority policies, support, and focus on credit to contribute to economic recovery and growth. Banks should coordinate with ministries and branches to remove obstacles to implementing credit programs and policies under the direction of the Government and the Prime Minister.

Third, improve the quality of human resources (3.1200). Vietnamese commercial banks need to build a team of officers and specialists with high banking expertise who can approach econometric models according to international practices. Human resources in credit risk management activities range from the Boards of Directors and senior management of the banks to those who directly perform credit risk management. The risk management apparatus must be organized to separate risk creators from those who approve and monitor that risk. The Board of Directors is responsible for understanding the bank’s risks and ensuring that these risks are appropriately managed. Members of the Board of Directors must have experience in banking and credit business, management knowledge, economic knowledge, and knowledge of international practices in credit risk management. This update can be through seminars, forums, and financial seminars developed by the State Bank in collaboration with foreign experts. Commercial banks must work towards advanced human resource risk management, building a competency framework for each staff position with clear and specific recruitment and capacity assessment criteria. Banks must develop a set of evaluation objectives for each officer from management to non-management level staff with qualitative standards that can be weighted for quantification. This could include a goal-setting chart for a non-managerial team. The content of the evaluation criteria should include objectives to assess compliance with credit business processes. Besides credit risk management processes such as professional qualifications, professionalism, and measurement tools, the degree of compliance with credit risk management policies and procedures should be written. Banks should effectively use human resources, meet business requirements, fully exploit their capabilities and potential, promote the corporate culture, and encourage long-term attachment to the enterprise. Further, banks should manage human resources according to modern international practices suitable to the specific conditions of Vietnam. From lessons learned on building corporate culture, which prescribes the code of conduct of leaders, officers, and employees externally and internally. At the same time, banks should let corporate cultural values accompany the bank’s development. Finally, the government should continue to deploy synchronous solutions to remove difficulties for the businesses and people affected by the Covid-19 epidemic and natural disasters.

Fourth, strengthen the capacity to build and apply management information systems and informatics infrastructure (3.0655). Modern risk management methods require complex quantitative models, large databases, high accuracy, and real-time risk analysis capabilities. Investing in information technology infrastructure and building a customer information system and an asynchronous database will strengthen the bank’s internal governance and risk management capabilities. However, while commercial banks actively invested in information technology projects, they did not made adequate investments in risk management support systems, including credit risks such as loan origination systems, collateral management systems, debt collection systems, and early warning systems. Commercial banks need specific and long-term strategies and plan to increase investment in building robust technology systems, perhaps through self-developed software or importing foreign programs. Commercial banks need to invest significantly in equipment such as intranet systems, computer software, and processing software to support appraisal work during the investment process and project evaluation. Banks are aiming to update to new, modern banking technologies to meet the needs of development and integration. Investment in information technology to analyze, assess, and measure credit risks should also be prioritized. It is necessary to perfect the information, statistics, and internal reports system to build a modern, centralized, and unified management information system and database. Banks should continue to upgrade the network and information technology infrastructure with technical solutions and communication methods suitable to the banking system’s development level. Finally, the government should direct CIs to continue creating favorable conditions for people and businesses to access credit, meet people’s legitimate needs, and contribute to limiting black credit; reduce operating costs, strive to reduce lending interest rates, reduce payment service fees; strengthen coordination with localities to promote banking-enterprise connection programs; and implement credit programs under the direction of the Government and the Prime Minister for various sectors.

Finally, implement a credit risk early warning system (3.2764). A credit risk early warning system is an integrated data processing system to automatically review all debts and detect possible deterioration, thereby helping the bank effectively manage credit portfolio quality. Credit risk early warning systems should be based on signs of customer risk such as a decline in their business situation, financial index, signs of abnormal debt repayment cash flow, and adverse market fluctuations. The system should adopt modern computational techniques and statistical modeling from historical data to provide a list of customers likely to have difficulties. This list can then be analyzed by business units and experts of specialized departments at the head office. The risk early warning indicators need to cover the leading causes of default for customers: business prospects, financial position, solvency, collateral and credit profile, and changes in management or strategy. Banks must continue building their credit risk early warning systems as an optimal step in credit risk management. This would help commercial banks prepare ready conditions for applying the Basel II Accord. Therefore, commercial banks must soon complete the credit risk early warning system. Finally, the government should implement the banking sector’s tasks in the national target programs, such as those for building new rural areas, sustainable poverty reduction, and the development of ethnic minority areas. According to the approval of the competent authority, banks should coordinate with relevant ministries and branches to continue reviewing and perfecting the legal framework for various policy initiatives.

The limitations of this study suggest areas for further research. This study used basic theoretical knowledge about credit risk management and risk management capacity in line with international practices and the current regulations in Vietnam to evaluate fully, comprehensively, and systematically the current status of credit risk management capacity in 30 commercial banks. However, this study did not apply structural equation modeling to analyze the influence of the factors constituting credit risk management capacity at commercial banks. This would require abundant, updated data with explicit origins. This analysis would indicate the level of success, limitations, and causes of rules in a realistic manner. Hence, the authors proposes further research with extensive reliable data for a quantitative assessment.

Author contributions

The author performed conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, original draft preparation, review writing, and editing and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank everyone for working at small and medium enterprises that contributed to improving the surveying conditions, and making their data publicly available. The author would like to thank the Rector of the University of Finance - Marketing (UFM).

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available in this paper and data surveyed by the author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nga Phan Thi Hang

Phan Thi Hang Nga is an Associate Professor, Dean of Science Management Department, University of Finance - Marketing (UFM), Vietnam. I graduated Doctor in Finance and Banking from the Banking University of Ho Chi Minh City. Now, I am teaching banking and financial subjects. Besides, I have successfully published many international papers on credit risk management. I also serve as a reviewer for several accredited and highly ranked international journals. These are topics of interest to managers and researchers. In addition, I also guide Ph.D. students and trainees to explore issues in banking and finance for credit risk. I have carried out many projects at ministerial and provincial levels, contributing to the adjustment of economic policies for Vietnam. Published books for specialized training in banking. In the coming time, I will focus more intensely on improving the competitiveness of digital banks in the digital economy era in Vietnam.

References

- Abu Hussain, H., & Al-Ajmi, J. (2012). Risk management practices of conventional and Islamic banks in Bahrain. Journal of Risk Finance, 13(3), 215–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265941211229244

- Alshatti, A. S. (2015). The effect of credit risk management on the financial performance of the Jordanian commercial banks. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 12(1), 338–345.

- Antunes, J., Hadi-Vencheh, A., Jamshidi, A., Tan, Y., & Wanke, P. (2021). Bank efficiency estimation in China: DEA-RENNA approach. Annals of Operations Research, 5(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-021-04111-2

- Anwen, T. G. L., & Bari, M. S. (2015). Credit risk management and its impact on the performance of commercial banks: In of case Ethiopia. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6(24), 53–64.

- Atlman, E. I. (2001). Managing credit risk, a challenge for the new millennium. Economic Notes, 31(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0300.00084

- Barnhill, T. M., Papapanagiotou, P., & Schumacher, L. (2002). Measuring integrated market and credit risk in bank portfolios: An application to a set of hypothetical banks operating in South Africa. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments, 11(5), 401–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0416.11502

- Boahene, S. H., Dasah, J., & Agyei, S. K. (2012). Credit risk and profitability of selected banks in Ghana. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(7), 6–14.

- Bono, Z. B. (2020). Effect of credit risk on the performance of commercial banks in Ethiopia. International Journal of Trend in Research and Development, 7(4), 292–298.

- Bussmann, N., Giudici, P., Marinelli, D., & Papenbrock, J. (2020). Explainable AI in fintech risk management. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 3(26), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2020.00026

- Carey, A. (2001). Effective risk management in financial institutions: The Turnbull approach. Balance Sheet, 9(3), 24–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/09657960110696014

- Channar, Z. A., Abbasi, P., & Maheshwari, M. B. (2015). Risk Management: A tool for enhancing organizational performance. Pakistan Business Review, 17(1), 1–20.

- Cheng, L., Nsiah, T. K., Ofori, C., & Ayisi, A. L. (2020). Credit risk, operational risk, liquidity risk on profitability. A study on South African commercial banks. A PLS-SEM Analysis. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(5), 1–5.

- Colesnic, O., Kounetas, K., & Michael, P. (2020). Estimating risk efficiency in Middle East banks before and after the crisis: A met frontier framework. Global Finance Journal, 46, 100484.

- Facchinetti, S., Giudici, P., & Osmetti, S. (2020). Cyber risk measurement with ordinal data. Statistical Methods and Applications, 29(1), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10260-019-00470-0

- Fan, L., & Shaffer, S. (2004). Efficiency versus risk in large domestic US banks. Managerial Finance, 30(9), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074350410769245

- Fatemi, A., & Fooladi, I. (2006). Credit risk management: A survey of practices. Managerial Finance, 32(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074350610646735

- Ferreira, C. (2021). The efficiency of European Banks in the aftermath of the financial crisis: A panel stochastic frontier approach. Journal of Economic Integration, 36(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.11130/jei.2021.36.1.103

- Gaganis, C., Galariotis, E., Pasiouras, F., & Staikouras, C. (2021). Macroprudential regulations and bank profit efficiency: International evidence. Journal of Regulatory Economics, 59(2), 136–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-021-09424-5

- Giudici, P., Hadji-Misheva, B., & Spelta, A. (2020). Network based credit risk models. Quality Engineering, 32(2), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/08982112.2019.1655159

- Gizaw, M., Kebede, M., & Selvaraj, S. (2015). The impact of credit risk on profitability performance of commercial banks in Ethiopia. African Journal of Business Management, 9(2), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2013.7171

- Hahm, J. H. (2004). Interest rate and exchange rate exposures of banking institutions in pre-crisis Korea. Applied Economics, 36(13), 1409–1419.

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (2021). Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA.

- Hassan, A. (2009). Risk management practices of Islamic banks of Brunei Darussalam. Journal of Risk Finance, 10(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265940910924472

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 4(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-09-2014-0304

- Hu, S., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Covid-19 pandemic and firm performance: Cross-country evidence. International Review of Economics & Finance, 74, 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2021.03.016

- I-Tamimi, & Al-Mazrooei, F. M. (2007). Banks’ risk management: A comparative study of UAE national and foreign banks. Journal of Risk Finance Incorporating Balance Sheet, 8(4), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265940710777333

- Kaaya, I., & Pastory, D. (2013). Credit risk and commercial banks performance in Tanzania: A panel data analysis. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 4(6), 55–61.

- Khalid, S., & Amjad, S. (2012). Risk management practices in Islamic banks of Pakistan. Journal of Risk Finance, 13(2), 148–159.

- Kozarevic, E., Nuhanovic, S., & Nurikic, M. B. (2013). Comparative analysis of risk management in conventional and Islamic banks: The case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. International Business Research, 6(5), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v6n5p180

- Laar, J. N., & Adjei, L. N. (2020). Assessing the effects of credit risk management on the financial performance of selected banks in the Ghana stock exchange. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 11(12), 79–100.

- Lotto, J. (2018). Assessing the impact of non-performing loans on the profitability of Tanzanian banks. European Journal of Accounting, Finance, and Investment, 4(10), 12–21.

- Masood, O., Al Suwaidi, H., Darshini Pun Thapa, P., & Masood, O. (2012). Credit risk management: A case differentiated Islamic and non-Islamic banks in UAE. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets, 4(2/3), 197–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/17554171211252529

- Nazir, M. S., Daniel, A., & Nawaz, M. M. (2012). Risk management practices: A comparison of conventional and Islamic banks in Pakistan. American Journal of Scientific Research, 68(1), 114–122.

- Peter, V., & Peter, R. (2011). Risk management model: An empirical assessment of the risk of default. Journal of Risk and Diversification, 3(1), 6–18.

- Rehman, Z. U., Muhammad, N., Sarwar, B., & Raz, M. A. (2019). Impact of risk management strategies on the credit risk faced by commercial banks of Balochistan. Financial Innovation, 5(1), 44–54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-019-0159-8

- Richard, E., Chijoriga, M., Kaijage, E., Peterson, C., Bohman, H., & Felix Ayadi, O. (2008). Credit risk management system of a commercial bank in Tanzania. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 3(3), 323–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/17468800810883729

- Rosman, R. (2009). Risk management practices and risk management processes of Islamic banks: A proposed framework. International Review of Business Research Papers, 5(1), 242–254.

- Salas, V., & Saurina, J. (2002). Credit risk in two institutional regimes: Spanish commercial and savings banks. Journal of Financial Services Research, 22(3), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019781109676

- Shafiq, A., & Nasr, M. (2010). Risk management practices are followed by commercial banks in Pakistan. International Review of Business Research Papers, 6(2), 308–325.

- Shafique, O., Hussain, N., & Hassan, M. T. (2013). Differences in the risk management practices of Islamic versus conventional financial institutions in Pakistan: An empirical study. The Journal of Risk Finance, 14(2), 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265941311301206

- Tchankova, L. (2002). Risk identification-basic stage in risk management. Environmental Management and Health, 13(3), 290–297.

- Vatsa, K. S. (2004). Risk, vulnerability, and asset-based approach to disaster risk management. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 24(10/11), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330410791055

- Williams, R., Bertsch, B., Dale, B., Van Der Wiele, T., Van Iwaarden, J., Smith, M., & Visser, R. (2006). Quality and risk management: What are the key issues? The TQM Magazine, 18(1), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/09544780610637703