?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Despite the growing public debate on fiscal surprise during election periods in jurisdictions where the democratic dispensation is young, comprehensive empirical works to this effect in the case of Africa are hard to find. This study, therefore, sought to contribute to the debate on two counts. First, the study examines the effect of elections on debt servicing in Africa. Second, the study investigates the joint effect of economic development and elections on debt servicing in Africa. Using data drawn from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators over the period 1985–2015 for 43 African countries, the study provides evidence from the dynamic system GMM and the ordinry least squares estimators to show that— (1) election periods are associated with lower debt servicing in Africa, and (2) economic development is significant in enhancing debt servicing commitments even in election periods. Policy recommendations are provided in line with the growing levels of debt accumulation and unemployment in Africa.

1. Introduction

The core goal of every society, be it developed or developing, is to expand the capabilities of its citizens. One of these capabilities is freedom. As Sen (Citation2000) argues, freedom, including political freedom, is not just an important factor of development, but also one of the primary outcomes of development. Contemporarily, elections have been recognised as the most preferred means through which the citizens of a country satisfy or exercise their freedoms. Elections have taken deep roots in Africa and the necessary systems and structures that support their successful conduct have been developed and implemented in many countries (Gyampo, Citation2009). Several reforms have also been carried out, all aimed at helping the citizens choose their leaders in a manner that expresses their wishes and aspirations. Evidence of these is the establishment of many independent national electoral commissions who are mandated by the constitution to administer and manage free, fair and credible elections. The voting process has also been improved upon in many African countries.

In the course of the last three decades, the democratic reforms conducted in many African countries have contributed to the successful transition of many countries from one-party, military and autocratic rule to multiparty democracy. At the heart of the transition to democracy is the holding of periodic multiparty elections. Since the re-emergence of democratic systems in Africa in 1989, Africans have used elections as the main means of choosing regional and national leaders (Gyampo, Citation2009). Elections, have, thus, been used to change a democratically-elected government for another. Between 1990 and 1998, some 70 parliamentary elections involving at least two parties were convened in 42 out of the 48 countries (Van De Walle, Citation2000). In addition, there were over 60 presidential elections with more than one candidate during this time. As of 1998, 26 countries had convened second elections, usually on schedule (Van De Walle, Citation2000).

Elections in Africa, have, thus, become a powerful tool for accountability, democracy and ultimately human development. According to Vergne (Citation2009), elections prompt accountability in two ways. Elections provide political competition and help governments to be more efficient by alleviating the moral hazard issue or mitigating the adverse selection phenomenon. By weeding out incompetent politicians and giving those in power an incentive to put in effort, elections are believed to provide suitable incentives for efficient governance. The accountability effect indicates that elections affect the incentives facing politicians. The anticipation of not being re-elected in the future leads elected officials not to shirk their obligations to the voters in the present (Barro, Citation1973; Ferejohn & Kuklinski, Citation1990; Manin, Citation1997).

Country-level analyses of the relationship between political competition and economic performance suggest that politically competitive governments perform well as far as the Human Development Index (HDI) is concerned (United Nations, Citation2016). Uncertainty over remaining in power without performance and strong political rivalry exerts some pressure on the incumbent to work towards the development of the territories. The impacts of such competition are felt most in rural areas than urban areas (Dash & Mukherjee, Citation2013). In this view, elections are seen as a sanctioning device that induces elected officials to act in the best interest of the people. However, one important condition that affects political accountability is the competitive electoral mechanisms and at the core of the electoral mechanism is the vote. The vote is the primary tool for citizens to make their governments accountable. If a large fraction of citizens does not express their opinions, elections would create no incentives for politicians to espouse or implement policies in the public interest. Elections, thus, serve to select good policies or political leaders (Rogoff, Citation1990). Free, fair and competitive elections constitute an integral part of democracy and define the basis of citizenship. The consolidation of democracy requires recurring elections that allow the citizens of a country to choose representatives (Adcock, Citation2005). According to Geys (Citation2006), elections perform three key functions in democracy. These are to discipline the elected officials by the threat of not being reappointed; to select competent individuals for public office; and to reflect the preference of a large spectrum of voters.

While election is a reliable barometer of democratic experience of a country, the very survival of democratic government is largely influenced by incumbent political party financing (Enkelmann & Leibrecht, Citation2013). A common phenomenon in mostly developing countries is that governments have the motives to renew their legitimacy and mandates in periodical recurrence of elections. The electoral pressure may lead incumbent governments to manipulate public policy in order to enhance their chances of re-election (Vergne, Citation2009). The extant literature suggests that the overall change in expenditure composition is higher in young or newly democratised countries than advanced democracies. More so, expenditure composition in election years is usually larger than in non-election years in established democracies (Enkelmann & Leibrecht, Citation2013).

For instance, evidence gathered by Drazen and Eslava (Citation2010) suggests that, in their bid to hold on to power, government in the Columbian municipalities tend to expand public expenditure on housing, health, water and energy to target voters (Enkelmann & Leibrecht, Citation2013). Although evidence based on a broad sample of countries is lacking, a study conducted by Stasavage (Citation2005) shows that the need to obtain an electoral majority may have influenced African governments to spend more on education and to prioritize primary schools over universities within the education budget. The study further shows that democratically elected African governments spend more on primary education, while spending on universities appears unaffected by democratisation.

Studies such as Katsimi and Sarantides (Citation2012), Aregbeyen and Akpan (Citation2013), and Enkelmann and Leibrecht (Citation2013) assess the effects of elections on government expenditure at a disaggregated level—recurrent, capital and infrastructure. Although these prior contributions provide a good start on the analysis concerning elections and government expenditure in the remit of the political budget cycle, the lacuna in the literature is that empirical works exploring such effects on debt servicing are hard to find. Additionally, studies such as Katsimi and Sarantides (Citation2012), Aregbeyen and Akpan (Citation2013), and Enkelmann and Leibrecht (Citation2013), which are in line with our argument, did not pay attention to the effect of economic development in mediating the effect of elections on debt servicing. In other words, this study argues that the extent of the effect of elections on debt servicing could be contingent on the level of development of a country. This is, regardless of the fierceness of the electoral contest, incumbent governments may not be significantly influenced by the electoral season. This will enable the government to have much space to cut down spending and shift some resources into the payment of the country’s debt. Indeed, in relatively developed countries that have good infrastructure, highly educated and politically discerning populace, the incumbent government will not be compelled to spend much on election years in order to solicit the vote of the electorate. On the basis of the foregoing arguments, this study contributes to the literature on two counts based on the following objectives. The first objective of the study is to examine whether elections reduce debt servicing expenditure of governments in Africa. Second, this study investigates whether economic development moderates elections to induce debt servicing obligation of governments in Africa.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: the next section provides a theoretical link between elections, government expenditure, and debt-servicing, while Section 3 outlines the methodological foundation of the study. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, and concluding remarks and policy implications are provided in Section 5.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

The electoral period-debt servicing nexus takes its roots from the political budget cycle theory (PBC). The PBC asserts that re-election minded incumbent governments have the tendency to manipulate public policy instruments (fiscal and/or monetary policy) in order to increase their chances of re-election. It is a phenomenon that is gaining attention in the political economy literature in the developing world, with the general conclusion that unchecked electioneering spending fuels policy volatility, which can have adverse implications for long-term growth, fiscal sustainability and welfare (Block, Citation2002; Brender & Drazen, Citation2005; Drazen & Eslava, Citation2010; Ebeke & Ölçer, Citation2013; Ehrhart, Citation2012; De Haan, Citation2014; Klomp & De Haan, Citation2013; Shi & Svensson, Citation2002). Alt and Lassen (Citation2006) reckon that the electoral successes of governments in less developed countries are mostly tied to their spending on items that increase their chances of re-election.

This can be explained from two perspectives. The first is the theoretical argument that since voters do not take into account the government’s intertemporal budget constraint, opportunistic policymakers take advantage of voters and use fiscal surprise to increase their chances of re-election (Chiminya & Nicolaidou, Citation2015). More importantly, because voters are known to overestimate the benefits of current expenditure and underestimate future tax burden, opportunistic politicians who seek to be re-elected take advantage of voters by increasing spending more than taxes in pre-election moments to please voters (Chiminya & Nicolaidou, Citation2015). This increases accumulation of public debt and its attendant debt servicing obligations associated with such fiscal surprise. Incumbent governments are therefore more likely to cut down debts servicing and increase spending during election periods. This contributes to the phenomenon of cyclical debt accumulation in the developing world, which in the long-run, has the potential of constraining government’s ability to undertake developmental projects.Footnote1 On the basis of the foregoing theoretical expositions, hypothesis 1 is captured as:

Elections reduce debt servicing expenditure in Africa.

Another theoretical perspective focuses on the economic determinants of electoral outcomes. In their review of the economic voting literature, Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier (Citation2000) conclude that economic management and elections are intertwined. Brender and Drazen (Citation2005) provide three reasons why expansionary fiscal policies in a pre-election year may lead to a higher re-election probability. Firstly, a fiscal expansion could stimulate economic growth. Voters may interpret more vigorous economic growth as a signal of a talented incumbent. Secondly, government expenditures for special target groups may increase the number of votes given by this group for the incumbent. Finally, voters may simply prefer low taxes and high spending and reward politicians who deliver these. In the remit of the abovementioned intuitive linkages between elections, economic development and government expenditure, of which public debt is a key component, hypothesis 2 is captured as:

Economic development moderate elections to induce debt servicing obligations in Africa.

2.1. Presidential elections in African

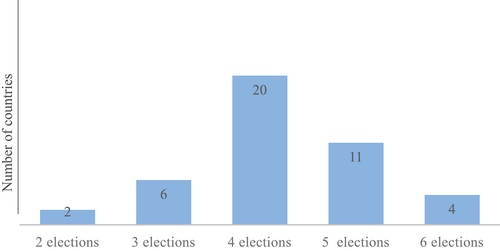

As presented in Figure , African countries have varied experiences in democratic elections. Figure shows that, over the past 30 years, the number of periodic elections held by countries in the Africa ranges from 2 to 6. From Figure , it is evident that at least 35 countries have conducted at least four presidential elections, with 41 counties holding at most three elections. This suggests that many African countries are gaining considerable experience in electoral democracies in the recent decades than in any period before.

Figure 1. Number of presidential elections by countries, international foundation for electoral systems data, 1985–2015.

The general expectation is that as countries gain experience in electoral politics, governments may conduct fiscal policies in such a way that budget deficits are not increased (Vergne, Citation2009). Though African countries are holding periodic elections in recent times, democracy in these countries is still at the developing stage, and evidence of existence of political budget cycle has been found in a number of studies (Block, Citation2002). However, it is imperative to note that the political budget cycle does not occur only in African countries as other studies have revealed the existence of politically motivated government spending in other parts of the world (Efthyvoulou, Citation2011).

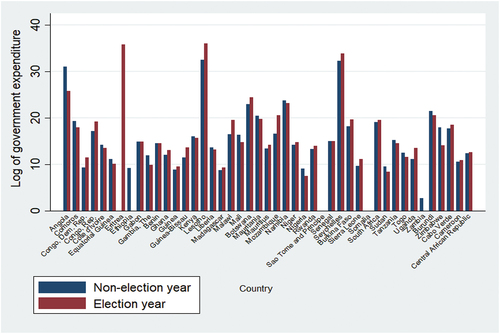

The distribution of government expenditure in election and non-election years across countries (Figure ) generally shows that government expenditures are higher during election periods than during non-election years. However, there are few exceptional countries in which government expenditures are higher in non-election years than election years. These include Angola, Comoros, Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Kenya and Liberia. Others include Namibia, Nigeria, Zambia, Burundi and Zimbabwe. Zooming into expenditures on only election years, Figure shows that within the years under consideration, Eretria, Lesotho and Seychelles experienced the highest percentage of government expenditure. It can also be observed that countries such as Ethiopia, Somalia, Sao Tome and Principe and Zambia experienced the lowest government expenditure during the period.

Figure 2. Government expenditure in pre-election and election years, world development indicators data, 1985–2015.

This distribution could be explained based on the democratic experience of the countries and other country-specific characteristics that are difficult to be captured in this descriptive analysis. Though this does not provide empirical evidence of government expenditure in election periods, it provides the basis for exploring such relationships Figure gives an idea of the trend and distribution of government expenditures in election and pre-election years, the extent of their effects is captured within the regression analysis.

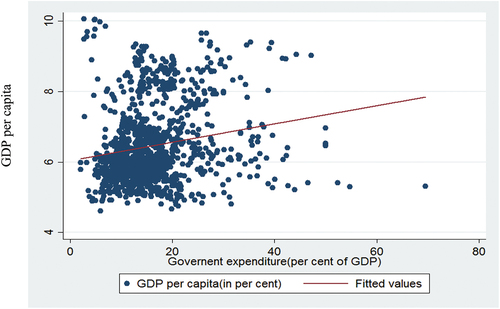

In addition to election, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is another measure of wellbeing and a determinant of the extent of government spending both in an election year and non-election year. As presented in Figure , there is a positive relationship between GDP per capita and government expenditure. A high level of GDP per capita is expected to translate into high government revenue and spending through payment of taxes by the citizens. Figure is that with the exception of a few outliers, expenditures do not vary so significantly from the mean spending.

Figure 3. Government expenditure and GDP per capita, world development indicators data data, 1985–2015.

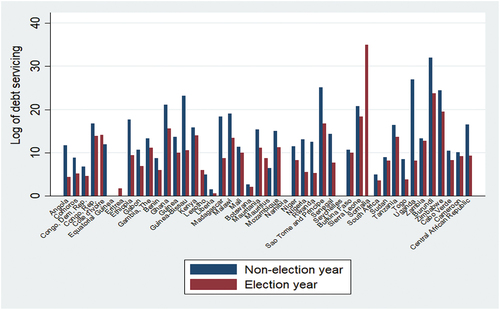

Experience in most developing countries has shown that in order to influence the electoral outcomes, incumbent governments sometimes divert funds meant for debt servicing to the provision of tangible projects in their bid to retain power (Sáez, Citation2016). This in turn leads to a reduction in debt servicing, particularly in election years, and further accumulation of public debt in subsequent years. In Figure , this issue is presented using histogram to show the distribution of debt servicing in election and non-election years. It is imperative to note that debt servicing is captured as the sum of principal repayment and interest actually paid in currency, goods or services on long-term debt, interest paid on short-term debt, and repayments (repurchases and charges to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Figure indicates that like government expenditure, average debt servicing of majority of the countries is higher in non-election years than in election years. In other words, debt servicing is very low in election years in almost all the countries considered in this analysis.

Figure 4. The distribution of debt servicing on election by country, international financial statistics data, 1985–2015.

The links between election periods, economic development and debt servicing as I show in section is worth exploring empirically and the next section provides the methods adopted in doing so.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data, variable measurement and a priori expectations

The analysis is based on annual macrodata on a sample of 43 Africa countries for the period 1985–2015. All 54 African countries were initially considered but due to some missing observations for some countries, the sample size dropped 43. For instance, countries such as Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya were automatically excluded from the analysis because they do not have consistent democratic elections. In the same vein, countries such as Djibouti, South Sudan, Chad and Swaziland were excluded because they had significantly large missing observations. Moreover, countries such as Eritrea and Somalia are now recovering from civil unrests or in the process of strengthening their democracies and as such were excluded from this study.

The outcome variable in this study is debt servicing. Our attention on debt servicing is from policy sense and the centres on the growing concern that a greater part of government expenditure in Africa is recurrent. This study captures debt servicing as the sum of principal repayments and interest actually paid in currency, goods, or services on long-term debt, interest paid on short-term debt, and repayments (repurchases and charges) to the IMF. Election is the main variable of interest in this study and it is captured as a dummy, taking on the value 1 if election was held in a particular country and 0 if otherwise. Theory posits that government in developing or young democracies use fiscal surprise to influence voters’ decision during election years. This affects their ability to remain committed to their debt servicing obligations. As a result, it is expected that election period or years of election should be positively associated with government expenditure but negatively associated with debt servicing.

For control variables, we consider covariates such as economic growth, inflation, unemployment, governance system and electoral system to (1) mitigate possible omitted variable bias, (2) take into account the nature of the real sector of Africa, and (3) capture the effect in institutions in fostering equitable income growth and distribution. The study proxies economic growth (i.e., the moderating variable in this study) by GDP per capita and is measured as the gross domestic product divided by the population size of the country in question. It used to denote the level of development of a country as this could influence voters’ preference for public goods and hence the level of government spending. It is expected to increase government expenditure and debt servicing. I also include the inflation rate as it may affect government receipts and expenditures through nominal progression in tax rates, and tax brackets, and through price indexation of receipts and expenditures (Klomp & De Haan, Citation2013). However, Mink and De Haan (Citation2006) argue that unexpected inflation erodes the real value of nominal government debt so that the overall effect of inflation on total spending and debt servicing. In view of this, it is expected that inflation should have a negative effect on debt servicing.

The inclusion of the unemployment rate as another control stems from its direct link with government spending and revenues. This follows the argument that high unemployment does not only lead to increasing levels of government spending on social transfers but also a reduction in tax revenue generation, hence constrains government capacity to service its debts. The study captures election years as dummies created for the election and pre-election years. An election year dummy takes on a value of 1 if election is held in that year and 0 if otherwise. In creating the dummies for the two-election variable, the study considers only the year for the election and the year before. Finally, following Persson and Tabellini (Citation2002) and Klomp and De Haan (Citation2013), the study takes into account the type of a country’s governance system and electoral system. To take this into account empirically, the study creates a binary variable, where 1 is for simple majority system and presidential system. This is in line with the argument by Persson and Tabellini (Citation2002) and Klomp and De Haan (Citation2013) have argued that elections may have different effects on fiscal policy under different electoral and governance systems. In conformity with our hypothesized pathway effect, I include an interaction term between economic development (GDP per capita) and Election year in the model. It is expected that the net effect of the interaction term will be positive. The description and data sources of the variables are presented in Table

Table 1. Description of variables and data sources

3.2. Theoretical model specification

Following Drazen and Eslava (Citation2010), the study relies on the signalling model of Rogoff (Citation1990) as the theoretical foundation of this paper. The model is built on the following principles—first, there are two periods, whereby Period 1 is before an election and Period 2 is after an election; and second, policy instruments, which are exogenous tax (levied in each period), and two public goods. The first good which is represented by the variable is a short-term public good. With this good, voters can see immediately what is being provided, while the second good represented by the variable

is a long-term public (investment) good. It is important to indicate that voters cannot see how much is spent in this period until the next period. The third principle is the preferences and conflict of interest, which can be further looked at in three forms: (a) voters and politicians have the same preferences over public goods; (b) Politicians get ego-rent from being in office, and (c) The conflict of interest is not about rents, but about the competency of the politician. In this model, the representative voter’s two period utility can be specified as:

In EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) , the variable

represents income, which is also assumed to be non-discounting, whereas

represents the exogenous tax. In line with EquationEquation 1

(1)

(1) , the two-period utility function for a politician can specify as:

In EquationEquation 2(2)

(2) ,

> 0 is the ego-rent of re-election and

= 1 if re-elected and zero if not re-elected. The utility of the voter is influenced by government policy, which is also dependent on the type of the politician. The politician is either competent (

) or incompetent (

and this can be functionally summarised as:

. Competence is defined in the context of how good the politician is when it comes to the production of public goods:

From EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) , the variable

represents the lasting competency of a politician of the type

with

. The probability that a randomly selected politician is competent

can be written as

. Similarly, the probability that a randomly selected politician is incompetent

can be written as

. At the beginning of Period 1, the incumbent observes his competency

and decides on how to allocate tax revenues between the two public goods

). However, voters observe how much is spent on

but not what is spent

. At the end of Period 1, if an election takes place where the incumbent runs against a randomly chosen challenger, he is either re-elected if he is supported by a majority of the voters or otherwise the challenger takes office. If the incumbent is re-elected, he spends the post-election budget on the short-run public good

at the beginning of period 2. Nonetheless, if the challenger is elected, she observes her competency and spends the post-election budget on the short-run public good

. In Period 2, the politician (either incumbent or the challenger) spends all taxes on short-term public goods:

. In Period 1, the politicians and the voters equally care about policy. Therefore, the maximized decision in Periods 1 and 2 can be functionally written as:

The decisions in the two periods are subject to the constraint:

The logarithmic form of the utility for the two periods, which also represents the preference of voters can be specified as:

In EquationEquation (5)(5)

(5) ,

represents the long-term expenditure of the incumbent or government, while

is its short-term expenditure. The voters’ re-election of competent politicians is based the trust that they repose in them (the incumbent) in providing more post-election public goods. The voters observe what the incumbent does before the election

and use that to estimate the level of competence of the incumbent. Based on this estimate, voters re-elect the incumbent if they think it is sufficiently likely that the incumbent will be competent or elect the challenger if otherwise. Being guided by their desire for re-election, they have the incentive to provide lots of short-term public goods at the cost of long-term public goods during the pre-election period if that will enable them get re-elected. EquationEquation 5

(5)

(5) can be further expanded in the form of Equationequation 6

(6)

(6) to include other control variables that influence the incumbent’s (government) spending in the short term:

From EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) ,

is the vector of other factors that influence government spending,

is the vector of coefficients of those explanatory variables, while

represents the error term.

3.3. Empirical model specification

The study adopts the pooled least, fixed-effect, random-effect, and the dynamic system generalized method of moment put forward by Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) for the empirical analysis. Unlike its static counterpart, the dynamic system GMM allows for the testing of the relationship between the dependent variable (debt servicing) and its lagged values (see, Ofori & Asongu, Citation2021). The choice of system GMM is informed by the fact that election year, which is the regressor of interest is not entirely exogenous in reality. Evidence suggests that the timing of elections and the fiscal policies could be affected by a common set of unobserved variables, including crises or social unrest, which can be hardly included in the specification of the regression model (Shi & Svensson, Citation2002). As a result, failure to consider the endogenous nature of election has the potential to bias the estimatesFootnote2 and render the attendant inferences flawed (see, Ofori et al., Citation2022c, Citation2022a, Citation2022b). It is important to indicate that apart from the potential endogeneity between election and government expenditure. That said, the study specifies the dynamic panel model as:

Where Debt represents debt servicing; Inf is the rate of inflation; Unemp represents unemployment rate; Sysgov is the system of governance; ADR represents age dependency ratio; and Elsys is the electoral system in the respective countries. The interaction between the election year and level of economic development (GDP per capita) is captured as Elect*Gdpcap. The instruments used in the GMM regressions are the lagged levels (two periods) of the dependent variable, which is debt servicing, and GDP per capita for the difference equation, and lagged difference (one period) for the level equation.

In assessing the robustness of the system GMM estimates, the Sargan test and Hansen J statistics are examined. Though both the Sargan and Hansen J statistic perform the same function and have the same null hypothesis, the results for both tests are reported in the interest of comparison. The Hansen/Sargan test is premised on the null hypothesis that the set of identified instruments and the residuals are uncorrelated. Hence, the appropriateness of the instruments and thus the robustness of our estimates depends on the failure to reject the null hypothesis. On the other hand, if the null hypothesis is rejected, then the instruments are not robust because the restrictions imposed by relying on the instruments are invalid (Ofori et al., Citation2022d, Citation2021; Ofori & Asongu, Citation2021). Further, we test whether there is evidence of second-order serial correlation in the residuals or not, and finally, whether our joint effects are significant.

Finally, to determine the net effects from the interaction term for elections and economic development on debt servicing from EquationEquations (7(7)

(7) ), EquationEquation (8)

(8)

(8) is presented.

where is the mean of GDP per capita.

4. Results and discussion

In this section, our results on the conditional and unconditional effects of election on debt servicing in Africa are presented. The section is sub-divided into two—(a) the preliminary results concerning summary statistics, and unit root testsFootnote3 of the variables and (b) presentation and discussion of the regression estimates.

4.1. Descriptive analysis

In this section, the analysis of the relationship between the variables and election periods is presented. For brevity, variables such as GDP growth, unemployment rate, GDP per capita and inflation rate are presented. The distribution of the variables as depicted in Table shows that government expenditure, unemployment and inflation differ significantly in election and non-election periods. I point out that the full summary statistics of all the variables are presented in Table in the Appendix section.

Table 2. Distribution of means of some selected variables across years of election

Table shows that the mean unemployment rate is 8.2% in election years and 6.7% in non-election years. This indicates that governments strive to reduce unemployment in election years rather than in non-election years. This is evident in developing countries as incumbent governments, in their bid to influence electoral outcome and retain power embark on several projects in election years more than in other years in the electoral cycle (Kroth, Citation2012). Also, Table shows that the mean inflation rate is higher in election years than in non-election years. The mean inflation rate is 65.2% in election years as compared to 59.7% in non-election years. The higher inflation rate in election years can be linked to a rise in general government spending that rises in during election years as compared to non-election years. The higher government spending is inflationary because much of the increase goes into recurrent spending. The average GDP per capita in log terms is 6.4 in both election and non-election years. The results indicate higher economic performance in pre-election years than in election years. This evidence is revealing against the backdrop that government expenditure increases during election years rather than pre-election years suggesting that the increase in government expenditure contributes less to growth.

The brief descriptive analysis has shown that governments’ fiscal policies and other core responsibilities are largely shaped by election seasons in Africa. It is observed that in majority of the countries understudied, government expenditure increases in election years more than non-election years. On the contrast, government debt servicing reduces in election years than non-election years. This indicates that governments in Africa are likely to cut down on debt servicing and shift it into spending that would enhance their chance of retaining power. However, the extent of the effect of election on government’s fiscal decision has not been captured.

4.2. Results on the effects of election and economic development on debt servicing

In this section, results on the effect of elections on debt servicing are presented. This is preceded by a bivariate regression analysis where the relationship between debt servicing and election variables are examined.

The results as reported in Table reveal that debt servicing is negatively associated with election periods. Conversely, the study finds that debt servicing is positively associated with both governance system and electoral system. It is therefore expected that these associations will be replicated in the estimates of the multivariate analyses. In this analysis, it is expected that barring any re-negotiations for debt cancellation, a country’s previous year’s debt servicing should impact current debt negatively. In other words, an increase in debt servicing in previous years should reduce current debt level.

Table 3. Bivariate estimates for effect of election variables on debt servicing (dependent variable: debt servicing)

4.3. Main results for the effects of election and economic development on debt servicing

In this section, our main results on the election-debt servicing relationship in the case of Africa are presented. For the sake of robustness and efficiency, the study runs on least squares, fixed effect, random effect and the GMM estimators. Considering the fact that our variable of interest, election, is dichotomous and on pure econometric grounds, its estimates are dropped by the fixed effect estimator, we pay attention to the OLS and random effect estimates.

That said, we decide on whether it is appropriate to analyse the OLS or random effect estimates. To this end, we invoke the Breusch and Pagan LaGrange Multiplier (LM) test, which reveals no evidence of significant differences across countries. The study therefore pays attention to the OLS and the GMM estimates. The study finds evidence for the first objective. The results as apparent in Table show that election periods are negatively associated with debt servicing in African countries. At the 1 percent level of significance, election years compared to non-election years are associated with a reduction in debt servicing by approximately 20% in the GMM model. What can be deduced from this result is that during election years, government channels resources meant for repaying the debts and the associated interest rates into other spending that may have direct bearing on their chances of being re-elected? Results on the effect of election and economic development on debt servicing.

Table 4. Effect of electoral on government debt servicing (dependent variable: debt servicing)

Further, the study finds evidence at a 1 percent level of significance that economic development (GDP per capita) directly reduces debt servicing. The results indicate that a 1 percent increase in GDP per capita reduces debt servicing by 0.04%. Indeed, a high GDP per capita indicates a high level of development and thus low debt accumulation, which then results in low interest on debt. Further, as economies develop, the necessary structures to translate contracted loans into productive investments to yield higher returns improve, enabling policymakers to repay its debts. Thus, economic development creates fiscal space for policymakers to embark on developmental projects that enable them to avoid debt accumulation and debt servicing. This ushers us into Objective 2 of the study. The results provide strong empirical evidence for the hypothesized positive pathway effect of elections on debt servicing through economic development. That said, we proceed to compute net effects of election periods on debt servicing conditioned on the level of development is 13.6% in the OLS model and 15.64% in the system GMM estimation. The net effect for our OLS model is computed as:

Likewise, for our system GMM estimates, the net effect of elections and economic development is calculated as:

Compared to its direct effect, the indirect pathway effect of elections on debt servicing through the level of economic development yield similar results. This means that although incumbent governments in young democracies may cut down on debt servicing during electoral periods, the level of development matters for the magnitude of such reduction. Thus, in relatively developed countries, election periods are not enough to sway the government from committing to their debt servicing obligations. Alternatively, in developed countries, incumbent governments do not need to spend much during election periods to the extent that they will be compelled to re-channel funds meant for servicing debts into expenditures meant to attract votes.

For our ancillary findings, we find that unemployment has a 0.26% dampening effect on debt servicing. The high rate of unemployment limits the government’s ability to service its debts as resources intended for such purposes are channelled into creating avenues and other social services. This means that in order for government in African countries to be able to service their debts effectively, they would have to create enough employment opportunities for their citizens. This can be an effective way by which governments can mobilise enough revenue to repay their internal and external debts. This result is in line with a study conducted in Pakistan by Ayyoub et al. (Citation2012) who found that high debt was one of the factors responsible for increasing unemployment. Also, the study finds that the system of governance is directly associated with government’s fiscal and debt repayment decisions. The results show that relative to the parliamentary system of governance, government debt servicing increases by 0.018 percentage points if the country operates the presidential system of governance, through statistical significance eludes us. From these results, one can deduce that in the presidential system of governance, public expenditures on the size of government are not as high as the parliamentary system where the size of government expenditure on the large size of the legislature exert much constraint on the governments’ ability to repay their debts.

Additionally, the results show that inflation has a positive effect on debt servicing. The magnitude of the coefficient of inflation suggests that a 1 percent increase in inflation increases debt servicing by 0.22%, holding all other factors constant. The interpretation of this result requires some caution in the sense that the positive association does not necessarily mean that inflation creates more revenues that enable government to increase its debt servicing. Instead, it increases the cost of debt servicing, which consequently increases the amount required to service debt. Therefore, effective debt servicing requires a moderate or low level of inflation. There is also strong empirical evidence that previous year’s debt servicing reduces current debt servicing by approximately 0.014%. This is intuitively right because an increase in previous debts servicing reduces the debt stock and the associated interest. The results indicate that in addressing the accumulation of debt, governments of African countries would have to pay critical attention to the debts accumulated before and during election seasons. In other words, the impact of political variables on a state government’s fiscal expenditures on interest payments on the debt need to be considered.

The reliability of our estimates is evident in the satisfaction of a number of post-estimation tests presented in Table . Evidence gleaned from Table indicates that our instruments are not over-identified and there is also the absence of second-order serial correlations in the residuals.

5. Conclusion and policy recommendations

Motivated by the theoretical proposition that governments in young democracies use fiscal surprise in election periods, the study examines the effect of elections on debt servicing in Africa. Further, I test whether the level of economic development of a country modulates the effect of elections on debt servicing in Africa. Using data over the period 1985–2015 for 43 Africa countries (see, Table ), the study provides evidence from the dynamic system generalized method of moments to show that: (1) election periods are negatively associated with debt servicing in African countries, and (2) economic development is significant in enhancing debt servicing commitments even in election periods. The study concludes that during election periods, governments in Africa reduce debt servicing and channel it into activities that either promote development or place them in a better position to retain power. Further, the study find that the positive effect of economic development outweighs the negative effect of election periods on debts servicing. Thus, in countries with high economic development, election periods are not enough to cause governments in young democracies to reduce their debt servicing commitments for election-related fiscal surprise.

The study recommends that governments in Africa avoid election-related fiscal surprise and adhere to their debt servicing obligations irrespective of the electoral pressure in order to avoid debt accumulation and its consequential effect on long-term development. Spending that promotes development and a high level of literacy is essential to ease the pressure on government to please the populace through spending on tangible projects during election periods. Also, considering debt accumulation of the countries and our results for unemployment, the study recommends that policymakers channel development finance judiciously, for example, in reducing the continent’s huge infrastructure deficit. This can go a long way to create a congenial environment for the private to thrive and spur employment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In developed jurisdictions, however, evidence shows that governments’ chances of winning election are not necessarily contingent on its expenditure and thus have some degree of freedom to service their debts (Hallerberg & Von Hagen, Citation1997).

2. Specifically, there will be a downward bias when the omitted variable correlates positively with election timing and negatively with fiscal policy outcomes such as government expenditure (Shi & Svensson, Citation2002).

3. See the unit root test results at level and first difference in Table and Table , respectively.

References

- Adcock, C. (2005). Violent obstacles to democratic consolidation in three countries: Guatemala, Columbia and Algeria. http://www.csa.com/discovery gui des/demo/overview.php

- Alt, J., & Lassen, D. (2006). Transparency, political polarization and political budget cycles in OECD countries. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 530–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00200.x

- Aregbeyen, O. O., & Akpan, U. F. (2013). Long-term determinants of government expenditure: A disaggregated analysis for Nigeria. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences, 5(1), 31–87. https://infinitypress.info/index.php/jsss/article/view/256

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968

- Ayyoub, M., Chaudhry, I. S., & Yaqub, S. (2012). Debt burden of Pakistan: Impact and remedies for future. Universal Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 2(7), 29–40.

- Barro, R. J. (1973). The control of politicians: An economic model. Public Choice, 14(1), 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01718440

- Block, S. A. (2002). Political business cycles, democratisation, and economic reforms: The case of Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 67(1), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00184-5

- Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2005). Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(7), 1271–1295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.04.004

- Chiminya, A., & Nicolaidou, E. (2015). An empirical investigation into the determinants of external debt in Sub Saharan Africa. Paper presented at the Biennial Conference of The Economic Society of South Africa (pp. 11–22). University of Cape Town. http://2015.essa.org.za/fullpaper/essa_3098

- Dash, B. B., & Mukherjee, S. (2013). Does political competition influence human development? Evidence from the Indian States. National Institute of Public Finance and Policy.

- De Haan, J. (2014). Democracy, elections and government budget deficits. German Economic Review, 15(1), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12022

- Drazen, A., & Eslava, M. (2010). Electoral manipulation via voter-friendly spending: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 92(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.01.001

- Ebeke, C., & Ölçer, D. (2013). Fiscal policy over the election cycle in low-income countries. IMF.

- Efthyvoulou, G. (2011). Political budget cycles in the European Union and the impact of political pressures. Public Choice, 153(3), 295–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9795-x

- Ehrhart, H. (2012). Elections and the structure of taxation in developing countries. Public Choice, 10(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9894-8

- Enkelmann, S., & Leibrecht, M. (2013). Political expenditure cycles and election outcomes: Evidence from disaggregation of public expenditures by economic functions. Economics Letters, 121(1), 128–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.07.015

- Ferejohn, J. A., & Kuklinski, J. H. (1990). Information and democratic processes. Illinois: University of Illinois Press.

- Geys, N. (2006). Explaining turnout: A review of aggregate-level research. Electoral Studies, 25(4), 637–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2005.09.002

- Gyampo, R. E. (2009). Rejected ballots in democratic consolidation in Ghana’s fourth republic. African Research Review, 3(3), 282–296. https://doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.v3i3.47530

- Hallerberg, M., & Von Hagen, J. (1997). Electoral institutions and the budget process. Georgia Tech Center for International Business Education and Research, School of Management, Georgia Institute of Technology.

- Katsimi, M., & Sarantides, V. (2012). Do elections affect the composition of fiscal policy in developed, established democracies? Public Choice, 151(1–2), 352–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9749-8

- Klomp, J., & De Haan, J. (2013). Political budget cycles and electoral outcomes. Public Choice, 157(1–2), 245–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-012-9943-y

- Kroth, V. (2012). Political budget cycles and intergovernmental transfers in a dominant party framework: Empirical evidence from South Africa. School of Economics and Political Science.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., & Stegmaier, M. (2000). Economic determinants of electoral outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 3(1), 183–219. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183

- Manin, B. (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge University Press.

- Mink, M., & De Haan, J. (2006). Are there political budget cycles in the euro area? European Union Politics, 7(2), 191–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116506063706

- Ofori, I. K., Armah, M. K., & Asmah, E. E. (2022c). Towards the reversal of poverty and income inequality setbacks due to COVID-19: The role of globalisation and resource allocation. International Review of Applied Economics, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2022.2029367

- Ofori, I. K., Armah, M. K., Taale, F., & Ofori, P. E. (2021). Addressing the severity and intensity of poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa: How relevant is the ICT and financial development pathway? Heliyon, 7(10), e08156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08156

- Ofori, I. K., & Asongu, S. A. (2021). ICT diffusion, FDI and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telematics and Informatics, 65(1), 101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101718

- Ofori, I. K., Cantah, W. G., Afful Jr, B., & Hossain, S. (2022a). Towards shared prosperity in Sub-Saharan Africa: How does the effect of economic integration compare to social equity policies? African Development Review, 34(1) , 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12614

- Ofori, I. K., Dossou, T. A. M., & Akadiri, P. E. (2022b). Towards the quest to reduce income inequality in Africa: Is there a synergy between tourism development and governance? Current Issues in Tourism, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.2021157

- Ofori, I. K., Osei, D. B., & Alagidede, I. P. (2022). Inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Exploring the interaction between ICT diffusion, and financial development. Telecommunications Policy, 46(7), 102315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2022.102315

- Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2002). Do electoral systems differ across political systems? University Press.

- Rogoff, K. (1990). Equilibrium political budget cycles. American Economic Review, 80, 21–36. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w2428/w2428.pdf

- Sáez, L. (2016). The political budget cycle and subnational debt expenditures in federations: Panel data evidence from India. Governance, 29(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12130

- Sen, A. (2000). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Shi, M., & Svensson, J. (2002). Political budget cycles in developed and developing countries. Stockholm University Press.

- Stasavage, D. (2005). Democracy and education spending in Africa. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00127.x

- United Nations. (2016). Economic development in Africa report 2016: Debt dynamics and development finance in Africa.

- Van De Walle, N. (2000). The impact of multiparty elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. A paper prepared for delivery at the Norwegian Association for Development Research Annual Conference, The state under pressure, 5-6 October, 2000, Bergen, Norway.

- Vergne, C. (2009). Democracy, elections and allocation of public expenditures in developing countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 25(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.09.003

Appendices

Table A1. Unit root test results for the variables at levels

Table A2.

Unit root test results for the variables at first difference

Table A3.

Variables included in the debt servicing model

Table A4.

Post-estimation test for the GMM estimations

Table A5.

List of countries in the study