?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The informal sector constitutes a vital part of developing countries’ economy. It serves as a major source of employment and livelihood for the urban poor. However, despite its multifaceted economic contributions in many developing countries, little is known about its contribution. Hence, this study examines the role of the urban informal sector in improving the livelihoods of the participants in Hawassa city, southern Ethiopia, using primary data. A random sample of 182 informal sector participants was selected from eight kebeles using multi-stage sampling techniques. Descriptive statistics and a logistic regression model were used to analyze the data. The descriptive analysis results showed that the majority of the participants (67%) perceived that participating in the informal sector has considerably improved their livelihood. The econometric analysis reveals that informal business operators who earn a higher monthly income, those who save their income, stayed longer in the business, have access to credit and own more working capital, and those who get training opportunities are observed to have better livelihood improvement compared to their comparative group. Given the sector’s role in creating employment opportunities for the burgeoning urban labor force and improving livelihood, informal businesses should not be treated as a hostile group with a marginal role in the economy. Thus, along with designing strategies for the formalization of informal enterprises, facilitating access to finance, training programs, improving the business environment, and provision of business development services prepare youth to navigate the informal sector in the study area, in particular, and Ethiopia, in general.

1. Introduction

International Labor Organization ILO (Citation2021) defines the informal sector as all economic activities by workers and economic units that are in law or practice—either not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements, unlike the formal counterparts. In developing countries, the informal sector accounts for up to half of the economic activity. It provides a livelihood for billions of people. Nevertheless, its role in economic development remains controversial (La Porta & Shleifer, Citation2014). The controversial issues of the role played by the informal sector in absorbing urban unemployed youth have attracted great interest in the economic development literature. At this moment, the importance and contribution of the informal sector can be understood in the multitudes of economic, social, and geographic differences in the international context of the sector. In many countries, especially in developing countries, informal sectors are commercial by nature organized, owned, and operated mostly by the poor. They account for a substantial share of the total employment and contribute significantly to the alleviation of youth unemployment, income generation, and improved livelihood. The sector can be beneficial to growth as it provides de facto flexibility for firms that would be otherwise constrained by burdensome regulations (Meghir et al., Citation2015).

Moreover, the sector has not only reduced youth unemployment but also made a paramount contribution to overall national income and employment (Benjamin et al., Citation2014). According to Schneider and Enste (Citation2013) estimation, the informal sector contributes about 19% of the GDP in OECD nations, 30% in transitional nations, and 45% in developing nations in the 2000s.

Current patterns show that the informal economy is growing in cities, particularly in those where urbanization is taking place quickly (Elgin & Oyvat, Citation2013; Satterthwaite & Mitlin, Citation2013). In developing nations, it represents more than half of all non-agricultural employment, and significantly more in those areas that are rapid urbanization, including 82% in South Asia, 66% in sub-Saharan Africa, and 65% in East and Southeast Asia (Vanek et al., Citation2014). Within sub-Saharan Africa, informal employment is the main source of employment in Central Africa (91.0 %), Eastern Africa (91.6 %), and Western Africa (92.4 %) (ILO, Citation2018). Theoretical models of rural–urban migration such as the Haris-Todaro model indicate that because of urbanization in developing countries and the associated rural–urban influx of people are not accompanied by industrialization and expansion of employment opportunities in the formal sector, most of the migrants and the urban labor force add to the existing pool of urban unemployment (Harris & Todaro, Citation1970). In other words, owing to the limited number of job opportunities in the urban formal sector (notably due to the slow growth of employment in manufacturing and elsewhere), the bulk of new entrants to the urban labor force remains unemployed and hence seemed to create their own employment or to work for small-scale family-owned enterprises in the informal sector.

Ethiopia is experiencing rapid urbanization and massive rural–urban migration of people. This high rate of urbanization places Ethiopia’s urban centers under great stress, one being unemployment (Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Citation2004). Hawassa city is a rapidly expanding city in Ethiopia. According to the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency’s estimation, the population of Hawassa city was 351,469 and it had an annual population growth rate of 4% (Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Citation2020). About 65% of the population are young and under 25 years of age, while 5.5% are over 50 years of age. There is a high rate of unemployment in the city. According to the Central Statistical Agency (CSA; Citation2004), the rate of unemployment in Hawassa city is 29%. It is estimated that 48,864 people are unemployed, of which 51.55% are female and 48.45% are male (BoFED, Citation2018).

There has been a general outcry on the persistent rise in the unemployment rate in Ethiopia in general and Hawassa city in particular. However, the formal sector is unable to provide job opportunities to the increasing number of youths. Owing to this, an increasing number of youth people are becoming dependent on the informal sector as an important source of employment and a means of livelihood.

The informal sector, which ought to be a saving grace for the unemployed youth, has continued to suffer from the problems of the shortage of working capital, lack of working places, inadequate market, lack of raw materials, and technical support (Asmamaw, Citation2014). Moreover, the sector is also facing problems related to a lack of access to organized markets, credit, modern technologies, formal training, and public services (ILO, Citation2015). Besides, they do not have a fixed place to work; as a result, they often carry out their business in small shops, street vendors, outlets, home-based activities, and chest shapes (Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Citation2004, Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Citation2020). What is more, apart from limited or no access to credit from financial institutions, they also experience eviction by urban authorities (Admasu, Citation2019) since they are seen as denying the government tax revenue.

Notwithstanding the challenges, the urban informal sector activities have become a key pathway to increasing income and improving livelihood in urban centers. The sector plays a significant role in income generation, reducing unemployment and thereby contributing to the livelihood of the urban poor (Admasu et al., Citation2019). In addition, the sector plays an important role in urban unemployment alleviation by creating jobs and poverty reduction (Reddy et al., Citation2003). Moreover, the sector also provides a wide range of services and produces a variety of basic goods and services that can be used by all classes of consumers, especially low-income groups (Asmamaw, Citation2014). The significance of informal sector activities is gradually emerging worldwide (Darbi & Knott, Citation2016) as a tool for reducing poverty (Chidoko & Makuyana, Citation2012), which has been noted as a key challenge to humanity (Sutter et al., Citation2019). Thus, informal sector activities are viable in reducing poverty for youth men and women in the informal sector.

However, despite its predominant economic contribution in developing countries, including Ethiopia, little is known about the informal sector’s contribution (Nordman et al., Citation2016). Some works have been carried out in this field using household surveys, but they only consider some emerging countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia (Bargain & Kwenda, Citation2011, Citation2014), Mexico (Gong et al., Citation2004)., South Africa, Ghana, and Tanzania (Bargain & Kwenda, Citation2011, Citation2014), Ethiopia (Asmamaw, Citation2010, Citation2014; Delbiso, Citation2013; Delbiso et al., Citation2018; Fillmon, Citation2011), urban Africa (Falco et al., Citation2011), Vietnam (Nguyen et al., Citation2013),) (Doğrul, Citation2012) for Turkey, and (Nordman et al., Citation2016) for Madagascar.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to generalize these results to other parts of the developing world such as Ethiopia, in general, and Hawassa city, in particular, where the informal sector is the most widespread. Particularly, the studies conducted on the informal sector (which refers to street vending in this study) were inadequate and the information available is largely deficient and locality specific in Africa (Mengistu & Jibat, Citation2015). Negligence of the sector has resulted in the lack of accurate estimates of its size, particularly street vendors. As a result, there is less understanding of the contribution and role it plays in making the life of the poor safe and easy (Mengistu & Jibat, Citation2015). Moreover, the studies conducted so far are concerned with the controversies on informal sector operation with emphasis on problems and prospects for a development strategy, earnings gaps between the informal and formal sector, determinants, and challenges of participants in the informal sector in other countries. Even if the informal sector is becoming the major employer, there is no detailed investigation regarding the role of the informal sector in improving livelihood, and challenges facing the sector in Ethiopia, in general, and in cities harboring the bulk of the informal activities like Hawassa city, in particular. Only a few studies were conducted on the study subject in Ethiopia. Regarding this, Fillmon (Citation2011) examined the role of the informal sector on household livelihood by taking a survey of street vendors in Mekelle city using a descriptive approach; and Delbiso (Citation2013) assessed the role of the informal sector in reducing youth unemployment in Hawassa city.

Unlike the extant studies that used household surveys, this study adds to the pool of knowledge by examining the contribution of the sector to livelihood improvement using the enterprise survey that directly captures the business establishments and perception of the informal sector participants (street vendors) about changes in their livelihood status. Besides, previous empirical studies used a descriptive approach and did not identify the type of informal business activities that is crucial to formulate appropriate policies. Therefore, this study examined the role of the urban informal sector in improving the livelihood of participants and the type of livelihood improvement of the participant using the descriptive and econometric approach. In particular, we assessed the perceived impact of participation in the informal sector on the livelihood status of the participants. We also explored the type of informal sector activities operated by the participants and the major challenges facing the sector in Hawassa city, Southern Ethiopia.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the extant literature, and Section 3 offers the materials and methods used to analyze the data. Section 4 reports the results and discusses the findings, and the final section draws concluding remarks.

2. Literature review

2.1. Definition, conceptualization, and drivers of the informal sector

The informal sector exists in all countries, irrespective of the individual country’s level of socioeconomic development, but it is far more prevalent in developing countries. There is no universally accepted definition of the informal sector. The informal sector generally refers to an unofficial, underground, hidden, invisible, shadow, parallel, second, unregulated, unrecorded, unmeasured, and unobserved economy (World Customs Organization, Citation2015). It is considered to be marginal or peripheral and not linked to the formal sector or to modern capitalist development. For this reason, it was viewed to disappear once developing countries achieved sufficient levels of economic growth or modern industrial development (Chen, Citation2012).

The term informal sector as used in this study refers to those unorganized, unregulated, and mostly legal but unregistered micro businesses operating on a small scale on the streets. In other words, as indicated by De Soto (Citation2000); Soto (Citation1989), and structuralists, we emphasized “micro-entrepreneurs” who choose to operate informally, mostly in an unauthorized space on the streets. In particular, we considered youth-owned street vending activities that serve as a source of employment opportunities and means of livelihood for the growing youth population in Hawassa city.

In terms of role, the informal economy provides the largest share of employment globally and is vital to the jobs, incomes, and consumption of poor women and men. Of those that are employed globally, 61.2% are in the informal economy (ILO, 2018). Poor people are more likely to be in informal than formal employment (Avirgan et al., Citation2005; International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Citation2016; ILO, 2018; (Bonnet et al., Citation2019). Informality rates are higher among young people, the elderly, women, minority ethnic communities, migrants, workers with disabilities, and, more generally, those groups in society that experience economic and social disadvantage, labor market discrimination, and lack of adequate access to education, training, and capital (Pathways Commission, 2018).

Different schools of thought conceptualized the nature of the informal sector and pointed out the causes for its emergence. Here we highlighted the central ideas of each strand of thought.

According to the Dualist school, the informal sector of the economy consists of marginal activities that are distinct from and unrelated to the formal sector, which generates income for the underprivileged and acts as a safety net during times of crisis. It is an independent activity with few (if any) connections to the rest of the economy. Additionally, informal operators are barred from contemporary economic prospects because of imbalances between the population growth rates and current industrial employment and a mismatch between people’s skills and the structure of modern economic opportunities (Hart, Citation1973; Sethuraman, Citation1976). This is consistent with a development theory, which emphasizes the dualism of the urban economy in emerging nations, which is divided between a formal and an informal sector. According to the dualists, governments should increase the number of official jobs and offer financial and business development assistance to unregistered companies.

According to the Structuralist school of thought, formal firms’ attempts to lower labor costs and boost competitiveness, their responses to the influence of organized labor, state regulation of the economy (particularly taxes and social legislation), international competition, and the industrialization process are what cause informality (notably, off-shore industries, subcontracting chains, and flexible specialization)(Castells & Portes, Citation1989; Moser, Citation1978). The structuralist school of thought contends that governments should regulate commercial and employment interactions to rectify the uneven connection between “big business” and delegated producers and workers.

Moreover, according to the Legalist school, the informal economy is made up of “plucky” microentrepreneurs who choose to conduct their business clandestinely to avoid the expenses, time, and effort associated with formal registration and who require property rights to transform their assets into legally recognized assets (De Soto, Citation2000; Soto, Citation1989). According to this school of thinking, the self-employed operate informally according to their informal extra-legal norms due to the unfriendly legal system. According to the legalist school, governments should simplify bureaucratic processes to encourage informal businesses to register and extend legal property rights for the assets they hold to maximize their potential for productivity and turn their investments into actual capital (De Soto, Citation2000; Soto, Citation1989). Unlike the Legalist school, the Voluntarist school of thought does not place the burden for the onerous registration processes on informal entrepreneurs who consciously try to circumvent regulations and taxes. The voluntarists contend that to broaden the revenue base and lessen unfair competition by informal businesses, and the government should formally regulate informal businesses.

Theoretically, a blend of factors drives the choice of informality over formality among entrepreneurs in developing countries. The different schools of thought ascribe a blend of causes for the emergence of the informal sector. While the dualists consider it as an autonomous, yet marginal economic activity with a limited link with the formal economy, the structural school views it as an outcome of the nature of capitalism growth. In terms of drivers of informality, the schools of thought suggest factors ranging from skills mismatch to failure of the formal sector to create adequate employment opportunities for the growing population, the intent to avoid and/or reduce transaction costs in the formal sector (e.g., the costs, time, and effort of formal registration) to escaping regulations and taxation, and the hostile business environment in the formal sector to the unequal relationship among business firms in a capitalist economy.

This study is motivated by the gap in the literature, which calls for further empirical investigation on the issue. Some empirical studies focused on the magnitude and causes of the wage differential between the formal and informal sectors using household surveys in some emerging countries (Nguyen et al., Citation2013); (Falco et al., Citation2011); (Bargain & Kwenda, Citation2011, Citation2014). Other studies, for instance, Aguilar and Campuzan (Citation2009),Bonnet et al., Citation2019), and Phuong(Citation2016), examined the role of the informal economy as a means of livelihood in other developing countries. Nevertheless, it is difficult to generalize these results to the Ethiopian context where the informal sector is the most widespread.

A handful of studies have also been carried out in Ethiopia’s informal sector (Fillmon, Citation2011); (Delbiso, Citation2013). Even those studies conducted locally in Ethiopia focused on the controversies on the functioning of the informal sector, with a focus on issues of employment opportunities, opportunities for a development strategy, as well as the drivers and difficulties of involvement in the sector. In particular, there is no detailed investigation regarding the role of the informal sector in improving livelihood and challenges facing the sector in Ethiopia in general and Hawassa city in particular. Unlike the extant studies that used household surveys, this study adds to the pool of knowledge by examining the contribution of the sector to livelihood improvement using the perception of the participants about changes in their livelihood status and the type of livelihood improvement of the participant taking a wide range of informal sector activities in the city.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the study area

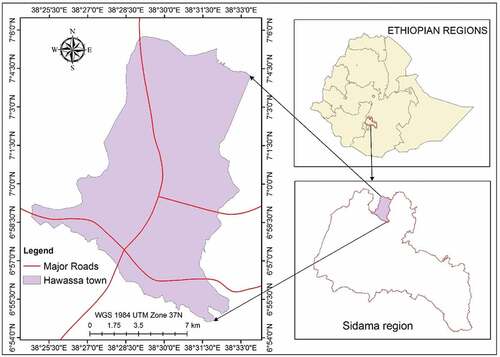

Hawassa is a city in Ethiopia, on the shores of Lake Awassa in the Great Rift Valley. It was established in 1952 when the Sidama people of the Adaare village were displaced to make room for a new settlement by the Haile Selassie government (BoFED, 2018). It is 273 km south of Addis Ababa via Bishoftu, 130 km east of Sodo and 75 km north of Dilla Town, and 1,125 km north of Nairobi, Kenya. The city serves as the capital of the Sidama region. The city lies on the Trans-African High Way-4: an international road that stretched from Cairo (Egypt) to Cape Town (South Africa). The study area is located at Sidama region of Ethiopia, particularly at Hawassa city (Figure ). Geographically the city is bounded by longitudes of 38° 24’ 51” to 38° 33’ 26”E and latitudes of 6° 54’ 42” to 7° 05’ 50”N (Gebere et al., Citation2021).

The city of Hawassa is one of the fast-growing cities in the region, and it has a city administration consisting of 8 sub-cities and 32 kebeles. The sub-cities are named Addis Ketema, Hayk Dar, Bahil Adarash, Misrak, Menahreya, Tabor, Mehal Ketema, and Hawela-Tula. The city administration has an area of 157.2 (sq. km) with a total population of 315,267. Currently, the city is serving as the capital of the Sidama regional state, and the seat of the Southern Nations Nationalities and People Region.

4. Data types and sources

This study employed cross-sectional survey data collected during the month of February, 2–10 March 2020, in selected areas of Hawassa city. To collect the necessary information, the study used primary sources of data. The primary data was collected through a cross-sectional survey from representative respondents among the target population found in the study area. Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected from youth who are engaged in the informal sector during the study period. Following the ILO definition, informal sector operators aged 14–24 were considered in the study.

5. Sampling techniques and sample size determination

The study used multi-stage sampling techniques, which is a combination of purposive, stratification, and simple random sampling methods. In the first stage, among the cities found in Southern Ethiopia, Hawassa city, was selected for the study purposively. Hawassa city was selected as the focus of the study by taking into account the existence of high youth unemployment and various informal enterprises, providing a means of livelihood for a significant portion of the urban labor force and migrants from the surrounding rural areas. In the second stage, using a stratified sampling technique, the eight sub-cities found in the study area were classified into three strata based on informal business activities concentration as low, medium, and high.

In the third stage, a simple random sampling technique was applied to select sub-cities from each stratum based on the high concentration of informal business in the sub-cities. Accordingly, Hayek Dar, Tabor, Menehariya, and Misrak sub-cities were considered. In the fourth stage, out of the twelve kebeles in the selected four sub-cities, eight kebeles (the smallest political and administrative unit in Ethiopia) were selected. While four of them, namely Gudumale, Gebeyadar, Tesso, and Wukro, were selected purposively considering the high concentration of informal businesses in these areas, the remaining four were selected randomly (namely Dume, Fura, Piassay, and Millennium Square) considering the high population movement, recreation centers, and business activities in the selected sub cities. Finally, informal sector participants were selected by a simple random sampling method.

6. Sample size determination

Since there is no fixed number (registered) of target populations for the research, the unknown sample size determination formula that was proposed by Cochran (Citation1977) was used to determine the sample size from the target population.

, where e is the level of precision, which is set at 5%, α is the level of significance, which is set at 5%, and P is the estimated proportion of participant youth in the informal sector. According to the unemployment survey of Hawassa city, among the currently employed youth population in the selected kebeles, about 23% are employed in the informal sector (Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Citation2020). Hence, p = 0.23 is used to calculate the sample size. By substituting the values in the above formula and adding 5% contingency, a sample of 202 informal sector participants were selected. Based on the size and density of the strata, a quota was fixed in order to draw sample in each selected kebeles(see ).

Table 1. Distribution of sample by sub-city and kebele

7. Methods of data collection

A questionnaire was used to collect data from the respondents. Before carrying out the survey, the questionnaire was translated into the local language (Sidaamu Afoo) and pre-tested taking 10% of sample respondents from four sub-cities that were not included in the sample. Following the pretesting of the questionnaire, some wording problem was corrected and gaps were filled before the actual administration of the data collection process. Then, the informal sector participants were personally approached by the researchers. And then data collection was carried out using a questionnaire and the respondent’s interview was conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire.

8. Method of data analysis and model specification

To address the research objectives, we used both descriptive and econometric methods of analysis. The descriptive statistics were used to identify the type of livelihood improvements of the participants, the type of informal business activities, and the challenges of the sector in the study area. The logistic regression model was used to examine the determinants of livelihood improvements of informal sector participants.

The dependent variable is livelihood status, which is based on a self-assessment of whether the participant has perceived improvement in his/her livelihood status due to participation in the informal sector, and it is a binary/dichotomous dummy variable. It takes 1 if the participant perceived that his/her livelihood is improved due to participation in the informal sector business, and 0 otherwise. It elicits participants to reflect on their perceived livelihood improvement following participation in the informal sector activities.

The most commonly used approaches to estimate dummy dependent variable regression models are the logit and the probit models (Damodar, Citation2004). The logit and probit models are comparable, the main difference being that the logistic function has slightly flatter tails i.e., the normal and probit curve approaches the axes more quickly than the logistic curve. The close similarity between the logit and probit models is confined to dichotomous dependent variables. Ignoring this minor difference, the most widely used estimation techniques for a binary analysis are logit and probit, one can easily estimate a logit as well as a probit and we likely get similar estimates of probabilities.

Hosmer et al. (Citation2000) pointed out that a logistic regression model is advantageous over others in the analysis of dichotomous outcome variables in that it is an extremely flexible and easily usable model from a mathematical point of view and results in a meaningful interpretation. Therefore, the binary logit model is employed in this study to examine the factors that affect the likelihood of improvement in the livelihood of informal sector participants.

Based on Damodar, Citation2004 and Hosmer et al. (Citation2000) the functional form of the logistic model is specified as follows:

For ease of exposition, we write (1) as

The probability that a given participant’s livelihood is improved is expressed by (2) while the probability of not improved is

Therefore, we can write

Now, (Pi/1-Pi) is simply the odds ratio in favor of livelihood improvement. The ratio of the probability that a participant will improve livelihood to the probability that it will not.

Finally, taking the natural log of equation (4), we obtain

where Pi is the probability of improved livelihood, which takes either 1 or 0.

Zi = is a function of the explanatory variables (X), which is expressed as

βo is an intercept β1, β2 … … βn are slopes of the equation in the model(see for definition and expected sign of the variables)..

Table 2. Definition and measurements of variables and expected signs

Li is the log of the odds ratio, which is linear in Xi, Xi is a vector of relevant household characteristics, and Ui is the disturbance term. The maximum likelihood method is employed to estimate the parameter estimation of the logit model. The parameter estimates of the logit model give only the direction of the effect of explanatory variables on the dependent variable, but the estimates neither stand for the actual size of change nor the probabilities (Damodar, Citation2004). However, the marginal effect measures the expected change in the probability of a given choice that has been made concerning the unit change in the explanatory variable (Greene, Citation2007). Hence, we used marginal effect results to interpret the results of the study.

9. Diagnostic tests

Before conducting econometric analysis, it is vital to look into the problem of multicollinearity among the continuous explanatory variables and verify the degree of associations among dummy explanatory variables otherwise, the parameter estimate would seriously be affected by the existence of multicollinearity among variables. To this end, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to test the degree of multicollinearity among the continuous variables, and contingency coefficients were used to check for the degree of association among the discrete variables. As a rule of thumb, the VIF of a variable exceeding 10 indicates the existence of multicollinearity among the continuous variables (Damodar, Citation2004). For dummy/discrete variables, according to Damodar, Citation2004, the contingency coefficient is a chi-square-based measure of association, where a value of 0.75 or above indicates a stronger relationship among dummy variables.

The heteroscedasticity problem is a common problem in cross-sectional data. The Breusch–Pagan test is used to test the heteroscedasticity problems of the data in this study (Greene, Citation2012). STATA version 14 Statistical software was used for data analysis.

10. Results and discussion

10.1. Descriptive statistics

This part presented and discussed the results of the analysis on the livelihood of informal sector participants, the type of business activities in the study area, and the challenges of the sector. Out of the 202 questionnaires distributed to respondents, only 182 questionnaires were completed and returned, whereas the remaining 20 questionnaires were not returned and are incomplete. Therefore, this study was analyzed using a sample of 182 informal sector respondents to address the objective of the study.

11. Informal sector activities practiced in the city

The informal sector covers a wide range of activities. Some of the activities include selling clothes and shoes, fruits and vegetables such as banana, mango, lemon, orange, cabbage, spiritual books and pictures, candles, soft drinks, various items such as chewing gum, tissue papers, cigarette, biscuits, selling/recharging air time, artificial pieces of jewelry, cocks, and underwears in kiosks, selling milk (cow), tree seedlings, food processing, small manufacturing of goods, production, maintenance and repair of goods (bicycle, cell phone, tape, battery, and others), small-scale artisans, and a shoeshine. Of these business activities; trade accounted for 40.10%, service for 35.72%, production (16.49%), construction (4.40%), and urban agriculture for only 3.30% (see Table ).

Table 3. Types of informal sector business activities in Hawassa city

12. Status of livelihood improvements of informal sector participants

Among the sample of 182 informal sector participants, about 67% of participants reported that their livelihood is improved due to participation in informal business, whereas 33% of the participants reflected that participation in the informal sector activity has not contributed to livelihood improvement. According to respondents’ responses, this is due that the participants were engaged in the sector with low initial capital, selling low-cost items, do not get training, lacking credit access, experience, and skills and they use their daily income for survival and to support their dependent family. Low initial capital, lack of skills, lack of access to credit, less experience, lack of training, and selling low-cost items are major factors that hinder livelihood improvements of participants in the sector. In addition, participants may be engaged in the sector as transient workers before moving to other jobs (Agadjanian, Citation2002) Furthermore, according to Cohen (Citation2010), street traders begin by selling only a few low-cost items like cigarettes and candies before switching to selling high-profit items such as shoes and clothing. However, the majority of the participants improved their livelihood after participating in the informal business as indicated in Table .

Table 4. Livelihood status of informal sector participants

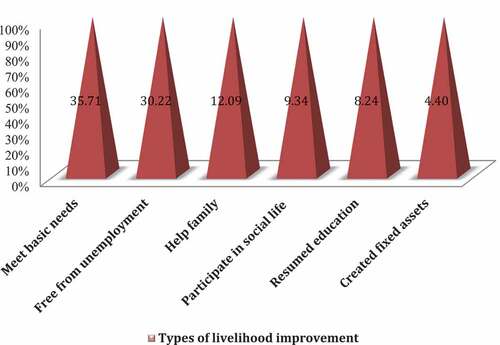

In this connection, 35.71% of the operators have indicated that they have managed to meet their basic needs, and 30.22% of them depicted that they have been relieved from the unemployment problem after they joined the sector. In addition, 12.09% of them reported that the income earned from the activity is used to support their family, 9.34% have started to participate in social life that requires financial contribution, 8.24% have resumed their education, and 4.4% created a permanent asset (see Figure ). In sum, about 7 out of 10 operators have perceived that their livelihood is improved in one way or another after they have joined the sector. This suggests that participation in the informal sector has a positive role in the livelihood improvement of the participants. This finding supports the findings of Timsalina (Citation2011) who finds street vending creates an opportunity for work, employment, and livelihood improvement.

Figure 2. Types of livelihood improvements of the informal sector participants.

Similarly, Fillmon, Citation2011 reported that street vending play important role in improving the participant’s livelihood assets, income welfare, and saving. Delbiso, Citation2013 also indicated that informal sector participation improves the livelihood of the participants and their saving status. Phuong, Citation2016 also documented that informal sector participation contributed to total household income, the improved living condition of households, reduced income inequality, and the probability of escaping from poverty. Furthermore, this agrees with Brown & McGranahan, Citation2016, who noted that the informal sector has positive contributions to informal dwellers.

This demonstrates that engagement in the informal sector activities helps the youth participant to meet their basic need, help their family, participate in different social life affairs, continue their education, hold fixed assets, and make them free from unemployment. Thus, informal sector participation helps the participants to improve their livelihood assets and their welfare income. This result accords with the findings of Fillmon (Citation2011), who find participation in the informal sector has a significant contribution to changing the economic status of the vendors, helps them to continue their education, become self-sufficiency and lead an independent life, able to generate income and having savings in the bank; Phuong, Citation2016 find informal sector participation contribution to total household income, improve the living condition of household, decrease income inequality, and alleviate household poverty. Moreover, Timalsina (Citation2011) also finds that participants get a living with hard work on the street and pursue their education.

13. Challenges of informal sector enterprises

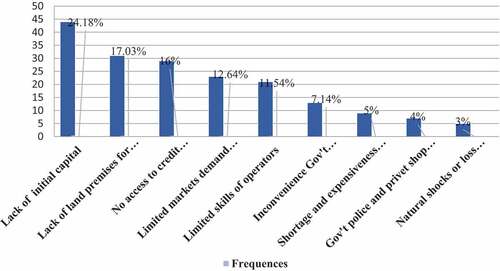

Many informal sector business enterprises face problems that hinder the growth, start-up of the business, employment generation, and livelihood improvement of the participants for a significant number of urban poor and unemployed youth. The major problems of the sector are related to the shortage of capital for start-ups and expansion of the business activity, lack of access to credit facilities from concerned microfinance institutions, lack of provision of land for manufacturing/processing and selling of their products, the limited share of market demand for the product and stiff competition, insufficient technical and managerial skills of the participant to run the business process, shortage of raw material used in the production process and government administrative regulations that are related with the legalization of the enterprise, municipality-related problems, and absence of support and provision of a solution to the sector by the concerned body.

The informal sector business enterprise problems and challenges identified in this study are summarized in Figure depending on the frequency of responses and severity of the problems facing the informal sector enterprises. 24.18% of participants identified lack of initial capital as the major problem hindering business start-ups. This is followed by the absence of land premises used for manufacturing and displaying their products for sale (17.03%), limited access to credit facilities from financial institutions (16%), limited market demand and marketing problems (12.64%), and lack of skills of participants (11.54%). In addition, inconvenient government administrative regulation (7.14%), shortage and expensiveness of raw materials (5%), government policy and private shop guards (4%), and finally natural shocks or loss of commodity by rain or sun risks (3%) are also the other problems faced by the enterprises.

Based on this information, the top five problems facing the informal sector participants that play a role in the process of improving their livelihood in the form of income and employment generation are shortage of capital to start and expand the business, limited access and provision of a land premise for production and marketing of the products, limited access to credit facilitates, limited market demand, and lack of skills. The other problems such as shortage and expensiveness of raw materials, government policies, and natural shocks are also challenges that the sector has been facing in the study area. These results are consistent with the findings of Admasu (Citation2019); (Bargain & Kwenda, Citation2014); (Fillmon, Citation2011); (Delbiso, Citation2013); and Pathways Commission (2018), who find a lack of fixed place, lack of access to capital and credit, lack of customers, lack of equipment and municipality-related problems, lack of skills, lack of adequate access to education, and training are major challenges of the informal sector.

14. Econometric results

Under this section, important variables (demographic, socioeconomic, and institutional) that were hypothesized to contribute to livelihood improvements of the informal sector participants are analyzed by using the logistic regression model.

15. Diagnostic test results

Before applying the logistic regression model, the hypothesized explanatory variables were tested for the existence of multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity problems. Based on the VIF result, the mean value of VIF (1.29) shows that there is no problem of multicollinearity among the continuous explanatory variables in the model.

The contingency coefficient results of the study reveal that there was no serious problem of association among discrete explanatory variables in this study with a maximum degree of association of 0.67, which is less than 0.75. The Breusch–Pagan test result (Prob>chi2 = 0.0018) is significant, which indicates the problem of heteroscedasticity in the model. Thus, to solve this problem, the robust standard error method was used.

16. Determinants of the livelihood improvement of informal sector participants

The results of the logistic regression model and marginal effects are indicated in Table .

Table 5. Maximum likelihood estimation of logit model

The goodness of fit determines the accuracy of the model prediction approximates to the observed data. Wald chi-square test shows the overall goodness of fit of the model at a 1% probability level. Wald chi-square test shows that at least one of the predictors’ regression coefficients is not equal to zero. The Wald chi2 statistics of 47.87 with a chi-square distribution, which is significant at less than 1% probability level, shows at least one of the explanatory variables in the model has a significant effect on livelihood improvement of informal sector participation and that the explanatory variables jointly influence the livelihood of informal sector participant.

As expected, the sex of the participant is negatively related to the perceived improvement of livelihood of informal sector participation significantly at a 5% probability level of significance. The result implies that male youth who are engaged in the informal sector are less likely to improve their lives than their female counterparts. The estimated marginal effect indicates that with other variables being kept constant, female respondents are 18.7% more likely to improve their lives than their male counterparts. This reveals that women are more likely to improve their livelihood than men when they engage in informal business activities. Previous studies also indicated that women tend to be more concentrated than men in informal employment (Chant, Citation2013; Nordman et al., Citation2016; M. Chen, Citation2010). This is because the sector allows women to work fewer hours and combine their income-generating activities with domestic household tasks and take this kind of job as a response to a reduction in household income (Gong et al., Citation2004).

The age of informal sector participants, in line with our expectation, is positively and significantly related to livelihood improvement of informal sector participation at a 5% significance level. This implies that with age, the participants will have better work experience and skills that enable them to improve their livelihoods. The marginal effect results of the model revealed that the likelihood of informal sector participants’ livelihood improvement increases by 1.2% for one additional year in the business. The result is in accord with the findings of Abdullahi et al. (Citation2022), who find an increase in the age of informal sector operators by one more year empowers the youth and helps them to improve their livelihood than the new operators.

Access to credit is found to have a positive and statistically significant effect on the livelihood improvement of informal sector participants at a 1% level of significance. This indicated that youth who got credit access are more likely to be engaged in informal sector activities and improve their lives than those who did not get it. This is because credit access is important to have startup capital for informal sector participation, which leads to livelihood improvement. The marginal effect results of the model indicate that the likelihood of livelihood improvement increases by 48.1% for the youth who had access to credit relative to those who did not have any.

Income obtained from the informal sector is an important variable that affects the probability of livelihood improvement. It has a positive and significant effect on the likelihood of livelihood improvement of informal sector participants at a 1% level of significance. The estimated marginal effect shows that the likelihood of informal sector participants’ livelihood improvement tends to increase by 0.22% for each additional birr earned.1 The result is consistent with the study by Phuong (Citation2016), who find the informal sector as one of the main income sources of total household income, improve the living condition of household, and significantly contributes to reducing income inequality. In this vein, Fillmon, Citation2011 also reported that street vending improves the income or welfare of the participant. Moreover, Brown and McGranahan (Citation2016) also argued that the informal sector has positive contributions to the livelihood of informal dwellers. Likewise, saving was found to have a positive and significant effect on the livelihood improvement of informal sector participants at a 5% significance level. The reported marginal effect indicates that the likelihood of livelihood improvement for the youth who save increases by 23.6% compared to those who did not practice saving. This suggests that income obtained from the informal sector enables them to save more, expand their business and improve the livelihood of participants. This shows that the youth who saved part of their income is more likely to improve their lives than those who did not save. The finding supports the results of Delbiso, Citation2013, who find informal sector participation improves the saving status and livelihood of the participants, and also Fillmon (Citation2011) noted that street vending improves the saving, livelihood assets, and welfare income of the participant.

The initial start-up capital has a positive and significant effect on livelihood improvement at a 5% level of significance. This might be because higher initial capital help to start and expand the business, facilitates engagement in better income-generating activities, and improves the livelihood of the participants. The estimated marginal effect indicates that the likelihood of informal sector participants’ livelihood improvement increases by 0.00741% for each additional birr used for business start-ups. The result is in line with the findings of Bamlaku (Citation2006), who find initial capital plays a role in expanding the business and helps the participants to earn more income, thereby livelihood improvement.

The result of the study indicated that training has a positive and significant effect on the livelihood improvement of youth participants in the informal sector at a 1% level of significance. The marginal effect indicated that the likelihood of livelihood improvement of the youth who got training is greater by 5% relative to those who did not get such an opportunity. This implies that providing business development training to youth participants empowers the youth and helps them in improving their livelihood in the informal sector participation. The result is in line with the findings of Abdullahi et al. (2022), who find training among informal sector operators has a positive and significant influence on the likelihood of youth empowerment and livelihood improvements.

As hypothesized, experience has a positive and significant effect on the livelihood improvement of informal sector participants at a 5% level of significance. This might be because experienced people have a better understanding of the operation of the business and become profitable compared to operators with limited experience. The marginal effect of the model indicated that the likelihood of informal sector participants’ livelihood improvement tends to increase by 5.09% for each additional year of experience in the informal business. This is consistent with the findings of Delbiso et al. (Citation2018), who find operators who stayed longer in the informal business improved their livelihood than new operators and operators who stayed in the sector for more than 1 year have more chance of improving their livelihood compared to those who are new to the sector. Magidi (Citation2022) also finds that the experience and skills acquired from the informal sector play a critical role in empowering the poor, fighting poverty, and building the livelihoods of the participants.

17. Conclusion

This study examines the role of the urban informal sector in improving the livelihoods of participants in Hawassa city, southern Ethiopia. The descriptive analysis results showed that the majority of the respondents (67%) reported that participating in the informal sector has improved their livelihood status. This is due to that the participants started their business with low initial income and they do not have skills, experience, training, credit access, and they are selling low-cost items that provide them with low daily income. However, the majority of the participants improved their livelihood after joining the informal sector. This indicates the critical role played by the informal sector in improving the livelihood of informal sector participants. In the econometric analysis, age, credit access, monthly income, initial capital, saving, training, and experience are found to affect the likelihood of livelihood improvement of the participants positively while sex is found to have a negative effect. The most dominant informal sector business activities where participants are engaged in the study area are trade, service, and production of goods. Besides, construction and urban agriculture are also informal business activities participants are engaged. Therefore, regional government, as well as local government, should work more on the formalization of these sectors or design supportive strategies, which provide mutual benefit for the participants and the government. Moreover, effective institutions and a legal framework are important for ensuring the smooth performance of these informal sector activities in the study area. Notwithstanding the role played by the sector in improving the livelihood of the urban youth, the shortage of start-up capital, lack of access to credit, inadequate technical and managerial skills, lack of working place, shortage of raw materials, limited market demand, and government policies are the major challenges facing informal sector participants. Given tshe role played by the sector in absorbing the urban unemployed labor force and contributing to livelihood improvement, governments, and non-governmental organizations should facilitate enhanced access to finance and business development services for informal enterprises. Designing livelihood skills training programs for youth is very important in improving the skills of youth and preparing the youth to navigate the informal sector and reduce unemployment problems in the study area as well as the country. In addition, regional government and City administrations should arrange a convenient place for informal business activities.

Informal sector participation offers an opportunity to engage in diverse job opportunities and hence contributes to unemployment reduction and income growth. In this context, until the formal sector expands enough to absorb the low-skilled urban unemployed youth, the informal sector shall be seen as a viable instrument for reducing unemployment and improving livelihood in the growing cities of Ethiopia. Furthermore, the creation of job opportunities in the formal sector and improving the business environment shall be among the government’s strategies to reduce the expansion of informal business in the long run. In general, more is needed to support and prepare youth for success in the informal sector.

18. Limitations and the suggestions for future research

This study did not investigate all aspects of informal sector business in the study area. It focused primarily on the contribution of informal sector participation to livelihood improvements of the youth participants, taking street vending in the study area. However, to fully exploit the role of the sector and its potential in securing the livelihood of the poor; other studies may consider a holistic examination of the sector taking evidence from multiple cities, the underlying challenges, and strategies for the formalization of the informal sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tariku Lorato

He is a lecturer of Economics at Dilla University, Ethiopia. He has MA degree in Development Economics. His current research interest area are: industrialization policies, inter-sectorial linkages and structural transformation; firm level growth, innovation, productivity growth and export performance; Public Debt and its economic consequences, Livelihood diversification, food security, informal economy and tax evasions.

References

- Admasu, E., Kenate, W., & Emnet, Y. (2019). Informal sector and its contribution to the livelihood of the urban poor in Hossana town, southern Ethiopia. Jimma University. https://repository.ju.edu.et/handle/123456789/5270

- Agadjanian, V. (2002). Men doing “women’s work”: Masculinity and gender relations among street vendors in Maputo, Mozambique. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 10(3), 329–19. https://doi.org/10.3149/jms.1003.329

- Aguilar, A. G., & Campuzano, E. P. 2009. International Encyclopedia of Human Geography.

- Asmamaw, E. (2010). Some controversies on informal sector operation in Ethiopia: Problems and prospects for development strategies in Addis Ababa. Semantic scholar.

- Asmamaw, E. (2014). Major challenges of informal sector operation in Ethiopia: Harms and prospects for development strategies. Semantic scholar.

- Avirgan, T., Gammage, S., Bivens, J., Jobs, G., & Jobs, B. (No). Jobs : Labor Markets and Informal Work in Egypt, El Salvador, India, Russia, and South Africa, Economic Policy Institute. ( CID: 20.500.12592/32dq1j).

- Bamlaku, A. (2006). Micro financing and poverty reduction in Ethiopia: A paper prepared under the Internship Program of IDRC. ESARO, Nairobi.

- Bargain, O., & Kwenda, P. (2011). Earnings structures, informal employment, and self‐employment: new evidence from Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa. Review of Income and Wealth, 57, S100–S122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2011.00454.x

- Bargain, O., & Kwenda, P. (2014). The informal sector wage gap: New evidence using quantile estimations on panel data. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 63(1), 117–153. https://doi.org/10.1086/677908

- Benjamin, N., Beegle, K., Recanatini, F., & Santini, M. (2014). Informal economy and the world bank. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper(6888). World Bank.

- Bonnet, F., Vanek, J., & Alter Chen, M. (2019). Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Brief. WIEGO and ILO. https://www.wiego.org/publications/women-and-men-informal-economy-statistical-brief

- Brown, D., & McGranahan, G. (2016). The urban informal economy, local inclusion and achieving a global green transformation. Habitat International, 53, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.002

- Buba, A., Dayananda Somasundara, J. W., Adamu, I., & Samuel, D. (2022). Vocational Training and YouthEmpowerment in Nigeria: Evidence from Informal Sector Operators’ Activity in Gombe Metropolis. American Journal of Social Sciencesand Humanities, 7(2), 144–153.

- Bureau of Finance and Economic Development. (2018). GIS department. Hawassa.(unpublished).

- Castells, M., & Portes, A. (1989). World underneath: The origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy. The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries, 12. https://www.wiego.org/publications/world-underneath-origins-dynamics-and-effects-informal-economy

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA). (2004) Report on urban informal sector sample survey 2003, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA). (2020) Report on urban informal sector sample survey 2019, Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa.

- Chant, S. (2013). Cities through a “gender lens”: A golden “urban age” for women in the global South? Environment and Urbanization, 25(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813477809

- Chen, M. (2010). Informality, poverty, and gender: Evidence from the global south. In Sylvia, C. (Ed.), The international handbook of gender and poverty (pp. 1–736). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Chen, M. A. (2012). The Informal Economy: Definitions, Theories and Policies. Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Working Paper No. 1. Cambridge, USA.

- Chidoko, C., & Makuyana, G. (2012). The contribution of the informal sector to poverty alleviation in Zimbabwe. Developing Countries Studies, 2(9), 41–44. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234680859.pdf

- Cochran, W. G. (1977). Sampling techniques: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen, J. (2010). 'How the global economic crisis reaches marginalised workers: The case of street traders in Johannesburg, South Africa'. Gender & Development, 18(2), 277–289.

- Damodar, N. (2004). Basic econometrics: Student solutions manual for use with basic econometrics.-4th. McGraw-Hill.

- Darbi, W. P. K., & Knott, P. (2016). Strategising practices in an informal economy setting: A case of strategic networking. European Management Journal, 34(4), 400–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2015.12.009

- Delbiso, T. D. (2013). The role of informal sector in alleviating youth unemployment in Hawassa City, Ethiopia. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 59th World Statistics Congress of the International Statistical Institute. The Hague. International Statistical Institute.

- Delbiso, T. D., Deresse, F. N., Tadesse, A. A., Kidane, B. B., & Calfat, G. G. (2018). Informal sector and urban unemployment: Small businesses contribution to large livelihood improvements. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 34(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2018.092025

- De Soto, H. (2000). The mystery of capital: Why capitalism triumphs in the west and fails everywhere else. Basic books.

- Doğrul, H. G. (2012). Determinants of formal and informal sector employment in the urban areas of Turkey. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanity Studies, 4(2), 217–231. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/257277

- Elgin, C., & Oyvat, C. (2013). Lurking in the cities: Urbanization and the informal economy. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 27, 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2013.06.003

- Falco, P., Kerr, A., Rankin, N., Sandefur, J., & Teal, F. (2011). The returns to formality and informality in urban Africa. Labour Economics, 18, S23–S31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2011.09.002

- Fillmon, T. K. (2011). The role of informal sector on household livelihood: Survey of street vendors in Mekelle City. Mekelle University.

- Gebere, Y. F., Bimerew, L. G., Malko, W. A., Fenta, D. A., & Spradley, F. T. (2021). Hematological and CD4+ T-cell count reference interval for pregnant women attending antenatal care at Hawassa University comprehensive specialized hospital, Hawassa Southern Ethiopia. PloS one, 16(4), e0249185. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249185

- Gong, X., Van Soest, A., & Villagomez, E. (2004). Mobility in the urban labor market: A panel data analysis for Mexico. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1086/423251

- Green, W. H. (2007). Econometric Analysis (6th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Greene, W. (2012). H. (2012): Econometric analysis. Journal of Boston: Pearson Education, 803–806. https://spu.fem.uniag.sk/cvicenia/ksov/obtulovic/Mana%C5%BE.%20%C5%A1tatistika%20a%20ekonometria/EconometricsGREENE.pdf

- Harris, J. R., & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment and development-2-sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60(1), 126–142. https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:aea:aecrev:v:60:y:1970:i:1:p:126-42

- Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00008089

- Hosmer, D. W., Lemeshow, S., & Cook, E. (2000). Applied logistic regression 2nd edition. Jhon Wiley and Sons Inc.

- ILO, (2015). Growing out of Poverty: How Employment Promotion Improves the Lives of the Urban Poor. SEED Working Paper No. 74, ILO.

- ILO (2021). Conceptual framework for statistics on informal economy. Department of Statistics, Working Group for the Revision of the standards for statistics on informality. Draft under construction for discussion at the third meeting of the Working Group.

- International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). (2016). Informal and inclusive green growth: Evidence from “the biggest private sector”

- International Labor Organization. (2018). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture (third ed.). International Labour Office.

- La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2014). Informality and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.3.109

- Magidi, M. (2022). The role of the informal economy in promoting urban sustainability: Evidence from a small Zimbabwean town. Development Southern Africa, 39(2), 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2021.1925088

- Meghir, C., Narita, R., & Robin, J.-M. (2015). Wages and informality in developing countries. American Economic Review, 105(4), 1509–1546. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20121110

- Mengistu, T., & Jibat, N. (2015). Street vending as the safety-net for the disadvantaged people: The case of Jimma Town. International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, 7(5), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJSA2015.0601

- Moser, C. O. (1978). Informal sector or petty commodity production: Dualism or dependence in urban development? World Development, 6(9–10), 1041–1064. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(78)90062-1

- Nguyen, H. C., Nordman, C. J., & Roubaud, F. (2013). Who suffers the penalty?: A panel data analysis of earnings gaps in Vietnam. Journal of Development Studies, 49(12), 1694–1710. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.822069

- Nordman, C. J., Rakotomanana, F., & Roubaud, F. (2016). Informal versus formal: A panel data analysis of earnings gaps in Madagascar. World Development, 86, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.05.006

- Phuong, N. T. B. (2016). Role of informal sector in improving living standards of rural households in Hanoi, Vietnam. Park Chung Hee School of Policy and Saemaul of Yeungnam University. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4097.7686

- Phuong, N. T. B. (2016). Role of Informal Sector in Improving Living Standards of Rural Households in Hanoi, Vietnam. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.4097.7686

- Reddy, M., Naidu, V., & Mohanty, M. (2003). The urban informal sector in Fiji results from a survey. Fijian Studies: A Journal of Contemporary Fiji, 1(1), 127–154. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Urban-Informal-Sector-in-Fiji-Results-from-a-Reddy-Naidu/a93ee911049da7a280c4ed8382795009682d2667

- Satterthwaite, D., & Mitlin, D. (2013). Reducing urban poverty in the global south. Routledge.

- Schneider, F., & Enste, D. H. (2013). The shadow economy:An international survey. Cambridge University Press.

- Sethuraman, S. V. (1976). The urban informal sector: Concept, measurement and policy. International Labour Review, 114, 69. https://www.wiego.org/publications/urban-informal-sector-concept-measurement-and-policyinternational-labour-review

- Soto, H. (1989). The other path: The economic answer to terrorism. HarperCollins.

- Sutter, C., Bruton, G. D., & Chen, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.06.003

- Timalsina, K. P. (2011). An urban informal economy: Livelihood opportunity to poor or challenges for urban governance, study of street vending activities of Kathmandu Metropolitan City. International Journal of Politics and Good Governance, 2(2.2), 1–13. https://www.academia.edu/1914982/An_Urban_Informal_Economy_Livelihood_Opportunity_to_Poor_or_Challenges_for_Urban_Governance

- Vanek, J., Chen, M. A., Carré, F., Heintz, J., & Hussmanns, R. (2014). Statistics on the informal economy: Definitions, regional estimates and challenges. Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Working Paper (Statistics), 2(1), 47–59. https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/publications/files/Vanek-Statistics-WIEGO-WP2.pdf

- World Customs Organization. (2015). Developing policies with respect to informal trade.