?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the impact of public investment on private investment in South Africa using the autoregressive distributed-lag (ARDL) and nonlinear ARDL bounds testing approach for the period from 1980 to 2018. The ARDL results show that public investment crowds in private investment in the long and short run. The NARDL results indicate that the negative shock in public investment leads to a decrease in private investment in the long and short run. The results show that public investment has an asymmetric impact on private investment in South Africa. The study recommends that government increase investment in infrastructure such as energy, roads and railways, among others, in order to promote private investment.

1. Introduction

Public investment is a determinant of private investment, and it can crowd in or crowd- out private investment (see, Ghali, Citation1998; Dash, Citation2016). Crowding-in effect implies that government spending encourages private investment, while crowding-out effect means that government spending reduces private investment in the economy. The Classical economists believed that public investment crowds out private investment while the Keynesians claimed that public investment crowds in private investment because of the multiplier effect (see Saeed et al., Citation2006). It is believed that public investment promotes private investment, especially when the investment is on infrastructure development(Nguyen & Trinh, Citation2018:17). Studies such as Pereira (Citation2001) and Erden and Holcombe (Citation2005) and Akber et al. (Citation2020) found that public investment crowds in private investment while Acosta and Loza (Citation2005), Bint-E-Ajaz and Ellahi (Citation2012) and Dash (Citation2016) found that public investment crowds out private investment. The empirical studies show that the impact of public investment on private investment is mixed and inconclusive. In addition, the majority of the previous studies have explored only the linear relationship between public and private investment. Recently, it has been found that public investment has asymmetric impact on private investment (see Akber et al., Citation2020).

South Africa has developed policies over the years with the aim of promoting investment, inclusive of private investment and achieving higher economic growth. Since investment is needed for development, the government needs to spend more on capital expenditure. It has been found that public sector investment could help crowd in private investment. Investment spending in South Africa decreased to around 16% of GDP by the early 2000s, compared to just about 30% of GDP in the early 1980s (Presidency of South Africa, Citation2012). Through the National Development Plan (NDP), the government intends to increase the gross-fixed capital formation to 30% and increase government sector investment to 10% by 2030 (Presidency of South Africa, Citation2012). Therefore, it is important to examine the impact of public investment on private investment, as it will assist policymakers with policy formulation.

Although a number of studies have been conducted on the dynamics of investment using data from different countries (see Bouakez et al., Citation2017; Afonso & St Aubyn, Citation2019; Maluleke et al., Citation2023), very few studies have fully explored the crowding in or out of public investment on private investment. As there is no accord regarding the effects of public investment on private investment, it is against this backdrop that the current study attempts to re-investigate the long and short-run effect of public investment on private investment in South Africa by using both the autoregressive distributive lag (ARDL) and nonlinear autoregressive distributive lag (NARDL) approach. The study will examine the impact of the positive and negative shocks in public investment on private investment. The study will be among the first to determine how the asymmetry in public investment affects private investment in South Africa. The hypothesis of whether public investment promotes or dampens private investment is tested. The objective of the study is to explore whether public investment has a symmetric or asymmetric impact on private investment in South Africa.

The rest of the study is organised as follows: Section 2 presents the overview of private and public investment in South Africa. Section 3 discusses the literature review on the impact of public investment on private investment. Section 4 presents the methodology used in the study, while Section 5 presents the empirical findings of both the ARDL and NARDL. Lastly, Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Overview of private and public investment in South Africa

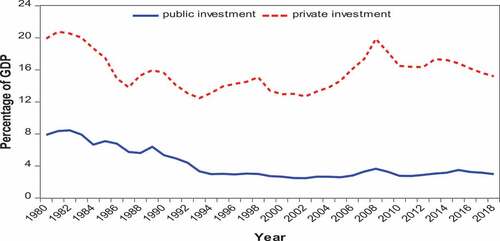

The South African government has developed a number of policies since the 1980s. Some of the policies that have been implemented include, among others, the restructuring of State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR), and the Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative for South Africa (AsgiSA). In South Africa, public investment as a percentage of GDP has been lower than private investment as a percentage of GDP, and it averaged 4.2 percent, while private investment averaged 15.8 percent from 1980 to 2018 (see Figure ). This could be due to the government creating a conducive environment for the private sector by implementing strategic policies. Figure presents public investment and private investment as a percentage of GDP in South Africa from 1980 to 2018.

Figure 1. Public Investment and Private Investment in South Africa (1980–2018).

As shown in Figure , in 1980, public investment as a ratio of GDP was 7.9 percent before increasing to 8.4 percent in 1981. In 1983, the public investment decreased to 7.9 percent before reaching 5.6 percent in 1998, which was the lowest percentage in the 1980s. In 1990, public investment as a percentage of GDP continued to decline to 5.3 percent, then to 3 percent in 1994. Real capital expenditure by the government declined in 1995 from 3.02 percent to 2.95 percent in 1996, indicating that the creation of physical infrastructure in the recovery has lagged behind the creation of private sector productive capacity (National Treasury, Citation1996).

For the 2000 to 2018 period, public investment as a percentage of GDP averaged just 3 percent, while private investment as a percentage of GDP averaged 15.8 percent. In 2000, public investment was 2.7 percent, and in 2001, the percentage went down to 2.5 percent before it started to increase to 3.3 percent in 2007 and reached 3.7 percent in 2008 (World Bank, Citation2021). The government has, in partnership with the private sector, invested in the expansion of the economic infrastructure. The investment by the government in economic infrastructure was found to crowd in private sector investment (National Treasury, Citation2008). Public investment continued to fluctuate in the 2000s and reached 3 percent in 2018 (see Figure ).

3. Literature review

The Keynesians assume that there is underemployment in the economy, while the neo-classicals assume that there is full employment. The Keynesians suggest that under the expansionary fiscal policy in which there is a tax cut and an increase in government spending, the output level of the economy will increase (Şen & Kaya, Citation2014). Keynes suggested that fiscal expansionary policy had the tendency to increase the private sector market through the fiscal multiplier (Omojolaibi et al., Citation2016). Therefore, this means that there is a crowding in of private investment in the economy (Kuştepeli, Citation2005; Şen & Kaya, Citation2014).

The Neoclassical economists believe that through expansionary fiscal policy, the government will borrow funds to finance its expenditure, which will cause interest rates to increase, and there will be less funds available for the private sector consumption and investment (Sineviciene & Vasiliauskaite, Citation2012). When government expenditure increases, interest rates will have to increase , which will lead to a reduction in private investment (see Kuştepeli, Citation2005). Therefore, government spending will crowd out private investment.

The relationship between public and private investment has received considerable attention in the literature. However, there have been inconsistent conclusions because some studies conclude that public investment crowds in private investment while others found the crowding out effects. In Pakistan, using data from 1964 to 2001, Hyder (Citation2001) examined the crowding out hypothesis and found that there is a complementary relationship between public and private investment, suggesting that an increase in public investment will lead to an increase in private investment. Using a panel of 14 OECD countries for the period 1979 to 1988, Argimón et al. (Citation1997) examined the relationship between government spending and private investment. They found that public investment crowds in private investment. Pereira (Citation2001) examined the effects of public investment on private investment in the United States and found that aggregate public investment crowds in private investment.

Using data from 1964–65 to 2004–05, Rashid (Citation2005) found that there is a positive relationship between public and private investment in the long run in Pakistan. Kuştepeli (Citation2005), while using data from 1967 to 2003 to analyse the effectiveness of fiscal spending in Turkey, found that government spending crowds in private investment. Akber et al. (Citation2020) examined the crowding effects of public investment on private investment in India using the data from 1970 to 2016 and the NARDL methodology. The study found that in the long and short run, public investment crowds in private investment. In a study of 19 developing countries, Erden and Holcombe (Citation2005) examined whether public investment crowds in or out private investment using data from 1980 to 1997. The study found that public investment complements private investment. Using the ARDL methodology for the Gambia, Ayeni (Citation2020) examined the determinants of private investment using data from 1980 to 2019. The study found that government investment has a positive impact on private investment in the long and short run. Abdulkarim and Saidatulakmal (Citation2021) examined the effects of fiscal policy on private investment in Nigeria using the ARDL methodology and data from 1980 to 2017 and found that capital expenditure stimulated private investment. Shankar and Trivedi (Citation2021) examined the crowding in or out of public investment on private investment in India using the ARDL approach for the period 1981 to 2019. The findings of the study indicate that at the aggregate level, there is support for complementarity between private and public investment in the long and short run. Ouédraogo et al. (Citation2019) investigated the crowding-in or crowding-out effect of public investment on private investment in 44 sub-Saharan African countries for the period from 1960 to 2015 and found that, on average, public investment crowds in private investment in sub-Saharan Africa. Marcos and Vale (Citation2022) examined the relationship between public investment and private investment in a sample of 21 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries for the period between 2000 and 2019. The study found support for a crowding-in effect of public investment on private investment.

In Turkey, Karagöl (Citation2004) disaggregated government expenditures into government consumption and public investment and examined the crowding impact on private investment for the period 1968 to 2000. The study found that public investment and government consumption crowd out private investment. Also, in Turkey, using data from 1980 to 2005, Başar and Temurlenk (Citation2007) investigated the crowding-out effect of government spending on private sector investment and found that government spending has a crowding-out effect on private investment. In another study for Turkey, Akçay and Karasoy (Citation2020) examined the determinants of private investment for the period 1975 to 2014 using ARDL and found that public investment has a negative impact on private investment.

In a study on Pakistan using data from 1970 to 2010, Saghir and Khan (Citation2012) found that public investment crowd out private investment. Using data from 1969 to 2005 in India, Mitra (Citation2006) investigated whether government investment has crowded out private investment and found that government investment crowds out private investment. Ahsan Abbas and Ahmed (Citation2019) empirically explored the relationship among private domestic, foreign direct and public investments in Pakistan from 1960 to 2015 using the simultaneous equations and Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) frameworks. The study found that public investment crowds out private investment. Mohanty (Citation2019) examined the impact of fiscal deficit and its financing pattern on private corporate sector investment in India from 1970/71 to 2012/13. Using the ARDL estimation technique, the study found that fiscal deficit crowds out private investment both in the long run and in the short run. In Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi, Mose et al. (Citation2020) examined the macroeconomic determinants of domestic private investment for the period 2009 to 2018. They found that public investment has a negative and significant effect on private investment. Using the ARDL method and data from 1975 to 2018, Bedhiye and Singh (Citation2022) found that government capital and recurrent expenditure have a crowding-out effect on private investment in Ethiopia.

In Brazil, from 1947 to 1990, Cruz and Teixeira (Citation1999) analysed the impact of public investment on private investment. Their study found that public investment crowds out private investment in the short run, while in the long run, the two variables complement each other. In Vietnam, Nguyen and Trinh (Citation2018) examined the impact of public investment on economic growth and private investment using the ARDL model from 1990 to 2016. The findings indicate that in the short run, public investment has a crowding-in effect on private investment but a crowding-out effect in the long run.

Using data from 1970 to 2013 in India, Dash (Citation2016)) found that public investment crowds out private investment in the long and short run, while public infrastructure, indicated by the kilometres of road per capita, crowds in private investment in the short run. In another study for India, Bahal et al. (Citation2018) examined the relationship between public and private investment. The study found that although public investment crowds out private investment in India over the period 1950 to 2012, the opposite is found when the sample is restricted to post-1980. In South Africa, few studies have examined the impact of public investment on private investment. Using ARDL and data from 1970 to 2017 for South Africa, Makuyana and Odhiambo (Citation2018) found that gross public investment crowds out private investment while infrastructural public investment crowds in private investment in the long run. In the short run, gross public investment and non-infrastructural public investment crowd out private investment. In Malawi, Makuyana and Odhiambo (Citation2019) found that in the short run, gross public investment has a crowding-out effect. When it is disaggregated into infrastructural and non-infrastructural public investment, it is revealed that infrastructural public investment crowds in private investment in the long run, while it crowds out in the short run. The non-infrastructural public investment is found to have no effect on private investment in the long and short run. Ngeendepi and Phiri (Citation2021) examined the crowding-in or out effect of foreign direct investment and government expenditure on private domestic investment for 15 Southern African Development Community member states. The findings revealed that government spending crowds in domestic investment in the short run and crowds out domestic investment in the long run. Babu et al. (Citation2022) explored the relationship between public infrastructure investment and private investment for five East African Community partner states. The results of the study indicate that in the short run, public infrastructure investment crowds out private investment while there is a crowding-in effect in the long run. Nguyen (Citation2022) investigated the effects of public debt, governance, and their interactions with private investment for a sample of 98 developing countries from 2002 to 2019. The study found that public debt crowds out private investment while governance stimulates it.

Based on the literature reviewed in this section, it is clear that the majority of the previous studies focused mainly on Asian countries. Very few studies focused on African countries in general and South Africa in particular. Moreover, most of the studies that focused on African countries mainly used the ARDL approach. The study, therefore, aims to fill this gap by examining the symmetric and asymmetric impact of public investment on private investment in South Africa using ARDL and NARDL techniques.

4. Methodology

The model used in this study is based on the flexible accelerator theory, which assumes that the desired capital stock is proportional to output. The flexible accelerator theory function is expressed as follows:

Where, is the desired capital stock in period

and

is the level of expected output in period

.

The gross fixed capital investment of the private sector is expressed as follows (Mutenyo et al., Citation2010):

Or

Where is the desired level of gross private investment,

is the actual level of private investment, and

is the coefficient of adjustment where

Gross investment is given byFootnote1:

Where, is the depreciation rate of the capital stock.

Since then

Equation 4 can be simplified as:

Introducing the lag operator:

Where is the lag operator, and is stated as

;

Combining equations 2 and 7 gives:

Using the definition,

If from equation 1 is substituted into equation 9, the desired level of investment is written as:

Therefore, equation 11 can be used to model private investment as a function of output and other variables. Following Akber et al. (Citation2020), the model to examine the impact of public investment on private investment is specified as follows:

Where: - private investment;

- economic growth;

- public investment;

- credit to the private sector;

- real interest rate;

- inflation rate;

- trade openness.

The dependent variable is domestic private investment, which is measured by the private sector’s gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP. The model includes public investment, which is measured by government gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP as well as other determinants of private investment to examine the crowding effects of public investment on private investment. Public investment may crowd in private investment, especially when government invests in infrastructure. However, it can also crowd out private investment, especially when government invests in goods that are in competition with the private sector (Green & Villanueva, 1991). Some studies, such as those of Odedokun (Citation1997), Pereira (Citation2001) and Ramirez and Nazmi (Citation2003), found that public investment crowds in private investment, while Karagöl (Citation2004), Acosta and Loza (Citation2005), Mitra (Citation2006), Bint-E-Ajaz and Ellahi (Citation2012), and Dash (Citation2016) found that it crowds out private investment. Therefore, public investment is expected to have a positive or negative impact on private investment.

The study makes use of real GDP per capita as a proxy of economic growth. Some studies, such as Tan and Tang Citation(2012) , found that economic growth has a positive impact on private investment. Therefore, the coefficient of economic growth is expected to be positive. Credit to the private sector is proxied by domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP and has been found to influence the level of private investment. Oshikoya (Citation1994) found that access to credit by the private sector has increased the investment level. Therefore, the study expects the coefficient to be positive.

The real interest rate is proxied by the lending rate adjusted for inflation. The real interest rate is used as a proxy for the user cost of capital. Studies such as Greene and Villanueva (Citation1991) found an inverse relationship between private investment and interest rate, while Frimpong and Marbuah (Citation2010) found support for the complementary hypothesis. Therefore, the real interest rate is expected to have a positive or a negative effect on private investment. Inflation is measured by the consumer price index (CPI), and it is used as a proxy for uncertainty in the economy. Studies, such as Greene and Villanueva (Citation1991), found that private investment has a negative relationship with inflation, while Acosta and Loza (Citation2005) and Haroon and Nasr (Citation2011) found that the impact of inflation on private investment is positive. Therefore, the coefficient of inflation is expected to be positive or negative.

Trade openness is measured by the ratio of exports and imports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP. The reduction or elimination of tariffs can boost investment as it will be easier to import and export goods and services. Studies such as Naa-Idar et al. (Citation2012) and Ajide and Lawanson (Citation2012) have found that trade openness has a positive impact on private investment. Therefore, trade openness is expected to have a positive impact on private investment.

The study uses annual time series data for the analysis. The data covers the period from 1980 to 2018. The data for variables included in the study are obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI). The selection of the study period was based on the availability of reliable and complete data on the variables of interest for the study country.

4.1. Linear and nonlinear ARDL modelling

This study uses both the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) (Model 1) and the nonlinear ARDL (Model 2) bounds testing approaches to examine the crowding in or out effects of public investment on private investment. The ARDL approach is chosen because it has some empirical advantages over other cointegration techniques. Some of the advantages include that it does not need all the variables under study to be integrated of the same order, meaning they can be either I(0) or I(1). However, in some cases, the relationship between the economic variables might not be linear, which means that there could be an asymmetric or nonlinear relationship between the variables. Therefore, the NARDL approach by Shin et al. (Citation2014) is also used to analyse both short- and long-run asymmetric relationships between public investment and private investment. The NARDL model aims to capture both the short- and long-run asymmetries in the variables included in the study while reserving all merits of the ARDL approach (Cheah et al., Citation2017). In this model, public investment is decomposed into negative and positive partial sums. The positive partial sum series captures the increase of the explanatory variable, while the negative partial sum series reflects the decrease of the explanatory variable (Pal & Mitra, Citation2016). Therefore, the equation for the asymmetric cointegration model is stated as follows:

In order to examine whether public investment has an asymmetry impact on private investment, public investment is decomposed into positive and negative changes. In equation 13, positive shock in public investment is measured by and negative shock by

. The positive and negative shocks are obtained as follows:

Therefore, the ARDL and NARDL models are expressed as follows:

Model 1: ARDL

Model 2: NARDL

Where: to

are the long-run parameters and

to

are the short-run parameters, while

is the error term which is assumed to be normally distributed. Similar to the ARDL approach, the computed F-statistic is compared to the upper and lower critical values by Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) to confirm the asymmetrical cointegration in the long run. The null and alternative hypothesis to test cointegration is expressed as follows:

Model 1: ARDL

Model 2: NARDL

The rejection of the null hypothesis will confirm the asymmetric long-run association between public investment and private investment. After establishing cointegration, the next step of the ARDL approach is to estimate an error correction model. The error correction representation of the models is specified as follows:

Model 1: ARDL

Model 2: NARDL

Where is the error correction term, which indicates the speed of adjustment back to long-run equilibrium. The coefficient of the lagged error correction term is expected to be negative and statistically significant to further confirm the existence of a cointegration relationship.

5. Empirical findings

All the variables employed in the study are first tested for stationarity before empirical analysis. This is to ensure that all the variables are integrated of order one or lower. The study utilises the Dickey-Fuller Generalised Least Squares (DF-GLS) and Phillips-Perron (PP) stationarity tests. The study also used the Zivot and Andrews (Citation1992) unit root test, which is used to test for structural breaks in the data. All variables in the study are found to be integrated of I(1) except for INT which is found to be I(0) when using the Phillips-Perron test. The results of the stationarity tests for all the variables in levels and the first difference are presented in Table .

Table 1. Stationarity Test for all Variables

The Brock-Dechert-Scheinkman (BDS) test developed by Brock et al. (Citation1996) has been used to check the non-linearity in the variables included in the study. The results indicate the nonlinearity of the variables, and this is confirmed by the significance of the BDS test at the 1% level of significance. The results of the BDS test are presented in Table . After confirming the nonlinearity in the variables, the next step is to perform the NARDL model.

Table 2. BDS Test for Nonlinearity

The results from the bounds test for the ARDL and NARDL model confirm the existence of a long-run linear and nonlinear relationship between private investment and public investment. For the ARDL model, the F-statistic is 6.981, and 4.120 for the NARDL. The F-statistic is higher than the upper-bound asymptotic critical values, as shown in Table . Therefore, the null hypothesis of no cointegration among the variables is rejected. The results of the cointegration test are reported in Table .

Table 3. Bounds F-test for Cointegration Results

After confirming that private investment and the explanatory variables are cointegrated, the study proceeds to estimate the long- and short-run coefficients. The long- and short-run results are presented in Table .

Table 4. Results of Long-Run and Short-Run Estimation

5.1. Linear ARDL results

For the ARDL model, the results show that public investment has a positive effect on private investment in the long and short run. This means that an increase in public investment will lead to an increase in private investment. This suggests that public investment crowds in private investment in South Africa in the long and short run. The results are in accord with Argimón et al. (Citation1997), Pereira (Citation2001) and Kuştepeli (Citation2005).

Other results for the ARDL model show that economic growth has a positive impact on private investment and is statistically significant in the long and short run. This means that an increase in economic growth will lead to an increase in the level of private investment. Furthermore, the coefficient of credit to the private sector is positive and statistically significant in the long run. This suggests that an increase in the credit available to the private sector will lead to an increase in the level of private investment. In the short run, credit to the private sector is found to be negative and statistically insignificant. The coefficient of trade openness is negative and statistically significant in the long run, while it is positive in the short run. The increase in the openness of the economy will lead to an increase in the short run, while it will lead to a decrease in private investment in the long run. Trade openness from the previous period is found to have a positive and statistically significant impact on private investment in the short run. Inflation has a negative impact on private investment and is statistically significant in the short run. This means that an increase in inflation will lead to a decrease in private investment.

5.2. Nonlinear ARDL results

The nonlinear long-run results indicate that the coefficient of the positive shocks in public investment is negative, and for the negative shocks in public investment, it is positive. The coefficient of the positive shocks is statistically insignificant, while for the negative shocks, it is statistically significant. This means that the negative shock in public investment will lead to a decrease in private investment.

In the short run, negative shock in public investment is found to be statistically significant at the 1% level of significance, while the positive shock is found to be statistically insignificant. The findings suggest that the negative shock in public investment leads to a decrease in private investment in the short run. The positive shock in public investment from the previous period is found to lead to an increase in private investment.

The other variables in the long run for the NARDL model show that economic growth has a negative and statistically significant impact on private investment in the long and short run. This means that an increase in economic growth will lead to a decrease in private investment. In the long run, the coefficient of the credit to the private sector is found to be positive and statistically significant. This means that an increase in the availability of credit to the private sector will lead to an increase in private investment. In the short run, inflation has a negative and statistically significant impact on private investment, which means that an increase in the inflation rate will lead to a decrease in private investment. The coefficient from the previous period for credit to the private sector and inflation are found to be negative and have a statistically significant impact on private investment in the short run. Furthermore, interest rate has a positive and statistically significant impact on private investment. This means that when interest rate increase, the level of private investment will also increase in the short run. Trade openness is found to have a statistically insignificant impact on private investment.

The results show that the R-square is 0.881 for the ARDL model and 0.897 for the NARDL model, implying that 88% and 90% of the variation in private investment is explained by the independent variables. As expected, the coefficient of the ECM is negative and statistically significant at the 1% level of significance. The findings of the study indicates that the coefficient of the ECM for the linear ARDL is 0.642, while for nonlinear ARDL, it is 0.743.

The Wald test is used to determine whether there is an asymmetric or symmetric relationship between public investment and private investment. . The results from Wald test confirm the presence of an asymmetric relationship between public investment and private investment in the long and short run. The empirical findings of the study confirm that public investment asymmetrically influences private investment in South Africa. The Wald test results are presented in Table .

Table 5. Long- and Short-Run Asymmetry Results

5.3. Diagnostic test results

The diagnostic tests were carried out for the ARDL and the NARDL model. The tests are serial correlation using the Breusch-Godfrey langrage multiplier test, heteroscedasticity using the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey test, normality using the Jarque-Bera test and functional form using the RESET test. The diagnostic checks have revealed the suitability of the model. The results reveal that the model is correctly specified and there is no evidence of serial correlation and heteroscedasticity. The residuals are also confirmed to be normally distributed. The Reset test also shows that the model is well-specified. Table summarizes the results of the diagnostic tests for the ARDL and NARDL.

Table 6. Diagnostic Tests Results

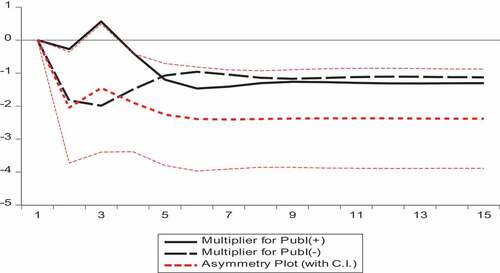

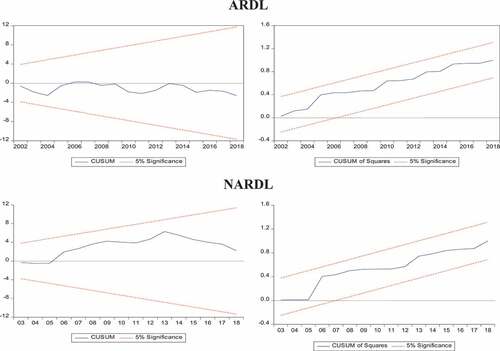

The dynamic multiplier graph is used to check the asymmetry that is due to the positive and negative shocks of the variable. The solid black line in Figure shows the adjustment of private investment to a positive shock in public investment, while the dotted black line shows the adjustment of private investment to a negative shock. The asymmetric line, which indicates the difference between the positive and negative shocks in public investment, is represented by the red dotted line. The cumulative sum of recursive residuals (CUSUM) and cumulative sum of squares of recursive residuals (CUSUMQ) plots indicate evidence of stability in the model as the plots are within the confidence band at a 5% significance level. This shows that both the linear and nonlinear models used in this study are stable. The plot of the dynamic multiplier graph is presented in Figure , while the CUSUM and CUSUMQ plots for the models are shown in Figure .

6. Conclusion

The study examined the crowding-in or -out effects of public investment on private investment in South Africa using data from 1980 to 2018. Although a number of studies have been conducted on the relationship between private and public investment in South Africa, only a few studies have examined the crowding effects of public investment on private investment using the NARDL approach. Moreover, based on the results of the previous studies, there is no consensus on the crowding in or out of private investment by public investment. To our knowledge, this may be the first study to fully examine the crowding effects using the NARDL approach in South Africa. The aim of the study is to examine whether public investment has a symmetric or an asymmetric impact on private investment in South Africa. The NARDL captures both the short- and long-run asymmetries in the variables included in the study. The NARDL results show that the negative shocks in public investment lead to a decrease in private investment in the long and short run. The study also found that the positive shocks in public investment from the previous period lead to an increase in private investment.

The other variables in the long run for the NARDL model show that economic growth has a negative impact, while credit to the private sector has a positive and statistically significant impact on private investment. Interest rate, inflation and trade openness are found to be statistically insignificant in the long run. In the short run, economic growth and inflation rate are found to have a negative impact on private investment, while interest rate has a positive and statistically significant impact on private investment. In the ARDL model, economic growth is found to have a positive impact on private investment in the long and short run, while trade openness has a negative impact in the long run and a positive effect in the short run. Credit to the private sector has a significant positive impact in the long run and inflation has a significant negative effect in the short run. The findings of the Wald test show that public investment has a long and short run asymmetric relationship with private investment. Therefore, public investment asymmetrically influences the level of private investment in South Africa.

The study found that private investment is negatively affected by the negative shocks in public investment in the long and short run. It is, therefore, recommended that the government should continue to invest in sectors where it will not compete with the private sector. In addition, the government should engage the private sector in infrastructure investment through the public–private partnership (PPP), which was first introduced in South Africa in 1985. It is also recommended that the government should implement expansionary fiscal policies during the negative shocks in order to mitigate the effects of negative shocks on public investment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request.

Notes

1. see also Muthu (2017), Muyambiri and Odhiambo (2018).

References

- Abdulkarim, Y., & Saidatulakmal, M. (2021). The impact of fiscal policy variables on private investment in Nigeria. African Finance Journal, 23(1), 41–18.

- Acosta, P., & Loza, A. (2005). Short and long run determinants of private investment in Argentina. Journal of Applied Economics, 8(2), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.2005.12040634

- Afonso, A., & St Aubyn, M. (2019). Economic growth, public, and private investment returns in 17 OECD economies. Portuguese Economic Journal, 18(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-018-0143-7

- Ahsan Abbas, A., & Ahmed, E. (2019). Private, public and foreign investment nexus in Pakistan: An empirical analysis of crowding-in/out effects. Forman Journal of Economic Studies, 15, 181–208. https://doi.org/10.32368/FJES.20191508

- Ajide, K. B., & Lawanson, O. (2012). Modelling the long-run determinants of domestic private investment in Nigeria. Asian Social Science, 8(13), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n13p139

- Akber, N., Gupta, M., & Paltasingh, K. (2020). The crowding-in/out debate in investments in India: Fresh evidence from NARDL application. South Asian Journal of Macroeconomics and Public Finance, 9(2), 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277978720942676

- Akçay, S., & Karasoy, A. (2020). Determinants of private investments in Turkey: Examining the role of democracy. Review of Economic Perspectives, 20(10), 23–49. https://doi.org/10.2478/revecp-2020-0002

- Argimón, I., González-Páramo, J. M., & Roldán, J. M. (1997). Evidence of public spending crowding-out from a panel of OECD countries. Applied Economics, 29(8), 1001–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368497326390

- Ayeni, R. K. (2020). Determinants of private sector investment in a less developed country: A case of the Gambia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020.1794279

- Babu, J. O., Abala, D., & Mbithi, M. (2022). Public infrastructure investment and private investment in East African community: Crowding-in or crowding-out?. International Journal of Sustainable Economy, 14(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSE.2022.119718

- Bahal, G., Raissi, M., & Tulin, V. (2018). Crowding-out or crowding-in? Public and private investment in India. World Development, 109, 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.004

- Başar, S., & Temurlenk, M. S. (2007). Investigation crowding-out effect of government spending for Turkey: A structural VAR approach. Atatürk Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, 21(2), 95–104.

- Bedhiye, F. M., & Singh, L. (2022). Fiscal policy and private investment in developing economies: Evidence from Ethiopia. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(7), 1719–1733. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2021.1982664

- Bint-E-Ajaz, M., & Ellahi, N. (2012). Public-private investment and economic growth in Pakistan: An empirical analysis. Pakistan Development Review, 51(4), 61–77.

- Bouakez, H., Guillard, M., & Roulleau-Pasdeloup, J. (2017). Public investment, time to build, and the zero lower bound. Review of Economic Dynamics, 23, 60–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.red.2016.09.001

- Brock, W., Sheinkman, A., Dechert, J. A., & LeBaron, B. (1996). A test for independence based on the correlation dimension. Econometric Reviews, 15(3), 197–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/07474939608800353

- Cheah, S. -P., Yiew, T. -H., & Ng, C. -F. (2017). A nonlinear ARDL analysis on the relation between stock price and exchange rate in Malaysia. Economics Bulletin, 37(1), 336–346.

- Cruz, B. D. O., & Teixeira, J. R. (1999). The impact of public investment on private investment in Brazil, 1947-1990. CEPAL Review, 1999(67), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.18356/fbcbe22d-en

- Dash, P. (2016). The impact of public investment on private investment: Evidence from India. The Journal for Decision Makers, 41(4), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/0256090916676439

- Erden, L., & Holcombe, R. (2005). The effects of public investment in developing economies. Public Finance Review, 33(5), 575–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142105277627

- Frimpong, J. M., & Marbuah, G. (2010). The determinants of private sector investment in Ghana: An ARDL approach. European Journal of Social Science, 15(2), 250–261.

- Ghali, K. H. (1998). Public investment and private capital formation in a vector error correction model of growth. Applied Economics, 30(6), 837–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368498325543

- Greene, J., & Villanueva, D. (1991). Private investment in developing countries: An empirical analysis. Staff Papers, 38(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867034

- Haroon, M., & Nasr, M. (2011). Role of private investment in economic development of Pakistan. International Review of Business Research Paper, 7(1), 420–439.

- Hyder, K. (2001). Crowding-out hypothesis in a vector error correction framework: A case study of Pakistan. Pakistan Development Review, 40(4II), 663. https://doi.org/10.30541/v40i4IIpp.633-650

- Karagöl, E. (2004). A disaggregated analysis of government expenditures and private investment in Turkey. Journal of Economic Cooperation, 25(2), 131–144.

- Kuştepeli, Y. (2005). Effectiveness of fiscal spending: Crowding-out and/or crowding-in? Yönetim ve ekonomi, 12(1), 185–192.

- Makuyana, G., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2018). Public and private investment and economic growth: An empirical investigation. Studia Universitatis Babeș-Bolyai Oeconomica, 63(2), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.2478/subboec-2018-0010

- Makuyana, G., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2019). Public and private investment and economic growth in Malawi: An ARDL-bounds testing approach. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 32(1), 673–689. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1578677

- Maluleke, G., Odhiambo, N. M., & Nyasha, S. (2023). The determinants of domestic private investment in Malawi: An empirical investigation. Economia Internazionale/International Economics. Forthcoming https://www.iei1946.it/article/617/the-determinants-of-domestic-private-investment-in-malawi-an-empirical-investigation

- Marcos, S. S., & Vale, S. (2022). Is there a nonlinear relationship between public investment and private investment? evidence from 21 organization for economic cooperation and development countries. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2712

- Mitra, P. (2006). Has government investment crowded-out private investment in India? The American Economic Review, 96(2), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282806777211621

- Mohanty, R. K. (2019). Does fiscal deficit crowd out private corporate sector investment in India? The Singapore Economic Review, 64(5), 1201–1224. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217590816500302

- Mose, N., Jepchumba, I., & Ouru, L. (2020). Macroeconomic determinants of domestic private investment behaviour. African Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(2), 30–37.

- Mutenyo, J., Asmah, E., & Kalio, A. (2010). Does foreign direct investment crowd-out domestic private investment in sub-Saharan Africa. The African Finance Journal, 12(1), 27–52.

- Muthu, S. (2017). Does public investment crowd-out private investment in India? Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 9(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFEP-02-2016-0016

- Muyambiri, B., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2018). South Africa’s financial development and its role in investment. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice, 7(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.2478/jcbtp-2018-0005

- Naa-Idar, F., Ayentimi, D. T., & Frimpong, M. J. (2012). A time series analysis of determinants of private investment in Ghana (1960-2010). Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 3(13), 23–33.

- National Treasury. (1996). National Budget 1996. Available at: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/nationalpercent20budget/default.aspx (Accessed: 25 August. 2019)

- National Treasury. (2008). Medium Term Budget Policy Statement. Available at: http://www.treasury.gov.za/documents/mtbps/default.aspx (Accessed: 21 May. 2020)

- Ngeendepi, E., & Phiri, A. (2021). Do FDI and public investment crowd in/out domestic private investment in the SADC region? Managing Global Transitions, 19(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.26493/1854-6935.19.3-25

- Nguyen, V. (2022). The crowding-out effect of public debt on private investment in developing economies and the role of institutional quality. Seoul Journal of Economics, 35(4), 403–424. https://doi.org/10.22904/sje.2022.35.4.003

- Nguyen, C. T., & Trinh, L. T. (2018). The impacts of public investment on private investment and economic growth: Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Asian Business and Economic Studies, 25(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/JABES-04-2018-0003

- Odedokun, M. O. (1997). Relative effects of public versus private investment spending on economic efficiency and growth in developing countries. Applied Economics, 29(10), 1325–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036849700000023

- Omojolaibi, J. A., Okenesi, T. P., & Mesagan, E. P. (2016). Fiscal policy and private investment in selected West African countries. CBN Journal of Applied Statistics, 7(1), 277–309.

- Oshikoya, T. W. (1994). “Macroeconomic determinants of domestic private investment in Africa: An empirical analysis. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 42(3), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1086/452103

- Ouédraogo, R., Sawadogo, H., & Sawadogo, R. (2019). Impact of public investment on private Investment in sub-Saharan Africa: Crowding in or crowding out? African Development Review, 31(3), 318–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12392

- Pal, D., & Mitra, S. K. (2016). Asymmetric oil product pricing in India: Evidence from a multiple threshold nonlinear ARDL model. Economic Modelling, 59, 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2016.08.003

- Pereira, A. M. (2001). On the effects of public investment on private investment: What crowds in what? Public Finance Review, 29(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/109114210102900101

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Presidency of South Africa. (2012). Executive summary- National Development Plan 2030 – Our future – make it work. [Online] Available at http://www.gov.za/issues/national-development-plan-2030 [Accessed 11 June. 2019].

- Ramirez, M. D., & Nazmi, N. (2003). Public investment and economic growth in latin america: An empirical test. Review of Development Economics, 7(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9361.00179

- Rashid, A. (2005). Public/Private investment linkages: A multivariate cointegration analysis. Pakistan Development Review, 44(4), 805–817. https://doi.org/10.30541/v44i4IIpp.805-817

- Saeed, N., Hyder, K., & Ali, A. (2006). The impact of public investment on private investment: A disaggregated analysis. Pakistan Development Review, 45(4), 639–663. https://doi.org/10.30541/v45i4IIpp.639-663

- Saghir, R., & Khan, A. (2012). Determinants of public and private investment an empirical study of Pakistan. International Journal of Business and Science, 3(4), 183–188.

- Şen, H., & Kaya, A. (2014). Crowding-out or crowding-in? Analysing the effects of government spending on private investment in Turkey. Panoeconomicu, 61(6), 631–651. https://doi.org/10.2298/PAN1406631S

- Shankar, S., & Trivedi, P. (2021). Government fiscal spending and crowd-out of private investment: An empirical evidence for India. Economic Journal of Emerging Markets, 13(1), 92–108. https://doi.org/10.20885/ejem.vol13.iss1.art8

- Shin, Y., Yu, B. C., & Greenwood-Nimmo, M. (2014). Modelling asymmetric cointegration and dynamic multipliers in a nonlinear ARDL framework. In R. Sickels & W. Horrace (Eds.), Festschrift in honor of Peter Schmidt: Econometric methods and Applications (pp. 281–314). Springer.

- Sineviciene, L., & Vasiliauskaite, A. (2012). Fiscal policy interaction with private investment: The case of the baltic states. Inzinerine Ekonomika-Engineering Economics, 23(3), 233–241. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.23.3.1934

- Tan, B.W., Tang, C.F. (2012). The dynamic relationship between private domestic investment, the user cost of capital, and economic growth in Malaysia. Economia Politicia, 30 (2), 221–246.

- World Bank. (2021). World development indicators [ Online] https://databank.worldbank.org/data/source/world-development-indicators# [accessed 7 May. 2021]

- Zivot, E., & Andrews, D. W. K. (1992). Further evidence on the great crash, oil prices shock and the unit root hypothesis. Journal of Business and Economics Statistics, 10(3), 251–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.1992.10509904