?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Access to finance is one of the factors influencing economic activities. The current study aimed at determining the role of finance in the South African agro-industrialization relationship. To achieve the study objective, bounds testing, the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and error correction approaches were applied on quarterly time series data spanning between the first quarter of 1994 and the last quarter of 2021. Additionally, an interaction term was included to assist the aforementioned models in determining linkage between agriculture and industrial outputs through farmer’s access to finance. Findings revealed that agricultural output and finance are valid forecasters of the industrialization behaviour in the long-run. Access to finance leads to industrial growth while agricultural output growth causes a decline in the industrialization. Nonetheless, aggregate growth of both financial access and agricultural output are associated with industrial output in the short-run. Grounded of the study findings, this study concludes that financial access influence both agriculture and industrial output. Consequently, improving famers’ financial access through financial facilities, financial intermediaries and government subsidies could be a worthwhile strategy or policy to enhance a country’s industrialization. As implication of the study, obtained finding can assist in linking effectiveness of primary, secondary and tertiary economic sectors in South Africa.

1. Introduction

Agricultural sector plays an important role in most countries especially those with developing economies. The strategic role of agriculture sector on economic growth is justified by its historical contribution towards economic development within developed economies (countries). For instance, in England, the USA and Japan, the agricultural revolution had paved the way for industrial revolution (Omofa, Citation2020). In these countries, a combination of new technology and government policies encourage farmers to increase their output and income while reducing production costs and gave birth to industrial revolution. The relationship that exists between agricultural development and industrialization is, instead of substitution or alternative, complementary. In terms of input-output, a mutual support exists between these two sectors. The agricultural sector is necessary to industrial development as it serves as the source of raw material for industrial production. Consequently, lagging of agricultural development can contribute to high price of industrial output and hamper economic growth of a country (Praburaj, Citation2018). In most countries, agriculture and manufacturing (industrial) sectors are prime sources of food security, job creation, economic growth and development (Anetor et al., Citation2016).

In South Africa, the agriculture sector is divided into two main categories namely small-scale (farming for subsistence) and large-scale (commercial farming). Additionally, the agriculture sector is one of the sources of the country’s food security, job creation, national exports and provision of raw material for the manufacturing sector. Although the contribution of agriculture sector has recently been declining and fluctuating between 0.3 and 2.6 for the period ranging from 2019 to 2020 (and it only grew by 0.1 over 10 years, that is from 2.2 percent in 2010 to 2.3 in 2020 (STATS SA, Citation2020)). This sector remains one of largest sectors contributing to GDP growth and employment boosters in South Africa (C. Allen et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, approximately 68 percent of agricultural production are required in production process of final products in manufacturing sector (Donnelly, Citation2021; Southafrica.info, Citation2013). Consequently, the agriculture sector not only it contributes to economic growth and industrialization, it is also perceived, in South Africa, as a channel through which the country can achieve its economic growth and development (Pienaar, Citation2013).

Despite the contribution of the agricultural sector towards economic and development growth, the South African agriculture sector has been experiencing production constraints that include price and yield variability, severe drought and hail which led financial stress of over 70 percent of the south African farmers (AgriSA, Citation2019; Donnelly, Citation2021).

The literature argued that the agricultural output and its sustainability, in South Africa, depends of access to finance. Without the latter, the agricultural output would remain at its minimal (Groenewald & Jordaan, Citation2012). Thus, contributes less to other economic activities. To overcome the financial issues and improve the contribution of the contribution of agricultural output towards other sectors’ output, especially the manufacturing sector, access to finance is a requirement. The sector can acquire finances through government expenditure and involvement of financial institution in agricultural activities. However, the government involvement (subsidies) should be well managed as it has an asymmetric impact on agriculture sector. On one hand government expenditure on agriculture enhances the sector’s production capacity, while on the other hand it obstructs private investors within the sector and thus reduces the sector’s output (Moreno-Dodson, Citation2008). Grounded on the above information and that the little is known about the impact of finance and agriculture sector on industrial output, it is important to determine the role of agro-finance interaction on industrialization in South Africa.

The remaining part of the study is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a brief literature review. Sections 3 and 4 provide the study methodology and empirical findings, respectively. The last section, Section 5, presents the study’s summary, recommendations, limitations and opportunities for future studies.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical assumption of the study

Although there are no specific theories portraying the linkage between industrialization and agricultural sector. Johnston and Mellor (Citation1961) assumption stipulated that agriculture plays a significant role in both economic development and industrialization. These authors added that, under closed economy, increased productivity in the agriculture sector creates more income for domestic farmers while reducing food prices in local market and increase household’s savings. The latter allows the deployment of capital towards domestic industry’s investment resulting in expansion local market for industrial output. Nonetheless, the Johnston and Mellor (Citation1961) hypothesis that agricultural enhancement precedes industrialization was refuted by Clark (Citation2018) and R. C. Allen (Citation2009). Additionally, although Clark (Citation2014) believes that the agriculture revolution was a precursor to industrial revolution, he also argues that his view opposes to those of historians suggesting that agriculture was complete by itself and it did not need evolution to link with industrialization. Additionally, Gardner and Tsakok (Citation2007) posited that the causal relationship between industrial development and agriculture remains complex and difficult to unravel. Consequently, the agro-industrialization and finance intermediation remains a topic for debate among researchers and scholars.

2.2. Brief empirical literature review

Numerous studies assessed significance and performance of different credit provider and their linkage with agriculture and economic development. Using logit regression, Rahman et al. (Citation2014) analysed the impacted of agricultural credit on agricultural yield in Pakistan. The study results suggested that more credit received by farmers results in increase of agricultural output. Thus, authors concluded that a significant and positive relationship exists between finance and agricultural output. Similar studies were conducted in Nigeria and South Africa analysing the cointegration between agricultural loan size and agricultural output. Findings of these studies revealed that not only the big size of loan provided to agricultural activities increases the sector’s output, it also contributes to economic growth of the country. Nonetheless, a study conducted in Nigeria found that the high interest rate charged by financial institutions reduces the appetite of taking loan and the amount of money loaned and thereafter reduces the agricultural output. However, the one in South Africa indicated that a positive relationship between agro-finance and agricultural yield exist only for the short-run and the agro-finance inversely relates to the short-run agricultural output (Chisasa & Makina, Citation2015; Nwankwo, Citation2013). These studies complemented findings of Anthony (Citation2010) indicating increasing agro-credit leads to agricultural output growth and stimulates economic growth which, in return, favours industrial development.

The positive effect of financial access or credit on agricultural output is not a linear and it is subjected to a specific country and the time for loan. Reyes et al. (Citation2012) analysed the impact of access to credit on farm productivity in Chile’s agricultural sector and found that it takes time for the acquired credit to impact on the sector’s productivity. In other words, short-term credit has no significant effect on agricultural productivity. Similarly, the study of Mbutor et al. (Citation2013) assessed the contribution of financial access to the Nigerian agricultural production and found it moderately insignificant. In this regards, the study of Obansa and Maduekwe (Citation2013) revealed that despite its contribution, local financing is not enough to stimulate adequate agricultural output. The study then highlights the necessity of external finances and investments in the agricultural sector to close the gap left by domestic financing and improve agricultural contribution to economic growth.

2.3. Agro-industrial and finance in South Africa

Although the food security remains an issue, as in most sub-Saharan countries, the agriculture sector plays as significant role in the South African social and economic development (Swanepoel & Tshuma, Citation2017). This sector’s contribution is recognized in various economic indicators. In 2019 only, the South African agriculture sector contribute R81 337 million to the gross domestic product (GDP) while 70 percent of the sector’s production was used as intermediate products. Therefore, agriculture sector is considered, according to the Department of agriculture, land reform and rural development (Citation2021) as engine of the national economic growth. The South African agriculture sector is one of major source of foreign currency to the country and key provider of employment especially in rural area. Consequently, employment and income for approximately 8.5 million of South African are directly or indirectly dependent to the agriculture sector (Aguera et al., Citation2020). Irrespective the effect of COVID−19 on global and national economy, the South African agriculture sector was one of four sectors that shown great performance between 2020 and 2021. This sector grew by 13 percent in 2020 and 8.3 percent in 2021, respectively (Campbell, Citation2022). The performance of the agriculture section is subjected to the government policies that enhance agriculture development and the collaboration that exist between financial institutions and the mentioned sector (Coetzee et al., Citation2002; Oberholster et al., Citation2015).

Besides the linkage that exists between agriculture and finance in the South African economy, it was noted that agriculture contribute significantly to the production and value added in manufacturing sector and other industries (agro-processing) can acquire their raw or semi-finished material from the agriculture sector (Chitonge, Citation2021). Agriculture does not only provide raw material for food processing, it also provides raw material for other industry such as textile, paper industry, textile industry, sugar and vegetable oil. Thus, agriculture improvement forms the base of industrial development.

The previous two paragraphs highlight the association between agriculture output and finance on one hand and the linkage between agriculture and manufacturing (industrialization) output on the other hand. It is important to assess to which extend the combination of finance and agriculture (agro-finance) may impact on the South African manufacturing output or industrialization in South Africa since the beginning of democratic government in 1994. The next section discusses data and approaches used to achieve the study objective.

3. Data, variables and analytical approach

3.1. Data and variable

The current study engages with a time series data covering for a period from 1994 to 2021. In other words, the analysis of the study covered 108 quarterly observations. The sample period was selected based on data availability and was sourced from the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) and Quantec EasyData. The variables of the study consist of gross value added at basic prices of manufacturing (used as a proxy for industrialization) and measured, gross value added at basic prices of agriculture and Gross value added at basic prices of finance within the financial institutions (used as a proxy for financial access). Selection of these variables also was built on the interaction that exists amongst them and the explored theory. The theory states that agricultural sector and output provides inputs to industrialization. Similar, financial access is need for industrial development. Consequently, it can be hypothesized that a positive relationship exists between financial access, agricultural output and industrial development (Adeleye et al., Citation2018; Dercon & Gollin, Citation2014). To lessen the model white noise, control for outliers and establish the responsiveness of dependent variables towards within the explanatory variables, the study underlined variables were transformed into natural logarithm.

3.2. Analytical approach

The literature provides a variety of analytical models and approaches. However, each of those models has its drawbacks and advantages. The current study employed the the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model. The latter was selected based on its numerous advantages that include using a simple equation, flexibility towards variables order of integration, production of robust results when applied to a small sample, and generating both long-run and short-run relationship simultaneously (Habanabakize, Citation2021). Additionally, in the application of ARDL model, the representation of Error correction (EC) assists in assessing a cointegrating relationship among variables under consideration. Furthermore, the availability of bounds testing procedure allows drawing a conclusive inference irrespective of whether variables are integrated of order zero or order one (Pesaran et al., Citation2001). Considering the log-level ARDL (p, q, …, q) industrialization model is constructed as follow:

where and variables represented by

are cointegrated or can either be integrated of I(0) or I(1). The coefficients of the model are denoted by

and

while

is a constant or intercept.

denote orders of optimal lag and

represents the white noise.

To determine the role played by financial access in the agro-industrialization relationship, in addition to the variables represented in EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) , an interaction term (

) was created and added to the model. This additional variable, enhances the understanding of the linkage between financial accesses in respect of channels through which both finance and agriculture output affect industrialization. Consequently, the subsequent EquationEquation 2

(2)

(2) was estimated to assess whether the linked relationship between agricultural and industrial outputs depend farmers’ access to finance. The modification of equation one is expressed as:

A multivariate framework that employs bounds testing for cointegration was used to assess the presence of a long-run relationship between financial access, agricultural and industrial outputs. Thus, the existence of long-run relationship among the underpinned variables was tested using the unrestricted error correction model (UECM) expressed as follows:

where in e EquationEquation 3

(3)

(3) represents the difference operator. The existence of cointegration among variables in EquationEquation 3

(3)

(3) is established using the F test. The following null hypothesis was tested against its alternative:

No cointegration:

Cointegration:

As the null hypothesis is tested against the alternative, the value of F-statistic is compared to the critical values. A larger F-statistic compared to the upper bound critical values indicates the rejection of the null hypothesis of no cointegration and the conclusion is that variables in EquationEquation 3(3)

(3) Cointegrate. Alternatively, the lower F-statistic in comparison with lower bounds critical values implies a failure to reject the null hypothesis and a conclusion that variables in EquationEquation 3

(3)

(3) do not cointegrate. Unless further information is provided, an F-statistic with a value that falls between upper bounds and lower bounds critical values leads to no conclusion. If the first option prevails (F-statistic > upper bound critical values) the subsequent error correction model is estimated:

where denotes the speed of adjustment coefficient and

denotes the long-run coefficient. EquationEquation 4

(4)

(4) shows that

is subjected to changes in its own lag, changes in the differentiated independent variables and also subjected to the equilibrium error term. In case the latter is positive, the model is explosive (no return to long-run equilibrium). This implies that

is expected to negative and statistically significant as its absolute value determines how long the model will revert back to long-run equilibrium. The optimum number of lags employed by the model were obtained using the Bayesian information criteria (BIC).

4. Regression results and discussion

4.1. Correlation and summary statistics

The first step of the study’s empirical analysis was to provide the preliminary analysis that provides central tendency of used data and correlation between the study variables. Table displays both summary statistics and correlation matrix. The result in the table show that over the analysed period, industrial recorded the output of 110,520 million, while agriculture recorded 15,576 million and 87,264 for finance, respectively. The highest output recorded over the period was 793,660 million for industrial, 200834 million for agriculture and 1,390,055 million for finance. Average output recorded was 391,476.4 million for industrial, 66934.13 million for agriculture and 602,670.6 million for finance. The summary statistics indicate that changes in agricultural output and Finance influence changes in industrial output. Additionally, the correlation matrix suggests that finance and agriculture are positively associated with industrial output while finance is also positively correlated with agricultural output. Despite these findings, it is important to conduct robust scientific test to reach a conclusive discussion on the relationship between the study variables.

Table 1. Correlation matrix and summary statistics

4.2. Unit root test

Although testing integration order is not a major requirement under the ARDL model, it is necessary to highlight that the model does not produce accurate result when applied on I(2) variables. Therefore, it is fundamental to perform a stationarity text to certain that none of the underpinned variables is integrated of the second order. To achieve this, the study applied the Augmented Dickey–Fuller unit root test and the outcome in Table indicates a mixture of integration orders for the study variables. In other words, industrial output is I (0) while agricultural output and finance are I(1). Since the study series is a mixture of I(0) and I(1) and that there is no I(2), the ARDL is the appropriate model for cointegration analysis.

Table 2. Unit root test results

4.3. Bounds testing for cointegration

As the study aim was to determine the relationship between industrial output, agricultural output and finance, bound test for cointegration was conducted to test whether a long run relationship exists between variables. Two models were formulated. The first model tested if long-term changes in agricultural output and finance, individually, cause changes in industrial output. The second model intended to assess whether a combination of agricultural output and finance can shock industrial output. The results in Table evidence the presence of cointegration amongst the variables. This is proven by the F-statistics values of 14.57 for Model 1 and 9.37 for Model 2, which larger than all the upper bound critical values. Consequently, the null hypothesis for no cointegration is rejected in favour of the alternative.

Table 3. Bound testing results

4.4. Long-run, short-run estimates and error correction

The presence of long-run relationship requires, ipso factor, the error correction model estimation. As indicated in eEquation 4 and discussed above, error correction term (ECT) must be negative and statistically significant to allow the model short-run shocks to revert back to long-run equilibrium, otherwise the model becomes explosive. The obtained ECT has a significant and negative coefficient of−0.278297. This implies that the model short-term disturbance will adjust to long-run equilibrium with an approximate quarterly speed of adjustment of 28 percent in each quarter.

The estimated long-run coefficients, in Table , are statistically significant implying that both agricultural output and finance are useful in forecasting for industrial output. Nonetheless, the long-run changes in these two variables (agricultural output and finance) cause conflicting responses of industrial output. While increase in financial access results in increase of industrial output, the latter decline as result of the agricultural output growth. In other words, a 10 percent increase in finance is associated with 0.8 percent increase in industrial output, ceteris paribus. On the other hand, industrial output declines by 5.15 as a response to a 10 percent increase in agricultural output. These results imply that the South African manufacturing industries do not use much input from agricultural sector. Another justification would be that the South African agricultural product is more expensive compared to import products and therefore, industries would prefer to use imported input rather than the domestic ones. This argument can be justified using the regression results in Table where the moderation variable (Agric*Finance) shows that the intermediation of agricultural output and finance has a positive and statistically significant effect on industrial output. That is, a 10 percent increase in the intermediation of agricultural output and finance leads to 0.48 percent increase in the industrial output. These findings support the a priori hypothesis suggesting that enhancement of agricultural output and more financial intermediation are required to improve industrial production. Similar findings were reached by the study of Adetiloye (Citation2012), Anetor et al. (Citation2016), Ayeomoni and Aladejana (Citation2016), Egwu (Citation2016), Mbutor et al. (Citation2013), and Umaru and Zubairu (Citation2012). These studies have found that easy financial access improves the agricultural output which in return contributes to a country’s industrialization.

Table 4. Long-run estimates

Considering the short-run analysis, the result in Table shows that all the underpinned variables have a significant effect on the short-run industrial realization. First, the lagged performance of industrial and agricultural output has an inverse relationship on current industrial output. That is, a percentage change in the past realization of industrial output is associated with 0.18 decline in current level of industrial output, while a percentage change in the agricultural current output revel causes industrial output to decrease by 0.14 percent. In contrast, current industrial output increases by 0.98 as response to a percentage increase in financial access. In support of long-run results, an intermediation between agricultural and finance is also positive and statistically significance to improve short-run industrialization. Thus, a percentage increase in the short-run interaction between Agric*Finance leads to a 0.013 increase in the industrial output, ceteris paribus. The error correction term is negative and statistically significant. This implies that approximately 28 percent of shocks in the model is adjusted each quarter and the model reverts to it long-run equilibrium after 3.59 quarters. In other words, it takes approximately a year for industrial output to adjust to shocks in both agriculture output and finance.

Table 5. Short-run estimates

The presence of long-run run relationship among variables implies the existence of one or more causal relationship among variables. For this reason, the Granger causality was performed to determine the direction of causation if any. The Granger causality test outcome presented in Table suggests the presence of a statistical causality among variables. A unidirectional causality exists between industrial and agricultural output, bidirectional causation between finance and industrial output, and a between intermediation of LAGR_LFIN agricultural output, and a unidirectional causation between LAGR_LFIN and industrial output. These results indicate that intermediation of finance and agriculture plays an important short-run role to influence the behaviour of industrial short-run output.

Table 6. Granger causality results

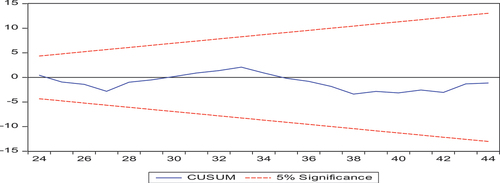

4.5. Diagnostic checks

Various diagnostic tests were perfumed to ascertain the robustness of both models and reliability of the estimated findings. Test performed include Breusch–Godfrey for autocorrelation, Breusch–Pagan for heteroscedasticity, Jarque–Bera for normality, Ramsey RESET for misspecification and for stability. The results from all mentioned tests and the conclusions made are displayed in Table and Figure . In short, the results indicate that variables are normally distributed, models are well specified, no serial correlation, no heteroscedasticity and parameters are stable.

Table 7. Diagnostic outcome

5. Summary and concluding remarks

The study aimed to analyse the role played by finance in the agro-industrialization in South African economy. The analysis of both long-run and short-run relationship was performed through the application of ARDL and ECM models on time series data from 1994 to 2021. The results indicated that the agriculture sector is not a positive forecaster of long-run industrialization in South Africa. Nonetheless, jointed with finance access, agriculture is having a positive influence on the South African industrialization in both long-run and short run. These results imply that improving financial access for the South African famers, especially small farmers, can contributes to the industrial realization. Thus, the collaboration between the South African government and financial intermediaries can bring a solution to the lack of positive influence of agricultural sector towards industrialization. Credit facilities towards commercial famers’ access to finances and increase government subsidies are the major two policies that can assist not only improving agricultural sector but also in promoting the country’s industrialization. The success of these two sectors, agriculture and industrial (manufacturing) will bring solution to the persistence challenge of job creation.

Agriculture as a predictor of industrial output in South Africa is not only subjected finance (capital) but to other factors not considered in this study such as farmers’ skills, labour availability, technology, soil, climate, markets and government involvement. Future study should consider investigating the role of listed factors to determine the most useful and beneficial towards agricultural sector first and then manufacturing sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adeleye, N., Osabuohien, E., Bowale, E., Matthew, O., & Oduntan, E. (2018). Financial reforms and credit growth in Nigeria: Empirical insights from ARDL and ECM techniques. International Review of Applied Economics, 32(6), 807–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2017.1375466.10.1080/02692171.2017.1375466

- Adetiloye, K. A. (2012). Agricultural financing in Nigeria: An assessment of the Agricultural Credit Guarantee Scheme Fund (ACGSF) for food security in Nigeria (1978-2006). Journal of Economics, 3(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2017.1375466

- AgriSA. (2019), Agricultural drought report, AgriSA centre of excellence. Retrieved November 10, 2022, from https://rpo.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Agriculture-Drought-Report2019.pdf

- Aguera, P., Berglund, N., Chinembiri, T., Comninos, A., Gillwald, A., & Govan Vassen, N. (2020). Paving the way towards digitalising agriculture in South Africa. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2020/09/PavingthewaytowardsdigitalisingagricultureinSouthAfricaWhitepaper272020105251.pdf

- Allen, R. C. (2009). The British industrial revolution in global perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Allen, C., Asmal, Z., Bhorat, H., Hill, R., Monnakgotla, J., Oosthuizen, M., & Rooney, C. (2021). Employment creation potential, labour skills requirements, and skill gaps for young people: A South African case study. Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper No. 202102., Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Anetor, F. O., Ogbechie, C., Kelikume, I., & Ikpesu, F. (2016). Credit supply and agricultural production in Nigeria: A vector autoregressive (VAR) approach. Journal of Economics & Sustainable Development, 7(2), 1–13.

- Anthony, E. (2010). Agricultural credit and economic growth in Nigeria: An empirical analysis. Business and Economics Journal, 14, 1–7.

- Ayeomoni, I. O., & Aladejana, S. A. (2016). Agricultural credit and economic growth Nexus. Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 6(2), 146–158.

- Campbell, R. (2022), Agriculture continues to outperform nearly all other sectors of South Africa’s economy. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/agriculture-continues-to-outperform-nearly-all-other-sectors-of-south-africas-economy-2022-04-01

- Chisasa, J., & Makina, D. (2015). Bank credit and agricultural output in South Africa: Cointegration, short run dynamics and causality. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR), 31(2), 489–500. https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v31i2.9148

- Chitonge, H. (2021). The agro-processing sector in the South African economy: Creating opportunities for inclusive growth. Policy Research in International Services and Manufacturing (PRISM). (Working Paper Series Number 2021-3). www.prism.uct.ac.za

- Clark, G. (2014). The industrial revolution. In Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 2, pp. 217–262). Elsevier.

- Clark, G. (2018). Too much revolution: Agriculture in the industrial revolution, 1700–1860. In The British industrial revolution (pp. 206–240). Routledge.

- Coetzee, G. K., Meyser, F., & Adam, H. (2002). The financial position of South African agriculture (No. 1737-2016-140327). Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/18056/

- Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development. (2021). Economic review of the South African Agriculture 20 20/2 1. Retrieved November 21, 2022, from https://www.dalrrd.gov.za/Portals/0/Statistics%20and%20Economic%20Analysis/Statistical%20Information/Economic%20Review%202020-21.pdf

- Dercon, S., & Gollin, D. (2014). Agriculture in African development: A review of theories and strategies (CSAE Working Paper, WPS/2014-22), 1–42.

- Donnelly, S. (2021). Determinants of credit risk amongst commercial farmers in the midlands area of KwaZulu-Natal. University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- Egwu, P. N. (2016). Impact of agricultural financing on agricultural output, economic growth and poverty alleviation in Nigeria. Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Healthcare, 6(2), 1–7.

- Gardner, B., & Tsakok, I. (2007). Agriculture in economic development: Primary engine of growth or chicken and egg?. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 89(5), 1145–1151.

- Groenewald, J. A., & Jordaan, A. J. (2012). Unlocking credit markets. Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Habanabakize, T. (2021). Determining the household consumption expenditure’s resilience towards petrol price, disposable income and exchange rate volatilities. Economies, 9(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9020087

- Johnston, B. F., & Mellor, J. W. (1961). The Role of agriculture in economic development. The American Economic Review, 51(4), 566–593. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1812786

- Mbutor, O. M., Ochu, R. E., & Okafor, I. I. (2013). The contribution of finance to agricultural production in Nigeria. CBN Economic and Financial Review, 51(2), 1–20.

- Moreno-Dodson, B. (2008). Assessing the impact of public spending on growth and empirical analysis for seven fast-growing countries (Policy Research Working Paper No. 4663). World Bank.

- Nwankwo, O. (2013). Agricultural financing in Nigeria: An empirical study of Nigerian agricultural Co-operative and rural Development Bank (NACRDB): 1990-2010. Journal of Management Research, 5(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v5i2.2806

- Obansa, S. A. J., & Maduekwe, I. M. (2013). Agriculture financing and economic growth in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 9(1), 1–37.

- Oberholster, C., Adendorff, C., & Jonker, K. (2015). Financing agricultural production from a value chain perspective: Recent evidence from South Africa. Outlook on Agriculture, 44(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.5367/oa.2015.0197

- Omofa, F. H. (2020). Role of agriculture in the economic development of a country. Политика, экономика и инновации, 3(32), 1–5.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Pienaar, P. L. (2013). Typology of smallholder farming in South Africa’s former homelands: Towards an appropriate classification system. Stellenbosch University.

- Praburaj, L. (2018). Role of agriculture in the economic development of a Country. Shanlax International Journal of Commerce, 6(3), 1–5.

- Rahman, L., Hussain, S. U., & Taqi, M. (2014). Impact of agricultural credit on agricultural productivity in Pakistan: An empirical analysis. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 3(4), 125–139.

- Reyes, A., Lensink, R., Kuyvenhoven, A., & Moll, H. (2012). Impact of access to credit on farm productivity of fruit and vegetable growers in Chile. [Paper presentation] The International Association of Agricultural Economists (IAAE), pp. 18–24., Foz do Iguacu

- Southafrica.info. (2013). South African yearbook (December 2012). Retrieved November 10, 2022, from http://www.southafrica.info/business/economy/sectors/agricultural-sector.htm#ixzz2RwAeeIJw

- STATS SA. (2020). Census of commercial agriculture 2017 report. Retrieved November 10, 2022, from http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13144

- Swanepoel, P. A., & Tshuma, F. (2017). Soil quality effects on regeneration of annual Medicago pastures in the Swartland of South Africa. African Journal of Range & Forage Science, 34(4), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.2989/10220119.2017.1403462

- Umaru, A., & Zubairu, A. A. (2012). An empirical analysis of the contribution of agriculture and petroleum sector to the growth and development of the Nigerian economy from 1960-2010. International Journal of Sociences and Education, 2(4), 1–12.