?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In this essay, I argue that the various institutional settings of fiscal decentralization observed in developing countries are contingent on institutional quality. Other incentives may exist for policymakers to change the degrees of fiscal power. My research is based on a five-year average of data from 34 developing countries between 1990 and 2014.I employ the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) to address the issue of endogeneity, which is a common issue in fiscal decentralization studies. The findings show a strong nonlinear relationship between institutional quality and fiscal decentralization metrics. In this context, since democracy (polity), participatory democracy, bureaucratic quality, law and order, and fiscal decentralization are all emerging from low levels of development, an increase in the magnitude of these institutional quality variables will further reduce fiscal autonomy.

1. Introduction

For several decades, the issue of intergovernmental power in developing countries has gotten a lot of attention. Subnational governments in developing countries have also been given increasing degrees of fiscal authority, revenue and expenditure responsibilities. As a result, many academics and policymakers have attempted to investigate the effects of fiscal decentralization on other aspects of development such as growth, inequality, and poverty (see Davoodi & Zou, 1998; Sepulveda & Martinez-Vazquez, Citation2011; Uchimura, Citation2012). However, issues concerning the factors influencing fiscal decentralization in developing countries have been surprisingly overlooked.

Another concern, also related to the channels through which countries’ fiscal decentralization can be optimally achieved, confounds researchers. Panizza (Citation1999) and Arzaghi and Henderson (Citation2005) conducted preliminary research into the causes of fiscal decentralization. They argue that the degrees of devolution of revenue and expenditure responsibilities, as well as fiscal resources, are determined by a variety of factors, including a country’s size and population, income, and democracy. Recent research has also looked into the role of political institutions in determining fiscal decentralization (see Bojanic, Citation2020; Feld et al., Citation2008; Jametti & Joanis, Citation2016).

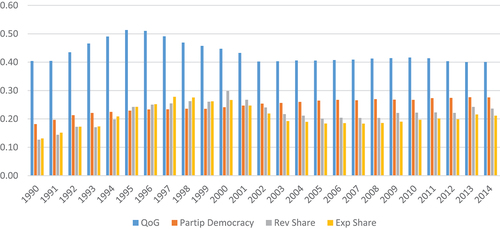

Moving from the controversies surrounding the impact of institutional quality on fiscal decentralization, Figure demonstrates that the economic crisis of 1998–1999 greatly promoted participatory democracy in developing nations, where it increased by 4% in Citation1999–2000. Nevertheless, the quality of government fell significantly by 6% between 1999 and 2000. In contrast, the 2008–2009 economic crisis had a negligible effect on government quality, while participatory democracy grew significantly during this period. Alarcón et al. (Citation2019) demonstrate that external economic shocks reduce a government’s ability to respond to the demands of its citizens, but that citizens also adjust their standards in reaction to limited resources. Similarly, it is evident that some democracies survive the stresses of economic crises while others fail under similar or even less severe conditions (Haggard & Kaufman, Citation1997). Moreover, Andersen and Krishnarajan (Citation2019) note that the ability of bureaucracies to reduce domestic turmoil plays an important role during crises, as bureaucracies of higher shield the populace from poverty and inequality to a greater extent. Overall, the proportion of subnational revenues and expenditures in developing nations increased substantially between 1990 and 2014. The participatory democracy subsequently improved. Nonetheless, the quality of government remained unchanged.

Figure 1. Participatory democracy, quality of government, revenue share, and expenditure share in developing countries, 1990–2014.

In this essay, I will add to these discussions by elucidating the impact of institutional quality on fiscal decentralization in developing countries. Policymakers on either side of the median institutional quality range may have additional incentives to change the degrees of fiscal decentralization. In this regard, my essay can be seen as an extension of Panizza’s (Citation1999) and Arzaghi and Henderson’s (Citation2005) pioneering work by introducing a comprehensive concept of institutional quality. In theory, using democracy and electoral strength to assess institutional quality can be deceptive. According to Rothstein and Teorell (Citation2008), democracy, as it relates to access to governmental power, is a necessary but insufficient criterion for explaining institutional quality. Furthermore, it does not take into account the impact of government quality or governance, i.e. how authority is exercised. As a result, my research seeks to fill a gap in the literature concerning the determination of fiscal decentralization.

Analysis of the impact of institutional quality is becoming increasingly important, especially as developing countries have varying institutional settings for fiscal decentralization. While many people use the revenue and expenditure share of subnational governments as a proxy measure of fiscal decentralization, I also consider self-rule and shared-rule to be fiscal decentralization metrics. In this context, I believe that fiscal decentralization is not solely measured in terms of the preference-matching mechanism, in which subnational governments implement independently the degrees of decision-making regarding taxes and borrowing, as well as the level of responsibilities regarding revenue and expenditures (i.e. self-rule). However, one should also examine subnational governments’ ability to influence central government decision-making. In this context, both local and central governments can collaborate and reach more standardized goals (i.e. shared rule). As a result, my research will shed more light on the factors driving fiscal decentralization.

In terms of time frame, the analysis of the determinants of fiscal decentralization will be conducted from 1990 to 2014 to supplement Jametti and Joanis (Citation2016) work with the most recent dataset, as their analysis only covers the period 1990–2006. The following section is a brief review of the literature on the determinants of fiscal decentralization, with an emphasis on the role of institutional quality in section 3. Section 4 justifies the data and methods discussed in the following section. The next section is devoted to an examination of fiscal decentralization and institutional quality, into which I provide empirical results and some model robustness checks in the analysis of institutional quality in Section 5 and discussions in Section 6. Section 7 discusses the study’s conclusions and limitations.

2. Drivers of fiscal decentralization

Many empirical studies have been conducted to investigate the factors that influence fiscal decentralization. Panizza’s (Citation1999) pioneer work can serve as a starting point for explaining the driver of fiscal centralization. He examines the effect of country size, ethnic fractionalization, income per capita, and level of democracy on revenue and expenditure centralization in 57 countries from 1975 to 1985, including 37 developing countries and 20 developed countries. Unlike Oates (Citation1972), who employs the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) technique, he contends that OLS is ineffective because centralization ratios cannot exceed 100, and thus the independent variables are censored from above. He confirms Oates’ finding that country size and income per capita are negatively correlated with the degree of fiscal centralization by using a Tobit model. Furthermore, fiscal centralization is negatively related to democracy and ethnic fractionalization. Such findings contradict Oates’ findings, according to which ethnic fractionalization was always statistically insignificant and democracy was positively correlated with fiscal centralization.

Arzaghi and Henderson (Citation2005) examine the determinants of fiscal decentralization in 48 countries from 1960 to 1995 in another study. Three approaches are used to assess fiscal decentralization in this context. First, the authors examine 1995 institutional structures in relation to 1965 country conditions. Institutional structures are defined by whether a country had a federal constitution in Citation1995, as well as whether it had local or state democratic elections in addition to a federal constitution. Second, they create a federalism index, which is simply an average of six aspects of federalism: 1) government structure (e.g., official federal versus unitary); 2) election of regional executive; 3) election of local executive; 4) ability of central government to suspend and/or override lower level of government decisions; 5) revenue raising authority of lower level of government; and 6) revenue sharing. Finally, they develop a fiscal centralization metric defined as the share of central government spending over total government spending. They discover that income per capita, population, and area concentration in the largest cities have a statistically significant and positive effect on institutional structures and the federalism index using the Instrumental Variable (IV) random effects and the General Method of Moment (GMM) technique. However, when it comes to fiscal centralization regression, these variables become negative and significant. Furthermore, institutions, as measured by the constitution and democracy, have a negative impact on fiscal centralization.

In the meantime, Jametti and Joanis (Citation2016) examined the impact of government electoral strength on fiscal centralization in 107 countries from 1990 to 2006. Centralization is measured in terms of revenue and expenditure, with the central government’s revenue (expenditure) being defined as a percentage of total government revenue (expenditure). Using the fixed effects (FE) technique, they discover that the government’s share of seats in parliament is negatively correlated with expenditure centralization. However, with revenue centralization, such a variable is statistically insignificant. Other explanatory variables, such as per capita income, population, and area, are statistically significant with regard to both revenue and expenditure centralization.

Canavire-Bacarreza et al. (Citation2016) investigate whether physical geography can predict fiscal decentralization using a panel dataset of 94 countries from 1970 to 2000. In this case, they create a geographical fragmentation index where zero represents the case where the entire population is settled in the same altitude zone and one represents the implausible case where each individual lives at different altitudes. Subnational expenditure and revenue as a percentage of GDP are used to measure fiscal decentralization. According to the results of fixed effect estimation, higher levels of geographical fragmentation are significantly correlated with higher levels of fiscal decentralization in terms of revenue and expenditure. Other control variables, such as per capita income, area, ethnic fractionalization, and institutional variables such as corruption and political rights, all have a significant impact on fiscal decentralization.

Several scholars have not thoroughly examined the role of institutional quality as a determinant of fiscal decentralization in their empirical studies. Panizza (Citation1999), Arzaghi and Henderson (Citation2005), and Jametti and Joanis (Citation2016) only look at the effect of democracy and electoral strength on fiscal decentralization, respectively. As a result, those indicators only correspond to a process-based understanding of institutional quality. Meanwhile, while Canavire-Bacarezza et al. (2017) investigate the effects of political rights and corruption on fiscal decentralization at the same time, distinct aspects of institutional quality should be included in fiscal decentralization regression analyses separately. A procedure like this can collect more process- and outcome-based data on institutional quality. Furthermore, governance quality cannot be defined solely as the absence of corruption, as this is influenced by many other practices that are not typically associated with corruption, such as clientelism, patronage, and elite capture (Rothstein & Teorell, Citation2008).

Overall, several theoretical explanations may account for fiscal decentralization and/or general country decentralization. First, the size of a country can have a significant impact on decentralization. According to Oates (Citation1972), the central government in larger countries cannot maximize economies of scale in terms of providing local public goods and services. He then contends that a subnational government can benefit both consumers and producers more than the central government. Subnational governments can better match the diversity of preferences and needs of local citizens by providing public goods and services. The central government, on the other hand, faces the problem of asymmetric information regarding the costs and benefits of local projects, necessitating the implementation of such projects by the subnational government in order to provide public goods and services in a more cost-effective manner. As a result, when a country is large, it is critical to match heterogeneous preferences and needs while reducing asymmetric information. In other words, as a country grows in size, the amount of public goods and services provided by central government decreases, as do the marginal benefits of centralization. All of these factors put pressure on central governments to decentralize (see Arzaghi & Henderson, Citation2005; Panizza, Citation1999).

Second, despite population preferences, subnational governments can provide better local public goods and services (Oates, Citation1972). Because tastes are not directly observable, such heterogeneity is associated with different ethnic groups, each of which has different preferences for public goods and services (Panizza, Citation1999). As a result, countries with polarized preferences, in which different ethnic groups are spatially separated based on the types of public goods and services they prefer, should be more decentralized than countries with homogeneous preferences. Taste heterogeneity reflects’spatial decay’ in the provision of public goods and services (Arzaghi & Henderson, Citation2005). Problems arise when the central government provides a level and type of public goods and services that only meet the needs of a specific group of people and/or ethnic group in the coastal region, but does not meet the preferences of the hinterland community and/or ethnic group. If the degree of’spatial decay’ increases in a country with greater ethnic diversity, it can foster a greater tendency toward decentralization.

Third, the more democratic a country is, the more likely it is to decentralize. Such a strong assertion is based on the assumption that the degree of fiscal decentralization is determined by the central government, as taxation is more centralized than expenditure. Panizza (Citation1999) develops a model of fiscal decentralization choice in which the central government accepts a higher degree of fiscal decentralization in exchange for enhanced development democratic institutions. Voters can force decentralization by selecting a lower level of provided public goods than that preferred by central government; central government must accept a lower level of centralization. The critical point is that, in a democratic government, central authorities will not use their agenda-setting power (e.g., manipulation of election results and control over voting order) to achieve their objectives. Instead, they will use effective and efficient decision-making to match voter preferences.

Fourth, previous empirical studies indicate a positive relationship between per capita income and fiscal decentralization (see Arzaghi & Henderson, Citation2005; Oates, Citation1972; Panizza, Citation1999). In this context, Wheare (Citation1964) contends that decentralization is a costly but desirable good that can only be afforded by certain societies (e.g. the elite). Decentralization is also considered a superior good (Tanzi, Citation2000). People demand more in terms of the quantity and quality of public goods and services as they become wealthier. Increased income increases government revenue-raising capacity, making decentralization more affordable. Letelier (Citation2005) emphasizes the impact of income on fiscal decentralization as well. The increasing income of a country will stimulate demand for income redistribution and social policies. When combined with rising infrastructure demand, this will put maximum pressure on the top level of government to direct more funds toward income redistribution. As a result, income is positively related to fiscal decentralization.

Fifth, one could argue that electoral competition is a driving force behind fiscal decentralization. Jametti and Joanis (Citation2016) created a model that focuses on the behavior of a central government faced with the dilemma of fiscal decentralization versus fiscal centralization. In this case, central government politicians pursuing the rent-maximization principle may tend to increase spending on public goods primarily for electoral purposes. As a result of the electoral uncertainty, central politicians react. In this context, decentralization is likely to increase as the central government’s electoral strength grows.

A final factor in decentralization is geographic location. Canavire-Bacarreza et al. (2017) investigate the role of geography using Panizza’s (Citation1999) and Arzaghi and Henderson’s (Citation2005) theoretical frameworks (2005). More geographically diverse countries tend to have more heterogeneity among their citizens, including preferences and needs for public goods and services. These researchers discover that geographical factors like elevation, land area, and climate are related to fiscal decentralization. Although infrastructure development tends to reduce the effect of geography on decentralization, this effect is small and often statistically insignificant.

3. The role of institutional quality

In light of the empirical and theoretical studies mentioned above, I believe that institutional quality has an impact on fiscal decentralization and/or decentralization in general, in the sense that poor institutions in a country can stymie the process of devolution of fiscal resources, revenue, and expenditures. I begin my argument by discussing the constitution, as well as the role of laws and regulations in preparing for decentralization (Azfar et al., Citation1999). The constitution is used to carry out a broad principle of decentralization, which must include all levels of government’s rights and responsibilities. The constitution then specifies one or more laws that specify the specific parameters of the intergovernmental fiscal system as well as the institutional design of subnational government structures. A set of regulations associated with each law should describe practices and measures such as subnational governments’ ability to tax, the degrees of intergovernmental fiscal transfers, and subnational governments’ specific spending responsibilities (Litvack & Seddon, Citation1999). As a result, a transparent legal framework contributes to a more sustainable decentralization process.

Decentralization can be aided by democratization. It can generate “bottom-up” pressure for decentralization by creating new political spaces and allowing for subnational direct elections (Montero & Samuels, Citation2004). Decentralization can help subnational governments become more accountable to their constituents. As a result, one could argue that as democratization advances, so does pressure for decentralization, because citizens have expressed a desire for a more responsive government. However, there is little evidence that democratization leads to decentralization in many cases. According to O’Neill (Citation2005), despite the fact that Bolivia had been holding democratic elections for several years, prior to the 1994 Popular Participation Law (Ley de Participación Popular—LPP), local leaders did not demand autonomy or resources. The LPP was enacted not because Bolivia was democratizing, but as part of a larger political-partisan dynamic. Indeed, according to Bardhan and Mookherjee (Citation2006), in some democratic and non-democratic countries, decentralization is viewed as a concession by the central government to regional interests and/or a means to secure the national government’s legitimacy. It can also accompany a national political system transition, either toward democracy or non-democracy.

Moving away from the democratization hypothesis, there may be some political opportunism in which decentralization is used solely for electoral purposes. According to O’Neill (Citation2005), governing parties cannot retain power when it is centralized in the national government, but they believe they have a good chance of retaining power if they can win a significant portion of decentralized power through subnational elections. While O’Neill’s model emphasizes the party’s electoral strength, Garman et al. (Citation2001) concentrate on the interests of the political party elite. According to Garman, decentralization is seen as a way to give subnational political leaders more power. Parties dominated by national leaders will prefer to concentrate fiscal power at the national level, whereas parties dominated by subnational elites will favor greater fiscal decentralization.

While electoral goals may be viewed as a cautious motive for decentralization, political motives can also be a driver of decentralization. According to Bardhan and Mookherjee (Citation2006), multiple counteractions by other stakeholders, combined with variations in political context and the precise nature of the political challenges faced by government or political leaders in power, can result in dynamics in the design, nature, and extent of decentralization reform. This reform can be comprehensive or partial, gradual or radical, and uniform or uneven across a country’s regions. When decentralization laws and policies are not implemented as promised and planned, such political motives can shift decentralization reforms. Faguet and Pöschl (Citation2015) contend that “partial” decentralization is very common in this case, where, for example, spending responsibilities are not followed by decision-making autonomy.

In a decentralized system, subnational governments may also have political authority and access to financial resources. However, if they lack administrative capacity, decentralization risks failing (Manor, Citation1999). As a result, good governance is a necessary condition for effective decentralization implementation. Poor quality bureaucrats, such as corrupt officials at the central government level, may, for example, impede fiscal decentralization. This is because decentralization may limit their ability to eliminate a sector that may contribute to high rent extraction (Fisman & Gatti, Citation2002). Similarly, since decentralization increases accountability, corrupt officials at the subnational government level may oppose its implementation because they want to spend their budgets inefficiently (Oates, Citation1972).

Caveats of the role of institutional quality show that it can influence fiscal and/or general decentralization. In accordance with the spirit of preference matching mechanisms, policymakers in a country with a more established democracy and a higher level of government will grant subnational governments a form of self-rule through which they can implement their own policies in terms of allocating fiscal authority and independently assigning revenue and expenditure responsibilities (Elazar, Citation1987). Policymakers may also choose to cooperate by sharing these authorities with the central government (i.e. shared-rule). For example, constitutions in some Western European countries, which are characterized as having more established democracies and better institutions, allow two parties to jointly decide on national policies (Norton, Citation1991).

Policymakers’ willingness to implement self-rule and shared-rule in their subnational governments is a necessary, but not sufficient, criterion for a developing country to decentralize. However, as Bardhan and Mookherjee (Citation2006) point out, the design, nature, and extent of decentralization reform in a country are also influenced by political opposition and challenges faced by government/political leaders in power. Furthermore, some central government bureaucrats may renegotiate with local elites for sectors that provide them with the greatest net benefit, whereas subnational government officials maintain low rent extraction. Furthermore, some officials in subnational governments may be tempted to overspend their budget. Overall, policymakers on either side of the median institutional quality range are likely to influence the degrees of fiscal powers.

4. Data and methods

My dependent variable, fiscal decentralization, is derived from Hooghe et al. (Citation2016) on Regional Authority Index (RAI) dataset. The RAI combines the self-rule and shared-rule scores (see Table ). Institutional depth, policy breadth, tax autonomy, borrowing autonomy, and representation are the five indicators used to measure self-government. Shared-rule is measured by the sum of the following five indicators: legislative control, executive control, tax control, borrowing control, and constitutional reform.

Table 1. List of variables

My understanding of the decentralization indicator in the dataset revolves around the preference matching mechanism, by which subnational governments are able to independently tax and borrow (i.e. self-rule). Taxing autonomy (0–4) evaluates regional governments’ revenue authority (i.e., tax rates and tax bases). Borrowing autonomy gauges the ability of regional governments (0–3) to borrow. However, local governments may share taxing and borrowing authorities with the federal government (i.e. shared-rule). Fiscal control (0–2) and borrowing control (0–2) indicate whether regions have authority over the central government’s taxing and borrowing policies, respectively. Using this information, I can create a new proxy indicator of fiscal decentralization by summing the scores for fiscal autonomy (i.e. autonomy over taxing and borrowing) and fiscal control (i.e. control over taxing and borrowing) across all levels of government. This methodology supports Tranchant’s (Citation2016) research on the effect of decentralization on conflict.

In this research, I do not use the Government Financial Statistics (GFS) dataset of the IMF (Citation2019). Although the GFS has definitions that are consistent across countries and time, it disregards the degree to which central governments exert control over local revenues and expenditures. In addition, it lumps all subnational governments into a single group, disregarding the number of subnational governments within the country, their intergovernmental transfer types, and their revenue and expenditure differences (see Ebel & Yilmaz, Citation2002; Stegarescu, Citation2005).

The principal variable of interest, institutional quality, is related to the concepts of input and output à la Rothstein and Teorell (Citation2008) and process and outcome à la Murshed et al. (Citation2015). Indicators of democracy are taken from the V-DEM and Polity datasets in terms of input or process. I use the index of electoral democracy from the V-DEM dataset (see Coppedge et al., Citation2019) that seeks to embody the core value of making rulers accountable to citizens. This can be accomplished through the following mechanisms: (1) electoral competition; (2) freedom in political and civil society organizations; (3) clean elections unblemished by fraud or systematic irregularities; and (4) elections that affect the position of the country’s chief executive.

I also employ an index for participatory and deliberative democracy. The participatory principle of democracy emphasizes the active participation of citizens in all electoral and non-electoral political processes, whereas the deliberative principle of democracy emphasizes the decision-making process. The data I use from the V-DEM dataset fall between 0 and 1, with 0 representing the least electoral, participatory, and deliberative democracy and 1 representing the most. The level of democracy in the polity dataset is based on the dataset of basic quality of government, which has been transformed onto a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 representing the least democratic and 10 representing the most democratic.

In addition to democracy, I use government quality as provided by the quality of government dataset, which includes bureaucracy quality (originally on a scale of 0–4), corruption (originally on a scale of 0–6), and rule of law (originally on a scale of 0–6) from the ICRG dataset to measure institutional quality as an output or outcome. Government quality is the arithmetic mean of the ICRG variables, scaled from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better government quality (Dahlberg et al., Citation2016). I also recommend conducting a separate regression for each of these three variables. According to Acemoglu’s et al. (Citation2005) theoretical reasoning, political institutions must be distinguished from economic institutions, which I refer to as institutions of governance. It is important to remember that an authoritarian state can sometimes be better managed than a democracy. My explicit goal is to identify and assess which institutions are more important for fiscal decentralization, as certain institutions may be more affected by the presence of fiscal dependence from the central government.

In accordance with Panizza (Citation1999) and Arzaghi and Henderson (Citation2005), my control variables consist of population, country size (area), and income level (GDP per capita). On population, Letelier (Citation2005) hypothesizes that as population grows, the rising costs of congestion at the local level will tend to increase SNG expenditures relative to those of the central government. This will almost certainly raise the cost of local public goods per resident while decreasing demand. However, he claims that demand for local public goods is generally price inelastic, causing congestion to raise the cost per resident. On the size of country, according to Canavire-Bacarreza et al. (2017), preferences and market access may be more difficult in larger countries, resulting in higher levels of decentralization. To be more specific, a highly geographically diverse country is likely to have different public good provision needs as a result of the environment; these needs are likely to be reflected in differences in preferences. Simultaneously, a geographically dispersed country will face difficulties in implementing access and provision of public goods for its citizens, affecting the institutional design of the public sector. On the level of income, according to Tanzi (Citation2000), decentralization may be a superior good whose demand is likely to increase as per capita income increases. Richer individuals may have more time and greater motivation to participate in local political decision-making. Additionally, they may become more adept at organizing to exert pressure on the central government to devolve authority and financial resources. In addition, an increase in development may cause a shift in preference for locally provided public goods and services. Overall, the dataset of these control variables come from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators report (Citation2015).

In accordance with Letelier (Citation2005) and Bodman and Hodge (Citation2010), I also use military spending as a control variable because subnational governments acquire fewer discretionary powers during social disintegration and upheaval (Bahl & Linn, Citation1992). In this way, social disturbances create an environment in which people accept a larger government, despite the fact that local governments do not contribute to this increase in government spending. Countries that are perpetually threatened by war or internal conflict are likely to be more centralized, all else being equal. This variable is derived from the dataset compiled by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI, Citation2019).

In conclusion, I anticipate that geographically expansive nations will have a greater degree of fiscal decentralization. In addition, it will be higher in developing nations with higher incomes, larger populations, and lower military expenditures. I also anticipate that more democratic nations will be fiscally decentralized. Regarding outcome indicators such as improved law and order, bureaucratic quality, and government quality, nations will advocate for greater fiscal decentralization. Similarly, fiscal decentralization will be greater in countries with less corruption. However, according to the models of Jametti and Joanis (Citation2016), the degree of decentralization depends positively on institutional strength (monotone and non-linear). The results of U-test confirmed that there was a non-linear relationship between institutions and fiscal decentralization. This phenomenon suggests that policymakers on either end of the spectrum of institutional quality may be exposed to alternative incentives.

In Table , subnational governments in developing nations have a relatively low degree of fiscal autonomy (1.6) and control (0.3). In addition, the majority of developing nations have a low level of democracy and bureaucratic quality, a moderate level of law and order, and a relatively effective corruption control. These institutional indicators can provide an early indication of how I will analyze the variables in conjunction with fiscal decentralization indicators. Meanwhile, Table illustrates the degree of separation between fiscal decentralization and institutional variables through a correlation matrix. The majority of democracy variables are negatively correlated with fiscal decentralization indicators, while a significant number of institutional quality variables are positively correlated with fiscal decentralization indicators.

Table 2. Summary of Statistics on Fiscal Decentralization Equation

Table 3. Correlation Among Variables

I begin my investigation into the determinants of fiscal decentralization with a static panel data analysis of 34 developing countries (see Table ) between 1990 and 2014. The model’s specifications are as follows:

Table 4. List of developing countries

where i represents the country and t represents the observation year. Xit is a set of control variables, whereas Insit is a vector of institutional quality variables. All are believed to influence fiscal decentralization (FDit). In addition, εit denotes idiosyncratic error. As the independent variables may influence the year-to-year fluctuations in fiscal decentralization, I will incorporate the average of data over five periods in panel regressions. I also include income group (ui) and period (Ɵt) as fixed effects in the estimation to represent the time-invariant and time-variant of unobserved characteristics, respectively.

In this context, I rely on fixed effects (FE) regressions because the inclusion of ui will at least account for some unobserved preferences of societies within a particular income group, which may determine the degree of institutions and fiscal decentralization at the same time. However, since institutions are endogenous variables (see Digdowiseiso et al., Citation2022), assessments of both fixed and random effects may result in biased and inconsistent outcomes. As a result, instrumental variables (IV) should be the best approach for mitigating the problem of reverse causality. The scarcity of time-variant exogenous instruments has hampered the implementation of such techniques. Faced with the instrument’s difficulty, I conduct a dynamic panel analysis using the lagged value of an endogenous explanatory variable. Thus, I estimate using instrumental variable (IV) estimators within the context of the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM). For reporting purposes, the random effects (RE) regressions with income group fixed effects will also be included in the analysis. However, Hausman tests has been performed which suggested fixed effect in static panel estimator would be a superior estimator of my model.

5. Empirical findings

Supplementary Table 1 refers to the determinants of fiscal decentralization. The baseline regressions are presented in columns (1) to (8) and (17) to (24). Clearly, the effects of institutional quality on fiscal decentralization are marginal. As expected, electoral democracy promotes the devolution of fiscal powers to subnational governments in developing countries where one additional point in electoral democracy contributes to a rise in fiscal autonomy by 2 points, ceteris paribus.

However, this type of democracy, along with participatory and deliberative democracy, has a negative and significant effect on the decisions of subnational governments to share their fiscal authorities with central government. Hence, as mentioned by Montero and Samuels (Citation2004), in democracies and authoritarian regimes with local elections, subnational elites might embrace devolution of responsibilities and resources to enhance their own autonomy from the central government and to build up political capital through policy-making accomplishments and/or patronage.

I also find that size of country are positively and significantly associated with some fiscal decentralization indicators. In addition, although the signs of GDP per capita are negative in several models, these are mostly insignificant in fiscal autonomy and control equations. Meanwhile, military spending is significantly and negatively correlated with some fiscal decentralization estimations.

In Supplementary Table 2, the nonlinear regressions are presented in columns (1) to (8) and (17) to (24). Clearly, adding the square terms of institutional quality improves the fit of some models, as presented within R2. In columns (1) to (8) and (17) to (24), I observe a significant hump-shaped relationship between democracy (polity), participatory democracy, and the degree of fiscal autonomy, instead of fiscal control. From here, I can conclude that as democracy (polity), participatory democracy, and fiscal decentralization are increasing from a low level of development, further increase in the levels of these input-based metrics of institutional quality will further decrease the degrees of fiscal autonomy after both variables reach a peak at 8.1 points and 0.76 point of the polity and V-DEM scales, respectively.

In columns (1) to (8) and (17) to (24), I also find a significant bell-shaped relationship when I investigate the relationship between bureaucratic quality, law and order, and the fiscal autonomy. These associations indicate that increasing levels of bureaucratic quality, as well as law and order, initially enhance the authority of subnational governments. Respectively, after reaching a peak at 3.5 points and 5.1 points of the ICRG scale, these metrics of fiscal decentralization will eventually decline, while bureaucratic quality, as well as law and order, increase.

In Supplementary Table 3, a dynamic panel analysis is included in the estimations to tackle the issue of endogeneity among institution indicators. In this context, the lagged variables of institutional quality and their square terms serve as instruments. Overall, in Equationequation (1)(1)

(1) and (3), I have discovered a hump-shaped relationship between democracy (polity), participatory democracy, and fiscal autonomy. This finding corroborates the previous estimations in Supplementary Table 1, although the turning point is at 7.8 points and 0.73 point of the polity and V-DEM scales, respectively. Additionally, in equation (6) and (7), the variable of bureaucratic quality and law and order creates a bell-shaped relationship with fiscal autonomy, whereby the vertex is at 3.4 points and 4.8 points of on the ICRG scale, respectively. All in all, this relationship is valid and robust, indicated by the high p-value of the Sargan statistic, and it contains no autocorrelation.

6. Discussions

Based on the results from Supplementary Table 1, I suspect that a nonlinear relationship exists between institutional and fiscal decentralization indicators because policy-makers at either side of the range of median Ins faced with other incentives may move the current reform away from decentralization. In this case, I follow Jametti and Joanis’s (Citation2016) method on adding the squared terms of institution variables.

However, previous estimations on Supplementary Table 2 may contain potential issues of endogeneity (see Panizza, Citation1999). Such problems may occur when the degrees of fiscal decentralization determine the institutional level. Empirical studies confirm that fiscal decentralization affects the quality of democracy and governance. On the one hand, fiscal decentralization increases accountability when subnational governments are benevolent (Oates, Citation1972). Even assuming that they are leviathans, interjurisdictional competition will still improve the performance of subnational governments (Brennan & Buchanan, Citation1980).

On the other hand, such competition creates problems of fiscal “overgrazing” and accountability (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1993). For example, if both central and subnational governments have the authority to tax citizens, all parties will have the chance to extort bribes from the same object. Subnational governments may also utilize this competition as a means to evade the power of central government to gather taxes and administer regulations (Cai & Treisman, Citation2004). I can therefore not rely on fixed effects regressions, as I cannot assume these characteristics will remain stable during the period of this study. Thus, Supplementary Table 3 will provide a dynamic panel analysis to rectify the endogeneity issues.

My examination shows that there is an inverted-U association between democracy variables, bureaucratic quality, law and order, and fiscal control. Regarding on the former, such a threshold level of democracy upon which developing countries begin to lower their autonomy can be explained by two factors. First, as explained in the previous section, not only must policy-makers be willing to delegate self-rule and shared-rule to subnational governments, they must deal with political resistance and challenges which may affect the on-going reforms of decentralization. In this context, the current governing party may not be able to retain its power if it loses the election at subnational level (O’Neill, Citation2005). This condition leads to political crises within the national party. For instance, in Venezuela and Brazil, central elites within the ruling party were forced to re-centralize during the 1990s (Montero & Samuels, Citation2004). Moreover, Garman et al. (Citation2001) show that the degree of fiscal autonomy can decrease if the national parties are no longer dominated by subnational elites.

Last, Montero and Samuels (Citation2004) sheds some light on conditions of national fiscal solvency which prevent subnational governments from taxing their local citizens, receiving a significant portion of intergovernmental fiscal transfers from the central government, and spending their resources. These problems could be a primary motive behind re-centralization efforts in Latin American countries. For example, in the 1990s Argentina and Brazil chose to re-centralize in the face of fiscal crisis.

Aside from fiscal crises as well as political resistance and challenges, the decision to re-centralize is caused by other potential scenarios related to governance. Assume that fiscal decentralization improves accountability à la Oates (Citation1972) and government quality à la Kyriacou and Roca-Sagales (Citation2011). Corrupt officials in central governments may pressure policymakers to re-centralize because they want to increase their degree of rent-seeking at the subnational level (Fisman & Gatti, Citation2002). In this context, they may re-negotiate with local elites to expand in a higher rent-extraction sector, while forcing subnational government to remain in a lower rent-extraction area. Also, corruption may alter the composition of public spending; some subnational officials may call on policymakers to re-centralize, as they want to spend more public resources on sectors where they can more easily use bribery, instead of focusing on the best interests of their citizens (Hessami, Citation2014).

7. Conclusion

Fiscal decentralization remains a major agenda point in the policy forums of developing countries. In this essay, I have argued that the degree of fiscal decentralization observed in a developing country depends on its institutional quality. Specifically, based on a simple premise, I expect that better levels of institutions can have a significant effect on the degrees of fiscal decentralization.

I test the model using a panel of 34 developing countries with a five-year average observation between 1990 and 2014. My model indicates the significant and positive effects of institutional quality on fiscal decentralization; the influence of democracy and governance over decisions by subnational governments to independently implement their fiscal authority appears to be unlimited.

Since policy-makers at either side of the range of the median of institutional quality may be susceptible to other incentives to move the direction of policy away from decentralization, the institutional quality—fiscal decentralization nexus can become nonlinear. In this context, the relationship can be well explained in terms of the input or process-based (i.e. democracy) and the output or outcome-based (i.e. bureaucratic quality and law and order) measures of institutional quality.

As democracy (polity), participatory democracy, bureaucratic quality, law and order, as well as the degrees of fiscal decentralization are all rising from low levels of development, a further increase in the levels of these institutional quality variables will further decrease the degrees of fiscal autonomy.

It is important to note that my study implies that the design, nature, and extent of decentralization do not depend solely on whether policy-makers can accommodate political partisans and obstacles. It turns out that other reasons than fiscal crisis may prompt some officials in subnational governments to spend their budgets inefficiently. Moreover, corrupt officials in central governments may resist decentralization because they want to increase their rent-seeking at the subnational level. All in all, future studies must deeply examine the bell-shaped relationship between institutional quality and fiscal decentralization. Future studies must also point out the effects of the interacted terms among institutional quality indicators and the dynamics of population in the sub-national governments (e.g. rural vs urban) on fiscal decentralization indicators. For instance, interacting corruption with democracy and the differences in demographic structure between regional governments may provide additional channels for understanding the self-rule and shared-rule mechanisms of fiscal decentralization.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (256 KB)Acknowledgments

I want to convey immense gratitude to our fellow lecturers at the Department of Management and Public Administration, the University of National, for their valuable comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2234220

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2005). Institutions as the fundamental cause of long-run growth. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of Economic Growth (pp. 385–18). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01006-3

- Alarcón, P., Galais, C., Font, J., & Smith, G. (2019). The effects of economic crises on participatory democracy. Policy & Politics, 47(2), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15407316045688

- Andersen, D., & Krishnarajan, S. (2019). Economic crisis, bureaucratic quality and democratic breakdown. Government and Opposition, 54(4), 715–744. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2017.37

- Arzaghi, M., & Henderson, J. V. (2005). Why countries are fiscally decentralizing? Journal of Public Economics, 89(7), 1157–1189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.10.009

- Azfar, O., Kähkönen, S., Lanyi, A., Meagher, P., & Rutherford, D. (1999). Decentralization, governance and public services: The impact of institutional arrangements. a review of the literature. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTINDONESIA/Resources/Decentralization/Lit_Review_IRIS.pdf

- Bahl, R. W., & Linn, J. F. (1992). Urban public finance in developing countries. Oxford University Press.

- Bardhan, P., & Mookherjee, D. (2006). The rise of local governments: Anoverview. In P. B. In & D. Mookherjee (Eds.), Decentralization and Local Governance in Developing Countries: A Comparative Perspective (pp. 1–52). The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/2297.001.0001

- Bodman, P., & Hodge, A. (2010). What drives fiscal decentralization? Further assessing the role of income. Fiscal Studies, 31(3), 373–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2010.00119.x

- Bojanic, A. N. (2020). The empirical evidence on the determinants of fiscal decentralization. Revista Finanzas y Política Económica, 12(1), 271–302. https://doi.org/10.14718/revfinanzpolitecon.v12.n1.2020.2656

- Brennan, G., & Buchanan, J. (1980). The Power to Tax: Analytical foundation of a fiscal constitution. Cambridge University Press.

- Cai, H., & Treisman, D. (2004). State corroding federalism. Journal of Public Economics, 88(3–4), 819–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-27270200220-7

- Canavire-Bacarreza, G., Martinez-Vazquez, J., & Yedgenov, B. (2016). Reexamining the determinants of fiscal decentralization: What is the role of geography? Journal of Economic Geography, 17(6), 1209–1249. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbw032

- Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Lindberg, S. I., Skaaning, S., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Fish, M. S., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Knutsen, C. H., Krusell, J., Lührmann, A., Marquardt, K. L., McMann, K., Mechkova, V., Olin, M., Paxton, P. … Wilson, S. (2019). V-Dem Dataset – Version 9. Retrieved from https://www.v-dem.net/en/data/data-version-9/

- Dahlberg, S., Holmberg, S., Rothstein, B., Khomenko, A., & Svensson, R. (2016). The quality of government basic dataset – version January 2019. Retrieved from https://qog.pol.gu.se/data/datadownloads/qogbasicdata

- Digdowiseiso, K., Murshed, S. M., & Bergh, S. I. (2022). How effective is fiscal decentralization for inequality reduction in developing countries? Sustainability, 14(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010505

- Ebel, R. D., & Yilmaz, S. (2002). Concept of fiscal decentralization and worldwide overview. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/716861468781761314/pdf/303460Concept0of0Fiscal0Ebel1Yilmaz.pdf

- Elazar, D. (1987). Exploring Federalism. University of Alabama Press.

- Faguet, J. P., & Pöschl, C. (2015). Is decentralization good for development? Perspectives from academics and policy makers. In J.-P. Faguet & C. Pöschl (Eds.), Is Decentralization Good for Development? Perspectives from Academics and Policy Makers (pp. 1–28). Oxford University Press.

- Feld, L. P., Schaltegger, C. A., & Schnellenbach, J. (2008). On government centralization and fiscal referendums. European Economic Review, 52(4), 611–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2007.05.005

- Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002). Decentralization and corruption: Evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83(3), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-27270000158-4

- Garman, C., Haggard, S., & Willis, E. (2001). Fiscal decentralization: A political theory with Latin American cases. World Politics, 53(2), 205–236. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2001.0002

- Haggard, S., & Kaufman, R. (1997). The Political Economy of Democratic Transitions. Comparative Politics, 29(3), 263–283. https://doi.org/10.2307/422121

- Hessami, Z. (2014). Political corruption, public procurement, and budget composition: Theory and evidence from OECD countries. European Journal of Political Economy, 34(2014–6), 372–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.02.005

- Hooghe, L., Marks, G., Arjan, H. S., Sandra, C., Sara, N., & Sarah, S. (2016). Measuring regional authority. Volume I: A postfunctionalist theory of governance. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198728870.001.0001

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2019). Government Financial Statistics. Retrieved from http://data.imf.org/?sk=a0867067-d23c-4ebc-ad23-d3b015045405

- Jametti, M., & Joanis, M. (2016). Electoral competition as a determinant of fiscal decentralization. Fiscal Studies, 37(2), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2015.12061

- Kyriacou, A. P., & Roca-Sagales, O. (2011). Fiscal and political decentralization and government quality. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29(2), 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1016r

- Letelier, L. S. (2005). Explaining fiscal decentralization. Public Finance Review, 33(2), 155–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142104270910

- Litvack, J., & Seddon, J. (1999). Decentralization briefing notes. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/WBI/Resources/wbi37142.pdf.

- Manor, J. (1999). The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralization. The World Bank.

- Montero, A. P., & Samuels, D. J. (2004). The political determinants of decentralization in Latin America. Causes and consequences. In A. P. Montero & D. J. Samuels (Eds.), Decentralization and democracy in Latin America (pp. 3–32). University of Notre Dame Press.

- Murshed, S. M., Badiuzzaman, M., & Pulok, M. H. (2015). Revisiting the Role of the Resource Curse in Shaping Institutions and Growth. Retrieved from https://repub.eur.nl/pub/77766

- Norton, A. (1991). Western European local government in comparative perspective. In R. Batley & G. Stoker (Eds.), Local Government in Europe: Trends and Developments (pp. 21–40). McMillan Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-21321-4_2

- Oates, W. E. (1972). Fiscal Federalism. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- O’Neill, K. (2005). Decentralizing the State: Elections, Parties and Local Power in the Andes. Cambridge University Press.

- Panizza, U. (1999). On the determinants of fiscal centralization: Theory and evidence. Journal of Public Economics, 74(1), 97–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-272700020-1

- Rothstein, B., & Teorell, J. (2008). What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance, 21(2), 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2008.00391.x

- Sepulveda, C., & Martinez-Vazquez, J. (2011). The consequences of fiscal decentralisation on poverty and income equality. Environmental and Planning C: Government Policy, 29(2), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1033r

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1993). Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118402

- Stegarescu, D. (2005). Public sector decentralisation: Measurement concepts and recent international trends. Public Choice, 26(3), 301–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2005.00014.x

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). (2019). SIPRI military expenditure database. Retrieved from https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex.

- Tanzi, V. (2000). On fiscal federalism: Issues to worry about. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/seminar/2000/fiscal/tanzi.pdf

- Tranchant, J. P. (2016). Decentralisation, regional autonomy and ethnic Civil Wars: A dynamic panel data analysis, 1950-2010. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/72750/1/MPRA_paper_72750.pdf

- Uchimura, H. (2012). Introduction. In H. Uchimura (Ed.), Fiscal Decentralization and Development (pp. 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230389618_1

- Wheare, K. C. (1964). Federal Government. Oxford University Press.

- World Bank. (2015). World Development Indicators. Retrieved from http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators