?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The paper examines the effect of trade openness on poverty using the panel Autoregressive Distributive Lag (ARDL) estimation technique from 1980 to 2019 in Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries. The paper focuses on non-income poverty; in this paper, non-income poverty is measured by the human development index since this measure looks at poverty beyond just income. The paper assesses the direct and indirect effects by including the mediating variables in the non-income poverty trade openness model. The study results assist SADC governments and policymakers in addressing poverty reduction policies amid the trade openness era and identifying appropriate complementary policies for reducing poverty in SADC countries. The study’s findings indicate that trade openness reduces non-income poverty (NPOV) in SADC countries in the long run. Again, the empirical results suggest that trade openness reduces NPOV when economic growth and human capital development are high. Yet, trade openness worsens NPOV when income inequality increases. Surprisingly an inconsistent result indicates that a mediating variable of trade openness and financial development has a negative effect on NPOV in SADC countries. This calls for SADC governments and policymaking institutions to revamp the trade opening reform by making economic growth sustainable and inclusive, improving the education system’s quality, maintaining income distribution, and making pro-poor financial systems across the region.

1. Introduction

Trade openness is regarded as a global trend and a prerequisite for development. Even though trade openness is being actively promoted as a significant component in development strategies, theoretically, the impact of trade openness on poverty reduction is logically equivocal. Proponents (Ohlin, Citation1933; Samuelson, Citation1948) of trade openness argue that a more open regime is argued to change relative factor prices in favor of the more abundant factor. Therefore, if poverty and relatively low-income stem from the abundance of labor, greater trade openness should lead to higher labor prices and decreased poverty. Yet critics (Kelbore, Citation2015; Winters et al., Citation2004b) postulate that increases in production due to trade openness are not necessarily sufficient to alleviate poverty. For example, if improved productivity leads to lower input rather than higher output, the short-term outcome could be lower employment and, as a result, more poverty.

Poverty alleviation is one of the most fundamental global objectives of development. Accordingly, Sen (Citation1976, Citation1999) argued that development should focus on individual capabilities rather than economic growth. This increases the trend toward studying the possibility of trade openness to reduce poverty. Amplifying the opportunities, notably less privileged people, is also required for human development (Jawaid & Waheed, Citation2017). According to the World Bank (1996), (Southern African Development (SADC) Secretariat, (Citation2008) (2008), and Castleman et al. (Citation2016), poverty, in very broad terms, is the inability to meet basic needs and encompasses general scarcity. However, the current study focuses on the concept and measurement of poverty from a human development perspective, the coping behavior of the poor, and the impact of trade openness on poverty. Thus, human poverty is distinguished from poverty defined in terms of income or basic needs. Human development is the process of enlarging people’s choices. Human poverty means that people lack the choices and opportunities fundamental to human development: to lead a long, healthy, creative life and to enjoy a decent standard of living (Boer, Citation1997). Human poverty is the absence of the essential capabilities to function and the lack of real opportunity to lead a valuable and valued life because of social constraints as well as personal circumstances.

The reduction of poverty levels has been at the heart of almost every agenda of the various SADC governments since their political independence (Southern African Development SADC Secretariat, Citation2008). Quartey et al. (Citation2007) defined trade openness as the extent to which foreigners and the citizens of a nation can trade without artificial barriers, including governmentally imposed costs, which may arise through delays and uncertainty. Trade openness improves productivity through improved access to new productivity-enhancing technologies, improved intermediate inputs, and increased investment in innovations. Consequently, the reallocation of resources from low to high-productive activities leads to a structural change in the economy (Kelbore, Citation2015; Lucas, Citation1988).

The main objective of this research is to add to the body of knowledge on the trade openness-poverty debate and literature. To increase understanding of the effect of trade openness on non-income poverty in the long run and to check the effectiveness of complementary factors on the trade openness-non-income poverty relationship in SADC countries. This is a departure from existing studies that have analyzed this kind of relationship, assuming that only trading openness matters. Moreover, employing mediating variables in the poverty-trade openness model will allow the non-income poverty-trade openness nexus to vary with some country characteristics. The current study also includes non-income poverty, a term infrequently utilized in the literature on trade openness and poverty.

In doing so, the present study tests the hypothesis that trade openness does not directly and indirectly affect non-income poverty in SADC countries. The alternative hypothesis hypothesizes that trade openness direct and indirect impact non-income poverty in SADC countries. The present paper employs the pooled mean group (PMG) estimation technique, which controls for the possible unobserved country and period-specific effects, the individual or joint endogeneity of explanatory variables with the dependent variable, poverty. This, therefore, control the biases resulting from simultaneous or reverse causation and provides reliable and robust results.

The main result of the current study indicates that trade openness reduces NPOV in SADC countries in the long run. Again, the empirical results suggest that trade openness reduces NPOV when economic growth and human capital development are high. Yet, trade openness worsens NPOV when income inequality increases. The results also indicate that economic growth and financial development reduce non-income poverty. At the same time, human capital index, inflation, and noda negatively and significantly impact non-income poverty in the long run. Yet, income inequality and unemployment have a negative and insignificant effect, while institutional quality has a positive and negligible impact on non-income poverty in SADC countries.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: section two comprises an overview of SADC non-income poverty and trade openness, and section three is a literature review. Section four presents the methodological/theoretical framework of the study, while the empirical results are discussed in section five. Section six concludes the paper.

2. Trade openness and non-income poverty in SADC countries: An overview

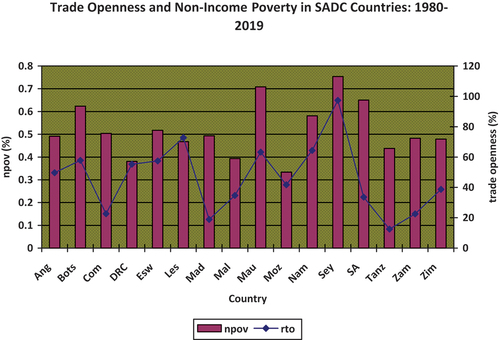

Non-income poverty is one of the most policy priorities of the SADC Secretariat in conjunction with the Social and Human Development Directorate (SHDD). The SADC SHDD aims to reduce human poverty and improve the availability of efficient human resources to promote the region’s economic growth, deeper integration, and competitiveness in the global economy. The SADC has imposed the Regional Indicative Strategic Development Plan (RISDP). This regional framework guides SADC in achieving its development objectives through sustainable economic growth and integration (Southern African Development SADC Secretariat, Citation2008). This plan identifies poverty eradication as the overarching priority of Regional Integration in Southern Africa. As a result, the RISDP also developed the Regional Poverty Reduction Framework (RPRF), which covers critical areas where a regional approach is expected to strengthen national interventions in the fight against poverty. Again, they implemented the SADC’s Regional Poverty Observatory (RPO) to monitor progress towards poverty reduction targets of SADC Member States. The following graphs present the trends in non-income poverty and trade openness in SADC countries from 1980 to 2019.

Figure illustrates the trend in NPOV reduction and trade openness by country in the SADC region. The trend shows that trade openness and NPOV are disparate across the region. Thus 10 out of 16 SADC countries recorded low non-income poverty reduction, which is below the average (0.51%). These include Angola (0.49%), Comoros (0.50%), DRC (0.38), Lesotho (0.47%), Madagascar (0.49%), Malawi (0.39%), Mozambique (0.33%), Tanzania (0.44%), Zambia (0.48%) and Zimbabwe (0.48%). However, the other three countries have recorded trade openness above the average of 49%, even if their non-income poverty reduction is lower. Thus Angola, DRC and Lesotho have a high record of trade openness of 49.7%, 55.3% and 72.8%, respectively, yet the rate at which these countries reduce non-income poverty is lower.

On the other hand, six SADC countries, Botswana, Eswatini, Mauritius, Namibia, Seychelles and South Africa recorded non-income poverty of 0.62%, 0.52%, 0.71%, 0.58%, 0.75% and 0.65%, respectively, which is above the average. Nonetheless, the trend indicates that South Africa’s rate of NPOV reduction is high (0.65%) while the trade openness level is below average between 1980 and 2019. This could be attributed to the South African economy has improved complementary policies (alternatively, better financial institutions, education system, and enhanced institutional quality) than other SADC countries. Figure shows that some countries with higher levels of NPOV reduction have lower trade openness and others with increased trade openness have a lower rate of NPOV reduction. However, the trends above only illustrate the direction of movement for the variables of concern, not the impact. Therefore, there is a need to check the NPOV effect of trade openness in the SADC region.

3. Literature review

Economic theory does not provide a framework for analysing the consequences of trade openness on poverty. The influence of international trade openness on economic growth, on the one hand, and its impact on income distribution, on the other (Bhagwati & Srinivasan, Citation2002; Dollar & Kraay, Citation2001; Dung, Citation2004; Edwards, Citation1992, Citation1998; Nissanke & Thorbecke, Citation2006), has traditionally been used to examine the relationship between trade openness and poverty. Proponents (Dollar & Kraay, Citation2004; Lee, Citation2014; Mamoon, Citation2018; Neutel & Heshmati, Citation2006; Ozcan & Kar, Citation2016; Wangworawong, Citation2016) posit that if trade openness increases economic growth and increases income to a larger extent in favor of the poor, it leads to a better poverty outcome. Given the current focus on fluctuating economic growth and poverty trends in Southern Africa, the relationship will be of primary interest in the present study.

The relationship between trade openness and poverty is linked to Adam Smith’s absolute advantage theory, which stresses the importance of openness to international trade to open the market (Smith, Citation1776). The theory posits that the division of labor and productivity will improve, resulting in a fall in the poverty level of the host country. The gain derived from trade openness is also based on the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage, which states that disparities in factor endowments or technical development across countries cause comparative advantage (Ricardo, Citation1817). As a result, the comparative advantage theory proposes that countries that specialize in producing tradable products and services and have comparative advantages in trading them will increase their overall income and reduce poverty.

Furthermore, the Heckscher-Ohlin theory and its Stolper-Samuelson corollary have long provided a popular paradigm for analysing trade and income distribution in a neoclassical context, explaining the relationship between trade openness and poverty (Heckscher & Ohlin, Citation1991; Ohlin, Citation1933; P. A. Samuelson, Citation1949). As a result, Heckscher and Ohlin (HO) created the factor endowment theory and improved the notion of comparative advantages. According to the HO theory, a country has a comparative advantage in commodities whose production is relatively intensive in the factor with which the country is comparatively well endowed in a two-factor (capital and labor) context (Heckscher & Ohlin, Citation1991). The Stolper-Samuelson corollary states that allowing trade will increase the abundant factor’s real income while decreasing the scarce factor.

The Stolper-Samuelson prediction, if the two factors of production are designated as skilled and unskilled labor rather than labor and capital, is that trade openness to international trade will reduce poverty by increasing the real income of unskilled-workers relative to skilled workers in unskilled-labor-abundant countries while increasing wage inequality in skilled-labor abundant countries (Kabadayi, Citation2013; Le Goff & Singh, Citation2014; Neutel & Heshmati, Citation2006). Furthermore, the endogenous growth theories (Lucas, Citation1988; Romer, Citation1986) propose that trade openness boosts productivity through the diffusion of technology, dissemination of new knowledge, inflows of information, technical skills, competition in intermediate and capital products, and economies of scale benefits. As a result, all free-market economy arguments are in consensus that the open market economy is generally preferable.

Nonetheless, modifications from (2002) and Kelbore (Citation2015) contend that trade openness does not necessarily reduce poverty because of income disparities. Furthermore, according to Winters et al. (Citation2004b), increases in production due to trade openness are not necessarily sufficient to alleviate poverty. For example, if improved productivity leads to lower input rather than higher output, the short-term outcome could be lower employment and, as a result, more poverty. Again, Winters (Citation2004a) argues that trade openness affects poverty through price transmission, depending on whether the poor household is a net producer or a net consumer of the commodity whose price has changed. As a result, when individuals are considered a heterogeneous group, price variations will affect different income groups. Winters (Citation2004a) and Nissanke and Thorbecke (Citation2008) suggest that, in terms of wages and employment, a developing economy is not always a country that will have comparative advantages in unskilled labor. It could also have additional advantages, such as raw resource extraction and medium or high-skilled labor, ostensibly assisting the poorest. Therefore, openness to international trade can increase the wages of medium or highly-skilled workers, but not for totally unskilled labor.

Empirical studies support trade openness to have a negative impact on non-income poverty. However, other studies argue that trade openness exacerbates non-income poverty. For example, Davies and Quinlivan (Citation2006), Kabadayi (Citation2013), Kumar (Citation2017) and Jawaid and Waheed (Citation2017) employ different estimation techniques in different places at different periods of study. Yet, they document the favorable effect of trade openness on non-income poverty. Nonetheless, other studies argue that trade openness worsens NPOV.

Pradhan and Mahesh (Citation2014) assessed trade openness’s effect on developing countries’ poverty. The study indicated that trade openness reduces poverty in developing countries. Pradhan and Mahesh (Citation2014) also suggest that education reduces poverty in developing economies. This result is consistent with Le Goff and Singh (Citation2014), who claimed that trade openness is a poverty-reducing factor in African countries. Even if Le Goff and Singh (Citation2014) considered the interaction terms, the study included the commonly used (income poverty) measure of poverty. Again, the study assessed the short-run effects only. At the same time, a literature survey by (Mamoon, Citation2018) suggests that trade can reduce poverty but worsens income inequality. Thus trade -poverty reduction policies should consider investment in education at all levels to improve the more favorable effect of trade openness on poverty. Given the above argument, the current study considers income inequality and education level (measured by the human capital index) as interaction terms in the trade openness nexus in SADC countries.

The studies (Ezzat, Citation2018; Onakoya et al., Citation2019) used different measures of non-income poverty and estimation techniques in different regions, but they show that trade openness exacerbates non-income poverty. Thus Ezzat (Citation2018) assessed the effect of trade openness on non-income poverty in MENA countries from 1995 to 2015 using the GMM estimation technique. The study supports that trade openness restricts the efforts to alleviate multidimensional poverty and its intensity in MENA countries. Again, Onakoya et al. (Citation2019) analysed the effect of trade openness on poverty as measured by the human development in 21 African countries from 2005 to 2014 using the panel data estimation (fixed effect, Driscoll-Kraay) technique. The findings reveal that trade openness is negatively related to poverty.

Adegboyo et al. (Citation2021) also indicate that trade openness reduces poverty. This study also suggests that Nigeria’s financial development and education are poverty reduction factors. The general methods of moments analysis in Fambeu (Citation2021) indicate that democracy and trade openness reduce poverty. Thus, democracy and trade openness should be considered simultaneously to enhance their impact on poverty reduction. Therefore, the current study also includes the institutions’ role in the trade openness-poverty association in SADC countries.

Yameogo and Omojolaibi (Citation2021) assessed the effect of trade openness on economic growth on poverty in sub-Saharan Africa using panel ARDL, panel vector auto-regression (VAR), and system generalized methods of moments (SGMM estimation) techniques from 1990 to 2017. The study indicates that trade openness increases economic growth in the long run. Yet, trade openness and institutional quality only reduce poverty in the short run. Even if the study included the economic growth and institutional quality in the poverty-trade model, it does not show the role of the said factors in the trade openness and poverty nexus as it only considered the direct effects.

The above exposition indicates that the literature on trade openness and poverty focused much on income poverty and the direct effect of trade openness on poverty. Once more, the studies gave short-term analysis a higher priority than long-term analysis. In addition, the studies looked at the relationship between trade openness and poverty in a wide range of countries, such as developing countries and African economies, in one panel, which may have different developmental objectives and challenges. As a result, the current paper reevaluates how trade openness affects poverty, taking into account the non-income poverty measure and considering both long- and short-term effects. Again, another crucial objective and contribution of the current study are to look into the role of vital complementary factors (such as level of education, income inequality, and financial development) in the trade openness-poverty nexus. Assessing the indirect effects through interaction terms will help trade openness policymakers recognize the significance of the mediatory factors in the relationship between trade openness and poverty in the region. In doing so, the current study tests the following hypotheses:

Trade openness does not directly and indirectly, affect non-income poverty in SADC countries.

Trade openness direct and indirect impact non-income poverty in SADC countries. The following section presents the theoretical framework of the study.

4. Theoretical framework

This paper empirically examines trade openness’s direct and indirect effect on poverty in 16 SADC countries between 1980 and 2019 using the panel ARDL estimation technique. The non-income poverty in the current study is measured by human development (HDI). The trade openness-non-income poverty model was adapted from (Le Goff & Singh, Citation2014), who assessed the impact of trade openness and poverty in Africa. Their empirical model is expressed as follows:

Where Poverty is the log of a poverty indicator, where the subscripts and

represent country and period, respectively,

is the matrix of control variables,

is a measure of trade openness,

corresponds to time effects,

denotes unobserved country-specific effects, and

The error term.

represents the interaction terms incorporating trade openness with each complementary variable (financial depth, education, and governance).

Even if Le Goff and Singh (Citation2014) used the interaction terms, the study does not consider long-run analysis. Again, Le Goff and Singh (Citation2014) employed the commonly used measure of poverty: income poverty. The current study considers non-income poverty as measured by the human development index, which looks at poverty measures beyond just income (United Nations, World Bank PRB). This measure was also used by Onakoya et al. (Citation2019), to assess the link between trade liberalization and poverty in African nations between 2004 and 2015.

Dollar and Kraay (Citation2001), Dung (Citation2004) and Alcala and Ciccone (2004) emphasised that economic growth is essential and significant for discussion about the poverty effect of trade openness. Again, Nissanke and Thorbercke’s (2010) trade openness-poverty transmission mechanism indicates that trade openness influences poverty through income inequality. Therefore, the current paper also considered the indirect effect of trade openness on poverty through economic growth and income inequality by using interacting terms on the trade openness-poverty model. Therefore, the interacting term for the non-income poverty model for the current study incorporated trade openness and economic growth and trade openness and income inequality. Furthermore, Le Goff and Singh (Citation2014) prompts that trade openness affects poverty through education and financial depth. This is in line with Chang et al. (Citation2009), who ascertain that openness to international trade reduces poverty if accompanied by supporting policies that could help better harness these benefits. Thus, the current research also includes interacting terms of trade openness with economic growth, financial development, human capital index and institutional quality to determine whether the trade openness-poverty link is conditional or deterministic.

It should be noted that poverty could be interrelated with economic growth and income inequality in a complex way. Furthermore, non-income poverty may affect economic growth because of the possibility of a poverty trap. Therefore, establishing a good specification for poverty could be challenging because of endogeneity and reverse causality. As a result, the current paper considers the dynamic panel data estimation technique to control endogeneity bias reverse causality in the poverty model. Using a sample of 40 years and 16 SADC countries implies that the time dimensions are greater than the cross-sectional dimensions, so the panel ARDL estimation techniques (such as pooled mean group, dynamic fixed effect, and mean group) are more efficient and consistent compared to the GMM, which could be biased due to instrumental proliferation (Roodman, Citation2009; Shin et al., Citation1998). The poverty model for this study in Equation 1 is transformed into a reparameterised ARDL (p, q … . q) (pooled mean group) model. Thus, the non-income poverty model is specified as follows:

Where:

is the log of non-income poverty variable measured by the human development index, which denotes poverty reduction and the NPOV is the dependent variable. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (Citation1990), the HDI is defined as an improvement in the lives of individuals. Boer (Citation1997) advocates that the HDI captures the well-being of the people since the people are the ultimate objective of development. Human development includes enlarging people’s choices by enhancing their functioning and capabilities. These include human capital formation and human resources development through health, living standards and education. This implies that the HDI consists of three dimensions: education, health, and living standard (Beegle et al., Citation2016). This measure was used by Onakoya et al. (Citation2019) to capture the poverty reduction indicator in their analysis of trade openness and poverty in African countries.

The represents the explanatory variables and are allowed to be purely 1(0) or 1(1). The explanatory variable includes the main independent variable, the real trade openness, and the control variables, consisting of the interacting and country-specific variables. Thus,

represents interacting terms where economic growth (LRTOLRGDP);, income inequality (LRTOLINEQ), human capital (LRTOLHIND), financial development (LRTOLFD), and institutional quality (LRTOLPS) are embedded as variables that mediate the trade openness-non-income poverty nexus.

The country-specific variable consists of economic growth (LRGDP), income inequality (LINEQ), human capital index (LHIND), financial development (LFD), inflation (LINFL), unemployment (LUNEM), and noda (LNODA). The and

are the vectors of a long-run relationship.

is the adjustment coefficient,

is the error correction term which represents the long-run information of the model. The error correction model comes with a different operator for the dependent variable. Meaning that once the ARDL is differenced, there will be a loss of lag length. Therefore, the lag length is now p-1 and q-1

and

are short-run parameters.

and

denote the unit-specific fixed effects and the error term, respectively. Thus, the trade openness variable in the case of NPOV is expected to be positively related to non-income poverty (poverty reduction). Economic growth is expected to be positively associated with non-income poverty. Again, this paper’s human capital index (education) is likely to relate to poverty reduction positively. Unemployment is expected to worsen NPOV in SADC countries. The NODA is expected to positively affect poverty reduction in SADC countries.

The panel autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimation techniques consist of the mean group (MG), dynamic fixed effect (DFE) and pooled mean group (PMG) estimator. Unlike the DFE and MG, the PMG developed by Pesaran et al. (Citation1997) and explained by Shin et al. (Citation1998, 1999) is a more informative and intermediatery method between new and traditional estimators. The PMG approach estimates regression for each observation. Then it averages them across countries so that the short-run coefficient, error term, and intercept are different across units but similar across countries (Anjum &Perviz, Citation2016; Guei & le Roux, Citation2018). The KPMG also accounts for unobserved common factors, robust to non-stationarity cointegration. It addresses the issue of endogeneity by expanding the parameters with lags of the explanatory variables. This helps to reduce the bias of the estimators and ensure that the regression residuals are uncorrelated and are distributed independently of the regressors, which means that the regressors can be treated as exogenous. In doing so, the PMG is the most preferred estimator in the current study.

Meanwhile, the effect of heterogeneity on the means of the coefficients can be determined by the Hausman (Citation1978) test applied to the difference between the DFE, MG and PMG (Pesaran et al., Citation1997). Thus, the PMG estimators limit the long-run elasticities to be equal across all groups and this may give consistent and efficient estimates across countries. Meaning that if the model is heterogeneous, then MG estimates are consistent in either case. However, PMG estimates are inconsistent. Therefore it is also essential to test and verify the suitability and significance of the PMG estimator relative to the MG and DFE estimators based on the consistency and efficiency properties of the two estimators, using a likelihood ratio test or a Hausman (Citation1978) test.

Thus, the study utilises the Hausman (Citation1978) test to decide between the MG and PMG. The null hypothesis is that the MG and PMG estimates are not significantly different, meaning the PMG is more efficient under the null hypothesis. The null and alternative hypotheses of the Hausman test are given as follows:

: MG and PMG are not significantly different, and the PMG is more efficient

: the null is not true

Therefore, the decision will be not to reject the null hypothesis and use the PMG if the probability (p) value is greater than 0.05% and reject the null hypothesis in favor of the MG if the p-value is less than 0.05%. The Hausman (Citation1978) test can also be used to determine between DFE and PMG with the following hypothesis:

: DFE and PMG estimates are not significantly different, and the PMG is more efficient

: null is not true

Therefore, the decision criteria are that if the p-value is greater than 5%, one cannot reject the null hypothesis, thereby using the PMG as the appropriate estimator. However, if the p-value is less than 5%, the null hypothesis should be rejected in favor of the DFE estimator

5. Presentation and discussion of results on npov

This section presents, discuss and analyse empirical results of the relationship between trade openness and NPOV and associated diagnostics. The section presents the preliminary result, including the descriptive statistics and unit root test results in Tables . The correlation coefficient results, and the lag length selection are presented in appendices 1 and 2. The correlation coefficient matrix (see appendix 1) shows that the explanatory variables are not highly correlated, so they are not linearly dependent. Therefore, they can be included in the same regression model. The common lag length (see appendix 2) for all other variables used to analyse trade openness and poverty reduction is 1, except unemployment and noda, which use lag 0. Table presents the characteristics of the data used in the current paper.

Table 1. Definition of variables

The descriptive statistic (see Table ) indicates that the SADC NPOV reduction increased as the HDI improved at an average of 50 between 1980 and 2019. Most importantly, the descriptive statistics show the standard deviations, which show the variations in the sample. Except for income inequality (ineq), the standard deviation for all other variables of concern is large enough to explore the variance in the data.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Table presents the Im Persaran and the ADF unit roots test results. The results show that other variables are stationary at first difference 1(1) and not stationary at levels 1(0), while other variables are stationary at both levels and first difference. The Im Pesaran indicates that economic growth, inflation, financial development and noda are stationary at levels. However, trade openness, income inequality, human capital index, and unemployment are stationary at first difference. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test indicates that all other variables are stationary at levels except NPOV, trade openness, human capital index, institutional quality and noda.

Table 3. Unit root test results

Before proceeding with the analysis, the study checked for panel homogeneity across the cross sections of the dataset. In that pursuit, the paper utilized the Friedman and Pesaran cross-sectional dependence test (Asteriou & Hall, Citation2016; Gujarati & Porter, Citation2010). The results (see appendix 4) indicate that the variables are cross-sectionally dependent, rejecting the panel homogeneity hypothesis. With this evidence, the current paper proceeded to check the integration properties of the variables using second-generation unit root tests, which assume the presence of cross-sectional dependence among model variables of interest (Camarero et al., Citation2016; Hurlin & Mignon, Citation2007; Sharma et al., Citation2021). The second-generation unit root test (CIPS and CADF) (see last two columns in Table ) show that few variables exhibit significance at levels, and all variables are stationary at first difference. This implies that all the variables under study are 1(1). This is the same conclusion as the first-generation unit root test results. To ensure the model’s stability, efficiency, and robustness, the model is estimated with log differences system variables. The current paper also employs the panel ADRDL estimation technique(PMG), which is efficient and consistent since it considers two different equations (differenced and level forms) in one model (Asteriou & Hall, Citation2016; Gujarati & Porter, Citation2010; Shin et al., Citation1998).

The empirical results on trade openness’s direct and indirect effect on non-income poverty in SADC countries over the short- and long-run are in Tables , respectively. Based on the Hausman (Citation1978) decision criterion, the PMG is the appropriate estimation technique for the current research because the p-value in all tests is greater than 0.05% (see appendix 3). The benchmark trade openness measure-NPOV results are presented in the first columns (Model 1). The current paper considers the two benchmark interaction terms: trade openness and economic growth (Model 2) and trade openness and income inequality (Model 3). Again, other interaction terms, including the human capital index (Model 4), financial development (Model 5), and institutional quality (Model 6), are also included to capture the economy ‘s ability to reallocate resources away from less productive sectors to the more productive ones and hence take advantage of the opportunities offered by greater openness to international trade. The speed of adjustment (ECT) is shown in the first row of each short-run coefficient in Table . This implies that no-income poverty and the regressors are cointegrated.

Table 4. Short-run PMG estimation results: real trade openness and non-income poverty

Table 5. Long-run PMG estimation results: real trade openness and non-income poverty

The empirical results in Table show that real trade openness has a positive and insignificant effect on non-income poverty over the short term. Yet, economic growth and financial development are positive and significant effects on poverty reduction in the short run. Again, the empirical findings indicate that inflation worsens non-income poverty in the short run. Thus, a 1% increase in inflation is associated with a 0.001% decrease in non-income poverty reduction at a 5% significant level, ceteris paribus. The following table presents the long-run effects of real trade openness on non-income poverty.

Model 1 in Table indicates that trade openness directly increases poverty reduction over the long run in SADC countries. Thus a 1% increase in trade openness increases poverty reduction by 0.02% at a 5% significance level holding other things constant. This result is consistent with Kabadayi (Citation2013), who argued that trade openness positively affects poverty reduction in developing countries. Other variables that directly increase poverty reduction include economic growth and financial development. Thus, a 1% increase in economic growth and financial development increases poverty by 0.01% and 0.1% at a 1% significance level. Yet, these variables become negative after controlling for the interaction term of trade openness and economic growth. This implies that, with trade openness, economic growth increases as few individuals accumulate more capital. As a result, only a few benefit from trade gains, while some inequalities in capital accumulation deprive the poor of gaining from trade openness, thereby compromising poverty reduction in SADC countries.

However, a 1% increase in the human capital index reduces poverty reduction by 0.1% at a 1% significance level. This indicates that the SADC governments should minimize inequalities in the education system by increasing conditional cash/scholarship support, improving student health, and access to credit for education. Again, a percentage increase in inflation and noda also reduces poverty reduction by 0.02% and 0.01% at 1% and 5% significance levels, respectively, holding other things constant in SADC countries. The negative impact of the Net Official Development Assistance (NODA) can be explained by some forms of foreign aid serving developed donor countries’ interests rather than improving the conditions of developing recipient countries. For instance, the donors target foreign aid to areas where potential spillovers to the donors are high. This, in turn, harms developing countries. Income inequality and unemployment have a negative but insignificant effect on poverty reduction. However, the unemployment rate is statistically significant and negatively related to non-income poverty after controlling for the interaction of trade openness and economic growth. This implies that lack of employment and job creation hinders any effort to reduce poverty. This highlights the importance of the employment effect of the labor market channel to link openness to alleviate non-income poverty and its intensity in the SADC countries over the long run.

Looking at the conditional/indirect effect of trade openness on poverty reduction, Table indicates that economic growth benefits the trade-poverty reduction link, which means that increasing economic growth improves the beneficial impact of trade openness on poverty reduction in SADC countries. This is consistent with Bhagwati and Srinivasan’s (Citation2002) and Nissanke and Thorbecke’s (2009) hypothesis that trade openness promotes economic growth and economic growth reduces poverty. Also, the interaction of trade openness and economic growth is supported by Fukase (Citation2010), who argued that the increased economic growth as a result of trade openness stimulates countries to invest more in human capital to improve human capital productivity and support comparative advantage, which increases the alleviation of non-income poverty by increasing human capital development, health and living standards.

Models 4 and 5 indicate the role of human capital development (education) and financial development in the trade openness-poverty relationship. The empirical findings suggest that the interaction of human capital (Model 4) and financial development (Model 5) is detrimental to the trade openness-poverty reduction link. This implies that there are still inequalities in the education and financial systems where only a few individuals can access appropriate quality education and financial liberty to accumulate skills and expertise, compromising their participation in the economy. The negative effect of human capital and financial development is in line with (Galor and Zeira (Citation1993), who advocate that the imperfections and indivisibilities in the investment in human capital and the capital market imperfections capital, which increase borrowing constraints deprive the less privileged from investing in skills and education, which compromise their future income earnings. This means that financial market imperfections, such as inadequate information, transaction costs, and contract enforcement costs, may be binding, especially on poor entrepreneurs who lack collateral, credit histories, and connections. Such credit constraints could impede the flow of capital to poor individuals with high-return projects, thereby intensifying poverty in the region. The interaction of trade openness and institutional quality (Model 6) is negligible in explaining variations in poverty reduction in SADC countries. The following table presents the empirical findings of the effect of economic globalisation on poverty reduction in SADC countries.

5.2. Diagnostic tests

The diagnostic tests for the non-income poverty model are presented in Table . The diagnostic tests consist of DW, supported by the BG serial correlation test and the White heteroscedasticity test. The results of the CUSUM stability test are presented in the last column of Table and Figure .

Figure 2. Plot of CUSUM of squares: Trade openness and non-income poverty analysis.

Table 6. Diagnostic test results: trade openness and non-income poverty

Diagnostic test results in Table indicate that three countries under Durbin Watson and one country under B-Godfrey suffer serial correlation and no evidence of autocorrelation in 12 out of 16 countries. The white test statistics for all the countries are insignificant, meaning there is no heteroscedasticity in all 16 groups. Regarding constancy, the stability of the selected ARDL model specification is evaluated using the CUSUM of the recursive residual test for structural stability, as shown in Figure .

The plot of the CUSUM in Figure reveals that the null hypothesis of parameter stability is not rejected at the 5% significance level. The plots for recursive residuals’ cumulative sum (CUSUM) are satisfactory. As displayed in Figure , there is no movement outside the 5% critical lines of parameter stability in the residual plots for 15 out of 16 countries, meaning that the models for poverty reduction are stable. The following section presents the empirical results of the effect of trade openness on income poverty in SADC countries. The following section focuses on the summary, conclusion, policy implications and recommendations, and areas of further research on trade openness and economic growth, income inequality, and poverty in SADC countries.

6. Conclusion and policy recommendations

The current study examined the effect of trade openness on non-income poverty using the PMG estimation technique in SADC countries from 1980 to 2019. The preliminary tests accompanied the empirical results, including descriptive statistics and correlation, unit root, lag length selection, and the Hausman test. The descriptive statistics show that the standard deviation is large enough to explore the variance in the data. Again, all the explanatory variables have passed the correlation coefficient test, meaning they are not linearly dependent on each other. Moreover, the stationarity test indicates that other variables are not integrated in the same order, so it is desirable to use PMG, as confirmed by the Hausman test. The Durbin Watson and B-Godfrey tests indicate no evidence of autocorrelation in 12 out of 16 countries. Again, the White Heteroskedactisity test suggests that no heteroscedasticity exists in all 16 groups. In terms of constancy, the stability of the selected ARDL model specification is evaluated using the CUSUM of the recursive residual test for structural stability shows that the models for non-income poverty-trade openness are stable.

The empirical results show that trade openness is insignificant in explaining NPOV changes in the short run. Yet other variables, such as economic growth and financial development, promote poverty reduction in the short and long-run. Besides, the inflation rate is detrimental to NPOV in both the short and long run. On the other hand, human capital development and NODA worsens NPOV in the long run. The empirical findings indicate that trade openness increases non-income poverty reduction when economic growth and human capital development are high.

On the other hand, the PMG estimation results show that trade openness reduces NPOV when income inequality increases. Surprisingly, the empirical findings indicate that the complementary variable of trade openness and financial development negatively affects NPOV reduction. In addition, the results of the PMG indicate that inclusive economic growth, equal income distribution, quality education systems, stronger financial institutions and institutional quality should be taken into account by the SADC governments and policymakers to improve the beneficial effect of trade openness on poverty reduction in SADC countries.

Thus, the current study’s empirical findings indicate that trade openness has the potential to lower poverty in SADC countries. Again, the empirical results suggest that it is not only trading openness that matters in poverty reduction. Therefore, the empirical findings call for consideration of accompanying policies (such as equal income distribution, education quality, efficient and stronger financial sector and more vital institutions) when addressing trade openness-income poverty reduction policies. Thus, by improving education levels and quality rise, so will the adoption of trade-based economic activities. More vital financial institutions will also enable everyone to participate in trade openness initiatives, increasing productivity and efficiency. Effective institutions will improve financial and economic freedom, ensuring no one is left behind in gaining advantages from trade openness. In addition, increasing income equality will enable SADC citizens to benefit from trade, thereby reducing poverty in the region. As a result, the study recommends the SADC governments and policymakers focus more on addressing the aforementioned complementary factors to improve the beneficial effects of the trade-poverty reduction policy.

Assessment of poverty in developing countries is one of the most challenging tasks because of poverty data scarcity in most developing countries, such as SADC. However, this did not compromise the results of the current paper since the study considered available measures and a proxy of non-income poverty. The study calls for SADC governments to take poverty data gathering more seriously to advance research and development in the field and enhance the implementation of more practical and effective policies for reducing poverty in the region.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adegboyo, O. S., Efuntade, O. O., Olorunleke, D., & Olugbamiye, A. O. E. (2021). Trade openness and poverty reduction in Nigeria. EuroEconomica, 2(2), 211–22. https://dj.univ-danubius.ro/index.php/EE/article/view/1473

- Anjum, N., & Perviz, Z. (2016). Effect of trade openness on unemployment in case of labour and capital abundant countries. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 5(1), 44–58. https://bbejournal.com/index.php/BBE/article/view/248

- Asteriou, D., & Hall, S. G. (2016). Applied econometrics (3rd ed.), Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-41547-9_1

- Beegle, K., Christiaensen, L., Dabalen, A., & Gaddis, I. (2016). Poverty in a rising Africa. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0723-7

- Bhagwati, J., & Srinivasan, T. (2002). Trade and poverty in the poor countries. American Economic Review Paper and Proceedings, 99(2), 180–183. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802320189212

- Boer, L. (1997). Review: Human development to eradicate poverty reviewed work (s): Human development report 1997 by united nations development programme. Third World Quarterly, 18(4), 777–779. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436599714768

- Camarero, M., D’Adamo, G., & Tamarit, C. (2016). The role of institutions in explaining wage determination in the Eurozone: A panel cointegration approach. International Labour Review, 155(1), 25–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12004

- Castleman, T., Foster, J. E., & Smith, S. C. (2016). Person equivalent headcount measures of poverty. Inequality and Growth: Patterns and Policy, 9402, 101–130. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137554543_3

- Chang, R., Kaltani, L., & Loayza, N. V. (2009). Openness can be good for growth: The role of policy complementarities. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.06.011

- Davies, A., & Quinlivan, G. (2006). A panel data analysis of the impact of trade on human development. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35(5), 868–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2005.11.048

- Dollar, D., & Kraay, A. (2001) Trade, growth, and poverty. Available at: SSRN 632684.

- Dollar, D., & Kraay, A. (2004). Trade, growth, and poverty. The Economic Journal, 114(493), F22–F49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2004.00186.x

- Dung, C. (2004) The impacts of trade openness on growth, poverty, and inequality in Vietnam: Evidence from cross-province analysis, Afse.Fr. Paris. Available at: http://www.afse.fr/docs/cao_xuan.pdf.

- Edwards, S. (1992). Trade orientation, distortions, and growth in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 39(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(92)90056-F

- Edwards, S. (1998). Openness, productivity, and growth: What do we really know? The Economic Journal, 108(447), 383–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00293

- Ezzat, A. M. (2018) Trade openness: An effective tool for poverty alleviation or an instrument for increasing poverty severity. 1248. Dokki, Gizza. Available at: www.erf.org.eg.

- Fambeu, A. H. (2021). Poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa: The mixed roles of democracy and trade openness. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 30(8), 1244–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2021.1946128

- Fukase, E. (2010). Revisiting linkages between openness, education and economic growth: System GMM approach. Journal of Economic Integration, 25(1), 193–222. https://doi.org/10.11130/jei.2010.25.1.194

- Galor, O., & Zeira, J. (1993). Income distribution and macroeconomics. Review of Economic Studies, 60(1), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297811

- Guei, K. M., & le Roux, P. (2018). Trade openness and economic growth: Evidence from the economic community of Western African States region. Journal of Economics and Financial Sciences, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/jef.v12i1.402

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2010). Essentials of econometrics (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill International.

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46(6), 1251–1271. Available at. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1913827%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=econosoc.%5Cnhttp://www.jstor.org

- Heckscher, E. F., & Ohlin, B. (1991). Heckscher-ohlin trade theory, translated, edited and introduce by Harry Flam and M. Flanders. Mass., MIT Press.

- Hurlin, C., & Mignon, V. (2007) ‘Second generation panel unit root tests to cite this version: HAL Id: Halshs-00159842 second generation panel unit root tests’, pp. 1–25. Available at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00159842.

- Jawaid, S. T., & Waheed, A. (2017). Contribution of international trade in human development of Pakistan. Global Business Review, 18(5), 1155–1177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972150917710345

- Kabadayi, B. (2013). Human development and trade openness: A case study on developing countries. Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 3(3), 193–199. https://ideas.repec.org/a/spt/admaec/v3y2013i3f3_3_12.html

- Kelbore, Z. G. (2015). Trade openness, structural transformation, and poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from Africa. University Library of Munich Germany. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/65537/1/MPRA_paper_65537.pdf

- Kumar, S. (2017). Trade and human development: Case of ASEAN. Pacific Business Review International, 9(12), 1–10. http://www.pbr.co.in/2017/2017_month/June/07.pdf

- Lee, K.-K. (2014). Globalization, income inequality and poverty: Theory and empirics. Economics, 28(3), 109–134. https://www.ritsumei.ac.jp/acd/re/ssrc/result/memoirs/kiyou28/28-05.pdf

- Le Goff, M., & Singh, R. J. (2014). Does trade reduce poverty? A view from Africa. Journal of African Trade, 1(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joat.2014.06.001

- Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

- Mamoon, D. (2018). When is trade good for the poor? Evidence from recent literature. Journal of Economics Bibliography, 5(1), 1–4. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327972177

- Neutel, M., & Heshmati, A. (2006). Globalisation, inequality and poverty relationships: A cross country evidence. IZA Discussion Paper.

- Nissanke, M., & Thorbecke, E. (2006). The impact of globalization on the world's poor:Transmission mechanisms: studies in development economics and policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Nissanke, M., & Thorbecke, E. (2008). Introduction: Globalization-poverty channels and case studies from Sub-Saharan Africa. African Development Review, 20(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2008.00174.x

- Ohlin, B. G. (1933). Interregional and international trade. Harvard University Press.

- Onakoya, A., Johnson, B., & Ogundajo, G. (2019). Poverty and trade liberalization: Empirical evidence from 21 African countries. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraå¾ivanja, 32(1), 635–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2018.1561320

- Ozcan, G., & Kar, M. (2016). Does foreign trade liberalization reduce poverty in Turkey? Journal of Economic and Social Development, 3(1), 157. https://hrcak.srce.hr/file/368001

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1997). Pooled estimation of long -run relationships in dynamic heterogenous panels (p. 9721). Department of Applied Economics, University of Cambridge.

- Pradhan, B. K., & Mahesh, M. (2014). Impact of trade openness on poverty: A panel data analysis of a set of developing countries. Economics Bulletin, 34(4), 2208–2219. Available at. http://proxy.library.carleton.ca/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1761435410?accountid=9894%5Cnhttp://wc2pu2sa3d.search.serialssolutions.com/?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2004&ctx_enc=info:ofi/enc:UTF-8&rfr_id=info:sid/ProQ:econlit&rft_val_fmt=info:ofi/fmt

- Quartey, P., Aidam, P., & Obeng, C. K. (2007) The impact of trade liberalization on poverty in Ghana. Retrieved from www.gtap.agecon.purdue.edu.

- Ricardo, D. (1817). Principles of political economy and taxation. John Murray.

- Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037. Retrieved from http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics & Stata, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Samuelson, P. (1948). International trade and equalisation of factor prices. The Economic Journal, 58(230), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.2307/2225933

- Samuelson, P. A. (1949). International factor-price equalisation once again. The Economic Journal, 59(234), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.2307/2226683

- Sen, A. (1976). Poverty: An ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica, 46(2), 219. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912718

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Clarendon Press.

- Sharma, G. D., Shah, M. I., Shahzad, U., Jain, M., & Chopra, R. (2021). Exploring the nexus between agriculture and greenhouse gas emissions in BIMSTEC region: The role of renewable energy and human capital as moderators. Journal of Environmental Management, 297(May), 113316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113316

- Shin, Y., Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. P. (1998). Discussion paper series number 16 pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Economics, 44(16), 1–27. https://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/redir.pf?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.econ.ed.ac.uk%2Fpapers%2Fid16_esedps.pdf;h=repec:edn:esedps:16

- Smith, A. (1776). ‘Adam Smith. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. The Glasgow Edition of theWorks and Correspondence of Adam Smith, II, 743. https://doi.org/10.2307/2221259

- Southern African Development (SADC) Secretariat. (2008) Regional economic integration: A strategy for povery eradication towards sustainable development. Retrieved July 8, 2018, from https://www.sadc.int/themes/poverty-eradication-policy-dialogue/.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (1990). Human development report. https://doi.org/10.18356/7007ef44-en

- Wangworawong, C. (2016). Governance, openness, and economic performance in Asia. Academic Services Journal, 27(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.14456/asj-psu.2016.10

- Winters, L. A. (2004a). Trade liberalisation and economic performance: An overview. The Economic Journal, 114(493), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0013-0133.2004.00185.x

- Winters, L. A., Mcculloch, N., & McKay, A. (2004b). Trade liberalisation and poverty: The evidence so far by. Journal of Economic Literature ,42(1), 72–115. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205104773558056

- Yameogo, C. E. W., & Omojolaibi, J. A. (2021). Trade liberalisation, economic growth and poverty level in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 34(1), 754–774. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1804428