?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Especially for developing countries like Ethiopia, saving is more significant to build capital required to generate income, smooth domestic cash requirements, and allow the ease of consumption during scarcity. However, rural saving at the household level was not substantially investigated in Ethiopia in general and in the study area in particular. The current study, therefore, assessed rural households’ saving status and its determinant factors in Gimbo district, south west region of Ethiopia. Out of the entire sample households surveyed, more than half (52.35%) of the surveyed households were non-saver. This is to mean that a lesser proportion of the sampled households were saving their income left from food and non-food spending or other expenses at formal financial institutions. When we look at the intensity of saving, the whole sampled households saved 4,788.15 ETB on average. As both logit and multiple linear regression model results showed, the education level of the household head, distance from financial institutions, farm income, financial literacy, and participation in non-farm activities were found to affect both decision to save and intensity of saving significantly and positively except distance from financial institutions, which is negatively correlated with both. Therefore, to overcome negative effects of distance from financial institutions, the study recommend the expansion of financial institutions up to kebele levels as much as possible. Moreover, policymakers and other concerned bodies responsible for the enhancement of rural private saving should have to amend rural households’ farm income, education, financial literacy, and participation in non-farm activities.

1. Introduction

Saving is the remaining income after deducting current spending over a given time, which leads to an accumulation of wealth that enables people to improve their living standards and respond to new opportunities (Wieliczko et al., Citation2020b). It is critical to build capital required to generate income, smooth domestic cash requirements, and allow consumption during scarcity (Kuma et al., Citation2019; Leto, Citation2016). It allows farming households to guarantee financial security in the case of unexpected events (Wieliczko et al., Citation2020a). As per classical economists’ thought and various studies, saving was admitted as an important predictor of economic growth (Dong et al., Citation2021; Million & Belay, Citation2019). Furthermore, it is also crucial for capital accumulation and has a direct effect on economic growth, making it critical for attaining macroeconomic stability.

Countries with more saving rates will have rapid economic growth and a high degree of accumulated capital than those countries with a lesser rate of saving. This accumulated capital will lead the country to have additional prospects for productivity through the excess revenue source created (Gao et al., Citation2021; Obalola et al., Citation2018) and encourage saving to mobilize the cash for better productive activities (Ribaj & Mexhuani, Citation2021). Unlikely, low or limited saving results in the reduction of one component of GDP, which is investment, and thereby hurts national economic growth and livelihood of the nation (Ribaj & Mexhuani, Citation2021). Thus, limited domestic saving is the main reason for slow and stagnant economic growth in developing countries like Ethiopia (Tomas, Citation2021). In Ethiopia, 66.6% of the rural inhabitants have financial constraints (Mukasa et al., Citation2017) and thus saving might have a vital role in altering rural livelihoods.

The average annual savings of Ethiopian households in financial institutions is 875 Birr, which is inadequate to sustain economic growth of the country (Feyissa & Gebbisa, Citation2021). This country’s average saving rate is by far less than the average savings rates of the least developed nations (27%) and sub-Saharan African nations (21%) during the year 2021 (World Bank, Citation2022). As of the year 2015/2016–2018/2019, the average investment and saving gap was 37% and 31% of GDP, respectively (National Bank of Ethiopia, (NBE) Citation2019). This low saving rate is due to a variety of factors, including limited access to financial institutions, lack of incentives for savers, low level of financial capabilities, lack of awareness, and financial exclusion (Abdu et al., Citation2021).

At the household level, savings have different benefits including backup plan during the time of emergency, asset accumulation, making cash available for own investment, retirement plan, and many others. It can also assist the household to attain their dreams, purchase of housing, debt settlement, long-term security, and disaster protection. However, there is no experience of modern/formal saving among rural households as they still maintain most of their saving in grain, livestock, stockpiles of goods, and jewelers. This is because informal saving institutions could be easily accessed by rural households or had enough liquidity that can be spent on food (Lidi et al., Citation2017). Likewise, mobilization of saving in Kafa zone in general and Gimbo district in particular is very low, which is evident by households’ failure to maintain their basic needs especially during risky production season.

The existing literatures on saving suffer at least from three shortcomings. First, various studies that have been conducted so far tried to assess the determinants of saving in both Ethiopia and elsewhere (e.g., Duressa & Ejara, Citation2018; Lidi et al., Citation2017; Moses et al., Citation2019; Obalola et al., Citation2018; Ruranga & Hacker, Citation2020). However, most of these studies are focused on assessing the determinants of saving at the macro level, and scanty studies were conducted so far at the household level. Second, a large number of past studies do not tried to look rural saving alone by separating from urban saving (e.g., Abdu et al., Citation2021; Borko, Citation2018; Million & Belay, Citation2019; Ruranga & Hacker, Citation2020). Third, most of the available studies carried out in Ethiopia are not dealt with both factors that affect decision to save and intensity of saving (e.g., Azeref & Gelagil, Citation2018; Borko, Citation2018; Duressa & Ejara, Citation2018; Gonosa et al., Citation2020; Mulatu, Citation2020; Negeri & Kebede, Citation2018). Thus, the need for the current study, which is aimed to investigate rural households saving status and its determinant factors, is clearly indicated.

The prime significance of the study is that policymakers at regional and national levels are expected to draw some lessons in order to design an effective strategy, thereby addressing the constraints of rural saving. Above all, it is going to provide the benchmark for forthcoming interested researchers in the same or related topic in the southwest region and/or elsewhere in Ethiopia. To sum up, the results of this study may provide clues for regional and federal policy designers and other responsible bodies to boost rural private saving.

2. Literature review

There are several empirical evidences elsewhere in the world and Ethiopia that show how and by what predictors rural household saving participation can be determined. In a nutshell, the reviews on the factors that influence rural household saving participation revealed that the effect of demographic, socioeconomic, and institutional factors varied among locations. This implies that site- and resource-specific research should be performed to uncover the factors that influence rural households’ participation in savings in various places. Moreover, the review also shows that logit was the most commonly used and more appropriate econometric tool to determine the factors that affect the participation in saving. Likewise, age, sex, and education level of the household head, livestock holdings, annual spending, credit service, land size, annual income, family size, dependency ratio, distance from financial institution/s, and market distance are the variables that are most commonly used by studies as explanatory variables. The current study tries to fill the methodological gaps by including new explanatory variables that are not considered by most past studies. These variables include the application of improved seed and fertilizer, financial literacy, participation in off-farm activities, participation in non-farm activities, and financial inclusion.

In almost all of these reviewed studies, the variables such as distance from financial institution, distance from the market, family size, and dependency ratio were found to affect the participation in saving significantly and negatively. However, the variables such as education level of the household head, sex of the household head, annual income, total livestock unit, land size, and credit service were found to affect saving significantly and positively in almost all of the reviewed studies. Despite to this, age of the household head was found to have both positive and negative effects. Hence, among the variables selected for the current study basing these reviewed literatures and economic theories (as listed in Table ), the effect of age on the dependent variable was indeterminate in prior for this study. More specifically, the details of this summary review were provided below.

A study aimed to evaluate and identify the factors affecting farm households’ propensity to accrue savings was held by Strzelecka and Zawadzka (Citation2023). To achieve this goal, the study used classification and regression tree analysis. The analysis included the data from 348 farmers gathered through a survey. Based on the classification-regression tree approach, it was discovered that income was the most important factor distinguishing the investigated population in terms of savings, followed by farm size and education level of the household head. It was also shown that, in the case of lower-income families, having a successor when the head of the family had at least secondary education and was above 34.5 years old was a factor negatively impacting savings accumulation.

Bollinger et al. (Citation2022) conducted a study on assessing whether higher education access influences saving rates of the household. The reason why households with children save more is illustrated with a two-period model of family saving choices. Utilizing survey information from Chinese households during the remarkable development of schooling, the study looked at this notion. The study examined the impact on household saving rates by comparing families before and after the reform utilizing estimates of the shift in anticipated likelihood of attending college. According to the study, a 10% increase in the likelihood of attending college improves the saving rate by 5.9 percentage points.

A study by Sibuea and Sibuea (Citation2020) assessed the effect of socioeconomic factors on households’ willingness to save. The research is a case study that was conducted in Deli Serdang Regency, North Sumatera, using a total of 60 respondents as a sample from 312 paddy rice farmers. The findings demonstrated that factors such as age of the household head, number of dependents, education level, and experience had a substantial impact on the capacity to save. Simultaneously, the capacity to save is significantly influenced by economic factors such as land size, pricing, income, and consumption.

Lugauer et al. (Citation2019) examined the effect of family size on households’ saving status. The study started by examining a theoretical lifecycle model that takes into account finite lifespans, retirement savings, and parental concern for their dependent children’s consumption. According to the model, there is an inverse link between the household saving rate and the number of dependent children in a family. The study further indicates that households with less dependent children save much more money than other households. Additional insights into household saving habits are revealed by the data. Urban families had greater saving rates and a lower ratio of education costs to income, but households with children in college have lower saving rates. However, urban households with more children save less than the rural households.

Asfaw et al. (Citation2023) applied a double hurdle model to identify the decision to save and intensity of saving. As the descriptive result indicated, only 35% of pastoral and agropastoral households were savers. The econometric model result showed that credit access, financial literacy, non-farm participation, crop cultivation, education level of the household head, and wealth are the positive predictors of rural saving. Moreover, livestock holding and distance from formal financial institutions affect rural saving negatively.

The study by Mazengiya et al. (Citation2022) aims at investigating the factors that affect the likelihood of households’ participation in saving in the case of Libokemkem district. The study employed a logistic regression model, and the result shows that farm land, family size, education level, frequency of extension contact, and credit access are the factors that affect rural households participation in saving. Moges et al. (Citation2021) conducted a study in Wolaita Sodo town on the determinants of urban household savings. The variables positively related to the probability of saving in logistic regression analyses are education level of the household head, gender, marital status, annual expenditure, credit, annual income, and interest rate. Age of the household head, family size, transaction cost, distance from financial institution/s, and market distance are all negatively correlated with the likelihood of saving.

Study by Feyissa and Gebbisa (Citation2021), which is held by using primary data collected from 327 sample respondents, revealed that 52.6% of the sample households surveyed had saved their money in formal financial institutions. The study used tobit model to identify the factors that hinder rural saving. The model result showed that the education level of the household head, sex of the household head, family size, average annual spending, annual income, access to credit service, and livestock ownership were found to have a significant effect on rural households’ saving.

Addis et al. (Citation2019) investigated farm households’ saving habits in the southwest Amhara development corridor using the ordered probit regression model. The results indicated that farm households’ saving habits are quite low. Only 35% and 30.2% of the total sample farm families had regular and irregular saving habits, respectively, while the remaining 35% have no saving habits at all. The results of the order probit model show that the size of land, education, saving account, income, aid, festive spending, health insurance, access to mobile, the number of nearby formal financial institutions, credit, and remittance are likely to influence saving habits.

3. Methodology

3.1. Description of the study area

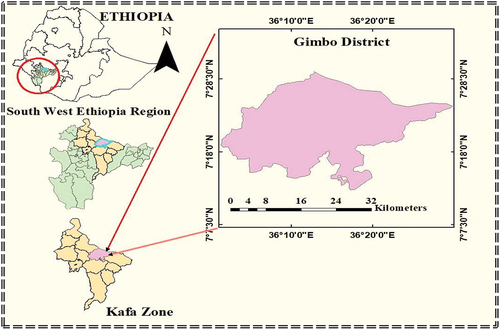

This study was conducted in Gimbo district of Kaffa zone, Southwest Ethiopia (Figure ), which is located at a distance of 460 km from the capital city, Addis Ababa, and 20 km from the Zonal city, Bonga. The district is bordered in the north by Gewata district, Adiyo district in the south, Oromiya in the east, and Bonga town in the west. As data obtained from Gimbo district’s Finance and Economic Development show, the study district has a total projected population of 147,500 with 24,100 household heads (Gimbo woreda finance and economic development office, Citation2011). The district has a total of 37 KebeleFootnote1 administrations, which covers an area of 87,186.05 km2. It has a unique modal rainfall with low rain fall from November to February and wettest months between May and September. The mean annual rainfall is 1,794 mm per year with variations from 1,356 to 2445 mm per year. As recorded by Bonga meteorological station, the study district has a mean annual temperature of 18.5°C, which ranges from a mean annual minimum of 11.5 to a mean annual maximum of 25.5°C. The major source of livelihood in the study area is agricultural production, which is rain-fed and traditional, that includes livestock rearing and collection of non-timber forest product. Almost all rural households that live in Gimbo district produce coffee. In terms of education, 36.29% of the population was considered literate; 25.8% of children aged 7–12 were enrolled in primary school; 13.05% of children aged 13–14 were enrolled in junior secondary school; and 7.81% of those aged 15–18 were enrolled in senior secondary school. Concerning access to water, at the time of the census, around 50.28% of urban dwellings and 21.90% of all houses had access to safe drinking water (CSA, Citation2007). There is an increasing trend in the investment activities in the study area from year to year. Generally, over the past 10 years, an estimated number of 75 investment projects were granted permission to work in agricultural investment activities, most of which are located in the identified forest areas.

3.2. Data type and sources

Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. The primary data were collected using both open-ended and close-ended structured questionnaire relying on various demographic, socio-economic, and institutional characteristics. The questionnaire was translated into language spoken in the study area (Kafinga) to convey the questions effectively to the rural interviewees. Five enumerators with a minimum of BSc/BA degree qualification were employed by the researcher to carry out data collection task. They had trained on the objectives of the study, purpose/significance of the study, study area, and contents of the survey 1 day prior to the pilot and original survey. Throughout the data collection period, frequent and repeated supervision was held by the researcher. Secondary data were obtained from different sources like governmental and non-governmental reports and other relevant documents of various formal financial institutions such as Omo Micro Finance, Commercial Bank of Ethiopia, and others.

3.3. Technique and size of sampling

Using household as the unit of analysis, the study selected the representative samples by employing a multistage sampling technique. In the first stage, from the entire 10 districts of Kaffa zone, Gimbo district was purposively selected on the basis of its cash crop (coffee) productivity (Tassew et al., Citation2022). The reason to choose this coffee-producing district is that households get more income during the harvesting season only once in a year (Melesse & Belachew, Citation2018). This necessitates the need to expand rural saving through research and awareness creation especially for those households whose livelihood mostly depends on coffee production. This was followed by random selection of four rural kebelesFootnote2 that are a representative of the selected study district. Finally, considering a non-response rate of 3%, an aggregate of 405 rural households were selected from all the study kebeles by employing proportional to size procedure. Likewise, the enumerator selected the household to be interviewed by applying a simple random technique of sampling with replacement.Footnote3 Sample size estimation formula, which is developed by Yamane (Citation1967), was applied to get the stated representative sample size, and the estimation is given by:

where n—stands for required sample size; N-household size that are found in the study area; and e-level of precision that is assumed to be 5%, as standard.

3.4. Methods of data analysis

3.4.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics such as mean, percentage, standard deviation, and so on was employed to summarize demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the sample household. In addition, comparisons based on different explanatory and outcome variables were held using t-test and chi-square test. Having dichotomous dependent variable is the rational to use t-test and chi-square test to make comparison between those two groups. Consequently, t-test is used for continuous explanatory variables, while chi-square test is used for dummy and categorical variables.

3.4.2. Determinants of saving

To assess the factors that affect rural households’ decision to save, logit model was applied using the hypothesized predictor variables as indicated in Table . This model assists in estimating rural households’ probability of being saver that can take one of the two values, saver or non-saver. The reasons to use logistic regression are its ease of use, simplicity to implement and interpret, and very efficient to train. If the number of observation is greater than the number of features, logistic regression should be the best econometric tool to be applied. Furthermore, it also makes no assumptions about distributions of classes in feature space. According to Gujarati (Citation2003), the functional form of the logit model is specified as:

where is the probability that an ith respondent can be saver, which ranges from 0 to 1, and Zi is a functional form of m explanatory variables that is expressed as:

where is the intercept,

is the slope parameters in the model, and e is the error term. If

is the probability of being saver, then

indicates the probability of being non-saver.

In addition to this, multiple linear regressions were estimated using ordinary least square (OLS) estimation to identify the factors affecting rural households’ intensity of saving, and the specification is given as:

where Si is the ith households’ amount of saving, X′ is a vector of explanatory variables, β is a vector of parameters to be estimated, and e is the error term.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Comparison of rural households saving: inferential results

As it has been depicted in Table , a significant mean variation in terms of family size was found between saver and non-saver at 10% significance level. The result implies that households with less number of families were likely to save their money in formal financial institutions than their counters. Furthermore, the mean number of years that the head of the household spent on school was also computed, and it was found to be very low, with the mean education level of 2.6, which is less than the national average of 2.9 years (United Nations Development Program, Citation2021). The mean comparison test result presented in the same table for the variable “education level of the household head” shows the existence of significant variation among saver and non-saver at 1% significant level. The result in the table further indicates the existence of a significant variation among saver and non-saver households in terms of their home distance from financial institutions at a significance level of 1%. As the result revealed, saver households are suited closer to financial institution than the non-saver households. The mean land size of the total sampled households was found to be 2.98 hectare, with a mean of 3.17 and 2.82 for saver and non-saver households, respectively. Due comparison between saver and non-saver respondents based on their mean size of land indicates that those saver households on average have more area of land than their non-saver counters. The corresponding independent t-test results shows that the mean land size difference between saver and non-saver households is statistically significant at 5% probability level. Households’ annual farm income from selling of various agricultural products like livestock and crop was found to be 11,575 ETBFootnote4 on average. A comparison between saver and non-saver households based on the mean farm income depicts that those non-saver households have less amount of farm income (8,293) than those saver households (15,217). Likewise, statistical results of the t-value shows that the mean difference in gross farm income between saver and non-saver households was found to have a 1% significant effect on their saving status.

Table 1. Summary statistics for continuous independent variables

Of the entire sampled households, 389 (96%) were male headed, while 16 (4%) were female headed (Table ). As the respective chi-square test presented in the same table shows, out of the 389 male-headed households, 191 (49%) were saver and 198 (51%) were not-saver. Moreover, 1 (6.25%) of the female headed households were saver and the rest 15 (93.75%) were non-saver. As the test result (χ2-value) shows, a substantial proportion difference exists between saver and non-saver households in terms of sex at 1% probability level. Furthermore, financially literate households were found to be more saver than their illiterate counterparts. From the whole sample households surveyed, 140 (34.6%) were financially literate, while 265 (65.4%) were financially illiterate. The result further indicates that out of the total (140) financially literate households, 79 (56.4%) of them were saver and the rest were non-saver. Additionally, from the entire (265) financially illiterate households, 42.6% of the respondents were saver, while 57.4% of them were non-saver. As the respective chi-square (χ2) value depicts, there were a significant variation (proportion difference) in saving status between financially literate and illiterate households at the 1% probability level. From the whole sample households surveyed, 129 (32%) households were participants in at least one non-farm activities, while 276 (68%) were non-participant. It is also shown that out of the total (129) non-farm participant households, the share of saver households were 78.3%, while non-saver households accounted for 21.7% share. Likewise, out of the total (276) non-participant households, 33% were saver, while the rest (67%) were non-saver. As the chi-square (χ2) value indicates, there was a significant variation in saving status between non-farm participant households and non-participant households at the 1% probability level.

Table 2. Summary statistics for dummy independent variables

4.2. Status of rural saving

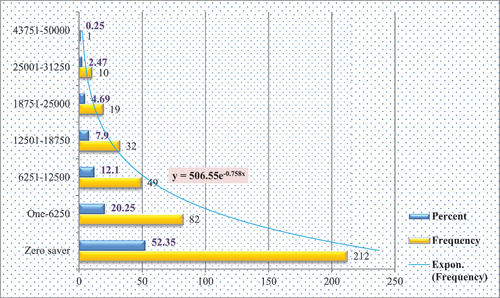

Out of the entire sample households surveyed, 193 (47.65%) were saver, whereas 212 (52.35%) were non-saver households (Table ). This reveals that less than half of the sampled rural households were saving their income left from food and non-food spending or other expenses at formal financial institutions. Additionally, when we look at the intensity of saving, the whole sampled households saved 4,788.15 ETB on average (Table ). When this mean saving is allocated for financially literate and illiterate households, those literate households saved 5,615 ETB on average, while illiterate households saved 4,351.32 ETB on average.

Table 3. Frequency distribution of binary saving

As depicted in Figure , among the eight category of saving amount (intensity), the lion share was protected by those zero saver households. This was followed by those households who saved between the ranges of 1–6,250 ETB, which accounts for about 20.25% of the entire surveyed households. A substantial number of households were also found to save an amount, which ranges between 6,251and 12,500. Thus, households who saved with in this saving category constitute about 12.1%. Generally, the least number of saver households were recorded in the highest saving (eighth) category. This is to mean that only 1 (0.25%) household was found to be saver within the eighth category of saving (43,751–50,000 ETB).

4.3. Determinants of rural saving

In order to identify the factors that affect farm households’ decision and intensity to save, logistic regression and OLS estimations were applied, respectively. At the ever beginning before the actual models are fitted and the results are reported, pre-conditions, fitness of the econometric model with the data, and different estimation/econometric problems were checked. Both models were significant at 1% level of significance in explaining the association between explanatory variables and dependent variable (Tables ). Accordingly, the model was found to be the best fitted. Test results for checking the existence of serious multicollinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF) was presented in Table , which indicates the absence of serious multicollinearity. Likewise, problem of heteroscedasticity was also tested using Breusch–Pagan test, and the result (chi2 (1) = 237.67 and Prob > chi2 = 0.0000) shows that there is sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis (H0: constant variance) (Table ). Hence, robust standard errors were estimated to account for heteroscedasticity. Furthermore, the R-squared value obtained from OLS also shows that 54.94% of the variations in the amount of saving among the sample households were due to the explanatory variables included in the model (Table ). Consequently, the estimation results obtained using the two models were presented and discussed in brief here below.

Table 4. Factors that affect rural households’ decision to save: logistic regression result

Table 5. Factors that affect rural households’ amount of saving: linear regression result

4.3.1. Factors that affect decision to save

In a nutshell, sex of the household head, education level of the household head, distance from financial institution, farm income, financial literacy, participation in off-farm activities, and participation in non-farm activities were found to affect farming household heads’ decision to save significantly and positively except distance from financial institution (Table ). As the marginal effect result (Table ) revealed (ceteris paribus), being male, financially literate, participant in off-farm activities, and being participant in non-farm activities increase the probability of being saver by 23.13%, 10.07%, 12.22%, and 32.33%, respectively. These variables were found to affect the dependent variable, which is decision to save at the 1% significance level except financial literacy, which is significant at 5% level of significance. The associated reason of participation in different off-farm and non-farm activities to have such an effect on the household heads’ decision to save might be the capability of these activities to generate income, thereby to combat financial deficiency that the household faced, which then encourage to have a positive decision to save. Furthermore, the reason to have a positive result for male-headed households’ decision to save might be due to their ability to participate in high-income-generating activities, decision-making power, and financial information that male-headed households have. However, when compared to males, females are not such careless; rather they are more responsible and eager to keep their household members’ food security and give more care for their child/ren’s health; thus, they might not get savable income left from consumption. The result discussed was in line with Azeref and Gelagil (Citation2018), Borko (Citation2018), Feyissa and Gebbisa (Citation2021), and Asfaw et al. (Citation2023). Likewise, those households who are financially literate can grasp and differentiate pecuniary opportunities, make decisions that safeguard against forthcoming uncertainties, feel comfort to discuss personal financial concerns, and eager to save their financial resources (Abdu et al., Citation2021; Gaisina & Kaidarova, Citation2017). Investigation of Sanderson et al. (Citation2018) and Asfaw et al. (Citation2023) were in line with the present result.

Based on the model result presented, increment in education level by 1 year of schooling will result in an increment in the probability of being saver by 3.21%, which was found to be significant at 1%. This might be because of the knowhow, knowledge of different promising financial institutions, and awareness about the importance of saving that the educated household heads have. Investigation result by Lidi et al. (Citation2017), Ruranga and Hacker (Citation2020), Feyissa and Gebbisa (Citation2021), and Mazengiya et al. (Citation2022) also presented the same report for this specific variable. Distance from financial institution was found to be the only variable that affects the probability of being saver negatively and significantly. Keeping other factors at their mean value, increment in distance from financial institutions by 1 km will result in 1.25% decline in the probability of being saver with 1% level of significance. This might be because, as financial institutions are far away, possibility of the households to be excluded from financial services like credit/loan will be high, obtaining updated financial information and services will be difficult, and higher transaction costs will be incurred to access the service, and thus the household will be less eager to save and their decision to save will be negative. This result is consistent with the findings of Negeri and Kebede (Citation2018), Feyissa and Gebbisa (Citation2021), and Asfaw et al. (Citation2023).

The variable annual farm income was found to have a positive and statistically significant effect on the households’ decision to save. Households’ likelihood of being saver increases by 0.0016% as a response for 1 ETB increment in farm income, ceteris paribus (Table ). This is because, since saving is a part of income that is left from consumption, any alteration in farm income is therefore attributed to the adjustment in saving. Likewise, according to economic theory, an increment in income beyond a certain level will result in the decline in marginal propensity to consume and escalation of marginal propensity to save. This is due to the nature of richer household heads’ willingness to secure their wealth in a safe place like formal financial institutions. This inspires the household to have a positive decision to save and thus start to save in such financial institutions whatever the amount is. This result is in line with economic theory and comparable with the studies held by Azeref and Gelagil (Citation2018), Negeri and Kebede (Citation2018), Feyissa and Gebbisa (Citation2021), and Asfaw et al. (Citation2023).

4.3.2. Factors that affect intensity of saving

Among the various factors of saving intensity that were obtained using the regression, education level of the household head was the one. This variable was found to be positively correlated with the intensity of saving and significant at 1% probability level (Table ). Its coefficient value reveals that, as the number of school years that the household head completed increase by 1 year, the amount of saving will also increase by 332 ETB, ceteris paribus. Trust in the financial institutions and awareness about the importance of saving that the educated household heads do have might be the reasons that catalyze and encourage them to save more. Related finding was also reported by the study by Mulatu (Citation2020).

Keeping the effect of other factors constant at their mean value, financially literate household heads’ amount of saving outweighs by 1,085 ETB when compared to their counterpart (Table ). This might be due to the knowhow that financially literate households do have, which enable them to set sound financial choices about how much to save for future contingency need. This result is related to the findings by Gaisina and Kaidarova (Citation2017) and Sanderson et al. (Citation2018).

Based on the investigation results presented in Table , improved seed and inorganic fertilizer user households’ amount of saving lags behind their non-user counterparts by 1,523 ETB. The associated reason is that households who use improved seed and inorganic fertilizer always incur more costs by investing their idle income for such purposes; hence, they might have left with less earnings for saving.

For 1 km increment in the distance between households dwelling and financial institutions, the amount they save will fall approximately by 108 ETB. This might be because, as financial institutions are far away, households will save less by fearing higher transaction costs to be incurred during future movement to withdraw cash if they save all of what they have and left empty pocket. This will result in partial amount of saving in financial institutions when part of their income is kept in local saving. Consistent result is reported by the studies by Lidi et al. (Citation2017), Duressa and Ejara (Citation2018), Mulatu (Citation2020), Ruranga and Hacker (Citation2020), and Feyissa and Gebbisa (Citation2021).

The income obtained from on-farm activities (i.e., farm income) and participation in non-farm activities was also found to have a positive and significant effect on the amount of saving. As a response to 1 ETB increment in farm income, households’ saving amount will rise by 0.53 ETB. Result that is in line with this specific finding was reported by Duressa and Ejara (Citation2018), Mulatu (Citation2020), and Balcha and Chafa (Citation2022). The last interesting and distinguished result presented is the amount of saving enhanced by 2,336 ETB for those participants in different non-farm activities. This is to say, non-participant households saving amount lags behind participants by 2,336 ETB. The reason is that when households participate in different non-farm activities in addition to farming, households’ income source will be diversified and their earnings will be advanced and be eager to save more than those who are not participating. This result is related to that reported by Lidi et al. (Citation2017), Moses et al. (Citation2019), and Asfaw et al. (Citation2023).

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Saving is critical to build capital required to generate income, smooth domestic cash requirements, and allow the ease of consumption during scarcity. Hence, it is more significant especially for developing countries like Ethiopia than the developed one. However, saving at the household level was not substantially investigated in Ethiopia in general and in the study area in particular. The current study therefore assessed rural households’ saving status and its determinant factors in Gimbo district, south west region of Ethiopia. To do so, descriptive statistics, inferential statistics like t-test and chi-square test, and econometric models such as logit and multiple linear regression were applied using the data collected from randomly selected 405 sample households from four rural kebeles of Gimbo district. As the result from descriptive statistics indicated, out of the entire sample households surveyed, more than half (52.35%) of the surveyed households were non-saver. This is to mean that a lesser proportion of the sampled households were saving their income left from food and non-food spending or other expenses at formal financial institutions. When we look at the intensity of saving, the whole sampled households saved 4,788.15 ETB on average.

Savings was discovered to be influenced by several demographic, socioeconomic, and institutional factors, as both the logit and linear regression model results demonstrated. Among those factors, education level of the household head, distance from financial institutions, farm income, financial literacy, and participation in non-farm activities were found to affect both decision to save and intensity of saving significantly and positively except distance from financial institutions, which is negatively correlated with both. Likewise, both sex of the household head and participation in off-farm activities (positively) and application of improved seed and inorganic fertilizer (negatively) were found to be factors that significantly affect decision to save and intensity of saving, respectively. Therefore, to overcome negative effects of distance from financial institutions, the study recommend expansion of financial institutions up to kebele levels as much as possible. Moreover, policymakers and other concerned bodies responsible for the enhancement of rural private saving should have to improve rural households’ farm income, education, financial literacy, and participation in non-farm activities.

The findings of the study must be viewed in light of some potential limitations. First, the study was limited to Gimbo district only, which is selected randomly; hence, taking samples from this district only might not allow making generalization about the whole region. Second, data were gathered through a cross-sectional survey. The data do not account for any changes in households’ demographics or resource endowments that may have occurred throughout the years. The research assumed that the demographics and resource endowments of rural families remained stable during the years the household was saved. Estimates of the average annual yield and income were calculated based on what the household heads interviewed was able to remember from the previous year, which may or may not be typical years. Future study should incorporate temporal components to see if the factors/variables that affect rural household saving participation have changed over time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. It is the subdivision of district, which is the smallest administrative unit in Ethiopia.

2. It is the smallest administrative hierarchy in Ethiopia next to district.

3. The full list of households living in the study area or respective kebele was obtained from the kebele administrator. The study used this list as a sample frame and selected households randomly; however, when the selected farmer/respondent does not appear in the area or unable to provide response (not willing to be interviewed), s/he was replaced by farmer next to her/him in the list.

4. ETB stands for Ethiopian birr, which is the official currency of Ethiopia. One ETB was equivalent to 52 dollar during the time of survey.

References

- Abdu, E., Adem, M., & McMillan, D. (2021). Determinants of financial inclusion in Afar region: Evidence from selected woredas. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1920149. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1920149

- Addis, F., Belete, B., & Bogale, M. (2019). Rural farm household saving habit in Ethiopia: Evidence from south west Amhara growth corridor. Academic Journal of Economic Studies, 5(3), 112–18.

- Asfaw, D. M., Belete, A. A., Nigatu, A. G., Habtie, G. M., & Barreda-Tarrazona, I. (2023). Status and determinants of saving behavior and intensity in pastoral and agro-pastoral communities of Afar regional state, Ethiopia. PLoS One, 18(2), e0281629. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0281629

- Azeref, A. G., & Gelagil, Y. T. (2018). Determinants of rural household saving: The case of North Shewa zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Journal of Investment and Management, 7(5), 151–156. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.jim.20180705.13

- Balcha, D., & Chafa, M. (2022). Determinants of saving in rural saving and credit cooperatives in Sodo Zuria Woreda, Wolaita zone, Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Scientific & Research Publications (IJSRP), 12(7). (ISSN: 2250-3153). https://doi.org/10.29322/IJSRP.12.07.2022.p12709

- Bollinger, C., Ding, X., & Lugauer, S. (2022). The expansion of higher education and household saving in China. China Economic Review, 71, 101736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2021.101736

- Borko, Z. P. (2018). Determinants of household saving the case of Boditi town, Wolaita zone, Ethiopia. Open Journal of Economics and Commerce, 1(3), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.22259/2638-549X.0103003

- CSA. (2007). Population and housing census of Ethiopia: Results for southern nations, nationalities, and peoples. Region, Vol. 1, part 1 Retrieved April 5, 2023).

- Dong, J., Deng, R., Quanying, Z., Cai, J., Ding, Y., & Li, M. (2021). Research on recognition of gas saturation in sandstone reservoir based on capture mode. Applied Radiation and Isotopes, 178, 109939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2021.109939

- Duressa, T. G., & Ejara, F. S. (2018). Determinants of saving among rural households in Ethiopia: The case of Wolaita and Dawro zone, SNNPR. International Journal of Advanced Research, 6(3), 731–739. https://doi.org/10.21474/IJAR01/6726

- Feyissa, G. F., & Gebbisa, M. B. (2021). Choice and Determinants of saving in rural households of Bale zone: The case of Agarfa district, Oromia, South East Ethiopia. Open Access Library Journal, 8(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1107167

- Gaisina, S., & Kaidarova, L. (2017). Financial literacy of rural population as a determinant of saving behavior in Kazakhstan. Rural Sustainability Research, 38(333), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1515/plua-2017-0010

- Gao, C., Hao, M., Chen, J., & Gu, C. (2021). Simulation and design of joint distribution of rainfall and tide level in Wuchengxiyu region, China. Urban Climate, 40, 101005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101005

- Gonosa, A., Bargissa, B., & Tesfay, K. (2020). Factors’ affecting the motives of rural households’ saving behavior in North Bench district, Bench Maji zone of southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Agricultural Science, Research and Technology in Extension and Education Systems, 10(2), 93–101.

- Gujarati, D. (2003). Basic econometrics (4th ed.). New York.

- GWFEDO, Gimbo woreda finance and economic development office. (2011). Unpublished official data

- Kuma, T., Dereje, M., Hirvonen, K., & Minten, B. (2019). Cash crops and food security: Evidence from Ethiopian smallholder coffee producers. The Journal of Development Studies, 55(6), 1267–1284. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1425396

- Leto, N. M. (2016), Determinants of saving behaviour of working women household head in Arba Minch Town, Gamo Gofa Zone, SNNPR [ MSc thesis]. Arba Minch University.

- Lidi, B. Y., Bedemo, A., & Belina, M. (2017). Determinants of saving behavior of farm households in rural Ethiopia: The double hurdle approach. Developing Country Studies, 7(12), 17–26.

- Lugauer, S., Ni, J., & Yin, Z. (2019). Chinese household saving and dependent children: Theory and evidence. China Economic Review, 57, 101091. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2017.08.005

- Mazengiya, M. N., Seraw, G., Melesse, B., & Belete, T. (2022). Determinants of rural household saving participation: A case study of Libokemkem district, North-west Ethiopia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2127219. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2022.2127219

- Melesse, B., & Belachew, K. (2018). Forest coffee production in Ethiopia: The case of Gimbo district, Kaffa zone, southwest Ethiopia. Forest, 8(12).

- Million, S., & Belay, A. (2019). Statistical analysis of factors affecting average monthly saving money of lecturers in case of natural and computational science. Science Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 7(5), 83–88. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.sjams.20190705.14

- Moges, F., Senapathy, M., & Alves, P. (2021). Determinants of urban households saving: The case of Wolaita Sodo town. Southern Ethiopia, 8(2), 1–17.

- Moses, J. D., SA, O., & Okpachu, O. G. (2019). Determinants of savings and capital accumulation among rural women farmers in Ganye local government area of Adamawa state.

- Mukasa, A. N., Simpasa, A. M., & Salami, A. O. (2017). Credit constraints and farm productivity: Micro-level evidence from smallholder farmers in Ethiopia. African Development Bank, 247.

- Mulatu, E. (2020). Determinants of smallholder farmers’ saving: The case of Omo Microfinance Institution in Gimbo district of Kaffa zone, Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Accounting, Finance and Risk Management, 5(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijafrm.20200502.14

- National Bank of Ethiopia (NBE). (2019). The macroeconomic context of Ethiopia. Domestic Economic Analysis and publication Division. 2019.

- Negeri, M. A., & Kebede, B. Z. (2018). Econometric analysis of socioeconomic and demographic determinants of rural households saving behavior: The case of Sinana district, Ethiopia. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 10(4), 120–126. https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2017.0905

- Obalola, O. T., Audu, R. O., & Danilola, S. T. (2018). Determinants of savings among smallholder farmers in Sokoto south local government area, Sokoto State, Nigeria. Acta Agriculturae Slovenica, 111(2), 341–347. https://doi.org/10.14720/aas.2018.111.2.09

- Ribaj, A., & Mexhuani, F. (2021). The impact of savings on economic growth in a developing country (the case of Kosovo). Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-00140-6

- Ruranga, C., & Hacker, S. (2020). The determinants of households having savings accounts in Rwanda. Rwanda Journal of Social Sciences, Humanities and Business, 1(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.4314/rjsshb.v1i1.2

- Sanderson, A., Mutandwa, L., & Le Roux, P. (2018). A review of determinants of financial inclusion. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 8(3), 1.

- Sibuea, M. B., & Sibuea, F. A. (2020). The effect of social economic factors on ability to save of farmers: The role of income supply, education supply, experience, age, land area distribution, piece, consumption and family. International Journal Supension Chain Mgt Vol, 9(3), 1027.

- Strzelecka, A., & Zawadzka, D. (2023). Savings as a source of financial energy on the farm—What determines the accumulation of savings by agricultural households? Model approach. Energies, 16(2), 696. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16020696

- Tassew, A. A., Yadessa, G. B., Bote, A. D., & Obso, T. K. (2022). Location, production systems, and processing method effects on qualities of kafa biosphere reserve coffees. Agrosystems, Geosciences & Environment, 5(2), e20270. https://doi.org/10.1002/agg2.20270

- Tomas, Z. (2021). Factors affecting saving practices of members of rural saving and credit cooperatives (The case of Ada’a Woreda, East Shewa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia) [ Master’s Thesis]. St. Mary’s University.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Program). (2021). Human development report 2020: The next frontier human development and the anthropocene.

- Wieliczko, B., Kurdys-Kujawska, A., & Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. (2020a). Savings of small farms: Their magnitude, determinants and role in sustainable development. Example of Poland. Agriculture, 10(11), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10110525

- Wieliczko, B., Kurdys-Kujawska, A., & Sompolska-Rzechuła, A. (2020b). Savings of small farms: Their magnitude, determinants and role in sustainable development. Example of Poland”. Agriculture, 10(11), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture10110525

- World Bank. (2022). National Accounts Data, and OECD National Accounts Data Files, 2022. (Retrieved July 19, 2023).

- Yamane, T. 1967. Statistics: An introductory analysis (No. HA29 Y2 1967)

Appendix

Table A1. Definition, type, and hypothesis of variables

Table A2. Marginal effects for binary saving, y = Fitted values (predict): y = 0.4765432

Table A3. Multicollinearity test using VIF

Table A4. Heteroscedasticity test using Breusch–Pagan or Cook–Weisberg test

Table A5. Mean difference of amount saved between financially literate and illiterate household heads