Abstract

In the concept put forward by the Behavioral Theory of the Firm (BTF), the policies implemented must provide added value to the company. In their preparation, policies will be heavily influenced by decision-makers behavior. This study was conducted to see the company’s value dividend policy and the impact of CEO Narcissism in that policy. This empirical research involved companies indexed by Kompas 100 from 2011 to 2019 and was tested using Moderated Regression Analysis (MRA). This study confirms that dividend policy is a signal for increasing firm value, so this policy deserves further attention from management. CEO Narcissism drives the increased value generated by the dividend policy and acts as pure moderation. This result is also strengthened by the robustness test conducted on Tobin’s Q to measure firm value. This research is the first study to examine the moderating effect of CEO Narcissism on dividend policy and its impact on firm value. Through the findings of this research, it is hoped that this study will contribute to the Behavioral Theory of the Firm and become a guide for companies to pay attention to the dividend policy formulation process so that it provides value, both for shareholders and for the company.

1. Introduction

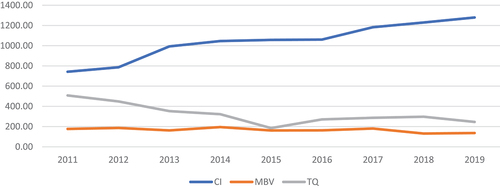

The phenomenon of stock trading in Indonesia is fascinating. We explored the Indonesia Stock Exchange’s Kompas 100 Index, which summarizes companies with good fundamentals. From 2011 to Citation2019, we compared notable trends for further research. Graph 1 below compares the Kompas 100 Price Index and company value, as measured by the market to book value and Tobin’s Q. As an illustration of developments and interest in transactions on the stock market, the graph shows an increasing trend of the Kompas 100 Price Index. However, the company’s value tends to decrease. This picture raises the question of why interest in investing in Kompas 100 sector stocks is increasing. At the same time, the average company value shows a trend that tends to stagnate or even decline.

In general, stock trading is carried out by capital owners with the hope that the investment made in certain company shares will provide a return in the future. As the main return, dividends are expected by the owners of capital. Giving dividends is also a strategy or policy that ultimately positively influences the company. Spence (Citation1973), stated that the announcement of dividends is a positive signal for shareholders, which can reduce uncertainty and cause shareholders to be willing to invest their capital. Hence, it has a positive effect on firm value. Several other studies also support the signaling theory and state that dividend policy is an investment-attractive strategy that can be used as a managerial consideration and is believed to increase firm value (Baker & Powell, Citation2000; Baker et al., Citation1999, Citation2006, Citation2012; Salteh, Citation2013; Tahir et al., Citation2020; Tyastari et al., Citation2017; Yousaf et al., Citation2019). Baker et al. (Citation2006) also stated that management must design a dividend policy to generate maximum shareholder value. The dividend is a policy that companies can use to attract investment and provide added value to the company.

However, in fact, not all theories and research results assume that dividends will have a positive effect on firm value. Miller and Modigliani (Citation1961) in their research that produced the dividend irrelevance theory, stated that there is no relevance between dividend payments and firm value. This theory is also supported by empirical studies on firm value dividend payout policy (Bakri & McMillan, Citation2021; Ohlson & Johannesson, Citation2016; Zanon et al., Citation2017). Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004) support the dividend irrelevance theory and produce the Dividend Catering Theory, which states that managers pay dividends only to provide what current investors want. Meanwhile, Budagaga (Citation2021) and Parkinson (Citation2012) state that management prioritizes investing in future projects and will distribute dividends when all financial needs are met. The dividend rate may also affect the manager’s ability to invest in new projects, causing the manager to want to cut dividends to take good, value-added projects, or he may want to pay high dividends to reduce free cash flow to commit himself not to take bad projects and negative impact on the company (Fairchild, Citation2010).

Graphic 1. Comparison of composite Index, market to book value, and Tobin’s Q.

From the description of the inconsistencies in the research results on dividend policy above, the preparation of policies must be carried out carefully so that these policies provide added value to the company. The Behavioral Theory of the Firm (BTF) put forward by Cyert and March (Citation1963) is a theory of corporate behavior that integrates firm and organizational theory and links internal and external factors to the decision-making process. Todeva (Citation2014) states that many rational and irrational factors are mixed in the company’s policy-making process, and one of these two factors is power.

The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) is a source of corporate strength whose role is important in creating innovative strategies and as a leader in creating value for stakeholders (Hamori & Kakarika, Citation2009; Papadakis, Citation2007; Quinn, Citation1985). With his/her power, the CEO gets benefits and convenience to pursue his interests and override the interests of shareholders (Mehdi et al., Citation2017). This is the reason why the behavioral aspects of the CEO are interesting to be further investigated.

Given the increasing number of relationships found between strategy, corporate values, and decision-making behavior, CEOs’ psychological characteristics are currently getting more and more attention. Some of the psychological characteristics of CEOs who have been studied for their influence on key organizational decisions are CEO Hubris (Carnahan et al., Citation2010; Cormier et al., Citation2016; Kouaib et al., Citation2021), CEO Power (Chiu et al., Citation2021; Sheikh, Citation2018), CEO Overconfidence (Aktas et al., Citation2019; Galasso & Simcoe, Citation2011; Gao & Han, Citation2020), to CEO Narcissism, and CEO Narcissism appear to be more prominent in shaping and influencing strategy and the results obtained by the company (Aabo & Eriksen, Citation2018; Al-Shammari et al., Citation2019; Chatterjee & Pollock, Citation2017; Higgs, Citation2009).

Narcissism is a character characterized by the need for high self-esteem, attention, personal superiority, low social empathy, and willingness to manipulate to achieve their needs (Bogart et al., Citation2004; Braun et al., Citation2018; Brown et al., Citation2009; Emmons, Citation1987; Nevicka et al., Citation2011; Wallace & Baumeister, Citation2002). Narcissistic CEOs prefer media coverage to high compensation to fulfill their need to be the center of attention (Aabo et al., Citation2022). A CEO with a narcissistic personality will prioritize his position, interests, and personal goals. Because policies are made that are no longer oriented to company needs, in the end, the strategies or policies made will impact the dynamics of the company’s strategic actions (Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007; Salehi et al., Citation2021). Buyl et al. (Citation2019) stated in their research that CEOs with narcissistic characters will increase the risks inherent in organizational policies, so it can be concluded that CEOs with narcissistic characters will worsen business conditions. Thus, CEO Narcissism is expected to influence business continuity negatively.

Several other research results also show that CEO Narcissism has a negative influence on the company (Aabo, Citation2021, Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, Citation2021; Al-Shammari et al., Citation2019; Buchholz et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; García-Meca et al., Citation2021; Lin et al., Citation2020; Oesterle et al., Citation2016). In the stock market, there has been an unfavorable reaction to announced acquisitions by companies led by narcissistic CEOs (Aabo et al., Citation2020). Narcissistic CEOs also influence unethical leadership (Blair et al., Citation2017), which controls everything to suit their expectations without listening to their subordinates, so this behavior reduces employee innovation (Schmid et al., Citation2021).

Although some previous research results show a negative context for a CEO with a narcissistic character, other research results show that narcissism has a positive value for companies (Brunzel, Citation2021, Byun & Al-shammari, Citation2021; Fung et al., Citation2020; Marquez-Illescas et al., Citation2019; Schmid et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2019). CEO Narcissism was found to strengthen external Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) relationships with Green Technology Innovation (Yang et al., Citation2021). Zhu and Chen (Citation2015) found that a CEO with a narcissistic character will strengthen the influence of the CEO’s experience on corporate strategy but weaken the effect of the experience of other board members on corporate strategy. Braun (Citation2017) also conclude that leaders with narcissistic characters are often seen as charismatic leaders, who are more skilled at communicating their vision boldly, dare to make mergers and acquisitions, and invest in internationalization and new technologies. From the description above, the narcissism of a CEO has two sides, the influence of which is positive and negative to the company.

This research is the first study to examine the moderating effect of CEO Narcissism on the relationship between dividend policy and firm value. To date, there are limited evidence on CEO Narcissism as moderating, and most of the studies test the direct effect of CEO Narcissism on firm’s outcomes. For example, most of the studies examine a direct relationship between CEO Narcissism and company performance (Al-Shammari et al., Citation2019; Bajo et al., Citation2021; Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007; Mahmood et al., Citation2020; Tang et al., Citation2018; Yook & Lee, Citation2020), while other studies focus on innovation and growth (Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2011; Ingersoll et al., Citation2019) and risk-taking (Aabo et al., Citation2020; Aktas et al., Citation2016; Buyl et al., Citation2019; Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007, Citation2011; Ham et al., Citation2018).

The results of this study indicate that the consistency of the dividend policy provides a positive signal in demonstrating the company’s ability to provide the return desired by the capital owner. This research also shows the positive impact given by the CEO with a narcissistic character in strengthening the results given by the dividend policy on the company.

This research contributes to several aspects. First, this research contributes to the behavioral theory of the firm to provide an understanding of the importance of making policies that add value to companies. Apart from contributing to theoretical and empirical development in responding to the inconsistency of research results regarding dividend policy, this research also provides evidence of the influence of decision-making behavior in creating added value for companies through their policies, especially for Indonesia which is unique in its capital market. For Finally, this study also contributes to develop a proxy measure of CEO Narcissism that we do with measurement modifications.

In the next section, the literature review and hypothesis development framework will be discussed in section 2. Then, the research methodology and operational definitions are described in section 3, followed by research results and discussion in section 4, and findings and conclusions in section 6.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Behavioral theory of the firm

Behavioral theory of the firm (BTF) is an approach in economics that focuses on individual behavior in decision-making. BTF is also known as decision theory, which explains that a decision must be made by considering the added value that can be obtained from the decision (Todeva, Citation2014). Like other policies, it is important to review dividend policy more carefully by decision-makers because dividend policy also includes the consequences of using company cash to be distributed to shareholders and whether decisions related to giving dividends will impact increasing company value. Some previous research results found that dividends are a positive signal favored by capital owners (Baker & Powell, Citation2000; Baker et al., Citation2006; Tahir et al., Citation2020; Tyastari et al., Citation2017; Yousaf et al., Citation2019). So that when the company announces that it will pay dividends, it will increase the desire of capital owners to invest in company shares, thus affecting increasing company value.

Cyert and March (Citation1963) stated that in formulating a policy, there are rational and irrational elements to consider, as well as conflicts with limited information, uncertainty, and cognitive biases. BTF, in its approach, is believed to be more holistic because this theory believes other factors must be considered, such as psychological, social, and institutional factors. Todeva (Citation2014) states that the preparation of a decision is made through a process in which all rational and irrational factors are mixed and are influenced by several things, one of which is power. Higgs (Citation2009), in his research, stated that power is something that can be utilized by a leader and causes unethical behavior.

In the context of psychology, character is something that can trigger power abuse and unethical behavior. Leaders in the company are very vulnerable to being suspected of fulfilling their desires using their power, and it is also possible that the decisions they make are not for the organization but for themselves. One of the interesting behavioral studies conducted on CEOs is narcissism. CEO Narcissism is the fundamental personality of a CEO, who is self-focused, has high self-esteem and needs attention, and personal superiority so that he dares to manipulate just to meet his own needs (Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007; Emmons, Citation1987; Raskin & Terry, Citation1988). Narcissism is also believed to be dominant and causes bad behavior in leaders (Higgs, Citation2009).

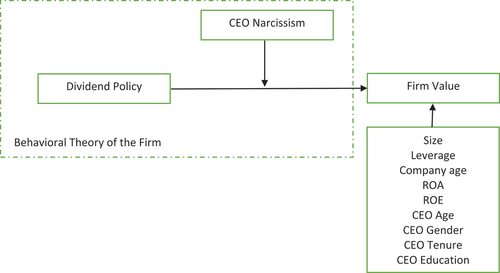

Nonetheless, CEO Narcissism also has a positive influence on the company (Byun & Al-Shammari, Citation2021; García-Meca et al., Citation2021; Sari et al., Citation2022; Zhu & Chen, Citation2015; Brunzel, Citation2021; Fung et al., Citation2020; Schmid et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2019). A CEO who is widely known, especially if the public remembers him because of his achievements, will have a good impact on the company (Hayward et al., Citation2004; Kucharska & Mikołajczak, Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2020; Wade et al., Citation2006). CEOs with narcissistic characteristics are often seen as charismatic and reliable communicators (Braun, Citation2017), so they can increase creativity (Zhou et al., Citation2019) and ultimately affect company performance (Byun & Al-Shammari, Citation2021; Sari et al., Citation2022). Based on the description above and as a reference for preparing hypotheses, we can model this research framework as Figure .

2.2. Hypotheses development

2.2.1. Direct effect of dividend policy to firm value

A dividend policy is a decision made by a company regarding whether to distribute dividends to owners or not, including the dividend amount. The dividend payment policy to shareholders is determined by company management based on company strategy (Dinh Nguyen et al., Citation2021). Dividends themselves are taken from the net profits earned by the company in a certain period, hoping that giving dividends can signal the company’s ability to provide returns for shareholders and bring added value to the company.

Research related to dividend policy so far has had two contradictory directions. Black (Citation1976) describes dividends as a puzzle, where the harder we look at the dividends picture, the more it seems like a puzzle, with pieces that just do not fit together. It is also like existing theories, which have two opposite directions. Miller and Modigliani (Citation1961) put forward the theory of dividend irrelevance, stating that dividend policy cannot affect the company because the company’s value is only influenced by the level of profitability generated by the company’s assets and management competence. Lintner (Citation1962) states that compared to fluctuating capital gains, investors prefer to obtain something with high certainty, such as dividends. The signaling theory put forward by Spence (Citation1973) also explains that dividend announcements can be a positive signal anticipated by the market, especially if the amount announced exceeds market expectations. Conversely, announcing dividends with a lower amount than market expectations can also be a negative signal that the market interprets as a future failure in the company’s financial performance.

Giving dividends is a signal given by management, describing the company’s ability to provide added value to the investments made by shareholders. In making a dividend policy, management must look at the company’s condition so that the policies set are expected to increase the company’s value. Previous research has proven that dividend policy is an investment-attractive strategy that can be used as a managerial consideration and is believed to increase firm value (Baker & Powell, Citation1999, Citation2000; Baker et al., Citation2006; Hunjra et al., Citation2014; Kim & Kim, Citation2020; Tahir et al., Citation2020; Tyastari et al., Citation2017; Yousaf et al., Citation2019; Zakaria et al., Citation2012; Salteh et al., Citation2013).

H1.

Dividend policy has a positive effect on firm value

2.2.2 The moderating effect of CEO narcissism on the relationship between dividend policy and firm value

Narcissism in the world of psychology is described as a psychological construct of a person, with characteristics such as high self-esteem, high pride, success, power, confidence, and feeling special, demands for admiration and attention, reinforcement of self-image from external adulation and praise, and recognition and acceptance (Cragun et al., Citation2020; Emmons, Citation1987; Roche et al., Citation2013; Wallace & Baumeister, Citation2002). Narcissism has two innate elements, namely cognitive and motivational. Cognitive elements are related to belief in one’s strengths and abilities, and motivational elements are related to the desire to receive recognition, attention, and praise (Miller et al., Citation2008). These two elements come together and form human character who wants to get attention and praise for their achievements or abilities.

CEO narcissism is a characteristic of a leader in a company who always prioritizes his position of interests and personal goals and has a negative influence on the dynamics of corporate strategy, which is often associated with information asymmetry (Buyl et al., Citation2019; Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007; Lin et al., Citation2020; Salehi et al., Citation2021). CEO narcissism can also be interpreted as an attitude of excessive self-love or pride in himself, leading to an attitude that prioritizes his interests, which can impact the policies taken. Aabo et al. (Citation2022) also found that narcissistic CEOs prefer to get publicity from the media compared to high compensation. It can be concluded that a narcissistic CEO will greatly affect the achievement of company goals.

Associated with the behavioral theory of the firm, policies as guidelines and directions for the company should provide added value if prepared using actual conditions. However, if the policy is ridden by other interests outside the company’s goals, then it is not profit but risk that will be obtained. A dividend policy is one way to maximize shareholder welfare. However, CEOs with narcissistic characteristics often make policies only to fulfill their need for recognition and praise. It can be concluded that the narcissistic character of a CEO will also influence the added value created for the company by the dividend policy.

Some previous research results show the negative impact that the narcissistic character of a CEO has, both the impact on policy and strategy (Aabo et al., Citation2020; Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, Citation2019; She et al., Citation2019; M; Al-Shammari et al., Citation2019; Buchholz et al., Citation2018; Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007; Oesterle et al., Citation2016; Scotter Van, Citation2020), managerial (Agnihotri & Bhattacharya, Citation2021; Anninos, Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2021), as well as ethics (Blair et al., Citation2017; Buchholz et al., Citation2020; García-Meca et al., Citation2021; Kontesa et al., Citation2021; Lin et al., Citation2020; Rijsenbilt & Commandeur, Citation2013). Acquisition policies can harm market reactions if carried out by CEOs with a narcissistic character (Aabo et al., Citation2020), and have an impact on reducing the completeness of information but accelerating decision-making, so it has the potential to harm the company (She et al., Citation2019). CEOs with narcissistic characteristics will also narrow opportunities for employees to express ideas (Zhou et al., Citation2021), and narcissistic CEOs do not hesitate to manage earnings (Kontesa et al., Citation2021).

In addition to the negative side, several other research results found a positive side to the narcissistic character of a CEO toward the company (Braun, Citation2017; Brunzel, Citation2021, Byun & Al-Shammari, Citation2021; Fung et al., Citation2020; Yang et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2019). Braun (Citation2017) in his research results, shows that even though narcissistic CEOs pay little attention to other people, they are charismatic leaders who dare to communicate their vision and invest in technological innovation. Some of the results of this research show that narcissistic CEOs also have a role in positively impacting the company.

CEO Narcissism is not the main factor affecting the value of the company. CEO Narcissism will affect the value the policy gives to the company. Yang et al. (Citation2021), in their research, show the moderation of CEO Narcissism in the relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Green Technology Innovation (GTI), stating that CEOs play an important role in decision-making and their characteristics greatly influence strategic choices. The results show that CEO narcissism strengthens the relationship between CSR and GTI. Giving dividends is also a company policy that the leader decides. The CEO’s behavior will also influence dividend policy, so in this case, CEO Narcissism will provide a moderating effect on the relationship between dividend policy and firm value.

H2.

CEO Narcissism moderates the effect of dividend policy and firm value.

3. Data and research Method

3.1. Data collection and procedures

This study aimed to examine the relationship between dividend policy and firm value, as well as the moderating effect of CEO Narcissism on this relationship. We take data from companies consistently included in the Kompas 100 Index from 2011 to Citation2019. The Kompas 100 Index was chosen as research data because the Kompas 100 Index consists of companies with good fundamentals and performance, high liquidity, and large market capitalization so that the tendency to give dividends to shareholders becomes greater. A total of 47 companies were used to answer the hypotheses that were built.

This study will use multiple regression analysis to see a direct relationship between dividend policy and CEO Narcissism on firm value. In addition, an analysis was conducted using Moderated Regression Analysis (MRA) to see the moderating effect of CEO narcissism on the relationship between dividend policy and firm value. Moderation, according to Sharma et al. (Citation1981) divided into four types, namely:

Pure moderator: if there is an interaction with predictor variable, but not related to criterion and predictor

Quasi Moderator: if there is an interaction with predictor variable, and related to criterion and/or predictor

Homologizer: if there is no interaction with predictor variable, and not related to criterion and predictor

Predictor:if there is no interaction with predictor variable, and related to criterion and/or predictor

In addition, we carried out a robustness check to ensure the robustness of this research model. Robustness checks are carried out using another proxy for measuring firm value, namely Tobin’s Q. In addition, this study gives a score of 1 for companies that pay dividends, and zero otherwise, as a proxy for dividend policy for the robust test. Robustness checks are also carried out to see modifications to the proxy for measuring CEO narcissism that we made using the number of CEO photos in the annual report. Finally, this research examines the endogeneity problem by conducting the Granger causality test.

3.2. Variable measurement

3.2.1. Dependent variable: Firm value

Firm value is one indicator in describing the condition of the company. To determine company value, several measurement proxies that can be used are Market to Book Value (MBV) and Tobin’s Q (Brigham & Houston, Citation2006). Therefore, we conduct a primary test of firm value using the approach described by Fama and French (Citation2002) which uses Market to Book Value (MBV). As a test for the robustness of the model, this study use Tobin’s Q as a proxy for firm value. We measures Tobin Q using the sum of market value of equity and the book value of total debt to the book value of total assets (Likitwongkajon & Vithessonthi, Citation2020; Sisodia et al., Citation2021).

3.2.2. Independent variable: Dividend policy

A dividend policy is a decision made by management to distribute cash taken from company profits to shareholders. Dividend policy is driven by profits earned in the previous year and can lead companies to develop (Lintner, Citation1956; Pruitt and Gitman, Citation1991). Dividend policy indicators that can be used are earning per share, dividend yield, and dividend payout ratio (Baskin, Citation1989). In this study, the dividend payout ratio (DPR) is proxied as a measure of dividend policy following the research of Holder et al. (Citation1998), because, according to him, the dividend payout is measured annually and smoothed mathematically.

3.2.3. Moderating variable: CEO narcissism

In addition to the dependent and independent variables, this study proposes CEO Narcissism as moderation variable. CEO Narcissism is a psychological character characterized by the need for recognition and appreciation. It is carried out using the power it has in companies often associated with information asymmetry (Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007, Citation2011). The results of this study will also show how CEO Narcissism gives moderation, whether as a pure moderator, quasi-moderator, homologized, or predictor (Sharma et al., Citation1981).

This study uses a proxy in Chatterjee and Hambrick (Citation2007), which measures CEO narcissism with a CEO photo score listed in the annual report, with the following criteria:

Score 4: if there is a CEO’s photo that occupies a full pageScore 3: if there is a photo of the CEO himself with a half-page sizeScore 2: if the CEO takes a photo with the board of directorsScore 1: if there is no photo of the CEO

Photos are a reasonable approach to measuring a person’s level of narcissism. In the world of psychology itself, the character of narcissism is marked by the level of photo publication, where the more often someone publishes his photo, the stronger the person’s narcissistic character. Using this approach, we modify the measure of narcissism, which uses photo size, to be the number of CEO photos in the annual report as the robust check proxy.

3.2.4. Control variable

The control variables in this study consist of firm size (Ln_size), firm age (Firm_Age), leverage (Lev), profitability (ROA), CEO Age (CEO_Age), CEO education (CEO_Edu), CEO gender (CEO_Gen), and CEO tenure (CEO_Ten). Previous research found a positive relationship between firm size and value (Berger & Bonaccorsi di Patti, Citation2006; Diantimala et al., Citation2021; Vo & Ellis, Citation2017). The firm size variable is measured using the natural logarithm of the company’s total assets (LnSize). In the company age variable, the number of years the company has been established since its establishment is used. Leverage is using borrowed funds to increase returns in a business or investment. Jihadi et al. (Citation2021) found leverage to be significant on firm value, and Fosu et al. (Citation2016) oncluded that leverage has a significant negative relationship with firm value. Profitability is the most commonly seen ratio to determine investment. The higher the value of profitability, the better the company’s performance. Jihadi et al. (Citation2021) found that profitability affects firm value. In this study, profitability is the control variable measured using Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Equity (ROE). The demographic characteristics of CEOs have also been widely studied concerning firm value (Borghesi et al., Citation2016; Cline & Yore, Citation2016; Li & Singal, Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2016; Sheikh, Citation2018). CEO_Age is measured using CEO age; CEO_Edu is measured by a dummy score, where 1 is given to CEOs with economics education, and 0 is given to CEOs without economics education. CEO_Gen was measured using a dummy with a score of 1 for male CEOs and 0 for female CEOs. Finally, CEO_Ten is measured by the years the CEO has experienced as a company leader. The details for all variables used in this study are reported in Appendix A.

4. Results and discussions

4.1. Descriptive statistics

This study tested the variables using Stata software. Of the 47 companies consistently included in the Kompas 100 Index, 423 data can be used and processed to answer the hypotheses that have been designed. Variable descriptions are presented in Appendix A to see in detail the variables used along with the notations, descriptions and references used. Table summarises descriptive statistics on all the variables tested in the research model. It can be seen that companies in the Kompas 100 Index from 2011 to Citation2019 have an MBV level with a minimum value of −1,685 and a maximum value of 82,444. Furthermore, the mean is 3,521 and is smaller than the standard deviation of 7,992, indicating that the MBV is relatively high in the distribution of companies in this index. In line with MBV, Tobin’s Q as a robustness check also has an average of 1,474 with a standard deviation of 2,516.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Dividend policy, as measured by dividend payout, on average 34,084 companies pay dividends to shareholders. A standard deviation value of 28,848 illustrates that dividend payout is relatively low dispersed among firms on the compass index of 100. Likewise, with the moderation used, the mean and standard deviation values of CEO Narcissism as measured by Chatterjee and Hambrick (Citation2007) (CEO_CH) approach, respectively −3.161 and 0.92 in the range 1 to 4, so it can be concluded that the narcissistic character of a CEO in the companies in this index has a homogeneous distribution of data. Narcissim’s CEO proxy in the form of the number of photos (CEO_PIC) is also spread homogeneously. The control variables, namely size (SIZE), financial leverage (LEV), Firm age (FIRM_AGE), CEO gender (CEO_GEN), CEO tenure (CEO_TEN), and CEO education (CEO_EDU), have a good data distribution. At the same time, the two profitability ratios and company age as a measure of profitability are spread with an extensive distribution—higher data.

We also present information related to descriptive statistics by year (appendix B) and summary statistics of the average company per year (appendix C). In general, the company value proxied by MBV and Tobin’s Q is in the positive range, which means that companies that are consistently in the compass 100 index are chosen because of good company fundamentals. Furthermore, the DPR, a proxy for dividend policy, has a positive value ranging from 30.99 to 38.53. CEO_CH and CEO_Photo are also in the positive range of 2.57 to 3.53. All control variables also show a range of positive numbers that tend to be homogeneous every year. Appendix C shows that of the 47 companies consistently on the Kompas 100 Index from 2011 to Citation2019, the data is spread homogeneously with the condition that the mean value each year is greater than the standard deviation, except in 2018 and 2019. The minimum value and maximum, respectively, are −45.98 to 0 and 96.80 to 224.80.

4.2. Correlation matrix

Table describes the findings of the Pairwise Correlation Matrix among the variables used. As seen, firm value in the form of MBV and Tobin’s Q as proxies for measuring firm value is positively and significantly correlated with DPR, Total Dividend, Profitability ratio, firm age and firm age at the 10% level. The profitability ratios of ROA and ROE consistently correlate significantly positively with all proxies for measuring dependent and independent variables. Although the results show several significant correlations between the independent variables, the matrix shows that the correlations are not strong (<0.80), implying that multicollinearity is not the case (Kennedy, Citation2008).

Table 2. Pairwise correlations

4.3. Main results

The test results in Table show a significant value so that the proposed hypothesis is supported, with year and industry-fixed effects. The test results for the Model 1 show that the DPR has a significant positive effect on MBV (coefficient of 0.028 at a significance level of 1 percent), so the first hypothesis is supported. In addition, the control variables showed that ROA, ROE, LEV, FIRM_AGE, and CEO_EDU had a significant positive effect on MBV (coef. 0.229, p < 0.01; coefficient 0.137, p < 0.05; coefficient 0.084, p < 0.01); coef. 0.052, p < 0.01, coefficient. 0.908, p < 0.1), while SIZE and CEO_TEN have a significant negative effect on MBV (coef. −0.582, p < 0.05; coef. −0.055, p < 0.01).

Table 3. Main results

Model 2 and Model 3 shows the results of direct testing and the moderating variable interaction (CEO_CH) concerning MBV. Column 2 shows the direct effect of the moderating variable (CEO_CH) on MBV. The results show that CEO_CH does not affect MBV directly (coef. 0.273, p > 0.1). The third column, which describes the interaction between the DPR and CEO_CH on MBV, shows a value of 0.027 with p < 0.1, which illustrates a significant positive effect between this interaction on MBV, so the second hypothesis of this study is supported. The positive direction indicates that the role of CEO_CH in this model is the moderator that strengthens the DPR’s relationship with MBV. Referring to Sharma et al. (Citation1981), CEO_CH is a moderator that strengthens the DPR’s relationship with MBV.

In particular, moderating variables can strengthen, weaken, and reverse or change the relationship (Aguinis et al., Citation2016; Andersson et al., Citation2014; Gardner et al., Citation2017; Reuben & David, Citation1986). In Model 3 Table , it appears that the coefficient of influence of DPR towards Firm Value experienced a change to negative, but not significant. A shift in the direction and significance of the coefficient can occur when there is an interaction between predictor and moderating variables. Reverse interaction not only describes strengthening or weakening but also describes the reversal effect that occurs when the independent and dependent relationship variables change direction and significance, which is also known as the crossover interaction effect, which, according to the label, is shown by an “X” pattern when plotted (Cohen et al., Citation2002).

This research proves that interaction is the dominant influence on company value, and supports the role of CEO Narcissism intervention in strengthening the results of the company’s dividend policy, evidenced by a coefficient value of 0.027 at a significance level of 10 per cent. Linked to the data processing results in this research, the reversing effect occurs because CEO Narcissism is a powerful moderating variable in the relationship between dividend policy and company value. The CEO has a sizeable narcissistic character (this is known from the mean CEO_CH of 3.161 and the median value of 2.5) so that when the information that a narcissistic CEO leads the company becomes public, the dividend policy (DPR) becomes insignificant, following research results from Aabo et al. (Citation2020), that the market will react negatively to companies led by CEOs with narcissistic characteristics. The public will view the dividend policy as a gimmick to gain a good reputation. However, as explained by Braun’s (Citation2017) research results, CEOs with narcissistic characteristics are reliable communicators. In the end, the CEO can convince the public that the company’s dividend policy will provide positive returns for stakeholders so that the dividend policy can create value for the company.

4.4. Robustness test

To strengthen the main result, we tested again using several other proxies. As the first alternative, we examine the effect of dividend policy and moderation of CEO Narcissism on firm value using TOBIN’S Q. In the next test, we use a dummy value for dividend distribution (DUM_DIV) as a proxy for dividend policy, with a score of 1 if the company distributes dividends and 0 otherwise. The next alternative is done by modifying the CEO photo measurement Chatterjee and Hambrick (Citation2007) to be the number of CEO photos in the annual report. We conducted the last test to ensure that endogeneity problems do not occur, namely the Granger causality test.

4.4.1. Alternative measurement for firm value

Table is the result of Tobin’s Q test as another proxy for the dependents of this study. The first model shows that the DPR with a constant of 0.010 can influence positively at a significance level of 1 percent (p < 0.01). As a control, SIZE significantly negatively affects Tobin’s Q at a p-value level of less than 0.05 (coef. −0.170). In contrast, ROA, ROE, LEV, and FIRM_AGE have a positive and significant effect on Tobin’s Q at a level of 1% and 5% (coefficient 0.100, p < 0.01; coefficient 0.032, p < 0.05; coefficient 0.021, p < 0.01; 0.014, p < 0.01); On the demographic characteristics of the CEO, education level is known to have a significant positive effect with a value of 0.523 at the 1% level. CEO_CH as a moderator also acts as a pure moderator, which is shown by the direct effect test, which has no effect (coef. 0.037, p > 0.1), while the interaction test produces a significant effect (coef. 0.008, p < 0.05). Added again, by looking at the positive direction, it can be concluded that CEO_CH acts as a pure moderator that strengthens the relationship between the DPR and TOBIN’S Q, and this result also succeeded in supporting the main result.

Table 4. Robustness test

4.4.2. Alternative measurement for dividend policy

The next robustness check is carried out by using scores of 1 and 0 for dividend distribution (Dum_Div) as another proxy measure of the dividend policy. A score of 1 is given if the company distributes dividends and 0 otherwise. Tests were conducted to see the effect on firm value (MBV and TOBIN’S Q) in Table , model 4 tests the effect of DUM_DIV on MBV, while model 7 tests the effect of Dum_Div on TOBIN’S Q. The test results show that Dum_Div in models 4 and 7 has a coefficient value of 0.031 and 0.405 respectively and is significant with a p-value below 1 percent. It can be concluded that Dum_Div also shows a positive significant relationship to firm value, both measured by MBV and TOBIN’S Q.

4.4.3. Alternative measurement for CEO narcissism

The next model robustness test changes the proxy moderation variable to the number of CEO photos in the annual report (Tot_Pic). Table Model 11 and Model 14 show a direct relationship between Tot_Pic and MBV and TOBIN’S Q, where the coefficients are 0.148 and 0.029, respectively, with a p-value greater than 10 percent, so it can be stated that it has no effect. Meanwhile, model 12 and model 15 show the interaction test of Tot_Pic with the DPR and its effect on MBV and TOBIN’S Q. The results show that the interaction between Tot_Pic and the DPR has a coefficient value of 0.027 and 0.008, respectively. The p-value is less than 5 percent (p < 0.05), so it can be concluded that Tot_Pic is a pure moderator that strengthens the relationship between dividend policy and firm value, both with MBV and TOBIN’S Q.

4.4.4. Endogeneity test

As an additional analysis of the robustness of the model, this study conducted a Generalized Moment of Method (GMM) test to ensure endogeneity issues. GMM is a test performed to overcome the endogeneity issues. The endogeneity problem is that there is a bias between the independent variables and the error term. From the Table model 16–21, the results of the Sargan test are more significant than the 5 percent significance level. This means that the instruments used in this study are valid, so the model is endogeneity free overall. Meanwhile, all AR2 probability values also show values above the 5 percent significance level, which says that the estimation results are robust, unbiased, and there is no autocorrelation. The results of this test are consistent with the main results, where the DPR as a measurement of dividend policy has a positive effect on firm value, both in terms of MBV and Tobin’s Q. This study also proves the emphasis on CEO narcissism, where CEO Narcissism is shown to play a role as pure moderation that strengthens the dividend policy relationship to company value.

Table in model 16 and model 19 shows that the lag value (−1) of firm value has a significant positive effect on the solid deal with a significance level of 1 percent each on MBV and Tobin’s Q (coefficient 0.213 and 0.101 at level 1 percent). It can be concluded that matters from the previous period influence substantial value. DPR, in conclusion, also has a significant positive effect (coefficient 0.009 and 0.011 at level of 5 percent and 1 percent). Meanwhile, models 17 and 20 show that CEO narcissism does not directly impact firm value. Models 18 and 21 show a positive influence of interaction between DPR and CEO Narcissism on substantial value (coef. 0.019 and 0.003 at a significance level of 1 percent and 5 percent), so it is concluded that CEO Narcissism is pure moderation in this model. The results in Table support the main result, which shows a significant positive effect of DPR on value companies and CEO Narcissism as a moderating variable.

5. Discussions

There are two objectives in this study: to identify the influence of dividend policy on firm value and to see the interaction effect of dividend policy with CEO narcissism on firm value. Associated with the Behavioral Theory of the Firm, a policy that is made and implemented must provide added value to the company. As one of the policies that will affect the investment decision of a fund owner, the effect of the dividend policy will appear in changes in the value of the company itself.

Following the first hypothesis built, the data processing results show that the first hypothesis is supported (Table ). The results show a significant positive effect of dividend policy on firm value. This result is strengthened by a robust analysis using other proxies on dividend policy and firm value, and also by using generalized method of moment (GMM). This research proves that if management makes the right policies, it will impact the company. As one of the returns expected by fund owners, dividend distribution is very important for companies to pay attention to because dividend distribution will certainly affect the company’s operations, considering that there are funds that must be issued and not for company affairs. However, giving dividends is also very important to provide a signal to raise the interest of fund owners in investing in the company. Examination of the robustness of GMM in Table shows that the value of the firm depends on the value of the firm in the previous period. This test also supports the main results which state that dividend policy is a factor that can increase firm value. Furthermore, CEO Narcissism also acts as a pure mediator who can strengthen the effect of a positive dividend policy on firm value.

We conclude that this study supports the signaling theory, which states that dividends are a positive signal that shareholders are interested in because dividends can describe management’s ability to provide returns so that it will attract other investors to invest in the company, which in turn provides added value to the company. We also confirm that based on Kompas 100 Index data, there is a reaction to the changes that occur whenever there is a change in the dividends paid.

This result is also in line with the results of previous studies, which state that dividends significantly positively affect market reactions which can be seen from the value of the firm (Baker et al., Citation2006, Citation2012; Braouezec & Lehalle, Citation2010; Hoffmann, Citation2014; Kim et al., Citation2020; Lee & Lee, Citation2019; Yusof & Ismail, Citation2016). Furthermore, Azeem Qureshi (Citation2007) states that dividend policy is a prerequisite for maximizing value and influencing the welfare of shareholders (Ozuomba et al., Citation2016). Therefore, the distribution of dividends is a form of the company’s commitment to fulfilling the wishes of shareholders so that it will cause a positive reaction from the owners of capital, which in turn will have a positive impact on increasing the value of the company. This result is robust and in line with the use of another dividend policy proxy, namely the dummy dividend, which shows a significant positive relationship to firm value both measured by MBV and TOBIN’S Q as another proxy of firm value (Table model 4 and model 7).

The second hypothesis of this study examines the moderating effect of CEO Narcissism on the effect of dividend policy on firm value. Behavioral Theory of Firms has shown that in the policy-making process, there are factors such as rational and irrational, and one of them is power. A CEO, as the highest decision maker in a company, can create a policy distorted by the influence of his interests, and narcissism becomes one of the personal problems that can enter and affect the outcome of the company’s policies. Narcissism is a conditional factor that not all CEOs have, so it is ideal as a moderating variable.

This study found that CEOs with narcissistic characteristics can strengthen the results of dividend policy in increasing firm value by acting as pure moderation. This result is robust when measuring CEO Narcissism using the number of CEO photos as a modification of the main measurement. The results align with research by Yang et al. (Citation2021) which shows the function of CEO Narcissism as a moderator in the relationship between CSR performance and Green Technology Innovation, and Zhu and Chen (Citation2015) which found moderation of CEO Narcissism in strengthening CEO experience of business strategy, but weakens the relationship of the board’s experience to business strategy at the same time.

Previous research also has shown the direct positive influence of CEO Narcissism on a variety of topics. Brunzel (Citation2021), states that CEO Narcissism has positive implications, at least for the results of the company’s innovations, and is also in line with research results regarding other CEOs of Narcissism which have a positive influence on companies (Byun & Al-shammari, Citation2021; Fung et al., Citation2020; Marquez-Illescas et al., Citation2019; Schmid et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021; Zhou et al., Citation2019). Thus, this research is the first study to show the moderating effect of CEO Narcissism on the relationship between dividend policy and firm value.

It can be concluded that CEO Narcissism does not permanently harm the company, such as previous research looked at the narcissistic character of a CEO (Agnihotri, Citation2021; Buyl et al., Citation2019; Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007, Citation2011; Ham et al., Citation2018). Lee et al. (Citation2020) stated that the CEO is an intangible asset. Shareholders who are getting smarter in deciding to invest because they are supported by the ease of obtaining information related to the company also see the company’s management, including their background and achievements. The CEO’s photo on display will be equipped with the demographic information of the CEO so that if the public sees the CEO’s education, experience, or achievements, it will give them the confidence to invest in the company.

In control, the profitability ratio proved to affect firm value positively. The profitability ratio consisting of ROA and ROE is the ratio to be considered in making investment decisions. This study’s results align with previous research showing the effect of ROA and ROE on firm value (Asni & Agustia, Citation2021; Deswanto & Siregar, Citation2018; Setiawanta et al., Citation2021). The company’s maturity level also affects the company’s value, where the more mature the company, the better the company’s value. Leverage also has a positive influence on firm value. Zhang et al. (Citation2021) in his research, stated that CEOs with narcissistic characteristics have a positive correlation with debt financing. Companies to get loan funds are influenced by good credibility, and CEOs with narcissistic characters can meet these needs. In terms of CEO demographics, it is known that several factors are considered and play a role in increasing company value, including the tenure of the CEO and CEO education (Li & Singal, Citation2019). Shareholders are getting smarter in convincing themselves about what to pay attention to when making investment decisions. An experienced and educated CEO will know his job better, so he knows the proper steps or policies for the company to take. Shareholders believe this more than age, which measures the level of maturity and gender of the CEO.

6. Conclusion

Dividend policy is one thing that gets special attention from both management and stakeholders, especially shareholders. Policies are related to decisions to give, add, reduce, or even not give dividends and are believed to affect the company’s value. Answering the phenomenon of an increase in the Composite Index that is not in line with the company’s value on the Indonesian Stock Exchange’s Kompas 100 Index becomes a question of whether dividends are still the return expected by shareholders. Companies need to pay attention.

Empirically, this study supports the concept of the behavioral theory of the firm, which explains the importance of management in making policies that add value to the company, as well as looking at the influence of behavioral elements in the preparation of these policies. As with dividend policy, giving dividends to shareholders must be carried out with deep considerations, bearing in mind that giving dividends is a company expense. This study found that dividend policy can provide a positive value for the company. The company provides an overview of the success of good fund management and provides the expected return by shareholders. In line with the results of previous research, this study shows consistency in signaling theory as a signal that is favored by shareholders and has an impact on increasing firm value (Baker & Powell, Citation2000; Baker et al., Citation1999, Citation2006, Citation2012; Salteh, Citation2013; Tahir et al., Citation2020; Tyastari et al., Citation2017; Yousaf et al., Citation2019).

Behavioral Theory of the Firm also explained that formulating policies through mixing things is rational and irrational, influenced by other factors: power. As the highest decision maker, the CEO can include his/her issues, one of which is depicted in the narcissistic character. Even though it does not permanently harm the company, the behavioral aspect is essential to pay attention to ensure that the company is run by a CEO who prioritizes fulfilling company goals above his personal goals. Higgs (Citation2009) menyatakan bahwa sifat pemimpin merupakan faktor yang lebih signifikan dibandingkan keterampilan tidak memadai dalam menciptakan kepemimpinan yang buruk.

This research indicates that CEO Narcissism strengthens the impact of dividend policy on firm value. This study proves that CEO Narcissism is ideal as a moderator that strengthens the value generated by policies for the company. Even so, there is still a view that even though CEO Narcissism has a positive influence, in the long term it will damage the organization from within, such as damaging culture, morals, and relationships, so that in the end it will reduce performance (Higgs, Citation2009).

This study is the first study that test the moderation effect of CEO Narcissism on the relationship between dividend policy and firm value, where previous studies tested the moderating effect of CEO Narcissism on CSR and innovation (Yang et al., Citation2021), and also in relationship between experience on business strategy (Zhu & Chen, Citation2015), and the rest show the direct effects of CEO Narcissism (Aktas et al., Citation2016; Al-Shammari et al., Citation2019; Bajo et al., Citation2021; Buyl et al., Citation2019; Chatterjee & Hambrick, Citation2007, Citation2011; Ham et al., Citation2018; Ingersoll et al., Citation2019; Mahmood et al., Citation2020; Tang et al., Citation2018; Yook & Lee, Citation2020).

This study contributes theoretically to develop a behavioral theory of the firm, which explains the importance of looking at behavioral elements in influencing the outcomes of policies and companies. From a practical perspective, this study contributes to directing well-targeted policymaking. Companies must consider many factors, including behavior in deciding to use a policy and the impact on the company, especially in the context of the Indonesian stock market which is very attractive because its growth is not in line with transaction growth and company value.

This study has theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, this research supports the signaling theory regarding dividend policies that provide added value to companies. This study also contributes theoretically to the debate regarding the effect of narcissistic character on decision-makers such as CEOs by exploring its influence on the relationship between strategy and firm value. This result strengthens the perspective on narcissism that is considered necessary as the result of this study, that CEOs with narcissistic characteristics can increase the added value of dividend policy. From a practical standpoint, a business must be able to sell what the business has, including the demographics of people who play an essential role in the company. This perspective is also one of the aspects that will provide benefits in the form of the emergence of public trust in business decisions.

This research has several limitations. It is known that the CEO Narcissism measure has been created as a proxy measure on data like this second study. For further studies, it is also possible to explore narcissism of CEO as describe in Gupta and Spangler (Citation2012), that distinguishes narcissism into three categories namely dominance narcissism, extraverted narcissism, and neurotic narcissism. Next study also can see the impact of CEO Narcissism in long term. Some are deemed more appropriate in reflecting narcissism, but we cannot use them due to the disclosure of information in Indonesia. Furthermore, the sample for this study is 47 issuers in the Kompas Index 100. Future research can use a larger sample and compare industries to see the potential for a more significant dividend policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aabo, T. (2021). Watch me go big: CEO narcissism and corporate acquisitions. Review of Behavioral Finance, 13(5), 465–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-05-2020-0091

- Aabo, T., Als, M., Thomsen, L., & Wulff, J. N. (2020). Watch me go big: CEO narcissism and corporate acquisitions. Review of Behavioral Finance, 13(5), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-05-2020-0091

- Aabo, T., & Eriksen, N. B. (2018). Corporate risk and the humpback of CEO narcissism. Review of Behavioral Finance, 10(3), 252–273. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-07-2017-0070

- Aabo, T., Hoejland, F., & Pedersen, J. (2020). Do narcissistic CEOs rock the boat?. Review of Behavioral Finance, 13(2), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/RBF-09-2019-0118

- Aabo, T., Jacobsen, M. L., & Stendys, K. (2022). Pay me with fame, not mammon: CEO narcissism, compensation, and media coverage. Finance Research Letters, 46(PB), 102495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102495

- Agnihotri, A. (2021). CEO narcissism and myopic management. Industrial Marketing Management, 97, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.07.006

- Agnihotri, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2019). CEO narcissism and internationalization by Indian firms. Management International Review, 59(6), 889–918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-019-00404-8

- Agnihotri, A., & Bhattacharya, S. (2021). CEO narcissism and myopic management. Industrial Marketing Management, 97(July), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.07.006

- Aguinis, H., Edwards, J. R., & Bradley, K. J. (2016). Improving our understanding of moderation and mediation in strategic Management research. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 665–685. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115627498

- Aktas, N., de Bodt, E., Bollaert, H., & Roll, R. (2016). CEO Narcissism and the takeover process: From private initiation to deal completion. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 51(1), 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109016000065

- Aktas, N., Louca, C., & Petmezas, D. (2019). CEO overconfidence and the value of corporate cash holdings. Journal of Corporate Finance, 54(December 2018), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2018.11.006

- Al-Shammari, M., Rasheed, A., & Al-Shammari, H. A. (2019). CEO narcissism and corporate social responsibility: Does CEO narcissism affect CSR focus? Journal of Business Research, 104(May 2018), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.005

- Andersson, U., Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Nielsen, B. B. (2014). From the editors: Explaining interaction effects within and across levels of analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(9), 1063–1071. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.50

- Anninos, L. (2018). Narcissistic Business leaders as heralds of the self-proclaimed excellence. International Journal of Quality & Service Sciences, 10(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-01-2017-0001

- Asni, N., & Agustia, D. (2021). The mediating role of financial performance in the relationship between green innovation and firm value: Evidence from ASEAN countries. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(5), 1328–1347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-11-2020-0459

- Azeem Qureshi, M. (2007). System dynamics modelling of firm value. Journal of Modelling in Management, 2(1), 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1108/17465660710733031

- Bajo, E., Jankensgård, H., & Marinelli, N. (2021). Me, myself and I: CEO narcissism and selective hedging. European Financial Management, 28(3), 809–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12328

- Baker, H. K., Mukherjee, T. K., & Paskelian, O. G. (2006). How Norwegian managers view dividend policy. Global Finance Journal, 17(1), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2006.06.005

- Baker, H. K., & Powell, G. E. (1999). How corporate managers view dividend policy. Quarterly Journal of Business and Economics, 38(2), 17–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40473257

- Baker, H. K., & Powell, G. E. (2000). Determinants of corporate dividend policy: A survey of NYSE firms. Financial Practice and Education, 10(1), 29–41.

- Baker, H. K., Powell, G. E., & Weaver, D. G. (1999). Does NYSE listing affect firm visibility? Financial Management, 28(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.2307/3666194

- Baker, H. K., Powell, G. E., & Yao, L. J. (2012). Dividend policy in Indonesia: Survey evidence from executives. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 6(1), 79–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/15587891211191399

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2004). A catering theory of dividends. The Journal of Finance, 59(3), 1125–1165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00658.x

- Bakri, M. A., & McMillan, D. (2021). Moderating effect of audit quality: The case of dividend and firm value in Malaysian firms. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.2004807

- Baskin, J. (1989). An empirical investigation of the pecking order hypothesis. Financial Management, 18(1), 26–35.

- Berger, A. N., & Bonaccorsi di Patti, E. (2006). Capital structure and firm performance: A new approach to testing agency theory and an application to the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(4), 1065–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.05.015

- Black, F. (1976). The Dividend Puzzle. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 23(5), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.1996.008

- Blair, C. A., Helland, K., & Walton, B. (2017). Leaders behaving badly: The relationship between narcissism and unethical leadership. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 38(2), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2015-0209

- Bogart, L. M., Benotsch, E. G., & Pavlovic, J. D. (2004). Feeling Superior but threatened: The relation of narcissism to Social Comparison. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 26(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2601_4

- Borghesi, R., Chang, K., & Mehran, J. (2016). Simultaneous board and CEO diversity: Does it increase firm value? Applied Economics Letters, 23(1), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2015.1047082

- Braouezec, Y., & Lehalle, C. A. (2010). Corporate liquidity, dividend policy and default risk: Optimal financial policy and agency costs. International Journal of Theoretical and Applied Finance, 13(4), 537–576. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219024910005929

- Braun, S. (2017). Leader narcissism and outcomes in organizations: A review at multiple levels of analysis and implications for future research. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(MAY), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00773

- Braun, S., Aydin, N., Frey, D., & Peus, C. (2018). Leader Narcissism predicts malicious envy and supervisor-targeted counterproductive work behavior: Evidence from field and experimental research. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3), 725–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3224-5

- Brigham, E., & Houston, J. (2006). Fundamentals of Financial Management. Cengage Learning. https://books.google.co.id/books?id=gLnwwAEACAAJ

- Brown, R. P., Budzek, K., & Tamborski, M. (2009). On the meaning and measure of narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(7), 951–964. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167209335461

- Brunzel, J. (2021). Overconfidence and narcissism among the upper echelons: A systematic literature review. In Management review quarterly (vol. 71, issue 3). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00194-6

- Buchholz, F., Jaeschke, R., Lopatta, K., & Maas, K. (2018). The use of optimistic tone by narcissistic CEOs. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31(2), 531–562. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-11-2015-2292

- Buchholz, F., Lopatta, K., & Maas, K. (2020). The deliberate engagement of narcissistic CEOs in earnings Management. Journal of Business Ethics, 167(4), 663–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04176-x

- Budagaga, A. R. (2021). The validity of the irrelevant theory in Middle East and North African markets: Conventional banks versus Islamic banks. Journal of Financial Economic Policy, 14(4), (ahead-of–print). https://doi.org/10.1108/jfep-06-2021-0148

- Buyl, T., Boone, C., & Wade, J. B. (2019). CEO narcissism, risk-taking, and resilience: An empirical analysis in U.S. Commercial banks. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1372–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317699521

- Byun, K. A.,& Al-Shammari, M. (2021). When narcissistic CEOs meet power: Effects of CEO narcissism and power on the likelihood of product recalls in consumer-packaged goods. Journal of Business Research, 128(January), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.02.001

- Carnahan, S., Agarwal, R., & Campbell, B. (2010). The effect of firm compensation structures on the mobility and entrepreneurship of extreme performers. Business, (October), 1–43. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1555659

- Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2007). It’s all about me: Narcissistic chief executive officers and their effects on company strategy and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(3), 351–386. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.3.351

- Chatterjee, A., & Hambrick, D. C. (2011). Executive Personality, capability cues, and risk taking: How narcissistic CEOs react to their successes and stumbles. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56(2), 202–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839211427534

- Chatterjee, A., & Pollock, T. G. (2017). Master of puppets: How narcissistic CEOs construct their professional worlds. Academy of Management Review, 42(4), 703–725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0224

- Chiu, J., Chen, C. H., Cheng, C. C., & Hung, S. C. (2021). Knowledge capital, CEO power, and firm value: Evidence from the IT industry. The North American Journal of Economics & Finance, 55(xxxx), 101012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2019.101012

- Cline, B. N., & Yore, A. S. (2016). Silverback CEOs: Age, experience, and firm value. Journal of Empirical Finance, 35, 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2015.11.002

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2002). In In D. Riegert (Ed.). Applied multiple Regression/Correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). (pp. 255–272). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203774441/Lawrence

- Cormier, D., Lapointe-Antunes, P., & Magnan, M. (2016). CEO power and CEO hubris: A prelude to financial misreporting? Management Decision, 54(2), 522–554. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2015-0122

- Cragun, O. R., Olsen, K. J., & Wright, P. M. (2020). Making CEO narcissism research great: A Review and meta-analysis of CEO narcissism. Journal of Management, 46(6), 908–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319892678

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. (N. Englewood Cliffs, Ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Deswanto, R. B., & Siregar, S. V. (2018). The associations between environmental disclosures with financial performance, environmental performance, and firm value. Social Responsibility Journal, 14(1), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1108/SRJ-01-2017-0005

- Diantimala, Y., Syahnur, S., Mulyany, R., & Faisal, F. (2021). Firm size sensitivity on the correlation between financing choice and firm value. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1926404

- Dinh Nguyen, D., To, T. H., Nguyen Van, D., & Phuong Do, H. (2021). Managerial overconfidence and dividend policy in Vietnamese enterprises. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1885195

- Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11

- Fairchild, R. (2010). Dividend policy, signalling and free cash flow: An integrated approach. Managerial Finance, 36(5), 394–413. https://doi.org/10.1108/03074351011039427

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2002). Testing trade-off and pecking order predictions about dividends and debt. Review of Financial Studies, 15(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/15.1.1

- Fosu, S., Danso, A., Ahmad, W., & Coffie, W. (2016). Information asymmetry, leverage and firm value: Do crisis and growth matter? International Review of Financial Analysis, 46, 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2016.05.002

- Fung, H. G., Qiao, P., Yau, J., & Zeng, Y. (2020). Leader narcissism and outward foreign direct investment: Evidence from Chinese firms. International Business Review, 29(1), 101632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101632

- Galasso, A., & Simcoe, T. S. (2011). CEO overconfidence and innovation. Management Science, 57(8), 1469–1484. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1374

- Gao, Y., & Han, K. S. (2020). Managerial overconfidence, CSR and firm value. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting and Economics, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/16081625.2020.1830558

- García-Meca, E., Ramón-Llorens, M. C., & Martínez-Ferrero, J. (2021). Are narcissistic CEOs more tax aggressive? The moderating role of internal audit committees. Journal of Business Research, 129(February), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.02.043

- Gardner, R. G., Harris, T. B., Li, N., Kirkman, B. L., & Mathieu, J. E. (2017). Understanding “it depends” in organizational research: A theory-based Taxonomy, Review, and future research agenda concerning interactive and quadratic relationships. Organizational Research Methods, 20(4), 610–638. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117708856

- Gupta, A., & Spangler, W. D. (2012). The effect of CEO narcissism on firm performance. Academy of Management Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2012.14971abstract

- Hamori, M., & Kakarika, M. (2009). External labor market strategy and career success: CEO careers in Europe and the United States. Human Resource Management, 48(3), 355–378. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20285

- Ham, C., Seybert, N., & Wang, S. (2018). Narcissism is a bad sign: CEO signature size, investment, and performance. Review of Accounting Studies, 23(1), 234–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9427-x

- Hayward, M. L. A., Rindova, V. P., & Pollock, T. G. (2004). Believing one’s own press: The causes and consequences of CEO celebrity. Strategic Management Journal, 25(7), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.405

- Higgs, M. (2009). The good, the bad and the ugly: Leadership and Narcissism. Journal of Change Management, 9(2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879111

- Hoffmann, P. S. (2014). Internal corporate governance mechanisms as drivers of firm value: Panel data evidence for Chilean firms. Review of Managerial Science, 8(4), 575–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-013-0115-3

- Holder, M. E., Langrehr, F. W., & Hexter, J. L. (1998). Dividend policy Determinants: An investigation of the influences of stakeholder theory. Financial Management, 27(3), 73. https://doi.org/10.2307/3666276

- Hunjra, A. I., Ijaz, M. S., Chani, M. I., Hassan, S. U., & Mustafa, U. (2014). Impact of Dividend Policy, Earning per Share, Return on Equity, Profit after Tax on Stock Prices PhD Scholar, National College of Business Administration. 2, 109–115.

- Ingersoll, A. R., Glass, C., Cook, A., & Olsen, K. J. (2019). Power, status and expectations: How Narcissism manifests among women CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(4), 893–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3730-0

- Jihadi, M., Vilantika, E., Hashemi, S. M., Arifin, Z., Bachtiar, Y., & Sholichah, F. (2021). The effect of liquidity, leverage, and profitability on firm value: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics & Business, 8(3), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1920116

- Kennedy, P. (2008). A Guide to econometrics (Sixth Edition (6th ed.). Blackwell Publisher Ltd.

- Kim, T., & Kim, I. (2020). The influence of credit scores on dividend policy: Evidence from the Korean market. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics & Business, 7(2), 33–42. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no2.33

- Kim, J. M., Yang, I., Yang, T., & Koveos, P. (2020). The impact of R&D intensity, financial constraints, and dividend payout policy on firm value. Finance Research Letters, 40(October 2020), 101802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2020.101802

- Kontesa, M., Brahmana, R., & Tong, A. H. H. (2021). Narcissistic CEOs and their earnings management. Journal of Management & Governance, 25(1), 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09506-0

- Kouaib, A., Bouzouitina, A., & Jarboui, A. (2021). CEO behavior and sustainability performance: The moderating role of corporate governance. Property Management, 40(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1108/PM-01-2021-0009

- Kucharska, W., & Mikołajczak, P. (2018). Personal branding of artists and art-designers: Necessity or desire? Journal of Product & Brand Management, 27(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-01-2017-1391

- Lee, G., Cho, S. Y., Arthurs, J., & Lee, E. K. (2020). Celebrity CEO, identity threat, and impression management: Impact of celebrity status on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Research, 111(January), 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.015

- Lee, N., & Lee, J. (2019). R & D intensity and dividend policy: Evidence from South Korea’s biotech firms. Sustainability, 11(18), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11184837

- Likitwongkajon, N., & Vithessonthi, C. (2020). Do foreign investments increase firm value and firm performance? Evidence from Japan. Research in International Business and Finance, 51(September 2019), 101099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.101099

- Li, F., Li, T., & Minor, D. (2016). CEO power, corporate social responsibility, and firm value: A test of agency theory. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 12(5), 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-05-2015-0116

- Lin, F., Lin, S. W., & Fang, W. C. (2020). How CEO narcissism affects earnings management behaviors. The North American Journal of Economics & Finance, 51, 101080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2019.101080

- Lintner, J. (1956). Distribution of incomes of corporations among dividends, retained earnings, and taxes. The American Economic Review, 46(2), 97–113.

- Lintner, J. (1962). Dividends, earnings, leverage, stock prices and the supply of capital to corporations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 44(3), 243–269. https://doi.org/10.2307/1926397

- Li, Y., & Singal, M. (2019). Firm performance in the hospitality industry: Do CEO attributes and compensation matter? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 43(2), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348018776453

- Mahmood, F., Qadeer, F., Sattar, U., Ariza-Montes, A., Saleem, M., & Aman, J. (2020). Corporate social responsibility and firms’ financial performance: A new insight. Sustainability, 12(10), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104211

- Marquez-Illescas, G., Zebedee, A. A., & Zhou, L. (2019). Hear me write: Does CEO Narcissism affect disclosure? Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 401–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3796-3

- Mehdi, M., Sahut, J.-M., & Teulon, F. (2017). Do corporate governance and ownership structure impact dividend policy in emerging market during financial crisis?. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 18(3), 274–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAAR-07-2014-0079

- Miller, J. D., Campbell, W. K., Pilkonis, P. A., & Morse, J. Q. (2008). Assessment procedures for narcissistic Personality disorder. Assessment, 15(4), 483–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191108319022

- Miller, M. H., & Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. The Journal of Business, 34(4), 411–433. https://doi.org/10.1086/294442

- Nevicka, B., Ten Velden, F. S., de Hoogh, A. H. B., & van Vianen, A. E. M. (2011). Reality at odds with perceptions: Narcissistic leaders and group performance. Psychological Science, 22(10), 1259–1264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417259

- Oesterle, M. J., Elosge, C., & Elosge, L. (2016). Me, myself and I: The role of CEO narcissism in internationalization decisions. International Business Review, 25(5), 1114–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.02.001

- Ohlson, J., & Johannesson, E. (2016). Equity value as a function of (eps1, eps2, dps1, bvps, beta): Concepts and realities. Abacus, 52(1), 70–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12065

- Ozuomba, C. N., Anichebe, A. S., Okoye, P. V. C., & Ntim, C. G. (2016). The effect of dividend policies on wealth maximization–a study of some selected plcs. Cogent Business & Management, 3(1), 1226457. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2016.1226457

- Papadakis, V. (2007). Growth through mergers and acquisitions: How it won’t be a loser’s game. Business Strategy Series, 8(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1108/17515630710686879

- Parkinson, A. (2012). Managerial Finance. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080938196

- Pruitt, S. W., & Gitman, L. J. (1991). The interactions between the investment, financing, and dividend decisions of Major U.S. Firms. Financial Review, 26(3), 409–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6288.1991.tb00388.x

- Quinn, J. B. (1985). Innovation and corporate strategy. Managed chaos. Technology in Society, 7(2–3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-791x(85)90029-6

- Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic Personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(5), 890–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.890

- Reuben, M. B., & David, A. K. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

- Rijsenbilt, A., & Commandeur, H. (2013). Narcissus enters the courtroom: CEO Narcissism and fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1528-7

- Roche, M. J., Pincus, A. L., Conroy, D. E., Hyde, A. L., & Ram, N. (2013). Pathological narcissism and interpersonal behavior in daily life. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, & Treatment, 4(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030798

- Salehi, M., Rajaeei, R., & Edalati Shakib, S. (2021). The relationship between CEOs’ narcissism and internal controls weaknesses. Accounting Research Journal, 34(5), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-06-2020-0145