?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examines tourism persistence in a group of Southeastern European (SEE) countries (Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia) by applying fractional integration methods to monthly data on foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays. The results indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the degree of persistence of these series as measured by the fractional differencing parameter; specifically, it has removed the mean reversion property in some countries. In addition, it has reduced the importance of the seasonal component.

1. Introduction

Tourism has been one of the sectors most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, since the border closures and lockdown restrictions adopted by many countries to limit the spread of the virus brought about a huge drop in foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays. An interesting issue is the degree of persistence in the tourism sector, i.e., whether the effects of such shocks are permanent or transitory. Various papers have analyzed this question by carrying out unit root tests (see, e.g., Albaladejo et al., Citation2020; Al-Nsour, Citation2021; Bahmani-Oskoee et al., Citation2021; Narayan, Citation2005; etc.). Some recent studies have applied instead a more general framework allowing the differencing parameter to take fractional as well as integer values. Examples of such studies using fractional integration methods are Claudio-Quiroga et al. (Citation2021), Gil-Alana et al. (Citation2019), Imeri and Gil-Alana (Citation2022a, Citation2022b), Yucel et al. (Citation2022), and Payne et al. (Citation2021), the latter finding that, as a result of the COVID-19 shock, the number of foreign arrivals and overnight stays in Croatia both declined whilst their degree of persistence increased. Other papers investigating the effect of the COVID-19 shock on tourism include Aronica et al. (Citation2022) and Sciortino et al. (Citation2023). The present study analyses the same series for a wider set of Southeastern European countries (SEE) countries for the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. All these countries (Albania, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia) are located at the crossroads of South and South East Europe. Some of them, namely Albania, Croatia, Montenegro and Slovenia, have direct access to the sea. Others, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina (also known as Bosnia) and Bulgaria have only a short coastline giving them access to the Adriatic Sea and the Black Sea respectively. Finally, North Macedonia and Serbia are landlocked.

Prior to the pandemic, the SEE countries had experienced a sharp increase in tourism, being ranked among the fastest emerging tourist attractions by the UNWTO (Citation2019); in particular, by 2018 Albania had recorded 15% year-on-year growth, Bosnia 14.1%, Bulgaria 4.4%, Croatia 6.7%, Montenegro 10.6%, North Macedonia 12.2%, Serbia 14.2% and Slovenia 10.9%.

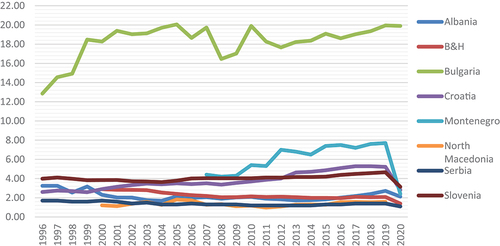

The share of tourism in GDP had also increased in the SEE countries in the two decades before the pandemic, but then dropped in most cases (see Figure ). For instance, in Albania it had reached 2.12% over the period 1996–2020 before dropping (Institute of Statistics Albania, Citation2022); in Bulgaria it had reached 19% by 2020 and it was not significantly affected (National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria, Citation2022); in Slovenia the increasing trend was followed by a sharp drop to 3.14% in 2020 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, Citation2022); in Croatia tourism exhibited an increasing trend over the period 1996–2020, its share of GDP then dropping to 2.8% in 2020 (Croatia Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022); similarly, in Montenegro this share increased over the period 2007–2020 but then fell to 2.4% in 2020 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, Citation2022); in North Macedonia it increased slightly over the period 2000–2019, reaching 1.58% in 2019 according to the most recent figures (State Statistical Office Republic of North Macedonia, Citation2022); by contrast, in Bosnia and Herzegovina there had been a slightly decreasing trend, with a sharper fall to 1.39% in 2020 (Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Citation2022), and the same applies to Serbia, where this share had been slightly decreasing over the period 1996–2020, reaching 1.1% in 2020 (Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Citation2022).

The main objective of this study is to establish if shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic have had permanent or transitory effects on the evolution of the series. For this purpose we use a long memory framework, specifically a fractional integration approach. This method implies that, if the integration order is smaller than one, mean reversion occur, namely over time the series moves back to its long-run equilibrium after being hit by an exogenous shock. On the other hand, if the differencing parameter is equal to or higher than 1, mean reversion does not take place and shocks have permanent effects. In addition, we also examine in this paper if this parameter has changed in recent years due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

One limitation of our analysis is that it does not take into account possible nonlinearities, which is an important issue because overlooking breaks might affect the fractional integration results. Note also that our focus is on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and of the Russia-Ukraine war on the degree of persistence of the series of interest; however, the period analysed also includes other major shocks such as the global financial crisis of 2007/08, whose possible impact will be examined in future study. Another limitation of the present study is that the results concern a specific set of countries in Southeastern Europe (Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia) and cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other countries in the same region with different fundamentals.

2. Literature review

There is plenty of evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic had a severe impact on the number of foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays in the SEE countries, which raises the issue of adopting appropriate policy responses. A relevant debate, which predates the crisis, concerns how to develop a sustainable tourism system that might be less vulnerable to such exogenous shocks; for instance, in the case of Martin Brod, a small town in Bosnia and Herzegovina, within a couple of years the locals changed their sustainability imaginaries (“a society’s understanding of how environmental resources should be used”) in response to shifting external financial circumstances (Dogmus & Nielsen, Citation2021). Managers of enterprises in Slovenia essentially depended on labour crisis management practices (CMPs), liquidity, assistance from stakeholders and the government to manage the emergency represented by the COVID-19 shock (Kukanja et al., Citation2022). Bulgaria generally fared better during the pandemic (Hermansen, Citation2021), but there is still a need to find opportunities for extending the season and overcoming the decline of journeys and visits to mountain resorts (Velkova & Dimitrova, Citation2021). Since the beginning of the pandemic, the European Union has also adopted several support measures for the SEE countries with the purpose of alleviating the economic impact of the pandemic (European Commission, Citation2022). The pandemic clearly affected the decision making of tourists; for example, a study on the Porto Metropolitan Area in Portugal by da Silva Lopes et al. (Citation2021) showed that it resulted in shorter and more spatially concentrated visits from a smaller set of countries, which created new challenges and crisis management responsibilities for the relevant authorities. Another important issue highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic is the higher degree of attention that should be given to care homes by local authorities (Manthorpe & Iliffe, Citation2021).

In the light of the issues discussed above, the aim of the present study is to provide evidence on the degree of persistence in the tourist sector of these countries and how it might have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This type of analysis has important policy implications, since policy action is only required in the case of shocks with long-lived effects.

2.1. Data and methodology

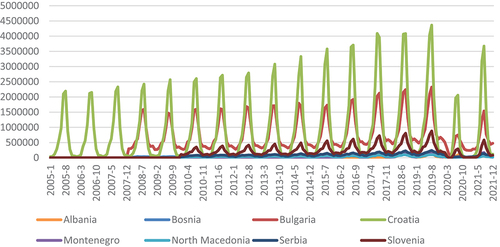

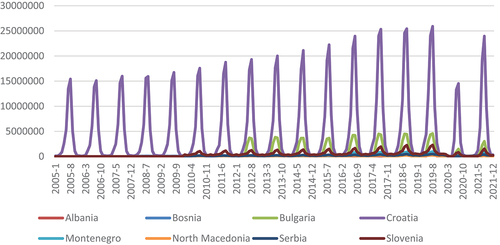

We analyze monthly data on foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays for the longest available span in each of the SEE countries included in our dataset (namely Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia). The data sources are the national statistical offices of the various SEE countries, more precisely: Institute of Statistics Albania, Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria, Croatia Bureau of Statistics, Statistical Office of Montenegro, State Statistical Office Republic of North Macedonia, Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. The sample period for the various countries examined is the following: Albania, 2018M01-2021M12; Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2008M01-2021M12; Bulgaria, 2008M01-2021M12 for foreign arrivals and 2012M01-2021M12 for overnight stays; Croatia, 2005M01-2021M12; Montenegro, 2016M01-2021M09; North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia, 2010M01-2021M12. Foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays are displayed in Figures respectively. Both the negative impact of COVID-19 and seasonality patterns are immediately apparent in both cases.

Tables report descriptive statistics for the two variables in all countries. Croatia has the highest number of observations (204), followed by Bulgaria and Bosnia (168); all countries reached an all-time high for foreign tourist arrivals and foreign overnight stays in August 2019 (all data expressed in thousands): Albania, with 190 arrivals and 640 stays; Bosnia, 166 & 356; Bulgaria, 2325 & 4569; Croatia, 4365 & 25905; Montenegro, 204 & 962; North Macedonia, 100 & 248; Serbia, 237 & 490 and Slovenia, 879 & 2286; by contrast, historically all-time lows for both series were reached in April 2020, with some countries even registering zero foreign arrivals and overnight stays.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for foreign tourist arrivals in SEE countries

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for foreign overnight stays in SEE countries

These series are analyzed using fractional integration methods. This framework is very general since it allows for fractional (as well as integer) degrees of differentiation, and thus it encompasses a much wider range of stochastic processes than the standard approach based on the I(0) versus I(1) dichotomy. It has been shown to outperform classical methods performing stationarity/unit root tests (see, e.g. Diebold & Rudebush, Citation1991; Hassler & Wolters, Citation1994; Lee & Schmidt, Citation1996 and others). To allow for some degree of generality, we include a linear time trend in the model, along with a seasonal AR(1) structure to capture the seasonality of the data. More precisely, the model is specified as follows:

where yt stands for the observed series; α and β are unknown coefficients, namely the intercept (constant) and the linear time trend coefficient; B denotes the backshift operator; xt stands for the regression errors, which are assumed to be integrated of order d or I(d), with ρ being the seasonal coefficient.

Note that the first equality in (1) simply incorporates deterministic terms; the second one includes the fractional integration operator, and can be expanded as follows:

and then xt can be expressed as an infinite AutoRegressive (AR) process, with the differencing parameter d indicating the degree of persistence of the series, where the higher d is, the higher is the degree of dependence between the data. This second equality also admits an infinite Moving Average (MA) representation, such that values of d below 1 indicate that the coefficients decay hyperbolically to zero, which implies a relatively slow mean reversion process. Values of d equal to or higher than 1 lack this property.

Fractional integration was originally described in Granger (Citation1980, Citation1981), Granger and Joyeux (Citation1980) and Hosking (Citation1981). Granger (Citation1980) observed that many aggregated data displayed a periodogram (which is an estimator of the spectral density function) with a very large value around the zero frequency, suggesting that the series should be differenced; however, after first differentiation, the periodogram of the series displayed a value close to zero at such a frequency, which was a clear indication of over-differentiation. This suggests that instead a differencing parameter between 0 and 1 should be used. Nowadays, fractional integration is widely used in the analysis of aggregated time series data (see, e.g., Gil-Alana & Robinson, Citation1997; Haldrup & Vera Valdés, Citation2017; Belbute & Pereira, Citation2017; Ren & Xie, Citation2018; Abbritti et al., Citation2016, Citation2023; etc.). The final equality in (1) takes into account the seasonal structure of the data, which is assumed to be stationary and modelled in terms of a seasonal AR(1) process.

3. Empirical results

Table reports the estimated coefficients from EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) , in Panel (i) for Foreign Tourist Arrivals, and in Panel (ii) for Foreign Tourist Nights. Note that the differencing parameter d (and the 95% confidence intervals, in parenthesis) is estimated using three different specifications: without deterministic components; with a constant only; with a constant and a linear time trend; the reported estimates are those from the specification selected on the basis of the statistical significance of the regressors, which in all cases includes a constant only. The estimates of d imply that in the case of Foreign Tourist Arrivals (panel i) mean reversion takes place only in Bosnia, whilst in the other cases either the unit root null (d = 1) cannot be rejected (as in Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia and Slovenia) or d is found to be significantly higher than 1 (as in Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia). As for Foreign Tourist Nights (panel ii), mean reversion is not found in any single case and the unit root null hypothesis cannot be rejected for any country except North Macedonia and Serbia, in both cases in favor of alternatives with d > 1. Thus, these results suggest that the effects of shocks are transitory only in the case of Bosnian arrivals, whilst they are permanent in all other cases. Finally, there is evidence of seasonality in some of the series, especially in Bulgaria and Croatia, but also in Slovenia and Albania.

Table 3. Estimates based on the original data

Table reports the corresponding estimates for the logged series. The parameter d is now found to be lower than previously, with mean reversion taking place not only for Bosnia (with d = 0.61) but also for Albania (d = 0.47) and Slovenia (0.49); in other countries, despite the estimates of d being below 1 (as in Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia), the unit root hypothesis cannot be rejected. Concerning Foreign Tourist Nights, mean reversion occurs in Albania and Croatia, with estimates of d significantly below 1. On the whole, more evidence of mean reversion is found when using the logged data, in particular for both series in the case of Albania, and also for arrivals in the case of Bosnia and Slovenia and overnight stays in the case of Croatia. Again, Bulgaria and Croatia exhibit the largest seasonal AR coefficients for both series.

Table 4. Estimates based on the logged transformed data

To examine the possible impact of the COVID-19 pandemic we repeat the analysis ending the sample in December 2019. These results are displayed in Tables for the original and the logged series respectively.

Table 5. Estimates based on the original data. Data ending at 2019

Table 6. Estimates based on the logged transformed data. Data ending at 2019

When using the raw data, in the case of arrivals we obtain much lower estimates of d than those based on the full sample, except in the case of Bosnia (Table , panel i), and mean reversion now takes place in Bulgaria and Croatia; as for overnight stays (Table , panel ii), mean reversion is detected in Bosnia, Serbia and Slovenia, whilst in the other cases the confidence intervals are so wide that the unit root null cannot be rejected, and in the case of Albania neither the I(0) nor the I(1) hypothesis can be rejected. Seasonality is clearly present in all cases.

Concerning the logged data (Table ), we find that, for arrivals, mean reversion takes place in all cases except Montenegro, and for overnight stays in all cases except Montenegro and Albania. Further, the time trend is now statistically significant and positive in some cases, especially for overnight stays. Once again, seasonal patterns are present.

On the whole, there is evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased the degree of persistence of the series, the number of cases without mean reversion being much higher in the full sample including the pandemic period; it has also reduced the importance of the seasonal component in the data.

4. Conclusions

This paper has examined the statistical properties of two tourism-related series (the number of foreign tourist arrivals and overnight stays) in a group of eight Southeastern European countries, namely Albania, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia. For this purpose, a fractional integration model has been estimated that allows to distinguish between transitory and permanent effects of shocks within a more general and flexible framework compared to the classical approach based on unit root tests.

The empirical findings suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic increased both persistence and seasonality in the series under investigation. Interestingly, they also point to some cross-country differences, possibly reflecting different policy responses to the pandemic. Regional cooperation might be desirable to achieve a faster recovery in the tourist sector and to reduce the impact of future external shocks.

Our analysis can also be carried out for other countries, in Europe or elsewhere, with different economic fundamentals. In addition, the linear specification used in the paper can be expanded to allow for structural breaks at known or unknown points in time. In fact a non-linear model, still in the context of fractional integration, can alleviate the problem of the abrupt changes produced by the breaks in the data. Future work will address these issues.

Ethics statement

This paper has not received approval from a committee/board of any university or institution.

Acknowledgments

Comments from the Editor and two anonymous reviewers are gratefully acknowledged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbritti, M., Carcel, H., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Moreno, A. (2023). Term premium in a fractionally cointegrated yield curve. Journal of Banking and Finance, 149, 106777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2023.106777

- Abbritti, M., Gil-Alana, L. A., Lovcha, Y., & Moreno, A. (2016). Term structure persistence. Journal of Financial Econometrics, 14(2), 331–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjfinec/nbv003

- Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina. (2022). Business statistics. Tourism. https://bhas.gov.ba/Calendar/Category/19#

- Albaladejo, I. P., Gonzalez-Martinez, M. I., & Martinez-Garcia, M. P. (2020). A double life cycle in tourism arrivals to Spain: Unit root tests with gradual change analysis. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 18, 100497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100497

- Al-Nsour, B. H. (2021). The impacts of COVID-19 on the Jordan tourism & accommodations sector: An empirical study. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 24(4), 1–11.

- Aronica, M., Pizzuto, P., & Sciortino, C. (2022). COVID‐19 and tourism: What can we learn from the past? The World Economy, 45(2), 430–444. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13157

- Bahmani-Oskoee, M., Chang, T., Elmi, Z., & Ranjbar, O. (2021). Testing the degree of persistence of COVID-19 using Fourier quantile unit root test. Economics Bulletin, 41(2), 490–494.

- Belbute, J. M., & Pereira, A. M. (2017). Do global CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel consumption exhibit long memory? a fractional-integration analysis. Applied Economics, 49(40), 4055–4070. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2016.1273508

- Claudio-Quiroga, G., Gil-Alana, L. A., Gil-Lopez, Á., & Babinger, F. (2021). A gender approach to the impact of COVID-19 on tourism employment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(8), 1818–1830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2068021

- Croatia Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Gross value added by activities and gross domestic product, current prices, 1995 - 2020 (ESA 2010). https://dzs.gov.hr/en

- da Silva Lopes, H., Remoaldo, P. C., Ribeiro, V., & Martín-Vide, J. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on tourist risk perceptions—the case study of Porto. Sustainability, 13(11), 6399. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116399

- Diebold, F. X., & Rudebush, G. D. (1991). On the power of Dickey‐Fuller tests against fractional alternatives. Economics Letters, 35(2), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(91)90163-F

- Dogmus, Ö. C., & Nielsen, J. Ø. (2021). Defining sustainability? Insights from a small village in Bosnia and Herzegovina. GeoJournal, 86(5), 2165–2181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-020-10181-9

- European Commission. (2022). Details of Bulgaria’s support measures to help citizens and companies during the significant economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic. https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/coronavirus-response/jobs-and-economy-during-coronavirus-pandemic/state-aid-cases/bulgaria_en

- Gil-Alana, L. A., Gil-Lopez, A., & Roman, E. S. (2019). Tourism persistence in Spain: National versus international visitors. Tourism Economics, 27(4), 614–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816619891349

- Gil-Alana, L. A., & Robinson, P. M. (1997). Testing of unit roots and other nonstationary hypotheses in macroeconomic time series. Journal of Econometrics, 80(2), 241–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(97)00038-9

- Granger, C. W. J. (1980). Long memory relationships and the aggregation of dynamic models. Journal of Econometrics, 14(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(80)90092-5

- Granger, C. W. J. (1981). Some properties of time series data and their use in econometric model specification. Journal of Econometrics, 16(1), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(81)90079-8

- Granger, C. W. J., & Joyeux, R. (1980). An introduction to long-memory time series models and fractional differencing. Journal of Time Series Analysis, 1(1), 15–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9892.1980.tb00297.x

- Haldrup, N., & Vera Valdés, J. E. (2017). Long memory, fractional integration, and cross-sectional aggregation. Journal of Econometrics, 199(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2017.03.001

- Hassler, U., & Wolters, J. (1994). On the power of unit root tests against fractional alternatives. Economics Letters, 45(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(94)90049-3

- Hermansen, M. (2021). Reducing regional disparities for inclusive growth in Bulgaria. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1663. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/d18ba75b-en

- Hosking, J. R. M. (1981). Fractional differencing. Biometrika, 68(1), 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/68.1.165

- Imeri, A., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2022a). The impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Geojournal of Tourism and Geosites, 44(4), 1397–1402. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.44426-958

- Imeri, A., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2022b). Persistence on tourism in North Macedonia: The impact of COVID-19. IFAC-Papersonline, 55(39), 413–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.12.069

- Institute of Statistics Albania. (2022). Structure of GDP by economic activity, type and year. http://www.instat.gov.al/en/about-us/

- Kukanja, M., Planinc, T., & Sikošek, M. (2022). Crisis management practices in tourism SMEs during COVID-19 - an integrated model based on SMEs and managers’ characteristics. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal, 70(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.37741/t.70.1.8

- Lee, D., & Schmidt, P. (1996). On the power of the KPSS test of stationarity against fractionally-integrated alternatives. Journal of Econometrics, 73(1), 285–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(95)01741-0

- Manthorpe, J., & Iliffe, S. (2021). Care homes: Averting market failure in a post-covid-19 world. BMJ, 372, n118. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n118

- Narayan, P. K. (2005). Testing the unit root hypothesis when the alternative is a trend break stationary process: An application to tourist arrivals in Fiji. Tourism Economics, 11(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000005774352971

- National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria. (2022). Tourism. https://www.nsi.bg/en/content/1847/tourism

- Payne, J., Gil-Alana, L. A., & Mervar, A. (2021). Persistence in Croatian tourism: The impact of COVID-19. Tourism Economics, 28(6), 1676–1682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816621999969

- Ren, Y., & Xie, T. (2018). Consumption, aggregate wealth and expected stock returns: A fractional cointegration approach. Quantitative Finance, 18(12), 2101–2112. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697688.2018.1459809

- Sciortino, C., Venturella, L., & De Cantis, S. (2023). Measuring proximity tourism in Spain after the pandemic. An origin-destination matrix approach. Turistica-Italian Journal of Tourism, 32(1), 110–127.

- State Statistical Office Republic of North Macedonia. (2022). Gross domestic product by production approach, by NKD Rev.2, by years (from quarterly calculation of GDP). https://www.stat.gov.mk/Default_en.aspx

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. (2022). Gross value added by NACE Rev. 2. https://www.stat.gov.rs/en-US/

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia. (2022). GDP production structure (output, intermediate consumption and value added by activities, NACE Rev. 2). Slovenia, annually. https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/en/Data/-/0301915S.px

- UNWTO. (2019). International tourism highlights, 2019 edition. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284421152

- Velkova, E., & Dimitrova, S. (2021). Sustainable development model for mountain tourist territories in Bulgaria after the crisis period. Economic Studies, (7), 221–242.

- Yucel, A. G., Koksal, C., Acar, S., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on Turkey’s tourism sector: Fresh evidence from the fractional integration approach. Applied Economics, 54(27), 3074–3087. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2022.2047602