?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study investigates the influence of foreign institutional investment on the risk-return profile of firms. Corporate risk is analyzed as business risk and financial risk in this study. The impact of foreign institutional investor’s (FII) holding on business and financial risk taking behavior is studied on 174 listed non-financial firms in India using panel quantile regression methodology for a span of 20 years which include the pre and post 2008 financial crisis periods as well. Panel fixed effect model was found to be appropriate in this study The impact of FII holding is also studied through the distribution of the risk through panel quantile regression. The impact of FII holding on risk taking behaviour of the firms is studied primarily across high, average and low proportion of corporate risk. Overall FII holding has an inverse relationship with corporate risk taking behavior of firms. The positive impact of FII holding across all types of firms in terms of the risk-return profile indicates that their presence is long term and reduces risk taking behaviour of the corresponding firm. The implications of this study will be significant in regulating FII inflows and outflows to ensure discipline on the part of firm management in improving its risk-return profile.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

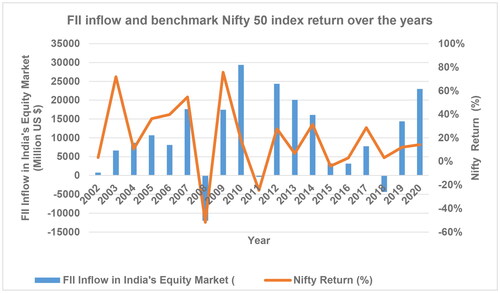

India caught the attention of the global fund managers, especially after 2001, when the world-renowned investment bank Goldman Sachs coined the term BRICS, and clubbed India with four other major emerging market economies namely Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa. Since then, the Indian stock market has become the preferred investment avenue for the foreign institutional investors (FII) as they have become one of the primary movers of the Indian stock market in recent times as evident in .

Figure 1. Nifty 50 index annual return (in %) is plotted against the foreign institutional investment in million US$.

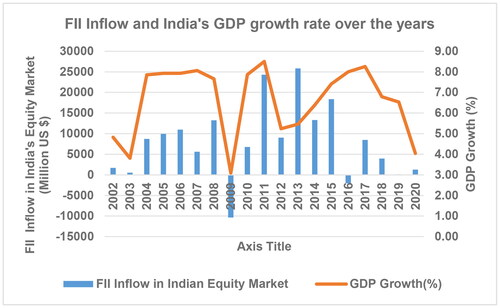

A recent study by Bank of International Settlement (BIS) found that a country’s GDP growth rate is the most important determinant of FII inflows in that country. From this standpoint, it is evident that FIIs are and will be attracted to India, as it is one of the fastest growing economies over the previous two decades and its growth is expected to continue in the coming decade as well ().

Figure 2. India’s real GDP growth rate is plotted against the foreign institutional investment in million US$.

Also, there are motivations on the part of FIIs to move their investments to different parts of the world. According to Grubel (Citation1968), Levy and Sarnat (Citation1970) as well as Solnik (Citation1974), FII inflows in different countries is a natural outcome of these investors urge to diversify their risk and generate higher return on their investment. This line of argument later found support in the works of Grauer and Hakansson (Citation1987), Harvey (Citation1991), and De Santis and Gerard (Citation1997). The bulk of the FII inflows received by fast growing developing countries including India (Garg & Dua, Citation2014) are related to the motivation of FIIs to diversify risk. Calvo et al. (Citation1996) and Taylor and Sarno (Citation1997) states that global factors such as lower interest rate regime and slower growth in developed economies are responsible for such capital inflows to emerging economies. This argument is further supported by studies of Fernaindez-Arias (Citation1996), Kim (Citation2000) as well as Byrne and Fiess (Citation2011). However, another school of thought on FII inflows is related to factors specific to emerging economies. Factors like equity index performance, adequate foreign currency reserve and credit worthiness of the host country facilitate FII inflow into emerging economies (Bohn & Tesar, Citation1996). It is further supported by studies of Mody et al. (Citation2001), Felices and Orskaug (Citation2008), and De Vita and Kyaw.

India has come a long way from early 1990s when India opened its door to foreign capital in its stock markets.Footnote1 A significant portion of FII inflows in India appears to be of long-term nature. The probable reason for the long-term holding of a company’s stake by the FIIs may be to influence the company’s policy matters especially those related to investment as well as financing (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1986). Cronqvist and Fahlenbrach (Citation2009) states that shareholders with large stake can influence firm policy primarily through exercising their voting rights. In addition to these, large shareholders can informally negotiate with incumbent management of the firm on issues related to firm management and governance. Existing literature is also of the view that FIIs tend to compel firms to restructure themselves to be more efficient once they become large enough shareholders (Djankov & Murrell, Citation2002; Estrin et al., Citation2009). This phenomenon is even more profound in the context of emerging economies where foreign investors are considered to have superior know-how to manage a firm. Some scholars argue that FIIs have superior expertise and vast resource pool as they are global firms, that enhances the possibility of their success as portfolio manager (Krishnan, Citation2016). For example, according to International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), (Citation2012), “FIIs are highly specialized and manage substantial capital, can enhance market features in many ways, including increasing liquidity, influencing market psychology, and improving disclosures and corporate governance.” The superior knowledge of FIIs with respect to the domestic investors is also supported by the studies of Froot and Ramadorai (Citation2001). However, the flip side of FIIs led restructuring is expected to increase the volatility of income of the firm and subsequently result in increase in the level of risk.

The bulk of the FII inflows received by fast growing developing countries including India (Garg & Dua, Citation2014) are related to the motivation of FIIs to diversify risk. As a fundamental to long term economic growth, entrepreneurs in pursuit of profitable opportunities take risk John et al. (Citation2008). However, agency literature is titled towards risk avoidance behavior of managers in the process of making corporate investment (Hirshleifer & Thakor, Citation1992). But Faccio et al. (Citation2011) finds statistically and economically meaningful of large shareholders’ diversification and the economic behavior, that is, corporate risk taking. In our study we have taken FII holding as proxy for large shareholder diversification.

The present research article is motivated by the fact that, when FIIs seek superior return, it is of research interest to investigate whether their presence compel the incumbent firm management to pursue riskier projects or not. The risk could be related to investment or financing, or both of the projects undertaken by the management. Thus, the management can be conservative or aggressive in terms of the risk-return profile of the projects undertaken.

Therefore, the study is the first of its kind to investigate the impact of FII investment on the management approach towards business and financial risk-taking in the context of India, which is the third largest (in terms of purchasing power parity) and the fastest growing economy in the world.

Further, because of cross-sectional heteroscedasticity, firms would vary in terms of their risk profile. Therefore, the average impact of FII holding on risk-taking economic behavior as found in the extant literature may not hold for the firms located across the distribution of risk-taking behavior. The two dependent variables CR1 and CR2 in the study are leptokurtic (see descriptive statistics in ). Thus, much of information lies at the tail of the distribution of those variables. Therefore, we have used the novel panel quantile regression approach of Powell (Citation2016), where the impact of FII holding is investigated at each quantile representing a particular level of risk-taking behavior of the management. For example, lower and upper quantile implies high and low level of risk-taking economic behavior of the management respectively.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of variables used in the study.

Lastly, the study also investigates how did the 2008 financial crisis impact the risk-taking behavior of the firms in the presence of FII holding.

We find that the FIIs have higher (lower) proportion of equity holding in firms with lower (higher) corporate risk profile. Moreover, their presence improves the risk-return profile of each category of firms.

2. Literature review

Berle and Means (Citation1932) were the pioneers in exploring the relationship between ownership structure of a firm and its risk-taking behaviour. The study concluded that, in terms of risk-taking behavior, owners favor riskier projects since they derive greater incentives and rewards than the managers. Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) on the other hand discussed how shareholders with substantial stake enjoy cash flow and control benefits from the companies run by them. This set of investors have powerful incentives to collect relevant corporate information as well as monitor managers to maximize their own profits. As the proportion of ownership increases, ceteris paribus, shareholders have greater incentives to raise a firm’s profit by undertaking risky projects.

However, wealth concentration in a single firm may drive large shareholders to a higher degree of risk aversion in comparison to a scenario where the investors had a diversified portfolio of firms. Therefore, John et al. (Citation2008) believed that large shareholders may prefer to undertake more conservative projects to secure firms’ profitability. Boubakri et al. (Citation2013) argued that management’s risk appetite can be influenced directly or indirectly by the foreign investors’ stake. In a more direct way (indirect way) by changing the incentive structure of the management (by changing the firm’s financing/investment decision). Chen et al. (Citation2017) found that FII ownership influences investment efficiency positively in a statistically significant way. In addition to this, Ben-Nasr et al. (Citation2015) argued that foreign ownership also influences earning quality positively.

Djankov and Murrell (Citation2002) and Estrin et al. (Citation2009) were of the opinion that if FIIs take substantial stake in a firm and any restructuring (e.g. after privatization of the erstwhile public-sector firms) activities by FIIs is expected to increase the volatility of the income of the firm and subsequently leading to increase in the level of risk. It is also well documented that big equity stakeholders have the necessary incentive to increase the risk profile of the firm, that too at the expense of interest of debt holders (Cheng et al., Citation2011; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). However, if FIIs own a significant proportion of equity in a firm, they might have incentive to limit the risk appetite of the firm management in order to prevent substantial loss to their portfolio at a given point of time (Cheng et al., Citation2011; Sullivan & Spong, Citation2007).

Many papers noted that the corporate governance is one of the important channels through which FIIs influence the risk-taking capability of firms. Notably, Gillan and Starks (Citation2003) and Ferreira and Matos (Citation2008) observed that FIIs are more often seen to be active than domestic investors in advocating superior firm-level corporate governance standard which in turn acts as one of the determinants of investment policy. Stulz (Citation1999) and John et al. (Citation2008) argue that increased FII ownership in firms lead to improvement in corporate governance standards and hence managerial risk-taking activities.

Leuz et al. argued that FIIs avoid firms with poor corporate governance standards. The reason for this phenomenon is that poor corporate governance standards in firms lead to information asymmetry, which in turn affects the managerial risk-taking (Doidge et al., Citation2009). To add to this John et al. (Citation2008), were of the view that, shareholders of better governed firms have lesser ability to reduce corporate risk taking to pursue their own self-interest. This is also because firms take higher risk if the governance institutions at the country level are of high quality. Because the presence of superior quality governance institutions at the country level influences stronger relationship between FII ownership and appetite of higher risk in the firms in its jurisdiction (Boubakri et al., Citation2013).

Some researchers are of the view that, FII stake induces firms to opt for riskier investment strategy, which in turn lead to higher firm value (Boubakri et al., Citation2013; Denis & McConnell, Citation2003; John et al., Citation2008). This line of argument was further corroborated by Cole et al. (Citation2011), as they stated that owner managers are willing to take higher risk to enhance the shareholder value than the non-owner managers who are more likely to be risk averse.

According to Shoham and Fiegenbaum (Citation2002) a firm’s ability to take risk acts as a determinant of its corporate investment strategy and thus it is a critical component of a firm’s development through innovation as well as competitive advantages. This line of argument was later supported by the works of Li and Liu (Citation2017) as well Cheng et al. (Citation2020). As business environments are uncertain in nature, firms make strategic choices to navigate this environment as well as improve their performance (Hoskisson et al., Citation2017) These choices are corporate actions like merger, acquisition, divesture, spending in research and development etc. and they are an indicator of firm’s risk-taking behavior (Nguyen et al., Citation2020).

Đặng et al. (Citation2022) analyses influence of foreign ownership on non-financial firm risk in the context of Vietnam using panel threshold model. This study found that foreign ownership promotes corporate risk taking up to a certain point. Beyond that threshold point, foreign ownership does not have much influence. Another study exploring the influence of foreign ownership on the corporate risk-taking behavior is done in the context of Vietnam by Vo (Citation2016a, Citationb). He finds that foreign holding results in reduced corporate risk.

In the context of Japan, Kabir et al. (Citation2020) finds that foreign shareholders with short term investment horizon influences firm management to assume higher risk for short term profit maximization.

The extant literature seems inconclusive about the influence of FII holding on the corporate risk-taking behavior, the reason could be the study of average impact ignoring the cross-sectional heteroscedasticity in risk taking attitude of the management. Also, it is noteworthy that one important attribute that is largely unexplored as of now is that, how foreign institutional investment influences corporate risk-taking behavior, especially in the context of an important emerging economy like India. However, it is important to understand this relationship, as corporate risk-taking shapes firm performance as well its growth as one of their key determinants (John et al., Citation2008).

We have hypothesized that the impact of FII holding on the risk-taking behavior of firms will be different across the distribution of their risk-taking behavior. Therefore, our study contributes to the literature in investigating the impact of FII holding on the different level of corporate risk-taking behavior of the management using the novel panel quantile methodology of Powell (Citation2016) in the context of the second largest emerging market economy, that is, India. Further we hypothesize that the 2008 global financial crisis also impacts the relationship between the risk-taking behavior of the firms and FII holding.

We found that the impact of FII holding on risk-taking behavior of firms is different across different levels of corporate risk. We found similar results through robustness check by introduction of additional control variables as well as considering industry effect.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Variables and econometric models

We follow the framework proposed by Faccio et al. (Citation2011) to measure the risk-taking behavior of firms. According to this framework, the ratio of a firm’s profitability to volatility of profitability depicts risk taking behaviour of a firm. The measure is quite comprehensive in nature because it depicts the decisions taken by incumbent management related to the firm’s operations. In this paper, profitability of the firm is depicted in two forms: (1) return on assets (ROA), and (2) return on equity (ROE). In accordance with John et al. (Citation2008), Faccio et al. (Citation2011) and Vo (Citation2016a, Citationb) the standard deviations of ROA and ROE measure the volatility of these two profitability variables and are considered as measure of corporate risk.

The two measures of corporate risk return profile are defined as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

CR1it depicts risk arising out of inefficient utilization of asset of a firm i, at the end of financial year t with respect to market m and indicates business risk. Similarly, CR2it depicts risk arising out of inefficient deployment of equity capital of firm i at the end of financial year t with respect to market m and indicates financial risk.

In both the cases, a positive increase in value indicates either the firm earning more returns as compared to the market or having less volatility with respect to the market or both (and vice-versa). The higher value of CR1 and CR2 thus indicate lower risk and better utilization of firm’s resources and vice versa.

The relationship between FII ownership and risk-taking behaviour of corporate entities is defined as:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Here, FIIit is the foreign institutional ownership of the firm i at the end of the financial year t. Sizeit and Leverageit of the firm are taken as the control variables for this study. FII refers to proportional holding of FIIs- it is calculated as total number of shares held by FIIs divided by total number of shares outstanding.

Size denotes the firm size calculated as natural logarithm of its total asset. Firm size needs to have an inverse relationship with the above corporate risk measures such as CR1 and CR2. There are a couple of intuitive reasons for this line of thinking. Firstly, larger firms have greater capacity to act as the price setter in the market, and due to their larger market share they can maintain that price and subsequently they can maintain stable profitability. Secondly, larger firms generally have better risk management and corporate governance practices (Boubakri et al., Citation2013; Vo, Citation2016a, Citationb). Similarly, Leverage indicates the financial leverage of a firm calculated as the ratio of total liabilities to total asset. Since, leverage acts as one of the primary determinant of earnings’ volatility, financial risk profile of a firm, to a great extent, depends on its financial leverage (Boubakri et al., Citation2013; Vo, Citation2016a, Citationb).

Global economy faced unprecedented crisis in 2007–2008. In our analysis, to assess whether the level of risk taking (i.e. CR1 & CR2) across firms is different in the pre-crisis and the post-crisis periods, median test is conducted. Further, we investigate whether there is a change in corporate risk behavior of firms with respect to holding pattern of FIIs between the pre- and post-crisis periods.

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

Here, the fifth term Crisis takes the value 0 for the years 2001–2007 denoting pre-crisis regime and takes the value 1 for the years 2010–2020 depicting post-crisis regime. The sixth term that is, Crisis × FIIit is an interacting dummy variable created to capture the joint effect of crisis periods (pre & post) and foreign institutional ownership of firms. While the coefficient of the second term β1 represents partial impact of FII on Corporate Risk in the pre-crisis period, the combined value of β1 + β5 represents impact of FII on Corporate Risk in the post-crisis period. Thus, the coefficient of fifth term β5 represents the differential impact of FII on Corporate Risk due to change in crisis periods.

Finally, since FII holding pattern has both spatial and temporal variations due to inclusion of firms from various industry categories in the sample as well as the span of the sample respectively, we investigate the relationship between FII holdings and corporate risk behaviour using non-additive fixed-effect by Powell (Citation2016). Here, we assume that the effect of FII holdings on risk taking behavior of firms could be conditional on the distribution of the risk levels, and could be sensitive to values recorded at the extremes of the distribution. Also, we find that there is a lack of emphasis in literature on the potential role of FII holdings on various levels of corporate risk borne by firms. It involves a set of regression curves that differ across various quantiles of the conditional distribution of the dependent variable, that is, CR1 and CR2.

The model specification are as follows:

(7)

(7)

For the τth quantile of Yit, the conditional restriction of the quantile regression can be represented as:

(8)

(8)

where, Yit is the Corporate Risk (CR1 & CR2) of firm i in the year t; βj are the parameters of interest; Xit is the set of explanatory variables: FII holdings, Size and Leverage of firm i for the year t;

represents the error term that may be a function of fixed and time-varying disturbance terms. In EquationEq. (7)

(7)

(7) , we relax the symmetry assumption by allowing the coefficients to vary across quantiles in order to capture the conditional impact of FII holdings on the distribution of Corporate Risk for a range of τ, 10th through 90th quantile. The model is linear in parameters and

is monotonically increasing in τ. EquationEquation (8)

(8)

(8) states that the probability of the outcome variable does not exceed the quantile function and is same for all Xit which is equal to τ. The model and estimators in the above framework control for endogeneity issues and the fixed effects are allowed to have an arbitrary relationship with the instruments. The above model is estimated using the Markov-Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) optimization method with 10,000 replications. The impact of FII holding on risk taking behaviour of the firms is studied primarily across three different 10th, 50th and 90th quantiles correspond to high, average and low risk-taking firms respectively. Thus, the impact of FII holding is conditional on the level of risk-taking attitude of the management of the firm.

3.2. Data and sample

Annual data of all the non-financial companies listed in Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) database’s COSPI index are taken as sample for 20 years from 2001 to 2020. The companies with less than 20% FII holding, cumulative over the 20 years’ period, are removed from the sample. After accounting for missing data, we arrive at 174 firms * 20 years = 3480 firm-year observations, which make it a balanced panel dataset. Since the non-financial firms are different from financial firms in terms of nature of business and practices of accounting reporting (Zhu et al., Citation2015), we study only the non-financial firms. Vo (Citation2016a, Citationb) as well as Kabir et al. (Citation2020) considers only non-financial firms in their study.

4. Empirical findings and discussion

4.1. Summary statistics

provides summary statistics of the variables. It is observed that, the mean value of CR1 and CR2 remains near zero for pre, post, and overall periods. As such the median statistic becomes relevant for deduction. The median value of CR1 is negative for all the periods, indicating that the centrally located firms suffer from risk arising out of under-utilization of asset, as compared to market as a whole. The median value of CR2 remains largely positive barring post crisis period, indicating that, in the post crisis period, the centrally located firms tend to become risk averse as their equity base increased.

With respect to the explanatory variables, it is observed that, as compared to pre-crisis, in the post crisis period, the average FII holdings and Size of firm has increased, while the average Leverage of firms have declined indicating increase in equity base. In the post-crisis period, increase in FII holdings and Size indicate that the overall perception of risk in Indian firms have declined and the asset base of the firms have increased respectively.

All except CR1 are positively skewed (median < mean) throughout all the periods, indicating the presence of outliers. All variables show high kurtosis which indicate that much of the information lies at the tail justifying our study at the quantile level. Further, the justification is corroborated by the minimum and maximum value of CR1 and CR2 which indicate that the firms are heteroscedastic in terms of risk return profile. The variance inflation factor (VIF) statistic indicate absence of multicollinearity in the explanatory variables. Levin Lin and Chu unit root test shows that all the variables are stationary and are taken for further analysis. As the Durbin-Wu-Hausman (DWH) test does not reject the null hypothesis (H0: All predictor variables are exogenous), instrumental variable method is not carried out as an alternative analysis.

We have applied the Mood’s Median test with null hypothesis of equal value of median CR1 and CR2 in both pre and post crisis period. The rejection of null hypothesis justifies our study of the impact of FII holding in pre and post crisis period ().

Table 2. Result of Mood’s Median test.

The above result show that in case of CR1, the business risk lessened significantly, indicating improvement in asset utilization in the post crisis period. However, in case of CR2, the financial risk has increased significantly in the post crisis period, indicating less efficient deployment of equity capital. In post crisis period. FIIs became much more prudent with respect to their investments, as a result they influenced the firm managements to increase asset utilization in their respective firms, which led to reduction in risk with respect to CR1. It should be noted that in the post crisis period, the firms became conservative and reduced their leverage by increasing their equity capital. Due to this phenomenon the risk with respect to CR2 is increased in the post crisis period.

shows the correlation between all the variables considered in this study. The table reveals some interesting findings, for example, the correlation coefficient between the two risk variables is high and significant.

Table 3. Correlation matrix.

Next, we can notice that FII ownership has positive and significant relationship with both the risk measures. These clearly indicates that the FIIs prefers companies with lesser risk. This unconditional measure of relationship may not reflect cross sectional heterogeneity. Therefore, we have used the novel panel quintile methodology of Powell (Citation2016) to uncover the association of FII holding across higher to lower risk-taking firms. The positive correlation between FII and size of the firm and negative correlation with leverage of the firm are consistence with the observations by Batten and Vo (Citation2015) and Vo (Citation2016a, Citationb). These results indicate that institutional investors prefer to invest in firms with larger size and lower leverage.

4.2. Panel fixed effect analysis

In this section, we have presented the average impact of FII holding on CR1 and CR2 based on panel fixed effect modelFootnote2 as a reference for comparision with panel quantile results ().

Table 4. Result of panel fixed effect model.

It is observed that FII is positively associated with both CR1 and CR2, although the magnitude of the impact is more in case of CR1. That means, increase in FII holding will lower the business risk more than the financial risk implying thereby the greater and better utilization of asset. This is in accordance to the existing literature, as FIIs will act as the watchdog on the management, and firms with higher FII stake are considered to be better managed and attracts other investors (Mohanamani & Sivagnanasithi, Citation2012).

As far as CR2 is concerned, financial risk decreases with the increase in FII stake. This phenomenon implies greater pressure on the incumbent management to improve the return on equity. As FIIs are considered to be much more influential than other set of investors, they are in a much better position to influence the decisions of the management team. The stake held by FIIs often act as the cue for other investors to follow suit.

Size and leverage have negative impact on CR1 and CR2. This indicates larger firms as well as firms with more leverage take more risk, the probable reason for this phenomena are these firms have the necessary financial wherewithal to take more risk (due to larger size). Also firms with higher leverage have access to more debt, as debt capital has comparatively lower cost than equity, these firms can indulge in more risk.

4.3. Impact of financial crisis

shows the impact of FII on CR1 and CR2 due to financial crisis. In case of both CR1 and CR2, the interactive crisis dummy variable coefficient is not significant for both CR1 and CR2. Thus, it is clear that there is no effect of FII holding in risk taking behaviour of firms, either in terms of CR1 and CR2 in the post crisis period.

Table 5. Results of panel fixed-effect model with crisis dummy variable using EquationEqs. (5)(5)

(5) and Equation(6)

(6)

(6) .

As earlier, the control variables Size and Leverage are found to be negative and statistically significant in both the cases of corporate risk-taking measures. However, the average impact cannot be generalized across the heterogeneous firms having different levels of business and financial risk. This justifies our study of the impact of FII holding across the quantiles of CR1 and CR2 using the novel panel quantile methodology of Powell (Citation2016). The lower, that is, 10th and higher, that is, 90th quantile indicate high and low risk-taking firms respectively.

4.4. Results of panel quantile analysis

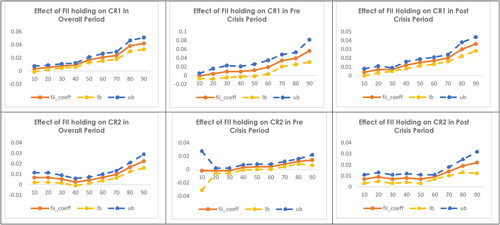

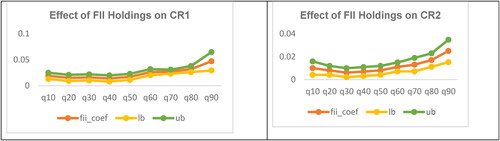

The results of the impact of FII holding on corporate risk-taking attitude across nine quantiles starting from 10th through 90th are presented in . This provides a complete picture of the impact of FII holding across the distribution of CR1 and CR2. Along with the overall results covering the entire period, the results are presented for pre and post crisis period.

Table 6. Panel quantile analysis of the impact FII on CR1 and CR2 after controlling for size and leverage.

4.4.1. High proportion of corporate risk (the 10th quantile)

In pre-crisis period, no significant impact of the FII holding on CR1 and CR2 is observed. However, the impact is positive and significant in the post crisis period. That means post financial crisis, FII investment has brought changes in business and financial risk of the high-risk category of firms. Overall, the impact of FII holding is not statistically significant for CR1, whereas it is statistically significant for CR2 which means financial crisis overshadows the true impact of FII holding on the business risk attitude of the firms.

4.4.2. Average proportion of corporate risk (the 50th quantile)

Overall, the impact of FII holding on average category of firms in terms of CR1 and CR2 is statistically significant which corresponds to the average impact estimated using panel fixed effect model. However, in the pre-crisis period, the impact of FII holding is (not) statistically significant for CR2 (CR1). But, in post crisis period, the impact of FII holding is statistically significant for both CR1 and CR2.

4.4.3. Low proportion of corporate risk (the 90th quantile)

In case of 90th quantile which represent the lower risk category of firms in terms of business and financial risk, the positive and significant impact FII holding is observed across pre and post-crisis and for the entire period as well. However, in comparison to pre-crisis, in post crisis period, the impact is more on CR2. That means it is confirmation of the fact FII prefers low business and financial risk firms and tries to improve the operational and financial efficiency of that firm. The graphical presentation of the impact FII holding on CR1 and CR2 across quantiles for pre, post and entire period are presented through .

The upward sloping curve across pre, post and the entire period implies the fact that impact of FII holding increases moving from lower to higher business and financial risk category of firms.

4.5. Robustness analysis of the resultsFootnote3

To test the robustness of the results, additional control variables are introduced in EquationEqs. (5)(5)

(5) and Equation(6)

(6)

(6) . According Shazad et al. lifecycle of a firm influences Corporate Risk. Subsequently Firm Age (based on year of incorporation) is taken as an additional control variable. Public Shareholding (i.e. Non Promoter Shareholding in the context of India) is introduced as a control variable. According to Raheja more promoter shareholding in a firm makes shareholders interest aligned with that of the interest of the management, as proportion of public shareholding indicates extent of agency conflict, it is interesting to test its effect on Corporate Risk. Firm Liquidity (in terms of Current Ratio) are introduced as a control variable as firms with more liquidity may take more risk.

Based on National Industrial Classification (NIC) Code the 174 companies are divided into various groups, these groups are further clustered into broader categories based on base NIC Code. The top three broad industry categories are taken into account to check the industry effect, these three categories are (i) Construction (27 firms), (ii) Oil, Chemical and Polymer (49 firms) (iii) Services (22 firms). In total 98 firms having 1960 firm year observations are part of the industry effect study. These 98 firms represent 56.32% of the total firms that are taken into account in this study.

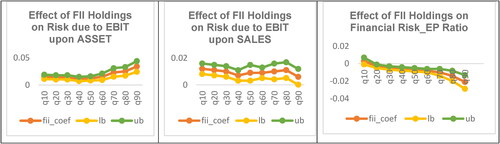

The results of the impact of FII holding on corporate risk-taking attitude across nine quantiles starting from 10th through 90th considering three additional control variables, that is, Liquidity (in terms of Current Ratio), firm age and public shareholding and industry dummy are presented through .

Table 7. Panel quantile analysis of the impact FII on CR1 and CR2 after controlling for industry effect, liquidity, firm age, public holding, size and leverage.

As evident from , the impact of FII holding on CR1 and CR2 is significant and positive at 10th, 50th and 90th quantile. Thus, it shows that the panel quantile regression results are robust even after considering three more additional variable such as liquidity, firm age and public shareholding along with industry effect ().

Figure 4. Impact of FII holding across the quantiles of CR1 and CR2 after controlling for size, liquidity, age, leverage, public shareholding and industry effect.

Similarly, the model is tested with alternative risk measures like business risk depicted by EBIT (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) divided by Total Asset as well as EBIT divided by Sales and a risk measure is created in line with CR1 (which is based on ROA). The rationale behind taking EBIT into account is that EBIT numbers are not affected by the proportion of Debt in the capital structure of the Firm. Similarly, a Risk measure is created with Earning at Risk*; creation of this variable is in accordance with Edmonds et al. (Citation2015). Earning at Risk is the Earning Volatility measure that is created as the standard deviation of earnings before extraordinary items scaled by the market value of equity (EP Ratio).

The results of the panel quantile regression are depicted below with these additional risk measures, for the purpose of robustness check ().

Table 8. Panel quantile analysis of the impact FII on EBIT_Sales and EBIT_Asset as a proxy for business risk and EPRatio as proxy for financial risk after controlling for industry effect, liquidity, firm age, public holding, size and leverage.

As shows, business risk with respect to EBIT/Asset has the same kind of relationship as CR1 with FII across the quantiles. However FII does not have a consistent relationship with business risk with respect to EBIT/Sales. Relationship of FII with earning at risk (EP Ratio) is in contrary to its relationship with either CR1 or CR2 as well.

5. Conclusion

This particular study was done to explore, whether FII holding in non-financial firms influence their risk-taking behavior. We have used panel quantile regression analysis to investigate the impact by segregating firms in terms of its risk-return profile as high, average and low. Our study is quite comprehensive in the context of a major emerging market economy, i.e. India in dividing the study period as pre and post 2008 financial crisis. At the overall level, FII holding has an inverse relationship with the risk taking behavior of firms. Impact of FII holding is found to be more pronounced in post-crisis period. Moreover, the impact is more visible in lower risk and higher return category of firms. The positive impact of FII holding across all types of firms in terms of the risk-return profile indicates that their presence is long term and reduces risk taking behaviour of the corresponding firm. These findings are a significant addition to the existing literature. As most of the existing studies on this topic are done in the context of developed market economies, this study is especially important in the context of a major emerging market economy. The findings of this study is in line with Vo (Citation2016a, Citationb) in an emerging market context. The probable reason for this phenomena is foreign investor’s presence results in broadening of the investor base of a firm, consequently it can create a risk-sharing effect this is in accordance to Merton’s model.

The implications of this study will be significant in regulating FII inflows and outflows to ensure discipline on the part of firm management. Further research could be undertaken related to the association between FII inflows and valuation considering the heteroscedastic of the firms.

As the study shows higher FII stake leads to lower risk taking by the firms, encouraging more inflow of FIIs should help in disciplining the firm management through market mechanism. This should be helpful, especially in the context of many emerging economies, where regulator’s capability to discipline firm management is limited and corporate governance standards are lax. In this context FII stake will act as the motivating factor for the firm management to be disciplined.

Consent to participate

The authors give their consent to participate.

Consent for publication

The authors give their consent to participate.

Souvik Banerjee_Profile.docx

Download MS Word (11.8 KB)Cover Ltter.docx

Download MS Word (11.7 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Souvik Banerjee

Dr. Souvik Banerjee has keen interest in research and has presented research papers in many prestigious national and international conferences including prestigious conferences like First Corporate Governance Conference organized by IIM, Trichy, Yale Great Lakes Conference organized by Great Lakes Institute of Management, Chennai in collaboration with Yale University, the USA, etc. He had chaired a Technical Session in an international conference at IIM, Kozhikode. Some of the research papers are published in Scopus and ABDC Indexed journals. He has published many research papers in referred journals, in India, the UK, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines. Dr. Banerjee has developed many case studies for class room discussion as well as executive education. He was previously associated with IBS Hyderabad as a faculty member.

Notes

1 As per Bloomberg, as of March 2022, India ranked 5th in the entire world in terms of total market capitalization of all the listed entities. The total market capitalization of India stood at $3.2 trillion. India is the second largest emerging market in the list, following China.

2 Based on Hausman test, Panel Fixed Effect appears to be the appropriate model for the data set. Results are available upon request. Hence, Panel Fixed Effect model has been subsequently used to model the effect of Crisis period (EquationEqs. 5(5)

(5) , Equation6

(6)

(6) ) and in Panel Quantile Regression (EquationEq. 7

(7)

(7) ).

3 We are thankful to the anonymous referees for suggesting this section.

References

- Batten, J. A., & Vo, X. V. (2015). Foreign ownership in emerging stock markets. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 32-33, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2015.05.001

- Ben-Nasr, H., Boubakri, N., & Cosset, J. C. (2015). Earnings quality in privatized firms: The role of state and foreign owners. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 34(4), 392–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2014.12.003

- Berle, A., & Means, G. G. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. Macmillan.

- Bohn, H., & Tesar, L. L. (1996). US equity investment in foreign markets Portfolio rebalancing or return chasing? The American Economic Review, 86(2), 77–81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2118100

- Boubakri, N., Cosset, J. C., & Saffar, W. (2013). The role of state and foreign owners in corporate risk-taking Evidence from privatization. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(3), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.12.007

- Byrne, J. P., & Fiess, N. (2011). International capital flows to emerging and developing countries: National and global determinants. Working papers 2011_01 Business School – Economics, University of Glasgow. https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_184650_smxx.pdf

- Calvo, G. A., Leiderman, L., & Reinhart, C. M. (1996). Inflows of capital to developing countries in the 1990s. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(2), 123–139. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.10.2.123

- Chen, R., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Wang, H. (2017). Do state and foreign ownership affect investment efficiency? Evidence from privatizations. Journal of Corporate Finance, 42, 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.09.001

- Cheng, J., Elyasiani, E., & Jia, J. (2011). Institutional ownership stability and risk taking: Evidence from the life–health insurance industry. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 78(3), 609–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6975.2011.01427.x

- Cheng, T. Y., Lee, C. I., & Lin, C. H. (2020). The effect of risk-taking behavior on profitability: Evidence from futures market. Economic Modelling, 86, 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.04.017

- Cole, C. R., He, E., McCullough, K. A., & Sommer, D. W. (2011). Separation of ownership and management: Implications for risk-taking behaviour. Risk Management and Insurance Review, 14(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6296.2010.01192.x

- Cronqvist, H., & Fahlenbrach, R. (2009). Large shareholders and corporate policies. Review of Financial Studies, 22(10), 3941–3976. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn093

- Đặng, R., Le, N. T., Reddy, K., & Vu, M. C. (2022). Foreign ownership and corporate risk-taking: Panel threshold evidence from a transactional economy. Finance Research Letters, 45, 102190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102190

- De Santis, G., & Gerard, B. (1997). International asset pricing and portfolio diversification with time-varying risk. The Journal of Finance, 52(5), 1881–1912. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb02745.x

- Denis, D. K., & McConnell, J. J. (2003). International corporate governance. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 38(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/4126762

- Djankov, S., & Murrell, P. (2002). Enterprise restructuring in transition a quantitative survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(3), 739–792. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102760273788

- Doidge, C., Karolyi, G. A., Lins, K. V., Miller, D. P., & Stulz, R. M. (2009). Private benefits of control ownership and the cross-listing decision. The Journal of Finance, 64(1), 425–466. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2008.01438.x

- Edmonds, C. T., Edmonds, J. E., Leece, R. D., & Vermeer, T. E. (2015). Do risk management activities impact earnings volatility? Research in Accounting Regulation, 27(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.racreg.2015.03.008

- Estrin, S., Hanousek, J., Kočenda, E., & Svejnar, J. (2009). The effects of privatization and ownership in transition economies. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(3), 699–728. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.3.699

- Faccio, M., Marchica, M. T., & Mura, R. (2011). Large shareholder diversification and corporate risk-taking. Review of Financial Studies, 24(11), 3601–3641. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhr065

- Felices, G., & Orskaug, B. (2008). Estimating the determinants of capital flows to emerging market economies: A maximum likelihood disequilibrium approach. Working paper no. 354, Bank of England. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1319274

- Fernaindez-Arias, E. (1996). The new wave of private capital inflows push or pull? Journal of Development Economics, 48(2), 389–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3878(95)00041-0

- Ferreira, M. A., & Matos, P. (2008). The colors of investors’ money: The role of institutional investors around the world. Journal of Financial Economics, 88(3), 499–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.07.003

- Froot, K. A., & Ramadorai, T. (2001). The information content of international portfolio flows. NEBR Working Paper No, 8472 https://doi.org/10.3386/w8472

- Garg, R., & Dua, P. (2014). Foreign portfolio investment flows to India: Determinants and analysis. World Development, 59, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.01.030

- Gillan, S., & Starks, L. T. (2003). Corporate governance corporate ownership and the role of institutional investors: A global perspective. Working Paper No. 2003-01 Weinberg Center for Corporate Governance, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.439500

- Grauer, R. R., & Hakansson, N. H. (1987). Gains from international diversification 1968–1985: Returns on portfolios of stocks and bonds. The Journal of Finance, 42(3), 721–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1987.tb04581.x

- Grubel, H. G. (1968). Internationally diversified portfolios: Welfare gains and capital flows. The American Economic Review, 58(5), 1299–1314. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1814029

- Harvey, C. R. (1991). The world price of covariance risk. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 111–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb03747.x

- Hirshleifer, D., & Thakor, A. V. (1992). Managerial conservatism, project choice, and debt. Review of Financial Studies, 5(3), 437–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/5.3.437

- Hoskisson, R. E., Chirico, F., Zyung, J., & Gambeta, E. (2017). Managerial risk taking: A multitheoretical review and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 43(1), 137–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316671583

- International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO). (2012). Report of the Emerging Markets Committee on Development and Regulation of Institutional Investors in Emerging Markets. https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD384.pdf

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm Managerial behavior agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- John, K., Litov, L., & Yeung, B. (2008). Corporate governance and risk-taking. The Journal of Finance, 63(4), 1679–1728. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2008.01372.x

- Kabir, M. N., Miah, M. D., Ali, S., & Sharma, P. (2020). Institutional and foreign ownership vis-à-vis default risk: Evidence from Japanese firms. International Review of Economics & Finance, 69, 469–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2020.05.020

- Kim, Y. (2000). Causes of capital flows in developing countries. Journal of International Money and Finance, 19(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5606(00)00001-2

- Krishnan, M. (2016). Foreign institutional investor trading and future returns: Evidence from an emerging economy. https://www1.nseindia.com/research/content/1415_BS5.pdf.

- Levy, H., & Sarnat, M. (1970). International diversification of investment portfolios. The American Economic Review, 60(4), 668–675. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1818410

- Li, J., & Liu, X. (2017). Trust beneficiary protection, ownership structure, and risk taking of trust corporations: Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 53(6), 1318–1336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2017.1284658

- Mody, A., Taylor, M. P., & Kim, J. Y. (2001). Modeling economic fundamentals for forecasting capital flows to emerging markets. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 6(3), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.159

- Mohanamani, P., & Sivagnanasithi, T. (2012). Impact of foreign institutional investors on the Indian capital market. Journal of Contemporary Research in Management, 7(2), 1–9.

- Nguyen, T. T. H., Moslehpour, M., Vo, T. T. V., & Wong, W. K. (2020). State ownership and risk-taking behavior: An empirical approach to get better profitability, investment, and trading strategies for listed corporates in Vietnam. Economies, 8(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8020046

- Powell, D. (2016). Quantile regression with nonadditive fixed effects. Quantile Treatment Effects, 1(28), 1–33.

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1986). Large shareholders and corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 94(3, Part 1), 461–488. https://doi.org/10.1086/261385

- Shoham, A., & Fiegenbaum, A. (2002). Competitive determinants of organizational risk‐taking attitude: The role of strategic reference points. Management Decision, 40(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740210422802

- Solnik, B. H. (1974). Why not diversify internationally rather than domestically? Financial Analysts Journal, 30(4), 48–54. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v30.n4.48

- Stulz, R. M. (1999). Globalization corporate finance and the cost of capital. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 12(3), 8–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6622.1999.tb00027.x

- Sullivan, R. J., & Spong, K. R. (2007). Manager wealth concentration ownership structure and risk in commercial banks. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 16(2), 229–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2006.12.001

- Taylor, M. P., & Sarno, L. (1997). Capital flows to developing countries long- and short-term determinants. The World Bank Economic Review, 11(3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/11.3.451

- Vo, X. V. (2016a). Foreign investors and corporate risk taking behavior in an emerging market. Finance Research Letters, 18, 273–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2016.04.027

- Vo, X. V. (2016b). Foreign ownership and stock market liquidity-evidence from Vietnam. Afro-Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1504/AAJFA.2016.074540

- Zhu, T., Lu, M., Shan, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2015). Accrual-based and real activity earnings management at the back door: Evidence from Chinese reverse mergers. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 35, 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2015.01.008