?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

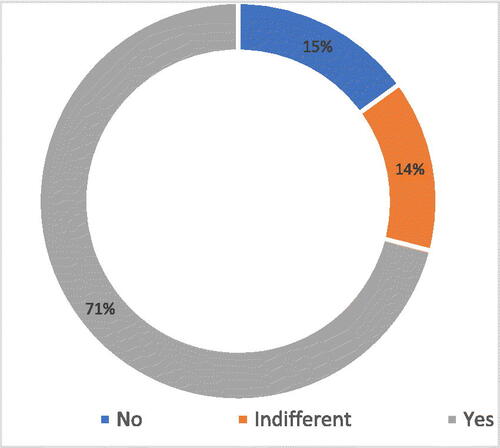

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, several countries resorted to various levels of lockdown as a panacea for the rampant spread of the virus. However, the imposed lockdown was not without economic challenges, particularly for the poor in developing countries. In response, the government of Ghana unveiled several free social support packages such as free water and electricity services. This study models the behaviour for or against free utility services and further investigates the drivers that explain an individual’s behaviour. Using a survey method and an ordered probit econometric technique, we find evidence that about 71 percent of respondents support free utility services, 14 percent are indifferent, and 15 percent also indicate their disapproval. Furthermore, an ordered probit regression analysis is used to show evidence that educated respondents with higher incomes are less likely to appreciate government-sponsored freebies. Other drivers of such behavioural differences for aggregated and disaggregated free social intervention utility services were further examined.

Impact statement

This study examined the reception of free water and a 50 percent electricity discount provided by the Ghanaian government during the COVID-19 pandemic. Utilising survey data and employing an ordered probit method, the research aimed to understand the factors influencing support or opposition towards free utility services. The findings reveal that approximately 71 percent of respondents preferred free utilities, while around 29 percent did not support the Ghana Residential Utility Stimulus implemented by the government. Among those opposed to the residential utility stimulus, a significant proportion were found to be educated individuals with higher incomes, as indicated by the ordered probit regression results. It is suggested that during emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic, social assistance should be directed towards the impoverished and vulnerable segments of society.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

In late 2019, the novel coronavirus, identified in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, underscored many changes in human lives, and its impact continues to be felt. The restriction of human movement, while reducing the health risk of the virus, also exposes the world to economic risks. For many businesses, this has led to revenue losses; for individuals and households, this has resulted in the loss of jobs and a reduction in income or total loss of income. Empirically, every 10 more days that a state in the United States experienced a mandatory stay-at-home, the employment rate fell by 1.7 percent (Gupta et al., Citation2020). Governments worldwide worked tirelessly to reduce the impact of the virus on their citizens, as many economic stimulus packages were announced. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) provided an economic overview of the country-by-country monetary, macro, and fiscal responses to COVID-19. Besides government support, corporate bodies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and well-to-do individuals have also provided support to the poor during the pandemic. Although all these initiatives are laudable, to avoid depriving beneficiaries of the utmost benefit, Barker and Russell (Citation2020) recommend that a good understanding of the sudden changes in food support to recipients during the pandemic is important, to the extent that it needs a coordinated relationship between the government and the voluntary giving sector. This is necessary because food aid programmes in an emergency, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, must not shortchange beneficiaries of dietary needs. According to Chen et al. (Citation2022), corporate philanthropic support in situations like COVID-19 largely depends on controllable organisational factors, such as pre-existing resource availability and motives to acquire political and reputational resources. On COVID-19 emergency and welfare, fundraising, management, and usage, Desai and Randeria (Citation2020) used evidence from India to recommend that fund mobilisation should be secondary to the design, decision-making, and accountability structure if fiscal resources are not to be wasted.

This study differs from Arndt et al. (Citation2020), who investigated COVID-19 lockdowns, income distribution, and food security in South Africa, in which the authors posit that labour with low education is vulnerable and suffers more in income reduction when the government embarks on movement restrictions compared to labour with secondary or tertiary education, but for insulated government transfer payments. Adams-Prassl et al. (Citation2020) provide similar evidence about income losses for people with low education on the job market in the US and UK. Government economic intervention during this health crisis in the form of relief and its aftermath with recovery packages is therefore critical to prevent social unrest from economic hardship due to government COVID-19 management policies. Webb (Citation2021) holds the view that the cash offered and support by the government during the COVID-19 pandemic has created the need to rethink and relook at cash transfers and the political opportunistic behaviour that may accrue to the government in the name of offering social protection during difficult times. According to Amankwaa and Ampratwum (Citation2020), the poor are more likely to be exploited by service providers for free water support under the government’s COVID-19 pandemic social intervention. Therefore, the government should adopt a more targeted approach. Furthermore, Nkrumah et al. (Citation2021) argue that subsidies for water and electricity promote the welfare of all households, especially those living in rural areas. They further revealed that the poor do not benefit much, irrespective of their location, from a household utility subsidy programme by the state. This paper focuses on Ghana’s support of free water and free electricity interventions at the micro level during the COVID-19 pandemic. While government intervention is expected in such difficult times, the reception of individuals and households is critical for directing future government welfare support in the face of scarce fiscal resources.

We provide evidence to show that about 71 percent of respondents support free utility services, 14 percent are indifferent, and 15 percent also indicate their disapproval. Furthermore, our results show that educated respondents with higher income are less likely to appreciate such freebies. A similar disposition is displayed by the unmarried, those who depleted their savings, those who received support, the poor, respondents with public knowledge about COVID-19, and those who are educated but poor, who are more likely to appreciate free utility services.

What makes the present study unique and different from Nkrumah et al. (Citation2021) is that we use responses collected during the pandemic to obtain real-time data. In particular, this study relied on data collected immediately after the lockdown to assess beneficiaries’ appreciation of government social support emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we seek to analyse the socio-economic factors that drive beneficiaries’ preferences for the free water or free electricity policy of the government during the pandemic. This study contributes to the empirical literature on COVID-19 by analysing how the socioeconomic characteristics of individuals and households respond to government residential utility stimuli.

Ghana recorded its first positive case of COVID-19 on March 11, 2020. With 141 confirmed positive cases and five deaths in less than three weeks after the first confirmed positive case, the president declared a partial lockdown. During the 3-week partial lockdown, the government announced a Ghc 1 billion stimulus package for households and small businesses. During this period, the government provided hot meals to the vulnerable in the lockdown cities of Greater Accra, Kosoa, Greater Kumasi, and Tema. Furthermore, the government provided free water from April to December 2020, and a 50 percent electricity subsidy from April to June 2020 for all residential users. There was a further three-month extension of free electricity and water for lifeline electricity consumers and households whose water usage did not exceed five cubic metres per month. Overall, approximately 10,125,620 individuals benefited from free water, while over one million lifeline electricity customers benefited from this government support during the 3-month period (Bonsu, Citation2021). The cost of free water was estimated to be GH¢560 million (US$98 million) and was absorbed by the Ghana government (Ministry of Finance & Economic Planning, Citation2020).

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 presents the literature, and Section 3 describes the Government of Ghana’s COVID-19 Intervention. Section 4 describes the data collection and model estimation methods. Section 5 presents and discusses the results. Section 6 presents conclusions and recommendations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical review

The paradigm view of Ferguson (Citation2015), in the “Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution,” uses observations on poor black South Africans where the government used cash transfer offers to provide support. Ferguson (Citation2015), hold the view that, the long-term sustainable strategy of building personal financial resilience of individual is through the provision of skills and capabilities to enable the individual to engage in economic activity, rather than government providing cash transfer offer to the economically excluded. The earnings from the economic activity then cater for the personal and family needs of the individual in good and in bad times. This new productive distribution approach, held by Ferguson (Citation2015), contrasts with the non-productive welfare distribution approach, in which the government regularly pays cash transfer offers to the unemployed or the poor, in the form of welfare packages or social assistance. The overall view is that cash transfer offers are not a sustainable way to deal with wealth distribution; rather, skills and capabilities position people better at dealing with economic challenges.

The flypaper effect can also be discussed in the context of government freebies during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Fisher (1982), the flypaper effect is "money sticks where it hits," implying that money transferred to the public sector often results in greater public sector spending than an increase in local citizen income, while money transferred to the private sector tends to remain in the private sector. The COVID-19 pandemic presented the government of Ghana the opportunity to transfer money in various forms of freebies, such as free water and electricity to residential users, to alleviate the burden of the virus on citizens. According to Isik et al. (Citation2023), a flypaper effect exists for both the state and provincial governments in Nigeria and South Africa in federal spending. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Nurlaela Wati et al. (Citation2022) showed that in Indonesia, there was a flypaper effect, as the local government utilized general allocation funds instead of local own-source revenue for local spending. The authors reveal that there is a flypaper effect during crisis and non-crisis spending by the government in developing countries in an attempt to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, a study conducted on microenterprises in urban Ghana by Fafchamps et al. (Citation2014) argued that the fly paper effect exists, in that from the experiments conducted, capital support sticks in business, but cash support does not stay in microenterprises. For female-owned businesses, only in-kind support increases profit. Two theoretical propositions, the “Give a Man a Fish: Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution,” and the flypaper effect are the domain of this paper, however the flypaper effect is the main theory that support this paper. This is so because during the COVID-19 pandemic government through its social welfare support, spent a lot of public funds to reduce the effect of the virus. It is believed that governments have amassed political capital from these COVID -19 interventions to themselves more than the benefits that the beneficiaries have accrued.

2.2. Empirical review

The pandemic phase of COVID-19 brought to the fore the politics of distribution, which assumed a global dimension. During this time, many governments provided emergency support for citizens, focusing mainly on the poor and the venerable. The “Give a Man a Fish” and the flypaper effect manifested itself in so many ways, from free water, electricity, cash offers among others and loan support to businesses particularly micro, small and medium enterprises and poor households.

The literature on governmental and non-governmental support during the COVID-19 pandemic is vast and can be classified as health- and non-health-related, and a complete review is beyond the scope of this paper. Researchers including Ashraf (Citation2020), Akrofi and Antwi (Citation2020), Prentice et al. (Citation2020) have investigated non-health related government intervention of COVID-19. While government support is welcome in difficult times, such as the COVID-19 pandemic period, it comes in varying forms and mostly for the short term. According to Ashraf (Citation2020), in more than 77 countries, government announcement of intervention by way of social distancing had a positive and negative impact, while containment measures via health and economic intervention, such as income support, had a positive impact on stock market returns. Arndt et al. (Citation2020) provide evidence that social distancing and lockdown have enormous economic costs and negative consequences on factor income distribution in South Africa. Focusing on the energy sector, Akrofi and Antwi (Citation2020) revealed that government support in Africa can be geographically analysed. Countries in sub-Saharan Africa adopted the provision of free electricity, suspension of bill payments, and, in some cases, VAT exemptions on electricity bills. On the other hand, Northern African countries used reliefs broadly targeting the oil and gas sectors.

Government intervention and support for COVID-19 can also be analysed at the macro and micro levels through the lens of health and economic policies. According to Loayza and Pennings (Citation2020), two phases of macroeconomic intervention programmes exist that developing economies can pursue: the relief stage and the aftermath stage. The relief stage is a short-term measure that is mainly within the domain of the social distancing policy. The aftermath phase concerns recovery measures; the aim during this phase is to revitalize the economy to regain its pre-COVID-19 level. The strategies in this stage are activities that prevent the collapse of the economy through relief measures and expansionary monetary and fiscal policy with an alternative of maintaining macroeconomic stability, with much emphasis on providing for the poor and vulnerable.

From Aharon and Siev (Citation2021), COVID-19 government intervention in 19 emerging countries is rather mixed, and government restrictions are associated with negative market returns, possibly due to the anticipated adverse effects on the economy. They stress that there is a positive market response to direct income support and a negative response to debt or contract relief from the government. On their part, public education results in creating fear among the populace concerning the pandemic, according to Doherty et al. (Citation2020), who assessed public education, impact, and government intervention for COVID-19 in Nigeria. The authors revealed that 70 percent of the respondents in an online survey believed that government intervention was inadequate. Wang et al. (Citation2021), researched into how government support affected hotels and leisure stocks in 8 European countries and the United States. The findings show that under adverse market conditions, such as during the pandemic, containment and health measures by the government result in an increase in stock returns, while stringency measures and economic support measures promote stock returns and restrain stock market volatility.

Baldwin and Di Mauro (Citation2020) and Brodeur et al. (Citation2020) provide a comprehensive review of COVID-19 economics-related literature. These reviews show that a large proportion of individuals and households in developed economies have suffered economic losses resulting from COVID-19, for which social welfare packages came in handy to provide comfort. A snapshot of research that has considered COVID-19 health interventions is not limited to Frank (Citation2020); Silva et al. (Citation2020), Hadjidemetriou et al. (Citation2020) and Fitzpatrick et al. (Citation2020). The overall expectation is that these health and non-health interventions will signal government efforts to fight COVID-19, boosting public and investor confidence in the economy.

These freebies do not strictly fit Ferguson’s Give a Man a Fish Reflections on the New Politics of Distribution because of the non-structural nature of the need to provide support during the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments have implemented COVID-19 support schemes across many economies, including developed economies. Therefore, the question one can ask is, in an emergency and pandemic condition like COVID-19, can the “give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime”, hold? The proposition of Ferguson (Citation2015) does not hold. In normal, stable, and predictable economic conditions such as the pre-COVID-19 era, one can say that the “Give a man a fish adage…” may be workable.

Although the evidence from these studies is worthwhile, the response and appreciation of recipients through scientific research inquiry into direct social intervention support, such as free water and subsidized electricity for households during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in developing countries, is lacking. This is particularly so in a frontier market economy like Ghana, a developing economy that grappled with COVID-19 and its attendant socioeconomic challenge. This study provides deeper insight into how government social intervention in the form of free water and subsidized electricity was received during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, how social support or interventions of similar types should be deployed in similar future conditions to achieve the optimal outcome is an additional concern of this study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

Ghana’s lockdown spanned March 30 to April 19, 2020. The present study relied on a cross-sectional data of locked-down cities and unlocked cities in Ghana. In collecting the data, using an interviewer and interviewee direct contact format (e.g., face-to-face) poses an ethical challenge; therefore, a structured questionnaire was designed and administered using the Google online survey method from April 25 to May 3, 2020. The online questionnaire was administered immediately after the partial lockdown was lifted and after the announcement of the Government of Ghana free water and subsidized electricity of residential users.

The sampling frame included individuals who had access to an electronic mobile or desktop platform such as WhatsApp, Email, among others, and had the capacity to vote in a national election (i.e., were at least 18 years of age). Similar to Amoah and Amoah (Citation2021), the snowball nonprobability sampling technique is ideal for the COVID-19 pandemic. The snowball or chain-referral sampling technique encourages the identified cohort of survey administrators to invite future respondents from among their networks or acquaintances. This process continued as the sample group became larger, similar to a rolling snowball. Generally, the process of completing a questionnaire involves sending a survey link to their cohorts. They, in turn, clicked on the link and read the instructions, which included a statement that encouraged them to voluntarily participate or decline participation. Similarly, the online snowball process allows for voluntary participation of respondents, as they reserve the right to participate or decline participation. Once they are inclined to participate, they go on to complete the survey and forward it to their cohorts, and the process continues. Responses were reported in real time via the Google response platform and collated in Microsoft Excel. It is important to acknowledge that key variables, such as income and education, show a reasonable spread, suggesting the absence of cohort or network effects.

This study used a sample size of 879 respondents. We acknowledge that missing observations are a weakness commonly associated with online surveys. Thus, depending on the estimated model, the number of observations ranged from 365 to 493. Despite the high attrition rate, the number of observations remains sufficiently large to achieve the objectives of this study. Acknowledging that chain-referral is a non-probability sampling technique, and to ensure randomisation and generalisation of our results, a median threshold was used as a cut-off point to generate a random sub-sample from the dataset. The randomised sub-sample is also estimated as robustness checks.

The questionnaire was concise and easy to complete. An average time of five minutes was observed in both the pilot and main surveys. The questionnaire was designed with four main sections. The first section contained questions related to respondents’ demographics, the second section had questions on lockdown and economic well-being, the penultimate section had questions related to lockdown and social intervention, and the last section had lockdown and health-related questions.

The survey activated the Google Questionnaire restriction button, which allowed each respondent only one opportunity to complete the survey. Thus, multiple responses from the same respondent were not possible. The difficulty level of the questionnaire was assessed and 99% of the respondents indicated that the questions were concise and easy to answer.

3.2. Estimation strategy

We modelled people’s preferences for free water and electricity as a social intervention programme implemented by the government of Ghana during the COVID-19 lockdown and its associated determinants. Several publications (see Amoah & Dorm-Adzobu, Citation2013; Greene, Citation2003; Wooldridge, Citation2002) have shown that ordered probit models are ideal for discrete outcome variables when they are inherently ordinal. Given that the dependent variable(s) takes a latent variable form and is unobserved, we present our basic model as:

(1)

(1)

where

is an unobserved variable, vector X represents all explanatory variables,

and

represent a vector of an unknown parameter and the error term respectively. Where the error term is assumed to be normally distributed across the observations. Similarly, we define the observed dependent variable as:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

The observed variables here represent the alternatives the individual respondent had to choose from. Here, the respondent voluntarily chooses an alternative that represents his/her position on the question posed. The chosen option depicts the extent to which an individual’s preference for free water and electricity, free water or electricity, free water only, and free electricity only is ranked.

Next, we present the probabilities with as parameter thresholds. Now, we present the associated probabilities as

Furthermore, we acknowledge that for the expressed probabilities to appear positive, the following condition should exist:

Given that the coefficients of the probabilities are different from the associated marginal effects, we present an equation that the probability of changes in the dependent variable with respect to changes in the independent variable (

).

For estimation purposes, we present the unobserved variable, and the independent variables in an econometric form as:

where the dependent variable, preference for free water and/or electricity by the government (Pref). The dependent variable takes four forms. The first form is obtained when the respondent chooses either water or electricity; the second form is obtained when the respondent prefers none of the freebies (i.e., no preference for water or electricity); the third form is obtained when the respondent chooses both water and electricity. The dependent variable is expressed as a function of marital status of the respondent (MS) with Married = 1, unmarried = 0, amount of savings in Ghana cedis depleted during the COVID-19 lockdown (Sav); COVID-19 lockdown intervention recipient (or beneficiary) with recipient = 1, non-recipient = 0 (Rec); support for lockdown decision with support = 1, non-support = 0 (Dec); respondent with knowledge or education about public health with knowledge =1 and no knowledge = 0 (P); age of the respondent in years (Age), take-home income of the respondent in Ghana cedis (Y), formal education completed by the respondent with educated = 1 and uneducated = 0; respondent’s income and education interaction (Y × Edu), support for the decision of lifting the lockdown with support = 1, non-support = 0 (Lift),

is the error term as already defined. Next, is presented to show the distribution of dependent variable used in the regression model.

4. Results and discussion

From , we show that 71% of the respondents supported (indicated Yes to) the free utility services, 14% were indifferent, and 15% disapproved (indicated No). This provides evidence that the majority of people in Ghana were positive about free water and electricity services in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the independent variables.

On average, 45% of the respondents were married, whereas 55% were unmarried. For an average of Ghs46.23, savings were reported to have been depleted. These depletions could mainly be attributed to withdrawals or expenses made from mobile money wallet which are not too huge as compared to withdrawals from the traditional commercial banks. Apart from free water and electricity, 21% received other freebies (e.g., foodstuffs and personal protective equipment) from the government and other donors that were mainly targeted at the poor. This evidence is similar to what is reported by Ashraf (Citation2020), Akrofi and Antwi (Citation2020), Prentice et al. (Citation2020) who researched on non-health related government intervention and support of COVID-19. Most developing countries do not have people who can survive their income and savings for over three weeks. Thus, an overwhelming majority (94%) supported the COVID-19 lockdown. In addition, on average, most respondents agreed (coded as 3.55, which is approximately 4) to having public health knowledge. In the sample, the average age of respondents is approximately 48 years. The average income of the respondents was Ghs3,486.12. Finally, 38% of the respondents supported lifting the lockdown.

4.1. Diagnostics

In econometric modelling, it is ideal to undertake and report some diagnostics of the model to authenticate the validity of the estimates. First, multicollinearity was investigated to ascertain whether the independent variables were highly correlated. As shown in , the highest level of correlation (ρ = 0.55) was found between age and marital status. Therefore, multicollinearity was not severe enough to alter the validity of the estimates. All models were estimated with robust standard errors to address the problem of heteroscedasticity. Further, to account for unobserved heterogeneity commonly associated with different geographical areas (i.e., districts), we controlled for district fixed effects in the model.

Table 2. Ordered probit regression results.

In the ordered probit regressions, Wald chi-square tests were used to ascertain how the overall contribution of all variables to the estimated model statistically explains the dependent variable. and show evidence of a statistically significant Wald chi2, suggesting that all variables collectively have a statistically significant impact on the dependent variables. To use a metric to show the goodness of fit, R-squared was used in the case of traditional models such as ordinary least squares (OLS). In , the R-Squared are 13.00, 13.40, 10.66 and 10.67 respectively, these R-Squared, indicates the percentage of the variance in the dependent variable that the independent variables explain collectively. Similarly, the pseudo-R2 model is used in non-traditional models such as the ordered probit regression model. These metrics seek to explain the proportion of variance in the dependent variable accounted for by the independent variables in the regression model, or how well the model predicts the observed outcome. In and , the Psuedo R-2 are 0.0816 and 0.1155 respectively.

Table 3. Ordered probit regression results with a median cut-off (randomised data).

Table 4. Disaggregated OLS regression results for water and electricity.

reports the ordered probit regression results of an individual’s preferences for free water and/or electricity offered by the government as part of the COVID-19 social intervention programmes in Ghana. The regression model includes control variables for city-specific effects and robust standard errors to account for the possible heteroskedasticity commonly associated with cross-sectional studies. We further estimated the predicted margins for all three possible choices available to respondents.

We find that, on average, married respondents are more likely to be indifferent or say no to the free utility services the government made available during the COVID-19 lockdown than unmarried respondents. Similarly, relative to unmarried respondents, married respondents are less likely to say yes to free utility services. This can be explained by the fact that married people with shared responsibilities are capable of absorbing the utility burden and would not mind whether it exists for free. However, the unmarried, who had no one to share household responsibilities, responded positively to the government’s free utility services. Thus, the unmarried with less support appreciated free utility services more than the married.

It is evident in this study that, on average, respondents who depleted their savings as an absorptive capacity to economic shocks during the lockdown are less likely to say no or appear indifferent to free utility services. Stated differently, those who depleted and felt the impact of economic shocks are more likely to say yes to free utility services, which is comparable to Baldwin and Weder di Mauro (Citation2020) and Brodeur et al. (Citation2020), who posit that COVID-19 has had a negative economic effect on many individuals and households. During the COVID-19 lockdown, apart from the free water and electricity, not all respondents received other forms of targeted support (e.g., foodstuffs and personal protective equipment) shared by the government, non-governmental organisations, religious groups among others. On average, respondents who received other forms of support are less likely to be indifferent or say no to free utility services. Thus, those who received other forms of freebies are more likely to say yes to the utility services. By implication, the poor who were targeted by the government and other donors are more likely to appreciate the free utility services relative to those who are generally considered non-poor and were not targeted.

Knowledge is a key factor that influences people’s behaviour in the fight against COVID-19 and more so for young adults, if they are to abide by public health education from health authorities, Nivette et al. (Citation2021), while Dabbagh (Citation2020) prescribes person to person health education about COVID-19 using Instagram from a cross-sectional study in Iran. From our results, relative to respondents who are not well informed about public health issues, we find that on average, respondents who indicated that they have public health knowledge are less likely to be indifferent or say no to free utility services. Stated differently, respondents with public health knowledge are more likely to affirm their support for the free utility services.

On people’s demographic characteristics, we find that age and income are not statistically significant but education. That is, respondents with formal education are less likely to be indifferent or say no to free-utility services. Thus, those with formal education are more likely to say yes to free utility services. Further, we interacted income and education to investigate the extent to which individuals with higher incomes and education influence their behaviour. We have evidence that higher-income respondents who are educated are more likely to be indifferent or say no to the free utility services, which corroborates Arndt et al. (Citation2020) that labour with low education would need government support during movement restriction conditions such as COVID-19. Consequently, the same respondents are less likely to say yes to the free utility services. Relatively, this implies that the educated poor are more likely to appreciate free utility services.

Globally, after some countries especially Ghana the first African to lift a lockdown, diverse views were expressed. While some people supported the lifting of the lockdown for economic reasons, others thought that economic reasons were not justified. Generally, it has been observed that the poor who were experiencing hardship and found it difficult to make ends meet supported the lifting of the lockdown while the non-poor shared the continuous lockdown view. Our results present empirical evidence that respondents who pledged their support for lifting the lockdown appreciated the free utility services more than those who were against lifting the lockdown. By implication, those who needed economic survival were positive about the free utility services.

4.2. Robustness check

From , we present the results of our subsample, which is based on the sample’s median cut-off. We show evidence that, except savings that were depleted during the COVID-19 lockdown, which had a consistent sign but were insignificant, all the other variables were consistent in sign and significance with the results in . This provides overwhelming evidence that the result from our randomised sub-sample is consistent with the results from the full sample. By implication, our results can be generalised to the entire country without recourse to the non-probability sampling technique used for the full sample.

4.3. Preference for free utility: a disaggregated analysis

Ghana’s most recent annual estimate for household water and electricity expenditure as provided by the World Bank (Citation2020) is 453.91 and 642.98 ($PPP), respectively. In this study, we rescaled the household level expenditure into individual level expenditure. We further interacted the individual level estimates with individual’s responses to free water and electricity to obtain a continuous data on utility expenditure by individuals based on their responses for the free utility services during the COVID-19 lockdown (Utility Expenditure Index). From , we disaggregate the free utility services into water services only and electricity services only. We estimated the drivers of both services independently.

First, we have evidence of a negative and statistically significant relationship between marital status and the Utility Expenditure Index. That is, relative to the unmarried, individual married respondents spend less on both services due to shared responsibility, and of course, are less likely to appreciate the free water and free electricity services. This result affirms the earlier aggregated results. Again, if the respondent is a beneficiary or recipient of the other forms of support during the COVID-19 lockdown, we find a positive relationship for both water and electricity.

Furthermore, we find a positive relationship between beneficiaries or recipients of the other forms of support during the COVID-19 lockdown and the Utility Expenditure Index. Meaning, beneficiaries who are mainly the targeted poor spend more on water and electricity, and thus, they are more likely to appreciate the free water and electricity services. This evidence is only statistically significant for water but not electricity. This is because alternative crude energy sources exist but certainly not for improved water sources which is critical to good health. Similarly, there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between respondents who supported the lockdown decision and the Utility Expenditure Index. By implication, respondents who support the lockdown decision spend more on water and electricity and indeed, they are more likely to appreciate the free water and free electricity services as compared to those who do not support the lockdown decision. This result is consistent with the earlier aggregated results.

Moreover, there is a positive and statistically significant relationship between respondents who have public health knowledge and the Utility Expenditure Index. This means that relative to respondents without public health knowledge, those with public health knowledge spend more on water and electricity, and as expected, they are more likely to appreciate the free water and free electricity services. This result corroborates with the earlier aggregated results.

Also, age has a positive effect, albeit insignificant. Likewise, income has a positive effect and exhibits a statistically significant effect on the Utility Expenditure Index. That is higher-income respondents spend more on electricity, and thus, they are more likely to appreciate the free electricity services. This is because the cost of electricity is high, and that respondent would prefer relief from such a high-cost burden.

Furthermore, there exists a positive relationship between respondents who supported the decision to lift the lockdown and the Utility Expenditure Index. This result is only significant in the case of water and not electricity. That suggests that respondents who supported the decision to lift the lockdown spend more on water, and as expected, they are more likely to appreciate the free water services. This is plausible when respondents lack inbuilt residential plumbing fora regular flow of water.

Household size is included in this model because of the role it plays in accessing domestic water. The results show evidence of a positive and statistically significant relationship between household size and the Utility Expenditure Index. This implies that larger household sizes spend more on water, hence they tend to appreciate the free water services. Also, we included an interaction between income and household size and find a negative and statistically significant relationship between larger household sizes with higher income levels and the Utility Expenditure Index. Thus, larger household sizes with higher incomes who spend more on water, yet have the financial muscle to absorb it easily, less appreciated the free water services. It goes without saying that sometimes rich households perceive freebies as an incentive for the poor and may not want to be associated with it.

Also, wealth depleted during the lockdown has a positive and statistically significant effect on the Utility Expenditure Index. Thus, respondents who believe that they had to deplete their wealth during the lockdown, spent more on water and are more likely to appreciate the free water services. Consistently, respondents whose savings depleted during the lockdown also exhibit a positive and statistically significant relationship with the Utility Expenditure Index, thus making them appreciate the free electricity services. We find evidence to argue that education has a positive and statistically significant relationship on the Utility Expenditure Index. This means that educated people spend more on electricity and appreciates the free electricity services. Further, we interacted education and income, and find that educated respondents with higher incomes spend less on electricity due to their environmental consciousness and energy efficiency practices (Amoah et al., Citation2018), and thus, they are less likely to appreciate the free electricity services.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we present the macro-level government of Ghana’s support for businesses as a result of the COVID-19. These are the Ghc 1 billion stimulus package for households and small businesses and the intention of the government of Ghana to reduce spending on goods, services, transfers, and capital investment to free up funds to support COVID-19 intervention. Additionally, the government announced a three-and-a-half-year GHc100 billion COVID-19 Alleviation and Revitalization of Enterprise Support Programme with proposed funding from both the public and private sectors. In response to COVID-19, the central bank reduced the policy rate by 1.5 percent and the bank reserve requirement by 2 percent to ease funds into the economy.

Specifically, at the individual and household levels, the government provided residential users with subsidized electricity for three months and a minimum of nine months of free water for all residential users. As part of our findings, we provide evidence that about 71 percent appreciated free utility services, 14 percent were indifferent, and 15 percent also indicated their disapproval. In addition, we show that educated respondents with higher incomes are less likely to appreciate such freebies. Likewise, the unmarried, those who depleted their savings, those who received support, the poor, respondents with public knowledge about COVID-19, and those who are educated but poor are more likely to appreciate free utility services.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the complexities of public sentiment surrounding government-sponsored free-utility services in response to the economic challenges resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The study reveals a significant level of support for these services, with approximately 71 percent of respondents expressing their approval. Notably, the research also underscores the role of education and income levels in influencing individuals’ attitudes towards these freebies, providing valuable insights for policymakers navigating the delicate balance between public welfare and economic stability.

5.1. Policy implication

We recommend continual government support until the COVID-19 pandemic is curtailed and life returns to normalcy. In addition, NGOs should continue to support the less privileged during such difficult times. What is needed in this regard is for the government, NGOs, and other donors to undertake an effective targeting of beneficiaries of its freebies during this time, as the evidence provided shows that aside from health concerns, it is the poor who appreciate these free utilities the most. The government of Ghana should also pursue strategies that would make it possible for people to work both onsite and offsite based on their job roles and skills. This job flexibility will keep many people employed and also reduce workplace management costs, as those who are employed and have a high income do not place a high premium on free utilities in situations such as COVID-19.

This study focused on the free water and electricity provided by the government of Ghana during the COVID -19 pandemic phase. The provision of free food and other freebies was not considered in this study. We suggest that to have a full appreciation of all the freebies provided during the COVID-19 pandemic phase, further studies should focus on the full complement of freebies provided both from the public and private sectors, especially those targeted at the poor, to enrich our understanding of social support during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors contribution

Benjamin Amoah: Conception of research idea, introduction, literature review, analysis, conclusion and recommendation, and review of paper.

Anthony Amoah: Conception of research idea, design of data collection tool, method, estimation of results, proof reading and review of paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their supportive comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Amoah

Benjamin Amaoh (PhD) He is a finance and banking expert from the Business School of the University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana.

Anthony Amoah

Anthony Amoah (PhD) He is an applied economist from the University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana.

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh, C. (2020). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104245.

- Aharon, D. Y., & Siev, S. (2021). COVID-19, government interventions and emerging capital markets performance. Research in International Business and Finance, 58, 101492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101492

- Akrofi, M. M., & Antwi, S. H. (2020). COVID-19 energy sector responses in Africa: A review of preliminary government interventions. Energy Research & Social Science, 68, 101681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101681

- Amankwaa, G., & Ampratwum, E. F. (2020). COVID-19 ‘free water’ initiatives in the Global South: what does the Ghanaian case mean for equitable and sustainable water services? Water International, 45(7-8), 722–729. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2020.1845076

- Amoah, A., & Amoah, B. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a buzz of negativity with a silver lining of social connectedness. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 38(1), 178–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-07-2020-0132

- Amoah, A., & Dorm-Adzobu, C. (2013). Application of contingent valuation method (CVM) in determining demand for improved rainwater in coastal savanna region of Ghana, West Africa. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 4(3), 1–24.

- Amoah, A., Hughes, G., & Pomeyie, P. (2018). Environmental consciousness and choice of bulb for lighting in a developing country. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 8(1), 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-018-0159-y

- Arndt, C., Davies, R., Gabriel, S., Harris, L., Makrelov, K., Robinson, S., Levy, S., Simbanegavi, W., van Seventer, D., & Anderson, L. (2020). COVID-19 lockdowns, income distribution, and food security: An analysis for South Africa. Global Food Security, 26, 100410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100410

- Ashraf, B. N. (2020). Economic impact of government interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: International evidence from financial markets. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 27, 100371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2020.100371

- Baldwin, R., & Di Mauro, B. W. (2020). Economics in the Time of COVID-19: A New eBook. Vox CEPR Policy Portal, 2(3).

- Barker, M., & Russell, J. (2020). Feeding the food insecure in Britain: learning from the 2020 COVID-19 crisis. Food Security, 12(4), 865–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01080-5

- Bonsu, O. K.-M. (2021). The budget statement and economic policy of the government of Ghana for the 2021 financial year presented to parliament on Friday, 12th March. Accra, Ghana.

- Brodeur, A., Gray, D. M., Islam, A., & Bhuiyan, S. (2020). A literature review of the economics of covid-19. Journal of Economic Surveys, 35(4), 1007–1044.

- Chen, H., Liu, S., Liu, X., & Yang, D. (2022). Adversity tries friends: A multilevel analysis of corporate philanthropic response to the local spread of covid-19 in China. Journal of Business Ethics: JBE, 177(3), 585–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04745-z

- Dabbagh, A. (2020). The role of Instagram in public health education in COVID-19 in Iran. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, 65, 109887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinane.2020.109887

- Desai, D., & Randeria, S. (2020). Unfreezing unspent social special-purpose funds for the COVID-19 crisis: Critical reflections from India. World Development, 136, 105138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105138

- Doherty, V. F., Olumide, O. A., Abdullahi, A., Oluwatosin, A., & Folashade, A. E. (2020). Evaluation of knowledge impacts and government intervention strategies during the COVID–19 pandemic in Nigeria. Data in Brief, 32, 106177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106177

- Fafchamps, M., McKenzie, D., Quinn, S., & Woodruff, C. (2014). Microenterprise growth and the flypaper effect: Evidence from a randomized experiment in Ghana. Journal of Development Economics, 106, 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.09.010

- Ferguson, J. (2015). Give a man a fish: Reflections on the new politics of distribution. Duke University Press.

- Fitzpatrick, K. M., Drawve, G., & Harris, C. (2020). Facing new fears during the COVID-19 pandemic: The State of America’s mental health. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 75, 102291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102291

- Frank, T. D. (2020). COVID-19 interventions in some European countries induced bifurcations stabilizing low death states against high death states: An eigenvalue analysis based on the order parameter concept of synergetics. Chaos, Solitons, and Fractals, 140, 110194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110194

- Government of Ghana. (2020). July Mid-Year Budget, Ministry of Finance, Accra Ghana.

- Greene, W. H. (2003). Econometric analysis. Pearson Education India.

- Gupta, S., Montenovo, L., Nguyen, T. D., Rojas, F. L., Schmutte, I. M., Simon, K. I., Weinberg, B. A., & Wing, C. (2020). Effects of social distancing policy on labor market outcomes. (No. w27280). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Hadjidemetriou, G. M., Sasidharan, M., Kouyialis, G., & Parlikad, A. K. (2020). The impact of government measures and human mobility trend on COVID-19 related deaths in the UK. Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 6, 100167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100167

- Isik, A., Golit, P. D., & Terhemba Iorember, P. (2023). Unconditional federal transfers and state government spending: The flypaper effect in Nigeria and South Africa. Modern Finance, 1(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.61351/mf.v1i1.46

- Loayza, N. V., & Pennings, S. (2020). Macroeconomic policy in the time of COVID-19: A primer for developing countries. World Bank Research and Policy Briefs (147291).

- Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. (2020). Mid-year review of the budget statement and economic policy of the Government of Ghana and supplementary estimate for the 2020 financial year. https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/budget-statements/2020-Mid- Year-Budget-Statement_v3.pdf

- Nivette, A., Ribeaud, D., Murray, A. L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Hepp, U., Shanahan, L., & Eisner, M. (2021). Non-compliance with COVID-19-related public health measures among young adults: Insights from a longitudinal cohort study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 268, 113370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113370

- Nkrumah, R. K., Andoh, F. K., Sebu, J., Annim, S. K., & Mwinlaaru, P. Y. (2021). COVID-19 water and electricity subsidies in Ghana: How do the poor benefit? Scientific African, 14, e01038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e01038

- Nurlaela Wati, L., Ispriyahadi, H., & Habibi Zakaria, D. (2022). The flypaper effect phenomenon of intergovernmental transfers during the Covid-19: Evidence from Indonesia. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta u Rijeci: časopis za Ekonomsku Teoriju i Praksu/Proceedings of Rijeka Faculty of Economics: Journal of Economics and Business, 40(2), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.18045/zbefri.2022.2.353

- Prentice, C., Chen, J., & Stantic, B. (2020). Timed intervention in COVID-19 and panic buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 57, 102203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102203

- Silva, P. C., Batista, P. V., Lima, H. S., Alves, M. A., Guimarães, F. G., & Silva, R. C. (2020). COVID-ABS: An agent-based model of COVID-19 epidemic to simulate health and economic effects of social distancing interventions. Chaos, Solitons, and Fractals, 139, 110088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110088

- Wang, Y., Zhang, H., Gao, W., & Yang, C. (2021). COVID-19-related government interventions and travel and leisure stock. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 49, 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.09.010

- Webb, C. (2021). Giving everyone a fish: COVID-19 and the new politics of distribution. Anthropologica, 63(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.18357/anthropologica6312021275

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach, 2003. South-Western College Publishing.

- World Bank. (2020). Global consumption database, Ghana. Retrieved September 29, 2020, from http://datatopics.worldbank.org/consumption/country/Ghana.

Appendix

Table A1. Pairwise correlation matrix.

Table A2. Pairwise correlation matrix.