?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

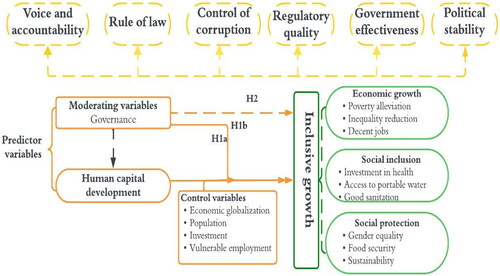

The study examines the impact of human capital and governance on inclusive growth in Africa. It further explores how governance dynamics influence the relationship between human capital and inclusive growth. Drawing on macro data spanning 43 African countries from 2005 to 2020 and employing the two-step system generalized method of moments (SYS-GMM) estimation technique, the following findings emerge. First, human capital promotes inclusive growth in Africa, while governance has a diminishing effect. Second, the six governance indicators counteracted the positive effect of human capital on inclusive growth. This means that negative governance dynamics completely nullify/dampen the positive effect of human capital on inclusive growth. In conclusion, the anticipated benefits of human capital in fostering inclusive growth may remain elusive unless significant improvements are made to Africa’s weak institutional fabric.

IMPACT STATEMENT

This research sheds light on SDGs 4 and 10 by providing a comprehensive understanding concerning the interaction between human capital development and governance, and their effect on inclusive growth in the context of Africa. This study establishes that human capital development promotes inclusive growth whereas governance hinders it. Compelling evidence from the interactive analysis shows that governance nullifies the positive effect of human capital on inclusive growth. The main message from this research is that Africa’s poor economic, political, and institutional governance undermines the role of human capital development in inclusive growth. This research calls for proactive investments that enhance Africa’s institutional fabric and human capital development.

1. Introduction

The conjecture of this study stems from the important role of human capital development and good governance on inclusive growth in Africa and this is motivated by four main fundamentals in scholarly journals and policy studies. Specifically: (i) the relevance of shared prosperity in light of SDG goals; (ii) the relevance of human capital development on inclusive growth; (iii) the effect of governance on inclusive growth; (iv) how good governance affects human capital development on inclusive growth in Africa. These four fundamental elements drive the focus of this paper, as detailed in the subsequent paragraphs.

Africa has recorded impressive economic growth rates in the past two decades (World Bank, Citation2020; IMF, Citation2021). Indeed, it appears that the continent has achieved remarkable gains in line with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8. For instance, Africa’s growth rate of 4.9% in 2010 compared well with that of the European Union (2.1%), Asia (9.3%), North America (2.6%), Latin America and the Caribbean (5.8%). Even amidst the challenges brought about by the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, where all countries experienced negative growth rates, Africa’s decline was -1.9%, which compared favorably to that of Europe (-6.6%), North America (-3.5%), and Latin America and the Caribbean (-7.7%), with the exception of Asia (-0.2%). Notwithstanding these gains, pressing issues, such as high unemployment, income inequality, societal unrest, and low levels of human development, still linger in African countries (Ofori & Asongu, Citation2021; Onifade et al., Citation2020). This indicates that recent growth gains in Africa do not benefit the masses, highlighting the need for inclusive growth. As defined by Anand et al. (Citation2013), inclusive growth is a type of growth that benefits all citizens. It is argued that ensuring all segments of the population actively contribute to the development process is essential (Raheem et al., Citation2018). Prior to Africa falling into recession in 2020, there was an agenda to stimulate pro-poor economic growth among various subpopulations. This commitment is evident in initiatives such as the Continental Framework, "The Africa We Want" (Africa Union, Citation2015). Therefore, exploring the issue of inclusive growth is pertinent, particularly considering that African countries are often characterized by porous growth trajectories.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, Citation2021), persuing non-inclusivity can be detrimental to human development and, by extension, sustainable development. Unsurprisingly, in 2020, the coronavirus pushed approximately 95 million people into extreme poverty bracket (World Bank, Citation2020).

Human capital plays a pivotal role in fostering economic growth and shared prosperity in both developing and advanced economies. Despite numerous studies exploring its various definitions and interconnections with other aspects of economic growth, the impact of human capital on inclusive growth remains relatively understudied. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to the literature on inclusive growth by investigating the effect of human capital development on Africa’s pursuit of shared growth.

Our argument is supported by the growing scholarly idea that the glaring disparities between advanced and developing countries stem from human capital investment (Acemoglu et al., Citation2014; Ali & Son, Citation2007; Hanushek et al., Citation2008). For instance, human capital theory holds that human capital, consisting of the knowledge and skills acquired through investment in training and education, impacts shared prosperity (Hanushek, Citation2016; Mankiw et al., Citation1992; Romer, Citation1990). We reckon that in marginalized and low-income societies such as Africa, investments in human capital can affect shared growth gains in several ways. First, for a given level of technical progress, human capital development can accelerate productivity and raise income levels (Mankiw et al., Citation1992). Second, human capital development can stimulate growth and productivity through technological advancement, research and development, and new inventions/innovations (Castelló‐Climent & Doménech, Citation2008; Lucas, Citation1988; Romer, Citation1986). This can generate socio-economic opportunities that reverberate throughout Africa. Third, human capital development can build the capacity of the masses to withstand socioeconomic shocks and cushion economic agents to take advantage of incentives, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), for their well-being (UNDP, Citation2017).

Despite these plausible inclusive growth-human capital linkages, there are striking gaps in human capital development across Africa compared with North America, Western Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean, according to the World Economic Forum (WEF, Citation2017). This suggests that the 'blessings’ associated with human capital development may not be sufficiently strong to engineer inclusive growth across Africa. In this regard, we argue that, in Africa, where access to quality education and training is costly (Canlas, Citation2016; Kamah et al., Citation2021), effective governance could have a crucial influence on shared prosperity.

Our position follows the scientific argument that governance, defined as the "institutions, mechanisms and practices through which governmental powers are exercised", matters for multidimensional human development, shared prosperity, and social progress (Ivanyna & Salerno, Citation2021). This is also supported by evidence indicating that good governance promotes equal access to higher education, skill development, quality healthcare, and equal opportunities for human development (Farayibi & Folarin, Citation2021). Furthermore, quality institutions oversee the delivery of healthcare, investment in technology, innovation, the creation of stable jobs, and effective systems for controlling corruption to ensure that public funds benefit all citizens (Henri, Citation2019; Calderón & Servén, Citation2014; Mungiu-Pippidi, Citation2015).

Although previous studies have highlighted the need for inclusive growth in Africa by focusing on the one-on-one relationship between governance and human capital development for shared growth, a glaring research gap remains regarding how the former interacts with the latter to foster inclusive growth. Specifically, studies exploring how governance interacts with human capital to influence shared prosperity in African countries are scarce. Most empirical studies have focused on the one-to-one relationship between human capital, governance, and inclusiveness. However, the combined effects of human capital and governance on inclusive growth in Africa have been overlooked. No study has investigated the conditional and unconditional effects of human capital and governance on inclusive growth in Africa.

Our study contributes to the existing research by investigating the direct (unconditional) and indirect (conditional) effects of human capital development on inclusive growth in Africa. This study examines whether governance moderates human capital to influence inclusive growth. Using sample data from 43 African countries spanning 2005-2020, we employ the two-step system generalized method of moments (SYS-GMM) estimator to investigate the study. The findings reveal that human capital development fosters inclusive growth in Africa. Second, all our governance dynamics encompassing political stability, the rule of law, voice and accountability, government effectiveness, control of corruption and regulatory quality, hinder inclusive growth in Africa. Third, governance nullifies the positive effect of human capital development on inclusive growth in Africa.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 is devoted to a literature review on the link between human capital, institutional quality, and inclusive growth. Section 3 outlines the data and methodology, and section 4 presents the techniques underpinning the empirical analysis. Section 5 presents and discusses the results. Our conclusions, policy recommendations, and directions for future research are presented in Section 6.

2. Literature review

This section reviews the theoretical and empirical literature. We highlight the human capital-growth theory and the governance-growth theory in the first two sections, and the third section is devoted to empirical reviews of the human capital, governance, and growth nexus.

2.1. Human capital and growth theory

The augmented Solow model initially introduced human capital growth theory by including it as an additional variable by Mankiw et al. (Citation1992). According to the authors, the accumulation of human capital, investment in physical capital, and labour play a salient role in explaining growth differences. Extending the Solow model with endogenous growth, investment in human capital drives economic growth through technological progress, knowledge spillover effects, innovation, invention, blueprints, and incentives for research and development (R&D), as well as replicating modern technologies (Arrow, Citation1962; Romer, Citation1990; Lucas, Citation1988; Grossman & Helpman, Citation1991; Aghion & Howitt, Citation1990). Further, human capital theory highlights that individual workers’ knowledge, abilities, and skills in society can accumulate or improve through education, training, and schooling. This inevitably leads to an increase in the productivity and competitiveness of a nation’s workforce. Therefore, an educated population is productive and efficient in an economy (Becker, Citation1993; Benhabib & Spiegel, Citation1994; Schultz, Citation1961).

Solow (Citation1956) argued that long-run economic growth could be achieved through capital accumulation, labour, and increased productivity driven by endogenous technological progress. To this end, the extant literature has employed such models to analyze the impact of human capital and economic growth in developed, developing, and underdeveloped economies. Based on these theories, we formulate the first hypothesis:

Hypotheses 1a: Human capital development induces inclusive growth in Africa.

2.2. Theory of governance and growth nexus

Institutional quality, on the other hand, refers to the effectiveness of a country’s political, economic, and social institutions in promoting economic growth and shared prosperity. The theoretical contribution of this study is based on Douglass North’s theory of institutions, which draws on neoclassical economic theory and incorporates the political, economic, and social organization of an economy (Acemoglu, Citation2010). The view highlights that institutions may differ between economies over time with technological changes, human capital, and information costs because of collective decision-making. Although organizations are regarded as institutions, individuals create, change, and distort institutions. The author posits that under ideal laissez-faire conditions, property rights, the rule of law, and economic freedom operate effectively and efficiently without the stress of adjustment. In addition, North pointed out that sustained economic growth is achieved through an efficient property rights system (Faundez, Citation2016). The main advantage of this theory is that it demonstrate how inclusive growth is improved when the right institutions exist, and that human capital is contingent on good institutions. Based on the preceding theoretical argument, we formulate the hypothesis 1b:

Hypothesis 1b: Governance induces inclusive growth in Africa.

The link between human capital and institutions is both dynamic and complex. Pronounced levels of human capital can lead to better institutional quality by producing a citizenry that demands good governance and effective public policies. Better institutional quality can stimulate human capital development by providing an enabling and conducive environment for education, training, and innovation. Conversely, institutional quality can influence human capital and enhance growth. For instance, in an economy with a robust legal system and property rights protection, there is a high probability of attracting foreign investors and creating employment opportunities that require highly skilled labourers. In addition, countries with well-functioning educational systems and quality social overhead capital can help develop human capital by providing the necessary incentives and resources for individuals to invest in their education and training. Based on this, we propose hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2: governance interacts with human capital to affect inclusive growth in Africa.

2.3. Empirical review of human capital and growth nexus

From an empirical perspective, numerous studies have been conducted in the field of human capital-led growth. Most of these studies have concentrated on measures such as cognitive skills, school attainment, education, and health as a measure of human capital affecting growth in African countries (Ogundari & Awokuse, Citation2018; Hanushek, Citation2013; Aghion et al., Citation2009; Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2007). Several empirical literature concluded that human capital is a positive driver of economic growth. However, sparse literature exists on human capital and inclusive growth on how it can be a feasible tool for achieving SDG 4, especially in African countries. A few of these studies and findings are examined. For instance, Oyinlola & Adedeji (Citation2019) examined the link between financial development, human capital, and inclusive growth in 19 sub-Saharan African countries from 1999 to 2014. The results suggest that human capital positively influences sub-Saharan African (SSA) inclusive growth. In addition, Oyinlola and Adedeji (Citation2022) also deploy the fixed effects model and panel data of 26 SSA countries from 1995-2014 to find that human capital directly affects inclusive growth. A study investigating human capital, innovation, and inclusive growth in 17 African countries from 1998 to 2014 affirmed that human capital is positively related to inclusive growth using the fixed effect estimator (Oyinlola et al., Citation2021). Despite these results, other empirical studies have reported a negative impact of human capital on growth (Čadil et al., Citation2014; Islam, Citation1995).

2.4. Empirical review of governance-inclusive growth nexus

A study using the system GMM across 11 Asian countries from 1996-2017 contended that quality institutions or good governance positively affect inclusive growth (Sabir & Qamar, Citation2019). A similar study conducted by Ofori and Asongu (Citation2021) in 42 African countries from 1990-2020 using the GMM system found that good governance positively amplifies inclusive growth. A recent study by Ofori and Figari (Citation2023) examined 23 African countries from 2000-2020 using the SYS-GMM to show that good governance matters for inclusiveness. Furthermore, Gupta et al. (Citation2002) found that weak governance, manifesting as corruption, impedes human capital development by either making the cost of human capital development avenues such as health care, education, and other services exorbitant or lowering the quality of such services. Hence, an effective means of curtailing corruption and ensuring transparency among government officials culminates in human capital development and a high economic growth rate (Boikos, Citation2016).

In contrast, the evidence of Rivera‐Batiz (Citation2002) suggests that democracy operationalized as good governance does not provide clear-cut support for the assertion that good governance leads to economic growth or human capital development. This reiterates the findings of Rodrik (Citation1997), who identified an insignificant relationship between institutional quality and human capital development. Notwithstanding this continuous debate, the epistemic community has recently gravitated towards inclusive growth. This growth trajectory will benefit people experiencing poverty and the marginalized segment of the population through increased social opportunities such as employment, income, and capacity development (Ali & Son, Citation2007; Ravallion & Chen, Citation2003; Anand et al., Citation2013).

2.5. Conceptual framework

We draw on recent studies of inclusive growth (Anand et al., Citation2013) to advance a conceptual framework for our study () by capturing the core ingredients of pro-poor growth, social inclusion, and protection. Our framework highlights the links between human capital development, governance, and inclusive growth (Aghion et al., Citation2009; Faundez, Citation2016; Ofori & Asongu, Citation2021). Despite this significant relationship, the factors leading to human capital development, especially in African countries, remain unsettled. The chief among these debates is the link between good governance characterized by voice and accountability, the rule of law, government effectiveness, political stability, regulatory quality, control of corruption, and human capital development (Fayissa & Nsiah, Citation2013; Stephen & Chukwuemeka, Citation2019). To this end, Lyakurwa (Citation2007) argued that good governance results in efficient government expenditure in vital sectors of the economy, including education, health, and R&D, which leads to inclusive growth, as conceptualized in .

3. Data and methodology

3.1. Data and variable justification

This study employed a balanced panel dataset of 43 African countriesFootnote1 from 2005-2020. The study period and choice of countries are motivated by data availability, whereas similar economic factors drive the latter. The study’s primary outcome variable (inclusive growth) is not directly accessible but is generated. This is precipitated by the approach of Ofori and Asongu (Citation2021) and Anand et al. (Citation2013), where inclusive growth was constructed using the utilitarian social welfare function derived from the consumer choice literature, where shared prosperity (growth) is based on (1) income growth (proxied by GDP per capita) and (2) income distribution (measured by the Gini index). The data for this study were obtained from the World Development Indicators (World Bank, Citation2021) and the Global Consumption and Income Project (Lahoti et al., Citation2016). In addition, this index was used by the United Nations to address SDG 8. The data used in this study were sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI, 2021). See Appendices for the procedure used for the construction of inclusive growth.

The key independent variable in this study is human capital, proxied by an index of human capital development based on average years of schooling and rate of return to education. This human capital index is justified because it combines quantitative and qualitative aspects (Hanushek, Citation2016; Hanushek, Citation2013; Adeleye et al., Citation2021; Ogundari & Awokuse, Citation2018). The human capital index is sourced from Penn’s World Tables (Feenstra et al., Citation2015). However, previous studies have widely used secondary or tertiary school enrolment as a measure of human capital, this captures only the quantitative aspects of human capital (Oluwatobi et al., Citation2016).

The second predictor variable of interest was governance, which measures institutional quality. This governance measure is captured by six indicators: regulatory quality, government effectiveness, corruption control, political stability, the rule of law, voice, and accountability. Data for these measures were obtained from World Governance Indicators (World Bank, Citation2021). In addition, the six governance dynamics were used as policy variables/moderating factors that can affect human capital to enhance inclusive growth. Also, this study used economic globalization, population, vulnerable employment, and investment as control variables. These controls for covariate variables rely on prior studies (Ogundari and Awokuse, Citation2018) by considering (1) improving the internal validity of the study, (ii) restricting the influence of confounding and extraneous variables, (iii) econometric prudence, (iv) reverse causality, and (v) reduction of omitted variable bias. Economic globalization captures the effects of foreign direct investment and trade openness. Gross fixed capital formation is used to proxy domestic investment in physical capital, as motivated by the Solow and neoclassical economic development models. Vulnerable employment and an active population are considered to capture the redistribution and structure of the real sector in selected countries (Ofori & Asongu, Citation2021). All these control variables are obtained from KOF index and World Bank. The descriptions of the variables and data sources are provided in .

Table 1. Variable description and sources.

3.2. Theoretical and empirical estimation

3.2.1. Theoretical model

This study is grounded in the Augmented Solow (Citation1956) model and the Mankiw-Romer-Weil (MRW) model developed by Mankiw et al. (Citation1992). These models posit that shared prosperity is a multidimensional concept that requires investments in human capital, and more importantly, institutions that facilitate the efficient allocation of resources (Acemoglu & Autor, Citation2012; Canlas, Citation2016). According to these theories, the critical drivers of shared growth include human capital accumulation, physical capital, technological progress, and institutions. Building on these perspectives of shared growth, our study aligns with the empirical contributions of Ofori and Grechyna (Citation2021), wherein we model inclusive growth (IG) as:

(1)

(1)

Where is inclusive growth,

is countries and

is years;

is total population,

is vulnerable employment,

is investment,

is economic globalization,

is human capital,

is governance, which is composed of voice and accountability (va), control of corruption (cc), regulation quality (rq), the rule of law (rl), government effectiveness (ge) and political stability (ps),

is the interaction term for human capital and governance. Finally,

is an error term.

3.2.2. Empirical estimation

The estimation technique employed in this study is the two-step system Generalized Method of Moments (SYS-GMM), a dynamic panel estimation method proposed by Blundell and Bond (Citation1998) and Arellano and Bover (Citation1995). This study motivated the choice of the GMM technique for four main reasons. First, the number of cross-sections (N = 43) considered in the study must be greater than the period of each cross-section (N > T). This condition is satisfied in our case because we deal with 43 countries based on 15 periods in each country. Second, the predictor variables are assumed not to be strictly exogenous, implying that lagged values of inclusive growth may be correlated with past and current error terms, potentially leading to endogeneity issues. Third, the analysis accounts for fixed country effects and potential collinearity concerns arise when variables included in the regression are likely to be endogenous. Fourth, inclusive growth may influence human capital by addressing inequalities and improving access to education and job opportunities. The SYS-GMM technique offers superior explanatory power compared to ordinary least squares (OLS), fixed effects (FE), and random effects (RE). This approach effectively addresses endogeneity and collinearity issues associated with predictors, particularly in the presence of endogenous factors. The SYS-GMM estimation method accounts for reverse causality and measurement error (Hauk & Wacziarg, Citation2009), which is validated through the Hansen test. The conditions for applying the SYS-GMM technique are satisfied since: (i) there is persistency in inclusive growth between the level series and their first lags. (ii) The study’s longitudinal panel dataset shows cross-country variation, mitigating the issues of limited instrument proliferation and cross-sectional dependencies (Fosu & Abass, Citation2019). The relevant equations for this approach are as follows: incorporating EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) into the SYS-GMM method, we obtain

(2)

(2)

where the description of all variables is the same as EquationEq. (1)

(1)

(1) .

We employ a post-diagnostic test to determine the internal instruments’ validity in the SYS-GMM specification. First, the p-values of the Hansen’s test were insignificant. Second, the absence of first and second-order serial correlation in the residuals should be shown in the AR (1) and AR (2) statistics, whose null hypothesis of no autocorrelation must not be rejected for the latter. Furthermore, the overall models are also significant based on the Wald test. In sum, this study addresses the endogeneity problem because simultaneity is accounted for with the use of internal instruments, and unobserved heterogeneity is also corrected using time-invariant omitted indicators.

The parameters of interest in EquationEq (2)(2)

(2) are

and

Which, capture the unconditional and conditional effects of human capital, governance, and inclusive growth. To test Hypothesis 2, the total/net effects of the conditional effects of human capital and governance on inclusive growth are shown in EquationEq. (3)

(3)

(3)

(3)

(3)

where

represents the average of our six governance indicators (i.e., voice and accountability, control of corruption, regulation quality, rule of law, government effectiveness, and political stability), and all symbols remain as explained above.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Summary statistics

This section presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study. Table 2 shows an average human capital development of 1.8%. Despite this positive value, we observe a low average value of human capital, as evident from the minimum and maximum values. For our moderating variables, the result shows a negative average value for all six governance indicators, such as control of corruption (-0.6%), government effectiveness (-0.7%), political stability (-0.5%), regulation quality (-0.6%), the rule of law (-0.6%), and voice and accountability (-0.5%), with low disparities within the minimum and maximum values. Nonetheless, the negative mean values of all six governance indicators signify Africa’s weak institutional fabric. In addition, the data revealed an average inclusive growth of $0.089 with a variation of 0.1% over the study period. The significant discrepancies between the minimum value of $0.04% and the maximum value of $1 imply that the shared growth among African countries is unstable and unequal. As a usual procedure, we present the correlation matrix () among the quantitative variables used in this study to explore the level of multicollinearity (see the Appendix).

4.2. Unconditional effect of human capital development and governance on inclusive growth

This section presents the findings on the unconditional effects of human capital and institutional quality on inclusive growth in Africa. These findings suggest that the current level of inclusive growth depends on the previous level of inclusive growth in the economy. The lagged level of shared economic growth in Africa, which is the level of persistence, is statistically significant in all models and ranges between 0.5110 and 0.5822 (see columns 1-8). This implies that the previous level of shared prosperity is relevant to current levels of shared prosperity in African countries.

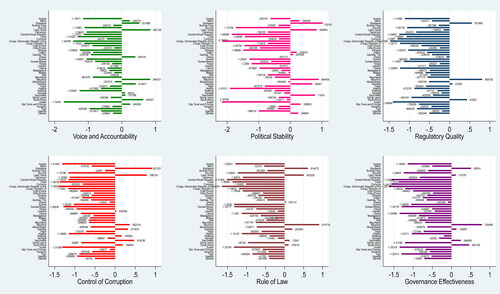

For our first hypothesis, the unconditional effect of human capital promotes inclusive growth in Africa. Notably, the results reveal that a 1% increase in human capital increases inclusive growth by 0.0435 (Column 2), holding all other variables constant. Thus, we found empirical evidence that validates Hypothesis 1a. From columns 3-8, we focus on Hypothesis 1b, where we examine the unconditional effect of governance comprising voice and accountability, government effectiveness, control of corruption, rule of law, political stability, and regulatory quality on inclusive growth. The findings of the six governance indicators are revealing. Particularly, all of our governance dynamics show a negative unconditional effect on Africa’s inclusive growth. For instance, our empirical results show that a 1% improvement in corruption control leads to a 0.0386 reduction in inclusive growth. The results further highlight that a 1% increase in government effectiveness as well as the rule of law leads to a 0.0536 and 0.0805 decrease in inclusive growth, respectively. Similarly, a 1% increase in regulatory quality is related to a 0.0394 decrease in inclusive growth. Similar patterns are observed for voice and accountability. The findings show that an additional 1% increase in voice and accountability reduces inclusive growth by 0.1326, at the 1% significance level. However, a 1% increment in political stability is related to a 0.0312 increase in inclusive growth at the 1% significance level, holding all other factors constant. Therefore, we do not validate Hypothesis 1b.

All the control variables in Column 1 used for the study were statistically significant and positive at 10% and better, except for total population. For instance, a percentage improvement in vulnerable employment, domestic investment, and economic globalization increase inclusive growth by 0.0007, 0.0001, and 0.0007, respectively. Nevertheless, a marginal increase in population reduces inclusive growth, albeit statistically insignificant. Although statistically insignificant, its economic significance stems from the logic that an increasing population in developing economies like Africa yields pressure on human capital development facilities, as well as the budget and expertise necessary for such a course.

Overall, the models are robust, as evidenced by the post-estimation tests. First, the insignificance of our AR (2) p-value indicates the residual absence of second-order serial correlation. Further, the Hansen test means that the instruments used to address endogeneity problems in the model are reliable and valid. Lastly, our Wald Chi-square statistics show that all our variables and models are correctly specified and reliable for explaining the direct effect between human capital, institutional quality, and inclusive growth.

4.3. Conditional (indirect) effects of human capital development on inclusive growth

That said, we now shift to the indirect or conditional effects of human capital and governance on inclusive growth. The interactions between human capital and all six governance measures on inclusive growth are presented in . We consider the contingency effects of governance in the human capital-inclusive growth relationship. The results reveal compelling empirical evidence in Columns 1-6 since all our governance dynamics interact with human capital to reduce inclusive growth in Africa. First, for the control of corruption-inclusive growth interactive term in Column 1, we report a total effect of -0.106 on inclusive growth. This result was computed by considering the unconditional effect of human capital on inclusive growth (-0.1275) and the mean value of corruption control (-0.6078), as shown in . The total/net effect is statistically significant at a 1% significant level and is obtained by imploring the ‘lincom’ command in Stata. Using similar calculations, we determined total effects of -0.0590, -0.0709, -0.0482, -0.0906, and -0.0444 for government effectiveness, rule of law, regulatory quality, political stability, and voice and accountability, respectively, at the 1% significance level. This study establishes that weak governance and institutions in African countries hinder inclusive growth and significantly counteract the positive impact of human capital. These findings provide strong evidence that weak governance framework nullifies the enhancing effect of human capital on inclusive growth, thereby posing a threat to shared prosperity. Our results underscore the need to focus on developing and improving the weak governance structures in African countries for substantial development and inclusiveness. Hence, these findings invalidate Hypothesis 2.

Table 2. Summary statistics (2005–2020).

4.4. Checking for robustness of results

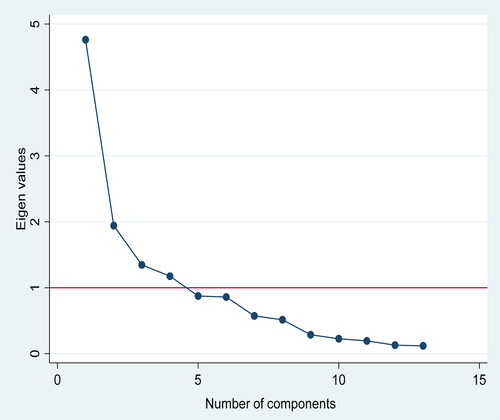

In this section, we assess the robustness of our estimates in and by employing an alternative measure of inclusive growth computed as an index using principal component analysis (PCA). We generated an index by incorporating the suggestions of the Asian Development Bank (Citation2013) and Ofori and Asongu (Citation2021). From , the inclusive growth index was constructed using 13 variables that influence inclusive growth, considering the relevance of the real sector, energy supply, social transfers, and income growth and distribution to inclusive growth. Descriptions of these 13 indicators are presented in . To evaluate the validity or appropriateness of PCA for the correlation of sample size for factor analysis, we provided the correlation matrix, Bartlett test, and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy.

Table 3. Results for the direct effects of human capital and governance on inclusive growth (Dependent variable: Inclusive growth).

Table 4. Results for the indirect effects of human capital and governance on inclusive growth (Dependent variable: Inclusive growth).

Table 5. Indicators used in constructing inclusive growth index.

First, most variables had a strong correlation. From the Bartlett test, there was no intercorrelation among the covariates (p = 0.000). Finally, the overall KMO is approximately 75%, indicating a middling of all 13 covariates for computing the inclusive growth index. In constructing the index, we first normalized the scales of the variables because they are of different scales. Further, we show the eigenvalues of the 13 components of inclusive growth in while highlighting the main components used in constructing the final index.

4.4.1. Presentation of robustness results

The results of the direct effect, as shown in , indicate that human capital development has a negative impact on inclusive growth, albeit statistically insignificant (see Column 2). Furthermore, the unconditional effect of all six governance dynamics on inclusive growth is negative and statistically significant, except for political stability.

Table 6. Unconditional Effects of human capital development and institutional quality on inclusive growth (Dependent variable: Inclusive growth index).

(See columns 2-7 of ). The indirect effect results in are consistent with the findings in . We find strong empirical and statistically significant evidence that all six governance dynamics further decrease human capital and affect inclusive growth in Africa. Lastly, all our covariates–economic globalization, investment, and vulnerable employment–have no impact on the inclusive growth index, except economic globalization, which positively influences on inclusive growth. Finally, all our post-estimation results are valid, as shown in . In summary, the robust results in and are consistent with those in and , and the findings of this study indicate that governance dynamics dampen/nullify the enhancing effect of human capital on inclusive growth in Africa. This result validates the reliability of our inferences.

Table 7. Conditional Effects of human capital development and institutional quality on inclusive growth (Dependent variable: Inclusive growth index).

4.5. Discussion of findings

In this section, we present and discuss the findings obtained from the two-step system GMM, which is consistent with using an alternative proxy for inclusive growth. First, our results indicate that human capital development in Africa promotes inclusive growth. A plausible reason for this is that innovation, entrepreneurial skills, education, health, knowledge capital, and financial development accrue to the pursuit of inclusive growth (Raheem et al., Citation2018; Oyinlola et al., Citation2021; Hanushek, Citation2016). These capacities effectively utilize the continent’s resources and (will) enable its citizenries to contribute to their countries’ inclusive growth trajectories. Indeed, a well-educated and skilled population is more likely to have a more competent and knowledgeable workforce, which is consistent with the premise of this study.

Additionally, investment in human capital equips the population with the necessary skills which increases overall economic output, and reduces income inequality. These unequivocally contribute to inclusive growth and social progress. Our findings are consistent with SDG Goal 4, highlighting the relevance of equitable quality education and inclusiveness. This implies that the significance of human capital for inclusive growth becomes apparent when African countries invest in average years of schooling and returns on education. These findings align with studies indicating that human capital is a critical determinant of shared growth (Adeniji et al., Citation2020; Oyinlola & Adedeji, Citation2022). Hence, this evidence validates hypothesis 1a.

Second, our findings reveal that all six governance indicators, including control of corruption, voice and accountability, regulatory quality, rule of law, political stability, and government effectiveness, significantly and negatively affect inclusive growth in African countries. This implies that poor governance practices and weak or ineffective institutional frameworks hinder inclusive growth (). Some plausible interpretations of these outcomes are mismanagement and limited government capacity, bureaucratic hurdles, administrative complexities, limited capacity, historical factors, and external interference. Furthermore, weak institutions are triggered by poor accountability and poor regulatory environment, which translates to reduced inclusive growth and low social progress. Theoretically, governance is believed to stimulate shared growth by ensuring robust institutional, political, economic, and property rights and freedom (Acemoglu et al., Citation2014).

However, our findings in African settings contradict previous contributions by Ofori et al. (Citation2022) and Ofori and Asongu (Citation2024). Thus, this finding invalidates Hypothesis 1b and is not consistent with SDG 16. The way forward requires addressing these factors, which often require comprehensive reforms, strong and transparent leadership, and a commitment to improving governance and institutional frameworks.

Third, the interactive effects of human capital with governance dimensions, including control of corruption, government effectiveness, voice and accountability, the rule of law, regulatory quality, and political stability, collectively exhibit a negative impact on inclusive growth. The total/net effect analysis reveals that when considering the mean values of these governance factors, human capital development has an adverse effect on inclusive growth in Africa. This indicates that weak governance, marked by lack of transparent and fair systems, impedes the efficient allocation of human resources, resulting in lower human capital and hindering inclusive growth. Additionally, there may be a mismatch between the skills possessed by the workforce and those demanded by the market. This is because weak institutions struggle to address this mismatch, resulting in unemployment or under-employment among educated individuals and limiting the overall impact of human capital on inclusive growth. Moreover, inadequate investments in education and healthcare triggered by weak governance impede human capital development, thereby hindering inclusive growth. Considering these findings, Hypothesis 2 is contradicted.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

This study investigates the conditional effect of human capital development on inclusive growth in Africa. Using macro data from 43 African countries spanning 2005-2020 and employing the two-step system GMM estimator, we assess inclusive growth by integrating GDP per capita and income inequality. Robustness checks were conducted by constructing an index using PCA. Subsequently, the following empirical findings were established. First, we found that human capital positively influences inclusive growth, whereas all governance indicators exert a dampening effect. Second, the study identified that the six governance dimensions–control of corruption, government effectiveness, rule of law, regulatory quality, political stability, and voice and accountability–completely nullify the positive impact of human capital on inclusive growth, with effects ranging from 0.0444 to 0.1060.

To foster inclusive growth in Africa, addressing weaknesses in governance and institutional structures architecture is paramount, as they not only hinder growth but also undermine the positive impact of human capital. The authors advocate for the promotion of academic financing strategies such as student loans, scholarships for vulnerable populations, award schemes, and other forms of financial assistance, as these have the potential to enhance human capital and increase school enrolment. Therefore, it is crucial for policymakers and governments to allocate more funding towards human capital development, as this would significantly contribute to the development of human capital, which in turn can drive shared growth. Furthermore, many African countries grapple with weak institutional and governance policies. The path forward involves directing resources towards enhancing regulatory efficiency, promoting political stability, and strengthening the rule of law.

This can create a conducive setting for attracting foreign and private investment, fostering entrepreneurship, facilitating ease of doing business, and promoting innovation activities essential for economic growth and inequality reduction. Policymakers should also prioritize enhancing good governance and institutional quality through anti-corruption measures, strengthening legal and judicial systems, and implementing robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. These collaborative efforts involving the private sector and international partners are crucial for addressing the root causes of weak institutions and governance, thereby fostering environment conducive environment necessary for inclusive growth in Africa. Human capital thrives on good governance and institutional quality, which are essential for shared growth. This aligns with the achievement of SDGs, particularly 4, 8, 10, and 16.

This future research direction is based on the premise that the panel evidence provided in this study is crucial for cross-country standard policy harmonization, a relevant time-series empirical strategies should guide more targeted or country-specific policies. Furthermore, this study’s methodology can be replicated at sub-regional levels, such as Southern Africa, Eastern Africa, West Africa, Central Africa, and Northern Africa, to provide policymakers at regional levels with insights into efforts that can be adopted to achieve shared prosperity and growth. Additionally, future research can explore the use of machine learning algorithms to address missing values in some African countries, as traditional techniques may lead to overfitting or underfitting when robust instruments are not available.

Finally, this study has a few limitations. Firstly, the study is restricted to African countries, thus comparisons among underdeveloped countries, middle-income, and high-income countries are not included in the analysis. Furthermore, it does not consider certain African countries such as South Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, and Seychelles due to numerous missing observations spanning over five years. However, with improved data availability, future studies can utilize the arguments adopted in this work to re-test the hypotheses. Lastly, a drawback of this study is that it does not explore the effect of primary, secondary, and tertiary enrolment on inclusive growth, as the enrolment levels in the region are generally low.

Authors’ contributions

P.E.O.: conceptualization, methodology, data analysis and writing initial draft; A.K.: Introduction, Interpretation, comments and suggestions; B.Q.: data collection, data curation, conclusion and policy implications. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscripts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pamela Efua Ofori

Pamela Efua Ofori is a PhD candidate in the Department of Economics at the University of Insubria, Italy. She holds a double master’s degree in Global Entrepreneurship Economics and Management and Innovation and Change from the same institution and the Friedrich Schiller University, Jena, respectively. The author’s research interests include sustainability, gender inclusion, development economics, the economics of innovation, and environmental economics. She earned his B.S.c in Mathematics with Economics from the University of Cape Coast in Ghana.

Ametus Kuuwill

Ametus Kuuwill is currently a Ph.D. student at the Technische Universität Dresden, Germany. He is a scholar of the European Erasmus Mundus Joint Master’s Program in Sustainable Tropical Forestry, holding a double master’s degree in Forests and Livelihoods from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and Tropical Forest Management from the Technische Universität Dresden, Germany. Ametus previously worked as a Research Assistant at the Department of Soil and Land-use Management of the United Nations University (UNU-FLORES), where he focused on carbon forestry and plantation management. Prior to this, he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in economics from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana, and served as a Teaching and Research Assistant. His research interests include livelihood, forest management and governance, environmental and natural resource management, agricultural economics, economic growth, and plantation forestry.

Bright Quaye

Bright Quaye is a Ph.D. Economics candidate at Washington University in St. Louis. He earned his Bachelor of Science in Mathematics with Economics from the University of Cape Coast in Ghana. He subsequently obtained a Master of Science in Mathematics from Montana State University. Bright's research interests focus on areas such as Monetary and Fiscal Policy, Macrofinance, and Development Economics.

Notes

1 See Table A2 in the Appendices for list of African countries considered for the study.

References

- Acemoglu, D. (2010). Growth and institutions. In Economic growth (pp. 107–115). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2012). What does human capital do? A review of Goldin and Katz’s The race between education and technology. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(2), 426–463. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.2.426

- Acemoglu, D., Gallego, F., & Robinson, J. A. (2014). Institutions, human capital and development. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Adeleye, B. N., Adedoyin, F., & Nathaniel, S. (2021). The criticality of ICT-trade nexus on economic and inclusive growth. Information Technology for Development, 27(2), 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2020.1840323

- Adeleye, B. N., Bengana, I., Boukhelkhal, A., Shafiq, M. M., & Abdulkareem, H. K. (2022). Does human capital tilt the population-economic growth dynamics? Evidence from Middle East and North African countries. Social Indicators Research, 162, 1–21.

- Adeniji, A., Osibanjo, A., Salau, O., Atolagbe, T., Ojebola, O., Osoko, A., Akindele, R., & Edewor, O. (2020). Leadership dimensions, employee engagement and job performance of selected consumer-packaged goods firms. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 7(1), 1801115. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2020.1801115

- Africa Union. (2015). Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want. Accessed via: https://au.int/en/agenda2063/overview. Accessed on September 28, 2023.

- Aghion, P., Boustan, L., Hoxby, C., & Vandenbussche, J. (2009). The causal impact of education on economic growth: Evidence from US. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1(1), 1–73.

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1990). A model of growth through creative destruction. Econometrica, 60(2), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.2307/2951599

- Ali, I., & Son, H. H. (2007). Measuring inclusive growth. Asian Development Review, 24(01), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0116110507000024

- Anand, R., Mishra, M. S., & Peiris, M. S. J. (2013). Inclusive growth: Measurement and determinants. International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781484323212.001

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

- Arrow, K. J. (1962). The economic implications of learning by doing. The Review of Economic Studies, 29(3), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.2307/2295952

- Asian Development Bank. (2013). Framework of inclusive growth indicators: Key indicators for Asia and the Pacific.

- Henri, P. A. O. (2019). Natural resources curse: A reality in Africa. Resources policy, 63,101406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.101406

- Becker, G. S. (1993). Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 101(3), 385–409. https://doi.org/10.1086/261880

- Benhabib, J., & Spiegel, M. M. (1994). The role of human capital in economic development evidence from the aggregate cross-country data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 34(2), 143–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(94)90047-7

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Boikos, S. (2016). Corruption, public expenditure and human capital accumulation. Review of Economic Analysis, 8(1), 17–45. https://doi.org/10.15353/rea.v8i1.1430

- Čadil, J., Petkovová, L., & Blatná, D. (2014). Human capital, economic structure and growth. Procedia Economics and Finance, 12, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(14)00323-2

- Calderón, C., & Servén, L. (2014). Infrastructure, growth, and inequality: An overview. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7034

- Canlas, D. B. (2016). Investing in human capital for inclusive growth: focus on higher education. PIDS Discussion Paper Series.

- Castelló‐Climent, A., & Doménech, R. (2008). Human capital inequality, life expectancy and economic growth. The Economic Journal, 118(528), 653–677. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02136.x

- Farayibi, A. O., & Folarin, O. (2021). Does government education expenditure affect educational outcomes? New evidence from Sub‐Saharan African countries. African Development Review, 33(3), 546–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12588

- Faundez, J. (2016). Douglass North’s theory of institutions: lessons for law and development. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, 8(2), 373–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-016-0028-8

- Fayissa, B., & Nsiah, C. (2013). The impact of governance on economic growth in Africa. The Journal of Developing Areas, 47(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2013.0009

- Feenstra, R. C., Inklaar, R., & Timmer, M. P. (2015). The next generation of the Penn World Table. American Economic Review, 105(10), 3150–3182. www.ggdc.net/pwt https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130954

- Fosu, A. K., & Abass, A. F. (2019). Domestic credit and export diversification: Africa from a global perspective. Journal of African Business, 20(2), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1582295

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. European Economic Review, 35(2-3), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(91)90153-A

- Gupta, S., Davoodi, H., & Alonso-Terme, R. (2002). Does corruption affect income inequality and poverty? Economics of Governance, 3(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s101010100039

- Hanushek, E. A. (2013). Economic growth in developing countries: The role of human capital. Economics of Education Review, 37, 204–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.04.005

- Hanushek, E. A. (2016). Will more higher education improve economic growth? Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 32(4), 538–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grw025

- Hanushek, E. A., Jamison, D. T., Jamison, E. A., & Woessmann, L. (2008). Education and economic growth: It is not just going to school but learning something while there that matters. Education Next, 8(2), 62–71.

- Hanushek, E. A., & Wößmann, L. (2007). The role of education quality for economic growth . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4122.

- Hauk, W. R., & Wacziarg, R. (2009). A Monte Carlo study of growth regressions. Journal of Economic Growth, 14(2), 103–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-009-9040-3

- IMF. (2021). Build forward better. IMF Annual Report 2021. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/2021/eng/spotlight/the-great-divergence/#:∼:text=COVID%2D19%20dealt%20low%2Dincome,prices%20remains%20a%20key%20priority.

- Islam, N. (1995). Growth empirics: a panel data approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(4), 1127–1170. https://doi.org/10.2307/2946651

- Ivanyna, M., & Salerno, A. (2021). Governance for inclusive growth.

- Kamah, M., Riti, J. S., & Bin, P. (2021). Inclusive growth and environmental sustainability: The role of institutional quality in sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 28(26), 34885–34901. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13125-z

- Lahoti, R., Jayadev, A., & Reddy, S. (2016). The global consumption and income project (GCIP): An overview. Journal of Globalization and Development, 7(1), 61–108. https://doi.org/10.1515/jgd-2016-0025

- Lucas, R. E. Jr, (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

- Lyakurwa, W. M. (2007). Human capital and technology for development: Lessons for Africa. African Development Bank-AfDB Annual Meetings Symposium Shanghai .

- Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118477

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A. (2015). Corruption: Good governance powers innovation. Nature, 518(7539), 295–297. https://doi.org/10.1038/518295a

- Ndikumana, L., & Boyce, J. K. (2011). Africa’s odious debts: How foreign loans and capital flight bled a continent. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Ofori, I. K., & Asongu, S. A. (2024). Repackaging FDI for inclusive growth: Nullifying effects and policy-relevant thresholds of governance. Transnational Corporations Review, 16(2), 200056.

- Ofori, I. K., & Asongu, S. A. (2021). ICT diffusion, foreign direct investment and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telematics and Informatics, 65, 101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2021.101718

- Ofori, I. K., Cantah, W. G., Afful, B., Jr, & Hossain, S. (2022). Towards shared prosperity in Sub‐Saharan Africa: How does the effect of economic integration compare to social equity policies? African Development Review, 34(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12614

- Ofori, I. K., & Figari, F. (2022). Economic globalization and inclusive green growth in Africa: Contingencies and policy‐relevant thresholds of governance. Sustainable Development.

- Ofori, P. E., & Grechyna, D. (2021). Remittances, natural resource rent and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1979305. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1979305

- Ogundari, K., & Awokuse, T. (2018). Human capital contribution to economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does health status matter more than education? Economic Analysis and Policy, 58, 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2018.02.001

- Oluwatobi, S., Ola-David, O., Olurinola, I., Alege, P., & Ogundipe, A. (2016). Human capital, institutions and innovation in sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 6(4), 1507–1514.

- Onifade, S. T., Ay, A., Asongu, S., & Bekun, F. V. (2020). Revisiting the trade and unemployment nexus: Empirical evidence from the Nigerian economy. Journal of Public Affairs, 20(3), e2053. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2053

- Oyinlola, M. A., & Adedeji, A. (2019). Human capital, financial sector development and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Change and Restructuring, 52(1), 43–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-017-9217-2

- Oyinlola, M. A., & Adedeji, A. A. (2022). Tax structure, human capital, and inclusive growth: A Sub‐Saharan Africa perspective. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(4), e2670. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.2670

- Oyinlola, M. A., Adedeji, A. A., & Onitekun, O. (2021). Human capital, innovation, and inclusive growth in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 72, 609–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2021.10.003

- Raheem, I. D., Isah, K. O., & Adedeji, A. A. (2018). Inclusive growth, human capital development and natural resource rent in AFRICA. Economic Change and Restructuring, 51(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-016-9193-y

- Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (2003). Measuring pro-poor growth. Economics Letters, 78(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(02)00205-7

- Rivera‐Batiz, F. L. (2002). Democracy, governance, and economic growth: Theory and evidence. Review of Development Economics, 6(2), 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9361.00151

- Rodrik, D. (1997). Democracy and economic performance. Harvard University, 14(1999), 707–738.

- Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037. https://doi.org/10.1086/261420

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 2), S71–S102. https://doi.org/10.1086/261725

- Sabir, S., & Qamar, M. (2019). Fiscal policy, institutions, and inclusive growth: Evidence from the developing Asian countries. International Journal of Social Economics, 46(6), 822–837. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-08-2018-0419

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1–17.

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884513

- Stephen, N. T., & Chukwuemeka, A. S. (2019). Challenges of human capital development in Sub Sahara Africa, a study of Nigeria Civil Service from 2011-2015. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 10(2), 90–102.

- UNDP. (2017). UNDP's strategy for inclusive and sustainable growth (New York USA).

- UNDP. (2021). Unsettled Lives: Shaping our Future in a Transforming World. Human Development Report, 2022

- WEF. (2017). The Global Human Capital Report 2017: Preparing people for the future of work. Retrieved March, 2021, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Human_Capital_Report_2017.pdf

- World Bank. (2020). Poverty and shared prosperity 2020: Reversals of fortune. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2021). World development indicators. Retrieved June 4, 2023, from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators

Appendix A

Table A1. Correlation matrix for variables used for the analysis.

Table A2. List of countries.