?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Despite numerous policies implemented in this respect, Ghana still needs to catch up in achieving the Sustainable Development Goal of ending poverty in all forms by 2030. One way to escape poverty for most people is access to a steady flow of sufficient income from employment. However, with limited paid employment opportunities in Ghana, as is the case for other developing countries, the question of engagement in self-employment as a means to escape poverty emerges. This study conducts a thorough empirical analysis to gauge if self-employment could be an effective tool for addressing poverty in Ghana and the types of self-employment that possess the potential as an antidote to poverty in Ghana. The study thus examines the effects of self-employment on poverty and the type(s) of self-employment that is worth pursuing using nationwide cross-sectional survey data. The study with the aid of a linear probability model finds that self-employment has a significant positive relationship with poverty. Self-employed persons are more likely to be poor relative to persons in paid employment. However, non-agriculture self-employment and opportunity entrepreneurs is a viable route out of poverty even for persons with less than desired levels of education and skills. The implications for poverty reduction are discussed.

Impact statement

This study examines the effect of self-employment on poverty and the type(s) of self-employment that is worth pursuing using nationwide cross-sectional survey data. The findings show that selfemployed persons are more likely to be poor relative to persons in paid employment. However, non-agriculture self-employment and opportunity entrepreneurs is a viable route out of poverty even for persons with less than desired levels of education and skills. The relevance of this study is that it throws more light on the significance of policies to be directed to eliminating hindrances and bottlenecks in setting up own businesses and making them more productive.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

The eradication of extreme poverty and hunger is on the front line among the numerous United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and an essential development objective of nations. Although all governments try to reduce or alleviate poverty in their respective countries, it is a herculean task for most developing and African countries. World Bank (Citation2018) estimates that 15% of the world’s people live in poverty and 10 percent in extreme poverty. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (Citation2019) also estimates that 8.6 percent of people in the world live on the less than $ 1.90-a-day poverty line, and the number of people who live in extreme poverty continues to rise in developing countries. More strikingly, two-thirds of the global indigent population resides in Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA), and a major reason for the slowdown in global extreme poverty reduction is the slow progress experienced in SSA (World Bank, Citation2020).

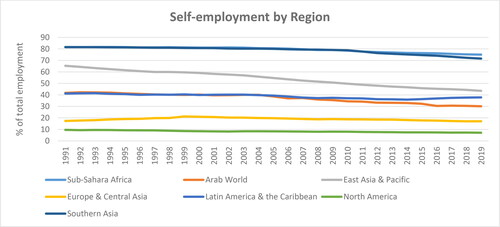

It has been argued that poverty is primarily a result of a lack of access to gainful employment and inadequate earning capacity, and hence a pivotal way to escape poverty is to earn more labour income (Fields, Citation2019; Rutkowski, Citation2015). In an attempt to overcome this challenge, many people resort to self-employment activities and operate in the informal economy. Fields (Citation2019) asserts that most of the world’s poor are self-employed, and due to the limited opportunities in most developing countries for employment to earn a decent wage, many are working hard but working poor. The evidence of high self-employment rates in developing economies is presented in , with South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa leading the charge in the global, regional distribution. This study investigates whether self-employment is associated with poverty reduction in Ghana.

Ghana, in particular, has implemented many poverty reduction strategies over the years to help reduce the impacts of poverty and extreme poverty in the country. Some of these poverty reduction strategies implemented over the past two decades include the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS I & II), the Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda (GSGDA), the National Social Protection Policy (NSPP), the Planting for Foods and Jobs (PFJ) Program, the National Entrepreneurship and Innovation Plan (NEIP) and the One District One Factory (1D1F) initiative. In addition, a number of social intervention programs have been implemented. These include the Livelihood Empowerment against Poverty (LEAP), the Capitation Grant, the School Feeding Program, eliminating schools under trees, and free senior high school education.

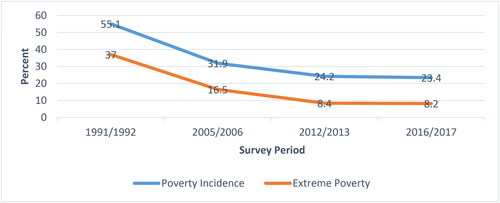

These poverty reduction strategies and interventions have led to a downward trend in the poverty incidence in Ghana in the past. However, the incidence has stagnated in recent years, as observed in the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) rounds, replicated in . Poverty incidence measures the proportion of the population that is poor, while extreme poverty incidence is defined as the state where the standard of living is insufficient to meet the basic nutritional requirements of the household even if they devote their entire consumption budget to food (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2018). The poverty incidence drastically declined by 23.2 percentage points between 1991/1992 and 2005/2006. There was also a significant decline of 7.7 percentage points between the surveys in 2005/2006 and 2012/2013. However, there was a marginal decline of 0.8 percentage points between the poverty incidence data in 2012/2013 and 2016/2017. Extreme poverty also witnessed a similar trend over the period. While extreme poverty decreased significantly by 20.5 percentage points between 1991/1992 and 2005/2006 and also declined by 8.1 percentage points between 2005/2006 and 2012/2013, it only fell marginally by 0.2 percentage points from 8.4% in 2012/2013 to 8.2% in 2016/2017. The most recent survey in 2016/2017 suggests that close to one-quarter of Ghana’s population (23.4 %) wallow in poverty. Compared to the 2012/2013 poverty incidence of 24.2%, it presupposes that poverty rates have remained pervasive in the past decade, and the poverty reduction strategies have not been effective, although the rise in population is a potential contributory factor.

In absolute terms, and due to population expansion, the population of Ghanaians in extreme poverty has increased from 2.2 million in 2013 to 2.4 million in 2017. Urgent steps are needed if Ghana is to be in line with achieving the SDG on ending poverty in all forms by 2030. Robust and sustainable economic empowerment is one of the surest ways to overcome poverty. However, it is worth noting that there is limited space in the formal sector to absorb most of the youthful labour force (Beegle & Christiaensen, Citation2019). Also, only 9 % of Ghanaians have post-secondary education, which is an essential requirement to secure a productive formal sector job (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2019). To reinforce this argument, Ackah (Citation2013) shows that households in Ghana headed by a person who has completed secondary education or higher gravitate more towards wage employment. In the absence of sufficient opportunities for wage employment, coupled with the high proportion of people who still need a post-secondary education, the obvious choice for most Ghanaians to be economically empowered is to engage in self-employment activities, mainly in the informal sector.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that records of the World Bank (Citation2020) show that 75% of Ghana’s labour force is self-employed. However, self-employment is associated mainly with low income levels and poor working conditions, perpetuating poverty and income inequality levels in developing countries (Oyenubi, Citation2019). That notwithstanding, since a large number of the labour force are self-employed in Ghana, it is of interest to empirically investigate the extent to which this engagement is associated with poverty reduction. It is also worth providing an empirical justification as to which types of employment activities contribute more to poverty reduction in Ghana. Thus, this study examines whether self-employment could be an antidote to poverty in Ghana and which type(s) of self-employment is worth promoting.

Further, this study conducts heterogeneous analysis to determine the differences in the effects of self-employment on poverty among various residential locations and educational attainments. To the best of our knowledge, after a thorough literature search and review, we found little evidence of a study that has investigated these issues in the Ghanaian context. Thus, this study fills a gap in the literature on the relationship between self-employment and poverty in Ghana.

Literature Review

Theoretical Review

No unified theory comprehensively espouses the linkage between self-employment and poverty. That notwithstanding, the theoretical foundation of this study is premised on the traditional economic choice theory, which explains why some people choose self-employment. Following the work of Yerrabati (Citation2023), it is assumed that workers entering the labour market are confronted with the option of wage employment or self-employment to avoid unemployment. While the dominant type of entrepreneurship in developed countries is opportunity entrepreneurs, developing countries have people being self-employed out of necessity and desperation due to the lack of wage employment opportunities and social safety nets. These groups of entrepreneurs are called necessity entrepreneurs. The expected utility of engaging in wage employment is a function of earnings, taste and preference, working conditions, and growth opportunities. The expected utility of self-employment is a function of the availability of wage employment, taste and preference, and social security benefits. It is worth noting that the expected utility of being unemployed is assumed to be zero. Rational economic agents will therefore choose the type of employment opportunity that gives them the highest consumption or income subject to the time, capability, and availability of the job in the labour market. Generally, wage employment is preferred in developing countries due to better income and working conditions, including provision for pensions and higher job security. However, not everyone can get wage employment, so self-employment is the following option to avoid unemployment. At the very least, this option is better than unemployment and helps reduce or alleviate household poverty. Thus, self-employment provides some form of income cushion against poverty.

Empirical Review

Drivers of self-employment

The extant literature is replete with two main reasons a person may be self-employed. While some identify a profitable business and work towards making it successful (opportunity entrepreneurs), others engage in self-employment as a means of survival due to the inability to secure a decent formal sector job or wage employment (necessity entrepreneurs). For example, Margolis (Citation2014) concludes that two-thirds of persons in self-employment in developing countries are individuals with no better work alternatives. Filmer and Fox (Citation2014) further assert that in the absence of an adequate social safety net, people are compelled to opt for informal sector self-employment and low-wage formal sector employment. In this same line of thought, Fields (Citation2019) argues that self-employment is vital to people experiencing poverty. While some prefer to be self-employed than be in wage employment, most poor people prefer wage employment as they consider self-employment worse. However, without adequate social protection programs and unemployment insurance schemes, self-employment is better than nothing. Thus, in a desperate attempt to overcome the challenges of lack of adequate employment opportunities, most people engage in self-employment activities.

In Ghana, the labour force is concentrated mainly in the informal sector or self-employment because of limited opportunities in the formal sector and the lack of opportunity for further formal education. Oyenubi (Citation2019) posits that the lack of access to post-secondary education is due to the inability to afford institutions of higher learning even after meeting the entry requirements. The report of the Ghana Statistical Service (Citation2019) shows that only 9% of Ghanaians have attained post-secondary school educational levels, while only 11.4% of the employed population have post-secondary school certification. The report further notes that many people have been pushed into the informal sector (72.8%–) because of the inability of the formal sector to generate jobs in the required numbers.

Entrepreneurship and poverty nexus

There are limited empirical papers on the subject of self-employment and poverty in Africa. That notwithstanding, an exposition of some relevant ones follows. Yerrabati (Citation2023) most recently examines the role self-employment plays in alleviating poverty in developing countries. Using a five-year average of 56 developing countries, including some African countries, from 1995 to 2019 and the system GMM technique, the study finds that self-employment reduces poverty in line with theoretical prediction but by a smaller magnitude. The control variables introduced in the model include growth, income inequality, education, government spending, aid, natural resource rent, gross capital formation, foreign direct investment, democracy, and remittances. Sall (Citation2022) explored the contemporary theories that explain the relationship between entrepreneurship and poverty reduction and the reasons for the failure of poverty reduction programs in Africa. Adopting a qualitative method, the findings show that entrepreneurial development must ensure that people experiencing poverty have access to capital and create a suitable enabling environment for entrepreneurs. A study by Ba et al. (Citation2021) examines the effects of non-farm employment on poverty reduction in Mauritania. They deployed data from the 2014 Permanent Survey on Household Living Conditions household survey and used probit, propensity score matching, and inverse probability weighting techniques. The findings show that there is a 5.9% lower probability of being poor if at least one member of the household participates in a non-farm activity than only in the agricultural sector. They controlled for household assets, gender, age, and education of the household head.

In Ghana, Oyenubi (Citation2019) examines the earnings gap between the self-employed and wage earners in urban areas. The results show that self-employed individuals enjoy a premium at the mean, driven mainly by those at the upper end of the self-employment earning distribution. However, at lower quantiles, self-employment attracts a penalty. They conclude that the self-employed in urban Ghana are generally better off when compared with wage employees of similar human capital at the upper quantiles. Hence, policy should focus on improving entrepreneurs at the lower quantiles. A previous study by Ackah (Citation2013) also examines the determinants of participation in non-farm activities and the impact of non-farm employment on household income in rural Ghana. The findings show that households headed by persons who have completed secondary school or higher gravitate more toward wage employment. The results further show that non-farm employment is essential for poverty alleviation in rural Ghana.

In terms of the drivers of poverty, Molini and Paci (Citation2015) identify structural transformation, increased skills of the labour force, and urbanization as the key drivers of poverty reduction in Ghana over the past decade. For structural transformation, there has been a shift in economic activity from agriculture to the services sector. The service sector has, in recent years, contributed the most to economic growth, and this is being led by ‘other activities,’ which include the financial sector, education, and health, among others. Another driver of poverty reduction is the building of a skilled workforce. A skilled workforce is built through years of quality education and the creation of skills relevant to the labour market. Households headed by a person with secondary or tertiary education are less likely to be poor than those headed by an uneducated person. The last of these poverty drivers is the location of a person’s residence. Relocating to a rapidly developing area, especially in the south, helps escape poverty.

Data and methods

Data

The data employed for the study is the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) wave seven (GLSS 7). This is the most recent round of the GLSSs. The GLSSs are national level surveys that collect data on economic, social, and demographic variables at the individual and household levels. The GLSS, conducted by the Ghana Statistical Service, Ghana’s official bureau of statistics and national data, is among the most comprehensive official household datasets and has nationwide coverage. The sampling frame includes persons living in private households but excludes the population in institutions such as hospitals, schools, and prisons. Enumeration Areas (EAs) are stratified into the ten regions.Footnote1 The GLSS 7 adopted a two-stage stratified random sampling design. At the first stage, 1000 EAs were selected, covering the ten regions, while at the second stage, households in these EAs were sampled proportionately. A nationally representative sample of 15,000 households was selected, out of which 14,009 households and over 55,000 individuals responded to the survey conducted between September 2016 and October 2017.

Methodology

Empirical modeling and estimation

We specify a model that explains the likelihood of poverty as follows:

(1)

(1)

where SE is a binary variable for self-employment, and X is a vector of explanatory variables. In keeping with the definition of self-employment, the variable SE includes both those who are self-employed (primary owner of the business) and those who are contributing family workers. SE in (1) is replaced by AGSE in (2) to investigate the relationship between the economic sector within which self-employment occurs (i.e., self-employment in agriculture and self-employment in the non-agricultural sector) on poverty. In (3), SE is replaced with SENOCF to observe the vulnerability or otherwise of contributing family workers to poverty. In other words, in (3), we decouple contributing family workers from the actual owners of the business establishment in which they are employed. EquationEquation (4)

(4)

(4) differentiates owners of business establishments by the presence or absence of employees; thus self-employed (excluding contributing family workers) with employees and self-employed without employees. EquationEquations (2) (3)

(3)

(3) and Equation(4)

(4)

(4) are represented as follows:

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

EquationEquations (1)–(3) are estimated using linear probability estimations controlling for region-fixed effects to account for regional heterogeneities. Despite the popularity of the traditional logit or probit estimation for binary response variables or multinomial logit for categorical response variables, there is bias associated with using them in the presence of fixed effects (Greene, Citation2002). Thus, following Adjei-Mantey et al. (Citation2023) and Bellemare et al. (Citation2015), the linear probability model (LPM) is preferred to estimate EquationEquations (1)–(3). The resulting coefficients from this estimation technique represent changes in probability without the need for any post-estimation transformation. As further analysis, we conduct heterogeneous analysis on the basis of the residential location of the respondent, i.e., rural or urban, as well as on the basis of education, to observe potential heterogeneous effects across the locations and different levels of educational attainment. We acknowledge the possibility of confoundedness in the self-employment variables resulting from unobservable factors in its determination. That is, there could be factors that potentially cloud the actual effect of self-employment on poverty but are unobservable from the available data, and hence we cannot account for them. Considering the difficulty in securing an excellent instrument to account for this possibility, the results of our estimations best explain the associations between self-employment and poverty.

Results

This section presents the descriptive properties of the data, followed by the estimation results. details the summary statistics of the data.

Table 1. Summary statistics.

Household poverty status is measured as a binary variable that takes on the value of 1 if the individual lives in a poor household and 0 otherwise and is based on daily subsistence. Poor households are those households that fall below the upper poverty line of Ghȼ1760 per adult equivalent per year.Footnote2 (Ghana Statistical Service, Citation2018). The upper poverty line represents the amount needed for essential food and non-food consumption. Therefore, households that lie above the upper poverty line are considered non-poor, able to meet basic nutrition and essential non-food needs. Nearly a third of the sample (30.4%) are poor. This study characterizes four different groups of self-employed people and their counterfactuals. First, we consider the case of the self-employed (including contributing family workers) versus paid employees. Second, we consider the sector of self-employment. Thus, we have self-employed in agriculture, self-employed in non-agriculture, versus paid employees. Third, we decouple contributing family workers from the self-employed group so that we self-employed who are owners of the establishment, contributing family workers versus paid employees. Lastly, we consider the case of the self-employed (excluding contributing family workers) with employees, self-employed (excluding contributing family workers) without employees versus those in paid employed. In the case of the first categorization, we find that an overwhelming 88.7% of the sample are self-employed.Footnote3 Concerning the self-employment sector, we find that 69.3% are self-employed in agriculture, while 19.3% are self-employed in the non-agricultural sector. The self-employed in agriculture are typically farmers working on their own farms or persons working on family farms. Upon decoupling contributing family workers from the self-employed category, it is observed that 28.2% of the sample are self-employed who are heads or owners of their businesses while 60.5% are contributing family workers. When categorized according to whether or not the self-employed have at least one employee, 4.5% of the sample are self-employed with employees, with 66% being self-employed without employees. In this classification, contributing family workers are not included. This is to allow us compare people who set up business to employ themselves with those engaged in paid employment in terms of their associations with poverty. We find that only a fifth of the sample (19.7%) have at least a secondary school education, with the majority (79%) being educated up to junior high or middle school. The average household size was six, and the sample was close to even in terms of gender with 60% residing in rural locations.

displays the LPM results for predictors of poverty. Column (1) presents the results for the first categorization of self-employment (i.e., self-employed including contributing family workers or otherwise), column (2) shows the results for the sector of self-employment activity (i.e., self-employment in agriculture and self-employment in non-agriculture), column (3) shows results for the third categorization (i.e., decoupling contributing family workers from self-employment). In all estimations, the reference category is paid employees (or wage employment; including paid apprentices) while column (4) presents the results of self-employment type differentiated by whether or not the respondent has employees. Our findings show that self-employment has a positive and significant relationship with poverty. Being self-employed increases the probability of being poor by 2.8% relative to paid employees. Concerning the self-employment sector, we find that while those who are self-employed in agriculture have a positive and significant association with poverty, those who are self-employed in non-agricultural sectors have a negative and significant association with poverty. In other words, being in the agricultural sector is positively associated with poverty. This group of self-employed persons has a 4.7% higher likelihood of being poor than those in paid employment. This indicates the bad and largely subsistence-level conditions under which farmers generally operate in Ghana. Despite the recent increase in growth in medium-scale farm sizes, small-scale farms dominate in Ghana (Jayne et al., Citation2016). Many farmers, therefore, farm on small land sizes and cultivate on a subsistence level. In addition, other factors, such as the absence of storage facilities and processing activities, mean that even when these farmers make a bumper harvest, they are forced to sell at lower prices or risk post-harvest losses (Dinye & Ayitio, Citation2013; Yankson et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the absence of irrigation facilities, particularly in the dry seasons, means small-scale farmers or subsistence farmers may be unable to farm all year round, contributing to their positive association with poverty. As a result, their economic activity is not able to push them out of poverty. On the contrary, we found that persons who are self-employed in non-agricultural sectors have a 1.8% lower likelihood of being poor and consistent with the works of Ba et al. (Citation2021), Molini and Paci (Citation2015), and Ackah (Citation2013). This is not unexpected since if one is engaged in commerce or the trade of consumer goods, for instance, they could be in business all year round without having to deal with the effect of seasons on their work, as is the case for those engaged in agriculture. Furthermore, self-employed persons especially in non-agricultural sectors have greater control over their businesses and hence can work beyond usual working hours to increase their earnings. These results imply that the positive association observed between self-employment and poverty is largely driven by those who are self-employed in the agricultural sector. The results also point to the fact that the in the absence of paid employment (or wage employment), engaging in non-agricultural self-employment is a better alternative to escaping poverty.

Table 2. LPM estimates for determinants of poverty.

Further analyses of the data show that even though self employed persons are more vulnerable to poverty compared to paid employees, contributing family workers are at an even greater vulnerability level compared to owners of the self-employment establishments. It is seen from columns (3) and (4) that relative to paid employees, owners of self-employment establishments are 2.1% more likely to be poor while contributing family workers are 3.3% more likely to be poor. This implies that paid employees are associated with a 2.1% less likelihood of being poor relative to owners of self-employment establishments but contributing family workers are about 1.1% more likely to be poor relative to owners of self-employment establishments. Thus, overall, being a contributing family worker is worse than setting oneself up in their own self-employment endeavour.

Self-employment with employees is associated with a 4.4% lower likelihood of being poor relative to paid employees. In comparison, the self-employed without employees are associated with a 5.1% higher likelihood of being poor relative to paid employees. The self-employed employees likely have larger businesses for which they are able to employ other persons. This suggests that their businesses are beyond the subsistence level. These are those referred to as opportunity entrepreneurs. They are likely engaged in businesses with higher turnover and, thus, are less likely to be poor. On the other hand, those without employees are likely engaged in micro or small-sized businesses. These businesses are likely not large enough and may not be at the level where they make huge profits. Some may be barely generating enough for subsistence alone. Perhaps, these are engaged in self-employment as a means to escape poverty having not found paid jobs. For these reasons, their likelihood of being poor is greater than those who have paid employment. This is consistent with the findings of Oyenubi (Citation2019) that those self-employed at the upper end of the earnings distribution are usually better off. Thus, the concepts of opportunity entrepreneurs and necessity entrepreneurs are evident in these findings. Therefore, opportunity entrepreneurs will have a much lower likelihood of being poor compared to necessity entrepreneurs, who often engage in self-employment as an escape route out of poverty and are satisfied to make enough to get by daily.

Regarding other covariates, it was observed that persons with at least a secondary school education have between 8.1% –11.6% lower likelihood of being poor relative to persons with no education, and this agrees with previous literature (Adusah-Poku et al., Citation2021; Twerefou et al., Citation2014). Higher education gives people better economic opportunities who then are more likely to escape poverty. An increase in the household size by one member increases the likelihood of being poor by 2.4%. Larger household sizes imply more mouths to feed. Household consumption expenditure increases both for food and other non-food essentials such as utilities, clothing, and health care, among others. (Adjei-Mantey et al., Citation2022). This increases the burden for the household as a whole and, thus, makes them more likely to be poor. It was found that rural dwellers have a positive association with poverty, while females are less likely to be poor than males. Rural areas lack good infrastructure that aids economic activities and fewer economic opportunities. As a result, rural dwellers have fewer chances to escape poverty compared with urban dwellers who benefit from good infrastructure and better economic opportunities. The findings are in tandem with Adjasi and Osei (Citation2007). Females having a lower likelihood of poverty contrasts studies including Adusah-Poku et al. (Citation2023), Osei-Amponsah et al. (Citation2010), and Adjasi and Osei (Citation2007), most of which argue that females control fewer resources within the household and consequently have a higher likelihood of being poor. However, our finding agrees with Awuni et al. (Citation2023), who found that male-headed households in Ghana are more vulnerable to poverty. It is more common in Ghana for females to engage in petty trading activities (small corner shops, hawking goods, and tabletop consumer goods trading) to survive and escape poverty than their male counterparts, perhaps contributing to this finding.

Next, we conduct an analysis for heterogeneous effects to observe differences in the effects of self-employment on poverty among various residential locations. The findings are presented in . It is observed that the effect of self-employment on poverty while maintaining the direction of association, differs in magnitude and strength between urban and rural residents. There is a positive association between self-employment and poverty in rural areas at 1% level of significance, whereas, in urban areas, the relationship, though positive, is only mildly significant at 10%. Rural areas are the areas most noted for agricultural activities and it appears the dominance of agriculture is driving the strong effect of self-employment in rural areas. Urban areas generally have more opportunities for paid employment and better-paying jobs. Thus, most people are more likely to be engaged in such jobs. Those who end up without jobs in the urban areas are forced to go into self-employment to survive, which contributes to the positive association with poverty in urban areas. Rural areas, on the other hand, are characterized by few economic opportunities, and thus, with the many poor people, engagement in self-employment is potentially a measure to escape poverty. Results from (3) and (4) show that self-employment in agriculture in rural areas is associated with a higher likelihood of being poor compared to self-employment in agriculture in urban areas while there is no statistical difference in self-employment in non-agricultural sectors across both locations. This is evidence of the mostly small-scale nature of agriculture in rural areas; lacking modernization and large-scale commercialization in some areas. In the case of self-employment with or without employees, similar associations are observed for both locations; negative associations for those with employees and positive associations for those without employees. As previously explained, the self-employed without employees are likely the poor who engage in some form of business to be able to fend for themselves (Fields, Citation2019). These businesses are often at the micro or small level, with little resources or capacity to employ others; and often termed the opportunity entrepreneurs. However, if the business is big enough to employ others, then it is likely to generate sufficient turnover, and owners of such businesses are less likely to be poor, often termed as opportunity entrepreneurs.

Table 3. Heterogenous effects by location.

Next, we perform a heterogenous effect analysis based on education to observe how the effects differ for groups differentiated by their educational attainment. The results are displayed in . The key points of note are the effects of non-agriculture self-employed and self-employed employees. In the case of non-agriculture self-employed, persons with lower educational levels (up to basic education) who are engaged in non-agriculture self-employed are less likely to be poor relative to their counterparts in terms of educational attainment but who are in paid employment. In other words, for persons with lower levels of education, being engaged in self-employment in the agricultural sector is associated with lower likelihood of being poor compared to being in paid employment. For persons with lower levels of education, their skills are likely low and therefore not likely to attract high salaries in paid employment. For such persons, engaging in non-agriculture self-employment might prove useful in reducing poverty. For those who have attained higher education, there is no statistical difference between being in paid employment and engaging even in non-agriculture self-employment. Persons with higher education are likely more skilled and thus are able to secure jobs in the public sector or jobs in the private sector that require highly skilled workers generally. These jobs in paid employment tend to attract higher salaries. Therefore, engagement even in non-agriculture self-employment would likely fetch them no different incomes on average compared to being in paid employment. Similarly, it is observed that self-employment with employees has a lower association with poverty compared with paid employment for persons with lower levels of education while being statistically insignificant for persons with higher levels of education. Besides these, other categories of self-employed persons tend to display positive associations with poverty relative to their counterparts in paid employment. These findings have implications for poverty reduction in Ghana, given that the majority of the sample (nearly 80%) have lower levels of educational attainment. Targeting persons in this category and providing support to enter self-employment, especially in the non-agricultural sectors, might be crucial to meeting poverty alleviation targets. A further implication is that agriculture in Ghana needs modernization and improved conditions in order for those who engage in agricultural self-employment to improve their poverty status.

Table 4. Heterogeneous effects by education.

Conclusion

Ghana needs to catch up in achieving the SDG of ending poverty in all forms by 2030. Although many poverty strategies and social interventions have been implemented to address this menace, at least one-quarter of Ghanaians remain in poverty, with absolute figures above 2.4 million people. Given that 75% of Ghana’s labour force is self-employed, it is worth conducting a thorough empirical analysis to gauge if self-employment could be an antidote to poverty in Ghana. Thus, the study examines the effects of self-employment on poverty and the type(s) of self-employment worth pursuing. The study also examines the heterogeneous effects of self-employment on poverty using clusters of residential location and educational attainment. The study employs nationwide cross-sectional data to investigate the relationships and finds that self-employment tends to be positively associated with poverty relative to paid employment. Self-employed persons are more likely to be poor compared to persons in paid employment.

Further analyses show that self-employment in non-agricultural sectors helps reduce poverty, while the self-employed who have employees have a greater negative association with poverty. Heterogeneous analyses on the basis of education show that persons with lower levels of education stand to benefit more from engaging in non-agriculture self-employment and self-employment with employees as these make them less likely to be poor compared with counterparts of similarly low educational level who are in paid employment since their low levels of education precluded them from better opportunities for better-paying wage employment mainly in the public sector. Thus, engaging in self-employment is a viable route to escaping poverty for those people. Consequently, policymakers need to ensure that the returns to self-employment are boosted to effectively create livelihood opportunities for poor people or take them out of poverty. Policies should be implemented to eliminate hindrances and bottlenecks in setting up own businesses. Furthermore, support in the form of education and training as well as financial support not only to own businesses but, more importantly, to grow them to the point where they are large enough to employ others are crucial as that would have even greater returns in respect of reducing poverty in Ghana. These policies should be targeted particularly, towards persons with lower levels of education whose opportunities for other forms of employment are limited without completely neglecting persons with higher education who may want to engage in self-employment as opportunity entrepreneurs. Our study is limited by the inability to make causal claims due to limited data. However, this does not mask the implications of the significant relationships observed in this study. A future study that accounts for this limitation would further move the frontier of knowledge on this subject.

Authors’ contribution

Kunawotor M.E. conceptualized and designed the work, drafted the introduction and literature review and revised it for intellectual content. Adjei-Mantey K. conducted the analysis and discussion of the data and also revised it for intellectual content. Both authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kwame Adjei-Mantey

Kwame Adjei-Mantey is researcher at the Department of Applied Economics, University of Environment and Sustainable Development, Somanya, Ghana. His research interests are in the areas of energy and environmental economics, development economics and behavioral economics.

Mark Edem Kunawotor

Mark Edem Kunawotor is a Lecturer at the Department of Banking and Finance, University of Professional Studies, Accra. He is also a Research Associate and consults for Think Tanks and Civil Society Organizations. His research interests are in the areas of development and environmental economics particularly, poverty, income inequality, climate change and entrepreneurship.

Notes

1 In 2019, there was a re-demarcation of previous boundaries to create new regions bringing the total number of administrative regions in Ghana to 16. In this study, however, the regional effects are done using the country’s ten regions at the time of the survey.

2 The average exchange rate was US$1: Ghȼ4.4 in 2017, when the data was collected.

3 Notably, a large proportion of the sample fall under contributing family workers who have been classified as self-employed this case. We decouple them from the heads/owners of the family business to which they contributed in the third classification.

References

- Ackah, C. (2013). Non-farm employment and incomes in Rural Ghana. Journal of International Development, 25(3), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1846

- Adjasi, C. K., & Osei, K. A. (2007). Poverty profile and correlates of poverty in Ghana. International Journal of Social Economics, 34(7), 449–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290710760236

- Adjei‐Mantey, K., Awuku, M. O., & Kodom, R. V. (2023). Revisiting the determinants of food security: Does regular remittance inflow play a role in Ghanaian households? A disaggregated analysis. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 15(6), 1132–1146. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12610

- Adjei-Mantey, K., Kwakwa, P. A., & Adusah-Poku, F. (2022). Unraveling the effect of gender dimensions and wood fuel usage on household food security: evidence from Ghana. Heliyon, 8(11), e11268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11268

- Adusah-Poku, F., Adams, S., & Adjei-Mantey, K. (2023). Does the gender of the household head affect household energy choice in Ghana? An empirical analysis. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(7), 6049–6070. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02293-8

- Adusah‐Poku, F., Adjei‐Mantey, K., & Kwakwa, P. A. (2021). Are energy‐poor households also poor? Evidence from Ghana. Poverty & Public Policy, 13(1), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/pop4.301

- Awuni, E. T., Malerba, D., & Never, B. (2023). Understanding vulnerability to poverty, COVID-19’s effects, and implications for social protection: Insights from Ghana. Progress in Development Studies, 23(3), 246–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/14649934231162463

- Ba, M., Anwar, A., & Mughal, M. (2021). Non-farm employment and poverty reduction in Mauritania. Journal of International Development, 33(3), 490–514. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3533

- Beegle, K., & Christiaensen, L. (2019). Accelerating poverty reduction in Africa. The World Bank Group.,

- Bellemare, M. F., Novak, L., & Steinmetz, T. L. (2015). All in the family: Explaining the persistence of female genital cutting in West Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 116, 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.06.001

- Dinye, R. D., & Ayitio, J. (2013). Irrigated agricultural production and poverty reduction in Northern Ghana: A case study of the Tono Irrigation Scheme in the Kassena Nankana District. International Journal of Water Resources and Environmental Engineering, 5(2), 119–133.

- Fields, G. S. (2019). Self-employment and poverty in developing countries. IZA. World of Labour.

- Filmer, D., & Fox, L. (2014). Youth employment in sub-Saharan Africa. World Bank Publications.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2018). Poverty trends in Ghana, 2005 – 2017. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 7.

- Ghana Statistical Service. (2019). Main Report of the Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 7.

- Greene, W. (2002). The bias of the fixed effects estimator in nonlinear models. Working paper. New York University.

- Jayne, T. S., Chamberlin, J., Traub, L., Sitko, N., Muyanga, M., Yeboah, F. K., Anseeuw, W., Chapoto, A., Wineman, A., Nkonde, C., & Kachule, R. (2016). Africa’s changing farm size distribution patterns: The rise of medium‐scale farms. Agricultural Economics, 47(S1), 197–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/agec.12308

- Margolis, D. N. (2014). By choice and by necessity: Entrepreneurship and self-employment in the developing world. European Journal of Development Research, 26(4), 419–436.

- Molini, V., & Paci, P. (2015). Poverty reduction in Ghana: Progress and challenges. World Bank, Washington, DC. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/22732

- Osei-Amponsah, C., Anaman, K. A., & Sarpong, D. B. (2010). Marital status and household size as determinants of poverty among fishmongers in Tema, Ghana. In Pearlman (Ed.), Marriage: Roles, Stability and Conflict. Nova Science Publishers, Inc. pp. 173–187.

- Oyenubi, A. (2019). Who benefits from being self-employed in urban Ghana?. Economic Research South Africa (ERSA) working paper 779.

- Rutkowski, J. J. (2015). Employment and Poverty in the Philippines. World Bank.

- Sall, M. A. (2022). Entrepreneurship and Poverty Alleviation in Africa. Industrial Policy.

- Twerefou, D. K., Senadza, B., & Owusu-Afriyie, J. (2014). Determinants of poverty among male-headed and female-headed households in Ghana. Ghanaian Journal of Economics, 2(1), 77–96.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2019). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2018. United Nations.

- World Bank. (2018). Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle, the World Bank Group.

- World Bank. (2020). Self-employed, total (% of total employment) (modeled ILO estimate), available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.SELF.ZS.

- Yankson, P. W., Owusu, A. B., & Frimpong, S. (2016). Challenges and strategies for improving the agricultural marketing environment in developing countries: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Agricultural & Food Information, 17(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496505.2015.1110030

- Yerrabati, S. (2023). Self-employment: A means to reduce poverty in developing countries? Journal of Economic Studies, 50(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-08-2021-0411