?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The agricultural sector has experienced increased haphazard policy interventions and has been exposed to different policy uncertainties. However, relatively little empirical research has been done on how economic policy uncertainties (EPU) affect agricultural exports. Thus, this paper explores the effects of trade and economic policy uncertainties on agriculture exports. It also assesses trade agreements’ mediation function and logistics performance in the EPU-agricultural export relationship. The Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) method is employed to apply the structural gravity specification using data for 60 high-income and emerging economies from 2007-2018. The findings disclose that policy uncertainties adversely impact agricultural exports. The impacts of EPU remain qualitatively indistinguishable from those of a high-income or an emerging economy. However, emerging economies suffer more severe trade policy uncertainty impacts on agriculture exports than high-income countries. The results further prove that strong logistics and trade agreements mitigate policy uncertainty’s effect on agriculture exports. Besides, the results demonstrate that policy actions to improve EPU to the mean value of the sample result in a 2.6% reduction in tariff. Policymakers should take swift and decisive actions to reduce uncertainties and promote agriculture exports. Additionally, this study calls for improving trade agreements and logistics infrastructure to promote agricultural exports.

Impact statement

The agricultural sector has faced unpredictable policy uncertainties. Therefore, this study examines the effects of trade and economic policy uncertainties on agricultural exports, considering the role of trade agreements and the logistics performance of the countries. The study utilizes data from 60 agricultural goods exporting and 60 destination countries. The PPML model is utilized to exercise the structural gravity model to find the outcomes.

Findings implied that economic policy uncertainty negatively affect agricultural exports, with emerging economies suffering more than high-income ones. However, better logistics performance and trade agreements can mitigate the negative impacts of uncertainties on agricultural exports. Besides, the results highlight that the higher the GDP per capita in the exporting country, the weaker the negative effects of EPU on agriculture export. Moreover, the results show that emerging economies have far more severe agricultural export losses from TPU shock than high-income countries.

The significance of this research work lies in its practical implications and policy frameworks to elucidate the complex link between policy dynamics and agricultural export, enabling governments and policymakers to develop more resilient and adaptive policies to mitigate the adverse effects of trade and economic policy uncertainties. Besides, the findings of the study contribute to strategic decision-making for agricultural producers and exporters during high policy uncertainties.

1. Introduction

The economic policy uncertainty (hereafter EPU) refers to the doubt about the direction that trade, fiscal, monetary, and regulatory policies may take in the future. As a result, because of its volatility, it reflects changes in the economy (Baker et al., Citation2016). Throughout the past 20 years, the global economy has seen several policy uncertainty and volatility. For instance, global trade disputes involving the United States and China (Chong & Li, Citation2019), the US trade protection move (Robinson & Thierfelder, Citation2018), its withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) concurrence, the new trade agreement exchange of views focusing on trade policies, including renegotiating existing trade agreements (Robinson & Thierfelder, Citation2019), the agricultural export ban in some countries following the commodity price spikes in 2007-08 and 2010-11 (Deuss, Citation2017), the United Kingdom’s European Union (EU) referendum and exit, sanctions imposed on Russia as a result of the actions it took in Ukraine (Gould-Davies, Citation2018), regulations and trade in Europe, economic and financial crises, and the World Trade Organization’s (WTO’s) Appellate Body (AP) decrease and blocking new appointments (Bekkers, Citation2019).

The adverse impact of uncertainty on economic activities is prevalent in economic policies and academic literature (Bonciani & van Roye, Citation2015). Issues about uncertainty have extended worldwide since the financial crisis (Ahir et al., Citation2021). Increases in uncertainty generally tend to make economic agents more careful, and subsequently, agents are inclined to delay their production, investment, and consumption decisions (Benigno et al., Citation2020).

Based on this notion, some empirical studies have been conducted on the effects of uncertainties on trade flow (Borojo et al., Citation2021; Hu & Liu, Citation2021; Zhao, Citation2022; Jia et al., Citation2020; Constantinescu et al., Citation2020; Greenland et al., Citation2019), its effects on the economic performance of countries (Borojo et al., Citation2023; Yan et al., Citation2022). Besides, studies by Deuss (Citation2017) and Wen et al. (Citation2021) investigated the role of EPU on market price, and Gholipour (Citation2019) revealed the role of EPU on fixed investment.

However, research addressing how policy uncertainties influence agricultural export performance is relatively scarce. This is particularly noteworthy given the heightened volatility in the export performance of agricultural commodities in response to the shocks. The effects of uncertainty on agricultural trade performance are not confined merely to the trade volume; they also can adversely impact the likelihood of engaging in agricultural trade. Essentially, from an expectations viewpoint, the uncertainty might reduce the extensive margins (i.e., the likelihood of agricultural trade) by shaping the expectations of firms. Furthermore, this uncertainty tends to foster pessimistic outlooks among entrepreneurs regarding the future market demand from their trading partners (Nguyen, Citation2012).

Therefore, although the problem has become particularly prominent, empirical studies on the relationship between EPU and trade, mainly agriculture exports, are few. Thus, the fact that agricultural exports are subject to several kinds of policy uncertainties and the effects of policy uncertainty on trade performance between countries continue to be important theoretical and empirical research questions.

Therefore, this research aims to address this gap by examining the effects of EPU on agricultural exports. It focuses on the effects of EPU on agricultural exports for the following reasons. First, the share of agriculture in global trade has consistently increased in the last 20 years (Chaturvedi, Citation2018). Nonetheless, compared to other sectors, it has experienced the greatest number of disorganized policy interventions (Anderson, Citation2016). More precisely, there have been several policy changes and uncertainty regarding agricultural exports. For instance, the collapse of the Doha Round implies that international collaboration in trade and development has failed (Bouët & Laborde, Citation2008). The decline in international demand for exports of agricultural products from the United States in the wake of tariff increases imposed by the Trump Administration on US imports from China, China’s tariffs on US exports in retaliation, especially agriculture goods, to China and the resulting substantial diversions of trade. Thus, the agricultural sector is heavily influenced by fluctuations in economic and trade policies, which can profoundly impact production, prices, and market access for agricultural goods.

Second, erroneous trade policies that attempted to address local problems in different years were subject to a high global agricultural commodity price due to increased price volatility. Moreover, export restrictions and food security reserve measures were brought due to increased agricultural commodity prices in 2010–2011 and 2012–2013 (Díaz-Bonilla et al., Citation2017). Third, some initiatives to enhance export taxes and minimize import charges caused and sustained initial shocks and uncertainties to the worldwide flow of agricultural commodities (Díaz-Bonilla et al., Citation2017). Likewise, agricultural policy actions often clash with other macroeconomic policy targets, resulting in high uncertainties. Furthermore, policymakers are frequently tempted to introduce policy reversals in the agricultural sector when a country’s overall macroeconomic situation is precarious, using the sector to pursue other goals like generating foreign exchange or controlling inflation (Mueller & Mueller, Citation2016).

Fourth, a growing amount of regulation was applied to the agricultural value chain, mostly in price ceilings and export quotas for specific commodities (Lema et al., Citation2018). Besides, regulations include export levies, bans, and the selective application of advantageous import tariffs common in agricultural commodity exports (Gilmour et al., Citation2012). Finally, agricultural exports often play a significant role in the economies of many countries, contributing to employment, income generation, and overall economic growth.

Therefore, this research addresses the following questions in light of this background. First, what are the roles of EPU on agricultural export performance? Second, how does the logistics performance affect the role of EPU on agricultural export? Finally, how do differences in economic size impact the EPU-agricultural export nexus? Based on these research questions, this study intends to bring new insights into the roles of EPU on agricultural export performance.

Therefore, the major purpose of this paper is to examine the impacts of policy uncertainty on agriculture exports using structural gravity model. Furthermore, the computations continue according to the income diversity of the countries in the sample, which are classified as emerging and high-income economies. Additionally, consideration has been given to the policy actions’ intermediary function in the EPU-agricultural export connection concerning trade agreements and logistical performance. Our results provide evidence that policy uncertainties have a significant detrimental impact on agricultural exports. The results further imply that a high policy uncertainty effect on agricultural exports can be mediated by improving logistics performance and promoting trade agreements. Therefore, the practical importance of this study lies at the intersection of these results because any policy actions ought to be carefully assessed and organized to reduce the impact of policy uncertainty on agricultural exports.

This study has several contributions to the literature. First, it is the first in its kind to analyze the impacts of policy uncertainty on agriculture exports, which is a somewhat understudied topic. Secondly, it extended the examination categorizing countries in income heterogeneity (developed and emerging) to investigate how the focal effect of policy uncertainty on agriculture export varies.

Third, it has considered the mediating function of the trade agreements, trade and transport logistics performance in the relationship between uncertainty and agriculture export. Thus, it considers how improving logistics performance and having trade agreements mediate policy uncertainty and the country’s agriculture exports. Fourth, it has been examined the marginal impact of EPU on exporting nations’ GDP per capita. Lastly, for policy purposes, a simulation analysis (counterfactual analysis) was carried out to investigate the tariff equivalency of enhancement in policy uncertainty inside the country where the average policy uncertainty functions within the representative sample.

The remaining sections of this paper are arranged as follows: The second part discusses the literature review. The third part describes the study’s methodology and data. The fourth part reveals the findings and results. The fifth part presents discussions and implications for policy.

2. Review of the literature

2.1. Economic policy uncertainty and agricultural export

Theoretical literature suggests that trade and economic policy uncertainty detrimentally impact countries’ trade performance. For instance, according to the real option value theory posited by Bernanke (Citation1983), policy ambiguity engenders a waiting option, wherein firms opt to delay export decisions if the export value is not substantially higher than the holding option’s value. Conversely, heightened policy uncertainty augments the value of future investment options, leading to delays in investment decisions, a viewpoint supported by Krol (2018), and Novy and Taylor (Citation2020). They presented evidence showing that companies involved in exporting tend to reduce investments in established markets and defer entering new ones during periods of elevated policy uncertainties. Consequently, for firms, uncertainties regarding future pricing and consumer demand may act as obstacles to entry, constraining the expansion of trade boundaries. This phenomenon results in exporting firms reducing investments in existing markets and postponing entry into new ones during periods of high policy uncertainties, posing entry barriers and constraining trade expansion.

Moreover, aligned with real options theory, the framework proposed by Handley (Citation2014) suggests that escalating policy uncertainties prompt firms to defer market entry to avoid incurring sunk costs. Consequently, these theories portray policy uncertainty as a significant adverse factor influencing economic activity and trade dynamics, in line with Scheffel’s (2016).

On the contrary, some theoretical works argue for a positive association between policy uncertainty and trade performance. For instance, the classical Qi-Hartman-Abel theory asserts that policy uncertainty enhances trade performance, as risk-averse firms are incentivized to increase investments to offset potential losses (Hartman, 1972). Additionally, the growth option theory demonstrates a positive correlation between policy uncertainty and investment, thereby benefiting trade dynamics, a viewpoint aligned with the Qi-Hartman-Abel theory’s assertion that firms increase investment in the face of elevated uncertainty (Abel, Citation1983).

Based on these theoretical foundations, some empirical studies have been conducted. However, most of the existing empirical studies mainly focus on the effects of policy uncertainty on export performance in different countries. The major empirical works on the link between EPU and trade performance are reported in . However, empirical studies regarding the relationship between agriculture exports and policy uncertainty are scarce, even though the sector is the most exposed to policy fluctuations.

Table 1. Empirical literature on EPU-trade nexus.

Thus, the following hypothesis is articulated based on the theoretical and empirical literature.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): EPU adversely affects agricultural exports.

2.2. Agriculture sector and trade policies

Reformation and strategic trade policy development are common in high-income and emerging economies (Drelich-Skulska & Domiter, Citation2018). Agricultural trade and domestic support policies have substantially changed over the previous twenty years. A few countries have started to focus more on environmental outcomes rather than providing direct subsidies to farmers for producing a particular good since support for the agricultural sector has become increasingly disentangled from production. However, several emerging economies have also significantly raised policy interventions that potentially distort production decisions, while some developed countries continue to support the agriculture sector heavily and in a way that is connected to production (OECD, Citation2020).

Generally, the agriculture trade policy has been changed frequently to respond to the risk of losses for significant groups by insulating the domestic market from international price fluctuations for agricultural goods (Freund & Özden, Citation2008). Also, protectionist trade policies have been implemented to restrict agriculture trade. As a result, the impacts of high border protection have been compounded by domestic support policies in many developed and developing countries.

Several policy actions have been applied to promote foreign trade, especially the agricultural exports of developed countries. For example, in the last two decades, the EU has reformed the common agricultural policy (CAP) several times (Gohin & Zheng, Citation2020). This complex and controversial agriculture policy is divided into two pillars and pursues several objectives with various tools (Kiryluk-Dryjska & Baer-Nawrocka, Citation2019). Primarily, it is concerned with direct payments and market-price instruments, while secondly, the pillar includes mostly rural development, agri-environmental and risk-management instruments. The first objective of this policy has significantly been reformed with the introduction of the reduction of price support levels and direct payments to farmers. Support for market prices is closely related to the output of commodities and significantly affects trade and agricultural productivity. EU agrifood tariffs result in the significant suppression of imports, around 14% of predicted trade. High tariffs protect some farming activities, distorting resource use in the agricultural sector and complicating trade negotiations (Swinbank, Citation2018). Additionally, agricultural policy has shifted focus toward social and environmental protection, enhancement, and risk management (Gohin & Zheng, Citation2020).

Furthermore, the developed countries’ policy for trade promotion arrays various laws governing the promotion of agricultural commodities in regional marketplaces. This policy aims to increase awareness of agricultural producers’ quality and unique production techniques and enhance the appreciation of agrifood products produced in the EU and other industrialized countries. For instance, in 2015, the EU reformed its policy framework to introduce new regulations to increase how effectively policies are implemented in foreign and domestic markets (FAO, Citation2019).

Also, the US widely used protective trade measures such as tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) to aid commodity support programs. Furthermore, some US agricultural policy actions have elements that supplement domestic demand, extend export demand, reduce supplies, and provide subsidies for some inputs (Glauber & Effland, Citation2016). Likewise, Canada’s agriculture trade policy provides support to balance competitiveness in global market integration with supporting sectors of the agricultural industry that are vital via market price support, export subsidies, and protective measures such as tariffs and tariff quotas.

Furthermore, emerging economies have also introduced several agricultural trade policies in the last two decades. Policy changes and fluctuations are also more common in emerging economies ( in Appendix A). The most common policy response taken by emerging economies has been to reduce or suspend import tariffs on food products, impose export barriers in the form of export restrictions or export taxes, and stimulate domestic production by raising minimum prices and expanding input subsidies. Moreover, during the commodity price spikes in 2007-08 and 2010-11, several emerging countries implemented temporary export restrictions on agricultural goods to protect domestic consumers from rising and volatile prices. For example, the maize ban in Argentina, the rice ban in India, and the wheat ban in the Russian Federation were some countries that restrict food exports (Deuss, Citation2017). Furthermore, non-tariff obstacles such as import licensing requirements, price controls on inputs and final commodities, and marketing restrictions remained to protect agriculture from global rivalry (OECD/ICRIER, Citation2018). Besides, concerns are also raised by policy developments, such as a significant increase in unbalanced domestic support in emerging market economies like China and India (Bouët & Laborde, Citation2017).

Also, during the last decade, Russian and Ukrainian grain exports were repeatedly diminished by harvest failures and further reduced by introducing the new policy of export restrictions (Fellmann et al., Citation2014). Additionally, Russia and Ukraine have faced external financing difficulties amid political instability and rapidly falling prices of their major export commodities (Pitterle et al., Citation2015). Likewise, Argentina has often reformed agricultural policies in the last two decades. The policies implemented between 2002 and 2015 put a lot of tax pressure on the agricultural sector, which affected the profitability of agriculture at the end of the period (Lema et al., Citation2018). To sum up, continuous policy reforms in emerging economies are one of the factors contributing to policy uncertainties. Hence, we develop the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): TPU negatively affects agricultural exports.

2.3. Logistics performance, trade agreements, policy uncertainty and trade flow

Logistics performance represents countries’ trade facilitation level and has been considered one of the critical elements of trade (Puertas et al., Citation2014). It comprises various transportation and non-transportation activities, including warehousing, brokerage, express delivery, terminal operations, and related data and information management. It has become a decisive factor in export competitiveness.

Agribusiness products present issues regarding logistics and supply chains that differ entirely from those concerning industrial products. These products, in general, are perishable during most of the processing stage and, therefore, require good performance in the logistics activities (Marti et al., Citation2014). Thus, the continuous growth in world trade depends on the efficiency of trade support structures such as logistics services. Therefore, continuous logistics infrastructure and services investment can positively impact international trade (Gani, Citation2017).

Similarly, trade agreements can significantly affect countries’ export performance. Trade agreements, whether global, regional or bilateral, are policy instruments that can increase market efficiency, expand trade, and enhance the economic welfare of participant countries (Vollrath & Hallahan, Citation2011). The agreements are not only limited to removing tariff barriers and customs duties but also create an environment for associated reforms to domestic tax and revenue policies, affecting overall economic activities in general and export performance in particular.

Additionally, if the trade agreements are efficiently considered, they can encourage cooperation on policies across economies, thereby increasing global trade (Obradovic, Citation2012). The negative effects of EPU can be reduced by countries that are members of trade agreements because these agreements cover not only trade but also other related economic activities like anti-corruption, capital and person movement, competition, e-commerce, investment, state-owned enterprises and intellectual property rights. In today’s more interconnected economies, these are important policy challenges must be addressed (OECD, Citation2020). To lessen the negative impacts of policy uncertainties, they lower trade costs and set several regulations that govern how economies function. Hence, the following hypotheses are formulated.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Regional trade agreements and logistics performance mitigate the adverse effects of EPU on agricultural exports.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. Theoretical underpinning and model construction

The theoretical underpinning of the connection between uncertainty and agricultural export rests on different theoretical foundations. The theoretical base of the effects of TPU and EPU on agricultural export can be connected to real options theory, which states that policy uncertainties produce a real option value of waiting and conservatively by raising the risk of irreversible investments (Bernanke, Citation1983), which negatively affects agricultural reports of the countries.

Moreover, the association between uncertainties and agricultural export can be explained from the view that due to risk, exporting companies delay entering new markets and reduce their investments in already established ones (Handley, Citation2014), which can adversely affect countries’ production and export performance. Based on this theoretical background, we argue that TPU and EPU will adversely affect the countries’ agricultural exports. Therefore, the AE (agricultural export) defined in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) below is assumed to be negatively influenced by policy uncertainties (

).

(1)

(1)

The variable AEij,t denotes agriculture export. Xij,t represents variables indicating size terms, such as the population size of the exporting and importing countries and their GDP per capita. Cij represents the trade cost variables such as bilateral distance between trading partners, RTA which is the dummy variable that accounts for the presence of regional trade agreement considering the value of one and zero amongst trade parties i and j at time t; alternatively, common currency which is the dummy variable accounting one for using common currency and zero otherwise, tariff rate and real exchange rate.

The selection of control variables is based on the gravity model. Theoretically, GDP per capita and population size of origin and destination represent the economic size of countries and are expected to affect agricultural exports positively (Tinbergen, Citation1962). Besides, the distance between trading countries and agricultural exports is expected to be negatively associated ((Tinbergen, Citation1962). Moreover, common currency and RTA positively influence agricultural exports of countries (Coskuner & Olasehinde-Williams, Citation2017; Yotov et al., Citation2016). The theoretical justification for the link between these variables and trade performance can be extended from gravity specification in Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) .

3.2. Theoretical bases of gravity model

The mass of the origin and destination countries (Mi and Mj), as well as the physical distance (dij) between them, are the two factors that the forecast of gravity specification will use to determine the flow of trade (Tij) across countries (Tinbergen, Citation1962). Below is Equationequation (2)(2)

(2) , which represents the basic gravity model.

(2)

(2)

Where δ and θ stand for constant and parameters, correspondingly.

The ordinary least-squares (OLS) approach has been the most often utilized method for solving gravity equations since Tinbergen’s standard gravity model from 1962. A drawback of the OLS approach is that when data is changed into a logarithmic form, zero-valued observations are omitted from the sample; hence, the method cannot consider the information such observations possess. Consequently, eliminating observations with zero values decreases data efficiency and results in skewed estimations (Gómez-Herrera, Citation2013).

Moreover, the standard gravity specifications still suffer biases and inconsistency and can be avoided with stricter adherence to gravity theory (Yotov et al., Citation2016). For example, certain issues should be strictly taken into consideration in the gravity specifications, such as multifaceted resistance (Baldwin & Taglioni, Citation2006), zero flows of trade (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006), the trade data’s heteroscedasticity (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006), reverse causality and the costs of bilateral trade (endogeneity issue) (Baier & Bergstrand, Citation2009). The specifications for the structural gravity model address these problems. Hence, the structural gravity model is specified in Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) .

(3)

(3)

EquationEquation (3)(3)

(3) can be conveniently decomposed into two terms. The first component is a size term

and the second component is a trade cost term

If there were no trade expenditures, the size term would be intuitively understood to represent the hypothetical extent of seamless trade between parties i and j. The size term in Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3) contains precious information concerning the connection between bilateral trade flows and country size. In other words, the large producers will export more to all destination countries and import more from all origin countries, and, therefore, trade between countries i and j will be more substantial the more similar in size the trading countries are (Yotov et al., Citation2016).

The explanation of the trade cost term is that it represents the overall impacts of costs of trading that determine a wedge between frictionless and realized trade. The term trade cost has three constituents (regional trade agreements (RTAs), bilateral trade and regional blocs, and multilateral resistance terms hereafter (MRT)) (Yotov et al., Citation2016).

One of the issues seriously considered with the gravity Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) is the estimate that the MRT (PjΠi) is a theoretical construct and not directly observable by the researchers. Proper MRT control is important to avoid committing the Gold Medal Mistake (Baldwin & Taglioni, Citation2006). We use panel data in a structural gravity estimation framework to account for countries-time fixed effects, which allows us to control the MRT.

Besides, there will be an endogeneity problem between policy uncertainty and trade flow. Failure to solve the potential reverse causality may result in bias of the gravity estimates. The endogeneity issues can be addressed by controlling the countries’ pair fixed effects (Baier & Bergstrand, Citation2009; Egger & Nigai, Citation2015). Thus, the pair-fixed effect has been considered to solve endogeneity concerns.

Furthermore, trade gravity specification should consider heteroscedasticity and observations with zero values concerns (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006). Rather than estimating the gravity model in logarithmic form, it is more convenient to use multiplicative form when solving zero trade flows.

3.3. PPML estimation strategy

Due to a multiplicative error element that requires the modification of an estimating approach, the initial specifications of the non-linear gravity model with the existence of heteroscedasticity are subject to the premise. Santos Silva and Tenreyro (Citation2006) give a simple solution to the heteroscedasticity problem. They indicate that the PPML approach yields reliable estimations of the initial non-linear model, provided the gravity model has the appropriate collection of explanatory factors.

Therefore, in this study, the PPML model is utilized to examine the structural gravity model of the impacts of policy uncertainty on agriculture exporting. Thus, Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) is reformulated in Equationequation (3)

(3)

(3) to exercise policy uncertainty’s effects on countries’ agriculture exports.

(4)

(4)

EPUi,t is the economic policy uncertainty indicator. ψij represents the pair-fixed impacts. The term πi, t refers to the set of export-time fixed and import-time fixed effects, which account for any other observable and unobservable variables, as well as the multilateral resistance term exporter-specific factors that may influence export. Finally, the PPML estimator does not matter if the error term εij, t in Equationequation (4)(4)

(4) is outlined as a multiplicative or additive (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, Citation2006).

The logistics performance may affect policy uncertainty’s effects on agriculture exports. Businesspeople may postpone decisions on trade and trade-related investments in the business sector due to poor logistical performance. This will, therefore, intensify the uncertainty and strengthen its detrimental impact on the export of agricultural products. In contrast, strong logistics performance promotes firms’ engagement in the export market and mitigates policy uncertainty. Thus, based on this notion, the interaction term of EPU and logistics performance is introduced to the model. We create a binary variable assigning one for countries above the mean value of the rank of LPI and zero otherwise.

Likewise, the relationship between policy uncertainty and agriculture exports can be affected by trade agreements between or among trading countries because they are policy instruments that can increase market efficiency, expand trade, and enhance the economic welfare of participant countries (Vollrath & Hallahan, Citation2011). Besides, if the trade agreements are efficiently considered, they can promote policy collaboration across economies, thereby increasing international trade. Thus, a dummy variable was introduced for trade agreements included in the model, assigning one for countries with bilateral and regional trade agreements and zero otherwise.

(5)

(5)

Where TA and LPI represent trade agreements and logistics infrastructure performance, respectively.

Besides, it is supposed that the impacts of EPU on agriculture exports might differ, conditional on the macroeconomic condition of the countries. Producers may become pessimistic about future market pricing and demand due to poor macroeconomic performance, which could lead them to delay making decisions on trade-related agricultural investments. This will intensify the uncertainty and aggravate its adverse impact on trade in agriculture and vice versa. Thus, the interaction term of GDP per capita and policy uncertainty has been considered to examine the role of GDP per capita (EPU*GDPc) in the relationship between agriculture export and policy uncertainty modifying Equationequation (4)(4)

(4) .

(6)

(6)

Finally, all preceding equations have a log-linear version when estimated following structural gravity models.

3.4. Data

This study uses data from 60 exporter and 60 destination countries (see Appendix B). Besides, as the logistics performance index data was accessible for these years, we considered data for 2007, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2018. We used data for agriculture export from the International Trade and Production Database for Estimation (ITPD-E), containing consistent data on international and domestic trade at the industry level, including agriculture, to avoid the gold medal mistake of not controlling multilateral resistance. Additionally, the UNcomtrade database was used to gather data concerning the overall trade flow.

The policy uncertainty data was exploited from the world policy uncertainty data index in the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) report. The index captures the average uncertainty frequency related to key economic and political developments reported in the EIU report. A higher number indicates higher policy uncertainty and vice versa.

The World Development Indicators (WDI) databases were used to obtain the exporting and importing countries’ population and real per capita GDP. The real exchange rate was used from International Financial Statistics (IFS), and the ad-valorem duty on imports imposed by country j was extracted from the World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS) database. LPI data was derived from the World Bank database. The CEPII database extracted additional variables like distance, RTA, and common currency. in Appendix A presents descriptive statistics for the variables under consideration.

4. Results and findings

4.1. Baseline results

presents the impact of the EPU on trade in general and the agriculture export functionality of the countries. In Column (I) and Column (III), we examine the effects of EPU on the overall trade flow and agriculture export, controlling the exporter-time fixed effects. We repeat the procedure in Columns (II) and (IV) to control the country pair-fixed effects, importer-time fixed effects, and exporter-time fixed effects. The inclusion of the exporter-time fixed effects and importer-time fixed effects allows us to control for the unobservable MRT as well as potentially for any other observable and unobservable characteristics that change over time for each exporter and importer, as was thoroughly discussed in section 3 (Yotov et al., Citation2016). Additionally, they will absorb and control all contemporaneous and lagged countries’ specific characteristics.

Table 2. The effects of EPU on the overall flow of trade.

The pair-fixed effect has been considered to solve reverse causality concerns because there will be reverse causality between trade flow and EPU. Failure to solve the potential reverse causality may result in bias of the gravity estimates. In addition to addressing the reverse causality issues, including the pair-fixed effect in structural gravity provides a flexible and comprehensive account of the effects of all time-invariant bilateral trade costs because pair-fixed effects have been shown to carry systematic information about trade costs in addition to the information captured by the standard gravity variables (Egger & Nigai, Citation2015). Therefore, we repeated the exercise in Columns (II) and (IV) for aggregate trade flow and agriculture export. Time invariant variables such as the distance between reporter and partner countries and common currency are excluded from the specifications.

Trade theories and the results of earlier applications are both supported by the standard gravity variables’ coefficients. The findings imply that Real GDP per capita has a significantly positive impact on countries that import and export, indicating that the magnitude of the economies of the exporting and importing countries has a significant effect on the export performance of those countries in the agricultural sector. Furthermore, there is a robustly favorable association that exists between the population sizes of the exporting and importing countries and agricultural exports. A statistically significant and adverse association between the physical distance between exporting and importing countries and the performance of agriculture exports indicates that physical distance hinders trade between countries. This finding aligns with the trade theory, which states that trade between countries increases with shorter distances and reduced transaction costs. Additionally, the export of agricultural products is strongly positively impacted by common currency, suggesting that countries that use it trade more than those that do not.

Furthermore, one of the policy variables, regional trade agreements, has a significantly favorable effect on agricultural exports across all parameters. This finding supports the theory that regional trade agreements greatly enhance trading linkages among member countries.

Concerning our variables of interest, the findings provide compelling evidence that EPU significantly negatively impacts overall trade flow and agricultural export consistent with hypothesis 1. These findings align with the view that policy conditions play a crucial role when companies make costly, irreversible decisions like incorporating new technology, manufacturing new products, or entering new markets (Handley, Citation2014).

We further applied counterfactual simulation analysis to estimate the tariff equivalent of EPU reduction to the average for agriculture export using results in Column (IV) in . It indicates the percentage gain in performance that would result from raising EPU to the average, supposing that the action on EPU taken by the countries leads to a unit improvement in the policy uncertainty index. This results in a percent improvement in agriculture exports. The percentage change in agriculture export made by improvement in EPU to the average can be converted to tariff equivalent value using

The results imply that if reform is made to improve EPU to the average, agriculture exports would improve by 15.6%. This improvement in agriculture exports would be equivalent to reducing the tariff rate by about 2.57%.

4.2. The effects of EPU based on countries’ heterogeneity

We further examine the effects of policy uncertainty according to the countries in the sample heterogeneity because the countries considered in this study are of different levels of economic status in high-income countries and emerging economies. The classification is based on the IMF Fiscal Monitor list. To deal with MRT, importer-time, exporter-time and pair fixed effects are retained in the models. However, time-invariant variables, except for a policy variable (RTA), are dropped.

The main findings in regarding the EPU and standard gravity variables are qualitatively identical to the baseline findings for the whole sample and are consistent across emerging and high-income economies. More specifically, the finding implies that the impact of EPU on the agricultural export of both high-income and emerging economies is negative and statistically significant, implying that high policy uncertainty has a detrimental effect on the agricultural export of the two groups of countries.

Table 3. The impacts of EPU on agriculture export based on countries’ heterogeneity.

4.3. The moderating role of trade agreements and logistics performance

The impacts of policy uncertainty on agriculture exports can be affected by the logistics performance and trade agreements. Examining the trade’s mediating function agreement and logistics performance discussed in section two is worthwhile because profound trade agreements among countries and logistics performance are vital institutional and physical infrastructures for trade integrations and can significantly contribute to mitigating policy uncertainty startles. Therefore, we presented the terms for the interaction of trade agreements and policy uncertainty as well as logistics performance and policy uncertainty into our model and found results reported in below.

Table 4. The moderating role of logistics performance and trade agreements.

The findings show that the coefficient of logistics performance is positive and statistically significant, indicating that it can positively influence agriculture exports. Besides, the interaction between the EPU and logistics performance is positive and statistically significant, implying that the negative impact of policy uncertainty is higher for countries with weak logistics performance. Besides, the coefficients of the trade agreement and the interaction term of trade agreements and EPU are positive and statistically significant. Thus, trade agreements among trading countries can weaken the negative effect of policy uncertainty on agriculture exports. These findings are consistent with hypothesis 3.

4.4. GDP per capita’s role

The conditional impact of policy uncertainty on agricultural exports subject to GDP per capita is analyzed (). The agricultural export partial derivative subject to EPU can be used to determine its value.

Table 5. The moderating role of GDP per capita.

The coefficient of the interaction term between the EPU and GDP per capita of exporter countries is positive and statistically significant, indicating that the higher the GDP per capita in the exporting country, the weaker the negative effects of EPU on agriculture export. This finding is consistent with theoretical predictions in trade models.

4.5. Impacts of TPU on the aggregate flow of trade and agriculture export

The EPU considered in the sections above contains several categories of uncertainties, including trade, fiscal, monetary, regulatory, and other policies. Alternatively, we used TPU as an alternative policy uncertainty proxy and re-exercised our model because TPU is more specific to the trade. TPU effects come from the expected and unexpected tariff increase, antidumping duties, anticipatory stockpiling of goods, gap between bound and applied tariff rates, uncertain exchange rates and globalization (Gopinath, Citation2021), which factors that can significantly affect agriculture exports. TPU directly captures agriculture trade policies discussed in section two in detail. Thus, it is worthwhile to analyze the impacts of TPU on agriculture exports.

The results of the effects of TPU on the overall flow of trade and agriculture exports are reported in below. In Column (I) and Column (III), the findings of the impacts of TPU on aggregate trade and agriculture export controlling the exporter-time are fixed, respectively. The exercise is repeated in Column (II) and Column (IV), adjusting for country pair fixed effects, importer-time fixed effects, and exporter-time fixed effects for both aggregate and agricultural exports. The findings implied that TPU has an adverse effect on the agricultural export performance of countries, which is congruent with hypothesis 2.

Table 6. The impacts of TPU on agriculture export.

We re-examined the impacts of TPU on agriculture exports based on the heterogeneity of the sample countries. The outcomes are presented below in .

Table 7. The impacts of TPU on agriculture export based on countries’ heterogeneity.

Besides, the TPU coefficient on emerging economies’ agriculture exports is negative and significant at a 1% significance level. However, the impact of TPU on developed countries’ agricultural exports is insignificant even though its sign is consistent with the baseline results. Therefore, the impact of TPU shocks varies among countries. Emerging economies have far more severe agricultural export losses following a high TPU shock than high-income countries.

5. Discussions and policy implications

The study showed that the EPU adversely impacted the countries’ agricultural export performance. The findings are consistent and expected as agricultural export is exposed to policy uncertainties and fluctuations. The findings thus align with theoretical notions about the connection between uncertainty and international trading. For instance, uncertainty provides an actual waiting option’s value and is conservative by raising the risk associated with irreversible investments (Bernanke, Citation1983). In order to refrain from incurring higher initial startup costs, companies delay entering new markets in an environment of increasing uncertainty, which reduces exports (Greenland et al., Citation2019). Therefore, uncertainty in future macroeconomic policies—such as tax, regulatory, fiscal, and monetary policies—affects a country’s export of agricultural products (Baker et al., Citation2016).

Similarly, TPU has adverse impacts on the agriculture export performance of countries. It supports the assumption that TPU adversely affects trade flow because subject to frequent changes and uncertainties of policies concerning tariffs, antidumping duties, anticipatory stockpiling, bound and applied tariff rates, exchange rates and globalization (Gopinath, Citation2021), the negative association between agriculture export and TPU is expected, and their counter retaliatory actions substantially result in high uncertainty and adversely affects agriculture export.

These findings are consistent with a few research papers on the connection between trade and policy uncertainty (Handley, Citation2014; Greenland et al., Citation2019; Novy & Taylor, Citation2020). Besides, the findings of this research align with the theoretical linkage between uncertainty and trade performance. More specifically, the results of this study align with the option theory of investment, which emphasizes the role of policy uncertainty in influencing investment decisions. It posits that during periods of heightened political, economic, and policy uncertainty, firms tend to postpone investment and refrain from engaging in trade. Furthermore, the findings are consistent with the theoretical framework proposed by Handley (Citation2014), suggesting that escalating uncertainties compel firms to delay market entry to mitigate the risk of sunk entry costs.

Besides, further analysis has been conducted, categorizing sample countries based on their income level (developed and emerging economies). This study’s results show that the impact of EPU on agricultural exports of both developed and emerging economies is negative and statistically significant, implying that high EPU has a detrimental effect on agricultural exports of the two groups of countries. However, emerging economies’ agriculture exports are most significantly affected by TPU compared to developed countries.

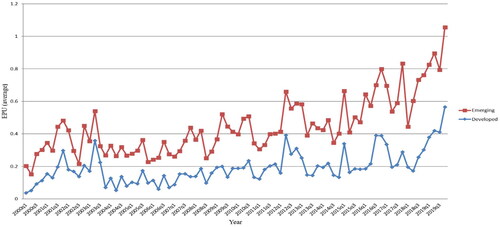

This finding is in line with the study results by Carrière-Swallow and Céspedes (Citation2013) argue that policy uncertainty shocks take significantly longer to recover in developing countries than in developed countries. Thus, careful consideration of policy uncertainty, especially for emerging economies, is important as trade connectedness and globalization have increased the competition for agriculture exports in emerging economies. Besides, emerging economies in the sample experienced more fluctuations in economic policies than developed countries ( in Appendix A), implying policy takeaways to reduce policy uncertainties.

Furthermore, the analysis of the counterfactual simulation that is carried out to calculate the illustrative tariff equivalent demonstrates that policy uncertainty has a substantial effect on the performance of the countries’ agricultural exports. The counterfactual simulation results help simulate the expected benefits from policy measures to ensure the EPU to the mean value. It demonstrates that policy action to keep EPU at an average of the sample results in 2.57% in the tariff rate. Therefore, the counterfactual simulation of the average level of policy uncertainty to the tariff equivalent is robustly crucial because it is frequently preferable to convey the impacts of the target variable, whereby policy measures are to be implemented, in a consistent measure and solves difficulties with quantifying the effects showing how export performance is affected by changes in the target variable.

It is interesting to observe that trade agreements, bilateral or regional, can weaken the adverse impacts of policy uncertainty. This finding is consistent with the theories because one of the essential contributions of trade agreements is to increase the predictability of trade and economic policy to help mitigate policy uncertainty’s effect on agriculture exports. Thus, it is intuitive that trade agreements, through policy commitment and credibility, can reduce uncertainty about trade-restrictive measures and policies. Thus, as stated by Imbruno (Citation2019) and Vollrath and Hallahan (Citation2011), trade can be promoted and uncertainty reduced by the commitments made under regional and bilateral trade agreements. The results further provide evidence that strong logistics performance mitigates policy uncertainty’s effect on agriculture exports. Therefore, creative and standardized logistics services can facilitate the smooth flow of commodities and mitigate uncertain economic and unstable financial situations (Beškovnik & Beškovnik, Citation2017; Jiao et al., Citation2019). The findings further depict that the negative impact of the policy uncertainty on agriculture exports appears to be decreasing in GDP per capita.

This study’s findings help clarify the complex relationship between policy dynamics and agricultural trade, enabling policymakers to craft more resilient and adaptive policies. Understanding the effects of EPU and TPU allows stakeholders in the agricultural sector to anticipate and mitigate risks, fostering stability and resilience in agricultural exports. Therefore, it contributes to strategic decision-making for agricultural producers, exporters, governments and policymakers, facilitating informed responses to market fluctuations and policy changes. Hence, the following specific policy implications are forwarded.

One notable policy suggestion derived from the study’s findings is that policymakers should act quickly and decisively to lower high levels of uncertainty to support agricultural exports. Also, governments and decision-makers could consider implementing mechanisms and strategies to swiftly adjust agricultural policies in response to EPU, thereby mitigating adverse impacts on the countries’ agricultural exports.

Moreover, as agriculture exports are subject to several high border protection policies supplemented by domestic support strategies, policymakers should critically evaluate the uncertain effect of the trade and economic policies they formulate. Besides, policymakers should develop policy frameworks to promote diversification through trade agreements, market development initiatives, and support for value-added agricultural products.

Another policy implication of this study is that governments should be committed to improving logistics infrastructure because constant investment in services and infrastructure for logistics can positively impact agriculture exports and reduce the negative effect of uncertainty on them. More specifically, enhancements to logistics and transportation are increasingly relevant to the agricultural exports of emerging economies.

Additionally, robust risk management mechanisms for agricultural producers and exporters are important to partly mitigate the negative effects of EPU on agricultural exports. Therefore, governments should develop insurance schemes or export promotion programs tailored to mitigate the risks linked with economic and trade policy uncertainties, thereby enhancing the agricultural sector’s resilience and exports.

Furthermore, this study highlights the importance of establishing trade agreements to promote agricultural exports and reduce the policy uncertainty effect. Policymakers should focus on policies related to visible barriers and policies regarding invisible barriers of trade.

However, this study’s findings are limited to 60 exporting and 60 importing advanced and developing country trade pairs. Future research should broaden the analysis to encompass the impact of economic and trade policy uncertainties on agricultural exports of a larger panel of countries. Also, conducting a more comprehensive assessment of the effects of EPU on agricultural exports at the commodity level would be valuable as all agricultural commodities are not equally affected by economic and trade policy uncertainties.

Authors contribution

Tadesse Soka Gignarta Designed and conceptualized the research, performed formal analysis and wrote the draft; Zhenzhong Guan prepared material, participated in data collection, and performed formal analysis; and Dinkneh Gebre Borojo participated in writing the first draft, data analysis and editing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, TSG, upon reasonable request.

References

- Abel, A. B. (1983). Optimal investment under uncertainty. The American Economic Review, 73(1), 228–233.

- Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2021). World pandemic Uncertainty index. FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/

- Anderson, K. (2016). Agricultural trade, policy reforms, and global food security. Palgrave Studies in Agricultural Economics and Food Policy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-46925-0_9

- Baier, S. L., & Bergstrand, J. H. (2009). Estimating the effects of free trade agreements on international trade flows using matching econometrics. Journal of International Economics, 77(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2008.09.006

- Baker, S. R., Bloom, S., & Davis, S. J. (2016). Measuring economic policy uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1593–1636. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw024

- Baldwin, R., & Taglioni, D. (2006). Gravity for dummies and dummies for gravity. Equations (NBER Working Paper No. 12516). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Bekkers, E. (2019). Challenges to the trade system: The potential impact of changes in future trade policy. Journal of Policy Modeling, 41(3), 489–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.03.016

- Benigno, P., Canofari, P., Di Bartolomeo, G., & Messori, M. (2020). Uncertainty and the pandemic shocks. Monetary dialogue papers, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies. file:///E:/EPU/COVID-19/IPOL_IDA(2020)658199_EN%20(1).pdf

- Bernanke, B. S. (1983). Irreversibility, uncertainty, and cyclical investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 98(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.2307/1885568

- Beškovnik, B., & Beškovnik, E. (2017). Restructuring the business environment: Application of the creative environment in Slovenian logistics companies. Transformations in Business & Economics, 16(1), 121–133. http://www.transformations.knf.vu.lt/40/lt/article/tran

- Bonciani, D., & van Roye, B. (2015). Uncertainty shocks, banking frictions and economic activity (European Central Bank Working Paper 1825). https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1825.en.pdf

- Borojo, D. G., Yushi, J., & Miao, M. (2021). The impacts of economic policy uncertainty on trade flow. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 58(8), 2258–2272. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2021.1971075

- Borojo, D. G., Yushi, J., Miao, M., & Xiao, L. (2023). The impacts of economic policy uncertainty, energy consumption, sustainable innovation, and quality of governance on green growth in emerging economies. Energy & Environment, 0958305X2311739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958305X231173997

- Bouët, A., & Laborde, D. (2008). The potential cost of a failed Doha round. (IFPRI Issue Brief No. 56).

- Bouët, A., & Laborde, D. D. (2017). Conclusion: Which policy space in the international trade arena can support development and food security?: IFPRI book chapters. In A. Bouët, & D. Laborde Debucquet (Ed.), Agriculture, development, and the global trading system: 2000– 2015, chapter 13. International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

- Carballo, J., Handley, K., & Limão, N. (2022). Economic and policy uncertainty: Aggregate export dynamics and the value of agreements. Journal of International Economics, 139, 103661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2022.103661

- Carrière-Swallow, Y., & Céspedes, L. F. (2013). The impact of uncertainty shocks in emerging economies. Journal of International Economics, 90(2), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2013.03.003

- Chaturvedi, S. (2018). India’s approach to multilateralism and evolving global order. The Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, 13(2), 128–135.

- Chong, T. T., & Li, X. (2019). Understanding the China-US trade war: Causes, economic impact, and the worst-case scenario. Economic and Political Studies, 7(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/20954816.2019.1595328

- Constantinescu, C., Mattoo, A., & Ruta, M. (2020). Policy uncertainty, trade and global value chains : Some facts, many questions. Review of Industrial Organization, 57(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-020-09772-0

- Coskuner, C., & Olasehinde-Williams, G. O. (2017). Estimating the effect of common currency on trade in West African Monetary zones: A dynamic panel-GMM analysis. In N. Özataç & K. GÖKMENOGLU (Eds.) New challenges in banking and finance. Springer proceedings in business and economics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66872-7_9

- Crowley, M., Meng, N., & Song, H. (2018). Tariff scares: Trade policy uncertainty and foreign market entry by Chinese firms. Journal of International Economics, 114, 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.05.003

- Deuss, A. (2017). Impact of agricultural export restrictions on prices in importing countries. (OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 105). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/1eeeb292-en

- Díaz-Bonilla, E (2017). Food security stocks: Economic and operational issues. In A. Bouët & D. Laborde Debucquet (Eds.), Agriculture, development, and the global trading system: 2000– 2015. Chapter 8. (pp. 233–283). International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI). https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896292499_08

- Drelich-Skulska, B., & Domiter, M. (2018). Trade policy protectionism in the 21st century. Transformations in Business & Economics, 17(2A (44A)), 353–371. http://www.transformations.knf.vu.lt/44a/lt/article/prek

- Egger, P., & Nigai, S. (2015). Structural gravity with dummies only: constrained ANOVA- Type estimation of gravity models. Journal of International Economics, 97(1), 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.05.004

- FAO. (2019). Agrifood marketing and export promotion policies: case studies of Austria, Brazil, Chile, Estonia, Poland and Serbia (p. 48).

- Fellmann, T., Hélaine, S., & Nekhay, O. (2014). Harvest failures, temporary export restrictions and global food security: The example of limited grain exports from Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Food Security, 6(5), 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-014-0372-2

- Freund, C., & Özden, C. (2008). Trade policy and loss aversion. American Economic Review, 98(4), 1675–1691. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.4.1675

- Gani, A. (2017). The logistics performance effect in international trade. The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 33(4), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsl.2017.12.012

- Gholipour, H. F. (2019). The effects of economic policy and political uncertainties on economic activities. Research in International Business and Finance, 48, 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2019.01.004

- Gilmour, B., Samarajeewa, S., & Gurung, R. (2012). India: An agrifood prospectus. Transnational Corporations Review, 4(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2012.11658319

- Glauber, J., & Effland, A. (2016). United States agricultural policy: Its evolution and impact (IFPRI Discussion Paper 1543). Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2813385

- Gohin, A., & Zheng, Y. (2020). Reforming the European common agricultural policy: From price & income support to risk management. Journal of Policy Modeling, 42(3), 712–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2020.02.008

- Gómez-Herrera, E. (2013). Comparing alternative methods to estimate gravity models of bilateral trade. Empirical Economics, 44(3), 1087–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-012-0576-2

- Gopinath, M. (2021). Does trade policy uncertainty affect agriculture? Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(2), 604–618. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13083

- Gould-Davies, N. (2018). Economic effects and political impacts: Assessing Western sanctions on Russia. (BOFIT Policy Brief 8/2018).

- Greenland, A., Ion, M., & Lopresti, J. (2019). Exports, investment and policy uncertainty. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue Canadienne D'économique, 52(3), 1248–1288. https://doi.org/10.1111/caje.12400

- Handley, K. (2014). Exporting under trade policy uncertainty: Theory and evidence. Journal of International Economics, 94(1), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2014.05.005

- Hu, G., & Liu, S. (2021). Economic policy uncertainty (EPU) and China’ s export fluctuation in the post-pandemic era : An empirical analysis based on the TVP-SV-VAR Model. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 788171. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.788171

- Imbruno, M. (2019). Importing under trade policy uncertainty: Evidence from China. Journal of Comparative Economics, 47(4), 806–826. www.elsevier.com/locate/jce https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2019.06.004

- Jia, F., Huang, X., Xu, X., & Sun, H. (2020). The effects of economic policy uncertainty. Prague Economics Papers, 29, 600–622. https://doi.org/10.18267/j.pep.754

- Jiao, R., Zhao, G., & Wang, F. (2019). Standardization of logistics services, business efficiency and economic impact. Transformations in Business & Economics, 18(3), 168–190. http://www.transformations.knf.vu.lt/48/lt/article/logi

- Kiryluk-Dryjska, E., & Baer-Nawrocka, A. (2019). Reforms of the common agricultural policy of the EU: Expected results and their social acceptance. Journal of Policy Modeling, 41(4), 607–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.01.003

- Lema, D., Gallacher, M., Yerovi, J. E., & De Salvo, C. P. (2018). Analysis of agricultural policies in Argentina 2007–2016. Inter-American Development Bank.

- Li, X. (2020). The impact of economic policy uncertainty on insider trades: A cross-country analysis. Journal of Business Research, 119, 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.025

- Li, Y., & Li, J. (2021). How does China ’s economic policy uncertainty affect the sustainability of its net grain imports? Sustainability, 13(12), 6899. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126899

- Liu, Q., Li, Z., & Wang, Y. (2024). The heterogeneous impact of economic policy uncertainty on export recovery of firms: The role of the regional digital economy. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 16(5), 100044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rspp.2024.100044

- Marti, L., Puertas, R., & García, L. (2014). Relevance of trade facilitation in emerging countries’ exports. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 23(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2012.698639

- Mueller, B., & Mueller, C. (2016). The political economy of the Brazilian model of agricultural development: Institutions versus sectoral policy. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 62, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2016.07.012

- Nguyen, D. X. (2012). Demand uncertainty: Exporting delays and exporting failures. Journal of International Economics, 86(2), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.10.007

- Novy, D., & Taylor, A. M. (2020). Trade and uncertainty. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 102(4), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00885

- Obradovic, L. (2012). The role of bilateral and regional trade agreements in the modernisation of taxation and revenue policy in developing economies. World Customs Journal, 6(2), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.55596/001c.92839

- OECD. (2020). Agricultural policy monitoring and evaluation. https://www.oecd.org/agriculture/topics/agricultural-policy-monitoring-and-evaluation/

- OECD/ICRIER. (2018). Agricultural policies in India, OECD food and agricultural reviews. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264302334-en

- Pitterle, I., Haufler, F., & Hong, P. (2015). Assessing emerging markets’ vulnerability to financial crisis. Journal of Policy Modeling, 37(3), 484–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2015.03.010

- Puertas, R., Martí, L., & García, L. (2014). Logistics performance and export competitiveness: European experience. Empirica, 41(3), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-013-9241-z

- Robinson, S., & Thierfelder, K. (2018). NAFTA collapse, trade war and North American disengagement. Journal of Policy Modeling, 40(3), 614–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2018.03.011

- Robinson, S., & Thierfelder, K. (2019). Global adjustment to US disengagement from the world trading system. Journal of Policy Modeling, 41(3), 522–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2019.03.019

- Santos Silva, J. M. C., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 88(4), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.88.4.641

- Sui, H., Li, X., Raza, A., & Zhang, S. (2022). Impact of trade policy uncertainty on export products quality: New evidence by considering role of social capital. Journal of Applied Economics, 25(1), 997–1024. https://doi.org/10.1080/15140326.2022.2087341

- Swinbank, A. (2018). Tariffs, trade, and incomplete CAP reform. Studies in Agricultural Economics, 120(2), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.7896/j.1809

- Tinbergen, J. (1962). Shaping the world economy: Suggestions for an international economic policy. The Twentieth Century Fund.

- Tunç, A., Savaş, S., & Barak, D. (2023). The causality between agricultural raw materials and economic policy uncertainty: evidence from the time- varying granger causality tarimsal hammaddeler ve ekonomi politikasi belirsizliği nedensellik ilişkisi : zamanla değişen granger. 19:1–13.

- Vollrath, T. L., & Hallahan, C. B. (2011). Reciprocal trade agreements: Impacts on bilateral trade expansion and contraction in the world agricultural marketplace (Economic Research Report 102755). United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Wen, J., Khalid, S., Mahmood, H., & Zakaria, M. (2021). Symmetric and asymmetric impact of economic policy uncertainty on food prices in China : A new evidence. Resources Policy, 74, 102247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102247

- Yan, H., Xiao, W., Deng, Q., & Xiong, S. (2022). Analysis of the impact of U.S. trade policy uncertainty on China based on Bayesian VAR model. Journal of Mathematics, 2022, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7124997

- Yayi, C. L. (2023). Economic policy uncertainty and trade: does export sophistication matter? Applied Economics, 56(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2166672

- Yotov, Y. V., Piermartini, R., Monteiro, J.-A., & Larch, M. (2016). An high-income guide to trade policy analysis: The structural gravity model. http://vi.unctad.org/tpa

- Yu, Y., Peng, C., Zakaria, M., Mahmood, H., & Khalid, S. (2023). Nonlinear effects of crude oil dependency on food prices in China: Evidence from quantile-on-quantile approach. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 24(4), 696–711. https://doi.org/10.3846/jbem.2023.20192

- Zhang, Z., Brizmohun, R., Li, G., & Wang, P. (2022). Does economic policy uncertainty undermine stability of agricultural imports ? Evidence from China. PloS One, 17(3), e0265279. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265279

- Zhang, R., & Qu, Y. (2022). The impact of U.S. trade policy uncertainty on the trade margins of China’s export to the U.S. Sustainability, 14(22), 15101. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215101

- Zhao, T. (2022). Economic policy uncertainty and manufacturing value-added exports. Engineering Economics, 33(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.33.1.27373

Appendix A

Table A1. Summary statistics of the variables.

Appendix B.

List of sample countries: Albania, Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil, Canada, China, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Denmark, Egypt, Finland, Germany, Georgia, Ghana, Guatemala, France, United Kingdom, Korea Rep., Kenya, India, Indonesia, Iran, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Pakistan, Portugal, Peru, Philippines, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Slovenia, Sweden, Sri Lanka, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uruguay, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Japan, USA