?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the effect of financial development on agricultural output growth, using autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) as the estimation strategy. The ARDL results suggest that the effect of financial development on agricultural output growth is positive and significant in both long run and short run. Specifically, our empirical analysis confirms that credit to the private sector is favourable for agricultural-output growth while net domestic credit and ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP are unfavourable for agricultural-output growth. However, three financial development indexes exert a positive impact on agricultural output, implying that an efficient financial market promotes agricultural growth. Hence, policies aimed at ensuring that the financial sector is well-developed can boost the growth of the agricultural sector. However, much effort, resources, and attention should be given to credit to the private sector.

Impact statement

Agriculture plays a major role in Ghana’s economy from the perspective of food production, productivity, source of employment, and ultimately as means of ending extreme poverty. The agricultural sector employs more than 50% of Ghanaians and contributes nearly 25% of the nation’s GDP growth. According to World Bank (Citation2018), the main export crop, cocoa, accounts for 20 to 25% of total foreign exchange earnings in Ghana. Therefore, the growth of the agricultural sector should be of keen interest to policymakers, government, and international bodies. However, implementing policies to promote agricultural growth requires sound empirical evidence. To contribute to literature as well as provide insight to policymakers, government, and international organizations, we examine the effect of financial development on agricultural output growth, utilizing different measures of financial development. Generally, the study finds that financial development promotes agricultural growth in the long run. This finding suggests that policies aimed at promoting and ensuring a strong linkage between the financial and the agricultural sectors can foster the growth of the agricultural sector.

1. Introduction

Globally, agriculture over the past five decades has grown, on average, by 2.24% per year (Fuglie & Rada, Citation2013). In Africa, the agricultural sector has made significant progress in recent years in terms of employment. For instance, agriculture employs about 60% of Africa’s population and provides raw materials for agro-based industries (Dhrifi, Citation2014; Kang & Zhao, Citation2022). More than 65% of Africa’s population is living in rural areas, out of which more than 90% of the rural population indirectly and directly engages in agriculture activities (World Bank, Citation2019). Also, Africa’s agriculture sector contributed approximately 61% of its gross domestic product from the period of 2011 to 2019 (World Bank, Citation2019). This suggests that agriculture is the backbone of Africa’s economy and can be used as a channel to end extreme poverty.

In Ghana, the agricultural sector comprising Crops, Livestock, Forestry, Logging, and Fishing, employs over 50% of Ghanaians and contribute to approximately 25% of the nation’s GDP growth (Wood, Citation2013). Since 2014, there has been an upheaval in the growth of agriculture output (Easterly, Citation2019). The financial sector of Ghana has contributed to the agricultural sector’s growth in several ways. For instance, in 1965 the government of Ghana established the Agricultural Development Bank to provide credit to crop/livestock and small farmers. Further, the government of Ghana received EUR 11 million in grants to establish the Financing Agricultural Project (FINGAB) and Outgrower and Value Chain Fund (OVCF) to improve financing and investment in agribusiness as well as provide medium-to-long-term credit, refinancing, and technical assistance to out-growers and small-holders farmers (Ussif, Citation2017). The FINGAB was a USAID program that enabled agribusiness to access funds from financial institutions, with a significant proportion of the funds going to agro-input dealers, processors, and farmers. Since 1965 the government of Ghana has developed various financial reforms to boost agricultural output growth.

Developing the agricultural sector of Ghana is not an easy task because farmers face various forms of risks including pest risk, production risk, government policy risk, price risk and most importantly financial risk (Komarek et al., Citation2020; Ullah et al., Citation2016). These risks generate uncertainty in the income made from the agricultural sector. Financial institutions play a crucial role in the agricultural sector of Ghana by providing financing for agricultural activities. Such financing include rotating savings, giving out loans, subsidies and credit (Sackey, Citation2018; Florence & Nathan, Citation2020). However, due to the high risk associated with Ghanaian farmers’ income, most financial institutions tend to limit loans and credit access by farmers and other organizations in the agricultural sector. Though these risks can be minimized, they cannot be eliminated. Therefore, what could be done to increase access to credit by farmers in Ghana is to develop strong financial institutions to contain these risks. Undertaking this initiative requires better insight into the link between financial development (FD) and agricultural sector growth, which the present study tries to fulfill.

According to the endogenous growth theory, growth can be sustained as long as the process of capital accumulation is not interrupted (Jones & Manuelli, Citation1990; Rebelo, Citation1991). Thus, various forms of capital such as credit, liquid liabilities, money supply, and others are imperative factors in attaining sustainable economic growth. FD is expected to affect agricultural growth via two basic channels. First, it shapes savings, accumulates funds and ensures easy access to credits and loans by poor farmers and other organization in the agricultural sector, leading to an increment of agricultural investment (Mckinnon, Citation1974). Second, it plays an intermediation role in taking funds from lenders to borrowers like farmers. Thus, an economy with an efficient financial system would ensure that funds are well mobilized and invested in vital sectors of the economy of which the agricultural sector is no exception. Hence, for efficient, sound and well-structured growth of the agricultural sector, the role of FD cannot be ignored.

In principle, financial development should spur agricultural growth. This is so because a well-developed financial sector would drive the non-financial (real) sector like the agricultural sector along the growth path, via the transfer of funds from surplus units to deficit units like farmers (Shahbaz et al., Citation2013). Specifically, farmers go to banks for long and medium-term loans which they use for various agricultural activities like leveling land for cultivation, clearing weeds and forests, creating terraces, and purchasing new farm machineries such as tractors, trailers, water pumps and others. While the short-term loans or credits are used for minor agricultural activities like purchasing seedlings, hiring farm workers, apiculture, sericulture and others, the long-term loans are often used for major agricultural activities like construction of models and culverts, purchasing of agricultural machinery such as lift pumps, turbines, bullocks, country-boats, forklifts, transport vehicles, bullock-carts and other (Ussif, Citation2017). Additionally, the use of modern technology such as bins and silos in cultivation is made possible through long-term loans or credit.

The above description shows that FD promotes agricultural growth which in turn fosters social and economic development to end extreme poverty. However, the existing literature has ignored providing better measures of FD while examining the link between FD and agricultural growth. For instance, Shahbaz et al. (Citation2013) showed that FD help farmers invest in innovative technologies which enhance agricultural productivity to accelerate agricultural growth, using per capita real loans disbursed to farmers by the financial sector as a proxy for FD. Singariya and Sinha (Citation2015) used the same FD proxy employed by Shahbaz et al. (Citation2013) and found a similar outcome for India. A subset of studies in this area of research has also provided evidence to support the positive link between FD and growth of the agricultural sector using numerous financial development indicators such as capital stock, real interest rate, agricultural credit and international trade (Florence & Nathan, Citation2020; Gong, Citation2018; Ngong et al., Citation2022; Vander Donckt et al., Citation2021). For instance, Florence and Nathan (Citation2020) found that agricultural growth in Uganda is enhanced by commercial Banks’ credit to the agricultural sector. Peng et al. (Citation2021) found similar evidence for China, using agricultural loans as a measure of FD. To the best of our knowledge, two studies have been conducted in Ghana. Both studies found evidence that FD has insignificant negative impact on growth of the agricultural sector, using different time series approaches. The study by Oteng-Abayie et al. (Citation2019) used credit to the private sector and money supply as measures of FD while that of Agbenyo et al. (Citation2019) used domestic credit to private sector a measure of FD. Our study does not criticize the use of these numerous FD indicators used in previous studies. However, the article aims at complementing these existing studies by using different measures of FD which have not been utilized in economic literature. Also, we employ composite measure of FD based on different indicators of FD, in line with previous studies (Adu et al., Citation2013, Jafarian & Sanaye-Pasand, Citation2010). This measure is important because it contains enough information needed to measure FD. The present study has at least two contributions to economic literature: (a) to introduce new financial development indicators (i.e. narrow money supply, net domestic credit per GDP, broad money supply, and ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP) and (b) examine the effect of FD on agricultural output growth, using three sub-indexes of FD created from PCA.

2. Review of literature and contribution of the study

Studies on the determinants of agricultural growth have unveiled that myriad factors affect agricultural output growth. However, these studies have received a consensus on a few factors in that regard. For instance, Ahmad and Heng (Citation2012) investigate the impact of human capital, fertilizer, agriculture credit distribution and area under crops (land) on agricultural growth in Pakistan. The study showed that fertilizer, human capital, and agricultural credit promote agricultural growth while area under crops hurts agricultural growth. This outcome is in line with that of Kakar et al. (Citation2016). However, for Kakar et al. (Citation2016) findings, area under cultivation foster agricultural output growth. One reason for this ambiguous outcome for areas under cultivation may due to the fact land productivity increases with the use of advance agricultural technology and modern materials/substance such as fertilizers just as the conventional theory of agriculture development predicted (Barrett et al., Citation2010). Additionally, Kakar et al. (Citation2016) further identified agricultural labour as additional determinant of agricultural growth but it had positive insignificant effects on agricultural productivity. This finding drives home the urgency of human capital development in the agricultural sector to boost agricultural output growth (Huffman, Citation2001).

In a recent study, Liu et al. (Citation2020) examine factors that drive agricultural productivity growth of 15 Asian countries. Consistent with other existing studies (Shita et al., Citation2018; Urgessa, Citation2015), the study found that scale change, pesticide use, fertilizer and technical efficiency change are among the main determinants of agricultural productivity. In a specific case country study, Muraya (Citation2017) examine determinants of agricultural productivity in Kenya. Estimates from their OLS technique show that government expenditure, annual rainfall and labour force exert a positive impact on agricultural productivity. Their finding regarding labour force was similar to that of Akmal et al. (Citation2012). In the same vain, Kumar and Sharma (Citation2013) also analyzed the impact of climate change on agricultural productivity in India. The study found that climate variations exert a significant adverse impact on grain crops.

The impact of FD on the agricultural sector has been well documented with numerous studies finding a strong positive relationship between FD and agricultural sector growth, using numerous proxies of financial development (Hye & Wizarat, Citation2011; Iwegbu & de Mattos, Citation2022; Parivash & Torkamani, Citation2008; Sharif et al., Citation2009). For instance, Sharif et al. (Citation2009) and Parivash and Torkamani (Citation2008) found that Iranian financial market plays significant role in stimulating agriculture growth. Similarly, Yazdani (Citation2008) examine the link between FD and agriculture growth in case of Iranian economy and found the same outcome. Raifu and Aminu (Citation2019) found a positive relationship between FD and agricultural sector performance in Nigeria while considering the role of institutions. The study found that financial development boost agricultural performance. Afangideh (Citation2009) also found similar result using two stages least square estimator. Fathi et al. (Citation2009) study revealed a long run positive relationship between FD while measuring FD with agricultural credit. In a related study, Hye and Wizarat (Citation2011) examined the impact of financial liberation on agriculture growth in Pakistan and found that financial liberalization improves agriculture sector growth in Pakistan.

Although the above studies on the link between FD and agricultural growth have shown that an improved financial system or institution promote agricultural growth, there have been some contradictory findings in the literature. For instance, some studies within this literature found that the link between agricultural growth and FD may be complex since it ranges from negative to U-shaped relationship. For instance. Zakaria et al. (Citation2019) show that FD exerts an inverted U-shaped effect on agricultural productivity. This implies that agricultural productivity rises initially as FD rises, but eventually falls as FD rises even more. This indicates that too little or too much spending is bad for agricultural development. Onoja (Citation2017) also used fixed-effects econometrics approach and found FD it is not a significant driver of agricultural productivity in the absence of quality institutions.

In Ghana, Oteng-Abayie et al. (Citation2019) used ARDL approach to examine the effect of FD on agriculture output. Money supply and credit to the private sector were used indicators of financial development while following the Cobb-Douglas production framework. Generally, the study found that financial development exerts insignificant negative effect on agriculture output growth. More surprisingly, the study found that agricultural capital exerts an adverse effect on agricultural value added, likely due to the low application of modern capital agricultural inputs in Ghana. Agbenyo et al. (Citation2019) fairly collaborated the findings of Oteng-Abayie et al. (Citation2019) by establishing an inverse relationship between domestic credit to private sector and agricultural growth in Ghana.

The present study contributions to literature in several ways. First, empirics on agricultural output and FD have presented mixed outcome regarding the impact of FD on agricultural growth, hence, there is a need to take a closer look at this relationship from a different perspective. Second, although studies on the relationship between economic growth and FD is in abundance in the extant literature, most of these empirics used varying measures of FD without necessarily paying much attention on other relevant FD indicators such as net domestic credit per GDP. Hence, this study explores these new FD indicators. Thirdly, FD can be well measured as a composite of possible large set of different financial indicators containing information from different FD indicators (Adu et al., Citation2013; Chandio et al., Citation2022). As a result, we build three new FD indexes which contains information from several FD indicators. This will ensure that FD is measured efficiently as compared to previous studies that used a single proxy for FD. Also, this measure of FD will help deepen our understanding on the relationship between agricultural growth and FD. Relatively speaking, this is the first country case study that makes use of composite of financial indexes to examine the link between FD and agricultural output growth in Ghana. So far, there are two studies in Ghana. However, these studies used aggregate money supply and credit to the private sector as financial development proxies. Therefore, our study goes beyond these studies to provide deeper insights in terms of how FD is measured. Fourth, the financial development proxies utilized in this study are selected based on banking sector development and financial assets, which are not commonly used among previous studies. Lastly, the findings of this study are relevant beyond Ghana’s boundary, especially for developing countries with similar demographic and socioeconomic settings like Ghana.

3. Specification of model and data

The study followed previous studies (Agbenyo et al., Citation2019; Buabeng et al., Citation2019; Kitenge & Bashir, Citation2022) and specify the effect of FD on agricultural output growth in a functional form as follows:

(1)

(1)

where AGRO is agricultural output growth measured by agriculture, forestry, and fishing value added as a % of GDP.

denotes annual rural population growth rate, FD captures financial development and V captures additional factors that affect agricultural output growth.

The estimable form of EquationEq. (1)(1)

(1) is thus specified in EquationEq. (2)

(2)

(2) .

(2)

(2)

where the variables

and

are explained earlier in EquationEq. (1)

(1)

(1) .

is the constant and

is the disturbance term. The parameters

s (i = 1, 2…, 5) are the coefficient of the respective variables.

comprises a vector of covariates including inflation measured by consumer price index (

fertilizer for agricultural use annually (FER), temperature change in degree Celsius (

and annual rainfall (RF). These control variables were utilized following previous studies (Enisan Akinlo, Citation2005; Kamara et al., Citation2019; Mcarthur & Mccord, Citation2017; Pingali, Citation2007).

captures various proxies used to measure financial development which includes money supply per GDP (

), net domestic credit as a ratio to

(

), monetary sector credit to private sector as a ratio to

(

) and ratio of liquid liabilities to

(

). We further decomposed money supply into narrow money per GDP (NM/GDP) and broad money per P (

).

Theoretically, FD is expected to positively impacts on agricultural output growth, however, some exiting studies have produced findings that contradicts theory. Based on theory and previous studies, we hypothesis the relationship between the various indicators of FD and agricultural output growth in the following manner. First, it is expected that both monetary sector credit to private sector and net domestic credit should have a positive relationship with agricultural output growth. The economic intuition behind this expectation is that availability and easy access to credit by farmers and other organizations in the agricultural sector enable them to meet their financial need. Thus, they may be able to acquire new agricultural machinery, modern technology, agricultural inputs and agricultural materials or substances such fertilizer needed for agricultural production. Thus, when monetary authorities can lend out more funds to the private sector (including the agricultural sector) via lowering central banks’ lending rate, it will increase borrowing and investment in the agricultural sector to enhance agricultural production. The relationship between ratio of liquid liabilities to and agricultural output growth is also expected to be positive. Liquid liabilities basically include cash and other illiquid assets of financial institutions which can be converted to cash easily. Hence, it is easily accessible and available on the financial market. It forms a significant part of the total asset of financial institutions and thus reflect the size most financial institutions. Therefore, it is expected that as the size of the liquid liabilities of a financial institution increases, agricultural output growth also increases because more cash and other illiquid asset will be made available on the financial market for borrowers including farmers and other agricultural organizations. Lastly, evidence from Ogunmuyiwa and Ekone (Citation2010) suggest that money supply exerts a positive impact on growth via increasing inflow of FDI. On this empirical basis, we expect a positive relationship between agricultural output growth and broad as well as narrow money because FDI have been shown to be one of the main channels for transfer of modern technology and managerial skill that are needed for agricultural production.

The study used time series data covering the period of 1970 to 2017 from different sources including World Development Indicators of World bank database, World Bank Group Climate Change Knowledge database, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations database and World Economic Outlook (IMF) database.

4. Methodology

Here, we discuss the main estimation strategy employed in this study.

4.1. Stationarity test

We first examine the stationarity properties of the variables using Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) approach by Dickey and Fuller (Citation1979). We tested the stationarity properties because using non-stationary variables in time series analysis leads to spurious regression estimates, yielding wrong inferences. Thus, time series’ stationarity is relevant because non-stationary time series can exhibit correlation even in large sample, resulting in spurious regressions (Yule, Citation1926). To make the error term white noise in the ADF test, the lags of the first difference are used in the regression equation. In essence, the ADF test necessitates the estimation of an equation of the form:

(3)

(3)

where Δ

is the first difference of the dependent variable,

defines time trend variable, Δ is the first difference operator,

is the error term,

is the optimal lag length of each variable. We also used the Phillips and Perron (PP) unit root test by Phillips and Perron (Citation1988) as robust check to our stationarity test results.

4.2. ARDL model

The paper uses Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) ARDL as the main estimation strategy. This approach is suitable because the data span for this study is relatively shorter (Ghatak & Siddiki, Citation2001). The ARDL can be applied regardless of the order of integration of the underlying variable. Thus, the approach does restrict the order of integration, indicating that approach can be applied regardless to variables having the same or mix order of co-integration. Further, the ARDL model can deal with bias estimates resulting from endogeneity. The approach is also effective in producing both long run and short-run elasticities with relatively small sample size. To examine the effect financial development on agricultural growth, we estimate the following ARDL model specified below:

(4)

(4)

where Δ is the first difference operator.

to

denote the short run dynamic while δ1 to δ5 represent the multipliers in the long run, the number of lags is represented by β,

η, λ and

whiles εt is white noise disturbance term.

Next, we use the ARDL bound test procedure to examine the long run relationship among the variables (Pesaran & Smith, Citation1995) by testing following the hypotheses:

H0 = δ1 = δ2 = δ3= δ4= δ5 = 0; (This suggests no co-integration. Thus, no long run relationship exists between the variables).

H1 = δ1 ≠ δ2 ≠ δ3 ≠ δ4≠ δ5 ≠ 0 (This suggests co-integration or long run relationship between the variables).

Based on the estimated F-statistic, these hypotheses are tested. If the F-statistics is greater upper critical values (5 and 10%), the null hypothesis of no long-run relationship is rejected, otherwise it is not rejected (Pesaran & Smith, Citation1995). The optimal lag length is selected based on Akaike information criteria (AIC).

To examine the long-run effect of FD on agricultural output growth, the following long-run coefficient of the ARDL specified below was estimated:

(5)

(5)

where

is the constant and

is the white noise error term. All the variables and parameters are same as previous equations.

After obtaining the long run results, the following ARDL model was estimated in order to investigate the short-run dynamics:

(5)

(5)

where

is the constant,

is the error term and

is the parameter for the error corrrection model. All the variables and parameters are same as previously equations. The

is the error correction term and δ represents the speed of adjustment.

5. Results

The results in this section are presented in the following sequential order. First, the study presents the results for correlation analysis. Next, we used PCA to cluster three new sub-indexes of financial development. We then examine the time series properties of all the variables. Next, we followed the ARDL bound test approach to examine long run relationship among the variables. Lastly, we present long run and short run dynamic ARDL results.

5.1. Correlation analysis

reports the results for correlation among the various proxies of FD. The results suggest that there is high correlation among the various proxies of financial development. For example, the correlation coefficient for net domestic credit per GDP and monetary sector credit

is 0.901 which depicts a high positive correlation between these two variables. In essence, a correlation coefficient above 0.5 or −0.5 shows strong positive or negative correlation and it can be observed from the results displayed in that all the correlation coefficients reported are indeed greater than 0.5, implying high correlation among the proxies of FD. The strong correlation among the financial development proxies provide a strong econometric basis that the inclusion of two or more FD proxies might generate spurious regression results. To be able to put more than one financial development proxy in a single equation, we used the PCA to create three new indexes of FD indictors. The PCA analysis is presented in the next section.

Table 1. Pearson correlation coefficient results for the indicators of financial development.

5.2. Principal component analysis (PCA) as robustness check

In this section, we used PCA to create three sub-indexes of FD using the six proxies of FD. These three indexes that we created are made from different financial development indicators. presents the results of the principal component analysis based on the three FD. The first three components explained approximately 95% variation in the original data. This implies that the study has been able to reduce the dimensions of the FD indicators by more than half while preserving 95% of the information in our data. Further, we can include the three indexes in a single equation since indexes are orthogonal to each other. The first index ( explain approximately 56% variation in the data. We followed existing studies and used scoring coefficient of 0.3 and higher to determine the significance factor score (Adu et al., Citation2013; Jafarian & Sanaye-Pasand, Citation2010). Using this factor score, the first component could reflect the variables

and

and

had low scoring coefficients (0.168 and −0.041, respectively), hence, treated as insignificant (see ). The second (

and third indexes (

also explained about 23 and 16% variance in the data, respectively. Following the above coefficient scoring criteria, the second index (

denotes

and

while third index (

denotes

and

as shown in .

Table 2. Principal component of financial development indicator.

Table 3. Scoring coefficient of the various proxies of financial development.

5.3. Unit root test results

In , we employed the ADF and PP tests to examine the stationarity properties of the variables. The results show that all the first and third FD indexes attained stationarity at level while the second index attained stationarity at first difference for both tests. For the rest of the variables, we find that agricultural output growth, net domestic credit, monetary sector credit to private sector, ratio of liquid liabilities, rural population growth, rainfall, and fertilizer for agricultural use attained stationarity at their first difference [I(1)]. However, broad money supply, narrow money supply, inflation and temperature were stationary at their levels [I(0)]. This suggests that variables are a mixture of I(1) and I(0) series and thus ARDL model is a suitable approach.

Table 4. Unit root estimates.

5.4. Co-integration bound test results

In this section, we aim to test for the existence of co-integration among the variables based on the six FD indicators. We estimate eight different models. Out of the eight specifications, one had no co-integration. Specifically, we found no co-integration among the variables when money supply (M2+) is use as a proxy for FD. Hence, we drop this variable out of the six financial indicators, leaving us with eight specifications as shown in . Lastly, we include all the indexes of financial development we created in a single equation to test for co-integration. This is allowed because the financial development indexes are orthogonal to each other. To allow for sufficient degree of freedom, we vary the covariates for each model. In model 6 we dropped temperature from the equation, dropped rural population and fertilizer used in model 7 and dropped rainfall in model 6. The variation in critical value depends independent variables available in a particular model. Hence, most of the models have the same critical values because they have equal independent variables. Overall, the results in revealed that all the F-statistics values for all the eight alternative models exceeds all the upper bound critical values at 1 and 5% level of significance, indicating that the variables are co-integrated.

Table 5. Bounds test estimates for cointegration.

5.5. ARDL results

presents the long run results for the effect of FD on agricultural output growth based six different models. In model (1a), we find that net domestic credit exerts a negative effect on agricultural output growth. Precisely, 1% increase in net domestic credit leads to approximately 0.22% decrease in agricultural output growth. This outcome is contrary to empirical expectation and invalidates the finance-led growth hypothesis. However, it provides evidence in support of our earlier argument that the agricultural sector in Ghana may have very limited access to long-term and cheaper financing. Significant proportion of credit available on the financial market might be skewed in favour of the wealthiest individuals and the largest firms (Fowowe, Citation2020). Hence, rural poor agricultural farmers in Ghana may not have easy access to credit to support agricultural activities. Thus, lack of access to long term finance hampers agriculture sector development in Ghana. Long-term lending constitutes a very small proportion of the total bank loan portfolio vis-à-vis the long-term finance composition in developed and other emerging economies. In the United Kingdom and Germany for example, loans with maturity of more than 5 years comprise over 45% of loan portfolio (all domestic banks with assets above $5 billion) whereas in Ghana, loans with similar maturity constitute just 15% of the banks’ loan portfolio. This can also be evidenced from the average loan maturity 4.2% in developed markets and 2.8% in emerging markets whereas in Ghana it is 2.3. Lack of an active capital market, provision of only short-term deposits that lead to asset liability management bottlenecks, and low savings rate act as potential hurdles in long-term lending. Coupled with the challenge of inadequate long-term financing in the economy, the risky perception of sectors like agriculture and manufacturing act as a deterrent in advancing loans to these sectors. None of the agricultural and manufacturing subsectors feature in the top receivers of credit in 2018. Agriculture was the most underserved sector as far as credit disbursement is concerned, receiving only 4.2% of the total share. This finding is consistent with Agbenyo et al. (Citation2019) finding and supports Onoja et al. (Citation2017) discovery that financial sector is unable to driver growth in the absence of quality and well-functioning institutions.

Table 6. Long run effect of financial development on agricultural output growth.

Our results in in model (2a) show that monetary sector credit to the private sector exerts a positive and significant effect on agricultural output growth as anticipated based on empirics. The elasticity coefficient on this proxy of FD is 0.81, implying that a percentage increase in monetary sector credit to the private sector causes nearly 0.81% increase in agricultural output growth. Our finding is in line with Schumpeter and Backhaus (Citation2003) finance-led growth hypothesis. One possible justification for the positive effect of monetary sector credit to the private sector on agricultural output growth could be due to the fact that most of the agricultural activities in Ghana are done by individuals, suggesting that the agricultural sector is part of the private sector. Indeed, it form significant proportion of it, hence, increasing credit access to private sector may increase access to credit to farmers and other private agricultural organizations. This could increase investment in the agricultural sector to accelerate agricultural production in Ghana. Our finding is consistent with findings from Akmal et al. (Citation2012) but contradict that of Oteng-Abayie et al. (Citation2019) and Zakaria et al. (Citation2019).

In model (3a), liquid liabilities exert a negative impact on agricultural output growth. Precisely, 1% increase liquid liabilities generates 0.41% decrease in agricultural output growth in Ghana, ceteris paribus. Although this result deviates from what we expected, is not entirely unexpected since “availability is not accessibility,” and Ghana’s agricultural sector is plagued by inefficiencies, making it unable to attract a significant portion of credit needed to increase agricultural activities (Ussif, Citation2017). Thus, most of the farmer in Ghana do not have access to long-term loans for agricultural activities, likely due to loan default and lack collateral security among farmers (Afolabi, Citation2010). As such, credit and loans might be available on the financial market in Ghana but farmers are unable to get access. This finding is consistent with existing studies by Agbenyo et al. (Citation2019) but contradict that of Akmal et al. (Citation2012).

Although both narrow money and broad money exert positive effect on agricultural output, the effect is not significant in models (4a) and (5a) of . This implies that money in circulation, in the hands of the public and other illiquid forms of money such as bond and stock does not promote agricultural growth in Ghana since significant proportion of these assets or monies are held by rich individuals. Unfortunately, significant proportion of farmers in Ghana are among the poor group who hold only a small fraction of money in circulation. Hence, it is not surprising that we found these results in Ghana. The three FD indexes exert a positive effect on agricultural outputs in models (6a), (7a) and (8a). Precisely, the coefficients of the three indexes are 0.450, 0.182 and 0.818 which suggests that 1% increase in any of the three FD indexes generate 0.45, 0.18 and 0.82% increase in agricultural output, respectively.

The first index (FDIIndex1) revealed that the combined impact of net domestic product, money supply, and credit to the private sector and liquid liabilities on agricultural output is positive and significant. This is one of the novels of this study, which implies that the mix outcome in empirical literature that examined the link between FD and agricultural output growth maybe as a result of the choice of financial development indicator. Thus, the link between FD and agricultural output depends on the choice of FD indicator. Further, the finding also suggests that in devising policies to develop the financial sector to boost agricultural growth, equal attention, effort and resource should be given to the development various subsectors or component of the financial sector because these indexes contains information from various proxies of financial sector, capturing different dimension of FD.

Regarding the covariates, we found a negative a link between inflation and agricultural output. This outcome support theory that a high inflation rate is considered to be harmful to growth of the agricultural sector since it increases inputs. This outcome is in line with that of Mekonen (Citation2020). Our results also suggest that, in the long-run, rainfall exerts a positive effect on agricultural output, all things been equal. This result contradict that of Phiri (Citation2018) since he argued that too much rainfall could damage seedlings, crops, and destroy shelters for livestock. As expected, we found that a significant positive relationship between fertilizer for agriculture use and agricultural output. This outcome is consistent with priori expectation and support empirical findings from Ahmad and Heng (Citation2012). Temperature change exerts a positive and significant effect on agricultural output. It can be inferred from this result that the temperature dynamics in Ghana is conducive and optimal for agricultural activities, hence, promotes agricultural growth. The positive relationship between agricultural output growth and temperature change gainsays finding by Rasul et al. (Citation2011) but affirms Peprah (Citation2012) finding. Rural population proved to be a robust determinant of long run agricultural output in Ghana since it also had a positive and significant effect on agricultural output growth. In all the alternative specification, rural population exerts a positive effect on agricultural output. In all the models (1a–8a), rural population (proxy for labour force) exerts a positive impact on agricultural output.

presents the short-run results for the effect of FD on agricultural output growth. Across columns (2a–8a) the effect of various indicators of FD on agricultural output growth is positive but many variables were not statistically significant. Specifically, in column (la) net domestic credit exerts a significant negative effect of about 0.085 on agricultural output whereas in column (3a) liquid liabilities to GDP exerts an insignificant negative effect of about 0.085 and 0.079 on agricultural output growth, respectively. Also, columns (2a), and (4a) monetary sector credit to the private sector and narrow money exert an insignificant positive impact of about 0.095 and 0.049 on agricultural output growth whereas in column (5a) broad money exerts a positive effect of about 0.019 on agricultural output at 10% level of significance. All the alternative FD indexes exert a positive effect on agricultural output in models (6a), (7a) and (8a), respectively. For example, the coefficients of the three indexes in model (6a) are 0.050, 0.182 and 0.071 which imply that 1% increase in any of the three FD indexes we created from PCA generate an insignificant positive effect of about 0.45, 0.050, 0.182 and 0.071% increase in agricultural output growth, respectively. Comparing these results with the long-run results, it is observe that whereas the long-run coefficients of various measures of FD are statistically significant, most of short run coefficient are not statistically significant. Thus, in the short-run the effect of FD on agricultural growth is not statistically significant for some measure of FD. Also, the long run estimates are higher than that of the short run estimates in term of magnitude, however, their signs do not change. This outcome is expected because agricultural production follow seasons or cyclical process which occurs in the long run (months or years). Thus, most crops and animal production in the agricultural sector occurs in a long run, hence, it is not surprising that the effect of FD is insignificant in the short-run. As a result, the short run results may not carry any economic intuition because most agricultural production occurs in the long run.

Table 7. Short-run ARDL results.

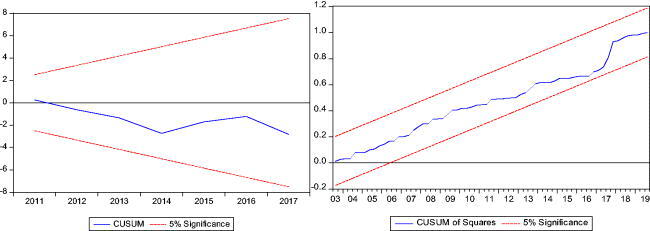

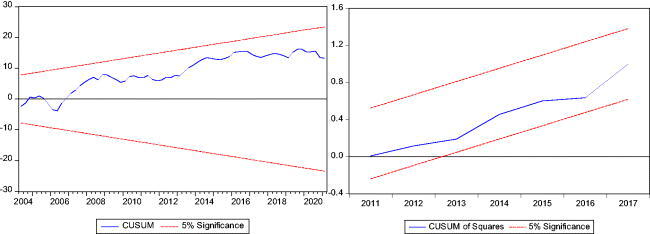

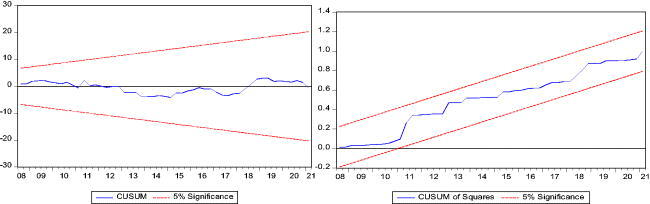

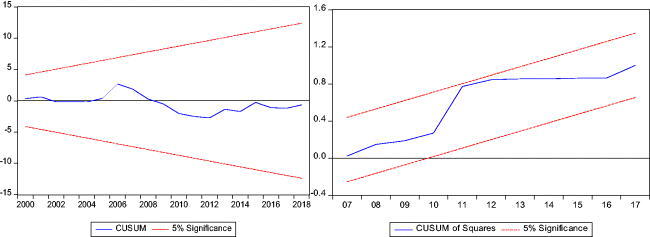

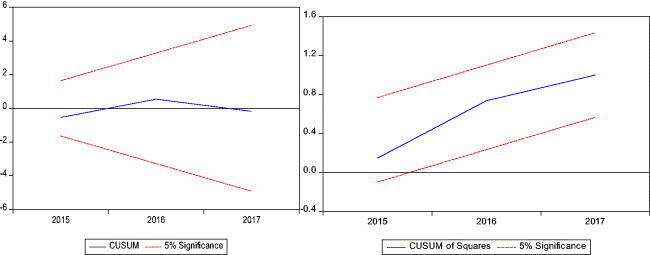

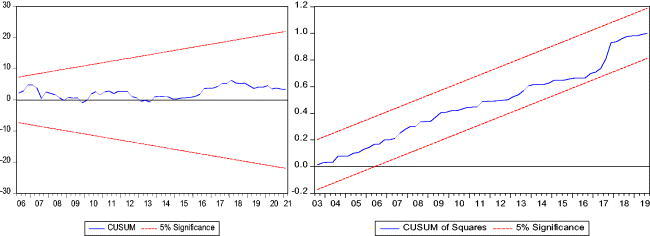

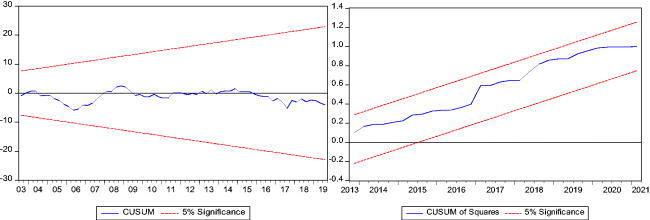

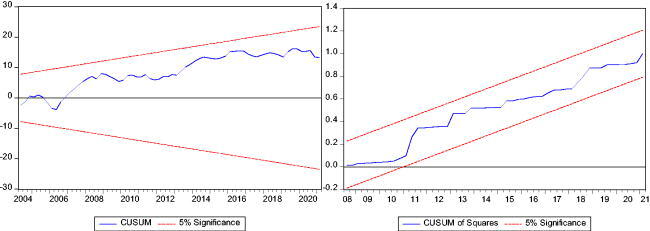

In this section, we consider several reliability and diagnostic checks to ensure that the ARDL estimates are not biased by econometric issues. These test results are reported in . The results show that the ARDL results are free from heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, functional form and it is also normally distributed because all the probability values reported in parentheses are greater than 0.05. Also, the cumulative sum (CUSUM) and cumulative sum of square CUSUMQ (see Appendix) show that agricultural output growth in the exact time period is stable because the CUSUM and CUSUMQ lies within the 5% critical limit.

Table 8. Reliability and diagnostic tests.

6. Robustness check

In this section, our aim is to provide a robustness check to the results by utilizing an alternative long-run estimation strategy. Specifically, we consider the robustness of our long-run ARDL results for the effect of financial development on agricultural output growth to an alternative estimation strategy, namely, fully modified ordinary least square (FM-OLS). reports the long run effect of FD on agricultural output growth using FM-OLS approach. The results are in line with the long run ARDL results in terms of signs but their magnitudes or coefficients changes. Specifically, the results in column (a) of show that 1% increase in net domestic credit causes about 0.31% decrease in agricultural output growth in Ghana, ceteris paribus. For credit to the private sector, the results displayed in column (2a) reveal that a percentage increase in credit to the private sector causes nearly 0.510% increase in agricultural output growth, all else equal. In column (3a) it is observe that 1% increase in liquid liabilities to GDP leads to about 0.372% decrease in agricultural output growth in the long run, all else equal. The FM-OLS results for narrow money and broad money reported in column (4a) and (5a) provide evidence that narrow and broad money exerts an insignificant effect of nearly 0.199 and 0.122 on agricultural output, respectively, suggesting that changes in money supply may have no implication for agricultural growth in Ghana. Consistent with the ARDL long run results, all the FD indexes exert a positive effect on agricultural output growth in columns (6a), (7a) and (8a). For instance, coefficients of the three FD indexes in column (6a) are 0.225, 0.401, and 0.511, suggesting that 1% increase in any of the three FD indexes we created using different indicators of FD generate about 0.225, 0.401 and 0.511% increase in agricultural output growth, respectively.

Table 9. Effect of financial development on agricultural output growth using FMOLS.

7. Concluding remarks

The study examined the long run impact of FD on agricultural output growth using six alternative indicators of FD. High correlation among the six proxies of financial development do not allow us to estimate the effect FD on agricultural output growth while putting all the six financial development indicators in single empirical equation. To overcome this problem, we used the principal component analysis to create three new financial development sub-indexes. The major implication of our finding is that agricultural output growth effect responses differently to the six FD proxies. For instance, employing net domestic credit and liquid liabilities to GDP as an indicator for FD, we found a negative and significant effect of financial development on agricultural output growth. However, for monetary sector credit to the financial sector, broad money and narrow money, the effect is positive although that of broad money and narrow money were not statistically significant. The three new FD indexes that we created using PCA also confirm a positive effect of FD on agricultural output growth. These findings help us to understand three issues. First, it implies that an improved and well-functioning financial institution and financial market spurs agricultural growth since all the new financial development indexes exert a positive effect on agricultural output growth. Secondly, the findings imply that equal attention, effort and resource should be given to the development of various subsectors or component of the financial sector when devising policies aim at improving financial development to foster the growth of the agricultural sector. This is because the indexes of FD contain information from various proxies of financial sector, capturing different dimensions of FD.

Our findings suggest that policy interventions that aim at improving agricultural output growth should pay much attention to choice FD indicator as a policy instrument in the design, and formulation of agricultural growth policies. Specifically, we recommend that policy intervention that improves the ease at which the agricultural, small and medium enterprises get access to credit would increase agricultural activities via increase in employment, investment in the agricultural sector, use of modern technology, innovation and increase in agricultural labour productivity. Further, our findings suggest that expansionary monetary policy (excess money supply specifically) may impede agricultural growth, likely due to the inability of farmers to have access to significant proportion of money in circulation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

World Development Indicators: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators. WorldBankGroupClimateChangeKnowledgePortal:https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/download-data. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data. World Economic Outlook (IMF): https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Opoku Adabor

Opoku Adabor holds B.A and Master’s in economics from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science (KNUST). He is currently a PhD student at RMIT University, Australia. He has worked as graduate research assistant at KNUST and RMIT University. His research interest includes macroeconomics, child health, poverty, development economics and economic policy analysis.

Michael Essah

Micheal Essah is a teaching and research assistant at Department of Economics, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi-Ghana. He received B.A in economics from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). His research interest includes microeconomics, macroeconomics economic analysis and financial economics.

References

- Adu, G., Marbuah, G., & Mensah, J. T. (2013). Financial development and economic growth in Ghana: Does the measure of financial development matter? Review of Development Finance, 3(4), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2013.11.001

- Afangideh, U. J. (2009). Financial development and agricultural investment in Nigeria: Historical simulation approach. West African Journal of Economic and Monetary Integration, 9.

- Afolabi, J. (2010). Analysis of loan repayment among small scale farmers in Oyo State, Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences, 22(2), 115–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2010.11892791

- Agbenyo, W., Jiang, Y., & Antony, S. (2019). Cointegration analysis of agricultural growth and financial inclusion in Ghana. Theoretical Economics Letters, 09(04), 895–911. https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2019.94058

- Ahmad, K., & Heng, A. C. T. (2012). Determinants of agriculture productivity growth in Pakistan. International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 95, 163–173.

- Akmal, N., Rehman, B., Ali, A., & Shah, H. (2012). The impact of agriculture credit on growth in Pakistan. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Rural Development, 2, 579–583.

- Barrett, C. B., Bellemare, M. F., & Hou, J. Y. (2010). Reconsidering conventional explanations of the inverse productivity–size relationship. World Development, 38(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.002

- Buabeng, E., Adabor, O., & Ohene-Poku, N. K. (2019). Determinants of savings habits among cocoa farmers in Ghana: A case study of Atwima Nwabiagya District of the Ashanti Region. African Journal of Sustainable Development, 9, 1–23.

- Chandio, A. A., Jiang, Y., Abbas, Q., Amin, A., & Mohsin, M. (2022). Does financial development enhance agricultural production in the long‐run? Evidence from China. Journal of Public Affairs, 22(2), e2342.

- Dhrifi, A. (2014). Financial development and agricultural productivity: Evidence from African Countries. International Center for Business Research, 3, 1–9.

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/2286348

- Easterly, W. (2019). Ghana-The National Agricultural Research Project, the National Agricultural Extension Project, the National Livestock Services Project, the Agricultural Diversification Project, and the Agricultural Sector Investment Project (sector overview).

- Enisan Akinlo, A. (2005). Impact of macroeconomic factors on total factor productivity in Sub-Saharan African countries WIDER Research Paper.

- Fathi, F., Zibaei, M., & Tarazkar, M. H. (2009). Financial development and agricultural growth. Agricultural Economics, 3, 57–71.

- Florence, N., & Nathan, S. (2020). The effect of commercial banks’ agricultural credit on agricultural growth in Uganda. African Journal of Economic Review, 8, 162–175.

- Fowowe, B. (2020). The effects of financial inclusion on agricultural productivity in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Development, 22(1), 61–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JED-11-2019-0059

- Fuglie, K., & Rada, N. (2013). Growth in global agricultural productivity: an update.

- Ghatak, S., & Siddiki, J. U. (2001). The use of the ARDL approach in estimating virtual exchange rates in India. Journal of Applied Statistics, 28(5), 573–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/02664760120047906

- Gong, B. (2018). The impact of public expenditure and international trade on agricultural productivity in China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(15), 3438–3453. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1437542

- Huffman, W. E. (2001). Human capital: Education and agriculture. Handbook of Agricultural Economics, 1, 333–381.

- Hye, Q. M. A., & Wizarat, S. (2011). Impact of financial liberalization on agricultural growth: A case study of Pakistan. China Agricultural Economic Review.

- Iwegbu, O., & de Mattos, L. B. (2022). Financial development, trade globalisation and agricultural output performance among BRICS and WAMZ member countries. SN Business & Economics, 2(8), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-022-00271-w

- Jafarian, P., & Sanaye-Pasand, M. (2010). A traveling-wave-based protection technique using wavelet/PCA analysis. IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, 25(2), 588–599. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRD.2009.2037819

- Jones, L. E., & Manuelli, R. (1990). A convex model of equilibrium growth: Theory and policy implications. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5, Part 1), 1008–1038. https://doi.org/10.1086/261717

- Kakar, M., Kiani, A., & Baig, A. (2016). Determinants of agricultural productivity: Empirical evidence from Pakistan’s economy. Global Economics Review, I(I), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.31703/ger.2016(I-I).01

- Kamara, A., Conteh, A., Rhodes, E. R., & Cooke, R. A. (2019). The relevance of smallholder farming to African agricultural growth and development. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development, 19(01), 14043–14065. https://doi.org/10.18697/ajfand.84.BLFB1010

- Kang, J., & Zhao, M. (2022). The impact of financial development on agricultural enterprises in central China based on vector autoregressive model. Security and Communication Networks, 2022, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5629202

- Kitenge, E., & Bashir, S. (2022). The effect of financial access on convergence: Evidence from the US agricultural sector. Applied Economics, 54(15), 1715–1726. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2021.1980495

- Komarek, A. M., De Pinto, A., & Smith, V. H. (2020). A review of types of risks in agriculture: What we know and what we need to know. Agricultural Systems, 178, 102738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2019.102738

- Kumar, A., & Sharma, P. (2013). Impact of climate variation on agricultural productivity and food security in rural India. Economics Discussion Papers.

- Liu, J., Wang, M., Yang, L., Rahman, S., & Sriboonchitta, S. (2020). Agricultural productivity growth and its determinants in south and Southeast Asian countries. Sustainability, 12(12), 4981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124981

- Mcarthur, J. W., & Mccord, G. C. (2017). Fertilizing growth: Agricultural inputs and their effects in economic development. Journal of Development Economics, 127, 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.02.007

- Mckinnon, R. I. (1974). Money, growth, and the propensity to save: An iconoclastic view. Trade, Stability, and Macroeconomics. Elsevier.

- Mekonen, E. K. (2020). Agriculture sector growth and inflation in Ethiopia: Evidence from autoregressive distributed lag model. Open Journal of Business and Management, 08(06), 2355–2370. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2020.86145

- Muraya, B. W. (2017). Determinants of agricultural productivity in Kenya.

- Ngong, C. A., Thaddeus, K. J., Asah, L. T., Ibe, G. I., & Onwumere, J. U. J. (2022). Stock market development and agricultural growth of emerging economies in Africa. Journal of Capital Markets Studies, 6(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCMS-12-2021-0038

- Ogunmuyiwa, M., & Ekone, A. F. (2010). Money supply-economic growth nexus in Nigeria. Journal of Social Sciences, 22(3), 199–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2010.11892802

- Onoja, J. J. (2017). Financial sector development and agricultural productivity.

- Onoja, B. I., Okodua, H., & Akhigbemidu, S. A. (2017). Openness, Institutions and Financial Development in ECOWAS countries.

- Oteng-Abayie, E. F., Yusif, H. M., & Ussif, A. A. (2019). Empirical evidence on Financial Development and Agriculture Output Growth in Ghana.

- Parivash, G., & Torkamani, J. (2008). Effects of financial markets development on growth of agriculture sector. American-Eurasian Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, 2, 165–166.

- Peng, Y., Latief, R., & Zhou, Y. (2021). The relationship between agricultural credit, regional agricultural growth, and economic development: The role of rural commercial banks in Jiangsu, China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 57(7), 1878–1889.

- Peprah, K. (2012). Rainfall and temperature correlation with crop yield: The case of Asunafo forest.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. (1995). Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 79–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01644-F

- Phillips, P. C., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.2307/2336182

- Phiri, S. (2018). Determinants of agricultural productivity in Malawi.

- Pingali, P. (2007). Agricultural growth and economic development: A view through the globalization lens. Agricultural Economics, 37(s1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2007.00231.x

- Raifu, I. A., & Aminu, A. (2019). Financial development and agricultural performance in Nigeria: What role do institutions play? Agricultural Finance Review, 80(2), 231–254. https://doi.org/10.1108/AFR-06-2018-0045

- Rasul, G., Chaudhry, Q., Mahmood, A., & Hyder, K. (2011). Effect of temperature rise on crop growth and productivity. Pakistan Journal of Meteorology, 8, 53–62.

- Rebelo, S. (1991). Long-run policy analysis and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 500–521. https://doi.org/10.1086/261764

- Sackey, H. A. (2018). Rural non-farm employment in Ghana in an era of structural transformation: prevalence, determinants, and implications for well-being. Journal of Rural and Community Development, 13(3).

- Schumpeter, J., & Backhaus, U. (2003). The theory of economic development. Springer.

- Shahbaz, M., Shabbir, M. S., & Butt, M. S. (2013). Effect of financial development on agricultural growth in Pakistan: New extensions from bounds test to level relationships and Granger causality tests. International Journal of Social Economics, 40(8), 707–728. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-01-2012-0002

- Sharif, S. J. S., Salehi, M., & Alipour, M. (2009). Financial markets barriers’ in agricultural sector: Empirical evidence of Iran. Journal of Sustainable Development, 2(3), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v2n3p95

- Shita, A., Kumar, N., & Singh, S. (2018). Determinants of agricultural productivity in Ethiopia: ARDL approach. The Indian Economic Journal, 66(3-4), 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019466220941418

- Singariya, M., & Sinha, N. (2015). Relationships among per capita GDP, agriculture and manufacturing sectors in India. Journal of Finance and Economics, 3, 36–43.

- Ullah, R., Shivakoti, G. P., Kamran, A., & Zulfiqar, F. (2016). Farmers versus nature: Managing disaster risks at farm level. Natural Hazards, 82(3), 1931–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2278-0

- Urgessa, T. (2015). The determinants of agricultural productivity and rural household income in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Economics, 24, 63–91.

- Ussif, A.-A. (2017). Financial Development and Agricultural Sector in Ghana: An Econometric Analysis.

- Vander Donckt, M., Chan, P., & Silvestrini, A. (2021). A new global database on agriculture investment and capital stock. Food Policy, 100, 101961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101961

- Wood, T. N. (2013). Agricultural development in the northern savannah of Ghana.

- World Bank. (2018). The World Bank Annual Report 2018. The World Bank.

- World Bank. (2019). World development indicators 2019. World Bank.

- Yazdani, S. (2008). Financial market development and agricultural economic growth in Iran. American-Eurasian Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 2, 338–343.

- Yule, G. U. (1926). Why do we sometimes get nonsense-correlations between Time-Series?–a study in sampling and the nature of time-series. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 89(1), 1–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/2341482

- Zakaria, M., Jun, W., & Khan, M. F. (2019). Impact of financial development on agricultural productivity in South Asia. Agricultural Economics (Zemědělská Ekonomika), 65(5), 232–239. https://doi.org/10.17221/199/2018-AGRICECON

Appendix

Model 1a

Model 2a

Model 3a

Model 4a

Model 5a

Model 6a

Model 7a

Model 8a

.

.