ABSTRACT

Africa is experiencing a period of rapid economic growth, booming population, and migration as biodiversity is deteriorating and the climate is warming. Together, these represent grand societal and environmental challenges. The African Union and the United Nations both promote sustainable development, in which society and nature flourish as the economy progresses. However, achieving this goal is not self-evident. We discuss the concept of regenerative economy and propose it as a path forward for the African context. We identify three levers of action evident in Africa that promote the idea of regenerative economy: clean innovation in technology and business models, leapfrogging through decentralized communication and energy systems, and leveraging African values of horizontal collectivism. We present some case examples of how this can and does work but highlight that achieving regenerative economy en masse depends on scaling up business models, effective governance structures, and capacity building in Africa. If implemented correctly, regenerative economy can offer pathways to a future-ready, sustainable Africa.

Introduction

In an era of rapid economic growth and global climate change now and in the future, Africa’s development is confronted with a plethora of grand social and environmental challenges. Aspirations for sustainable development in Africa have transpired not only via the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’s “plan of action for people, planet, and prosperity” (United Nations, Citation2015), but also in the African Union’s Agenda 2063 that desires “a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development” (African Union, Citation2015). But, exactly how the continent will develop economically, while alleviating social and environmental harms, is rarely deliberated.

Addressing social and environmental grand challenges is a very real topic for Africa. The anticipated population boom and mass urbanization mean a growing workforce and economy, and a concomitant demand for food, water, energy, and infrastructure. In combination with a warming world that is exacerbating biodiversity loss, Africans can expect more pollution, impacts on health and well-being, and climate- and other-related migration of people. Africa’s wealth in both renewable and non-renewable natural resources is substantial and critical for a world transitioning towards sustainability – but the benefits thereof land (too) often in the hands of non-Africans. Saddled with a history of colonialism (e.g., Kieh, Citation2009), Africa has been left a legacy of institutional voids (e.g., Luiz & Ruplal, Citation2013), political instability (e.g., Dalyop, Citation2019), infrastructure gaps (e.g., Foster & Briceno-Garmendia, Citation2010; Goodfellow, Citation2020), income disparities (Wisevoter, Citation2023), and vested interests (e.g., Raleigh & Wigmore-Shepherd, Citation2022) that impact the continent’s ability to flourish.

Political economy aside, there are opportunities for sustainable development in Africa through business solutions, in particular, regenerative economy approaches. Regenerative economy emphasizes the pursuit of net-positive impacts by restoring and regenerating environmental, social, and economic systems simultaneously. To do so, growth in the economy and human well-being are disconnected from dependence on resource use and nature through absolute and relative decoupling. This paradigmatic shift is well suited to the African context because of the opportunities for clean innovation of technology and business models in the continent, decentralization of energy and communication infrastructure that allows Africa to avoid the mistakes of the global North by leapfrogging, and African horizontal collectivistic values.

We propose that regenerative economy is a possible pathway for sustainable development in Africa that is inclusive, collaborative, and co-created, creating value for societal stakeholders and nature. To that end, we discuss first what we mean by regenerative economy, why it is relevant for Africa, how it can be achieved, and then provide some examples of African cases. While challenges such as scaling up, governance, and capacity building remain, adopting regenerative economy approaches may help to shape a sustainable Africa.

Regenerative Economy as a Possible Pathway for Africa

Sustainable development, defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” in the so-called Brundtland Report (United Nations, Citation1987) requires future generations to have access to natural resources and flourish socially which can only be successfully achieved if we move away from traditional business models (Ehrenfeld & Hoffmann, Citation2013). In particular, the Brundtland Report prioritized the essential needs of the world’s poor and the ideas of limits to growth to industrial activity, technology, and society.

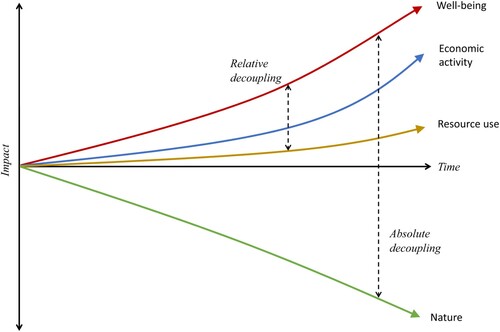

Africa is positioned for growth. The Agenda 2063 of the African Union aims to achieve a prosperous, united, and peaceful continent and global partner, whose development is people-driven beyond mere economic growth by engaging in “positive socioeconomic transformation” (African Union, Citation2015; DeGhetto et al., Citation2016). Economies, development, and governance systems in Africa have evolved tremendously in the last decade (Signé & Gurib-Fakim, Citation2019). However, for Africa to develop sustainably, societal well-being and economic growth must be disconnected from resource use and environmental impact, a concept visualized by UNEP (adapted from the International Resource Panel (IRP), Citation2017 and UNEP, Citation2011). The underlying idea of is that social well-being and economic activity can (continue to) rise while growth in resource use slows down and pressure on nature is not only reduced but also reversed. To achieve this, three types of decoupling must take place that decouple well-being and economic activity from resource use, and economic activity from (negative) impacts on nature. Importantly, social well-being and economic activity decoupling can be relative when it comes to resource use, but must be absolute from nature (IRP, Citation2017). Implicit is the notion that nature must be restored and regenerated (as seen in the negative green trend line) while allowing well-being and economic activity to flourish.

Figure 1. Relative decoupling of well-being and economic activity from resource use, and absolute decoupling of well-being, economic activity and resource use from nature. Source: Own illustration, adapted from UNEP (Citation2019b).

In theory, achieving absolute decoupling can be done by taking a regenerative economy approach, which also meets the goals of sustainable development. While a clear definition of regenerative economy is largely absent from the academic literature (e.g., Gonella et al., Citation2023; Morseletto, Citation2020), the concept encompasses two core ideas – restoration and regeneration. In describing what consists of a regenerative economy, Morseletto (Citation2020, p. 769) defines restoration as “the return to a previous or original state” and regeneration as “the promotion of self-renewal capacity of natural systems” in the context of human industrial activity.

By leveraging these two ideas, the concept of regenerative economy is compatible with circular economy, “an industrial economy that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, Citation2013, p. 7). However, while circular economy considers the biological and technical cycles of (industrial) production, regenerative economy goes a step further by including human well-being, in addition to the focus on nature and industry. Originating from “regenerative agriculture” – a holistic approach that emphasizes the reversal of biodiversity loss and restoring soil health with the aim of achieving social and economic well-being (see Giller et al., Citation2021) – a regenerative economy is not only nature-positive, it is also socially and economically positive (e.g., Brown et al., Citation2018; Kibert, Citation1999; Robinson & Cole, Citation2015). Regenerative economy thereby explicitly acknowledges the inextricable bond between social-ecological systems, recognizing that human collective well-being hinges on the health of the natural world (Hahn & Tampe, Citation2021; Robinson & Cole, Citation2015; van Hille et al., Citation2021). In short, regenerative business approaches encompasses socio-ecological, socio-technical, and circular (closed-loop) systems (Konietzko et al., Citation2023).

Pragmatically speaking, regenerative business approaches minimize the use and replenishing of resources, co-create solutions with stakeholders for collaborative action, and engage in iterative experimentation, adaptation, and reflection to see what works (CircuLab, Citation2023; Hahn & Tampe, Citation2021; Konietzko et al., Citation2023; Robinson & Cole, Citation2015). Pursuing regenerative economy represents a paradigm shift by: (i) acknowledging the mutual relationship between human activity and nature, and taking responsibility for well-being and nature, (ii) sustaining and upholding life-support and life-enhancing functions of social-ecological systems, (iii) reflectively assessing if actions implemented uphold the goals and values of regenerative economy, and (iv) adapting approaches as we learn from experience and circumstances change (Du Plessis & Brandon, Citation2015; Konietzko et al., Citation2023).

Regenerative economy approaches are well suited to the African context, not only because of the significant sustainable development that still needs to take place in Africa, but also because African values are a good match as we will argue later. First, we motivate why a regenerative economy is relevant to the context of Africa by highlighting the need to decouple economic development and well-being from dependence on resource use and nature, and the social-economic and environmental-economic challenges the continent faces in this century. Next, we discuss how regenerative economy can take place in Africa offering selected case examples. Finally, we discuss necessary conditions for the widespread development of regenerative economy and future avenues of research.

Regenerative Economy in the Context of Africa

Africa faces many social and environmental challenges, often more severe than those of other continents. Africa is the world’s largest continent with rich biodiversity that contains diverse, endemic, and iconic species and valuable ecosystem services that face severe decline by 2100 due to climate change and human activity (IPBES, Citation2018). At the same time, human populations, activity, and movement (urbanization) is growing rapidly in Africa, while indigenous knowledge and values are under threat (IPBES, Citation2018). Nature and society are tightly linked in Africa, and tackling environmental problems cannot exist without simultaneously addressing socio-economic needs.

While it is difficult to generalize the social and environmental outlooks for an entire continent consisting of more than 50 countries and 1 billion inhabitants, some overarching trends provide insights into what Africa faces in the coming decades. For example, the 2023 report on the progress of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (“SDGs”) (United Nations, Citation2023) and the Africa Infrastructure Development Index (African Development Bank, Citation2018) highlight the sluggish progress in Africa on the 17 SDGs. Specifically, compared to other continents, Africa – especially sub-Saharan Africa – proportionally suffers more from extreme poverty, water stress, hunger and malnutrition, child mortality and maternal deaths, and diseases such as HIV, malaria, and tuberculosis. Africa also has a high concentration of slum dwellings and lacks basic infrastructure, including schools, access to clean running water, sanitation facilities, fibre broadband networks, reliable transportation, and power infrastructure. In addition, economic sectors such as tourism and manufacturing are lagging, especially after COVID, with low investment in research and development. Food loss and waste is among the highest in the world, and the continent experiences substantial deforestation and land degradation, and a massive debt crisis (United Nations, Citation2023). Hence, on all three fronts – environmental, social, and economic – African nations are experiencing enormous pressure. We go into more depth on several of these trends below.

Urbanization and Workforce

Africa is set to experience a massive growth in workforce (people aged between 15 to 65) by 2050, increasing by 796 million people, doubling the current workforce and adding 15–20 million people each year (Kuyoro et al., Citation2023, using data from UN Population Prospects, Citation2022). The continent is also experiencing urbanization faster than other continents expected to increase 700% by 2030 from 2000 (Anderson et al., Citation2013). Rohat, Flacke et al. (Citation2019) predict that Africa will have up to 79 megacities by 2100, with Lagos-Ikorodu (Nigeria) reaching up to 126 million inhabitants.

Taking into account economic productivity and a recent slower growth, Kuyoro and coauthors (Citation2023) estimate that Africa could add USD 1.4 billion to its economy through a shift to service industries. In an optimistic scenario, this also means a growth in the middle class, predicted to be more than 40% of the population by 2050, and a substantial reduction in poverty; however, in a business-as-usual scenario, the outlooks is less optimistic with only a small growth in GDP per capita, staying under USD 15,000 by 2050. The potential for an African “coming boom” of USD 16.1 trillion in consumer and business spending by 2050 is enabled by two major trade agreements: the African Growth and Opportunity Act and the African Continental Free Trade Area (Signé, Citation2022).

Drivers of urbanization in Africa differ from those of other continents – in Africa, cities are emerging especially around areas of natural resource exploitation and export which mostly serve international markets rather than developing local manufacturing bases (Anderson et al., Citation2013). As such, well-paying jobs are relatively hard to come by, resulting in a high amount of informal living (slums) and work (economy) (Anderson et al., Citation2013). While, to some extent, rural-urban migration relieves pressures on forests and natural spaces, it brings other social, economic, and environmental problems.

Health and Well-being

Africa will also carry a disproportionate burden for human health and well-being. For example, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest proportion of maternal deaths (70%), childhood mortality (75%), and diseases such as HIV, globally (United Nations, Citation2023). Climate change plays a key role in health. In a study of 43 countries, Vicedo-Cabrera et al. (Citation2021) attribute 37% of heat-related deaths to anthropogenic climate change during 1991–2018, with estimates for South Africa above 40% (other African countries were absent from the study, but other global South nations were above 60%). Rising global temperatures affect both maternal and newborn health are negatively (Chersich et al., Citation2022). Similarly, infectious disease occurrences will intensify under a changing climate (Quinn et al., Citation2022). Sleeman et al. (Citation2019) predict an increase in serious health-related suffering of 126% from 2016 to 2060 in Africa as a direct result of climate change. Impacts on health and well-being are not restricted to rural areas. With the rise in global temperatures, many African cities will experience increasingly hot and humid weather that can lead to detrimental impacts on health, and even death. In a study of 173 large African cities, Rohat and coauthors (Citation2019) estimate that human exposure to heat in Africa will more than double by 2060. Such findings, expose “deep fissures and inequities in the world’s capacity to cope with, and respond to, health emergencies,” leading scholars to call for accelerated action (Romanello et al., Citation2021 p. 1619).

Health concerns are also linked to other environmental problems. For example, plastic and microplastic pollution is widespread in Africa, found in water (especially rivers which are hotspots) and on land, accumulating up the food chain, particularly near wastewater treatment plants (see Deme et al., Citation2022). Air pollution is another major topic, which we discuss later.

Food Security

Twenty-one percent Africans are undernourished (and roughly 40% in eastern and central Africa) which is a leading cause of nutritional deficiencies such as stunting, anaemia, and wasting, as well as paradoxically childhood obesity (e.g., Chadare et al., Citation2022; FAO, ECA & AUC, Citation2021). Food-related health concerns are only slowly being addressed, with only a third of West African countries on target to address stunting (Chadare et al., Citation2022). Demand for protein like fish will rise rapidly, with predictions stating that some African countries will become the world’s largest consumers of fish and seafood by 2050 (Chan et al., Citation2019).

The food sector is also important for employment in Africa. For example, 55–62% of the workforce in sub-Saharan Africa is employed in agriculture (ILO, Citation2018; IPCC, Citation2022; World Bank, Citation2020). However, agriculture is adversely affected by climate change (De Lima et al., Citation2021; IPCC, Citation2022). In the future, temperatures and humidity levels will exceed human and livestock tolerance thresholds. If global warming reaches 3°C, agricultural labour capacity in sub-Saharan Africa could decline by 30–50%, exacerbating the region’s economic challenges (De Lima et al., Citation2021).

Demand for Energy

More than two-thirds of sub-Saharan people lack access to electricity and clean cooking options (which affects the lives of women especially and contributes to deforestation), and others face frequent outages (Pappis et al., Citation2019). Electricity capacity across the continent is well below that of India – with a quarter of all generation capacity located in South Africa – and demand for electricity is expected to triple by 2040 and rise nine times by 2065 (Pappis et al., Citation2019). Such enormous demand for electricity generation raises questions of how the electricity will be produced and what proportion of it needs to come from renewable sources to meet the Paris Agreement climate goals. For example, to meet a 1.5–2°C scenario, African fossil fuel consumption needs to decrease by 39–71% (Pappis et al., Citation2019). Biomass accounts for more than half of the primary energy supply and meets the cooking and heating needs of the majority of the population (Holmberg, Citation2008). A drawback of biomass energy is that it contributes indoor and ambient air pollution, especially nitrogen (di)oxide and volatile organic compounds, but also particular matter, carbon monoxide and sulphur dioxide, which exceed World Health Organization air quality guidelines (Agbo et al., Citation2021).

Climate Change

A key factor in climate change is changes in precipitation patterns. For the African continent, precipitation is predicted to decrease by 10–20% by 2050 in southern most nations like Namibia and Botswana and northern nations like Tunisia and Morocco, while it will increase by 20–30% in central/western countries like Niger, Chad and Kenya (Girvetz et al., Citation2019). Similarly, mean annual temperature is expected to rise by 2.7°C by 2050 in the continent using emission trajectories like Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5 (Girvetz et al., Citation2019), which refers to the “business as usual” carbon concentration prediction by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Citation2012). Such changes in precipitation clearly have implications for growing crops, soil health, diseases, biodiversity loss, ground water, and flash flooding.

Scenarios and predictions around climate change are closely tied to predictions of human displacement and migration. According to IPCC (Citation2022), a large proportion of Africans work in sectors that are highly vulnerable to climate impacts. Rises in temperature and accompanying changes in precipitation will affect agriculture/food production and the transmission of diseases such as malaria; likewise, sea-level rise may result in flooding in numerous African cities, especially affecting West Africa (Morrissey, Citation2014). Taken together, these changes will bring about human migration. Specifically, studies predict that 19 million people in North Africa, and up to 85.7 million people in sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, Groundswell Report, Citation2021), could become climate migrants by 2050. Already, 14.1 million people were displaced in sub-Saharan Africa due to climate-related conflict and disasters (World Meteorological Organization, Citation2022).

Biodiversity Loss

Population growth, agricultural expansion and rapid economic transformation all contribute to pressures on biodiversity and ecosystems in Africa (King, Citation2020). Fifty-three percent of inhabitants in Africa depend on nature for energy, housing, water, and jobs (Fedele et al., Citation2021). Forest loss is happening at a faster rate in Africa than other parts of the world, with an anticipated loss of forest and grassland/savannah of over 40 million km2 by 2060 as cropland areas intensify (IRP, Citation2019). On the other hand, forests are also increasingly being protected and managed (FAO, Citation2020), and biomass remains a major share of employment in the continent, compared to metals and minerals (IRP, Citation2019). Degradation of land is a problem in Africa, affecting almost all countries in the continent, but here too the number of key biodiversity areas under protection has increased (United Nations, Citation2022). In a policy brief, King (Citation2020) emphasized the need to focus on restoring terrestrial and aquatic/marine ecosystems as a foundation for development and enhancing livelihoods in Africa, especially because Africa’s “unique natural endowments” have a great potential to generate jobs (African Union, Citation2015; UNEP, Citation2019a). Such development could include agricultural technological innovations and management, wetland restoration, bioenergy, and afforestation/reforestation (Asem-Hiablie et al., Citation2023; Fobissie et al., Citation2019).

Water Scarcity

According to Boretti and Rosa (Citation2019), demand for water – in industry, agriculture, and households – will grow significantly over the next two decades, as populations grow, with majority of this growth taking place in Africa, especially industry (800% increase by 2050). At the same time, the availability of clean water is shrinking as groundwater becomes increasingly scarce, that can additionally cause related problems in (urban) coastal areas due to subsidence, due to pollution from agricultural activity and the climate change-biodiversity feedback loop (Boretti & Rosa, Citation2019).

Large disparities also remain in Africa in terms of access to clean water and especially basic sanitation. While improved since 2000, data from 2015 indicates a strong rural-urban divide and on average only 38% of African citizens have access to safe sanitation (Chitonge et al., Citation2020).

Regenerative Economy Opportunities for Africa

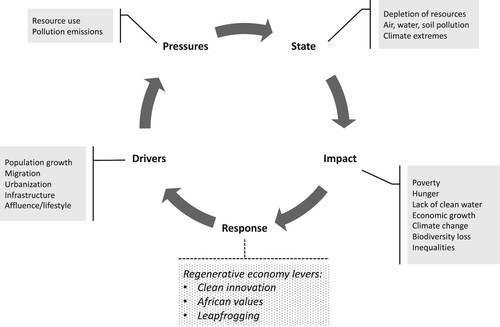

While the set of environmental and social challenges may seem overwhelming at first, they also represent a source of opportunities for African countries. The Drivers-Pressures-State-Impact-Response framework by the IRP (Citation2017) showcases how undesirable environmental and social deterioration result from growing populations and human activity, which subsequently place pressure on the planet (). Completing this loop, is “responses” – actions that can be taken that either exacerbate the drivers or relieve them. The IRP (Citation2017, p. 21) states that a response strategy is to “keep resource use and resulting impacts within acceptable levels” through changing production and consumption and infrastructure systems. Importantly, responses do not only consist of reactive or adaptive responses. Rather, they may also be proactive configurations of new ways of doing business that not only solve the problems resulting from drivers, pressures, state, and impact, but also “restore” and even “renew” the balance between nature, society, and business, thereby mitigating future impacts.

Figure 2. Regenerative economy approaches as response levers to the drivers, pressures, state, and impacts to socio-ecological systems. Image: adapted from IRP (Citation2017).

We propose, here, that the concept of regenerative economy offers several levers for a proactive, anticipatory response strategy that includes not only reducing reliance on natural resources. The three levers with the most potential include: (i) clean innovation through new, sustainable technologies and business models, (ii) leapfrogging through decentralization, and (iii) leveraging African values of horizontal collectivism.

Clean Innovation

Two areas in particular offer potential for regenerative economy via clean innovation across Africa, both based on the wealth of Africa’s natural resources. As the largest arable landmass in the world, Africa has significant non-renewable and renewable natural resources. Cust and Zeufack (Citation2023) and World Bank (Citation2021) estimate that one-third of sub-Saharan Africa’s stock of wealth is based on natural resources. The first of these is the wealth in metals and minerals (non-renewable resources) and the second is the wealth of land and water bodies (renewable resources). Both of these sectors are in primary industries that support all other economic activity and have the opportunity to serve as a meaningful foundation economically, socially, and environmentally.

Clean Innovation in Non-Renewable Natural Resources. Africa is a major provider of minerals; the continent supplies over 70% of the world’s cobalt and nearly 50% of the world’s diamonds (USGS, Citation2018). In addition, Africa is a major producer of mineral commodities such as gold, chromite, manganese, and uranium (USGS, Citation2018). Some 30% of global mineral reserves are in Africa, and minerals (including fossil fuels) account for 70% of Africa’s export and 28% of the GDP (African Development Bank, Citation2016; IPIS, Citation2009). Cust and Zeufack (Citation2023) predict that the demand for these minerals will grow significantly as many of them play pivotal roles in the (global) transition to renewable energy and a low-carbon global economy because they are essential for applications such as wind turbine magnets and electric vehicle batteries (Barron et al., Citation2022). Indeed, production of mining increased by 28% in Africa from 2000 to 2019 (World Mining Data, Citation2021).

The global transition away from fossil fuels towards cleaner energy sources will require around 3 billion tons of minerals and metals by 2050, and Africa is well-positioned to play a leading role in the global market (Cust & Zeufack, Citation2023). For example, Zimbabwe produces 1.4% of lithium globally, while the Democratic Republic of Congo produces nearly 63% of global cobalt (used in lithium-ion batteries, magnetic alloys); South Africa (30%), Gabon (15%), and Ghana (9%) dominate manganese (strengthening steel; dry cell batteries), and Mozambique (14%) and Madagascar (5%) are significant graphite (batteries, solar panels, pencils, electric motors, etc.) producers (World Mining Data, Citation2021). As such, underground assets are vital for Africa’s development in the coming years, both for economic income and job creation (Barron et al., Citation2022; Cust & Zeufack, Citation2023).

At the same time, countries rich in natural resources also tend to suffer from the “resource curse”, not benefitting enormously economically from this wealth (Auty, Citation1993), especially if governance and institutional arrangements are weak, allowing global multinationals and other nations to take advantage (Yenkey & Hill, Citation2022). Data suggests that while countries like South Africa was one of the top 10 net exporters of minerals, the economic benefits remain in the hands of a relatively small number of large, multinational extractive companies (IPIS, Citation2009). And while resources extracted from Africa benefit energy transition in the Global North, many Africans still lack sufficient access to and supply of electricity (Cust & Zeufack, Citation2023; World Bank, Citation2021). By investing in decentralized renewable energy systems, sub-Saharan Africa could reduce residential energy consumption by a quarter and cut annual residential energy-related GHG emissions by a third (Dagnachew et al., Citation2020).

Clean Innovation in Renewable Natural Resources. Africa’s large landmass lends itself to opportunities for regenerative economy in land use. Agriculture, in particular, is vulnerable to changing climate conditions and to improve the resilience of farmers, both regenerative approaches and institutional support and governance systems are needed (IPCC, Citation2022). In addition, regenerative farming can address the problem of soil degradation which is widespread in Africa (Lunn-Rockliffe et al., Citation2020). Nhemachena et al. (Citation2020) additionally emphasize the need to invest in agricultural water management, including irrigation systems and soil water availability, use water more wisely efficiently, and develop technological solutions while monitoring damage on the ground via remote sensing. To ensure agriculture practices are regenerative, species cultivated need to complement endemic species in the region as can be done by cultivating trees and residual forests via spontaneous seeding for future timber resources in the neighbourhood of cocoa fields, for example – and doing so builds resilience to harsher climate conditions (Kouassi et al., Citation2023).

Efforts towards regenerative agriculture likely need support through educating small-scale farmers (Kouassi et al., Citation2023; Weston et al., Citation2015). By retaining and managing multi-purpose tree and shrub species (Kandel et al., Citation2022), farmers diverse income sources that are essential to sustain their livelihoods in years of drought (Reij & Garrity, Citation2016) while biodiversity is restored, maintained, and regenerated. Several factors are critical to the success of implementing regenerative agriculture: engaging farmers in the process to design local solutions, establishing standardized measures, building an open access knowledge store, creating demonstration farms and farmer-led extension programmes, create incentives/rewards for regenerative practices, and building partnerships between science, technology, business, government, and farmers (Lunn-Rockliffe et al., Citation2020).

Leapfrogging

Along the path towards sustainable development, emerging economies can bypass the resource-intensive approaches taken by industrialized countries and use the most advanced technologies, a concept known as leapfrogging (Gallagher, Citation2006). In particular, technological leapfrogging offers opportunities to jump ahead of other countries, as seen in the case of the solar photovoltaic industry in sub-Saharan Africa (Amankwah-Amoah, Citation2015). Leapfrogging is an opportunity for Africa to decouple its economic growth and societal well-being from dependence and pressure on nature, as the continent is largely not yet locked into specific technologies, infrastructure, and so on (IRP, Citation2019). As such, Africa’s comparative advantage over other continents is that it has less path dependence of older technologies and infrastructure, which gives flexibility to invest in regenerative practices right away.

The benefits of leapfrogging are clearly seen in the historical development of mobile phone use across Africa. Already by 2004, sub-Saharan Africa outperformed all other continents in terms of ratio of mobile phone subscribers at 82% (see James, Citation2009). As distances between towns can be substantial in Africa, a decentralized wireless telephone system that did not require digging or hanging physical cables allowed many Africans to gain access to global telecommunications and internet. Mobile phone systems are now used extensively for things like off-grid solar pay-as-you-go systems, which has avoided 26.8 million tonnes of GHG emissions and is another example of decentralized access, in this case to energy (IRP, Citation2019). Mobile payment platforms have also been used in leapfrogging healthcare services in sub-Saharan Africa, which helps to build transparency and trust for healthcare services and billing where the majority individuals have to travel long distances to access banks and hospitals (Nwankpa & Datta, Citation2020).

One benefit of leapfrogging through decentralized energy and communication is that natural spaces can be preserved because there is less need to build infrastructure such as energy grids and telephone lines. With high-speed communication, road infrastructure may also become less important as people are able to connect effectively virtually. Africa's has low population density and remote locations may further make traditional centralized energy generation and distribution impractical, given the associated costs and inefficiencies (e.g., energy losses during transmission; Amigun & von Blottnitz, Citation2010). A more effective approach might involve the implementation of decentralized energy generation, such as harnessing solar power and utilizing biogas plants.

Leveraging African Values

The role of cross-cultural values has not been studied extensively in Africa. Indeed, applying Hofstede’s cross-cultural descriptions of values may be complicated given Africa’s history and context (Jackson, Citation2011). For instance, the legacy of post-colonialism has left Western instrumental and functionalist values, imbued with political and economic interests in the former (control oriented), and models that emphasize the influence of multinationals, consultants, and aid agencies (results oriented) in the latter (Jackson, Citation2002). Traditional (indigenous) values revived in the “African Renaissance” take a more community collectivist-oriented approach, in which decisions are decentralized via participative, consensus-seeking stakeholder approaches (Jackson, Citation2002).

While many different cultures and value systems exist traditionally, common themes include humanity, community, communalism, ethics and morality, kinship, consensus leadership styles, human rights, wisdom, and aesthetics (Awoniyi, Citation2015). Some traditional governance systems in Africa emphasize participative decision-making of communities, as seen in the Botswana Kgotla System of Governance (Mohohlo, Citation2015) and Kenya’s Liguru system (Bagire & Namada, Citation2015) that encourage everyone to have a say and communal dispute resolution. In addition, Amaeshi and Idemudia (Citation2015) refer to “Africapitalism” – a concept in which companies assume the (moral) responsibilities of Africa’s socio-economic development that benefit the larger community (Elumelu, Citation2013; Lutz, Citation2009) – as having the potential to transform management practices in Africa. The four principles that underlie this idea are rooted in the worldview of Ubuntu and include progress and prosperity, parity, peace and harmony, and place and belonging (Amaeshi & Idemudia, Citation2015). Here too, traditional forms of organizing in Africa are community-oriented, with a long history of cooperatives and community enterprises, and social entrepreneurship and innovation seem to be rife on the ground (Littlewood et al., Citation2022).

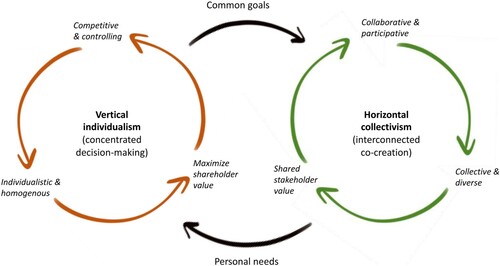

These principles of both traditional governance systems and Africapitalism align closely with concepts of regenerative economy, particularly the notions of inclusive and participative co-creation through being community-oriented and relational. They are also (perhaps unsurprisingly) principles reflected in the African Union’s 50-year Agenda 2063. African values are a good match for regenerative business models because they are oriented towards horizontal collectivism. In other words, common goals are favoured over individual ones, interdependence is explicitly acknowledged, and decision-making rests with the stakeholders – values that are necessary to achieve sustainable development and can also offer a basis for business activity (Walls & Triandis, Citation2014). shows how horizontal collectivism aligns with key principles of regenerative economy that focuses on collaborative and participative action and decision-making, through collective and diverse perspectives, with a focus on creating shared value for stakeholders (we include here nature as a stakeholder). This is contrasted against a more typical Western vertical individualism where decision-making tends to occur in the hands of a few powerful actors in an economic system that prioritizes competition, individual gains, and maximizing value for shareholders often at the detriment to other stakeholders.

Figure 3. A values perspective on regenerative economy. Image: Inspired by Wahl (Citation2017), integrating ideas from Walls and Triandis (Citation2014) and this article.

Case Examples of Regenerative Business Models in Africa

Applications of regenerative economy can be found in different types of business models. For instance, they can be industry-wide as in the case of the rooibos industry’s benefit sharing scheme. Or, they can evolve from the NGO sector to address a social-economic as well as ecological need, as seen in the Okavango Craft Brewery. Examples also arise in Africa through decentralized access to communication and energy. Finally, a joint effort between Kuapa Kokoo and Chocolats Halba illustrates net-positive impacts on ecological, social, and economic systems through dynamic agroforestry. Below, we provide some details of cases implementing regenerative business models.

The Rooibos Industry-Wide Benefit Sharing System

With the aim to address power asymmetries that have arisen through historical contexts, the rooibos (a naturally caffeine free plant used to make “red” or “bush” tea and other products) industry in South Africa offers a good example. To protect both the biological region where the plant grows and the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples and communities who cultivate the plant, the sector has engaged in an industry-wide benefit-sharing agreement as a form of collective intellectual property system (Meyer & Naicker, Citation2023). Rooibos knowledge is traditionally that of the San indigenous peoples, who were subsequently severely oppressed by European settlers. Accounting for 10% of the global herbal tea market, the vast majority of this crop is produced on land owned by white commercial farmers and only about 2% by small-scale farmers. In 2019, an industry-wide benefit-sharing agreement was signed that provides equal partnership to the San by amassing power and economic benefits to this local community (Meyer & Naicker, Citation2023).

Social Enterprises Evolved from NGOs

Okavango Craft Brewery emerged from the work of Ecoexist, an NGO that seeks to address conflict between humans and elephants in the Okavango panhandle area of Botswana (Okavango Craft Beer, Citation2023). Farmers in the region share space with elephants often leading to the destruction of crops. One solution, through Okavango Craft Brewery, is to offer rewards to farmers who coexist with elephants by creating a market for millet grown sustainably. The company purchases millet from small-scale farmers in the Okavango region at a premium price and is connecting these farmers to new markets, providing incentives for their coexistence efforts. The partnership promotes sustainable and inclusive economic growth within the local community. By transforming millet into craft beer, Okavango Craft Brewery not only offers consumers a beverage and brewpub and beer garden, but also provides consumers with the chance to support both local farmers and elephants in the Okavango region. Ecoexist’s research has helped to identify “elephant corridors” – paths that elephants regularly travel to access water in the Okavango Delta. In collaboration with local farmers and the government, cultivation is discouraged on these areas of land. By offering alternative incentives such as a new millet beer market, and empowering farmers and communities, Okavango Craft Brewery is providing an economic, socially, and environmentally sustainable solution.

Pay-as-you-go Solar Energy

M-KOPA Solar seeks to offer affordable access to high-quality solar home systems, funded through a syndicated debt facility via East African Bank and the Commercial Bank of Africa and sustainability-linked debt (M-Kopa, Citation2023; Safaricom, Citation2023; Triodos, Citation2023). Additional lenders include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, LGT Venture Philanthropy, Imprint Capital and Netri Foundation, Standard Bank, the International Finance Corporation, Lion’s Head Group and British International Investment. It is also supported through grants from the DFID (UK), Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Shell Foundation and a re-investment scheme for equity by Gray Ghost Ventures. The start-up represents one of Africa’s biggest tech fundraisings at USD 250 million (Pilling, Citation2023). In 2018, Sumitomo Corporation took a large stake in the company for further investment. Leveraging M-KOPA’s idea of digital micro-payments with mobile phone connectivity and a partnership with Safricom’s M-PESA monetary platform, customers pay a USD 35 deposit, followed by daily top-ups of USD 0.45 through their mobile phones to access solar powered energy. Embedded GSM technology remotely activates the system upon credit purchase. After about 12 months, customers own the system. M-KOPA’s innovative solar tech brings green energy to rural homes, recharging lights, radios, torches, and mobile phones. As of 2023, the company has provided services to more than 3 million customers with extended cumulative credit of over USD 1 billion. Customers benefit from improved livelihoods through clean energy access and reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and less indoor air pollution.

Regenerative Agriculture

Chocolats Halba, Kuapa Kokoo, and their project partners launched 2019 the “Sankofa” project in Ghana. This initiative aims to promote biodiversity, mitigate the impacts of climate change on cocoa cultivation, and diversify the income of cocoa farmers (Chocosuisse, Citation2023; Halba, Citation2023). The core of the Sankofa project lies in dynamic agroforestry, where farmers cultivate a variety of crops alongside cocoa, including yams, maize, beans, and cassava. By reintroducing traditional, resource-friendly farming practices and providing training in sustainable agriculture, the project promotes soil health, reduces reliance on chemical inputs, and ultimately enhances long-term yields. With the Sankofa project, approximately 2,900 Ghanaian farmers and around 17,400 household members benefit from dynamic agroforestry. The project goes beyond agriculture by addressing socio-economic challenges in West Africa. The increased income generated from diversified cocoa production and the sale of additional products grown within agroforestry cocoa parcels helps combat child labour and empowers women. This additional income is often invested in education, providing families with newfound opportunities while reducing reliance on child labour.

Discussion

Regenerative economy is a holistic approach that explicitly links social and ecological systems to economic systems, hinging sustainable development on human well-being and a flourishing natural world. It represents a sustainable development opportunity for Africa, in an intimidating context of severe current and future social and environmental challenges. We offer three levers through which regenerative business models could function in Africa: clean innovation via new technological and business models, leapfrogging via decentralized solutions that work in remote locations through mobile micro-financing schemes, and leveraging African values of horizontal collectivism. We have shown some examples of regenerative economy approaches in industry-wide schemes, social enterprises that emerge from NGOs, multi-stakeholder backed financial for large scale implementation, and community partnerships with large multinationals in agriculture. In short, the concept of regenerative economy has already been tested and shown to work.

Of course, many practical challenges remain. The first of these is scaling up regenerative business approaches, which to date typically remain small and localized, or pilot projects, especially in so-called “base of pyramid” markets (Prahalad, Citation2004). New projects often face high up-front capital expenses, limited financing especially for consumers or end-users, a shortage of human capacity, and a lack of awareness (Amankwah-Amoah, Citation2015). In addition, operating costs cannot exceed the potential market size, and contextualized solutions may not always be transferable to other settings (Lashitew et al., Citation2022). However, Amankwah-Amoah (Citation2015) also points out that such barriers may be overcome by involvement by the state, NGOs or aid agencies, multinational enterprises that operate in the global South, or other models such as the “Avon” and pay-as-you-go approaches. Indeed, micro-financing has been identified as a critical mechanism for scaling up base-of-pyramid approaches but doing so requires a somewhat developed and efficient capital market, capacity/resources, and financial backing, and rapid building of the brand to make the market aware of the new venture (Kistruck et al., Citation2011). An alternative approach in Africa might be via public-private partnerships, such as the case of waste management that combines pricing incentives, extended producer responsibility and other rights-based initiatives, regulatory, and behavioural (social norms, nudging) frameworks (Deme et al., Citation2022).

A second important theme is adequate governance. Examples from the mining industry in Africa highlight that while both large-scale and artisanal and small-scale mining operations have the potential to bring opportunities for the SDGs, they also have negative impacts on every SDG and especially on social communities, children, conflict/violence, and environmental degradation (Mensah et al., Citation2020; Sturman et al., Citation2020). While Africa may be a sleeping giant of untapped resources, their exploitation often rests on the shoulders of children and the economically disadvantaged who work in sub-human conditions; oppressed by powerful intermediaries, amidst weak institutional arrangements and absent accountability of downstream multinationals (e.g., Kara, Citation2022). Nor will it benefit Africa to continue to exploit fossil fuels couched under the lure of “environmental justice” as seen in the recent Africa Climate Summit (Civillini, Citation2023), which is only likely to magnify the “resource curse” (e.g., Turner, Citation2007) and serves as a convenient fix for the global North that is battling its own fight with climate change. Thus, Africa’s natural resources no doubt play a role for the continent’s development and may produce benefits in building agricultural and public infrastructure (for example by Chinese players), but the cost to society and nature can be high and international political economy must be taken into consideration (Broich et al., Citation2019; Ramutsindela & Mickler, Citation2020). Moreover, by focusing on regenerative solutions, Africa can create a comparative advantage that is future-ready. Building institutions that effectively support and encourage a regenerative economy therefore depends on good governance and management, on a continent imbued with former colonialism, conflict and post-conflict states, and regimes with long-serving heads of state (e.g., DeGhetto et al., Citation2016) and exploitative multinational companies (e.g., Oyier, Citation2017).

Third, Africa faces a human resource challenge. To build sufficient capacity for a regenerative economy, individuals must have access to education, which still remains out of reach for many (DeGhetto et al., Citation2016). Kwesiga (Citation2015) expands by saying that African countries particularly need to invest in tertiary education (especially with a focus on technology) to jumpstart development. However, sub-Saharan Africa has the lowest rate of higher education enrolment globally, at just 5% (Bloom et al., Citation2006) and many university-trained Africans have emigrated abroad (Ligami, Citation2019). As a result of education gaps and rejection of embedding indigenous values and practices of management (by Western organizations), local capacity has been slow to build up, and only a tiny proportion in Africa is spent on research and development (Bagire & Namada, Citation2015). This leaves the continent with a human resource gap when it comes to successful implementation of the photovoltaic market for example, which requires a specific set of skills and training for designing, using, and maintaining the technology (Abdelrazik et al., Citation2022).

Our work offers several prospects for future research. First, it is clear that the role of clean innovation and social entrepreneurship will be critical levers of regenerative economy. Second, new business models and approaches may be needed. Some of these may build on previously established models such as base-of-pyramid approaches, hybrid organizations, and circular economy models. New forms of business models may also be identified as scholars pursue this topic. Third, public-private partnerships and other types of stakeholder collaborations and participative approaches with local communities are likely needed; how such partnerships work and what allows them to work well is an area of future research. Similarly, new modes of participative and just collaboration between communities and multinationals may offer a much-needed path towards regenerative economy in Africa. Finally, the socio-psychological dimensions of regenerative economy, including giving a voice to African values, is an important future area of study.

Conclusion

Regenerative economy approaches offer a new way of doing business in Africa that have the potential to benefit people, nature, and the economy. We propose that this can be achieved by pursuing clean innovation solutions, leapfrogging through decentralized communication and energy systems, and leveraging African values that match the core principles of regenerative economy. If Africa can find ways to scale up regenerative business models, implement effective governance systems and build human capacity, the future for Africa is bright and future-ready.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gift Dembetembe and Dr. Kerrigan Unter for their comments on earlier drafts, and Prof. Simon Evenett for a helpful discussion. We also thank participants and discussants at the professional development workshop on “Sustainability, Natural Assets, and Regenerative Economy as Drivers of Africa’s Economic Development” at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting in Boston 2023. This research was supported in part by funding from the Sustainable Development Solutions Network Switzerland.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Judith L. Walls

Judith L. Walls is a Professor and Chair of Sustainability Management at the Institute for Economy and the Environment, University of St.Gallen (Switzerland). She holds a PhD in Management from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (USA), an MBA in International Business from the National University of Singapore (Singapore), and an MSc in Wildlife, Biodiversity and Ecosystem Health from the University of Edinburgh (UK). Her research focuses on environmental (climate and biodiversity) sustainability governance and strategy in companies, with an interest in contested industries. She has a background in investor relations consulting and spent many years volunteering in NGOs in sub-Saharan Africa and Mongolia.

Leo Luca Vogel

Leo Luca Vogel is a PhD student and Research Associate at the Institute for Economy and the Environment, University of St.Gallen (Switzerland). He holds a Masters in General Management degree (summa cum laude) from the University of St.Gallen. His research focuses on firms’ dependence on nature, buyer-supplier power in agricultural commodity supply chains, and strategic responses of buyers or suppliers to grievances. He has a strong interest in biodiversity, the diffusion of sustainability in multi-tier supply chains, and agricultural commodities – maybe because he used to be a professional chef in various renowned Swiss restaurants.

References

- Abdelrazik, M. K., Abdelaziz, S. E., Hassan, M. F., & Hatem, T. M. (2022). Climate action: Prospects of solar energy in Africa. Energy Reports, 8, 11363–11377. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.08.252

- African Development Bank. (2016). African natural resources center: Catalyzing growth and development through effective natural resources management. Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: African Natural Resources Center.

- African Development Bank. (2018). The Africa infrastructure development index. Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire: African Development Bank, AfDB Statistics Department.

- African Union. (2015). Agenda 2063: The Africa we want. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: African Union Commission.

- Agbo, K. E., Walgraeve, C., Eze, J. I., Ugwoke, P. E., Ukoha, P. O., & Van Langenhove, H. (2021). A review on ambient and indoor air pollution status in Africa. Atmospheric Pollution Research, 12(2), 243–260. doi:10.1016/j.apr.2020.11.006

- Amaeshi, K., & Idemudia, U. (2015). Africapitalism: A management idea for business in Africa? African Journal of Management, 1(2), 210–223. doi:10.1080/23322373.2015.1026229

- Amankwah-Amoah, J. (2015). Solar energy in sub-Saharan Africa: The challenges and opportunities of technological leapfrogging. Thunderbird International Business Review, 57, 15–31. doi:10.1002/tie.21677

- Amigun, B., & von Blottnitz, H. (2010). Capacity-cost and location-cost analyses for biogas plants in Africa. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 55(1), 63–73. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2010.07.004

- Anderson, P. M. L., Okereke, C., Rudd, A., & Parnell, S. (2013). Regional assessment of Africa. In T. Elmqvist, M. Fragkias, J. Goodness, B. Güneralp, P. Marcotullio, R. McDonald, S. Parnell, M. Schewenius, M. Sendstad, K. C. Seto, & C. Wilkinson (Eds.), Urbanization, biodiversity and ecosystem services: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 453–459). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Asem-Hiablie, S., Dooyum Uyeh, D., Adelaja, A., Gebremedhin, K., Srivastava, A., Ileleji, K., … Park, T. (2023). An outlook on harnessing technological innovative competence in sustainably transforming African agriculture. Global Challenges, 7(9), 1–9. doi:10.1002/gch2.202300033

- Auty, R. (1993). Sustaining development in mineral economies (The resource curse thesis). London: Routledge.

- Awoniyi, S. (2015). African cultural values: The past, present and future. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 17(1), 1–13.

- Bagire, V., & Namada, J. (2015). Management theory, research and practice for sustainable development in Africa: A commentary from a practitioner’s perspective. Africa Journal of Management, 1(1), 99–108. doi:10.1080/23322373.2015.994430

- Barron, K. C., Hakker, M. E., & Cullen, J. M. (2022). Material requirements for future low-carbon electricity projections in Africa. Energy Strategy Reviews, 44, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2022.100890

- Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Chan, K. (2006). Higher education and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. International Higher Education, 45, 6–7. doi:10.6017/ihe.2006.45.7924

- Boretti, A., & Rosa, L. (2019). Reassessing the projections of the world water development report. npj Clean Water, 2(15), 1–6. doi:10.1038/s41545-019-0039-9

- Broich, T., Szirmai, A., & Adedokun, A. (2019). Chinese and western development approaches in Africa: Implications for the SDGs. In M. Ramutsindela, & D. Mickler (Eds.), Africa and the sustainable development goals (pp. 33–48). Cham: Springer.

- Brown, M., Haselsteiner, E., Apro, D., Kopeva, D., Luca, E., Pulkkinen, K.-L., & Rizvanolli, B. V. (2018). Sustainability, restorative to regenerative. Working Group One Report. Vienna, Austria: RESTORE.

- Chadare, F. J., Affonfere, M., Sacla Aidé, S., Fassinou, F. K., Salako, K. V., Pereko, K., … Assogbadjo, A. E. (2022). Current state of nutrition in West Africa and projections to 2030. Global Food Security, 32, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100602

- Chan, C. Y., Tran, N., Pethiyagoda, S., Crissman, C. C., Sulser, T. B., & Phillips, M. J. (2019). Prospects and challenges of fish for food security in Africa. Global Food Security, 20, 17–25. doi:10.1016/j.gfs.2018.12.002

- Chersich, M., Scorgie, F., Filippi, V., Luchters, S., Change, C., & Group, H.-H. S. (2022). Increasing global temperatures threaten gains in maternal and newborn health in Africa: A review of impacts and an adaptation framework. Gynecology & Obstetrics, 160(2), 421–429. doi:10.1002/ijgo.14381

- Chitonge, H., Mokoena, A., & Kongo, M. (2020). Water and sanitation inequality in Africa: Challenges for SDG 6. In M. Ramutsindela, & D. Mickler (Eds.), Africa and the sustainable development goals (pp. 207–218). New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Chocosuisse. (2023). Projekt «Sankofa» von Chocolats Halba & Coop in Ghana. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.chocosuisse.ch/en/beitrag/projekt-sankofa-von-chocolats-halba-coop-in-ghana

- CircuLab. (2023). Regenerative and circular economy, What is it? Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://circulab.com/regenerative-economy-definition/.

- Civillini, M. (2023). African leaders skirt over fossil fuels in climate summit declaration. Climate Home News. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.climatechangenews.com/2023/09/06/african-leaders-skirt-over-fossil-fuels-in-climate-summit-declaration/

- Cust, J., & Zeufack, A. (2023). Africa’s resource future: Harnessing natural resources for economic transformation during the low-carbon transition. Washington, United States: World Bank, Agence Française de Développement.

- Dagnachew, A. G., Poblete-Cazenave, M., Pachauri, S., Hof, A. F., van Ruijven, B., & van Vuuren, D. P. (2020). Integrating energy access, efficiency and renewable energy policies in sub-Saharan Africa: A model-based analysis. Environmental Research Letters, 15(12), 125010. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abcbb9

- Dalyop, G. T. (2019). Political instability and economic growth in Africa. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies, 13, 217–257. doi:10.1007/s42495-018-0008-1

- De Lima, C. Z., Buzan, J. R., Moore, F. C., Baldos, U. L. C., Huber, M., & Hertel, T. W. (2021). Heat stress on agricultural workers exacerbates crop impacts of climate change. Environmental Research Letters, 16(4), 1–12. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abeb9f

- DeGhetto, K., Gray, J. R., & Kiggundu, M. N. (2016). The African Union’s Agenda 2063: Aspirations, challenges, and opportunities for management research. Africa Journal of Management, 2(1), 93–116. doi:10.1080/23322373.2015.1127090

- Deme, G. G., Ewusi-Mensah, D., Atinuke Olagbaju, O., Okeke, E. S., Okoye, C. O., Odii, E. C., … Sanganyado, E. (2022). Macro problems from microplastics: Toward a sustainable policy framework for managing microplastic waste in Africa. Science of The Total Environment, 804, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150170ac

- Du Plessis, C., & Brandon, P. (2015). An ecological worldview basis for a regenerative sustainability paradigm for the built environment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 109, 53–61. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.098

- Ehrenfeld, J. R., & Hoffmann, A. J. (2013). Flourishing: A frank conversation about sustainability. London: Routledge.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2013). Towards the circular economy: Opportunities for the consumer goods sector (Vol. 2). [Online]. Retrieved from https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-2-opportunities-for-the-consumer-goods

- Elumelu, T. O. (2013). Africapitalism: The path to economic prosperity and social wealth. The Tony Elumelu Foundation. Retrieved from https://africanphilanthropy.issuelab.org/resource/africapitalism-the-path-to-economic-prosperity-and-social-wealth.html

- FAO. (2020). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations – FAO eLearning Academy – SDG Indicator 14.b.1 – Securing sustainable small-scale fisheries. Retrieved 3 November 2021 from https://elearning.fao.org/course/view.php?id=348&lang=en

- FAO, ECA and AUC. (2021). Africa – Regional overview of food security and nutrition 2021: Statistics and trends. Accra: FAO.

- Fedele, G., Donatti, C. I., Bornacelly, I., & Hole, D. G. (2021). Nature-dependent people: Mapping human direct use of nature for basic needs across the tropics. Global Environmental Change, 71, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102368

- Fobissie, K., Chia, E., Enongene, K., & Oeba, V. (2019). Agriculture, forestry and other land uses in nationally determined contributions: The outlook for Africa. International Forestry Review, 21(1), 1–11. doi:10.1505/146554819827167484

- Foster, V., & Briceno-Garmendia, C. (2010). Africa’s infrastructure: A time for transformation. Africa development forum. Washington, United States: World Bank.

- Gallagher, K. S. (2006). Limits to leapfrogging in energy technologies? Evidence from the Chinese automobile industry. Energy Policy, 34(4), 383–394. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2004.06.005

- Giller, K. E., Hijbeek, R., Andersson, J. A., & Sumberg, J. (2021). Regenerative agriculture: An agronomic perspective. Outlook on Agriculture, 50(1), 13–25. doi:10.1177/0030727021998063

- Girvetz, E., Ramirez-Villegas, J., Claessens, L., Lamanna, C., Navarro-Racines, C., Nowak, A., … Rosenstock, T. S. (2019). Future climate projections in Africa: Where are we headed? In T. Rosenstock, A. Nowak, & E. Girvetz (Eds.), The climate-smart agriculture papers (pp. 15–27). Cham: Springer.

- Gonella, J., Filho, M., Ganga, G., Latan, H., & Jabbour, H. (2023). Towards a regenerative economy: An innovative scale to measure people’s awareness of the circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 421, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138390

- Goodfellow, T. (2020). Finance, infrastructure and urban capital: The political economy of African ‘gap-filling.’. Review of African Political Economy, 47(164), 256–274. doi:10.1080/03056244.2020.1722088

- Hahn, T., & Tampe, M. (2021). Strategies for regenerative business. Strategic Organization, 19(3), 456–477. doi:10.1177/1476127020979228

- Halba. (2023). Aufforstung statt Entwaldung. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.halba.ch/de/nachhaltigkeit/nachhaltigkeits-projekte/ghana.html.

- Holmberg, J. (2008). Natural resources in sub-Saharan Africa: Assets and vulnerabilities. Uppsala, Sweden: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- ILO. (2018). The employment impact of climate change adaptation. Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization.

- IPBES. (2018). E. Archer, L. E. Dziba, K. J. Mulongoy, M. A. Maoela, M. Walters, R. Biggs, M.-C. Cormier-Salem, F. DeClerck, M. C. Diaw, A. E. Dunham, P. Failler, C. Gordon, K. A. Harhash, R. Kasisi, F. Kizito, W. D. Nyingi, N. Oguge, B. Osman-Elasha, L. C. Stringer, & N. Sitas (Eds.), Summary for policymakers of the regional assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services for Africa of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bonn, Germany: IPBES secretariat.

- IPCC. (2012). C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S. K. Allen, M. Tignor, & P. M. Midgley (Eds.), Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. (2022). Africa. In H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. M. B. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, & B. Rama (Eds.), Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability (pp. 1285–1456). Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- IPIS. (2009). Africa’s natural resources in a global context. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://ipisresearch.be/publication/africas-natural-resources-global-context/

- IRP. (2017). S. Bringezu, A. Ramaswami, H. Schandl, M. O’Brien, R. Pelton, J. Acquatella, E. Ayuk, A. Chiu, R. Flanegin, J. Fry, S. Giljum, S. Hashimoto, S. Hellweg, K. Hosking, Y. Hu, M. Lenzen, M. Lieber, S. Lutter, A. Miatto, A. West, B. Wiijkman, R. Zhu, & Zivy (Eds.), Assessing global resource use: A systems approach to resource efficiency and pollution reduction. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme.

- IRP. (2019). B. Oberle, S. Bringezu, S. Hatfield-Dodds, S. Hellweg, H. Schandl, J. Clement, L. Cabernard, N. Che, D. Chen, H. Droz-Georget, P. Ekins, M. Fischer-Kowalski, M. Flörke, S. Frank, A. Froemelt, A. Geschke, M. Haupt, P. Havlik, R. Hüfner, & B. Zhu (Eds.), Global resource outlook: Natural resources for the future we want. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme.

- Jackson, T. (2002). Reframing human resource management in Africa: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(7), 998–1018. doi:10.1080/09585190210131267

- Jackson, T. (2011). From cultural values to cross-cultural interfaces: Hofstede goes to Africa. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(4), 532–558. doi:10.1108/09534811111144656

- James, J. (2009). Leapfrogging in mobile telephony: A measure for comparing country performance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76(7), 991–998. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2008.09.002

- Kandel, M., Anghileri, D., Alare, R. S., Lovett, P. N., Agaba, G., Addoah, T., & Schreckenberg, K. (2022). Farmers’ perspectives and context are key for the success and sustainability of farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR) in northeastern Ghana. World Development, 158, 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106014

- Kara, S. (2022). Cobalt red: How the blood of the Congo powers our lives. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Kibert, C. (1999). Reshaping the built environment: Ecology, ethics, and economics. Washington: Island Press.

- Kieh, Jr. G. K. (2009). The state and political instability in Africa. Journal of Developing Societies, 25(1), 1–25. doi:10.1177/0169796X0902500101

- King, N. (2020). Key African priorities for a post-2020 global biodiversity framework, Policy Briefing. Johannesburg, South Africa: South African Institute of International Affairs.

- Kistruck, G. M., Webb, J. W., Sutter, C. J., & Ireland, R. D. (2011). Microfranchising in base-of-the-pyramid markets: Institutional challenges and adaptations to the franchise model. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(3), 503–531. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00446.x

- Konietzko, J., Das, A., & Bocken, N. (2023). Towards regenerative business models: A necessary shift? Sustainable Production and Consumption, 38, 372–388. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2023.04.014

- Kouassi, A.K., Zo-Bi, I.C., Aussenac, R., Kouamé, I. K., Dago, M. R., N'guessan, A. E., … Hérault, B. (2023). The great mistake of plantation programs in cocoa agroforests – Let’s bet on natural regeneration to sustainably provide timber wood. Trees, Forests and People, 12, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.tfp.2023.100386

- Kuyoro, M., Leke, A., White, O., Woetzel, J., Jayaram, K., & Hicks, K. (2023). Reimagining economic growth in Africa: Turning diversity into opportunity. [Online]. McKinsey. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/reimagining-economic-growth-in-africa-turning-diversity-into-opportunity

- Kwesiga, E. (2015). Keynote address to the Africa academy of management 2nd biennial conference January 7, 2014: Sustainable development in Africa through management theory, research and practice: A commentary. Africa Journal of Management, 1(1), 109–113. doi:10.1080/23322373.2015.994433

- Lashitew, A. A., Narayan, S., Rosca, E., & Bals, L. (2022). Creating social value for the ‘base of the pyramid’: An integrative review and research agenda. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(2), 445–466. doi:10.1007/s10551-020-04710-2

- Ligami, C. (2019). HE graduates five times more likely to migrate abroad – Report. University World News, Africa Edition. Retrieved 14 October 2023 from https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20190416123235499

- Littlewood, D., Ciambotti, G., Holt, D., & Steinfield, L. (2022). Special issue editorial: Social innovation and entrepreneurship in Africa. Africa Journal of Management, 8(3), 259–270. doi:10.1080/23322373.2022.2071579

- Luiz, J. M., & Ruplal, M. (2013). Foreign direct investment, institutional voids, and the internationalization of mining companies into Africa. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 49(4), 113–129. doi:10.2753/REE1540-496X490406

- Lunn-Rockliffe, S., Davies, M. I., Willman, A., Moore, H. L., McGlade, J. M., & Bent, D. (2020). Farmer led regenerative agriculture for Africa. London, England: Institute for Global Prosperity.

- Lutz, D. W. (2009). African ubuntu philosophy and global management. Journal of Business Ethics, 84, 313–328. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0204-z

- M-Kopa. (2023). We finance progress. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://m-kopa.com

- Mensah, I., Boakye-Danquah, J., Suleiman, N., Nutakor, S., & Suleiman, M. D. (2020). Small-scale mining, the SDGs and human insecurity in Ghana. In M. Ramutsindula, & D. Mickler (Eds.), Africa and the sustainable development goals (pp. 81–90). Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Meyer, C., & Naicker, K. (2023). Collective intellectual property of indigenous peoples and local communities: Exploring power asymmetries in the rooibos geographical indication and industry-wide benefit-sharing agreement. Research Policy, 52(9), 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2023.104851

- Mohohlo, L. (2015). “Sustainable development in Africa through management theory, research and practice.” Official opening speech at the Africa Academy of Management 2nd biennial conference at the University of Botswana, Gaborone. Africa Journal of Management, 1(1), 89–93. doi:10.1080/23322373.2015.994427

- Morrissey, J. (2014). Environmental change and human migration in sub-Saharan Africa. In E. Piguet, & F. Laczko (Eds.), People on the move in a changing climate: The regional impact of environmental change on migration (pp. 81–109). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Morseletto, P. (2020). Restorative and regenerative: Exploring the concepts in the circular economy. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 24(4), 763–773. doi:10.1111/jiec.12987

- Nhemachena, C., Nhamo, L., Matchaya, G., Nhemachena, C. R., Muchara, B., Karuaihe, S. T., & Mpandeli, S. (2020). Climate change impacts on water and agriculture sectors in Southern Africa: Threats and opportunities for sustainable development. Water, 12(10), 2–17. doi:10.3390/w12102673

- Nwankpa, J., & Datta, P. (2020). Leapfrogging healthcare service quality in sub-saharan Africa: The utility-trust rationale of mobile payment platforms. European Journal of Information Systems, 31(1), 40–57. doi:10.1080/0960085X.2021.1978339

- Okavango Craft Breer. (2023). Our Story. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://okavangocraftbrewery.com/our-story/

- Oyier, C. (2017). Multinational corporations and natural resources exploitation in Africa: Challenges and prospects. Journal of Cmsd, 1(2), 69–83.

- Pappis, I., Howells, M., Sridharan, V., Usher, W., Shivakumar, A., Gardumi, F., & Ramos, E. (2019). Energy projections for African countries. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Pilling, D. (2023). Solar start-up secures $250mn in one of Africa’s biggest tech fundraisings. Financial Times. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.ft.com/content/de0a346b-4164-4aad-87a9-b83cd8660262

- Prahalad, C. K. (2004). The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: Eradicating poverty through profits. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing.

- Quinn, C., Quintana, A., Blaine, T., Chandra, A., Epanchin, P., Pitter, S., … Balbus, J. (2022). Linking science and action to improve public health capacity for climate preparedness in lower- and middle-income countries. Climate Policy, 22(9-10), 1146–1154. doi:10.1080/14693062.2022.2098228

- Raleigh, C., & Wigmore-Shepherd, D. (2022). Elite coalitions and power balance across African regimes: Introducing the African cabinet and political elite data project (ACPED). Ethnopolitics, 21(1), 22–47. doi:10.1080/17449057.2020.1771840

- Ramutsindela, M., & Mickler, D. (2020). Africa and the sustainable development goals. Cham: Springer.

- Reij, C., & Garrity, D. (2016). Scaling up farmer-managed natural regeneration in Africa to restore degraded landscapes. bioTropica, 48(6), 834–843. doi:10.1111/btp.12390

- Robinson, J., & Cole, R. J. (2015). Theoretical underpinnings of regenerative sustainability. Building Research & Information, 43(2), 133–143. doi:10.1080/09613218.2014.979082

- Rohat, G., Flacke, J., Dosio, A., Dao, H., & Van Maarseveen, M. (2019). Projections of human exposure to dangerous heat in African cities under multiple socioeconomic and climate scenarios. Earth’s Future, 7(5), 528–546. doi:10.1029/2018EF001020

- Romanello, M., McGushin, A., Di Napoli, C., Drummond, P., Hughes, N., Jamart, L., … Hamilton, I. (2021). The 2021 report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: Code red for a healthy future. The Lancet, 398(10311), 1619–1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6

- Safaricom. (2023). M-Kopa solar brightens off grid solar market. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.safaricom.co.ke/media-center-landing/press-releases/m-kopa-solar-brightens-off-grid-solar-market

- Signé, L. (2022). Understanding the African continental free trade area and how the US can promote its success. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/understanding-the-african-continental-free-trade-area-and-how-the-us-can-promote-its-success/

- Signé, L., & Gurib-Fakim, A. (2019). Africa is an opportunity for the world: Overlooked progress in governance and human development, Africa in focus. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/africa-is-an-opportunity-for-the-world-overlooked-progress-in-governance-and-human-development/.

- Sleeman, K. E., De Brito, M., Etkind, S., Nkhoma, K., Guo, P., Higginson, I. J., Gomes, B., & Harding, R. (2019). The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: Projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. The Lancet, 7(7), 883–892. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X

- Sturman, K., Toledano, P., Akayuli, C. F. A., & Gondwe, M. (2020). African mining and the SDGs: From vision to reality. In M. Ramutsindula, & D. Mickler (Eds.), Africa and the sustainable development goals (pp. 59–70). Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Triodos. (2023). M-KOPA Solar makes clean energy affordable in East Africa. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.triodos-im.com/articles/2015/a-revolutionary-power

- Turner, M. (2007). Scramble for Africa. The Guardian. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2007/may/02/society.conservationandendangeredspecies1

- UN Population Prospect. (2022). World population prospects 2022. New York: United Nations Publication.

- UNEP. (2011). M. Fischer-Kowalski, M. Swilling, E. U. von Weizsäcker, Y. Ren, Y. Moriguchi, W. Crane, F. Krausmann, N. Eisenmenger, S. Giljum, P. Hennicke, P. Romero Lankao, A. Siriban Manalang, & S. Sewerin (Eds.), Decoupling natural resource use and environmental impacts from economic growth, a report of the working group on decoupling to the international resource panel. Villars-sous-Yens, Switzerland: United Nations Environment Programme.

- UNEP. (2019a). GEO-6 for youth Africa: A wealth of green opportunities. Nairobi, Kenya: UN Environment Programme.

- UNEP. (2019b). B. Oberle, S. Bringezu, S. Hatfield-Dodds, S. Hellweg, H. Schandl, J. Clement, L. Cabernard, N. Che, D. Chen, H. Droz-Georget, P. Ekins, M. Fischer-Kowalski, M. Flörke, S. Frank, A. Froemelt, A. Geschke, M. Haupt, P. Havlik, R. Hüfner, M. Lenzen, M. Lieber, B. Liu, Y. Lu, S. Lutter, J. Mehr, A. Miatto, D. Newth, C. Oberschelp, M. Obersteiner, S. Pfister, E. Piccoli, R. Schaldach, J. Schüngel, T. Sonderegger, A. Sudheshwar, H. Tanikawa, E. van der Voet, C. Walker, J. West, Z. Wang, & B. Zhu (Eds.), Global resource outlook. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme.

- United Nations. (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development: Our common future. United Nations General Assembly Document A/42/427.

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations General Assembly Document A/70/L.1.

- United Nations. (2022). Africa sustainable development report: Building back better from the coronavirus disease while advancing the full implementation of the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: AU/UNECA/AfDB/UNEP

- United Nations. (2023). The sustainable development goals report. New York: United Nations Publications.

- USGS. (2018). T. Yager, A. Perez, J. Moon, J. Barry, M. Plaza-Toledo, P. A. Szczesniak, & M. Taib (Eds.), 2017–2018 minerals yearbook. Reston, United States: U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey.

- van Hille, I., de Bakker, F. G. A., Groenewegen, P., & Ferguson, J. E. (2021). Strategizing nature in cross-sector partnerships: Can plantation revitalization enable living wages? Organization & Environment, 34(2), 175–197. doi:10.1177/1086026619886848

- Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M., Scovronick, N., Sera, F., Royé, D., Schneider, R., Tobias, A., … Gasparrini, A. (2021). The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change. Nature Climate Change, 11, 492–500. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-01058-x

- Wahl, C. (2017). Towards a regenerative economy. Medium. Retrieved 12 October 2023 from https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/towards-a-regenerative-economy-bf1c2ed6f792