ABSTRACT

This study sets out to address the decontextualized discourse on African entrepreneurship and attempts to locate it within the socio-cultural context using the philosophy and principles of Ubuntu. It investigates and traces how Ubuntu informs the motive, decisions and actions of the African entrepreneur. The study contrasts the Ubuntu-based decisions of the entrepreneur with the individualistic economic rationalism expected of an entrepreneur in a typical market economy. It presents a peculiar case of a young entrepreneur who started a business in 2013 which has gone through lots of experiences and trajectories that are relevant to Ubuntu philosophy. The study is underpinned by grounded theory research design which enabled us to analyze Ubuntu values and motivation through the entrepreneur’s actions and stories. The research provides insights into the “contours” of the business journey and how social capital helps to sustain the firm. The nuances of economic rationality and humanity feature in this study as the business reached critical moments where the owner was torn between folding up and thinking about the potential impact of this decision on the employees. The research draws policy implications for entrepreneurs in Africa and encourages scholars to interrogate Westernized approaches to the concept of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

This paper presents a case that involves the dynamic motivation of transitional entrepreneurs. The case highlights the changing nature of an African entrepreneur’s motivation and how it affects decisions and actions as he progresses through his entrepreneurial journey (Afutu-Kotey et al., Citation2017). Previous studies have often assumed that entrepreneurs are mainly driven by economic incentives throughout the life-cycle of their businesses (Georgellis & Wall, Citation2005; Velenturf et al., Citation2019). Although the unique socio-cultural factors in Africa may challenge this assumption, there is a dearth of empirical research on entrepreneurship in Africa (Murithi & Woldesenbet Beta, Citation2022; Osiri, Citation2020). Indeed, one very important topic, “entrepreneurial motivation”, still needs more study if we are to address the question, “have we learned anything at all about entrepreneurs?” on the continent (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011, p. 9). Of significance to the investigation of African entrepreneurship is the understanding of how their motivation changes over time. The idea that African necessity entrepreneurs are mainly driven by selfish economic incentives ignores other important considerations, including the fact that intentions have different stages (see, e.g., Gollwitzer & Schaal, Citation1998).

In addition, scholars of entrepreneurship argue that it is inadequate to consider the entrepreneurial process as linear. Instead, it should be understood as goal-directed behavior but with multiple goals and different levels of motivational intensity (Bay & Daniel, Citation2003; Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011; Lawson, Citation1997).

From an African socio-cultural perspective, this argument is apt (Wanyoike & Maseno, Citation2021). An African entrepreneur does not operate as an island even if they wish to do so. Therefore, understanding how their motivation and intentions change over time as they navigate the socio-cultural context of Africa is critical to appreciating entrepreneurial behavior. This is because researchers have argued that both motivation and intention are important determinants of entrepreneurial behavior (Carsrud & Brännback, Citation2011; Ismail, Citation2022). We argue that motivation and intention do not appear in a vacuum and that they are shaped by the socio-cultural context. Since contexts shape entrepreneurial decision-making, some scholars argue that value systems and culture, within the context of entrepreneurship, require further investigation (Aramand, Citation2012).

Current entrepreneurial motivation literature is driven by economic and rational choice theories which assume that people are primarily incentivized to act for individual or selfish goals (see, e.g., Carsrud et al., Citation1989; Hauser et al., Citation2020; Nuijten et al., Citation2020). These theories tend to ignore a sociological dimension which is generally about the culture of entrepreneurship in a given society (Dimitratos & Plakoyiannaki, Citation2003; Hayton & Cacciotti, Citation2013). Digging further into the context, including the peculiarity of cultures and how they might influence entrepreneurial processes, should enable researchers understand the modus operandi of African entrepreneurs (Darley & Blankson, Citation2020).

Depending on the context, motivation and intention can be individualistic, communal, or collectivistic (Wanyoike & Maseno, Citation2021). With the aid of the African philosophy of Ubuntu, this paper explores the dynamism in motivation and intentions of an entrepreneur in an African context. Ubuntu is essentially seen as the humaneness that people and groups exhibit for one another. This includes a pervasive attitude of caring and community, harmony and hospitality, respect and responsiveness (Mangaliso, Citation2001). The underlying ideals that underpin how Africans think, act, relate to one another, and interact with everyone they encounter are based on the Ubuntu ideology. Ubuntu philosophy would see the African entrepreneur as one who pursues communalistic, rather than individualistic, self-interested economic goals (Gade, Citation2012; Mbiti, Citation2015). In other words, guided by the Ubuntu philosophy, individual entrepreneurs are required to be abided by the collective interest of society rather than an individualistic and rationalist economic perspective that regards an entrepreneur as pursuing self-interested economic goals.

The broad aim of the paper is to address the decontextualized discourse on African entrepreneurship and try to locate it within the African socio-cultural context using the philosophy and principles of Ubuntu. Contextualization of the study of entrepreneurship beyond the prevailing globalized templates can help in the understanding of what could best work for the African entrepreneur. To achieve its aim, the paper investigates and traces how Ubuntu philosophy informs the motive, decisions, and actions of the entrepreneur. The study aimed to achieve the following specific objectives: firstly; to discover the extent to which the Ubuntu mindset might exist in an African entrepreneur; secondly; to contrast the Ubuntu-based decisions of the entrepreneur with the individualistic economic rationalism expected of an entrepreneur in a liberal economy (perhaps this will raise questions about how best to understand successful businesses within the African context); thirdly; to draw policy implications for developing entrepreneurs in Africa; finally, to encourage scholars and researchers to interrogate Westernized approaches to the concept of entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship.

2. Literature Review

Ubuntu as a philosophy and a set of values: This paper identifies remnants of African values and principles of Ubuntu in an entrepreneur’s motivation and behaviors. This is important because some researchers and commentators regard Ubuntu as ahistorical imaginations or declining values that exist only in the collective memory of the few (Karsten & Illa, Citation2005). Others see Ubuntu as a management fad that undervalues its worth within African societies (Karsten & Illa, Citation2005; Van der Wal & Ramotsehoa, Citation2001). There are yet others who question the outcomes of the application of Ubuntu in organizations and modern institutions (Enslin & Horsthemke, Citation2004; Swartz & Davies, Citation1997). Despite the reservations about the potential benefits of the applications of Ubuntu in modern organizations, in the early 1990s there were deliberate attempts to experiment with the philosophy in big organizations with some success in South Africa at least (Karsten & Illa, Citation2005; Patricia & Scheraga, Citation1998). The case study in this paper sheds light on these issues. In this section we summarize the philosophy of Ubuntu and some of its values and principles as they relate to entrepreneurship and business in general.

What is Ubuntu? Some scholars consider Ubuntu as a philosophy while others see it as guiding principles for human interaction. From a philosophical point of view, Nussbaum (Citation2003) argues that Ubuntu is a “fountain from which actions and attitudes flow,” (p. 2). Similarly, Damane (Citation2001) views Ubuntu as a belief system that influences attitudes and behavior whilst Swanson (Citation2007, p. 55) notes that: “Ubuntu is recognized as the African philosophy of humanism, linking the individual to the collective through ‘brotherhood’ or ‘sisterhood’”. Swanson (Citation2007, p. 55) also adds a personal view when he asserts: “As I have grown to understand the concept, Ubuntu is borne out of the philosophy that community strength comes of community support, and that dignity and identity are achieved through mutualism, empathy, generosity, and community commitment.” As a philosophy, Ubuntu is illustrated by the following statements: “A person is a person because of others;” “Ubuntu is the quality of being human;” “It is through others that one attains selfhood;” “I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am” (Mbiti, Citation1971; Nussbaum, Citation2003). According to Swanson (Citation2007) Ubuntu makes a fundamental contribution to indigenous “ways” of knowing and being. Central to the philosophical perspective is the view that humanness is the most noble ideal to be aspired to by an African (Nziramasanga, Citation1999). In other words, Ubuntu is a philosophy of viewing the world that defines an African through his or her community. In fact, one argument states that it is the community that bestows humanness upon an individual or withholds it (Makuvaza, Citation1996; Sibanda, Citation2014).

Other scholars view Ubuntu as principles that guide human actions. For example, Nkondo (Citation2007, p. 93) argues that

What has to be learned in Ubuntu is not a doctrine such as ‘the wages of sin are death,’ nor is it a rule such as ‘the truth will free you;’ but how to live humanely with others in a given space and time. It is not a device for instrumental formulation of judgement, but a social practice in terms of which to think, to choose, to act and to speak.

Whether Ubuntu is viewed as a philosophy or a set of principles, it can be used as an instrument for judgement and decision-making by entrepreneurs. As Damane (Citation2001, p. 24) argues, “Whether it is a critical issue that needs to be interpreted or a problem that needs to be solved, Ubuntu is invariably invoked as a scale for weighing good versus bad, right versus wrong, just versus unjust.” Metz (Citation2007) has identified six behavioral principles in his synthesis of the definitions of Ubuntu as a moral theory. Amongst the six characterizations of Ubuntu, the following fits the essence of the philosophy:

An action is right just insofar as it positively relates to others and thereby realizes oneself; an act is wrong to the extent that it does not perfect one’s valuable nature as a social being. An action is right just insofar as it produces harmony and reduces discord; an act is wrong to the extent that it fails to develop community. (Metz, Citation2007, p. 328)

In advocating the application of Ubuntu in African organizations, Lutz (Citation2009, p. 4) argues:

When the firm is understood as a community, the purpose of management is neither to benefit one collection of individuals as shareholders – value – maximization theories claim, nor to benefit several collections of individuals, as stakeholder theories tell us, but to benefit the community, as well as the communities of which it is part. In most African business schools, the doctrine that shareholder – value – maximization is the goal of management is assumed as axiomatic. In addition to being unethical, this doctrine contradicts African cultures.

Lutz (Citation2009, p. 4) further quoted Broodryk (Citation2006, p. 168) where he stated that:

A new culture for enterprise is needed. This culture is about striving for decent survival and working towards profit-making, but not striving for the greatest profit at all costs, especially not at the exploitation of human beings in order to attain goals characterised by greed and selfishness.

2.1. Rationality vs Subjectivity in Entrepreneurship Research: The Place of Ubuntu

Traditional or conventional entrepreneurship research has argued that business decisions have been propelled by rationality (Korobov et al., Citation2017; Packard & Bylund, Citation2021; Pollack et al., Citation2023). Contemporary research is beginning to unpack other non-economic rationality approaches that propel entrepreneurship decisions (Pollack et al., Citation2023) which suggests that researchers need to have a broader understanding of the drivers and sustainers of enterprises across different cultural contexts. For example, researchers such as Hunt et al. (Citation2022) suggest that some entrepreneurial decisions and judgments may emanate from spontaneity or non-rational considerations. The rationality underpinning conventional entrepreneurial research connotes a positivist paradigm, whereas current research seeks to understand other subjectivist orientations which propel business decisions (Bylund & Packard, Citation2022; Packard, Citation2017). Driven by the emerging treatise on the subjectivity notion of entrepreneurship research, this study makes a modest contribution by highlighting how the African embedded culture of Ubuntu underscores particular business decisions of a budding entrepreneur. The study contends that principles underpinning entrepreneurial decisions are at best an embodiment of economic rationality and non-economic motivations in various phases of operations.

2.2. Subsistence Entrepreneurship

The entrepreneur in this case study can be described as a subsistence entrepreneur at the early stage of the business. Although he had enough resources to take care of himself; within the Ubuntu context, looking after oneself alone has no meaning in life. This is because Ubuntu contends that a person is a person through others. Hence, understandably, the entrepreneur, seeing his mother and friends in the state of deprivation, is tantamount to him being in that state of deprivation. Therefore, he can be described as a subsistence entrepreneur amongst other descriptions because subsistence “entrepreneurs provide value for consumers and communities” (Rayburn & Ochieng, Citation2022, p. 273) dominated by poverty. This description fits the argument that in poor African communities, economic and social lives are intricately linked. Therefore, entrepreneurs in such communities are directly or indirectly engaged in the creation of psychosocial value. Entrepreneurship in poor communities is thus not just about making money first and looking after people second (Gau et al., Citation2014; Venugopal et al., Citation2015). Perhaps nowhere can this assertion best be observed than in an Ubuntu context where the boundary of self and others is hard to identify, metaphorically speaking. Ubuntu seeks to obliterate the boundary between individuals and their fellow humans. Therefore, some scholars describe Ubuntu as a philosophy of becoming. For an entrepreneur operating in this context, it will not be surprising to find that his or her motivation, intentions, and actions contrast with economic rationalism which is individualistic and self-serving. Although prior personal experience with deprivation and poverty can be a motivator for pursuing an entrepreneurial career (Alexander & Honig, Citation2019; Musara & Nieuwenhuizen, Citation2020), the context will determine whether the entrepreneur approaches the venture as a self-serving vehicle or a vehicle for communal emancipation. The Ubuntu context will “force” the entrepreneur to pursue the latter.

3. Methodology

This study gives an account of and draws lessons from the experiences of a young African entrepreneur who against all odds has sustained his business [Costless Brands and Rentals] for approximately ten years. Beginning the business largely on economic rationality and the quest to address a community need, this has essentially improved towards the Ubuntu values of community, humanity, and humaneness. Lessons are drawn for policy, practical and research implications. This research is guided by the tenets of grounded theory in order to unearth Ubuntu values and principles that informed the entrepreneur’s motivations, intentions, and actions (Creswell & Poth, Citation2018; Rayburn & Ochieng, Citation2022). Grounded theory is appropriate for this investigation because even though the research is guided by certain theoretical concepts (e.g., Ubuntu values, entrepreneur’s motivation), the novelty of the context of entrepreneurship in a fairly rural and informal setting as well as the nascent nature of research exploring deeper African values embedded in business activities requires the use of this approach (Charmaz, Citation2014; Goulding, Citation2005). Grounded theory research enabled us to see Ubuntu values and how the entrepreneur’s motivation emerged through his actions and stories. We used both inductive and abductive analyses to see the emergence of the entrepreneur’s values and motivation through his stories, decisions, and actions. Abductive analysis enabled us to use our foreknowledge of the theoretical concepts of Ubuntu values and motivation to interpret our observations (Rayburn & Ochieng, Citation2022; Timmermans & Tavory, Citation2012). Researchers have argued that to develop a new theory or confirm specific theories, there is need for deep engagement with the phenomenon as the subject of investigation (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990; Creswell & Poth, Citation2018; Rayburn et al., Citation2020).

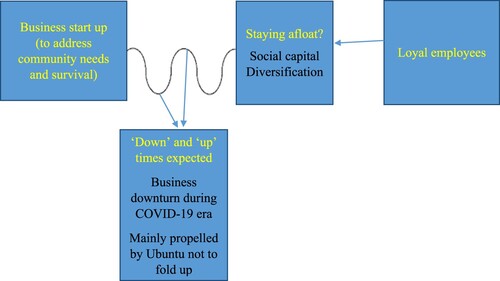

In line with this argument, the researchers spent a lot of time formally and informally discussing and conversing with the entrepreneur to explore his business life history and stories. This informal contact started two years before the actual research started in April 2019 and continued until December 2022. Life stories of the entrepreneur were gathered through informal conversations and narrative enquiry where the entrepreneur was allowed to flow by narrating his life account. A total of 20 informal meetings were conducted. Each meeting lasted approximately 30 minutes. The data gathering involved face-to-face and Zoom sessions and discussions. Data were recorded, later played out loud and transcribed into Microsoft Word. Upon carefully reading the transcript over and over, the authors made sense of the data to observe particular milestones in the life of the business. Consistencies in the narration and responses to questions enabled the authors to observe trends along particular themes. First, we pieced the thoughts in the narration into a well labeled framework () which was used in the ensuing themes in the work. These key themes have been presented as headings and sub-headings in the data section and direct quotations have been used to give more clarity to points expressed.

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Case Study Context: The Business Enterprise

The study presents a peculiar case of a young man who started a business (herein referred to as Costless Brands and Rentals [CBR]). CBR was established in November 2013 by a young man from Northern Ghana in a city called Wa. The capital to set up the business came from the founder’s savings. The business is in the service and hospitality sector. It began with a “conventional motive” (necessity entrepreneur paradigm) but ended up with “unconventional motive” (Ubuntu-like mindset).

4.1.1. Growth So Far

The business started with a single employee who was the owner-operator. However, the business currently has a staff strength of seven people including the founder who plays a symbolic figurehead role. The company has a mixed bag of customers. Some are individuals that patronize specific services such as during weddings and funerals. The other category of clients is business and corporate clients that seek services related to conferences and workshops. Another category of customers is the institutional customers made up of district assembly and government departments. The final category of customers is places of worship such as churches and mosques that may require setting up of tents and furniture for social and spiritual occasions. Thus far, the owner has recouped his initial capital with many other benefits which include goodwill and status as being able to help others fulfill their own dreams.

4.1.2. Motive and Paradigm Shift Towards Ubuntu

The company was set up not just for economic rationality, but also to meet the critical needs of the community. The concern of “community” and “humanism would reflect deeply in critical moments where the owner was torn between folding up or thinking about the impact of the folding up on the employees. The need to inject personal resources to keep the business afloat just to retain loyal employees was reciprocated by employees as the business sustained its operations. Reciprocity of loyalty keeps businesses moving and becomes a win-win gain for everyone.

4.2. Elements of Ubuntu in the Mindset of the African Entrepreneur

From interaction with the respondent, the narration and observations are summarized in . The elements in the framework are presented and discussed under the subsequent themes.

4.2.1. “Start Up” Against All Odds

CBR as a business started operations in 2013 and was still operational in 2023 in a venture most people wouldn’t have dared to try. In the course of the engagements, the business owner explained:

We started as a monopoly … At the time I started, most people considered that only an insane person will use such amount of money to invest in this line of business … However, Wa is a developing community so I went into a line of business that will enable me to be involved in the community. It is the poorest region in the whole of Ghana … Having travelled south for national service, I saw how people were making money from hospitality sector … I don’t have the competence to run other businesses like pure water [or] the time to dedicate [so I chose] services like rentals of equipment for social gatherings [because] when people want something, they come, take it and return them afterwards. If they want my presence, I charge them as well.

It was entirely my experience in the city. When people came from the south, they say, oh, so there is this kind of service here as well? Nearly every day, we will sell out. We kept restocking and we were able to pay ourselves good money.

4.2.2. Up and Down Times to be Expected

Like any other business, it is not always rosy. The firm experienced a fall in its financial performance. The founder pointed out:

We experienced two disturbances. The first disturbance was in 2015 when the country ran into electricity fluctuations. That brought about reduction in people’s disposable income. People were mindful about how much they spent on social events … The government was also one of our key institutional clients. The government was also cutting costs so it hit us so bad. We could run six months without sales.

4.3. Staying Afloat: The Role of Social Capital and Diversification

Following from above, the hard times would have severely hampered business survival but for the role of social capital. The owner narrated:

… but then, my friends [employees of the organization] came onboard and assisted. They brought in money and energy because they realized they cannot rely on me to support them as part of my inner circle.

When my friends came on board, I said ‘why don’t we buy generators because people are now looking for electricity’? Without electricity, people cannot do social events. So, we said let’s try to diversify by renting out the generators for social events. Through this we were able to earn a little more until about 2017 when the electricity generation in the country stabilized a little bit.

From the narrative above, the decision by the founder to invite his friends to join the venture and diversify into another line of business saved the business. The traits of the founder highlighted here are different from those reported in literature in African entrepreneurship which suggests that most entrepreneurs prefer to “go it alone” due to lack of trust in the business environment (Kinoti, Citation2015). This attitude is responsible for high rate of business failures because as the saying goes, “two heads are better than one” especially in time of crisis or difficulties (Lucky et al., Citation2012). Secondly, sole ownership of a business restricts the business from expanding beyond what is physically, skillfully and financially possible (Baik et al., Citation2015). This very factor accounts for one of the main reasons informal businesses do not graduate into formal and bigger businesses in Africa (Haselip et al., Citation2015; Kim et al., Citation2020). It also accounts for one of the reasons why SMEs contribute to lower tax revenue and lower GDP relative to their significant number in the African economies (Atawodi & Ojeka, Citation2012).

4.3.1. Navigating Through the Maze of COVID-19 Era

Having weathered the storm of lack of electricity in 2015, the business again encountered a much more serious challenge that affected its performance. In the course of his narration, he explained:

When COVID-19 came in, if you go through our sales records, we were zero. All the months in 2019/2020, it was zero. So, most of the staff now had to depend on my other income streams to keep the business afloat.

The narrative demonstrates the challenges faced by entrepreneurs and businesspeople in Africa. The business environment is constrained by policy and state capture (Dassah, Citation2018; Meyer & Luiz, Citation2018). Business performance and even survival, especially, at in times of economic crisis, depends on the enabling business environment and institutional support (Shimeles et al., Citation2018). What seems clear from our study is that assessing performance during crises in Africa is more difficult than when there is some support and an enabling business environment.

4.3.2. Tougher Times in Business yet Not Quitting: Empathy for Loyal Employees

In many cases, the business environment can even force people out of business. He put it bluntly: “I thought of closing the business” and use his educational certificate to search for already existing jobs in other organizations. However, he considered his amazing and loyal employees who would be jobless if he closed down the business. It was the consideration of the welfare of his employees which made him try all means possible to save the business during COVID-19 in 2020. He averred:

I had to go into my personal income stream to maintain them again.

… instead of laying off these workers, why don’t we keep them and share our salaries with them? We understand that times are hard and it is not fair to lay them off because we cannot afford to pay them.

4.4. Loyal Employees Carry Business to the Next Level

The owner is no longer directly involved in the day-to-day running of the business, yet the workers have reciprocated his gesture of not having laid them off during COVID-19 era when things were tough. They have since demonstrated significant commitment by introducing new business models which have made the business self-financing. He posited:

[T]hey pay me daily and I don’t ask them how much they make. The agreement was that I will only pay rent whenever it is due and I will maintain the vehicles but restocking the business and other expenses would be their responsibility. It is a win-win situation because they have seen the struggle I had gone through in 2015 and 2019/2020 when we were recording zero sales.

4.5. Getting the Right Set of People is Key

The third implication is that partner or employee selection is critical in the application of Ubuntu spirit in a business. This is also supported by an observation by an experienced businessperson who avers: “I believe the only game in town is the personnel game … My theory is if you have the right person in the right place, you don’t have to do anything else … If ‘you don’t have the right person in the right place, ‘you have a problem. If you have the wrong person in the job, there’s no management system known to man that can save you.” (Walter Wriston, former Chairman and CEO of Citicorp; quoted in Schuler, Citation1988)

Being an African does not guarantee that the partner can agree on or practice Ubuntu principles in a business setting. In fact, it is likely some people who are not Africans might agree on and practice Ubuntu principles (in deeds, perhaps unconsciously than some Africans born and bred in Africa). Therefore, people who wish to practice the Ubuntu principle in their businesses must look for people who share such principles (see Bushe, Citation2019; Turyakira, Citation2018).

This raises our final implications for theory and practice. These are encapsulated in the following questions: Where are the instruments for selecting Ubuntu principled partners? Particular efforts and diligence must be at play in order to detect the right caliber of partners, since many businesses do suffer negativities due to unethical conduct of its workers (see Kabonga et al., Citation2021; Veetikazhi et al., 2021). Where are the policies for promoting Ubuntu principles and practices in African economies? Particular attention is placed on the role of the ethical business owner or manager who espouses Ubuntuism as this study has demonstrated that all things being equal, it is likely to be reciprocated (see also Al Halbusi, Citation2022)

The analysis above has raised interesting issues associated with performance, ethics, reciprocity, and survival in the African business environment. The first point is that when the owner was faced with economic hardships Ubuntu considerations held sway over selfish cost–benefit considerations which would have compelled him to fold up the business or even lay off workers. The second point is that not only has the founder a social conscience, but the other beneficiaries of the business similarly have conscience (Ubuntu). In other words, there is a natural fit amongst the parties to the business which allows consensus-building. The third point is the Ubuntu spirit that has emerged from the founder as well as from his friends. They did not see their workers as economic input but as partners in a journey (ethics). In other words, they were able to see “self” in each other. This Ubuntu spirit is what kept the business running for almost a decade. Nonetheless, Ubuntu spirit alone will not guarantee profitability even though it will ensure survival in times of crisis. This leads us to the fourth point about the need to sacrifice. The narration mentioned three friends/workers who offered to sacrifice part of their salaries to be shared across six people. While this gesture demonstrates Ubuntu spirit, it also highlights the hardnosed business decisions and personality traits required when operating in a harsh business environment where formal institutional support and policy instruments are not available to help an entrepreneur. The fifth point from the story is the need for innovation and diversification during economic and noneconomic crisis. These will enable the business to find alternative sources of revenue and keep the business afloat.

4.6. Contrasting the Ubuntu-based Decisions with Expectations of an Ideal Entrepreneur with Rational Economic Mindset

4.6.1. Business Set Up Motive Dynamism? Humanism Over Economic Rationality

Finally, and most importantly perhaps, narratives from the study shed light on the transitional nature of entrepreneurs’ motives especially in Africa. Although initially the founder could be described as a necessity entrepreneur with individualistic economic motive, the Ubuntu spirit in him made him reconsider the purpose of the business and why he should keep the business to benefit others. He made altruistic economic decisions in order to support members of the business. Ironically, such decisions tend to be economically beneficial to him. Hence, Ubuntu philosophy and principles are not necessarily at odds with economic judgement. What we also saw from this brief story is that, under Ubuntu context, when members of the business share Ubuntu philosophy with the owner of a business, they will be willing to save the business in time of crisis (Mamman et al., Citation2018). They will provide credence to the notion that a business is a business only when the people say so. In other words, it is not the owner that will say he has a business; it is the community that bestows the title on the venture. Just like the Ubuntu saying, a person is a person through people. It is the people that bestow personhood to a person or withhold it” (Makuvaza, Citation1996; Sibanda, Citation2014).

4.7. Entrepreneur’s Evolving Motivations and Intention

The study highlights the notion of evolving entrepreneur’s motivations as the basis for understanding the dynamics and complexity of identifying and locating Ubuntu in the way African entrepreneurs run their businesses. Due to historical and globalization reasons, it is not possible to find pure or ideal “stand alone” Ubuntu being practiced by an entrepreneur or any organization in Africa. Therefore, we sought to explore the remnants of Ubuntu spirit, values and principles in the entrepreneur’s journey. For example, necessity entrepreneurs are not likely to exhibit Ubuntu spirit in the beginning of the entrepreneurial journey. Instead, economic rationalism is more likely to be the principles that guide their decisions and actions even though their instincts might be guided by Ubuntu values. Based on this proposition we investigate the values of Ubuntu in the motive and intentions of the entrepreneur.

In this study, the social concerns and the business owner’s resolve not to lay off workers or fold up not only reflects Ubuntu values but supports Mair and Noboa’s (Citation2006) suggestion that empathy influences the behaviors of entrepreneurs. Similarly, the entrepreneur is pushed and at the same time pulled by factors that conventionally take people into business (economic and social). Thus, he is a necessity entrepreneur who simultaneously acts as a social entrepreneur. Finally, we are dealing with an entrepreneur who has most of the traits of an entrepreneur but does not see himself as an entrepreneur. It can be argued that the socio-cultural context has produced this kind of complex entrepreneur not fully captured in the literature. The following are some of the quotations from our conversations. When asked to explain what inspired and motivated him to start the business, the founder of CBR responded in the following way:

There are two reasons. First, I realize that my community needs this kind of service.

The concept of social entrepreneurs is defined from various perspectives (Bruton et al., Citation2021; Peredo & McLean, Citation2006). However, central to the concept is the notion of creating social value such as generation of jobs and production of goods or services for social purpose (Haugh, Citation2007). Therefore, based on the response above and our lengthy discussions and informal conversations, from whatever perspective, the entrepreneur in our case study can be described as a social entrepreneur who is in business not for himself alone but for his community. However, he does not see himself as a social entrepreneur at the early stage of the enterprise. It can be argued that his motivation changed as he saw the positive social impact of the enterprise. This is not only the emergence of the latent Ubuntu spirit in him, but also sheds light on the complexity and transitory nature of entrepreneurs’ motivations in African context. He went on to say:

I also felt that I couldn’t continue to give money to my friends. … . So, I was like, if they don’t have money to put together as capital so that we can start a business, let me do it and we can still hang around and do things together as usual while running the business. We can do this and make money. These two fit into core issues that are personal to me, so we went for it. To be honest, to me, I would say that it is borne out of this stubbornness of taking the lead when you see the need. So, I took the lead and it became a profitable business. I wasn’t minded about managing cost. What matters to me was that we were getting money to pay our school fees. We were all living decently. There wasn’t this despair between me and my friends. I was able to take care of my mum without breaking my back.

The case highlights that those who are pushed to set up businesses because of economic and livelihood reasons might not necessarily run the business according to economic rationality. Thus, economic motivation alone cannot provide adequate understanding of the complexity of entrepreneurs’ behaviors. In African context at least, failure to follow economic rationalism does not necessarily spell doom for the business. Indeed, there is “rationality” in Ubuntu philosophy since rationality means assessing all facts and arriving at decisions based on facts. The fact of the matter is that social relationship and community goodwill is essential in African communities especially outside big cosmopolitan cities. In a community where everyone knows everyone, economic rationality is not the only determinant of success.

The entrepreneur’s vision can have a significant influence on business performance. This is because it can provide the energy to pursue organizational goals towards the vision. In one of our conversations, the entrepreneur had this to say:

To be honest, I am very surprised that business is still here the way it is. I didn’t start with a long-term mindset. I was cultured into going to school, pass the grades, get a certificate and get a job. So, I grew up with the expectation that I am being a delegate to them who acquired a good certificate and get a good job that will give me a good life not this business. So, I was already convinced in my mind that this business can never give me the aspirations I have in life. So even though I can speak to the benefits of having the business and the satisfaction it has brought to me, I am still looking forward to getting a job. I want to develop it to another level”.

An interesting issue related to this case is whether these entrepreneurial qualities will be used in a normal job or our entrepreneur is about to waste his talent on the wrong career. Importantly, does our entrepreneur see himself running a business in a full capacity rather than being a “back-bencher”? The following statement answers part of the question:

I would say the reason why the business is still there as I told you earlier was the fear of failing those who still believed in me. By the time we had our problem in 2019/2020, I was no longer fully in charge of the business. They took control of the business. They now took the challenge to survive the business. … So, whatever I have to get from the business, I have gotten it. In terms of my social expectations, they are met. Financial expectations too are met. I just do not have the aspiration to grow the business … . The guy who is now heading the business, he taught me a lot such that now even if I am looking for a job from someone, I would also like to play the role that guy has played for me. I see him as the entrepreneur not me. He is the one who grew the business, not me. When I leave to go and look for a job that will match my certificate, these people will manage and expand the business.

Another important issue that came from our conversations and discussions is the question of how entrepreneurs see themselves. Even from the quotation above, it seems some entrepreneurs might not see themselves as entrepreneurs. This might be because they see starting a business as purely transitional and a stepping-stone to what they might consider their ultimate “call” or “goal”. In spite of taking the risk of investing his life savings to start a business, our entrepreneur does not see himself as one. His definition of entrepreneur appears to be someone who is fully engaged in the day-to-day running of the business rather than a person who risks his life savings to start one. It might also be that he sees an entrepreneur as someone whose main goal is to stick to business as the primary means of livelihood and vehicle for achieving one’s aspirations in life. Despite the risk of setting up the business and making difficult decisions, our entrepreneur still doesn’t see himself as an entrepreneur. The entrepreneurial decision to invite people to complement his skills and increase the capacity of the business to deliver more services and diversify is by itself an entrepreneurial decision which only an entrepreneur can do.

What can we deduce from this case so far? It can be deduced that there are many kinds of entrepreneurs in Africa. The combination of cultural and economic factors produces the many shades of entrepreneurs. There are conventional entrepreneurs pursuing individualistic economic goals. There are those who pursue social goals through a quasi-economic paradigm. There are the conventional social entrepreneurs. Finally, there might be entrepreneurs that start as conventional economic entrepreneurs and change to social entrepreneurs or vice versa. The diversity of entrepreneurs’ motives as well as sheds of entrepreneurs have policy and theoretical implications. From the theoretical angle, it seems our definition of an entrepreneur should be broadened to capture the contextual nature of entrepreneurs’ motives in Africa. If entrepreneurship has social and economic benefits, their diversity of motives should be taken into account when crafting policies that are targeted at them. Briefly, the kinds of entrepreneurs in Africa reflect the economy and culture of Africans. As a non-manufacturing economy, entrepreneurs tend to be in service industry. Others are in the trading sector of the economy. The African culture ensures that those outside the cities tend to pursue entrepreneurial activities influenced by the community and culture. Culture and traditions influence motives of entrepreneurs (Hayton & Cacciotti, Citation2013; Tlaiss, Citation2015) while motives can influence entrepreneurs’ behaviors (Hayton & Cacciotti, Citation2013; Lee, Citation1996). Hence, assessment of their performance needs to reflect these contexts because if they operate outside the context, they might not survive. Those in cosmopolitan cities operate in different context. Even those in the cities might have unconventional motives. However, more in-depth research is needed to investigate and contextualize the motives of city entrepreneurs in Africa.

4.8. Entrepreneur’s Performance and Sustainability

4.8.1. Other Similar Enterprises Emerged but Could not Sustain Themselves

In assessing performance of a business, comparison with other competitors is necessary unless the business is a monopoly (Chandler & Hanks, Citation1993; Nickell, Citation1996). Even if the business is a monopoly, its performance can be compared with similar businesses in other markets. When asked whether the business has competitors after its earlier monopolistic position, the founder replied in the affirmative. He explained that although several competitors emerged, their businesses were often short-lived because of limited understanding of the business environment, unfulfilled expectations, the lack of committed staff, among other factors.

Our investigation revealed a number of issues related to competitiveness, survival, and business performance in the African SME environment. One of the issues relates to social and cultural assets. In smaller and rural settings in Africa, being perceived as a member of the community can be a cultural asset and beneficial if the business embraced some of the principles of Ubuntu. New entrants to such market are not likely to have such assets until they build them over the years of operation (Batt, Citation2008). Some might have the bona fide knowledge of the customer but lack the knowledge and/or experience of running a business in a specific market or specific line of business. The founder noted for instance that there had been several instances when some unemployed people had been assisted by their wealthy relatives to start a business. These new entrants to the business would either misuse their profit or fail to invest in ways that could generate significant benefits in the long term:

I have always said our focus is in knowing ourselves and being disciplined. So, like now, I am aware that most young guys like to live ostentatiously. But for them, the training they see from me is that I am young and I have money but I wasn’t using it to live large. … If you compare it with other businesses, the owners … get the money and they spend it all. When there is no business, they don’t have time to focus on the business. You see that they will always close the shop and when the customers come will find that the shop is closed. But we are always open.

The apparent lack of tact and sound judgement coupled with limited understanding of the market often led to these businesses folding up. He further recounts how one new entrant with seeming potential “took away market from us just like that” but “couldn’t sustain it because his employees were stealing his money” and so got frustrated, “sacked all the boys and locked them down”.

The above account contrasts with what the founder in our case study did when his business got into difficulties. Clearly, his competitors took economic decisions while the founder took a long-term view based on what he considers as his social obligation (Ubuntu). However, his decisions were enabled by people who share some of the principles of Ubuntu. Had they been reckless with his money, probably he would have taken a different decision. Nonetheless, his decisions were guided by Ubuntu principles. This reinforces our earlier point that not all Africans would share the Ubuntu principles and spirit in economic activities. This underscores the importance of choosing business partners carefully (Agarici, Citation2021), especially if an entrepreneur wishes to practice Ubuntu principles in his or her business. Some scholars have argued that Ubuntu principles are hardly practiced in African business (see Bushe, Citation2019; Fatoki, Citation2020). We would argue that those researchers did not look hard and deep enough or they have been looking in the wrong places. In addition, they might be looking for ideal and pure Ubuntu. There is no ideal Ubuntu just as there is no ideal and pure neoliberal market ideology practiced anywhere in the world.

4.9. Trust Matters in Africa: The Bane

Notably, the case highlights the importance of tenure and experience in a specific market as a key contributor to business performance and success. Africa may have serial entrepreneurs but may fail to produce successful businesses due to lack of entrepreneurial experience. This case study sheds light on the “cooperative” nature of how the business is run. There is evidence of trust between the founder and his business associates. This is not typical of African business enterprises (Kinoti, Citation2015). To buttress this view about low trust in African society, the entrepreneur lamented how he has invited young graduates from polytechnics to join him to expand the business, but they refused. Instead, each went to establish their small business. He said:

When I offered them the opportunity to join me, it wasn’t for my financial benefit. I thought that it will help them more. It will be like me offering them a platform since I am already established. This would have allowed us to have a more rounded business. I was like, I have been in this business for very long and people know me. So. When people come for rounded service, we tell them we don’t do this one. We don’t have the capacity to do it. So, I will offer you my platform, you can charge what you want to charge and keep your own money. We will now advertise ourselves as full complemented enterprise. But they think you will swallow them because you are big. So, we are ok not doing that.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

The preceding section has raised issues of economy of scale and unregulated competition. The individualistic approach of the new entrants rejecting the offer to team up with an existing entrepreneur does not allow the creation of economy of scale necessary to reduce the cost of running the business. This leads to a high failure rate amongst new entrants. This conclusion affirms an argument by Mamman et al. (Citation2018) that the laissez-faire, free-market approach adopted by African countries ensures that even those who could potentially succeed in business are cannibalized by competitors who have easy access to capital even though they will end up a failure. Given that there are certain qualities entrepreneurs need to have to be successful, it seems unreasonable to allow others who do not have such qualities to enter a specific market to destroy other businesses. Africa does not have the luxury of experimenting to find out who will succeed and who will fail. In line with Ubuntu spirit, it seems prudent for government agencies to encourage collaboration to create economy of scale that will benefit the community rather than creating winners.

It is tempting to ask: We do not allow people who do not have certain qualities to drive a car or to be medical doctors, but why do we allow certain people to get into the market to destroy the livelihood of good entrepreneurs? Government policies that keep funding would-be entrepreneurs without careful screening is counterproductive to job creation. In addition, well-meaning philanthropists doing the same should consider whether they are funding real entrepreneurs or funding a potential cannibal of a business who will end up destroying viable businesses through unnecessary competition. Briefly, we see the need for an institutional role to regulate entry into business rather than rely on market forces to determine who survives and fails. At its current stage of development, Africa cannot afford to operate within a free market, winner-takes-all economic ideology without proper regulation.

The study contends that resilience in the SME and entrepreneurial journey is what yields success. This is to suggest that when people set out to be entrepreneurs, they are very likely to encounter setbacks or adversities along the journey. The study concludes that the ability to remain resilient and to stay above water despite challenges is what makes businesses survive, sustain and grow over time. It should be mentioned that every enterprise goes through some teething stages and even matured enterprises need to be wary of external environmental shocks which require them to re-organize their internal environment to make headway.

This case has reiterated the role of human resources and social capital to be the most valued assets of the organization which determine its survival or decline. In periods when the business thought all was gone and contemplated folding up, the kind of loyal and diligent workers with experience took the wheel and reinvigorated the business. But for their ability to think outside the box and alter the business model, and to be loyal and reliable, the life of the organization would have been cut short. The study highlights the need for entrepreneurs to surround themselves with competent, loyal and trustworthy employees who can be relied upon in periods of both adversity and good times.

The case analysis admonishes entrepreneurs and prospective ones to be on the lookout, thinking outside the box at all times by scanning the internal and external environment. They need to do a SWOT analysis as well as a TOWS analysis. A TOWS analysis combines internal and external forces to come up with productive ideas of how to best use the information; it is action oriented. It allows organizations to reduce threats, take advantage of opportunities, exploit their strengths, and overcome their weaknesses. It has four main quadrants: one quadrant helps organizations to use their strength to maximize opportunities prevalent in the environment; the second quadrant helps organizations to use their strengths to reduce any impending threats; the third quadrant helps organizations reduce weaknesses in order to develop opportunities; and the fourth quadrant helps organizations avoid threats by reducing weaknesses. Clearly, the ability of the owner and his loyal employees in this study to figure out how to use their strengths to capitalize on the opportunities (using financial resources and good will to venture into rentals of generator sets) is a classic case of TOWS analysis, albeit done unconsciously. Diversifying the business portfolio is a sure way to make headway during hard times which eventually may even become the cornerstone of the business, all things being equal.

Another important issue coming from the case is that starting a business can be a personal development experience for the entrepreneur. It helps the entrepreneur to discover the “real self”. From the theoretical point of view, the case story highlighted the need to distinguish entrepreneurs that run a business as a “personal call” from those who run the business as a vehicle to achieve something much different from the business. Even within the latter, there is need to identify the diversity of the goals “the vehicle” (i.e. the business) wishes to achieve and whether each goal has a different impact on how the business is run. For example, a business used as a vehicle for providing jobs might be run differently from a business that is used as vehicle for self-actualization or getting rich. Again, these differences have not attracted adequate attention from researchers. Perhaps entrepreneurship is largely viewed from an economic perspective. However, we have seen the entrepreneur might start from an economic perspective, but his or her disposition and cultural setting can moderate this perspective. In other words, the reality of running a business can lead to changes in motive so that cognitive dissonance can be avoided.

Perhaps one of the biggest issues highlighted in this study is that we are dealing with a transitional entrepreneur. Our entrepreneur clearly demonstrated that even though he might be interested in running a business in the future, he does not see himself as someone who grows a business from the ground. The question is: How many such entrepreneurs exist in Africa? We suspect thousands. What are their characteristics? We speculate they are those brought up in an educational system that brainwashed them to believe that their human capital should be deployed in working for others or the state. What are the implications for African economies that see startups as a panacea for growing their economy and addressing unemployment and social challenges? These questions have serious research and policy implications that are yet to be fully unpacked.

Research Implications

Our study sheds light on an emerging body of research on non-economic rationality that underscores some entrepreneurship decisions (Pollack et al., Citation2023) using the Ubuntu philosophy from an African context. It makes empirical contributions to the extant literature on spontaneity or non-economic rational considerations in business decision making. The study reiterates the role and particular place of human resources in organizational performance. Commitment and loyalty of organizational members in business sustainability cannot be overestimated, albeit such values mostly require fair treatment on the part of the organization or emanate from how the organizations treat them. This study contends that those who call for equity must come with clean hands and in line with the process theories of employee motivation and the Harvard Framework of Human Resource Management, which call for placing humans at the core of organizational decisions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Farhad Hossain

Farhad Hossain is a Professor of Public Management and International Development at the Global Development Institute (GDI), School of Environment, Education and Development at the University of Manchester, UK, where he directs the MSc Programme in Human Resource Management (International Development). He holds a PhD in Administrative Science and has carried out research in a number of countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and North America. From 2009 to 2012, he served as Executive Editor of the International Journal of Public Administration. He has edited a number of special issues in journals and edited books published by Routledge. His research interests include public policy and management, disaster management, development administration, local governance and decentralization, organizational behavior, and institutional and policy aspects of development NGOs and microfinance institutions (MFIs). From 2019 to 2022, he also served on the Executive Board of SICA, the American Society for Public Administration (ASPA).

Mohammed Ibrahim

Mohammed Ibrahim is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) at The University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute where he is also Co-Director of the MSc Programme in Organisational Change and Development. He obtained his PhD in Development Policy and Management from the University of Manchester, UK. He has teaching and research expertise in public administration and management, policy process, comparative social policy, research design and methods. He has reviewed for various reputable journals including Public Administration and Development, European Management Review, Policy and Society, Politics & Policy and European Journal of Development Research.

Emmanuel Yeboah-Assiamah

Emmanuel Yeboah-Assiamah is a Senior Lecturer and Graduate Coordinator (MPhil and MA Programs) at the Department of Political Science in the University of Ghana. Among others, he teaches courses in Human Resource Management & Development as well as Organization Theory at the undergraduate level. He also teaches Organizational Development and Strategic Planning at the graduate level. He concurrently serves as a Fellow at the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA), also based in the University of Ghana. He obtained his PhD in Public & Development Management from the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. Emmanuel has also had Post-Doctoral Training at the Global Development Institute (GDI), the University of Manchester, UK where he researched and studied courses in Management and Human Resource Management. He is a verified reviewer for many reputable journals including Strategic Change, Administrative Theory & Praxis, International Journal of Public Leadership, Third World Quarterly, International Journal of Public Administration, and Australian Journal of Public Administration.

Reference

- Afutu-Kotey, R. L., Gough, K. V., & Owusu, G. (2017). Young entrepreneurs in the mobile telephony sector in Ghana: From necessities to aspirations. Journal of African Business, 18(4), 476–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2017.1339252

- Agarici, C. A. S. (2021). Choosing business partners. FAIMA Business & Management Journal, 9(1), 63–76.

- Al Halbusi, H. (2022). Who pays attention to the moral aspects? Role of organizational justice and moral attentiveness in leveraging ethical behavior. International Journal of Ethics and Systems, 38(3), 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-09-2021-0180

- Alexander, I. K., & Honig, B. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions: A cultural perspective. In Alexander, I.K. & Honig, B (Eds.) Entrepreneurship in Africa (pp. 1–23). London: Routledge.

- Aramand, M. (2012). Women entrepreneurship in Mongolia: The role of culture on entrepreneurial motivation. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 32(1), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/02610151311305623

- Atawodi, O. W., & Ojeka, S. A. (2012). Relationship between tax policy, growth of SMEs and the Nigerian economy. International Journal of Business and Management, 7(13), 125. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijbm.v7n13p125

- Baik, Y. S., Lee, S. H., & Lee, C. (2015). Entrepreneurial firms’ choice of ownership forms. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(3), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0289-9

- Batt, P. J. (2008). Building social capital in networks. Industrial Marketing Management, 37(5), 487–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.04.002

- Bay, D., & Daniel, H. (2003). The theory of trying and goal-directed behavior: The effect of moving up the hierarchy of goals. Psychology & Marketing, 20(8), 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.10091

- Broodryk, J. (2006). The philosophy of Ubuntu: Some management guidelines. Management Today, 22(7), 52–55.

- Bruton, G. D., Pillai, J., & Sheng, N. (2021). Transitional entrepreneurship: Establishing the parameters of the field. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 26(03), 2150015. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946721500151

- Bushe, B. (2019). The causes and impact of business failure among small to micro and medium enterprises in South Africa. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 7(1), 1–26.

- Bylund, P. L., & Packard, M. D. (2022). Subjective value in entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 1–18.

- Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2010.00312.x

- Carsrud, A. L., Olm, K. W., & Thomas, J. B. (1989). Predicting entrepreneurial success: Effects of multi-dimensional achievement motivation, levels of ownership, and cooperative relationships. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1(3), 237–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985628900000020

- Chandler, G. N., & Hanks, S. H. (1993). Measuring the performance of emerging businesses: A validation study. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(5), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90021-V

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research: Choosing among five approaches. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Damane, M. B. (2001). Building competitive advantage from Ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa-executive commentary. Academy of Management Executive, 15(3), 34–34. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.2001.17571453

- Darley, W. K., & Blankson, C. (2020). Sub-Saharan African cultural belief system and entrepreneurial activities: A Ghanaian perspective. Africa Journal of Management, 6(2), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2020.1753485

- Dassah, M. O. (2018). Theoretical analysis of state capture and its manifestation as a governance problem in South Africa. TD: The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 14(1), 1–10.

- Dawson, C., & Henley, A. (2012). “Push” versus “pull” entrepreneurship: An ambiguous distinction? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 18(6), 697–719. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551211268139

- Dimitratos, P., & Plakoyiannaki, E. (2003). Theoretical foundations of an international entrepreneurial culture. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 1(2), 187–215. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023804318244

- Enslin, P., & Horsthemke, K. (2004). Can Ubuntu provide a model for citizenship education in African democracies? Comparative Education, 40(4), 545–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006042000284538

- Fatoki, O. (2020). Ethical leadership and sustainable performance of small and medium enterprises in South Africa. Journal of Global Business and Technology, 16(1), 62–79.

- Fukuyama, F. (1996). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Gade, C. B. (2012). What is Ubuntu? Different interpretations among South Africans of African descent. South African Journal of Philosophy, 31(3), 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/02580136.2012.10751789

- Gau, R., Ramirez, E., Barua, M. E., & Gonzalez, R. (2014). Community-based initiatives and poverty alleviation in subsistence marketplaces. Journal of Macromarketing, 34(2), 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146714522265

- GEM. (2019). Global Entrepreneurship monitor 2019/2020. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, London Business School.

- Georgellis, Y., & Wall, H. J. (2005). Gender differences in self-employment. International Review of Applied Economics, 19(3), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692170500119854

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Schaal, B. (1998). Metacognition in action: The importance of implementation intentions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(2), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0202_5

- Goulding, C. (2005). Grounded theory, ethnography and phenomenology: A comparative analysis of three qualitative strategies for marketing research. European Journal of Marketing, 39(3/4), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560510581782

- Haselip, J., Desgain, D., & Mackenzie, G. (2015). Non-financial constraints to scaling-up small and medium-sized energy enterprises: Findings from field research in Ghana, Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia. Energy Research & Social Science, 5, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.12.016

- Haugh, H. (2007). New strategies for a sustainable society: The growing contribution of social entrepreneurship. Business Ethics Quarterly, 17(4), 743–749. https://doi.org/10.5840/beq20071747

- Hauser, A., Eggers, F., & Güldenberg, S. (2020). Strategic decision-making in SMEs: Effectuation, causation, and the absence of strategy. Small Business Economics, 54(3), 775–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00152-x

- Hayton, J. C., & Cacciotti, G. (2013). Is there an entrepreneurial culture? A review of empirical research. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(9-10), 708–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.862962

- Hockerts, K. (2017). Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12171

- Hunt, R. A., Lerner, D. A., Johnson, S. L., Badal, S., & Freeman, M. A. (2022). Cracks in the wall: Entrepreneurial action theory and the weakening presumption of intended rationality. Journal of Business Venturing, 37(3), 106190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2022.106190

- Ismail, I. J. (2022). Entrepreneurial start-up motivations and growth of small and medium enterprises in Tanzania: The role of entrepreneur’s personality traits. FIIB Business Review, 11(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145211068599

- Kabonga, I., Zvokuomba, K., & Nyagadza, B. (2021). The challenges faced by young entrepreneurs in informal trading in Bindura, Zimbabwe. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(8), 1780–1794. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909621990850

- Karsten, L., & Illa, H. (2005). Ubuntu as a key African management concept: Contextual background and practical insights for knowledge application. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 20(7), 607–620. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940510623416

- Kim, J., Shah, P., Gaskell, J. C., & Prasann, A. (2020). Scaling up disruptive agricultural technologies in Africa. Washington DC: World Bank Publications.

- Kinoti, E. (2015). Trust: The missing ingredient for East African business integration. Africa Journal of Management, 1(4), 421–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2015.1105465

- Korobov, S. A., Moseiko, V. O., Marusinina, E. Y., Novoseltseva, E. G., & Epinina, V. S. (2017). The substance of a rational approach to entrepreneurship socio-economic development. Integration and Clustering for Sustainable Economic Growth, 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45462-7_24

- Lawson, R. (1997). Consumer decision making within a goal-driven framework. Psychology and Marketing, 14(5), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199708)14:5<427::AID-MAR1>3.0.CO;2-A

- Lee, J. (1996). The motivation of women entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women in Management Review, 11(2), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649429610112574

- Lucky, E. O. I., Olusegun, A. I., & Bakar, M. S. (2012). Determinants of business success: Trust or business policy? Researchers World, 3(3), 37.

- Lutz, D. W. (2009). African Ubuntu philosophy and global management. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(3), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0204-z

- Mair, J., & Noboa, E. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: How intentions to create a social venture are formed. In J. Mair, J. Robinson, & K. Hockerts (Eds.), Social entrepreneurship (pp. 121–135). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Makuvaza, N. (1996). Education in Zimbabwe, today and tomorrow: The case for unhuist/ubuntuist institutions of education in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research, 8(3), 255–266.

- Mamman, A., Kamoche, K., & Zakaria, H. B. (2018). Rethinking human capital development in Africa. In K. Amaeshi, A. Okupe, & U. Idemudia (Eds.), Africapitalism: Rethinking the role of business in Africa (pp. 99–136). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mangaliso, M. P. (2001). Building competitive advantage from Ubuntu: Management lessons from South Africa. Academy of Management Perspectives, 15(3), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001.5229453

- Mbigi, L. (1996). Ubuntu: The African dream in management. Sandton: Knowledge Resources.

- Mbigi, L. (1997). The African dream in management. Sandton: Knowledge Resources.

- Mbigi, L., & Maree, J. (1995). Ubuntu: The spirit of African transformation management. Sandton: Knowledge Resources.

- Mbiti, J. S. (1971). African traditional religions and philosophy. New York: Doubleday.

- Mbiti, J. S. (2015). Introduction to African religion. Long Grove, Il: Waveland Press.

- Metz, T. (2007). Ubuntu as a moral theory: Reply to four critics. South African Journal of Philosophy [Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Wysbegeerte], 26(4), 369–387.

- Meyer, K. Z., & Luiz, J. M. (2018). Corruption and state capture in South Africa: Will the institutions hold? In Warf, B. (Ed.) Handbook on the geographies of corruption (pp. 247–262). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Miles, R. E., & Snow, C. C. (1978). Organization strategy, structure and process. McGraw-Hill.

- Mpe. P. (2001). Welcome to Hillbrow. University of Natal Press.

- Murithi, W. K., & Woldesenbet Beta, K. (2022). The interaction between family businesses and institutional environment in Africa: An exploration of contextual issues. In O. Kolade, D. Rae, D. Obembe, & K. W. Beta (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of African Entrepreneurship (pp. 67–92). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Musara, M., & Nieuwenhuizen, C. (2020). Informal sector entrepreneurship, individual entrepreneurial orientation and the emergence of entrepreneurial leadership. Africa Journal of Management, 6(3), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2020.1777817

- Nickell, S. J. (1996). Competition and corporate performance. Journal of Political Economy, 104(4), 724–746. https://doi.org/10.1086/262040

- Nkondo, G. M. (2007). Ubuntu as public policy in South Africa: A conceptual framework. International Journal of African Renaissance Studies, 2(1), 88–100.

- Nuijten, A., Benschop, N., Rijsenbilt, A., & Wilmink, K. (2020). Cognitive biases in critical decisions facing SME entrepreneurs: An external accountants’ perspective. Administrative Sciences, 10(4), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10040089

- Nussbaum, B. (2003). African culture and Ubuntu. Perspectives, 17(1), 1–12.

- Nziramasanga, T. (1999). Report of the presidential commission of inquiry into education and training. Harare: CDU.

- Osiri, J. K. (2020). Igbo management philosophy: A key for success in Africa. Journal of Management History, 26(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMH-10-2019-0067

- Packard, M. D. (2017). Where did interpretivism go in the theory of entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 32(5), 536–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.05.004

- Packard, M. D., & Bylund, P. L. (2021). From homo economicus to homo agens: Toward a subjective rationality for entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(6), 106159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106159

- Patricia, P., & Scheraga, A. (1998). Using the African philosophy of Ubuntu to introduce diversity into the business school. Chinmaya Management Review, 2(2), 1–5.

- Peredo, A. M., & McLean, M. (2006). Social entrepreneurship: A critical review of the concept. Journal of World Business, 41(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

- Pinillos, M. J., & Reyes, L. (2011). Relationship between individualist–collectivist culture and entrepreneurial activity: Evidence from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor data. Small Business Economics, 37(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9230-6

- Plehn-Dujowich, J. (2010). A theory of serial entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 35(4), 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9171-5

- Pollack, J. M., Cardon, M. S., Rutherford, M. W., Ruggs, E. N., Balachandra, L., & Baron, R. A. (2023). Rationality in the entrepreneurship process: Is being rational actually rational? Introduction to the special issue. Journal of Business Venturing, 38(3), 106301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2023.106301

- Rayburn, S. W., Anderson, S. T., & Sierra, J. J. (2020). Future thinking: A marketing perspective on reducing wildlife crime. Psychology & Marketing, 37(12), 1643–1655. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21413

- Rayburn, S. W., & Ochieng, G. (2022). Instigating transformative entrepreneurship in subsistence communities: Supporting leaders’ transcendence and self-determination. Africa Journal of Management, 8(3), 271–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322373.2022.2071574

- Samkange, S., & Samkange, T. M. (1980). Hunhuism or Ubuntuism: A Zimbabwe indigenous political philosophy. Graham Publishing.

- Schuler, R. S. (1988). Personnel and human resource management choices and organisational strategy. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 26(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841118802600108

- Shimeles, A., Verdier-Chouchane, A., & Boly, A. (2018). Introduction: Understanding the challenges of the agricultural sector in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Shimeles, A., Verdier-Chouchane, A & Boly, A. (Eds.) Building a resilient and sustainable agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 1–12). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sibanda, P. (2014). The dimensions of ‘Hunhu/Ubuntu’ (humanism in the African sense): The Zimbabwean conception. Dimensions, 4(1), 26–28.

- Swanson, D. M. (2007). Ubuntu: An African contribution to (re)search for/with a 'humble togetherness’. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Education, 2(2), 53–67.

- Swartz, E., & Davies, R. (1997). Ubuntu – the spirit of African transformation management – a review. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 18(6), 290–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437739710176239

- Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914

- Tlaiss, H. A. (2015). Entrepreneurial motivations of women: Evidence from the United Arab Emirates. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 33(5), 562–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613496662

- Turyakira, P. K. (2018). Ethical practices of small and medium-sized enterprises in developing countries: Literature analysis. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 21(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajems.v21i1.1756

- Van der Wal, R., & Ramotsehoa, M. (2001). A cultural diversity model for corporate South Africa. Management Today, 17(6), 14–18.

- Veetikazhi, R., Kamalanabhan, T. J., Malhotra, P., Arora, R., & Mueller, A. (2022). Unethical employee behaviour: A review and typology. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 33(10), 1976–2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1810738

- Velenturf, A. P., Jensen, P. D., Purnell, P., Jopson, J., & Ebner, N. (2019). A call to integrate economic, social and environmental motives into guidance for business support for the transition to a circular economy. Administrative Sciences, 9(4), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9040092

- Venugopal, S., Viswanathan, M., & Jung, K. (2015). Consumption constraints and entrepreneurial intentions in subsistence marketplaces. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 34(2), 235–251. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.14.181

- Vorbach, S., Poandl, E. M., & Korajman, I. (2019). Digital entrepreneurship education: The role of MOOCs. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy, 9(3), 99–111.

- Wanyoike, C. N., & Maseno, M. (2021). Exploring the motivation of social entrepreneurs in creating successful social enterprises in East Africa. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, 24(2), 79–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/NEJE-07-2020-0028