Katrin Brack is one of the most important contemporary German stage and costume designers. She studied stage design at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf and has since worked for a number of renowned theatres in the German-speaking world. Since 2009, she has been a professor of stage design at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. Her work is characterised by a clear, precise visual language that usually seeks a reference to fine art. Brack knows how to achieve great and diverse effects with reduced means and materials. She has rightly been described as a maximum minimalist.

In the conception of her stage designs, different ideas come together. She looks for associations to concepts and tries to assign materials to certain circumstances. Initial ideas are given form and materially translated. The focus of her work is the creation of a desired atmosphere on stage. The way in which the set is used by the actors evolves during rehearsals; it becomes an actor in the play. According to Brack, the set needs actors and texts to come to life. Brack has received numerous awards for her stage designs and has been voted Stage Designer of the Year several times. In 2017, she was awarded the Golden Lion for her life’s work at the Venice Theatre Biennale. In 2019, she received the Hein Heckroth Stage Design Award. (text from Prague Quadrennial of Performance Design and Space 2023 (PQ)).

Thea Brejzek: Katrin Brack, thank you for meeting with me today, the day after your talk with dramaturg Götz Leineweber at PQ Talks 2023, in a packed hall with 800 scenography enthusiasts. In our conversation I would like to talk about your scenographic methods and the way you work with actors and directors, and also about your work as an educator and mentor in your role as professor of scenography at the Art Academy in Munich. Let me start by saying that to me your scenographic work is radical and uncompromising in the way it breaks open the system of the stage in space, time, body, and narrative. Is that how you see it?

(laughs) That sounds great because you are also a theorist, but I'm not. I find that ‘breaking open’, as you call it, exciting.

So, when you as a scenographer enter the stage, what happens to the space-time structure?

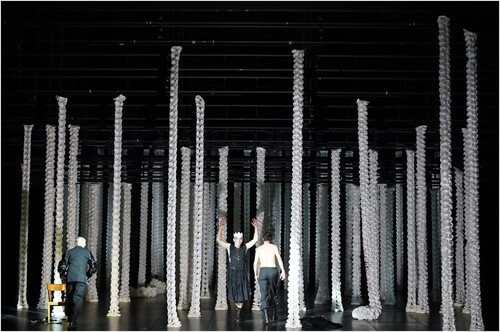

What happens? Firstly, the stage is usually in motion. And it's a movement that repeats continuously. For instance, back then at the Volksbühne with the confetti. That was the first thing … With the confetti, there was a discussion afterward, and critics said that it was both always the same and never the same. Because, of course, the blue, the red, they all fall differently. And that creates a sense of time passing but being both the same and not the same. So, my scenographies play along with the actors, or the actors often perceive the stage sets as fellow players. There was always the great fear from actors at the beginning that they wouldn't get enough attention because it would divert the focus from them. But it doesn't, because if something is the same all the time, you don't keep looking at it. The focus is on the actors. Are they equal to the scenography? In the best case, not exactly. The players have a completely different function, of course. But are they collaborators?

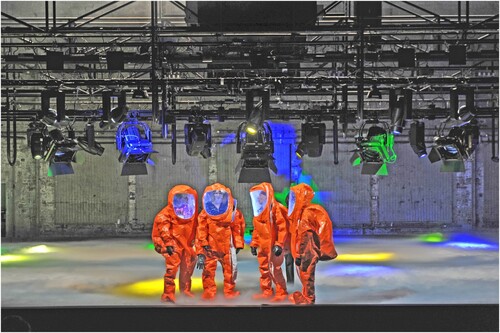

The actors in your work are challenged to be collaborators who develop a dynamic but also have autonomy. They often have to work (and play) with one particular element, but they also work against it. What we see during the entire performance is the direct confrontation of the actor with the material but also the actors’ physical and psychological struggle against the material.

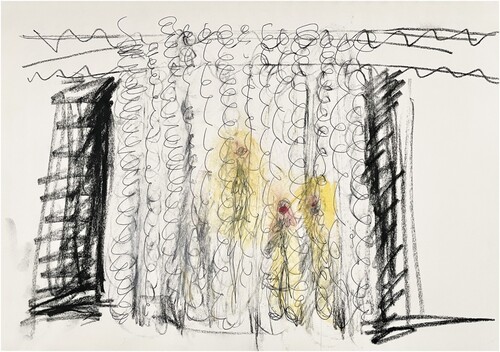

For example, in the Hermannsschlacht (Munich 2010), I had huge foam pieces, like those from a factory. Cubes, rectangles, and so on, on the stage. They were incredibly heavy. And these were what the actors had as their stage set; the agreement was that they build their stage set themselves. It was incredibly physically demanding to move those pieces and one actor had severe back problems and so the big pieces just disappeared after the performance. I thought it was wonderful when I saw them dragging those pieces around. Literally, carrying their territories around with them. The fog is another matter. It goes into the eyes. But you can avoid it. The actors told me during the dress rehearsal [for Iwanow, Volksbühne Berlin 2005], that the director Dimiter Gotscheff said, ‘That's too much; I can't see the actors anymore’. Then they came to me and said, ‘Let your stage set do its job. He's in the cafeteria anyway and only shows up later. And we're fine; if it gets too much, we can step aside and catch some air, so to speak’. And that worked well.

For the actor, to be in the fog, working with the fog, against the fog, and creating different constellations and configurations between characters would be difficult for the director to control. The material becomes at the same time poetic and threatening. The actor however, takes on a lot of individual responsibility.

Yes, yes. And it's not comfortable, of course. Well, what does comfortable mean? They can't sit anywhere. They stand on the stage the whole time. With the fog, they can play with it. They can disappear, even though they are standing in the middle of the stage, and reappear. But they basically stand on the stage the whole time and have nothing to hold onto.

Your stages require a specific type of actor. But they also require a specific type of director?

Right.

You have worked repeatedly with the same directors. And that makes sense because you have to find a common language; you want to have artistic friction, but in a productive way. Overall, how would you describe your collaboration with a director? What is important to you?

Actually, it's important that they can work with an almost empty stage. Because what I provide is not an empty stage, but they must be able to work as if it were. Because what I give you, on the one hand, protects the actors because it's spatially filling, and on the other hand, they have to deal with it because they stand there without a table, without a chair, nowhere to lean. And that requires the director to handle it. I'd say, sure, sit down on the floor or stand, walk or do something. Also, it requires actors who enjoy it. So, with the fog, I was a bit unsure at the beginning and thought, well, maybe we need a few things. And then the actors really said, no, we'll try. We'll try to do without everything. And the only thing at the end was a spray can that Ivanow used to spray a figure on the wall. Oh yes, and a remote control at the beginning to set the fog in motion because it's a crucial point. I like stages that are simple and stages that come and go with the actors, where things happen quickly. It's always the stage space, and it's always visible, no matter what is added to it.

So no walls, no structures, no decorative elements flown in, nothing. It always remains what it is.

Speaking of flown in, I did a piece with [director René ] Pollesch in Berlin called Are You Alright? [at Volksbühne Berlin 2022].

Oh yes, that was …

That was the rocket. And I really felt, of course, that that was also about Elon Musk and all that. It was constantly in the newspapers. There was a request 15 years ago from [the magazine] Der Spiegel to various artists and also set designers, what is home? At that time, I built a rocket from a toilet paper roll and quoted a philosopher whose name I unfortunately don't remember now, who said, look around because elsewhere we can be who we want to be. So, I sent the rocket with that sentence. And now, I'm going to Hong Kong in July to work with students, and I suggested – at first, they were a bit puzzled – but that each student builds a rocket as big as they are. And, yes, we would exhibit them because time is short. And always with this sentence, ‘because elsewhere we can be who we want to be’.

Yes, who we want to be.

And down here, we can't manage that.

That describes theatre as well.

Yes, yes.

On stage, we can be who we want to be. We create worlds. And every stage of yours that I've seen is its own world. A world that works with material and actors and light, but also very strongly with the immaterial element. So, the light, from a physics perspective, is material, but it's at the same time immaterial.

But with light, it's not like I don't see where it comes from. The spotlights are the crucial ones.

They are present.

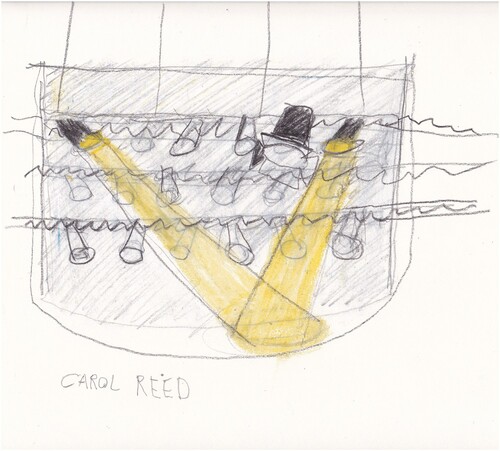

And they are always present. So, I always try to work with things inherent to theatre. Like the fog, it's nothing new, but it was usually used as an effect. I didn't do anything else apart from the fog. And that was new. And the spotlights, which normally hang from the ceiling, you don't see them because they are so big, and then the lights kind of magically appear from somewhere, they move. The spotlights themselves move. It was also nice when they opened the shutters; it felt like they were their eyelashes, fluttering. When you move them correctly they can be like humans, and then slowly, you see the shutters opening, and closing. In Carol Reed [Burgtheater Vienna 2017], they fell in love with each other; one came from the front, the other from the back, and then a third one intervened, and the first one got jealous again. So, we really tried to tell a story with them without changing anything. We only worked with what the spotlights bring, what they can do. Even the bridges move. And that is, yes, then it can have a very different effect. So, with Krankenzimmer No 6 [Deutsches Theater Berlin 2010], the spotlights were like surveillance, and there, along with the text, it had a surveillance character because they visited the actors like that, the spotlights pretending to be actors. In Carol Reed, I used them again, but there were three huge bridges, while in Krankenzimmer, there are nine shorter bridges, all different. And there it was the machine, machine–human, the theatre machine.

So, a choreography of the machine. Were the spotlights and bridge movements choreographed?

Yes, they were choreographed in the sense that it's tough for the poor technicians; they pull it all in. But you still can't plan it because actors can't be timed to the second. That means, with Carol Reed, sometimes it was precisely the right moment, and sometimes it was unfortunately too early or too late. But that's life too.

We always see the glitches and the errors. But we also like to see them. To see that not everything is synchronous. So, these spotlights, when we look at them, actually develop their own life. And also become actors in this performance.

Yes, and they turn everything into something!

It's a lot of fun for the actors.

Exactly. But the things need the actors. There was a survey by ‘Theater Heute’ asking if what one does is art or not. I said, my spaces don't think about whether they are art or not because they don't stand alone; they need the players to develop life at all.

The players need the material; the material needs the players.

Exactly!

What emerges from the fact that the material needs the actor, the actor needs the material? Does it start or create a provocation but also a collaboration?

Yes, through the players and the text, the material gains meaning. Before, it had no meaning. It's essential to me that it's nothing … So, it had no meaning before, except the one it has in its normal state. I just shift the context. I take it out of that and place it in another context. And as long as the performer and the material are not involved yet, it's still the old context. With them, it can become something new.

Exactly. In your work, you use the material, both the material and the immaterial, not dynamically or dramatically, as we may be used to, but you for instance let the confetti rain relentlessly, from the first minute to the last minute. Through this incessant action, the material takes on a completely different meaning. If you let confetti rain for three minutes, it's funny but if you let it rain for hours, then this material, which actually has no meaning or is banal, becomes meaningful, even existential.

Yes, in the best case. In the best case! It doesn't stop. And that is precisely the case with snow, this, where I read in the newspaper, because it is also physical, because older people were already outside after ten minutes. That was in Salzburg, Salzburg Festival, Molière [2007], it snowed for five hours. There were really two or three audience members who had to leave after ten minutes already and need medical assistance because the snow creates this shimmering effect, and you think, oh yes, over there, that's moving, it's going up, the floor and the walls are coming, and something is coming down from above. But nothing is coming. It's only here. And if you concentrate on it, and never look at the snowflakes, but at the people, and it's trickling all the time, it has a meditative quality, and it also has this physical aspect, where LSD stands for the eyes, which I liked very much.

Now Katrin, let's talk about your pedagogical work as a professor of scenographer at Art Academy Munich and in Hong Kong, amongst other international institutions. You are taking the train to Munich now to reconnect with your class who was here last night.

You have been an educator for many years. The profession of a set designer has changed a lot, as you have experienced throughout your career. There is an increasing autonomy in set design. But we also have many more women, not only as students in set design but also as professionals in practice.

[In Germany], the first one was Anna Viebrock, the second was me. And now there are many women. Before that, there were really only men.

How do you see the change in the profession, and how does it manifest in your educational work? And how do young female set designers assert themselves? How do young women establish themselves in the theatre industry?

Well, surprisingly well. They are also different in how they move and how they think about themselves. They are different, unlike me, for example. I grew up in a time where it wasn't about that. They have a completely different attitude toward it. They are very confident. Although I find it important that both boys and girls are in the class, they are sometimes better than the boys. I wouldn't say that against them. I always feel like they look in all directions more.

Yes, the young women look at everything.

While the boys are always so focused. It can be quite distracting, this here, right? No, they do it very well. But I think it has also changed a lot because there is no more money. I never had a problem with money and budgets. My sets are relatively inexpensive. I am expensive, but they are affordable. In general, there is not as much money today. But from the beginning, I made sure that students assume that they have very little. And I also find it interesting to work with less. And they are already doing that. We do things like … So, there's always a task; for example, they had the task of building a staircase. And I'm not interested in spiral staircases, but a completely normal staircase with apartment doors. As few walls as possible. And then, with sound alone, I want to hear a story in this staircase. And the staircase should be at a scale of 1 to 10.

And you hear, like this … Someone slowly going up the stairs, heavily loaded with groceries. Someone else coming quickly. I hear from the doors where the individual apartments are. And that's wonderful, and I want to see where the wiring is.

Yes, of course; at 1 to 10, you see all the details.

Humanity is so vast there.

You hear the doorbells and the living space.

Yes, yes. And I said, as raw as possible, like a shell. And I still want to hear the stories that happen there. That's it. Such tasks. And, of course, we also design plays.

Is the staircase a real staircase, is it photographed, researched, or fictional?

It's both. It's both because some just start building, and others research.

We must be able to do both. Although set design belongs to fine arts at the art academy, it has a significant applied component. They must be able to draw on the computer. They must have certain fundamentals; otherwise, they won't get an assistant position. Because, in the beginning, they have to do everything themselves.

And how many weeks or semester weeks would students work on such a task?

We did this relatively quickly, within a month. It's finished. And now, I'm going there, and the students want to present the project, of course. Then they will have a small exhibition, and that's why I'm going there.

Thea: And do you provide feedback? Do you invite someone else?

Yes, they invite all their friends, and they share it within the academy. Then they invite people from the theatre academy; we are not entirely involved, but we cooperate partially with them, but we are simply the art academy. They invite people from the HFF Munich [Hochschule für Film und Fernsehen], the film school, and invite the directors.

And throughout the year, you would present several such tasks?

Yes, of course, we have to make plays too. So both. There are always many challenges. As soon as the plays come, it becomes quite complicated.

Ah, yes, and then a dramaturg joins to do the text analysis?

Yes, I don't do that with them. I have discussions and jokes and such. Class discussions.

And how important is the physical model?

Very important. Very important. Because I can't do anything with it if they make everything on the computer. It always looks strange. What are those things that architects also do?

CAD?

Yes, but then they make an image of it with …

Yes, they create an axonometry and various renderings.

Yes, renderings! Exactly!

And it always looks new and like from a furniture catalogue.

Exactly, it looks like from a furniture catalogue. And that's why physical models are very, very important to me. You can also check. They can't just do everything on the computer. It doesn't work.

And what about hand sketches, hand drawings? Do they still do that?

Few.

Our architecture students, they don't want to hand draw anymore.

Yes, because, on the other hand, they can't really draw anymore.

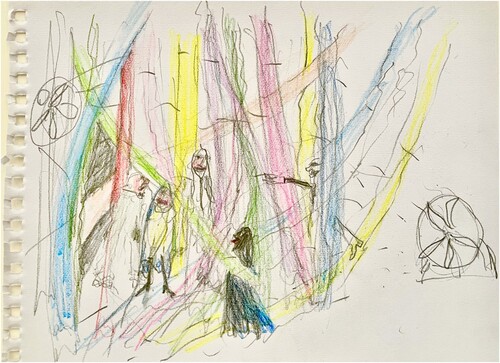

I want to make a new book. I want to put drawings in it now. I have a lot. I make drawings. They're not particularly good, but sometimes quite funny. But I need it. I always make a drawing at the beginning. So that's a bit of a challenge. But I said, people, I don't care if it's beautifully drawn or not. That's not the point. I don't want to talk about something where we just talk about it. Because you imagine something, and I imagine something else under the same thing. So, if I say cup, you have an idea of the cup and I do too. And already these two look so different. It makes no sense. So I want to see how it's supposed to look.

Yes, yes. Because this transformation or translation from word to image to space is actually the task of a set designer.

Yes, yes.

And that's the difficult part. This translation work from the word, when we say sketch, initially two-dimensional, then to space, three-dimensional, then with all the compositional elements, actually multidimensional. That's the complexity.

And you can tell many great things. Many great things. And when you have to do it, it happens to me too. I sometimes have ideas, and when I then make it in the model, I think, ‘Oh God, better not!’ Because somehow it looked better in my head.

But essentially, the model, or working with the model, is very efficient. Because you see if it works or if it doesn't. And you don't see it on the computer because the computer, the renderings, they lie, they seduce, where there is actually very little, because you can simulate and imagine a lot here on the computer that wouldn't stand on stage.

Yes, yes. And above all, in the model, you see, ‘Do I actually feel like looking at this now?’ And what often happens to me is I think, ‘Yes, actually, I don't feel like it’. So I'm the first one to see it, and I think, ‘Last night it looked so great, and this morning not anymore!‘

And this morning you think, ‘Hmm, not quite so!‘

Yes, not so good anymore!

(Both laugh)

Katrin Brack, thank you for your time.

Notes

1 See also McKinney, J.E. and K. McKechnie, 2016, “Interview with Katrin Brack.” Theatre and Performance Design 2 (1–2): 127–135.