ABSTRACT

In response to extreme violence and psychological abuse, survivors of modern slavery and human trafficking can experience complex mental health problems. Despite being a major public health issue, the evidence base for post-slavery mental health support needs and service provision is lacking. The aim of this study was to scope the mental health provisions available to survivors globally. A single point-in-time, Internet-based scoping study of on-line evidence sources was performed, guided by Levac and colleagues’ six-staged framework. Three hundred and twenty five service providers met the criteria. Most were located in Asia and South America, catered for a female population, and could be categorized as Christian Faith Based. Two overarching themes (Characteristics of Provision and Types of Mental Health Support) accounted for the results, each including ten sub-themes. Survivors’ mental healthcare was found to be informed by various models and to exist within a nexus of care whereby several services are offered to different vulnerable populations. Little information of evidence-based interventions and monitoring and evaluation was found. The study’s results are limited in scope of influence due to the Internet-based design and should be taken cautiously. More empirical, multidisciplinary, and multi-stakeholder research is required to improve understanding survivors’ support needs and to inform policies and practices that are culturally competent, survivor-centered, gender-inclusive and empowering.

Introduction

Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking (MSHT) entail forms of unfree labor involving the violation of migrant, labor, and human rights (Fudge, Citation2017). Obtaining an accurate picture of how many people are enslaved is problematic given the ongoing debate regarding definition, the different systems of measurement, and the hidden nature of the phenomenon (Broome & Quirk, Citation2015; Weitzer, Citation2015). A recent estimate is that the number of people enslaved worldwide is 40.3 million (Walk Free Foundation, Citation2018). In addition, the number of detected victims for sexual exploitation is growing, in particular minors and vulnerable migrants at risk of exploitation (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime[UNODC], Citation2018).

With regards to terminology, human trafficking has dominated the legislative, humanitarian and media landscape following the adoption of the Protocol on Trafficking in Persons in 2000 (United Nations, Citation2000). Whilst modern slavery has no legal basis within international provisions, and it is a term that is gaining increasing prominence within the academic, policy, and public discourse, not without criticism of its rhetorical appeal (Bravo, Citation2019; Quirk, Citation2011). For example, the UK Modern Slavery Act (The UK Government, Citation2015) defines it in relation to the 1926 Slavery Convention as:

The status or condition of a person over whom all or any powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised. Since legal ownership of a person is not possible, the key element of slavery is the behaviour on the part of the offender as if he or she did own the person, which deprives the victim of their freedom.

In simple terms, whereas definitions of human trafficking imply that people are recruited and transported, modern slavery acknowledges that individuals may become enslaved without necessarily being moved from their communities. This study adopted a broad working definition, and modern slavery is, therefore, conceived as an umbrella term that focuses on human-to-human exploitation in relation to activities such as forced sex work, domestic servitude, forced/servile marriage, debt bondage, forced labor in industries, forced criminal activity and the sale or exploitation of children.

Post-Slavery Mental Health

MSHT are public health issues that disproportionally affect vulnerable individuals such as young people, migrants, and those living in poverty (Chisolm-Straker & Stoklosa, Citation2017; Zimmerman & Kiss, Citation2017). Survivors have often experienced extreme physical and psychological abuses (Hossain et al., Citation2010), and addressing their mental health is now part of anti-trafficking policies in the UK and internationally (The UK Government, Citation2015; United Nations, Citation2000). The most recent systematic review available (Ottisova et al., Citation2016) highlighted a high prevalence of mental ill health amongst survivors in contact with support services. However, the same study also concluded that methodological problems and disparateness of the results are so significant as to limit both “comparability of studies and reliability of findings” (Ottisova et al., Citation2016). In addition, the majority of empirical studies has focused on women trafficked for sexual exploitation and those who have recently escaped exploitation, whereas less is known about women trafficked for other forms of exploitation, or the mental health needs of male and LGBTQ+ groups (Ottisova et al., Citation2016; Twigg, Citation2017).

Taking these limitations into account, what has been identified is a complex picture of mental ill health with depression, anxiety and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) being particularly prevalent (Abas et al., Citation2013; Borschmann et al., Citation2016; Oram et al., Citation2016). For young people who have been trafficked, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), adjustment disorders, and complex PTSD are also common (Ottisova et al., Citation2018; Stanley et al., Citation2016; Wood, Citation2020). This picture looks similar across different contexts and populations, regardless of the type of slavery (Katona et al., Citation2015). However, the prevalence of similar mental health problems affecting survivors of violence and abuse does not necessarily indicate that the response should always be the same (Betancourt et al., Citation2014; Gajic-Veljanoski & Stewart, Citation2007); and in fact variations in support needs across types of exploitation are being further investigated (Rose et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the evidence of effects of interventions with survivors is sparse and far from rigorous (Wright, Citation2021; Brunovskis & Surtees, Citation2007; Dell et al., Citation2017; Ottisova et al., Citation2016). Finally, no research has tested “the potential to adapt various therapies for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault or refugees such as, for example, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), trauma-focused CBT (TF-CBT), peer-support and psycho-education” to cater for MSHT survivors’ support needs (Hemmings et al., Citation2016, p. 5; Shigekane, Citation2007), although this may be a sensible practical choice to make on behalf of service providers.

Nevertheless, lack of research does not necessarily equate to a lack of service provision. There is a question as to where survivors get support for their mental health and what the evidence base is for the provisions offered. Statutory mental health services, such as those provided within the UK, might offer some support to survivors who are able to access and navigate the system (Westwood et al., Citation2016); but the training needs of healthcare professionals to best support this population are still in development (Thompson et al., Citation2017; Williamson et al., Citation2019). Concerns about authority figures, mistrust in the system, immigration status, and language barriers may mean that this route is problematic (Stanley et al., Citation2016).

Globally, most support for survivors is delivered by the third sector, e.g., Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). This often includes a mental health component. However, what these organizations provide, to whom and the evidence base underpinning such services have not been explored or mapped in a systematic way on a global scale. To start to address this gap, a single point-in-time, internet-based study was conducted. By undertaking a scoping exercise of on-line evidence sources, we sought to (1) explore the mental health provision offered by third sector organizations to survivors of MSHT and (2) discuss the results against available literature relating to MSHT survivors’ mental health care.

Materials and Methods

Terms such as scoping study, evidence mapping, rapid review and literature mapping are often used interchangeably to describe the process of producing a topographical account of a topic, which has not been synthesized before in order to guide future research (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The current study was inspired by the following definition (Colquhoun et al., Citation2014, p. 1291).

A scoping review or scoping study is a form of knowledge synthesis that addresses an exploratory research question aimed at mapping key concepts, types of evidence and gaps in research related to a defined area or field.

In particular, our design adapted the framework of Levac et al. (Citation2010), which was originally proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), and further systematized by Peters et al. (Citation2017). We aimed to map and understand trafficking and post-slavery mental healthcare in third sector organizations with an on-line presence at one point in time (i.e., January to June 2018). According to this framework, a scoping review is organized into six key stages: 1) Identifying the research question; 2) Identifying relevant studies; 3) Study selection; 4) Charting the data; 5) Collating, summarizing and reporting the results; 6) Consultation (optional). As this was not a review of the literature and did not include academic publications, these stages were adapted for the purpose of scoping, identifying, and selecting relevant on-line information in relation to mental health service provision delivered by third sector organizations. The sixth optional stage of expert consultation was not conducted. This was due to time and funding constraints and sufficient fieldwork-based knowledge and experience within the research team. As the research used publicly available data from the Internet ethical approval was not required.

Identifying the Research Questions

The following research questions guided the internet-based scoping study: 1) What does an on-line single point-in-time study tell us about the state of the mental health provision for MSHT survivors on a global scale as evidenced in on-line sources? For example, what type of organizations offer mental health support? What therapeutic approaches are available?; 2) What do on-line sources tell us about mental health support offered to MSHT survivors? ; and 3) To what extent is the provision of mental healthcare informed by research?

Identifying Relevant On-line Sources

In scoping reviews, searching “may be quite iterative as reviewers become more familiar with the evidence base, additional keywords and sources, and potentially useful search terms may be discovered and incorporated into the search strategy” (Peters et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, we developed a six-stage, multi-strategy approach to identify relevant organizations. All searches were conducted on-line between January and June 2018 to provide a snapshot of mental health provision at a single point in time.

Free text search using the internet search engine Google. As recommended by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), broad keywords and search terms were adopted to enable the breadth of the available information to be covered. Search terms were developed relating to the four key concepts underpinning our review question: “human trafficking”; “modern slavery”; “mental healthcare”; and “NGOs”, and combined using Boolean operators. In particular, the search terms used were a combination taken from four domains related to: MSHT (“slavery”, “modern slavery”, “human trafficking”, “trafficking”, “anti-trafficking” “post-slavery”, “post-trafficking”); mental health (“mental”, “psych*”, “trauma”, “counsel*”); the third sector (“NGOs”, “organizations”, “services”, “provision”); and location consisting of toponyms for world regions (e.g., Southeast Asia) and country names (e.g., Ghana). With this search strategy, we pilot searched one world region (e.g., Southeast Asia), and this suggested that screening 200 hits per search terms’ combination led to data saturation. Therefore, we decided to screen 200 hits using five sets of terms’ combinations from the four domains, corresponding to 1,000 hits per each of the ten world regions we used, as described below (i.e., total hits screened N = 10,000). Furthermore, as this search strategy was returning excessive numbers of hits – where results were frequently consisting of academic publications or news articles, and few service providers (8%) – more purposeful search strategies were developed (see below 2, 3, 4, and 6).

Reviewing relevant United Nations agency websites for information. These were: International Organization of Migration(IOM), International Labor Organization(ILO), UNODC, World Health Organization, United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and Empowerment, UN Human Rights Council and United Nations Children Fund;

Reviewing websites of the main world regional organizations: the European Union, European Union Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection, Association of South East Asian Nations, South Common Market, South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation and Organizations of American States;

Searching specific slavery/human trafficking directories or indexes, three of which were global (End Slavery Now, Global Modern Slavery Directory, Slavery Today Non-Governmental Organization listing) and three specific to the United States of America (Abolition Now, National Human Trafficking Directory and Charity Navigator). Where possible search filters were applied within a directory to identify more easily those organizations providing mental health support;

Snowball sampling: if an organization’s website referred to another service providing relevant mental health support, then this too was considered for inclusion; and

When a relevant report was made available from an organization website, this was downloaded and scrutinized, including the five most recent global reports available on human trafficking at the time the searches were completed (i.e., IOM, Citation2017; U.S. Department of State, Citation2017; United Nations, Citation2015; UNODC, Citation2016; Walk Free Foundation, Citation2016).

To assist with managing the collation, screening, and extraction of data, the information obtained was divided into ten geographical regions (i.e., North America, South America, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia, the Pacific, Europe, Africa, continental Asia, and the Far East). To ensure consistency, two researchers independently screened one region (Southeast Asia). Following comparison of the results, 85% consistency was obtained, and the remaining regions were screened by one researcher. No software was used for the management of the results of the search. The reviewer collated the sources by copy-pasting relevant text from organizations’ websites onto a MS Word file and shared it in a secured university cloud drive with the research team. The team then independently reviewed the first 20%, or 20 sources extracted and collated (whichever was the lower); divergences in relation to the inclusion of a source have been resolved by team discussion.

On-line Sources Selection

Organizations were eligible for inclusion if, according to the information provided in their websites or other on-line documents, they met one of the characteristics of the following three categories:

They were devoted to designing, delivering and evaluating mental health support packages for survivors of MSHT;

Their service offering included a mental health support package and made available resources on it;

They stated that they provided some mental health support as part of an array of services.

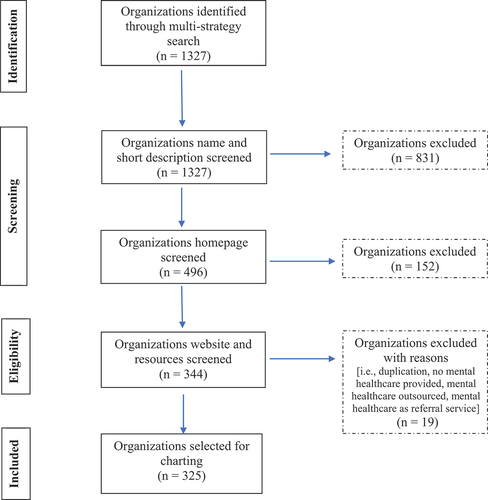

Organizations in Categories 2 and 3 were included if, along with other vulnerable groups, they also provided support to MSHT survivors. International, or large organizations supervising and funding services delivered directly by local partners were included too. Only on-line sources published between January 2000, the year of the adoption of the Trafficking Protocol, and June 2018 and in the following languages were reviewed: English, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French. The authors undertook all translations. Organizations were not included if they had no website or visibility on the Internet, or they did not provide information in one of the aforementioned languages. summarizes the selection of organizations in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Main reasons for exclusion were 1) duplication, 2) no provision of mental healthcare, and c) mental healthcare offered only in terms of referral to other specialized services, and/or being outsourced.

Charting the Data

Details and data from included sources have been extracted using a standardized data extraction form for the organizations in Categories 1 and 2, and subsequently summarized in an Excel file. Given the smaller amount of relevant information available from NGOs in Category 3, relevant data from those were input directly into the Excel file. Extraction of data from two sources was verified by the team members and discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. Information was charted in two broad categories:

Evidence source details and characteristics (URL and general data on the organization, such as name, target population/s, location/s of intervention, if denominational).

Mental healthcare provision (i.e., scope of mental healthcare within the generic support available; specificity of interventions/approaches for a survivor population; type of support available; any written reports; any research studies conducted by the organization or cited to support the work undertaken)

Following Peters et al. (Citation2017), charted findings were both organized in a tabular form and thematically analyzed to offer a descriptive synthesis. Deductive thematic analysis guided by the research questions was performed to narratively summarize results. Analysis was informed by Ritchie and Spencer’s (Citation1994) five-step process entailing carefully reading the data (i.e., familiarization); identifying and grouping them into categories (i.e., thematic framework and indexing); and finally charting, reading and discussing results (i.e., charting, mapping and interpretation).

Results

Our single point-in-time study yielded a total of 1,327 organizations, and 325 of these met the inclusion criteria. organizes key numerical data into the main world areas searched. The table includes data in relation to the three categories guiding organizations’ inclusion whether serving survivors of MSHT exclusively whether denominational if operating transnationally and the gender of target beneficiaries.

Table 1. Synthesis of numerical results per world areas.

Information regarding the gender of the target populations is missing for 189 organizations. Among these organizations, beneficiaries can be assembled into the four following main groups: minors and young people (n = 71); victim/survivors of MSHT, violence, and human rights abuse (n = 38); vulnerable communities (n = 19); and vulnerable workers, migrants and refugees (n = 17). Among the 10 organizations with service for males, only four declared catering exclusively to men (n = 1) or boys (n = 3). Only one organization reported serving MSHT offenders. Two hundred and thirty-two organizations did not declare any religious affiliation, one stated it was non-denominational and the rest (28%, n = 92) reported to be associated with the Christian faith. Organizations active within the same world area (n = 8) were not included within the organizations counted as transnational; this means that 68% (n = 220) of included providers appeared to be local. Results are described under the two overarching themes: Characteristics of Global Provision and Types of Mental Health Support. summarizes the subthemes which relate to these superordinate themes. All quotes are from publicly available sources, for example, NGOs’ websites.

Characteristics of Provision

The term mental health, articulated with information describing specific psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g., interpersonal therapy, trauma-informed Cognitive Behavioral Therapy-(CBT), and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing-(EMDR), is used by the four organizations belonging to Category 1 (i.e., Helen Bamber Foundation, Sanar Wellness Institute/Polaris, EmancipAction and Freedom Fund with its partners), and by three organizations in Category 2 (i.e., Salaam Baalak Trust in India, Deborah’s Gate in Canada, and Hagar International in Southeast Asia). The term mental health was mentioned by nine other NGOs, which were not MSHT specific, but broadly served vulnerable migrants and victims of abuse (the only MSHT specific provider was Washington Anti-trafficking Response, a USA-based provider). The involvement of/referral to a clinical team, able to provide psychiatric consultation, was mentioned by 2% (n = 7) of organizations.

By contrast, a variety of terms to generically describe the mental health support offered were identified. These included psychological, psycho-social, emotional support/intervention/assistance, therapeutic care, individual, family, and group counseling, and victim- and community-centered (psycho)therapy. This broad mental health support is accompanied by several descriptors, such as comprehensive, holistic, ecological, integral approach/program and continuum of care. All these terms indicate that mental health support is offered within a wider package of care, including other services (e.g., medical care, financial support, legal assistance, vocational training, social work support, child support, worship/spiritual guidance, nutrition, life skills training, accommodation/shelter, education). Results indicate that such package of services characterizes all NGOs in Category 3, n = 37 NGOs in Category 2, and one in Category 1 – meaning that 86% of our sample offers some form of integral support. In Argentina, for example, “integral assistance” is part of the national policy against human trafficking informing the Program for Rescue in 2008 (U.S. Department of State, Citation2017), whose core objective is to offer psychological, social, medical and juridical assistance, from rescue to the witness statement (Gatti, Citation2013). The French Organization International Organization Against Modern Slavery (Organization Internationale Contre L’esclavage Modern/ OICEM) “offers legal assistance, psychological support and socio-educational support to any person identified as a victim.” Global Welfare Organization (GLOWA), in Cameroon, provides a program of support to victims of child slavery and trafficking through access to funds, basic healthcare, counseling, paralegal support, and programs for the development of marketable skills (e.g., mechanics and tailoring).

As suggested in , the vast majority of providers (88%) appeared to have integrated MSHT survivors with other vulnerable groups. For example, the organization Medica Zenica in Bosnia and Herzegovina:

continuously offers psychosocial and medical support to women and children victims of war and also post-war violence, including victims of war rapes and other forms of war torture, sexual violence in general, domestic violence survivors, as well as victims of trafficking in human beings.

While a rationale is not provided for assimilating these different groups, we also noted a lack of availability of protocols for Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) and a lack of evidence-based practice for working with survivors. Results revealed that only the four NGOs in Category 1 have resources available regarding research informing their interventions. Even basic descriptive statistical information about the numbers of people accessing the organization was generally missing. An exception to this was the Cambodian Women’s Crisis Center (CWCC) which states:

In 2016, 847 clients (567 survivors and 280 relatives) received services from the CWCC, from all four of our locations; […]. There were 342 domestic violence cases, 146 sexual abuse cases and 79 human trafficking of which were 175 underage survivors.

In addition, the Rivers of Life Initiatives (ROLi) provide some information regarding methodology and mechanisms of self-assessment:

a survivor driven methodology that offers a peer facilitated and adult supervised fun-filled self-assessments, creative workshops and collaborative work integrated with elements of game playing in the context of risk reduction [a scorecard-based game called The Young Key Population].

However, even in these two instances, the rationale for why particular groups and methods of assessment have been selected is not explicitly addressed.

Geographic, socio-cultural variations were occasionally observed in the provision of mental health support to survivors. This variability appears to reflect the presence of specific vulnerable groups in some cultural contexts. For example, the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center (U.S.) has designed Nokomis Endaad (Grandmothers’ House, in Ojibwe):

A culturally based and trauma informed dual diagnosis treatment programme for American Indian women who suffer from mental illness, sexual trauma and chemical addiction.

In Haiti, five out of six organizations were for restavek children exploited as domestic servants. Nonetheless, besides these specific socio-cultural groups, when an organization was found to be gender specific, this was often female orientated (see, ), with an explicit focus on sexual exploitation and violence in 33% of the cases, either within forced sex work or in the domestic realm. One NGO included in this study indicated that they catered to the needs of LGBTQ+ groups (n = 1), its main focus being HIV/AIDS and sex workers (i.e., PT Foundation in Malaysia).

Thirty-two percent of the included NGOs indicated that they operated across world areas or across countries within the same geographical region. NGOs that provide services in one locale may also operate in other national contexts, have their headquarters with several local partners/cells, or be part of a network. For example, The Anonymous Ways Foundation (based in Hungary) offers: “full rehabilitation and reintegration to victims of human trafficking, mainly sexual exploitation and prostitution including psychological assistance.” The parent organization is the Canadian Servants Anonymous Foundation, which “has been serving the victims of human trafficking and prostitution for 27 years.”

Some provision is also affiliated with religious missionary work (see, ). Whilst some of the religious organizations have underpinning philosophies that are based on the Christian faith, others actively integrate components of worship into the support they offer. For instance, Ezekiel Rain – an organization based in Thailand states:

Our model of aftercare places trafficking survivors in safe families rooted in Christ’s love and committed to prayer and worship. We believe that the family is God’s vehicle for restoration and that national house parents (mothers and father) are best positioned to connect with the hearts of the survivors in their care and provide them with individualized care.

Finally, results revealed that the involvement of MSHT survivors in designing and delivering mental healthcare is scant, as seven providers (2%) stated offering peer-support, peer-led groups, and/or survivor-led services or assessment (i.e., King’s Daughter’s Organization in Namibia, Shared Hope International in Canada, My Life My Choice in U.S. ROLI in the Philippines, Sanjog and Integrated Rural Community Development Society [IRCDS] in India, and ADPARE in Romania). In some cases, peer-led support is a stand-alone option, whereas for other NGOs it is an adjunct to either individual or group therapy. For example, IRCDS offers both group therapy and peer-led support designed to empower their female clients “in such a way that they can address their life cycle themselves.”

Types of Mental Health Support

As mentioned, mental healthcare is overwhelmingly offered within a package of services, which can be described as a holistic service devoted to jointly catering to the psychological and social needs of MSHT survivors. Connected to this broad model is the type of support referred to as psycho-social (offered by 32 NGOs). Trauma-informed is another specific type of support found – with all four NGOs in Category 1, 33% (n = 27) of NGOs in Category 2, and eight providers in Category 3 offering it (N = 39). Sixty-seven percent of the NGOs mentioning this approach are located in the Anglophone Western world, especially North America, followed by Australia, and the UK. A third type of support identified is one based on artistic and bodily experiences/expressions. This was offered by 22 providers, both as an adjunctive therapy and also within the integral model. While art-therapy was most commonly observed (n = 14), dance and Dance Movement Therapy (DMT), gardening, yoga, mindfulness, aromatherapy, and equine therapy were also found. For instance, SANAR Wellness Institute, in partnership with Polaris, integrates trauma-focused CBT and EMDR strategies with restorative yoga, expressive art therapy, mindfulness and sensory-based interventions (i.e. breathing techniques, aromatherapy, and animal-assisted therapy).

Where this distinction was made available, group-based support (n = 22) appears to slightly outnumber individual support (n = 17). A variety of descriptors (e.g., group counseling, psychotherapeutic groups and group discussions) are available and no details are offered around how groups were conducted, who facilitated them, or what structured therapeutic input was provided. Sharing some features with this type of support, community-based approaches to intervention projects were also found (n = 16), where the members of the group belong to the same, often rural, community.

Another distinction in the type of support available is between residential and outreach. The results indicate that 39 NGOs offer accommodation to their clients, which are variously called shelters, safe houses/homes, or residential services. The residential approach is consistent with the model of integral care found in most providers. Congruent with this model are also two other types of services, life skills training and economic empowerment, which are devoted to supporting the mental wellbeing of clients in terms of fostering their self-esteem and emotional and financial independence, to better reintegrate into society. These services – which include vocational training and job placement – are mentioned by 22 NGOs.

Within the realm of training, the provision of computer literacy and basic technological skills to survivors has been identified (n = 3), as well as the use of digital programs for M&E purposes, information collection and sharing, and victim case management and support (n = 2). A few (n = 3) telephone and internet options for remote counseling and referral were found. In addition to crisis intervention, this type of remote support aims to reach those who cannot travel to an organization’s base, due to ongoing conditions of exploitation.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, no research has sought to review third sector provision of post-MSHT mental healthcare on a global scale. Despite capturing a short single point in time, our internet-based review of on-line sources returned a composite picture of this provision. Our findings reflect the established complexity of MSHT aftercare (Zimmerman et al., Citation2006). In this complexity, specialist mental healthcare support for survivors is scant, and both mental healthcare and survivors are blended with other services and populations. Results suggest that different types of NGOs can provide individual, group- or community-based support, informed by a range of different models – the main ones being trauma-informed, psycho-social, and art therapy – with or without the accompaniment of a residential service. Whilst variety may not necessarily be problematic, this complexity may mean that survivors cannot identify the most appropriate place to access mental healthcare; there may be a lack of choice in a given locale regarding what type of support is offered; or conversely there may be “black spots” where no provision is available at all.

Whilst studies focusing specifically on the mental health sequelae of MSHT have highlighted that survivors may have a diverse array of problems (Hopper & Gonzalez, Citation2018; Mumey et al., Citation2020; Ottisova et al., Citation2018), the unique nature of these are at risk of being lost as survivors of different types of MSHT are often grouped with other vulnerable populations for the provision of services. Albeit used in most observational studies in this field (Ottisova et al., Citation2016), there is a dearth of evidence both against and in favor of this approach (Hemmings et al., Citation2016), which assumes that survivors share common characteristics or experiences with others, such as refugees, asylum seekers, and those who have experienced trauma and abuse. The lack of tailored assistance to specific survivor populations has been observed (Hemmings et al., Citation2016; Ross et al., Citation2015), whilst support needs’ differences within the MSHT population are being identified, for example, between labor and sex trafficking survivors (Hopper & Gonzalez, Citation2018; Rose et al., Citation2020). This emerging evidence base raises the question of whether services can assume that the commonalities between survivors of difference forms of MSHT, and other groups, justify the continuation of generic mental health provision. Also outside the field of health sciences, attempts to neatly separate experiences of MSHT survivors from those of vulnerable migrants have been challenged (O’Connell Davidson, Citation2013). To start to address this issue, research is advancing to understand which mental health interventions have efficacy, either for MSHT survivors specifically (Wright et al., Citation2021; Oram et al., Citation2018) or for a mixed population (Powell et al., Citation2018). In fact, even if some conceptual models were developed highlighting similarities in experience and need between trafficked women, women experiencing sexual abuse and domestic violence, and migrant women, for example, (Zimmerman et al., Citation2003), there is need for interventions, and dynamic and flexible evaluations to take into account specific contexts, factors, and actors involved in post-trafficking care (Kiss & Zimmerman, Citation2019). Beyond these observations, for frontline practitioners, grouping MSHT survivors with others, who have experienced health and social vulnerabilities and/or trauma, appears to represent a pragmatic decision-making process.

Further reflections can be formulated in relation to what is broadly referred to as a trauma-informed approach. This model is established in existing academic and practice scholarship which advocates trauma-informed support in MSHT mental health aftercare, often toward treating PTSD symptoms (Wright et al., Citation2021; Dell et al., Citation2017; Hopper, Citation2017; Human Trafficking Foundation, Citation2018; Katona et al., Citation2015). Findings of this scoping study suggest that frontline provision does not appear to be uniformly and explicitly informed by this model, with 12% of the included NGOs mentioning it. Whilst there appears to be a disjuncture between the emerging academic discourse, in particular that informed by a biomedical model, and what is happening in practice, this needs to be investigated further. From the information obtained, it is not clear whether this discrepancy relates to a genuine difference in philosophy and therapeutic activity or to a difference in how academics and service providers label what they do. NGOs employ many different practices, often within a package of services. This complex and varied reality does not match the relatively unanimous Western biomedical scholarly knowledge base on what post-slavery mental healthcare should provide (Chisolm-Straker & Stoklosa, Citation2017). To fill this gap – which seems to be a “quality chasm” between what is known to be effective and practices (IOM, Citation2001) – more research integrating bio-psychiatric sciences, practitioners’ and users’ experience and perspective is needed (Lazzarino, Citation2020).

Similar observations could be drawn in relation to a further type of support identified: artistic and bodily experiences/expressions. Provided within a framework emphasizing social, cultural, community engagement and social prescribing, these methods are gaining momentum in mental health (Fancourt et al., Citation2021), and their suitability to a survivor population is also promising (Kometiani & Farmer, Citation2020; Namy et al., Citation2021). Whilst it could be argued that organizations could and should be clearer on their websites about the theoretical underpinnings of their interventions and their M&E processes, the purpose of having a presence on the internet needs to be considered. For example, this study has taken the stance that information on the Web is aimed at survivors seeking support. However, NGOs may have a Web presence primarily aimed at seeking funding or attracting resources. This would have an impact on the information made publicly available and the way an organization presents itself (see also limitations below).

The language of integration is common within mental healthcare (Patel et al., Citation2013). This indicates that any given organization may include, or integrate, mental health support within its provision. However, it does not account for variation between organizations or contexts. The analysis presented here, instead, suggests that post-slavery mental healthcare could be better conceptualized as belonging within a nexus of care. Nexus of care does not constitute a new concept per se, it stands more for a different way of looking at the integral/holistic model as formed of various connected elements (such as medical care, financial support, and accommodation). These elements should be integrated in attunement with specific contexts and users. Organizations may provide a range of services, but it is not the case that each organization provides an exhaustive package of all services that a survivor may require. Therefore, between different services, what mental healthcare is integrated with varies. Similarly, providers of multiple services, under the auspices of one organization, may run the risk of being a “one-stop-shop” (Barner et al., Citation2018; Hemmings et al., Citation2016). This picture indicates that there is variety in support needs and services, and offers potential benefits in enabling survivors with complex needs to access integrated care and multiple specialisms within a single setting. It does not however allow for that variety, or the different services within it, to be understood any further. Understanding integrated support – which is the standard model recommended by the Protocol on Trafficking in Persons (United Nations, Citation2000) – as being offered within a nexus allows for the dissection of support. As a new lens, it paves the way for an approach that leads to improved understanding of a context- and user-centered post-slavery mental health care on a global basis.

Co-production and user involvement are increasingly central to the design, delivery, and evaluation of mental health services (Palmer et al., Citation2018; Puschner et al., Citation2019). By involving all relevant stakeholders (including those with lived experience), it is assumed that services will be produced which are fit for purpose and meet service users’ needs. An active role in their recovery and reintegration is increasingly attributed to MSHT survivors (Curran et al., Citation2017; Laurie et al., Citation2015), their voice as activists and advocates is also growing, and their involvement in shaping the services that are provided to support their recovery is recognized as crucial (Steiner et al., Citation2018). However, survivors’ involvement is still largely lacking.

Our results indicate that some survivors’ voices appear less heard than others, notably those of men and LGBTQ+ groups. In the wider literature, few attempts have been made to rectify the lack of attention given to these groups who have experienced slavery and exploitation, including of a sexual nature (Fehrenbacher et al., Citation2020; Martinez & Kelle, Citation2013; Pocock et al., Citation2016; Surtees, Citation2008). Understandably, the hyper-visibility of specific groups (i.e., women and girls) may not fully reflect the actual need for post-slavery mental health care. This results in a further implication of this study: there is a need for both research and services to understand and meet the mental health needs of these minority groups, according to their socio-cultural characteristics.

One-third of the included organizations operate across world areas or across countries within the same region, and several more appeared to be based in a specific faith (e.g., Christianity). As mentioned, the transnational nature of some provision can be understood in relation to religious missionary work. While religion and spirituality have been shown to be beneficial in mental healthcare (AbdAleati et al., Citation2016), it is the religious/spiritual inclination of beneficiaries that should be respected, not that of the provider. Accordingly, mental healthcare should not be offered dependent on religious conversion or worship; and a by-product of mental healthcare support should not be cultural conversion. Therefore, attention must be paid to the cultural competence of the mental health service offered, in order to mitigate the threat of a uniform transnational provision, modulated, for example, onto the Western concept of trauma. Mental health support should instead be tailored to specific contexts and needs, including spiritual needs. Research is starting to advance in this sense (Pocock et al., Citation2020), and better evidence and practice appear urgent, in light of the multicultural nature of the MSHT victim/survivor population, and the diverse cultural sensitivities around what constitutes mental health, or other cultural barriers (Lazzarino, Citation2014; Fukushima et al., Citation2020).

Limitations

This study aimed to answer relatively unexplored questions following a single point-in-time internet-based scoping review design. However, scoping reviews present several intrinsic limitations, such as sizable number of included sources, multiple search strategies, and high risk of bias (Sucharew & Macaluso, Citation2019). The research utilized the Internet as both a tool and object of research enquiry. This presents additional limitations in terms of the nature and breadth of the information obtained. Organizations with no presence on the Web, or in a language different from those utilized in this review, could not be included. This may have impacted the representation of some of the geographical regions (the Middle East and Russia, for example) in the dataset. Organizational websites may not have accurately represented or provided information around the mental health services available to survivors. For example, many websites, and in particular in very low resource settings such as Africa, contained minimal information pertaining to their endeavors, but it should not necessarily be concluded that their services were non-existent. In a review such as this, it is difficult to discern the motivation behind the presentation of information on a website and the intended audience. Many NGOs may choose to have a lower profile on the Internet to create an environment that is accessible and safe to victims and survivors. The Internet may be a source of information, but also a tool to take advantage of survivors’ vulnerabilities. NGOs have to be careful of how they disseminate information regarding their mental health services in a manner that does not contribute to re-victimization. Similarly, survivors may be wary of accessing on-line sources to identify services, due to the role the Internet can play in leading vulnerable people into trafficking situations. The limited information gathered around evidence informing practice and M&E does not necessarily mean that this is not undertaken internally, or that the interventions provided by the organization are not based on a robust evidence base from research literature or practitioner training. Finally, despite our comprehensive multi-strategy search, the findings represent a captured point of time analysis and due to the fleeting nature of the Web (Devan et al., Citation2019), subject to change and updating.

Conclusion

This single point-in-time, internet-based scoping study of third sector provision indicates that globally a plethora of services are available to support survivors mental health. Service provision operates within a nexus of care often for an array of different vulnerable populations. The Study’s results are limited in scope of influence due to the focus on internet-based resources and should be taken cautiously. For this reason, more empirical, multidisciplinary and multi-stakeholder research is necessary to improve understanding and practices of the support offered, its evidence base and the M&E processes. Further research lines should critically expand on mental healthcare provision in light of MSHT as a global discourse, focusing on the economic and political structures informing some of the key issues in MSHT critical studies that we have also identified in this study (e.g., trafficking-migration nexus; biomedicine v frontline practice and alternative medicines; Western- and religion-informed model v local contexts and survivors’ plethora of voices; gender disparity in provision; academic v practice divide). Embedding survivors voice within these processes is required in order to develop culturally appropriate, gender-inclusive and survivor-centered mental health support, policies and practice.

Author Contributions

Study design: NW and RL

Data collection and analysis: RL

Study supervision: NW and MJ

Manuscript writing: RL, NW and MJ

Critical revisions for important intellectual content: RL, NW and MJ

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study were derived from resources available in the public domain and a full list of them is available from the corresponding author, RL, upon reasonable request.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abas, M., Ostrovschi, N. V., Prince, M., Gorceag, V. I., Trigub, C., & Oram, S. (2013). Risk factors for mental disorders in women survivors of human trafficking: A historical cohort study. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-204

- AbdAleati, N. S., Mohd Zaharim, N., & Mydin, Y. O. (2016). Religiousness and mental health: Systematic review study. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(6), 1929–1937. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9896-1

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Barner, J. R., Okech, D., & Camp, M. A. (2018). “One size does not fit all:” A proposed ecological model for human trafficking intervention. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1420514

- Betancourt, T. S., McBain, R., Newnham, E. A., & Brennan, R. T. (2014). Context matters: Community characteristics and mental health among war-affected youth in Sierra Leone. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(3), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12131

- Borschmann, R., Oram, S., Kinner, S. A., Dutta, R., Zimmerman, C., & Howard, L. M. (2016). Self-harm among adult victims of human trafficking who accessed secondary mental health services in England. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 68(2), 207–210.https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201500509

- Bravo, K. E. (2019). Contemporary state anti-‘slavery’ efforts: Dishonest and ineffective (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3504027). Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3504027

- Broome, A., & Quirk, J. (2015). The politics of numbers: The normative agendas of global benchmarking. Review of International Studies, 41(5), 813–818. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210515000339

- Brunovskis, A., & Surtees, R. (2007). Leaving the past behind? When victims of trafficking decline assistance. Fafo and Nexus Institute. http://prosentret.no/?wpfb_dl=456

- Chisolm-Straker, M., & Stoklosa, H. (Eds.). (2017). Human trafficking is a public health issue: A paradigm expansion in the United States. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47824-1

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., Kastner, M., & Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013

- Curran, R. L., Naidoo, J. R., & Mchunu, G. (2017). A theory for aftercare of human trafficking survivors for nursing practice in low resource settings. Applied Nursing Research, 35(June), 82–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2017.03.002

- Dell, N. A., Maynard, B. R., Born, K. R., Wagner, E., Atkins, B., & House, W. (2017). Helping survivors of human trafficking: A systematic review of exit and postexit interventions. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 20(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017692553

- Devan, H., Perry, M. A., van Hattem, A., Thurlow, G., Shepherd, S., Muchemwa, C., & Grainger, R. (2019). Do pain management websites foster self-management support for people with persistent pain? A scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling, 102(9), 1590–1601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.009

- Fancourt, D., Bhui, K., Chatterjee, H., Crawford, P., Crossick, G., DeNora, T., & South, J. (2021). Social, cultural and community engagement and mental health: Cross-disciplinary, co-produced research agenda. BJPsych Open, 7(1), e3. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.133

- Fehrenbacher, A. E., Musto, J., Hoefinger, H., Mai, N., Macioti, P. G., Giametta, C., & Bennachie, C. (2020). Transgender people and human trafficking: Intersectional exclusion of transgender migrants and people of color from anti-trafficking protection in the United States. Journal of Human Trafficking, 6(2), 182–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2020.1690116

- Fudge, J. (2017). Modern slavery, unfree labour and the labour market: The social dynamics of legal characterization. Social & Legal Studies, 27(4), 414-434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663917746736

- Fukushima, A. I., Gonzalez-Pons, K., Gezinski, L., & Clark, L. (2020). Multiplicity of stigma: Cultural barriers in anti-trafficking response. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 13(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHRH-07-2019-0056

- Gajic-Veljanoski, O., & Stewart, D. E. (2007). Women trafficked into prostitution: Determinants, human rights and health needs. Transcultural Psychiatry, 44(3), 338–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461507081635

- Gatti, Z. (2013). Las víctimas de la Trata. Política de restitución de derechos. El Programa Nacional de Rescate y Acompañamiento a las Personas Damnificadas por el Delito de Trata. In L. D’Angelo, D. Fernandez, H. Olaeta, J. M. Mena, A. Ghezzi, C. Stevens, & Z. Gatti (Eds.), Trata de personas. Politicas de Estado para su prevencion y sancion. Infojus and Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos. http://www.jus.gob.ar/media/1008426/Trata_de_personas.pdf

- Hemmings, S., Jakobowitz, S., Abas, M., Bick, D., Howard, L. M., Stanley, N., Zimmerman, C., & Oram, S. (2016). Responding to the health needs of survivors of human trafficking: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 320. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1538-8

- Hopper, E. K., & Gonzalez, L. D. (2018). A comparison of psychological symptoms in survivors of sex and labor trafficking. Behavioral Medicine (Washington, D.C.), 44(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2018.1432551

- Hopper, E. K. (2017). Trauma-informed psychological assessment of human trafficking survivors. Women & Therapy, 40(1–2), 12–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2016.1205905

- Hossain, M., Zimmerman, C., Abas, M., Light, M., & Watts, C. (2010). The relationship of trauma to mental disorders among trafficked and sexually exploited girls and women. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2442–2449. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.173229

- Human Trafficking Foundation. (2018). The slavery and trafficking survivor care standard 2018 (K. Roberts, Ed.). https://www.antislaverycommissioner.co.uk/media/1235/slavery-and-trafficking-survivor-care-standards.pdf

- IOM. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/10027

- IOM. (2017). Global trafficking trends in focus. International Organization for Migration.

- Katona, C., Robjant, K., Shapcott, R., & Witkin, R. (2015). Addressing the mental health needs in survivors of modern slavery. A critical review and research Agenda. The Freedom Fund and Helen Bamber Foundation.

- Kiss, L., & Zimmerman, C. (2019). Human trafficking and labor exploitation: Toward identifying, implementing, and evaluating effective responses. PLOS Medicine, 16(1), e1002740. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002740

- Kometiani, M. K., & Farmer, K. W. (2020). Exploring resilience through case studies of art therapy with sex trafficking survivors and their advocates. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 67(February), 101582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2019.101582

- Laurie, N., Richardson, D., Poudel, M., Samuha, S., & Townsend, J. (2015). Co-producing a post-trafficking agenda: Collaborating on transforming citizenship in Nepal. Development in Practice, 25(4), 465–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2015.1029436

- Lazzarino, R. (2014). Between Shame and Lack of Responsibility: The Articulation of Emotions among Female Returnees of Human Trafficking in Northern Vietnam. Antropologia, 1(1), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.14672/ada2014260p

- Lazzarino, R. (2020). PTSD or lack of love? Medicine Anthropology Theory, 7(2), 230–246. https://doi.org/10.17157/mat.7.2.742

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Martinez, O., & Kelle, G. (2013). Sex trafficking of LGBT individuals. The International Law News, 42(4), sex_trafficking_lgbt_individuals. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4204396/

- Mumey, A., Sardana, S., Richardson-Vejlgaard, R., & Akinsulure-Smith, A. M. (2020). Mental health needs of sex trafficking survivors in New York City: Reflections on exploitation, coping, and recovery. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 13(2),185-192. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000603

- Namy, S., Carlson, C., Morgan, K., Nkwanzi, V., & Neese, J. (2021). Healing and resilience after trauma (HaRT) Yoga: Programming with survivors of human trafficking in Uganda. Journal of Social Work Practice, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2021.1934819

- O’Connell Davidson, J. (2013). Troubling freedom: Migration, debt, and modern slavery. Migration Studies, 1(2), 176-195. https://doi.org/10.1093/migration/mns002

- Oram, S., Abas, M., Asher, L., Osrin, D., Kiss, L., Ahmad, A., & Zimmerman, C. (2018). Psychosocial interventions to improve mental health among women and child survivors of modern slavery: A realist review. PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, 5. CRD42018114179 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php? ID=CRD42018114179

- Oram, S., Abas, M., Bick, D., Boyle, A., French, R., Jakobowitz, S., Khondoker, M., Stanley, N., Trevillion, K., Howard, L., & Zimmerman, C., & others. (2016). Human trafficking and health: A survey of male and female survivors in England. American Journal of Public Health, 106(6), 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303095

- Ottisova, L., Hemmings, S., Howard, L. M., Zimmerman, C., & Oram, S. (2016). Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: An updated systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 25(4):317-41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796016000135

- Ottisova, L., Smith, P., & Oram, S. (2018). Psychological consequences of human trafficking: Complex posttraumatic stress disorder in trafficked children. Behavioral Medicine, 44(3), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2018.1432555

- Palmer, V. J., Weavell, W., Callander, R., Piper, D., Richard, L., Maher, L., Boyd, H., Herrman, H., Furler, J., Gunn, J., Iedema, R., & Robert, G. (2018). The participatory Zeitgeist: An explanatory theoretical model of change in an era of coproduction and codesign in healthcare improvement. Medical Humanities, 45(3), 247-257. https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2017-011398

- Patel, V., Belkin, G. S., Chockalingam, A., Cooper, J., Saxena, S., & Unützer, J. (2013). Grand challenges: Integrating mental health services into priority health care platforms. PLoS Medicine, 10(5), e1001448. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001448

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Soares Baldini, C., & Parker, D. (2017). Chapter 11: Scoping review. In E. Aromataris, and Z. Munn (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. JBI. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

- Pocock, N. S., Chan, Z., Loganathan, T., Suphanchaimat, R., Kosiyaporn, H., Allotey, P., Chan, W.-K., Tan, D., & Angkurawaranon, C. (2020). Moving towards culturally competent health systems for migrants? Applying systems thinking in a qualitative study in Malaysia and Thailand. PLOS ONE, 15(4), e0231154. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231154

- Pocock, N. S., Kiss, L., Oram, S., Zimmerman, C., & Goldenberg, S. M. (2016). Labour trafficking among men and boys in the greater mekong subregion: Exploitation, violence, occupational health risks and injuries. PLOS ONE, 11(12), e0168500. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168500

- Powell, C., Heslin, M., Howard, L. M., Katona, C., Zimmerman, C., & Oram, S. (2018). How effective and cost-effective are casework and client support interventions in improving health and social outcomes for victims of modern slavery and human trafficking, asylum seekers and refugees? PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, 5. PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018089206 Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/ prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018089206

- Puschner, B., Repper, J., Mahlke, C., Nixdorf, R., Basangwa, D., Nakku, J., Ryan, G., Baillie, D., Shamba, D., Ramesh, M., Moran, G., Lachmann, M., Kalha, J., Pathare, S., Müller-Stierlin, A., & Slade, M. (2019). Using peer support in developing empowering mental health services (UPSIDES): Background, rationale and methodology. Annals of Global Health, 85(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2435

- Quirk, J. (2011). The anti-slavery project: From the slave trade to human trafficking. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. G. Burgess (Eds.), Analyzing qualitative data (pp. 173–194). Routledge.

- Rose, A. L., Howard, L. M., Zimmerman, C., & Oram, S. (2020). A cross-sectional comparison of the mental health of people trafficked to the UK for domestic servitude, for sexual exploitation and for labor exploitation. Journal of Human Trafficking, 6(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2020.1728495

- Ross, C., Dimitrova, S., Howard, L. M., Dewey, M., Zimmerman, C., & Oram, S. (2015). Human trafficking and health: A cross-sectional survey of NHS professionals’ contact with victims of human trafficking. BMJ Open, 5(8), e008682. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008682

- Shigekane, R. (2007). Rehabilitation and Community Integration of Trafficking Survivors in the United States. Human Rights Quarterly, 29(1), 112–136. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.2007.0011

- Stanley, N., Oram, S., Jakobowitz, S., Westwood, J., Borschmann, R., Zimmerman, C., & Howard, L. M. (2016). The health needs and healthcare experiences of young people trafficked into the UK. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59(September), 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.08.001

- Steiner, J. J., Kynn, J., Stylianou, A. M., & Postmus, J. L. (2018). Providing services to trafficking survivors: Understanding practices across the globe. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 15(2), 151–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/23761407.2017.1423527

- Sucharew, H., & Macaluso, M. (2019). Methods for research evidence synthesis: The scoping review approach. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 14(7), 416–418. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3248

- Surtees, R. (2008). Trafficking of men–a trend less considered: The case of Belarus and Ukraine. IOM International Organization for Migration.

- The UK Government. (2015). Modern slavery act.

- Thompson, C. D., Mahay, A., Stuckler, D., & Steele, S. (2017). Do clinicians receive adequate training to identify trafficked persons? A scoping review of NHS foundation trusts. JRSM Open, 8(9), 205427041772040. https://doi.org/10.1177/2054270417720408

- Twigg, N. M. (2017). Comprehensive care model for sex trafficking survivors. Journal of Nursing Scholarship: An Official Publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing, 49(3), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12285

- U.S. Department of State. (2017). Trafficking in person report 2017.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. (2018). Global report on trafficking in persons.

- United Nations. (2000). Protocol to prevent, suppress and punish trafficking in persons, especially women and children, supplmenting the United Nations convention against transnational organised crime. UNODC.

- United Nations. (2015). Report of the special rapporteur on trafficking in persons, especially women and children.

- UNODC. (2016). Global report on trafficking in persons 2016.

- Walk Free Foundation. (2016). The global slavery index 2016. http://assets.globalslaveryindex.org/downloads/Global+Slavery+Index+2016.pdf

- Walk Free Foundation. (2018). The global slavery index.

- Weitzer, R. (2015). Human trafficking and contemporary slavery. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112506

- Westwood, J., Howard, L. M., Stanley, N., Zimmerman, C., Gerada, C., & Oram, S. (2016). Access to, and experiences of, healthcare services by trafficked people: Findings from a mixed-methods study in England. British Journal of General Practice, 66(652), e794– e801. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X687073

- Williamson, V., Borschmann, R., Zimmerman, C., Howard, L. M., Stanley, N., & Oram, S. (2019). Responding to the health needs of trafficked people: A qualitative study of professionals in England and Scotland. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(1):173-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12851

- Wood, L. C. N. (2020). Child modern slavery, trafficking and health: A practical review of factors contributing to children’s vulnerability and the potential impacts of severe exploitation on health. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 4(1), e000327. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2018-000327

- Wright, N., Jordan, M., & Lazzarino, R. (2021). Interventions to support the mental health of survivors of modern slavery and human trafficking: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(8), 1026–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640211039245

- Zimmerman, C., Hossain, M., Yun, K., Roche, B., Morison, L., & Watts, C. (2006). Stolen smiles: A summary report on the physical and psychological health consequences of women and adolescents trafficked in Europe. The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/php/ghd/docs/stolensmiles.pdf

- Zimmerman, C., & Kiss, L. (2017). Human trafficking and exploitation: A global health concern. PLOS Medicine, 14(11), e1002437. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002437

- Zimmerman, C., Yun, K., Shvab, I., Watts, C., Trappolin, L., Treppete, M., Bimbi, F., & Adams, B. (2003). The health risks and consequences of trafficking in women and adolescents. Findings from a European study. The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.