ABSTRACT

The exploitation of people in forced labor is a significant human rights violation and a threat to community safety. Despite enhanced efforts to identify and prosecute labor trafficking perpetrators in the U.S. relatively few traffickers have been held accountable. Legal advocates and providers increasingly pursue civil litigation, immigration relief, and other roads to meet victims’ needs and achieve justice. Less understood are the specific legal, structural, and cultural barriers that make the road to justice through the criminal legal system difficult for victims of labor trafficking. Utilizing a comparative case study approach, we examine the life course of five labor trafficking cases through crucial decision points in the criminal legal process. Cases were selected to provide a range of legal system pathways. Data for each case includes legal advocate case records, client interview notes, correspondence between stakeholders, court records, and stakeholder interviews. Through comparative analysis techniques, we identify barriers that derail offender accountability and stymie victim support. The findings provide guidance to improve offender accountability and suggest alternative roads to justice centering on the needs of victims. Identifying barriers in implementing anti-trafficking laws promotes more just, peaceful, and inclusive societies in furtherance of UN Sustainability Goal 16.

Introduction

In the United States, forced labor and labor trafficking have been primarily addressed through a criminal justice approach. Though abusive working conditions are often the result of economic structures, cultural norms, immigration restrictions, and discrimination, the U.S. government has primarily defined human trafficking as a crime and security problem (Farrell & Fahy, Citation2009) and has located authority for stopping such abuses with police and prosecutors. Driven mainly by a deterrent approach, law enforcement delivers public messages that traffickers are dangerous and should be punished, often publicizing enforcement actions to identify traffickers. As is so often the case in the U.S., the carceral state is held up as the swift solution to historically complex social problems (Hagan, Citation2012; Beckett & Sasson, Citation2004).

In landmark legislation known as the 2000 Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act (TVPA), the U.S. Congress defined labor trafficking as a collection of exploitative practices that had previously been processed under a handful of other statutes dating back to the 1930s and 40s (Bang, Citation2013). Defining labor trafficking as “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion,” the TVPA was the first law to target sex and labor trafficking directly. Though labor exploitation is not new, the TVPA signaled a novel approach, bringing the tools of criminal law to bear directly on a persistent and complex social and economic problem. States have subsequently adopted their own laws criminalizing human trafficking, most including provisions criminalizing labor trafficking (Farrell et al., Citation2016). Since the passage of the TVPA, criminal justice agencies have received a significant share of the U.S. anti-trafficking funding; however, few labor trafficking perpetrators have been prosecuted or punished (Attorney General’s Trafficking in Persons Report, Citation2022).

Further, victimology scholars have long argued that crime victims do not report victimization because justice system responses commonly do not meet their needs and wishes and may contribute to revictimization. Specifically, fear of perpetrators and police, the length of criminal justice processes, and the low likelihood of perpetrator accountability all undermine victim trust in the justice system as a remedy for the harms of victimization (Hart & Rennison, Citation2003; Wolf et al., Citation2003; Xie et al., Citation2006). Survivors of human trafficking also report concerns about the adequacy of the justice system to deliver something representing “justice” and to meet basic needs (Farrell et al., Citation2019; Love et al., Citation2018). Not surprisingly, labor trafficking victims rarely self-report to the police, even though law enforcement primarily relies on victims to disclose their abuse to uncover cases (Farrell et al., Citation2014). The complexity, length, and uncertainty around receiving support services also dissuade trafficking victims from seeking official help (Okech et al., Citation2012).

As a result, relatively few labor trafficking cases traverse the criminal legal process, and we understand little about how labor trafficking cases move through the justice system. In addition to understanding where and how labor trafficking cases are derailed in the criminal justice process, legal advocates and service providers underscore the need to understand how labor trafficking victims navigate criminal legal processes to meet their needs to prevent future victimization (Owens et al., Citation2014), and to identify and reduce barriers to justice.

The Limits of Prosecution for Offender Accountability & Provision of Victim Services

Existing research has begun to explore the causes of low numbers of human trafficking prosecutions in the U.S. (e.g., Bang, Citation2013; Farrell et al., Citation2019); however, empirical research on labor trafficking remains in its infancy, and few studies have examined the life course of criminal labor trafficking cases (Aronowitz, Citation2019; Cockbain & Brayley-Morris, Citation2018; Zhang, Citation2012). Our inquiry is guided by literature on interpersonal crimes such as sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sex trafficking, as these crimes and official responses to them share critical similarities with labor trafficking. First, the official response to the behaviors underlying these crimes has shifted over time as legislation redefined longstanding and complex social issues as crime problems (Cox et al., Citation2022; Goodmark, Citation2018; Farrell et al., Citation2014). Second, because of how interpersonal crimes have been defined, identification depends to some extent on culturally informed interpretations of context-specific victim and offender behavior (e.g., what behaviors constitute consent or coercion). Third, despite the adoption of laws, incidents of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and human trafficking are severely underreported, and cases that do enter the justice system suffer from high attrition rates (Huhtanen, Citation2022; Fernández‐Fontelo et al., Citation2019; Farrell et al., Citation2014).

Low levels of prosecution for labor trafficking crimes may be partly explained by the substantial uncertainty faced by justice system actors in the early phases of investigation – even before any formal charges are filed. Research into the early stages of investigation of sexual assault, intimate partner violence, and sex trafficking has revealed that both police and prosecutors attempt to reduce uncertainty in the criminal process by evaluating cases with a “downstream orientation” in which they try to forecast how the case will be evaluated by other criminal justice actors such as judges and juries (Spohn et al., Citation2001). In the labor trafficking context, uncertainty is likely exceptionally high because of (1) the relative newness of the TVPA and (2) the profile of labor trafficking offenders, many of whom wield political, economic, and social capital. Justice system norms and processes activated by this uncertainty lead to few labor trafficking prosecutions.

Unfamiliarity with the legal definition and interpretation of the TVPA among law enforcement, lack of robust legal precedent under the TVPA, and the absence of coordinating mechanisms heighten the uncertainty of labor trafficking cases. Though more than two decades have passed since the TVPA became law, the lack of substantial precedent about labor trafficking cases means that prosecutors and law enforcement continue to struggle with several challenges in interpreting and applying human trafficking laws, including a lack of awareness of jurisdiction over human trafficking, uncertainty about the proof required to show a violation of the statute, and whether criminal provisions of the statute apply to specific individuals and entities involved in trafficking (Farrell et al., Citation2019; Farrell et al., Citation2014; Farrell et al., Citation2010; Newton et al., Citation2008). When little clarity or consensus exists among courtroom actors about the requirements to establish a standard under the law, prosecutors may decline to pursue charges (Farrell et al., Citation2016).

Power disparities between victims and offenders in the U.S. also make labor trafficking prosecutions risky. Labor trafficking victims are frequently recruited from marginalized, impoverished populations and lured into trafficking situations by promises of money, stable housing, or lucrative jobs (Barno & Lynch, Citation2021). In the U.S., undocumented and foreign-born workers are overrepresented among labor trafficking victims, meaning that labor trafficking is frequently perpetrated against individuals of marginalized populations with historically negative relationships with justice systems (Farrell et al., Citation2019; Farrell et al., Citation2014; Buckley, Citation2008). In contrast, offenders tend to have access to significant social, economic, and political power. Not only are offenders exceptionally skilled at preying on victim vulnerabilities during the recruitment and exploitation process, but immigration status differences between victims and offenders, as well as affiliation with criminal networks, also increase the power of offenders relative to victims (Barno & Lynch, Citation2021; Owens et al., Citation2014). Using these network connections, labor traffickers can also coerce victim compliance by calling on variously affiliated contacts to credibly threaten victims’ friends or family (Barno & Lynch, Citation2021; Owens et al., Citation2014).

Justice actors use institutionalized case processing strategies (Frohmann, Citation1991) that draw on cultural stereotypes about race, class, and gender to reduce uncertainty in prosecution (Farrell et al., Citation2010; Barrick et al., Citation2014; Farrell et al., Citation2015). As victim willingness to cooperate and victim credibility are two critical factors in deciding whether to move a case forward for prosecution, negative valuation of victim credibility can end a case before charges are even issued (Albonetti, Citation1986; Frohmann, Citation1997). During investigations, law enforcement may exercise discretion in ways that systematically exclude certain types of victims and offenders from being identified (Barno & Lynch, Citation2021), and victims face well-documented institutional barriers to aiding investigations and accessing services, including racial bias, lack of cultural competency, language barriers, and concerns over immigration status (Messing et al., Citation2015). From there, prosecutors make strategic decisions at the initial stages of the criminal legal process to avoid uncertainty and maximize their chances of winning at trial (Barno & Lynch, Citation2021; Cox et al., Citation2022).

Current Study

The present study employs a comparative case study approach to explore how labor trafficking cases progress through the criminal legal system. Because scholarship on factors that may influence the process and outcome of labor trafficking criminal cases is underdeveloped, we employ an exploratory approach, using qualitative data acquired through a partnership with a U.S. victim services organization to develop an initial understanding of this phenomenon. A comparative cross-case approach allows us to identify common themes about the processing of labor trafficking cases through the justice system and barriers to successful prosecution and, ultimately, victim justice. Using data from provider interviews, case records, client interview notes, and official records, we explore (1) the life course of five labor trafficking cases through crucial decision points in the criminal legal process, from identification of victims through case adjudication – focusing mainly on when in the legal process labor trafficking cases get derailed, and (2) the legal, structural, and cultural challenges that help explain why the criminal legal system is insufficient to hold offenders accountable, meet victim needs, and deliver justice.

Data and Methodology

Five labor trafficking cases were purposefully selected to provide a range of legal system pathways, including cases where offenders were convicted, cases where prosecution was declined but civil damages were awarded, and cases that did not progress beyond law enforcement interviews. Data for each case includes legal advocate case records, client interview notes, correspondence between crucial stakeholders, court records, and stakeholder interviews.

Case Information

briefly details the five studied cases. All five cases involved foreign national victims, three of whom worked in agricultural and domestic labor situations. Only one case was prosecuted, which resulted in a federal conviction. Three cases involved civil litigation, and multiple victims received T-Visas or immigration relief.

Table 1. Brief Details on Each Case.

Data Collection and Availability

The sources for this study consisted of 22 interviews, 27 legal documents, and 19 media articles that provided details on labor trafficking situations and investigations.Footnote1 In 14 interviews, four legal advocates provided representation on the five studied cases. We conducted an additional eight interviews with law enforcement, service providers, and advocates who had information or experience with one or more of the studied cases. For each case, we collected and coded information on the case facts from the criminal indictment, sentencing documentation, hearing information, civil litigation documents, and other associated documents that outline the elements of the labor trafficking crimes as identified through Thomson Reuters Westlaw Edge, LexisNexis, and PACER. We also obtained case notes from the legal advocacy agency representing the five studied cases. summarizes the number of interviews, news articles, and legal files collected for each case.

Table 2. Sources of Information for Each Studied Case.

Data Analysis

Documents (e.g., interview transcripts and text-based legal and media documents) were de-identified and imported to NVivo 12 for analysis. An axial coding technique revealed codes developed inductively through open coding. Multiple coders coded interviews, case notes, legal documents, and media articles. Then, coders held coding conferences and used comparison queries to establish agreement on final nodes and identify emergent themes. These themes were then presented and reviewed by the partner organization for external validation prior to creating a standard codebook.

Throughout this coding process, coders created analytic memos to help capture barriers to prosecution. Each barrier identified was also coded according to the criminal justice phase in which it occurred. The team divided the criminal legal process into eleven phases, including 1) investigation, 2) charging, 3) initial hearing/arraignment, 4) discovery, 5) plea bargaining, 6) preliminary hearing, 7) pre-trial motions, 8) trial, 9) post-trial motions, 10) sentencing, and 11) appeal (Offices of the U.S. Attorneys, n.d.). NVivo queries further explored unique codes and code redundancy and overlap to identify common barriers across each phases. This analysis produced a consolidated list of common barriers to indictment. Then, a final coder recoded the original set of barriers to prosecution using the consolidated list. The resulting data were then analyzed using detailed reports, hierarchy charts, matrix queries, and node examination. We coded 335 references to prosecution roadblocks across 14 common barriers. lists the 14 barriers and the number of times each barrier was referenced within each case.

Table 3. Barriers across cases.

Matrix coding queries of the barriers across the cases revealed that the number of references to barriers varied, partly due to the type and number of legal documents associated with the case, and the various phases at which the cases terminated. For example, formal court documents such as indictments and complaints contained limited information on prosecution barriers, while informal legal documents such as T-Visa applications and internal advocate notes contained rich detail on barriers to indictment. Our interviews with legal advocates identified most barriers, indicating the importance of information attained through direct engagement with legal aid service providers.

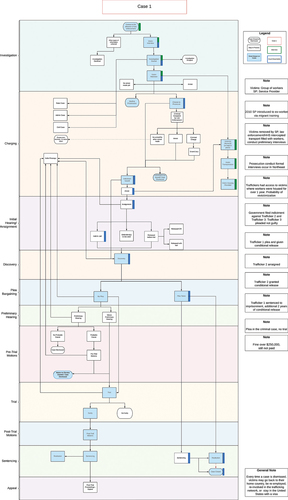

Process Maps

To visually align our results with the phases of the criminal justice process, we developed process maps to indicate the points where each of the studied labor trafficking cases stalled, were abandoned, or ultimately concluded. The process maps show the pathways each case followed. Based on the coding, barriers were identified inductively and inserted in the process maps at specific stages to summarize the findings of the cross-case analysis. Multiple barriers can appear at each stage of the criminal legal process. Barriers can also repeat across a case’s path, and notes along the pathway describe significant path changes. The process map of Case 1 found in below is shaded to indicate the source of a barriers identification (e.g., interview or court document).

Findings

When Did Barriers Occur on the Road to Justice?

The criminal justice process can be seen as a series of phases beginning with the investigation and ending with the release of a convicted offender from correctional supervision. Though formal rules guide many decisions along this path, criminal justice actors command significant discretion in moving cases forward to the next phase in the criminal process (Lafave, Citation1970). Depicting the criminal legal process as a series of consecutive phases, we mapped the life course of each of the five cases in our sample. In three of five cases, a prosecutor filed charges (in one case, the charges were filed and dropped), or an indictment was issued. Of those cases, only one resulted in a conviction, however, that conviction was not for labor trafficking; instead, the offender was convicted and incarcerated for conspiracy to hire illegal aliens. The remaining four cases ended before adjudication during either the investigation or charging phase.

Utilizing a case process mapping technique, we identified barriers occurring in six of the eleven stages of our criminal justice process (investigation, charging, initial hearing/arraignment, pretrial motions, trial, and sentencing). Sixty-six percent (66%) of the coded barriers occurred in the investigation phase, while 27% of the barriers occurred in charging phase. Victim intimidation by trafficker or fear of trafficker was the most common barrier identified in the investigation phase (occurring 77 times across the five studied cases), followed by cultural norms (41 times), lack of cohesion and clarity of roles (30 times), complicated legal structures (30 times), and disruption of powerful people, economic interests (28 times). Choosing the easiest or most certain strategy (14 times) was the most common barrier coded in the charging phase. The remaining 7% of barriers were spread out across multiple phases.

To demonstrate how the 14 identified barriers impact labor trafficking case processing, we walk through the barriers identified in the process mapping for Case 1, using a visualization of the case process map illustrated in (for additional details in the five cases, see Appendix A). Case 1 is an agricultural labor trafficking case involving labor contractors and multiple victims and defendants. Despite the ultimate prosecution of three perpetrators, numerous barriers made the criminal legal process difficult. In the investigation phase, victim intimidation by the trafficker or victim fear of the trafficker was a significant barrier. During the investigation and charging, role conflict, lack of cohesion and clarity, lack of understanding of the cultural norms of victims, and justice system perceptions of victim credibility each weakened the case. Prosecutors ultimately declined to charge under the TVPA and instead charged the lead defendant with illegal harboring, which does not require victim testimony or proof of force, fraud, or coercion. The following sections explore how the barriers, occurring alone or in combination with others, impacted labor trafficking case pathways across all five studied cases.

How Did Barriers Divert the Road to Justice?

We found that numerous barriers endemic to the criminal legal system blocked the road to justice for victims of labor trafficking. We categorize these barriers into legal, institutional, and cultural barriers. Legal barriers are challenges within the legal landscape of labor trafficking and other areas of the law that result in misunderstanding the crime. Institutional barriers refer to inter- and intra-agency policies, goals, and routines that delay or derail investigations resulting from uncoordinated federal, state, and local responses. Cultural barriers include law enforcement’s unfamiliarity with victims’ cultures and reliance on stereotypes about victims in identifying trafficking cases (Farrell et al., Citation2019). In addition to appearing at different stages in each studied case, barriers frequently appeared in combination. Confirming the importance of decisions made early in the criminal legal process on the ultimate outcomes (Barno & Lynch, Citation2021), we argue that the barriers to prosecution render the criminal legal system an inefficient, insufficient, and sometimes hazardous road to justice for victims.

Legal Barriers

During the investigation stage, a lack of clarity among justice officials about the legal standards necessary to bring the case, notably without clear evidence of force, is complicated by deliberate efforts by traffickers to weaponize the complicated legal structures found in labor trafficking situations. Without legally authoritative guidance on applying trafficking statutes, law enforcement can mistake legal ties for complicity. All cases except Case 3 involved legal arrangements that strengthened the legal entanglement between the victim and trafficker.

Trafficking offenders frequently create legal ties by trapping victims in a cycle of debt (Cases 1, 2, 3, and 4) based on fraudulent contracts, by deceiving victims into letting their visas expire (Case 4), by using or fraudulently claiming familial relationships (Case 4 and Case 5), or by manipulating the visa application process of victims and their relatives (Case 5). Though these ties were created during the commission of the crime, their impact could be observed across multiple phases of case processing. For example, in Case 4, the trafficker forced a victim to sign purported “immigration paperwork” before arriving in the U.S. The victim later learned that the document was a contract stating essentially that if he ever worked for any other employer while in the U.S., he would owed the trafficker $8,000. As seen in Case 4, legal ties created by the trafficker prolonged victim vulnerability by causing victims to live with the trafficker even as the case transitioned from investigation to charging.

In Case 5, legal and documentary ties that enabled exploitation also caused law enforcement to misinterpret the context in which the alleged harm occurred and to misidentify the behavior of both trafficker and victim. Ultimately, because the trafficker and victim were legally married, law enforcement fell back on patterned ways of interpreting a domestic incident, drawing on stereotypes and assumptions often cited in the domestic violence context. In discussing this case, a legal advocate recounted the difficulties the victim had in leaving the trafficking situation and separating herself from her trafficker:

The way that our culture, our society, views marriage skewed the lens [with which] law enforcement looked at this case … [police] would say … “Well, she left. She went to [home country]. She came back. She did this twice.” So, it was like very much their whole … [idea] that they’re not chained to the wall … Why would she come back if it was that bad? They just don’t understand the psychology of it. (Case 5, Interview 3)

Legal ties between victims and traffickers continued to complicate the victim’s efforts to seek justice across multiple legal avenues in Case 5 because the trafficker remained the legal guardian of the victim’s relatives. Dealing with ongoing legal issues retraumatized the victim and reduced the victim’s ability to contribute effectively to the investigation. Labor traffickers, who often enjoy a greater understanding of the American legal system than victims, can strategically create or weaponize complicated legal structures within immigration law, family law, contract law, and other legal areas, making it more challenging to distinguish voluntary participation in crime from coercion in the early stages of a case.

Victim intimidation by trafficker or victim fear of trafficker refers to the limits of real protection afforded to labor trafficking victims through the criminal justice system. In our sample, traditional justice responses were inadequate to keep victims safe, as law enforcement only became involved after victims reported abuse and could not discern whether isolated behaviors were part of broader patterns of exploitation. In Case 4, though a victim successfully contacted the police for help, the reactionary nature of the police response failed to discover the exploitative context in which the offending behavior occurred. As recounted by the victim:

Even though I could not speak English much at all, I did my best to explain to [the police] that [the trafficker] was trying to keep me at her house and not let me go home[] and that she had my passport and would not give it back. I thank God because somehow the officer understood and believed me and called [the trafficker] and told her to return my passport. A little while later, [the trafficker’s] daughter brought my passport to the police station … I did not understand labor trafficking; I did not know what it was, that it could happen to me, or how to report it. (Case 4, T-Visa Application)

Here, the local officer identified one strategy of control used by the trafficker (withholding the passport); however, they did not follow up to identify the trafficking situation.

When arrests did result from the criminal investigation, the risk of victimization continued for many victims in our studied cases. In Cases 1, 2, and 4, victims remained at or near the exploitation site after investigations began due to fear of retaliation by traffickers or their associates against victims or family members in the U.S. or overseas. In Case 3, failure to follow through with a criminal prosecution meant that several perpetrators were not held accountable even though civil settlements resulted; arguably, the most culpable offender exited the case early, avoided hostile public relations by early settlement, and continued conducting business after the case ended. Moreover, failure to follow through on prosecution after victims have agreed to participate in the investigation – often at serious risk of harm to themselves and their families – causes distrust and frustration with law enforcement, heightening victim vulnerability to re-trafficking. Describing the impact of the failure to prosecute a labor trafficking suspect, one legal advocate highlighted the importance of offender accountability to their clients:

[W]e always manage expectations … [We tell clients that there is a] very small chance that [prosecutors] will take this case … [but clients will] say a lot of times [that], “We want there to be some sort of accountability.” It’s not like I want money, it’s that I want them to go to jail or I want them to stop doing this. So, when we give them this like broad picture of like … all the remedies under these different avenues. A lot of them are interested in criminal prosecution, more so than anything else, more so than money … And I think that they were really disappointed because I think they internalized that to mean that nobody cared. (Case 4, Interview 2)

Victims in our studied cases did not immediately understand the harms that had occurred to them as labor trafficking. Once they understood the definition of trafficking and connected their experiences to the crime, it was hard to accept that offenders would not be held accountable.

Institutional Barriers

We identified numerous institutional barriers, indicating the challenges victims must navigate in obtaining relief through official channels. Barriers that fell into the institutional thematic category included role conflict, lack of cohesion, lack of clarity, lack of trained law enforcement, lack of trained prosecutors, and disruption of influential people, interests, or economy. As seen in the Case 1 process map, institutional barriers include challenges caused by the lack of coordinating mechanisms among the processes, agencies, and entities available to identify and sanction offenders and aid victims of labor trafficking. In part, the number of different actors and agencies potentially involved in a labor trafficking investigation results from numerous legislative efforts to respond to exploitation in the U.S., and victims of labor trafficking can theoretically pursue both state and federal administrative, civil, and criminal avenues.

When victims connected with the legal service organization, client advocates worked to meet victim needs and explain the variety of legal avenues for justice. Our data supports the need for a variety of remedies, as victims reported multiple needs and goals following exit from the immediate trafficking situation, including safe housing, protection for victims and their families in the U.S. and in their home countries, trauma-informed medical and psychological services, legal representation, and financial support. Though multiple avenues for relief are appropriate, institutional factors frequently impede their practical use. Victims initially sought help from local law enforcement, but we found that mechanisms for accountability were hampered by the social, economic, and political power of offenders, discussed more fully in the cultural barriers section below. When victims accessed federal processes with the aid of legal advocates, a lack of official coordinating mechanisms threatened to derail cases early in the justice process because of the institutional separation between administrative, civil, and criminal investigations.

When victims turned to federal law enforcement for justice, role conflict, lack of cohesion, and lack of clarity combined during the investigation phase to delay the justice process and discourage victim participation, heightening victim vulnerability to further harm in the immediate aftermath of escape (Owens et al., Citation2014). Namely, victims were called on to persevere in assisting law enforcement despite needing to fight competing interpretations of the exploitative situation across multiple agencies and to navigate through the inadequate training and insufficient skillsets among agency personnel (including lack of training on trauma-informed interviewing techniques and inadequate translation services).

Failure to coordinate among agencies allowed siloed and conflicting interpretations to develop and resulted in confusing and contradictory case outcomes. In our data, this looked like law enforcement treating victims as suspects unworthy of respect or assistance, despite the presence of evidence indicating victimization experiences. Recalling an unexpected interview of his clients by ICE (U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement), one legal advocate recounted that:

… it felt like an interrogation. The agents were disrespectful and humiliating toward him. At one point, for example, when they looked at [victim’s] passport, an agent laughed and made some crude comments in English. One of the other agents said that he thought the victim understood some English, so he should stop. The victim told them that he wasn’t going to talk with them further because he felt they were “muy groseros” (very rude) with him. The victim also told them that he couldn’t understand the Spanish translation very well and his English wasn’t very good, so he didn’t want to say something that was inaccurate because of the lack of understanding between them or lack of clarity in the questions. The victim was feeling really upset about the whole situation. He and another victim talked about just closing up the whole thing; it’s taking too long; they have their families to support. (Case 1, Factual Narrative)

Poor treatment by law enforcement not only distracts from the investigation into exploitative labor conditions but actively hinders prosecution by alienating victims who would otherwise be willing to testify and prolonging (and potentially worsening) victims’ financial straits.

Specifically, inconsistency and conflict among agency standards, routines, and goals led to differing interpretations and strategies for responding to a single case. The problem is particularly acute around the granting of continued presence to victims, as agencies have differing standards for its provision. In Case 2, one legal advocate stated:

There was a game of hot potato that happened with the continued presence where I have this theory that most anyone with like Department of State, FBI, federal law enforcement or investigators, they’re either scared of it, or I think there’s like an unwritten, and all this is speculation, or there’s like an unwritten we’re not gonna do this, we’re just gonna dangle the carrot, because it gets us what we need. And then after we get what we need, it’s kind of their problem. So, we would, we were asking for [continued presence] … It was promised. And then it was like, yeah, we don’t … really do that. This other office does it. And so that ended up being probably a month and a half of me calling them on a regular basis and just being the biggest pain in the *** as possible…If it’s not your office, what office does it? Who does it? What’s the number? … I was super frustrated. (Case 2, Interview 1)

When anti-trafficking teams do not have formal legal coordinating mechanisms and legal advocates are placed in a mediating roles, the advocates are forced to rely on personal contacts, as well as informal and, at times, inconsistent processes for information sharing and investigation.

The result is that legal advocates and their clients – victims of labor trafficking who often continue to suffer from financial and legal hardship, abuse, and trauma as agency investigations are ongoing – must perform the additional work of navigating competing interpretations of the exploitative situation with and among different agencies. This dynamic lengthens investigations, prevents information sharing, and delays effective intervention into the trafficking scheme, prolonging victimization experiences and increasing risk of retaliation by traffickers. Over the course of engaging with first state and then federal criminal justice processes, victims became cynical, frustrated, or otherwise unconvinced that this path could assist with their goals.

Lack of capacity to build legal cases also delayed accountability for offenders and the provision of services to victims. Specifically, the lack of sufficient translation services was explicitly mentioned in two cases as an impediment to investigatory and legal processes (Case 1 and Case 5). This capacity gap is more than a matter of convenience: the inability to explain the details of an exploitation experience can exacerbate cultural stereotypes held by law enforcement that led to the miscategorization of crime and misidentification of victims and offenders. When the police fail to identify factors that would promote prosecution (e.g., presence of a minor, multiple victims, use of weapons), legal advocates use alternative strategies to make the case attractive to prosecutors, who are beholden to strong economic interests in the community. Here, legal advocates described political influences on the exercise of prosecutorial discretion to bring charges, observed in three out of five cases.

I also explained to [the victim] that … I’m sorry that this is the way our system works here, that it sounds like I’m, you know, pitching something to them, but I really am because there’s so many different cases you have to try and find creative ways to get them interested in your case … With some of these prosecutors that they’re like, boom, like what’s the story here? What would be the headline, like, do I want to be involved in this case? … You can feel that vibe in the room. So I wasn’t I wasn’t explaining it necessarily like that to her, but I was saying … [we have to] somehow present this case to them in away that’s going to make them want to punish [the trafficker] … At the same time, it’s 100% their discretion to take the case and they could just say no. (Case 5, Interview 2)

Disruption of influential people, interests, or economy refers to hesitance on the part of justice officials to intervene when individuals or entities suspected of labor trafficking have powerful economic, political, or social connections. These connections become barriers to prosecution in the labor trafficking context as criminal justice actors weigh the fear of adverse political/career/legitimacy outcomes in the decision to investigate and/or charge. We found that initial interactions with local law enforcement were ineffective in all cases, either because of traffickers’ power and influence, including existing relationships with law enforcement, or law enforcement’s failure to understand the context in which the behavior occurred. In Case 1, the power of the growers who benefitted from the trafficking halted investigations before they began; in fact, instances in which local police were called to the property became staged displays of the trafficker’s power to discourage worker dissent or escape. The power of growers was exacerbated by a law enforcement culture that values legitimacy and risk avoidance. In Case 5, the victim turned to the media for help because her trafficker’s connection to and influence over local police impeded the investigation (Case 5, News).

At the charging phase, prosecutors consider the political fallout of charging particular offenders in ways that tend to allow politically and economically powerful offenders to escape prosecution; indeed, the same laws that contribute to the legal uncertainty around the charging of labor trafficking may protect these economic interests (e.g., corporate forms, joint employment law). For example, the criminal investigation in Case 2 came to a grinding halt when U.S. criminal justice agencies clashed with the politically sensitive diplomatic status of one of the traffickers. In Cases 1 and 3, companies that likely knew about and benefitted from trafficking were able to escape criminal and civil sanctions:

… you know that there were a lot of powerful people in that case, a lot of powerful people. They’re dealing with a powerful industry, which is the same as Case 3 … The governor would have been implicated in it, the guest worker program would have been implicated in it, there’s a lot of implications … If you decide to someone charge with trafficking … , now you have to inevitably bring other laws.

But even outside of explicitly political influences on the decision whether to charge, the nature of labor trafficking (in which perpetrators tend to hold substantially more political, economic, and social status than victims) and the nature of prosecution (which is affected by these political, economic, and social factors) tends to result in offenders escaping accountability.

Cultural Barriers

Barriers to prosecution in the cultural category included choosing the most straightforward or most certain strategy, cultural norms and perceptions of victim credibility, and myths or biases about what labor trafficking looks like. Cultural barriers are those circumstances in which culturally informed beliefs among criminal justice actors interact with unfamiliarity with the culture of populations vulnerable to labor trafficking to activate institutional responses to uncertainty. The effects of this confluence of barriers are especially acute when assessing victim and witness credibility. Because credible witness testimony is believed to be critical to obtaining a conviction at trial, difficulties recognizing victimization experiences have a negative impact on the probability of a case moving forward. Our study suggests that cultural norms or beliefs found among both criminal justice actors and victims coincide with reducing the likelihood that labor trafficking investigations move forward to trial for several reasons.

Because the definition of labor trafficking requires force, fraud, or coercion, victim testimony is often necessary to provide clear evidence of these elements. Absent other evidence, prosecutors depend on victim testimony to prove trafficking and encourage survivor participation sometimes as a mechanism to obtain the resources and immigration permissions to meet basic needs (e.g., work authorization, health care, housing) (Roby et al., Citation2008).

The tendency to choose the most straightforward or most certain strategy in pursuing a criminal case shaped criminal justice response to labor trafficking situations from the outset, as criminal justice actors engaged in early, downstream-oriented analyses that aimed to predict the probability of success at trial. First, as the need for credible witness testimony is especially high when there is no clear evidence of force, the belief that a victim will make a poor witness at trial reduces the likelihood that the criminal justice process will progress. As one legal advocate recounted, even though the investigation of Case 2 had established at least some elements of trafficking:

[T]here was no physical violence, there really was only sort of psychological abuse … [and] emotional abuse[, but] it wasn’t like bruising on your body … [And] because of[the victims’] forgiving nature, it was sort of like, ‘We’re not going to win this case’.(Case 2, Interview 2)

Then, when prosecuting actors believe that victim testimony is unavailable, untrustworthy, or unbelievable, charges like alien harboring or smuggling are more likely to issue during the investigation phase because these charges are less onerous to prove and less reliant on victim testimony. Therefore, charging offenses other than labor trafficking is a strategy to reduce the uncertainty associated with proving a trafficking offense to an imagined American jury. Moreover, as observed in other contexts, this hypothetical jury shares a common cultural background that views certain victim behaviors and circumstances as more or less trustworthy or deserving of protection and relief. It is by evaluating victim behavior against this cultural background that prejudicial beliefs along race, class, and gender lines can systematically derail cases involving the most vulnerable victims from the justice process.

Cultural norms and perceptions of victim credibility frequently coincided with both legal and institutional barriers, including victim intimidation by traffickers and fear of traffickers, lack of trained law enforcement and myths and biases about what labor trafficking looks like. As criminal justice actors tend to hold more positive evaluations of victim credibility when recall of alleged sexual assaults is consistent over time (Frohmann, Citation1991) and to expect that trafficking victims respond in culturally recognizable ways to victimization (Musto, Citation2016), legal advocates cited common symptoms of trauma, cultural differences in trauma response, and lack of training among criminal justice actors as key contributors to the high attrition rate of cases in our sample, particularly at the investigation phase. A legal advocate explained that the victim in Case 5 would apologize and correct herself or correct facts during investigation interviews. While police interpreted these statements as evidence of her “changing her story,” the legal advocate tried to educate them about the fact that such patterns are standard among trauma survivors. In Case 4, law enforcement was reluctant to refer the case for prosecution because they perceived the victim’s reaction to the perpetrator as inappropriate. As the legal advocate explained:

[The victim is] just a very like happy go lucky happy human, not much can [] bring him down … [W]hen they were interviewing him and especially when the prosecutor was interviewing him … I think they got a sense of this, and it wasn’t helpful for him, unfortunately … We would prep him before these interviews, especially when [he needed to discuss how] she would do horrendous things to him. He would laugh, he would smile … he would kind of look up and then, hit his leg like, “Oh, she’s so nuts.” And I would explain to him that I think that there’s going to be some cultural disconnect … with the way that he is [] sharing his experience with [the trafficker] because for whatever reason in America the survivor or the victim is portrayed as, like, very traumatized, sad, crying … will never recover. And he did not present in that way, and he explained to me that in his culture, he’s like, “Well, maybe it will be helpful for the … agents to know that in my culture … when we would have something horrible happen … we would celebrate. We have a party [when] someone dies. There’s a horrible accident, someone loses a baby, and we have a party, and that’s to stay in the moment and it’s to lift our spirits.”

Cultural factors thus also funnel cases involving immigrant populations out of the justice system.

The barrier myths or biases about what labor trafficking looks like refer to the justice actor’s expectation that victims adhere to a particular behavior profile reminiscent of the iconic victim of human trafficking. Among the prosecutorial strategies documented by Frohmann (Citation1991) in her study of sexual assault case rejections are to question post-incident victim behaviors; decisions to continue the relationship with the alleged offender after the fact is considered particularly suspect, despite the prevalence of revictimization experiences. In our sample, explicit evidence of re-trafficking experiences was present in Cases 3 and 4, and victims’ return to the same or similarly exploitative work environments led law enforcement and other actors to negatively evaluate their credibility as witnesses and the likelihood of success at trial. But even without evidence of re-trafficking, under a law enforcement culture in which credible victims are perfectly innocent and always willing to assist in criminal investigations, victims’ survival strategies are construed as evidence of complicity in the crime – evidence that the victims were “in on it.” Delays in reporting due to fear of retaliation by the trafficker (Case 4), inconsistent factual statements commonly related to traumatic victimization experiences (Cases 2, 3, and 4), and decisions to trust the trafficker in ways that law enforcement struggles to understand (all cases) also resulted in negative evaluations of victim credibility.

In addition to drawing on images of the “iconic victim” as young, white, innocent, and eager to help the police, our data suggest that law enforcement extends myths or biases about what labor trafficking looks like to draw on “iconic offender” frames in deciding how to intervene in cases. Criminal justice actors tend to believe that labor trafficking offenders share demographic characteristics and are more willing to move forward with prosecutions when offenders are male, nonwhite, and foreign (non-American). In explaining why Case 1 might have been charged as an illegal harboring case, rather than as trafficking when there had been evidence of force used to control victims, one legal advocate reflected that:

Brown people are criminals who are presenting false documents and it’s hurting some poor person with identity theft … you know the narrative[] … there’s some racism. You know it’s like it’s cool when the trafficker is Brown, but once you start really, really realizing that [the Employer] isn’t and then no, no, that changes the narrative … It changes the statistics, you know, it changes everything … [If] the trafficker is Mexican, then it’s all good. I mean, it’s still they’re “bad hombres” over there. (Case 1, Interview 2)

As the advocate observes, a corollary to the tendency to identify Black and Brown suspects more readily as violators of labor trafficking or other criminal laws is that other, potentially more culpable defendants (e.g., growers and corporate actors) continue to operate unfettered by law enforcement intervention. This profile includes assumptions that labor traffickers are male, an assumption that was complicated in Case 4 when the trafficker was a woman: FBI communications indicate the prosecutors were not interested in charging an older woman without clear evidence of physical abuse. That traffickers are thought to reflect a particular profile that is male, nonwhite, and foreign was echoed across all study sources and multiple cases, indicating that the assumption is widespread among criminal justice actors and the public.

Together, the identified barriers diverted the path of labor trafficking cases across various stages of the criminal process. The road to justice for victims was fraught with challenges, and ultimately, none of the five cases studied received the idealized version of justice where offenders are held accountable, and victims are protected from future harm.

Discussion

Prosecution has been declared a cornerstone of anti-trafficking efforts domestically and abroad (Brunovskis & Skilbrei, Citation2016). Our data suggests that barriers to prosecution tend to concentrate at the early stages of the criminal justice process, explaining why so few labor trafficking cases have gone forward to charging and conviction. In all, our findings concerning when barriers occur on the road to justice suggest that reforms concentrated on improving law enforcement training in activities concentrated in the investigation and charging stage could make the road to justice more accessible for victims. Our findings indicate that the creation and implementation of formal coordinating mechanisms, such as task forces and interagency agreements, are needed to organize and coordinate effective trafficking interventions effectively. Additionally, criminal justice agencies should work to remedy identified resource capacity gaps by providing training in common labor trafficking-specific coercion and control strategies, trauma and victimization experiences, and additional translation services.

However, such reforms would do little to counter the insufficiency of the traditional criminal justice processes to protect victims and others from further abuses. Our analysis supports previous findings indicating that prosecutors’ political goals and desire for career success shape their perception of and strategy toward interpersonal crimes (Albonetti, Citation1986), and that local, as well as international, political factors can impede the criminal justice process in ways that systematically fail to identify and sanction particular kinds of offenders. Ultimately, the labor trafficking context may provide another example of the function of the justice system as a political legitimacy tactic, where elites wield criminal law for political advantage and governance strategy – but do little to meaningfully respond to the crime problem (Hagan, Citation2012). In our sample, criminal processes primarily served to alienate and disappoint victims, many of whom were blocked from accessing theoretically available relief. Given the numerous barriers reported in this study, we argue that labor trafficking victims may be better served along avenues outside the criminal justice system. So, are there alternative roads?

Civil avenues for relief may provide a viable option, as victims enjoy greater autonomy through this process than criminal prosecution. However, there are several limitations to this road. First, victims typically must disclose their identities to pursue civil remedies, and without adequate law enforcement aid, fear of traffickers may continue to chill litigation. Second, litigation against repeat players such as corporations may require resources beyond the capacity of public legal services organizations (Dryhurst, Citation2013). Third, the award of monetary damages does not necessarily mean a cessation of exploitation or financial relief; moreover, awards must be collected, and, as our data reflect, victims do not always receive money awarded in judgments.

Broader regulatory and policy change is another potentially viable avenue. It is critical to examine the life course of labor trafficking cases because they represent a unique domain where business structures and networks are central to facilitating abuses, obscuring harm, and shielding traffickers from accountability (Childress et al., Citation2023). De Vries (Citation2019) highlights the numerous connections between illicit trafficking networks and legitimate industries, even as the crime framing of these problems ignores the role of the capitalist economy in producing harm. Exploitative behaviors in the labor sector are closely linked with common market factors and business processes, intimately connected to the broader regulatory environment that isolated law enforcement intervention is unequipped to remedy (Barrick et al., Citation2014). Recognizing the connection between exploitative business practices and labor trafficking victimizations means also acknowledging the role of broader economic, labor and immigration policy in contributing to harm. Our findings indicate that, on many levels, changing the nature of how we protect, and respect U.S. workers is critical to reducing the harms of labor trafficking.

Future Study, Limitations, and Research Learnings

The opportunity to interview victim service providers yielded surprising insights into how cases might travel through the criminal justice process and, more importantly, how they will be impeded from moving forward. The identified barriers and their respective process maps were presented to and reviewed by the partner organization for feedback (e.g., node naming conventions, clarifications on pathways, and discussion of any missing details) prior to finalization. Engagement with the partner organization through interviews and data collection resulted in significance findings about the limitations of criminal justice system pathways in achieving justice for victims or meeting their needs. Though a potential limitation of our analysis is that barriers were primarily identified through provider interviews, future research should strive to include partner organizations and survivors’ voices, as these provided rich sources of data. Additionally, because labor trafficking victims also pursue civil avenues for relief, future research should examine barriers to administering civil remedies.

A limitation to be overcome by future work is that these five cases might not be representative of all labor trafficking victims, as our sample is comprised of those involving victims who sought some remedy. However, our data is valuable because several victims articulated a desire to work with law enforcement but ran into barriers along that specific path. Though labor trafficking literature emphasizes the difficulty in detecting labor trafficking because of the disinclination of victims to come forward, our data suggest that the road to criminal justice was not a road traversable for victims of labor trafficking. If a road is meant to deliver people to their destination, we find that the criminal legal process is only half-built to facilitate such movement. As a result, it may be more productive to consider alternative routes to justice outside the criminal justice system.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the 2021 Northeastern University TIER 1: Seed Grant/Proof of Concept Program. We are grateful for the assistance of Alexis Yohros, Jesenia Robles, and Kate Rich, who assisted in gathering data, coding, and visualizing the labor trafficking disruptions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Media publications were identified by performing multiple searches on Google’s search engine using keywords associated with the case (including case name, as well as the names of businesses, worksites, and individuals identified as victims, defendants, or other prominent actors). This process was repeated at several points throughout the study period to ensure that the most recent reporting on the case was reflected in the collected data.

References

- Albonetti, C. A. (1986). Criminality, prosecutorial screening, and uncertainty: Toward a theory of discretionary decision making in felony case processing. Criminology, 24(4), 623–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1986.tb01505.x

- Aronowitz, A. A. (2019). Regulating business involvement in labor exploitation and human trafficking. Journal of Labor and Society, 22(1), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1111/wusa.12372

- Attorney general’s trafficking in persons report. (2022). https://www.justice.gov/Human trafficking/attorney-generals-trafficking-persons-report

- Bang, N. J. (2013). Unmasking the charade of the global supply contract: A novel theory of corporate liability in human trafficking and forced labor cases. Houston Journal of International Law, 35(2), 255–322. https://justis.vlex.com/#vid/635605313

- Barno, M., & Lynch, M. (2021). Selecting charges. In R. F. Wright, K. L. Levine, & R. M. Gold (Eds.), The oxford handbook of prosecutors and prosecution (pp. 35–58). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190905422.001.0001

- Barrick, K., Lattimore, P. K., Pitts, W. J., & Zhang, S. X. (2014). When farmworkers and advocates see trafficking but law enforcement does not: Challenges in identifying labor trafficking in North Carolina. Crime, Law and Social Change, 61(2), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9509-z

- Beckett, K., & Sasson, T. (2004). The politics of injustice: Crime and punishment in America. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452229614

- Brunovskis, A., & Skilbrei, M.-L. (2016). Two birds with one stone? Implications of conditional assistance in victim protection and prosecution of traffickers. Anti-Trafficking Review, 6, 13. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121662

- Buckley, C. (2008). Forced Labor in the United States: A contemporary problem in need of a contemporary solution. Human Rights and Human Welfare, 8(1), 116–117.

- Childress, C., Farrell, A., Bhimani, S., & Maass, K. L. (2023). Disrupting labor trafficking in the agricultural sector: Looking at opportunities beyond law enforcement interventions. Victims & Offenders, 18(3), 473–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2133036

- Cockbain, E., & Brayley-Morris, H. (2018). Human trafficking and labour exploitation in the casual construction industry. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 12(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax032

- Cox, J., Daquin, J. C., & Neal, T. M. S. (2022). Discretionary prosecutorial decision-making: gender, sexual orientation, and bias in intimate partner violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 49(11), 1699–1719. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548221106498

- De Vries, I. (2019). Connected to crime: An exploration of the nesting of labour trafficking and exploitation in legitimate markets. The British Journal of Criminology, 59(1), 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azy019

- Dryhurst, K. (2013). Liability up the supply chain: Corporate accountability for labor trafficking. New York University Journal of International Law & Politics, 45(2), 641–676.

- Farrell, A., Dank, M., Vries, I., Kafafian, M., Hughes, A., & Lockwood, S. (2019). Failing victims? Challenges of the police response to human trafficking. Criminology & Public Policy, 18(3), 649–673. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12456

- Farrell, A., DeLateur, M. J., Owens, C., & Fahy, S. (2016). The prosecution of state-level human trafficking cases in the United States. Anti-Trafficking Review, 6(6), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.14197/atr.20121664

- Farrell, A., & Fahy, S. (2009). The problem of human trafficking in the U.S.: Public frames and policy responses. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(6), 617–626.

- Farrell, A., McDevitt, J., Pfeffer, R., Fahy, S., Owens, C., Dank, M., & Adams, W. (2012). Identifying challenges to improve the investigation and prosecution of state and local human trafficking cases.

- Farrell, A., Owens, C., & McDevitt, J. (2014). New laws but few cases: Understanding the challenges to the investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases. Crime, Law and Social Change, 61(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-013-9442-1

- Farrell, A., & Pfeffer, R. (2014). Policing human trafficking: Cultural blinders and organizational barriers. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 653(1), 46–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716213515835

- Farrell, A., Pfeffer, R., & Bright, K. (2015). Police perceptions of human trafficking. Journal of Crime & Justice, 38(3), 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/0735648X.2014.995412

- Fernández‐Fontelo, A., Cabaña, A., Joe, H., Puig, P., & Moriña, D. (2019). Untangling serially dependent underreported count data for gender‐based violence. Statistics in Medicine, 38(22), 4404–4422. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8306

- Frohmann, L. (1991). Discrediting victims’ allegations of sexual assault: Prosecutorial accounts of case rejections. Social Problems (Berkeley, Calif.), 38(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.1991.38.2.03a00070

- Goodmark, L. (2018). Decriminalizing domestic violence: A balanced policy approach to intimate partner violence (1st ed., pp. 1—11). University of California Press.

- Hagan, J. (2012). Who are the criminals? : The politics of crime policy from the age of Roosevelt to the age of Reagan. Princeton University Press.

- Hart, T. C., & Rennison, C. M. (2003). Reporting crime to the police, 1992-2000. U.S. Dept. of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

- Huhtanen, H. (2022). Gender bias in sexual assault response and investigation (part 1). End violence against women international. https://evawintl.org/wp-content/uploads/TB-Gender-Bias-1-4-Combined-1.pdf

- Lafave, W. (1970). The prosecutor’s discretion in the United States. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 18(3), 532–548. https://doi.org/10.2307/839344

- Love, H., Hussemann, J., Yu, L., McCoy, E. & Owens, C. (2018). Comparing Narratives of Justice. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/97346/comparing_narratives_of_justice_0.pdf

- Messing, J. T., Ward-Lasher, A., Thaller, J., & Bagwell-Gray, M. E. (2015). The state of intimate partner violence intervention: Progress and continuing challenges. Social Work, 60(4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swv027

- Musto, J. (2016). Control and protect: Collaboration, carceral protection, and domestic sex trafficking in the United States. University of California Press.

- Newton, P. J., Mulcahy, T. M. & Martin, S. E. (2008). Finding victims of human trafficking. https://doi.org/10.1037/e540892008-001

- Offices of the United States Attorneys. (2016, January 15). Steps in the federal criminal process. Justice.gov. https://www.justice.gov/usao/justice-101/steps-federal-criminal-process

- Okech, D., Morreau, W., & Benson, K. (2012). Human trafficking: Improving victim identification and service provision. International Social Work, 55(4), 488–503.

- Owens, C., Dank, M., Breaux, J., Bañuelos, I., Farrell, A., Pfeffer, R., Bright, K., Heitsmith, R., & McDevitt, J. (2014). Understanding the organization, operation, and victimization process of labor trafficking in the United States. Urban Institute.

- Roby, J. L., Turley, J., & Cloward, J. G. (2008). U.S. Response to human trafficking: Is it enough? Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 6(4), 508–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/15362940802480241

- Spohn, C., Beichner, D., & Davis-Frenzel, E. (2001). Prosecutorial justifications for sexual assault case rejection: Guarding the “gateway to justice. Social Problems, 48(2), 206–235. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2001.48.2.206

- Wolf, M. E., Ly, U., Hobart, M. A., & Kernic, M. A. (2003). Barriers to seeking police help for intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 18(2), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022893231951

- Xie, M., Pogarsky, G., Lynch, J. P., & McDowall, D. (2006). Prior police contact and subsequent victim reporting: Results from the NCVS. Justice Quarterly, 23(4), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820600985339

- Zhang, S. X. (2012). Measuring labor trafficking: A research note. Crime, Law and Social Change, 58(4), 469–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-012-9393-y

Appendix A

Case 1 involved traffickers who recruited primarily undocumented Mexican workers, including minors, to perform agricultural work on various farms. Traffickers maintained control over victims by a combination of surveillance and threats. Our legal organization partner learned of potential trafficking from an ex-worker who attended a trafficking training session. After involving law enforcement at the rescue victim’s request, a lengthy criminal investigation ensued, and additional potential victims were identified. Victims received varied services: some victims were located in the housing for the entirety of the investigation, while others returned to areas where traffickers had access to victims, and several were re-trafficked by the same network. Some victims received continued presence and T-visas. A federal indictment was issued against two of the traffickers; ultimately, one pleaded guilty to illegal harboring and was sentenced to imprisonment. The legal advocacy organization also won a civil judgment on behalf of victims; however, to date, no money has been collected.

In Case 2, traffickers fraudulently procured visas for approximately 15 to 20 predominately East Asian and North African victims over the course of multiple years. Though the visa applications stated that victims would be employed as administrative or technical staff, victims were employed as the traffickers’ personal drivers, domestic helpers, farmhands, and assistants at their residences and farms. The case came to the attention of the legal advocacy organization when a victim phoned their office from a supermarket. After involving law enforcement at the victim’s request, the FBI collected information using search warrants and interviews. The prosecutor eventually issued a criminal indictment charging three individuals with visa fraud. One defendant was arrested, while others remained at large. Victims received housing through a personal connection of a lawyer with the legal advocacy organization, and one victim received law enforcement parole. The legal organization reported significant and unusual difficulties obtaining continued presence or deferred action relative to their experience in similar situations.

In Case 3, traffickers used recruiters in several areas to lure Mexican victims to the United States and fraudulently obtain H-2B visas. Victims were transported via railroad and were responsible for unloading, setting up, and breaking down large-scale entertainment events; they also worked during railroad transit as concession workers. After removal from the immediate trafficking situation, some victims received T-visas; however, most victims in need of work returned to their home countries. The legal advocacy organization filed a civil class action based on the TVPA, FLSA, RICO, ATCA, and other state law claims. Shortly after, the prosecutor filed a criminal complaint. A defendant was arrested, but the case was quickly dismissed on a motion from the prosecutor, apparently after reaching a deal with the defendant that if he paid workers’ back wages, he would be released. The legal advocacy organization also settled a civil suit with the company and one of the traffickers.

Case 4 involved two periods of exploitation in which victims were re-trafficked by the same entertainment company. Initially, multiple workers were recruited for an entertainment company and traveled from their home country in South America to the United States on P-1 visas. In this first period, only some victims were exploited. The second time the victims arrived, their documents were confiscated, and they were forced to sleep in the trafficker’s home and pay rent to her. During this time, one of the victims escaped from the trafficker’s home and ultimately reported the incident to the FBI. A federal investigation led by the FBI identified the situation as trafficking. Though some victims initially remained with the trafficker, eventually, the victims were removed and provided with housing. During this investigation, some victims received continued presence and work authorization through referral to an FBI Victim Support Specialist known for his training in obtaining continued presence. However, the criminal case was dropped due to prosecutorial discretion, and individuals who had been granted continued presence under that investigation lost it. Civil and administrative complaints were also filed and remain pending.

In Case 5, one victim was sold to, and forced to marry, a wealthy male trafficker who brought her from her home country to the United States. For nearly two decades, the victim and several family members were all forced to work on the trafficker’s “family farm.” The victim escaped by obtaining a divorce and a restraining order against the trafficker. Though the victim attempted to report her experiences to several local and federal authorities and contacted multiple lawyers and agencies, she faced significant difficulty obtaining help. There was never an arrest or any formal filing of charges. Authorities viewed the case as a domestic violence issue rather than a trafficking case.