As we write this editorial, the coronavirus pandemic is affecting and changing our lives, societies and economies around the world. Places of work, worship, retail and leisure are slowly re-opening but our freedom of movement and way of life has been changed utterly, at least in the short to medium term. If anything, the process of returning to a ‘new normal’ is likely to prove more complex and difficult than shutting down and staying home, with stutters and relapses very likely.

Colleges and universities around the world have adapted quickly, responding with innovative approaches, but students, academics, researchers and professional staff have all been heavily affected. Teaching and learning has shifted on-line with the rapid adoption of new forms of pedagogy and assessment. University operations are being conducted remotely, with huge implications for the governance of institutions and the ways in which critical decisions are made at all organisational levels. International student and academic mobility – a cornerstone of cultural and intellectual exchange from the days of the first universities – has ground to a halt as borders have been closed and travel restrictions introduced. In some places, international students have effectively been abandoned by their host countries and institutions. Research labs have closed and practice-based learning rendered almost impossible.

On the other hand, there has been a renewed interest in, and reliance on, science and experts – and certainly medical and biological science and epidemiologists. The search for a vaccine for Covid-19 could foreground the best of transnational collaborations and networks, strengthened by open science and shared data platforms. While the long-term implications of the pandemic are uncertain, it is likely that recent events will accelerate initiatives around open science and open access – such as the EU's Plan S (Science Europe, Citation2018) – and the shift to open research infrastructures based on FAIR (findable, accessible, interoperable, reusable) principles.

But will the explosion in pandemic-related research be replicated by a wider appreciation of the value and contribution that all disciplines can make to our understanding of societal change? Research studies and funding have been (re)oriented towards meeting public health and medical needs. Most countries have established a pandemic or public health advisory body – but how many of these committees are genuinely multi-disciplinary, with experts from across the arts, humanities and social sciences alongside STEM subjects?

After all, these human and cultural disciplines are critical to understanding how we are going to be able to live with this virus – and others like it – for perhaps many years to come. The severity of the challenges we face are amplified by steep inequalities within and between countries due to poverty, racism, poor and over-crowded accommodation, educational disadvantage and gaping digital divides, poor nutrition and access to health services, poor policy-making processes and social-cultural divisions spurring political unrest and the rise of populism. Higher education's own role with respect to the ‘myth of meritocracy’, too often acting as a gatekeeper, rather than a gateway, to social progress might be explored. Accordingly, we must embrace a much wider understanding of the pandemic, its consequences and how we might mitigate these.

What are the longer-term implications for higher education? What do teaching, research and financial sustainability now look like for national systems– and not just for elite research universities? As colleges and universities struggle to resume and redesign their operations, will this lead to a survival-of-the-fittest and, if so, who decides and how? Is it time to rethink models of institutions of higher education for the 21st century? Ultimately, system and institutional sustainability raises major questions for policy makers and institutional leaders about the overall balance between different types of providers (including public and private) and, most crucially, beyond universities to the rest of the tertiary or post-compulsory education system.

Challenges associated with large-scale unemployment and precarious employment due to the pandemic, alongside projected labour market changes associated with an era of accelerated technological progress could put greater emphasis on the role of higher education as an anchor institution and innovator. Higher education can be seen as an investment in the future but there are potential risks as governments come under funding pressure from other sections of society and the economy (Croucher and Locke, Citation2020). Geopolitical shifts – already reflected in global rankings – are likely to strengthen. This all suggests some macro-trends we have been observing will accelerate. How should higher education respond beyond looking for a bail out?

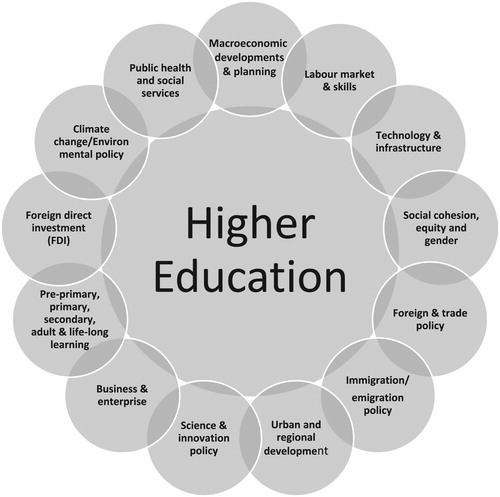

Higher education sits at the intersecting and interdependent crossroads of almost all other public and policy domains as illustrated below ().

Figure 1. Higher Education at the Centre of a Complex Policy Eco-System. Source: Adapted from Hazelkorn, Citation2020.

At a time when liberal democratic systems are coming under sustained pressure across the world, the potential role of education at all levels in underpinning democracy and human rights needs to be acknowledged and emphasised. This opens up a huge agenda for scholars of higher education.

Yet, one of the more disappointing aspects of current academic writing and commentary of recent months, and even years, has been how few topics are covered. There is an abundance of material looking at students, access and retention, teaching and learning, the changing academic profession, funding and tuition, and of course managerialism and performance assessment. There is no doubt that these are important topics, but rarely do scholars interact with industrial or trade policy or regional studies or international governance, to name a few other important areas. A recent blog lamented the standardisation of research, placing blame on journalistic practice and the reluctance to challenge orthodoxy (Goyanes, Citation2020). Another perspective suggests the tendency to view issues as an insider. To paraphrase the former vice-chancellor of the University of Newcastle (UK), Chris Brink: we should not be thinking about what higher education is good at, but what it is good for (Brink, Citation2018).

Policy Reviews in Higher Education aims to be different. We want to encourage and hear from scholars and policy analysts from ALL disciplines. We are interested in in-depth accounts of significant areas of policy affecting higher education in all its dimensions and from international perspectives. We encourage authors from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to analyse higher education from fresh viewpoints, including drawing on concepts and theories from other academic fields and disciplines – and specifically with relevance for policymakers and leaders. This is a time when higher education itself is being asked to respond to the many challenges around us. We set out that same challenge to scholars of higher education policy to do just that.

In this issue, Yaw Owusu-Agyeman and Gertrude Amoakohene examine the benefits, challenges and prospects of transnational education (TNE) delivery in a host institution in Ghana. Challenges included the lack of clear policy guidelines governing TNE partnerships, cultural differences among partners, inadequate learning resources for students, the high cost of fees and difficulty in designing a bespoke curriculum to meet local needs. The study articulates the importance of developing policies that guide TNE delivery and the relationship between partners by regulatory bodies in the higher education sector.

Michael Shattock and Aniko Horvath explore the impact of decentralisation and devolution on universities in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England resulting in four systems with contrasting aims and objectives. They conclude this has been broadly successful in Scotland and Wales, helping to move universities closer to their regional communities without encouraging parochialism or lessening their international competitiveness. However, it has allowed England to adopt a fully marketised approach resulting in greater differentiation between institutions and the establishment of a ‘business model’ of institutional governance.

How do inequalities caused by the urban-rural divide in China adversely impact on the academic trajectories of rural-origin academics from impoverished backgrounds? In her article, Cora Lingling Xu shows how a group of academics cultivated a productive habitus that is characterised by hard work, perseverance and self-discipline. This played a pivotal role in orchestrating their academic ascension and upward social mobility. However, despite these successes, they experienced perennial financial struggles in lifting their rural-based families out of poverty, revealing the exclusive nature of educational mobilities, which are manifestations of systemic structural inequalities caused by urban-biased policies.

The policies for higher education access and success in England and the United States are compared by Kevin J. Dougherty and Claire Callender, focusing on five key policy strands. They draw conclusions on what England and the US can learn from each other. The US would benefit from following England in using Access and Participation Plans to govern university outreach efforts, making more use of income-contingent loans, and expanding the range of information provided to prospective higher education students. Meanwhile, England would benefit from following the US in making greater use of grant aid to students, devoting more policy attention to educational decisions students are making in early secondary school, and expanding its use of contextualised admissions. They conclude that many other countries with somewhat similar educational structures, experiences, and challenges could learn useful lessons from the policy experiences of these two countries.

Finally, Rita Kasa, Ali Ait Si Mhamed and Viktoriya Rydchenko assess whether the success of a policy depends on engaging the bottom-up perspectives of those who are expected to implement it. They examine the views of university leaders in Kazakhstan on the potential impact of a per capita per credit higher education funding model which aims to promote student choice, university quality and competitiveness. The findings suggest that the match between the policy expectations and the goal of strengthened student choice will be contingent upon the ability of universities to introduce organisational processes that enable such a choice. Advancing the quality and competitiveness of universities will be conditioned by university access to funding and the acceptance of personnel of both structural and cultural changes associated with the implementation of the new policy.

References

- Brink, C. 2018. The Soul of the University. Excellence Is Not Enough. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Croucher, G., and W. Locke. 2020. A Post-Coronavirus Pandemic World: Some Possible Trends and Their Implications for Australian Higher Education. Discussion paper. Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education. https://melbourne-cshe.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/3371941/a-post-coronavirus-world-for-higher-education_final.pdf.

- Goyanes, M. 2020. As Academic Writing Becomes Increasingly Standardised What Counts as an Interesting Paper? Accessed June 27, 2020. LSE Blog website: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2020/02/24/as-academic-writing-becomes-increasingly-standardised-what-counts-as-an-interesting-paper/.

- Hazelkorn, E. 2020. Relationships between Higher Education and the Labour Market – A Review of Trends, Policies and Good Practices. Paris: UNESCO.

- Science Europe. 2018. Plan S: Accelerating the Transition to Full and Immediate Open Access to Scientific Publications. European Commission website: https://www.scienceeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Plan_S.pdf.