ABSTRACT

In the context of global debates regarding the purpose of higher education, many national governments have adopted ‘cost-sharing’ mechanisms. Yet in 2017 the Philippines introduced legislation to provide ‘Universal Access’ to higher education by subsidizing tuition fees for all Filipino students in public institutions, partial fee subsidies students in private institutions, and further means-tested support. This article uses a conceptual framework integrating multiple models of social justice to examine 73 legislative texts: 59 individual House of Representative bills, 11 individual Senate bills, the cumulative House and Senate bill, and the final Republic Act. We develop an innovative methodology for analysing legislation that incorporates both structured content and reflexive thematic analysis. The findings show a striking consensus on representing access to HE as a social justice issue, but concepts of procedural fairness varied. Economic rationales intersected with justice narratives, positioning universal tuition as ensuring equal access to income, fostering ‘inclusive growth’ for national development that includes the private sector. The Philippines offers an instructive case for other liberal democracies where ‘who pays’ for higher education remains politically divisive. Our analysis suggests that legislators achieved consensus w by situating social justice as compatible with marketised, neo-liberal paradigms of higher education.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction: charting the legislative journey to ‘universal access’ to higher education in the Philippines

This paper examines how discourses around the concept of social justice influenced the legal proceedings which led to the provision of full subsidies for tuition fees at Philippine State universities and colleges, thus introducing ‘free’ public higher education (HE). Throughout the world, there have been several national initiatives to finance HE through taxation, rather than through tuition fees. Some of these initiatives can be understood in terms of the debate over whether there is a universal right to higher education (McCowan Citation2012). Previous efforts have been analysed to understand whether these initiatives have expanded access to HE (De Gayardon Citation2019) or ‘widened participation’.Footnote1 McCowan’s study of policies in Kenya, Brazil, and England led to his proposal of ‘three principles for understanding equity of access: availability, accessibility and horizontality’ (Citation2016, 645). While there is a need to understand the outcomes of these efforts to remove tuition fees, less is known about the range of legislative discourses as well the processes and motives by which these changes come about. A deeper understanding of these processes is timely and important because the introduction of this policy runs counter to the global trend of increasing ‘cost-sharing’ mechanisms (Jamshidi et al. Citation2012). This article and approach will be of interest to academics studying policy processes and potential alternatives to the neoliberal turn and marketisation of HE. It will also benefit policy-oriented readers who may wish to introduce similar reforms and who want to understand the discursive context that made such a reform possible in the case of the Philippines.

Using an analytical framework that distinguishes between distributive and procedural justice, our study examines all legislative texts or Philippine Congress Bills (n=73) introduced in the Philippine House of Representatives related with and leading to the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act or Republic Act 10931 on 25 July 2016. The Act introduced what is often referred to as ‘free higher education’ at State (public) universities and colleges in the Philippines. This initiative is framed as ‘free’ to the student, in the legislative documents as ‘free tuition’, though evidently funded by the tax-payers. We use this terminology to unpack the discursive implications, with a critical awareness of the framing. This analysis – by identifying ‘justice discourses’, by analysing legal texts and by explaining the links to the HE policy mechanisms of the Philippine, is important in how it explains what kind of discourses create possibilities for enacting policy changes counter to international trends.

This paper aims to explore how concepts of social justice influenced the debate around eliminating tuition fees in the Philippines. In doing so, we make three significant contributions. First, we make a conceptual contribution concerning demonstrating the use of the justice framework when studying a range of legislative texts. Second, a methodological contribution in the field of HE is developed with attention to earlier – and not only final – versions of legislation when analysing policies. Finally, by reporting on a lesser-known national system, this article makes a knowledge contribution about policy development and innovation in an emerging economy that will be useful for studies of other systems, especially those outside the Global North. In particular, our final contribution gives an important insight to campaigners for this tuition subsidy reform: that it is important to recognise the legislative context and build coalitions with private enterprises in systems, such as the Philippines and many developing countries, that are characterised by a marketised environment in education provision and governance. Our analysis shows what kind of language and framings could be used to achieve this consensus, specifically the narratives of distributive justice deployed in the service of ‘economic growth’.

Applying a justice-oriented framework helps to explain the various demands for legitimacy that Philippine law-makers faced and responded to when debating the legislative bills. In other words, this article asks, using the legislative texts, ‘what was the purpose of ‘free higher education’ in the Philippine legislative debate?’

The article is structured as follows. We first (1) illustrate the central rationales behind distributive and procedural justice. We then (2) present the Philippine HE context. Next, we present our (3) methodology and (4) findings linked to the different models of justice. These lead to a discussion about (5) the data concerning justice and (6) the implications for evaluating the outcomes according to what are the stated legislative aims. We then (7) conclude and offer ideas for further research.

Justice frameworks – distributive and procedural justice

By first outlining the purposes of three conceptions of justice, our study elaborates a framework of social justice originally developed in the context of organisational behaviour by Nancy Fraser. Fraser’s argument that justice should be understood as the parity of participation (Fraser Citation2008) has been applied to the study of HE access in the Global South, such as Tanzania (Msigwa Citation2016). The use of justice frameworks and, in general, of discourses of justice and fairness in accessing HE has become more important since the introduction and increases in tuition fees in many systems, which often use different terminologies. In the UK, for instance, justice discourses are involved in the debates around ‘widening participation’ which is a broad term aiming to address inequalities – including economic inequalities – that affect whether students enter HE. Our use of justice frameworks draws from this and other traditions to examine the Philippines. For instance, we also draw upon the work of Folger (Citation1987) who explored the ‘optimal’ reward allocation mechanisms, i.e. how people were rewarded for performance in organisations, to distinguish between procedural and distributive justice. Folger’s framework generally uses procedural justice to relate roughly to processes and distributive justice to outcomes. In this article, however, the analysis is somewhat broadened by also considering certain ‘input’ factors as having a potential effect on distributive outcomes.

One of the contributions of our study is the adaptation of this framework to analyse the complete range of legislative texts in the Philippines that were drafted to subsidise tuition fees in HE institutions. We argue that a justice framework is suitable for analysing the range of legislative texts because of the nature of law, which is concerned with the maintenance and provision of fairness. Lawmakers are often tasked with ensuring that both outcomes and processes are fair, and often deploy globalised discourses of justice in order to legitimise their decisions.

Distributive justice is arguably the most conventional understanding of social justice. It refers to the ‘fair’ allotment of resources among members of society. While various formulations exist, a classical definition by Rawls (Citation1999:, 6; orig 1971) describes it as: ‘the way in which the major social institutions distribute fundamental rights and duties and determine the division of advantages from social co-cooperation’. Rawls’ famous thought experiment about the veil of ignorance invited his listeners to consider what kind of society they would want to live in if they were to be born again but with total ignorance as to the circumstances of their birth (i.e. that they could not control who their parents were or in what kind of social context they would be born). In this context he argued for a ‘just’ society in which there was a fair distribution of resources: both material and non-material (Gewirtz Citation1998). This concept recognises that there are competing claims for resources but that a ‘proper balance’ ought to be found (Rawls Citation1999, 5). Related to this competition for resources is another more atomistic conception, which describes justice as a situation where ‘everyone receives their due’ (Miller Citation1979, 20). Here, justice is oriented around the distribution of goods to individuals. This relates to the general conception of education, especially HE, as a private good: here certain social groups have differential access to, and rates of participation in, HE and its consequent private benefits, it becomes a matter of distributive justice. These benefits can be understood as ‘human capital’, the capacity to generate increased wealth and quality of life as a result of higher levels of qualification, specialist knowledge and skills that HE signifies (Marginson Citation2011). Contemporary global discourses of higher education policy are shaped substantially by human capital and by the corresponding notion of the knowledge economy which suggests a country can accelerate its development by investing in the human capital of its workforce.

There are further refinements to the notion of distributive justice which range from equality of opportunity to equality of outcomes. In the former conception, ‘unequal results are justified if everyone has an equal opportunity to succeed’ (Lynch Citation1995, 11). In the latter, resources are distributed such that everyone has the same things.

Procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness of the processes involved in making decisions about resource distribution. Thibault and Walker (Citation1975) discussed procedural justice as separate from distributive justice. This proposes that people are concerned about the fairness of the procedures and processes of decision making (ibid) and that they are even willing to accept outcomes – even if they do not always get what they want – if the processes are seen to be fair (Tyler and Folger Citation1980). In the example of access to HE, if admissions processes are fair, transparent or blind to the social circumstances of the applicant, they can be considered procedurally just. In the case of the University of the Philippines, a competitive entrance examination offers the appearance of purely meritocratic entry into the elite state university, thus offering a reassurance of procedural justice.

Finally, Fraser’s conception of social justice encompasses economic, cultural, and political aspects of social justice (Fraser Citation2008), on a spectrum from approaches that affirm the existing power differentials to those that transform it. This broad conception includes a distributive aspect: as the distribution of resources is meant to avoid dependence and general inequality. In her work, Fraser (Citation2008) shows how the nature of the state is an important context for the achievement of social justice. The Keynesian state is responsible for providing equality of opportunities for all citizens in the former through redistribution, whereas the post-Westphalian state is concerned primarily with how the political community is represented with a greater emphasis on the representation and participation of citizens (Fraser and Honneth Citation2003; in Msigwa Citation2016).

Following Msigwa’s (Citation2016) examination of access to student loans in Tanzania, this study adapts two aspects of Fraser’s conception of social justice: redistribution (linked to our earlier discussion of redistributive justice above) and recognition. The former is linked to the economic aspect of justice and the latter requires policymakers ‘to recognise the claims of groups marginalised in a society due to their sociocultural identity’ (Msigwa Citation2016, 548). Redistributive justice goes still further than distributive justice, by seeking to re-allocate historically unfairly distributed resources, such as land. An example in relation to HE could be affirmative action programmes that introduce special recruitment policies to ‘overcome the effects of conditions which resulted in limiting participation by persons from a particular race, colour, or national origin’ (Regents of University of California, 1978, cited in Solórzano and Yosso Citation2002). In the Philippine case, the University of the Philippines applies an algorithm that weights the results of its entrance examination with other socio-economic and demographic factors to determine admissions results but the rest of the public sector does not implement any such practices. Similarly, recognition justice seeks to redress historic injustices pertaining to ethnic, religious and other social groups, by explicitly acknowledging that affiliation and its significance.

By using the framework drawing upon these three conceptions of justice, we do not wish to overlook other aspects of justice. Indeed during this study, other frameworks such as relational justice and epistemic justice were also initially used to analyse the data. The former relates to a dimension of justice that is ‘holistic’ and ‘concerned with the nature of interconnections between individuals in society, rather than with how much individuals get’ (Gewirtz Citation1998, 471). It points to a shared understanding of HE as a public good. The latter refers to potential dynamics of cultural power concerning how access to knowledge and participation in discourse are mediated. However, after a careful reading of our data, there were few hints at either epistemic or relational concepts of justice in the legislation. We determined, therefore, that the distributive and procedural aspects combined with the notion of ‘recognition’ within Fraser’s wider construct of social justice best explained the tensions in the legislative debates. In the following section, we set the scene to understand the context of the introduction of free higher education.

The higher education system in the Philippines

The Philippines has a population of 109.6 million people (World Bank Citation2019.) spread over 13 regions, three island groups, and over 7,000 islands. The HE sector is correspondingly large and diverse. The Philippine Commission on Higher Education (CHED), HE’s governing body and quality assurance agency in the Philippines listed 1,943 higher education institutions (HEIs) (CHED Citation2014). with a high global enrolment rate relative to comparable countries: 35% of the relevant population by age (UNESCO Citation2017)HEIs -particularly top-ranking institutions – are concentrated in the capital, the Metro Manila area, and its island of Luzon. The Philippines has a constitutional commitment to private HE, and 88% of HEIs are private, enrolling 56% of students in 2013 (CHED Citation2013).

The tuition fee reforms took place in the period of rapid economic growth of 6.4% between 2010–2019 (World Bank Citation2019), led by a strong service and industrial sector, but also by remittances from overseas workers (QAA, n.d.). Yet the Philippines remains characterised by a ‘highly inequitable structure of society’ (CHED Citation2017)There are significant income-based disparities in access to HE: while 19.7% of the school age population in the richest 70% of families were enrolled in tertiary education, only 4.6% of the poorest 30% were (Philippine Statistics Authority Citation2015).Footnote2

On average, in 2012, a student in a private HEI would pay 237,600 pesos (approx. 3,542 GBP or 5,616 USD at the time) for a four-year course (CHED Citation2013), whereas a ‘top-tier private university’ would cost nearly double. SUC fees in an ‘average quality programme’ were approximately 64,000 pesos (approx. £947). This excludes transportation, accommodation, and other expenses, which are substantial – nearly 20% of the total average cost of attending university (CHED Citation2017). Bearing in mind the geographic challenges mentioned above, for many students located outside the capital region, living at home and studying is not an option, due to limited local availability. Not only, therefore, do richer Filipinos more often access HE, they also access better quality, cheaper HE, since they can more easily travel and live away from home. Prior to the introduction of the reforms discussed here, these costs were borne by students and their families, supported by a piecemeal scholarship and student loan system, UniFAST.

The public sector plays an important role in Philippine HE, with 46% of students enrolled in a public institution (CHED Citation2013). Officially, the sector is defined by a ‘horizontal typology’ (CHED Citation2014), with universities, colleges and Technical Vocational Institutions (TVI) meeting different national, community and local needs (ibid.p.13). Public universities, known as State Universities and Colleges (SUCs), are directly funded by the government (Republic Act Citation8292), with a key nation-building function. For example, the flagship University of the Philippines (UP) has as part of its legislative mandate to ‘serve the Filipino nation and humanity’ through its research and teaching. All SUCs are governed by a cap on student numbers in line with funding, however, according to Tan (Citation2012, p.149) they are often established locally by congressmen to enhance their political power and ‘protect their parochial interest’.

In practice, however, the number and distribution of SUCs does not necessarily match local or national need. Typically, SUCs are seen as higher quality providers than private providers, with more selective, competitive admissions processes. As mentioned above, UP, for example, has a specialised standardised test (UPCAT) with acceptance rate between 15-19%. Results are combined with contextual data (student’s home region, membership of a cultural minority, etc) and with high school results to generate offers (Daway-Ducanes, et al. Citation2018). A greater proportion of SUC students – 27% – come from the richest 20% of the population, while only 8% come from the poorest 20% (CHED Citation2017). On average, students from richer families tend to access higher quality institutions at higher rates than students from poorer families, in other words. This is borne out by Daway-Ducanes, Pernia, and Ramos’s (Citation2018) analysis, which confirmed a statistically significant ‘income effect’ in UP’s admission rates, despite contextual admissions.

While many countries in the Global South rely on the private sector (Castaneda et al. Citation2020), Philippine HE is also unusually characterised by a constitutional commitment to private institutions, These private institutions include both for-profit and not-for-profit, religious and secular institutions. In contrast to the number caps on the public sector, a ‘populist policy’ allowed the expansion of the private sector to meet demand (Tan Citation2012). The private HE sector is seen as a powerful domestic policy actor, creating challenges for the regulatory regime which is compromised by a lack of support from officials with vested interests, making it challenging to, for example, close well-known degree mills operating in the private sector. In the words of the then-Chairperson of CHED, Patricia Licuanan, the HE system is ‘chaotic’, ‘marked by too many higher-education institutions and programmes, a job-skills mismatch, oversubscribed and undersubscribed programmes, deteriorating quality and limited access to quality higher education’ (Robles Citation2012).

Economic growth, as mentioned above, supported the position of legislators introducing ‘free’ HE. From 2016 to 2017, the HE budget increased by 45% as a response to the legislation (Beltran Citation2019) and took place alongside another important policy change meant to foster economic competitiveness, the extension of compulsory education from 12 to 13 years. Prior to the ‘free’ public HE act, investment in education was consistently below recommended United Nations levels, in contrast to comparable Southeast Asian countries like Thailand and Indonesia which had invested considerably more over recent decades. CHED characterises this as a ‘relative neglect of higher education’ (Citation2017, 4). This is the context within which the legislation implementing universal tuition fee subsidies was introduced.

Universal access act

The precise nature of the ‘free tuition’ bill (Republic Act 10391 Universal access to quality tertiary education, hereafter RA) is as follows. To meet its responsibility to ‘promote the rights of all students to quality education at all levels’ the act makes several declarations of policy, prior to establishing the specific mechanisms, namely that the State should:

Provide adequate funding and such other mechanisms to increase the participation rate among all socioeconomic classes in tertiary education;

Provide all Filipinos with equal opportunity to quality tertiary education in both the private and public educational institutions;

Give priority to students who are academically able and who come from poor families (RA10931).

Points ‘d’, ‘e’ and ‘f’ concern the effective use of government resources, career guidance and the complementary role of the public and private sector.

To meet priority b, the RA made ‘all Filipino students’ enrolled in any SUC or tertiary vocational institute exempt from paying any tuition fees, and made it illegal for any SUC to charge tuition fees. Eligibility is limited solely by institutional admissions criteria, not already having an equivalent or higher degree, and meeting the ongoing attendance and academic expectations of the institution. The claim to ‘universal access’ is bolstered by the short list of eligibility criteria, however, it will be noted that selective admissions criteria do still apply. Institutions are to predict their student numbers for the next year to agree a budget with CHED, which implies an on-going student number cap set by evaluations of enrolment capacity (CHED / UniFAST Citation2017). Precisely what is meant by ‘Filipino students’ is not defined by the RA, or the subsequently issued Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR hereafter) (ibid), but is presumably intended to exclude international students, though whether by citizenship or residency is unclear.

The funding for this act is assigned to the annual General Appropriations Act, based on the budgets agreed, and the government is authorised to prioritise this funding from a range of other sources. In contrast to some of the earlier legislation, which assigned specific sources of funding such as the President’s Social Fund (e.g. HB5581), this makes funding for the general tuition fee subsidy contingent on an ongoing national budget surplus.

Priority c allocates further means-tested support via the ‘Tertiary Education Subsidy’ (TES). The first and most significant clause here is that students can apply the TES to private HEI tuition fees to the amount equivalent to those of the nearest SUC. This in effect extends the tuition fee subsidy to private HEIs, generating a partial subsidy should the private HEI fees be higher than the equivalent public institution. As indicated in the previous section, this could be as little as 5-10%.

In addition, students in public or private institutions can apply this to the costs of books, transportation, room and board, disability related expenses, and professional licence or certification. Means are tested by whether students are included on the ‘Listahan 2.0’, a comprehensive national government database of poor families and their income status. Students with lower incomes would be prioritised, based on budget availability. In the IRR, CHED also specifies that certain groups will be eligible for inclusion in an expanded list including: indigenous peoples, those implicated in the peace process, namely the Muslim minority of Mindanao, farmers and ‘other disadvantaged groups’ (CHED / UniFAST Citation2017).

The existing student loan programme UniFAST is also strengthened to further supplement any shortfalls. This is available to all Filipino students in any tertiary institution, public or private, at graduate as well as undergraduate levels.

Philippine governance

Our approach to the design and particularly the analysis of this project derives from the particular governance structures and legislative process of the Philippines.

The Philippines is a representative democracy, modelled after the United States of America, with two chambers of Congress, the Senate, and House of Representatives, under the leadership of the President. With voter turnout typically above 75% (Gavilan Citation2016), the Philippines shows a comparatively high democratic engagement in elections. However, as Jackson (Citation2014) highlights, political engagement beyond voting is very limited, perhaps due to declining rates of trust in politicians (Quah Citation2010). Rates of participation in civil society are highest among the socio-economic elites, with an enduring traditional ‘advisor/patron’ to ‘client’ political relationship (Jackson Citation2014). Senators rely on this type of support for election campaigns, which Caoili (Citation2005) describes as representative of the broader ‘norm of corrupt practices and elite control’.

The 24 senators hold their seats nationwide and do not represent a geographical district. 80% of Representatives to the House represent a geographical district, with 20% allocated to party lists, which are intended to represent marginalised and underrepresented groups, such as fishermen and farmers, veterans, women, urban poor, students and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender groups. Officially, the 1987 constitution established a multi-party system requiring coalition governance, but these parties are ‘weak’, with frequent party-switching from legislators and limited ideological coherence (Teehankee and Kasuya Citation2020).

In contrast to many other countries where taxpayer-funded tuition systems are well established or contemplated, political parties are a less significant force in the Philippines (Aceron Citation2009). Congressmen/women can be elected without being a member of a political party at all. The finalised Senate Bill for ‘free tuition’, for example, was sponsored by 8 Senators from multiple parties. It is therefore important not to externally impose a partisan reading of this legislation, as it does not derive from a left-wing or socialist ideology. Indeed, the finalised legislation has come under heavy criticism from the most left-wing party commentators (e.g. Elago Citation2017).

Multigenerational political dynasties remain common, with established families and their extended networks comprising an average of 70.4% of district legislators in the House from 1987–2016 (Teehankee and Kasuya Citation2020). Political clans like the Aquino family dominate, leading to the continued description of the Philippines as an ‘elite democracy’ (Bello and Gershman Citation1990), and even as ‘the most persistently undemocratic democracy in Asia’ (Rocamora Citation2004). This is underpinned by patronage, the provision of material benefits by politicians in return for political support (Teehankee and Kasuya Citation2020). Indeed, Senator ‘Bam’ Aquino, a third-generation senator with two family members who have served as President, is a key sponsor of this reform.

Congress is responsible for making laws that uphold the spirit of the constitution or amend it (Republic of the Philippines Citation1987). Both can create ‘resolutions’ to convey principles or sentiments, or bills, which can become law with the President’s signature. Bills are sponsored by individuals or groups of legislators in either chamber, then read and referred to a committee (Faustino and Fabella Citation2014), such as the Committee on Higher and Technical Education. The committee conducts a hearing and produces a report. In the case of the free tuition bill, the volume of initial bills in the House of Representatives was such that 58 bills were considered together and substituted in a single House Bill (no.5633). Should differences arise between house and senate versions, a bicameral conference committee will be organised. The resulting bills are scheduled for second readings in both houses. The final legislation will thus represent a consolidation of the bills from both Houses.

Data and methods

This paper aims to explore how concepts of social justice influenced the debate around eliminating tuition fees in the Philippines. We adopted a documentary approach, examining all legislation proposed during the 2016/17 Congressional session, before the signing of the official Act. The research process as described below conforms to the ‘interpretive bricoleur’ described by Denzin and Lincoln (Citation2011, 4): ‘a pieced-together set of representations that are fitted to the specifics of a complex situation’. We wanted to understand how narratives of social justice informed the implementation of the universal access legislation; we had the documentary data, and we found a way to build a set of representations through a multi-stage analysis, described below.

Data – legislative texts

All bills are made publicly available through the Philippine Congressional website (http://www.congress.gov.ph/) and are assigned a number unique within that Congressional session, and these are used throughout the analysis. ‘HB’ refers to a House Bill and ‘SB’ refers to a Senate Bill. Each bill is presented with an accompanying ‘explanatory note’ that justifies the bill with evidence or explanation. The bills typically include 13–24 articles, each of which proposes a specific measure.

The final Republic Act (RA) lists the Senate and House bills which led to the final act. We used this list to identify the core legislative texts, working backwards through each stage of the legislative process to identify the previous bills. We also used the text search function and the keywords ‘higher education’ and ‘free tuition’ as a final check to ensure that we included all relevant legislation. We established as inclusion criteria that bills should be submitted in the 17th Congress (2016-17), and that they should relate to HE and some form of increased subsidy to students. Bills relating to other aspects of HE governance, such as the creation of new universities, were excluded.

A total of 73 legislative documents were identified for analysis (see Appendix 1 for the complete list). In the House of Representatives, 59 individual bills were filed and 11 in the Senate (n=70), in addition to the cumulative House and Senate bill, and the final Republic Act (n=73). While this is a comparatively small proportion of the total 9,210 House and Senate bills, it does suggest a remarkable concentration of attention.

Method of analysis

We adopted two complementary analytical approaches. Firstly, we used content analysis to conduct a functional analysis of the proposals in the legislation. This was considered an important step, as we predicted this would operationalise notions of justice, particularly procedural justice. Secondly, we adopted an interpretative lens through thematic analysis of ‘explanatory notes’. This approach allowed us to examine both the rationales relating to social justice and the concrete mechanisms proposed through the legislation.

Content analysis

The articles of the bills all follow a clear genre structure, with rhetorical moves and established key phrases. For example, each bill includes an article detailing the definitions of relevant terms such as ‘scholarships’ or ‘tuition subsidy’, meaning that the core proposition of the legislation was easily identified. Because they followed such a clear schema, a content analysis approach enabled straightforward comparison. Content analysis is a well-established approach that Krippendorff (Citation2018) defines as ‘a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from data to their context’ (p.403), most often texts or other written documents. The researcher establishes ‘rules of inference’ or ‘analytical constructs’ to interpret meaning from the text (White and Marsh Citation2006). While well established in legislative studies (Slapin and Proksch Citation2014), content analysis of legislative texts is rarely used in HE policy research. Notable exceptions include Chu (Citation2019), Roumell and Salajan (Citation2016), and Weaver et al. (Citation2013).

We identified a wide range of different proposals in the full sample and decided to focus the analysis on the ‘core’ texts, namely those which specified that tuition fee at State Universities and Colleges should be subsidised, from those listed as contributing to the cumulative House Bill (5633) and Senate Bill (1304), highlighted in bold in . This resulted in 11 House bills, and 6 Senate bills, as well as the Republic Act (RA) itself (see ). To generate a transparent ‘audit trail’ through the data, we report the documents using the unique bill number attached to the legislation, where ‘HB’ denotes ‘House Bill’ and ‘SB’ denotes Senate Bill. The names of legislators are included where relevant.

Table 1. Core legislative texts by date.

Content analysis typically takes a highly structured approach, usually deductive with an analytical framework established before engaging with the data (e.g. Weaver et al. Citation2013). Our approach deviated from this by creating an inductive analytical framework, expanded through a close reading of the documents. All articles from each bill were summarised into an Excel table, with headings developed to describe the function of each article, such as ‘definitions’. Headings were added when later documents included a new article or a key characteristic.

These headings included:

Bill number

Short title

Representative / Senator

Date

Declaration of policy

Eligibility

Exceptions

Payment

Special Tuition Subsidy fund

Appropriations

Administration of fund / implementation of act

Student Financial Assistance Programme

Student Loan Programme

Accountability

Requirements for HEIs

Evaluation metrics/ Midterm report

Tuition report

TVET

Implementing rules

This enabled a functional analysis of the different measures, followed by a thematic analysis.

Thematic analysis

The explanatory notes of core texts were thematically analysed to explore the rationales and identify how conceptions of justice appear. The explanatory notes varied in length, range of rhetorical moves, styles, use of evidence, and so on. Some contained 4–5 pages of detailed research and evidence; others started with an emotional anecdote, naming individual students who committed suicide because of tuition fees, for example. This discursive richness of rationales, grounded in multiple conceptualisations of social justice, made the use of reflexive thematic analysis appropriate (Braun and Clark Citation2019).

All explanatory notes were converted to text documents and added to an NVivo database, to facilitate qualitative analysis. While the software is not a prerequisite for rigorous qualitative data analysis, it does make managing larger and more varied datasets easier and enables consistency checking (Bazeley and Jackson Citation2013). Most explanatory notes were in entirely English, but where phrases of Tagalog were included, these were translated into English by one of the researchers.

Initial coding involved assigning inductive codes, based on en vivo coding using the language of the texts (Saldana Citation2015), to each line of the explanatory note (see below for a full report of the coding structure). Relying on multiple close readings of the text, inductive coding identifies phrases that are frequently repeated, conceptually important, or taken for granted.

Table 2. Coding structure.

As new codes were introduced, keyword searches were used to ensure that newly introduced codes were retrospectively applied to all documents (Bazeley and Jackson Citation2013). Once initial coding was complete, code reports were checked for consistency and redundancy. Codes were merged if they were too similar, disaggregated if they had grown too large and generic, and deleted where they were not relevant to the research questions. Throughout this process, related codes were assembled under broader ‘parent’ codes to develop a hierarchy of themes. Not all ‘parent codes’ were sufficiently complex or frequent in the data to warrant splitting into child codes. Most of the coding was undertaken by one researcher for consistency, with a selection of codes reviewed by the other to sense check. These procedures demonstrate the rigour and systematicity appropriate to a qualitative project located in a constructivist paradigm.

Themes were developed by placing these codes, and the results of the content analysis, in dialogue with the theoretical framework of different concepts of social justice.

Denzin and Lincoln (Citation2011) establish five criteria for the evaluation of qualitative research. First, this study is dependable, since the data in terms of the corpus of documents established in 2016 are stable; they cannot be changed. The content analysis is highly confirmable, in that the meaning of the data regarding the analytical categories as presented in are fairly objective; these categories were deliberately kept quite descriptive. The study is authentic in that our analysis highlights a range of realities. The findings have the potential for transferability, since they draw on increasingly globalised understandings of social justice and neoliberal discourses. Credibility is more challenging to conceptualise in the context of a content analysis study, but in line with Elo et al.’s (Citation2014) checklist approach, the trustworthiness of the data collection and analysis of this study rests on its transparency.

Results

This section reports on the extended database of 73 items of legislation (see Appendix 1 for complete list), and the content analysis applied to the articles therein.

The 70 individual bills (i.e. excluding the 3 cumulative bills from the Senate, House and Senate and the final Republic Act) typically fell into one of several categories: either proposing targeted scholarships, loan programme expansions, full-tuition subsidies at SUCs, or ‘free college’ (functionally, these proposals were often identical to the ‘full tuition’ category), with occasional outliers relating to embassy assistance or vouchers (see below).

Table 3. Summary of individual bill policies.

This categorisation is a preliminary contribution to understanding the themes involved in the range of legislative documents leading up to the policy.

The content analysis demonstrated that the final RA included several articles that had not been present in any of the previous legislation, namely the inclusion of the private sector, the Technical and Vocational Education sector (TVET), the use of a key national indicator of poverty levels to prioritise access (the Listahanan), the expansion of ‘free tuition’ to encompass accommodation and related expenses, and the expansion of a Student Loan Scheme.

We identified which groups or institutions were the target beneficiaries of each legislative document. In individual bills, the most common framing was to propose full tuition fee subsidies to state universities and colleges (SUCs). However, scholarships intended to target groups either particularly ‘deserving’ or particularly marginalised are also a dominant narrative (see below).

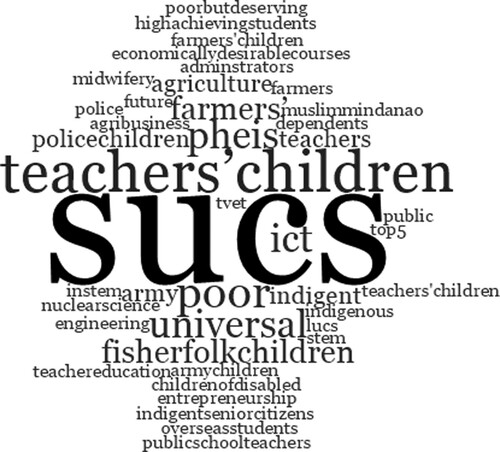

A frequency analysis reveals a consensus on distributive justice, i.e. a general acceptance of economic inequality as the main obstacle to access to HE and an agreement to resolve it. However, the plurality of proposed solution mechanisms demonstrates a lack of consensus on procedural justice, i.e. on how distributive justice is to be achieved. illustrates, using frequency analysis which corresponds to the relative size of the text, how ‘state universities and colleges’ emerged as the dominant beneficiary institution. It also indicates that, except for the single bill relating to providing greater embassy assistance to overseas students, all the bills relate to facilitating access to HE for students currently excluded or unrepresented. Yet there is a wide variety of mechanisms proposed in , from targeting scholarships to particular groups, loans, vouchers, to establishing a broad base of ‘free tuition’ to offering ‘free college education’ to one household. Some are quite selective, targeting the ‘top 5% graduates of public science high schools’ (HB2596), information and communications technology subjects (HB33, 3149), ‘economically desirable subjects’ (HB5078), or ‘science, technology, mathematics, and engineering’ (HB1054). Each of these bills acknowledges that access to HE is mediated in the Philippines by economic capital.

In the core texts, however, there was even greater consensus. The content analysis demonstrated that the bills proposing full tuition subsidy or free college, which make up our ‘core’ as explained above, often shared nearly identical proposals (though quite different rationales, as will be explained below). Of the 17 bills proposing ‘full tuition subsidies’, 15 were directed at SUCs. Most made an initial declaration of policy that substantially resembled the following:

It is hereby declared that accessible and quality education is an inalienable right of the Filipino. Therefore, it shall be the policy of the State to make higher education accessible to financially disadvantaged but deserving students. Towards this end, the State shall renew its constitutionally mandated duty to make education its top budgetary priority by providing free higher education for students in State Universities and Colleges (SUCs). (e.g. SB1304)

However, the source of consensus is not necessarily an ideological affinity based on particular understandings of social justice. Our content analysis also provides textual evidence of the significant role that patronage and clan politics plays in Filipino politics (Faustino and Fabella Citation2014). We identified several legislative bills submitted by a pair of brothers (Rep. Wes and Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian, also to Rep. LaRoque Jr.) and by a pair of spouses (Rep. Vilma Santos-Recto and Sen. Ralph Recto) with not only identical propositions but also identical explanatory notes, suggesting that the ties of politically powerful families operate across both houses of Congress, generating consensus even before bills reach the floor for debate.

The extent of the final legislative consensus was remarkable: 152 Representatives sponsored the Act that became the final law, and not a single lawmaker present voted against or abstained (Cepeda Citation2017).

In the next sections, we examine how the narratives of distributive, procedural and recognition justice were constructed in the explanatory texts of the legislation. We suggest that pre-existing consensus on the validity of distributive justice facilitated the development of consensus on procedural justice, where both are underpinned by neoliberal ideology.

Distributive justice

We found that the predominant justification for introducing free tuition was that access to quality education, including HE, was understood and presented as a right available to all Filipino citizens: the declaration of policy in the final version of the Republic Act is to ‘(b) Provide all Filipinos with equal opportunity to quality tertiary education in both the private and public educational institutions’ (RA10931). In the words of Rep. Wes Gatchalian (HB2635): ‘Thus when in the constitution they tell us that ‘The State shall protect and promote the right of all citizens to quality education at all levels and shall take appropriate steps to make such education accessible to all,’, it is nothing short of a sovereign mandate which we as representatives are duty-bound to enact.’ In terms of the conceptual framework established above, the understanding of distributive justice as equality of opportunity was more significant than equality of outcomes here.

But multiple understandings of justice informed the debate around free tuition. In some cases, the broad appeal to social justice was explicit: ‘By improving the access of students to tertiary education, complemented by the efficient and transparent management of public funds, the State shall be able to promote true social justice’ (HB5015, emphasis ours). The final Republic Act emphasises individual rights rather than social justice per se: ‘It is hereby declared that quality education is an inalienable right of all Filipinos and it is the policy of the State to protect and promote the rights of all students to quality education at all levels’ (RA 10931). This emphasis on individual rights rather than a collective model of social justice is important for later. The notion of ‘quality education’ appears frequently throughout the legislation, as a taken-for-granted concept that is not challenged or problematised. It has been beyond the scope of this analysis to unpack the implicit models of quality, but we highlight this as a rich potential area for future research.

There is little trace of opposition to the principle of distributive justice implicit in the provision of ‘free tuition’. Most of the explanatory notes accompanying legislation, and available speeches, employ the same arguments. Firstly, they agree on overcoming income inequalities that prevent equal access to HE, in particular SUCs. For example, Rep. Villarin suggests that ‘It is evident that income inequalities prevent the youth (sic) from having access to education’ (HB3452). Frequently, data is cited showing that ‘In the Philippines, 2 out of 5 high school graduates do not pursue tertiary education, hindered by the high tuition fees in addition to miscellaneous expenses incurred while studying’ (Revilla, HB4701) (see also HB1942, HB4902, SB61, SB962, and SB1220).

Almost all the legislation examined here refers to the exclusion of poorer students, either in technical language or more emotive terms. For instance, Senator Aquino explains ‘After spending many years working hard to make ends meet to put their children through school to obtain a high school diploma, it is often a disappointment to students who face the choice between working to help their family or sacrificing the education of other siblings so that one may be sent to college’ (SB177).

The burden of tuition fees is sometimes explicitly framed as a matter of equity of access. For instance, Sen Gatchalian and Rep. Herrera-Dy both argue verbatim that ‘Glaring inequity in access to HE continues to impede the Filipino's right to education at this pivotal level’ (SB198, HB5364). Eradicating this ‘glaring inequity’ is seen as a ‘progressive move’, characteristic of a developed nation making investments appropriate to its aspirations in the global economy. Similarly, Rep. Revilla (HB4701) proposes that ‘In a nation with glaring income and educational inequality, the provision of tuition-free college education will be one great leap to empower economically and socially the poor and low-income Filipino families to fully participate in our democracy’. Free tuition is therefore constructed as a matter of equity not simply in terms of access to HE and the human capital gains derived therefrom, but also in terms of democratic participation – a wider framing of social justice. However, it is noticeable that there are few references to inequalities deriving from sociocultural identities (Fraser Citation2008).

However, there was vocal public opposition to the universal free tuition scheme, on the grounds that it would not actually achieve distributive justice. Several quasi-governmental bodies, including the HE regulator CHED and the Philippines Institute for Development Studies, and non-governmental bodies like the Foundation for Economic Freedom, published detailed opposition to universal free tuition. They critiqued it as a regressive move, leading to the capture of the most significant benefits by the middle classes, who predominate in SUC enrolments (CHED Citation2017; FEF Citation2017; Orbeta and Paqueo Citation2017). As mentioned above, richer students are over-represented in contrast to poorer students in SUCs (CHED Citation2017). Thus, these bodies argued that ‘pro-poor’ measures would instead enhance student loans or ‘Grants-in-Aid’ programmes specifically targeted at the poorest students. In contrast, rebuttals from Senators highlighted that even the top 20% of the population may have limited disposable income (Recto Citation2017). Political cynics might observe here that the middle classes, as elsewhere in the world, play a disproportionately powerful role in Filipino politics (Rivera and Citation2011), suggesting that a politician interested in re-election (if that is not a tautology) would be wise to safeguard their interests. This critique implicitly references concepts of redistributive justice.

Neither proponents nor detractors of these proposals engage with the ways educational inequality is structured, however. Given the performance-based entrance exams applied by SUCs in the Philippines, economic status and family educational capital are likely to determine attainment in secondary education and therefore make it less likely that disadvantaged students are even eligible for HE (Reardon Citation2013).

Thus, even where free tuition is opposed, the central narrative that poor students need improved access to HE as a matter of justice is not challenged. The framing of these arguments is not ‘for or against’ distributive justice, but rather contrasting understandings. Opponents to the tuition subsidy imply that distributive justice must be targeted at the poorest, i.e. must be redistributive. Supporters in contrast argue that it is just to provide opportunities to any who may need it, demonstrating the rhetorical power of the ‘universal’ tuition subsidy adopted in the final legislation. What we explicitly did not see in the dataset was an understanding of distributive justice as equality of outcomes. Certain aspects of neoliberalism, namely human capital theory, inform the framing of the distributive justice narrative, where the imperative to provide more equal access to HE is accepted as a common good, since it generates widespread economic growth (Kandiko Citation2010). Instead, the question raised is ‘how best to achieve this goal?’, whether through universal free tuition or targeted subsidies, scholarships, and grants; in other words questions related to procedural justice.

Procedural justice

One of the most notable changes from early drafts of the legislation to the final Act is the inclusion of the private HE sector. The short titles in above indicate that the focus of the early core bills was on the state sector and typically did not explicitly incorporate technical-vocational institutions (TVET) (e.g. SB1304), or private HE institutions. Both were subsequently introduced in the cumulative House and Senate bill (5633) and sustained in the final RA. It is clear from this change that the TVET and private sector had a voice in the House committee hearing and/or bicameral conference hearing. In the final legislation, students can apply the subsidy to private HEI fees to the amount equivalent to the nearest SUC. The private HE sector thus derives a measure of benefit from the initiative. This can be understood both as a matter of procedural justice and as pragmatism, as follows.

Given the geographic distribution of SUCs explained above, many potential students live in areas underserved by public HE, where private HEIs (whatever their shortcomings in terms of quality) may be their only realistic option for access. Ensuring that these students have access to state funds is therefore a matter of equity. There is also a pragmatic concern that if private HE was entirely excluded from the subsidy, there would be a massive exodus of students and staff from the private into the public sector, with potential ramifications for quality (CHED Citation2017). Additionally, the Philippines has a constitutional mandate to support private education, including HE, so legislation that threatens this balance of provision is seen as a constitutional danger. Incorporating the private HE sector therefore offered another means to build consensus.

The legislation that emerges from the committee hearings in the Senate (SB1304) and the House (HB5633), and the final Republic Act, adopts the framing of ‘universal access’ and ‘tertiary education’, in preference to ‘free tuition’ or ‘subsidies’. This emphasises that it is not necessary to identify particular beneficiary groups, because the act intends to achieve universal access. It also explicitly incorporates all forms of tertiary education, an expanded student loan system, and a fund to cover a range of non-tuition fee expenses for the poorest students (see below). This is a clear effort to assimilate all key initiatives under one umbrella, highlighting the legislative consensus around ‘distributive justice’, not by outlining specific distributive mechanisms, but by ensuring ‘universal access’. It should be noted here, however, that ‘universal access’ is taken to mean that access is not based on economic wealth; it does not mean that all students have a right to attend higher education regardless of their prior attainment (McCowan Citation2012).

Attention to procedural justice is evident in the very minimal eligibility requirements for students to access ‘free tuition’, which are: (1) not already having an undergraduate degree, (2) complying with admission and retention policies, and (3) completing the degree within the time of the prescribed programme (plus a year’s grace) (RA 10931). This open approach reduces the potential for unintended exclusions, while protecting academic standards through SUC admission and retention policies, as the change in titles in the final act indicates, where ‘universal access’ replaces ‘free higher education’, a clear signal of aspirations, but also a move away from the potentially contentious notion of ‘free higher education’ (De Gayardon Citation2019).

The introduction of the Tertiary Education Subsidy can also be understood through the lens of procedural justice. The subsidy supports students with the additional cost of fees in private HE, books, transportation, room and board, disability-related expenses, and professional licence or certification. Because the financial burden of HE extends far beyond fees themselves, into accommodation, transport and so on, particularly for SUCs which seek to keep fees as low as possible, free tuition alone would be inadequate to encourage participation amongst the poorest Filipinos: ‘partial financing (i.e. tuition fees alone) is problematic because only the richer households have the resources to finance the rest’ (Orbeta and Paqueo Citation2017). Students on the ‘Listahan 2.0’, a comprehensive national government database of poor families and their income status (Department of Social Welfare and Development, 2019), are to be prioritised. This includes indigenous peoples, those implicated in the peace process, namely the Muslim minority of Mindanao, farmers and ‘other disadvantaged groups’. This additional subsidy was introduced in the Committee stage of the final House bill (HB5633) and did not appear in earlier House or Senate bills. It appears therefore to be a response to critiques of the initial proposals (see for example FEF Citation2017), replacing the multiple proposals for scholarship programmes targeted to benefit these specific groups, including indigenous groups (HB578), ‘children of farmers and fisherfolk’ (HB290, 1590, 2984, 3193, 3852), ‘indigent senior citizens’ (HB3704), the children of people with disabilities (HB5127), and public school teachers and their children (HB3708, 3959, 5239, 5346). Thus, while aspects of recognition (Fraser Citation2008) of ‘disadvantaged’ groups are addressed in the final legislative texts, the primary framing is that of universal access, as a matter of ‘procedural’ justice. In Fraser’s (Citation2008) terms, this represents an explicit commitment to a politics of redistribution rather than recognition, as the sociocultural identity of marginalised groups is not explicitly identified in the final legislation.

Again, it is noticeable that the most vocal critics of the policy do not contradict the principles of distributive justice, but only the procedural dimensions:

Given the highly inequitable structure of Philippine society … the poor must be fully subsidized while those with the economic means to pay for their entire education many times over must share the cost of their education through the payment of tuition, differentiated by social class (CHED Citation2017, 1).

The Tertiary Education Subsidy addresses this critique with targeted aid and an expansion to the student loan programme. These developments in the legislative texts show that issues of procedural justice were resolved, after agreement on distribution. In the decision to rely on a national database compiled by a government agency, an appeal to objectivity in the evaluation of a student’s family circumstances is implicit. This decision also avoids imposing any further administrative burden on students to establish their eligibility: that burden is entirely upon the institution.

However, in the words of Kabataan Party representative Sarah Elago (Citation2017) ‘Contrary to our proposed legislation, this (the final legislation) does not aim to reverse the systemically ingrained neoliberal policies of privatisation and deregulation that turned education into a profitable, money-making endeavour.’ While the Universal Access legislation removes the requirement for students to share tuition costs and replaces it with state funding, it does so in keeping with the principles of neoliberalism and marketisation, not in rebellion against it, as the next section will illustrate.

Economic narratives

Both the rationales underpinned by notions of distributive and procedural justice also deploy nearly ubiquitous economic narratives, justifying the move in terms of a smart investment for human capital development (HB1942, HB3452, HB5581, SSB61, SB177, SB198, SB1220). Thus Sen Bam Aquino argues ‘A college education is not only a qualification that results in higher-paying jobs, but it is most importantly a means for the development of knowledge, innovation and social change in a nation. Supporting the growth of HE in the Philippines will serve to heighten the quality of our workforce so that we may partake more meaningfully in the global production of knowledge.’ (SB177). The budgetary feasibility is also a frequent rhetorical move, citing available budget surplus, precedent in terms of funding primary and secondary education, and potential sources of funding (HB1942, HB5581, SB198, SB61).

The knowledge economy concept, central to contemporary neo-liberal discourses, is explicit in several pieces of core legislation (HB5581, SB177, SB198). As Rep. LaRoque argues, the knowledge economy ‘is what higher education provides … allow(ing) a country to produce and train more engineers and scientists … contributing toward stimulating entrepreneurial activity and in turn help job creation’ (ibid. in SB198 Gatchalian). This is situated against historic expenditure in HE in comparable countries such as Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam, where the Philippines has spent less (SB1220). In the context of a globally competitive market for talent and skills, bearing in mind the Philippines’ notable emigration patterns in sectors such as healthcare, a systematic under-investment in the HE sector could lead to entrenching comparative national disadvantage. To establish a competitive advantage in high reward sectors such as science and technology, substantial investment in human capital is required (Özdoğan Özbal Citation2021).

Core legislation in the Philippines connects the language of national development to investing in human capital:

By providing free and quality tertiary education, the State invests on its citizens so that students coming from poor families will have the ability to move up the economic ladder. Upon entering the labor force, the educated students will be able to contribute more significantly to the economic goals of the country. (HB34520)

As expressed in the Philippine Development Plan, the country’s vision of inclusive growth and development entails sustained investment in human capital, particularly through the provision of quality basic education, competitive technical-vocational skills training, and relevant and responsive higher education. (SB61, ibid HB1942).

This notion of ‘inclusive growth’ (HB1942, 4902, 5581, SB198, 61) draws on shifts in development thinking, ensuring that economic growth is not merely aggregate, but is also appropriately distributed (Ranieri and Almeida Ramos Citation2013). Here we see again the importance of distributed justice informing the narratives. The Philippine Development Plan (NEDA Citation2013, 18) explains that inclusive growth ‘is sustained growth that creates jobs, draws the majority into the economic and social mainstream, and continuously reduces mass poverty’. The Development Plan has rhetorical power, as a guiding policy mandate. By invoking this power, these legislative proposals situate themselves within, rather than counter, the domain and logics of neoliberal economics. However, the Development Plan does not advocate universal access or large-scale tuition subsidy. Rather, it continues to emphasise basic education as the priority, with HE priorities focused on ‘rationalising’ the sector, making it more accountable, enhancing international accreditation, and improving the match between graduate skills and workforce requirements – by harnessing private sector resources. Similar arguments are made by the Asian Development Bank (Usui Citation2012), suggesting that inclusive national growth relies on ‘ a steady stream of qualified workers for high productivity services’, requiring substantial reforms in HE in the Philippines.

Inclusive or ‘pro-poor’ growth references notions of distributive justice but also employs the rhetoric of meritocracy. Poor students are frequently described as ‘deserving but underprivileged’ (HB2635, 5364, 5581, SB198), or as ‘financially disadvantaged but academically able’ (HB4902). Thus, Senator Aquino argues that ‘By unlocking this opportunity, poor and low-income families stand to benefit the most and will be empowered both economically and socially to be able to fully participate in our democratic nation’ (Aquino, SB177). Similarly, ‘It is time for us to institute a reform which will ensure that millions of deserving but underprivileged young men and women will be given their rightful opportunity to pursue a college degree’ (LaRoque, HB5581).

This phrasing emphasises the excluded students’ right to access HE, implicitly heading off potential arguments about lowering entry standards by stressing their academic potential. The final legislation states that it will: ‘(c) Give priority to students who are academically able and who come from poor families’ (RA10931). This is explicitly a move to remedy the injustice of opportunity, rather than outcome (Lynch Citation1995), at least in the initial legislation. However, there were no identified indicators related to this goal included in evaluation mechanisms. Rather it is taken for granted that introducing free tuition will have the desired ‘progressive’ effect.

This narrative evokes a sense of ‘the deserving poor’, speaking to a neo-liberal economist set of principles in which those with talent or ability should not be excluded but must have equality of opportunity to escape the circumstances of their upbringing. It is only through this mechanism of procedural justice that the apparent inequalities generate through neoliberalism can be ideologically justified. In other words, the unequal distribution is just because it rewards those who ‘deserve it’.

Discussion and implications

Through both content and thematic analysis, we identified a broad consensus on the meanings of distributive justice in the Philippine context. Legislators agreed that poor students were excluded by reasons of high fees and associated costs from accessing higher education. They related this to the Philippines Constitution to argue that this precluded achieving Filipino citizens’ constitutional rights to access high-quality education at all levels.

A number of themes were developed, including the promotion of access to ‘quality’ higher education. This is in line with the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals which now explicitly include, under SDG 4, that access to ‘quality’ education is now a core component of the goal and that policymakers should move beyond efforts just to provide access to education but also ensure that it is delivered to a high quality standard. The implicit concepts of ‘quality education’ are beyond the scope of this article to explore, but are certainly ripe for further analysis, being largely unproblematized in the legislative discourse. This article focuses instead on the factors that led to the provision of ‘free’ HE.

The procedural variety that existed in the single-authored early-stage, legislation became resolved in the final legislative text in the form of a universal tuition fee subsidy, encompassing both private and public higher education, expansion of the loan programme, and a mechanism to prioritise the poorest students. While perhaps unusual in the context of the free tuition debate, it is precisely this inclusion of the private sector that made the final legislation possible. In doing so, the final legislation establishes a procedural mechanism for both a universal tuition fee subsidy and a prioritisation of further support for the poorest. This resolves the initial conflicts in understandings around procedural justice, and redistributive justice while sustaining the consensus on distributive justice.

However, who was deserving of this access was found to be limited to those who were academically able or deserving but underprivileged. The narrative of meritocracy (Littler Citation2017), by limiting access to higher education to a smaller academic elite, makes the provision of universal tuition subsidies affordable. It also resolves the apparent ideological conflict between neoliberalism and distributive justice by proposing that it is just to provide access to higher education only for those who have earned it. Distributive justice in the context of the Philippines is understood to provide access and opportunities but not to guarantee outcomes, just as growth is intended to be ‘inclusive’ but not ‘equal’.

Finally, the deployment of the knowledge economy narratives which emphasise investment in higher education as an important angle for national economic development enables the framing of tuition fees subsidies as a fiscally prudent initiative. This anchors the move within the context of a global neo-liberal imaginary for HE, such that the core principles of universities in service to human capital and the consolidation of national competitive advantage are not challenged.

The consensus on the language of meritocracy has been a key framing tool to the passage of the bill in the Philippine context. It is possible that this framing on the ‘deserving poor’ has provided a focus greater than the ‘fuzzy’ purposes in a similar reform carried out in Chile (Bernasconi Citation2019). Although this study is not primarily comparative in approach, the Philippine case can contextualise how legislative processes in different countries such as Chile (De Gayardon and Bernasconi Citation2016) and Tanzania (Msigwa Citation2016) among others, affect how such a reform can be achieved. This is even more important given that these countries are less well-represented in the literature.

The overall message arising from this analysis is the importance of understanding the political context and legislative process around difficult but important reforms. Reformers and social justice activists (as in the Philippine case) who try to introduce free higher education tuition in marketised sectors governed by representative politics, would be well advised to use economic narratives and to bring important stakeholders onboard to build a policy consensus. The private HE sector is a particularly significant stakeholder in many developing countries, and the policy process should engage with it for both pragmatic and symbolic purposes.

Our analysis shows what kind of language and framings could be used to achieve this consensus, specifically the narratives of distributive justice deployed in the service of ‘economic growth’. A constitutional consensus on access to higher education as a universal right is underpinned by an implicit consensus that this is only fiscally prudent because of the small proportion of would-be students who will qualify for selective HE. This is justified with reference to the ‘deserving poor/ or the ‘academically’ able – categories which constitute their opposite: the ‘undeserving’ or ‘academically unable’, whom the sector and the state are not obligated to support.

It is the narrative of the meritocracy that justifies the neo-liberal state (Littler Citation2017). To sustain ideological support for the rising inequality fostered in market capitalist states, it is essential to subscribe to the ‘myth’ that those with higher incomes or social status have ‘earned’ them by virtue of their ‘hard work’ or ‘talent’. Yet social and cultural capital are intergenerational, and mediate access to and outcomes from higher education. In the example of the Philippines, the retention of selective entrance procedures in SUCs alongside the implementation of ‘universal access’ funding, and the residual narratives about ‘deserving’ students indicate the significance of the meritocracy myth. Such approaches to distributive justice are therefore affirmative of the existing social order, not radically transformative.

Universal access facilitates a meritocracy, as people will no longer be ‘unfairly excluded’ from higher education – only, by implication, fairly excluded. Consequently, graduates have ‘earned’ the additional benefits they acquire via human capital, as private goods (Marginson Citation2011). Further, through the concept of the knowledge economy, the financial outlay can be understood as a prudent investment in human capital, which fosters growth in high-income sectors, building a more ‘advanced/ developed society’. Economic growth, distributed according to ‘merit’ rather than a pre-existing advantage, generates more income for the state, justifying the de facto increased subsidy to higher education – although not in this language.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the value of using a methodology that clearly shows, through legislative texts, the process of consensus-building around the provision of free high education at public HE institutions in the Philippines. All legislators present at the bill's final hearing voted in favour. This remarkable outcome can be explained, we argue, on a pre-existing consensus around distributive justice and economic development in neoliberal Filipinos HE.

Our study’s focus on this legislative process differs from the approach taken by other studies such as those in economic and quantitative sociological fields which are concerned with the links between changes in tuition fees and participation rates in HE (see, amongst others, Sá Citation2014), mostly done in the context of wealthier nations with more developed HE systems (Lebeau et al. Citation2012; Ringe Citation2009). Our qualitative approach to understanding the logics behind a move towards large-scale state subsidy and away from cost-sharing approaches to funding HE demonstrates that shared understandings about social justice underpinned this successful legislation, an insight that can be explored and tested in other national contexts in future studies.

In the Philippines, HE is situated primarily as a mechanism to accomplish economic development; as such it needs to be accessible to the ‘most talented’ students, of whatever social background, since they will generate the most output in terms of job creation or transfer of resources. Tuition fees, by excluding access to HE by ‘deserving but underprivileged’ students, create an inefficiency, as well as an injustice. It is this reframing of distributive justice as compatible with neoliberalism that characterises the Philippine case.

Our study also shows how issues of procedure and recognition of marginal groups were finally resolved in the final Act. An undoubted limitation of a documentary approach adopted in the Filipino context, however, is that it does not reveal the backroom deals and off-book negotiations that result in finalised legislation. There is therefore scope for future empirical qualitative research in contexts exploring the implementation of similar approaches to ‘universal free tuition’ through ethnographic or interview focused approaches.

These explanations draw on our choice to analyse the totality of legislative texts around our chosen topic as well as our choice of perspectives on justice to explain areas of consensus (distribution) as well as contestation (procedure and recognition of marginal groups). Voices of dissent, such as those of the Kabataan Party (Elago Citation2017), did not significantly influence the final legislation. Private providers, on the other hand, were able to influence the legislation only when they could at least rhetorically engage in the project of ensuring ‘universal access’. In the end, issues of procedure and directed support to certain groups are resolved to result in shared conceptualisations of economic development and the role of education.

There are critiques and ongoing debates about the efficacy of this free tuition policy. Insofar as other countries might draw inspiration from the Philippine example, we identify several key enablers of this policy. The first is the economic growth leading to the budgetary capacity of the Philippine Government to pursue the passage of the Act. The second is the absence of a two-party system fostering deep political divides, and the presence of a broad consensus, fostered by a constitutional commitment, to a rights-based understanding of education. The third is the capacity of the legislative process to encompass and address the private HE sector, sustaining a commitment to a marketplace of HE providers, in conjunction with an aspiration to the provision of universal access. We would add the existence of the Listahan: a comprehensive list of families living in poverty, to enable further targeted support. Finally, the broad consensus on the role of HE as a private good in the neoliberal economic model, in conjunction with a shared understanding of national priorities for economic development.

Various studies use the social justice framework to explain engagement with the political and legislative processes (Besley and McComas Citation2005). Our analysis, by contrast, shows that despite higher education being a widely desired public good in human capital terms, the Philippine free tuition legislation was agreed upon only when money and administrative capacity permitted. This begs the question of sustainability. In the Philippines, such budgetary largesse also has to contribute to the building of new patronage structures. The long-term economic sustainability of this policy has yet to be demonstrated, and we suggest this is a useful case study for ongoing observation and analysis to inform global debates around social justice, and higher education funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A term widely used in UK higher education policy that refers to helping those from less represented backgrounds to enter HE.

2 The discrepancy between the UNESCO rate of enrolment and the Philippine Statistics Authority relates to the survey-based methodology of the latter, in contrast to the census-based methodology of the former.

References

- Aceron, J. 2009. “It’s the (non-) System, Stupid!: Explaining ‘mal-Development’of Parties in the Philippines.” In Reforming the Philippine Political Party System: Ideas and Initiatives, Debates and Dynamics, edited by M. Herberg, 5–22. Bonn: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung (FES).

- Bazeley, P., and K. Jackson, eds. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. London: SAGE publications limited.

- Bello, W., and J. Gershman. 1990. “Democratization and Stabilization in the Philippines.” Critical Sociology 17 (1): 35–56.

- Beltran, B. 2019. Education reform and the Philippine economy, Businessworld, 26 June 2019. Available at: https://www.bworldonline.com/education-reform-and-the-philippine-economy/ Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Bernasconi, A. 2019. “Free Tuition in Chile: A Policy in Foster Care.” International Higher Education 98: 8–10.

- Besley, J. C., and K. A. McComas. 2005. “Framing Justice: Using the Concept of Procedural Justice to Advance Political Communication Research.” Communication Theory 15 (4): 414–436.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597.