ABSTRACT

It has long been debated as to whether higher education (HE) is a site of social mobility that promotes meritocracy or social reproduction that creates and exacerbates inequalities in societies. In this paper, I will argue that HE, even when democratised and provided free to everyone, reproduces inequalities unless coupled with an inclusive sectoral design, an expansion of funding, and a wider strategy to reduce socio-economic inequalities. To do so, I studied the case of Syria, which has always claimed to have a meritocratic HE system that is designed to achieve equality in society by providing free HE for all since the 1970s. I analysed the database of the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) for 15 academic years from 2001 to 2015. This database included data on students’ access and graduation rate divided by the type of education (public, private, higher institutes, and technical institutes), level of education (undergraduate and postgraduate), gender (male and female), city, faculty, and specialisations. This analysis unpacked four types of inequalities, namely education type-based inequalities, specialisation-based inequalities, city-based inequalities, and gender-based inequalities. Finally, I show how gender dynamics and roles are changing in the HE sector as a result of the Syrian conflict.

1. HE and inequality

The debate around the role of education in society is a very old one amongst sociologists. Ibn Khaldun, the father of Arab sociology, in the fourteenth century Muqaddimah, discussed the role of education in the rise and fall of societies (Rosenthal Citation2005). In Western sociology, this debate around the role of education in society has been addressed by the work of functionalist sociologists such as Émile Durkheim (Durkheim Citation1956, Citation1997, Citation2002). In sociology, the concept of social stratification and its relationship with the social order is of fundamental importance (and debate). Functionalist thinkers perceive that societies embody both competitive and social solidarity elements. They tried to answer a fundamental question about how society can design an efficient and fair system of stratification that balances the competitive elements within it while at the same time maintaining social stability/coherence. Education was perceived to play this role (and others) by functioning as a meritocratic and achievement-based stratification system that selects and allocates people to roles in society based on their merit alone. In this way, people will be fairly sorted and progress (i.e. achieve social mobility) into social positions based on their capacity. This not only leads to maintaining social cohesion but also to achieving economic and social prosperity. However, structuralist sociologists, such as Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu Citation1977, Citation1986, Citation1998), perceive education as a tool which reproduces social stratification and the cultural hegemony of the elite. Bourdieu conceptualised HE as a ‘sorting machine that selects students according to an implicit social classification and reproduces the same students according to an explicit academic classification’ (Naidoo Citation2004, 459).

The latter argument that students’ socio-economic background has a lot of influence on HE access, decision, and attainment is documented globally by empirical research (Ball et al. Citation2002; Bukodi, Goldthorpe, and Zhao Citation2021; Bukodi and Goldthorpe Citation2013; Crawford and Greaves Citation2015; Reay, Crozier, and Clayton Citation2010). One major explanation is the influence of parental background on a student’s prospects. For example, Bukodi, Goldthorpe, and Zhao (Citation2021) found in the UK context that parental education, status, class, and income contribute heavily to a student’s attainment and transition to HE. Similar findings were reported in Norway (e.g Flemmen et al. Citation2017) where accessing and finishing education was found to be dependent on the ‘forms of capital’ which are the economic, social and cultural capital that students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds can access through their parents’ wealth and networks. In Australia, students of educated parents are three times more likely to have graduated from university than students of non-educated parents (Chesters and Watson Citation2013). Parents’ backgrounds and resources play an important role in the cost–benefit evaluation of accessing HE (Breen and Goldthorpe Citation1997). This is because many working-class students, even those who finish school and are qualified, exclude themselves from HE as they perceive it too ‘risky’ both financially and in terms of personal identity benefits (Ball et al. Citation2002). The researchers emphasised the inequality of ‘dealing with insecurity’ as a hidden barrier to accessing HE (69). Those who come from advantaged backgrounds do not experience this barrier as severely as those who come from disadvantaged ones (Ball et al. Citation2002; Breen and Goldthorpe Citation1997). Additionally, students from upper-class backgrounds feel pressured, inspired and supported by their parents to maintain their parents’ social position and avoid downward social mobility (Davies, Qiu, and Davies Citation2014). In addition to the family background, another explanation is that the ‘field’ of education itself is designed to fit the middle-class ‘habitus’ (tastes and attributes), which limits working-class individuals’ ability to enter the field and makes them feel out of place in HE, and as a result, struggle/drop out of education. Studies from the UK (e.g. Lee and Kramer Citation2013; Reay, Crozier, and Clayton Citation2010) showed how working-class students struggle to fit into these elite environments, shift between a nonelite home environment and an elite education setting, and maintain ties with their previous communities. Therefore, working-class children may be reluctant to pursue HE as this implies their eventual mobility away from their communities and class to a different one (Boudon Citation1974).

This inequality in education (e.g. access and attainment) caused by socio-economic background reflects on a person’s position in society as status positions in modern societies are assigned to a large degree based on education. To reduce the influence of socioeconomic background on people’s chances in education, there is a line of research and activism that extends from South America to Africa to the Far East, demanding that HE should be free (Bellei and Cabalin Citation2013; Cini Citation2019; Lomer and Lim Citation2022; Samuels Citation2013). However, a case study of Chile, Brazil, and Argentina (De Gayardon Citation2017) shows that, in reality, things are way more complicated. For example, the Chile policy of free higher education (gratuity) for secondary school graduates from families with lower income proved to be marginal in promoting social mobility (Espinoza et al. Citation2022). In fact, free HE policies could have a regressive effect when they are unconditional, as these policies could benefit more students from high-income backgrounds (Salmi and D’Addio Citation2021). This is because those from higher socio-economic backgrounds are more prepared to benefit from free HE. As a result, governments tend to use different strategies to remove financial barriers, such as fully or partially subsidised education, needs-based scholarships and grants, student loans, equity-linked financial incentives, and equity-related regulations (Salmi Citation2018). Furthermore, literature shows that there is a range of nonfinancial barriers that limit students’ ability to access HE, such as inadequate academic preparation, lack of knowledge on admission and access, competing family or cultural interests, and scarcity of support for academic and career planning (Salmi and Bassett Citation2014). Additionally, educational inequalities extend beyond socioeconomic background to include cultural, gender, and disability factors (Salmi and D’Addio Citation2021). Therefore, the literature shows that the most effective equity promotion policies are those that combine financial aid with measures to overcome non-financial obstacles (Salmi and Bassett Citation2014). Examples of these measures could be affirmative actions, reformed admission criteria, outreach and bridge programmes, and retention programmes (Salmi and Sursock Citation2018).

Literature shows that educational inequalities are highly geographically and culturally constituted. However, in the Syrian context, no study has tried to unpack the mechanisms and factors by which education reproduces inequalities. Syria has followed for over thirty years a socialist model of HE that is free to everyone regardless of class. While it is an important first step, free HE is not a magic wand which solves inequality of access or the influence of socioeconomic backgrounds on education attainments. As will be shown in data analysis, the case of Syria shows the importance of having an inclusive sectoral design, an expansion of funding for public HE, and a wider strategy to reduce socioeconomic inequalities. Otherwise, HE will continue to exacerbate inequalities.

2. HE in Syria and inequality

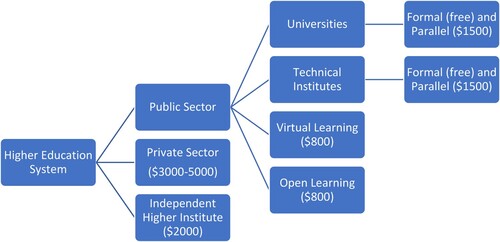

The Syrian HE sector has gone through several big governance shifts since its establishment in 1918. At the start of the 1960s, when the socialist parties took control over Syria's political and social life, the sector was co-opted to serve a socialist political agenda. Part of this agenda was to achieve internal legitimacy by making HE free for everyone, only provided by public universities (Tozan, Citation2023a). This has increased access by almost 10-fold (Sankar Citation2000). This policy made Syrians, to a large degree, perceive HE as a level playing field for two reasons. Firstly, there was one main route to access HE, which is the single-track policy that sorts students into HE specialisations and disciplines based only on the student scores in the Baccalaureate (Bakalūriya), the national exam at the end of secondary school (Buckner Citation2013). Based on their baccalaureate grade, students get offered several specialisation options to study HE for free. Secondly, the socio-economic background was perceived to have a limited impact on access as there are only free public universities. This sector design created a sense of meritocracy amongst the Syrian population (Buckner Citation2013). However, in early 2000, Syria moved into a ‘social market economy’. It followed a kind of neoliberal reform that aimed at privatising HE and supplying the new economy with the needed human capital (Buckner Citation2013; Tozan, Citation2023a). Private universities and academic institutes were allowed to open, and several paid tracks in the public sector were established ().

Figure 1. The different tracks in higher education and their annual fees.

Note: These fees are estimates from 2010. The currency is US Dollar.

As the figure shows, students could access the public sector and acquire a university degree, technical institute degree, virtual learning degree, or open learning degree. Some of these tracks are free of charge, while others are not. Under universities and technical institutes in the public sector, there are two sub-tracks: formal (Niẓāmy) and parallel (Mwaāẓy). Students in the formal and parallel tracks receive the same education as they study the same course and sit in the same class. However, formal learning is a free public track for those who have achieved enough school grades in the single-track policy (Bakalūriya) to study the course of their interest. In contrast, parallel learning is a paid public track for those who have not achieved enough school grades in the single-track policy (Bakalūriya) to study the course of their interest. For example, studying medicine in the free public track requires scoring around 235/240 marks in the Bakalūriya, but if a student scores 225/240, they can still access medicine in the public sector (parallel learning) by paying tuition fees. Additionally, students can access the public sector through the virtual learning track (online degrees) and the open learning track (weekend courses). Access to virtual and open learning degrees depends mainly on a student’s ability to pay the fees.

In addition to the public sector, students can access the private sector, including around 20 private universities that charge high annual fees. Lastly, students can access The Higher Institute of Business Administration, which is an independent higher institute that offers UG and PG courses for high annual fees and operates as a public-private institution.

Where 100% of students were enrolled in free higher education before the 2000 reform, this number dropped to 53% in 2010 as 47% of all HE students were enrolled in paid tracks (parallel, private, virtual, open, and higher institute) (Ministry of Higher Education Citationn.d.).Footnote1 Although all Syrians are eligible for free public HE according to the 1973 constitution, almost half of the students enrol in paid tracks to seek better education through private universities or to study their courses of interest, which they might not be eligible to study these courses in the free public tracks based on their school grades. Therefore, the 2000 reform has not only changed the funding architecture of the sector but also contributed to the already existing inequalities in society. There are very few attempts in the literature to unpack inequalities in higher education in Syria. A UNDP report found that education is the single characteristic with the strongest correlation to poverty risk in Syria (El Laithy and Abu-Ismail Citation2005). Poverty has perpetuated a vicious cycle of low education. In 2004, the report estimated that more than 18 per cent of the poor population was illiterate, and less than one per cent of the poor had a university education. The report also found a huge discrepancy in education attainment between rural and urban areas. Buckner (Citation2013) and Buckner and Saba (Citation2010) examined youth perceptions of higher education and analysed nationwide surveys of Syrian youth to investigate educational and labour market conditions. They found that the neo-liberal reform in 2000 ended the sense of meritocracy and created inequalities and grievances in society as accessing HE became dependent on family wealth as much as on the baccalaureate grade. The different tracks to education created resentment among students who felt the financial capacity was muddled with the meritocracy nature of the sector (Buckner, Citation2013). Furthermore, they found that class, gender and regional background significantly impact educational opportunities. Recent publications (e.g. Tozan, Citation2023b; Dillabough et al. Citation2018; Citation2019) have shed light on the impact of the Syrian conflict on the current inequalities in HE. They reported how intensely politicised HE and political warfare have excluded students who do not align with the Syrian government’s political agenda and increased access inequalities based on loyalty to the government as a way to privilege its supporters.

3. Methodology

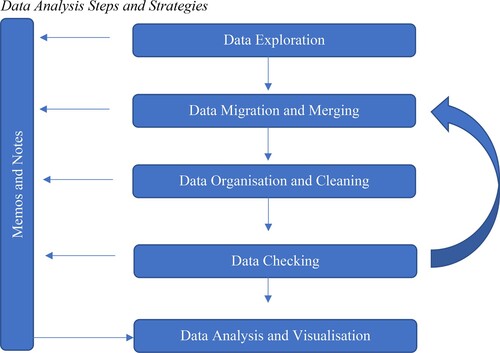

Previous studies argued that future research on Syrian youth must disaggregate findings by background and demographic characteristics as the aggregated data hides certain inequalities (Buckner and Saba Citation2010). This research will build on this suggestion by conducting archival analysis for all databases available on Syria’s MoHE website. When analysing secondary data, I followed strategies () adopted by Jones and Goldring (Citation2022) and Williams, Wiggins, and Vogt (Citation2021). However, I felt the need to add extra steps/strategies to solidify my analysis.

In the first step, data exploration, I tried to make sense of the data by screening the 125 MS Excel sheets published by the MoHE, which makes up what I refer to in this research as the database. This database covers the years from 2001 to 2015 and includes data on students’ access and graduation rate divided by the type of education (public, private, higher institutes, and technical institutes), level of education (undergraduate and postgraduate), gender (male and female), city, faculty, and specialisations. Furthermore, this database included student-teacher ratios and the gender of the academic workforce in the Syrian HE. After I explored the data, I started the process of data migration (second step) which included merging the 125 Excel sheets into one master Excel file. The database was not organised enough to be analysed immediately. The reporting differs year by year and file by file. For example, the names of specialisations, faculties, universities, cities, degrees, and education types have all been reported differently. Therefore, I had to organise and clean the data (third step) to be able to run an accurate analysis. In the fourth step, data checking, I implemented several strategies to check the accuracy of the data by re-checking the data migration and organisation steps and filling some of the gaps in the data by taking the missing numbers from different sheets. In the last step, data analysis, visualising, and interpretation, I used descriptive statistics which allowed me to describe, visualise and summarise the key features of the data. In particular, I used frequencies, measures of central tendency (e.g. mean), and measures of desperation (e.g. standard deviation). Although other types of analysis could be used such as inferential analysis, this paper was limited to the use of descriptive statistics for two main reasons. Firstly, the database includes variables that are measured on an interval and a ratio scale (e.g. number of students, graduates, teachers) and descriptive statistics, mainly arithmetic means, could be sufficient to unpack the data (Goos Citation2015). Secondly, descriptive statistics is an area of expertise that the researcher is more confident of. In the last stage, interpretation of the data, I consulted the literature published on HE in the context I am researching to explain the findings.

4. Findings

In this section, I present the findings of this paper. Looking at inequalities in HE just from the lens of access provides a very narrow view of inequalities. Therefore, I present these inequalities below divided into four different themes.

4.1. Education track-based inequalities

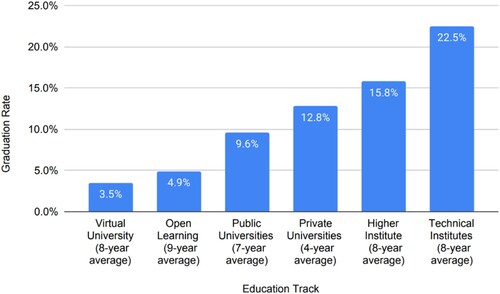

below presents the UG studies graduation rate for the different tracks into HE and shows stark unequal graduation rates between the different tracks.

Figure 3. UG studies average graduation rate per track. Source: aggregated from the MoHE database from the year 2005 to 2015.

Although this paper is mainly interested in showing how public free education could still perpetuate inequalities in societies, comparing private and public free education could tell part of the story of the wider inequalities in the sector. We can infer from the relatively very high fees of the private universities and higher institutes that students accessing these tracks come from high socioeconomic backgrounds. Therefore, this chart helps understand how socioeconomic background impacts graduation rates between public and private universities. Furthermore, below compares the student-teacher ratio for three academic years between the private and public sectors.Footnote2 The table shows that, in 2008, the public sector had a student-teacher ratio four times higher than the private sector. This means that classes are four times more crowded. In 2009 and 2010, the gap decreased, and the ratio of the public sector became three times higher than the private sector. Yet, this is still a big difference and it has been reflected in the support students experience in class and their learning outcomes (Dillabough et al. Citation2019). Additionally, private universities were able to attract the best lecturers in Syria because of their financial capacity and better resources and infrastructure (Dillabough et al. Citation2019). Lastly, the inequality between private and public universities is not limited to just the student-teacher ratio but also to the quality of equipment and infrastructure (Dillabough et al. Citation2019).

Table 1. Student-teacher ratio for the public and private sectorTable Footnotea.

Aside from the private/public inequality, it is difficult to explain why there is this huge discrepancy in the graduation rate in the other tracks. This will require a nuanced and comprehensive exploration of the multiple potential variables at play in the different modes of higher education. Furthermore, we do not know the socioeconomic background of people accessing the other tracks, therefore, there is not enough data to draw accurate conclusions on inequalities. However, open learning is widely considered to be a worse education than other types and some students perceive it as a ‘moneymaking scheme for the government that does not offer the desired (historically promised) level of job security’ (Buckner Citation2013, 451). Students reported the lack of online libraries, the outdated curriculums, and the lack of qualified lectures as the main weaknesses in the open learning track (Naiem Zeeb Citation2023). Similar findings were reported on virtual learning where students suffer from isolation and lack of support to finish their degrees as courses are completely virtual (Al-Abdullah Citation2010). The low quality of courses in open learning and virtual learning, amongst other factors, could have impacted the graduation rate. The Ministry of Higher Education Technical Institutes on the other hand only offer students a two-year degree, and the top couple of hundreds of students in each specialisation can progress to study towards a bachelor’s degree in public universities. The short length of the degree and this incentive scheme have potentially led to a high graduation rate.

4.2. Specialisation-based inequality

The database of MoHE has almost complete data for the public universities’ UG graduation rates per specialisation for 10 academic years.Footnote3 The average graduation rate across all specialisations is 10.7% per year and the standard deviation is 2.4%. Looking at how the different specialisation graduation rates are spread around the average helps us to unpack inequalities amongst specialisations. below presents the individual specialisation graduation rate and their distance from the average graduation rate.

Table 2. Individual courses graduation rates.

The above table helps us to observe that there is a huge discrepancy in the graduation rate per specialisation. For example, the faculties of Tourism, Islamic Law, and Literature and Humanities have less than an 8% graduation rate, whereas the faculties of Pharmacy and Dentistry have above 15% graduation rate. That means students who study the first set of courses have less than half the chance to graduate than those who study the second set of courses. However, similar to the analysis in the previous section, we cannot draw a conclusion on inequalities from this data as we do not know the socioeconomic background of the people accessing these specialisations. Nevertheless, looking further at the MoHE database could help us understand how the HE policies could disadvantage students based on their choice of education. below puts together three pieces of information for 24 faculties: 15-year average student/teacher ratio, 15-year average student/ internationally trained teacher ratio, and 10-year average graduation rate. The student/teacher ratio refers to how many students there are per teacher whereas the internationally trained teacher ratio refers to how many students are there per teacher who is trained (finished PhD) abroad to gain high-standard skills and knowledge.

Table 3. Students/teacher Ratios for UG Studies (2001–2015).

As the table above shows, faculties have a very unequal student/teacher ratio. Some faculties have an extremely high student/teacher ratio reaching over 100 students per teacher such as the Literature and Humanities and Law faculties, while others have a very small ratio of fewer than 15 students per teacher such as the Medicine and Petrochemical Engineering faculties. A similar observation can be seen for the student/internationally trained teacher ratio. The government sends one teacher aboard at the Faculty of Law for every 1614 students whereas it sends one teacher for every 134 students at the Faculty of Arts.

Cross-investigating the student/teacher ratios and the graduation rate could explain how HE policies could contribute to the specialisation-based inequalities. Surprisingly, 9 faculties out of 12 (those at the top of the table) which have the worst student-teacher ratio have a graduation rate of below average. Even more, 11 faculties out of the 12 (those at the bottom of the table) that have the best student/teacher ratio have a graduation rate of average or above average. Additionally, the three faculties that have the worst student-teacher ratios (the first three in the table) are the same ones that have the worst graduation rates.

4.3. City-based inequalities

Previous studies that counted on qualitative data have documented students’ feelings and perceptions of city-based inequalities (Buckner Citation2013; Dillabough et al. Citation2019). This paper complements this argument using quantitative data. To unpack city-based inequalities, it is important to present first the 14 cities (governorates) of Syria and the percentage of the Syrian population per city. There are no figures on the Syrian population per city published every year. However, the Central Bureau of Statistics conducted a national screening in 2004 and 2014 (Central Bureau of Statistics-Syria Citation2012, Citation2015). The average of these two years will be used in my analysis in this section. The database of the MoHE contains complete data for city-based access to public universities from the academic year 2008/2009 to 2012/2013. Analysing the database helps unpack two types of city-based inequalities, namely access to the sector and access to academic specialisations.

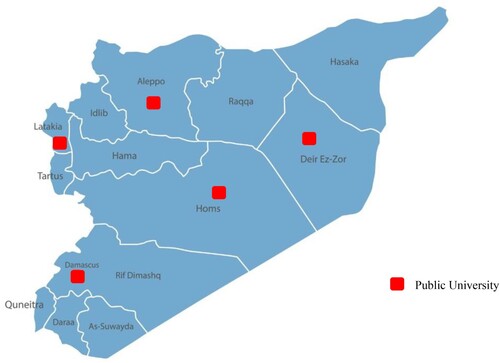

Although Syria has 14 cities, for the period of the analysis (2008–2013) Syria had only 5 public universities in 5 cities: Damascus University, Aleppo University, al-Baʿth University in the city of Homs, Tishreīn University in the city of Latakia, and al-Furāt University in the city of Deir-ez-Zor (). These five universities have small branches/centres in all Syrian cities that offer limited course options. For example, Damascus University has branches in the cities of al-Sweida, Daraa, and al-Qunetira. Similarly, The University of Aleppo has branches in the city of Idleb. The same goes for the other three universities. The logic behind designing the sector in this way is that each university is expected to serve a cluster of cities. This logic has persisted since the 70s when Syria had only four universities (Damascus, Aleppo, al-Baʿth, and Tishreīn) until around 2005 when new public universities started to open in more cities. This design of the HE system neglected some cities in Syria, leaving them without a proper HE system (Dillabough et al. Citation2019) which created city-based inequalities explained below.

below shows the percentage of students accessing the UG and PG public HE based on which city they come from. One way to unpack city-based inequalities is to analyse the representation of students in the sector. For example, Damascus’s population is 8.75% of Syria’s population, and arguably, a fair representation means students from Damascus should be around 8.75% of the total students accessing HE. The database provides data on the demographic background of students, mainly which city students come from (based on their civil registry). This helps understand the city background of those accessing the sector. The numbers underlined are where there is over-representation (the percentage of people accessing the sector is higher than their percentage of the Syrian population).

Table 4. A comparison between city-based population and city-based access to HE (2009–2012).

The above table shows that some cities are constantly overrepresented while others are constantly underrepresented. Two reasons could partially explain these inequalities: the design of the sector and the socio-economic background of students. Having one big university in just some cities gives an advantage to those students who live in these cities. This is because they do not experience the added financial and mental pressure that students from other cities have to access education such as paying for accommodation, living away from home, and paying for travel to see their families. Therefore, a lot of students from cities where there is no university might face more barriers in accessing HE, which impacts their academic, professional, and personal chances and choices. That could explain why cities like Damascus, Homs, and Latakia (where there is a university) are constantly overrepresented in HE, whereas students from Hama, al-Hasakeh, and al-Rakka (where there is no university) are constantly underrepresented.

Aleppo is a unique case. As a city with a university, it is expected to have high representation according to the previous logic, yet numbers show that it is constantly unrepresented. Similarly, Rural Damascus surrounds the governorate of Damascus and accessing universities does not require a big proportion of rural Damascus students to move out from their family homes and undergo the financial and mental pressure involved in accessing higher education. Yet, rural Damascus is severely underrepresented. These unexpected findings could be explained by the fact that Aleppo is the industrial capital of Syria, and manufacturing is the core of Aleppo’s economy. Manufacturing jobs do not usually require an HE degree which potentially encourages young people to not view HE as a needed investment. The same can be said of Rural Damascus which is considered the industrial hub of Southern Syria. Furthermore, Rural Damascus has a lower socioeconomic background than students from Damascus, and Aleppo has a very large rural area as well. In the Syrian context, participation in education from rural areas still falls behind urban areas for multiple reasons including poverty and the prevalence of informal housing zones with very poor conditions (Buckner and Saba Citation2010; Maziak et al. Citation2005; Smits and Huisman Citation2013). The rural areas are located tens of miles away from the university which disadvantages a lot of students who cannot afford the daily travel to the university and who need to prioritise having work and supporting family members over getting a degree.

Cities like Daraa and al-Sweida, although they do not have a public university, are constantly overrepresented in accessing HE. This could potentially be explained by the fact that these two cities have historically high migrant populations and channelling resources/remittances from the diaspora potentially helps these communities to access HE. For example, acquiring financial resources from the diaspora helps students to move to the nearest city where there is a public university (e.g. Damascus) or commute daily (around 20–40 miles).

Looking further at the city-based inequalities helps find inequality in access based on the level of study (UG or PG). This is also potentially a result of the sector design. As mentioned earlier, universities have small branches in other cities to accommodate the population of the cities that do not have a university. Those branches offer limited options for PG degrees. For example, the branches in the cities of Idleb, al-Hasakeh, and al-Rakka do not offer PG studies at all. As above shows, this has resulted in a sharp decrease in the representation of PG students from these cities. This further supports the argument that not having a university that offers all levels of studies in all cities hinders students from disadvantaged cities from accessing HE.

In addition to inequality of access to HE, city-based inequalities extend to include inequalities in access to the different specialisations and faculties that HE offers. This is also a result of the sector design that not all faculties or specialisations exist in all universities or branches. below shows how some faculties and courses are distributed across cities and how that led to a huge overrepresentation of students from the cities where the courses are being taught.

Table 5. Faculties distribution across cities and access representation (2008–2013).

Media UG studies, for example, are being taught only in Damascus. Although Damascus’ population out of the Syrian population is only 8.75%, students from Damascus represent 23.9% of the total number of media students. This is almost three times their percentage of the total population. A similar situation extends to all courses mentioned above. This huge overrepresentation of the students in certain courses comes at the expense of students from cities who cannot access these courses and faculties because they are not being taught in their cities. This pattern of unequal access to specialisations extends to a lot of disciplines not added above (e.g. Pharmacy, Dentistry, Medicine, Arts, IT, Mechanical Engineering, and Architecture). In all of these specialisations, students in the cities where the course is being taught have an advantage in access over students from other cities.

One of the very few exceptions to this pattern is, for example, the Political Science course. Although it exists only in Damascus, students from this city are not overrepresented in the course. This could be explained by the fact that engaging in political studies in Syria does not attract students from the big cities such as Damascus and Aleppo but rather attracts students from cities such as Homs, Hama, Latakia, and Tartous where there are concentrations of minorities. Since the 1970s, the political system has been governed disproportionately by the religious minorities in Syria. This could explain why people from these minorities gravitate more to the Political Science course.

4.4. Gender-based inequalities

Officials in the Syrian HE sector have always celebrated the progress that they have achieved, claiming to eliminate gender-based inequality in the sector by achieving near parity in the enrolment rate (Sankar Citation2000). Although there has indeed been noticeable progress, this claim does not stand under scrutiny as it hides gender inequalities across certain groups of the population (Kabbani and Salloum Citation2011). This section will try to unpack these hidden gender inequalities.

below presents the percentage of the total numbers of females and males accessing and graduating from the sector per track (public, private, open learning, etc) and the level of study (UG and PG). The first observation is that, although there is no gender gap overall across the sector, other than in UG public universities, gaps exist in all other tracks. Also, the higher the level of education (Master, PhD, etc), the wider the gap.

Table 6. Percentage of total numbers of females and males accessing and graduating from HE.

It is difficult to accurately explain why these gaps exist without having qualitative data to back up this analysis. However, a careful explanation can still be provided. In virtual learning, the gap might be a result of the type of courses offered and mode of delivery, which might not be preferred by female students in Syria. The virtual university has only three faculties: Telecommunication and Information, Business, and Social Science (Law and Media). As will be shown in the next section, these courses are male-dominant (except media). Whether because of social conditioning or the nature and environment of these male-dominated disciplines/industries, female students seem to avoid them. Also, in a society where not all women have full freedom of movement, virtual learning might not attract female students as much as in-person courses. The latter might give women more freedom to explore the outside world. As for the low female representation in the private sector, this could be due to the division of gender roles in the Syrian society that assigns men the breadwinner role (Buckner Citation2013). This could influence and justify families’ decision to invest in males’ education by sending them to private universities. When it comes to PG studies in public universities and higher institutions, the gender gap is also high. This could also be due to the division of gender roles. Accessing PG studies is mainly used as a strategy to advance in the labour market and so help men become breadwinners. However, this could also be because enrolling in HE is a strategy a lot of males follow to delay military conscription (Dillabough et al. Citation2019). In the Syrian conscription law, males should join the military at around the age of 18 when they finish school. However, they can delay joining the military service as long as they are studying for a HE degree.Footnote4

Another observation from the table above is that females’ graduation percentage is higher than their access percentage in all tracks and on all levels. That means females’ graduation rate is higher than males in all tracks after factoring in the access rate. One potential explanation is that failing HE is a strategy males follow to delay military conscription (Dillabough et al. Citation2019). Many times, male students fail their courses on purpose to avoid military service, giving them time to sort out their next move after finishing HE – usually leaving the country.

A third observation from analysing the database is that, although the gender gap still exists in the HE sector, the gap is closing in almost all tracks and at all education levels. below compares the females’ access percentage rate across several tracks into HE between three academic years. Year one is the oldest in the available database, year two is the conflict year 2010/2011, and year three is the latest year available in the database. The table shows that, although the gap was gradually closing before the Syrian conflict between year one and year two, the pace of closure accelerated noticeably after the conflict in several tracks. In one track, UG public universities, the percentage of female students accessing the sector reached 55% in 2015. This is potentially due to the conflict that disproportionally affected males and decreased their access rate to HE by pushing them into fighting, prison, exile, or migration.

Table 7. A comparison of females’ access rate in HE.

Looking further into the MoHE database helped spot further gender-based inequalities, namely access to academic specialisations. below shows the total access percentage for different specialisations in both UG and PG studies for 15 years.Footnote5 The table divides courses into three categories: courses dominated by male students (60% and above), courses dominated by female students (60% and above), and courses dominated by neither.

Table 8. Total access percentage of male and female students in UG and PG specialisations (2001–2015).

Again, it is difficult to explain these inequalities without having further qualitative data. In the Syrian context, these inequalities could be a result of several factors such as females’ preferences, family, peer, and social pressure, social conditioning and gender roles, the environment of these industries/academic disciplines, and the location of faculties/universities where these courses are being taught.

Lastly, the MoHE database also shows that gender-based inequalities extend beyond females’ access to certain tracks and reach female academic representation in the sector. below shows the percentage of females and males occupying teaching and technical/administrative positions in the HE sector. The table presents the average for 14 academic years and, similar to the above, it also compares three separate academic years (2001, 2010 and 2015). The underlined figures are the ones that will be discussed next.

Table 9. Percentage of females and males in the HE labour force.

There are two observations about gender-based inequalities in the HE labour force from this table. Firstly, there is huge inequality in occupying teaching positions. The 14-year average shows that female teachers are less than 25% of the total teachers in the sector. However, when it comes to technical/administrative jobs, females occupy more jobs than males (57%). This creates a hierarchy in the sector where males dominate the esteemed and powerful positions. The second observation is that the gap is closing fast. In 2001, female lecturers represented only 18%, whereas in 2015 they represented 32%. Similarly, females’ percentage of the total workforce was 24% in 2001 whereas they constituted 41% in 2015. This is also potentially due to the war dynamics that depleted the male human capital and changed the gender dynamics in the labour market and wider society. It is quite common for women to become the breadwinners in conflict and post-conflict contexts in the absence, death, or migration of males (Petesch Citation2017). This becomes clear in the HE sector when we look at the gender-based progress before and after the conflict started. For example, in 10 years from 2001 until 2010 (the year before the conflict), the female teachers’ percentage increased by 6 points from 18% in 2001 to 24% in 2010. However, in just 5 years after the conflict started in 2010, female teachers’ percentage increased by 8 points from 24% in 2010 to 32% in 2015.

Furthermore, the inequality in female academic representation in the sector extends to include inequalities in the number of internationally trained academics/scholarship recipients. below shows the total percentage of female and male students sent abroad via scholarships in 14 academic years to study towards a PhD degree. Similar to the above logic, it also compared three separate academic years (2001, 2009 and 2015) and found similar observations. The gap is closing and has accelerated after the conflict started in 2011. The 14-year average shows inequality in the total number of male and female students sent abroad. However, the gap closed in 2012 and started widening again towards the females’ side, reaching 54% in 2015. This is potentially due to the same reason mentioned above about the war dynamics and consequences that changed the gender roles in Syrian society.

Table 10. Percentage of male/female students sent abroad via scholarships to study towards Ph.D.

5. Discussion

In modern societies, status is often assigned based on education. Sociologists have long argued that HE operates as an ‘allocator’ that ‘legitimately classifies and authoritatively allocates individuals to positions in society’ (Meyer Citation1977, 59). Furthermore, sociologists argued and empirically showed that one’s socioeconomic background greatly impacts achievements, including education attainment (Duncan Citation1972). That means the allocation of people to social positions in modern society is strongly linked to their existing socioeconomic background.

The case of Syria is a very good example of how the HE sector, even when it is free for everyone, contributes to social inequalities such as education track-based, specialisation-based, city-based, and gender-based inequalities. Cross-cutting reasons for how free HE contributed to these inequalities are the absence of inclusive sectoral design, an expansion of funding, and a wider strategy to reduce socioeconomic inequalities.

Firstly, an inclusive HE design in Syria raises the quality of all HE tracks and extends HE (including specialisations and levels of study) to all cities in Syria. The different tracks into HE each have a different quality of learning, infrastructure, curricula, and student-staff ratio. In the Syrian context, this not only impacts students’ learning experience and graduation rate but also their access to economic opportunities and social positions. For example, the unemployment rate for technical institute graduates in Syria is almost double that of university graduates (Kabbani and Salloum Citation2011). Furthermore, the wages that technical institute graduates earn are less than that of university graduates (Kabbani and Salloum Citation2011). Looking at other contexts, such as Brazil, where HE is provided for free, allows us to build a similar understanding. Although free vocational higher education could be less socioeconomically selective than academic institutions and, therefore, widen the participation of students from low socio-economic classes, low-quality vocational education impacted people’s access to economic opportunities and social positions (Mont’Alvão Citation2015). Therefore, the mere offering of free HE does not lead by default to closing the inequality gap, especially when there is a wide gap in the quality of the different HE tracks. Moreover, the distribution of universities and specialisations in just a few cities made HE inaccessible to the most marginalised and remote cities. It blocked students from accessing universities and specialisations of their choice. Soares and de Oliveira (Citation2022) found similar findings in Brazil when unequal HE expansion occurred between the different geographical locations, leading to negative repercussions on the equality of access and outcome. Findings from Romania also show that the expansion of HE initially led to an increasing urban-rural divide (Voicu and Vasile Citation2010). This is mainly because students from low socio-economic backgrounds and women, in particular, suffered the most from such an unequal design as they are less able to travel and live in another city to pursue HE, whether because of cultural and/or financial barriers. All of the previous are flaws in the sector’s design which could have been mitigated by having a more inclusive HE sectoral design that makes HE accessible to all geographies.

The second way in which free HE in Syria exacerbated inequalities is when the expansion of HE was not coupled with an adequate expansion in funding (Kabbani and Salloum Citation2011). This led to an increase in enrolment rates in public universities at the expense of quality. Public university students suffered from a high student-teacher ratio rate (in some cases 140 students per teacher) and poor infrastructure compared to the low student-teacher ratio (around 20 students per teacher) and good infrastructure in private universities. Furthermore, not funding the public universities enough led qualified lecturers to prefer teaching at private universities. This widened the inequality between the public and private HE institutions as students with the financial capacity to access private HE learn from the most qualified teachers in Syria and get the best knowledge available. Syria experienced an increase in teachers’ salaries after the 2001 reform. This has helped to limit the internal brain drain but did not tackle the high private-public discrepancies. Therefore, increasing public university funding should enable a wider strategy that improves the quality of teaching, learning and research.

Thirdly, the inequality in HE in Syria is not just a result of a system design or lack of funding but also a result of wider gender, class, economic and regional inequalities (Buckner Citation2013; Buckner and Saba Citation2010; Kabbani and Salloum Citation2011). Similar findings can be perceived in Brazil and Argentina where education is also provided for free (Pla et al. Citation2021). Simply having free HE does not tackle the wider socio-economic inequalities that are limiting people’s chances in HE. Thinking that free HE will lead to equality in society assumes that everyone in society has an equal capacity to access education. This line of arguing ignores how those with high socio-economic backgrounds have better chances to access HE. For example, accessing better primary and secondary education, having private tutors at home, and not worrying about supporting family are factors that advantage some people and limit others in their access to HE. Salmi and D’Addio (Citation2021) argue that free HE policies could have a regressive effect when they are unconditional, as these policies could benefit more students from high-income backgrounds who are more prepared to benefit from free HE. This is evident in the Syrian context. Cities with high socioeconomic status, such as the capital, Damascus, have a relatively very high access rate to HE in general and top specialisations in particular. On the other hand, less privileged areas such as Rural Damascus have a relatively very low access rate. Rural/urban inequalities still prevail heavily in the Syrian context (David and Marouani Citation2012). Therefore, education policies in the Syrian context should be designed based on a deep understanding of where the ‘disparities characterizing higher education come from and which policies are more effective in reducing inequality at that level in the education ladder’ (Salmi and D’Addio Citation2021, 67).

Furthermore, the policies should extend beyond the monetary interventions to include non-monetary interventions that tackle the cultural and other barriers that limit students from accessing HE (Salmi and D’Addio Citation2021). This is particularly important for tackling gender-based inequalities. Assuming that free HE will eliminate gender-based inequality, ignore the cultural and structural barriers facing females in accessing HE. Nevertheless, non-monetary interventions are almost absent in the government’s strategy to widen access and reach marginalised communities and disadvantaged groups in Syria. Examples from several contexts show that gender-based inequalities, although closed on the undergraduate level, persist at postgraduate and university workforce levels. Similar to Syria, HE expansion policies in Iran reversed the gender gap in access to HE, yet female representation in postgraduate studies still lags behind (Mehran, Citation2009). This, in turn, leads to unequal representation in the HE workforce, decision-making, planning and policymaking, as those who work on this level require postgraduate education.

The MoHE database has helped us unpack these inequalities’ impact on the individual level (graduation rate, access to the sector and specialisations, student/teacher ratio, etc). However, the impact of these inequalities is highly likely to extend to the social and economic structure. As theorised by Meyer (Citation1977), ‘modern educational systems involve large-scale public classification systems, defining new roles and statuses for both elites and members […] and transforming society by creating new classes of personnel with new types of authoritative knowledge’ (56). The inequalities caused by HE potentially created or further exacerbated unequal development between regions, cities and genders and widened the social and economic distance between rural and urban areas. Future research could attempt to link this paper’s findings with the social and economic development of regions and rural/urban areas in Syria. Furthermore, future research can try to unpack other inequalities that this database could not unpack, such as disability and religion-based inequality.

6. Conclusion

This paper argued that HE, if not coupled with an inclusive sectoral design, an expansion of funding, and a wider strategy to reduce socioeconomic inequalities, will continue to be a site of social reproduction that creates and exacerbates inequalities in societies, even if it is provided for free. This conclusion was reached after examining the case of Syria, which, for over thirty years, has followed a socialist model of HE that is free to everyone regardless of class. The paper analysed the database of the Syrian Ministry of Higher Education for 15 academic years from 2001 to 2015. This database included data on students’ access and graduation rate divided by the type of education (public, private, higher institutes, and technical institutes), level of education (undergraduate and postgraduate), gender (male and female), city, faculty, and specialisations. Furthermore, this database included student-teacher ratios and the gender of the academic workforce in the Syrian HE. Following a five-stage descriptive statistical analysis (data exploration, migration and merging, organisation and cleaning, checking, and analysis and visualisation), this research has unpacked four types of inequalities: provision mode-based inequalities, specialisation-based inequalities, city-based inequalities, and gender-based inequalities. These inequalities manifest themselves in inequality of access to HE and specialisations, inequality of graduation, and inequality of experience (e.g. teacher-student ratio). In particular for gender, the inequality manifests itself in unequal occupation of teaching positions. Beyond the empirical account of inequalities in the Syrian HE, this paper adds to the literature on how the Syrian conflict changed the gender dynamics and roles in HE by starting to reverse the gender gap in students’ access, teaching positions, and scholarship recipients.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Dr Basma Hajir, Dr Zeina Al Azmeh, Dr Tamer Said and Professor Ricardo Sabates for reading earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Aggregated from the MoHE database for the academic year.

2 There is only three years of data for the private sector. Therefore, the analysis was limited to three years.

3 I excluded from the data two courses: Applied Science and Financial Science as their data is incomplete and would impact the accuracy of the analysis.

4 Limits exist for how many years students can stay enrolled in each course.

5 The data does not include the numbers of the private sector and virtual learning as the gender data is incomplete in these two tracks.

References

- Al-Abdullah, F. 2010. “The Reality of the None-Formal Higher Education in Syria from the Perspectives of Students [ واقع التعليم العالي غير النظامي في سورية من وجهة نظر الدارسين فيه ].” Damascus University 26 (3). https://www.damascusuniversity.edu.sy/mag/edu/images/stories/17-56.pdf

- Ball, S. J., J. Davies, M. David, and D. Reay. 2002. “‘Classification’ and ‘Judgement’: Social Class and the ‘Cognitive Structures’ of Choice of Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 23 (1): 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690120102854.

- Bellei, C., and C. Cabalin. 2013. “Chilean Student Movements: Sustained Struggle to Transform a Market-Oriented Educational System.” Current Issues in Comparative Education 15 (2): 108–123.

- Boudon, R. 1974. Education, Opportunity, and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. New York: John Wiley.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage Publications.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, 241–258. Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1998. The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of Power. (Vol. 42). https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086447499.

- Breen, R., and J. H. Goldthorpe. 1997. “Explaining Educational Differentials: Towards a Formal Rational Action Theory.” Rationality and Society 9 (3): 275–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/104346397009003002.

- Buckner, E. 2013. “The Seeds of Discontent: Examining Youth Perceptions of Higher Education in Syria.” Comparative Education 49 (4): 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2013.765643.

- Buckner, E., and K. Saba. 2010. “Syria’s Next Generation: Youth un/Employment, Education, and Exclusion.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 3 (2): 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/17537981011047934.

- Bukodi, E., and J. H. Goldthorpe. 2013. “Decomposing ‘Social Origins’: The Effects of Parents’ Class, Status, and Education on the Educational Attainment of Their Children.” European Sociological Review 29 (5): 1024–1039. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcs079.

- Bukodi, E., J. H. Goldthorpe, and Y. Zhao. 2021. “Primary and Secondary Effects of Social Origins on Educational Attainment: New Findings for England.” The British Journal of Sociology 72 (3): 627–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12845.

- Central Bureau of Statistics-Syria. 2012. Population and Statistics Indicators. Central Bureau of Statistics-Syria. http://cbssyr.sy/yearbook/2012/Chapter2-AR.htm.

- Central Bureau of Statistics-Syria. 2015. Population and Statistics Indicators. http://www.cbssyr.sy/yearbook/2015/Chapter2-AR.htm.

- Chesters, J., and L. Watson. 2013. “Understanding the Persistence of Inequality in Higher Education: Evidence from Australia.” Journal of Education Policy 28 (2): 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.694481.

- Cini, L. 2019. “Disrupting the Neoliberal University in South Africa: The #FeesMustFall Movement in 2015.” Current Sociology 67 (7): 942–959. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392119865766.

- Crawford, C., and E. Greaves. 2015. Socio-Economic, Ethnic and Gender Differences in HE Participation. UK Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/higher-education-participation-socio-economic-ethnic-and-gender-differences.

- David, A. M., and M. A. Marouani. 2012. “Poverty Reduction and Growth Interactions: What Can Be Learned from the Syrian Experience?” Development Policy Review 30 (6): 773–787. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7679.2012.00598.x.

- Davies, P., T. Qiu, and N. M. Davies. 2014. “Cultural and Human Capital, Information and Higher Education Choices.” Journal of Education Policy 29 (6): 804–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2014.891762.

- De Gayardon, A. 2017. “Free Higher Education: Mistaking Equality and Equity.” International Higher Education 91: 10–12. https://doi.org/10.6017/ihe.2017.91.10126.

- Dillabough, J., O. Fimyar, C. McLaughlin, Z. Al-Azmeh, S. Abdullateef, and M. Abedtalas. 2018. “Conflict, Insecurity and the Political Economies of Higher Education.” International Journal of Comparative Education and Development 20 (3/4): 176–196. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-07-2018-0015.

- Dillabough, J., O. Fimyar, C. McLauglin, Z. Al-Azmeh, and M. Jebril. 2019. The State of Higher Education in Syria Pre-2011. Council for At-Risk Academics (Cara) and The University of Cambridge. https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/networks/eri/publications/syria/.

- Duncan, O. D. 1972. Socioeconomic Background and Achievement. New York: Seminar Press.

- Durkheim, É. 1956. Education and Sociology. New York and London: The Free Press; Collier-Macmillan.

- Durkheim, É. 1997. The Division of Labor in Society. USA: Free Press.

- Durkheim, É. 2002. Moral Education. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

- El Laithy, H., and K. Abu-Ismail. 2005. Poverty in Syria: 1996-2004: Diagnosis and Pro-Poor Policy Considerations. United Nations Development Programme. https://catalog.ihsn.org/citations/26996.

- Espinoza, O., L. E. González, L. Sandoval, N. McGinn, and B. Corradi. 2022. “Reducing Inequality in Access to University in Chile: The Relative Contribution of Cultural Capital and Financial aid.” Higher Education 83 (6): 1355–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00746-z.

- Flemmen, M. P., M. Toft, P. L. Andersen, M. N. Hansen, and J. Ljunggren. 2017. “Forms of Capital and Modes of Closure in Upper Class Reproduction.” Sociology 51 (6): 1277–1298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517706325.

- Goos, P. 2015. Statistics with JMP: Graphs, Descriptive Statistics and Probability. West Sussex, England: Wiley.

- Jones, J. S., and J. Goldring. 2022. Exploratory and Descriptive Statistics. SAGE.

- Kabbani, N., and S. Salloum. 2011. “Implications of Financing Higher Education for Access and Equity: The Case of Syria.” PROSPECTS 41 (1): 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-011-9178-6.

- Lee, E. M., and R. Kramer. 2013. “Out with the Old, In with the New? Habitus and Social Mobility at Selective Colleges.” Sociology of Education 86 (1): 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040712445519.

- Lomer, S., and M. A. Lim. 2022. “Understanding Issues of ‘Justice’ in ‘Free Higher Education’: Policy, Legislation, and Implications in the Philippines.” Policy Reviews in Higher Education 6 (1): 94–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2021.2012242.

- Maziak, W., K. D. Ward, F. Mzayek, S. Rastam, M. E. Bachir, M. F. Fouad, F. Hammal, et al. 2005. “Mapping the Health and Environmental Situation in Informal Zones in Aleppo, Syria: Report from the Aleppo Household Survey.” International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 78 (7): 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-005-0625-7.

- Mehran, G. 2009. “‘Doing and Undoing Gender’: Female Higher Education in the Islamic Republic of Iran.” International Review of Education 55 (5-6): 541–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-009-9145-0.

- Meyer, J. W. 1977. “The Effects of Education as an Institution.” American Journal of Sociology 83 (1): 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1086/226506.

- Ministry of Higher Education. n.d. Indicators and Statistics on the Higher Education Sector. Ministry of Higher Education. Accessed March 8, 2022, from http://www.mohe.gov.sy/mohe/index.php

- Mont’Alvão, A. 2015. “Institutional Differentiation and Inequalities in the Higher Education in Brazil.” Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais 30 (88): 129–143. https://doi.org/10.17666/3088129-143/2015.

- Naidoo, R. 2004. “Fields and Institutional Strategy: Bourdieu on the Relationship Between Higher Education, Inequality and Society.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 25 (4): 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569042000236952.

- Naiem Zeeb, R. 2023. “The Problems of the Open Learning from the Perspectives of Students in the Univerity of Damascus [في جامعة دمشق مشكلات التعليم المفتوح من وجهة نظر طلبة التعليم المفتوح ].” Tishreen University Journal- Arts and Humanities Sciences Series. https://journal.tishreen.edu.sy/index.php/humlitr/article/view/525.

- Petesch, P. 2017. “Agency and Gender Norms in War Economies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Gender and Conflict, 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199300983.013.27.

- Pla, J., S. Poy, A. Salata, and A. Salvia. 2021. “Social Class Inequalities and Access to Higher Education in Argentina and Brazil during an Expansion Stage of the Educational System.” Foro de Educacion 19 (2): 69–92. https://doi.org/10.14516/fde.874.

- Reay, D., G. Crozier, and J. Clayton. 2010. “‘Fitting in’ or ‘Standing Out’: Working-Class Students in UK Higher Education.” British Educational Research Journal 36 (1): 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902878925.

- Rosenthal, F. 2005. The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History – Abridged Edition (ABR-Abridged). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvwh8dcw

- Salmi, J. 2018. All Around the World – Higher Education Equity Policies Across the Globe. The Lumina Foundation. https://worldaccesshe.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/All-around-the-world-Higher-education-equity-policies-across-the-globe-FINAL-COPY-2.pdf.

- Salmi, J., and R. M. Bassett. 2014. “The Equity Imperative in Tertiary Education: Promoting Fairness and Efficiency.” International Review of Education 60 (3): 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-013-9391-z.

- Salmi, J., and A. D’Addio. 2021. “Policies for Achieving Inclusion in Higher Education.” Policy Reviews in Higher Education 5 (1): 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322969.2020.1835529.

- Salmi, J., and A. Sursock. 2018. Access and Completion for Underserved Students: International Perspectives [Working paper]. American Council on Education.

- Samuels, R. 2013. “Why Public Higher Education Should Be Free: How to Decrease Cost and Increase Quality at American Universities.” In Why Public Higher Education Should Be Free. Rutgers University Press. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813561257

- Sankar, S. 2000. The Development of the Higher Education Sector (1970-2000), and Future Directions. Syria: Syrian Ministry of Higher Education.

- Smits, J., and J. Huisman. 2013. “Determinants of Educational Participation and Gender Differences in Education in six Arab Countries.” Acta Sociologica 56 (4): 325–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699313496259.

- Soares, F. A., and B. L. C. A. de Oliveira. 2022. “Privatization and Geographic Inequalities in the Distribution and Expansion of Higher Nursing Education in Brazil.” Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 75 (4). https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2021-0500

- Tozan, O. 2023a. “The Evolution of the Syrian Higher Education Sector 1918-2022: From a Tool of Independence to a Tool of war.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 0 (0): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2023.2265854.

- Tozan, O. 2023b. “The Impact of the Syrian Conflict on the Higher Education Sector in Syria: A Systematic Review of Literature.” International Journal of Educational Research Open 4: 100221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedro.2022.100221.

- Voicu, B., and M. Vasile. 2010. “Rural-urban Inequalities and Expansion of Tertiary Education in Romania.” Journal of Social Research and Policy 1 (1): 5–24.

- Williams, M., R. Wiggins, and P. R. Vogt. 2021. Beginning Quantitative Research. SAGE Publications.