The role of exercise as medicine has been recognized for an extraordinarily long time; however, many individuals have limited tolerance or adherence to traditional exercise. Passive heat stress produces significant physiologic responses in humans, some of which match those that occur during exercise. We have recently demonstrated that lower-limb hot-water immersion in peripheral arterial disease (PAD) patients and healthy, elderly controls induces favorable shear stress and blood flow profiles in both upper and lower limb arteries, alongside several other beneficial cardiovascular responses.Citation1 Repetition of such a heat stimulus may induce cardiovascular and hemodynamic adaptations associated with improved health, thus providing an exercise substitute or adjunct. Indeed, passive heat as a stand-alone stressor is being suggested in the literature, with increasing frequency and conviction, to have potential to improve health in this way. But before we herald the hot tub as the newest elixir of health, some considerations warrant discussion.

Heat therapy is not a new idea. Hot baths, steam rooms and saunas have been used around the world for millennia. Geographically, different customs and beliefs have developed, but it would be safe to say that many cultures consider this method of relaxation, reinvigoration and cleansing of toxins an essential part of a healthy and happy life. Traditional beliefs of the healing properties associated with sauna, for example, are as ancient as the practice itself. Recent data from a longitudinal study (> 20 y) on > 2,000 middle-aged Finnish adults highlighted the reduced risk of sudden cardiac death, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality with increased sauna bathing frequency,Citation2 affirming the position of sauna in modern healthcare.

Researchers have recently focused attention on understanding the mechanisms by which heat exposure induces acute responses that ultimately promote long-term health benefits. In accordance with Selye's General Adaptation Syndrome, understanding the acute responses informs potential long-term adaptations. Much of the research has focused on animal models and healthy, young individuals, for whom results are promising, with improvements demonstrated in aerobic power, macro- and microvascular function and structure, as well as glucose control. We examined lower-limb hot-water immersion in healthy, young volunteers to characterize the stimulus and compare it to a commonly used exercise training stimulus, a 30-min treadmill run.Citation3 The main findings were the hot-water immersion induced favorable shear stress patterns in the lower limb arteries, as well as increased core and muscle temperature, and transitory hypotension. Such empirical evidence is pivotal, as only by exploring these relationships between the stressor and its ensuing effect, can we understand how and for whom, heat therapy may be used in the future. However, it is important that we communicate these results to the general public with caution so that the message circulating is not that we have found a comprehensive substitute for exercise, as a message like this will be seized to bypass physical activity. Nevertheless, if heat can do even a few beneficial things, we should capitalize on its accessibility and continue to study how to increase its potency.

As researchers delve into the mechanisms, the potential clinical utility of heat therapy is becoming more apparent. PAD is a condition in which to explore the efficacy of heat because of the nature of patients' intolerance to exercise. PAD, characterized by systemic atherosclerosis, commonly manifests as intermittent claudication; walking-induced calf pain due to insufficient perfusion. Conservative treatment for this group is – ironically – exercise, as walking is largely effective at slowing disease progression via promoting the growth of collateral vessels. A research group based in Japan has tested repetitive heat in the form of Waon therapy in patients with PAD. In a short communication in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology in 2007, they described a study in which 20 patients with PAD sat in a dry sauna at 60°C for 15 min followed by 30 min under a blanket, repeated five times weekly for 10 weeks.Citation4 The authors reported a profound reduction in pain score associated with walking, improved walking distance and a universal increase in two measures of perfusion; laser Doppler and ankle-brachial index. Unfortunately, there was no control group. The same researchers followed this up with a controlled study lasting 6 weeks in which they demonstrated similar benefits in a Waon therapy group to those described in the 2007 study. To my knowledge, these are the only two studies to investigate repetitive heat therapy in PAD so far; notwithstanding, these findings support the notion that heat may provide some benefit in this population.

It is important to understand if heat therapy does provide clinical benefit for PAD patients, whether this is via an improvement in the inflow vessels' ability to dilate, via a downstream effector of increased perfusion, or via some other mechanism. Also important is to quantify any effect on systemic cardiovascular health, if heat is ever going to play a role as an exercise substitute. Two studies were published in the last year on the acute responses to passive heat in PAD.Citation1,Citation5 Our research group pursued a lower-limb hot-water immersion protocol following the initial findings with this in healthy individuals.Citation3 We examined the acute hemodynamic responses within the upper and lower limbs (to investigate between-limb differences), along with systemic cardiovascular responses to lower-limb hot-water immersion in patients with PAD (n = 11) and in healthy, elderly controls (n = 10).Citation1 The main findings were as follows: (a) antegrade shear rate in the popliteal artery increased (p < 0.0001) comparably between groups (Controls: +183 ± 26%; PAD: +258 ± 54%), and (b) lower-limb blood flow increased significantly in both groups, as measured by duplex ultrasound (> 200%). Importantly, the ultrasound-derived increased perfusion was also reflected in two other measures; arterial inflow obtained via venous occlusion plethysmography and indices of oxygenated and total hemoglobin measured by near-infrared spectroscopy. Lower-limb hot-water immersion also induced both central and systemic cardiovascular strain; heart rate was increased by > 30%, and there was a pronounced reduction in mean arterial blood pressure in both groups (−20 ± 8 mmHg). The hypotensive effect persisted for several hours following, albeit measured in a subsample of participants. During the passive lower-limb heating, core body temperature (measured via tympanic thermistor) was elevated > 1°C in all individuals.

The findings of Neff et al.Citation5 were broadly consistent with ours. Neff et al. used water-perfused suits to study blood flow in the popliteal artery, blood pressure and circulating cytokines and vasoactive mediators in PAD patients (n = 16).Citation5 This method of passive lower-limb heating induced core temperature elevations of 0.5–1.0°C.Citation5 The authors reported increased blood flow of ∼100% in the popliteal artery measured by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (p < 0.01), and a reduction in systolic and diastolic blood pressure that persisted for 2 h (−11 mmHg and −6 mmHg, respectively, p < 0.05).

These two studies have illustrated that lower-limb heating (via two different methods) acutely increases limb perfusion, lowers blood pressure, induces positive chronotropy and elevates core temperature. These results further support the idea of repetitive hot-water immersion as a tool to provide cardiovascular conditioning for PAD patients, and elderly individuals without PAD alike, whom for whatever reason may not be able (or willing) to exercise.

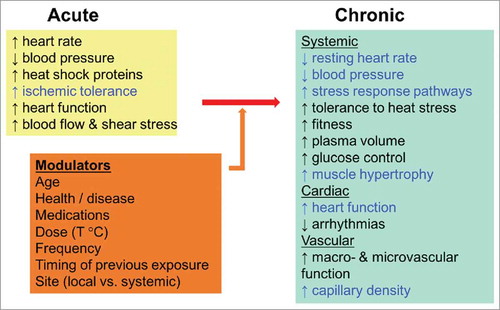

The use of heat as cardiovascular therapy is still in its infancy. Relatively little is known regarding several aspects, in particular, whether these acute responses translate into chronic adaptation. For example, it is unclear if increased antegrade shear rate, a key driver for adaptation in healthy arteries, provides the same stimulus in diseased arteries. This causality is yet to be examined in atherosclerotic vessels, although a similar role seems plausible. Furthermore, our understanding of the factors that may modulate the adaptations to heat and therefore augment or moderate its long-term therapeutic role is limited (). Further research in this area should explore some of these factors so that heat can be optimized and applied most appropriately.

Figure 1. Effects of passive heat and the relationship between acute exposure and chronic adaptation. Black text indicates clear experimental evidence to support this effect. Blue text indicates emerging evidence (primarily from animal models) to support this effect.

We have a lot to learn before heat therapy is prescribed in clinics, but in the future, it may be a powerful tool for clinical populations. Particularly for those with PAD, who are confronted with the contradiction of having much to gain from exercise yet being so limited in their ability to perform regular exercise. Of note was that the lower-limb hot-water immersion was well tolerated by participants in our study, and therefore this likely provides a larger hemodynamic and cardiovascular stimulus than PAD patients are able to get from walking, as the time they can engage in this activity is so limited. The main aims of treatment of PAD are to reduce high cardiovascular risk, limit functional impairment and reduce symptoms; auspiciously heat therapy may hold potential to assist in all three aspects. Although promising, whether the acute responses reported translate into health and functional benefits remains to be seen. Against this background, a randomized, controlled, interventional trial in PAD is vital and should be the next step in this line of inquiry. The acute responses described here should also encourage further studies on heat therapy for cardiovascular conditioning in other groups with limited access to exercise.

References

- Thomas KN, van Rij AM, Lucas SJ, Cotter JD. Lower-limb hot-water immersion acutely induces beneficial hemodynamic and cardiovascular responses in peripheral arterial disease and healthy, elderly controls. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2017;312(3):R281-R91. PMID: 28003211; doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00404.2016.

- Laukkanen T, Khan H, Zaccardi F, Laukkanen JA. Association between sauna bathing and fatal cardiovascular and all-cause mortality events. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):542-548. PMID: 25705824; doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8187.

- Thomas KN, van Rij AM, Lucas SJE, Gray AR, Cotter JD. Substantive hemodynamic and thermal strain upon completing lower-limb hot-water immersion; comparisons with treadmill running. Temperature. 2016;3(2):286-297. PMID: 27857958; doi:10.1080/23328940.2016.1156215.

- Tei C, Shinsato T, Miyata M, Kihara T, Hamasaki S. Waon therapy improves peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2169-2171. PMID: 18036456; doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.025.

- Neff D, Kuhlenhoelter AM, Lin C, Wong BJ, Motaganahalli RL, Roseguini BT. Thermotherapy reduces blood pressure and circulating endothelin-1 concentration and enhances leg blood flow in patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;311(2):R392-400. PMID: 27335279; doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00147.2016.