ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the impact of modern war on haptic sensations and rehabilitation culture aimed at healing physical and psychological wounds. It examines the haptic senses in occupational therapy and in the vocational retraining of the blind as masseurs and physiotherapists. Military patients’ creative responses to rehabilitation form a key part of the discussion, responding to the pressure to overcome painful wounds and disabilities. While much recent scholarship has focused on the re-masculinizing purpose and industrial discourse underpinning rehabilitation (either in returning to the frontline or to usefulness and economic production), this paper examines the haptic dimension of men’s handicrafts and other sensory elements within rehabilitation. It highlights the role of nature in rehabilitation and in personal responses to a war injury, through the pervasive symbol of the butterfly, found in diverse cultural arenas from therapeutic handicrafts to war memorials. It explores how nature enabled wounded soldiers to escape from the horror of industrial scale, mechanized wounding and considers whether the butterfly emblem resonated among men for its fragile beauty, which acted as a form of soft resistance to the disciplinary aspects of rehabilitation and the brutality of the war more generally. I argue that this was linked to the wider cultural effort to explain the impact of modern war on the human sensory experience through the enigmatic butterfly.

The First World War produced large numbers of wounded with multiple injuries and disabilities, creating an unprecedented need for rehabilitation facilities, expertise and humanitarian voluntarism. Historians have explored different aspects of rehabilitation, such as medical treatments and social experiences, or the political platform upon which public health and disability legislation was based in the subsequent twentieth century. In Britain, as in other combatant countries, national programmes were developed. But the sheer scale of disability and mutilation necessitated an international exchange of ideas between rehabilitation and repatriation authorities in Britain (Bourke Citation1996; Anderson Citation2011; Reznick Citation2011; Reid Citation2012), France (Delaporte Citation1996; Gehrhardt Citation2015), Belgium (Verstraete and Van Everbroeck Citation2018), Germany (Cohen Citation2001; Perry Citation2014), North America (Gerber Citation2000; Verville Citation2018; Linker Citation2011; Kinder Citation2015), and Australia (Scates and Oppenheimer Citation2016). Most patients were given initial occupational or handicraft therapies in tandem with or in advance of more demanding physical treatments, such as physiotherapy, heliotherapy, balneology, faradism, gymnastic exercises and sports. Permanently disabled men were offered curative workshops and vocational retraining (usually a manual trade), such as through the Lord Roberts workshop or the Soldiers and Sailors Help Society, especially important for those unable to return to their previous employment. The idea of successful rehabilitation fundamentally required men to overcome pain and impairment by exercising masculine traits of willpower and determination. The gendered politics of reconstruction emphasized returning fit soldiers to the front or reintegrating ex-servicemen into working and family life, thereby reducing the burden of pensions on the government (Carden-Coyne Citation2009).

The historiography on rehabilitation has rightly emphasized masculinity, male bodies and work, highlighting disciplinary regimes, and revealing the extent to which the coercive culture of stoicism was imposed upon and personally internalized by wounded and disabled men (Bourke Citation1996; Gagen Citation2007). Yet in doing so, the scholarship also marginalizes the role of occupational therapy, which, though integral to the gendered process of rehabilitation, offered patients a surprising capacity to express themselves creatively. Ward or bedside occupations exempted patients temporarily from military duty and the demands of masculine soldiering, also reflecting the temporary easing of gender norms made possible by the 'topsy-turvydom' of wartime society (Doan Citation2013). This hitherto unexplored aspect of rehabilitation is the focus of this paper. I aim to uncover men’s creative responses to their wounding and closely examine the haptic dimension of handicraft therapies and other sensory aspects of occupational therapy, such as the retraining of blind masseurs. The second aim of the paper is to explain the role of touch and nature in these therapeutic regimes and the historic role of what I call ‘the haptic arts’ – activities connecting the healing powers of touch with creativity. One of the key discoveries of this research is the artistic interpretation of nature in occupational therapies, and especially the recurring symbol of the butterfly. Drawing on the methods of medical history, cultural history, and interdisciplinary scholarship on the senses, the paper aims to give prominence to this neglected history of wounded men’s creativity.

Occupational therapy – the teaching and learning of handicrafts such as embroidery, painting, pottery and basket weaving – has been recognized in studies of civilian mental asylums, but has not been singularly examined as a treatment for the physically or mentally wounded in wartime. Despite the extensive scholarship on shellshock, the creativity of patients who made handicrafts has been overshadowed (see Bourke Citation1996; Leese Citation2002; Jones and Wessely Citation2005; Van Bergen Citation2009; Reid Citation2012; Meyer Citation2009). Marjorie Gehrhardt mentions that handicraft therapies were offered to facially wounded patients to counteract depression and suicidal thoughts (Gehrhardt Citation2015: 82). However, few details have emerged regarding what handicraft making actually meant for military patients. Cultural historians of war and historians of both military and humanitarian medicine need to think more about the potency and meaning of creative practices, haptic arts, aesthetics, symbols and beauty, especially for those whom society might shun. My focus on wounded and disabled men’s handicrafts aims to uncover more insight into this widely ignored history, while considering the remedial effects of creativity and the role of touch and nature hidden in the history of rehabilitation. I will demonstrate that while military authorities sought to reclaim soldiers for military service or repatriate them as productive citizens, what emerged was men’s creativity and expressive interest in flowers, gardens, and butterflies.

While not wishing to overstate the significance of nature and butterflies, my intention is to account for why they feature not just in therapeutic handicrafts, but also in a diverse set of cultural forms associated with the war, such as poetry and memoirs, war memorials and cinema. These concurrences may have been fleeting and arbitrary, but taken together they suggest how a different history of the war might be garnered from fragments and small gestures, through the textures of inconsequential objects stowed in attics as intimate yet incomplete memories. The ambition of this paper is to make the case for the haptic arts as an important area for study against the grain of the war’s grand narratives. Did the wounded man’s turn to nature transport him to an imagined safety and tranquillity, away from the sordidness of killing and dying? Was it an expression of his soft resistance to industrial warfare, military discipline, or the expectations of heroic and stoic masculine performativity? Did the butterfly resonate among young soldiers because of its ephemeral beauty and association with childhood innocence? The paper considers how this fragmentary history of haptic gestures related to wider cultural efforts that sought to explain the impact of modern war on human sensory experience.

Modern industrial war and haptic labour

The First World War presented new problems of maintaining the health of servicemen drawn from the civilian population and recovering the wounded for active duty. The citizen’s body became valued differently: as material, as part of a collective unit, and as an object to be measured, tested, trained, and disciplined into one cohesive formation. Fitness to serve was historically linked to the body as a national symbol of martial masculinity (Dawson Citation1994). But the scale of wounds from artillery and shellfire, chemical burns, trench foot, gas gangrene and tetanus infections, and record numbers of disabled veterans troubled the image of national fitness. Governments recognized that the scale of the programmes needed was unprecedented, but rehabilitation was also tied to civic duty in the process (Waugh Citation1920).

The premise of rehabilitating patients in wartime was underpinned by its longer history as work therapy. As Jennifer Laws argues, capitalist ideology shaped the emphasis on usefulness though the primary purpose of occupational therapies was therapeutic (Laws Citation2011, 69−71). Work therapy aimed to transform the sick into semi-skilled craft workers. In addition, the influence of aestheticism and the Arts and Crafts movement countered the mass-production of goods in factories built for speed and efficiency. Radically different, therapeutic handicrafts slowed time down, emphasizing individual artistry, and symbolically turning away from the horror of modern war to an older era of gentler pursuits. But veteran handicrafts were also part of a rising market of humanitarian consumerism, which had a long history of supporting the ‘heroic sufferings’ of wounded soldiers (Roddy, Strange, and Taithe Citation2018, 105). Furthermore, inspired by aestheticism and the Arts and Crafts movement, a few patients were able to develop sufficient skill to work in cottage industries and form their own guilds, such as the Guild of Soldier and Sailor Broderers in the 1920s.

The act of hand-making objects had a renewed sensory and emotional role in the context of modern warfare. Leonora Auslander and Tara Zahra write that mass conscription, mechanized warfare and incarceration ‘transformed the meaning and materiality of things as much as the lives and bodies of human beings’ (Auslander and Zahra Citation2018, 13). Modern industrial war saw touch, the ‘deepest sensation’ according to Constance Classen, adapt physically and psychologically to the ‘unresponsive, alien tactility’ of its weaponry (Classen Citation2012, 180). Yet the industrial mentality of war medicine meant that technological solutions would fix wounds and modern machines would replace limbs. Addressing the loss of arms, hands and haptic sensations from nerve injuries, the prosthetics industry promoted the utility of artificial hands, such as the Pringle-Kirk hand, replacing human touch with bionic possibilities (Little Citation1922). However, by prescribing handicraft therapies as bedside treatments or ‘ward occupations’, military medicine accentuated the humble essence of haptic sensations. To be sure, older ideas of distracting men from introspection, and making them useful instead of idle, were sustained in rehabilitation. But new ideas regarding sensory stimulation and fine motor dexterity, which placed stitching and embroidery as treatments for hand and nerve injuries, arose too.

Military doctors also recognized that worn out soldiers need rest and recuperation, for which handicrafts were well suited as ‘ward occupations’ or for men confined to their beds. Handicrafts maintained a longstanding and respected tradition in military culture. Victorian regiments prized embroidered uniforms and patchwork quilts. During the Crimean War, as Holly Furneaux argues, it had an emotional and domestic connection to such homely arts that was commonplace for ‘military men of feeling’ (Furneaux Citation2016). In the First World War the emphasis on technological killing at scale, and thus the industrial character of mass wounding, may have generated a shift in the expectations of military masculinity as the certainty of conventional heroic models withered. The emotional and sensory impact of modern war on men’s bodies and minds, arguably, affected the gender order. Medics believed that the ‘strain’ on volunteers and conscripts was producing strong emotions that had to be repressed (Jones Citation2010, 386; Feudtner Citation1993). Yet, wounded men responded with creativity by turning away from the battle to nature. We shall examine how and why the butterfly emerged as a distinctive and pervasive symbol in the haptic arts.

This creative turn to nature is complex given the medical and public expectation that servicemen should heroically overcome their disabilities and reclaim their masculinity. Though the visibility of the war disabled elicited mixed reactions of pity and misgiving, older debates about the sensory capabilities of the blind in ‘seeing with their hands’ resurfaced at this time (Paterson Citation2006). Just as the ‘tactile imagination’ had been a dynamic element of nineteenth-century cultural life, the war revived the belief that, far from handicapped, the war blind acquired superior powers of touch and feeling (Tilley Citation2014). Nowhere was this discourse more evident than in the retraining of blind men as masseurs. If a man with one seriously damaged sense could acquire a delicate touch, then he achieved a superior form of masculine rehabilitation. The paradox of frailty and capacity in attitudes to wounds and disabilities was intensified when young men were permanently injured in war. As we shall see, the cultural practices of poetry, novels, and films, as well as experiences of haptic labour (such as embroidery and massage) engaged with the rehabilitation culture of the times, to an extent that the war disabled were thought to have become extra-sensory.

Haptic myths: the sensitive touch of the war blind

Representations of the haptic senses evoke the central wartime themes of trauma and healing in this period. The hands were particularly important in the context of physiotherapy, with their capacity to stroke, soothe and caress, but also to apply pressure, manipulate and cause pain. Nurses and female physiotherapists, as I have shown elsewhere, were expected to fulfil a feminine fantasy of tenderness based on their natural capacity for caregiving, but they could also be accused of failing their nature when carrying out painful procedures on men’s bodies (Carden-Coyne Citation2008; Carden-Coyne Citation2008, Morris, and Wilcox Citation2014, 250). While sensitive handling and soothing touch were aligned with emotional care, this took on new significance with the advent of hundreds of disabled ex-servicemen who were trained as massage therapists. Founded by the newspaper magnate Sir Arthur Pearson (who had lost his sight from congenital glaucoma and served on the Council of the National Institute for the Blind), St Dunstan’s was a major centre of rehabilitation. Deaf and blind soldiers trained in ‘useful’ or ‘ornamental’ handicrafts, telephony, shorthand, and massage. Students received anatomy and physiotherapy instruction by women from the Chartered Society of Massage and Medical Gymnastics (later the Incorporated Society of Trained Masseurs), which oversaw the exams and held the awarding powers for professional qualifications. The presence of the female instructor was depicted in J. H. Lobley’s painting Anatomy Lessons at St Dunstan’s (1919), with a woman teaching blind ex-servicemen to feel the bones of a human skeleton.Footnote1 The special skill of sensitive touch taught by women reinforced the gendered underpinnings of rehabilitation.

The war thus transformed the conventions of massage and physiotherapy as a female-dominated industry with the influx of blind men trained in the profession. Of the 1700 blind soldiers who passed through St Dunstan’s, those who retrained as masseurs were said to be earning ‘comfortable livings’ by 1918. In time, ‘hospital superintendents were loud in their praise’ and the Society for Blind Masseurs was established as a subset within the professional body of the Society for Trained Masseurs (Dark Citation1922). Pearson continued as the dominant figure in the rehabilitation industry, gaining the professional recognition of the war blind. He also inspired the wounded to ‘conquer’ their disabilities in his book, Victory Over Blindness: How it was Won by the Men of St. Dunstan’s and How Others May Win It (1919). Here, he singled out the blind masseurs for mastering ‘a considerable knowledge of anatomy, physiology and pathology … and gaining manipulative dexterity’ with highly skilled hands (Pearson Citation1919, 119). Blind masseurs were esteemed for their gentleness and sensitivity but also their skill and strength, keeping their masculinity in tact. By contrast, female masseurs were expected to apply a ‘feminine touch’, but could be accused of applying too much force and pain. As Constance Classen attests, ‘sensory models of male and female nature were inflected with gender ideologies that – far from being immutable – could be manipulated with a skilful touch’ (Classen Citation2012, 74).

Alongside their achievements, health and military authorities held that the tactile capacities of blind masseurs were enhanced (Dark Citation1922, 90). Renowned orthopaedist Sir Robert Jones employed several blind masseurs at Alder Hey hospital in Liverpool, and found ‘them all intelligent and possessed of a wonderful gift of touch, together with a keen enthusiasm for their work’ (Dark Citation1922, 162−3; my emphasis). Blind veterans’ haptic abilities were thought to be superior to that of sighted women and men, since the loss of one sensory or embodied capacity was compensated with the enhancement of another. Yet, these recently blinded masseurs had only received training for a period of 12 to 18 months. Indeed, some critics insisted that sight was required for certain physiotherapeutic treatments (Lancet, 1920, 17 April, 886). Pearson answered the critics by accentuating the rigour of St Dunstan’s courses and exams, while acknowledging that ‘perfection’ was not entirely possible (Lancet, Citation1920, 6 March, 568). Pearson’s biographer, Sidney Dark, repeated the belief that blind soldiers had acquired ‘faculties’ that ‘a sighted man could hardly hope to attain’, concluding that ‘a blind man’s sense of touch … is far more subtle than the sense of touch possessed by the majority’ (Dark Citation1922, 172). Dark goes as far as stating that ‘in some instances blindness seems to have gifted the sufferer with new powers’ (Dark Citation1922, 73). Reinforcing the sentiments of overcoming disability typical of rehabilitation discourse, he writes, ‘blindness, far from being a handicap, has made life all the more interesting and more useful’ (Dark Citation1922, 194).Footnote2

The belief that blind ex-servicemen could acquire new haptic powers was shared amongst international military and medical visitors to St Dunstan’s, such as Major Fred Albee (Surgeon-in-Chief of US General Hospital 3 for Reconstruction, New Jersey, and Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at New York Postgraduate Medical School) who stated, ‘I know of no task so valuable for the delicate touch of the blinded man’ (Knopf Citation1918). The haptic myth of acquired sensitivity was part of a spectrum of contradictory attitudes that stereotyped and mythologized the disabled, evident also in the term ‘handicap’, as disability scholars have argued (Longmore and Umansky Citation2001). Pearson was the foremost champion of the war blind, but he also expressed contradictory views. For while ‘the sensitiveness and delicacy of touch’ made massage ‘an ideal occupation’ for the blind, he also cautioned against ‘one of the many fallacies’ of how rapidly ‘an exquisitely sensitive sense of touch evolves itself. This is not the case’ (Pearson Citation1919, 121, 103). Learning braille, for instance, took a long time and many men ‘found their Braille touch lacking in sensitiveness’ (Pearson Citation1919, 103). This led him to speculate about the kinaesthetic sensory relationships between the senses during the process of adjustment. The ‘lightest touch’ on a wall or object lent spatial perception to a blind man. But ‘sensitiveness of touch’ was learned and acquired over time, and not everyone achieved it (Pearson Citation1919, 64, 76, 83). Significantly, Pearson linked the process of ‘learning to be blind’ to gaining a sensory perception of nature:

It is one thing…to recognise a bird by its song, or to distinguish a flower by its scent – it is another to see in the mind’s eye the very blossom … to perceive the bird in its varied plumage. (Pearson Citation1919, 67)

Pearson was interested in the relative sensory capacities of the newly blinded and argued that such people ‘rely too much on touch and not enough on hearing’ (Pearson Citation1919, 90). Indeed, ‘smell has the power of awakening memories, or reviving in the mind forgotten scenes and experiences … and through sound comes a vivid excitement of the imaginative faculties’ (Pearson Citation1919, 90). Arguably, such ‘imaginative faculties’ were also developed in men’s engagement with art and handicraft therapies.

Julie Anderson and Neil Pemberton demonstrate that while the blind were imbued with heroic qualities, Pearson believed they had to ‘learn to walk alone’, asserting ‘the will to overcome blindness’ and adopting cheerful attitudes to retraining (Anderson and Pemberton Citation2007, 466). Blind professional physiotherapists took charge of the image of the weak disabled, instead becoming the strong healer. Work, productivity, and the useful disabled man were key to the capacity to exercise agency. Thus, as Matthias Reiss shows, when blinded men formed unions and guilds to empower themselves within the physiotherapy industry, they mobilized their image as effective workers against widely held anxieties about pity and charity (Reiss Citation2015).Footnote3

Following his interest in sensory perception, and his concern to understand what the servicemen had been through, Pearson travelled to the Western Front in 1917. He wanted to ‘sense’, rather than see, the conditions the men had lived through such as the slimy clay ground, gigantic holes, and jagged crevices. When a shell whizzed past him, he felt its reverberations and received a minor wound from a ricocheting stone. The devastated town of Peronne, he said, ‘gave me an impression of the utmost horror’ (Pearson Citation1919, 96−7). The visit reinforced his belief in rehabilitation through the tactile sensibilities of the blind.Footnote4 This was a view shared within military hospitals, where occupational therapies engaged the wounded in forms of creativity as part of the gendered process of rehabilitation.

Wounded handicrafts: gender, soft resistance and consumerism

The large numbers of wounded individuals significantly increased the demand for occupational therapies, handicraft teachers, and supplies of materials, such as needles, cloth, frames and paints. Though handicrafts were routinely prescribed to the wounded, there were varying beliefs in its efficacy among military doctors. Some regarded it as a feminine distraction from men’s ultimate business – war or work. Others, as previously mentioned, found positive results in improving fine motor skills for certain injuries. When working-class patients referred to it as ‘fancy work’, they did not attribute negative gender or class associations, as it was integral to recovering their masculinity. Military medicine regarded the wounded soldier as being temporarily feminized, while suspended from the masculine activity of operating machine guns, artillery guns, and tanks. Hospital recuperation introduced working-class men to craft therapies. Most recruits and volunteers would not have been aware of regimental handicraft traditions, such as patchwork quilts made from military fabrics and immortalized in Thomas William Wood’s Portrait of Private Thomas Walker (1856), a soldier whose crafts were purchased by Queen Victoria (Furneaux Citation2016). Hospitalisation was geared towards recovery, but it also suspended some of the gendered expectations of masculinity. The intimate atmosphere saw some men suffer sympathetic pains with each other. Commanders noted how men were ‘almost womanly in the tenderness’ they showed (G.Y.P Citation1916; Bush Citation1930, 51). Occupational therapy fitted into this emotional space, with its fluid gender culture, and its blurring of the military and domestic, gently resisting the expectations of return to the masculine order.

The presence of women as handicraft teachers is important in this context. Nurses and female volunteers from local communities gave instructions. In Britain, the volunteers were mostly middle-class ladies whose skills were drawn upon to teach soldiers embroidery, weaving, painting, pottery, and assist with the design of patterns and stencils. By contrast in the United States, trained ‘reconstruction aides’ helped soldiers make stencils and wood-block prints. At the major American facility, Walter Reed Army Medical Hospital in Washington DC, aide Lena Hitchcock recalled how a few men resented this kind of ‘work’, causing friction between male patients and female practitioners who felt their professionalism was disrespected (Hitchcock, n.d., vii). Others, though, found creative pleasure in domestic pastimes and comforting reminders of home, forming an emotional and psychological buffer against the harsh conditions of the frontline.

Servicemen, imperial troops and prisoners-of-war had long used handicrafts as a ‘form of survival’ and ‘an emotional lifeline to families at home’ (Furneaux Citation2016, 177−9). Military artistry was often imagined through regimental identity, in keeping with Victorian traditions. From the practical ‘housewife’ to an accomplished embroidered patchwork (such as by Charles Henry Gillingham, stationed in India in 1870), the ‘military man of feeling’, as Holly Furneaux states, was incorporated into regimental culture, garrison life and hospital recovery. Artisan quality handicrafts were prized, as Drummer Yeates of the 88th (Connaught Rangers) Regiment of Foot, whose elaborate ‘housewife’ won an award at a military workshop exhibition in 1867. The design included fine beadwork, and motifs of the Royal Crown, the Union Jack, the regimental insignia of an Irish harp, battle place names, and pictures of elephants and horses, and a message of longing.Footnote5

Similarly, some First World War patients chose patriotic themes, such as the Union Jack, regimental insignia or emblems of the imperial forces. For instance, Australian patient Private Frederick William Gephart (2nd Battalion, AIF) embroidered the ‘Australian Military Forces’ heraldry with the rising sun general service badge. In another item, he threaded together the King’s crown, the Union Jack and the Australian national flag, with lines from popular patriotic songs, such as ‘For England Home and Beauty’ and ‘Australia Will Be There’, a refrain from W. W. Francis’s 1914 patriotic song. The song, like the embroidery, merges the patriotic and domestic as Australian soldiers are called to ‘rally round the banner of your country’ in support of ‘England, home and beauty’.Footnote6 AIF Private Thomas Walter George Mason (33rd Battalion, AIF) stitched an elaborate Australian coat of arms with kangaroo and emu motifs.Footnote7 The use of these symbols underscored the wounded man’s belief in his personal sacrifice for the nation and Empire, and may have comforted an imperial soldier longing for his home far away. In Britain, Germany and Russia, internees were given instruction in a wide range of occupational therapy handicrafts, from elaborate bone and wood carving to embroidering and sewing pin-cushions, in order to counter mental and physical deterioration. Iris Rachimov argues that when people suffer temporary, spatial, social, emotional and psychological distances, objects and artefacts take on greater importance as ‘small escapes’ from confinement, displacement and distance. What is true for refugees, internees, migrants and POWs was also true for the wounded soldier in making objects that helped to bridge such distances, allowing them ‘to recreate a sense of domestic comfort, reconnect imaginatively with their loved ones’ (Rachimov Citation2018, 174, 166, 176).

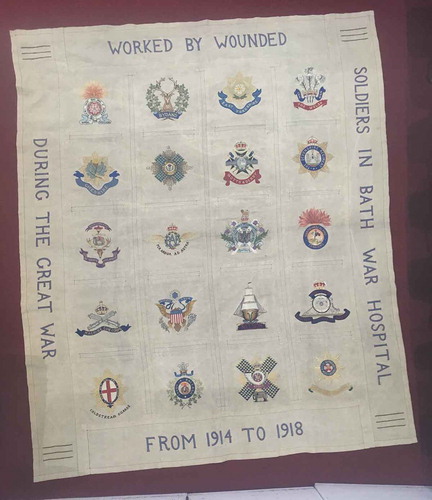

The range of men’s embroidery reflects personal and collective motivations. The British Red Cross collection includes a tiny piece of embroidered cloth with a miniature tank wrought in bright gold thread reproduced in painstaking detail, alongside Tank Corps insignia. By contrast to this tiny, individual piece is an ambitiously conceived collective work, embroidered by 20 wounded soldiers who were recovering at Bath War Hospital (). On a large linen cloth, 20 regimental motifs are finely embroidered in neat squares, surrounded by words embroidered in capital letters: ‘WORKED BY WOUNDED’, ‘DURING THE GREAT WAR’, ‘SOLDIERS IN BATH WAR HOSPITAL’, and ‘FROM 1914−1918ʹ.Footnote8

Figure 1. Occupational therapy linen, Bath War Hospital, ‘Worked by Wounded’, 1914–1918. © British Red Cross collection.

Sewn onto the linen, the phrase ‘Worked by Wounded’ reflects the longstanding tension between production and creativity whether in remedies for idleness or respite treatment. The tablecloth was not ‘created’ or ‘crafted’ by the wounded, but rather ‘worked’, and thus the cloth appears as evidence of masculine haptic labour. Working while healing from wounds incurred from service to the nation, the collective accomplishment characterizes the wounded men as heroic and enduring. The small, collective activity of stitching pieces together brings home an emotional and personal intimacy in contrast with the grand theme of the ‘great war’.

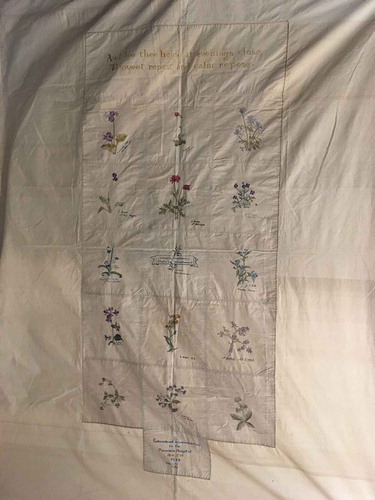

A second large linen cloth (2.2 x 1.66 m) consists of 15 individual squares of floral and plant themes (). Extraordinary in its simple design, each square contains a specific flower accompanied by the wounded man’s signature stitched in cursive script, with some also identifying their regiment. The men’s signatures allowed them to claim their personal pride in this modest creative form.

Figure 2. Occupational therapy linen. ‘Embroidered by wounded men in the Pensions Hospital, Bath, 1923ʹ. © British Red Cross collection.

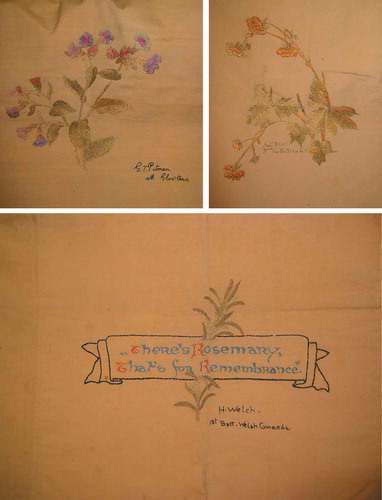

The accomplishment of each carefully embroidered composition is revealed in shades of pink-coloured petals and the effects of light and shadow, which bring nature to life, such as in a piece by G.T. Pitman of 10th Glo’sters. Tonal qualities of green and yellow leaves are emphasized in the piece made by A. Crane of the 2nd K.O.Y.L.I (King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry) ( and ). The middle square of the cloth design contains a sprig of rosemary and a placard: ‘There’s Rosemary, That’s for Remembrance’, signed in miniature by ‘H. Welch. 1st Batt. Welsh Guards’ ().

Figures 3–5. Three details of . Occupational therapy linen. ‘Embroidered by wounded men in the Pensions Hospital, Bath, 1923ʹ. ©British Red Cross collection.

Below the flowers is a panel with: ‘Embroidered by wounded Men in the Pensions Hospital, Bath, 1923ʹ, signed by G.H. Grisbourne, RAF. Above the floral squares is the poetic line ‘And hie thee home at evenings close, To sweet repast and calm repose’, which refers to the peasant’s return home from the day’s work.Footnote9 Taken from Thomas Gray’s (1716−1771) poem ‘Ode on the Pleasure arising from Vicissitude’, the changing seasons are metaphors for suffering and renewal. For the recently wounded, the use of the poem implies that their bodies and masculinity can be reclaimed. They can emerge regenerated from their chrysalis of pain. The poem further demonstrates how nature resonated with the wounded. For ‘the wretch, tossed on the thorny bed of pain’ can ‘repair his vigour lost’, rising ‘on wings of fire’ to walk again under the ‘sun, the air and skies’ (Gray Citation1821, 73). Thus an older Victorian perspective associating nature with pleasure, beauty and healing of the wretched was found to be meaningful. Nature, as we shall see, was a major inspiration in wounded handicrafts.

Some convalescents (such as in Bath, Summertown in Eastbourne, or Cambridge First Eastern hospital) were given open-air treatments, which brought nature and the elements into the hospital wards. Though favourable in the Summer months, patients had a chance to contemplate the natural surrounds. In other military hospitals, gardens were understood to be therapeutic in promoting healing (Reznick Citation2011, 48). The slowed temporal and tactile sensations of hand-making crafts, the homely feeling of clean sheets, and the access to hospital gardens supported wounded men’s recuperation. Yet, as patients graduated from occupation therapies to return to service or vocational re-training, the re-masculinizing project of rehabilitation became more apparent (Reznick Citation2011, x). The British War Office, individual politicians, and military authorities used a common language that identified ‘the problem of the disabled soldier’, as ‘[his] health and earning power’ and his reintegration into the civilian economy (Lancet, Citation1916, 867−8).Footnote10

Military and Red Cross hospitals were keen to show the public the soldiers were not idle while recovering. Newspapers frequently featured photographs of bed-bound patients undertaking handicrafts such as embroidery, knitting, weaving, painting figurines and pots, and even making lampshades. On-site exhibitions of patient handicrafts were a main area of fund-raising and provided occasions for public access to the wounded. The success of rehabilitation could be demonstrated as men had become ‘expert in the art’ of making objects, such as Canadian wounded sewing chintz patterns onto lamp shades.Footnote11 Nevertheless, the concern to rehabilitate soldiers into productive citizens was met with an older appreciation for artisanship and hand-made objects.

Patients in England and Wales were also taught how to make intricate beaded jewellery, which could be passed to family members as mementoes of service and survival, but were often also prized and collected.Footnote12 Between December 1917 and April 1918, Corporal Walter Stinson of the 11th Battalion, County of London Finsbury Rifles recovered from his wounds at the Cardiff Red Cross VAD Hospital on the grounds of St. Fagans Castle (, top right). Over a five-month period, he made beaded objects, including a butterfly belt-buckle. Tiny blue, gold and white glass beads were used to form the wings, and the body was made from costume pearls and a sparkling green zircon. Stinson made several of these items (). The Prince of Wales bought one at an exhibition fund-raiser for prisoners-of-war, while another was passed down through Stinson’s family, a precious touchstone of service and sacrifice.Footnote13

Figure 6. Photograph of Corporal Walter Stinson (top right), 11th Battalion, County of London, Finsbury Rifles ©Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales.

Figure 7. Close up of beaded butterfly buckle made by Corporal Stinson, St Fagans VAD Hospital, 1916. ©Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales.

The handicrafts made by the wounded and disabled not only possessed a unique emotional value for patients and families, but they were hugely popular among the public who were encouraged to purchase them. Collecting wounded handicrafts arose from sentimentality attached to the skill of hand-making in an era of mechanization, and was an enduring form of ‘charity consumerism’ and fund-raising, made visible by royal and upper-class sponsors of some 6,000 charities for the wounded and disabled in Britain at the time. One such collector was Mary (Hope) Greg (1850–1949), who was raised in a philanthropic family sympathetic to the Arts and Crafts movement, and had married into the Quarry Bank Mill fortune. Mary Greg amassed a huge collection of objects, including a work on paper by a disabled man. Mounted onto black card, the portrait of an eighteenth-century lady incorporates real butterfly wings in the design of her gown ().Footnote14 By acquiring the work, Mrs Greg was also supporting the redemptive and therapeutic value of handicrafts (Mitchell Citation2017). The artist was likely to be ‘Spaj’ Atkinson, who underwent rehabilitation therapy after being paralysed, blinded in one eye, and deafened following an accident. Atkinson gained an international reputation, with his work reported in the Australian, British and American press.Footnote15 Collectors of his work included Princess Helena Victoria, Mrs Stanley Baldwin, Viscountess Gage and the Marchioness of Cambridge, and Queen Mary.Footnote16 The international media attention Atkinson received suggests both the social pressures of stoicism and the spectacular gaze imposed upon disabled men, whether civilian or military.

Figure 8. ‘Butterfly card’ made by ‘Spaj’ Atkinson. Mary Greg collection 1922.1861 ©Gallery of Costume, Manchester Art Gallery.

Among military patients, there were a few instances when the degree of skill reached a high degree of artisanship that was publicly celebrated. One of the most successful and enduring groups was the Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry (DSEI), whose intricate patterns of foliage, flowers, and butterflies were sold commercially, shown in Arts and Crafts exhibitions, and designed for prestigious commissions.Footnote17 Male hands were celebrated as possessing the delicacy required for a craft considered the preserve of women. Still, since the DSWI was a business employing over 100 artisans, the masculine character of the industry was assured (McBrinn Citation2016). This commercial enterprise, however, was quite distinct from short hospital treatments intended as transitional episodes in the gendered process of rehabilitation.

Overall, occupational therapy handicrafts evoked a version of masculinity wrought by gentler pursuits, whereby time and sensation were slowed down. Making and creativity could also function as a form of acceptable and temporary ‘soft resistance’ to the expectation that men should overcome their pains and impairments, and rush back to the front. For soldiers caught up in the industrial war machine, handicrafts softly resisted this by their slow pace but also through the pleasurable domesticity of natural themes, and appreciation for gardens, flowers, and butterflies, and the use of bright colours, a world away from the muddy, dank conditions of trench warfare.

Therapeutic nature and the recuperative power of the butterfly

Since the nineteenth century, nature had played an historic role in occupational therapy, with gardening routinely assigned to patients in asylums. Claire Hickman argues that gardens were used as visual therapies in psychiatric asylums (Hickman Citation2013, Citation2009). In First World War military hospitals, neurological facilities, and command depots, gardening was prescribed to shellshock patients, some of whom helped maintain the grounds, as well as to soldiers soon to be returned to service as ‘a final hardening process’ (Lambert Citation1916, 789). Gardening was thus issued as both a therapeutic and disciplinary treatment. Additionally, some disabled and blind ex-servicemen retrained in horticulture, supported by the British Ophthalmological Society, and later formed the Guild of Blind Gardeners (Citation1921). Beatrice Duncombe claimed gardening should not be seen as a charity for ‘unfortunate people’, since it provided the means to be useful in society (British Medical Journal, 7 May 1921, 1, 680−8). Rehabilitation continued to inhabit the tensions between the utilitarian, expressive and soothing roles of its therapies. Thus, rehabilitation facilities might emphasize vocational retraining and turning the permanently disabled into productive citizens, such as by making furniture and objects for commercial sale, but it was also recognized that men needed respite and outdoor activity. At the Princess Louise Scottish Hospital for Limbless Sailors and Soldiers (Erskine, Glasgow), the extensive gardens and orchards of the former stately home were used so that ambulant patients could learn a trade such as gardening (Novotny Citation2017). At the same time, the gardens were also used as picturesque retreats for the residents and were accessible for wheelchairs (Calder Citation1982).

The war had also seen an increase in the number of commemorative gardens in local towns and cities, and as ‘integral components in the construction of the cemetery landscapes’. Under the direction of the Royal Botanic Gardens, the Horticultural Department of the Imperial War Graves Commission sent ‘travelling garden parties’ to transform No Man’s Land into picturesque memorial spaces reminiscent of English gardens and to ‘soften the appearance of graves’ (Morris Citation1997, 4). Military patients from the imperial forces also found sanctuary and creative inspiration from English and French gardens, farms and countryside vistas, and the local flora and fauna. Undertaking handicraft therapy while recovering in a foreign hospital, Australian Private William George Hilton (AIF, 19th Battalion) embroidered a cushion with a bucolic scene of a farmyard in the summer, with blue skies, ducks, and a tree in blossom.Footnote18

When taking up gardening and handicrafts, patients both communed with nature and also avoided reference to modern war and the suffering they had experienced. Mythic pasts might also inspire, such as a knight on a horse or a peasant girl in a forest, which may have been the influence of female instructors or an unconscious allusion to the masculine role of fighting for the women at home. We know that handicraft teachers did provide templates, but that men were also encouraged to make their own designs.Footnote19 Teachers may have been instructed to help patients avoid dwelling on the war, and certainly nature, and the outdoors were integral to therapeutic regimes. Extending natural themes into handicrafts was intended to be restful, and it may have been comforting in its association with home, childhood and safety.

One of the most popular motifs from nature featured in men’s handicrafts was the butterfly, as evidenced in the story of 23-year-old Lance Corporal Alfred Briggs. He had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force in 1915, and served first in Gallipoli and then the Western Front. He was shot in his leg at Pozieres, and evacuated to the 3rd London General Hospital until he recovered enough to be returned to the 20th Battalion in 1917. His actions at Lagnicourt saw him awarded the Military Medal for ‘great initiative and bravery’. Briggs was wounded a second time, at Bullecourt on 5th May, sustaining a deep shrapnel wound to his left knee and suffering a severe fracture of the humerus, just above his right elbow. Eventually, he arrived at the 1st Australian General Hospital in Rouen, before being transferred to the Tooting Military Hospital in London. Suffering from a physical and mental disability, he was dispatched to Sydney where he spent nearly two years at the 4th Australian General Hospital, Randwick. Through this prolonged and painful period of wounding, transport, and convalescence, Briggs was taught embroidery to assist the damaged nerves in his right arm. Despite his limited functional capacity, Briggs produced a detailed, idyllic scene and a complex composition on black cotton cloth with gold cord edging. On one side, an Australian coat of Arms appears, formed in stem and long stitch, and on the other side Briggs designed an abstract scene of six brightly coloured butterflies that almost flutter across the cloth. Nation and nature are mirrored in the design. A memento of proud service and sacrifice, the butterfly cloth was passed down to later generations in his family.Footnote20

The popularity of the butterfly motif may have come from soldiers’ exposure to French and Belgian silk embroidered postcards, which repurposed the butterfly as a patriotic symbol. Commercially produced and sold en masse to Allied soldiers, the cards included texts in English, such as ‘To my dear’ wife, mother, father, sister, or aunt, or with phrases such as ‘A Kiss from France’, ‘Don’t Forget Me’, and ‘From your Soldier Boy’. Butterflies were placed alongside stirring messages such as ‘Towards Victory’ and ‘For Freedom’, alluding to what and for whom the men were fighting. Individual allied flags were also integrated into the spaces of the butterfly’s wings, or were combined to form the ‘united flags of the Allied Nations’, including the Union Jack, French, and Belgium Flags. Others included the Russian, Italian and Romanian flags.Footnote21 As they served diverse national communities, the embroidered cards were stamped in three languages (‘Carte Postale’, ‘Postcard’, and ‘Postkaart’), such as the butterfly card composed of Allied flags with the caption ‘Longing to See You’, sent by William Bennett to his mother in Kent.Footnote22 Christmas cards were also mounted with a tricolour handkerchief forming a butterfly.Footnote23 Thousands of soldiers sent home butterfly cards, penning brief, personal messages that formed intimate gestures linking the frontline with the homefront. Simultaneously patriotic, domestic, romantic and sentimental emotions were aroused in senders and receivers alike; the dainty fabric touched families and triggered memories of loved ones. They seemed quite exotic to many parents, sisters, brothers and sweethearts, who passed them down through generations of families as precious material memories of honourable service in foreign lands, duty, love and loss.

Furthermore, affection for the butterfly among wounded servicemen may have come from revisiting childhood memories of happier times, such as the hobbies shared among Edwardian boys. Butterflies had been keen attractions in natural history museums, and private collections were regularly sold in auction houses, stimulated by the activities of entomologists and amateur lepidopterists. During the war, local newspapers and juvenile magazines, such as the Boy’s Own Paper, continued to hold collecting competitions and provided colour foldouts on various species.Footnote24 Butterfly collecting was a hobby and enterprise in an era before conservation, as seen in Atkinson’s wing paintings. However, the RSPCA incorporated the butterfly into the wartime culture of caregiving. The charity created its own Butterfly Day to raise funds for sick and war-wounded horses, responding to images of dead horses on the war-torn landscape in illustrated newspapers.Footnote25 The RSPCA campaign sold painted metal butterfly lapel-pins to patrons. Its annual poster of 1918 also stated ‘please support this humane work liberally’.Footnote26 Nature was an emotional cue for compassion towards the innocent victims of war. In this context, the butterfly signified the profound emotional connection between nature and civilized society. The emergence of a more empathic relationship to the butterfly begs the question: did wounded soldiers feel the butterfly as an innocent and fragile creature and a symbol of transient life?

To be sure, the complex natural and iconographic heritage of the butterfly does not wholly account for the way in which the wounded reshaped its symbolism or the degree of artistry and attention to detail accomplished. In one Red Cross sample, a patient embroidered a minute butterfly onto a delicate piece of white voile. The size of half a finger, this butterfly intimates how something ephemeral, inconsequential and incomplete could be enigmatic and meaningful for its maker ().

While recovering in hospital wounded patients had time to reflect on their past youth, perhaps re-imagining a more carefree stage of life, and thus mentally escaping the destruction of the front. The butterfly appears to have sustained many different and deep emotional resonances. Yet, this history of threads and fragments provokes further questions beyond handicrafts and therapies, particularly in relation to other cultural forms where butterflies appear to speak the wounded and war-weary.

‘Tremulous beings’ and the art of soft resistance

As we have seen, the natural world provided a sensory space and emotional release that comforted the wounded. Nature represented a reprieve from the front, whether imaginary or viewed from a hospital window. But many soldier-artists and writers found nature particularly meaningful as a symbol of transience and regeneration. Siegfried Sassoon deployed the butterfly as a metaphor for the fragility of life on the front. Similar to the convalescing embroiderers, he wrote the poem Butterflies while convalescing at Lancaster Gate military hospital in August 1918. Given that he had narrowly escaped court martial for his 1917 letter to The Times accusing the government of prolonging the war, his discontent had become more subdued. The literary device of butterflies allowed the poet to softly resist the militarism with which he had become so disillusioned. Published later in Picture Show (1919), the poem describes butterflies as ‘frail travellers’, likening them to the shell-shocked whose traumatized bodies and minds are ‘as my tremulous being’ (my emphasis).Footnote27

Sassoon wrote Butterflies at the same time as Dedication, a period in which he was both recovering from wounds and struggling with what he referred to as his (sexual) ‘temperament’. In the latter work, he makes an intense proclamation to his lover, of being ‘dedicated’ to ‘your blithe limbs, your steadfast gazing eyes’. Eroticism, desire, and ecstasy are brutally contrasted with the lover’s death in battle; only the poet’s frustrated yearnings survive:

O body’s loveliness that leap’t for joy!

O spirit that burned within, a rose of fire!

They have murdered the voice that was you; and the dreams of a boy

Pass to the gloom of death with a cry of desire

… like a lover slain in sleep.Footnote28

The sensuous and the sensory abound in these two poems. Sassoon wrote to Ogden at the Cambridge Magazine that though his ‘wound had healed, his soul was scarified for ever’, yet his publisher Nichols felt writing had saved the poet from a breakdown (Egremont Citation2005, 214−15). Classically educated, Sassoon understood that the ancient Greek word for butterfly (ψυχή – psyche) meant soul or mind, and was both the name of Eros’s human lover and signified the soul’s metamorphosis in the Christian tradition. Beyond therapy, poetry became a mode of soft resistance against the brutal world order driving the slaughter and suppressing the fulfilment of the poet’s desires. In art, Sassoon could resist the war, give voice to the wounded and grieving, and express the fragile desires of his own ‘tremulous being’.

In their different ways, soldier patients, artists, poets, writers, and film-makers responded to the sensory assault and sensory stimulation of technological war by engaging with the haptic encounter between nature and creativity. For some, the metaphor of the butterfly was its beauty and yearning for escape, and yet its transient lifespan. Significantly, this was reproduced in both the memorial response to mass death and in the subsequent memory culture created after the war, in filmic memory and in memoirs. The butterfly as an emblem of youthful death and yet delicate beauty and sensitive touch was also a symbol for the shell-shocked and the dead, wasted youth.

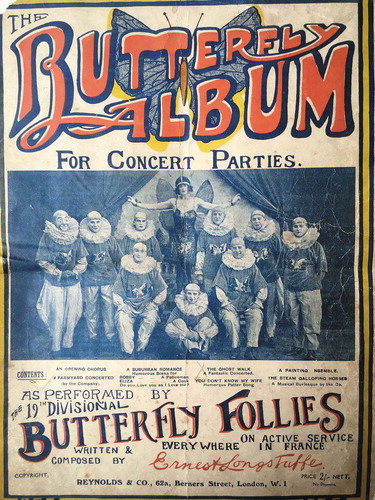

Butterflies emerged and re-emerged as emblems of home, childhood, nation, and humanity in response to the war. They encompassed many aspects such as patriotic passions, the beauty of life and love, and the tactility and sensuality of the flesh, and amplified emotions connected with fleeting life, youthful death, and an unfulfilled future. This was most poignantly demonstrated as the butterfly mascot and moniker of 19th Western Division. They even had their own cross-dressing troupe, the Butterfly Follies, whose concert parties were depicted in their published Butterfly Album for concert parties, sponsored by Major General C.D. Jeffreys, their Commanding Officer. The cover features a photograph of the troupe of Pierrot clowns, wearing sequence butterflies on their costumes. In the middle, as though flying above them, is a female impersonator in a sparkling dress with large butterfly wings and a headband resembling the creature’s antenna (). The pride of the all-male cast was its butterfly girl.

Figure 11. Front cover of ‘The Butterfly Follies’, 19th Western Division, Butterfly Album for Concert Parties. Written and composed by Ernest Longstuffe. Collection of the author.

In addition, the 19th Division’s butterfly insignia was etched onto the crucifix of two roadside war memorials in La Boisselle, the Somme (erected in the 1920s), and Wijtschate, Ypres, near Oosttaverne Wood cemetery in Belgium.Footnote29 Formed in September 1914, the Butterfly Division fought at the battle of Messines in 1917, resulting in the deaths of 51 officers and 1,358 other ranks.Footnote30 The Ypres memorial includes a dedication ‘to the glorious memory of the soldiers of the 19th Western Division who fell in action, near this spot’. Most Divisions designed their own badges to create a sense of belonging and identity, and the 19th Division awarded the ‘white butterfly’ to those who had performed well in combat (Liddle Citation2013, 225), sewn as brassards onto the upper arms of uniforms.Footnote31 Those who survived with wounds were sent to military hospitals where they may have reproduced their butterfly emblem in handicraft therapies or sewed it onto khaki. This material culture was a gesture of pride in service and a way of honouring comrades. Yet, it could also symbolize survival from the trauma of war. Like Sassoon’s ‘frail travellers’ in his poem Butterflies, this icon of nature conveyed the sense of fragile life and transient youth, but also enabled a degree of soft resistance to the violence of industrial war.

Long after 1918, the butterfly endured as a cultural symbol of the war and its legacy. This was explored in Erich Maria Remarque’s international bestseller All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), where butterflies appear several times as an ironic device to amplify the war’s damage, severing the pre-war youth from the wartime man, the past and the present, and the home front from the frontline. On furlough, the soldier Paul Bäumer has become a cynic unable to relate to his family or community. Touching his childhood butterfly collection, in a frame on his bedroom wall, he is overcome with tears. The dead butterflies symbolize his lost innocence after three years of frontline action, and act as a portentous sign of impending demise.

Still further, the novel’s themes of pain, touch and butterflies were seared into the cinematic imagination in Lewis Milestone’s Academy Award-winning film of the same title (1930). A key battle scene depicts two hands severed from the body still gripping the barbed wire. But the climax of the film is reached when Paul attempts to touch a butterfly that has landed near him. A momentary lapse into boyish memories ends with his death by sniper fire. The camera closes in on his hand edging towards the butterfly. The motion is slowed down, accompanied by the sombre sound of the soldier’s harmonica. As Paul’s hand gradually falls lifeless, his transition from life to death is witnessed at close range in this intimate, disembodied scene. Thus, the young man’s death resembles the short-lived existence of the butterfly, which by the 1930s had become a powerful cultural symbol of disillusionment (). In the sensorium of postwar cinema, the butterfly touch became even more illusory than before.

Figure 10. Still from Lewis Milestone (Director), All quiet on the western front (1930, Universal Studios, 150 mins). © Alamy stock.

Stark contradictions of life and death through the metaphors of nature were keenly felt in postwar memoirs. Captain John A. Hayward had been a suburban doctor who served briefly at the British Red Cross hospital at Netley, performing routine operations, before rising to the challenge of battlefield Assistant-Surgeon during the war. In his 1930 memoir, Hayward wrote about his work in the base hospital at Trouville, where, though ‘enjoying myself in field expeditions to collect butterflies and flowers, ...the distant sound of guns was often disturbing’. But when sent to the frontline casualty, his strong emotional and sensory response to the first dramatic day of operating continuously for 36 hours left him ‘completely exhausted with anxiety and fatigue and felt I could never go on with it and was not up to the task’. The next day, Hayward describes walking among the forested rear areas ‘untouched by war’, finding them to be strange in comparison:

…the air was alive with the song of larks and the fields gay with poppies and marigolds and down flowers. The camp and country a picture of peaceful calm and beauty, if only one could forget the scene inside the tents…in the afternoon I was able to leave the operating tent and get out among the birds and butterflies and flowers. It was this walk that saved the situation for me. I got time, alone, to pull myself together… (Purdom Citation1930).

This momentary encounter with nature had a calming effect, relieving him from the strain, and so he began to feel less ‘overwhelmed’ with the ‘panic of my first experience’ of frontline surgery (Purdom Citation1930).Footnote32

Captain Hayward’s memoir was published the same year that the release of Milestone’s All Quiet on the Western Front (Universal Pictures, released in April 1930), with its climax contrived around the butterfly metaphor, was making a major impact across the globe. The film generated critical success in Los Angeles, London and Paris, while also being subjected to aggressive National Socialist protests in Berlin. To be sure, it signalled an international cultural turning point in discussions about war disillusionment and the visualization of its terrible contrasts. Similarly drawn to the 'violent contrasts' of war, and also part of this cultural turning point, was the publication of Hayward’s memoir. In one scene, he describes operating on a group of soldiers dressed up as female impersonators, as they had been performing in a hospital pantomime when it was bombed during the show. He concludes:

It was these violent contrasts that, to me, make up the vivid memories of my days in France. Outside, the sun and the larks, the birds, butterflies, and flowers: inside the tents, Nature violated, outraged … Alternating with the dread and anxiety and physical and mental exhaustion was the happy mess and bridge, picnics, and concerts. (Purdom, Citation1930)

Publishing his memoir in 1930 situated Hayward in this wider culture of postwar reckoning and the continued importance of creativity in the arts in addressing the war’s legacy and searching for its meaning. Through many different cultural forms, nature served as a powerful metaphor of suffering and loss, while continuing to provide solace from troubling memories and recurring emotions.

The healing powers of art and nature are particularly salient in the story of Adrian Hill, a British serviceman who witnessed the horror of war first hand and struggled with gas wounds, and became one of the first Official War Artists before being hospitalized with Spanish flu and a bout of tuberculosis. Yet, Hill’s later discovery of the recuperative power of nature led him to become the leading proponent of art therapy in the interwar period.

While attending art school, Hill had tried to enrol in the Artists’ Rifles, but instead became an Officer with the Honourable Artillery Company assigned to the Western Front between 1915−1919. Between 1917 and 1918, he made approximately 180 ink and wash drawings of bombed landscapes strewn with blackened tree-stumps and wrecked weapons, as well as ruined villages, and dead soldiers’ bodies.Footnote33 Though these stark scenes dominated his ‘visual attitude’ where ‘everything suffers’, Hill transformed his own traumatic visual memories into the healing power of art and nature (Hill Citation1975). After visiting the old frontline in 1928, he, just as Captain Hayward had, encountered the skylarks above the rubble, which triggered his sensory memory of the war and his reflection on the absurdity of life and beauty when surrounded by death (Hill Citation1975).

Soon after, Adrian Hill began to sketch and paint gardens, farms, villages, trees, and tranquil landscapes. In this manual On Drawing and Painting Trees (Citation1936) he described ‘Nature’ as the ‘inspiration of the artist’ and its ‘rewarding joy’ (Hill Citation1945, ix). The haptic and imaginative practice of making art, he believed, could underpin a new therapy, but not one intended for distraction or to augment an occupation. Crucially, it was not ‘hackneyed views of nature’ he sought (Hill Citation1945, 53). Instead, art therapy would release creativity for its own sake, unlock sensory and affective emotions and instil a sense of peace and beauty via the creative hand in touch with nature (Hill Citation1975).Footnote34 By developing the healing power of creativity in haptic art forms, Adrian Hill elevated the artistic aspect of rehabilitation that had been overshadowed by the emphasis on work therapy and recovering lost masculinity.

Conclusion

This paper has addressed a remarkably overlooked aspect of rehabilitation in historians' acounts of medicine and culture in the wake of the First World War. It has emphasised the importance of the ‘haptic arts’ in expressing the embodied and sensory impact of the war through cultural means. Occupational therapy, I argued, was a key component of rehabilitation, however, this cultural factor goes well beyond the historiographical focus on labour, work and masculinity. Moreover, the appeal of natural themes in these therapies – flora and insects (particularly the butterfly) – not only suggested a deep connection between the senses and the arts, but registered as modes of agency and soft resistance. Thus, I argued, when wounded men addressed their traumatic experiences by turning to nature, they sought a remedy for the physical and emotional pain of the war.

In particular, this paper has revealed how the butterfly became a ubiquitous motif in occupational handicrafts, as well as other artistic and cultural forms, including war memorials, and was deployed as both a therapeutic and a mnemonic device. I argued that the butterfly was a unqiuely placed emblem relating to human touch and emotion, and linked the natural world to sensations such as fragility, beauty and transience. At this time, the rehabilitation industry also supported a myth that blind veterans could acquire special tactile capacities. Yet, the wounded testified that creative activities in the arts and crafts countered the brutality of modern war, softly resisting physical and emotional suffering, and providing a remedial effect through a wide range of cultural practices. Contributing to the discipline of history, this research proposes that through these fragmentary glimpses into haptic gestures associated with material culture, a different kind of emotional and sensory history can be written against the grain of the grand narrative. By using interdisciplinary methods this paper has underlined how the colossal and catastrophic events of the world war could be healed through small, creative gestures of the human sensorium, which combine to form meaningful motifs of cultural significance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. See Wellcome Images V0017134: Wellcome Library, London.

2. See also R. Fortescue Fox, Physical Remedies for Disabled Soldiers, Bailliere, London, 1917. He discusses the re-education of the blind masseur with photographs provided by Major Tait McKenzie from his paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, July 1916.

3. In 1919, the Association of Blind Certified Masseurs was formed which provided training for the war blind.

4. By the 1930s blind osteopath Captain Gerald Lowry felt compelled to dispel the myth of the ‘acquired gift’ of sensitive touch, instead of arguing the ‘sixth sense’ was simply the ‘revivification of a dormant sense’. He emphasizes the blind man’s need for masculine ‘determination to conquer’ blindness and overcome the ‘mental suffering’ associated with the ‘dread’ of dependency. (Lowry Citation1933, 2, 25).

5. See ‘Home Sweet Home. And England For Ever’. http://www.nam.ac.uk/online-collection/detail.php?acc=1952-04-118-1.

6. The full song is ‘Australia Will Be There’: ‘Rally round the banner of your country/Take the field with brothers o’er the foam/On land or sea where ever you be/Keep your eye on Germany/But England, home and beauty/have no cause to fear/Should auld acquaintance be forgot?/No! No! No! No! No!/Australia will be there/Australia will be there’. Australian War Memorial collection. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL34171/.

7. Australian War Memorial collection, NX1206. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/REL48023/.

8. British Red Cross collection, London.

9. British Red Cross Archive, Ref 1642/2. The embroiderers are: R.G.Clark 1923, 166 Labour Corps; H.Rose, 1st Wilts; PNS A.E.Watkins, 1 Dorset; F.Harwood, 15th Kings Huzzars; J.Amey, 5th Dorsets; A.H.Taylor, Roy West Surrey Regt; Pens. A.E.Watkins, 1st Batt. Dorset; ‘There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance’ (centrepiece); H.Welch; 1st Batt. Welsh Guards; J.T.Giles, Grenadier Guards; A.Lloyd 6th Som. L.I.; E.Bence R.E.; F.Collins 1/5th Devons; A.Crane 2nd K.O.Y.L.I.; G.T.Pitman 10th Glos’ters; Pens. A.E. Watkins 1 BORSTS; Embroidered by wounded men in the Pensions Hospital, Bath, 1923 G.H.Grisbourne R.A.F (lower piece).

10. The Lancet, November 1916, 188, no. 4864: 867−8.

11. At the No. 16 Canadian General Hospital (also known as Ontario Military Hospital), Orpington (opened February 1916 with 1000 beds): ‘Some of the men have become expert in the art’, The Sphere, 1917.

12. Private Walter John Cressey (‘A’ Company, 18th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment) produced. He had lost four fingers and was blinded by gassing, but reached a level of artistry in the design of necklaces IWM collections: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30081541.

13. Thanks to Elen Philips, at the Museum of Wales.

14. Mary Greg collection 1922.1861 Gallery of Costume. Manchester Art Gallery. Thanks to Miles Lambert and John Peel at the Gallery of Costume for their assistance.

15. The Evening News, (Rockhampton, QLD) featured him in photographs and described his artistic process of selecting old butterfly collections, using an old microscope to detect parasites and treating the wings in a chemical solution, and then applying them to the designs on paper (3 March 1931). The works ranged in size from 5ft to 5 inches square. He started in 1920 and had made over 1,000 pictures. Some butterflies came from Devonshire, some were imported from Africa and South America, and others he located in collections from the 1870s. A 5ft square portrait of Catherine of Aragon was composed of 2800 wings (The World’s News, Sydney, Sat 21 August 1926).

16. ‘Novel Pictures. Artist Uses Butterfly Wings. Purchase by Queen’, The News, Adelaide, Feb, 1921; the Newcastle Sun, 2 August 1927. He also made a portrait of Princess Elizabeth with 1800 butterflies costing £39.00, which was shown to the Duchess who purchased it (Toodyay Herald, WA, 3 August 1928).

19. See Judith Pettigrew, Katie Robinson, Stephanie Moloney, ‘The Bluebirds: World war I soldiers’ experiences of occupational therapy’, American Journal of Occupational Therapy, January/February, 2017, vol 71, no. 1, Figure 1.

21. AWM collection, C1209190; https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C268225‘. Or an orange and blue butterfly with ‘A Kiss from France’ and a woman wearing a shawl on the other side, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C973612).

22. Object 4185, Oxford University Great War Archive and Europeana sites.

23. 1914−1918 Christmas Card text: ‘Wishes winged with loving thoughts for a Happy Christmas’, M379, Wolverhampton Arts and Museum Service, http://blackcountryhistory.org/collections/getrecord/WAGMU_M379/.

24. ‘The war on butterflies’, Western Gazette, Somerset, 21 Sept, 1917; ‘War on Butterflies’, Surrey Advertiser, Surrey, 20 October 1917; The Boy’s Own Paper magazine, June 1918 (Religious Tract Society: London 1918).

25. ‘With the horse on the Western Front: special equine section of The Sphere’, 10 February 1917, 122. Photos were titled: ‘The last of a trusty worker’, ‘Grave of two horses’, and ‘Fallen by the wayside’.

28. As cited in Max Egremont Citation2005, 214–215.

29. The inscription on the Divisional memorial at La Boiselle reads: ‘Butterfly/To the Glorious memory/Of the soldiers of the 19th Western Division/Who fell in action in the battle of the Somme/Between July 2nd and 20 November 1916/La Boisselle – Bazentin le Petit – Grandcourt’.

30. See Imperial War Museum collection photograph: Q46017. It commemorates the 19th Division Royal Artillery, Royal Engineers, RAMC, and 5th Batt South Wales Borderers (Pioneers).

31. See Imperial War Museum ephemera collection, INS 14,636. Note also that the official ship badge of the light cruiser HMS Inconstant (1914 and in service at Jutland) was a gold butterfly from 1919, and the naval destroyer HMS Vanessa’s was a blue butterfly from 1918–1919 (see the National Maritime Museum collection).

32. John A. Hayward. M.D., F.R.C.S. 1914−1915. Assistant-Surgeon British Red Cross Hospital, Netley. 1915−1917, Medical Officer, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Roehampton. April to November 1918, Temporary Captain R.A.M.C, B.E.F. The memoir is published in C. B. Purdom (ed), Everyman at War, 1930: http://www.firstworldwar.com/diaries/casualtyclearingstation.htm.

33. Works include, Ruins: Between Bernafay Wood and Maricourt; Wrecked Tank, C1 at Pozieres; A Wrecked Gun Mounting, Zonnebeke Ridge, Ruins of Mametz Church, Peronne, the Main Street, 1918; A View in Albert, 1918; The Railway Hotel, Arras, 1918. See the Imperial War Museum collection website for detailed illustrations.

34. Adrian Hill sound archive 561, (IWM).

References

- Anderson, J. 2011. War, Disability and Rehabilitation: The Soul of the Nation. Manchester: University of Manchester Press.

- Anderson, J. A., and N. Pemberton. 2007. “Walking Alone: Aiding the War and Civilian Blind in the Interwar Period.” European Review of History 14 (4): 459–479. doi:10.1080/13507480701752128.

- Auslander, L., and T. Zahra, ed. 2018. Objects of War. The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Beatrice D. 1921. British Medical Journal. 7 May 1921. 1 (3149):680−81.

- Bourke, J. 1996. Dismembering the Male: Men’s Bodies, Britain and the Great War. London: Reaktion Books.

- Bush, R. 1930. “Coo-Ee’s Dedication.” In A Short History of the Bishop’s Knoll Hospital, edited by A. G. Powell. Bristol: Vandyck.

- Calder, J. 1982. The Vanishing Willows. The Story of Erskine Hospital. Renfrewshire: Princess Louise Hospital.

- Carden-Coyne, A. 2008. “Painful Bodies and Brutal Women: Remedial Massage, Gender Relations and Cultural Agency in Military Hospitals, 1914−18.” Journal of War and Culture Studies 1 (2): 139−58. doi:10.1386/jwcs.1.2.139_1.

- Carden-Coyne, A. 2009. Reconstructing the Body: Classicism, Modernism and the First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carden-Coyne, A., D. Morris, and T. Wilcox, eds. 2014. The Sensory War, 1914−1918. Manchester: Manchester Art Gallery Press.

- Classen, C. 2012. The Deepest Sense: A Cultural History of Touch. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press.

- Cohen, D. 2001. The War Come Home: Disabled Veterans in Britain and Germany, 1914-1939. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Dark, S. 1922. The Life of Sir Arthur Pearson. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Dawson, G. 1994. Soldier Heroes: British Adventure, Empire and the Imagining of Masculinities. London: Routledge.

- Delaporte S. 1996. Les Gueules cass#xE9;es: Les bless#xE9;s de la face de la Grande Guerre. Paris: No#xEA;sis...

- Doan, L. 2013. Disturbing Practices: History, Sexuality and Women’s Experience of Modern War. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Egremont, M. 2005. Siegfried Sassoon: A Biography. London: Picador.

- Feudtner, C. 1993. “Minds the Dead Have Ravaged: Shellshock, History and the Ecology of Disease Systems.” History of Science 31 (14): 377−420. doi:10.1177/007327539303100402.

- Furneaux, H. 2016. Military Men of Feeling: Emotion, Touch and Masculinity in the Crimean War. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- G.Y.P. 1916. “Cobbers.” Cooee 1 (11).

- Gagen, W. 2004. “Disabling masculinity: Ex-Servicemen, disability and gender identity, 1914−1930.” unpublished PhD, University of Exeter.

- Gagen, W. 2007. “Remastering the Body, Renegotiating Gender: Physical Disability and Masculinity during the First World War.” European Review of History 14 (4): 525–541. doi:10.1080/13507480701752169.

- Gehrhardt, M. 2015. The Men with Broken Faces: “Gueules Cassees” of the First World War, Peter Lang.

- Gerber, D. A. 2000. Disabled Veterans in History. Michigan University Press.

- Gray, T. 1821. The Poetical Works of Thomas Gray. London: John Sharpe.

- Hickman, C. 2009. “Cheerful Prospects and Tranquil Restoration: The Visual Experience of Landscape as Part of the Therapeutic Regime in the British Asylum, 1800−1860.” History of Psychiatry 20 (4): 425−41. doi:10.1177/0957154X08338335.

- Hickman, C. 2013. Therapeutic Landscapes: A History of English Hospital Gardens since 1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Hill, A. 1936. On Drawing and Painting Trees. London: Littlehampton books.

- Hill, A. 1945. Art versus Illness. A Story of Art Therapy. London: Allen and Unwin.

- Hill, A. 1975. Imperial War Museum Sound Archive, 561.

- Hitchcock, L. no date. “The Great Adventure.” Unpublished manuscript. Hitchcock and Angier collection, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Washington DC.

- Jones, E. 2010. “Shellshock at Maghull and the Maudsley: Models of Psychological Medicine in the UK.” Journal of the History of Medicine 65: 386.

- Jones, E., and S. Wessely. 2005. Shellshock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Kinder, J. 2015. Paying with Their Bodies: American War and the Problem of the Disabled Veteran. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Knopf, S. A. M. D. 1918. “Blinded Soldiers as Masseurs in Hospital and Sanatoria for Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of Disabled Soldiers.” Annals of the American Academic of Political and Social Science 80: 111−16. doi:10.1177/000271621808000117.

- Lambert, F. B., Dr. November 1916. Lancet 4: 788–789. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)99226-2

- Laws, J. 2011. “Crackpots and Basket-Cases: A History of Therapeutic Work and Occupation.” History of the Human Sciences 24 (2): 65−81. doi:10.1177/0952695111399677.

- Leese, P. 2002. Shellshock: Traumatic Neuroses and British Soldiers of the First World War. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Liddle, P.H. 2013. Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third battle of Ypres. Barnsley: Pen and Sword.

- Linker, B. 2011. War’s Waste: Rehabilitation in World War I America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Little, M. E. 1922. Artificial Limbs and Amputation Stumps. A Practical Handbook. London: H.K. Lewis.

- Longmore, P. K., and L. Umansky, eds. 2001. The New Disability History: American Perspectives. New York: New York University Press.

- Lowry, G. 1933. From Mons to 1933. London: Simpkin and Marshall.

- McBrinn, J. 2016. “The Work of Masculine Fingers: The Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry, 1918−1955.” Journal of Design History 21: 1–23. doi:10.1093/jdh/epw043.

- Meyer, J. 2009. Men of War: Masculinity and the First World War in Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mitchell, L. 2017. ‘Treasuring Things of the Least’: Mary Hope Greg, John Ruskin and Westmill, Hertfordshire. York: Guild of St. George Publications.

- Morris, M. S. 1997. “Gardens ‘For Ever England’: Landscape, Identity, and the First World War British Cemeteries on the Western Front’.” Ecumene 4 (4): 411−34. doi:10.1177/147447409700400403.

- Novotny, J. 2017. “Vocational Rehabilitation of WW1 Wounded at Erskine.” unpublished conference paper, Veterans’ activities and organisations of the First World War in the UK and Beyond, 18 March 2017, University of Edinburgh.

- Paterson, M. 2006. “Seeing with the Hands: Blindness, Touch and the Enlightenment Spatial Imaginary.” British Journal of Visual Impairment 24 (2): 52−9. doi:10.1177/0264619606063399.

- Pearson, A. 1919. Victory over Blindness: How It Was Won by the Men of St. Dunstan’s and How Others May Win It. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Perry, H. 2014. Recycling the Disabled: Army, Medicine and Modernity in WWI Germany. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Purdom, C. B., ed. 1930. Everyman at War: Sixty Personal Narratives of the War. London: J. M. Dent.

- Rachamimov, I. 2018. “Small Escapes: Gender, Class and Material Culture in Great War Internment Camps.” In Objects of War. The Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement, edited by L. Auslander and T. Zahra, 164–188. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- Reid, F. 2012. Broken Men: Shellshock, Trauma and Recovery in Britain, 1914-1930. London: Continuum.

- Reiss, M. 2015. Blind Workers against Charity: The National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland, 1893−1970. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reznick, J. 2011. The Culture of Caregiving. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Roddy, S., J. Strange, and B. Taithe. 2018. The Charity Market and Humanitarianism, 1870-1912. London: Bloomsbury.

- Scates, B., and M. Oppenheimer. 2016. The Last Battle: Soldier Settlement in Australia, 1916-1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- The Lancet. November 1916. 188 (4864): 867−8. 1920, 17 April, 886.

- The war on butterflies. 1917. Western Gazette. Somerset. 21 September 1917.

- Tilley, H. 2014. “Introduction: The Victorian Tactile Imagination.” Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century 19: 1−20.

- Van Bergen, L. 2009. Before My Helpless Sight: Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Verville, R. 2018. War, Politics and Philanthropy: The History of Rehabilitation Medicine. Maryland: University Press of America.

- Verstraete, P., and Van Everbroeck C. 2018. Reintegrating bodies and minds: Disabled Belgian Soldiers of the Great War. Antwerp: ASP editions.

- War on Butterflies. 1917. Surrey Advertiser. Surrey. 20 October 1917.