ABSTRACT

This article contributes to literature in IR and critical military studies on embodied experiences, military geographies, and research on rangers. Despite being a common feature of military training, little research exists on how the military uses outdoor training to shape soldiers’ identities, emotions, and embodied dispositions. In contrast to existing scholarship’s emphasis on using and constructing outdoor environments in military training to transmit values and skills to make soldiers tough, I argue that outdoor training should be examined from its wealth of embodied experiences and the becoming it gives rise to. Exploring written memoirs by Swedish Norrland Rangers in annual ranger journals on their embodied experiences of extensive outdoor training in north Sweden, the article traces how these rangers represent outdoor training as an assemblage of challenging and pleasurable experiences of being entangled with the northern geographies. The findings indicate that Norrland rangers actively nurture an affirmative orientation to the outdoors and Arctic geographies through their representations of outdoor training, making the challenging ranger formation a rewarding becoming. By developing how rangers constitute and foster this affirmative orientation through their writings, the article provides a better understanding of how pleasurable feelings and experiences of the outdoors are nurtured and drawn upon to socialize rangers.

Introduction

This article explores memoirs and images by Swedish Norrland Rangers (Norrlandsjägare)Footnote1 in two annual ranger journals, Blå Dragonen and Lapplands Jägare, from 1968–2022 (with a gap between 2008 and 2019) on their embodied experiences of extensive outdoor training in the arctic environments of north Sweden. Representations of rangers in popular culture and information material (DoD Citation2007; SAF Citation1974) depict rangers, in particular Norrland Rangers (Eriksson Citation2016), as a military force submerged in wild environments, with ‘the nature and its demands’ being ‘the [ranger] education’s most important ingredient’ (KBD Citation2010, foreword). The physical criteria to apply to become a Norrland Ranger are demanding.Footnote2 In a three-month basic conscription training followed by eight months of special training, comprising four weeklong outdoor ‘ranger exercises’, Norrland rangers train survival skills, trekking, climbing, skiing, and irregular warfare (SAF Citation2023a).

Despite being a common feature of military training and in representations of how soldiers are formed, not least rangers, how soldiers become entangled with training environments and their emotional and physical experiences from outdoor training have, with some exceptions (Hockey Citation2009; McSorley Citation2016; Woodward Citation1998, Citation2000), been little researched. A common understanding in this literature is that soldiers are formed in and by the environment by being subjected to the ‘multiple challenges provided by the natural environment’ (McSorley Citation2016, 108) to learn to achieve ‘victory’ over its demands (Woodward Citation1998), learning to move in and to read the environment as a ‘terrain’ (Hockey Citation2009) through an embodied ‘rationalistic’, militarized gaze (McSorley Citation2016; Woodward Citation1998).

While this focus on environments and training in them as mediums for discipline and the forging of military ‘sensory capacities, attunements and regimes’ (McSorley Citation2020), and hegemonic masculinities (Woodward Citation2000), bring into view recurrent features of the relations between bodies, environments and affects in the making of soldiers, they emphasize a fairly linear understanding of causality between environments and bodies. In this understanding, one assumes that armed forces use and construct environments to transmit values and skills, aiming ‘to reconfigure body-selves towards the functional imperatives of military objectives’ (Higate Citation2013, 114). In this article, I challenge this understanding by examining the complex entanglements between environments, affects and bodies that Norrland Rangers detail in their writings. Rather than assuming that outdoor training turns around using and constructing environments as mediums of instrumental transmission of values and skills with the primary aim of making rangers ‘tough’, Norrland ranger texts on outdoor training, I argue, should also be examined from how they represent multiple experiences and becomings from outdoor training. These multiple experiences and how they acquire ways of relating to them should be read as a socialization to at once be able to operate effectively in the arctic environments and to cultivate a particular taste for the outdoors. I also argue that by exploring how they represent experiences of joy and pleasure on the one hand and challenges or sore bodies from ranger outdoor training on the other hand in these memoirs, we can get a better understanding of what happens during outdoor training, of its meanings for Norrland rangers and how these experiences are drawn upon in the making of ranger identities. We can thereby understand how desire-infused becomings and military forms of socialization through the outdoors are entangled with disciplinary aims and techniques to make rangers ‘tough’ in the making of this military force. Researching these texts, which describe outdoor training in north Sweden, also constitutes an empirical contribution to literature on how training environments are used to shape soldiers and scholarship on military geographies and landscapes.

The proposed exploration builds on and seeks to contribute to a growing scholarship in IR and critical military studies on the wealth of embodied and affective experiences of war and military training (Ahall and Gregory Citation2015; Basham Citation2013, Citation2015; Danielsen Citation2018, Welland Citation2018; De Lauri Citation2021; Dyvik Citation2016b; Hockey Citation2009; McNeill Citation1995; McSorley Citation2013, Citation2016, Citation2020; Randrup Pedersen Citation2017; Sylvester Citation2013). This research suggests that how bodies are attracted to, affected by, react to or handle embodied experiences of war and training needs to be researched from people’s experiences (Sylvester Citation2013, 6). A strand in this literature relevant to this article’s exploration of representations of outdoor ranger training foregrounds the entanglements of pleasure and joy with exhausting or challenging experiences (McNeill Citation1995; Dyvik Citation2016b; Randrup Pedersen Citation2017; Welland Citation2018). The historian William McNeill’s (Citation1995) account of his intriguing, embodied experience of drill illustrates well this literature’s relevance for the proposed study:

Something visceral was at work … Words are inadequate to describe the emotion aroused by the prolonged movement in unison that drilling involved. A sense of pervasive well-being is what I recall; more specifically, a strange sense of personal enlargement, a sort of swelling out, becoming bigger than life, thanks to participation in collective ritual. (2)

Engaging in plural experiences of war and military training, other contributions to this literature have explored memoirs of war as an ‘assemblage of pleasure and pain’ (Dyvik Citation2016b), engaged in the coexistence of war and fun (De Lauri Citation2021), and in soldiers’ thrilling attraction to war as an ‘existential desire for the real’ (Randrup Pedersen Citation2017), as well as engaged in the coexistence of joy and pain as essential for understanding how people ‘survive, sustain and resist war’ (Welland Citation2018, 438). Resonating with this literature’s desire to ‘engage in the full range of experiences and emotions in war’ (Welland Citation2018, 440), examining how Norrland Rangers represent multiple bodily experiences from outdoor training is essential for a better understanding of how they transmit ways of relating to the outdoors, and desire associated with it, as part of being socialized to become a ranger and training irregular warfare.

By engaging in how these texts construct arctic geographies in accounts of the haptic interactions between bodies and environments and how these constructions frame the meaning of these experiences and geographies for them as rangers, the article also contributes to research on military geographies and military landscapes (Woodward Citation2004, Citation2014). It does so by exploring how the Arctic North is constructed and tracing how these writings describe the environments’ affordances to incite emotions and sensations during training. This is important for a better understanding of ranger training as an experience during which the ranger body participates in multiple sensations and attunements that shape micro-becomings that coexist with their overall ranger-becoming.

Finally, the analysis also has a potential impact on the Norrland Rangers themselves. It gives insights into the close relations between outdoor culture and military training in ranger education and the performative acts of writing and training that reproduce this hybrid outdoor-military culture and identity.

The article first contextualizes the proposed exploration by developing how existing research describes military uses and constructions of outdoor environments in military training. To contextualize the contribution further, it then develops a section on research on rangers, after which it describes Norrland rangers, the material, and methodological considerations. Drawing on memoir material, the analysis is divided into two focuses on how rangers make sense of their embodied outdoor training experiences. The first focus details the physical interactions between bodies and environments and the emotions and micro-becomings from this training. The second analyses the rangers’ framing of their relations to the environments and the construction of specific meanings of outdoor training and the arctic geographies. The article ends by discussing the findings and their implications for research on embodied experiences of training and war, ranger research, military geographies and the rangers themselves.

The environment as a medium for the making of soldiers

Existing research on using environments in military training has observed that ‘Military training requires learning very particular ways of being in specific spaces and typically involves the subjection of the body to multiple challenges provided by natural environments’ (McSorley Citation2016, 108). In this process, the outdoors is ‘the key medium through which the potential of bodies to assume military fitness may begin to materialise’ (107–108). Environments are, among other things, used to make militaries fit (McSorley Citation2016) and to prepare them for the requirements of infantry warfare (Hockey Citation2009; Woodward Citation1998). At war, Derek Gregory (Citation2016) has noticed how ‘nature’ is constructed and used as ‘a modality that is intrinsic to the execution of military and paramilitary violence’ with ‘the body’s apprehension of the battlefield’ always being ‘more than visual … affective, corporeal, material and a matter of knowledge’ (4). This literature foregrounds the affective and material attunements to environments as essential for modern warfare. Moreover, outdoor training and constructions of environments for military training are also used to encourage recruitment and foster teamwork and military identities (Woodward Citation1998, Citation2000). However, apart from Rachel Woodward’s (Citation1998; Citation2000) research on the making of rural military masculinities through training in British outdoor environments, there are few explorations of embodied experiences of how environments affect military bodies and identities during training and how armed forces represent outdoor training. Analysing recruitment material, Woodward at once traces a ‘rationalistic’ relation between military senses and the environments, in which soldiers learn to transform the environment into terrain, to view it as something that the male soldier needs to ‘transcend’ (1998, 293), while images of ‘outdoors adventure’ affectively encourages him to join the armed forces (291). Analysing senior military personnel’s accounts of the rural as a medium for the making of masculine soldiers, Woodward contends that in these accounts:

the great outdoors is a place for survival rather than pastoral contemplation, a place of potential hazard and danger rather than a leisured landscape. It is certainly not the rural idyll of community and nature in harmony, perhaps imagined by a largely urban body of recruits.

In Woodward’s study, the British army is shown to construct its rural training environments as the location for emotions of ‘fear, excitement and sense of challenge’, which are first stimulated and later overcome by ‘acquiring the necessary mental attributes’ (650). In summary, Woodward’s analysis foregrounds how the rural is a medium through which ‘specific values associated with the model of military masculinity are transmitted to the soldier’ (650).

As argued above, I wish to broaden this understanding by also examining emotions and experiences of outdoor training and ways of constructing the outdoors that exceeds existing research’s assumptions of how soldiers are shaped through outdoor training and how they frame these experiences. This broadening is also empirical since engaging in texts on training from a different geographical and cultural context entails engaging in other representations, emotions and values associated with ‘wilderness’ (see Woodward Citation2000, 652, footnote 2). Such an exploration makes it possible to trace forms of socialization that are at stake beyond uses and constructions of the environment to make rangers ‘tough’, enabling a better understanding of the broader experiences of outdoor training and the relations between these and the formation of Norrland Rangers. The following section develops existing research on rangers to further contextualize the study’s contribution.

Ranger research

Research on rangers has focused on the making of their cultural, regional, and gendered community, which varies according to national contexts and local histories (Alvinius, Larsson, and Larsson Citation2016; Bahmanyar Citation2005; Caraccilo Citation2015; Danielsen Citation2018; Ruffa Citation2015). Literature on American Army Rangers reproduces representations of these rangers as ‘shadow warriors’, heroic and associated with being enduring and tough, with an assumed continuous history from the 18th century until today’s special forces. Another emphasis in this literature is their strategic importance in modern conflicts since World War II (Bahmanyar Citation2005; Caraccilo Citation2015; DoD Citation2007). By contrast, research that takes an interest in how the identities of rangers have been shaped foregrounds the importance of local histories for their communities, political identities, cohesion, the reproduction of masculinity, and military performance (Alvinius, Larsson, and Larsson Citation2016; Danielsen Citation2018; Ruffa Citation2015).

On the relations rangers have to their operating environments, in contrast to French Chasseurs Alpins or British Royal Marines, which are known for military effectiveness, Chiara Ruffa notes that Italian Alpinis prioritize ‘skiing and climbing skills and mere survival over fighting’ (Ruffa Citation2015, 262). Being oriented towards the mountains is central to the Italian Alpini identity. This unit historically recruited local men based on the conviction that ‘profound knowledge of territory was much more important than conventional military skills’ (Ruffa Citation2015, 254). Ruffa also notes the Alpinis’ awareness and valuing of the need to cultivate embodied knowledge of the environment by quoting an interview with an old Alpini by Gianni Oliva in Storia degli Alpini (2001, 21):

Whoever has wandered around for long through the mountains shall have realised how, among these, that remarkable book called terrain is extremely difficult to read; for reading it correctly it is necessary to get used to it: the practical knowledge of the terrain that has to be defended can be acquired only by manoeuvring over it and considering all the foreseeable options. [lit. ipotesi hypotheses].

In contrast to Ruffa’s historical focus on the political and local identities of Alvinius et al. Citation2016) exploration of masculinity constructs of Swedish rangers and Tone Danielsen’s (Citation2018) ethnography of the making of Norwegian marinejeger focus on ranger masculinity norms. Based on interviews with Swedish Norrland rangers, coastal rangers, and parachute rangers, Alvinius et al. (Citation2016) explore how these different rangers reproduce ‘the masculine image of the ranger’, which, they argue, is ‘manly’ but not ‘macho’ (45). They show that rangers in Sweden do so by establishing an ‘emotional regime’ through the building of social identity and cohesion and by observing symbols and rituals. In contrast, Danielsen ethnographic study provides a rich participant observation account of the closed world of Norwegian marine rangers and their making. Danielsen examines Norwegian marine ranger education as a rite and the motives for going through this training, emphasizing how their relations and community are constructed through specific norms of masculinity. Importantly for this article, following van Gennep’s (Citation1960) division of rite of passages into three phases – the separation phase, the liminal phase and the incorporation phase – Danielsen foregrounds how intense outdoor training early in the formation, including a ‘hell week’, constitutes a rite of passage. This rite, Danielsen shows, aims at separating marine ranger conscripts from their civilian life, after which they endure outdoor training in a liminal phase, to finally be incorporated in the ranger community through an ending outdoor ‘beret run’ (Danielsen Citation2018, 63–64). Similar rites, including an outdoor march, have also been noted for other special forces, for example, the ‘Long Drag’ for SAS training in Britain (Woodward Citation1998, 287–288).

In contrast to Ruffa’s focus on the local identity of Alpinis, these accounts reveal the designing of ranger formations as a rite of passage through which outdoor training forges the embodied capacities, the sense of community and embodied identities of these units. Ranger rites of passage are often symbolized by earning the beret through a weeklong march, with the beret functioning as a ‘sacred bond’ between those who have earned it (van Gennep Citation1960), 166). Echoing Alvinius et al. (Citation2016), who note that ‘For rangers, rituals and symbols fulfil a number of purposes, having an empowering effect in the face of a demanding task and they facilitate mental preparation and increased group cohesion’ (42), the beret can be assumed to increase group attraction among initiates who, after a common challenging initiation, wear it with pride (Aronson and Judson Citation1959).

Historically, armed forces recruited rangers from local rangers and hunters who were experts at ambushes, skirmishing and reconnaissance (Caraccilo Citation2015; Danielsen Citation2018, 35; DoD Citation2007). In contrast to the continuous local recruitment of Alpinis, recruitment in Norway has shifted from recruiting northern, often working-class men who already mastered the physical requirements and outdoor skills to increasingly attracting mostly upper-middle-class men, also from southern parts of Norway, with an interest in the outdoors. This has increasingly made ranger education into a status-filled achievement. Central to these recruits is a shared understanding of national identity as an egalitarian ideal of enjoying and having public access to outdoor life (Danielsen Citation2018, xvi-xviii). It is assumed that similar changes have also occurred in Sweden, where being physically active and having public access to outdoor life (the so-called ‘Allemansrätten’) are central to national identity (Thurfjell Citation2020).

This research indicates the close relations between outdoor culture and the formation of a specific military capacity and identity that draws upon and reinforces those cultural values and leisure interests. To further contextualize the focus on rangers, the following section describes Norrland rangers, the regiments, and their deployment history.

Norrland Rangers

The generic term ‘Norrland Ranger’, as used here, denotes a type of ranger that has been formed in two different regiments in Sweden, at K4 in today’s Arvidsjaur and at I22 in Kiruna from 1945–2000. The rangers at I22 were called Lapplandsjägare (Lapland Rangers). Despite geographical and regiment differences, Norrland Rangers (K4) and Lapland Rangers (I22) were trained in similar arctic environments and through almost identical training (Wikipedia Citation2023a, Citation2023c).

Norrland Rangers at K4, which is a dragoon regiment, was historically a cavalry that originated from the armed forces’ recruitment of local horsemen in Jämtland in the 17th century (SAF Citation1974). Until 1980, K4 was based in Umeå before it was moved to Arvidsjaur. In 2005, K4 was disbanded when the Swedish Armed Forces closed several regiments, but it was set up again in 2020 due to changed threat perception in the aftermath of the Russian seizure of Crimea and Donbas in 2014 (Wikipedia Citation2023b). In 2025, 300 conscripts per year will be educated at K4. The regiment aims to grow from 500 to 1600 rangers (Derland Citation2022).

Today, Norrland Rangers are organized in a light infantry battalion, consisting of one battalion that, by 2025, will be expanded to two battalions. The battalion consists of ranger squadrons and squadrons that support the rangers with operational logistics. There are also subdivisions among the rangers, such as the mountain platoon and the international platoon (Wikipedia Citation2023b). In contrast to marine rangers, according to the Swedish Armed Forces (SAF), Norrland rangers are specialists at long-term dissimulation in vast arctic environments, ranging from mountains to swamps and forests, with capacities to operate over great distances in environments ‘lacking infrastructure’. In the context of Swedish defence strategy, these units aim to operate behind enemy lines to create significant friction to an enemy less adapted to the environment, thereby slowing down or breaking an enemy advance (SAF Citation2023b).

Norrland rangers have been deployed in Kosovo in the 1990s, in Afghanistan between 2007–2009, in Mali in 2017, and to train Iraqi soldiers in the 2010s (Wikipedia Citation2023b). It cannot be assessed here how these deployments have affected the rangers’ perceptions of themselves. However, these are assumed to have increased the rangers’ status vis-à-vis other branches of the armed forces and reinforced their conviction that they constitute a necessary military force.

Lapland Rangers in Kiruna were organized in light infantry companies that originated from a ‘ski troopers battalion’ (skidlöparbattaljon) and a ranger school at the I19 regiment located in Övertorneå between 1910 and 1943. In 1945, this organization was transformed into the Army Ranger school (Arméns jägarskola) in Kiruna. Between 1975 and 2000, it was also a Lapland ranger regiment (I22) before the Government disbanded it in favour of only using K4 to educate and base Norrland Rangers (Wikipedia Citation2023b).

To further contextualize how Norrland Rangers nurture ideas about themselves and to develop methodological considerations, the following section presents the memoir material and the context of their publication.

Blå Dragonen, Lapplands Jägare and additional material

Rangers at the regiments, retired and newly examined rangers are the authors of Lapplands Jägare and Blå Dragonen. These annual journals are related to regiments (I22, Lapplands Jägare, and K4, Blå Dragonen). Both journals were originally part of the regiments, funded by the armed forces and distributed to everyone at the regiments. After the regiments were disbanded (I22 in 2000, K4 in 2005) – also after the re-establishment of K4 in 2020 – they have been produced and funded by rangers through their support associations, Kamratföreningen Lapplands Jägare (KLJ) and Kamratföreningen Blå Dragonen (KBD). Ranger conscripts, rangers and retired rangers are members of these associations, which today have around 600 members (Borgman Citation2023; Hald Citation2023; KLJ Citation2023b). Whereas Lapplands Jägare is today produced in 600 copies per year,Footnote3 by contrast, 2000 copies per year of Blå Dragonen are sent to members and distributed to conscripts at K4, and to various sections within the Armed Forces. Besides producing the journals, the associations also organize hikes and other activities (Borgman Citation2023; Hald Citation2023).

These journals aim to work as a forum for relevant information to the members, with, and, in the case of Blå Dragonen, a particular emphasis on what the ranger school (K4) has been doing the last year (Borgman Citation2023; Hald Citation2023). Details on irregular warfare, equipment they use, and operational aims are rare. This can be because of the classified nature of this information, and since everyone knows most of these aspects of training and prefers to share memories of good times. For intertextual comparisons, there are similar journals and support associations for other Swedish Armed Forces ranger regiments, for example, Kustjägaren (marine rangers) and Livhusaren (parachute rangers).

In preparing for the analysis, issues of Lapplands Jägare from KLJ (1968–1995), and Blå Dragonen from KBD 1970–2008, and 2020–2022 were read. Issues when there was no active formation of conscripts at the regiment, and thus no accounts of this process, have been left out from the analysis. The reading at once makes possible an overview of ranger training for a more extended period and comparisons over time. However, it also poses challenges since Sweden, culturally, politically and in terms of the broader security landscape, changed vastly during this period. Despite these changes, in reading the material, Norrland Ranger training appears surprisingly continuous. However, to avoid missing essential nuances from different periods and avoid generalizations, this challenge is brought up in the analysis and conclusions.

The analysis is based on accounts of what today is called the first ‘ranger exercise’ – the beret march combined with survival training, and on texts by newly formed rangers on their conscription year, but also on texts that detail the specific ranger ‘character’ and warrior ethos. This selection excludes detailed accounts of ranger exercises 2–4, which have a more military orientation of training warfare scenarios, with specific tasks of irregular warfare, which usually take place during winter. Experiences from these exercises are, however, sometimes brought up in texts on the conscription year. This selection makes the military content less present than would a reading of all the ranger exercises, and the outdoors experience of the initiating first ranger exercise more present. The analysis is based on texts on the first ranger exercise and the conscription year in KLJ Citation1968, Citation1970, Citation1983/84, Citation1991, Citation1993 and Citation1995 and in KBD from KBD Citation1970, Citation1993, Citation2020, Citation2021 and Citation2022.

In summary, the journals and the selection offer rich material to analyse how Norrland rangers make sense of how they are affected by, relate to and become through outdoor training. The journals also contain photos, which are analysed from the viewpoint of their content, the affects they transmit and their atmosphere. Apart from the journals, the analysis draws upon books written by Norrland rangers on their education and military force. The analysis is based on the author’s translations from Swedish into English. The author has also discussed interpretations with two former Norrland ranger colleagues to test them. Apart from these colleagues, the author has no relations with any rangers.Footnote4

Reading Norrland Rangers’ memoirs of outdoor training

Analysing how rangers write about their outdoor experiences to an assumed readership of other rangers implies engaging in memoir material. Military memoirs and self-representations offer rich material to study how war and military training touch people (Sylvester Citation2012). Such accounts of war and military training foreground bodily sensations (Hariri Citation2008, 7–8), making them suitable for examining affects and military identity constructions (Duncanson Citation2013; Woodward and Neil Citation2013, 152; Dyvik Citation2016a). Moreover, Yuval Hariri (Citation2008, 7–8) notes that military authors use embodied experiences to make ‘revelations’ about war, performing a ‘flesh-witnessing’ from the assumption that ‘only harsh bodily conditions produce authentic and reliable truth’ (10). Such accounts of war are often ‘informed by Romantic sensibilities about the experiential and the sublime’ (Woodward and Neil Citation2013, 153). Memoirs by rangers thus offer rich material to explore the wealth of experiences and becoming from outdoor training and the representations of the arctic environments in these accounts.

There are, however, limitations to using this memoir material. Among these is the fragility of human memory (Woodward and Neil Citation2013, 120), but also the fact that most of these accounts are written by newly examined rangers to a larger ranger community, becoming expressions of relief and pride as to have made it into that community, potentially excluding difficult experiences. Moreover, memoir material is considered identity-producing and meaning-constructing material rather than reflecting any ‘truth’ (Dyvik Citation2016b, 13).

Epistemologically, echoing McSorley’s (Citation2020) claim that ‘there is no such thing as raw sensation’ (156), the adopted constructivist approach to the material implies that accounts of sensations are viewed as always already cultural, gendered, and discursive. Such a reading requires a reflection on how to understand bodily sensations and affects in the analysis. Affects involve sensations, moods and ‘energies [that] transmit through bodily encounters’ (Åhäll Citation2018, 40), such as pleasure, thrill, disgust, anxiety, or joy. Affects are assumed to give value to what it implies to become a ranger, to move people and to create meaningful connections, for example, between outdoor life, masculinity, and military training. While it is assumed that the authors frame these texts discursively, it is thus also assumed that they reflect affective, material, embodied experiences, which, with McNeill (Citation1995), cannot be fully contained by words (see also Bennett Citation2001, Citation2010). Therefore, the reading will both attend to how these texts and images seek to express something about and through the body as ‘flesh’ and, at the same time, how they are ways of framing such experiences.

In the analysis, I understand the relation between how they describe bodily sensations of outdoor training and frame these experiences as accounts of becoming. Foregrounding becoming implies reading their accounts of outdoor training as testimonies of how their bodies and subjectivities are ongoingly shaped from being entangled with multiple elements and relations in assemblages, entanglements that put them on different trajectories or lines of becoming (Biehl and Locke Citation2017). By focusing on becoming, the analysis reveals how the texts describe becoming ranger as experiences of how the multiplicity of the outside folds into them and, at the same time, how they bend or affect outside forces in various ways that shape micro-becomings (Biehl and Locke, 42). This reading emphasizes the entanglements that constitute their becoming, as they are exposed to and have cartographic embodied experiences of the arctic geographies while being shaped by the power relations of the ranger formation, at the same time as different desires animate them. With Biehl and Locke, quoting Deleuze:

becomings ‘belong to geography, they are orientations, directions, entries and exits’. The very materialities of space affect and impinge on the subject, encouraging or constraining possibilities for movement and adding further texture to lived experiences.

With this approach, the framings of embodied experiences are therefore read as both accounts of being entangled with these geographies and ways of ‘reterritorializing’ (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1986, 86) these embodied experiences, fixing them ‘in place’ through various understandings of the meaning of these experiences: as experiences of being a ‘real man’, as a question of the true ranger character, as adventure or to be Swedish. At the same time, the framings induce a desire to affirm entanglements with the geographies and bodily experiences in ways that overflow any framing of a given framework or ‘place’ for understanding their becoming through outdoor training.

In foregrounding becoming, I pay particular attention to the role of affirmation in the representations of outdoor training. For Gilles Deleuze, affirmation entails a ‘belief in the world, as it is’ (Deleuze, Tomlinson, and Galeta Citation2000, 172); a belief, with Kathrin Thiele (Citation2017, 26), in the ‘here and now … radically immanent, terran, and earthly’. Drawing upon Friedrich Nietzsche’s notion of affirmation as to will ‘life as you now live it and have lived it … to live once again and innumerable times again’, for Thiele, affirmation entails a concern for and a relationality with the situation we are always already participating in and entangled with (Nietzsche as quoted by Thiele Citation2017, 27). In Deleuze’s reading of Nietzsche, affirmation is thereby engaged in the ‘transmutation of pain into joy’ (Deleuze Citation2006, 173). The conversion of ‘pain into joy’ also involves learning (Chiddo Citation2022) insofar as affirmation is cultivated attention. In the material, I interpret this learning as cultivating attention to ways one can be affected by the here and now and the specific surroundings during outdoor training or by values such as community or cooperation. In the analysis, I, therefore, understand affirmation as practices described in the texts or in the writing of ‘saying yes’ (Nietzsche) to, or embracing, oneself, one’s activity or commitment and the world. These practices are expressed as, or through, cultivation of attention to wondrous and enchanting aspects in the surroundings or in the present, or values that animate the writers’ self and their task, often when describing difficult situations.

The passing on of a culture of affirmation in relation to the challenging experiences of outdoor training is also understood through psychological theories on ‘self-affirmation’ (Sherman and Cohen Citation2006). In psychology, self-affirmation refers to the more immediate adaptation that individuals are capable of when facing threatening information, events or stress. In the context of Norrland Rangers’ representations of confronting and overcoming challenges of outdoor training, one can trace individual and collective practices of self-affirmation that enable them to overcome exhaustion and being deprived of food or sleep more effectively. From this perspective, I trace how they, by embracing beauty and wonder or cooperation, promote ‘values, beliefs and roles’ to reduce the threats of this challenging, unknown and unpredictable training.

Furthermore, in this perspective, the acts of writing down what one values and cherishes and sharing these thoughts or observations in the ranger community through texts and images are viewed as instances of individual and collective self-affirmation (McQueen and Klein Citation2006; Sherman and Cohen Citation2006) that socialize rangers to affirm the outdoors and their own community. In this view, the rangers’ written testimonies are at once read as descriptions of affirmation during training and acts of directing attention through writing and reading to experiences, values and ways of relating to challenges – often through humour and descriptions of wondrous sensations – that make one more flexible with regards to challenging aspects of outdoor training.

Methodologically, in analysing how affirmation is cultivated, drawn upon, and articulated through writing, I pay particular attention to what Dyvik (Citation2016a) calls ‘assemblages of pleasure and pain’. Dyvik develops this concept to point to how ‘war’s complex embodied assemblages’ are experienced through the body, highlighting the complexity of war and embodied experiences as accounted for in military memoirs (Dyvik Citation2016b). For Dyvik, ‘memoirs show how war is experienced as an assemblage of pleasure and pain’ to point to how ‘this is caught up in complex blurrings of individual and collective militarized bodies’ (abstract, 133). Furthermore, these assemblages, which she also describes as of ‘enjoyment and suffering’, are gendered. I use the notion to pinpoint how Norrland Rangers often express surprise at having experienced entanglements of pleasurable and challenging outdoor training experiences. These descriptions usually turn around attempting to transform the difficult experiences, for example, exhaustion, pain from uncomfortable shoes, extensive marching or a heavy backpack, into the pleasures of achievement, of enjoying the scenery or of collaboration.

Finally, drawing on Robben’s (Citation1996) notion of ‘ethnographic seduction’, I have also tried to ask myself how the authors attempt to influence the impression people should have about them and how I relate to the risk that I, in my interpretations, feel as if I understand their discourse from within at the price of having ‘introjected the informant’s created projection’. To attend to emotional ways of framing experiences through vernacular or lyrical writing, however, also necessitates the employment of an aesthetic sensibility (Åhäll Citation2018; Ahall and Gregory Citation2015), including paying attention to how embodiment and affects also work through me as a scholar (Dyvik Citation2016a).

Physical and emotional experiences of Norrland Ranger training

In the following, by reading accounts of physical interactions between bodies and environments during outdoor training, six recurrent themes of embodied experiences and becoming through outdoor training are traced in the material: the overall transformation from outdoor training during the conscription year, wading, exhaustion, survival training, hygiene, and aesthetic experiences of the outdoors.

In 2021 Oskar Hildman from the 22nd platoon details the overall transformation from outdoor training during conscription (2020–2021). He describes how the forests in which they spent much time were initially for some ‘something strange, barren, and superstitious’, but after the conscription year, they were a ‘terrain that is a part of us all, something that unites us who wear the green beret’. Moreover, he foregrounds how they, during the year, were ‘educated, instructed, told and referred’ by humans, but that they were only ‘fostered’ by the ‘mission’ and the ‘forests’ (KBD Citation2021, 14). Generally, this account resonates with the view that the military subjects conscripts to the demands of natural environments in a rite of passage, where natural environments are used to separate, test and incorporate them into a soldier community (Danielsen Citation2018; van Gennep Citation1960; McSorley Citation2016; Woodward Citation1998). However, nature does here not appear as something to transcend, but rather as something that they become entangled with in the making of a ranger ‘form of sensation’ (McSorley Citation2020). The forests are increasingly less ‘strange’ and comparable to ‘the mission’, they ‘foster’ the conscripts, implying that there is a relation of trust and an attunement as the forests become folded in and ‘part of us all’. Later, Hildman summarizes the rewards of overcoming the extreme challenges of becoming a ranger:

We have an enormous luggage of experiences, comrades and insights that fare well for all sorts of possibilities. No matter where we are, the memories return to us. The darkness, the cold and the northern forests are now a part of us, and they point to the future. The forests may be dark, but the future is bright: because we have learnt to work, we have learnt to cooperate, but above all, we have learnt to enjoy.

The quote reflects an entanglement of heterogeneous elements where the bright future is a result of having learned to enjoy and cooperate. The process of having folded in ‘the darkness, the cold and the northern forests’, seem to have made them stronger and more confident. While the quote could be read as ‘neoliberal desires for transformation, self-actualisation, challenge and thrill’ (McSorley Citation2016, 113), it could also be read as a sensibility dating from the Romantic period (Hariri Citation2008; Randrup Pedersen Citation2017). The image is, however, not that of a ‘victory’ (Woodward Citation1998) over nature’s demands but that of acquiring a different way of relating to these demands, to oneself and the group through the ranger training. The somewhat lyrical writing both points to an attempt to account for and share the somatic experience of this becoming and to the fact that Hildman writes to other rangers, reinforcing the attractiveness of the group and justifying the efforts to make it into it. This possibly reflects an attempt to reduce the dissonance from the unpleasant experiences of those efforts, making entering the group more attractive (see Aronson and Judson Citation1959).

Becoming Norrland ranger here shines forth as an assemblage of somatic experiences, elements, and affiliations that are affirmed in their reinforcing coexistence, as elements that add to the empowerment and sweetness of having become a ranger. As much as it points to the fact that these environments and learning to enjoy together despite hardships are part of an instrumental transmission to make soldiers who can survive behind enemy lines, the linear notion of transmission of values and skills does not entirely capture how the assemblage of multiple elements in the quote shape their described becoming. Its lyricality indicates that becoming a ranger also comprises micro-becomings from cultivating ways to affirm darkness, cold and dark forests, and possibly also a culture for which this is valuable. The quote – and indeed becoming a ranger – could, therefore, also be read as a tribute to acquiring the flexibility, through these affirmations, to attend to multiple inspirations and feelings of empowerment related to becoming a Norrland ranger.

Wading is also a recurrent theme of embodied experiences of arctic outdoor training in the journals (KLJ Citation1968; KLJ Citation1991; KBD Citation2021). The instrumental aims of wading are to cross waters and to keep the clothes and equipment dry. However, wading also appears in the material as a way to incite emotions and bring the conscripts out of their comfort zones. In a text from 1968, an unknown author summarizes the thrill of wading on slippery stones: ‘for each step one takes, one thinks it is the last one on this earth’ (KLJ Citation1968, 15). Moreover, the entanglement of excitement, cold water, slippery stones, and crossing rivers with dry clothes is framed as an affirmation of life: ‘After no end of bother one ends up on the other side with the heart in one’s mouth and wet underwear. The essential is that one made it over. The wading is over for this time, luckily. Life is nevertheless good’ (KLJ 1968, 15). Becoming through wading here shines forth as learning to embrace these tests by focusing on their thrills and on the rewards of overcoming them. Wading here appears as a liminal passage and micro-becoming in which one ‘almost dies’ to make it over on the other side with an enhanced feeling of aliveness.

Another returning theme to describe embodied experiences of outdoor training is exhaustion. In one account from 1991, Staffan Hämäläinen, before the march a command trainee, describes how they expected the march to be about ‘coma and forehead, which turned out to be correct this time as well’ (KLJ Citation1991, 18). Hämäläinen uses the vernacular ‘coma’, meaning exhaustion, and ‘forehead’, the stamina or capacity to keep going despite ‘coma’, to narrate the march as a trail of exhaustions divided over eight days, consisting of long marches, heavy backpacks, wading, lousy sleep, bad weather, etcetera. On the sixth day, they endured:

… one of the most tiring days in our lives … After more than 30 kilometres, the so-called ‘super coma’ started to kick in. Once it has started, one only works on forehead … How far we went? Well, those who took the shortest path went around 50 kilometres.

However, despite being even more tired on the seventh day, the author still describes the beret ceremony that ended the march on the eighth day as ‘worth all the sweat and effort’, adding in a cocky way that when they eventually got their new berets, they had to get bigger ones ‘because our foreheads had grown too thick for the old ones’ (19). We here see how Hämäläinen uses vernacular to both describe exhaustion and to communicate the attractiveness of becoming through it. The cocky comment on ‘thick foreheads’ reflects how the attractiveness of overcoming exhaustion is articulated through assumptions about masculinity as being tough and enduring (Hearn and David Citation1994, Connell Citation2005). At the same time, the sense of humour shines forth as at once a way of celebrating the achievements within this masculinity – for which this humour is itself a form of enjoyment – and, through this enjoyment, as a way to reduce the dissonance from exhaustion. The sense of humour thereby participates in making it more clearly ‘worth all the sweat and effort’ within the group (see Aronson and Judson Citation1959). Becoming promoted as a ranger here shines forth as an assemblage of pleasure, exhaustion, and sore bodies framed through this humour. However, the passage also transpires with wonder from exhaustion itself and vulnerability, possibly indicating how collective self-affirmation to become flexible enough to endure exhaustion is entangled with this masculinity (McQueen and Klein Citation2006).

During the beret march, the ranger conscript’s body is tested and formed through survival training, accounts which return in the material. As of 2022, the first ‘ranger exercise’ comprises six days of trekking and four days of survival training (KBD Citation2022). As a form of discipline, the liminality phase of survival exercises shines forth as bringing the conscripts out of their comfort zones, breaking them down to reconstruct them around new ways of reading and relating to the surroundings, to their own body and the group. In 2020, Axel Mäntysalo describes how the conscripts were deprived of sleep and food and needed to perform survival tasks, such as collecting herbs and making tea, but also collaborate. At a certain point, they were isolated and had to err alone in the forest for 24 hours without the right to speak to anyone. He concludes: ‘despite a misery-filled existence [it made] one thing stronger than ever – the comradeship between us’. It was, in summary, ‘something to be proud of’ (KBD Citation2020, 5). Reflecting research on initiation (Aronson and Judson Citation1959), the misery – and its thrills – here appear as reinforcing the emotional rewards and the meaning of making it into the group, with the pleasure of overcoming survival training becoming a common affective bond that forges the group.

Echoing how the rangers actively justify and add to the attractiveness of making it through survival training, two years later, Tim Hedqvist Ödling and Hampus Skärhult (20. Jplut) frame the same ‘misery’ and the achievement of making it through it as ‘having deserved one’s place among a unique elite’ (KBD Citation2022, 9). Apart from increasing affiliation, these passages could also be interpreted as recurrent practices of collective self-affirmation, of embracing the values of comradeship and possibly an appreciation, enhanced through these tests. Adapting to and folding these challenges into their self-conception make them able to interpret the ‘misery’ less defensively (Sherman and Cohen Citation2006).

Another recurrent embodied experience in these texts is hygiene routines. Several authors write on cold mountain baths and ‘field saunas’ during the marches (KLJ Citation1983/84; KLJ Citation1991; KLJ Citation1993; KLJ Citation1995). In a text from 1991, corporals Erik Åredal and Svante Skeppström describe the experience of field sauna, made from rocks and a tent, which took place after six days of marching, as ‘probably [the] most appreciated element’ of the march, adding: ‘After having bathed in the zero-degree water and having sit in the sauna, most of us felt like new humans’ (KLJ Citation1991, 22). Field saunas illustrate how the transmission of the instrumental aim of hygiene is entangled with recreation, recovery, pleasure, and cultural ways of transforming the environment. Again, feeling like ‘new humans’ reflects how life returns to the exhausted body, now entangled not only with the surroundings through exhaustion but also through enjoyment and care. The representations of field saunas and cold baths thus illustrate the Norrland Ranger hygiene as a pleasurable element in an assemblage of sore bodies, cold lakes, hot stones, steam and exhaustion. It also shows how command, by ordering these breaks, incites pleasurable sensations and emotions, tuning the rangers to attend to and embrace the becoming of feeling like a ‘new human’ from transforming and using these environments.

Finally, the journals contain ample and often detailed texts on the wondrous surprises of aesthetic experiences of moving and dwelling in these landscapes. In the words of Mäntysalo in 2020: ‘Beforehand, we thought that it [ranger exercise one] would be tough and rough. In fact, it was a fantastic tour on the mountain’ (KBD Citation2020, 5). Others convey a sense of wonder and thrill of these experiences to their readers: the wondrous landscape shift after a sudden snowfall overnight (KLJ Citation1991), the thrill of cancelling a climb due to heavy fog (KLJ Citation1970, 25), how the intense beauty of the day’s march or the seasons relieved the conscripts from being tired or grumpy despite the heavy backpack and sore bodies (KLJ Citation1968; KLJ Citation1970, 28; KLJ Citation1982/83, 33), or how the scenic mountains and the nature made them realize ‘how small the human really is’ (KLJ Citation1982/83, 49). These recurrent features reflect moments of enchantment, ‘A state of wonder…the temporary suspension of chronological time and bodily movement’ (Bennett Citation2001, 5), which appear in the material as coexisting with other ways of attuning them to the environment. Hildman’s description of a ski march in the dark in his recollection of his conscription year in 2021 foregrounds the environment’s affordances in inducing these moments. Hildman retells how the conscripts, suddenly, during a ski march, experienced a colourful spectacle of northern lights:

As if everyone was possessed, one after one, we looked up. The sky was entirely green. Never has the endlessness of the universe revealed itself to us like this; the stars were everywhere. The melancholic moon seemed to watch us. The whole swamp shone like thousands of crystals in the cold. And we continued skiing, but this time, the breaths, the cold air from the sky, felt like the sweetest gift we ever had gotten. Right then, we felt at home because we realised the absurd: we realised that we were living.

This lyrical account of how the ‘test’ of becoming a ranger also consists of this enchanting experience – that probably most rangers have experienced – points to the affordances of the environment in inducing specific affects and states in the conscripts. Moreover, it also indicates a micro-becoming from cultivating attention to and enjoyment from these moments, enhanced and shared through writing and reading about them. In the quote, the ‘forehead’ mode of skiing in the cold that prevailed is replaced by a sensation of the breaths, which used to be tiresome, as the ‘sweetest gift’ in an embrace of the moment and the sensations, making the conscripts feel ‘at home’ and ‘living’. Like how Hildman detailed a ‘bright future’ from having learnt to enjoy during his conscription year, the entanglement of the micro-becoming of enchantments and the achievement of becoming Norrland ranger is here described lyrically. Thus, becoming a ranger also contains the micro-becomings from being entangled with these moments, with the environments inducing them and with the emotions that, by embracing these moments, gradually become associated with them.

The sensations from becoming entangled with these environments are also expressed by the rangers in more specific accounts of places with affordances to affect those dwelling in them. In 1983, Kangas (3. Jplut) details his experience of a particular place west of Kiruna:

Around lunchtime the second day, we arrived at an astonishing place, which, in my view, reminded a lot of the place where King Kong bathed the chick, some kind of small waterfall with a small pond or such. The place we were at was behind Lapporten [a famous mountain gate]. It was a pretty broad jokk [small river in Sámi] that meandered to suddenly interrupt itself in a small waterfall of 3–4 meters. Right below the waterfall, there was a small casserole formation. It was perfect for bathing there. The water was indeed freezing cold, but it was nevertheless good … newly washed and relatively crisp, I took a nap until the march-ready group arrived.

The quote reflects the multiple participations of the author’s body in this place with its specific affordances. Enjoying the beauty and the cold bath, and napping, here constitute a break in an otherwise challenging march. The banal reference to King Kong and the ‘chick’ testifies at once to the mirth the author experiences in describing this place and from doing so to an assumed readership of peer male rangers who are assumed to share a similar masculinity. Again, the sharing of this experience in this way, to this assumed collective, appears as itself an enjoyment. Retelling the experience, however, also conveys a particular atmosphere of surprise from the bodily enjoyment of this place during a gap in the otherwise exhausting and instrumental exercise. In particular, the multiple sensations and shifting states of the body – enchanted, cold-bathing and napping – that the place and his embracing it afforded his body stand out. In addition, the geographic indication and the details reflect an embodied cartographic fascination with experiencing these geographies that the author assumes the readers share with him.

All in all, the physical interactions between the bodies and the environments traced in this section reveal that rangers describe how their bodies become entangled in assemblages of heterogeneous elements, attuning and affecting them in multiple ways that shape both micro-becomings and their becoming ranger. In these representations, learning to embrace micro-becomings and diverse sensations, and to attend to enjoyment and pleasure of the moments and the environments, as ways to become flexible, adapt oneself and overcome challenges from ranger training, stand out. Also, the texts reveal how the rangers actively enhance the attractiveness and meaningfulness of making it and becoming through these tests, possibly to decrease their dissonance or challenge and increase the status of making it through them.

The following section details how these texts, through discursive frameworks, also to some degree reterritorialize their bodily experiences to specific notions of these experiences. The texts however also reflect that writing about these experiences is part of a culture and socialization in which learning to affirm the outdoors is central in emotional and desire-filled ways that exceed these reterritorializations.

Framing ranger training and the Arctic north

In the journals, there are no non-normative or non-affective ways to describe the outdoor training experiences. Already information material on K4 nurtures of an affirmative orientation to the outdoors by framing the mountain marches as ‘usually conceived as the peak of the education by both command and conscripts’ (SAF Citation1974, no pagination). In the following, I trace six ways through which the rangers frame outdoor training and the northern geographies in the material: through constructions of the north, through national identity, constructions of masculinity, as a real achievement to be proud of, as a collective adventure and as something to master that is inherent to the ranger character and warrior ethos.

Reflecting research on the constructions of military geographies as sites for adventurous becomings (Woodward Citation1998, Woodward Citation2000), a recurrent framing of embodied experiences of ranger training in the material is through specific constructions of the arctic north as a place of pristine nature (and not humans) in contrast to southern Sweden (KLJ Citation1968; KLJ Citation1995; KBD Citation2021). These constructions appear as directed to readers from southern Sweden or south of the north. In 2021, Hildman describes the area close to Arvidsjaur as making comrades, whether from ‘Linköping, Mälardalen, Dalarna, Skåne or Umeå … all equal before the deep forests whose waving green sheet covers the Norrland inland’ (KBD Citation2021, 14). The framing is peculiar insofar as what is usually the ‘equality’ of being a conscript, through the military uniform and subjection, here becomes re-framed as a somatic equality of being equal through the subjection to the ‘deep forests’.

The material also reveals how the framing of these geographies took place during the marches, with command, in 1968, 1970 and 1991, holding small lectures on the Sámi’s environmental knowledge and geographies before bedtime (KLJ, Citation1968, KLJ Citation1970; KLJ Citation1991). It also takes place through small comments, such as when leadership contend that a bit of snow overnight is ‘no real cold’, urging the conscripts not to dress too warm when marching (KLJ Citation1991). Reflecting instances of self-affirmation, humour and retelling misadventures are also recurrently used to turn challenges associated with these environments, such as marching through a swamp, into something one overcomes through a cheerful, and thus flexible, mindset (KLJ Citation1968; KLJ Citation1991). Overall, these framings construct training in these geographies as adventurous, orienting the rangers to this specific meaning and to enjoying training in them.

Constructing the periphery as a wild ‘wasteland’ also appears as related to constructions of national identity in the material. Apart from the adventure of climbing Sweden’s highest mountain Kebnekaise, which the rangers describe recurrently in the material, this is always already a symbolic act. Representing oneself through climbing Kebnekaise (KLJ Citation1995; SAF Citation2023b) or having moose (K4) and wolf (I22) as regiment symbols, draw upon and reinforce assumptions about being Swedish, which has been actively constructed through references to nature since the 19th century (Thurfjell Citation2020). Comparable to how British soldiers train in peripheral rural areas (Woodward Citation1998, Woodward Citation2000) and to the importance for military power in claiming the right to use land (Woodward Citation2004), training in the north here appears as at once an adventurous journey to the heart of the nation and a militarization of areas that historically were home to the Sámi before the Swedish state colonized them.

As already shown, experiences of outdoor training are recurrently framed through specific constructions of masculinity, making becoming a ranger into a particular ‘manly’ achievement shared between ‘men’. Internationally, rangers represent one of the least gender-mixed military units, with historical resistance to accepting women into their ranks (ABC News Citation2015; Vent Citation2022). Since the 2000s, there have been female Norrland rangers, and the number of female rangers and employees at K4 is increasing (Vent Citation2022). However, in the material, women are only mentioned and visible in the 2020s. Accounts of cold baths or the ordering of a shave in a stream before the beret ceremony, with the conscripts kneeling in one decimetre of snow (KLJ Citation1991), appear as the retelling of acts of care and incorporation within a community of men constructed through certain notions of masculinity (Connell Citation2005). This is illustrated in by uses of excrement humour (KBD Citation2021), vernacular turning around being tough and enduring, and sometimes sexist narratives, as when climbing a mountain is compared to the efforts and difficulties of seducing and sleeping with a woman (KLJ 84/85, 58–61). Comparable to previous findings on army rangers (Caraccilo Citation2015; Alvinius, Larsson, and Larsson Citation2016) and infantry in Britain (Woodward Citation1998, Citation2000), embodied experiences from this training are thus often framed as the matter of becoming a ‘man’, a patient, resilient and cooperative man, ready to support his ‘brothers’.

Another recurrent framing of the meaning of going through this training turns around the tradition, pride and ‘responsibility’ of being part of the unique ranger community (Mäntysalo in KBD Citation2020; Hedqvist Ödling and Skärhult (20. Jplut) in KBD Citation2022). Echoing Thomas Randrup Pedersen’s account (Citation2017) of how war and becoming a warrior are nurtured by an ‘existential desire for the real’, becoming a ranger through outdoor training is here represented as offering something ‘real’: a real connection to a commitment and an intelligence or sensitivity related to what it means to survive and endure in these environments, framings that all give meaning to becoming a ranger.

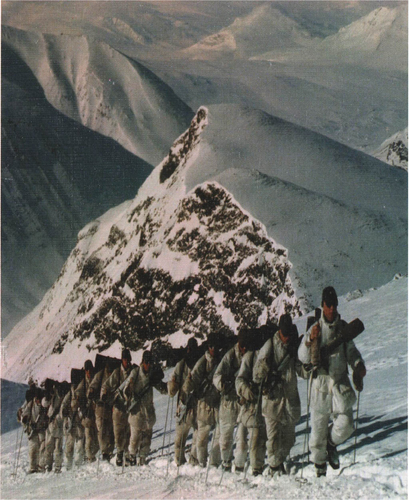

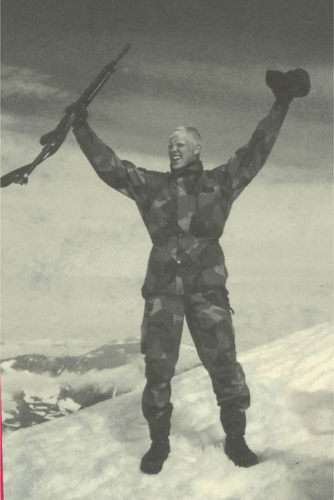

Moreover, the images () in the journals convey an overall image of Norrland Ranger life and education as a collective, manly, cheerful adventure and community framed through scenic nature:

Figure 1. Wading exercise, unknown creator, Lapplands Jägare (Kiruna: Malmfältens Grafiska AB, Citation1968), 14.

Figure 2. Cold bath, unknown creator, Lapplands Jägare (Kiruna: Malmfältens Grafiska AB, Citation1991), 19.

Figure 3. Climbing Kebnekaise, Lundquist, Björn, Lapplands Jägare (Kiruna: Malmfältens Grafiska AB Citation1995), cover page.

Figure 4. On the top of the mountain, unknown creator, Lapplands Jägare (Kiruna: Malmfältens Grafiska AB Citation1995), no pagination.

Figure 5. Group photo posing as warriors framed by an Arctic valley. In this photo, two women, centre and low right, are visible for the first and only time in the material, unknown creator, Blå Dragonen (Arvidsjaur: Kamratföreningen Blå Dragoner Citation2020), 5.

Figure 6. ‘Far behind the enemy lines, without contact with his own [troops], the army ranger must fight his tough fight alone. Despite this, there is no place for desperados in his rank. The ranger units are the corps of the strong characters’ (quote from Vår Armé (1959), unknown creator, Lapplands Jägare (Kiruna: Malmfältens Grafiska AB, Citation1993), 66.

![Figure 6. ‘Far behind the enemy lines, without contact with his own [troops], the army ranger must fight his tough fight alone. Despite this, there is no place for desperados in his rank. The ranger units are the corps of the strong characters’ (quote from Vår Armé (1959), unknown creator, Lapplands Jägare (Kiruna: Malmfältens Grafiska AB, Citation1993), 66.](/cms/asset/886b3126-454e-4c2d-8c7e-eb225450bd1b/rcms_a_2368358_f0006_oc.jpg)

Lastly, a central way through which the rangers frame embodied experiences in the material is recurrent accounts of the ranger, and acquired outdoor skills, as ‘the best soldier’ or the ‘strong character’, which serve to promote the ranger in relation to other types of soldiers. In ‘To you, Future Ranger’ (KLJ Citation1993), corporal Sjöberg (2nd platoon, 2nd company) frames the experience of becoming a ranger as one of experiencing ‘mountains, bogs, and stones’ in ‘God’s wonderful nature’:

Forget about Rambo; forget everything you have fantasised about; the reality is different. Up here in Kiruna … the elite of the ranger fight is trained, the silent but oh-so-effective combat. The best soldier is not always the one with the most muscles and most knowledge of the enemy’s vehicles or weapons. The best of us are those who can make it alone in the forest, who do not get field-coma after two hours, who can light a fire after three days of intense rains, who can cook at minus thirty degrees Celsius, and above all, who after seven-eight days in field can still solve their task and help their comrade who right then is unable to carry his/her backpack.

The quote reveals how the author, through this narrative on Norrland Rangers, seeks to displace the ‘reality’ and military notions about the necessary embodied skills and attributes of the ‘best soldier’, carving out a character who is resilient, patient, and enduring, trained – and socialized – to ‘not get field coma after two hours’.Footnote5 Next to this letter, ending the journal, this photo () covers the page:

Again, these framings construct the ranger’s character as strong but, like the Rambo reference, not a ‘desperado’. The photo of a ranger in midnight sunlight and the reference to ‘desperado’ paraphrases a Western image of a lonesome cowboy riding towards the sunset and reminds of the famous romantic painting by Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. Echoing Hariri (Citation2008) and Woodward and Neil Jenkins’ claim (Citation2013, 153) that military war recollections are ‘informed by Romantic sensibilities about the experiential and the sublime’, the letter above and the photo’s text (from Vår Armé), as well as its motif, construct at once an argument on the military importance of the Norrland Ranger compared to other soldiers and a sentimental image of the Norrland Ranger. The ranger emerges as at once inseparable from the constructed ranger warrior ethos and the arctic geographies that ‘foster’ him. Echoing existing ranger research (Ruffa Citation2015) and initiation literature (Aronson and Judson Citation1959), these passages reflect how the rangers take effort to (re)produce this image to increase group attractiveness internally and to defend the particularity and military importance of Norrland Rangers against other sections of the armed forces.

Conclusions

This article started from the observation that despite being a common feature of military training and in representations of how the military shapes soldiers, particularly for rangers, how soldiers are entangled with outdoor training environments and their becoming from such training has been little researched. In response to this query, this article explored memoirs by Norrland Rangers and their images of outdoor training experiences in northern Sweden. The article traced how Norrland Rangers make sense of and frame their embodied experiences of outdoor training and the northern geographies.

The findings suggest that these rangers represent becoming through outdoor training as a process of multiple coexisting experiences, in which micro-becomings of surviving, dwelling in, and enjoying being with, the arctic environments were entangled with acquiring skills of irregular warfare. However, they also indicate that the micro-becomings from sensing intensities, surprises, enchanting experiences, singularities, and other sensuous experiences from training in these geographies were articulated in ways that nurtured an affirmative orientation to the outdoors. This orientation and the desires infusing it appeared as important to becoming a ranger and yet as existing under the threshold of more formal representations of ranger formation. Passages describing these micro-becomings constituted performative acts of giving meaning and value to these experiences and articulating their transformative potential by sharing them through texts and images. At the same time, the findings also indicate that efforts to frame the meaning and value of becoming a ranger and being entangled with the northern geographies to some extent reterritorialized those heterogeneous micro-becomings. This was reflected in framings of these experiences through constructions of being Swedish, through the uniqueness and status of the ranger community, by underscoring the ranger character and ethos, through photos of a shared collective adventure and by framing becoming a ranger as becoming and being a ‘man’.

How should we consider the active nurturing of an affirmative orientation to the wealth of outdoor training experiences in the context of research on embodied experiences of military training and literature on how environments are used and constructed to form soldiers? While previous research has shown that the military uses outdoor training to make soldiers fit, tough and ‘men’ and to make them able to read the environments through a rational, militarized gaze (Woodward Citation1998, Citation2000, McSorley Citation2016), the exploration showed that the Norrland Rangers’ describe and value learning to acquire an affirmative disposition with regards to outdoor training as central for their becoming. Rather than being secondary to or accidental elements in their training, echoing McNeill’s (Citation1995) observation on the intriguing pleasures of drill, being attuned to affirm challenging and yet enjoyable experiences from the outdoors appeared in these representations as central to socializing the conscripts. It appeared to shape how they related, with their bodies, to the overall experiences and challenges of the outdoors and how they represented these experiences. This socialization is also possibly fundamental to their specific warrior skills, even if that cannot be assessed based on this study.

Contributing to scholarship that foregrounds the coexistence of embodied experiences of pleasure and pain at war and in military training (Dyvik Citation2016b; Welland Citation2018), the exploration, therefore, provides new insights into how micro-becomings from outdoor training are drawn upon in the making of these rangers. While the findings are in line with existing research on how the military uses and constructs geographies to attune bodies affectively and to constitute specific knowledge of the terrain (Hockey Citation2009; Gregory Citation2016; McSorley Citation2016), to encourage recruitment, and to foster teamwork and military identities (Woodward Citation1998, Citation2000), they also showed that these rangers relate to the affordances of the arctic geographies to move them in various ways that exceed the focus of this research. The findings indicate that experiences and emotions from being entangled with these geographies, but also from how they were framed, appeared as central, affectively, for becoming rangers, to attribute value to becoming one and for their understanding of the northern geographies. Apart from being in line with observations that rangers defend the cultivation of embodied knowledge of the environment as an essential military objective (Ruffa Citation2015), adding to ranger research on how ranger education recruits people interested in the outdoors (Danielsen Citation2018) the findings provide new insights into how rangers actively nurture such an interest through representations of training and their self-understanding. Finally, the results thus also have a potential impact on the Norrland rangers themselves insofar as they point to how these rangers transmit a pleasure-oriented outdoor culture in their community and during training and to the role of performative acts of representations and narratives about rangers for this transmission and their ranger identities.

The findings, however, need to be viewed considering some limitations of this exploration. Being an analysis of memoir material, as much as the results indicate potential connections between affirming the outdoors and becoming skilled at irregular warfare, this cannot be assessed based on this study. The analysis, however, has merits in showing how the wealth of experiences and emotions that this training gives rise to and how the arctic geographies are emotionally loaded in these representations are central to how these rangers construct what it implies to be a Norrland Ranger. Also, as much as selecting material that stretches over several decades and from two different regiments makes it possible to analyse a larger selection over time, nuances regarding these different regiments and the specific periods may have been lost. Despite many continuities in this training and how they write on them over time and between the regiments, some elements of fostering an affirmative orientation to the outdoors in one period, place or regiment, such as lectures on Sámi people’s understandings of artic geographies or using all-male field saunas, should thus not be assumed to be continuous as other values and more women enter the organizations.

Further research is needed to assess the relationship between how rangers nurture an affirmative orientation to the outdoors and the making of their warfare capacities. Future research on ranger training could focus specifically on possible connections between attending to the pleasurable elements of the outdoors and enjoying irregular warfare, such as ambushing adversaries, dissimulation, and other ways of using the environment to fight an enemy. Lastly, research should examine blurred affective and cultural borders and shared knowledges between local outdoor cultures and ranger training and how they historically have infused one another. This would further our understanding of the emotions, embodied skills and tacit knowledges that are inherent to the socialization of rangers in local contexts and of the rewards of local ways of relating to the outdoors that sustain these emotions, skills and knowledges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The term Norrland Ranger is a generic term for an arctic ranger that was both named Norrlandsjägare and Lapplandsjägare depending on their regiment. In this text I use this generic term to denote this type of ranger irrespective of their regiment (see Wikipedia Citation2023c).

2. To apply to become a ranger, one needs a high school degree and pass a general test of conscription. In addition, one needs to pass a demanding physical test, consisting among other things of 75 one legged repetitions on a 40-centimetre-high step board with a 20 kilograms backpack, and be able to run 3 kilometres under 14 minutes (SAF Citation2023a).

3. Lapplands Jägare is still produced by former rangers even though the regiment has not existed since 2000. This indicates that the community is strong and that they make efforts to sustain it (KLJ Citation2023).

4. However, the author’s grandfather served in the ‘ski troopers battalion’ at I19 (later transformed into I22) during World War II.

5. This is also reflected in letters to ranger conscripts by the retired rangers Curt Oswald (KLJ 1995, 33) and ‘Stenen’ (the Stone) (Rekyl Citation2022).

References

- ABC News. 2015. “First Women Set to Graduate from Army’s Grueling Ranger Training School.” ABC News. August 18, Accessed April 28, 2024. https://abcnews.go.com/US/women-set-graduate-armys-grueling-ranger-training-school/story?id=33144614.

- Åhäll, L. 2018. “Affect As Methodology: Feminism and the Politics of Emotion.” International Political Sociology 12 (1): 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/ips/olx024.

- Ahall, L., and T. Gregory. 2015. Emotions, Politics and War. New York: Routledge.

- Alvinius, A. B. S., G. Larsson, and G. Larsson. 2016. “Becoming a Swedish Military Ranger: A Grounded Theory Study.” Norma: International Journal for Masculinity Studies 11 (1): 34–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2016.1143291.

- Aronson, E., and M. Judson. 1959. “The Effect of Severity of Initiation on Liking for a Group.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 59 (2): 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047195.

- Bahmanyar, M. 2005. Shadow Warriors: A History of the US Army Rangers. Oxford: Osprey.

- Basham, V. M. 2013. War, Identity and the Liberal State: Everyday Experiences of the Geopolitical in the Armed Forces. New York: Routledge.

- Basham, V. M. 2015. “Waiting for War: Soldiering, Temporality and the Gendered Politics of Boredom and Joy in Military Spaces.” In Emotions, Politics and War, edited by L. Ahall and T. Gregory, 150–162. New York: Routledge.

- Bennett, J. 2001. The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings and Ethics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Biehl, J., and P. Locke, eds. 2017. Unfinished: The Anthropology of Becoming. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Borgman, Christer. 2023. E-Mail Correspondence. September 26, 2023.

- Caraccilo, D. 2015. Forging a Special Operations Force: The US Army Rangers. Havertown: Helion and Company, Limited.

- Chiddo, M. 2022. “Unwritten Futures: Deleuze, Affirmation, and Creative Becoming.” The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 36 (1): 87–104. https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.36.1.0087.

- Connell, R. W. 2005. Masculinities. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Danielsen, T. 2018. Making Warriors in a Global Era: An Ethnographic Study of the Norwegian Naval Special Operations Commando. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- De Lauri, A. 2021. “Warfun Project Description.” Accessed July 20, 2023. https://www.cmi.no/projects/2535-erc-war- and-fun.

- Deleuze, G. 2000. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. London: The Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, G. 2006. Nietzsche and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. 1986. Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Derland, M. 2022. “Elitsoldater tvingas köpa egen utrustning för 25 000”. Dagens Nyheter. Accessed on October 10, 2022. https://www.dn.se/sverige/elitsoldater-tvingas-kopa-egen-utrustning-for-25-000/.

- DoD. 2007. U.S. Army Ranger Handbook. New York, NY: Skyhorse Pub.

- Duncanson, C. 2013. Forces for Good? Military Masculinities and Peacebuilding in Iraq and Afghanistan. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.