ABSTRACT

Responding to New Wars, international organizations have faced challenges in increasing synergies between civilian and military instruments. This paper analyses civil-military synergies as a logical framework outcome of coordination and asks to what degree activities of civil-military coordination in EU external action has led to synergies on the ground. It provides a conceptual framework tackling three distinct conceptual challenges; (1) providing a typology of interfaces to articulate civil-military research scope(s), (2) delimiting the “civil-military”, and (3) defining civil-military synergy vis-á-vis coordination. The framework is applied in a case study of EU engagements under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) focusing on EU’s operational level during the execution phase. It finds that EU’s siloed command structure hampers coordination between instruments to a degree where civil-military synergies are more common with external partners than between CSDP instruments, and that open mandates to coordinate with “relevant actors” are vulnerable to personal interpretations.

Introduction

The dispersed and protracted nature of New Wars (Kaldor, Citation1998) has required the international community to bring together a myriad of instruments and develop strategies for orchestrating these into coherent responses. Chief among them has been the need for effective coordination of civilian and military instruments to navigate system-wide or whole-of-society interventions ranging from security and governance to economic and social engagements in conflict-affected societies. Although more than a decade has passed since the United Nations initiated its first integrated mission,Footnote1 governments and international organizations continue to struggle to find the silver bullet for enhancing civil–military coherence (see Juncos, this issue). Previous research suggests this in part due to overstretched ambitions for what could and should be coordinated (de Coning & Friis, Citation2011) as well as the complexity and unclear conceptualizations of the field itself (Jayasundara-smits, Citation2016). This article attempts to redress the latter of these challenges by using a clearer conceptual approach to analyse the pursuit of civil–military synergies in current missions and operations under the European Union’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP).

Within the EU, civil–military synergy has been a clear policy objective since the inception of the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and in largely every strategy of coherence thereafter (e.g. EUGS, Citation2016; European Commission, Citation2013). Regardless, it has remained a sparingly theorized and operationally elusive concept that has so far escaped academic definition at the operational level (Jayasundara-smits, Citation2016, p. 4). Previous research on civil–military coordination in EU has engaged the strategic and political levels, often with an emphasis on pre-deployment planning and capability development (e.g. Hynek, Citation2010, Citation2011; Ioannides, Citation2010; Norheim-Martinsen, Citation2010; Toussaint, Kammel, & Hyttinen, Citation2017), and while many studies have engaged the operational level of CSDP they have rarely had a direct focus on civil–military relations on the ground. When civil–military relations have been discussed, it has then often been with a focus on activities of coordination more than operational synergies (e.g. Dijkstra, Mahr, Petrov, Đokić, & Zartsdahl, Citation2017; Ejdus, Citation2018; Metcalfe, Haysom, & Gordon, Citation2012; Norheim-Martinsen, Citation2013, Chapter 4; van der Borgh, le Roy, & Zweerink, Citation2017, pp. 19–20). This may in part be explained by the close links between activities of coordination and indicators related to dimensions of organizational interactions (See Dijkstra, Citation2017).

There is a consensus in previous studies, though, that coordination needs to improve, but details have been lacking in identifying the exact interfaces where it falls short and the operational adaptations that should have been. This has left civil–military coordination and the resultant synergies as a key challenge in EU practice. To further the study of civil–military synergies, three conceptual challenges should be addressed; (1) providing a typology of interfaces to specify civil–military research scope(s) in an increasingly complex field, (2) delimiting the “civil–military” and (3) defining synergy vis-à-vis coordination.

The following article, therefore, provides a typology for mapping civil–military interfaces across four types of civil–military relationships, four levels of interfaces, and three phases of engagement. It further applies an operationalized definition of civil–military synergies as an outcome of coordination in these interfaces to identify when coordination has yielded an adaptation of operations. Based on these adaptations, outcomes manifested as either reducing duplicate efforts and costs or increasing overall impact may then be identified as synergies.

In the second part of the article, the framework is applied in an empirical case study of EU external action, analysing civil–military synergies at the operational level during the execution of EU crisis management missions and operations in two diverse cases; the Western Balkans and the Horn of Africa. It analyses the degree to which EU CSDP missions and operations have pursued civil–military synergies in ongoing deployments and whether positive activities of coordination has yielded tangible synergies on the ground.

Conceptualizing civil–military synergies

A typology of civil–military interfaces

The organized study of civilian and military interfaces originates in Samuel Huntington (Citation1957) and Morris Janowitz' (Citation1960) toils with the dichotomy between developing strong militaries for the protection of democratic states while ensuring that the same militaries do not assume control of the state itself. From their seminal field of civil–military relations have sprung numerous studies expanding the original question of state protection to include strategies of cooperation and coherence between civilian and military agencies within states (e.g. Croissant, Chambers, Wolf, & Kuehn, Citation2011; Egnell, Citation2013), within international organizations (e.g. de Coning, Citation2008; Norheim-Martinsen, Citation2010; Quille, Gasparini, Menotti, & Pirozzi, Citation2006), and between independent uni- and multilateral actors (Goodhand, Citation2013; Metcalfe, Giffen, & Elhawary, Citation2011; Olsen, Citation2011; Sowers, Citation2005; Tatham & Rietjens, Citation2016). The variety of studies alone demonstrate that the complexity of modern peace operations has moved civil–military interfaces far beyond the intra-state perspective and into a much more complex web of relationships that are not always clearly defined. de Coning and Friis (Citation2011) put forward a framework for analysing types of relationships in strategies of coherence, that also holds utility for the study of civil–military synergies. They provide a typology of four relationships which aptly describes the environments and first variable where civil–military interfaces and potential synergies exist; (1) intra-agency, (2) whole-of-government, (3) inter-agency and (4) international–local (de Coning & Friis, Citation2011, pp. 253–254).Footnote2 In addition to the four types of relationships this paper argues that each civil–military interface can take place at a given institutional or organizational level; (a) political, (b) strategic, (c) operational and (d) tactical. While these labels are in common use, they do somewhat overlap and often carry varying delimitations among different agencies. For example, in many cases the police and civilian agencies subsume the militaristic tactical level into the operational, and for many international organizations the strategic and political level boundaries are blurry at best. A third and last variable to describe civil–military interfaces is that of the operational phase in which it takes place. These may be articulated in a variety of formats depending on the environment researched, but typically from either an actor (e.g. capability development, planning, execution, transition) or target perspectives (e.g. steps of the conflict cycle). For the purpose of studying civil–military synergies in EU crisis management three phases are considered; (i) planning and preparation, (ii) execution and (iii) transition and withdrawal with a focus on the execution phase for identifying civil–military synergies on the ground.

Delimiting the civil–military

A second conceptual challenge in studying the “civil–military” is the delineation of “military”. In most literature this is implicitly understood as uniformed military personnel of a recognized national or international military force. This definition is sufficient when studying intra-agency or whole-of-government relationships where civilian and military institutions under a shared political leadership agree on its boundaries (including, e.g. the role of gendarmerie and national para-militaries). It faces challenges, however, when applied to inter-agency and international–local relationships where perceptions may differ between the sides of any civil–military relationship. One such example is the inter-agency relationships between integrated peacekeeping and crisis management missions and the humanitarian community, where the latter (including UN agencies) tend to consider any political missions’ civilian offices and personnel as “military”, and thus navigate relationships in accordance with Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) guidelines (Citation2008) regardless of the “uniformed” status of individuals. This interface becomes less rigid in non-complex emergencies such as natural disasters but leaves grey areas for instance in interactions with military missions of executive vs. non-executive mandates. For this reason, analysis of civil–military interfaces should not employ a rigid understanding of “military” actors but a relationship-dependent definition of maximal inclusion to consider what could traditionally be labelled civilian–civilian and military–military relationships when relevant.

Synergy as an outcome

As discussed above, previous research on civil–military interfaces have tended to focus on relationships and activities of coordination in civil–military interfaces; predominantly at the political and strategic levels, and on most but the international–local types of relationships. Civil–military synergy has thus existed mainly as an operational term with limited academic attention (Jayasundara-smits, Citation2016, p. 4). Notable exceptions include recent research by EU Horizon 2020 programmes such as Jayasundara-smits (Citation2016) and Toussaint et al. (Citation2017) that has outlined political and strategic level interfaces in all phases of EU intra-agency relationships, and the works of Dijkstra et al. (Citation2017) analysing the inter-agency relationships between EU and other international organizations with a view to civil–military coordination.

With civil–military synergies not clearly defined in academic terms, EU policy literature was reviewed for operational definitions. These are predominantly occupied with reducing resource expenditure and duplication of efforts in intra-agency relationships (e.g.: EEAS, Citation2014, Citation2015; PSC, Citation2009), with less emphasis on the more traditional etymological understanding of synergy as “produc[ing] a combined effect larger than the sum of [the actors’] separate effects” (Oxford English Dictionary, Citation2016). This wider understanding of increasing overall impact is instead mirrored in EU’s more general policies of coherenceFootnote3 (e.g.: EUGS, Citation2016; European Commission, Citation2013) articulating the need not just for reducing operational costs but also operating “coherently” at all levels and types of relationships to “have a greater impact and achieve better results” (European Commission, Citation2013, p. 8). To ensure utility across both policy sets, “civil–military synergy” is understood as a dyadic concept of cost-reducing and impact-increasing outcomes of civil–military coordination. The former is operationalized as “reducing duplicate efforts and costs”, whereas as the latter includes measures that “increase overall impact” which in many cases incur increased operational costs. An example of impact-increasing synergy is the mutual adaptation of systems and training across diverse fields of capacity building (e.g. judicial, police and military) to ensure that a host nation’s capacities are built with a degree of interoperability and capacity for transitions.Footnote4 The two sides of the concept are not mutually exclusive and indeed rare synergies exist that in first-tier effect both reduces expenditure and increases impact. The duality holds utility, however, when used in dialogue with practitioners to ensure broader responses and move beyond the one-sided interpretation dominating in field guidance.

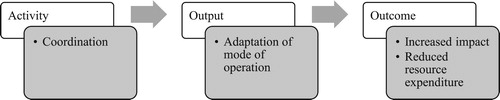

Finally, synergies should be understood within a simple logical framework (NORAD, Citation1999) as the outcome of civil–military coordination activities (). As previous research has engaged with strategies of coordination, much has focused on activities thereof, such as exchange of liaison officers, the conduct of regular meetings, information sharing, etc (See Biermann, Citation2008; Biermann & Koops, Citation2017). While this does indeed help to map important relationships and provide indications of their strength, a focus on coordination activities often passes over the resultant (or non-resultant) adaptation of modes of operation and the actual impact. An element addressed then in the study of civil–military synergies.

The key criterion for identifying civil–military synergy consequently is that an action of coordination must provide a tangible output which is an adaptation or change in the mode of operation by one or more parties which in turn – provided assumptions hold – results in either reduced resource expenditure or an increased impact by one or more parties to the coordination. In other words; if parties do not adjust their individual mode of operation as an output of coordination, synergy is not effectively pursued. Operationalizing the outcome design, we may therefore propose the following definition of civil–military synergies.

Civil–military synergy: An observable outcome of coordination by civilian and military instruments, distinguishable as reducing duplicate efforts and costs, or increasing coherence and impact for all parties. Proverbially; to make the whole larger than the sum of its parts.

In the following sections the conceptual framework outlined above is applied in the comparative study of (c) operational-level civil–military synergies by EU instruments of external action in the Western Balkans and the Horn of Africa during the (ii) execution of crisis management missions across their (1) intra-agency, (3) inter-agency and (4) international–local relationships (see ).

Table 1. A typology of civil–military interfaces.

Approach and methods

The framework was applied on two diverse (Gerring, Citation2012, p. 52) regional cases of EU military engagement; the Western Balkans and the Horn of Africa, to answer the degree with which the EU missions and operations under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) have pursued and established civil–military synergies. The cases differ across three key variables; (1) their perceived stages of conflict, (2) the historical length of EU structured engagement and (3) the types of civil–military relationships available to CSDP missions. Somalia and the Horn of Africa in is considered a complex emergency (see IASC, Citation2008; Keen, Citation2008) in which ongoing armed conflict provides restrictions on certain types of civil–military relationships, in particular to the humanitarian community, and where a number of military actors are engaged in similar and often overlapping tasks. In comparison, the Western Balkans is at a lower level of the conflict scale with a history of 15 years of EU engagement through CSDPFootnote5 but only two ongoing missions therefore dependent on inter-agency interfaces for civil–military synergies (see ). The research scope was limited to ongoing missions and operations during execution to (1) allow data collection to include observations, (2) to minimize recall bias in analysing policy implementation and (3) to supplement the existing literature where it is most wanting.Footnote6

Table 2. CSDP missions and operations in the two case studies.

For each case study, relevant civil–military interfaces for the study were identified with the active CSDP missions and operations as points of origin. From there, the closeness of tasks with other actors was analysed based on (1) mandated coordination,Footnote7 (2) sectors of engagement,Footnote8 (3) geography, (4) beneficiaries or host nation partners and (5) resource requirements.

Twenty-seven semi-structured interviews with associated observations were conducted with EU staff (CSDP and delegations; intra-agency), African Union (AU), United Nations (UN) and other international (inter-agency) stakeholders as well as host nation (international–local) partners in Kosovo, Bosnia and Hercegovina (BiH), Somalia and Kenya. Data collection and analysis aimed to identify (1) formal structures for coordination in civil–military interfaces and their outcomes, (2) informal and ad hoc attained civil–military synergies and (3) currently unexploited potentials for civil–military synergies. All interviewees were introduced to the dual conceptualization of synergies in a discussion of the three themes above. Furthermore, a list of eight areas of potential civil–military synergies was provided in the final stages of each interview for confirmation of activities conducted on each. The eight areas are logistic support, Communications and Information Systems (CIS), medical support, security and force protection, information sharing, intelligence, contracting, and lessons learned. While the list is not exhaustive, these are areas with current potential for synergies as specified by the EEAS (Citation2014).

Western Balkans

Ongoing EU CSDP missions and operations in Western Balkans include the civilian rule of law mission, EULEX, in Kosovo and the military operation EUFOR Althea in BiH (see Peen Rodt et al., Citation2017, pp. 30–35). Both missions carry a combination of capacity building and executive mandates albeit in two different sectors; law and order, and security, respectively. Civil–military interfaces therefore mainly exist in inter-agency and international–local relationships; with the exception of intra-agency relations between EUFOR and the EU Special Representative (EUSR), the Office of the High Representative (OHR), and EU delegation in BiH. In both countries, cooperation with NATO and UN has been historically strong as EUFOR Althea was established under the Berlin Plus agreementFootnote9 and assumed responsibilities of the former NATO Stabilisation Force (SFOR) and EULEX is still working side by side with the NATO Kosovo Force (KFOR) military peacekeeping mission in Kosovo and the United Nations Interim Mission (UNMIK).

Formal structures for coordination and their outcomes

In BiH, intra-agency relationships exist between EUFOR and the EUSR, who remains responsible for coordinating all EU actors in the field. The EUFOR Force Commander is correspondingly explicitly tasked to “take into account” the local political advice provided by the EUSR (Council of the European Union, Citation2007). This interface has been coordinated through the political advisor to the Force Commander, who is also embedded in the office of the EUSR, and through biweekly meetings between the Force Commander and the EUSR (Interview 2). EUFOR has a liaison officer embedded with the Office of the High Representative (OHR), but most coordination in this relationship takes a less formal form (Interview 3). The OHR oversees biweekly Board of Principals meetings attended by EUFOR to facilitate information sharing and avoid overlapping efforts between actors, but the meetings fall short of forward-looking frameworks for sharing conflict risk analyses or assessments of ongoing security developments, internally (intra-agency) and with external (inter-agency) partners (Interview 1).

For international–local relationships, EUFOR have established a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the host nation’s Ministry of Security and a total of 17 host nation law enforcement agencies on the exchange of information and intelligence (EUFOR, Citation2013). Furthermore, EUFOR includes 17 liaison and observation teams deployed in 16 team-sites across the country engaging with local communities to provide observations and reporting to the EUFOR headquarter.

In Kosovo, EULEX has established several formal mechanisms for coordinating the inter-agency civil–military interface to NATO/KFOR. This is explicitly mandated as “works closely and coordinates with the competent Kosovo authorities and with relevant international actors […] including NATO/KFOR [and] third states involved in the rule of law in Kosovo” (Council of European Union, Citation2008, Art. 8.). An MoU has been established for inter-agency response mechanisms to riots, exchange of information, and military (KFOR) support for police operations (van der Borgh et al., Citation2017, p. 19). The MoU has, however, been faced with critique, as its practical implementation has been with varied success at best. De facto responses and mutual support have been unreliable and characterized by mistrust and tit for tat failures to deliver (Interview 4 and 8; Collaku, Citation2011; Group for Legal and Political Studies, Citation2013).Footnote10

In more practical terms, the coordination between EULEX and KFOR is established through the formal exchange of liaison officers, and regular meeting schedules (Interviews 4 and 5). Similar constructs bind together the operational-level leadership of most international organizations in Kosovo, including UNMIK, the EU Office and OSCE. They are, however, all aimed at information sharing, and no steps have been taken towards joint planning, threat assessments or similar adaptations (Interviews 4, 6 and 7). When directly asked about tangible synergies as an outcome of these formal coordination activities, respondents were rarely able to provide any, and one expressed with dismay that most mechanisms had been established for the sake of their “existence” rather than out of any practical interest in cooperating or adapting in the inter-agency relationships (Interview 1 and 4).

Between EULEX and KFOR three observable areas of inter-agency civil–military synergies have been established: (1) Sharing of information and intelligence including threat assessments (cost-reduction, Interview 5), (2) Security and force protection from KFOR to EULEX in case of emergencies (cost-reduction) and (3) Training and exercise through joint exercises with Kosovo Police, Security Force (KSF) and the Emergence Management Agency to strengthen interoperability (impact-increasing). While formal mechanisms for coordinating across the inter-agency civil–military interfaces are well-established, they appear weaker in reality than on paper, and the parties have been found to regularly withhold information from each other in spite of formal exchange mechanisms (Interview 8).

Informal and ad hoc civil–military synergies

The EU engagement in Kosovo offers limited examples of informal civil–military synergies, while several were found in CSDP practice in BiH, many of which have in time become formalized. A compelling example is the role established by EUFOR in the post-war disposal of surplus Ammunition, Weapons and Explosives (AWE). Originally mandated to keep record and supervise on the stockpiling of AWE, it became clear that the Armed Forces of Bosnia and Hercegovina (AFBiH) did not have sufficient capacity for lifecycle management and demilitarization of AWE (Carapic, Chaudhuri, & Gobinet, Citation2016). EUFOR in cooperation with the EUSR, therefore, proposed ways of improving storage and disposal through stronger inter-agency coordination (Interview 2). The multi-agency effort coordinated by EUFOR culminated in a Master Plan on Ammunition, Weapons and Explosives issued by the BiH Ministry of Defence (MoD) in 2013. The plan establishes a high-level strategic board for quarterly streamlining of priorities of actions and financing between the host nation and leading international actors. Below the strategic board, a coordination committee of project managers from the international actors involved in AWE coordinates the work and projects on the ground. In this structure civilian agencies and specialists play a key role in supplementing the military capabilities with high-level expertise for instance in human security (Interviews 9 and 10) and with capacity for more flexible responses than the military (Interview 10). This dual-level civil–military coordination with an EU military lead has allowed each actor to specialize in niches and significantly reduce duplicate efforts. It has also allowed for a flexible transfer of responsibilities between actors with several examples of partners referring external donors to other members of the structure with more fitting profiles or expertise (Interview 10). What was initially an ad hoc attempt to solve a mounting problem of lacking host nation capabilities was thus over a period of three years transformed into an effective structure delivering multiple inter-agency civil–military synergies well beyond its original scope.

Attempts have been made to transfer some of the successful practice within AWE to demining – another multi-actor area, where inter-agency coordination has been lacking (Interview 2). EUFOR and EUSR have recently initiated a resurvey project, funded through the Instrument Contributing to Stability and Peace (ICSP), to provide the foundation for a new 2020–2025 demining strategy. EU instruments have been involved in demining in BiH since 2004, but only since the resurvey project has the EU as a single actor been perceived as “starting to do something” (Interview 10). This is a clear indication that leadership in inter-agency coordination is not only attractive from a functional perspective, but also a role that applies EU capabilities in a more high-visibility function.

In international–local relationships, and further to ad-hoc-cum-formalized mechanisms, EUFOR has contributed to emergency management and disaster relief during the 2014 floods through close cooperation with host nation civilian authorities in post-disaster reconstruction, much of which has been funded through the EU Floods Recovery Programme (EU Delegation to BiH, Citation2014). In addition, in the early phases of EUFOR employment, the mission cooperated closely with local law enforcement and police against organized crime in a relationship that, following critique (Juncos, Citation2013; Suhonen, Norvanto, Sainio, & Udovič, Citation2017), has taken a more informal format as intermittent support to joint exercises and local cooperation through the Liaison and Monitoring Teams (Zartsdahl & Đokić, Citation2018, p. 22).

In Kosovo, interviewees were unable to provide examples of ad hoc coordination and synergies between EULEX and KFOR or other relevant military partners. Instead, findings indicate that cooperation and functional interfaces are lacking even to the degree where EULEX and KFOR staff refrain from simple greetings when passing in the field (Interview 1).

Potential civil–military synergies

In general, the positive civil–military synergies achieved through the AWE structure has led interviewees to recommend a number of areas in which the model could be successfully copied as best practice. Chief among them is demining, where initial steps are already being taken, but also in international–local relationships with the law enforcement sector (fragmented by numerous host nation agencies) and inter-agency coordination of single policy domains like capacity building of the border police (Interview 10).

The LOTs regularly manage international–local relationships and cooperation with host nation police and local communities, but this social embedment is not utilized in intra-agency relationships to the EU delegation or the EUSR, where it could potentially inform joint reporting and conflict risk assessments (Interview 2). Improved horizontal cooperation directly with the LOTs in the field could likely improve the context-sensitivity of numerous civilian actors and staff in other EU instruments.

In Kosovo Security Sector Reform (SSR), including “strengthening the rule of law” has been specified as a key area of EU-NATO cooperation but engagements have so far been split clearly along the civil–military divide with KFOR and NATO focusing on Kosovo Security Forces and EULEX and EU working with the judiciary, police and customs administration. In the overall SSR process, numerous impact-increasing synergies could be pursued in creating interoperability between host nation agencies. This requires, however, that inter-agency relationships between EU and NATO are significantly strengthened on the ground as these are not currently pursued below the policy level.

Horn of Africa

EU CSDP missions and operations in the Horn of Africa include the executive military naval operation, EUNAVFOR Atalanta, aimed at countering piracy and increasing overall maritime security; the non-executive military training mission, EUTM Somalia; and the civilian maritime capacity building mission, EUCAP Somalia. External actors of relevance to the missions’ common mandates in the security and government sectors are the African Union peacekeeping Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) providing advice and peace- and state building to the Somali federal government and to AMISOM, and the UN Support Office (UNSOS) providing the logistical backbone for AMISOM and the Somali federal security institutions.Footnote11

Formal structures for coordination and their outcomes

In intra-agency relationships, EUCAP, EUTM and the EU delegation are all to a certain degree co-located in Mogadishu International Airport (MIA). EUTM and EUCAP are both located in the International Campus (IC) on the southern end of the airport, and a forward elementFootnote12 of the EU delegation is located in the northern end with a handful of EUCAP staff members due to lack of accommodation in the IC (Interviews 21, 23, 24 and 25). The EUCAP Deputy head of Mission maintains an additional office within the EU delegation compound and a liaison officer from EUNAVFOR is embedded in the EUCAP headquarter. In addition to the various co-locations and the exchange of liaison officers, the two missions and the delegation have established regular formal meeting schedules at Head of Mission (HoM), Head of Operations (HoO) and working group levels. Most of the coordination, however, relates to practical and political advice for engagements with Somali federal authorities and rarely, if ever, the pursuit of intra-agency civil–military synergies (Interviews 21 and 23).

As a very practical intra-agency cost-reduction synergy, EUNAVFOR has been assigned as the emergency evacuation mechanism for the EU delegation and CSDP staff in MIA, should a crisis arise. This is, however, a role in need of revision as the number of EUNAVFOR vessels have since been drastically reduced (Interviews 22 and 23). In addition, EUCAP and EUNAVFOR have established valuable impact-increasing civil–military synergies through a joint work plan and the embarkation of EUCAP staff and trainers on EUNAVFOR vessels to increase maritime situational awareness and access for the EUCAP civilian specialists. This cooperation has still stayed short of directly exchanging resources or doing joint reporting and is to some degree shaped by concern for future competitive mandating (Interview 21). In terms of logistics, medical support, intelligence, contracting, and communication the EU’s civilian and military instruments in the Horn of Africa have remained almost fully isolated from each other (Interviews 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 and 26). A situation at odds with the overall intent of the EU’s Comprehensive Approach (European Commission, Citation2013).

Extensive inter-agency coordination has been established between EUCAP, UNSOM and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) with an aim to anchor projects with the UN, should the time limited EUCAP mandate fail to be renewed (interviews 20 and 21). This is established through the Maritime Security Coordination Committee chaired by EUCAP where Somali authorities may present needs and requests to relevant partners which in turn is then prioritized and coordinated by donors. No similar structure has been found for the military capacity building in which EUTM is engaged and no inter-agency relationships have been found to span the civil–military gap for wider coordination of the capacity building across civilian and military host nation institutions.

EUTM, along with AMISOM, is included in the civil–military working group (CMWG) chaired by the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) tying in inter-agency civil–military relationships to the humanitarian community, and similarly both military actors are included in the Joint Operations Coordination Centre under the Somali ministry of Internal Security binding the international–local civil–military interface to all host nation security agencies. In both environments, EUTM has been seen as a less active and less contributing partner (Interviews 14, 16, 17 and 22), which has given ground for some critique on withholding of assets and capacities and slow responses to changes in otherwise dynamic environments (Interview 17, Matiiri, Citation2017).

In sum, a number of formal interfaces and coordination mechanisms have been established, but with notable successes only in the EUNAVFOR and EUCAP interface. Interviewees have indicated, that positive developments are underway in interfaces to EUTM due to a change in high-level leadership, explicating that outcomes of the formal coordination structures have been dependent on the personalities and “mindsets” of leaders. Their individual approaches have allowed for open – and in this case limiting – interpretations of the necessary extent and outcomes of civil–military coordination (Interview 23).

Informal and ad hoc civil–military synergies

Both in intra- and inter-agency relationships, interviewees provide examples of attempted ad hoc civil–military synergies but agree that few have succeeded. Generally, long and separate chains of command are blamed for a slow response to short-term needs and challenges (Interview 17, 22 and 24). Examples include the coordination of drought response in 2017 through the CMWG. It was noted that while the wider international community was scrambling to realign resources to an impending humanitarian crisis, EUTM in particular took quite long to adapt from a perspective of traditional NATO CIMIC projects at which time AMISOM had committed for most tasks and needs (Interview 17). Regardless of whether support from EUTM was feasible at the time – the perception from external partners, that responsivity is low, should be better managed, in part through more active participation and expectation management. A minor success in intra-agency cost-reduction synergy was found in the ad hoc availability of the EUTM role 1 medical clinic to EUCAP staff and medical officers. This synergy, however, had been borne of necessity as the EUCAP medical officer was accommodated in the EU delegation camp and therefore had no office or private space available for treating EUCAP staff in the IC (interview 24).

In inter-agency relationships, synergies appear more attainable, for instance in the civil–military interface between EUCAP and AMISOM, where ad hoc agreements on medical support and cooperation have been established (interview 24) and in the extensive cooperation between EUCAP, UNSOM and UNODC. The latter qualifies as civil–military only by second degree cooperation with EUNAVFOR, but is a cogent example of well-functioning inter-agency impact-increasing synergies.

Potential civil–military synergies

There is a high and unexploited potential for civil–military synergies of all types surrounding the EU instruments on the Horn of Africa, particularly in relationships to the EUTM. Commenting on the EEAS list of potential areas for synergies and whether any was shared between the two co-located missions, one interviewee put it clearly; “none of them. Absolutely none of them […] and I truly don’t understand why we can’t do it” (Interview 21). Simple cost-reduction synergies such as the passage in military vehicles by civilian staff has proven difficult (Interview 24 and 25), and the use of any resources for the benefit of other EU instruments have allegedly needed approval at Brussels level rather than by the missions’ operational leadership (Interview 22 and 23). The research has yielded no instances of shared reporting, documentation, lessons learned, intelligence, contracting, or accessible sharing of security and force protection measures across the EU’s intra-agency civil–military divide.

In international–local relationships, the EU instruments are commended by Somali government partners for the competence of staff and for their direct mandate delivery. They do, however, face criticism for a slow responsiveness to short-term needs and requests compared to several unilateral actors such as the US, Turkey and United Arab Emirates (UAE) (Interview 16, 18 and 19). At the same time interviewees in the Somali government lament the lack of multi-actor coordination and strain that the vast numbers of individual actors in – for instance – military capacity building puts on their limited resources and the resultant lack of oversight on their operations (Interview 18 and 19). Here, the EU and particularly EUTM have a potential for taking up responsibility for inter-agency coordination due to their perceived position as a competent and legitimate international actor in a complex multi-actor sector (Interviews 18 and 19).

Conclusions

Both case studies show that civil–military synergies at the operational level are mostly pursued through activities of coordination and formalization of relationships with a limited or no focus on the intended outcomes beyond having “shared information”. This is found to be mainly due to limited structural incentives for actors to adapt their individual mode of operation. There seems to be an assumption among mission leadership that regardless of the relationship type, the formalization of interactions will lead to civil–military synergies or at least fulfil the policy requirements to pursue them. The research indicates that this assumption is flawed, and only in very few cases were synergies found to be established without some form of agreed leadership in coordination. Those few cases were typically in overlapping mandates and most often with explicit tasks from the strategic level for the actors to cooperate on the ground – voiding the need for operational-level leadership.

Across all types of relationships, the case studies indicate that open mandates to “coordinate” may be interpreted differently depending on the individual leadership personalities. This points to a need for task-based directions, not just to coordinate – but to adapt in pursuit of larger regional objectives or in support of intra-agency partners.

The conceptual focus on civil–military synergies as an outcome of coordination brings to light indications, that impact-increasing civil–military synergies are more easily achieved in inter-agency relationships (e.g. EUFOR in AWE processes and EUCAP to AMISOM and UNSOM) than intra-agency in the EU (e.g. EUTM-S to EU delegation and EUCAP, and EUFOR LOTs to the rest of EU instruments). An observation that would easily be masked by the fact that organizational interactions and activities of coordination are more regular in intra-agency relations, but their outcome limited. The lack of intra-agency impact-increasing synergies may be an effect of field guidance’s common focus on cost-reduction but is also found to be influenced by the EU’s isolated chains of command at the operational levels.

Overall, the main challenge for moving beyond coordination activities in intra-agency civil–military synergies appears to be the stove-piped nature of the EU’s command structures. The general lack of a theatre or operational-level coordinator like the EUSR role in BiH effectively limits the exchange of resources between civilian and military capabilities on the ground and leaves decisions and priorities with the respective Heads of Mission or the Force Commander. In addition, a limited delegation of decision-making authority in resource sharing – particularly in the EU military chain of command – limits ad hoc local solutions from being flexibly established, even in cases where the mutual will is there. It is therefore likely that EU intra-agency civil–military synergies would benefit most from an effective integration of chains of command at the operational level, potentially imitating the structure of the UN country teams.

In international–local relationships few relationships are established if not explicitly mandated. There are significant benefits to be reaped from a more flexible and engaging approach to local actors and particularly local-level specialists when it comes to political and conflict risk analysis. International–local engagement has been marginally better in Western Balkans, most likely due to a prolonged presence and overall higher local capacity than in the Horn of Africa. There is, however, still room for improvement as seen in the limited operationalization of the EUFOR LOTs in BiH. In both inter-agency and international–local relationships there are options for the EU’s instruments to step up and assume leadership roles in multi-actor coordination with the AWE structure as a best practice.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on findings established during the work on EU-CIVCAP (Preventing and Responding to Conflict: Developing EU Civilian Capabilities for a Sustainable Peace; EU H2020 grant agreement 653227) deliverable 5.3 “Report on Civil–military Synergies on the Ground”. I am very grateful to all EU-CIVCAP partners for their support in developing the original report, but especially indebted to Ms. Katarina Đokić of the Belgrade Center for Security Policy for overseeing the data collection and initial analysis for the Western Balkans case study and to Ms. Savannah Simons of Transparency Solutions in Hargeisa for tirelessly providing vital feedback and support during my own field research on the Horn of Africa. Without their invaluable contributions this work had not been possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Peter Horne Zartsdahl is a PhD Fellow at the Department of Social Sciences and Business at Roskilde University where his research focuses on civil–military interfaces in multidimensional peace operations. He holds an MA in African Studies from University of Copenhagen and previously served as a major and civil-military coordination officer for the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. He is the acting work package leader for EU-CIVCAP work package no. 5 researching the execution and implementation of Common Security and Defence Policy missions and operations on the Horn of Africa and Western Balkans.

ORCID

Peter Horne Zartsdahl http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4744-2549

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste, mandated in 2006.

2. In the original work, Coning and Friis label the four “levels of coherence”. To avoid confusion with operational and strategic levels and the projection of a (levelled) hierarchy of interfaces, this article will refer to the four as “types of relationships”. It also applies a wide interpretation of the EU and UN as single agencies for civil–military interfaces rather than “whole-of-government”, though arguments could be made for either label to be appropriate.

3. Among all instruments of external action as opposed to only the civil–military relationships.

4. For further examples see Zartsdahl & Đokić, Citation2018.

5. Though originally named European Security and Defence Policy (ESDC)

6. The current research gap being (c) operational and (d) tactical levels during (ii) execution and (iii) transitions.

7. That is civil–military relationships specified in mission mandates and policy such as between military CSDP instruments and the EU delegations.

8. Based on five sectors of intervention; security, law and order, government, economy and society (Ramsbotham, Woodhouse, Miall, Citation2016).

9. Permitting the use of NATO assets.

10. See also Zartsdahl & Đokić, Citation2018. pp. 17–20.

11. Including Somali National Armed Forces (SNAF) and National Police (SNP).

12. The rest of the EU delegation is still located in Nairobi, Kenya along with an EUCAP “back office” (Interview 21).

13. After de Coning & Friis, Citation2011

14. Typology adapted from Smith (Citation2017, p. 35).

References

- Biermann, R. (2008). Towards a theory of inter-organizational networking The Euro-Atlantic security institutions interacting. 151–177. doi:10.1007/s11558-007-9027-9

- Biermann, R., & Koops, J. A. (Eds.). (2017). Palgrave handbook of inter-organizational relations in world politics. London: Palgrave MacMillan UK.

- Carapic, J., Chaudhuri, P., & Gobinet, P. (2016). Sustainable stockpile management in Bosnia and Herzegovina: The role of EUFOR mobile training team for weapons and ammunition management. Working Paper 24. Geneva: Small Arms Survey.

- Collaku, P. (2011, August 31). Weapons seized by EULEX in Northern Kosovo. Balkan Insight.

- Council of European Union. (2008). Joint Action 2008/124/CFSP of 4 February 2008 on the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo, EULEX Kosovo. Official Journal of the European Union, L 42/92. http://doi.org/2008/124/CFSP.

- Council of the European Union. (2007). Council Joint Action amending Council Joint Action 2004/570/CFSP on the European Union military operation in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Doc. no.: 14618/07). Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Croissant, A., Chambers, P. W., Wolf, S. O., & Kuehn, P. (2011). Conceptualizing civil-military relations in emerging democracies. European Political Science, 10(2), 137–145. doi:10.1057/eps.2011.2

- de Coning, C. (2008). The United Nations and the comprehensive approach. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS.

- de Coning, C., & Friis, K. (2011). Coherence and coordination The limits of the comprehensive approach. Journal of International Peacekeeping, 15(1), 243–272. doi:10.1163/187541110X540553

- Dijkstra, H. (2017). The rational design of relations between intergovernmental organizations. In R. Biermann, & J. A. Koops (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of inter-organizational relations in world politics (pp. 97–112). London: Palgrave MacMillan UK.

- Dijkstra, H., Mahr, E., Petrov, P., Đokić, K., & Zartsdahl, P. H. (2017). Partners in conflict prevention and peacebuilding: How the EU, UN and OSCE exchange civilian capabilities in Kosovo, Mali and Armenia. Brussels: EU-CIVCAP (EU H2020 Grant agreement no.: 653227).

- EEAS. (2014). European Union concept for EU-led military operations and missions (Doc. no. 17107/14). Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- EEAS. (2015). EUMC glossary of Acronyms and Definitions Revision 2015 (Doc. no. 6186/16). Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Egnell, R. (2013). Civil–military coordination for operational effectiveness: Towards a measured approach. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 24(2), 237–256. doi:10.1080/09592318.2013.778017

- Ejdus, F. (2018). Local ownership as international governmentality: Evidence from the EU mission in the Horn of Africa. Contemporary Security Policy, 39(1), 28–50. doi:10.1080/13523260.2017.1384231

- EU Delegation to BiH. (2014). EU floods recovery programme. Retrieved from http://europa.ba/?page_id=541

- EUFOR. (2013). EUFOR and BiH law enforcement agencies sign memorandum of understanding on exchange of information. Retrieved May 23, 2018, from http://europa.ba/?p=18890

- European Union Global Strategy (EUGS). (2016). Shared vision, common action: A stronger Europe - A global strategy for the European Union's Foreign And Security Policy. Brussels: European Union External Action Service (EEAS).

- European Commission. (2013). The EU’s comprehensive approach to external conflict and crises. Brussels: European Commission and High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

- Gerring, J. (2012). Social science research: A unified framework (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goodhand, J. (2013). Contested boundaries: NGOs and civil-military relations in Afghanistan. Central Asian Survey, 32(3). doi:10.1080/02634937.2013.835211

- Group for Legal and Political Studies. (2013). Rock and rule: Dancing with EULEX. Pristina: Kosovo Foundation for Open Society.

- Huntington, S. P. (1957). The soldier and the state: The theory and politics of civil-military relations. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Hynek, N. (2010). Consolidating the EU’s crisis management structures: Civil-military coordination and the future of the EU OHQ. Brussels: DG EXPO Policy Department.

- Hynek, N. (2011). EU crisis management after the Lisbon Treaty: Civil–military coordination and the future of the EU OHQ. European Security, 20(1), 81–102. doi:10.1080/09662839.2011.556622

- IASC. (2008). Civil-Military guidelines & reference for complex emergencies. New York, NY: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA).

- Ioannides, I. (2010). EU civilian capabilities and cooperation with the military sector. In E. Greco, N. Pirozzi, & S. Silvestri (Eds.), EU crisis management: Institutions and capabilities in the making (pp. 29–54). Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali.

- Janowitz, M. (1960). The professional soldier: A social and political portrait. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Jayasundara-smits, S. (2016). Civil-Military synergy at operational level in EU External Action – WOSCAP Deliverable 4.11: Best practices report: Civil-military synergies. Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict.

- Juncos, A. E. (2013). EU foreign and security policy in Bosnia: The politics of coherence and effectiveness. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Kaldor, M. (1998). New & old wars: Organized violence in a global era (2nd (2006)). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Keen, D. (2008). Complex emergencies. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Matiiri, A. (2017). Briefing on the AMISOM case by Brigadier General Matiiri. Landward Security Governance in Africa: The AMISOM case (29-09-2017). Addis Ababa: Fifth Biennial Conference on Strategic Theory.

- Metcalfe, V., Giffen, A., & Elhawary, S. (2011). UN integration and humanitarian space: An independent study integration steering group. Humanitarian Policy Group - Overseas Development Institute.

- Metcalfe, V., Haysom, S., & Gordon, S. (2012). Trends and challenges in humanitarian civil-military coordination: A review of the literature. London: Humanitarian Policy Group – Overseas Development Institute.

- NORAD. (1999). The logical framework approach (LFA) - Handbook for objectives oriented planning. Oslo: Author.

- Norheim-Martinsen, P. M. (2010). Managing the civil-military interface in the EU: Creating an organisation fit for purpose. EIOP European Integration Online Papers, 14(SPEC. ISSUE 1), 1–20. doi:10.1695/2010010

- Norheim-Martinsen, P. M. (2013). The European Union and Military Force: Governance and strategy. European security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1080/09662839.2017.1353973

- Olsen, G. R. (2011). Civil-military cooperation in crisis management in Africa: American and European Union policies compared. Journal of International Relations and Development, 14(3), 333–353. doi:10.1057/jird.2011.6

- Oxford English Dictionary. (2016). Oxford Dictionary of English.

- Peen Rodt, A., Tvilling, J., Zartsdahl, P. H., Ignatijevic, M., Gajic Stojanovic, S., Simons, S., … Arguedas, V. F. (2017). Report on EU conflict prevention and peacebuilding in the Horn of Africa and Western Balkans. EU-CIVCAP.

- PSC. (2009). Promoting synergies between the EU civil and military capability development (15475/09). Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Quille, G., Gasparini, G., Menotti, R., & Pirozzi, N. (2006). Developing EU civil-military co-ordination: The role of the new civilian-military cell. Brussels: ISIS Europe and CeMiSS.

- Ramsbotham, O., Woodhouse, T., & Miall, H. (2016). Contemporary conflict resolution (4th ed.). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Smith, M. E. (2017). Europe's common security and defence policy: Capacity-building, experiential learning, and institutional change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sowers, T. S. (2005). Beyond the soldier and the state: Contemporary operations and variance in principal-agent relationships. Armed Forces & Society, 31(3), 385–409. doi:10.1177/0095327X0503100304

- Suhonen, J., Norvanto, E., Sainio, K., & Udovič, B. (2017). IECEU Bosnia and Hercegovina review. Helsinki: IECEU Project (EU Horizon 2020, Grant agreement no.: 653371).

- Tatham, P., & Rietjens, S. B. (2016). Integrated disaster relief logistics: A stepping stone towards viable civil-military networks? Disasters, 40(1), 7–25. doi:10.1111/disa.12131

- Toussaint, M., Kammel, A., & Hyttinen, K. (2017). The potential for pooling and sharing EU capabilities. Brussels: IECEU Project (EU Horizon 2020, Grant agreement no.: 653371).

- van der Borgh, C., le Roy, P., & Zweerink, F. (2017). EU peacebuilding capabilities in Kosovo after 2008: An analysis of EULEX and the EU-facilitated Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue. Utrecht: Whole of Society Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding (WOSCAP, EU H2020 Grant agreement no.: 653866).

- Zartsdahl, P. H., & Đokić, K. (2018). Report on civil-military synergies on the ground. EU-CIVCAP (EU H2020 Grant agreement no.: 653227).