ABSTRACT

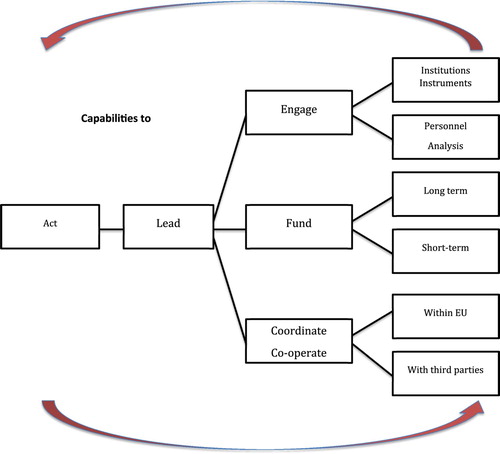

Conflict prevention is a primary objective of EU external action (European Council, 2011). This article analyses how EU actors understand “conflict prevention” and finds the term is used to mean both a way in which the EU acts in the world, and also a set of discrete activities: conflict analysis, early warning and mediation. Adapting Whitman and Wolff, the article analyses EU capabilities for both concepts of “conflict prevention”: to engage, to fund, and to coordinate and cooperate, which contribute to the capabilities to lead and to act. The article demonstrates extensive EU capabilities to engage, to fund and to coordinate and cooperate with third parties in preventing conflict. However, challenges remain, particularly the lack of conceptual clarity on “conflict prevention”, leadership, internal coordination and cooperation, and the prioritization of early preventive action, based on early warning, over response to conflicts that have already escalated. The article closes by suggesting ways to mitigate these challenges.

Introduction

In 2011, the Council of the European Union (EU) declared that “[p]reventing conflicts and relapses into conflict … is therefore a primary objective of the EU’s external action” (Council of the European Union, Citation2011). Drawing on the scholarship that examines the roles of values in the EU’s relations with the wider world (Manners, Citation2002; Smith, Citation2010; Whitman, Citation2011), and the principled pragmatism of the EU Global Strategy (EUGS) (Juncos, Citation2016), this article analyses what “conflict prevention” means for the EU, and how the intention of preventing conflict is translated into policy and put into practice by critically assessing the EU’s capabilities for conflict prevention.

The first section examines how “conflict prevention” is used by EU actors to mean both conflict prevention as a way in which the EU engages with the rest of the world, and as a set of distinct activities, particularly, conflict analysis, early warning and mediation. The second part examines EU capabilities for conflict prevention – both as a way of acting in the world and as distinct activities. In doing so, it identifies challenges in bridging the gap between early warning and early response, and opportunities for overcoming these.

There is considerable literature on determining EU capabilities or capacities for external action (EU-CIVCAP, Citation2016). This article adapts the model developed by Whitman and Wolff (Citation2012) to examine EU capabilities to engage, to fund, and to coordinate and cooperate with third parties. It is argued here that these three capabilities contribute to the capability to lead, which in turn feeds the capability to act – that is, to prevent conflict.

“Conflict prevention” and the EU

Since the publication of the UN/World Bank study Pathways to Peace (UN, World Bank Group, Citation2018), “conflict prevention” is, at the time of writing, high on policy agendas, particularly within the UN system. EU member states and institutions are increasingly concerned with countering violent extremism, counter-terrorism and stemming migration and these policy areas may intersect with and/or compete with “conflict prevention”, as is discussed below. EU engagement with “conflict prevention” pre-dates these developments. This makes understanding, rather than assuming, how EU policies and actors understand “conflict prevention” a pre-requisite for assessing EU conflict prevention policy and practice. This article unpacks how “conflict prevention” is understood in EU documents to throw light on the type of “conflict” EU actors may wish, expect or decline to respond to.

“Conflict prevention” can be understood – seemingly simply – as taking steps to ensure that conflict does not happen. This leads to the question: what kind of conflict is the EU trying to prevent? Analysis of key EU documents demonstrates an emphasis on preventing violent conflict, which requires critical reflection. These documents list a range of “root causes”, or structural conflicts that may culminate in violent conflict, and typically include poverty, marginalization, and abuse of human and civil rights, and/or the exclusion of particular groups on grounds of gender, ethnicity, religion or age (see, for example, European Commission, Citation2001). Preventing violent conflict, therefore, requires addressing underlying structural conflicts. In places where the “root causes” may have remained unchanged and largely unchallenged for some time, it is difficult to predict what causes violence to erupt in a particular time and place, and whether that violence then escalates further or dies down (Bossi, Dochartaigh, & Pisoiu, Citation2015; Diez, Albert, & Stetter, Citation2008).

The analyst’s understanding of what does and does not constitute a “root cause” will shape how a conflict is perceived: someone looking for evidence of ethnic tensions, for example, is more likely to then understand the conflict as an “ethnic conflict”, perhaps to the exclusion of other equally or more plausible causes. “Mainstreaming gender equality” sometimes appears alongside and therefore separated from “root causes” in EU documents. It is absent from the Gothenburg programme (European Council, Citation2001) and the Communication on the Comprehensive Approach (Commission and High Representative, Citation2013), and the EUGS refers to women in peace-making rather than gender equality (EEAS, Citation2016; European Union External Action Service, Citation2016). Structural violence against women and girls is, therefore, not considered a root cause despite its prevalence, revealing a blind spot in EU conflict analysis and early warning and therefore subsequent interventions (response).

Conflict is present in any human society, and conflict has driven many social movements pursuing universal values (such as equality) across the world. The distinction of “violent” may be useful shorthand for “bad” conflict: violence harms people, and human suffering should be limited as much as possible, but distinguishing “peaceful” or non-violent conflict (such as demonstrations and advocacy to change discriminatory laws) from violent conflict (e.g. rebellion) is often a question of political standpoint rather than objectively verifiable. Preventing (violent) conflict should not be synonymous with stabilization, for example: see the consequences of the EU’s past equation of stabilizing the neighbourhood with stabilizing authoritarian regimes (Noutcheva, Citation2016). Conflict prevention may contribute to stabilization and stabilization may contribute to preventing conflict, but stabilization may postpone or exacerbate future violent conflict by reinforcing structural violence and/or autocratic rule, for example.

The emphasis on preventing “violent conflict” in EU documents, therefore, uses a deceptively objective (“violent” or not) way of describing the political decision as to whether a conflict merits intervention, or not. After all, the EU cannot prevent all violent conflicts, or even the most violent. The insistence on violent conflict also leaves out important latent conflicts and key structural conflicts or root causes. For instance, some latent conflicts contained by geopolitics may not be violent (yet) but still pose a threat to international security and EU interests, such as the “frozen” conflicts in the former Soviet space. The EU may not be able to resolve these latent, non-violent conflicts, but preventing their escalation is in the EU’s interests.

EU conflict prevention may therefore be understood as addressing structural issues such as poverty and exclusion with the objective of structural transformation in the long term, the way in which the EU engages with and acts in the world (Interview #Citation3, Citation2016). Alternatively, it can be seen as a set of distinct activities, such as conflict analysis, early warning and mediation, to identify and address specific events and actors that may or may not, in the shorter-term, resort to violence in a particular place and time (Interview #Citation1, Citation2016), or indeed, as a combination both (Interviewee #2). It is through these two definitions – as a way of acting in the world and as a set of discrete activities – that this article considers EU conflict prevention. In both cases, conflict prevention is an intrinsically political activity, based on particular understandings of the power relations between different actors and stakeholders in a conflict and on prioritizing EU intervention in some form, or not, in relation to the EU’s interests.

There is evidence of the effectiveness of EU support for certain conflict prevention activities (European Commission, Citation2011) but it is more difficult to demonstrate the impact of “conflict prevention” as a way of acting in the world. Successful conflict prevention results in an absence of the expected (violent) event or process, even if proxy indicators, such as more resilient communities or more responsive institutions, may be used (with difficulty). There is a general lack of evidence of the EU’s impact on populations in non-EU countries (Noutcheva, Citation2009), including the EU’s contributions – positive or negativeFootnote1 – to preventing conflict worldwide, and it is nearly impossible to trace how the EU’s specific contribution(s) can be plausibly said to have played a part in preventing a particular outbreak of violence. Conflict prevention as a way of acting in the world therefore becomes “a matter of faith” and “fuzzy” (Interview #Citation2, Citation2016).

Member States are supportive of conflict prevention (Interview #Citation3, Citation2016) and there is a positive trend within the EU institutions to mainstream conflict prevention (Interview #Citation2, Citation2016). Conflict prevention is not something that policy-makers are against, but it does not automatically follow that policy-makers have a common understanding of what it entails in practice or a shared willingness to allocate resources to it, especially in the absence of evidence demonstrating its effectiveness (Interview #Citation3, Citation2016). The absence of a common conceptualization would appear, therefore, to present a serious challenge to EU conflict prevention.

Conflict prevention capabilities: policy and practice

To assess the EU’s capabilities for conflict prevention, this paper adapts the model on EU capabilities developed by Whitman and Wolff (Citation2012). This includes on one level the capabilities to engage, to fund and to coordinate and cooperate with third parties; on the next level the capability to lead; and at the highest level, the capability to act (2012), that is, to prevent conflict. Each of these key capabilities for conflict prevention is examined in turn.

The presumed likelihood of success of any intervention contributes to decisions to intervene in certain cases, which is in turn influenced by how well the various capabilities are perceived to be able to meet the challenges of a particular situation (see ) (Whitman & Wolff, Citation2012). This is a challenge if conflict prevention is seen as a matter of faith.

Figure 1. EU capabilities for conflict prevention.

Note: The external arrows denote presumed likelihood of success.

The following sections will analyse EU capabilities for conflict prevention, as a way of acting in the world and as discrete activities.

Capability to lead

Conflict is inherently political, so too, therefore is conflict prevention. The interests of the EU and its Member States determine the priorities of EU external action. LeadershipFootnote2 is crucial to successful conflict prevention (Interviews #1, 2, 3) and necessary at all levels of the bureaucracy for stimulating the development of capabilities, so that the tools are there if leaders decide to use them, and use them, or not, for preventing conflict. Leadership is therefore a capability in its own right and a component of the capability to act.

Political priority-setting is central to leadership. Conflict prevention is, ideally, pre-emptive rather than reactive and success does not lead to newspaper headlines. The EU has finite political, technical, financial and human resources to prioritize. The risk is that responding to (visible) crises exhausts resources and de-prioritizes preventive action; leadership is necessary to ensure that the urgent does not squeeze out the important.

The Gothenburg programme (2001) recognized the importance of political priorities for conflict prevention (European Council, Citation2001). It saw a central role for the Council in providing political leadership for conflict prevention, which has been significantly diminished with the creation of the EEAS. As a result, “conflict prevention does not surface often within Council formations, so the work of the EEAS within its mandate and with Commission resources is often below Member States’ radar” (Interview #Citation3, Citation2016). The Council Conclusions describe the “renewed impetus” the EEAS can bring to conflict prevention (Council of the European Union, Citation2011), but they do not transfer the political leadership described in the Gothenburg programme to the EEAS, reflecting unease among some Member States that the EEAS may take too strong a political leadership role. This suggests an important capability gap for conflict prevention.

Capability to engage

This section reviews the institutions and instruments (including policies), the personnel and analysis that enable the EU to engage.

Conflict prevention as an objective of EU external action was included in the Treaty on EU in 2008 (European Union, Citation2009, Art. 21.c) although the first conflict prevention policies were developed in 2001: the Gothenburg programme and the Communication from the Commission on Conflict Prevention (European Council, Citation2001; European Commission, Citation2001). The Council Conclusions on Conflict Prevention of 2011 state that conflict prevention is “a primary objective of the EU’s external action” (Council of the European Union, Citation2011), and lists areas of progress, including the adoption of the European Security Strategy and its implementation report, the Commission Communication on Conflict Prevention, policies on dialogue and mediation, security sector reform, the security and development nexus and situations of fragility. The Conclusions notes that early warning capabilities need to be strengthened, and early action – including through mediation – improved, and that the creation of the European External Action Service (EEAS) will enable more comprehensive approaches to conflict (Council of the European Union, Citation2011).

Whether political leadership for conflict prevention sits with the Council or EEAS, if conflict prevention is understood as a way in which the EU acts in the world, then most of the conflict prevention resources – the budgets, personnel, expertise of the context and influence over third parties – lies with the Commission, and not just those parts (such as the Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development, DG DEVCO) traditionally associated with conflict-prevention-as-activities but also at least the Directorate-Generals for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR), Energy (DG Energy), Trade (DG Trade) and Migration and Home Affairs (DG HOME). This brings us back to the discussion, ongoing since Lisbon, about the status and roles of the EEAS, the Commission and Council. Interviewees clearly stated that they felt that institutions and individuals across the EU are willing to work together on conflict prevention (Interview #Citation3, Citation2016). Willingness to work together is difficult to quantify but is nonetheless a form of capability to engage that both creates and demands political leadership, and which may partially overcome the challenge of institutional fragmentation. It is surely insufficient in itself, however, to provide the necessary political leadership.

The EUGS provides insights here into the EU’s foreign policy priorities. “An Integrated Approach to Conflict” is the third priority, after “The Security of our Union” and “State and Societal Resilience to our East and South” (EEAS, Citation2016; European Union External Action Service, Citation2016). This integrated approach to conflict includes “coherent use of all policies at the EU’s disposal”: “The EU will act at all stages of the conflict cycle, acting promptly on prevention” (EEAS, Citation2016, p. 7; European Union External Action Service, Citation2016). This language suggests that conflict prevention should be a priority. However, the use of “promptly” suggests a more reactive understanding of conflict prevention than one that prioritizes intervention to prevent (violent) conflict over the horizon, reinforced by the emphasis on the situations in Syria and Libya. This is not to argue that the EU should not respond to crisis: it is to underscore the importance of setting political priorities to prevent conflict by responding quickly to early warning before conflict escalates and not only respond to it and to recognize the difference between prevention and reaction.

The inclusion of an integrated approach to conflict as a priority in the EUGS should also be considered in the context of the other two priorities, the security of the Union, including strengthening the EU as a security community and counter-terrorism, and building resilience, including addressing migration. Conflict prevention should be central to all these policies, both in relation to their impact on third countries and to their likely success in their own terms. However, recent EU responses to migration have not taken the causes and drivers of conflict adequately into account and so EU interventions risk doing harm, increasing the likelihood of forced displacement, and therefore of irregular migration (Davis, Citation2016; Oxfam, Citation2015).

The EU has a range of personnel and analytical resources at its disposal for conflict prevention activities. Integrating conflict analysis into the EU’s external action has been identified as a key priority and the EUGS calls for making “all our external engagement conflict- and rights-sensitive” (EEAS, Citation2016; European Union External Action Service, Citation2016), but the personnel and time dedicated to these tasks are scarce. The EU is a donor with a low staff-to-budget ratio (EPLO, Citation2016) and there will be no staff increases in the foreseeable future (Interview #Citation4, Citation2016). This has significant implications for the extent to which conflict analysis can be generated and integrated into programming across the board (Interview #Citation4, Citation2016) and for how funding is allocated, as staff can devote less time and creativity to the way in which the budget is spent. The EEAS division SECPOL.2 and DG DEVCO’s Fragility and Resilience Unit (DEVCO B.7) developed a joint guidance note on using conflict analysis to help increase the conflict sensitivity of all EU funding instruments (EEAS, Citation2013). Yet officials, particularly those working on geographical instruments, are under pressure to disburse substantial funding envelopes; hence, the extent to which conflict sensitivity is sufficiently integrated remains unclear (Interview #Citation4, Citation2016). Some geographical teams, however, have specific personnel dedicated to supporting conflict-related activities, such as the technical support team on crisis reaction and security sector reform in DG NEAR B.2 Regional Programmes South.

In the EEAS, SECPOL.2 provided support to the rest of the EU machinery and manages technical interventions until it was replaced by the Prevention of conflicts, Rule of law/SSR, Integrated approach, Stabilization and Mediation (PRISM) entity in 2017. SECPOL.2/PRISM’s counterpart in the Commission, the DEVCO B.7 unit, has greater reach, with the potential to integrate conflict analysis into DEVCO’s work and across the European Commission’s broader external action. SECPOL.2 and B.7 have constituted important capabilities for EU conflict prevention, both as a way of acting in the world and as a set of distinct activities. Both provided specialist support to a range of EU actors in integrating conflict analysis as discussed below in relation to early warning and conflict analysis, mediation, and other conflict prevention activities. Since it replaced SECPOL.2 as part of a larger reorganization of the EEAS in 2017 (EEAS, Citation2017), PRISM may continue to provide these capabilities. However, PRISM appears to be more firmly subordinated to CSDP and crisis management – in other words, to short-term response rather than to long-term prevention – than was the case with SECPOL.2, which may reduce its conflict prevention capability.

Early warning and conflict analysis

The Early Warning System (EWS) is designed to enable EEAS, Commission and Member States staff in headquarters and in-country, with input from civil society, to identify and communicate long-term risks for violent conflict and/or deterioration in a situation and to stimulate early preventive actions to address these risks (EEAS, Citation2014). External observers note that the analysis it generates is useful and that although there is scope to increase the range of actors involved, particularly in-country (Interview #Citation2, Citation2016), it is more than a desk exercise (Interview #Citation1, Citation2016). The method includes light-touch analysis workshops, which gather new information and provide the basis for exchanges between the EEAS, Commission geographical experts and EU delegations that would not otherwise be available (Interview #Citation4, Citation2016). However, it is also argued that the impact of the workshops would be greater with more time and resourcing (Interview #Citation4, Citation2016).

In certain situations where a civilian CSDP mission is deployed, a Country Situational Awareness Platform will complement the EWS to “potentially facilitate sharing a common understanding of the situation at country level, and improve the combined situational awareness and analysis capacity by better linking up the dedicated facilities in the EU” (Commission and High Representative, Citation2016, p. 4). The extent to which this is used, and whether and how it affects how the EWS works in places where there is no CSDP mission remains to be seen.

EU delegations play important roles in contributing to analysis and in implementing interventions, whether directly (e.g. through political dialogue) or by supporting processes undertaken by others, and in developing and maintaining relationships with third parties. The delegations are underused, however, and the EU could “make better use” of them (EEAS, Citation2016, p. 4).

The main challenge for the EWS is the relationship between early warning and early action, which repeatedly surfaces in EU documents (Council of the European Union, Citation2011) and external analysis (Juncos & Blockmans, Citation2018) This highlights the importance of priority-setting for distributing finite resources among a long list of “at-risk” situations, and the potential problem that the urgent overshadows the important.

Mediation and dialogue

The Iran deal and the Belgrade/Pristina processes are high-visibility mediation successes for EU. Unlike conflict analysis and early warning, the development of the EU’s mediation capacity has been accompanied by specific policy, even if the Concept on Strengthening EU Mediation and Dialogue Capacities is, however, largely descriptive (Council of the European Union, Citation2009). It does not provide guidance for EU mediators, and it prioritizes mediation as a crisis management rather than a conflict prevention approach (Davis, Citation2014, pp. 69–71).

The Mediation Support Team in PRISM (EEAS) includes expert staff members tasked with mediation support initiatives and providing external expertise to meet EEAS mediation support needs. PRISM also works with non-governmental organizations to support processes on the ground, rather than to be in a more distant donor/grantee relationship.

Despite the progress in supporting mediation, the EEAS does little preventive diplomacy, which limits the EU’s ability to prevent conflict. This can sometimes be attributed to the difficulty Member States have in coming to an agreed position, a necessary pre-requisite for the EU to engage in preventive diplomacy, as in the case of Chad (Interview #Citation1, Citation2016).

Other conflict prevention tools

Beyond the EEAS, the EU has a range of other instruments including military and civilian CSDP missions and, in some conflict-affected regions, EUSRs. EUSRs report to both the EEAS and Member States – and so are an anomaly after Lisbon – yet they are probably not used to their full potential. European Parliament election observation missions are another underused tool, and have potential for preventive diplomacy in relation to election-related violence (Interview #Citation1, Citation2016). EU institutions can also call on the expertise and skills of its Member States.

This review suggests that the EU largely has the capabilities to engage. SECPOL.2, its successor PRISM, and the EEAS more broadly have an important role in providing technical support to the Commission and other parts of the EU machinery. The EU nonetheless needs to develop greater capabilities in preventive diplomacy and could make much better use of key instruments, including EUSRs and European Parliament election observation missions. It also suggests, however, that responsibility for conflict prevention needs to be situated strategically in the decision-making process at EEAS senior management level, so that prevention receives adequate resourcing and is not overshadowed by response.

Capability to fund

If we understand conflict prevention as a way the EU acts in the world, then potentially all of its external budget, and parts of the internal budget (provisions for counter-terrorism and stemming migration, for example) could fund conflict prevention.

The main sources of funding for specific conflict prevention activities, which are by their nature quite short-term, are the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP) and other thematic instruments, such as the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights or the thematic programme for Civil Society Organizations and Local Authorities of the Development Cooperation. The geographical instruments and the European Development Fund (EDF) can also support long-term and short-term conflict prevention activities in different parts of the world. The legal basis of these funding instruments provides for this option, but this does not mean that EU officials necessarily use these funds to support conflict prevention activities, as it is one option among others (EPLO, Citation2014). Quantifying exact amounts of funding is difficult: the budget for the IcSP is €2.3bn for 2014–2020 (EEAS, Citation2016), but this includes non-conflict prevention activities (see below). Conflict prevention activities may also be incorporated into Country Strategy Papers and funded through the EDF, and Member States may provide significant additional funding, depending on the situation and their interests. The EU can set up special mechanisms to support particular peace processes: the EU Trust Fund for Colombia, for example, has a budget of €95 m, including contributions from 19 Member States (EEAS, Citation2018).

While there is no lack of potential funding for conflict prevention, existing conflict prevention funds are coming under pressure, partly because of the increased priority of stemming migration into Europe. The IcSP crisis response component has been used to fund the EU–Turkey agreement designed to prevent migration (Commission, 2018), for example. Moreover, the Commission, supported by several Member States, published a legislative proposal to amend the IcSP so that it can also fund non-lethal equipment for the militaries of partner countries (European Parliament, Citation2016). The source of funding for such additional costly activities has not been identified yet. The challenge for specific conflict prevention funding is how finite funding is allocated among competing priorities and whether officials choose to use the available funding in a conflict-sensitive way and/or to support conflict prevention activities.

Capability for cooperation and coordination

The EU is by nature a multilateral actor, and conflict prevention favours multilateralism over unilateralism. The EU engages with third parties from the UN and regional organizations, with non-EU states, and with local authorities, non-governmental organizations and other non-state actors, on the international stage, in the EU, outside the EU in regional and national capitals, and locally. This multilateralism is arguably a source of strength for EU conflict prevention (Davis, Citation2014), and the prioritization of conflict prevention within the UN system and the World Bank should help improve coordination too.Footnote3

Coordination and cooperation within the EU presents perhaps more of a challenge and is closely connected to the question of leadership discussed earlier. demonstrates the problems inherent in understanding conflict prevention both as a way of acting in external action and as a set of discrete activities.

The challenges of getting all Member States to agree a common policy in a given situation are a fact of EU foreign policy life. Intra-institutional tussles remain but some observers believe there is the necessary spirit of coordination and cooperation across the EU machinery regarding conflict prevention (Interview #Citation3, Citation2016).

The SECPOL.2 Division developed and provided key resources for other parts of the EEAS and European Commission and has created demand for its services. This has enabled greater cooperation and coordination across relevant parts of the system. The EWS, conflict analysis and process design were located in the same department until 2017, which favoured coordination (Interview #Citation2, Citation2016). Now that SECPOL.2 has been replaced by PRISM, it will be important to monitor the effects of separating these functions on coordination and cooperation.

Where “conflict prevention” is situated within the EEAS and the Commission is a component of cooperation and coordination, linked to the capability for leadership. If conflict prevention expertise is situated close to senior decision-making levels, it is more likely to become strategic and preventive rather than responsive. The institutions also need platforms to facilitate exchange between different parts of the system. Previous initiatives, such as the Conflict Prevention Group,Footnote4 did not work well enough, perhaps partly because the Group struggled to balance the important and the urgent (Interviews #2, 4), and have not been replaced.

The EU’s preference for multilateralism is well established and an important capability. The greater challenge is internal coordination, and here the EEAS and Commission’s senior management have a pivotal role to play in requiring and supporting different parts of the EU machinery to gather and share expertise and adopt conflict prevention approaches.

Conclusion

The EU uses “conflict prevention” to both (1) a way of acting in the world, which implicates all of the EU’s external action and a significant part of its internal action, and (2) a set of distinct activities, particularly mediation, conflict analysis and early warning. This lack of clarity means that conflict prevention capabilities remain betwixt and between the two different objectives, without meeting either adequately. This is of particular concern given the increased attention to “conflict prevention” internationally, and the need to bridge the gap between early warning and early action.

The two different concepts do not need to pull in different directions. As this article has shown, and demonstrates, conflict prevention as a way of acting in the world may strengthen and be strengthened by conflict prevention as a set of discrete activities. However, this will not happen systemically without recognizing the different capability needs of the two different “conflict prevention” concepts and providing strategic guidance and leadership for how they can reinforce each other.

Leadership is also necessary for prioritizing prevention over response, using the early warning capabilities to identify situations over the horizon and marshalling capabilities for early intervention to prevent conflict, rather prioritizing response to existing crises. A space for the Secretary-General, political directors and geographical managing directors to discuss these types of situation could strengthen leadership and favour early action. A nuanced monitoring system of what works, and what doesn’t, would help move conflict prevention from a matter of faith and enable political leadership.

Conceptual ambiguity notwithstanding, the EU largely has the capabilities to engage, and engage early, even if there is pressure on time and personnel. Some of these, such as delegations, EUSRs and European Parliament election observation missions, could be used to greater effect. Potential funding for long- and short-term conflict prevention is present, as are capabilities for cooperation and coordination, in both the EEAS and DECVO. The main challenge, however, is the necessary political leadership to integrate conflict prevention into strategic decision-making, and to establish priorities, particularly for prevention over response, linking early warning with early action. This would significantly improve the EU’s ability to prevent conflict.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Nabila Habbida and Anna Penfrat for their contributions to an earlier version, and Nabila Habbida, Ana E. Juncos and the anonymous reviewers for their comments on the draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Laura Davis is a scholar and practitioner who has worked extensively in and on peacebuilding and peace-making processes, particularly in sub-Saharan and North Africa, and supported the transitional justice components of peace processes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Libya, Ukraine and Yemen. She also contributed to the development of the EU’s transitional justice policy. She is a senior associate at the European Peacebuilding Liaison Office. She holds an MA (Oxon) in Modern History and a PhD in Political Science from the University of Ghent. Her scholarly articles focus on EU foreign policy, transitional justice, mediation and feminism. Her book EU foreign policy, transitional justice and mediation: principle, policy and practice (Routledge 2014) is the first scholarly treatment of the subject. More information at www.lauradavis.eu

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The EU can, of course, make a situation worse. Albert et al. characterize the EU in some situations as a “perturbator”, a worrying disturbance for the conflict (Citation2008, p. 23).

2 Used here rather than “political will” (see Whitman & Wolff, Citation2012, p. 11) to better reflect that decisions taken (or not) create an environment in which something happens or does not happen.

3 I am grateful to Ana E. Juncos for this point.

4 The Conflict Prevention Group was convened by SECPOL.2 and brought together representatives of the relevant geographical and thematic directorates as well as the crisis management bodies, the chairs of the Committee for Civilian Aspects of Crisis Management (CivCom) and Politico-Military Group (PMG) as well as representatives from the Service for Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI) and DG DEVCO (the Fragility and Crisis Management Unit) to gather and review early warning information, identify early response options, develop conflict risk analysis and mainstream conflict prevention in EU external action.

References

- Albert, M., Diez, T., & Stetter, S. (2008). The transformative power of integration: Conceptualizing border conflicts. In T. Diez, M. Albert, & S. Stetter (Eds.), The European Union and border conflicts: The power of integration and association (pp. 13–33). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bossi, L., Dochartaigh, N. O., & Pisoiu, D. (2015). Political violence in context: Time, space and milieu. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Council of the European Union. (2009). Concept on Strengthening EU Mediation and Dialogue Capacities 17779/09. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Council of the European Union. (2011). Conflict Prevention – Council Conclusions 20 June 2011 Doc. 11820/11. Brussels.

- Davis, L. (2014). EU foreign policy, transitional justice and mediation: Principle, policy and practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Davis, L. (2016). EU options for Sudan. Retrieved from Pax for Peace: https://www.paxforpeace.nl/publications/all-publications/sudan-alert

- Diez, T., Albert, M., & Stetter, S. (2008). The European Union and border conflicts: The power of integration and association. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- EEAS. (2013). Guidance note on the use of conflict analysis in support of EU external action. Retrieved from Europa: https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/guidance-note-use-conflict-analysis-support-eu-external-action_en

- EEAS. (2016). Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace. Retrieved from https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/422/instrument-contributing-stability-and-peace-icsp_en

- EEAS. (2017). A security and defence union in the making: Recent developments and what’s coming up. Retrieved from https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/34278/security-and-defence-union-making-recent-developments-and-whats-coming_en

- EEAS. (2018). Colombia: EU will continue to deliver political and practical support to peace process. Retrieved from https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/38369/colombia-eu-will-continue-deliver-political-and-practical-support-peace-process_en

- EU-CIVCAP. (2016). EU capabilities for conflict prevention and peacebuilding: A capabilities-based assessment. Internal document.

- European Commission. (2001). Communication from the European Commission on Conflict Prevention 11 March 2001 COM (2001) 211 Final. Brussels.

- European Commission. (2011). Thematic evaluation of European Commission support to conflict prevention and peace-building. Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission and High Representative. (2013). The EU’s comprehensive approach to external conflict and crises joint communication to the European Parliament and the Council, JOIN(2013) 30 final (Brussels, 11 December 2013). Brussels: European Commission.

- European Commission and High Representative. (2016). Taking forward the EU’s comprehensive approach to external conflicts and crises – action plan 2016–17 joint staff working document, SWD(2016) 254 final (Brussels, 18 July 2016). Brussels: European Commission.

- European Council. (2001). EU programme for the prevention of violent conflicts adopted by European Council June 2001. Göteborg: European Council.

- European External Action Service (EEAS). (2014). Fact Sheet: EU Conflict Early Warning System. Retrieved from Europa: http://www.eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/cfsp/conflict_prevention/docs/201409_factsheet_conflict_earth_warning_en.pdf

- European Parliament. (2018). Revised EU Approach to Security and Development Funding (Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace). Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-europe-as-a-stronger-global-actor/file-revised-eu-approach-to-security-and-development-funding

- European Peacebuilding Liaison Office. (2014). Briefing paper: EPLO briefing paper, support for peacebuilding and conflict prevention in the EU’s external financing instruments 2014–2020. Brussels: EPLO.

- European Peacebuilding Liaison Office (EPLO). (2016). Report of the CSDN meeting ‘peacebuilding in the EU Global Strategy: Gathering civil society input’. Brussels: EPLO.

- European Union. (2009). Consolidated Treaty on European Union. Official Journal C 83, 30.3.2010, 1–388.

- European Union External Action Service. (2016). Shared vision, common action: A stronger Europe. A global strategy for the European Union’s foreign and security policy. Brussels: EEAS.

- Interview #1. (2016, August 4). Representative of a non-governmental organization. Interview by Laura Davis.

- Interview #2. (2016, August 10). EEAS official. Interview by Laura Davis.

- Interview #3. (2016, August 23). Staff member, Member State Permanent Representation. Interview by Laura Davis.

- Interview #4. (2016, September 16). Official from DG NEAR. Interview by Laura Davis.

- Juncos, A. E. (2016). Resilience as the new EU foreign policy paradigm: A pragmatist turn? European Security. doi: 10.1080/09662839.2016.1247809

- Juncos, A. E., & Blockmans, S. (2018). The EU’s role in conflict prevention and peacebuilding: Four key challenges. Global Affairs. doi:10.1080/23340460.2018.1502619

- Manners, I. (2002). Normative power Europe: A contradiction in terms? Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(2), 235–258.

- Noutcheva, G. (2009). Fake, partial and imposed compliance: The limits of the EU’s normative power in the western Balkans. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(7), 1065–1084.

- Noutcheva, G. (2016, May 2). What the ENP review did not say. Retrieved from Antero EU Foreign Policy Education and Research: http://www.eufp.eu/what-enp-review-did-not-say-g-noutcheva

- Oxfam. (2015, November). Oxfam, “Oxfam Position Paper for the EU-Africa Summit on Migration”, La Valletta, 11–12 November 2015. Retrieved from Oxfam https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/file_attachments/oxfam_position_paper_for_eu-africa_migration_summit.pdf

- Smith, K. E. (2010). The European Union in the world: Future research agendas. In M. Egan, N. Nugent, & W. E. Paterson (Eds.), Research agendas in EU studies: Stalking the elephant (pp. 329–354). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- UN & World Bank Group. (2018). Pathways for Peace. www.pathwaysforpeace.org.

- Whitman, R. (2011). Normative power Europe: Empirical and theoretical perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Whitman, R. G., & Wolff, S. (2012). The European Union as a global conflict manager. London: Routledge.