ABSTRACT

This article studies the securitization of immigration in the United States of America (U.S.), through the analysis of the National Security Strategies (NSS) published between 2002 and 2017, using a two-layered analytical framework that combines securitization theory and agenda setting theory. A discursive analysis of each NSS documents shed some light on how immigration and immigration-related issues emerged, were removed or were prioritized in the security agenda, and how they were framed (or not) as threats. Different contexts in which these documents were published were also taken into consideration, including major crisis or “shocks,” as well as political or institutional changes. The article also considered shifts in the conception of American identity, and the prevailing public opinion on immigration. The main findings demonstrate that the securitization of immigration should be understood as a dynamic process that depends on a variety of factors that change over time.

Introduction

Immigration and security policies are closely intertwined. The migration-security nexus remains constant in the political debate, media coverage and public opinion. Although the securitization of immigration is not a new phenomenon, current forms of the debate and their implications for public policy and international politics require continuous research and critical review.

One of the many levels in which this relationship can be analysed is the extent to which immigrants are identified as an alleged threat to the well-being of the nation in official national security documents put forward by governments or executive policy-making bodies. A case in point is the United States (U.S.) where references to immigrants and immigration-related matters appear in the context of the National Security Strategy (NSS). The framing of immigration-related themes in the periodically updated NSS documents offer thus an important glimpse into one aspect of public, presidential securitisation of immigration worth exploring.

The enunciation of threats and priorities in the NSS can have further implications for wider political debates and the development or modification of security and foreign policies more broadly. Additionally, the NSS is an official document presidents are mandated by law to present to Congress, which ultimately plays an important role in defining public policies, allocating budget and enacting legal reform. The NSS, thus, is not only a list of perceived threats, but also a starting point for wider discussions related to the policy agenda and the relations between the executive and legislative branches of government, who seek to address and shape them.

A comparative study of the incorporation and exclusion of immigration in the U.S. NSS as an agenda setting mechanism since 9/11 has not been produced so far. To address this gap, this article aims to answer the following research question: to what extent have immigrants been securitized in the U.S. at the presidential strategic level in the context of five National Security Strategies between 2002 and 2017 and how can this process be understood?

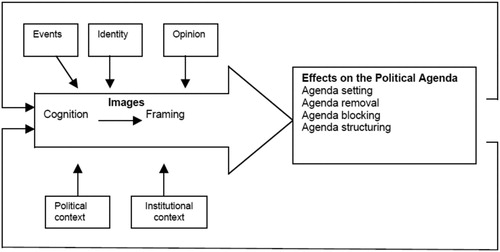

To answer these questions, the article relies on an analytical framework that combines securitization theory and agenda setting theory, through the application of the explanatory model developed by Eriksson and Noreen (Citation2006), which considers two layers of analysis to establish how issues are securitized and how external factors condition this process. While it has much to offer as an analytical tool for studying a variety of security agendas, the model has also been largely neglected in academic research so far.

The U.S. is used as a case study by exploring the incorporation, removal or prioritization of immigration and immigration-related issues in the five NSS published between 2002 and 2017. Focusing on this specific strategic document offers a reference point for a longer-term comparative analysis. The main goal is to uncover the process that leads from a total absence of references to immigration in the first NSS published after 9/11 to a strong focus on the alleged threats posed by immigrants 15 years later. Utilizing Eriksson and Noreen’s (Citation2006) model as an innovative approach, a secondary goal is to determine how this securitization process functions as part of an agenda setting mechanism. It must be underlined, however, that the article does not focus on outcomes or successful policy changes, but solely on the NSS as a starting step to potentially influence changes, highlighting the leading role of presidential personal conceptions and preferences.

The article is structured as follows. The first section presents a brief overview of how immigration and national security have been linked together in the U.S. and the implications of establishing this nexus at the level of the NSS. Next, the theoretical framework is presented by explaining the main components of securitization theory and agenda setting theory as the two levels of analysis used in the article and which serve as the basis for Eriksson and Noreen’s (Citation2006) model. Third, a section on case selection and methodology explains how the analytical framework was applied to study how immigration is portrayed in the NSS published in the U.S. between 2002 and 2017. The four following sections present the main part of the analysis, focusing on each component of the model as they apply to each NSS. The final section contains the main findings of the analysis, which underline that there effectively was an increasing securitization of immigration in the NSS over a 15-year period that can be explained by different factors of which the personal views of each president and the context in which they served turned out to be the most important factors.

Research on the securitization of immigration

The study of the securitization of immigration lies at the intersection of different academic and policy fields analyzing the interconnection between migrants and states, such as international relations, foreign policy, immigration policy, national security, border control, economic development, and human rights, to name some. In each subfield, debates focus on the positive and negative effects of the securitization of immigrants.

In the U.S., historically, there have been swings between welcoming and restrictionist approaches in migration policy based on security concerns. The American political debate on national security changed significantly after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. For many scholars, these attacks mark a watershed in U.S. policy towards national security, immigration and border control. For instance, Critelli argues that they created “a new world order” (Citation2008, p. 142); for Adamson, they signal the beginning of migration being handled as a “top national security” issue (Citation2006, p. 165); and Woods and Arthur state that they “marked a turning point in immigration policy discussions” (Citation2017, p. 27).

Other scholars stress a continuum of tougher immigration controls and enforcement since the decade of 1990 predating the ‘9/11 effect’. Délano and Serrano underline the addition of an antiterrorist component to the two decades-old coupling of immigration and border security to combat drug trafficking (Citation2010, p. 486). Similarly, Friman argues that it is best to understand the securitization of immigration in the aftermath of the attacks as an “outgrowth of earlier politics, policy and practice” (Citation2008, p. 130). For both sides, however, 9/11 has become a (nearly) sine qua non referent point for analyzing the immigration-security nexus in the U.S. Therefore, 9/11 also marks an important point of influence and of departure for its effect on high-level public strategic documents, such as the NSS.

A national security strategy is a “plan for the coordinated use of all the instruments of state power – non-military as well as military – to pursue objectives that defend and advance the national interest” (Dupuy cited Doyle, Citation2007, p. 624). Stolberg (Citation2012) underlines the official and public nature of these documents and how they can serve many purposes, including creating internal consensus, presenting to legislative bodies the resources requirements, and functioning as communication tools for domestic and external audiences. In the U.S., the Executive Branch is mandated by Section 603 of the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 to produce the NSS on a yearly basis, although the practice has been to publish it once at the beginning of each presidential term. While there is debate about the actual utility of the NSS (Feaver, Citation2010; Walt, Citation2009), it is a fundamental policy document to delineate an Administration’s worldview, interests, values and the challenges it foresees to attain its objectives (Feaver, Citation2017a).

The NSS constitutes the “only complete whole-of-government national security document that the U.S. Government publishes” and serves as an umbrella for other lower level policy documents (Stolberg, Citation2012, pp. 71–73). In this sense, it can be seen as a mechanism for negotiations with Congress towards policy design, legislative reform, and budget allocation. Therefore, it is a starting point of an agenda setting process vis-à-vis Congress and also an important document for internal and external agenda-setting.Footnote1

While it has been argued that the presidential role on agenda setting in the field of national security is merely reactionary and highly conditioned by the media or public opinion, Peake (Citation2001) contends that the salience of an issue is the key factor to evaluate, arguing that the influence of the president increases when dealing with lower profile issues. The prioritization given to immigration vis-à-vis other components of the agenda, such as terrorism and the financial system, changes from one NSS to another and can therefore constitute a signal of how large the president’s power is to influence immigration policy as a matter of national security.

Notwithstanding the above, this is still conditioned by the Constitutional powers bestowed on the U.S. Congress. As Serafino and Ekmektsioglou (Citation2018) explain, the distribution of functions and responsibilities between these two branches of government in matters concerning national security is one of “shared power”. Within this dynamic, their interactions are conditioned by factors such as party politics and polarization, putting forward the politically negotiated nature of the national security agenda.

While the majority of the NSS published since 1986 have included some references to immigration, there is not a consistent pattern, as shown in below.

Table 1. U.S. NSS 1987-2000 – Immigration and security nexusTable Footnotea.

Building a two-layered framework for analysis

In their seminal work Security. A New Framework for Analysis, Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde (Citation1998) highlight the socially-constructed character of security. They define security as “the move that takes politics beyond the established rules of the game and frames the issue either as a sceptical kind of politics or as above politics” (Buzan et al., Citation1998, p. 23). They establish a continuum with non-politicized issues on one side, politicized issues in the middle and securitized issues at the other end. Moving a topic to the securitization end takes it out of normal politics by framing it as an existential threat whose unattendance would make anything else irrelevant (Buzan et al., Citation1998).

This move is not accidental. One of the so-called “Copenhagen School’s” main contributions to the academic debate on security was to underline the political nature of securitization and “create awareness of the (allegedly) arbitrary nature of ‘threats’, to stimulate the thought that the foundation of any national security policy is not given by ‘nature’ but chosen by politicians and decision makers[…]” (Knudsen, Citation2001, p. 359). Security and politics are closely intertwined. Although Buzan et al. categorize security as a “self-referential practice[…] not necessarily because a real existential threat exists but because the issue is presented as such” (Citation1998, p. 24), successful securitization depends on the acceptance of such act by an audience, making intersubjectivity (against mere subjectivity) security’s defining characteristic (Buzan et al., Citation1998).

While securitization theory has become an established and popular approach in the field of security studies and international security (Huysmans, Citation2011; Wæver, Citation2015), there has also been considerable academic debate on its basic precepts. A review of some critics of the Copenhagen School allows expanding and clarifying some of its core concepts. For the purposes of this article, Balzacq’s (Citation2005) contributions on the role of the audience(s), power relations and context will be further examined.

The first argument is that among multiple audiences there is an “enabling audience” (Balzacq, Léonard, & Ruzicka, Citation2016, p. 500) that ultimately needs to be convinced and can provide moral and/or institutional support for the securitizing actor to take exceptional actions. This becomes crucial if a Parliament or Congress needs to approve a specific mandate or policy measures (Balzacq, Citation2005). Secondly, further consideration needs to be given to power relations between securitizing actors and audiences. Although a securitizing actor (traditionally government officials) may be in a power position to do security, the validity of her statements may be conditioned by external and contextual factors. Regarding context, Balzacq et al. claim that it has an independent status in an indirect relationship with power (Citation2016): the more the context presents clues of the existence of a threat, the less the securitizing actor has to hold a powerful position and strong linguistic competences to convince an audience (Balzacq, Citation2005).

Based on this, the study of securitization needs to go beyond a unique utterance and be regarded as a process. Since a securitizing move is an attempt to change the course of the political debate, the analysis also needs to incorporate the developments through which a particular (security) issue comes to be considered and introduced into a (security) policy agenda. In the field of public policy, this process is called policy agenda setting.

A political agenda is defined as “the set of issues that are subject of decision making and debate within a given political system at any one time” (Baumgartner, Citation2015, p. 362). Agenda setting analysis has focused on the processes and factors enabling or disabling the incorporation of certain issues in policy agendas. The academic literature usually highlights Bachrach and Baratz’s (Citation1962) introduction of the concept of “nondecision-making” to signal the relevance of studying not only how policies are initiated, decided and/or vetoed, but also processes and power relations that “limit the scope of actual decision making to ‘safe’ issues” (Bachrach & Baratz, Citation1962, p. 952). The second face of power is the ability to decide which issues do not make it into the agenda in order to preserve the status quo.

Another relevant development was Kingdon’s three streams and opportunity windows (Citation2011). According to him, public policy making follows this process: “(1) the setting of the agenda, (2) the specification of alternatives, (3) an authoritative choice among those alternatives, as in a legislative vote or a presidential decision, and (4) the implementation of the decision”. (Citation2011, pp. 2–3). His model focuses on the first and second stages to understand how problems become issues within a particular policy agenda.

Finally, an additional greatly cited model is the one developed by Baumgartner and Jones (Citation2009). Their argument is that “attention and public policy are characterised by long periods of stability and short periods of dramatic change” (Green-Pedersen, Citation2015, p. 359) making it necessary to analyse long periods of time to identify those changes and the factors that led to them. This is what the authors named the analysis of “policy dynamics” (Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen, & Jones, Citation2006, p. 963).

The basic notion underlying agenda setting theory is that attention is a scarce resource in public policy and only a handful of issues can gather enough interest from policy makers. The study of agenda setting involves analyzing the context and political environment; the characteristics of the political system and the dynamic among branches of government; as well as power structures, personal preferences and particular interests of key actors that can influence the agenda.

Combining agenda setting theory and securitization theory results in a stronger analytical framework to study national security strategies, which is the starting point for Eriksson and Noreen’s model (Citation2006). This explanatory model was developed as part of a research project on “Threat Politics” between 2000 and 2007 in the Department of Peace and Research Conflict at the University of Uppsala in Sweden. Their main goal was to explain “why certain threat images appear on the political agenda and others do not” (Eriksson & Noreen, Citationn.d.). The model has four main advantages: (1) the acknowledgement of security as an “exceptionally loaded” political concept (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 11); (2) the incorporation of a multi-causal explanation which includes actor-related and structural factors (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 20); (3) the applicability of the model to analyse the removal of a particular issue from the agenda or the conditions limiting its inclusion (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 20; and 4) the flexibility to apply the model as a whole or partially, depending on the case study (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 7).

In order to analyse how issues appear, are removed, are prevented from appearing or are prioritized in the security agenda, the authors propose a multi-factorial analysis with two necessary (although not sufficient) factors and five context/case-dependent factors. The first two must always be included in the analysis, while the other five may or may not.

Necessary factors:

Cognition: refers to the perception involved in the framing of threats at the individual level, based on the inclination to avoid risks and protect core values. It relates to the subjective nature of threats signalled by the securitization theory (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, pp. 8–10).

Framing: similar to the speech-act of the securitization theory, it refers to “the rhetorical art of[…] depicting and representing an issue[…] in such a way that others listen and are convinced or are at least persuaded to pay attention [to it]” (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 10).

Contextual factors:

Events: they can affect the perception of threats and security, particularly those extremely dramatic that are viewed as crises or external shocks (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, pp. 12–13).

Identity: a “fundamental societal value” that can affect how threats are perceived. Identity is as essential for a society as sovereignty is for a state; perceived threats to it are taken seriously (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, pp. 13–15).

Political context: defined as “the conditions required to win or to persuade decision-makers with power-based arguments[… including] majority position in legislative assemblies, alliances and coalitions, negotiations, and the preferences and ideologies of leading decision makers” (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 15).

Institutional context: refers to “persuasion based on knowledge arguments” which are also embedded in norms and bureaucratic procedures of the organizational culture of the political system (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, pp. 16–17).

Opinion: refers to the role of public opinion in shaping the perception of threats and policy options (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 18).

The first two and necessary factors heavily incorporate the precepts of securitization theory. The remaining factors recognize the relevance of context, as claimed by post-Copenhagen scholars, to determine why issues are perceived as threatening and enter or leave security agendas based on the scarcity of attention put forward by agenda setting theory. The combination of these two theories allows studying, on the one hand, how immigration has been securitized in the U.S. at the presidential discursive level and, on the other hand, how this process leads to the incorporation, prioritization or removal of immigration as a threat in the NSS. For the purposes of this article, the underlying factor connecting both theories together is the political and intersubjective nature of this process, positioning the Executive as the securitizing actor and the Congress as the enabling audience that is needed to legitimize the securitizing move and provide institutional support and policy change, within a specific context. The NSS is therefore a securitizing move and an agenda setting mechanism from the Executive Branch, seeking to convince Congress and the American public of the existential nature of threats and the need for extraordinary measures. ().

Figure 1. Security agenda setting model. Source: Obtained from (Eriksson & Noreen, Citation2006, p. 19).

Case selection and methodology

The NSS is an official and public document the Executive Branch is mandated by law to present to Congress and therefore can be seen as an important element of the “official [security] agenda” that Eriksson and Noreen (Citation2006, p. 3) suggest using for this type of analysis. During the time frame considered in this article there were five NSS published: those authored by George W. Bush in 2002 and 2006; by Barack Obama in 2010 and 2015; and by Donald Trump in 2017. These five documents provide examples of agenda removal, (re)appearance and prioritization in a post-9/11 attacks context – considered as an inflection point in the American security agenda with large effects on immigration. There is an incremental consideration of immigration as a security concern in the NSS between 2002 and 2017, allowing for a longer-term analysis of securitization and agenda setting processes.

The framing factor was studied through a discursive analysis of the five NSS. When applied to the field of the study of securitization processes, discourse analysis is still the preponderant choice to analyze the shaping of threats through a specific language. The results were quantitatively and qualitatively coded in terms of how many times immigration or immigration-related issues were mentioned, whether they directly or indirectly related to security, and whether this was done in mainly positive or negative terms. The resulting coding document is presented in Appendix I.

The cognition factor was studied through the analysis of key speeches and declarations on immigration by the three presidents and their administrations, as a means to uncover personal preferences towards immigration and how these shape security preferences. The documents included constitute a representative sample, enough to illustrate how the personal background, values and preconceptions affect each of the presidents’ views on immigration.

The contextual factors were analysed for each administration considering major events, crisis or external shocks, the relation between branches of governments and institutional changes resulting from legal reform or executive directives. The question of identity focused on the American values highlighted in each NSS and the self-image of the U.S. projected for domestic and external purposes. Finally, the element of (public) opinion was also explored below through a review of public opinion polls that surveyed public perceptions of immigrants in relation to national security and the “preservation of the American way of life”. This aspect of the theoretical framework was mainly done by utilizing Gallup’s Most Important Problem survey, which asks samples of Americans what he or she perceives to be the most important problem the country is facing on a monthly basis. Other reports of the main polling agency were utilized to analyse public opinion regarding other matters, as they constitute diachronic surveys that repeat the same question over long periods of time.

It must be noted that the relationship between the media, public opinion and the perception of threats, particularly related to such a contested field as immigration, presents complexities that go beyond the scope of this article, but have been explored elsewhere (see for example Haynes, Merolla, & Ramakrishnan, Citation2016). The analysis of the factor of public opinon was nevertheless included in this article’s analysis as an ancillary aspect, as it forms a component of Eriksson and Noreen’s (Citation2006) model that could not be neglected; however, there are more detailed studies that help explain this relationship, both for national security matters, in general, and the security-immigration nexus, in particular.Footnote2

The following sections will present the results of the analysis. A brief introduction of the contexts of each of the three administrations, explaining how they came to power and what their initial priorities were, will be followed by a comparative discussion based on the factors outlined by Eriksson and Noreen’s model. Cognition and framing will be jointly considered to explore each president’s views on immigration and how they translate into the NSS. Events, political context and institutional context will be grouped to examine the contextual environment in which the documents were produced. Finally, identity and opinion will be individually examined for each Administration. The comparative analysis will allow to determine which factor(s) had greater preponderance towards the removal, reappearance and prioritisation of immigration in the national security agenda of the U.S. between 2002 and 2017.

Three presidents and five NSS

George W. Bush came to power after an extremely contested election. Having lost the popular vote and amid a recount process in Florida, he won the presidency after a “highly controversial 5–4 Supreme Court decision in his favour” (Gregg II & Rozell, Citation2003, p. 133). The terrorist attacks of 9/11, 2001, provided him the “opportunity to galvanize a divided nation[… giving] him a purpose, identity, legitimacy and in time legacy” (Wong, Citation2006, p. 114). His presidency ended up being a wartime one, conditioning domestic and foreign policy in many ways.

During his tenure, two NSS were published in 2002 and 2006. The War on Terror and the export of American values laid the foundation for both documents. The president’s opening letter in the 2006 NSS states it bluntly: “America is at war. This is a wartime national security strategy” (§1). As such, the 2002 and 2006 NSS focus extensively on the characteristics of the international system, the main threats posed by traditional and non-traditional actors, and the role of the U.S. as a leader towards a freer, fairer, more democratic world. There is no direct mention of immigration in the 2002 NSS, and only one tangential reference in the 2006 NSS. Considering immigration had been consistently included in all of Bill Clinton’s NSS from 1994 to 2000, the exclusion made by the Bush Administration is a case of removal of an issue from a security agenda.

In contrast to Bush, Barack Obama came to office in January 2009 after a landslide victory in the 2008 elections.Footnote3 The stagnation of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the severe economic recession that erupted in 2008 helped his election and the popular demand for a new kind of leadership.Footnote4 Likewise, Democrats won significant majorities in both chambers of Congress, also underlining Obama’s presidency as a “new beginning” (Hulse, Citation2009). The honeymoon, however, would be over after the midterm elections in 2010, when Democrats lost the majority at the Senate, and in later elections after Republicans regained dominance in both chambers. The remainder of Obama’s tenure was marked by confrontation with Congress and an increasing partisan divide.

In his inaugural address, Obama stated that the nation was “in the midst of a crisis” that demanded to “begin again the work of remaking America” (Phillips, Citation2009, §5 and 12). This quest for renewal became the foundation of both NSS published during his tenure in 2010 and 2015. While there is some continuity from Bush’s to Obama’s NSS in terms of American values and interests, one of the principal differences is the reintroduction of immigration as a security issue. This is mainly evident in the 2010 NSS, where immigration and immigration-related issues are referenced several times.Footnote5 Although the matter is much diminished in the NSS of 2015, it is still present as a security priority. According to Eriksson and Noreen’s model, then, the 2010 and 2015 NSS are cases of appearance and (de)prioritization, respectively. In both documents, immigration is framed as a positive trait of American society, but strongly associated with border security and the rule of law.

Finally, the results of the November 8, 2016 election came as a surprise to many.Footnote6 Trump was an “unorthodox” contender and not even the traditional leadership of the Republican party was convinced of his candidacy (Jacobson, Citation2018, p. 404). Promising to “make America great again”, he presented himself as “anti-Obama, anti-immigrant, anti-Mexican, anti-Muslim, and anti-globalization” (Jacobson, Citation2018, p. 403). He took office on January 20, 2017, claiming that that day would be remembered as the one on which power was given back to the American people (Trump, Citation2017a, §6 and 17).

The Trump Administration published its first NSS in December, 2017, proclaiming the objective of putting “America first” (Trump, Citation2017c, §18). Immigration appears prominently in the document, whose first chapter is heavily focused on homeland security and the threats posed by immigrants (documented and undocumented) in various ways. In later chapters, immigration-related issues also appear linked to other elements of national security. In this sense, the 2017 NSS is a case of prioritization of immigration in the security agenda of the U.S.

Cognition and framing

The Bush Administration appointed former diplomat and foreign policy expert Philip Zelikow to draft the 2002 NSS, while commissioning the 2006 NSS to scholars Peter Feaver and William Inboden. Although both strategies were crafted under the supervision of the National Security Advisors, Condoleezza Rice and Stephen Hadley, respectively, President Bush got closely involved seeking to imprint his personal vision.Footnote7

Former governor of Texas, Bush was no stranger to the immigration phenomenon.Footnote8 After taking office in 2001, his first international state visit was to Mexico, where he met with former president Vicente Fox. Both officials announced a new era for the bilateral relation, prioritizing immigration reform and a temporary-worker programme (Office of the Press Secretary, Citation2001). The terrorist attacks shifted priorities, but a comprehensive immigration reform would remain on Bush’s political agenda. While he never advocated for an amnesty, he recognized and underlined the various contributions of immigrants to American society.Footnote9 Hence, immigration was a matter of law enforcement and border security, but also an issue closely related to economic development and employment. It was not a matter of national security to be prioritized at the level of the NSS.

The 2002 NSS, though not directly mentioning immigrants, recognises that “a diverse, modern society has inherent, ambitious, entrepreneurial energy” (p.31). In the 2006 NSS, “illegal immigration” is only mentioned once as an area in which the U.S. “must continue to work with [their] neighbours in the [Western] Hemisphere” (p.37), later acknowledging the need to promote that “foreign students and scholars study in the United States” (p.45)Footnote10 as a means of strengthening public diplomacy. The few, tangential references to immigration-related issues in both documents are made in positive terms or as areas of opportunity.

Somehow differently, president Obama’s personal views on immigration were more of a mixed nature. While he often recognized the contributions of immigrants to American society and underlined that the majority of the 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. should not be labelled as criminals, he usually mentioned his Administration’s actions to increase border security when talking about immigration reform. This duality and close linkage between immigration and security became a leitmotif incorporated in the NSS.

The two NSS published during Obama’s tenure were internally drafted by staff of the White House, under the supervision of the National Security Advisors, James Jones and Susan Rice, in 2010 and 2015, respectively. The president “felt strongly that domestic homeland security and external national security policy and strategy must all be viewed as part of the nation’s national security efforts” (Stolberg, Citation2012, p. 94). Therefore, domestic issues played a major role in comparison with previous strategies.

In the 2010 NSS “diversity and diaspora populations” (Obama, Citation2010, p. 12) are referenced as part of the unique strengths of the country, claiming that they should not be “a source of divide or insecurity” (Obama, Citation2010, p. 19). Nonetheless, in the third chapter “Advancing our interests”, immigration reform is mentioned as a national security matter. The positive tone that characterized previous references is overshadowed by a securitizing discourse:

[E]ffective border security and immigration enforcement must keep the country safe and deter unlawful entry … Ultimately, our national security depends on striking a balance between security and openness. To advance this goal, we must pursue comprehensive immigration reform that effectively secures our borders, while repairing a broken system that fails to serve the needs of our nation. (Obama, Citation2010, p. 30, emphasis added)

Immigration is significantly diminished in the 2015 NSS. Obama’s cover letter emphasises how “immigrants renew [the] country with their energy and entrepreneurial talents” (Obama, Citation2015, p. 15), while the section pertaining to prosperity states that “immigration reform that combines smart and effective enforcement of the law with a pathway to citizenship for those who earn it remains an imperative” (Obama, Citation2015, p. 15). There are no more details regarding the connection with national security, as the reform appears in a paragraph about the American economy. The only significant addition comes at the end of the document, where the surge of unaccompanied minors at the southern border is identified as “a consequence of weak institutions and violence” in Central America (Obama, Citation2015, p. 28).

The sharp difference in the treatment of immigration between 2010 and 2015 can be explained by events that hindered the president’s political leverage. Immigration continued to be in Obama’s interest but lost salience after the failure to pass immigration reform in 2013 and the judicial struggle regarding the programmes of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA). An analysis of Obama’s messages in the State of the Union and other immigration-related remarks evidences increasing frustration with Congress and a later resignation to stop insisting on something that was not bound to happen.

Marking a stark contrast with these two presidents, Donald Trump launched his campaign claiming that Mexican immigrants were bringing drugs and crime to the U.S., while also accusing them of being rapists (TIME, Citation2015, §9). His first months in office were marked by the intention to transform immigration policy by an extensive use of executive powers (Pierce & Selee, Citation2017). The Muslim Ban, the cuts to the number of refugees allowed per fiscal year, and the rescission of DACA are only some examples. The underlying justifications of these actions were related to national security, as well as economic stability, protection of American jobs and sustainability of the welfare system.

The 2017 NSS was drafted by security expert Nadia Schadlow in collaboration with National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster and Deputy National Security Advisor Dina Powell (Boot, Citation2017; Swan, Citation2017). According to Schadlow’s declarations, the NSS had a lot of input from Trump himself (Gazis, Citation2018). It is based on four pillars, the first of which is “Protecting the American people, the homeland, and the American way of life”, where most references to immigration are found. The text bluntly states that “[r]eestablishing lawful control of [their] borders is the first step toward protecting the American homeland and strengthening American sovereignty” (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 7). In sharp contrast to its predecessors, it does not recognize the contributions made by immigrants, but simply “understands” them, claiming that immigration is a “burden” for the economy, “hurts” American workers and “presents risks” for public safety (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 9, emphasis added).

Trump’s stance on immigration has been noted for its opposition even to legal immigration (Pierce & Selee, Citation2017), which is made evident in the NSS by stating that “decisions about who to legally admit for residency, citizenship or otherwise are among the most important a country has to make” (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 9, emphasis added). The point is taken even further in the second pillar pertaining to “American prosperity”, where the document states the need to tighten visa procedures and limit foreign STEM students “to reduce economic theft by non-traditional intelligence collectors” (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 22). This concern is more deeply advanced in the third pillar, “Preserve peace through strength”, by claiming that “[p]art of China’s military modernization and economic expansion is due to its access to the U.S. innovation economy, including America’s world-class universities” (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 25, emphasis added).

The depiction of immigration in almost exclusively negative terms is a novelty when compared to Bush’s and Obama’s NSS. Feaver (Citation2017b) contends that the language used is “less harsh” than during the campaign but “it is not the pro-immigrant message the last three presidents would have offered”. For Trump, immigration is a national security priority at the highest strategic level. The intended result, it could be argued, is to have more elements to demand Congress greater resources for enforcement and, particularly, the construction of the wall in the southern border.

Events, political context and institutional context

Of the three presidencies analysed here, the Bush Administration was the one which faced the most fundamentally impactful event or “shock” in terms of Eriksson and Noreen’s model (Citation2006). The 9/11 attacks marked an inflection point in American security policy. Bush and his team sought a historical parallel to outline their response to the new threat posed by terrorism and justify the war against it (Feaver & Inboden, Citation2016). Such analogy was found in the Cold War, as a long-lasting struggle confronting opposing views of the world. The parallelism is put forward in the 2002 and 2006 NSS through the juxtaposition of freedom against terror (Bush, Citation2002, §11) and democracy against tyranny (Bush, Citation2006b, pp. 3–6). Leaving an issue like immigration outside, already being discussed with Congress on a parallel track, makes sense within this perspective.

The exclusion of immigration does not mean that it was not a sensitive issue and a policy area extensively modified. At the institutional level, the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the major overhaul in the Executive Branch in 50 years (Woods & Arthur, Citation2017), put immigration control under a homeland security-oriented agency. This merger of two otherwise different policy objectives is best exemplified by Attorney General John Ashcroft, a strong supporter of increased immigration control, when he sentenced: “Let the terrorists among us be warned: If you overstay your visa – even by one day – we will arrest you” (Citation2001).

At the political level, comprehensive immigration reform remained as one of Bush’s political priorities, championed in both of his presidential campaigns in 2000 and 2004 (Gutiérrez, Citation2007). Although the terrorist attacks debunked immigration from the legislative agenda during his first term, in 2004 Bush announced his intention to work with Congress towards immigration reform. There were several bills put forward by bipartisan groups at both houses, but none of them gathered enough support. The debate was heated well beyond Congress and reaching the public. The treatment of immigration at the level of the NSS would not have helped the president’s agenda regarding what, in a pre-9/11 era, had been a priority.

Although not as fundamental as 9/11 and with as deep implications for national security, Obama also faced significant events that shaped his presidency. First, he came to power amid a global economic crisis that threatened to reach a magnitude similar to the Great Depression (Skocpol & Jacobs, Citation2012), thus dedicating his first two years in office to working on the recovery of the American economy. Second, the surge of unaccompanied minors at the southern border during the summer of 2014 directly impacted the immigration-security nexus. Third, there was a rapidly changing international environment with new threats and conflicts, such as the crisis in Syria, Russia’s belligerent behaviour, the rise of ISIS and the outbreak of Ebola. All of these issues were included in the 2015 NSS, which was criticized precisely for its overly broad conception of security.Footnote11 On the domestic front, a confrontational relation with Congress pushed Obama towards what has been termed the “administrative” (Rudalevige, Citation2016) or “unitary” (Barilleaux & Maxwell, Citation2017) presidency through an increasing utilization of executive actions to overcome congressional deadlocks. This was particularly evident in the immigration agenda.

Though the 2010 NSS depicted immigration reform as a national security matter, it did not receive attention in Congress until 2013, nonetheless failing to pass.Footnote12 In the meantime, a piecemeal legislation mostly concerned with young immigrants known as “Dreamers” also failed to gain enough support.Footnote13 As a result of what Obama signalled as “the absence of any immigration action from Congress” (Office of the Press Secretary, Citation2012), the Administration created the DACA programme in 2012 and attempted to follow suit in 2014 with DAPA, although the later stalled in a legal battle. The opposition faced by the Administration and their defeat in the judicial front also explains why immigration was severely reduced in the 2015 NSS. These developments can also be understood in the context of the confrontation between Obama and Congress. Paradoxically, the 2015 NSS makes several references to congressional sequestration as an obstacle to advance U.S. security.Footnote14

Unlike his predecessors, by the time Trump published his NSS he had not faced internal crises or “external shocks” that could be utilized for shaping his security agenda (Feaver, Citation2017b). Immigration-wise, there is evidence that the number of people unlawfully present in the U.S., as well as new arrivals, was at the lowest levels for a decade. Furthermore, a report by the Pew Research Center found that undocumented immigrants arriving from Mexico had significantly decreased from 52% of total arrivals in 2007 to 24% in 2016 (Passel & Cohn, Citation2018, p. 10). It is true that there was already an increase in arrivals from countries of the Northern Triangle in Central America (El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras), but the surge of people from these countries travelling in caravans would not erupt until October, 2018 (Lind, Citation2018; WOLA, Citation2018). Somehow paradoxically, the only event significantly affecting the discussion on immigration was Trump’s victory in the presidential elections itself.

Trump’s arrival at the White House “dramatically changed the conversation around immigration” (Pierce & Selee, Citation2017, p. 2). These changes developed amid turbulences and what Fullerton called a “clash between branches of government” (Citation2017, p. 327). Within the Executive Branch, the new Administration faced serious difficulties to ensemble the team in charge of the national security policy. Between January, 2017 and March, 2018, two National Security Advisors, Michael Flynn and H.R. McMaster, had resigned already. These continuous changes in such a sensitive policy realm attest to internal turmoil and disagreements with the president that ultimately impact a coherent evaluation and implementation of the national security policy.

Trump and his Administration faced several battles in the courts. His executive orders on the Muslim ban, refugees’ caps, and DACA, for example, were brought before the judicial system on grounds of their contested constitutionality (Fullerton, Citation2017; Pierce & Selee, Citation2017). The situation with Congress was not better. Although Republicans conquered majorities at both chambers in 2016 elections (Ballotpedia, Citation2016), there still were disagreements with the president over immigration policy. Trump’s insistence on the threatening nature of immigrants of all sorts responds to Congress’s refusal to appropriate the resources to build his long-promised wall and, as previous administrations, to have immigration reform passed, although this time favouring the enforcement and curtailment side. Disagreement over these issues ultimately led to the longest government shutdown at the end of 2018 (Restuccia, Everett, & Caygle, Citation2019), demonstrating Trump’s failure to bring Congress on board of his securitizing agenda. The battlefield did not seem to improve after the Democrats regained a majority at the House in the 2018 midterms (Ballotpedia, Citation2018).

According to Eriksson and Noreen’s model (Citation2006), external shocks or crisis events had a greater role in shaping national security priorities during Bush’s and Obama’s administrations and a much lesser one for Trump’s. Although the Executive Branch has significant powers to shape immigration policy and, particularly through executive actions, and widen or limit border control and enforcement, significant policy changes including legal reform necessarily pass through Congress. Therefore, the agendas of all three presidents were fundamentally affected by the composition of Congress, electoral cycles and the overall tone of the relationship between these two branches of government. The political and institutional contexts, then, prove to be of great significance for the analysis and, for these three presidents, fundamental factors to explain how immigration was treated at the NSS level.

Identity

A document like the NSS helps to understand the discursive nod to various national self-conceptions. It is in this aspect, perhaps, that the NSS published by Bush and Obama mostly differ from the one published by Trump, with significant changes in depicting American values and the U.S. role in the international system. Bush and Obama both underlined human freedom and democracy as core American values that needed to be projected and promoted abroad as a prerequisite for American security. The 2006 NSS, for instance, embraces the theory of democratic peace by contending that “promoting democracy is the most effective long-term measure for strengthening international stability” (p.3). Similarly, Obama’s, Citation2010 NSS states that American security is based on a peaceful and stable international environment, grounded on American values like democracy and human rights.

Another shared characteristic of both presidents’ NSS is the conception of the U.S. as a leader, with slight differences. Although it was more nuanced in the 2006 document, it is important to bear in mind that the 2002 NSS embraced pre-emptive action and even the possibility for the U.S. to act alone to defend their interests. In this sense, the Obama Administration contends that “the question is never whether America should lead, but how we lead” (Citation2015, p. 2, emphasis added). The notion of a renewed leadership for the U.S. first appeared in the 2010 NSS as a prerequisite to advance their interests in the twenty-first century. In an effort to distance himself from Bush’s unilateralism, Obama prioritises the idea of leading through example and promoting American values by living up to them domestically.Footnote15

For both presidents the American identity portrayed through the NSS has a domestic and an external audience. For Bush, the aftershocks of suffering attacks directly on American soil required a unified nation ready to assume the challenges of the new international system and the “war on terrorism” as a response (Leffler, Citation2011). Externally, an “us” versus “them” rhetoric was used to divide other nations as either friends and allies, on one hand, and rogue states, tyrants, terrorist organizations or states harbouring them, on the other. For Obama, the message for the world was that the U.S. would no longer overextend its capacities beyond its most strategic interests (Obama, Citation2010). Domestically, the emphasis on the rule of law and internal “renewal of civility and commitment” (Obama, Citation2010, p. 52) called upon other branches of government to work together towards American interests, regardless of the partisan divides.

Marking a stark contrast, President Trump states in his cover letter that the 2017 NSS is a “National Security Strategy that puts America first” (p.II). This document sees a world marked by competition in the political, economic, and military fields (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 2). Although the fourth pillar of the document, “Advance American influence”, concedes that “a world that supports American interests and reflects [their] values makes America more secure and prosperous”, it adds that they will “compete and lead” to protect their interests and principles (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 4, emphasis added). American leadership is conceived more as a precondition for American gain, than a prerequisite for a peaceful, stable world.

While both Bush and Obama somehow included diversity, multiculturalism and ethnic richness as defining and strengthening traits of the American identity, none of these words appear a single time in Trump’s NSS. As Jacobson explains, it seems as if “make America great again” actually meant “make America white again” (Citation2018, p. 405). Consequently, this document not only modifies the traditional conception of the U.S. as a collaborative leader in a globalised world, but also marks a deep contrast regarding the most basic conception of what defines the American identity.

Opinion

By the time the 2002 NSS was published, terrorism was consistently mentioned as America’s most important problem for around 40% of the population in Gallup’s Most Important Problem monthly survey (Jones, Citation2002). However, Americans did not show that much support for Bush’s unilateralism and pre-emptive action, with 65% claiming that military intervention in Iraq should be conducted in alliance with other nations and with the UN’s approval (Bouton & Page, Citation2002). In 2006, before the publication of Bush’s second NSS, support for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq had severely declined, along with Bush’s ratings (Jacobson, Citation2010), which could explain the shift towards greater multilateralism, the watering down of pre-emption, and the higher significance given to American values.

Gallup’s surveys demonstrate that the percentage of people who considered immigration the most important problem consistently remained below 5% from 2001 until 2006. The survey registered a spike in April, 2006 (19%) due to the salience of discussions on immigration reform (Jones, Citation2019). Based on findings of the same polling agency, in the period 2001–2007, between 52% and 67% of respondents considered immigration a good thing for the country; however, a consistent majority preferred current levels of immigration to be decreased (Jones, Citation2019).

During Obama’s presidency trends are similar: immigration did not rank high unless it had particular salience in the news or the political debate. According to Gallup’s Most Important Problem survey, immigration consistently ranked low, at around 5%, with a spike in 2014 (17%) that correlates to the crisis of unaccompanied minors and the polarization around it (Jones, Citation2019). Meanwhile, economic issues were seen as a priority: in 2009 a striking 89% placed the economy as the main problem for the U.S. This figure decreased as the economy recovered, finishing slightly above 20% at the end of Obama’s Administration. However, economic concerns remained above 50% in average between 2009 and 2016 (Gallup (b)).

Obama’s dual approach to immigration, favouring enforcement and also a path to citizenship somehow reflects public attitudes. It was during Obama’s presidency that the percentage of Americans considering that current levels of immigration should be increased continued to grow, passing for the first time the 20% threshold, while the number of people considering they should be decreased continuously diminished until below 40% (Jones, Citation2019). As another example of this mixed feelings, Jones (Citation2019) stresses that “two-thirds of Americans who identify immigration as the most important problem still believe it is a good thing for the country”.

Again marking a contrast with the two previous administrations, the salience of immigration within the public appears to have increased with Trump’s campaign and arrival into the White House. Gallup’s monthly survey presents an increasing trend fluctuating between 13% and 23% of respondents saying immigration is the main national problem between 2017 and 2019, with a first spike at 22% in July, 2018 during the controversial practise of separating immigrant children from their families at the southern border (Jones, Citation2019).

Nevertheless, when asked about more specific aspects of this phenomenon, Gallup surveys produce mixed results. For example, in June, 2017, respondents were fairly divided when asked if immigration flows should remain at present level (38%), be increased (24%) or be decreased (35%) (Gallup (a)). Overall, and contrary to Trump’s repeated arguments, during his administration a consistent majority considered immigration to be a good thing for the economy, 51% responded that immigration did not have much effect on job opportunities for them or their family, and 72% thought that immigrants were taking jobs Americans did not want (Gallup (a), emphasis added).

The mixed figures for all three presidents demonstrate how controversial immigration is for the American public and how positions shift depending on external factors or its relevance in the political debate. As Dionne explains, “Americans are philosophically pro-immigration, but operationally in favour of a variety of restrictions” (Citation2008, p. 78). This means that immigrants are not necessarily seen as something bad or as an existential threat. The public in general rejects the idea of deporting all undocumented immigrants but still worries about how they might overcharge welfare programmes and public services. In the end, “Americans are deeply practical in their view of immigration” (Dionne, Citation2008, p. 79).

In terms of its relevance shaping the NSS, there seems to be a complex and not straightforward relationship between public opinion and how immigration is framed as a security issue. For Obama and Bush, responses from the public to their policies on immigration seem to help explain certain changes from their first to their second NSS. However, how the issue was originally presented in the first strategy published by each administration appears to be more related to personal views and priorities. This is also true for Trump. It must be borne in mind that immigration got salience in public debate as a result of his campaign’s narrative. Immigration having such a significance in Trump’s 2017 NSS is better explained by his personal views than by those from the public.

Conclusion and main findings

This article studied the securitization of immigration through the prioritization it has received in the NSS of the last three American presidents. Regarding the first part of the research question – to what extent have immigrants been securitized at the strategic level of the NSS in the U.S. – the analysis leads to the conclusion that immigration has been increasingly depicted as a threat to American security at this strategic level. However, more important than the upward trend, the analysis demonstrates that the securitization of immigration has to be understood as a dynamic process conditioned by a variety of factors that change over time. Among these many factors, the priorities and worldview of an Administration, as shaped and conditioned by the president’s background and preferences, play a larger role in the framing of immigration as a security threat in the NSS. This conclusion aligns with previous research establishing a presidential leading role in the design of national security policies and also confirms how the NSS is a tool used by the Executive Branch to make their priorities clear before Congress and set the tone for future negotiations. It is noteworthy that a linkage between immigration and security already appeared during Obama’s tenure in the NSS.

In Security: A New Framework for Analysis, Buzan et al. contend that alongside the securitization of an issue, there also exists the inverse process of desecuritisation, which corresponds to the return to “the normal bargaining process of the political sphere” (Citation1998, p. 4). While these two processes are the extremes of a continuum, reality shows that specific issues often approach one side or another depending on the context and the perceptions of different actors. The changes in the treatment of immigration at the NSS level between 2002 and 2017 evidence this dynamic flow. More than merely stating if immigration is more or less securitized at a specific moment, studying the factors that explain these shifts becomes the more relevant.

This leads to the answer to the second part of the research question – how can this securitization process be understood. This article has argued that the NSS is not only a securitizing move but also a means used by the Executive Branch to set the direction of the American security policy and initiate a dialogue with Congress towards policy change and budget allocation. Based on the theory of agenda setting, the analysis of the NSS allows identifying periods of stability, change and confrontation between branches of government regarding security priorities around immigration policy.

The explanatory model developed by Eriksson and Noreen (Citation2006) is a suitable analytical tool to approach the dynamic nature of security agendas and explore why certain issues are presented as threats and prioritized, while others are minimized or entirely removed. As anticipated by the model, the “necessary factors”, i.e. cognition and framing, are the most relevant to explain the appearance, removal or prioritization of immigration in the NSS of the U.S. in the time frame considered. Personal views on immigration of the studied presidents turned out to be decisive on the importance awarded to it as a security-related issue and the extent to which this security nexus was framed in mainly positive or negative terms. The other five context-related factors (events, political context, institutional context, identity, and opinion) complement the analysis, presenting different combinations that result in dissimilar levels of prioritization.

Bush made virtually no direct connection and tangential references to immigration-related issues were presented in positive terms. In this case, an external shocking event and important changes in the political and institutional context are the main factors explaining the removal of immigration from the security agenda. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 marked a turning point in the U.S. security policy and forced the Administration to focus on the fight against terrorism. While Bush tried to have a comprehensive immigration reform passed, negotiations with Congress were handled at a parallel track, outside the NSS.

Obama made a strong and direct connection, but mainly directed to the need to reform a broken immigration system. The threat is not immigration per se, but the uncontrolled flows resulting from a restrictive system that forces to deviate resources that could be best used in other security priorities. Here, the political context and some external events in a changing international environment were important factors explaining immigration’s (re)appearance in the security agenda. The constraints imposed on the Executive to tackle immigration and push for a comprehensive reform that favoured both enforcement and a path to citizenship hindered Obama’s efforts and explain the deprioritisation of immigration in his second NSS. Additionally, while the economic crisis and the need to recover the American economy played a significant role shaping Obama’s first term, international events demanded greater attention during his second term.

Trump made a direct connection, too, but in mainly negative terms. Not only is undocumented immigration seen as a threat, but so are legal flows related to family reunification and foreign students. In Trump’s case, the political and institutional context explain the prioritization of immigration. Furthermore, a modified conception of the American identity through the “America First” doctrine significantly contributed to the increased salience of immigration as a security concern linked to American sovereignty, economic stability and the sustainability of the welfare system.

The article’s main contributions for academic discussion and future research mainly relate to filling two identified gaps in the study of the immigration-security nexus in the U.S. First, this has not been sufficiently done taking the NSS as stable component of the political agenda, nor have comparative studies been developed focusing on the treatment given to immigration in this policy document. Second, the securitization of an issue has not been sufficiently studied as an agenda setting mechanism in public policy. To fill these gaps, this research was based on a two-layered analytical framework whose main pillars are securitization theory and agenda setting theory, as combined through the explanatory model developed by Eriksson and Noreen (Citation2006) to study security agendas. This framework has the advantage of being clear and flexible enough to be applied to a larger number of policy documents.

Eriksson and Noreen’s model (Citation2006) has not been sufficiently used to develop empirical analysis, although it has proved to be a helpful tool with ample possibilities for further applicability. It is no surprise that there is an uneasy relation between immigration policy and subjective security definitions that change from time to time, from one administration to another. It is revealing, though, the extent to which applying this model helps to uncover how different factors, which had not been put together, shape the process and contribute to understand it as a whole.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (202.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Desirée Colomé-Menéndez

Desirée Colomé-Menéndez is career member of the Mexican Foreign Service since 2015. She is currently posted as Head of Economic Affairs and Trade Promotion at the Mexican Embassy in the Netherlands. From 2015 to 2018 she served as Head of Consular Protection and Legal Affairs at the Mexican Consulate in Kansas City, Missouri. She holds a master degree in Crisis and Security Management from Leiden University.

Joachim A. Koops

Joachim A. Koops is Professor of Security Studies and Scientific Director (WD) of the Institute of Security and Global Affairs (ISGA) at the Campus The Hague at Leiden University. His EU foreign and security policy, UN peacekeeping, NATO crisis management and inter-organizational relations in Global Security Governance.

Daan Weggemans

Daan Weggemans is programme director of the BSc Security Studies and researcher at the Institute for Security and Global Affairs. He conducts research into the deradicalisation and reintegration processes of violent extremists, and new terrorism strategies and technologies.

Notes

1 Paragraph A.2 of the Goldwater-Nichols Act states that the Executive Branch must transmit the NSS “on the date on which the President submits to Congress the budget for the next fiscal year … ” while paragraph B.5 establishes that it should include the information necessary “to help inform Congress on matters relating to the national security strategy of the United States”.

2 There is rich literature and an established research tradition on public opinion attitude towards immigration in the U.S. since at least the 1970s. See, for example: Dunaway, Branton, & Abrajano, Citation2010; Segovia & Defever, Citation2010; Conklin Frederking, Citation2012; and Strauss, Citation2012; Muste, Citation2013.

3 Obama won 53% of the popular vote against 46% that went to the Republican candidate John McCain; in the Electoral College, he won 365 votes while McCain only got 173. (Skocpol & Jacobs, Citation2012, p. 5).

4 Univision anchorman Jorge Ramos said during Inauguration Day that it was “difficult to put into perspective the euphoria that is being caused, in the United States and the rest of the world, by the inauguration of Barack Obama’s presidency. Two things explain it: a terrible global economic crisis and the personality of a man, very young, that assures us that the future will be better”. (Cited Sampaio, Citation2015, p. 130).

5 See Appendix I.

6 News coverage reflected the unexpected nature of the results through titles. See, for example, Denning (Citation2016), Flegenheimer and Barbaro (Citation2016), and Hirschhorn (Citation2016). According to a Gallup survey in the aftermath of the elections, 75% of the population, regardless of who they voted for, said to be surprised by the results. (Norman, Citation2016).

7 For a detailed explanation of the drafting of both documents, see Stolberg (Citation2012, pp. 73–91).

8 Gutiérrez underlines how immigration was a priority in Bush’s presidential campaign: “As a candidate he emphasized his deep cultural connections to Mexico, reminding Latino voters that he spoke Spanish, that his brother Jeb Bush, then Florida’s Governor, was married to a Mexican American woman, and that while he was governor of Texas he had visited with Mexican officials all along the border to improve political relations and spur economic development” (2007, p.71).

9 President Bush explained his position towards a comprehensive immigration reform in 2004, making it clear that the U.S. can enforce its laws and protect its borders, while still being a welcoming society for immigrants: “We’re a nation of laws and we must enforce our laws. We’re also a nation of immigrants and we must uphold that tradition, which has strengthened our country in so many ways. These are not contradictory goals” (Bush, Citation2006d, §5). See also Bush (Citation2004, §46–47); Bush (Citation2006a, §40); and Bush (Citation2006c, §11–13).

10 This remark is important given the reversal this idea suffers in Trump’s 2017 NSS. As shall be seen, President Trump sees foreign students as “non-traditional intelligence collectors”, therefore requiring to review visa procedures. (Trump, Citation2017b, p. 22).

11 For instance, Patrick characterized the 2015 NSS as a “document combining grand aspirations and intentions with an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink list of U.S. interests and initiatives” (Citation2015).

12 In 2013, a bipartisan group of eight senators drafted a bill that was consistent with the one envisaged by the president. It was introduced in April, passed by the Judicial Committee in May and finally approved by the Senate floor in June, with a 68–32 vote. The bill, however, would never make it to the House floor because there was not enough support from Republicans in that chamber. While House committees also worked on immigration related bills during 2013, none of them considered a path to citizenship for immigrants already present in the U.S. This proved to be the dividing issue that ultimately killed reform efforts in a Republican-led Congress (Chishti & Hipsman, Citation2013).

13 The Dream Act, which was originally introduced in 2001 has repeatedly failed to gain enough support in both chambers. After being continually reintroduced in the House and the Senate, the act has been opposed by those contending it grants amnesty to people unlawfully present in the country, and also by those who prefer to discuss the issue in a wider immigration reform debate. Youngsters known as Dreamers have been more politically active, underlining their “Americanness” and pressuring political actors to consider their demands and deliver solutions (Keyes, Citation2013).

14 There is a slight change in tone when compared to the 2010 NSS, where references to Congress were mainly in positive terms seeking collaboration and considering it a partner to work towards security objectives.

15 There is a section in the 2010 NSS titled “Strengthen the Power of Our Example” where this is more evident. Likewise, in the 2015 document, the first chapter states that the U.S. will lead with purpose, strength, by example, and with capable partners.

References

- Official documents

- National Security Strategies

- Bush, G. W. (2002, September). The national security strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: The White House. Retrieved February 15, 2019, from http://nssarchive.us/national-security-strategy-2002/

- Bush, G. W. (2006b, March). The national security strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: The White House. Retrieved February 15, 2019, from http://nssarchive.us/national-security-strategy-2006/

- Obama, B. (2010, May). National security strategy. Washington, DC: White House. Retrieved February 15, 2019, from http://nssarchive.us/national-security-strategy-2010/

- Obama, B. (2015, February). National security strategy. Washington, DC: White House. Retrieved February 15, 2019, from http://nssarchive.us/national-security-strategy-2015/

- Trump, D. J. (2017b, December). National security strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: White House. Retrieved February 15, 2019, from http://nssarchive.us/national-security-strategy-2017/.

- Other documents

- Ashcroft, J. (2001, October 25). Prepared Remarks for the US Mayors Conference. Department of Justice. Retrieved May 6, 2019, from https://www.justice.gov/archive/ag/speeches/2001/agcrisisremarks10_25.htm

- Bush, G. W. (2004, January 20). State of the Union. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2004/01/20040120-7.html

- Bush, G. W. (2006a, January 31). State of the Union. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2006/01/20060131-10.html

- Bush, G. W. (2006c, May 4). Remarks at a Cinco de Mayo Celebration. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-cinco-de-mayo-celebration-3

- Bush, G. W. (2006d, May 15). Address to the Nation on Immigration Reform. Retrieved May 12, 2019, from https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-nation-immigration-reform.

- Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act. (PL 99-433 1 October, 1986). 100 United States Statutes at Large, 992-1075b. Retrieved February 23, 2019, from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-100/pdf/STATUTE-100-Pg992.pdf

- Office of the Press Secretary. (2001, February 16). Remarks by President George W. Bush and President Vicente Fox of Mexico in Joint Press Conference. Rancho San Cristóbal, San Cristóbal, Mexico. Retrieved May 10, 2019, from https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2001/02/20010216-3.html

- Office of the Press Secretary. (2012, June 15). Remarks by the president on immigration. The White House. Retrieved May 27, 2019, from https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2012/06/15/remarks-president-immigration

- Trump, D. (2017a, January 20). The inaugural address. The White House. Retrieved May 31, 2019, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/the-inaugural-address/

- Trump, D. (2017c, December 18). Remarks by president on the administration’s national security strategy. The White House. Retrieved June 2, 2019, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-administrations-national-security-strategy/

- Secondary references

- Adamson, F. B. (2006). Crossing borders: International migration and national security. International Security, 31(1), 165–199.

- Bachrach, P., & Baratz, M. S. (1962). Two faces of power. American Political Science Review, 56(4), 947–952.

- Ballotpedia. (2016). United States Congress Elections, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from https://ballotpedia.org/United_States_Congress_elections,_2016

- Ballotpedia. (2018). United States Congress Elections, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2019, from https://ballotpedia.org/United_States_Congress_elections,_2018

- Balzacq, T. (2005). Three faces of securitization: Political agency, audience and context. European Journal of International Relations, 11(2), 171–201.

- Balzacq, T., Léonard, S., & Ruzicka, J. (2016). ‘Securitization’ revisited: Theory and cases. International Relations, 30(4), 494–531.

- Barilleaux, R. J., & Maxwell, J. (2017). Has Barack Obama embraced the unitary executive? Political Science & Politics, 50(1), 31–34.

- Baumgartner, F. R. (2015). Agendas: Political. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encsyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 362–366). Elsevier. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080970868930034?via%3Dihub

- Baumgartner, F. R., Green-Pedersen, C., & Jones, B. D. (2006). Comparative studies of policy agendas. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(7), 959–974.

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Jones, B. D. (2009). Agendas and instabilities in American politics. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

- Boot, M. (2017, December 18). Trump security strategy a study in contrasts. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved May 31, 2019, from https://www.cfr.org/expert-brief/trump-security-strategy-study-contrasts

- Bouton, M. M., & Page, B. I. (Eds.). (2002). Worldviews 2002. American public opinion and foreign policy. Chicago, IL: The Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

- Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security. A new framework for analysis. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Chishti, M., & Hipsman, F. (2014, January 9). U.S. immigration reform didn’t happen in 2013; Will 2014 s? Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved May 28, 2019, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/us-immigration-reform-didnt-happen-2013-will-2014-be-year

- Conklin Frederking, L. (2012). A comparative study of framing immigration policy after 11 September 2001. Policy Studies, 33(4), 283–296.

- Critelli, F. M. (2008). The impact of September 11th on immigrants in the United States. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 6(2), 141–167.

- Délano, A., & Serrano, M. (2010). Flujos migratorios y seguridad en América del sigration flows and security in North America]. In F. Alba, M. Á. Castillo, & G. Verduzco (Eds.), Migraciones Isnternacionales [International Migrations] (pp. 481–513). Mexico: El Colegio de México.

- Denning, S. (2016, November 13). The five whys of the Trump surprise. Forbes. Retrieved June 2, 2019, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/stevedenning/2016/11/13/the-five-whys-of-the-trump-surprise/

- Dionne, Jr., E. J. (2008). Migrating attitudes, shifting opinions. The role of public opinsion in the immigration debate. In R. Suro (Ed.), A report on the media and the immigration debate (pp. 63–83). Washington, DC: Governance Studies at Brookings.

- Doyle, R. B. (2007). The U.S. National Security Strategy: Policy, process, problems. Public Administration Review, 67(4), 624–629.

- Dunaway, J., Branton, R. P., & Abrajano, M. A. (2010). Agenda setting, public opinion and the issue of immigration reform. Social Science Quarterly, 91(2), 359–378.

- Eriksson, J., & Noreen, E. (2006). Setting the agenda of threats: An explanatory model. Uppsala Peace Research Papers No. 6. Uppsala: Department of Peace and conflict Research, Uppsala University. Retrieved April 8, 2019, from https://www.pcr.uu.se/digitalAssets/654/c_654444-l_1-k_uprp_no_6.pdf.

- Eriksson, J., & Noreen, E. (n.d.). Threat politics. Research project official website. Uppsala University. Retrieved April 8, 2019, from http://pcr.uu.se/research/archive/threat-politics

- Feaver, P. (2010, January 20). Holding out for the National Security Strategy. Foreign Policy. Retrieved February 24, 2019, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2010/01/20/holding-out-for-the-national-security-strategy/

- Feaver, P., & Inboden, W. (2016). Looking forward through the past. In H. Brands & J. Suri (Eds.), The power of the past (pp. 253–279). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Feaver, P. (2017a, June 14). The hardest part of Trump’s national security strategy to write. Foreign Policy. Retrieved February 24, 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/14/the-hardest-part-of-trumps-national-security-strategy-to-write-russia-hacking-disinformation/

- Feaver, P. (2017b, December 18). Five takeaways from Trump’s national security strategy. Foreign Policy. Retrieved February 19, 2019. https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/12/18/five-takeaways-from-trumps-national-security-strategy/