The appearance of Vol. 4, Issue 3, 2018 coincides with the very month in which one hundred years ago the fighting of World War I ended in November 1918. The scope of this Issue is taken from the English proverb that necessity is the mother of invention, meaning that needs are a powerful driving force of progress. Modern warfare, most notably the stalemate of the trenches and the arrival of aviation with its airborne surveys, demanded and received response from the cartography departments of the Allied and Central powers. In that respect the war, which was fought mainly but not exclusively in Europe and the Near East, certainly can be seen as an indeed terrible mother of invention, judging by the hitherto unimaginable scope of casualties and destruction for combatants and civilians alike, contributed to, in no small way, by the wartime progress of surveying and cartography. Therefore, thanks to the editors of the International Journal of Cartography, Anne Ruas and Bill Cartwright, this issue embraces their suggestion to mark the centennial with this themed Issue to the ‘Great War’ (), as contemporaries called the conflict of all major powers of these days until the even more destructive World War II came upon them.

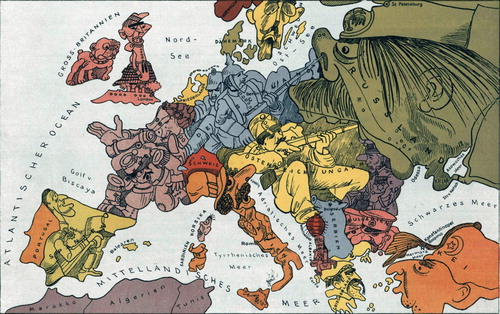

Figure 1. German cartoon map stereotyping the adversaries of the war in 1914 – before the mass casualties rendered such humorous propaganda improper. The artist, Walter Trier (1890–51), was a Jew who in 1936 exiled to London, where in World War II he drew cartoons for Germany’s enemies (Author’s collection).

This themed Issue in some way is a capstone of recent activities by the ICA Commission on the History of Cartography (https://history.icaci.org/) on military cartography with an emphasis on World War I. This focus was inaugurated four years ago by the Commission’s 5th International Symposium (Liebenberg, Demhardt, & Vervust, Citation2016) held in December 2014 in Ghent (Belgium), where there a hundred years ago on the fields of Flanders the attempted German ‘blitz’ turned into the long trench war of attrition.

When setting out on the project of this themed issue, the intention was to provide a comparative investigation of the diverse national approaches to wartime cartography on how the first truly global and industrialized war helped the development of new ways to capture survey data, speed up processing, as well as printing. That emphasis deliberately excluded maps on diplomacy and propaganda, which usually dominate the cartography of World War I imagination. In putting the Issue together, it soon became clear that in tracing the history of the wartime cartographies the international cast of authors reflects on the different directions and depths of hitherto research they were able to draw on. While for the western Allies a lot of original cartographic material and archival records survived and sustained numerous publications, the map historians of the Central Powers are fighting an uphill battle, to stay in military terms. Unlike the United Kingdom, France and the United States, most of the wartime cartography of Germany, Austro-Hungary and Russia, literally, was either dumped by the defeated armies or got lost during World War II. Moreover, there was little appetite amongst these ‘losers’ to pass on the cartographic stories of a lost cause.

Evidently, the cartography of the battlefields was not conceived after the first shot was fired. Rather to the contrary, official cartography, which at the outbreak of hostilities in most involved nations was housed within the military, and therefore focused its mapping endeavors on the needs of the armies rather than the growing civilian needs. Mapping out future ‘theatres of war’, as it was called in the nineteenth century, in fact, was one of the core objectives of the cartographers at the war departments in times of peace. Understanding that puts the papers' varying emphasis on pre-war cartography into perspective, which only gradually gave way to the transformational needs of modern warfare.

This Issue contains seven papers, including comprehensive surveys of the cartography of major combatant nations and shorter papers investigating a special aspect.

British Military Mapping on the Western Front 1914–18, by Peter Chasseaud, an independent scholar who has widely published on the cartography of the ‘Great War’, on the adaption of the British Expeditionary Forces to trench warfare conditions.

The legends of topographical men: the American army and mapmaking in World War I, by Ryan Moore, a cartographic specialist at the Library of Congress in Washington DC, on the late entry but well diversified mapping by the U.S. forces on the Western Front.

The Development of Photogrammetry in World War I, by Peter Collier, formerly geographer at Portsmouth University (UK) with specialization on surveying and topographic mapping, on how aerial photography revolutionized ‘real time’ revisions of existing and the compilation of new maps.

Russian military cartography in World War I, by Vladimir Bulatov, the curator of cartography at the State History Museum in Moscow, on how the aviation and the artillery needs transformed the Czarist war maps.

Germany and Austro-Hungary: The Cartography of the Defeated, by Jürgen Espenhorst, an eminent collector and independent scholar, reconstructing the wartime mapping efforts by the two cartographically dominating Central Powers.

Comparing different data sources and visualizing the mountain battlefield on the Soča front line, by Dušan Petrovič as the lead author, a professor of cartography in Ljubljana (Slovenia), on a modern imaging effort by analyzing historic spatial data on the upper Isonzo River.

Fighting the Great War at the Adriatic Sea: Charts by the Hydrographic Institute of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, by Mirela Altić, the chief research fellow at the Institute of Social Sciences in Zagreb (Croatia), on a case study in maritime cartography, which of all branches of military services had to rely the most on pre-war reconnaissance.

The space limitation of a journal issue restricts the number of themes, which can be accommodated by dedicated papers. Among these ‘casualties’ are the cartographies of the Near East and Africa as well as the plagiarizing of enemy maps, a common ‘transnational’ trait in World War I as in other prolonged military conflicts. To make good at least a bit on these misses, and adding another item of maritime war cartography, let me sneak in a chart example, illustrating how much efforts were invested even on a very marginal theater of the war.

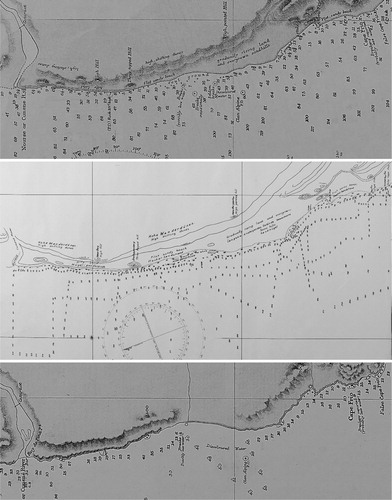

Figure 2. Extracts of charts of the Namib coast between the mouth of the Cunene River (17° 15’ S) and False Cape Frio (18° 29’ S), from left to right: Admiralty Chart 1806 in the last significantly revised pre-war edition 1909, 1915 navy print of a German 1912 coastal surveys, first wartime corrections of Admiralty Chart 1806 in 1916 – note the (uncredited for) extensive borrowing from the German 1912 survey on the 1916 edition. (United Kingdom Hydrographic Office, Archives, from left to right: OCB 1806, Series B, Sequence 5; C 6259/1; OCB 1806, Series B, Sequence 12).

The hostile coasts of the Namib Desert in southwestern Africa, although already discovered in the 1480s, were still poorly charted by the advent of the twentieth century, as the pre-war editions of the charts by the United Kingdom’s Department of the Admiralty clearly bear testament. For Admiralty Chart 1806, Great Fish Bay to Walfisch Bay, the last significantly revisions had been made in September 1909 (). Coastal surveys off the shores south of the mouth of the Cunene River, undertaken in 1912 by the German navy vessel Möwe and left as manuscript drafts in German Southwest Africa (modern Namibia), were captured by South African forces upon invading the poorly defended German colony in September 1914. Translated redrawings of this and other German draft charts were produced for classified use on 20 April 1915, because at that time the German colonial forces and settlers still held out in the hinterland of the extracted portion of the coast. This in spite the fact that Germany held no navy vessels in these waters and this segment of the Namib Desert, appropriately named Skeleton Coast, was not previously or since been voluntarily visited, but, for good reasons, avoided by all seafarers, naval, mercantile or even fishermen alike. Only after the surrender of the German forces on 9 July 1915, the content of the translated draft made its entry to the first printed and released wartime corrections of Admiralty Chart 1806 made on the edition of 8 September 1916.

The armistice the Central Powers – Germany, Austro-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire – had to ask for in November 1918, the subsequent collapse and break-up of these empires and, ultimately, the peace treaties in 1919 led to an extensive redrawing of the political map, especially in Central and Eastern Europe and on the Balkan. In turn, this brought (political) boundary surveys and cartography to its all-time peak, already premeditated by the 1917–19 president of the Royal Geographical Society, T.H. Holdich, during the close of the hostilities (Holdich, Citation1918). These cartographies, however, have to be left for another themed Issue …

References

- Holdich, T. H. (1918). Boundaries in Europe and the Near East. London: Macmillan.

- Liebenberg, E., Demhardt, I. J., & Vervust, S. (Eds.) (2016). History of Military Cartography. Heidelberg: Springer.