Abstract

The purpose of this Special Issue is to describe innovative school-related initiatives to reduce the population prevalence of youth mental health concerns. In this introduction to the Special Issue, we identify strategies that have not worked as well as those that have promise in improving youth mental health outcomes. We then provide a brief overview of each article in this issue. The first several articles focus on a comprehensive countywide approach to child and youth mental health that developed out of a unique tax initiative. In combination, these projects screen school-age youth in the county three times a year; support all county schools in providing universal, selective, and indicated interventions based on these screening data; deliver a mentoring program and school-based psychiatric care to youth with more intensive needs; and provide no-cost evidence-based evaluations, referrals, and ongoing progress monitoring to any family with concerns about their child’s mental health. Three additional articles in the Special Issue expand the focus to include other national models, including a statewide initiative in Georgia to bring mental health services to every school, policy issues related to school mental health in South Carolina, and cost analysis strategies for specifying the economic benefit of mental health initiatives.

As we embark on the third decade of the 21st century, it is again time to reflect on the state of youth mental health in the United States. For more than 50 years, research has documented the growing prevalence and burden of youth mental health concerns. For instance, national studies in the 1980s showed that rates of depression had increased exponentially, with school-aged children having a 10-fold increase in risk for severe depression compared to children born just three generations prior (Klerman & Weissman, Citation1989). At the turn of the 21st century, epidemiological studies revealed that nearly 20% of U.S. children would experience a serious mental health condition prior to adulthood (Merikangas et al., Citation2010, Citation2011). Unfortunately, these trends have persisted, if not escalated, during the most recent decade (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2019; Twenge et al., Citation2019). Today, youth are 50% more likely to experience a major depressive episode than in the early 2000s, and suicide rates are at an all-time high with the Centers for Disease Control reporting a 57% increase between 2007 and 2017 (Curtin & Heron, Citation2019).

Although these trends have drawn attention and concern as well as efforts to intervene or disrupt them (Weist et al., Citation2007), it has become abundantly clear that broader and more systemic approaches are needed if we are to improve the social, emotional, and behavioral health of youth in this country. The historical collective failure to reduce mental health concerns in youth is due in part to the way mental health is most commonly viewed and addressed (McLeod & Fettes, Citation2007). Namely, the primary mode of identification and intervention for mental health concerns continues to focus on the symptoms, help-seeking, and treatment of the individual (La Greca et al., Citation2009). Though it is important to provide supports and strategies to improve coping in youth struggling with mental health issues, we must more effectively address the systemic barriers that maintain the adversity, social inequity, and lack of opportunity that contribute to mental health concerns (Herman et al., Citation2004). A comprehensive solution involves a coordinated, participatory, and systemic community-wide response to these concerns, replacing the sole expert or professional authority-based approach that has traditionally been used to treat mental health concerns (Gambrill, Citation2001). Additionally, solutions will need to be rooted in an implementation science framework that effectively and sustainably bridges the science to practice gap (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Effective strategies will need to be co-produced in real-world contexts across a public health spectrum of services and settings (Weisz et al., Citation2005, Citation2013), including schools as primary venues for identification, prevention, and intervention strategies (Greenberg et al., Citation2003).

The purpose of this Special Issue is to describe several community-wide approaches for crafting solutions tailored to specific community needs that reduce the population prevalence of youth mental health concerns. Collectively, the articles in the Special Issue focus on comprehensive county- or statewide approaches to youth mental health. These include an integrated community-school-family public health approach to monitoring youth mental health concerns and intervening in them along a continuum of supports from universal prevention to intensive individualized services. Additionally, scholars describe statewide initiatives that bring mental health supports to youth in schools and address policy and cost analysis issues related to youth mental health. In this opening article, we discuss both effective and ineffective strategies, describe the process of creating and administering tax initiatives that support youth mental health, and provide a brief overview of the articles in the special issue.

INEFFECTIVE STRATEGIES AND PROMISING SOLUTIONS

Before describing possible solutions, it may be useful to reflect on what does not seem to be working. Communities and schools are actively engaged in addressing youth mental health concerns, and resources are being devoted to improving the social, emotional, and behavior health of youth (Weist et al., Citation2007). Unfortunately, many of the efforts simply do not work or, at least by themselves, are not reducing the population prevalence of mental health concerns.

Strategies That Do Not Work

First, waiting for youth with mental health concerns or their parents to present themselves for services, or hoping that school personnel will spontaneously identify and refer them, does not work (Cash & Nealis, Citation2004). The vast majority of youth who experience mental health concerns do not receive services (Merikangas et al., Citation2011). Low rates of access to services, despite growing need, have been persistent since at least the early 1990s (Keller et al., Citation1991; Lewinsohn et al., Citation1998). Instead of waiting for referrals that rarely happen, a coordinated prevention and public health approach is needed to effectively identify youth who are struggling with mental health concerns who—absent effective supports and treatment—will go on to require more intensive and expensive services later. Such approaches can include coordinated and reliable school-community linked mental health screening systems to identify individual youth in need and to produce data streams to monitor the most salient health risks of a population of youth in any given community (see Reinke et al., this issue; Thompson, Herman, et al., this issue). These data can be used by school professionals to identify the prevalence of risk factors at the county, district, school, or grade level to guide universal and indicated prevention strategies as well as by county leaders to inform policy and funding decisions. Additionally, data can be used as benchmarks to show whether a collective set of actions, programs, or funding is effectively reducing the prevalence rates or specific risks within a community.

Unfortunately, very few schools in the United States engage in this type of public health approach. In 2005, only 2% of U.S. public schools were engaged in regular screenings for mental health-related concerns (Romer & McIntosh, Citation2005). Surveys suggested that these practices increased to 12.6% of schools by 2010 (Bruhn et al., Citation2014) and 15.5% of schools by 2015 (Siceloff et al., Citation2017). Though current-year data are not yet available, continuing this trend suggests that at most 20% of schools engage in mental health screenings in 2020.

Second, individual and/or group counseling alone is not the solution. Simply providing more mental health services to youth will not, in itself, address the problem. Much research has shown that increasing and coordinating access to care, though an important public health imperative, does little to improve the quality of care (Bickman et al., Citation2000; Weisz, Citation2006). We have effective mental health interventions (e.g., Weisz et al., 2017), and youths who receive these evidence-based interventions benefit significantly more than those who receive typical services (Weisz et al., Citation2013). That so few receive evidence-based interventions in schools and clinics suggests the need to improve training and implementation support within these settings. Still, even high-quality, evidence-based interventions may not dramatically reduce the population prevalence of mental health concerns. These services are typically reactive rather than proactive and preventative (Reinke et al., 2006). They are also resource intensive; it is not practical or sustainable to offer them to a high percentage of youth. Although therapy can be helpful for individual youths and families when evidence-based models are used, it does little to alter the contextual factors in the broader social environment that contribute to, maintain, and exacerbate the problem in the first place. A data-driven, evidence-based continuum of care is needed so that the number of youths needing intensive services is manageable.

Third, the use of exclusionary discipline practices in U.S. schools do not support youth mental health. In fact, available evidence suggests that these reactive, punitive approaches aggravate the problem (Atkins et al., Citation2002). Additionally, youth at the highest risk of mental health concerns are the ones who are most likely to experience exclusionary discipline (Krezmien, Citation2006). Unfortunately, widespread use of these practices continues despite ample research demonstrating that they (a) fail to teach appropriate decision-making skills, (b) are applied in a racially disproportionate manner, and (c) contribute to the school-to-prison pipeline (Skiba et al., Citation2014). The solution to successfully promoting mental health is to create safe contexts and a culture of caring and support to buffer the risk factors that youth are exposed to inside and outside of schools (Biglan et al., Citation2012)—not to exclude and punish undesirable behaviors that may be the symptoms of a deeper systemic problem. Reactive and punitive responses provide another example of how current practices place the origin and source of mental health problems within the individual student rather than examining the systemic responses that worsen the problem.

Fourth, training teachers and other school professionals to be more knowledgeable about identifying mental health concerns also will not reduce their population prevalence. As one prominent example, the federal government recently invested tens of millions of dollars in the dissemination of the Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) program to address youth mental health concerns (Jorm, Citation2012). This full-day youth MHFA training program teaches adults to identify common mental health symptoms and to refer youth who show these problems. Though education about mental health symptoms, conditions, and ways to respond are a useful first step (Jorm, Citation2012), such approaches do little to help educators learn and implement supports for struggling students or create classroom environments that protect youth from mental health problems (Biglan et al., Citation2012; Embry, Citation2002). Furthermore, approaches like MHFA can reinforce a participant’s view that mental health problems reside solely within the individual and may fail to increase educators’ support for youth with mental health concerns (Jorm et al., Citation2010). Moreover, trainings like MHFA perpetuate the view that the simple solution to the youth mental health crisis is to find youth who need counseling and refer them for services. Training for teachers and parents and other community members needs to situate the problem in context and focus on the malleable antecedents in schools and communities that directly influence youth mental health problems. In turn, trainings should empower adults to identify and alter these risk conditions.

Fifth, even systemic approaches that only focus on one setting are unlikely to reduce the prevalence of youth mental health concerns (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, Citation1997). Obviously, both families and schools play a significant role in shaping youth development and well-being, but neither setting alone is fully responsible for the myriad risks that youth experience. Many of the most significant risks for mental health concerns occur across home, community, and school settings in a cultural context that shapes and influences how these risks will be realized (Herman et al., Citation2004; Reinke & Herman, Citation2002). A better coordinated, well-integrated continuum of care is needed. Unfortunately, such coordination is often lacking (e.g., therapists rarely coordinate with teachers; schools may not involve parents). Many families, often with the most intense needs, do not feel welcome at school, and school professionals may harbor biases that discourage their participation (Stormont et al., Citation2013).

Strategies With Promise

Much in school psychology has already been written about multitiered systems of support rooted in a public health perspective such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS; McIntosh & Goodman, Citation2016). We believe that such a continuum of support is part of the solution, but there are other elements described in this Special Issue that can support a more robust child-family-school-community approach to building these systems.

First, policy changes, including legislative actions and tax initiatives, will almost certainly be part of any solution to improve the health of youth in this nation (Blackburn Franke et al., this issue). Part of the reason that schoolwide PBIS has become so widely disseminated in this country, with over 20,000 schools implementing it, is because of federal legislation. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (Citation1997) included language that required schools to consider positive behavioral interventions to address student behavior concerns; in Citation2004, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act was revised and specific language was added about positive behavioral interventions and supports.

Despite these advances, the evidence-based and standards movement that has dominated education and social systems for the past several decades has yielded a nearly singular focus on improving the inputs surrounding the indicators or metrics used to appraise the effectiveness of the system, namely, academic achievement. In other words, if we gauge school effectiveness using only math and literacy scores, then schools will focus exclusively on improving math and literacy scores at the expense of other investments, such as healthy school climates. Ironically, this singular investment may not only fail to cultivate a healthy child (and future citizen) but it may also fail to yield the highest math and literacy scores. Policies that evaluate schools based on positive, safe, and supportive climates are also critical. Outside the family, schooling in the United States is the first and largest system within which most youth receive a bulk of their formal socialization experiences. If social support and belongingness, a sense of safety, and having one’s basic needs met are prerequisites for performing well on academic tasks, then it should also be essential to measure a school’s efforts and effectiveness to create climates that feel supportive to students.

Second, participatory research methods and co-produced interventions can help generate solutions that meet the needs of schools and communities for improving youth mental health (Holmes et al., this issue). Decades of research have produced scores of efficacious interventions, many of which are not used, or not used as intended, in schools or communities. Unfortunately, these “graveyards” of fully developed but unused interventions will not be part of the solution (Dishion, Citation2011). In the past, it was reasonable for intervention developers to create and test interventions in isolation from contexts to first establish whether psychosocial interventions could actually reduce youth symptoms and disorders. We now have abundant evidence that indeed they can (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, Citation2009). At this point in history, there is no need to invent new interventions in isolation from the contexts in which they will be delivered (Cappella et al., Citation2011; Weisz & Gray, Citation2008). All future interventions should be co-developed alongside those who deploy them in real-time settings where they will be used with consumers who will receive them to ensure contextual fit and enhance implementation quality by natural implementers.

Third, the ongoing collection of data to inform practice and impact policy will be part of any solution. This includes collecting process data (e.g., fidelity to models, training of problem-solving teams, buy-in, treatment acceptability) as well as reliable streams of data to monitor the presence and patterns of risk factors. A significant amount of observational research has been published over the past half century documenting the nature, prevalence, and impact of a variety of social risk factors known to be detrimental to typical human development. This body of evidences provides us with a fairly substantial understanding of these risk factors, how to measure them, and programs and practices that can buffer their effects. However, without feasible systems to capture reliable data on relevant indicators of youth risk, educators and community members are left guessing what it is that they need to do to prevent these problems from taking root in the lives of unaffected youth or from getting worse in youth who are experiencing the early signs of these risk factors. To build better systems to respond to these concerns, we need to develop data systems with community input tracking indicators that are meaningful to all members of a community.

Fourth, interventions need to be grounded in sound theory and flexible to context (Webster-Stratton et al., Citation2011). In particular, recent theories of change have led to common content across proven interventions. In turn, modern improvements in interventions have led to current transdiagnostic and flexible approaches that are focused less on what exactly to say or do each session and more on what needs to change in the youth or in the system (e.g., Cho, Marriott, et al., this issue; Ehrenreich-May & Chu, Citation2013; Weisz et al. 2017).

Fifth, training school personnel to deliver high-quality interventions requires ongoing coaching and feedback about their implementation. Ample research reveals that routine assessment and feedback promotes student (Thompson et al., Citation2020), teacher (Reinke et al., Citation2011), and clinician (Lambert, Citation2015) behavior change and skill. Additionally, tools have been developed to provide ongoing performance feedback to clinicians to ensure that they are implementing high-quality evidence-based interventions (Hawley, Citation2011, Citation2013).

Sixth, leadership buy-in and leadership teams is central to elevating the role of schools in promoting socially responsible behavior among students. The influence that a building leader has on a school building and all of its staff and students cannot be overstated. A building leader who prioritizes quality practices and programs, who speaks highly of staff who enact the practices, and who promotes professional development and coaching for all staff to engage in practices that support student development of positive inter- and intrapersonal problem-solving skills is key in creating a culture of caring in a school. Training along with coaching and data streams from which to promote leadership decision making around the social emotional health of students in a school must be central parts of the vision of those who seek to become school leaders. School climates, and the personnel and students who contribute to them, are highly influenced by leadership. As such, leaders must have a solid understanding of, and access to, tools to improve their capacity to elevate their education system’s responsibility to impart social, emotional, and behavioral health strategies to students (Astor et al., Citation2009).

CREATING AND ADMINISTERING A TAX FUND TO SUPPORT YOUTH MENTAL HEALTH

A growing wave of communities across the United States are passing legislation to fund youth mental health services with taxes. For instance, Denver became perhaps the first large city to do so when it recently passed a ¼ cent sales tax initiative to be used to support mental services. These tax initiatives have origins in legislative actions taken in Midwestern states 3 decades ago. In Missouri, legislators passed a law that allowed counties and St. Louis city to pass voter-approved property taxes to be used to support youth well-being in 1993. The law was expanded in 2000 to include sales taxes. Since then at least nine counties in Missouri have passed sales tax initiatives and created funds to support youth mental health. Many other counties in Illinois have passed similar initiatives.

The activities described in the first seven articles of the Special Issue were funded by such a sales tax initiative. The Boone County Children’s Services Fund tax passed in November 2012. It was the third time that the tax had been presented to the voters. After failing twice before, citizens again asked county commissioners to put the tax back on the ballot, but they refused to do so and forced a petition initiative instead. This sent a group of dedicated professionals, many early childhood providers and advocates who knew the importance of getting the tax passed, out to collect enough signatures to get the initiative back on the ballot. This group also initiated a public education campaign about the benefits of the tax. Ultimately, the tax passed with 57% approval, a relative landslide by modern political standards.

The primary group that ushered the tax forward was led by child care providers who had witnessed firsthand the high percentage of families and children who went without care because of access and affordability issues. The group called themselves Putting Kids First (PKF). PKF conducted a community needs assessment to justify the tax. The needs assessment revealed that the issues that resonated the most with taxpayers were concerns about teen suicide and substance abuse. PKF used this information to create messages for a marketing campaign to make voters aware of why the tax was needed and how it could help address these concerns.

After it was passed, the tax was overseen by the Children’s Services Board. The Board has primarily funded programs through a request for proposal process, with strict deadlines and guidelines for a prescribed period of funding. Requests for proposal were written to focus on community needs as identified by needs assessments and later by data that were being gathered and reported to the Board by each of the funded programs. The Board was also interested in creating opportunities to fund innovative programs or address emerging community needs when they did not have an open request for proposals and therefore allocated some funds just for those opportunities.

Every organization that received funds from the tax is required to submit a logic model and provide semi-annual reports with data showing progress toward targeted outcomes that were proposed. The Director of the Board meets regularly with the leaders of each of the funded programs. These working relationships with program leaders were viewed as critical to ensure successful implementation and clear communication so that any challenges to achieving goals would be reported and addressed in partnership. Creating these trusting partnerships was one of the most critical and challenging aspects of ensuring accountability because programs were fearful of losing their funding and yet accurate reporting of progress was essential to achieve county goals.

In our view, transparency was the key to sustainability. It is very important to share and celebrate success, but it is equally important to share challenges and failures. When taxpayers have confidence that their funds are being used to benefit the lives of children and families (celebrating success) and also know that when something is not working (admitting to challenges and failures) there is accountability and continuous quality improvement, they will continue to support the tax and the model will be sustained over time.

Such tax initiatives hold promise for creating unique funding streams that can be used in targeted and grand ways to support youth mental health. We hope that the lessons our county has learned over the past decade will be useful to other counties and municipalities as they pass and administer similar taxes to ensure they impact youth as intended.

SUMMARY OF ARTICLES IN SPECIAL ISSUE

The articles in this Special Issue attend to many of the promising practices described previously. The first seven articles in this special focus on a comprehensive, multitiered approach to youth mental health in medium-sized county in Missouri. We believe that, collectively, these articles can serve as a model for other communities to emulate for addressing the multifaceted challenges of improving population health.

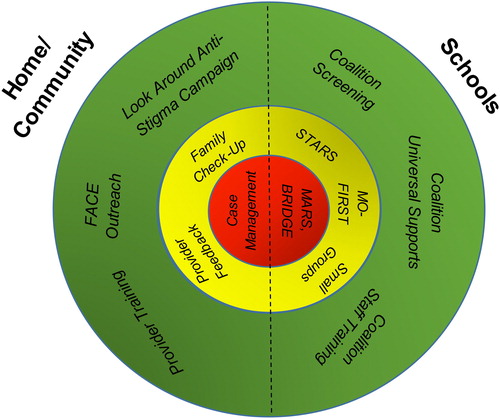

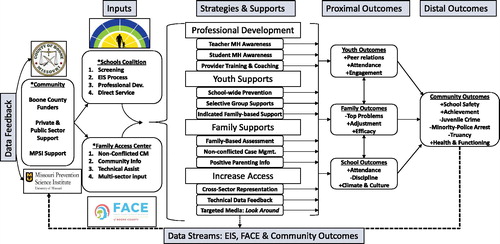

The first seven articles focus on a comprehensive, multitiered approach to youth mental health in medium-sized county in Missouri. As depicted in , these seven papers describe an integrated approach for offering universal, selective, indicated, and intensive individualized supports for youth across community and school settings. The universal community components include Look Around, a mental health stigma reduction campaign that was associated with youth improved attitudes about mental health and willingness to seek help (Thompson, Hollis, et al., this issue); outreach to increase community awareness of mental health and services (Thompson, Herman, et al., this issue); and community mental health provider training in evidence-based practices (Hawley, Citation2011). In schools, the universal components include triannual mental health screening of every youth attending county schools, school staff training and support, and the provision of universal preventive supports and interventions based on the screening data all created and delivered by the County Schools Mental Health Coalition (the Coalition; Reinke et al., this issue).

Indicated community supports include provider feedback about how well they are delivering evidence-based interventions to youth and a Family Check-Up intervention that is available to all families in the county through a Family Access Center of Excellence (FACE) to help motivate and connect them to relevant mental health services for their child and family (Thompson, Herman, et al., this issue). School-indicated supports include a self-monitoring intervention for youth with early signs of aggressive or disruptive behaviors (STARS; Holmes et al., this issue), a common factors intervention for youth displaying internalizing problems (MO-FIRST; Cho, Hawley et al., this issue), and small-group interventions. Finally, community-level intensive indicated interventions include ongoing case management delivered through FACE (Thompson, Herman, et al., this issue). In schools, intensive indicated interventions include a school-based psychiatry program (Cho, Marriott et al., this issue) and a mentoring program for students in alternative school settings (Henry et al., this issue). FACE and Coalition represent the hubs of community and school mental health response, respectively. Their interconnections and joint logic models for impacting the prevalence of youth mental health concerns are depicted in .

This first set of articles provides evidence of the effectiveness of these programs and practices. High-quality implementation of the Coalition model was associated with more adaptive student symptom growth patterns over a three-year period (Reinke et al., this issue). Youth who engaged in FACE services had significantly better school outcomes compared to similarly situated youth who did not engage in services (Thompson, Herman, et al., this issue). Youth exposed to the Look Around campaign had significantly improved attitudes about help-seeking and stigma (Thompson, Hollis, et al. this issue). Additionally, youth who received the more intensive supports offered through the school-based psychiatry program and the alternative school intervention had significant symptom improvements. Finally, these articles highlight the promise of two co-produced interventions tailored for delivery in school contexts (Cho, Hawley et al., this issue; Holmes et al., this issue).

The final three articles expand the focus to a national level. First, DiGirolamo and colleagues (this issue) describe a statewide program has been implemented for the past 4 years, focusing on partnerships between community-based providers and local school systems, with providers embedded within the school system delivering services for children identified with more serious mental health needs. This program also works with school personnel to provide activities aimed at promoting mental health awareness and positive school climate. The article describes implementation of the statewide School-Based Mental Health program, along with evaluation results showing the impact of the program on increasing access to services and on key aspects of school climate.

Second, Bradshaw and colleagues (this issue) describe the development of a cost analysis tool that schools can use to assess expenses related to various implemented interventions. They provide a detailed example and tutorial applied to the statewide implementation of PBIS. This study leverages administrative data from the scale-up of PBIS in the state of Maryland to estimate the benefit-cost ratio associated with reduced suspensions and improved academic performance statewide. Specifically, they calculated the benefits of PBIS reported in a recent quasi-experimental scale-up study in relation to the estimated costs associated with statewide implementation. They also consider the role of partnerships and braided funding streams that may serve as a model for other statewide mental and behavioral health initiatives.

Finally, Blackburn Franke and colleagues (this issue) describe a policy approach to improving youth mental health services and outcomes. South Carolina is a leading state for the delivery of comprehensive school mental health services, involving mental health-education system partnerships. Currently, more than 60% of schools include clinicians from the state Department of Mental Health, and there is a widely endorsed goal for this to be 100% of South Carolina schools by 2022. The article provides a background on the development of the school mental health model with emphasis on major policy initiatives and communities of practice that are propelling the work forward.

CONCLUSION

We have much room for growth and improvement when it comes to better meeting the mental health needs of our youth. The Special Issue is intended to advance the conversation and ideas about potential solutions that will finally improve the social, emotional, and behavioral health of youth on a grand scale. Collectively, these articles represent promising approaches for reducing rates of youth mental health concerns through effective policies, coordinated care, and data-driven decisions.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Keith C. Herman

Keith C. Herman, PhD, is a Curator’s Distinguished Professor in the Department of Education, School, & Counseling Psychology at the University of Missouri. He is the co-founder and co-director of the Missouri Prevention Science Institute. He has an extensive grant and publication record including over 140 peer-reviewed publications in the areas of prevention and early intervention of child emotional and behavior disturbances and culturally sensitive education interventions.

Wendy M. Reinke

Wendy M. Reinke, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Education, School, & Counseling Psychology at the University of Missouri. She is the co-founder and co-director of the Missouri Prevention Science Institute. She has an extensive grant and publication record including over 100 peer-reviewed publications and over $40 million in grant funding in the areas of prevention and early intervention of child emotional and behavior disturbances. She is also the director of the National Center for Rural School Mental Health and the co-developer and leadership team member for the Family Access Center of Excellence and the Boone County Schools Mental Health Coalition.

Aaron M. Thompson

Aaron M. Thompson, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Missouri. He is the associate director of the Missouri Prevention Science Institute. Dr. Thompson developed the Self-management Training And Regulation Strategy (STARS) intervention, an evidence-based Tier 2 support for youth with disruptive behaviors. He is also the co-developer and leadership team member for the Family Access Center of Excellence and the Boone County Schools Mental Health Coalition.

Kristin M. Hawley

Kristin M. Hawley, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences at the University of Missouri. She is also the director of the Center for Evidence-Based Youth Mental Health. She is the co-developer and leadership team member for the Family Access Center of Excellence.

Kelly Wallis

Kelly Wallis, JD, is the former director of the Boone County Community Services Department and currently works as a family law attorney.

Melissa Stormont

Melissa Stormont, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Missouri. She is co-director of the Boone County Early Childhood Coalition. She is also a member of federal grant teams focused on personal preparation and supportive library programing for young children with disabilities.

Clark Peters

Clark Peters, PhD, JD, is an associate professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Missouri. He also has appointments at the Truman School of Public Affairs and the University of Missouri Law School. He is a member of the Family Access Center of Excellence leadership team and co-founder and director of the Center for Criminal and Juvenile Justice Priorities.

REFERENCES

- Astor, R. A., Benbenishty, R., & Estrada, J. N. (2009). School violence and theoretically atypical schools: The principal’s centrality in orchestrating safe schools. American Educational Research Journal, 46(2), 423–461. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831208329598

- Atkins, M. S., McKay, M. M., Frazier, S. L., Jakobsons, L. J., Arvanitis, P., Cunningham, T., Brown, C., & Lambrecht, L. (2002). Suspensions and detentions in an urban, low-income school: Punishment or reward?Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30(4), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015765924135

- Bickman, L., Lambert, E. W., Andrade, A. R., & Penaloza, R. V. (2000). The Fort Bragg continuum of care for children and adolescents: Mental health outcomes over 5 years. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(4), 710–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.68.4.710

- Biglan, A., Flay, B. R., Embry, D. D., & Sandler, I. N. (2012). The critical role of nurturing environments for promoting human well-being. The American Psychologist, 67(4), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026796

- Blackburn Franke, K., Paton, M., & Weist, M. (2021). Building policy support for school mental health in South Carolina. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 110–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1819756

- Bradshaw, C. P., Lindstrom Johnson, S., Zhu, Y., & Pas, E. T. (2021). Scaling up behavioral health promotion efforts in Maryland: The economic benefit of positive behavioral interventions and supports. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1823797

- Bruhn, A. L., Woods-Groves, S., & Huddle, S. (2014). A preliminary investigation of emotional and behavioral screening practices in K–12 schools. Education and Treatment of Children, 37(4), 611–634. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2014.0039

- Cappella, E., Reinke, W. M., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2011). Advancing intervention research in school psychology: Finding the balance between process and outcome for social and behavioral interventions. School Psychology Review, 40(4), 455–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087524

- Cash, R. E., & Nealis, L. K. (2004). Mental health in the schools: It’s a matter of public policy. National Association of School Psychologists Public Policy Institute.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data Summary and Trends 2007-2017. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf

- Cho, E., Marriott, B. R., Herman, K. C., Schutz, C. L., & Young-Walker, L. (2021). Sustained effects of a school-based psychiatry program. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1811063 https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf

- Cho, E., Strawhun, J., Owens, S. A., Tugendrajch, S. K., & Hawley, K. M. (2021). Randomized trial of show me FIRST: A brief school-based intervention for internalizing concerns. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 52–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1836944 https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/trendsreport.pdf

- CurtinS. C. & HeronM. P. (2019). Death rates due tosuicide and homicide among persons aged10–24: United States, 2000–2017. NationalCenter for Health Statistics Data Brief, 352, 1–7.

- DiGirolamo, A. M., Desai, D., Farmer, D., McLaren, S., Whitmore, A., McKay, D., Fitzgerald, L., Pearson, S., & McGiboney, G. (2021). Results from a statewide school-based mental health program: Effects on school climate. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1837607

- Dishion, T. (2011). Promoting academic competence and behavioral health in public schools: A strategy of systemic concatenation of empirically based intervention principles. School Psychology Review, 40(4), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087532

- Ehrenreich-May, J., & Chu, B. C. (2013). Transdiagnostic treatments for children and adolescents: Principles and practices. Guilford.

- Embry, D. D. (2002). The Good Behavior Game: A best practice candidate as a universal behavioral vaccine. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5(4), 273–297. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020977107086

- Gambrill, E. (2001). Social work: An authority-based profession. Research on Social Work Practice, 11(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973150101100203

- Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R.P., O’Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., & Elias, M.J. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. The American Psychologist, 58(6-7), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.466

- Hawley, K. M. (2011). Clinician training in research supported interventions: Can it be affordable, accessible and effective? InBalance: Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology Newsletter, 26, 8–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/e567432011-007

- Hawley, K. M. (2013). Cognitive and Behavioral Therapy Adherence Measure (CBTAM). University of Missouri.

- Henry, L., Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., Thompson, A. M., & Lewis, C. G. (2021). Motivational interviewing with at-risk students (MARS) mentoring: Addressing the unique mental health needs of students in alternative school placements. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 62–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1827679

- Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., Thompson, A. M., Hawley, K. M., & Stormont, M. (2021). Reducing the societal prevalence and burden of youth mental health problems: Lessons learned and next steps. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1827683

- Herman, K. C., Merrell, K.W., Reinke, W. M., & Tucker, C. M. (2004). The role of school psychology in preventing depression. Psychology in the Schools, 41(7), 763–775. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20016

- Holmes, S. R., Thompson, A. M., Herman, K. C., & Reinke, W. M. (2021). Designing interventions for implementation in schools: A multimethod investigation of fidelity of a self-monitoring intervention. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 42-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1870868

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1997, Pub. L. 94-142, §614, 672 (1997). Retrieved October 21, 2010, from http://www2.ed.gov/offices/OSERS/Policy/IDEA/index.html

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004, Pub. L. 108-446, §611, 612, 614, 665, 118 Stat 2647 (2004). Retrieved October 21, 2010, from http://idea.ed.gov/

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. The American Psychologist, 67(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025957

- Jorm, A. F., Kitchener, B. A., Sawyer, M. G., Scales, H., & Cvetkovski, S. (2010). Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-51

- Keller, M., Lavori, P., Beardslee, W. R., Wunder, J., & Ryan, N. (1991). Depression in children and adolescents: New data on “undertreatment” and a literature review on the efficacy of available treatments. Journal of Affective Disorders, 21(3), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(91)90037-S

- Klerman, G. L., & Weissman, M. M. (1989). Increasing rates of depression. JAMA, 261(15), 2229–2235. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1989.03420150079041

- Krezmien, M. P., Leone, P. E., & Achilles, G. M. (2006). Suspension, race, and disability: Analysis of statewide practices and reporting. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14(4), 217–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/10634266060140040501

- La Greca, A. M., Silverman, W. K., & Lochman, J. E. (2009). Moving beyond efficacy and effectiveness in child and adolescent intervention research. J Consult Clin Psychol, 77(3), 373–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015954

- Lambert, M. J. (2015). Progress feedback and the OQ-system: The past and the future. Psychotherapy, 52(4), 381–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000027

- Lambert, M. J., Whipple, J. L., Smart, D. W., Vermeersch, D. A., Nielsen, S.L., & Hawkins, E.J. (2001). The effects of providing therapists with feedback on patient progress during psychotherapy: Are outcomes enhanced?Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 11(1), 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663852

- Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J. R. (1998). Treatment of adolescent depression: Frequency of services and impact on functioning in young adulthood. Depression and Anxiety, 7(1), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)7:1<47::AID-DA6>3.0.CO;2-2

- McIntosh, K., & Goodman, S. (2016). Integrated multi-tiered systems of support: Blending RTI and PBIS. Guilford Publications.

- McLeod, J. D., & Fettes, D. L. (2007). Trajectories of failure: The educational careers of children with mental health problems. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 653–701. https://doi.org/10.1086/521849

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., … Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yped.2011.04.014

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J-P., Burstein, M., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., Georgiades, K., Heaton, L., Swanson, S., & Olfson, M. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/12480

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Reinke, W. M., & Herman, K. C. (2002). Creating school environments that deter antisocial behaviors in youth. Psychology in the Schools, 39(5), 549–559. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.10048

- Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Sprick, R. (2011). Motivational interviewing for effective classroom management: The classroom check-up. Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826130730

- Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Sprick, R. (2011). Motivational interviewing for effective classroom management: The classroom check-up. Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1891/9780826130730

- Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., Thompson, A., Copeland, C., McCall, C. S., Holmes, S., & Owens, S. A. (2021). Investigating the longitudinal association between fidelity to a large-scale comprehensive school mental health prevention and intervention model and student outcomes. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1870869

- Romer, D., & McIntosh, M. (2005). The roles and perspectives of school mental health professionals in promoting adolescent mental health. In D. Evans, E. Foa, R. Gur, H. Hendin, C. O’Brien, M. Seligman, & B. Walsh (Eds.), Treating and preventing adolescent mental health disorders: What we know and what we don’t know. (pp. 598–615). Oxford University Press Inc. https://doi.org/10.1093/9780195173642.003.0032

- Siceloff, E. R., Bradley, W. J., & Flory, K. (2017). Universal behavioral/emotional health screening in schools: overview and feasibility. Report on Emotional & Behavioral Disorders in Youth, 17(2), 32–38.

- Skiba, R. J., Arredondo, M. I., & Williams, N. T. (2014). More than a metaphor: The contribution of exclusionary discipline to a school-to-prison pipeline. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(4), 546–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2014.958965

- Stormont, M., Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., David, K. B., & Goel, N. (2013). Latent profile analysis of teacher perceptions of parent contact and comfort. School Psychology Quarterl: The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 28(3), 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000004

- Thompson, A. M., Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., Hawley, K., Peters, C., Ehret, A., Hobbs, A., & Elmore, R. (2021). Impact of the family access center of excellence (face) on behavioral and educational outcomes—A quasi-experimental study. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1841545

- Thompson, A., Hollis, S., Herman, K. C., Reinke, W. M., Hawley, K., & Magee S. (2021). Evaluation of a social media campaign on youth mental health stigma and help-seeking. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 36–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1838873

- Thompson, A. M., Wiedermann, W., Herman, K. C., & Reinke, W. M. (2020). Effect of daily teacher feedback on subsequent motivation and mental health outcomes in fifth grade students: A person-centered analysis. Prevention Science, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01097-4

- Twenge, J. M., Cooper, A. B., Joiner, T. E., Duffy, M. E., & Binau, S. G. (2019). Age, period, and cohort trends in mood disorder indicators and suicide-related outcomes in a nationally representative dataset, 2005-2017. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(3), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000410

- Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (1997). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: a comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.93

- Webster-Stratton, C., Reinke, W. M., Herman, K. C., & Newcomer, L. L. (2011). The incredible years teacher classroom management training: The methods and principles that support fidelity of training delivery. School Psychology Review, 40(4), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2011.12087527

- Weist, M. D., Rubin, M., Moore, E., Adelsheim, S., & Wrobel, G. (2007). Mental health screening in schools. The Journal of School Health, 77(2), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00167.x

- Weisz, J. R., & Gray, J. S. (2008). Evidence‐basedpsychotherapy for children and adolescents: Data from the present and a modelfor the future. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(2), 54–65.

- Weisz, J. R., Bearman, S. K., Santucci, L. C., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2017). Initial test of a principle-guided approach to transdiagnostic psychotherapy with children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 46(1), 44–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1163708

- Weisz, J. R., Jensen-Doss, A., & Hawley, K. M. (2006). Evidence-based youth psychotherapies versus usual clinical care: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. The American Psychologist, 61(7), 671–689. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.671

- Weisz, J. R., Sandler, I. N., Durlak, J. A., & Anton, B. S. (2005). Promoting and protecting youth mental health through evidence-based prevention and treatment. The American Psychologist, 60(6), 628–648. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.628

- Weisz, J. R., Ugueto, A. M., Cheron, D. M., & Herren, J. (2013). Evidence-based youth psychotherapy in the mental health ecosystem. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42(2), 274–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.764824