Abstract

Social justice-centered training has progressed in school psychology, yet training and practice still do not adequately address systems-level influences on mental health, let alone focus on dismantling the systemic inequities that adversely affect the wellbeing of marginalized children and youth. An equity- and intersectional justice-minded framework for training future school psychologists in school-based mental health is presented, informed by the theories of intersectionality, critical race theory, social determinants of health, and radical healing. The proposed framework is based on reflective practice and incorporates three pillars that emphasize the importance of decentralizing psychodiagnostic assessment, centralizing systems-level work, and renewing focus on strengths and healing. To advance training that critically evaluates social factors that affect child wellbeing while honoring children’s identities and strengths, various ways in which graduate programs can enact this paradigm shift are discussed. Future directions for the field, including research and policy, are also presented.

Impact Statement

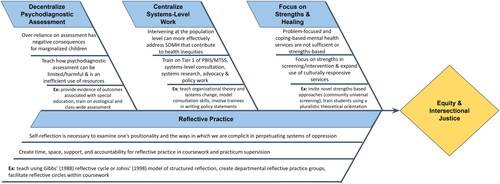

This article offers a framework to train school psychologists on how to intervene at the systems and societal levels to promote equity in child mental health. The first pillar emphasizes the need to decentralize psychodiagnostic assessment in school psychology practice—in order to move away from predominantly reactive, deficit-focused assessment activities that perpetuate inequities and to carve out more time for prevention of mental health difficulties and promotion of wellness. The second pillar centralizes systems-level work, particularly through additional training in MTSS, systems-level consultation to build capacity and develop novel initiatives to address social determinants of mental health, and advocacy and policy work. The third pillar involves training with a renewed focus on strengths, as helping marginalized children resist and heal from oppression requires reversing entrenched tendencies to pathologize, and building on individual, familial, and cultural strengths to foster wellbeing.

Associate Editor:

Malleable social, cultural, economic, and environmental forces contribute to the development of mental health problems and shape individuals’ access to and quality of mental health services (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010; Spencer, Citation2018). These social determinants of mental health (SDMH) can also obscure or hamper the strengths and resilience of marginalized individuals. SDMH are often directly related to public policies that inequitably distribute resources and differentially affect the population (Spencer, Citation2018). As a result, certain groups in the U.S.—especially children, people of color, Indigenous people, immigrant and non-English-speaking people, people from low-income backgrounds, people with disabilities, people from Muslim and other religious minority backgrounds, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and queer people—face increased exposure to conditions of risk and decreased access to care (Ghandour et al., Citation2019; Ka’apu & Burnette, Citation2019; Locke et al., Citation2017; Reichard et al., Citation2019; Rojas-Flores & Medina Vaughn, Citation2019; Samari et al., Citation2018; Sutter & Perrin, Citation2016).Footnote1

There is a growing awareness that social determinants of health (SDH) play a substantial role in influencing child physical and mental health starting as early as conception (Padula et al., Citation2020; Spencer, Citation2018). Additionally, recent estimates indicate that 22% to 47% of children with diagnosed mental health needs have not received care within the past year (Ghandour et al., Citation2019). In light of the early emergence of these effects and barriers to healthcare access among children, schools and school psychologists are theoretically well positioned to facilitate mental health service provision to children (National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), Citation2015). However, despite an increased focus on prevention and early identification of mental health problems (Marsh & Mathur, Citation2020), many systems in schools continue to operate from traditional medical models (Nastasi, Citation2004) that rely on individualistic, identity-blindFootnote2, pathologizing, and wait-to-fail paradigms, such as relying on one-off referrals for counseling made by individual teachers who have observed externalizing behaviors in the classroom, completing office discipline referrals for behavior problems, or only identifying children in need of services after they have been struggling socially, emotionally, or academically for a prolonged period of time. This paper offers a new path forward for training future school psychologists to provide school-based mental health services that respond to children’s identities and SDMH, and center wellness and healing.

CURRENT SYSTEMS OF SCHOOL-BASED MENTAL HEALTH

Current systems of school-based mental health are increasingly characterized by a multitiered systems of support (MTSS) framework; accordingly, school-based mental health professionals are increasingly trained in such frameworks. MTSS emerged out of the recognition that it is important to prevent the development or worsening of mental health and academic problems by providing a full continuum of prevention services, including a school-wide foundation of positive school climate and high-quality instruction, as well as differentiated supports tailored to students’ needs (Marsh & Mathur, Citation2020). Implementation of social–emotional/behavioral MTSS models may be particularly lacking, with only a small percentage of schools nationwide implementing the school-wide positive behavioral supports essential to Tier 1 with high quality (Freeman et al., Citation2016; Molloy et al., Citation2013; Spaulding et al., Citation2008).

Limited Use of Culturally Responsive Practices

Real-world implementation of MTSS in schools seems to largely lack attention to children’s intersecting identities or SDMH, although some prior research has examined how MTSS can be implemented in a culturally and linguistically responsive manner. For example, Bal and colleagues (Citation2014), in partnership with school staff, used a participatory social justice framework to identify families who were marginalized and underrepresented in school activities and then invited these families to participate in a “Learning Lab” process, in which the group engaged in an ongoing, unreserved dialogue about school climate, deficit-based perspectives, and discrimination. This process helped initiate problem-solving around school-based mental health implementation issues and sustain systems change to address inequities in school discipline that disproportionately affected African American students. In another example, Cressey (Citation2019) reported on a case study of implementation of culturally responsive PBIS (CRPBIS) at a two-way English–Spanish dual language immersion school. Components of CRPBIS implementation included practices such as having students explore their cultural identities, teaching about various multilingual groups, and administering a school climate survey to families annually as a part of continuous improvement efforts.

Unfortunately, these programs appear to be the exception rather than the norm. The lack of a culturally and linguistically responsive foundation to MTSS is evident, for example, in a recent review of state-level procedural guidance for implementation of behavioral MTSS (Briesch et al., Citation2020). The procedures reviewed did not describe any state practice guidelines related to how educators must consider and integrate the layered identities, experiences, and contexts of the students and families they serve. There are also concerns about the cultural responsiveness of the assessment instruments and intervention approaches commonly used in social–emotional/behavioral MTSS; thorough psychometric investigations with diverse populations are still uncommon among many widely-used instruments (Marti et al., Citation2021).

Even when there is evidence of measurement equivalence or minimal differential item functioning across subgroups for a given universal screener or progress monitoring instrument, this does not guarantee equitable use of the measures within MTSS (Barger et al., Citation2020). That is, in a poorly implemented MTSS model, an elevated score during universal screening may be used as the sole criterion for referring a child for Tier 2 intervention—without consideration to whether 1) the score has been triangulated with other data; 2) Tier 1 interventions and supports are culturally and linguistically responsive and implemented with fidelity in a truly universal manner (i.e., across all classrooms); or 3) the school climate provides foundational physical and psychological safety for marginalized groups (Gregory & Fergus, Citation2017; Noltemeyer et al., Citation2018; Sullivan et al., Citation2020). If marginalized students are inappropriately provided more intensive supports based on MTSS teams’ high-inference hypotheses (i.e., hypotheses focused on within-person factors, like personality or aptitude; Christ & Arañas, Citation2014), or provided with Tier 2–3 interventions that are identity-blind or not responsive to power, privilege, and oppression (e.g., Check In/Check Out facilitated by a teacher whose implicit or explicit biases prevent healthy student–teacher relationship building), these approaches will likely be ineffective at promoting student wellness or preventing exclusionary discipline (Gregory & Fergus, Citation2017; Hoffman, Citation2009).

Insufficient Centering of SDMH, Cultural Strengths, and Resilience

In addition to the limited use of culturally responsive practices, implementation of MTSS does not generally appear to center SDMH, cultural strengths, or resilience. Even within a tiered system, it is still possible to utilize individualistic and identity-blind assessment practices that overlook the impact of SDMH and cultural strengths. Subsequently providing children with individual- and problem-focused interventions that are likewise not culturally and linguistically responsive may, in turn, fail to foster wellness or address underlying systemic causes (Shim et al., Citation2014) and may reinforce deficit-based narratives about marginalized groups (Harry & Klingner, Citation2007). Thus, without full consideration of the intersecting SDMH that play a role in child wellbeing and an explicit centering of strengths and equity, well-meaning prevention models will likely perpetuate existing inequities (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010).

CURRENT TRAINING IN SCHOOL-BASED MENTAL HEALTH

To date, intersectional SDMH, strengths, and equity have not been centered in the implementation of MTSS, nor in the psychology training programs that prepare practitioners to operate within such frameworks (Woods-Jaeger et al., Citation2020). For instance, there are no widely agreed upon intersectional justice training standards in school psychology. Further, in some training programs, discussion of intersectionality, equity, and justice may be limited to a single course on diversity and multiculturalism, or not covered at all (Newell et al., Citation2010). Similarly, it is unlikely that a SDMH framework has widely permeated the field or training programs, as a search (in December 2021) for peer-reviewed articles explicitly discussing social determinants and school psychology yields no results.

The new Standards for Graduate Preparation of School Psychologists adopted by NASP in July 2020 demonstrate movement toward more equitable school-based mental health practice. NASP-approved programs will be expected to ensure that their school psychologist trainees develop competence in supporting multitiered prevention programs and delivering mental health services informed by an understanding of the biological, cultural, developmental, and social influences on mental wellness (National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), Citation2020). The new standards also highlight that school psychologists must be proficient in equitable and ecologically sensitive practices for serving diverse student populations (National Association of School Psychologists (NASP), Citation2020).

Although the new standards acknowledge the need for training in MTSS and ecologically-sensitive service provision, these standards are characterized as distinct competencies. Further, the standards do not attend to the confluence of biological, developmental, cultural, and social influences on mental health (i.e., SDMH) and the interaction of those factors with systems of power (i.e., intersectionality), nor do they explicitly require competence in integrating MTSS and equity. It is not a given that implementation of MTSS will be equity-focused rather than compliance-focused (Sabnis et al., Citation2020). Without explicitly acknowledging the complex influence of SDMH and role of power in shaping child health and healthcare access/quality (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010), training in school-based mental health is likely to proceed in its focus on identity-blind, individual-centered practice (Conoley et al., Citation2020; Speight & Vera, Citation2009). Further guidance on the new standards could assist training programs in shifting toward reducing the impact of inequitably distributed SDMH and providing healing-centered services. The new training framework presented in this paper also aims to promote an emphasis on SDMH and strengths-based healing in school-based mental health service provision.

EQUITY AND INTERSECTIONAL JUSTICE

Existing models for school psychology training and practice largely ignore the complex influences of public policies and SDMH on the wellbeing of multiply-marginalized children (Conoley et al., Citation2020; Graves et al., Citation2014; Woods-Jaeger et al., Citation2020). Although school psychologists are obviously not solely responsible for ameliorating the underlying SDMH that contribute to mental health disparities, the failure of the field to consistently and significantly advance beyond a traditional and reactive assessment-focused role reflects our complicity with maintaining the status quo (Conoley et al., Citation2020; Prilleltensky, Citation1997). By allowing training and practice to continue to center on our role as evaluators and gatekeepers to special education (Graves et al., Citation2014), school psychologists are limited in the time and extent to which we can engage in systems- and population-level intervention to effect change for mental health equity. By not intervening in this way, existing social inequities are allowed to perpetuate and compound over time (Spencer, Citation2018). Even worse, our power as decision makers on school-based teams coupled with identity-blind practices may directly harm marginalized children by implicitly or explicitly transmitting racism, classism, ableism, and other oppressive ideologies, providing ineffective interventions, or subjecting children to inappropriate or segregated placements (Gherardi et al., Citation2020; White et al., Citation2019).

The enormous changes to the U.S. educational landscape that emerged in the wake of the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic laid bare many inequities, particularly those affecting students of color, students with disabilities, and multilingual students (Dorn et al., Citation2020; Fairfax County Public Schools & Office of Research & Strategic Improvement, Citation2020). The effects of the pandemic and enormous loss of life, which has disproportionately harmed Black, Indigenous, and Asian communities in the U.S. (Tai et al., Citation2021; Wu et al., Citation2021), have elicited great distress, anxiety, depression, behavioral disruptions, and grief (Racine et al., Citation2020)—highlighting an urgent need for schools and communities to recognize and support children’s mental health. The context of the pandemic has provided a chance to reimagine structures and systems previously perceived as immutable, and presents a critical opportunity to transform education and school psychology; thus, we posit the question: What if equity and intersectional justice were guiding beacons in the training and practice of school-based mental health?

Equity in mental health can be conceptualized as the absence of systematic differences in mental health (including in access to care, quality of care, outcomes, and overall wellness) across social, economic, demographic, geographic, or otherwise defined groups (Starfield, Citation2001, p. 546). As exposure to vulnerability factors, quality of care, and outcomes are currently unequal and unjust, equality in mental health treatment—that is, all individuals receiving the same access and care, or an identity-blind approach—will not lead to equal and flourishing experiences and outcomes for all (Mangalore & Knapp, Citation2006). An equitable approach to school-based mental health must therefore aim to dismantle existing structures that foster differential risk and provide each child with the supports needed based on their unique identities and contexts to experience wellness and healthy outcomes.

Moving toward equity is consistent with the broader goal of striving for intersectional justice. Intersectional justice involves a) the process of fostering democratic, participatory, inclusive practices that respect human diversity and affirm our capacity to work together and build coalitions to create change, in order to achieve b) the goal of “full and equitable participation of people from all social identity groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs” (Bell, Citation2016, p. 3). Achieving such a society will necessarily include c) certain conditions: joyful and sustained resistance to and dismantling of systems of hierarchy, violence, and oppression (French et al., Citation2020), equitable and ecologically sustainable distribution of resources, and physical and psychological safety of and respect for all members of society (Bell, Citation2016). In this conceptualization of justice, children from all different backgrounds would be safe and well enough to fully participate in society and get their needs met. If school psychologists adopted equity and intersectional justice as beacons in their work, these goals could be explicitly and continually referred to in order to clarify where and how teams should focus their energy and resources.

A NEW APPROACH

Although efforts to implement tiered prevention models have been growing in recent decades (Horner et al., Citation2017; Spaulding et al., Citation2008), children with certain intersecting identities and backgrounds (e.g., Black children, multilingual Asian and Latinx children from immigrant families, children with disabilities from low-income backgrounds, gender-expansive children in nonaffirming environments) continue to experience increased vulnerability and marginalization that can contribute to greater mental health needs, decreased access to quality mental health care, and worse outcomes (Compton & Shim, Citation2015; Ghandour et al., Citation2019; Kern et al., Citation2020; Locke et al., Citation2017). The failure of school-based mental health professionals to help ameliorate these inequities is embedded in our practices, which are in turn embedded in our training. To date, many school psychology trainers have not explicitly utilized advances in other disciplines (e.g., public health, community and counseling psychology) that would support efforts to disrupt marginalization and promote equity in mental health (Conoley et al., Citation2020; Speight & Vera, Citation2009). Without advancing the field of school psychology toward equity and justice, the field will remain complicit in perpetuating social, health, and academic inequities. As such, a paradigm shift in the training of school psychology, guided by the beacons of equity and intersectional justice, is warranted. This paper proposes a new training framework for school-based mental health to help facilitate this shift.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS FOR A NEW TRAINING FRAMEWORK FOR SCHOOL-BASED MENTAL HEALTH

The proposed training framework is grounded in the theories of intersectionality, critical race theory and DisCrit, SDH, and radical healing. These theoretical bases are described briefly below.

INTERSECTIONALITY

The theory of intersectionality originated in the work of Kimberlé Crenshaw (Citation1989, Citation1991), who explicated how the lived experiences of Black women and women of color were characterized not just by sexism or racism alone but by both forces of oppression, and how feminist and antiracist theory, practice, and scholarship had failed to recognize and act on the ways in which patriarchy, misogyny, and racism are interconnected and interacting. Over time, activists and scholars broadened this scope to encompass other identities and power dynamics and leveraged this framework for social change (Cho et al., Citation2013). The expanded conceptualization of intersectionality enables examination of the combined influence of multiple identities (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, indigenous identity, immigration/generational status, SES) on one’s experiences in the world, and in particular, the ways that multiple systems of oppression act differentially on unique combinations of identities to produce and perpetuate inequities and marginalization (Cho et al., Citation2013).

School psychology has been slow to adopt an explicit lens of intersectionality. Notably, students in PK–12 schools are increasingly diverse along the lines of race, ethnicity, immigration background, and home language (Hussar et al., Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2017), whereas the teacher and school psychology workforces remain predominantly White, female, and monolingual in English (Hussar et al., Citation2020; Walcott & Hyson, Citation2018). Today’s students are also increasingly segregated by race, SES, geography, language, and ability at the within-school, district, and state level—patterns which have emerged out of a long history of intentional educational segregation, community redlining, neoliberal economic policies, shifting patterns of urban/suburban migration, school choice policies, and inconsistent civil rights protections (Gándara & Aldana, Citation2014; National Academies of Sciences et al., Citation2019; Vasquez Heilig & Holme, Citation2013; White et al., Citation2019). As a result, children of color from low-SES or non-English-speaking backgrounds are disproportionately likely to attend more racially/ethnically, socioeconomically, and linguistically homogeneous schools that are under-resourced in terms of personnel, funding, and curriculum (National Academies of Sciences et al., Citation2019). Notably, research consistently finds that segregation is one of the greatest predictors of disparities in academic achievement, and deeply impacts overall wellbeing (e.g., Vasquez Heilig & Holme, Citation2013).

Utilizing an intersectional lens, demographic and experiential differences between student and workforce populations not only reflect the deeply normalized status quo of systemic inequities that pervade social systems, but also suggest that children are likely to face marginalization distinct from that experienced by those who serve them in educational settings. For this very reason, if school psychologists ignore the complexity of student identity, they will mask the heightened vulnerability and potentially compounded oppression of children whose various identities are marginalized within overlapping and interconnected social systems (Cho et al., Citation2013; Cole, Citation2009; McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010). Therefore, acknowledging and acting on intersectionality must be embedded into training and practice, as this lens is prerequisite to equitable provision of school-based mental health services.

CRITICAL RACE THEORY AND DISCRIT

Critical race theory (CRT) is another key theory undergirding the proposed training framework. The emergence of critical race theory during the Civil Rights Era stemmed from a need to illuminate the ways that racism has functioned as the foundation upon which policies and laws have been created and implemented in the United States (Crenshaw, Citation1988; Delgado & Stefancic, Citation2013). CRT centralizes race and its normalized and expansive impact on life, fostering critical consciousness and acknowledging the impact of intersectionality. Over time, CRT has transcended theory and become an interdisciplinary movement toward social change (Solórzano & Yosso, Citation2002).

CRT has also been adapted to reflect the unique historical and lived experiences of various groups beyond the Black–White racial binary. Dis/ability critical race studies, or DisCrit (Annamma et al., Citation2013) offers particular relevance for school psychologists and our proposed framework’s focus on school-based mental health. DisCrit is rooted in an understanding of the history of race and ability as social constructs. In the 19th century, eugenicists began describing racial categories based on phenotypic characteristics and purported genetic inferiorities associated with physical traits (Jackson & Weidman, Citation2005). Within their scientifically baseless hierarchies, race and ability were coconstructed, such that racial groups identified today as non-White and minoritized were “defined by” their intellectual and ability deficits, relative to White Europeans (Jackson & Weidman, Citation2005).

Although disabilities, including mental health disorders, often continue to be described as primarily or even purely biological phenomena, this conceptualization lacks sufficient attention to social context (Annamma et al., Citation2013). That is, identity can shape the manifestation of one’s mental health, as well as how functioning might be perceived by clinicians providing diagnoses—contributing to considerable variability in who is considered “disabled” by their mental health and who is not. Of note, the fact that sociocultural factors contribute to the diagnosis of mental health disorders and disabilities does not disqualify the fact that there are, in some cases, biological bases for differences in behavior and functioning that can be “disabling” in critical life activities—biological, social, cultural, psychological, and political factors all shape what is considered a disability (Anastasiou & Kauffman, Citation2012).

Nevertheless, the coconstruction of race and ability has insidiously pervaded the collective consciousness in the U.S., fabricating a cultural narrative that a “normative” body is White and lacking perceivable physical, mental, or health difficulties, and devaluing the strengths across subgroups of individuals who do not fit this norm (Annamma et al., Citation2013). DisCrit highlights that these norms are fictional, but their implications are not: race and disability both have significant consequences for the lived experiences of those ascribed to their venerated and marginalized categories (Annamma et al., Citation2013). Differences in diagnosis have consequences for how children are perceived, as well as what treatment they receive. For example, Black children with externalizing behaviors are more likely to be diagnosed with Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder and be suspended for disruptive behavior in class, whereas White children with the same externalizing behaviors are more likely be identified as having Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and receive treatment or be sent to a school counselor for class behavior problems (Baglivio et al., Citation2017; Moody, Citation2016; Visser et al., Citation2016).

In education, the racializing of ability has arguably been further compounded by notions of disability embodied in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, Citation2004), which requires the provision of a free, appropriate public education for students within whom a disability can be identified. This framework results in using “proof of intrinsic deficit” as the principal criterion for qualifying a student to receive special education (Harry & Klingner, Citation2007, p. 17). Racially minoritized and bilingual children are disproportionately represented in special education, especially in the more “subjective” disability categories (Artiles et al., Citation2005; Aud et al., Citation2010; Skiba et al., Citation2016). In particular, Black and African American children are consistently overrepresented in the Emotional Disturbance (ED) category, which is often the area of eligibility for children/youth with emotional and behavioral disorders (Aud et al., Citation2010; Bal et al., Citation2019; Sullivan & Bal, Citation2013). Further, racially minoritized children in special education, especially Black children, are more likely to experience segregated special education placements and exclusionary discipline, including being pushed out of schools and into juvenile justice systems (Fisher et al., Citation2020; Skiba et al., Citation2006, Citation2014). Given the sociocultural malleability of mental health and disability, its enmeshment with racially minoritized identity, and the subjectivity of eligibility determinations, it is perhaps unsurprising that students of color are often funneled away from general education or pushed out of schools entirely (Skiba et al., Citation2006, Citation2014). Considering the trauma caused by white supremacy, colonization, misogyny, and ableism, as well as the outsized role of school psychologists in identifying disabilities and services, it is important that school psychologists have tools like CRT and DisCrit to understand systemic oppression.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

A focus on SDH is essential for the proposed shift in training. SDH are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, and work, which profoundly affect health and wellness (Shim et al., Citation2014). These modifiable conditions are situated within the life course (i.e., from the prenatal period through old age) and within nested ecologies (i.e., school, community, country, global; Alegría et al., Citation2018). In lived experience, these ecologies are overlapping and intersecting, such that a child experiences more than one social context that affects their mental health and may have more than one identity that is socially marginalized. This highlights the need to examine mental health outcomes with an intersectional lens, as it will not be possible to “achieve justice in child mental health if we simplify or segment the causes and outcomes of these intersections” (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010, p. 52). Indeed, empirical research bears this out, finding that adolescents with multiple marginalized identities have lower life satisfaction and more psychosomatic symptoms in general, but these effects vary based on context, such as their country’s degree of gender and income equality and immigration policies (Kern et al., Citation2020).

Research has highlighted that societal-level SDMH affect population- and individual-level mental health and wellbeing (i.e., increased risk for mental illnesses and substance use, less access to high-quality mental health care, and worse outcomes) through complex causal pathways (Alegría et al., Citation2018; Compton & Shim, Citation2015; Fagrell Trygg et al., Citation2019; Shim et al., Citation2014). “Upstream” determinants, such as income inequality and employment opportunities, are more distal from the individual and serve as root causes, affecting health through “downstream,” or more proximate, determinants, such as housing conditions or food insecurity (Spencer, Citation2018). These determinants, in turn, impact mental health through psychological and physiological stress responses; epigenetic mechanisms; exposure to injury, pathogens, and toxins; and creation of limitations on access to health, healing, or coping (Compton & Shim, Citation2015). Known SDMH associated with risk of poor mental health include: adverse early life experiences or trauma; poverty, low income, and income inequality; poor housing conditions and housing instability; poor neighborhoods and built environments; food insecurity; low access to/quality of health care; social exclusion or discrimination; low education and educational inequality; and under-/unemployment (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010; Shim et al., Citation2014). As many SDMH are conditions created by social and public policies, it is unsurprising that populations that experience social disadvantage in some form are most affected by mental health difficulties (Alegría et al., Citation2018; Kern et al., Citation2020; McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010). It is also unsurprising that effects can be intergenerational, with cumulative disadvantages appearing to impact health and wellbeing across families (Alegría et al., Citation2018).

It is important to note that a) recognizing the complex emergence of mental health problems and disabilities via SDMH and b) honoring that many people with disabilities affirm their disabled identities with pride, are not mutually exclusive (Andrews et al., Citation2019). Scholars and activists who identify with or study disability culture explain that we can both conceptualize disability as a cultural identity that offers resistance and self-determination and advocate for redistribution of resources and removal of barriers to participation in society to ensure people with disabilities have the greatest opportunities socially, educationally, economically, and politically (Anastasiou & Kauffman, Citation2012; Andrews et al., Citation2019). As both SDMH and services for individuals with disabilities (including access to mental health care) are largely shaped by public policy, it is clear that advancing equitable, culturally and linguistically responsive policy is critical to supporting the civil rights, growth, development, and long-term wellbeing of all individuals, whether or not they self-identify as disabled.

Research on SDMH for Children and Youth

An emerging body of research has begun to document the ways SDMH act on the mental health of children and youth. For example, in countries with greater levels of income inequality, there are larger differences in psychological symptoms and life satisfaction between adolescents from higher and lower SES groups, compared to countries with less income inequality (Dierckens et al., Citation2020). Adolescents living with food insecurity are 4 times more likely to suffer from dysthymia, 2–3 times more likely to report having had thoughts of death or desire to die, and 5 times more likely to have attempted suicide, controlling for race/ethnicity, SES, and other relevant factors (Alaimo et al., Citation2002).

Children growing up in poverty, who are disproportionately children of color and immigrant children, are also likely to face poor living conditions/built environments, community violence, and discrimination, which are also SDMH. For instance, living in poorer housing conditions (e.g., inadequate heating, overcrowding) has been found to be related to higher internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Rollings et al., Citation2017). Police violence in communities of color also takes a substantial toll: there is an inverse relation between personal or vicarious police contact and self-reported health, and that negative association is stronger for Black, Latinx, and other non-White adolescents compared to White adolescents, controlling for prior physical and behavioral health (McFarland et al., Citation2019). Latinx youth and youth with incarcerated fathers are likely to report greater emotional distress during interactions with police, and youth living in neighborhoods with low collective efficacy are more likely to experience PTSD symptoms after police contact (Jackson et al., Citation2019). Further, youth stopped by police at school have significantly higher levels of emotional distress during the interactions and higher social stigma and posttraumatic stress afterward, compared to stops in other locations (Jackson et al., Citation2019).

Discrimination related to race/ethnicity, immigration status, sexual orientation, gender, disability, and other identities is also associated with psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and trauma (Jones et al., Citation2021; Pachter & García Coll, Citation2009; Pascoe & Smart Richman, Citation2009; Vargas et al., Citation2020). Structural discrimination via restrictive immigration policies and heightened immigration enforcement has negatively impacted the wellbeing of many Latinx immigrant communities (Hatzenbuehler et al., Citation2017; Jones et al., Citation2021).; Conversely, reducing threat of deportation for undocumented immigrant mothers by providing DACA status was related to a significant reduction in their children’s diagnoses of adjustment disorder, acute stress disorder, and anxiety disorder (Hainmueller et al., Citation2017). More proximate forms of discrimination and social exclusion also affect immigrant health, including barriers to healthcare for children of immigrants and lower quality care (e.g., Rojas-Flores & Medina Vaughn, Citation2019). These examples do not represent an exhaustive review and are merely some of the known effects of SDMH on children and adolescents. The scale and scope of these effects highlight the urgency of training school psychologists to practice and effect policy change within a SDMH framework.

RADICAL HEALING

The final theoretical lens informing our training framework is radical healing, which emerges out of a long history of scholarly work in Black and liberation psychology and offers a critical response to the concept of trauma-informed care and individual-level interventions predominantly focused on coping. While trauma-informed approaches represent an important step forward, some scholars argue that they are inadequate. First, a trauma-informed lens necessarily entails an explicit focus on a range of negative experiences of children, which can easily enable deficit-based thinking, particularly about groups disproportionately exposed to trauma, including children of color, immigrant children, and LGBTQ children (Ginwright, Citation2018). Second, reduction of trauma symptoms alone does not constitute the presence of wellbeing (Ginwright, Citation2018). Finally, empirical evidence on implementation of trauma-informed interventions in schools remains limited (Temkin et al., Citation2020), and very few models for trauma-informed schools account for the role of oppression in trauma or the reality that schools are often sources and sites of further trauma (Gherardi et al., Citation2020). For instance, experiences of being othered and forced out of schools can be distressing or traumatizing in and of themselves—as well as expose youth to further risks to their wellbeing and agency. By masking these sociopolitical contexts, trauma-informed approaches identify traumatic experiences on an individual basis; therefore, trauma is treated individually (e.g., with cognitive-behavioral interventions), ignoring population-level causes (or social determinants) of trauma and the effects of intergenerational trauma (Gherardi et al., Citation2020).

In contrast, radical healing recognizes that healing from racial trauma and other forms of oppression requires radical action to achieve fundamental social change, as the conditions and systems which harm and traumatize children of color and other marginalized children were never intended to provide wellness and justice for all (French et al., Citation2020). This requires the embrace of a dialectic: acknowledging, addressing, and resisting the oppressive and traumatic conditions that currently cause harm and committing to systematic change that would alter those conditions (French et al., Citation2020). Radical healing is not simply helping each individual to cope with their own symptoms of trauma, but rather, contextualizing those individual symptoms within the broader social context of collective trauma and systems of oppression, and building on strengths and shared identities to promote health, wellbeing, agency, community, and critical action to reduce injustice (French et al., Citation2020; Ginwright, Citation2018). Radical healing extends beyond traditional conceptualizations of what is “clinical” and requires sociopolitical reflection and action (French et al., Citation2020; Ginwright, Citation2018).

French and colleagues (Citation2020) recently articulated a powerful psychological framework for radical healing for communities of color, which integrates: a) fostering critical consciousness and action to create social change, b) building radical hope that allows marginalized communities to imagine and fight for a more equitable, expansive future, c) promoting strength to resist oppression by living joyfully despite it, and working with others to reduce barriers to wellness, d) honoring cultural authenticity and self-knowledge, including recognizing that Western psychology does not represent universal truth nor offer a universal path to wellness, and e) building community and solidarity among coalitions to work collectively toward liberation. This framework, situated within applied counseling psychology, has great relevance to school psychology. Empirical research has documented that children and youth who are engaged as social agents in their own liberation through emancipatory education or activism that reflects their values have better educational outcomes and report greater wellbeing, hopefulness, control, and a healthy sense of identity (Ballard & Ozer, Citation2016; Klar & Kasser, Citation2009; Morsillo & Prilleltensky, Citation2007).

RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN THEORIES

The four theories informing our training framework overlap and help explain how forces of oppression operate on children’s identities/backgrounds and shape their lives, often through public policy, including via access to environments, social circumstances, and resources that either facilitate or hinder health. As oppression is systematically traumatic, marginalized children and families require not only individual healing, but also community healing and strength-building to actively resist and change conditions causing trauma. Existing systems for school-based mental health are not based on radical healing and largely do not attend to intersectionality or SDMH, and these systems have failed to remediate inequities deeply grounded in structural oppression. A new path forward is urgently needed.

AN INTERSECTIONAL SDMH FRAMEWORK FOR HEALING

To create a fundamental and necessary paradigm shift in school-based mental health, a new model for school psychology training—applying an intersectional SDMH framework for healing—is proposed. Built on a foundation of reflective practice, this model consists of three pillars: decentralizing individual psychodiagnostic assessment, centralizing systems-level work, and renewing focus on strengths and healing (see ). The examples and suggestions for training we provide may appear to depart significantly from current training and practice in the field of school psychology; this is intentional, urgent, and necessary to change the status quo among an entire generation of new practitioners. Although this effort will require hard work and substantive change to curricula and practica, we do not believe these steps are out of reach for trainees or trainers. As our current practices are not serving all children equitably, we have no time to wait for those with the most power and privilege to be ready to act in support of, and solidarity with, marginalized children and communities (Gorski, Citation2019). Training programs and trainees must be prepared to become disrupters (Gorski, Citation2019; McClure, Citation2021).

FOUNDATION OF REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

For school psychology training programs to carry out this change, it is imperative that programs cultivate practitioners that are reflective and self-aware. As such, reflective practice is foundational, meaning that reflective practice should be taught explicitly, modeled, and embedded across training experiences. To advance equity, school psychologists need to be able to continuously cultivate cultural humility by understanding their privileges and the ways in which they have been oppressed, as well as identifying, acknowledging, and dismantling the ways in which they are complicit in perpetuating systems of oppression (Hook et al., Citation2016). Reflective practice can help trainees continuously grow in their self-awareness, reflect on how their identities interact with the work they do and the communities they serve, and enhance their capacity to critically evaluate and address inequities (Goforth, Citation2016).

In order to build their introspective abilities and cultivate reflective capacity, students will need time, space, support, and accountability, which will require intentionality and embedding reflective prompts, discussions, assignments, and other activities across coursework and practica experiences. Programs that intend to make this shift also need to support students in their developmental trajectories, which includes helping students reflect on their own identities, cultural narratives, and biases with whatever awareness they currently possess, as well as challenging students to explore new information and perspectives that may feel foreign or uncomfortable. Furthermore, programs need to hold students and faculty accountable when individuals perpetuate identity-blind or deficit-based thinking or marginalize children and families in their interpersonal interactions, practice, or research.

Reflective practice can be enhanced by weekly or monthly program-wide reflective practice groups, reflective circles in applied and theoretical courses, and reflective supervision for practicum experiences, including with both field-based and university supervisors. The integration of reflective practice into both coursework and supervision is needed to afford students opportunities to reflect on how their various roles, decisions, and personal experiences align with the delivery of equitable mental health services, as well as how the knowledge and skills taught in the classroom might facilitate or inhibit equity. Similar to the way training programs teach students to use step-by-step ethical decision-making models, we recommend that programs initially teach reflective practice through explicit models, such as Gibbs’ (Citation1988) reflective cycle or Johns’ (Citation1998) model of structured reflection. Programs may wish to consider the questions in to begin to set the stage for reflective practice.

Table 1. Beginning Questions for Reflective Practice

PILLAR I: DECENTRALIZE INDIVIDUAL PSYCHODIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT

As such a substantial proportion of time in a traditional school psychologist’s role is dedicated to psychodiagnostic assessment activities (Graves et al., Citation2014), there is often limited capacity to develop and use other skills and engage in work aimed at preventing mental health problems. For decades, there has been a call for diversifying and evolving the role of the school psychologist (Larson & Choi, Citation2010), including expanding direct and indirect mental health service provision and systems change (Nastasi, Citation2004). If training continues to perpetuate use of the current inefficient, inequitable model that is primarily focused on psychodiagnostic assessment activities, school psychologists will continue to underutilize their broad skill-set and fail to significantly improve children’s mental health at the population level (Dowdy, Ritchey, et al., Citation2010). Therefore, decentralizing the focus on individual psychodiagnostic assessment activities in training is a necessary prerequisite to be able to amplify training in systems change and healing (i.e., Pillars II and III of this framework).

The strong emphasis on psychodiagnostic assessment activities also implicates school psychologists in the perpetuation of oppressive ideologies and disparities in schools. The individualistic paradigm of traditional psychodiagnostic assessment generally ignores the intersecting identities of the child and associated social contexts that may be affecting their mental health, thus segmenting the potential root causes of mental health (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010) and locating the construct of mental/emotional disability within the child (Harry & Klingner, Citation2007). Special education evaluations in particular rely heavily on norm-referenced assessments that often lack sufficient validity evidence for use with minoritized populations (e.g., Abedi, Citation2006; Cormier et al., Citation2016; Graves et al., Citation2021; Stevanovic et al., Citation2017). For years, school psychologists have publicly owned the limitations of the instruments we use (Ball & Christ, Citation2012; VanDerHeyden, Citation2018), but that has done little to change training and daily practice in the field. Inadequate validity evidence raises serious questions about the use of certain assessments with minoritized populations; yet school psychologists and multidisciplinary teams may still make consequential inferences solely or primarily on the basis of test results, without contextualizing or qualifying the validity of scores based on language proficiency or other identity factors (e.g., Harris et al., Citation2015). In line with a professional culture that places high value on its expert power, school psychologists may not only fail to question whether these data and associated inferences are accurate, but they may firmly perceive results on norm-referenced assessments as “objective” data that are essential for compliance with a data-based decision-making framework (Ball & Christ, Citation2012; Hostetler, Citation2010; Lasater et al., Citation2021; Sabnis et al., Citation2020). In this way, decontextualized use of norm-referenced test results may give school psychologists and teams comfort, providing shelter from the responsibility of weighing the consequences of deeming certain students ineligible for general education.

Overemphasis on or misuse of norm-referenced assessment data may harm marginalized children, including disproportionate representation of racially minoritized and bilingual children in special education (Artiles et al., Citation2005; Sullivan & Bal, Citation2013). The delivery and execution of widespread special education services has been challenging for public schools since the inception of the programming. Today, being made eligible for special education as a student with a disability both affords critical civil rights protections and recruitment of education and health resources that can improve access and agency to meaningfully participate in society and can compound segregation, discrimination, and other adversities for already-marginalized children (Artiles et al., Citation2016; Losen & Welner, Citation2001). For some gender, race, and language subgroups, being identified with an emotional/behavioral disability can entail placement in segregated settings (Skiba et al., Citation2006; White et al., Citation2019), increased risk of experiencing exclusionary discipline (Bal et al., Citation2019; Fisher et al., Citation2020), remaining in special education throughout one’s academic career (SEELS, Citation2005), and worse high school graduation and postsecondary outcomes, compared to peers without disabilities (Hussar et al., Citation2020; Reichard et al., Citation2019).

Taken together, validity concerns about current psychodiagnostic assessment practices and the dual nature of disability highlight the need for intersectional, culturally- and historically-grounded training in equity-centered data-based decision making. This should include teaching culturally and linguistically responsive use and interpretation of standardized, norm-referenced assessments—as well as teaching when other approaches are needed. In order for students to appreciate how special education may benefit or harm differentially across subgroups of children, placements, or the lifespan, training programs should imbue their ethics and assessment coursework with nuanced discussion of the history and complexity of disability (Artiles et al., Citation2016), as well as the strengths, limitations, and risks associated with traditional psychodiagnostic assessment practices. It is important to note that the authors advocate for decentralizing, not eliminating, psychodiagnostic assessment within training programs. As one of many tools, some assessments are helpful in identifying the needs of some children. We also recognize that federal law and state policy continue to heavily emphasize and mandate use of standardized testing and other psychodiagnostic approaches that may be inappropriate or limiting for marginalized children. Trainees and school psychologists can and should advocate for changes to policy that would better support equity in child mental health, while also redistributing training time within the current constraints of legal, ethical, and training requirements. Professional standards hold assessment as a central tenant; however, this does not mean solely the use of norm-referenced instruments.

Decentralizing psychodiagnostic assessment necessitates gaining a deeper understanding of children and their ecologies without relying on their performance in relation to a normative sample. We challenge training programs to expand their emphasis in other areas to move the field toward an equity-minded focus on prevention and healing. Programs can train school psychologists to become comfortable relinquishing the role of expert and “keeper of the scores,” and embrace the role of collaborator, seeking to partner with families and other professionals to understand children in their context. Further, programs can shift towards population-level assessments by providing more training on classroom assessment and culturally and linguistically responsive universal screening (see Bal et al., Citation2014 and Cressey, Citation2019 for examples of CRPBIS models). Programs can also dedicate more time to methods for addressing bias in discipline referrals, exclusionary discipline, and prereferrals processes (Darensbourg et al., Citation2010; Skiba et al., Citation2014; Welsh & Little, Citation2018), so that the next generation of school psychologists can help prevent marginalized children with mental health needs from being excluded, forced out of schools, or inappropriately referred for special education. Training programs may need to help trainees anticipate resistance to changes in the school psychologist’s role. It may be helpful for students to practice explaining to administrators why shifting resources away from psychodiagnostic assessment activities can be valuable for promoting equity in school-based mental health and preventing educational inequities.

PILLAR II: CENTRALIZE SYSTEMS-LEVEL WORK

Complementing a decreased focus on psychodiagnostic assessment, we propose increasing and centralizing school psychology training in systems-level work. As children’s mental health inequities largely emerge out of social contexts and public policies (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010)—including school policies (Huang et al., Citation2013)—school psychologists need to be able to serve individual children by identifying SDMH factors that are hindering their wellbeing and focus efforts at population-level prevention, where the impact of their intervention will be greatest (Shim et al., Citation2014). Training school psychologists to engage in systems-level work encompasses teaching a range of practices that target populations and intervene at multiple levels within the school and community infrastructure (Dowdy, Ritchey, et al., Citation2010). In this way, the next generation of school psychologists will not only be able to impact more children and families through indirect service provision, but also prevent mental health problems and promote health and wellness among marginalized children. Additionally, when engaging in systems-level work, it will be essential to remain oriented toward prevention and early intervention by focusing on equity and quality in early childhood education and mental health services, which have been found to significantly ameliorate SDMH in children (AAP Council on Community Pediatrics, Citation2016; Moore et al., Citation2015; see California’s equity-focused master plan for early learning and care). Systems-level work can take many forms; we propose at least three primary training areas.

MTSS

One step towards emphasizing systems-level work is to train students to work within current MTSS models, with the goal of directing additional time and resources to universal/Tier 1 activities. MTSS attempt to utilize a population-focused approach to address the mental health of the entire population (Doll & Cummings, Citation2008) by directing plentiful resources to all students as part of universal/Tier 1 activities. Tier 1 supports are essential, as schools with unmet needs at Tier 1 are likely to have significant challenges with equitable and efficient implementation at Tiers 2 and 3 (von der Embse et al., Citation2019). Tier 1 supports entail school-wide practices that promote healthy climate and wellness among all children—provided to all children, without pathologizing children through special education identification. As these supports are provided universally, resources that foster wellness reach children whose mental health needs may be subclinical. For example, social–emotional learning curricula that teach social justice and culturally-grounded social competencies, such as engaged and critical citizenship, can be delivered to all children as part of regular educational programming (Jagers et al., Citation2019). Specifically, a transformative approach to SEL has been proposed to promote educational equity and provide opportunity for students to critically examine and challenge inequities (Jagers et al., Citation2019). School psychologists need to be trained in inclusive and racially just teaching practices and effective culturally responsive universal positive behavioral interventions and social–emotional instruction.

During practica in districts where MTSS is already being implemented, school psychology trainees would benefit from participation on MTSS teams and practice raising questions related to Tier 1 implementation (e.g., Are supports fairly distributed to all schools within our district? Are there any subgroups of students or parents who are not able to easily access universal supports? Are Tier 1 services being provided in a culturally responsive manner?) and advocate for improving existing practices or allocating more resources at Tier 1. If students are placed in districts that do not utilize MTSS, students would benefit from training on how to utilize consultation and advocacy skills to engage in conversations with school leaders about the value of universal supports to ensure equitable services for all. As school psychologists often serve as professional development trainers and intervention coaches within MTSS (Eagle et al., Citation2015), practicum students need adequate training on how to provide PD on effective Tier 1, universal supports for meeting the needs of marginalized students. Reflection on these experiences should be elicited during practicum supervision, as well as discussion of how their practicum sites could work to establish or improve equitable implementation of MTSS, especially at Tier 1.

In support of the lofty goal of equitable implementation of MTSS, it is essential to acknowledge there are significant difficulties with MTSS implementation. As such, it is critical to examine implementation factors that may interfere with, or facilitate, successful adoption of MTSS. It is important to recognize that implementation will be enhanced with: effective leadership; clarity on how to use data to inform decision-making; involvement of key stakeholders; the selection of interventions based on empirical evidence and fit with local setting; skill-based training for implementers; a supportive organizational structure, and facilitation from external systems (Forman & Crystal, Citation2015). Additionally, each of these implementation factors need explicit attention to issues surrounding equity, such as ensuring adequate representation of key stakeholders. Training in implementation science, including an examination of methods that may enhance uptake of MTSS and other systems interventions, is essential to address the research-to-practice gap in school psychology (Sanetti & Collier-Meek, Citation2019).

Systems-Level Consultation

Centralizing systems-level work will be enhanced by expanding and deepening training on systems-level consultation, as well. By consulting with other professionals to effect change at the systems level, school psychologists can be leaders in developing initiatives to address SDMH and build capacity at the school level to sustain these efforts. For instance, if MTSS is not already being implemented within their schools, school psychologists can advocate for developing the model and offering a full continuum of services to promote mental health within their setting, justifying to administrators the need for this model in order to begin to address mental health and academic inequities and explaining the relatively low cost of implementing MTSS, especially compared to costs associated with suspensions and dropout (Lindstrom Johnson et al., Citation2020). School psychologists can advocate for creating a social–emotional/behavioral model concurrently with an academic model and continuously re-center equity and intersectional justice in conversations regarding resource allocation and implementation decisions. Training programs can explicitly teach consultation skills to identify and investigate inequities at the school or district level (Sullivan et al., Citation2015), as well as train students on how to mitigate power imbalances (Woods-Jaeger et al., Citation2020).

Trainees should learn how systems-level consultation can be leveraged to implement novel approaches, especially if working in districts or states with already well-established MTSS models. One such novel approach involves broadening the application of universal screening within MTSS to screen the strengths and health of the larger contexts in which students live. Conducting universal screening for mental health at the population level allows examination of what health problems the school community faces and monitoring of the mental health status of a population to determine the “portrait of the collective mental health of all students enrolled in a school or district” (Doll & Cummings, Citation2008, p. 1333). Instead of using data to solely to identify individuals who are “at risk” and as a result provide them with early intervention services, data could instead be analyzed to evaluate the mental health of the broader, school-based population (Dowdy, Ritchey, et al., Citation2010). For example, school-level data collected through surveys such as the Center for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System or the California Healthy Kids Survey (see https://calschls.org/) can be used to examine symptoms of depression or behavioral risk indicators across a school population. In this way, existing anonymous data may be used to help inform the service delivery needs; the resulting services would include systems-level interventions informed by data aggregated from the whole school population.

School psychologists could also further advocate for expanding universal screening to include the screening and monitoring of neighborhood- and community-level health and factors that may inform universal prevention and intervention strategies. For example, measuring some of the known SDMH within a community, including income, education, employment, and housing quality (see Rural Health Information Hub’s SDH assessment tools and resources), may inform what services are most needed within a community. Partnering with community organizations that already assess for certain SDMH may provide useful information to schools that are serving these communities. It may be beneficial to partner with community health providers to help meet the American Academy of Pediatrics’ recommendation to screen for SDH at every well-child visit from birth until age 21 (AP Council on Community Pediatrics, Citation2016; see Hunt, Citation2021 for example screening measure).

Explicitly examining proximate and distal SDMH that affect the student population may provide needed information on the community’s needs and resources, as well as ideal targets for healing-centered care within the school setting. Focusing on school, neighborhood, and community strengths and resilience-promoting factors may help to diminish the stigma that is often associated with mental health problems while also assessing constructs for which schools are better prepared to address (Dowdy et al., Citation2010). In particular, examining indicators of personal strengths and wellbeing (e.g., coping skills; strong relationships with parents, teachers, and peers; life satisfaction; happiness; perceived social support; optimism; gratitude) can help educators monitor for the presence of resilience factors (Romero et al., Citation2020; see also www.project-covitality.info). However, additional development of measures to assess both SDMH and for culturally-specific strengths (e.g., familismo in Latinx communities) is needed.

There are numerous other ways in which school psychology training programs can discuss and prepare students for using systems-level consultation for a myriad of issues (e.g., home–school partnership practices, language instruction and supports for multilingual children, unmet needs of the LGBTQ + student population). School psychology trainers should model consultative skills within their own programs (e.g., Chittooran, Citation2020; Grapin, Citation2017) and give students opportunities to practice engaging in roleplays and assignments related to systems-level consultation within courses. It is important to provide training on strategies for collaborating with administrators and engaging in systems-level change (Eagle et al., Citation2015). Implementation strategies should explicitly target how to evaluate readiness for change and what to do when encountering resistance. As educators’ resistance to more culturally responsive services in schools may be conceptualized as a multilevel learning problem (Neri et al., Citation2019), trainers can help students identify specific learning needs that may prevent willingness or ability to engage in systems-level consultation. Neri and colleagues (2019) offer ways to anticipate and address resistance to culturally relevant pedagogy that could be adapted for resistance to healing-focused services.

Advocacy and Policy Work

Another primary area for training in systems-level work involves teaching future school psychologists to engage with advocacy and policy. Many SDMH emerge from public policy, including policies that impact school funding and operation. Therefore, bolstering equity-centered prevention work necessarily involves advocating for policies that protect and promote the wellbeing of children and families (Shim & Compton, Citation2018). Countries that have prioritized addressing SDH through child-centered policy have seen improved health outcomes (Shim et al., Citation2014). Given what is known about SDMH and coconstruction of race and disability, children’s mental health needs do not begin or end at the school doors, and factors external to school will play a substantial role in children’s ability to flourish and find wellness and academic success. Therefore, school psychologists cannot remain neutral on issues of policy and should be trained to engage with policy in school and health systems and at local, state, and federal levels (Shim et al., Citation2014).

School policies may be an easy entry point to advocacy and policy work for school psychologists. School contexts are themselves a SDH; in particular, the physical and structural environment, school composition and climate, and health policies, programs, and resources (Huang et al., Citation2013). Working with school-based teams, administrators, professional organizations, or as private citizens, school psychologists can advocate for schools and districts to adopt policies that have evidence for reducing disparities and promoting health—for instance, advocating for eliminating exclusionary discipline policies, which are directly linked to later poor health, education, and justice-involvement outcomes (Skiba et al., Citation2014), and implementing restorative justice approaches (González, Citation2015). School psychologists can also take an active role in promoting teachers’ and school staff’s awareness and understanding about equity and intersectional justice. Advocacy may take other forms as well, including advocating for program evaluation of existing policies to assess equitable implementation or collaborating with other professionals to develop new school–community partnerships to reduce inequalities or propose funding reallocation to schools with greater negative SDMH (Huang et al., Citation2013; Nastasi et al., Citation2004).

School psychologists should also be prepared to advocate for broader social policies that deeply shape the health and wellbeing of children and families. For instance, poverty is one of the greatest predictors of health outcomes (McPherson & McGibbon, Citation2010). Policies are needed that address poverty and income inequality, such as providing living wages and the earned income tax credit—which are associated with increased achievement and educational attainment, and decreased incidence of young parenthood (Bhatia & Katz, Citation2001; Dahl & Lochner, Citation2012). Other policies that could profoundly support children’s development and mental health include expansion of housing assistance policies, funding for LGBTQ-specific systems of care, and increased access to high-quality early care and education programs (ECE), which are all associated with improved child mental health outcomes (Fenelon et al., Citation2018; Manning et al., Citation2010; Painter et al., Citation2018). Numerous other policies affect the SDMH of children and merit the attention, advocacy, and action of school psychologists. At the state and federal level, school psychologists can work with professional associations or other groups to organize, release position statements, propose policy changes and circulate to other stakeholders, submit public comments on proposed rule changes, and communicate with school boards and state and federal legislators. Graduate programs need to provide training on organizational and systems theories (Sullivan et al., Citation2015) and the process of policy and legislative change, and involve trainees in drafting policy statements and supporting other advocacy efforts (Woods-Jaeger et al., Citation2020).

PILLAR III: RENEW FOCUS ON STRENGTHS AND HEALING

Finally, shifting services away from a problem-focused approach that privileges Western, individualistic, and coping-based services is necessary to center equity and intersectional justice in school-based mental health. French and colleagues (2020) posit that a shift to radical healing, rather than continuing to focus on coping, is fundamental for the wellbeing of people of color, as “centering healing allows for an intentional proactive consideration of the relationship between justice and wellness” (p. 19). A shift toward radical healing thus necessitates not only managing symptoms of distress caused by historical and ongoing racial trauma, as well as other trauma caused by systems of oppression, but also resisting and working to change the SDMH and systems that have caused distress. For marginalized children and youth whose distress is often pathologized, healing from the legacy of historical harms and ongoing oppression involves a culturally responsive, collectivist approach. A renewed focus on strengths and healing is imperative in pursuing mental health equity and intersectional justice.

Training programs need to prepare school psychologists to utilize a strengths-based and healing-centered approach to providing mental health services within schools. This training should be built on foundational coursework in Black psychology, liberation psychology, positive psychology models, radical healing, and culturally responsive practices for supporting students and families (e.g., Clonan et al., Citation2004; Cole, Citation2009; Crenshaw, Citation1989, Citation1991; Fanon, Citation1963, Citation1967; Freire, Citation1970; French et al., Citation2020; Ginwright, Citation2018; Goforth, Citation2016; Martín-Baró, Citation1994; Prilleltensky, Citation1997; Worrell et al., Citation2001). Part of radical healing is rooting out ideologies of power, violence, and hierarchy within ourselves as people and professionals and within our practices, policies, schools, communities, and systems; this requires critical self-reflection and action. In practicum courses, students must grow in their awareness of the ways in which deficit-based approaches commonly manifest in schools and gain skills to analyze and promote students’, families’, and schools’ strengths and needs. In a parallel process, trainers should model focusing on the strengths of students, clients, communities, school, and staff during supervision.

As the field is still largely White, trainees may also need to expand their conceptualization of strengths beyond those rooted in White and capitalistic values to encompass culturally-congruent strengths. For example, students whose own values include individualism, independence, personal achievement, or high educational attainment and occupational status may need exposure to other strengths and values, such as joy, strong social relationships, interdependence, problem-solving, resourcefulness, resilience, persistence, responsibility, loyalty, respect, pragmatism, creativity, and storytelling. Graduate students can leverage their broadened conceptualizations of strengths in efforts to strengthen school-wide practices to support healing, as well as inform more targeted mental health interventions within culturally responsive implementation of MTSS or through school–community mental health partnerships.

Programs might teach trainees how to learn about the communities they are serving, while remaining culturally humble in their understanding (e.g., remaining curious, recognizing one’s preconceived notions and biases, using active listening). Additionally, programs may wish to provide training on how to conduct complete mental health universal screening as part of MTSS. As opposed to traditional screening approaches focused on identifying mental health problems, complete mental health screening incorporates information on student wellbeing and strengths in addition to indicators of distress (Dowdy et al., Citation2010). Examining factors known to enhance resilience, such as hope and gratitude, may help provide children with resources to thrive in current educational systems.

Further, programs could challenge trainees to broaden beyond the student population to include screening community mental health, as well. Historically, there have not been methods for systematically evaluating the SDMH of children (Alegría et al., Citation2018), nor has the field of school psychology traditionally taken a holistic approach to screening students for mental health and wellness (Dowdy et al., Citation2010). Thus, prior to assessing individual and community strengths and needs, it is important to forge partnerships with community members and organizations in order to grasp their own conceptualizations of strengths, healing, and factors that contribute to positive, stable family functioning. This could help guide meaningful and culturally responsive assessment of community strengths and needs, as well as lay the foundation for new school–community mental health initiatives to promote equity in mental health (e.g., school–provider referral pathways, systems of care; Nastasi et al., Citation2004).

Training students to engage in healing-centered intervention will involve helping them cultivate a broad set of intervention tools for culturally responsive practice. For faculty, this may require making changes to intervention coursework to ensure a pluralistic approach (e.g., Cooper & McLeod, Citation2011). Intervention techniques should not solely rely on cognitive-behavioral theoretical orientations, as these approaches are highly individualistic and coping-focused. Other avenues for training might involve helping students utilize their clinical/consultative skills to help teachers enact healing pedagogies or assist parents in building capacity to advocate for their communities’ wellbeing.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Transforming our school psychology training programs to prepare the next generation to implement changes to practice once they enter the field is only one of many steps for advancing equity and justice in schools. In order to facilitate larger changes in child mental health, a steadfast, profession-wide commitment to equity and intersectional justice is required, and accountability to enacting those values is necessary. NASP and APA need to hold programs accountable through accreditation and training standards. The training standards themselves do not necessarily need to change; however, interpretation of standards may need to expand to allow for robust shifts in training to promote equity. NASP, APA, and other accrediting bodies are encouraged to increase flexibility for programs to use alternative methods for meeting competencies in a manner more aligned with equitable mental health practices. Collaboration among programs can also enable more concerted moves toward equity.

School psychologists’ willingness for their training and role to evolve in this way may also need to be examined. Are school psychologists ready to advocate for equity and intersectional justice? Resistance to change may be strong, given limited resources, competing training interests, and entrenched white supremacist, classist, and ableist ideologies. We call on national and global leaders in the field to take up conversations related to mental health equity, accountability and accreditation, financial affiliations with test publishers, and professional will, and then act dynamically—in concert with practitioners and researchers— to make bold policy changes that advance equity in school-based mental health practice and training.