Abstract

It is imperative that the field of school psychology in the United States continue to evolve in order to support the development, well-being, and educational success of all students. The confluence of numerous factors, including the sociopolitical zeitgeist, significant societal events, and the need to provide appropriate supports for students from minoritized backgrounds, converge to reveal and inform the importance of the field of school psychology continuing to develop. This special topic section of School Psychology Review focuses on reconceptualizing school psychology for the 21st century. The compilation of articles featured herein is both introspective and forward looking. These articles present important theories, frameworks, and approaches to improve school psychology’s responsiveness to the social injustice embedded in many of the core foundations of American society and inform our professional efforts to more effectively support every student. Several foundational orientations are emphasized, including critical consciousness, critical reflexivity, and other mindsets key to engaging in sustained efforts to advance social justice and antiracism. Implications for practice, scholarship, graduate education, and professional standards in school psychology are discussed.

Impact Statement

Sociopolitical and cultural changes have affected the lived experiences and needs of students, families, and educators, which, in turn, create the contexts within which school psychologists engage and affect the attitudes, assumptions, behaviors, and resources school psychologists bring to their work. This article highlights considerations and opportunities for school psychology faculty, practitioners, and students to advance the development of the field to support the students, families, and communities we serve.

School psychology is a field characterized by both ongoing change and stubborn constants, even where reform has long been championed (e.g., Gutkin & Conoley, Citation1990). The year 2020 brought, for multiple reasons, an inclination to reflect on the field’s progress, challenges, and potential futures. We are not alone in contemplating school psychology’s impact and evolution—and limitations thereof—or envisioning potential pathways forward (e.g., Conoley et al., Citation2020; Jimerson, Citation2020; Jimerson et al., Citation2021; Worrell et al., Citation2020). This special topic section aims to further advance the 2000 School Psychology Review (SPR) mini-series, “School Psychology in the 21st Century” (Fagan & Sheridan, Citation2000), as we distributed an open call for papers, inviting colleagues throughout the field to envision the next frontiers of school psychology in our rapidly changing cultural, social, and political contexts. The resulting compilation of articles is both introspective and forward looking, offering theories, frameworks, and approaches to improve school psychology’s responsiveness to the social injustice embedded in many of the core foundations of American society, and to support every student more effectively. Herein, we reflect on the 2000 SPR miniseries and consider the implications of major sociopolitical and cultural changes that warrant further emphasis. We also introduce the articles featured in this special topic section, Reconceptualizing School Psychology for the 21st Century: The Future of School Psychology in the United States.

The 2000 SPR Mini-Series, School Psychology in the 21st Century

In 2000, SPR featured a mini-series in which several esteemed scholars and leaders in school psychology offered their perspectives and commentaries “to describe the present and offer directions and predictions for the future of our field” (Fagan & Sheridan, Citation2000, p. 483). Key articles addressed the status of the field in the United States (Reschly, Citation2000); proposed a paradigm in the 21st century (Sheridan & Gutkin, Citation2000); provided a framework for school psychologists as healthcare providers (Nastasi, Citation2000); articulated the instructional perspective emphasizing early intervention and prevention (Shapiro, Citation2000); explored challenges and opportunities in graduate education (Swerdlik & French, Citation2000); postulated critical research agendas for the future (Kratochwill & Stoiber, Citation2000); and described the professional organizational landscape of school psychology (Fagan et al., Citation2000). Among the 18 articles in the 2000 mini-series, several of these works emerged among the most highly cited in the field by 2010 (Liu & Oakland, Citation2016; Price et al., Citation2011).

In advocating for an ecological orientation (Sheridan & Gutkin, Citation2000), systemic roles and consultation (Shapiro, Citation2000), and a comprehensive health focus and continua of services (Nastasi, Citation2000), many of the recommendations for advancing school psychology have become ingrained in the common parlance and practice in the field of school psychology. Indeed, the field has been described as having ecological and public health movements in the interim since the mini-series (Song et al., Citation2019). Bolstered by federal policy language, curriculum-based measurement and behavioral intervention and assessment have gained prominence as predicted (Reschly, Citation2000). However, consensus among stakeholders and changes to graduate program curriculum and practice have been more limited. Evidence-based practice—now embedded within professional standards and national policy—and implementation science, too, are widely invoked (Sanetti & Collier-Meek, Citation2019), yet intervention research remains relatively limited (Villarreal & Umaña, Citation2017), and use of discredited and unproven practices remains commonplace (Shaw, Citation2021).

Despite leaders’ visions for the 21st century, special education evaluation and assessment related activities continue to be the primary functions of most school psychologists, though a substantial and increasing proportion of school psychologists are also involved in consultation, mental health services, and behavioral supports (Farmer et al., Citation2021). Although traditional roles and activities still comprise the majority of many school psychologists’ time (Farmer et al., Citation2021), the paradigm shift espoused in the 2000 SPR mini-series has featured heavily in leadership, scholarship, and practice throughout the last 20 years (e.g., Conoley et al., Citation2020; NASP, Citation2020). Yet many have decried the minimal change in the field; as Conoley et al. (Citation2020) noted, “It is a troubling paradox that a self-proclaimed field of scientist–practitioners cannot use its own research to revolutionize school psychology practice in the service of student and educator well-being” (p. 372). This is a different paradox than typically discussed—that is, that the paradox of school psychology is that “to serve children effectively school psychologists must, first and foremost, concentrate their attention and professional expertise on adults” (Gutkin & Conoley, Citation1990, p. 212)—and suggests that the adults we may need most to focus on are school psychologists, that we need to turn our analysis inward and leverage advances in belief, attitude, and behavior change within our professional community, as noted elsewhere (e.g., Shaw, Citation2021).

As predicted, women comprise a growing share of the field and the need for bilingual school psychologists has grown (Reschly, Citation2000), but there has been relatively little change in the demographics of the field compared to the student population we serve (Goforth et al., Citation2021). It is worth highlighting that all 23 authors of the 18 articles in the 2000 SPR mini-series appear to be White, and most (15) are men, despite the longstanding preponderance of women in the field. More importantly, few of the contributors to the mini-series substantively engaged issues of diversity in their 2000 articles. A noteworthy exception was Nastasi (Citation2000) who emphasized the need for cultural specificity, a more expansive conceptualization of diversity, attention to social ecology, and cultural competence that included reflexivity. Her attention to these topics and nuance of her discussion were unique among the articles in the mini-series, perhaps signaling broader oversights of considerations of culture, diversity, and context despite promotion of an ecological lens given the dominance of normative perspectives of development, education, and health within the field.

Taken together, this is not to minimize or disregard the changes that have happened at multiple levels, from the individual school psychologists who embody the role of systems change agents or the changes to service delivery models, program curricula, and policy at various local contexts (e.g., individual school buildings, districts, graduate programs, states, professional associations), but rather to call attention to the limited change in the aggregate, especially in light of advocacy from within the field and the ecological context of school psychology. Indeed, such examples serve as reminders of the potential for change and the possibility imbued in visions of change—that the transformations envisioned can be achieved.

The Shifting Sociocultural Context

This special topic invited consideration of how school psychology can be more responsive to the current sociocultural context as a key foundation for envisioning the future of the field. Note that we focus on developments within the United States, as each of the 2000 mini-series contributors were scholars and practitioners in the United States, as are those of this special topic. Our intent is not to be dismissive of the global context of school psychology or developments happening in and relevant to school psychology in other regions of the world (Jimerson et al., Citation2007), or to minimize the importance of transnational considerations in the development of school psychology internationally (Hatzichristou, Citation2002; Oakland & Hatzichristou, Citation2014). Instead, we aim to be explicit about the contexts addressed by the authors in this special topic and its precursor, acknowledging the limitations and applicability of this scholarly endeavor.

In the years following SPR’s 2000 mini-series, numerous significant events and developments have continued to shape the United States society and schools, and in turn, the sociopolitical zeitgeist and ecological context of school psychology. These have included, but are not limited to the September 11, 2001 attacks and the resulting changes to security policy and perceptions thereof in public spaces, including schools; multiple wars involving the United States; recessions and housing crises; rise of the gig economy; increasing income and racial inequality; proliferation of gun violence throughout communities in the United States, including schools; growing effects of climate change and weather-related disasters, such as devastating storms, fires, heatwaves, and floods; technological advances that increasingly shape human behavior, relationships, and health (e.g., mobile devices and smart phones, genome sequencing, Google, social media to name a few); increasing privatization of everything from public services to space; the expansion of and recent attempts to retract LGBTQ rights; demographic shifts in which the young of the United States population is majority nonwhite; increasing political divisiveness and unrest; rising mental health needs among young people; rising xenophobia and White-identity politics; rise of reality TV and the influencer economy; increasing misinformation, disinformation, post-truth, and antiintellectualism; growth of the knowledge based economy and proprietary technology; commercialization; venture capitalists’ interest in mental health and schooling; and globalization (e.g., Pennington, Citation2019; Schaeffer, Citation2019).

Simply put, there have been numerous influential events and shifts in social dynamics since the SPR 2000 mini-series. These sociopolitical and cultural changes have affected the lived experiences and needs of students, families, and educators, which, in turn, create the contexts within which school psychologists engage and affect the attitudes, assumptions, behaviors, and resources school psychologists bring to their work. Furthermore, they affect how school psychologists operate within our professional community and relate to our professional organizations, as well as the operations of professional organizations themselves.

Beyond the above chrono- and macrosystemic societal forces, psychology, too, has undergone notable developments such as the rise of interdisciplinarity, team science (e.g., Cacioppo, Citation2013), attention to the replication crisis, big data and data science; concern for accountability, leading to greater regulation, monitoring, ostensible transparency to public, and open access and open science movements; internal and external critique of White, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) samples and the implications for our science (Henrich et al., Citation2010); and reliance on social media for a range of professional activities along with the concomitant emergence of edu-celebrities and mental health influencers. Rozensky et al. (Citation2017) summarized the developments in psychology education to include increasing focus on accountability and reliance on competency based metrics; increased interest and enrollment in psychology undergraduate and graduate programs; ongoing internship imbalances; formalization of regulations and professional guidelines regarding various features of preparation for and engagement in health service psychology; and increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion in psychology.

Yet difficulty recruiting, retaining, and elevating individuals from systematically excluded backgrounds remains (Blake et al., Citation2016). Not only must their presence be welcomed, but they must also be supported and appropriately recognized for their contributions (for discussions of culturally responsive, antiracist recruitment and retention approaches, see, for example, Grapin et al., Citation2015; Proctor, Citation2022). This is true in both practice and scholarship, where, in the latter, minoritized scholars are more likely to innovate but less likely to have their work recognized (Hofstra et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, though school psychology research increasingly includes at least some inclusion of individuals from minoritized groups (Schanding et al., Citation2021), very rarely has it also included culturally responsive approaches or acknowledged the roles of systemic racism, white supremacy, or colonialism (Grant et al., Citation2022). Mere representation is not enough; instead it is the context of such representation that matters. This context is determined by the assumptions, beliefs, and ideology underlying the scholarship, selection of constructs, researchers’ relations to their participants, and the potential effects—positive, benign, or harmful—on communities studied (for in depth discussion of these issues, see Arora et al., Citation2022; Grapin & Fallon, Citation2022; Sabnis & Newman, Citation2022).

Other persistent issues in school psychology, noted at the turn of the century and well before, include the interrelated tensions between research and practice, shortages of both practitioners and faculty, marginalization of racially minoritized school psychologists and their contributions, and the ongoing need to diversify the field. This need to diversify has been met with varied efforts, often spearheaded by Black, Indigenous, and other people of color in the field, to expand the pipeline to graduate school (e.g., the NASP African American subcommittee’s Exposure Project; Blake et al., Citation2016; Goforth et al., Citation2016; Graves & Wright, Citation2009), better understand the nature of minoritized individuals’ experiences within the field (e.g., Proctor et al., Citation2018; Proctor & Truscott, Citation2012), and improve the experience of minoritized graduate students entering and progressing through school psychology programs (Grapin et al., Citation2015). Both research-based recruitment and retention practices and addressing the exclusionary roles of racism within the field to develop antiracist scholarship and practice are increasingly emphasized (Proctor, Citation2022).

Against this backdrop, in late 2019 and early 2020, we conceptualized the current special topic to invite scholars to envision the next frontier of school psychology in our rapidly changing cultural, social, and political contexts as a follow up to the 2000 mini-series.Footnote1 Yet, these contexts would shift more rapidly than we could have ever imagined from the point of inception to writing of this introduction. By the end of March 2020, many parts of the world were under lockdown mandates to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus-19 (COVID-19). By the end of May 2020, tens of millions of people in the United States and around the world engaged in mass protests of racial injustice following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police and the deaths of numerous other unarmed Black men, women, and children by police in the United States (Buchanan et al., Citation2020).

Then, in early January 2021, the world witnessed an insurrection at the United States Capitol, as supporters of the outgoing president attempted a coup to prevent the inauguration of the new one. Essential workers and supply chains would become household phrases as the ongoing waves of more infectious COVID-19 variants caused continued mass infection and mortality, and destabilized systems and communities. Twenty years after September 11, the world watched the Taliban return to power in Afghanistan, and the subsequent humanitarian crisis as Americans and Afghans attempted to flee the country. The year also brought record breaking climate disasters (e.g., Australian floods, South-Central United States freeze and Western United States wildfires, devastating tropical storms and hurricanes in Central America, Southeast Asia, and the United States), as historic weather catastrophes have become commonplace due to largely unmitigated climate change. Throughout 2021, mass COVID-19 infections continued alongside vaccine inequity and controversy related to the disinformation surrounding the virus and treatments, and as a consequence, more infectious variants emerged and drove subsequent waves of infection, death, and destabilization. Since 2000, SPR has continued to feature information pertaining to the impacts of COVID-19 on students, parents, teachers, and the provision of school psychology support services (more than 15 articles, see Song et al., Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022).

By fall 2022 (and the initial writing of this article), United States citizens have experienced disenfranchisement of voting rights, LGBTQ rights, trans rights, reproductive rights, Indigenous sovereignty, and climate justice at the state and federal levels. This constriction of human and environmental justice was punctuated with a wave of Supreme Court decisions unsettling case law on which decades of civil rights advancements were based, perhaps most visibly in the overturning of 1973s Roe vs. Wade in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022). Increasingly widespread efforts by state and local governments and school boards to promote censorship and restrict student, family, and teacher rights related to race, gender, and sexuality complicate the work of educators, mental health professionals, and justice advocates, including school psychologists. Mass covid infections continue with more than 1.06 million deaths officially attributed to the virus by October 2022 (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Citation2022). However, state and federal mandates to mitigate spread have largely been discontinued as ongoing infection and mortality have been normalized in state and federal responses. The ongoing stressors of COVID-19 despite dwindling protections and resources, along with the increasingly frequent politicization of schools as a site of censorship and exclusion (e.g., of trans youth), are taxing educators and school systems already spread thin.

In the interim, the members and leadership of the field of school psychology have experienced several monumental shifts and groundbreaking actions, including a rapid transition to widespread remote practice and graduate education to mitigate COVID-19, several unified statements against racism (e.g., García-Vázquez et al., Citation2020; Truong et al., Citation2021), and an apology from the American Psychological Association (Citation2021) for its role in systemic racism. Indeed, systemic racism, antiracism, and social justice are now common vernacular in the field and the various statements and apologies call for bold acknowledgements, reflection, and actions at multiple levels to disrupt systemic racism and its manifestations in professional spheres (e.g., Jimerson et al., Citation2021; Sullivan, Citation2021; Worrell, Citation2022). At the same time, these concepts are subject to widespread professional and public controversy in state and local politics, school boards, and classrooms as critical race theory and all manner of terms related to diversity, equity, and justice have been villainized in right leaning politics (e.g., Crenshaw, Citation2021), spurring resistance and advocacy from individual practitioners and other professional groups (e.g., NASP, Citation2021). It is fair to say that few of these contexts in or out of our field could have been envisioned at the time of the 2000 mini-series. This sets the stage for the contemporary collection of articles herein.

OVERVIEW OF ARTICLES FEATURED

We intended this special topic section to feature a greater diversity of voices on the future of school psychology, including critical reflection on the current and future cultural, social, and political contexts that shape school psychology practice, graduate education, and research. We issued an open call and capitalized on SPR’s triple-anonymous review process to broaden the potential perspectives represented. Where the precursor featured the senior leaders of the scholarship, practice, graduate education, and professional associations, most of whom have since retired, this special topic presents perspectives from a range of early career, midcareer, and senior scholars from a mix of institutions in the United States and professional and personal backgrounds. Of the 11 articles included in this special topic section, representing 30 authors, 9 articles were (co)authored by women and 6 by racially minoritized scholars. Given that the School Psychology Review journal includes a triple-anonymous peer review (e.g., names of the action editors, editorial board members, and authors are not available in the review process), the notable increase in diverse representation is likely a result of the repeated open call for papers, the contemporary context, and the ongoing increase in diversity among faculty, practitioners, and students in school psychology. As the editors of this special topic section, we are midcareer and senior scholars in three research intensive universities and leaders of our respective school psychology programs, as well as holding or having held a myriad of leadership positions in psychology, education, and school psychology. Our scholarship and other professional activities span a range of topics in school psychology and have been nurtured through partnerships in a range of local, national, and international contexts. Our varied personal experiences and tenures in the field of school psychology lend differing relations to the sociocultural and chronosystemic factors discussed above. As such, our perspectives are necessarily informed and bounded by both our diverse personal and professional experiences, statuses, values, and aspirations, as are the perspectives of the contributors to this special topic section.

Through repeated open calls for submissions, we encouraged authors to explore theories, conceptual frameworks, or paradigms to guide future school psychology graduate education, research, and practice in contemporary and prospective contexts; address issues related to diversification across all aspects of the field; the role of science and attitudes thereof for practice and public engagement; and predict implications of the current and projected cultural or sociopolitical contexts for current and future roles, opportunities, and challenges for school psychologists. All manner of scholarship was welcomed, from data-based commentaries and conceptual papers, to any manner of empirical investigation. We asked that all authors explicitly link projections and recommendations to research on current and future cultural, social, and political contexts. The result of this process is a set of 11 articles (including this one) exploring the field’s theoretical, conceptual, scholarly, and practical dimensions of the field, and the intersections thereof.

Orienting the Field for Social Justice

Four articles offer complementary perspectives on how school psychology can reconceptualize long standing considerations of diversity within and outside of the field to improve our responsiveness to the social injustice built into United States society and to the needs of the students and their communities. The authors acknowledge the pervasive effects of oppression on the wellbeing and education of minoritized communities and how this has shaped our field in a multitude of ways. They confront intersecting dynamics of anti-Blackness, white supremacy, and other systems of oppression in society, education, and the field of school psychology. In envisioning new frontiers for the field, they also emphasize the importance of acknowledging and reckoning with our past. Taken together, these contemporary articles provide foundations for deepening and enacting the field of school psychology’s recent commitments to social justice and antiracism, and offer valuable insights into the limitations of prior efforts to engage issues of diversity and equity.

Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022) describe five key lessons school psychology can take away from critical theories and related movements and offer a conceptual framework for critical school psychology. These lessons include (a) the necessity for school psychology to change its relationship with disabled people and to center the voices of disability activists and disabled individuals in our work; (b) the need for greater consideration of the roles of racism and the related myths of objectivity and neutrality in our work; (c) the need for intersectional resistance and partnerships with youth and communities to avoid omitting those from multiply marginalized statuses from our social justice efforts; (d) appreciation for nonlinear and nonincremental change; and (e) the importance of critical consciousness as school psychology endeavors to support positive change and social justice. Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022) propose critical school psychology as a vehicle for creating new spaces and knowledge in our field to advance social justice—for reflexivity and critique within the field, navigation of the inevitable tensions and conflict that will emerge, and alignment and partnership with social movements. Crucially, they caution against the culture of niceness, that is, prioritization of comfort and absence of tension, as an impediment to justice (the social underpinnings and harms of such niceness are also discussed by McKenney, Citation2022). In proposing a framework for creating new spaces and knowledge through critical school psychology, Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022) offer directions for expanding the way we conceptualize professional activities in the service of social justice and suggest new means for resistance and change. Importantly, the framework for critical school psychology includes approaches to meaning- and space-making likely integral to enacting the visions offered in the other articles in this special topic.

Sullivan (Citation2022) discusses the ongoing, multisystemic disruption of COVID-19 as a disaster with potential lifetime and multigenerational repercussions, particularly for minoritized communities. She provides an intersectional, interdisciplinary disaster frame for conceptualizing the unfolding and long-term effects of COVID-19 as the basis for sustained response in school psychology. In discussing the ways structural inequity manufactured minoritized communities’ elevated vulnerabilities to the health, social, and financial detriments associated with COVID-19, she calls attention to the growing needs of educators, students, and communities given protracted disruption, increasing disenfranchisement, and widespread trauma and long-covid impairments. She argues for “ideological shifts as the basis for wide-ranging reflection and re-envisioning, and even transformation, across all areas of professional activity” (Sullivan, Citation2022). Where previous movements have failed to produce deep change, she encourages centering the most marginalized, uprooting white supremacy, and intersectional understanding as key premises for responding both to the ongoing COVID-19 disaster and the imperative to advance antiracism. Sullivan (Citation2022) proposes critical consciousness, structural competency, and cultural humility as key areas for development in graduate education and practice to position school psychologists to disrupt inequity and harm grounded in structural oppression.

The role of cultural humility in advancing social justice is discussed in depth by Pham et al. (Citation2022), who note its importance at all levels of practice from individual services to systems-level work. They distinguish cultural humility from cultural competence, emphasizing the former’s emphases on accountability, advocacy, intersectionality, systemic oppression, and the tensions these often evoke. This perspective is reminiscent of the pitfalls of the culture of niceness and importance of engaging tensions and conflict that Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022) discussed. Pham et al. (Citation2022) further connect their arguments to and caution against the common intellectualization of race and racism in academic and professional spaces. They go on to explore the potentials of antiracism and anticolonialism, the latter of which has received limited attention to date within school psychology, but which together represent important elements of social justice efforts to address the pervasive harms of anti-Blackness and colonialism for Black and Indigenous people, as well as the expansive effects for society at large. Pham et al. (Citation2022) expand on previous work on social justice and cultural humility to offer a model predicated on critical reflexivity, transforming power structures, advocacy, alliance-building, and empowerment of students, families, and communities across professional activities related to research, practice, and policy.

McKenney (Citation2022) challenges us to grapple with how school psychology is structurally oriented around the social norms of White womanhood that can impede efforts for systemic change, complementary scholarship to the preceding articles. McKenney applies an interdisciplinary lens to explore how the cultural norms for and gendered socialization of White women, “shaped by two interlocking and mutually reinforcing systems: racism and misogyny,” are reflected in the standards and habits within the field. McKenney’s analysis stands as an important example of the reflexivity necessitated by the fieldwide commitment to antiracism. Here, that examination of how structures and norms shape the socialization of the White women who comprise the vast majority of our field is “one way that we can weaken the foundations of patriarchal racism” (McKenney, Citation2022).

Taken together, these authors draw on interdisciplinary scholarship from a wide range of disciplines to articulate visions for the field, suggesting the need for epistemic diversity to support key aims related to social justice and antiracism. This breadth of perspectives is particularly important for a field that has yet “to interrogate how educational systems replicate oppressive philosophies and promote ideologies incongruent with community values” wherein school psychology developed as a discipline with “early tenets of the field were steeped in the biased assumptions of the dominant culture in which schools are situated” (Grant et al., Citation2022, p. 347). The authors of the articles highlighted above encourage reflexivity and application of learnings from critical theories as a basis for individual and collective change. As Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022) observed, critical theory reminds us that we “constantly question the ways in which [our] group interests, ideological affinities, and social positions influence” our work—not just as individuals, but as a field, including how we have been complicit in various systems of oppression. Notably, these articles also share emphasis on avoiding prescription (of practices, actions, next steps) in favor of advocating for dialogue, ideological change, and empowerment of others enacted in local contexts in partnership with minoritized communities. In this way, the authors’ visions for the future of school psychology in the 21st century represent critical starting points for transformation, of which the eventual effects are unknown as they are to be co-constructed with students, families, colleagues, and other community members.

Advancing Practice to Support Student Wellness

The next set of four articles in this special topic discuss key paradigms and role shifts to position the field to better support student wellness and development. Of this set, three articles emphasize the need to understand and disrupt systemic oppression and inequity (Sheridan & Garbacz, Citation2022; Lazarus et al., Citation2022; McClain et al., Citation2022) while centering families (Sheridan & Garbacz, Citation2022) and engaging population-based frameworks (Lazarus et al., Citation2022; McClain et al., Citation2022) to advance health and wellbeing. Notably, these complementary foci rest on the critical consciousness, including understanding of macrosystemic influences, emphasized throughout the first set of articles in this special topic. These authors challenge each of us to consider how a more expansive understanding of ecological systems necessitates changes in the ways we, as a field and professionals within it, relate to students, families, and communities. Each also notes that these efforts are inseparable from understanding and disrupting inequities.

Sheridan and Garbacz (Citation2022) critiqued the strengths and limitations of Sheridan and Gutkins’ (Citation2000) contribution to the 2000 SPR mini-series, noting the importance of their call for a paradigm shift to abandon the medical model in favor of an ecological orientation and to instill a more expansive understanding of prospective targets of professional activity given the importance of systems advocacy. Sheridan and Garbacz (Citation2022) argue for greater attention to the mesosystem, particularly the relationships between families and schools, through co-equal partnerships with families informed by understanding of macrosystemic factors, including oppressive systems and deeply entrenched racial and economic inequity. Indeed, the authors propose reconceptualizing our work through prioritization of mesosystems and centering families, “changing our lens to one that embraces and ensures all families’ culturally-embedded perspectives and voices are heard and integrated in school policy and practice” (Sheridan & Garbacz, Citation2022). They advocate for a family-centered school psychology grounded in a social justice orientation that positions families as co-equal partners in services, not merely recipients of them, calling for changes in professional standards, graduate education, policy, and roles to support this vision. In particular, Sheridan and Garbacz (Citation2022) emphasize the need for the field to “clarify its approach to families as coequal partners and align and integrate activities across professional standards to elevate approaches to training and practice” as the basis for multisystem change.

McClain et al. (Citation2022) also ground their vision for the field in appreciation of ecological contexts and mesosystems, emphasizing the need for interprofessional, interagency collaboration (IIC) to address the wide-ranging needs of the students and communities our field serves. Given ongoing shortages of school psychologists, as well as the broader (and growing) shortages in educators and school-based providers generally, and expanding unmet student needs, McClain and colleagues’ approach holds promise for optimizing personnel resources in the service of student wellness. Drawing on a tripartite foundation of team-based care, population health, and implementation science as key domains of professional learning and practice, McClain et al. (Citation2022) propose schools as the “organizational conduit in which to link and deliver core functions of child health and wellness, of which education and learning are but one of many component parts” with school psychologists as leaders in the collaborative teaming and care coordination. Consistent with the first set of articles in this special topic, McClain et al. (Citation2022) argue for the preparation and engagement of school psychologists as “population health advocates that promote social justice and disrupt systems that can lead to health disparities and inequitable services” using IIC and the methods and strategies drawn from implementation science for “wellness promotion at all levels of systemic and institutional constructs, including those that are complex and pervasive (e.g., racism, socioeconomic conditions).”

Lazarus et al. (Citation2022) advocate for the culturally responsible dual factor model for contextualizing school mental health services. They promote a culturally responsible orientation “because ‘responsible’ implies taking the initiative to act in ways that are effective and ethical, and that dismantle existing disparities in children’s mental health and developmental success.” Notably, these authors call for a greater emphasis on wellness promotion, highlighting that “Promotion is about making good things happen, whereas prevention is about stopping bad things from happening” (Lazarus et al., Citation2022). They offer a gentle, needed rebuke of the disproportionate focus within the field, including within widely lauded multitier systems of support (MTSS) and problem-solving, on disturbances without such consideration or weighting of promotion of the good. As with many before them, including authors in this special topic section (McClain et al., Citation2022; Sullivan, Citation2022), they call for greater emphasis on population-based services, expanded access, and systems advocacy within and outside of educational contexts in order to address the myriad detriments of systemic racism and inequity for students’ wellbeing.

Taken together, these authors emphasize a relationship-based orientation, anchored in social justice and understanding of ecological systems, focused on both promotion and prevention to expand reach and impact of school psychology. These calls will require changes not only in how school psychologists practice, but in how they are prepared to do so, de-emphasizing assessment in favor of expanded preparation for cultivating partnerships, collaboration, teaming, advocacy, and activism. In many ways, these commentaries echo longstanding calls for the field to be more adult-focused and systems oriented (for discussion, see Conoley et al., Citation2020). Yet they also stand out for contextualizing their analyses and assertions relative to the features of our sociopolitical context, particularly in naming the effects of systemic racism and other systems of oppression in shaping students’ educational experiences. Orienting the field around these realities is crucial to fulfilling field-wide commitments to antiracism (García-Vázquez et al., Citation2020) and social justice (NASP, Citation2020), and to addressing inequality (APA, Citation2017).

The above authors espoused new directions for the field and ways to deepen and expand commitments to partnership, community engagement, and indirect services to promote wellness and equity. Yet assessment remains a primary activity of most school psychologists (Farmer et al., Citation2021); thus, in the final article in this set, Dombrowski et al. (Citation2022) synthesize and integrate the literature on evidence-based assessment (EBA), pseudoscientific practices, and low value practices, calling out the continued use and promotion of discredited practices in graduate education, professional literature, and commercial products (e.g., the dual discrepancy-consistency pattern of strengths and weaknesses method of learning disability identification). They call for professional learning and mentoring to cultivate critical thinking skills and scientific decision-making as means of self-correcting and safeguarding against continued reliance on questionable and discredited practices in order to improve the often high-stakes decision-making process that many school psychologists face.

Prioritizing the School in School Psychology

The final set of articles calls for greater consideration of the field’s orientation to schools. Rosenfield (Citation2022) doubles down on her long-standing calls (including in the 2000 SPR mini-series; Rosenfield, Citation2000) for an ecological orientation and emphasis on indirect services to address student needs, noting the challenges related to COVID-19 and widespread educational inequity. She considers the field’s resistance to change and potential inadvertent obstruction of equity, emphasizing two major impediments within the field: belief systems about student problems and insufficient professional learning for systems roles and equity. Rosenfield (Citation2022) emphasizes that training for social justice and equity—both in values and skills—must be integrated into graduate preparation in school psychology and the “daily life of practitioners.” She cautions, “Skills and beliefs must work together, or change will either be illusory or nonexistent,” a crucial reminder given the complexities of systems change where it intersects with racism and may be impeded by racial groups’ differential support for or resistance to change (e.g., Davis & Wilson, Citation2022). Both necessary components of ideological change and associated skills and practices are addressed in detail by other contributors to the special topic, underscoring their centrality to efforts to advance the field. Rosenfield (Citation2022) reminds readers that changes must be supported across all areas of preparation (e.g., curriculum content and sequencing, supervised fieldwork) as well as throughout daily practice.

Newell (Citation2022), too, considers why the field has fallen short in fulfilling the potential of the prevention oriented systems approach advocated by Shapiro (Citation2000) and others in the 2000 mini-series and elsewhere, applying the problem-solving framework to understanding the misalignment of research, graduate education, and practice in school psychology and how various barriers and reward structures contribute to the stagnation and research-to-practice gaps discussed extensively elsewhere. In particular, she discusses how differing knowledge and skills, epistemology and methods, resources, and autonomy contribute to misalignment. She expounds on how implementation science, participatory research, research communication, and changes to the reward structures of higher education, research, and practice can support alignment to improve integration of efforts to support positive educational outcomes. What’s more, such changes could be instrumental in supporting the transformation discussed by the other authors in this special topic. Combined with McKenney’s (Citation2022) discussion of the broader sociopolitical nature of the education system and its implications for school psychology’s development, stagnation, and future, these authors challenge us to critically reflect on our field’s relationships with education as a social institution and with school as a key site for the support of children and communities.

DISCUSSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

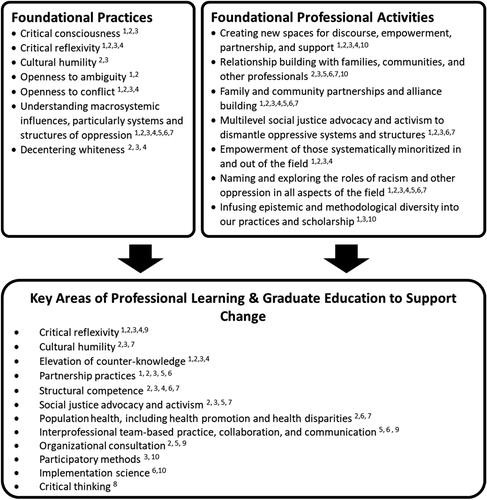

Taken together, the authors contributing to this special topic series challenge us to consider what we will do differently to fulfill the potential of school psychology and deepen our relationships with the students, families, schools, and communities we serve. They describe wide ranging changes needed that span practice, scholarship, graduate education, and professional standards in school psychology. Across articles, several foundational orientations were emphasized, including critical consciousness, critical reflexivity, and other mindsets key to engaging in sustained efforts to advance social justice and antiracism. These, and the corresponding areas of professional activity and elements of graduate education and professional learning, are summarized in .

Figure 1. Foundational Practices, Activities, and Areas of Professional Learning Described in Special Topic Articles: Reconceptualizing School Psychology for the 21st Century

Note: 1 Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022).

2 Sullivan (Citation2022).

3 Pham et al. (Citation2022).

4 McKenney (Citation2022).

5 Sheridan and Garbacz (Citation2022).

6 McClain et al. (Citation2022).

7 Lazarus et al. (Citation2022).

8 Dombrowski et al. (Citation2022).

9 Rosenfield (Citation2022).

10 Newell (Citation2022).

Such reconceptualization and changes are necessary to avoid the stagnation noted by Rosenfield (Citation2022) and lamented elsewhere (e.g., Conoley et al., 2021), as well as to fully enact commitments to dismantling systemic racism (e.g., APA, Citation2021; García-Vázquez et al., Citation2020). Further, full commitment and disruption of common habits of practice are needed, because, as Sheridan and Garbacz (Citation2022) note in discussing family partnerships, common caveats regarding feasibility undermine the depth and sustainability of efforts. Elsewhere, the importance of policy change is noted “[b]ecause school psychologists and their roles exist in the highly regulated environments of public schools and are not just the products of university research and training goals, effective models for school psychology must be supported by local policies and state regulations” (Conoley et al., Citation2020, p. 368). Herein, multiple authors too noted the importance of advocacy and activism in realizing visions for change, particularly related to disrupting injustice and promoting enfranchisement and empowerment of systematically minoritized groups, including reckoning with the effects of colonialism and need for decolonization (Pham et al., Citation2022; Sullivan, Citation2022) as a future direction for the field (see also Grant et al., Citation2022). Many authors in this special topic suggest the need to examine the ideological bases of common practices and school psychologists’ relations to communities engaged. This is no simple undertaking, but it represents a necessary effort to align action with the ideals expressed herein and elsewhere, and, ultimately, to ensure school psychology advances justice. We also direct readers to access the numerous articles that have recently been featured and are forthcoming in School Psychology Review relevant to further informing our reflexivity, actions, advocacy, and activism related to numerous contemporary topics in school psychology (e.g., Arora et al., Citation2022; Collins et al., Citation2022; Edyburn et al., Citation2022; Elianny, Citation2021; Fallon et al., Citation2021; Grapin & Fallon, Citation2022; Hines et al., Citation2022; Holman et al., Citation2021; Proctor et al., Citation2022; Rivas-Koehl et al., Citation2022; Sabnis & Newman, Citation2022).

These changes have the potential to transform school psychology’s relationships with students, families, education professionals, and communities as they change the work of school psychologists across our varied professional contexts. Beyond changing the work of school psychologists, these changes also have the potential to change the face of the field. In the 2000 SPR mini-series, authors noted that the field was overwhelmingly White (92%; Swerdlik & French, Citation2000), with calls for diversification. Yet, as of 2020, approximately 86% of school psychologists are White, with “more than 80% of school psychologists identified as [women], White, able-bodied, and monolingual” (Goforth et al., Citation2021), highlighting how little relative progress has been made even though more than half of school-aged children and youth are from racially minoritized backgrounds (Jimerson et al., Citation2021; U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2018). The changes discussed herein hold promise for driving large scale changes in how school psychology is perceived and experienced by others because the scholarship and practice of school psychology play important roles in recruitment and retention of school psychologists from minoritized communities, as well as individuals more generally concerned with systems change and social justice. As Sullivan (Citation2022) asserts, the directions discussed throughout this set of articles are likely “integral to making school psychology hospitable for, attractive to, and supportive of prospective and current school psychologists from minoritized backgrounds.”

The current special topic is but one element of a larger discourse about the past, present, and future of the field that is occurring across a range of contexts, from the more traditional academic ones such as this special topic and other scholarship in school psychology, as well as statements and initiatives of professional organizations, to grassroots advocacy, collective action, peer supports, and individual activities in schools, communities, and graduate programs. This special topic is bounded in form and structure by virtue of its home within an academic journal and the parameters of the call for submissions, as well as by the necessarily limited perspectives of its authors. These articles represent vision and possibility that should be subject to critique, refinement, and enactment in local contexts by the diverse constituencies of school psychology in collaboration and partnership with the communities we engage. Such co-construction is, as noted by multiple authors in this special topic, crucial to ensuring the contextual relevance, cultural responsiveness, and social justice core of subsequent change and action. It is our hope, as editors of this special topic, that the articles herein will spur reflection and change across all aspects of the field.

Taken together, the articles in this special topic provide ample bases for reflection and action as school psychologists endeavor to remain responsive to rapidly changing contexts, as social and environmental conditions challenge our efforts to support individual and community wellbeing, and as social movements demand change in society and schools. These articles provide important impetus and direction for rallying individual and institutional resources to combat stasis and resistance. Collectively, these scholars articulate extensive changes needed to orient school psychology for justice and wellness promotion. Many of these recommendations will require extensive changes across all aspects of school psychology, which, will in turn, necessitate replacing common beliefs, assumptions, and practices. These changes will not happen on their own; rather, they will require a commitment and systematic efforts from academics, practitioners, and professional associations. The articles and recommendations should push each of us to consider what we will give up to make these changes reality (Sullivan, Citation2022). We must do so without knowing how exactly these changes will in turn change our field, with, as Sabnis and Proctor (Citation2022) point out, openness to the nonlinear and nonincremental change as we pursue “collective dreams and liberatory spaces” (Page as cited in Sullivan, Citation2022).

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amanda L. Sullivan

Amanda L. Sullivan is the Birkmaier Educational Leadership Professor and director of the School Psychology Program at the University of Minnesota. Her research focuses on identifying education and health disparities affecting students from minoritized backgrounds, understanding (in)equity in and effectiveness of the educational and health services they receive, and exploring how ethics and law shape professional practices and students’ experiences. Twitter: @DrSullivanAL

Frank C. Worrell

Frank C. Worrell, PhD is a Distinguished Professor in the School of Education at the University of California, Berkeley. His areas of expertise include academic talent development/gifted education, at-risk youth, cultural identities, scale development and validation, teacher effectiveness, time perspective, and the translation of psychological research findings into school-based practice. Twitter: @FrankCWorrell

Shane R. Jimerson

Shane R. Jimerson, PhD is a Professor University of California, Santa Barbara and Nationally Certified School Psychologist. His scholarship focuses on understanding and supporting the social, emotional, behavioral, academic, and mental health development of youth and also understanding and advancing the field of school psychology internationally. Twitter: @DrJ_ucsb

Notes

1 From extensions on the original call for submissions to those in the peer review process, this special topic has been a long time coming. COVID-19 and the movements for antiracism brought to the forefront the importance of grace. These cultural phenomena conveyed the need to reconsider the extent to which professional processes, expectations, and assumptions are conducive to health and antiracism.

REFERENCES

Note: Articles below with ** are featured in the current special topic section of School Psychology Review: Reconceptualizing School Psychology for the 21st Century: The Future of School Psychology

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/multicultural-guidelines.

- American Psychological Association. (2021, October 29). Apology to people of color for APA’s role in promoting, perpetuating, and failing to challenge racism, racial discrimination, and human hierarchy in US: Resolution adopted by the APA Council of Representatives. https://www.apa.org/about/policy/racism-apology.

- Arora, P., Sullivan, A. L., & Song, S. (2022). On the imperative for reflexivity in school psychology scholarship. School Psychology Review, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2105050

- Blake, J. J., Graves, S., Newell, M., & Jimerson, S. R. (2016). Diversification of school psychology: Developing an evidence base from current research and practice. School Psychology Quarterly : The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 31(3), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000180

- Buchanan, L., Bui, Q., & Patel, J. K. (2020, July 3). Black Lives Matter may be the largest movement in U.S. history. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd-protests-crowd-size.html

- Cacioppo, J. T. (2013). Psychological science in the 21st century. Teaching of Psychology, 40(4), 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628313501041

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, October 10). COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker

- Collins, T. A., La Salle, T. P., Rocha Neves, J., Foster, J. A., & Scott, M. N. (2022). No safe space: School climate experiences of black boys with and without emotional and behavioral disorders. School Psychology Review, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2021783

- Conoley, J. C., Powers, K., & Gutkin, T. B. (2020). How is school psychology doing: Why hasn’t school psychology realized its promise? School Psychology (Washington, D.C.), 35(6), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000404

- Crenshaw, K. (2021, July 2). The panic over critical race theory is an attempt to whitewash U.S. history. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/critical-race-theory-history/2021/07/02/e90bc94a-da75-11eb-9bbb-37c30dcf9363_story.html

- Davis, D. W., & Wilson, D. C. (2022). The prospect of antiracism: Racial resentment and resistance to change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 86(S1), 445–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfac016

- **Dombrowski, S. C., McGill, R. J., Farmer, R. L., Kranzler, J. H., & Canivez, G. L. (2022). Beyond the rhetoric of evidence-based assessment: A framework for critical thinking in clinical practice. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1960126

- Edyburn, K. L., Bertone, A., Raines, T. C., Hinton, T., Twyford, J., & Dowdy, E. (2022). Integrating intersectionality, social determinants of health, and healing: A new training framework for school-based mental health. School Psychology Review, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2024767

- Elianny, E. C. (2021). Centering race to move towards an intersectional ecological framework for defining school safety for Black students. School Psychology Review, 50(2–3), 254–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1930580

- Fagan, T. K., Gorin, S., & Tharinger, D. (2000). The National Association of School Psychologists and the Division of School Psychology—APA: Now and beyond. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 525–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086037

- Fagan, T. K., & Sheridan, S. M. (2000). Introduction to the mini-series: School psychology in the 21st century. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 483–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086031

- Fallon, L. M., Veiga, M., & Sugai, G. (2021). Strengthening MTSS for behavior (MTSS-B) to promote racial equity. School Psychology Review, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1972333

- Farmer, R. L., Goforth, A. N., Kim, S. Y., Naser, S. C., Lockwood, A., & Affrunti, N. (2021). Status of school psychology in 2020: Part 2, professional practices in the NASP membership survey. NASP Research Reports, 5(3), 1–17. https://www.nasponline.org/Documents/Research%20and%20Policy/Research%20Center/RR_NASP-2020-Membership-Survey-part-2.pdf

- García-Vázquez, E., Reddy, L., Arora, P., Crepeau-Hobson, F., Fenning, P., Hatt, C., Hughes, T., Jimerson, S., Malone, C., Minke, K., Radliff, K., Raines, T., Song, S., & Strobach, K. V. (2020). School psychology unified antiracism statement and call to action. School Psychology Review, 49(3), 209–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1809941

- Goforth, A. N., Brown, J. A., Machek, G. R., & Swaney, G. (2016). Recruitment and retention of Native American graduate students in school psychology. School Psychology Quarterly : The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 31(3), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000160

- Goforth, A. N., Farmer, R. L., Kim, S. Y., Naser, S. C., Lockwood, A. B., & Affrunti, N. W. (2021). Status of school psychology in 2020: Part 1, demographics of the NASP membership survey. NASP Research Reports, 5(2), 1–17. https://www.nasponline.org/research-and-policy/research-center/member-surveys

- Grant, S., Leverett, P., D’Costa, S., Amie, K. A., Campbell, S. M., & Wing, S. (2022). Decolonizing school psychology research: A systematic literature review. Journal of Social Issues, 78(2), 346–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12513

- Grapin, S. L., & Fallon, L. M. (2022). Conceptualizing and dismantling white privilege in school psychology research: An ecological model. School Psychology Review, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1963998

- Grapin, S. L., Lee, E. T., & Jaafar, D. (2015). A multilevel framework for recruiting and supporting graduate students from culturally diverse backgrounds in school psychology programs. School Psychology International, 36(4), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315592270

- Graves, S. L., Jr., & Wright, L. B. (2009). Historically Black colleges and university students’ and faculties’ views of school psychology: Implications for increasing diversity in higher education. Psychology in the Schools, 46(7), 616–626. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20402

- Gutkin, T. B., & Conoley, J. C. (1990). Reconceptualizing school psychology from a service delivery perspective: Implications for practice, training, and research. Journal of School Psychology, 28(3), 203–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(90)90012-V

- Hatzichristou, C. (2002). A conceptual framework of the evolution of school psychology: Transnational considerations of common phases and future perspectives. School Psychology International, 23(3), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034302023003322

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

- Hines, E. M., Mayes, R. D., Harris, P. C., & Vega, D. (2022). Using a culturally responsive MTSS approach to prepare Black males for postsecondary opportunities. School Psychology Review, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2018917

- Hofstra, B., Kulkarni, V. V., Munoz-Najar Galvez, S., He, B., Jurafsky, D., & McFarland, D. A. (2020). The diversity–innovation paradox in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(17), 9284–9291. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1915378117

- Holman, A. R., D’Costa, S., & Janowitch, L. (2021). Toward equity in school-based assessment: Incorporating collaborative/therapeutic techniques to redistribute power. School Psychology Review, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1997060

- Jimerson, S. R. (2020, February). Advancing science, practice, policy, and diversity in the field of school psychology. National Association of School Psychologists. https://www.nasponline.org/Documents/Resources%20and%20Publications/Periodicals/SPR/School%20Psychology%20Review_Vision-Statement.pdf

- Jimerson, S. R., Arora, P., Blake, J. J., Canivez, G. L., Espelage, D. L., Gonzalez, J. E., Graves, S. L., Huang, F. L., January, S. A., Renshaw, T. L., Song, S. Y., Sullivan, A. L., Wang, C., & Worrell, F. C. (2021). Advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion in school psychology: Be the change. School Psychology Review, 50(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1889938

- Jimerson, S. R., Oakland, T. D., & Farrell, P. T. (Eds.). (2007). The handbook of international school psychology. SAGE.

- Kratochwill, T. R., & Stoiber, K. C. (2000). Uncovering critical research agendas for school psychology: Conceptual dimensions and future directions. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086048

- **Lazarus, P. J., Doll, B., Song, S. Y., & Radliff, K. (2022). Transforming school mental health services based on a culturally responsible dual-factor model. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 755–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1968282

- Liu, S., & Oakland, T. (2016). The emergence and evolution of school psychology literature: A scientometric analysis from 1907 through 2014. School Psychology Quarterly : The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 31(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000141.

- **McClain, M. B., Shahidullah, J. D., Harris, B., McIntyre, L. L., & Azad, G. (2022). Reconceptualizing educational contexts: The imperative for interprofessional and interagency collaboration in school psychology. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 742–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1949247

- **McKenney, E. L. (2022). Reckoning with ourselves: A critical analysis of white women’s socialization and school psychology. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 710–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1956856

- Nastasi, B. K. (2000). School psychologists as health-care providers in the 21st century: Conceptual framework, professional identity, and professional practice. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 540–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086040

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2021). The importance of addressing equity, diversity, and inclusion in schools: Dispelling myths about critical race theory [Handout]. https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/diversity-and-social-justice/social-justice/the-importance-of-addressing-equity-diversity-and-inclusion-in-schools-dispelling-myths-about-critical-race-theory

- National Association of School Psychologists. (2020). The professional standards of the National Association of School Psychologists. National Association of School Psychologists.

- **Newell, K. W. (2022). Realignment of school psychology research, training, and practice. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 795–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2000841

- Oakland, T., & Hatzichristou, C. (2014). Professional preparation in school psychology: A summary of information from programs in seven countries. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 2(3), 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2014.934638

- Pennington, M. (2019, December 17). 25 ways America has changed in the last decade. https://stacker.com/stories/3779/25-ways-america-has-changed-last-decade

- **Pham, A. V., Goforth, A. N., Aguilar, L. N., Burt, I., Bastian, R., & Diaków, D. M. (2022). Dismantling systemic inequities in school psychology: Cultural humility as a foundational approach to social justice. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 692–709. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1941245

- Price, K. W., Floyd, R. G., Fagan, T. K., & Smithson, K. (2011). Journal article citation classics in school psychology: Analysis of the most cited articles in five school psychology journals. Journal of School Psychology, 49(6), 649–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.10.001

- Proctor, S. L. (2022). From Beckham until now: Recruiting, retaining, and including Black people and Black thought in school psychology. School Psychology International, 43(6), 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343211066016

- Proctor, S. L., Kyle, J., Fefer, K., & Lau, Q. C. (2018). Examining racial microaggressions, race/ethnicity, gender, and bilingual status with school psychology students: The role of intersectionality. Contemporary School Psychology, 22(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0156-8

- Proctor, S. L., Li, K., Chait, N., & Gulfaraz, S. (2022). Use of critical race theory to understand the experiences of an African American male during school psychology graduate education. School Psychology Review, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2036077

- Proctor, S. L., & Truscott, S. D. (2012). Reasons for African American student attrition from school psychology programs. Journal of School Psychology, 50(5), 655–679.

- Reschly, D. J. (2000). The present and future status of school psychology in the United States. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 507–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086035

- Rivas-Koehl, M., Valido, A., Espelage, D. L., Robinson, L. E., Hong, J. S., Kuehl, T., Mintz, S., & Wyman, P. A. (2022). Understanding protective factors for suicidality and depression among U.S. sexual and gender minority adolescents: Implications for school psychologists. School Psychology Review, 51(3), 290–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1881411

- **Rosenfield, S. (2022). Strengthening the school in school psychology training and practice. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 785–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1993032

- Rosenfield, S. (2000). Commentary on Sheridan and Gutkin: Unfinished business. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 505–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086034

- Rozensky, R. H., Grus, C. L., Fouad, N. A., & McDaniel, S. H. (2017). Twenty-five years of education in psychology and psychology in education. The American Psychologist, 72(8), 791–807. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000201

- Sabnis, S. V., & Newman, D. S. (2022). Epistemological diversity, constructionism, and social justice research in school psychology. School Psychology Review, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2094283

- **Sabnis, S. V., & Proctor, S. L. (2022). Use of critical theory to develop a conceptual framework for critical school psychology. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 661–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1949248

- Sanetti, L. M. H., & Collier-Meek, M. A. (2019). Increasing implementation science literacy to address the research-to-practice gap in school psychology. Journal of School Psychology, 76, 33–47.

- Schaeffer, K. (2019). US has changed in key ways in the past decade, from tech use to demographics. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/12/20/key-ways-us-changed-in-past-decade/

- Schanding, G. T., Jr, Strait, G. G., Morgan, V. R., Short, R. J., Enderwitz, M., Babu, J., & Templeton, M. A. (2021). Who’s included? Diversity, equity, and inclusion of students in school psychology literature over the last decade. School Psychology Review, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1927831

- Shapiro, E. S. (2000). School Psychology from an instructional perspective: Solving big, not little problems. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086043

- Shaw, S. R. (2021). Implementing evidence-based practices in school psychology: Excavation by de-implementing the disproved. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 36(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/08295735211000513

- **Sheridan, S. M., & Garbacz, S. A. (2022). Centering families: Advancing a new vision for school psychology. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 726–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1954860

- Sheridan, S. M., & Gutkin, T. B. (2000). The ecology of school psychology: Examining and changing our paradigm for the 21st century. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086032

- Song, S. Y., Miranda, A. H., Radliff, K. M., & Shriberg, D. (2019). School psychology in a global society: Roles and functions. National Association of School Psychologists.

- Song, S. Y., Wang, C., Espelage, D. L., Fenning, P., & Jimerson, S. R. (2020). COVID-19 and school psychology: Adaptations and new directions for the field. School Psychology Review, 49(4), 431–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1852852

- Song, S. Y., Wang, C., Espelage, D. L., Fenning, P. A., & Jimerson, S. R. (2022). COVID-19 and school psychology: Research reveals the persistent impacts on parents and students, and the promise of school telehealth supports. School Psychology Review, 51(2), 127–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2044237

- Song, S. Y., Wang, C., Espelage, D. L., Fenning, P. A., & Jimerson, S. R. (2021). COVID-19 and school psychology: Contemporary research advancing practice, science, and policy. School Psychology Review, 50(4), 485–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1975489

- **Sullivan, A. L. (2022). Overcoming disaster through critical consciousness and ideological change. School Psychology Review, 51(6), 676–691. 10.1080/2372966X.2022.2093127

- Sullivan, A. L. (2021, April). Developing and advancing antiracist scholarly practice [Paper presentation]. Virtual Conference, Decolonizing Psychology Training: Strategies for Addressing Curriculum, Research Practices, Clinical Supervision, and Mentorship. Teachers College, Columbia University. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d0diS_IMl2k

- Swerdlik, M. E., & French, J. L. (2000). School psychology training for the 21st century: Challenges and opportunities. School Psychology Review, 29(4), 577–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2000.12086046

- Truong, D. M., Tanaka, M. L., Cooper, J. M., Song, S., Talapatra, D., Arora, P., Talapatra, D., Arora, P., Fenning, P., McKenney, E., Williams, S., Stratton-Gadke, K., Jimerson, S. R., Pandes-Carter, L., Hulac, D., & García-Vázquez, E. (2021). School psychology unified call for deeper understanding, solidarity, and action to eradicate anti-AAAPI racism and violence. School Psychology Review, 50(2–3), 469–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.1949932

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2018, December 11). More than 76 million students enrolled in U.S. schools, census bureau reports [News release]. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2018/school-enrollment.html

- Villarreal, V., & Umaña, I. (2017). Intervention research productivity from 2005 to 2014: Faculty and university representation in school psychology journals. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 1094–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22048

- Worrell, F. C. (2022, October 6). Beyond APA’s apology to people of color: A conversation on equity, diversity, inclusion, justice, and belonging. North Carolina State University. https://vimeo.com/757770186/20d16b37e7

- Worrell, F. C., Hughes, T. L., & Dixson, D. D. (Eds.). (2020). The Cambridge handbook of applied school psychology. Cambridge University Press.