ABSTRACT

Professional agency is key for teachers’ professional development, for constructing their professional identity, and for promoting student learning. This longitudinal study explored the development of teachers’ (N = 201) sense of professional agency in the classroom in the professional transition from early career teachers to more experienced ones. We used latent profile analysis to examine the individual variation and change in teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom in a five-year follow-up. The results showed three distinctive profiles: a high sense of professional agency (64%), a moderate sense of professional agency (32%), and a low sense of professional agency (4%) in the classroom. The changes detected in the three teachers’ sense of professional agency profiles varied. The profiles were associated with teacher groups (i.e., primary teachers, subject teachers, and special education teachers), but not with stress, attrition intention or school size. The results imply that teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom does not always increase in tandem with experience, and thus, different kinds of support are needed for cultivating teachers’ sense of professional agency over time.

Introduction

It has been suggested that teachers’ professional agency in the classroom is key for promoting teacher’s professional development, for their commitment to school development, and for supporting pupils’ learning (Bronkhorst et al., Citation2011; Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015). Professional agency refers to teachers’ ability to manage their learning (Pyhältö et al., Citation2012) actively and intentionally. It consists of integrated elements of teachers’ motivation to learn, self-efficacy beliefs related to learning, and intentional strategies for enhancing collaborative learning in the classroom (Edwards, Citation2005; Soini et al., Citation2016). Such agency has shown to be related to pupils’ agency, engagement in school improvement, experimenting with pedagogical innovations, reduced teacher stress, and a lower risk of career turnover (Edwards, Citation2005; Gordon et al., Citation2007; Lipponen & Kumpulainen, Citation2011; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Pyhältö, Pietarinen, Toom, Haverinen, Beijaard, & Soini, Citationsubmitted). However, teachers’ professional agency in the classroom is not a stable, individual disposition: it constantly changes depending on teacher work environment dynamics (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; Eteläpelto et al., Citation2013).

Accordingly, the development of teachers’ professional agency cannot be taken for granted and is not linear (Darling-Hammond, Citation2008). In fact, there is some evidence that learning through experimenting with teaching methods can decrease over time (Flores, Citation2005). Moreover, it has been suggested that particularly early career teachers often experience difficulties when they encounter the complexity of teaching and the realities of teachers’ work during the transition to becoming more experienced teachers (Harmsen et al., Citation2018; Hobson et al., Citation2009; Pillen et al., Citation2013; Voss & Kunter, Citation2020) and this potentially also challenges the sense of professional agency in the classroom, particularly if sufficient support is not available. Yet overcoming such challenges may increase teachers’ professional agency (Flores, Citation2005; Korthagen, Citation2010; McDonald, Citation1982; Mena et al., Citation2017). Several individual and contextual factors may either benefit or constrain the development of early career teachers’ sense of professional agency, such as stress, doubts about career fit, teacher groups, and school size (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Klassen et al., Citation2013; Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted; Van Eekelen et al., Citation2006). However, the current understanding of the individual variation in teachers’ professional agency and its development during the professional transition from early career teachers to more experienced ones is insufficient (Heikonen et al., Citation2020). Even less is known about the associations between teachers’ professional agency profiles and their individual and contextual attributes. We aim to contribute to bridging this gap in the literature by exploring the individual variation in early career teachers’ professional agency in the classroom; its development in the professional transition from early career teachers to more experienced ones during the five-year follow-up; and the relationships between teachers’ professional agency profiles and several individual and contextual attributes, including stress, attrition intentions, teacher type and school size. Accordingly, the present study provides an understanding of the change in early career teachers’ professional agency in the classroom during the professional transition from early career teachers to more experienced ones, and the related attributes. This understanding will enable the development of well-suited means to support and cultivate the professional agency of teachers in pre- and in-service teacher training.

Theoretical framework

Teachers’ professional agency in the classroom

In this study, we use the term teachers’ professional agency in the classroom to refer to teachers’ ability to prepare the way for actively and intentionally managing new learning in the classroom (Pyhältö et al., Citation2012; Soini et al., Citation2016). Previous studies have shown that teachers’ professional agency consists of three interrelated components of teachers’ motivation to learn (I want), efficacy beliefs for learning (I am able), and active strategies for facilitating learning (I can and do) in everyday practices in the classroom (e.g., Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Toom et al., Citation2017; Van Eekelen et al., Citation2006; Wheatley, Citation2005). This study drew on the definition and claims that teachers’ professional agency can be regarded as a prerequisite for learning and learning as the object of teachers’ professional agency (Edwards, Citation2005; Edwards & D’arcy, Citation2004; Van Eekelen et al., Citation2006). As such, teachers’ professional agency can be considered highly context-dependent (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, Citation2011), which means that the professional agency in the classroom is embedded in the pedagogical interactions between teachers and students in the classroom. Accordingly, the three components of professional agency (i.e., teachers’ motivation, self-efficacy, and skills for learning) in the classroom are ingrained in two contextualised modes of professional agency in the classroom: reflection in the classroom and intentional efforts to develop a collaborative environment (Soini et al., Citation2016). In several studies, teachers have reported that reflection is one of the most important modes of learning (Lohman, Citation2006). Learning through reflection involves active observation and meaning-making to improve teaching and enhance learning (Eraut, Citation1995; Naidoo & Kirch, Citation2016). This further enables teachers to become aware of and monitor classroom interaction (Hatton & Smith, Citation1995). It also enables them to seek other perspectives, gain insights into pupils’ ways of thinking, and improve their learning (Loughran, Citation2002). Learning by creating collaborative environment consists of responsive adaptation of classroom practices aimed at promoting reciprocal learning (Soini et al., Citation2016). This entails actively using others (e.g., pupils) as a resource for learning, in turn supporting their learning (Edwards, Citation2005). It further requires teachers to build positive relationships with pupils (Wubbels & Brekelmans, Citation2005). However, developing a collaborative climate is not easy, and early career teachers seem to find it difficult to consider pupils’ needs and to deal with individual differences (Fantilli & McDougall, Citation2009). Yet, building such a classroom environment enables the enhancement of new learning for both pupils and teachers (Spilt et al., Citation2011).

The initial years of teaching constitute a significant phase in professional growth, and classroom experiences play a central role in early career teachers’ learning and their commitment to teaching (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Meristo & Eisenschmidt, Citation2014). The first five years in teaching are also characterised by uncertainty and a certain amount of stress (Berliner, Citation1986) due to having to deal with several learning demands and responsibilities without established practices or ways of doing teachers’ work. Teachers’ classroom experiences pave the way for their future teaching careers, professional development, and occupational well-being (Kwakman, Citation2003; Virtanen et al., Citation2019). Despite being on an intensive learning curve, active teacher learning cannot be taken for granted (Darling-Hammond, Citation2008).

Development of teachers’ professional agency

Teachers’ professional agency in classroom evolves and continuously changes depending on themselves, their interactions with others (i.e., pupils), and context (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; Greeno, Citation2006). This means that their learning is greatly influenced by the quality of the social interactions in the classroom over time. In addition, professional agency largely relies on contextual factors (Pietarinen et al., Citation2016). For example, situational factors such as school cultures, workplace conditions (i.e., school size) and educational policy may impact teachers’ professional agency (Bakkenes et al., Citation2006; Oosterheert & Vermunt, Citation2001).

There is some evidence that individual variation in professional agency is related to stress, attrition intention, and teacher type (Klassen et al., Citation2013; Van Eekelen et al., Citation2006). Heikonen et al. (Citation2017) found a negative association between teachers’ turnover intentions and their professional agency which was mediated by their inadequacy in the teacher-student relationship. Moreover, teachers’ work-related stress has a negative relationship with their commitment to learning (Klassen et al., Citation2013). Teachers’ professional agency is also always dependent on the aims of learning and how they perceive these aims (Edwards, Citation2007; Engeström, Citation2005; Toom et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, different types of teachers would perceive the object of activity through their personal understanding, and may therefore have a different understanding of how to manage new learning.

One would expect teachers to become more agentic as they gain more experience. However, teachers’ professional agency may also change in the opposite direction over time (Clark, Citation2020; Stein & Wang, Citation1988). It has been suggested that the development of teachers’ professional agency may not be linear (cf., Heikonen et al., Citation2020; Pietarinen et al., Citation2016), especially during the transition from early career teachers to more experienced ones. The reason for this is that the complexity of teaching and classroom dynamics would make early career teachers who are undergoing a period of varied, difficult, and crucial opportunities for learning and professional development (Flores, Citation2005) reconsider their professional beliefs and practices (Borko, Citation2004). This could result in a possible increase or decrease in their professional agency in the future development. In addition, it has been concluded that the professional agency development of individual teachers varies over time (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; Greeno, Citation2006; Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted). Although interest in the individual variations in active teacher learning has grown recently (Jääskelä et al., Citation2020), studies of teachers’ professional agency have mainly utilised a variable-centred rather than a person-centred approach. Thus, more studies are needed to investigate individual differences in teachers’ professional agency and its development by using latent profile analysis, which is a person-centred approach. This study was conducted in Finland, where comprehensive schools provide the work environment for different types of teachers (i.e., primary teachers, subject teachers, and special education teachers).

Aim of the study

The aim of this study is to gain a better understanding of the variation and change in teachers’ professional agency from early career teachers to more experienced ones in a five-year follow-up. Lavigne (Citation2014) suggests that early career teachers are teachers in their first five years of teaching. Thus, this study aims to contribute to a better understanding of how teachers’ professional agency in the classroom develops during their first years in the teaching profession. We applied latent profile analysis to detect individual variation in professional agency. The five-year follow-up enabled us to detect changes in teachers’ professional agency. Earlier research on teachers’ professional agency has indicated that variation occurs in teachers’ professional agency in terms of school reforms (Pyhältö et al., Citation2012; Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted). We presume that such variations are also likely to exist in teachers’ professional agency in the classroom. Moreover, previous studies have shown that student teachers develop a higher degree of professional agency during the first three years of studying (Heikonen et al., Citation2020). Based on this, we presumed that we would be able to detect increases in teachers’ professional agency in a five-year follow-up. Finally, we analysed the associations between the background variables (i.e., teacher stress, attrition intentions, teacher groups, and school size) and teachers’ professional agency profiles.

The following three specific hypotheses were tested:

H1. Several profiles of perceived professional agency in the classroom will be detected among teachers (Pyhältö et al., Citation2012; Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted).

H2. Increases in the sense of professional agency in the classroom will be detected in a five-year follow-up (Heikonen et al., Citation2020).

H3. Professional agency in the classroom profiles will be associated with stress, attrition intentions, teacher groups, and school size (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Klassen et al., Citation2013; Van Eekelen et al., Citation2006).

Methods

Research context

In Finland, comprehensive school teachers are primary, subject, and special education teachers. Primary teachers have a five-year university master’s degree in education or educational psychology, and they are typically responsible for teaching grades one to six of basic education. Subject teachers, who are qualified to teach one or several subjects, have a master’s degree in a subject domain with pedagogical study as a minor subject in educational sciences (60 ECTS). They typically teach grades seven to nine, or in general upper secondary education. Special education teachers hold a master’s degree in special education. They teach grades one to nine in basic education at both primary and secondary schools. Finnish teacher education aims to qualify professional, reflective teachers through a research-based approach (Hansén & Eklund, Citation2014). Thus, teacher education programmes encourage student teachers to develop a reflective approach to teaching and the teaching profession (Kansanen, Citation2014).

Finnish teachers have a high degree of autonomy in their work and a relatively high status. They are free to plan their work, decide on learning materials and implement pupil assessment within the framework of the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2014). They are also involved in developing the local and school-specific curricula. In general, a high degree of autonomy and trust in teachers’ work is typical in the Finnish context, in both teacher education and schools (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015). This kind of autonomy is based on teacher professionalism (Day, Citation2021; Day & Smethem, Citation2009; Webb et al., Citation2004), which has been supported by academic university education since the 1970s (Tirri, Citation2014). Teachers were given more responsibilities when curricula were decentralised during the 1980s and 1990s (ibid.). This atmosphere supports all teachers to develop a learning environment and teaching collaboratively (Lavonen, Citation2016). Comprehensive education is funded by the government, but municipalities are responsible for providing all students with equal basic education. Students are not divided into academic or vocational tracks. The accountability structure is designed to maintain trust in individual schools (Sahlberg, Citation2010). In Finland, early career teachers are not provided with systematic mentoring programmes.

Participants

The data used in this longitudinal research were collected in 2011 (Time 1) and 2016 (Time 2) from teachers in Finland. The survey was sent to 2000 teachers in each teacher group (i.e., primary teachers, subject teachers, and special education teachers) using a probability sampling method (N = 6000), and 2310 comprehensive school teachers responded. The response rate was 39%. The 2310 teachers who responded represented the Finnish teacher population relatively well, although the number of female teachers was slightly higher (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013). In this study, teachers in their induction phase with 0–5 years of teaching experience at T1 were extracted from the national sample, setting the sample size at N = 284. In total, 71% of these teachers participated at the second measurement point. The final respondents comprised the 201 teachers who participated at both measurement points. The non-response analysis indicated that the responses of the participants who responded at both measurement points and of those who only responded at T1 did not differ statistically significantly in terms of professional agency and background variables. The participants comprised primary (N = 56; 28%), subject (N = 48; 24%), and special education teachers (N = 97, 48%) at T1. The mean age of the participants was 32.4 years (SD = 4.49; min/max = 25/51 years) at T1. The majority of respondents were women (N = 182; 90.5%), and the minority of participants were men (N = 19; 9.5%). The mean teaching experience was 4.03 years (SD = .96; min/max = 1/5 years) at T1. All the respondents had a master’s degree. The survey permission to participate in the survey was sought from the respondents and the municipalities, in line with Finland’s ethical guidelines.

Measures

The Teachers’ Sense of Professional Agency survey was used in collecting the self-report data for the study (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015; Soini et al., Citation2016). In this study, professional agency in the classroom scale (PAC) included in the survey was used. The PAC scale and the factorial structures have been validated in earlier studies, including pilot testing and a series of studies with a representative national sample (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Pietarinen et al., Citation2013; Soini et al., Citation2016, Citation2015). The PAC scale (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013; Soini et al., Citation2016) measured two components of teachers’ professional agency: Collaborative environment and transformative practice (CLE) (six items); and Reflection in classroom (REF) (four items). Thus, the scale allowed us to examine the key components of early career teachers’ professional agency in the classroom.

shows the scale, items, Cronbach’s alphas, and McDonald’s coefficient omega.

Table 1. The scale and items for exploring the early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in classroom at Time 1 and Time 2.

The items in this scale were all rated on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). Cronbach’s alphas and McDonald’s coefficient omega at two time points were presented in (Hayes & Coutts, Citation2020). The Cronbach’s alphas showed a sufficient level of reliability (Pallant, Citation2001). The McDonald’s coefficient omega showed a sufficient level in terms of building a collaborative environment at two measurement points and reflection in the classroom at time point 2 and was close to the acceptable level in terms of reflection in the classroom at time point 1 (Hair et al., Citation2010). The percentage of missing values per item varied from 0 to 1 and the data were missing completely at random (Little’s MCAR test: χ2 (57) = 49.71; p = .74).

The background variables used in this study were work-related stress, which was measured using one item (Elo et al., Citation2003) with a ten-point Likert scale transformed into categorical variables (no stress, moderate stress, and extreme stress), attrition intention (yes and no), teacher groups (primary, subject, and special education teachers) and school size (small, medium, and big schools).

Analyses

First, the validity of the scales was examined using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Model fit was examined using a gamma hat, the comparative fit index (CLI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The reason for using gamma hat rather than the Chi-square test as the model fit index is that Chi-square is overly sensitive to the sample size (Cheung & Rensvold, Citation2002; Meade et al., Citation2008). In addition, the correlations in the present model can also affect Chi-square; specifically, the larger the correlations, the poorer the fit (Kenny, Citation2020). As a result, the large sample size and interrelated components of professional agency in this study are more likely to indicate poor fit in the Chi-Square test. However, the Chi-square test was reported in this study for the descriptive purpose. A gamma hat above 0.95, a CFI and TLI above 0.90, an RMSEA below 0.08, and an SRMR below 0.08 all indicated a good model fit (Beauducel & Wittmann, Citation2005; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). The model was specified by adding residual covariances which were acceptable with respect to the theoretical framework by Pietarinen et al. (Citation2016). In this study, the residual covariance Cle 11 with Cle 12 was released at both T1 and T2. The goodness-of-fit indicators of the tested model at T1 showed that a significant χ2 value indicated a poor fit, whereas the gamma hat = 0.97, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.07 and SRMR = 0.05) indicated a good fit. At T2, the CFI (0.92), SRMR (0.06) and gamma hat (0.95) indicated a good model fit, and TLI (0.89) and RMSEA (0.09) were very close to a sufficient fit, although the χ2 test indicated a poor fit. The validity of the scale has also been confirmed in prior studies (e.g., Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Soini et al., Citation2016).

A latent profile analysis, using Mplus 8.4, examined the individual variations in teachers’ sense of professional agency and its development (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2015). A person-centred approach detects the variations in how variables are associated with each other among individuals and identifies groups of individuals who share similar characteristics (Bergman & Trost, Citation2006; Laursen & Hoff, Citation2006). Latent profile analysis is a person-centred approach that focuses on individuals’ response patterns in the data (Berlin et al., Citation2014). It is used to identify subgroups that are not observed, such as the latent classes of individuals in terms of the response patterns present in the data (ibid.). The observed mean variables of the two professional agency subscales at the two measurement points were used as latent class indicators. The analysis was examined to evaluate 1 to 7 solutions, and several criteria were utilised to decide the number of latent profiles: the Akaike information criterion (AIC), the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the adjusted BIC (aBIC), the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin Adjusted LRT (aLRT), and the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT; Nylund et al., Citation2007). Entropy and average latent class probabilities were conducted to evaluate several solutions. In order to take into account longitudinal data on the same participants at both time points using the same instrument, the correlations between CLE (T1) with CLE (T2) and REF (T1) with REF (T2) were utilised in latent profile analysis.

The development of the teachers’ sense of professional agency within the profiles was further examined using paired-samples t-tests and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, with the most likely class membership as a grouping variable. The association between teachers’ sense of professional agency profiles and teacher stress, attrition intentions, teacher groups and school size were examined using Fisher’s exact test. The reason for using Fisher’s exact test was the very small size of the low sense of professional agency profile. Fisher’s exact test is more valid than the Chi-square test, especially when the cells are small (Mehta & Patel, Citation1983).

Results

The study investigated the individual differences and changes in teachers’ sense of professional agency, and the interrelations between their sense of professional agency profiles and the background variables in a five-year follow-up. The correlations, sample means, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values of the scale are presented in .

Table 2. Correlations, means, standard deviations and minimum and maximum of the scale.

The teachers perceived their ability to reflect in the classroom (REF) as rather high (T1: M = 6.09; T2: M = 6.13). Their perceived ability to reflect remained relatively stable, because there was no statistically significant difference between it at the two measurement points (t(200) = −1.08, p > .05). The teachers also perceived their capacity to build a collaborative environment (CLE) as relatively high, but lower than their ability to reflect (REF) at both measurement points (T1: M = 5.34; T2: M = 5.60). Their perceived capacity to build a collaborative learning environment increased statistically significantly during the five-year follow-up (t(200) = −6.36, p < .001). The correlations between reflection and the collaborative environment were statistically significant (p < .01) in a prospective direction.

Selection of best latent profile solution

Our analysis of the teachers’ sense of professional agency showed a decreasing AIC and aBIC, which suggested that the model fit improved with each additional model (see, ). Moreover, the BLRT revealed that the fit increased when a new latent class was added to the one-to-seven class solution. The BIC value decreased until the three-class solution, indicating that the three-class model was better than the other solutions. The VLMR and aLRT showed that the two-class model was not better than the one-class model, and the three-to-seven class model did not improve the fit from the two-to-six class model. Thus, no class was chosen as the best on the basis of the VLMR and aLRT (Berlin et al., Citation2014). Of the statistical criteria, BIC is considered the best indicator for determining the number of classes with BLRT (Nylund et al., Citation2007). On the basis of the statistical criteria, we selected the three-class model as the latent profile solution. The class sizes in the three-class model were sufficient and revealed adequate separation between the classes according to average latent class probabilities (0.87, 0.88, 0.96) and entropy value (0.84).

Table 3. The latent profile solutions in class 1 to 7.

Teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom profiles

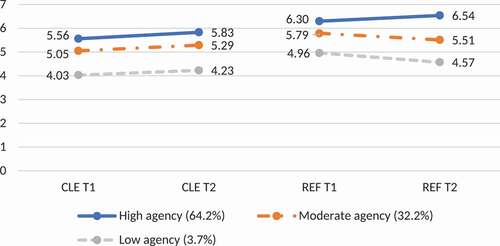

Three sense of professional agency in the classroom profiles were identified (): 1) a high sense of professional agency, 2) a moderate sense of professional agency, and 3) a low sense of professional agency. The first latent profile culled from our analysis was named a high sense of professional agency. It was the most common profile among the teachers, with a 64.2% (n = 129) sample share. Teachers belonging to the high sense of professional agency profile showed the highest perceived professional agency in both components of transforming their actions and pedagogical practices (CLE) and reflecting (REF) at two measurement points among the three sense of professional agency in the classroom profiles. Accordingly, they reported constructing a reciprocal learning environment to adapt their environment and teaching practices by building a functional relationship with their pupils (CLE). They also considered pupils a resource for improving teaching practices and find ways to engage them all in supporting their overall development (CLE). At the same time, they perceived that they were deliberately learning by reflection, such as regularly evaluating the success of their pedagogical practices, continuously learning from teaching, and thoroughly understanding pupils’ ways of thinking to help them act in a better way (REF).

Figure 1. Profiles of perceived professional agency in terms of the collaborative environment and transformative practice (CLE) and reflection in classroom (REF) at two time points.

The moderate sense of professional agency profile accounted for 32.2% of the sample (n = 65). In terms of constructing collaborative environments (CLE) and reflecting in the classroom (REF), the teachers in the moderate sense of professional agency profile had a lower perception of their capacity than those in the high sense of professional agency profile, and a higher perception than those in the low sense of professional agency profile, at both time points. Accordingly, they showed moderate levels of perception of developing their understanding of pupils and developing their abilities to teach and learn (REF). They also reported moderate levels of building a collaborative environment, including building a reciprocal process and supporting the learning of all pupils (CLE).

A few teachers held a low sense of professional agency profile (3.7%; n = 7). These teachers considered their ability to create collaborative environments and their perception of reflection to be the lowest among the three profiles, with scores slightly above the average at both time points. Hence, compared to the other two profiles, they were less confident about constructing interactive relationships and atmospheres and were less likely to engage different groups of pupils and use them as a resource to promote their learning (CLE). They were also less likely to deliberately observe improvement in their learning and teaching (REF).

The mean differences between the three profiles were statistically significant. Accordingly, the teachers in the different sense of professional agency profiles differed from each other in both their ability to construct collaborative environments and in reflection.

Development of teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom within the profiles

As shown in , the teachers employing a high sense of professional agency profile showed the greatest change in their perceived professional agency, with a statistically significant increase in their perception of the collaborative learning environment and in reflection (CLE: t(130) = −5.59, p < .001, d = 0.49, M (T1) = 5.56, M (T2) = 5.83; REF: t(130) = −5.02, p < .001, d = 0.44, M (T1) = 6.30, M (T2) = 6.54) during the five-year follow-up. Accordingly, the teachers who already had a high sense of professional agency in the induction phase further improved their perception of reflection for learning and engagement in reciprocal learning and displayed transformative pedagogical activities later in their teaching careers.

Teachers holding the moderate sense of professional agency profile statistically significantly increased their perception of constructing a collaborative environment between the two measurement points (CLE: t(62) = −3.42, p < .01, d = 0.43, M (T1) = 5.05, M (T2) = 5.29). In turn, their perception of reflection decreased statistically significantly (REF: t(62) = 3.76, p < .001, d = 0.47, M (T1) = 5.79, M (T2) = 5.51). Thus, the teachers with a moderate sense of professional agency gained a more balanced perception of their ability to construct a collaborative environment and transform their actions, whereas their perceived reflective practices decreased.

The teachers in low sense of professional agency profile did not reveal any statistically significant changes in either the components of professional agency in the perception of collaborative learning environment or in reflection (CLE: Z = −0.63, p > .05, r = −0.24, M (T1) = 4.03, M (T2) = 4.23; REF: Z = −0.84, p > .05, r = −0.32, M (T1) = 4.96, M (T2) = 4.57). Accordingly, the teachers with a low sense of professional agency had stable experiences of professional agency, their perception of teaching as a collaborative and transformative process increased slightly, and their learning from continuous reflection on their teaching experiences decreased slightly.

To sum up, the teachers with a high sense of professional agency profile showed the highest perceived professional agency in both components of professional agency, whereas the teachers with a moderate and low sense of professional agency profile were characterised by the moderate and the lowest level of collaborative learning and reflection of the three professional agency profiles at both measurement points. Moreover, all three profiles, including the high, moderate and low sense of professional agency profiles, increased their perceptions of collaborative learning and transformative practices during the five-year follow-up, although their degree of increase varied. Specifically, both the high and moderate sense of professional agency profiles experienced a statistically significant increase in creating a collaborative learning environment, whereas no such change was detected in the low sense of professional agency profile. However, with regards to reflection, a statistically significant increase was only detected in the high sense of professional agency profile. In turn, a statistically significant decrease in reflection was identified in the moderate sense of professional agency profile. There was no statistically significant change in reflection in the low sense of professional agency profile between the two time points.

Association with teacher stress, attrition intentions, teacher groups, and school size

The results showed that the three sense of professional agency profiles were associated with the teacher groups (Fisher’s exact test, p < .05). Specifically, the teachers in the low sense of professional agency profile differed from their colleagues in the moderate or high sense of professional agency profiles in terms of teacher group (i.e., primary teachers, subject teachers, and special education teachers) over the five-year follow-up. Further investigation showed that subject teachers were overrepresented and special teachers were underrepresented in the low sense of professional agency profile. However, it should be noted that the size of the low sense of professional agency profile was very small (n = 7). The profiles were not associated with teacher stress, attrition intentions or school size.

Discussion

Findings in light of previous literature

Three distinctive sense of professional agency profiles employed by early career teachers were identified, including a high sense of professional agency, a moderate sense of professional agency and a low sense of professional agency. Most of the teachers hold either a high or moderate sense of professional agency profile, implying that most of the teachers had already developed a strong perception of active professional learning ability in their initial five years of teaching (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2015; Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012). This finding contradicts the results of some prior studies that suggest that early career teachers may have difficulties in their professional transition and may be less capable of regulating their learning (Hobson et al., Citation2009; Hogan et al., Citation2003) due to praxis shock (Kelchtermans & Ballet, Citation2002). The reason might be that the Finnish education system where early career teachers work has high degree of autonomy, research-based teacher training, and a culture of support and trust (Sahlberg, Citation2010, Citation2011; Tirri, Citation2014). Accordingly, it seems that teachers’ sense of professional agency is complex and thus cannot be explained by only the challenges of the initial years. Although only a few teachers belonged to the low sense of professional agency profile, variations between teachers in this regard existed: some teachers were more confident in their capacity for active learning than their colleagues. This finding may suggest that the learning environment offered by teacher education and the work environment provided by schools cultivate early career teachers’ sense of professional agency to different extents (Bakkenes et al., Citation2006; Toom et al., Citation2017).

Also, variations between the modes of sense of professional agency were detected. The teachers in all three profiles scored higher in their perception of capacity to reflect in the classroom (REF) than in building a collaborative environment (CLE). This implies that the teachers were accustomed to reflecting for developing their teaching skills. However, they were less confident in their ability to promote instruction as a reciprocal process. One reason for this might be that in Finland, reflection is emphasised in teacher development from the beginning of teacher education (Tirri, Citation2014). For example, all teacher education programmes focus on developing student teachers’ reflection and critical thinking (Tryggvason, Citation2009). On the other hand, constructing a collaborative climate (CLE) is more challenging than reflection in classroom (REF) due to its inter-individual nature (Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted). Moreover, displaying a high level of intra- and inter-individual processes (i.e., REF and CLE) at the same time would be a highly challenging task. This would require time, intentional efforts, and changes of practice in both modes simultaneously (Pietarinen et al., Citation2016; Soini et al., Citation2016).

Somewhat surprisingly, our results showed that the three sense of professional agency profiles were not associated with stress, attrition intentions or school size, which implies that these factors do not play a key role in teachers’ sense of professional agency. This result contradicts previous studies suggesting that teacher stress, attrition intentions and situational factors (i.e., school size) are related to teachers’ sense of professional agency (Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Oosterheert & Vermunt, Citation2001; Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). This might be because most teachers had a relatively high sense of professional agency. Thus, they are more likely to be capable of intentionally managing new learning, and less likely to be influenced by stress, attrition intentions and school size. In addition, previous studies have mainly used a variable-centred approach, whereas we adopted a person-centred approach (Laursen & Hoff, Citation2006). The indicative result also showed that the three sense of professional agency profiles were associated with teacher groups. This finding is in line with those of earlier studies indicating that primary teachers differ from secondary (subject) teachers and special education teachers in professional agency (Munthe, Citation2001; Pyhältö et al., Citation2012). A reason for this may be that primary teachers are more encompassing, and secondary teachers are more subject-oriented. However, the number of teachers in the low sense of professional agency profile was low, and further studies are needed to examine the relation between the sense of professional agency profiles and teacher groups.

Some changes and stabilities were detected during the five-year follow-up in the three profiles. The high sense of professional agency profile holders’ sense of agency increased in both modes, while only an increase in the collaborative environment was detected among moderate sense of professional agency profile holders. This implies that the early career teachers in both profile groups have had a chance to cultivate and exercise their agency successfully (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, Citation2011; Spilt et al., Citation2011), and the inter-individual component of professional agency (i.e., CLE) seems to be more important than its intra-individual component (i.e., REF) in terms of developing teachers’ sense of professional agency (Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted). This result is in line with previous findings that suggest that student teachers’ sense of professional agency can be enhanced by building a collaborative learning environment (Pyhältö et al., Citationsubmitted; Kwakman, Citation2003; Spilt et al., Citation2011). However, at the same time, perception of reflection decreased among those in the moderate sense of professional agency profile. This suggests that the two modes of sense of professional agency can have different developmental paths, which means that the development of the sense of professional agency might not be linear. This finding is partly in line with a previous longitudinal study that found the positive relationship between student teachers’ perceived ability to construct collaborative environments and their capacity to critically analyse pedagogical interaction decreased during the second study year (Heikonen et al., Citation2020). This result also indicates that perceived capacity to reflect does not optimally facilitate teachers’ sense of professional agency, especially among teachers with a moderate or low sense of professional agency, although reflection was at a higher level than collaborative learning in both profiles, and reflection has been identified as key for teacher learning (Lohman, Citation2006). Hence, the development of teachers’ sense of professional agency seems to be relational (e.g., Edwards, Citation2005) and requires not only reflection on their own learning but also active intentions to modify their own teaching by using pupil feedback and initiatives as a resource for their professional development. However, although teachers’ sense of professional agency may not be influenced in the short term, it might be negatively influenced in the future if their perceived reflection declines. In turn, the low sense of professional agency profile remained rather stable and did not experience a statistically significant increase or decrease in collaborative learning and reflection over time. This implies that the teachers in this profile may find it more difficult to develop their sense of professional agency.

Practical implications

The study revealed that there are individual variations in teachers’ perceptions and developmental paths in their professional agency. This means that maintaining and cultivating teachers’ sense of professional agency entails continuing efforts during the early years and even afterwards (Pyhältö et al., Citation2014). First, the results imply that it would be important to identify teachers with different perceptions of professional agency and help them gain a better understanding of their own capacity to actively learn at the beginning phase. Therefore, schools can provide more support for teachers with a low sense of professional agency and these teachers can learn from their counterparts with a high sense of professional agency and focus on the modes in which they are not confident and continuously develop their professional agency for their future career. For instance, schools could offer a collaborative and supportive environment where teachers can learn from each other in everyday pedagogical practices (Aspfors & Bondas, Citation2013). Moreover, individual teachers may need different forms of support for developing their sense of professional agency. Thus, it would be useful to identify personal learning paths and offer special support to facilitate teachers’ sense of professional agency (Muir et al., Citation2010). In practice, this means applying strategies to enable teachers to become aware of their personalised learning patterns and helping them reflect on their learning to develop their professional agency. For example, it would be beneficial to organise learning activities in guiding and supporting teachers’ self-evaluation of their professional agency and its development in terms of all components in the classroom (i.e., CLE and REF).

Furthermore, the teachers scored exceptionally highly in reflection (REF), whereas they were less confident in collaborative environments (CLE). This implies that the pedagogical tools are needed for improving teachers’ capacity to construct a collaborative environment and enact transformative practices (Rigelman & Ruben, Citation2012; Servage, Citation2008). Accordingly, our findings imply that it is important not only to identify individual teacher learning patterns but also to find multiple ways in which to support their sense of professional agency. This means that facilitating the simultaneous management and integration of pedagogical theories and practices would develop both modes of sense of professional agency efficiently at the same time.

Methodological reflection and directions for future research

This study utilised a person-oriented approach to analyse longitudinal data. This approach enabled us to explore both individual variation and the development of sense of professional agency by extracting latent profiles among teachers. However, as the model selection in latent profile analysis was not straightforward and the size of the low sense of professional agency profile group was small, and therefore the final latent profiles were exploratory and need further investigation in the future. In addition, the person-centred approach cannot detect causal inference in the relationships between the sense of professional agency profiles and background variables. More research with a longitudinal design would be needed to further examine the changes in teachers’ sense of professional agency and its associations with stress, attrition intentions, teacher groups, and school size.

The national sample consisted of teachers at different career phases. It was collected using a probability sampling method, and the sample was representative (Pietarinen et al., Citation2013). In this study, the sample included teachers with 0–5 years of teaching experience, and special education teachers and female teachers were slightly overrepresented. Moreover, as the self-report data only covered teachers’ perceptions of professional agency, it did not reveal their real ability to enact professional agency. Thirdly, we examined the development of sense of professional agency at only two measurement points, thus one should be careful about drawing conclusions based on the observed development. It would be useful to have at least three measurement points to explore the development of teachers’ sense of professional agency. Finally, although the construct validity of the scale was adequate in this study, and had been tested in previous studies (e.g., Heikonen et al., Citation2017; Pietarinen et al., Citation2016), the scale needs to be further constructed. It might be beneficial to test the validity of the scale in other cultural contexts to explore the differences and similarities in the construction of professional agency. The McDonald’s omega of reflection in the classroom at the measurement point 2 was not very high but closed to the cut-off point (Hair et al., Citation2010). Thus, the reliability of the scales could be improved by developing new items for the two components of professional agency in the classroom.

In the future, more longitudinal studies will be needed to further investigate the development of the sense of professional agency through surveys as well as focus-group interviews or semi-structured interviews over longer periods that capture the transition from early career teachers to more experienced teachers. This would improve our understanding of the changes in teachers’ professional agency and the inner processes of teachers during this transition. Longitudinal studies focusing on the interrelation of the elements of teacher learning among teachers are also needed. This would expand our understanding of the role of and the relations between the components in the development of the sense of professional agency.

Conclusion

The results showed that most of the teachers had already developed a strong sense of professional agency in the classroom. However, individual variations among early career teachers, in terms of their perception of professional agency, were detected. Three sense of professional agency profiles were identified, including a high, moderate and low sense of professional agency. Furthermore, some changes and stabilities in the three profiles were detected during the five-year follow-up. These sense of professional agency profiles were not associated with stress, attrition intentions or school size, whereas the profiles were associated with teacher groups (i.e., primary teachers, subject teachers, and special education teachers).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aspfors, J., & Bondas, T. (2013). Caring about caring: Newly qualified teachers’ experiences of their relationships within the school community. Teachers and Teaching, 19(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.754158

- Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J., Wubbels, T., & Imants, J. (2006). Teachers’ perceptions of the school as a context for workplace learning [ Paper presentation]. Conference of the American Educational Research Association, San Francisco, California.

- Beauducel, A., & Wittmann, W. (2005). Simulation Study on Fit Indexes in CFA Based on Data With Slightly Distorted Simple Structure. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 12(1), 41–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1201_3

- Bergman, L. R., & Trost, K. (2006). The Person-Oriented Versus the Variable-Oriented Approach: Are They Complementary, Opposites, or Exploring Different Worlds? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52(3), 601–632. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0023

- Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A., & Parra, G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst084

- Berliner, D. C. (1986). In pursuit of the expert pedagogue. Educational Researcher, 15(7), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015007007

- Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033008003

- Bronkhorst, L. H., Meijer, P. C., Koster, B., & Vermunt, J. D. (2011). Fostering meaning-oriented learning and deliberate practice in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(7), 1120–1130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.05.008

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

- Clark, S. K. (2020). Examining the development of teacher self-efficacy beliefs to teach reading and to attend to issues of diversity in elementary schools. Teacher Development, 24(2), 127–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2020.1725102

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). Teacher learning that supports student learning. In B. Z. Presseisen (Ed.), Teaching for Intelligence (pp. 91–100). Corwin.

- Day, C., & Smethem, L. (2009). The effects of reform: Have teachers really lost their sense of professionalism? Journal of Educational Change, 10(2–3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9110-5

- Day, C. (2021). The new Professionalism? How good teachers continue to teach to their best and well in challenging reform contexts. In E. Kuusisto, M. Ubani, P. Nokelainen, & A. Toom (Eds.), Good Teachers for Tomorrow’s Schools: Purpose, Values, and Talents in Education (pp. 37–56). Brill.

- Edwards, A., & D’arcy, C. (2004). Relational agency and disposition in sociocultural accounts of learning to teach. Educational Review, 56(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031910410001693236

- Edwards, A. (2005). Relational agency: Learning to be a resourceful practitioner. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(3), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2006.06.010

- Edwards, A. (2007). Relational agency in professional practice: A CHAT analysis. Actio: An International Journal of Human Activity Theory, 1, 1–17.

- Elo, A.-L., Leppänen, A., & Jahkola, A. (2003). Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 29(6), 444–451. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.752

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023. https://doi.org/10.1086/231294

- Engeström, Y. (2005). Developmental work research: Expanding activity theory in practice. Lehmanns Media.

- Eraut, M. (1995). Schon Shock: A case for refraining reflection-in-action? Teachers and Teaching, 1(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060950010102

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., & Hökkä, P. (2015). How do novice teachers in Finland perceive their professional agency? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 660–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044327

- Fantilli, R. D., & McDougall, D. E. (2009). A study of novice teachers: Challenges and supports in the first years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(6), 814–825. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.021

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2014). A draft of the national core curriculum for basic education. http://www.oph.fi/ops2016

- Flores, M. A. (2005). Mapping new teacher change: Findings from a two-year study. Teacher Development, 9(3), 389–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530500200274

- Gordon, S. C., Dembo, M. H., & Hocevar, D. (2007). Do teachers’ own learning behaviors influence their classroom goal orientation and control ideology? Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2004.08.002

- Greeno, J. G. (2006). Authoritative, accountable positioning and connected, general knowing: Progressive themes in understanding transfer. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 15(4), 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1504_4

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis. Pearson Education (Prentice-Hall), Inc.

- Hansén, S.-E., & Eklund, G. (2014). Finnish teacher education – Challenges and possibilities. Journal of International Forum of Researchers in Education, 1(2), 1–12.

- Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., & van Veen, K. (2018). The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teachers and Teaching, 24(6), 626–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1465404

- Hatton, N., & Smith, D. (1995). Reflection in teacher education: Towards definition and implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 11(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00012-U

- Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use Omega Rather than Cronbach’s Alpha for Estimating Reliability. But…. Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

- Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Toom, A., & Soini, T. (2017). Early career teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom: Associations with turnover intentions and perceived inadequacy in teacher–student interaction. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 45(3), 250–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2016.1169505

- Heikonen, L., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2020). The development of student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom during teacher education. Learning: Research and Practice, 6(2), 114–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2020.1725603

- Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., & Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001

- Hogan, T., Rabinowitz, M., & Craven, J., III. (2003). Representation in teaching: Inferences from research of expert and novice teachers. Educational Psychologist, 38(4), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3804_3

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jääskelä, P., Poikkeus, A., Häkkinen, P., Vasalampi, K., Rasku-Puttonen, H., & Tolvanen, A. (2020). Students’ agency profiles in relation to student-perceived teaching practices in university courses. International Journal of Educational Research, 103, 101604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101604

- Kansanen, P. (2014). Teaching as a Master’s level profession in Finland: Theoretical reflections and practical solutions. In O. McNamara, J. Murray, & M. Jones (Eds.), Workplace learning in teacher education. Professional learning and development in schools and higher education (pp. 279–292). Springer.

- Kelchtermans, G., & Ballet, K. (2002). The micropolitics of teacher induction. A narrative-biographical study on teacher socialisation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00053-1

- Kenny, D. A. (2020). Measuring model fit. Retrieved from http://davidakenny.net/cm/fit.htm

- Klassen, R., Wilson, E., Siu, A. F. Y., Hannok, W., Wong, M. W., Wongsri, N., Sonthisap, P., Pibulchol, C., Buranachaitavee, Y., & Jansem, A. (2013). Preservice teachers’ work stress, self-efficacy, and occupational commitment in four countries. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(4), 1289–1309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0166-x

- Korthagen, F. (2010). Situated learning theory and the pedagogy of teacher education: Towards an integrative view of teacher behavior and teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.05.001

- Kwakman, K. (2003). Factors affecting teachers’ participation in professional learning activities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00101-4

- Laursen, B., & Hoff, E. (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52(3), 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0029

- Lavigne, A. L. (2014). Beginning teachers who stay: Beliefs about students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 39, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.12.002

- Lavonen, J. (2016). Educating professional teachers through the master’s level teacher education programme in Finland. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 68(2), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.13042/Bordon.2016.68204

- Lipponen, L., & Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: Creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 812–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001

- Lohman, M. C. (2006). Factors influencing teachers‘ engagement in informal learning activities. Journal of Workplace Learning, 18(3), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/13665620610654577

- Loughran, J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487102053001004

- McDonald, R. P. (1982). Linear versus models in item response theory. Applied Psychological Measurement, 6(4), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168200600402

- Meade, A. W., Johnson, E. C., & Braddy, P. W. (2008). Power and sensitivity of alternative fit indices in tests of measurement invariance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(3), 568–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.568

- Mehta, C., & Patel, N. (1983). A network algorithm for performing Fisher’s exact test in r × c contingency tables. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 78 (382), 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1983.10477989

- Mena, J., Hennissen, P., & Loughran, J. (2017). Developing pre-service teachers‘ professional knowledge of teaching: The influence of mentoring. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.024

- Meristo, M., & Eisenschmidt, E. (2014). Novice teachers’ perceptions of school climate and self-efficacy. International Journal of Educational Research, 67, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2014.04.003

- Muir, T., Beswick, K., & Williamson, J. (2010). Up, close and personal: Teachers‘ responses to an individualised professional learning opportunity. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 38(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598661003677598

- Munthe, E. (2001). Professional Uncertainty/Certainty: How (un)certain are teachers, what are they (un)certain about, and how is (un)certainty related to age, experience, gender, qualifications and school type? European Journal of Teacher Education, 24(3), 355–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760220128905

- Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2015). Mplus users guide (8th ed.). Muthen and Muthen.

- Naidoo, K., & Kirch, S. A. (2016). Candidates use a new teacher development process, transformative reflection, to identify and address teaching and learning problems in their work with children. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(5), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116653659

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Oosterheert, I. E., & Vermunt, J. D. (2001). Individual differences in learning to teach: Relating cognition, regulation and affect. Learning and Instruction, 11(2), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(00)00019-0

- Pallant, J. (2001). SPSS survival manual. Open University Press.

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., Soini, T., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Reducing teacher burnout: A socio-contextual approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 62–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.05.003

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., & Soini, T. (2016). Teacher’s professional agency - A relational approach to teacher learning. Learning: Research and Practice, 2(2), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2016.1181196

- Pillen, M., Beijaard, D., & den Brok, P. (2013). Tensions in beginning teachers’ professional identity development, accompanying feelings and coping strategies. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 240–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2012.696192

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2012). Do comprehensive school teachers perceive themselves as active professional agents in school reforms? Journal of Educational Change, 13(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9171-0

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2014). Comprehensive school teachers’ professional agency in large-scale educational change. Journal of Educational Change, 15(3), 303–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-013-9215-8

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers’ professional agency and learning – From adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., Haverinen, K., Beijaard, D., & Soini, T. (submitted). Trajectories of secondary teacher students’ professional agency in classroom. European Journal of Teacher Education.

- Rigelman, N. M., & Ruben, B. (2012). Creating foundations for collaboration in schools: Utilizing professional learning communities to support teacher candidate learning and visions of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(7), 979–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.004

- Sahlberg, P. (2010). Rethinking accountability in a knowledge society. Journal of Educational Change, 11(1), 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9098-2

- Sahlberg, P. (2011). The fourth way of Finland. Journal of Educational Change, 12(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-011-9157-y

- Servage, L. (2008). Critical and transformative practices in professional learning communities. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(1), 63–77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23479031

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., Toom, A., & Pyhältö, K. (2015). What contributes to first-year student teachers’ sense of professional agency in the classroom? Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044326

- Soini, T., Pietarinen, J., & Pyhältö, K. (2016). What if teachers learn in the classroom? Teacher Development, 20(3), 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511

- Spilt, J., Koomen, H., & Thijs, J. (2011). Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher–Student Relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 23(4), 457–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

- Stein, M. K., & Wang, M. C. (1988). Teacher development and school improvement: The process of teacher change. Teaching and Teacher Education, 4(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(88)90016-9

- Tirri, K. (2014). The last 40 years in Finnish teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(5), 600–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2014.956545

- Toom, A., Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2017). How does the learning environment in teacher education cultivate first year student teachers‘ sense of professional agency in the professional community? Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.013

- Tryggvason, M.-T. (2009). Why is Finnish teacher education successful? Some goals Finnish teacher educators have for their teaching. European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(4), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760903242491

- Van Eekelen, I. M., Vermunt, J. D., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2006). Exploring teachers’ will to learn. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22(4), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.12.001

- Virtanen, T., Vaaland, G. S., & Ertesvåg, S. K. (2019). Associations between observed patterns of classroom interactions and teacher wellbeing in lower secondary school. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 240–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.10.013

- Voss, T., & Kunter, M. (2020). “Reality Shock” of Beginning Teachers? Changes in Teacher Candidates’ Emotional Exhaustion and Constructivist-Oriented Beliefs. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(3), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487119839700

- Webb, R., Vulliamy, G., Hämäläinen, S., Sarja, A., Kimonen, E., & Nevalainen, R. (2004). A comparative analysis of primary teacher professionalism in England and Finland. Comparative Education, 40(1), 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006042000184890

- Wheatley, K. F. (2005). The case for reconceptualizing teacher efficacy research. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(7), 747–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.009

- Wubbels, T., & Brekelmans, M. (2005). Two decades of research on teacher-student relationships in class. International Journal of Educational Research, 43(1–2): 6–24.