ABSTRACT

The turn of the nineteenth century witnessed a rise in fashion and ladies’ magazines across Europe. With an emerging consumer culture and the rise of the middle class, these magazines offer glimpses into important societal changes. A new gender order was being established, and magazines were one area where developing gender values were articulated. Setting out from the Swedish magazine Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder, this article analyses gender-related values, focusing on the importance of being fashionable and on amorous liaisons and marriages. The results show a distinct ambiguity in values, with contradictory images of women’s ideal behaviour, and the international influence on the making of a Swedish middle class.

In June 1828, number six of the eleventh issue of the Swedish journal Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder [Magazine for Art, News and Fashion] was published.Footnote1 As usual, it offered a broad range of topics. There was an article on the ‘road under the river Thames’, including drawings on the construction of the tunnel; Norwegian poetry (probably of German origin); fashion news from Paris about women’s colours, hats, and dresses and men’s coiffure, buttons, and costumes; a colour fashion plate showing hats and coiffure for women; and the probably much longed-for outcome of the serial A year in a young girls life.

This was nothing new in Europe; magazines like this were already well established. Lady’s Magazine (1770–1832) in England, Journal des Luxus und der Moden (1786–1826) in Germany, and Journal des Dames (1759–1778) and Journal des Dames et des Modes (1797–1839) in France are but a few examples.Footnote2 But for a Swedish audience outside the royal court and the very highest social echelons, it represented something innovative and qualitatively new. In addition, it integrated the Swedish readers in a pan-European cultural sphere.

The development of fashion magazines capture two essential and closely intertwined historical processes, both with gender in focus: the emergence of a consumer culture and the rise of a middle class.Footnote3 As Daniel Purdy emphasised, the importance of journals to the upcoming middle class (or Bildungsbürgertum) must not be underestimated.Footnote4 The journals provided a public sphere away from the princely courts in which a ‘bourgeois consumer culture’ could develop. Furthermore, the journals were part of the cultural entertainment essential, according to Karin Wurst, for the self-definition and lifestyle of the middle class.Footnote5 Both Purdy and Wurst stress the ‘identificatory reading’ of the journals as representative of the middle class, implying that the worldview and values conveyed in journals could be easily adopted by the reader.Footnote6

Gender-related values were embedded in most elements of the new bourgeoise identity (captured by Woodruff Smith in the concept of ‘respectability’), especially ‘domestic femininity’ and ‘rational masculinity’.Footnote7 As a result, the female was separated from the male, and a clear distinction was established between private feminine and public masculine spheres. In her study on gender and fashion in Germany, Katherine Aaslestad shows that fashion journals illustrate ‘the extreme tensions and fractures in gender constructions’ at the turn of the nineteenth century.Footnote8

These processes occurred all over Europe during the late seventeenth, the eighteenth, and the early nineteenth centuries. The spread of a middle class ideology or identity was facilitated by the rise of printed material promoting a bourgeois feminine ideology of domesticity.Footnote9 The role of fashion and fashion magazines in creating a feminine identity was immense. For today’s readers and researchers, these magazines are an important source for understanding a society in transition.Footnote10 Hitherto, such research has primarily focused on separate magazines or specific countries. For British magazines – and Lady’s Magazine in particular – Margaret Beetham and Jennie Batchelor have done groundbreaking research on how women used and were affected by the magazines, including their fashion advice, literary content, support of various educational aspirations, and their omnipresent ideology of domesticity.Footnote11 The German Journal des Luxus und der Moden has been thoroughly analysed by Daniel Purdy, Karin Wurst, and Michael North, who all see the magazine as part of a larger cultural discourse and emphasise the rising culture of consumption.Footnote12 Rebecca Messbarger has stressed the importance of magazines as an alternative public discourse for women in Italy.Footnote13

Despite these important studies, considering the complexity of the content and the possibilities inherent in comparisons over time and place, the magazines have still received surprisingly little analysed attention. Jane Taylor says they have been ‘largely overlooked by historians and literary critics’.Footnote14 The situation is even worse for Swedish magazines, which Leif Runefelt writes are ‘severely understudied’.Footnote15 Systematic comparisons between magazines from different countries, including those on the periphery of greater centres, can provide a more comprehensive picture of the European public consumer discourse and its implication for gender order. The need for a larger geographical scope has recently been emphasised by Peter McNeil, who calls for fashion studies to ‘shift beyond the standard Anglo–French comparative models’.Footnote16 Similar arguments are presented in Alexander Maxwell’s study on European clothing and nationalism. Too often, he says, London and Paris have been seen as ‘Europe’, rather than as the exceptions in European fashion culture that they are.Footnote17 This opinion is echoed by Mikael Alm in his work on sartorial practices in Sweden and the northern European context.Footnote18 An analysis of Magasin för konst nyheter och moder increases our knowledge about Swedish periodicals per se and contributes to the discourse on gender and fashion in the periphery of Europe. It also enables us to test assumptions about the dominance of English and French magazines.

Similar to the pocket books in Arlene Leis’ research, Magasin enabled its female readers to construct and develop an identity around fashion, domesticity, and (as emphasised by Karin Wurst), bourgeois gender-related values.Footnote19 The dual aims of this article are (1) to explicate the evolving culture of fashion in Sweden in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century fashion magazines and (2) to relate it to the culture of domesticity embedded in most of the content, especially in relation to love and marriage. I will do this by analysing both fashion plates and reports, and serials and fiction, which are the parts of the magazine most concerned with gender conceptions, and probably also the most popular ones amongst readers. The inclusion of both parts allows for a broader perspective of gender values than would an analysis of fashion or serials.

Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder

This magazine had high expectations and very high standards. It was unique in the Swedish context, not only because it was published in Swedish and ran for more than two and a half decades, but also because of its varied content and lavish illustrations, often in colour. It was a one-man project, established and edited by Baron Fredrik Boije, often referred to as ‘Boije’s magazine’.Footnote20 Magasin was published monthly and each issue contained 8 pages (increasing to 16 in 1836), plus additional plates in colour or black and white. It was only available through subscription and had approximately 500 subscribers (mostly men) from the royal court, the nobility, the ranking military, the middle class, and some booksellers.Footnote21 Some people signed up for several subscription, among them the royal family (33 subscriptions) and a managing director/owner of a printing house (12 subscriptions). In Christiania (Oslo, Norway) and Uppsala, two booksellers subscribed for 15 and 10 copies each, which indicates that it was actively distributed or sold in wider circles.Footnote22 The number of subscribers is surprisingly high, if compared with the 1,488 subscribers for Journal des Luxus und der Moden, but low compared with the 15,000 monthly copies for Lady’s Magazine.Footnote23 The circle of readers was, of course, much larger than the number of copies, not least because of widespread sharing and booksellers’ sales.Footnote24

Like the European magazines, Magasin provided its readers with greatly varied content.Footnote25 Apart from fashion reports and coloured fashion plates, there were articles on art, literature, and music; architecture and interior design; entertainment and royal ceremonies; shorter biographies (both historical and contemporary), travel reports, various reflections, and serialised stories.Footnote26 Many items and articles, such as patterns for needlework, correspondence, and romantic stories, were explicitly aimed at a female audience. Remarkable were the numerous biographies of prominent women, such as writers, actors, singers, regents, adventurers, or merely celebrities, often accompanied by a miniature portrait.Footnote27 Several articles reported news or told stories about other countries in Europe and faraway places, probably the effect of many articles from other sources translated into Swedish, usually from the French.Footnote28 Thus, Magasin allowed its readers to travel imaginatively all around the world, to encounter different kinds of celebrities, to learn about literature and stage plays, and to take part in the growing fashion market.Footnote29 It was a gateway into European bourgeois consumer culture, where images turned ‘onlookers into followers’ of fashion.Footnote30

Fashion, mainly clothing, but also furniture, architecture, and interior design, was the showpiece of Magasin. ‘Fashion news’ and ‘fashion costumes’ were presented in each issue, with detailed information on what (or what not) to wear, for which occasions, and by whom. Each issue also included at least one coloured fashion plate, often depicting two or three costumes and several fashion accessories. The high quality of the colour plates lent the magazine an expensive and lavish look, which the publisher pointed out at every opportunity.Footnote31 Unlike Journal des Luxus und der Moden and Lady’s Magazine, but like La donna galante ed erudite, Magasin carried no advertising,Footnote32 only occasionally providing information on where an item could be purchased in Stockholm.

Fashion in focus

The fashion presented in Magasin was international and dominantly French, or rather Parisian.Footnote33 Until the early 1830s, most featured costumes were from Paris (112 pcs; ). Vienna contributed 26 costumes, far outnumbering London (10 pcs.) and Sweden (8 pcs.). The relatively high number of Swedish costumes must be taken with a pinch of salt. Five had royal connections, including clothes for mourning, a court gala dress, and a uniform of the Royal Order of the Sword. The rest were merely half-hearted efforts to put Stockholm on the fashion map, pointing out details such as hats and headdresses that had supposedly not yet reached the French magazines.Footnote34 From 1836 onwards, no geographical attributes were included (except for a mourning costume worn at the death of the King Charles XIV John in 1844). French fashion magazines are mentioned in a few comments, and there is one reference to ‘foreign’ journals, but otherwise nothing specified the origins of the costumes.Footnote35 Judging from the images and descriptions, though, the fashion portrayed was still international, emanating from European metropolises.

Table 1. Geographic attributions of fashion plates and fashion news, Konst- och nyhetsmagasin för medborgare av alla klasser and Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder, 1818–1844 (n).

The preference for Parisian fashion was shared by German and Italian magazines. Fashion illustrations and news, alongside other articles and stories, were copied and reproduced all over Europe, which helps to explain their wide influence.Footnote36 For example, in 1827 Magasin reproduced a French fashion plate published in Petit Courier des Dames in 1826. The full-length French woman was, with only minor adjustments, copied into the Swedish magazine, where she was accompanied by a male costume of unknown provenance ( and ).Footnote37 It is clear that the engraver, in this case Fredrik Boije, could pick and choose from a variety of fashion plates, and that the news conveyed could be selected randomly, providing a bricolage of fashion.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, however, the English fashion magazines gained on the French in both Italy and Germany.Footnote38 This might also have been the case for Magasin in the late 1830s. It has been suggested that Swedish fashion magazines (in general) turned to English ones, especially Ackerman’s Repository, for inspiration, but more systematic comparisons are lacking.Footnote39 The battle between Paris and London had wider cultural implications. The Journal des Luxus made a clear distinction between an older ‘French elegance’ and the new ‘English functionality’, clearly sympathising with the latter.Footnote40 In Naples, the French style was seen as elitist, the British as more democratic; the former was embraced by the aristocracy, the latter by the intellectual elite.Footnote41 Preferences for English culture can also be seen in Magasin, not least in its highlighting of technical innovations and a much sought greater comfort in daily life. There are also traces of aspirational expressions, connecting peripheral Sweden with a leading country like England. When a London costume was introduced in 1824, it was established that English and Swedish ladies shared the virtue of being ‘domestic and exemplary mothers’.Footnote42

National fashion characteristics should not be exaggerated. To the untrained eye, national differences are hard to apprehend, as is evident in a fashion plate () depicting two costumes, one from London (left) and one from Paris (right).Footnote43 What mattered was not differences between fashions but that they stemmed from the major European fashion centres and that Sweden and other countries had access to international fashion culture. As shown by Michael North, the German territories lagged behind Western Europe in fashion, and the same can be said for Sweden.Footnote44 Furthermore, shopping was not an easy task in Stockholm. While cities like London and Paris offered abundant opportunities during the ‘consumer revolution’, Stockholm had nothing of the kind. The conditions were similar in Germany and Italy.Footnote45 Shops were scarce, and often lacked window to display the merchandise. On her journey to England in the 1780s, the Swedish noblewomen Anna Johanna Grill was much impressed by the many shops and the variety of goods displayed in the most tempting ways.Footnote46 In this context, Magasin became an important gateway to the European consumer culture and a world of shopping possibilities. Literally speaking, magazines enabled ‘surrogate shopping’ or ‘window shopping’.Footnote47

The importance of being fashionable

The fashion news provided by Magasin were comprehensive. The plates usually showed two costumes, often depicted from different angles. Details of fabrics, colours, and accessories were presented, and fabrics labelled as ‘French’, ‘Italian’, or ‘English’ further indicate an international fashion market where Italian fabrics could be used for a Parisian fashion dress. For example, in a fashion plate from 1825 (), one woman (left) is depicted wearing a delicate white dress decorated with blue ribbons and an ‘Italian’ straw hat (presented as Parisian fashion) with gauze veil and a large white rosette; her friend (right) wears a white organza dress ‘from Vienna’, with embroideries and tulle ribbons, and a blue and rose hat decorated with flowers and more ribbons. Gloves and shoes came in colours to match the outfits – yellow, white, or blue. For the summer season, lighter dress was recommended, with thinner fabric, shorter sleeves, and lighter headdresses.Footnote48

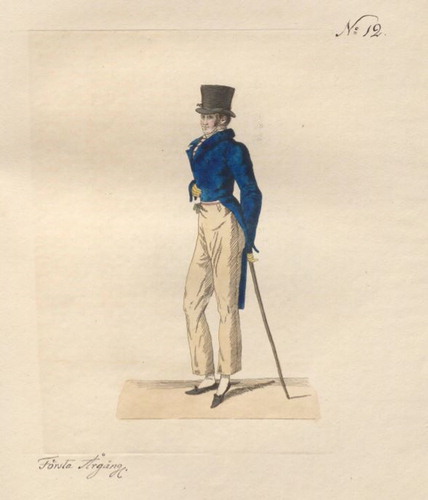

Male fashion was also quite important, though the general focus remained on female fashion.Footnote49 Male costumes were featured in about every second issue, always together with female ones, and Magasin reported on both female and male fashion trends ().Footnote50 Male dress was consistently plainer, although the finer details, such as tight sleeves, folded cuffs, tight-fitting trousers, and waistcoats with gold embroidery, were just as important as similar details in female fashion.Footnote51

This kind of information formed a vital part of what Serena Dyer has called ‘material literacy’. While there was limited practical use for information about how dresses were made, the fashion plates demonstrated the terminology and developed readers’ material vocabulary. They ‘promoted participation in a culture of material literacy’, which was a valuable supplement to the ‘haptic skills’ used/required by shoppers.Footnote52 For an audience who could not visit shops and browse finished goods, this material literacy was an important asset when deciding about fabrics and cuts.Footnote53

Changes in fashion were often limited to headdresses and coiffures, meaning an entire appearance could be changed by rather small tweaks.Footnote54 Such details were sometimes shown in several small illustrations, again from different angles. During winter–spring 1825, for example, the headdress should be in the fashionable colours of violet and blue, made of silk and velvet, and decorated with ‘rose ribbons’ and ordinary ribbons. For other hats, the yellow colour was more ‘lively’ than in earlier seasons. For a male costume, medium blue was recommended for tailcoats, the colour of ‘fresh butter’ for the piqué waistcoat, yellow cotton for trousers, and – as the finishing touch – a shining black straw hat ().Footnote55 Colours were important markers of social status.Footnote56 Apart from violet and blue, grey, dark green, and black were frequently mentioned, and lighter colours were prescribed for the summer. Ribbons were often multi-coloured, in blue and pink, blue and orange, or blue and brown.

Figure 6. Fashion plate, Konst- och nyhetsmagasin för medborgare af alla klasser 1818. Uppsala University Library.

Fashion differed slightly according to age. Specific details for younger people (of both sexes) such as different colours, fabrics, and cuts were presented. In 1818, younger gentlemen were reported to be ‘going to extremes’ by choosing trousers in grey or mixed red shades. They had also changed the shape of their hat brim, which now apparently resembled ‘the beak of a parrot’.Footnote57 Distinctions could also signal marital status. Following news from Paris in 1824, a married woman’s ball dress should be made of tulle with spangles, while an unmarried woman’s should be crepe or gauze with gold or silver decorations.Footnote58

From the pictures and descriptions in the magazines, it is possible to follow changes in fashion in detail. At the beginning, fashion and the rules around it were rather elaborate and extravagant, accompanied by adjectives such as ‘elegant’, ‘stylish’, and ‘contemporary’, but qualities such as ‘comfortable’ (Sw. bekväm) and ‘practical’ were also addressed, although rarely, indicating the establishment of new values. During the eighteenth century, the meaning of comfort came to include both material and emotional aspects, and its use in relation to fashion shows that it conveyed positive and perhaps aspirational connotations.Footnote59 References to comfort provide us with additional examples of Sweden as part of pan-European developments. Mentions of practical qualities usually referred to the Swedish climate and the need for warmer clothing in the winter. As a sartorial commentator in the late 1700s declared, ‘He who wishes to be fine-looking in French must learn to freeze in Swedish’.Footnote60 When a German ‘national dress’ was discussed in Journal des Luxus und der Moden, its adaptation to the climate was a prerequisite.Footnote61

Indirectly, the fashion plates portrayed a rich social life, with receptions, balls, theatre visits, and strolls.Footnote62 This was further emphasised by fashion and etiquette advice. A woman of fashion would need several different coats. In the morning, when she went shopping, a black silk serge coat was appropriate. For balls and suppers, a velvet coat in black or violet, trimmed with marten fur, was recommended, and for a ride in the calash, a kashmir coat in a tartan pattern. Finally, when returning home from a spectacle, a fur-lined plush coat, with a large velvet collar was suggested.Footnote63 Corresponding advice for men was also provided: in the morning, a loose dressing gown, patterned with foliage, wide trousers, yellow slippers, and a scarf and cap; during the day, a frock coat in light chestnut brown, trousers, a black, brown, or light blue scarf to match the spotted or flowered waistcoat; in the evening, a tailcoat in sky blue or green, a tight girdle, a white waistcoat, and trousers.Footnote64

Such advice is found in several journals including Journal des Luxus und der Moden, Gallery of Fashion and Cabinet des Modes.Footnote65 They presupposed a rather large wardrobe as well as active and conscious consumption, demanding time, money, and knowledge of what and where to buy or order. The European magazines clearly presented images of an ideal life consisting of little but social intercourse, in which clothes played a leading part and ordinary work had no place.Footnote66 For the traditional elite, many of these images were familiar, but their dissemination to broader circles of society encouraged a culture of consumption. Where the fashion plates provided material literacy, advice about what to wear when and where to find appropriate clothing offered readers consumer literacy.Footnote67 The aspirational aspects of this literacy should be emphasised. Not many readers would have been privileged enough to be able to afford the clothes suggested and many also lacked the opportunity to find the materials needed. However, whether you lived in Uppsala, Hereford or Arles, reading fashion advice would give you an air of metropolitan luxury; for an Uppsala reader it could also indicate inclusion in a cultural context that stretched beyond the national borders.

The Magasin was not only an eager supporter of fashion. Several articles had an educational or even critical edge. Although part of contemporary discourse, including huge debates and discussions on the perils of luxury, serious discussion in a fashion magazine is nonetheless surprising.Footnote68 Together with an illustration of ‘an elegant sofa’, the following critique was provided:

Fashion demands constant variation, not because the usual shapes are unpleasant, but you get tired of them; you want something new. This great motive provides an income for millions, and the inventiveness of duplicating all sorts of luxury items is untiring, since their demand is not always caused by need.Footnote69

These examples highlight important aspects of the fashion culture. One is the economic value of the fashion industry, which ‘provides an income for millions’. Another concerns the rapid changes in fashion, with an estimated cycle of five to seven months.Footnote71 In a satire on fashion, published in 1834, ‘the court of fashion’, as it was aptly phrased, was said to immediately revoke all decisions made, suggesting that it was impossible to keep up with the changes.Footnote72 The satire also implied that older women went out of fashion, just like the armchair. While the young presided at ‘the court of fashion’, mature women were allowed only on the back benches, and old women had no vote at all.Footnote73 There seemed to exist an upper age limit of a couple of years younger than 30 to have any part in the fashion ‘competition’.Footnote74 Fashion plates also reflected the importance of age by portraying and specifying details relevant to younger women and men.Footnote75 This preoccupation with age was a general part of the European fashion discourse, captured by the saying ‘mutton dressed as lamb’ to describe older women (mutton) acting and dressing like younger (lamb).Footnote76

Another satirical critique of fashion adopted a political tone by talking about ‘the court of fashion’, as in ‘a manifest issued by the queen of fashion’. The manifest was structured as any ordinary contemporary decree, wherein the queen announced the importance of communicating the latest fashion via journals and newspapers. The allusion to ‘la reine du monde’ (‘queen of the world’, meaning public opinion) was of course deliberate, and created a sense of inclusion in those familiar with the phrase. All suggestions from Paris, the capital of fashion, however they appeared, were to be accepted with no objections as representing the best of taste. All women were expected to wear the colours of the day, and nothing older than three months could be considered fashionable. The duties of a good husband included subscribing to at least one fashion magazine (with plates), paying for the wardrobes of his wife and daughters, and granting at least a third of his income for ballgowns and other wardrobe expenses. Any husband who violated these articles had to make amends by buying the most contemporary and elegant gift.Footnote77 A gender distinction is evident in the satire, wherein the duty of following (rather than paying for) fashion is assigned to women.

European fashion journals display an elaborate sartorial practice, dominated by cities like Paris and London. Thanks to the Magasin, Swedish readers had access to an international fashion and consumer culture. Although their material and consumer literacy could not be put into practice as it could in major centres such as London, they could still access the major elements of the accepted female identity, although it was also important that they not try too hard to please the queen of fashion. Magasin gave space to both sides. The coloured fashion plates may have been its main showpiece, but those were combined with a moralising fashion discourse on behalf of women. By the frequent use of satire and ‘neutralising’ the critique or putting it in a ‘political costume’, the Magasin walked the thin line between criticising sumptuous consumption and celebrating elegant display.Footnote78

Gender and society

The ‘fashion manifest’ addresses another prominent theme of moral conduct that ran beneath the surface of fashion magazines: marriage. Numerous references to perceptions of love and marriage and to the life courses of women and men were presented in the Magasin, in many different shapes. Marriage was, of course, not an issue only for the middle class, but a fundamental institution for the whole society and a step in one’s life course taken more or less for granted. For the middle class though, marriage embodied a shift from a traditional society organised in relation to the joining of extended families to one centred on the nuclear family and individuals, described by Jennie Batchelor as the ‘bourgeois domestic household’.Footnote79 Consequently, as shown by among others Margaret Beetham, ‘love’, ‘marriage’, and ‘sentimentalism’ rose as prominent themes in European periodical fiction.Footnote80

A moralising theme, often focused on premarital arrangements such as amorous liaisons and courtship, emerged in the magazines in articles and serials on marriage. Recent research by Batchelor and Jenny DiPlacidi has upgraded the literary qualities of the serials. The plots were often rather intricate and echoed central societal concerns, thus encouraging the reader to reflect upon the content as well as society at large.Footnote81 Serialised fiction was often the most popular part of the magazines, read by many. The illustrations accompanying many of the stories made them stand out and would most certainly have drawn readers’ attention.Footnote82 The genre often depicted highly dramatised characters, intricate plots, and settings, thus highlighting underlying (gendered) values.Footnote83 These qualities also underlined the educational or cultivating purpose of the periodicals.Footnote84 Echoing the concept of ‘material literacy’ seen in the fashion pages, serialised fiction could be said to aim at instilling marital or moral literacy.

In A Year in a Young Girl’s Life, the reader meets young Clothilda, daughter of a respected burgher, whose fate after several illustrated instalments was published in June 1828.Footnote85 The story, introduced as ‘taken from everyday life’, includes a moral twist and a not-too-tragic ending, indicating its educational purpose. Having the education and manners appropriate to her sex and class, Clothilda is much respected and loved. She is described as diligent and industrious, with a light-hearted nature and sensational beauty. She is also – very importantly – completely ‘inexperienced’.

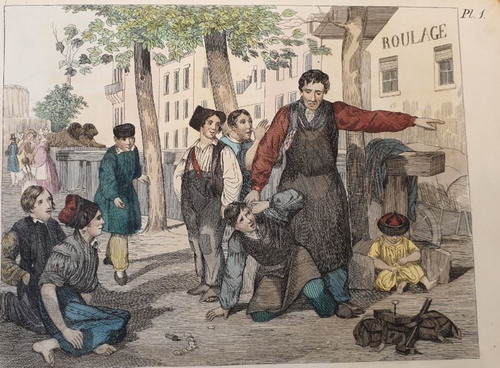

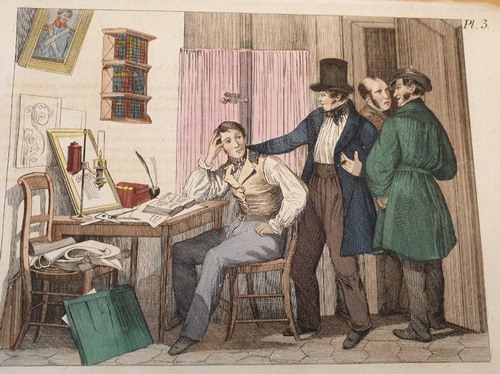

Each instalment’s illustration contained a short caption, that, put together, makes it easy to follow and summarise the course of events (). Clothilda was courted by a young man, Carl, described as good looking and so used to amorous courtships that he was bored by ‘easy victories’. Eventually, of course, Clothilda was seduced by Carl’s loving words and insistence, and their courtship began (). Carl met Clothilda’s mother and was praised for being content in the domestic environment. After a while, he went away ‘on business’, and his visits became increasingly rare. Clothilda waited in vain, until Carl finally ended their relationship on the pretence of obeying his father. Naturally, she was dejected, and the serial ended with her engagement to another man. By becoming a good (albeit unhappy) wife and eventually a tender mother, she fulfilled ‘her duty as a woman’.

Figure 7. Illustration 3 and 4, A Year in a Young Girl’s Life, published in Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder 1828/2, Uppsala University Library.

Table 2. Captions for illustrations in A Year in a Young Girl’s Life.

This story and many others were highly moralising, especially about women. The course of events followed a familiar route: a young woman, often described as beautiful, diligent, and unexperienced, is charmed, seduced, and eventually forsaken by a man acting under false pretences. In a closer look into their fates, however, it appears that being too inexperienced (as in the case of Clothilda) led to disaster, as did being too occupied with pleasure and looks. The stories usually ended with a moral twist, in which the women found a safe haven in marriage and motherhood, thus acceding to the recurrent and consistent cult of domesticity in European fashion and ladies’ magazines.Footnote86

Just like fashion, serial fictions were frequently copied.Footnote87 The settings were often interchangeable and described in neutral terms. Nothing in the republished story of Clothilda and Carl told the reader where the events took place, and place names were usually avoided. Magasin made some weak attempts to impose a national context by inserting Swedish place names, but personal names often gave stories’ foreign origins away. As with fashion, fictional material was often drawn from French and English journals. In the serial ‘Inexperience and Rashness. Fragments of the Fate of a Young Girl’, numerous reveal the story’s origins in an English journal. The main characters run away to Gretna Green to marry in secret and they watch the stage play, The Vicar of Wakefield.Footnote88 The popular book by Oliver Goldsmith (published in 1766) upon which the play was based was probably familiar to many readers of the Magasin, having been translated into Swedish in 1782. Although the title of the play was translated (Landpresten i Wakefield), several English words such as ‘lord’ and ‘fox’ were incorporated into Magasin’s version of the story.Footnote89 But where the story was clearly embedded in an English context, the accompanying illustrations were drawn by the French artist Jules Davis. An editorial footnote informed the reader that the story had been written to clarify Davis’s illustrations.

Whether or not the text and images were combined originally, they provide a clear example of the bricolage familiar from the fashion news that seems to have characterised periodicals in countries other than England and France. But whereas geographic attributions, especially metropolitan ones, were crucial for fashion, they seem to be irrelevant when it comes to serials. One explanation is that fiction did not rely upon specific national settings, but it also implies that the discourse of domesticity went beyond national borders. An important research task would be to trace the reprinting of serials further in relation to this discourse. Jennie Batchelor has shown that some of the fiction in the Lady’s Magazine was reprinted in periodicals in England, Scotland and America, but the scope could be widened to include translations into other languages as well as into English.Footnote90

The moral theme contrasting right and wrong was fully employed in two illustrated serials following the parallel careers of two people from youth to maturity. The explicit aim of these serials was moral upbringing, the illustrator (Jules Davis again) won a ‘moral education’ contest in France for his twelve lithographs accompanying each serial.Footnote91 The contest was described at some length. Illustrations were thought to be more efficient than any written words in achieving the aim of moral upbringing, especially among the working strata of society such as craftsmen and workmen. William Hogarth and other English artists served as examples of a successful implementation of a ‘love towards virtue and disgust towards vice’.Footnote92 The mention of Hogarth by name indicates that he was familiar to readers, or at least supposed to be. Of special interest – in this rather female context – is that the life course of both women and men were considered in these serials, as they were in Hogarth’s paintings and engravings.

Boije himself seems to have taken a special interest in these lithographs. He published the male life course separately the same year, in both coloured and black and white editions. According to the title page, this was meant to be a Christmas gift aimed at the moral upbringing of the children of craftsmen and ‘ordinary people’.Footnote93 While the working strata were ostensibly the target group, the lithographs of the fallen working class – the classes dangereuses – provided the necessary contrast to the successful middle class, and the works by Jules David serve as a textbook example.Footnote94

The Magasin started with ‘Virtue and vice’, picturing the careers of two men – Wilhelm (virtue) and Frans (vice) – and accompanying each step (related to age) with a dichotomy of characteristics.Footnote95 Put together, they again summarise the course of events (). The two boy’s stories have similar frameworks. Both had encountered poverty, symbolised by living in attics. They both started as apprentices, albeit in different crafts, and both married and settled down, although for opposite reasons and with different eventual outcomes. At the height of his life, Wilhelm lived in domestic bliss, loved by both his family and the workmen he employed; Frans’ life, in contrast, deteriorated quickly; he became a hardened criminal and was finally thrown into irons for the rest of his life.

Table 3. Captions for instalments in Virtue and vice (1838).

Each story recounted a decisive moment, when each made the choice that was to determine their fates. The ‘moment of choice’ was a common trope, not least in connection with moral ends, in which youths make important and irreversible choices.Footnote96 Clothilda, for example, made hers when she chose to answer the letter from Carl. Frans made an early choice, when at 12 years old he was caught by his master rambling in the streets and refusing to return to work. Wilhelm made his choice at the age of 25, when he declined an invitation from his friends to enjoy some amusement and instead stayed home to study ( and ). The young men were thereby, skilfully and over-explicitly, presented as each other’s counterpart. The moral message was unmistakable and meant to make a deep impression on ‘young men from the working classes’.

Figure 8. Illustration 1 (vice), Den dygdiges och den lastfulles vandel och öden (1838), Uppsala University Library.

Figure 9. Illustration 3 (virtue), Den dygdiges och den lastfulles vandel och öden (1838), Uppsala University Library.

The female equivalent, ‘Modest and depraved’, was structured in a similar way, with new episodes and illustrations in every issue, but with a more detailed story (captions in ).Footnote97 Just like Wilhelm and Frans, Sophie (modest) and Thilda (depraved) formed each other’s counterpart, and the drama was built all around the differences between them. They came from different backgrounds, Sophie an orphaned diligent girl, Thilda an indolent girl born with a silver spoon in her mouth; Sophie renounced all luxury and vanity, while Thilda embraced them; Sophie married and enjoyed her domestic life, while Thilda rejected marriage and domesticity to the point that she became an ‘unnatural mother’ (abandoning her own child to continue her depraved lifestyle).

Table 4. Captions for instalments in Modest and depraved (1840).

At the age of 20, they each faced the moment of choice that would affect their future. Sophie turned down a proposal from a fop, with a firm ‘No – never!’; Thilda snuck out of her home, disguised as boy, to attend a masquerade together with a ‘cousin’. The difference between them is best captured by one illustration of Sophie diligently doing some needlework in a neat room and Thilda looking in a mirror in her untidy chamber ( and ). When Sophie had reached domestic and maternal bliss, the publisher was persuaded by some female readers to discontinue the story, since the last parts about Thilda would be too unpleasant and offensive for educated and cultivated women. All the same, he did quickly summarise Thilda’s end in the spinning-house, surrendered to drunkenness and the laughing stock even of street urchins.Footnote98 Again, the message on how to act was clear, and stressed by the use of a right/wrong dichotomy. Although both stories were situated in a French context, they should be seen as parts of a gendered pan-European discourse on fundamental societal values, characterised by strong continuity. The reader who knew his Hogarth could easily see Thilda in A Harlot’s Progress and Frans in A Rake’s Progress.

Figure 10. Illustration 2 (modest), Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder 1840/3, Uppsala University Library.

Figure 11. Illustration 1 (depraved), Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder 1840/2, Uppsala University Library.

The inclusion of both female and male stories enables a comparison between values for women and men. There are some striking similarities in the positive characteristics portrayed for each sex: being hard working, industrious, diligent, educated, frugal, domestic, and respected were qualities worth striving for. However neutral or general they may seem, these characteristics were in fact highly gendered since they applied to different societal spaces. The differing characteristics emphasise the distinction between the private (feminine) and public (masculine) worlds. Women should be tender, lenient, modest, virtuous, and chaste, embodying the values connected with being a wife and a mother. Men on the other hand should be honest, skilful, useful, honourable, commendable, decent, and respected, all of which were related to the more public sphere of work and civic duties.

The gender difference was stressed further in the depictions of negative characteristics. A common negative trait was lättsinnig, which meant promiscuity for women but irrationality for men. Other negative values were vanity, anxiety to please, and being too easily persuaded for women and gambling, violence, and criminality for men. These signal vices threatened the fundamental roles of women and men. While the split into gendered spheres is an important result, manifested in many ways, it is also important to remember that setting up a family and living in ‘domestic bliss’ was a life goal for both women and men.Footnote99 The difference lies in the scope of each sex’s responsibilities, with women confined to the domestic sphere and men to public duties and work. These values fitted perfectly with the domestic femininity and rational masculinity discussed earlier, thus presenting readers with a gendered self-image in line with the formation of the middle class.

Still, there remained room for irony and satire. Although most serials and shorter stories focused on the long and winding road to marriage, as in a traditional fairy tale, being married was not always a ‘happily-ever-after’ bed of roses. One illustrative example is the comedy ‘Far too good!’ in which a young newlywed wife receives some marital advice from a ‘lively’ widow.Footnote100 According to the widow, the wife was too compliant and dressed too simply. To get her husband’s attention, she was advised to argue and even provoke him, showing some independence: ‘have your own opinion, and be lively’. She should also be more concerned with her appearance, carefully following the latest fashion and, if necessary, even be a little anxious to please.

This satire provides a rather harsh critique of a too circumscribed role for (married) women, not least in regard to their subordination to their husbands. As pointed out by Jenny DiPlacidi, magazine fiction often addressed the ‘tenuous position’ of women, thus opposing the domestic paradigm circulated by the same magazines.Footnote101 Magasin’s inclusion of several female role models and its emphasis on the importance of female education and refinement points in the same direction and suggests a striving for an equal society.Footnote102 Approximately one third of the biographies in Magasin portrayed women, which is a considerable amount compared with many British magazines. The inclusion of female regents, such as Queen Kristina (of Sweden) and Empress Catherine (of Russia), also displays role models with political power.Footnote103

Nowhere is the critique more clearly articulated than in the closing scene of the story of Clothilda. With her bitter fate in mind, a writer with the pen name ‘Sophie’ seised the opportunity to argue in defence of women.Footnote104 Why, she asked, is the girl more to blame than the man who seduced her (and probably others as well)? Wherein lies the justice in the judgement, when it was always he who made the first move? It was a glaring injustice, a moral murder even, to make the woman suffer throughout her life just because she acted out of inexperience and tenderness. In the unfair world, the incautiousness and imprudence of the girl was never forgiven, although she acted out of pure love and affection. Should the stigmatisation not be twice as severe for the man who acted so callously? But no. Men wrote the law and were, contrary to every legal principle, judges in their own cases. This was sharp criticism of the existing gender order, with its different rules and expectations for women and men. In a longer perspective, this criticism can be seen as a forerunner of a more open fight for increased gender equality. Articles with this agenda were numerous in the Swedish ladies’ magazine Penelope in the 1850s. According to the magazine, Swedish women’s situation was most precarious, while England and France, now accompanied by North America, again set good examples.Footnote105

Similar critiques were delivered in France, Italy, and England. Ahead of its time, Journal des Dames called for equality between the sexes, La donna galante ed erudita published some ‘fierce critique of women’s predicament in a man’s world’, and Lady’s Magazine published radical reader contributions on women’s right to education.Footnote106 Still, the Swedish magazine seems to have been more inclined than its continental counterparts to include explicit critique on the existing gender order. By analysing Magasin I have established the prevalence of rather radical thoughts in the European periphery. Further research on how critiques of the gender order differed between countries would provide valuable information on the influence of national culture on the well-established cult of domesticity. It would also put English and French magazines in a much-needed European context.

To conclude, texts on love and marriage were highly moralising, especially towards women, in fashion and ladies magazines in general. One primary method of promoting this morality in serials was to focus on what a younger woman should avoid at any cost while highlighting the risks of giving way to ‘courtship’. Another method was the consistent use of opposites to contrast right with wrong, diligent with indolence, and industry with anxiety to please, often with a satirical twist. The lesson taught was that everyone needed to consider the consequences of their actions and realise that it was in their power to choose the correct way of living – or not. The message conveyed was, on the whole, the same, whether it was read in Uppsala, Hereford or Arles. While the ideology of domestic bliss was promoted, fundamental norms were also called into question. This contradiction allowed for the creation of a pan-European female self-image that did not fully embrace domesticity and suggested that the moral literacy communicated in the magazine could be something to oppose rather than accept.

Conclusion: an (inter)national middle class

Readers of the June issue had learnt about the technically advanced enterprise of building a tunnel under the River Thames, enjoyed a poem set to music, been updated by detailed fashion reports, and followed the cautionary story of Clothilda to its bittersweet end. Most likely, they were affected by the harsh critique from ‘Sophie’, although their reactions probably differed. Altogether, a great variety of values and identities were communicated by Magasin, summarised in an idealised definition of a feminine identity centred on fashion consciousness and domesticity. Firm as they might seem, the values communicated were in fact quite ambiguous and raised arguments for a more radical approach.

Thanks to magazines frequent use of bricolage, the pan-European middle-class consumer culture was also well established in the peripheral northern countries; the material and moral literacy conveyed in Magasin was clearly international. However, it should be stressed that until well into the nineteenth century the Swedish economy remained agrarian, and general freedom of trade was not imposed until 1864. Urbanisation, so important to the creation of a middle class, was markedly lower in Sweden than in many other countries, especially England. Consequently, the numbers of people in Sweden who could identify with middle-class culture were not overwhelming, but for those who could, there must have been an eagerness to embrace the new culture.

Setting international culture aside, Magasin also contained elements of a national identity. It often expressed a passion for a gothic past (old Norse romanticism), presented Swedish royalties and ‘celebrities’ in parallel with international ones, and paid great attention to royal ceremonies. Thus, a reader could frame a national education within an international one. The interplay between national and international cultures was characteristic of many periodicals other than the English and the French. As Michael North found for Germany, national identities were formed in dialogue with the ‘entire cultivated world’.Footnote107

Returning to the female self-image, Magasin’s emphasis on fashionable consumption expanded female readers’ worldview, while its stress on domesticity restricted it. The combination of European and Swedish cultures, however, expressed the need for women to be strong and independent. Traditional and moralising as they might be, fashion magazines broadened their readers’ horizons from fleeting fashion changes to the beginning of a redefined social identity.

Acknowledgement

An earlier version of this work was presented at the European Social Science History Conference in Valencia in 2016 and at the Gender and Work seminar at Uppsala University in 2018. I also thank Mikael Alm, Jon Stobart, and the reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gudrun Andersson

Gudrun Andersson is Associate Professor at the Department of History at Uppsala University. Her research interest include gender history, cultural history and material culture, in seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth century Sweden. She has published extensively on gender, elite status and consumption, and is currently working on diaries by the middling sort, and on fashion magazines and the formation of the bourgeoisie.

Notes

1 The magazine was issued from 1818 to 1844. The original title Konst- och nyhetsmagasin för medborgare af alla klasser (Magazine of Art and News for Citizens of All Classes) was changed in 1823, the new title reflecting the content in a more accurate way. It was never a magazine for all social classes. The whole edition is digitised and available (free of charge) at Alvin, the Uppsala University’s platform for digital collections and digitised cultural heritage (https://www.alvin-portal.org/alvin/; for Boije specifically, https://kontext.dropmark.com/436197?page=1).

2 For an extensive list of British magazines, see Batchelor and Powell, “Appendix,” 488–91.

3 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance; Messbarger, The Century of Women, 15, 29; Batchelor, Dress, Distress and Desire, 7; Andersson, “Modets ekonomi,” 143–56.

4 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, xiii–xiv (quote), 26.

5 Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure, xi–xvii.

6 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 40–1 (quote); Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure, xvi–xvii.

7 Smith, Consumption and the Making of Respectability. See also Mackie, Market á la Mode, 144–6.

8 Aaslestad, “Sitten und Mode,” 302. See also Gelbart, Feminine and Opposition, 303.

9 Batchelor Dress, Distress and Desire, 115. On the formative influence of media, see also Mackie Market á la Mode, 151.

10 For recently published overviews: Flood and Grant, Style and Satire; Best, The History of Fashion Journalism; Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s; Women, periodicals and print culture in Britain, 1830s–1900s.

11 Beetham, A Magazine of Her Own?; Batchelor, Dress, Distress and Desire; Batchelor, “[T]o Cherish Female ingenuity”.

12 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance; Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure; North, Material Delight and the Joy of Living; North, “Fashion and Luxury in Eighteenth Century Germany”. See also Das ‘Journal des Luxus und der Moden’; Aaslestad, “Sitten und Mode”.

13 Messbarger, The Century of Women. See also Sama, “Liberty, Equality, Frivolity!,” 389–414; Clemente, “Luxury and Taste in Eighteenth-Century Naples,” 59–76.

14 Taylor, “Important Trifles,” 1.

15 Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror,” 181.

16 McNeil, “Introduction,” 17. (McNeil refers to studies in the English-speaking world).

17 Maxwell, Patriots Against Fashion, 4–5.

18 Alm, Sartorial Practices and Social Order, 13.

19 Leis, “Displaying Art and Fashion,” 252, 257; Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure, xvii.

20 Fredrik Boije was engaged in a variety of spheres – as editor, engraver, art historian, chamberlain and officer in the cavalry.

21 Andersson, “Modets ekonomi,” 143–4. There were 63 female and 313 male subscribers. A similar list, but without the royal element, is available for Läsning för fruntimmer (Ladies’ Readings). Berg, “Medelklassens fruntimmer,” 38. This mix of subscribers, with royalties and booksellers, women and men, also resembles that of Lady’s Magazine. Adburgham, Women in Print, 206; Batchelor and Powell, “Introduction,” 17.

22 In Jönköping, another provincial town, a bookbinder signed up for five subscriptions.

23 North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 104; Batchelor and Powell, “Introduction,” 13. The numbers for the German journal refer to earlier issues (1788), and had increased to 1,765 in 1799; the numbers for the British one refer to its height of popularity.

24 Best, The History of Fashion Journalism, 27. For number of readers, see Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 11; Batchelor and Powell, “Introduction,” 12. Purdy suggests ten to twenty readers for each copy, Batchelor and Powell suggest twenty to forty. Journal des dames et des modes had as many as 11,000 readers, Cage, “The Sartorial Self,” 195.

25 The mixed content is a magazine hallmark. Beetham, A Magazine of Her Own?, 12–13, 19.

26 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 7–8; Beetham, A Magazine of Her Own? 21–2; Batchelor & Powell, “Introduction,” 12; Messbarger, The Century of Women, 113; Best, The History of Fashion Journalism, 28; Michael North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 101–3.

27 In Lady’s Magazine, the biographies on contemporary women were scarce. Hudson, “This Lady is Descended from a Good Family,” 279. On the portraits, see Engel, “Magazine Miniatures”.

28 Messbarger, The Century of Women, 107–8; North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 101; DiPlacidi, “Full of Pretty Stories,” 268.

29 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, chapter 2.

30 Huck, “Visual Representations,” 163–5 (quote 163).

31 The high quality of the plates was due to the skilled editor’s fine engraving, which made them stand out among plates in other journals, both Swedish and international.

32 The supplements in Lady’s Magazine were expected to be removed before one year’s issues were bound in volume form. Regarding La donna … , see Messbarger, The Century of Women, 112–3. One reason for the scarcity of advertisements in Swedish newspapers and journals was restrictive guild regulations. Murhem and Ulväng, “To Buy a Plate,” 203. Fashion magazines usually relied on subscriptions rather than ads for income. Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror,” 171.

33 On the general dominance of French fashion, see Persson, Empirens döttrar, 27; Best, The History of Fashion Journalism, 15; Nyberg, “French model and rise of Swedish fashion,” 42.

34 Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder [hereafter MfKNM] 1826/5, 40, 1827/3, 25. On a few occasions, it also emphasised that a certain fashion was not a novelty in Stockholm. See e.g. MfKNM 1824/11, 1830/11, 1837/5, 1840/5.

35 MfKNM 1826/5, 40, 1838/12, 188, 1842/12, 190.

36 Messbarger, The Century of Women, 108, 111–2; Rasmussen, Skräddaren, sömmerskan och modet, 102, 105.

37 Petit Courrier des Dames 1826, No. 357; MfKNM 1827/3, 24. Fashion illustrations from the Petit Courrier des Dames are available at www.rijksmuseum.nl. Many thanks to Elin Ivarsson for finding me the French plate.

38 During the second half of the 19th century, England became ‘leaders in high fashion’. Shannon, The Cut of His Coat, 2.

39 Persson, Empirens döttrar, 41. Since the Repository was issued between 1809 and 1829, it can hardly have been used as a model for the illustrations in the Magasin in the 1830s. In the late 1800s, German illustrations came to dominate the Swedish magazines. Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror,” 182.

40 North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 102–5. One consequence of the aversion towards French fashion was a critical attitude towards Vienna (at that time in French hands). From a central European perspective, Vienna became the most fashionable during the nineteenth century. Maxwell, Patriots Against Fashion, 212–4.

41 Clemente, “Luxury and Taste in Eighteenth-Century Naples,” 64–9. See also Ijäs, “English Luxuries in Nineteenth-Century Viborg,” 271.

42 MfKNM 1823/1824 / 14, 112.

43 MfKNM 1827/12, 95.

44 North, ’Fashion and Luxury’, 102.

45 Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 1–3, 26; Clemente, “Luxury and Taste in Eighteenth-Century Naples,” 65.

46 Grill, Resedagbok från England, 1788, 46. German and Swiss travellers wrote similar reflections. Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 27; Berry, “Polite Consumption,” 380–2.

47 Breward, “Femininity and Consumption,” 71–89, quote 87; Copeland, Women Writing About Money, 117.

48 MfKNM 1825/9, 72. Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure, 156.

49 McNeil, “Introduction,” 7.

50 With few exceptions, every annual volume also included fashion costumes for girls and boys. The children usually appeared with women, but fashion plates including a woman, a man, and a child also occurred. Andersson, “Modets ekonomi,” 149.

51 Karin Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure, 175. Sartorial distinctions came to be based on gender, instead of class. Shannon, The Cut of His Coat, 25.

52 Dyer, “Stitching and Shopping,” 99, 110. Regarding haptic skills, see Smith, “Sensing Design and Workmanship,” 3–6.

53 Messbarger, The Century of Women, 112. The sewing skills of women should also be taken into consideration. Smith, “Fast Fashion,” 440, 444.

54 The importance of decorative garments is emphasised by von Wachenfeldt, “Rational follies,” 28–31.

55 Konst- och nyhetsmagasin för medborgare af alla klasser 1818, 8.

56 Alm, “Making a Difference,” 49–52.

57 Konst- och nyhetsmagasin för medborgare af alla klasser 1818, 12; 1819, 28.

58 MfKNM 1823–24/8, 64.

59 The Swedish bekväm has a longer tradition than the English comfort. As used in the magazine, it refers to the meanings of comfort. Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 58; Stobart & Prytz, “Comfort in English and Swedish country houses,” 239; Stobart, “Introduction,” 1–16.

60 Alm, “Making a Difference,” 52 discusses the imbalance between French fashion and the Swedish climate.

61 North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 106.

62 See also Brekke-Aloise, “A Very Pretty Business,” 202; Flood & Grant, Style and Satire, 17, 28; Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror,” 184.

63 MfKNM 1825/4, 32. See also MfKNM 1826/7, 55, where a more detailed schedule for activities and dress was presented.

64 MfKNM 1828/8, 63–4.

65 Wurst, “The Self-Fashioning of the Bourgeoisie,” 174; Messbarger, The Century of Women, 112, 119; Smith, “Fast Fashion,” 446–7.

66 See also Adburgham, Women in Print, 206; Smith, “Fast Fashion,” 448, 452.

67 Breward, “Femininity and Consumption,” 83.

68 Messbarger, The Century of Women, 124–6; Runefelt, Att hasta mot undergången, 180–6; Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror,” 186.

69 MfKNM 1825/10, 74.

70 MfKNM 1829/9, 80.

71 North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 108.

72 MfKNM 1834/1, 4–5. The satire is attributed to Boufflers. In another issue, “Madame LaMode” informed her (female) followers that one year for her was equivalent to half a century in the real world. MfKNM 1842/1, 1.

73 MfKNM 1834/1, 4.

74 MfKNM 1836/1, 8. Vickery, “Mutton Dressed as Lamb?,” 859–60.

75 Articles and comments related to (female) age are common, not least in regard to marriage.

76 Vickery, “Mutton Dressed as Lamb?”. See also Helena, Empirens döttrar, 32; Dyer, “Barbara Johnson’s Album,” 274–6.

77 MfKNM 1827/2, 11–13. Further ’political’ examples concerned ‘the defence of political women’ and ‘the women’s diet’, MfKNM 1831/11, 83–4, 1835/7, 55–6.

78 Brekke-Aloise, “A Very Pretty Business,” 194; Flood andGrant, Style and Satire. 21; Runefelt, “The Corset and the Mirror,” 185–6.

79 Batchelor, Dress, Distress and Desire, 11–12.

80 Beetham, A Magazine of her Own?, 22; Taylor, “Important Trifles,” 12.

81 Batchelor, “[T]o cherish Female ingenuity,” 377–92; DiPlacidi, “Full of Pretty Stories,” 261–77.

82 Flood andGrant, Style and Satire, 27; DiPlacidi, “Full of Pretty Stories,” 265. On the powerful effect of combining images and text, see Sama, “Liberty, Equality, Frivolity!,” 392; Wurst, Fabricating Pleasure, xvi; Dyer, “Barbara Johnson’s Album,” 269. On the ability to ‘read’ texts and images, see Huck, “Visual Representations,” 174–6.

83 DiPlacidi, “Full of Pretty Stories,” 266.

84 Pearson, “Books, My Greatest Joy,” 5; Purdy, The Tyranny of Elegance, 240; Batchelor, Dress, Distress and Desire, 108.

85 MfKNM 1928/1–6.

86 Armstrong, “The Rise of Domestic Woman”; Beetham, A Magazine of Her Own? 23, 42; Messbarger, The Century of Women, 17–18; Batchelor, Dress, Distress and Desire, 12; Flood andGrant, Style and Satire, 25.

87 Copeland, Women Writing About Money, 137.

88 Historically, Gretna Green was a village famous for allowing clandestine marriages. A marriage would be legal even without consent from a guardian (parent).

89 MfKNM 1834/3, 20–21, 1834/4, 31.

90 Batchelor, “[T]o cherish Female ingenuity,” 378.

91 Jules Davis (1808–1892) was a prominent French painter and lithographer, famous for, among other things, his thousands of fashion plates drawn for French magazines.

92 MfKNM 1838/2, 4. The paintings referred to are Hogarth’s Modern Moral Series (including ‘Industry and Idleness’) painted between 1733 and 1751.

93 Boye, Den dygdiges och den lastfulles vandel och öden.

94 McWilliam, Social Art and the French Left, 325–9; Tjeder, The Power of Character, 66–9. Both McWilliam and Tjeder exemplify their arguments with, among others, Jules David’s ‘Virtue and vice’.

95 MfKNM 1838/1–12. The French title is Vice, et Vertu, Album moral représentant en action les suites inévitables de la bonne et de la mauvaise conduit.

96 Tjeder, The Power of Character, 50–5. See also Copeland, Women Writing About Money, 132.

97 MfKNM 1840/1–10. The French title is Sagesse et Inconduite. Album moral, représentant en action les suites de la bonne et mauvaise conduite chez les femmes.

98 MfKNM 1840/10, 150.

99 Tjeder, The Power of Character, 90.

100 MfKNM 1844/12, 180–4.

101 DiPlacidi, “Full of Pretty Stories,” 269.

102 Gelbart, Feminine and Opposition Journalism, 293.

103 Ahnstedt, “Mode eller modellering?”; Hudson, “This Lady is Descended from a Good Family,” 278–9.

104 There is no information on who ‘Sophie’ was, but she wrote regularly in Magasin. The criticism was hinted at in earlier episodes as well, e.g. 1828/4, 29, 1828/5, 34–5.

105 Penelope. Nyaste journal för damer, 1855/1, 3–4, 1855/8, 3–4, 1855/9, 3–4, 1855/10, 3–4. This argued that women would be best suited to rule society and that formal acknowledgement of the power already exercised by women was needed.

106 Gelbart, Feminine and Opposition Journalism, 294–5; Messbarger, The Century of Women, 127; Batchelor, “[T]o cherish Female ingenuity,” 384.

107 North, “Fashion and Luxury,” 111.

Bibliography

- Aaslestad, Katherine B. “Sitten und Mode. Fashion, Gender, and Public Identities in Hamburg at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century.” In Gender in Transition: Discourse and Practice in German-Speaking Europe, 1750–1830, edited by U. Gleixner, and M. Gray, 282–318. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006.

- Adburgham, Alison. Women in Print. Writing Women and Women’s Magazines from the Restoration to the Accession of Victoria. London: Faber and Faber, 1972.

- Ahnstedt, Axel. “Mode eller modellering? Svenska elitideal i 1800-talets borgliga samhälle.” unpublished bachelor thesis, Dep. of History, Uppsala University.

- Alm, Mikael. “Making a Difference: Sartorial Practices and Social Order in Eighteenth-Century Sweden.” Costume 50, no. 1 (2016): 42–62.

- Alm, Mikael. Sartorial Practices and Social Order in Late Eighteenth-Century Sweden: Fashioning Difference. London, New York: Routledge, forthcoming.

- Andersson, Gudrun. “Modets ekonomi. Borgerlig konsumtion i Magasin för konst, nyheter och moder.” In Allt på ett bräde. Stat, ekonomi och bondeoffer. En vänbok till Jan Lindegren, edited by Peter Ericson, Fredrik Thisner, Patrik Winton, and Andreas Åkerlund, 143–156. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, 2013.

- Armstrong, Nancy. “The Rise of Domestic Woman.” In The Ideology of Conduct. Essays on Literature and the History of Sexuality, edited by Nancy Armstrong, and Leonard Tennenhouse, 96–141. New York: Methuen, 1987.

- Batchelor, Jennie. Dress, Distress and Desire. Clothing and the Female Body in Eighteenth-Century Literature. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave, Macmillan, 2005.

- Batchelor, Jennie. ““[T]o Cherish Female Ingenuity, and to Conduce to Female Improvement”: The Birth of the Woman’s Magazine.” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 377–392. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Batchelor, Jennie, and Manushaug N. Powell. “Appendix.” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 488–491. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Batchelor, Jennie, and Manushag N. Powell. “Introduction: Women and the Birth of Periodical Culture.” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 1–19. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Beetham, Margaret. A Magazine of Her Own? Domesticity and Desire in the Woman’s Magazine, 1800–1914. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Berg, Anne. “Medelklassens fruntimmer. Fruntimmersbildningen och skapandet av medelklasskvinnor, ca 1780–1820.” In Det mångsidiga verktyget. Elva utbildningshistoriska uppsatser, edited by Anne Berg, and Hanna Enefalk, 31–50. Uppsala: Opuscula Historica Upsaliensia, 2009.

- Berry, Helen. “Polite Consumption; Shopping in Eighteenth-Century England.” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 12 (2002): 375–394.

- Best, Kate Nelson. The History of Fashion Journalism. London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- Boye, Fredrik. Den dygdiges och den lastfulles vandel och öden. Moraliskt föreställde i 12 bilder. Julklapp till upmuntran och varning för handtverkare och menige-mans barn. Stockholm, 1838.

- Brekke-Aloise, Linzy. ““A Very Pretty Business”: Fashion and Consumer Culture in Antebellum American Prints.” Winterthur Portfolio 48, no. 2–3 (2014): 191–212.

- Breward, Christopher. “Femininity and Consumption: The Problem of the Late Nineteenth-Century Fashion Journal.” Journal of Design History 7, no. 2 (1994): 71–89.

- Cage, E. Claire. “The Sartorial Self: Neoclassical Fashion and Gender Identity in France, 1797–1804.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 42, no. 2 (2009): 193–215.

- Clemente, Alida. “Luxury and Taste in Eighteenth-Century Naples: Representations, Ideas and Social Practices at the Intersection Between the Global and the Local.” In A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe. Display, Acquisition and Boundaries, edited by Johanna Ilmakunnas, and Jon Stobart, 59–76. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- Copeland, Edward. Women Writing About Money. Women’s Fiction in England, 1790–1820. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1995.

- Das ‘Journal des Luxus und der Moden’. Kultur um 1800, ed. Angela Borchert & Ralf Dressel (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag Winter 2004).

- DiPlacidi, Jenny. ““Full of Pretty Stories”: Fiction in the Lady’s Magazine (1770–1832).” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 263–277. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Dyer, Serena. “Barbara Johnson’s Album: Material Literacy and Consumer Practice, 1746–1823.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies 42, no. 3 (2019): 263–282.

- Dyer, Serena. “Stitching and Shopping: The Material Literacy of the Consumer.” In Material Literacy in Eighteenth-Century Britain: A Nation of Makers, edited by Serena Dyer, and Chloe Wigston Smith, 99–116. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

- Engel, Laura. “Magazine Miniatures: Portraits of Actresses, Princesses, and Queens in Late Eighteenth-Century Periodicals.” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 458–473. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Flood, Catherine, and Sarah Grant. Style and Satire. Fashion in Print 1777–1927. London: V&A publishing, 2014.

- Gelbart, Nina Rattner. Feminine and Opposition Journalism in Old Regime France. Le Journal des Dames. Berkeley: University of California press, 1987.

- Grill, Anna Johanna. Resedagbok från England, 1788. Stockholm: Atlantis, 1997 [1788].

- Huck, Christian. “Visual Representations.” In A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of the Enlightenment, edited by Peter McNeil, 161–183. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- Hudson, Hannah Doherty. ““This Lady is Descended from a Good Family”: Women and Biography in British Magazines, 1770–1798.” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 278–293. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Ijäs, Ulla. “English Luxuries in Nineteenth-Century Viborg.” In A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe. Display, Acquisition and Boundaries, edited by Johanna Ilmakunnas, and Jon Stobart, 265–282. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- Leis, Arlene. “Displaying Art and Fashion: Ladies Pocket-Book Imagery in the Paper Collections of Sarah Sophia Banks.” Konsthistorisk tidskrift/Journalof Art History 82, no. 3 (2013): 252–271.

- Mackie, Erin. Market á la Mode. Fashion, Commodity, and Gender in The Tatler and The Spectator. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Maxwell, Alexander. Patriots Against Fashion. Clothing and Nationalism in Europe’s Age of Revolutions. Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, 2014.

- McNeil, Peter. “Introduction.” In A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of the Enlightenment, edited by Peter McNeil, 1–21. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- McWilliam, Neil. Social Art and the French Left, 1830–1850. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Messbarger, Rebecca. The Century of Women. Representations of Women in Eighteenth-Century Italian Public Discourse. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

- Murhem, Sofia, and Göran Ulväng. “To Buy a Plate: Retail and Shopping for Porcelain and Faience in Stockholm during the Eighteenth Century.” In A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe. Display, Acquisition and Boundaries, edited by Johanna Ilmakunnas, and Jon Stobart, 197–215. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- North, Michael. Material Delight and the Joy of Living. Cultural Consumption in the Age of Enlightenment in Germany. Ashgate: Aldershot, 2008.

- North, Michael. “Fashion and Luxury in Eighteenth Century Germany.” In A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe. Display, Acquisition and Boundaries, edited by Johanna Ilmakunnas, and Jon Stobart, 99–115. London: Bloomsbury, 2017.

- Nyberg, Klas. “French Model and Rise of Swedish Fashion.” In Luxury, Fashion and the Early Modern Idea of Credit, edited by Klas Nyberg, 34–47. London, New York: Routledge, 2021.

- Pearson, Jacqueline. “Books, “My Greatest Joy”: Constructing the Female Reader.” The Lady’s Magazine’, Women’s Writing 3, no. 1 (1996): 3–15.

- Persson, Helen. Empirens döttrar. Kultur och mode under tidigt 1800-tal. Signum: Lund, 2009.

- Purdy, Daniel L. The Tyranny of Elegance. Consumer Cosmopolitanism in the Era of Goethe. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1998.

- Rasmussen, Pernilla. Skräddaren, sömmerskan och modet. Arbetsmetoder och arbetsdelning i tillverkningen av kvinnlig dräkt 1770–1830. Stockholm: Nordiska museets förlag, 2010.

- Runefelt, Leif. Att hasta mot undergången. Anspråk, flyktighet, föreställning i debatten om konsumtion i Sverige 1730–1830. Nordic Academic Press: Lund, 2015.

- Runefelt, Leif. “The Corset and the Mirror. Fashion Domesticity in Swedish Advertisements and Fashion Magazines, 1870–1914.” History of Retailing and Consumption 5, no. 2 (2019): 169–193.

- Sama, Catherine M. “Liberty, Equality, Frivolity! An Italian Critique of Fashion Periodicals.” Eighteenth Century Studies 37, no. 3 (2004): 389–414.

- Shannon, Brent. The Cut of His Coat. Men, Dress, and Consumer Culture in Britain, 1860–1914. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2006.

- Smith, Woodruff. Consumption and the Making of Respectability, 1600–1800. New York and London: Routledge, 2002.

- Smith, Katie. “Sensing Design and Workmanship: The Haptic Skills of Shoppers in Eighteenth-Century London.” Journal of Design History 25, no. 1 (2012): 1–10.

- Smith, Chloe Wigston. “Fast Fashion: Style, Text, and Image in Late Eighteenth-Century Women’s Periodicals.” In Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, edited by Jennie Batchelor, and Manushag N. Powell, 440–457. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

- Stobart, Jon. “Introduction: Comfort, the Home and Home Comforts.” In The Comforts of Home in Western Europe, 1700–1900, edited by Jon Stobart, 1–16. London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2020.

- Stobart, Jon, and Cristina Prytz. “Comfort in English and Swedish Country Houses, c. 1760–1820.” in Social History 43, no. 2 (2018): 234–258.

- Taylor, Jane. ““Important Trifles”: Jane Austen, the Fashion Magazine, and Inter-Textual Consumer Experience.” Abstract, History of Retailing and Consumption 2, no. 2 (2016): 113–128.

- Tjeder, David. The Power of Character: Middle-Class Masculinities, 1800–1900. Stockholm, 2003.

- Vickery, Amanda. “Mutton Dressed as Lamb? Fashioning Age in Georgian England.” Journal of British Studies 52, no. 4 (2013): 858–886.

- von Wachenfeldt, Paula. “Rational follies. Fashion, Luxury and Credit in Eighteenth-Century Paris.” In Luxury, Fashion and the Early Modern Idea of Credit, edited by Klas Nyberg, 19–33. London, New York: Routledge, 2021.

- Women’s Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1690–1820s. The Long Eighteenth Century, ed. Jennie Batchelor & Manushag N. Powell (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2018).

- Women, Periodicals and Print Culture in Britain, 1830s–1900s. The Victorian Period, ed. Alexis Easley, Clare Gill, & Beth Rodgers (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

- Wurst, Karin A. “The Self-Fashioning of the Bourgeoisie in Late-Eighteenth-Century German Culture: Bertuch’s Journal des Luxus und der Moden.” The Germanic Review: Literature, Culture, Theory 72, no. 3 (1997): 170–182.

- Wurst, Karin. Fabricating Pleasure. Fashion, Entertainment and Cultural Consumption in Germany, 1780–1830. Detroit: Wayne University Press, 2005.