ABSTRACT

This article explores the landowning farm households’ consumption of foreign and manufactured goods in the hinterland of northern Sweden in 1770 to 1820. A set of probate inventories shows that the farmers in this particular area – a remote but central transit area for goods between the Norwegian coast and southern Sweden – were part of the general historiography of consumption. However, the findings of tea and coffee utensils, porcelain, printed cotton, silk fabrics and worsted fabrics show that their consumer behaviour – defined as ‘semi-industrious’ – was shaped by the area’s characteristics. The farmers increased their market participation and consumption of goods without breaking their existing consumption culture. They simply acquired more of the same – worsted fabrics for clothing and accessories in printed cotton and silk fabrics. The pattern of consumption is explained by the area’s firm population structure, strong class barriers and practical aspects such as poor housing. The manufactured fabrics responded to many purposes in the farmers’ day-to-day lives. The worsted fabrics were durable, warm and exclusive and the accessories fashionable. Compared with tea and coffee utensils, porcelain, clothing was a versatile belonging that did not need a home to be shown.

Introduction

The extensive consumption research tells us that foreign goods, such as coffee and cotton, were central to the gradual transformation of Europe into a modern consumer society. The research that focuses on the demand for goods can be divided into two broad areas of interest: how people increased their consumption of goods, and why they demanded particular goods. The matter of ‘how’ is mainly related to questions about income and labour-force participation. The century before the industrial era was characterised by growing consumption in many classes of societies.Footnote1 Given the idea that real incomes remained stable or even declined, Jan de Vries argues that a growing demand for market goods motivated households to reallocate their resources – especially women’s and children’s use of time – encouraging them to work harder and become more market-oriented.Footnote2 This ‘industrious revolution’ is assumed to have been a forerunner of the industrial breakthrough and to have set the stage for modern economic growth. Several studies have pointed out that the industrious revolution varied in strength and course depending on the context.Footnote3

In the Nordic countries, the process was less straightforward than in early industrialised countries.Footnote4 Separate studies by Ragnhild Hutchison and Alan Hutchison confirm that production, consumption and market participation increased in Norway over the course of the 18th century, but it is not possible to say that the demand for market goods was the main driving force of growth.Footnote5 Whatever the cause, the research agrees that the consumption of textiles, caffeine drinks and household goods increased substantially in the century before the industrial breakthrough.

Today, we know more about the consumption of goods in cities and households in close proximity to cities and ports, areas known to promote consumption. The purpose of this study is to contribute to our understanding of the consumption of foreign and manufactured goods in an area far from coasts and urban settlements – the Swedish province of Härjedalen on the border with Norway – between 1760 and 1820.

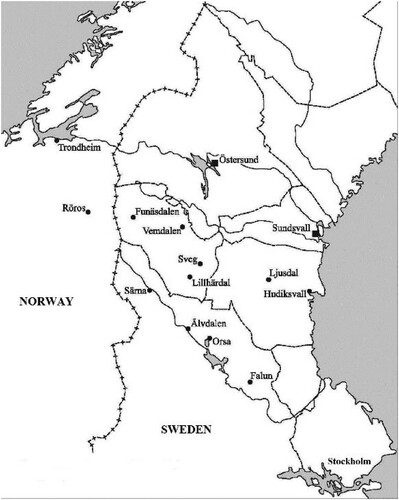

The survey area has thus been selected based on its geographical remoteness and its inclusion in an ongoing commercialisation process. Most people were landowning farmers, and they are also the focus of the survey. On the one hand, Härjedalen was a sparsely populated area, without cities and ports in the forested hinterland. On the other hand, the farm households’ involvement in trade made Härjedalen an important transit area for goods between the Norwegian seaport of Trondheim and the mining town of Röros, the linen industry in Hälsingland and the centre of iron production in Bergslagen, which also meant connections with Stockholm and other cities in the surrounding area of Mälardalen.Footnote6 (see Figure 1) During the studied period, the Swedish population grew from nearly 2 to 2.6 million. Footnote7 Almost 90 percent lived in rural areas and mainly in the southern parts and on the coasts. At the turn of the 1800s the capital, Stockholm, had just over 75,000 inhabitants.Footnote8

Figure 1. Map of the region Södra Norrland and Dalarna which shows villages and towns mentioned in the farm households’ incoming and outgoing debts in probate inventories. The map is drawn by Marianne von Essen, Jamtli.

The circumstances in Härjedalen offer us a different and not yet studied perspective on consumption. The fact that the people were both farmers – a group known for being rather conservative in their consumption – and traders, with access to a wide range of goods, raises questions about which goods households preferred and why. Moreover, the study area offers an insight into the presence of foreign and manufactured goods in a peripheral area.

The study is based on a set of probate inventories, from which six objects associated with food, home, or clothing – tea and coffee utensils, porcelain, printed cotton, silk fabrics and worsted fabrics – have been selected. The questions are as follows: to what extent and why did the landowning farm households either acquire or not acquire these goods? Did consumption increase or otherwise change over time? Did the pattern of consumption in Härjedalen differ from the general historiography of consumption?

The years 1760 to 1820 cover a period when Swedish policy aimed to develop domestic production by protecting it from foreign competition and suppress so-called ‘luxury consumption’.Footnote9 To achieve this, the government introduced import barriers, sumptuary laws, taxes on goods and state-supported manufacturing. The establishment of the Swedish East Indian Company was one way of preventing the importing of Chinese goods from Western Europe. The same motive lay behind the Swedish aspiration to acquire colonies in the West Indies and South America. The period is characterised both by an increased supply of foreign and manufactured goods and an ambition to limit and control their consumption.

Of great importance for people’s opportunities to consume and participate in trading activities was that crafting and trade until 1846 were considered urban livelihoods. This meant that the rural population — almost 90 percent of the total — needed to make their purchases in towns or at certain periodic markets, and that cities were hubs for the distribution of goods.Footnote10

Research overview: economic, social and practical considerations

In the extensive research on consumption there are three perspectives of particular interest for this study – economic, social and practical. Not only are they difficult to distinguish from each other but they are also closely related to geographical factors such as climate, livelihood and distance.

Basically, the demand for goods was linked to people’s purchasing power and access to goods. A general assumption is that the demand for goods was elastic and related to what was left after basic needs were provided for.Footnote11 Yet what was considered a basic necessity is a highly relative and contextual issue. In preindustrial times, and especially in rural households with a high degree of economic self-sufficiency, extra income was considered a bonus that could be converted into anything other than essentials. A longer period with an extra inflow of cash could have an immediate and major impact on people’s wardrobes, for example.Footnote12

In areas with a diverse population and high mobility, such as in cities and the surrounding countryside, people were more likely to adopt new things than in areas with a small and homogeneous population.Footnote13 In the households of the privileged classes, servants could get paid with fashionable clothes, or become familiar with tea drinking by reusing their gentrified employers’ tealeaves. If craftspeople worked for households of both the upper or lower classes, new fashion styles could be transferred. In rural areas, the spread of new goods moved quickly as soon as a commodity was accepted within a socially comparable layer.Footnote14

Today, the idea that consumption was primarily driven by competitive behaviour and that the lower classes uncritically imitated the upper classes has been replaced by the view of consumption as a way of creating trust and belonging between people, which also created distance from others.Footnote15 This means that people had to adapt to the level of consumption considered appropriate within the group. The new goods, or rather the habits or practices involved, were modified to the existing conditions and norms of the group before being adopted.Footnote16 However, to conduct consumption in a tasteful and socially adequate way also required a certain skill. This fuelled a fear of being associated with over-consumption or a too-fashionable style in relation to one’s social standing.

The meaning of consumption was also closely associated with the social and practical purposes of households.Footnote17 The organisation of day-to-day life in households, i.e. cookery, eating, cleaning, sleeping and resting, largely decided the meaning of consumption. Households with spacious housing, servants and refined manners preferred different goods to households with only one daily room used for cooking, sleeping, socialising and handicraft production.

The general story of consumption, outlined by Maxime Berg, Daniel Roche, Carole Shammas, Jon Stobart and Lorna Weatherill, reveals that the modern consumer had a growing desire for comfort and fashion. Warmer clothing and housing stimulated the demand for goods that provided more heat, better lighting, more comfortable furniture, and clothes of lighter fabrics.Footnote18 The stronger desire for fashionable consumer goods triggered a transition from expensive and durable items to less durable and cheaper items that were also more sensitive to trends. This could be exemplified by the change from plates of wood or tin to porcelain, or by the transition from heavy woollen fabrics and linens to lighter cotton and half-woollen fabrics.

The goods and their contexts

Given the number of studies on consumption in early modern times it is not possible to do justice to previous research on specific goods. Generally, port cities, which provided an influx of goods, have been identified as important distribution hubs.Footnote19 Anne McCants has shown that the diffusion of tea drinking among Amsterdam’s lower social strata was greatly facilitated by the fact that a low-grade, cheap product was widely available in the 1750s and 1760s.Footnote20 Tea was the Swedish East Indian Company’s main commodity, though a larger share – up to 90 percent – ended up being re-exported or smuggled into the more lucrative British tea market.Footnote21 An observation made in 1777 by a traveller passing through Gothenburg, the homeport of the Swedish East Indian Company, shows that even farmers drank tea, which could be purchased in large quantities and at a low price.Footnote22 Christer Ahlberger, who has studied the consumption of tea, coffee and porcelain, points out that tea seems to have been a common commodity among the peasants in the coastal area near to Gothenburg around 1800.Footnote23

Tea and coffee had a similar and early spread in Norway’s northern coastal area, which has been explained by households’ involvement in the European fish trade.Footnote24 Apart from Gothenburg, which had a high inflow of foreign goods, tea mainly remained a beverage for townspeople and the upper classes, while coffee soon became a beverage for the people.Footnote25 Ahlberger estimates that the number of coffee consumers in western Sweden increased almost sevenfold between 1800 and 1850. The expansion is largely explained by changes in the supply. Leos Müller points out that although the price of tea fell continuously during the 18th century, it remained both more expensive and less accessible than coffee.Footnote26

When the British government reduced its taxes on tea and increased its own imports in the 1780s, the Swedish East Indian Company lost almost its entire market, and it ended completely in 1813.Footnote27 Coffee, on the other hand, entered a new phase when Sweden began exporting iron to several newly independent South American states.Footnote28 Back home, the ships were loaded with coffee, cotton, sugar and other goods. The importing of coffee multiplied in the first half of the 19th century. According to the number of import bans, coffee seems to have troubled the government more than tea.Footnote29 The last sumptuary law on coffee ceased in 1823.Footnote30 Ragnhild Hutchison explains that Norway experienced a similar ‘coffee boom’ due to rising availability and falling prices on the world market. In the 1820s, coffee had almost become a product for everyday use in both Norway and Sweden.Footnote31

The consumption of porcelain was closely associated with the culture of tea. The influx of goods stimulated European manufacturers to begin their own production. An early example is the Dutch production of finer faience in Delft – the ‘Dutch Delftware’. The first Swedish production of genuine porcelain started in 1760, half a century after the establishment of the Meissen factory. Ahlberger’s study points out that the demand for porcelain was strong and socially widespread in western Sweden before the turn of the 1800s.Footnote32 Plates were rare among farmers and peasants in 1750, but no longer unusual around 1800. However, genuine porcelain was long considered a luxury when compared to faience and stoneware.Footnote33

The use of worsted fabrics and silk fabrics was related to the supply of cotton. In the words of John Styles, nothing did more to change the way ordinary people dressed in 18th-century England than the introduction of cotton fabrics.Footnote34 Cotton fabrics with colourfast patterns, first used in curtains, quilts and pillowcases in wealthier homes, were initially shipped from India. By the end of the 18th century, large cotton-printing undertakings had developed in England, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland. Soon, European goods had replaced the imports of Indian printed cotton.Footnote35 The wood-block printing technique eventually made it possible to produce printed fabrics at lower costs. In terms of fashion, this printing technique made it easier for the producers to respond to market trends and adapt their products to demand in different layers. During the 18th century, lighter, cheaper and washable cotton pushed aside heavier worsted and expensive silk fabric in fashionable dress.

A number of European studies have shown that households across all social strata acquired more or better clothes during the 18th century.Footnote36 Decorative accessories, such as aprons and neckerchiefs, became increasingly important, and women’s clothing tended to be more commercially oriented. Roche and de Vries point out that expenditure on clothing increased more quickly than other groups of belongings, and that women spent twice as much as their husbands.Footnote37 In the Nordic countries, these changes mainly occurred during the second half of the 18th century.Footnote38 According to Alan Hutchison’s study of Norwegian ‘fisher-farmers’, the amount of clothes, and particularly the number of accessories, increased between 1750 and 1800.Footnote39 The ownership of lighter woollen, cotton and silk fabrics increased, while the presence of traditional heavy woollen clothes decreased. Clothing became more varied, and women’s wardrobes changed the most.

In Sweden, state subsidies gave rise to a variety of textile manufacturers. The woollen manufacturers dominated the market and Stockholm became the centre of the production of both cloth and worsted fabrics.Footnote40 The first cotton-printing workshop was set up in Stockholm in 1729.Footnote41 Manufacturing became more sophisticated after 1789, when European Jews were allowed to establish printing workshops.Footnote42 At the same time, trade regulations and sumptuary laws were introduced to restrain people’s consumption. Four major sumptuary laws, based on the idea that different classes had different rights to consume, were published in 1720, 1731, 1766 and 1794.Footnote43 Textiles and clothing were among the most regulated areas.Footnote44 Trade in foreign worsted fabrics was liberalised in 1830.Footnote45 Foreign printed cotton was still subject to trade barriers in the 1840s.Footnote46

The study

The survey area

In Härjedalen, living conditions were largely defined by the area’s mountain scenery and large forests. The province hosted one iron works, Ljusnedals bruk, but had no cities or urban settlements. Population growth was weak but increased after the turn of the 1800s. As in the country in general, this rise took place mainly within the group of landless people (see ). Throughout the whole study period, the population was dominated by landowning farmers. The proportion of households belonging to those of the higher social classes was very small, usually only the households of the priest and the ‘länsman’ coffee boom. In 1830 the population had reached almost 6,000, though this still meant less than one person per square kilometre.

Table 1. The population and number of households in Lillhärdal parish (1760–1830).

The agricultural conditions were poor and livestock farming was the main source of income. The rich highland pastures were used in a transhumance system (whereby livestock was moved to higher, richer pastures in summer and to the valleys in winter), and Härjedalen was part of a larger agricultural system that stretched across Dalarna and southern Norrland.Footnote47 Jesper Larsson, who studied the workforce and use of commons in this area, explains that the opportunity to breed more animals during the summer put pressure on the provision of winter forage, which gave rise to improved farming methods and early mechanisation.Footnote48 With reference to the concept of the ‘industrious revolution’, Larsson considers the area to have been a part of a general Western European pattern of increased work, specialisation and commercialisation. However, the harsh climate made Härjedalen less developed than the eastern part.

There are few records of livestock holding before 1850, but one study claims that the average farm in Härjedalen had ten to fourteen cows, around five young cattle, twenty to thirty sheep and a dozen goats during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote49 A study of probate inventories indicates that the number of cows peaked around 1800.Footnote50 At this time, the area’s livestock farming was observed by foreign travellers. In 1799, Johann Wilhelm Schmidt noted that: ‘Especially in Härjedalen, the cattle give a very fine butter. It is characterized by its good taste and yellow color’.Footnote51 The probate material also includes many incoming and outgoing debts to merchants in commercial towns in Norway and Sweden, indicating that the farmers were involved in the regional trade.Footnote52 Fur and fowl were sold alongside dairy products. The markets took place during the winter, when the farms required less work and when goods could easily be transported by sleigh. Cash, which suggests trading activity, is likewise a common item in the probate inventories. The landowning farm households could maintain a relatively high degree of economic self-sufficiency but were market-oriented and a part of the region’s commercial trade. Altogether, the decades around the turn of the 1800s stand out as a dynamic period during which time the population growth took off and began reshaping the area’s social structure.

Materials and method

The study is primarily based on probate inventories. The obligation to set up probate inventories was formalised in Swedish civil law in 1734. The probate inventory was supposed to cover the households’ entire assets, i.e. both real estate and movable property, although jewellery and clothing were usually regarded as private belongings. The probate inventories are detailed throughout the studied period. For instance, around half of all clothes are described by material. Finer and higher-valued garments are more likely to be described than plainer everyday clothes.

To analyse the farm households’ consumption, comparisons with other groups are essential. Therefore, probate inventories for ‘higher-ranking civil servants’ (ironmasters, clergymen and county officials), ‘länsmän’ and ‘peasants’ (landless crofters, farmhands and maids) are included in the study. The probate inventories for landowning farmers and landless peasants have been selected from one of the area’s largest and most populated parishes in Härjedalen, Lillhärdal. In terms of population structure and livelihoods, the parish can be considered representative of the whole of Härjedalen. As the number of people belonging to the upper social classes was very small, the inventories for senior civil servants and ‘länsmän’ were collected from all ten parishes in Härjedalen. Of these, the parish of Tännäs had a greater share of households dependent on its iron works, while Sveg hosted a few more of the households of county officials. In Härjedalen, a major part of the population was related to the landowning farm households. The ‘länsman’ was a landowning farmer with a commission of trust in legal matters, and most of the crofters were sons and daughters of landowning farmers.

Several factors had a significant impact on whether and to what extent property was reported. Individuals from the lower social strata, who had fewer assets, are in general underrepresented.Footnote53 Landownership was associated with a high probate rate, and in the 1810s nearly 80 percent of farmers left a probate inventory.Footnote54 Since the probate inventories for older people tend to reflect a situation where parts of the property had already been distributed to younger relatives, 65 was set as the upper limit. However, this criterion was not possible to fulfil by the senior civil servants or by the ‘länsmän’. For those older than 65, the presence of real estate and livestock has been used as an indicator of an economically active household. The gender aspect is of importance, since fabrics are included in the study and the probate inventory only covered the deceased’s clothing. The probate rate was in general higher for men than for women.Footnote55 Almost all probate inventories for senior civil servants and ‘länsmän’ – 17 and 16, respectively – were drawn up for men. The probate material for farmers covers 41 men and 42 women. The peasants are represented by 13 men and 6 women. This means that the study covers 135 probate inventories in total.

Farm households’ consumption in relation to others

The overview of the studied goods – objects relating to tea and coffee, porcelain, printed cotton, silk fabrics and worsted fabrics – shows that there were quite significant differences in the possession of goods between the four studied groups (see ).

Table 2. The number of probate inventories including tea and coffee utensils, porcelain, printed cotton, silk fabrics and worsted fabrics, Härjedalen (1760–1820).

Regarding tea, all senior civil servants owned belongings associated with tea drinking. For example, in 1763 the county official Peter Spårnberg in Sveg had four tea kettles in tin or tinplate, five teapots in copper, two cans of tea, two and a half dozen teacups in stoneware, plus a certain storage case – a painted wooden tea table, along with one blue and white tea table cover.Footnote56 The amount of tea present decreased across the social structure. According to the earliest evidence from 1789, only four of the 83 farmers and none of the peasants owned objects relating to tea.Footnote57 The amount of goods relating to coffee followed the same downward trend. Those who owned tea utensils also had coffee cups, coffee grinders and coffee pots. The only trace of coffee drinking within the group of farmers was a copper kettle listed in 1817.Footnote58 Coffee does not seem to have become a popular drink until the 1830s and 1840s. From the 1850s onwards, however, coffee drinking was frequently mentioned in local medical reports – abundant consumption was considered to cause chronic gastritis.Footnote59

Regarding porcelain, some farm households owned one or two pieces as early as the 1760s. Altogether, nearly two thirds of farm households had porcelain – mainly plates, but also dishes for fish and bowls for soup. While farmers had at most around a dozen plates, the senior civil servants could have several dozen different plates. ‘Dutch plates’ (‘Holländertallrik’) and ‘Dutch bowls’ (‘Holländerskål’) were found in 16 probate inventories from the years 1763 to 1792. Only one or two at a time, and none of the households, had both ‘Dutch ware’ and porcelain. ‘Dutch ware’ might refer to Dutch Delftware, but could also be a name for faience, porcelain, stoneware, porcelain or even pottery, which are the words used for this category of material. However, ‘Dutch ware’ is unusual in the probate inventories of senior civil servants, but as common as porcelain among the peasants, which points to its status as an alternative to genuine porcelain. The presence of porcelain increased from the 1780s. The findings are in line with Ahlberger’s conclusion that the demand for porcelain was socially widespread before the turn of the 1800s.

Printed cotton, worsted and silk fabrics are mentioned in almost every third probate inventory for ‘länsmän’, farmers and peasants. Since silk and cotton were mainly used in women’s clothing, this overview could be somewhat misleading. This is especially true for the group of senior civil servants, which includes only one woman. During the studied period of time, female fashionable dress was characterised by gowns, petticoats, and jackets in printed cotton and silk.

The use of fabrics differed between the groups. Quilts and curtains in printed cotton were, above all, found in the probate inventories for senior civil servants. Chintz, a printed cotton fabric with a glazed finish, was also used for upholstered chairs. When the master of the iron work Ljusnedal, Johan Hindric Strandberg, died in 1764 he owned two bedcovers and one nightgown in printed cotton.Footnote60 Two of the ‘länsmän’ left three pillowcases and a pair of curtains.Footnote61 The farmers and peasants had no items other than aprons and neckerchiefs in printed cotton. The limited presence of clothing in printed cotton among the senior civil servants and the ‘länsmän’ is probably explained by the shortage of female garments.

Garments in silk are noted in almost all the probate inventories for senior civil servants. When Christina Busk, the wife of the iron master Nils Södergren, died in 1792, she owned neckerchiefs and stockings, several jackets, a robe, and a coat in silk. Footnote62 The men, on the other hand, had velvet breeches, waistcoats, stockings, and nightgowns in silk. This was completely different from the clothes in the probate inventories for famers, who only had frame caps and neckerchiefs in silk. Kristina Rolfsdotter, the wife of a ‘länsman’, was the only one to own a skirt and an apron in silk.Footnote63

The use of worsted fabric was also different between the groups. This was a matter of both type of fabric and type of garment. While the men in the group of iron masters, county officials and clergymen had three-piece-costumes (‘klädning’), breeches, long trousers, waistcoats, and coats in camlet, the men within the categories of ‘länsmän’, farmers and peasants barely had any garments in worsted fabrics. However, the women in these groups had aprons, bodices, and skirts in stripped calamanco or pattern-woven damask. Only four of the probate inventories include garments – one bodice, two skirts and three aprons – in camlet.

The amount of clothes increased for both sexes, especially for women, and the probate material reveals a flourishing market for accessories. During the studied period, the average number of clothes increased from 34 to 62 for the men and from 51 to 81 for the women (see ). Half of the wardrobes consisted of accessories. Women mainly had frame caps, neckerchiefs and aprons, while men mostly had hats, mittens and wristlets. During the studied period, the number of aprons and bodices on average doubled, while the number of handkerchiefs more than tripled from three to eleven items (see ). There were large individual differences. In affluent households, the farmwife could have more than 150 items of clothing, including 20 skirts, 25 neckerchiefs, 15 aprons, 10 bodices and five coats.

Table 3. The number of clothes, skirts, bodices, aprons and neckerchiefs on average (maximum within parentheses) in probate inventories for farm wives sorted by year in Lillhärdal parish (1760–1820).

Purchased fabrics were mainly used for women’s clothing. In 1819, a contemporary source reported that men’s clothes were homespun and mainly made of leather, while women also had broadcloth coats, skirts in satin and other worsted qualities, frame caps in silk and velvet, silk neckerchiefs, and aprons made of cambric and printed cotton.Footnote64 The probate material clarifies that, overall, women’s clothing was of higher value than men’s.Footnote65 Half-woollens were rare in both male and female garments, and cotton was only used for aprons and neckerchiefs.

Overall, the study confirms that farm households in Härjedalen followed the general trend of the increasing consumption of market goods during the second half of the 18th century. The farm households’ consumption of goods differed in various ways from the local elite of clergymen, iron masters, and county civil servants. On the other hand, there were small differences between the groups of farmers and peasants. Compared to previous research, the results show that there were both similarities and differences. The findings regarding tea and coffee utensils correspond to the general view that tea and coffee were mainly consumed by the upper classes during the 18th century. Coffee, which is described as a popular and daily beverage in the 1820s, was still very rare among the farmers even in the 1810s. The findings for porcelain, which is found in all groups and increased over time, are in line with previous studies. The farm households acquired more clothes and increased their consumption of manufactured fabrics and thus followed the general development. However, their choice and use of fabrics shows that they held on to heavier woollens and hardly participated in the ongoing change towards lighter, softer, and less durable quality materials.Footnote66

The farm households’ involvement in the distribution of goods between Norway, Hälsingland and Bergslagen, as well as their own trade in dairy products, furs and fowl, provided them with income that could be spent on a variety of goods that were within their reach. Their consumption increased but remained within the established framework. How can this ‘semi-industrious’ consumer behaviour be explained? The discussion of the reasons and motives behind the farm households’ consumption of foreign and manufactured goods is structured according to social aspects and practical considerations, and the economic perspective is woven into the analysis.

Social aspects of consumption

The study clarifies that the pattern of consumption remained class-oriented throughout the period studied. When the farm economy allowed, new but similar items would be purchased, usually a fabric intended for clothing. Tea and coffee utensils were as common within the households of senior civil servants as they were rare within the strata of farmers and peasants. Higher-ranking civil servants used printed cotton for bedding while farmers and peasants mainly had neckerchiefs and aprons. Of the worsted fabrics, senior civil servants used single-coloured camlet for long trousers, waistcoats and coats, while the farmers and peasants had bodices, waistcoats, aprons, and skirts in colourful calamancoes and flowered damask. (see ) Only porcelain seems to have been a class-neutral item.

Figure 2. A bodice in stripped and figured calamanco, ca 1760–1790. The fabrics sheen and smooth finish indicates that it was made in Norwich, the premier centre for manufacturing worsted fabrics. Photo: Marie Ulväng/Lillhärdals hembygdsförening.

As previously mentioned, the social meaning of consumption was genuinely imbedded in 18th-century society. The century’s four major sumptuary laws trumpeted that position in society decided the level of consumption. How the rules would be applied was a matter for the local authorities at parish level. This made the social meaning of consumption a matter of local circumstances, meaning that the practice differed between regions and depending on the commodity. Overall, though, if people considered the directives to be reasonable and in line with contemporary customs and fashion, they were generally followed.Footnote67

In Härjedalen, the social barriers were both rigid and loose. On the one hand, local circumstances created a firm social barrier between the farmers and the classes above them. On the other, the transhumance system and use of commons to some extent evened out the differences between landowning farmers and landless peasants. However, some households pushed the barriers. Tea and coffee utensils are above all found in probate inventories for the ‘länsmän’, and three of the four farmers who owned teacups were also churchwardens.Footnote68

According to Ahlberger, there were strikingly large differences between the tea drinking habits of urban and rural areas.Footnote69 While drinking tea seems to have been an established habit in Gothenburg as early as 1750, it was still not very common among farmers and peasants in the surrounding countryside by 1850. Ahlberger, who states that tea drinking had a clear connection to class, suggests that the lack of tea consumers within certain lower classes could be interpreted as a deliberate social mark against the upper classes.Footnote70 The explanation is interesting, but it is not relevant to the conditions in Härjedalen, which hardly had any members of the upper classes to interact with. In Härjedalen, most households probably considered tea drinking as something socially unthinkable.

Regarding the use of printed cotton in Härjedalen, the farmers and peasants largely followed the sumptuary law which, until 1813, allowed its use in frame caps, aprons and neckerchiefs only.Footnote71 Silk fabrics were permitted in frame caps and neckerchiefs. Kristina Rolfsdotter, who was both a daughter and a wife of a ‘länsman’, was the only person who owned other garments, an apron and a skirt, in silk. Kristina was also one of two ‘länsmän’ who had pillowcases and curtains of printed cotton.Footnote72 The commission of trust in legal matters gave the ‘länsmän’ an elevated position within the group of landowning farmers. This position included regular meetings with people within the regional state administration. This made it socially acceptable for the ‘länsmän’, who also represented the law, to stretch the norms.Footnote73

Of the studied goods, the new fabrics could be made into garments in familiar cuts, and plates in porcelain had the same function as those of wood. Coffee and tea, however, gave rise to new habits that required some kind of introduction. Compared to coastal areas and in the southern parts of Sweden, the population of Härjedalen, as in the neighbouring areas, was quite homogenous. There was no nobility, and most people were landowning farmers (see ). The involvement in trade contributed to mobility, but this was mainly kept within the same social stratum. The nearest town was around 250 kilometres away and the road system was poor. Beside the church there were few occasions and places where people from different classes met. The small social elite of higher-ranking civil servants meant that craftsmen and servants did not have a function as intermediaries between classes or groups. The parish tailor, who was usually a crofter, did not have any customers other than farmers and peasants.

Figure 3. A bodice in printed cotton, 1820s. It’s high waistline and deep neckline shows that local dress was strongly influenced by the Empire-style. The bodice was worn over a shift and with skirt. Photo: Marie Ulväng/Lillhärdals hembygdsförening.

At the same time, farm households in more dynamic areas quickly adopted new fashions and consumer habits. In Mälardalen, where the farm households traded their crops, large sums were spent on clothing and objects for the home.Footnote74 Long trousers and cotton gowns, as well as porcelain tableware and printed cotton curtains and quilts, were common belongings in wealthier households around the turn of the 1800s. As Alan Hutchison has shown, the Norwegian fishermen-farmers acquired tea and coffee utensils and lighter fabrics for gowns as early as the 1770s. Even so, Hutchison defines their demand as largely within the traditional limits.Footnote75 This behaviour was even more true for the farm households in Härjedalen. Coffee, gowns and long trousers did not break through until the 1830s.Footnote76 When printed cotton began to be used in bodices and waistcoats in the 1820s, they were first used at weddings. (see ) One possible explanation for why very few farmers and no peasants owned items used for drinking coffee or tea may have been that they were simply not used to adopting new goods and habits.

Practical and economic considerations

As mentioned before, domestic trade was highly restricted to cities and periodic markets. This did not prevent rural households from engaging in trade. Alongside the sale of dairy products, the farm households of Härjedalen participated with furs and fowl in the extensive trade between the Norwegian seaport of Trondheim and the mining town of Röros, the linen industry in Hälsingland and the iron works in Bergslagen. This meant that foreign and manufactured goods most likely were within reach.

Until the liberation of trade, peddlers had a key role in the spread of colonial goods and new commodities, as well as in increased consumption in general.Footnote77 Pia Lundqvist, who has studied the Swedish itinerant trade, describes the late 18th century as the beginning of the ‘heyday of peddling’. This expansion responded to social and economic changes within Swedish society but was also in line with the general developments in Western Europe which saw an increasing number of more specialised traders emerge with a wider range of products, although Lundqvist underlines the fact that the Swedish itinerant trade differed significantly from that on the Continent and in Great Britain.Footnote78 There, peddling had a greater connection with cities and merchants and not with the peasantry, as in Sweden. A significant proportion of Swedish peddlers, the so-called Westgothian peddlers (‘Västgötar’) were from rural areas, some distance from Gothenburg.Footnote79 They had the privilege of trading throughout the country, and their business covered most of it: Lundqvist estimates that peddlers reached as many as nine out of ten consumers.Footnote80

A major advantage – for both peddlers and consumers – was that the wares they offered could be adapted to demand within their sales district. Textiles, such as fabrics, aprons and neckerchiefs, were the most common type of goods, but peddlers also brought smaller items such as pipes and pocket watches.Footnote81 Coffee and tea seem to have been unusual goods. In the probate inventories from Härjedalen, woollen textiles named after the Västergötland (‘Västgötatäcke’) province, i.e. the region from which most of the traders originated, were quite common. Until 1847, peddlers were only permitted to trade in home-produced goods, but Lundqvist believes that illegal trading was widespread, and something that peddlers benefited from, as they crossed borders and were harder to supervise.Footnote82 Shortly after the turn of the 1800s, the flow of illegal goods, such as worsted fabrics, led to a restriction that aimed to prevent peddlers entering Norway.Footnote83

The supply of foreign worsted fabrics was linked to the British demand for cotton. Facing competition with the cotton industry at home, weavers in Norwich, the premier centre for manufacturing worsted fabrics, turned their attention to the peasants in the Nordic countries.Footnote84 Thus the Norwich manufacturers produced goods for the Swedish market. Comparisons between garments in museum collections and samples in sales books indicate that Norwich-made worsted fabrics reached Härjedalen through the port of Trondheim.Footnote85 Worsted fabrics were also produced in Stockholm, but the Norwich-made fabrics maintained a superior quality in terms of dyeing, patterning, and, especially, finishing, which made them look like silk. The volume of garments of high-quality worsted fabrics in collections described as striped calamanco, flowered damask or colourful camlott or taboret, points to the fact that the market for worsted fabrics flourished in Härjedalen and neighbouring provinces on both sides of the border at the end of the 18th century.

Recent research on smuggling in late eighteenth-century Sweden by Anna Knutsson indicates that a large proportion of the worsted fabrics on the Swedish market were British, and thus illegal products.Footnote86 Knutson explains that this situation derived from the great demand for finer woollen fabrics, the failure of domestic manufacturers to produce the required sheen and smooth finish of worsted fabric demanded by the domestic market and the lax attitude towards foreign trade.Footnote87 The demand for goods was related to the general flow of goods. Both Ragnhild Hutchison and Alan Hutchison conclude that the Norwegian peasants responded to the consumption acts in neighbouring areas to a high degree. This was probably much the case in Härjedalen. Farm households mainly acquired goods which were widely available and socially accepted in the region.

Whatever the reason for consumption, goods were meant to be used, seen, or shared. For this to be possible, the goods in the survey required different material conditions to be in place, and housing standards played a key role.Footnote88 Since windows became the subject of taxation in the late 1780s it is possible to get an idea of the size of individual dwellings, and so what goods might have been in them.Footnote89 According to the tax roll of 1789, the living conditions of clergymen, iron masters and county civil servants were quite substantial. In 1789, the vicar Pehr Rissler was noted as having ten large and fourteen small windows.Footnote90 The same year, the master of Ljusnedal’s ironworks Nils Södergren was taxed on six large windows and fourteen small windows.Footnote91 The many rooms and their tiled stoves, wallpaper and various pieces of furniture tell us that these were homes where goods, such as cotton quilts and porcelain teacups, could easily have been used and displayed.

The housing conditions of farmers were quite the opposite. More than half of the farm dwellings had only one larger kitchen and one chamber (‘enkelstuga’), and almost a third of the dwellings consisted of two kitchens with an intermediate chamber (‘parstuga’). An official report on housing in Härjedalen in 1818–1821 confirms that the average dwelling was a ‘parstuga’ that sometimes had a loft.Footnote92 Poor housing, cold winters, and difficulties in heating homes meant that all household members, servants included, lived and slept in one of the kitchens – the daily room – during the winter. The other kitchen – the best room – was used occasionally as a room for feasts. The tax rolls and probate inventories show that people with a commission of trust, such as the ‘länsmän’, were more likely to have a larger than average house. The home environment was probably less important in dictating the farmers’ demand for tea and coffee, but it did have significance for their use of textiles. Finer textiles like printed cotton were hard to protect from dirt and wear as long as housing was poor and all household members shared the daily room, and so the most common bed textile was a woollen material lined with sheepskin (‘fälltäcke’). Cotton for bedsheets, tablecloths and curtains began to be used in the 1850s. At that time, earnings from forestry made it possible to rebuild the houses and improve them with stoves, larger windows and insulated floors. The lack of finer goods for the home among the group of crofters, farmhands and maids is likely explained by the poor living conditions and the fact that they were part of other people’s households.

The number of clothes made of manufactured fabric, on the other hand, seems to have reflected many of the purposes they fulfilled in the farmers’ day-to-day lives. In addition to their basic function – to warm and protect – clothes’ visual function as a marker for social belonging, economic capacity and marital status made them a versatile belonging. Accessories such as aprons and neckerchiefs were both decorative and affordable. Compared with tea and coffee utensils, porcelain, beddings and curtains, clothing did not need a home to be displayed. Sunday services were a weekly occasion where people from the whole parish gathered. This provided the best opportunity show off their finery, for whatever reason.

The importance of housing conditions and everyday practice is also prominent in Alan Hutchison’s analysis of the motives behind the fishermen-farmers demand for goods, whose domestic environment was similar to that of the farmers in Härjedalen, and who mainly bought fabrics for clothes.Footnote93 The study indicates that practical aspects, such as the everyday organisation of households, housing conditions and access to social arenas, were of great importance to households’ pattern of consumption. The versatility and durability of fabrics meant that they met many of the farm households’ requirements and wishes.

The price of goods was central in the choice of goods. As several Nordic studies have shown, the price of coffee fell sharply at the beginning of the 19th century, leading to a real boom in coffee drinking. Tea seems to have maintained its exclusiveness, while coffee was adapted to the peasantry’s material culture and practices. In addition to its reasonable price, it contained caffeine and could also be mixed with alcohol, which was a part of the existing local food and drinking culture. As previous mentioned, in Härjedalen, coffee did not become a popular drink until the 1830s and 1840s, however.

The price of goods was central to consumer choices. A few examples will help to get an idea of what different sums meant for households. The Swedish money system changed several times at the end of the 18th century and the monetary value daler kopparmynt, which was replaced by riksdaler banco in 1776, was converted and adjusted for inflation according to the base year 1780.Footnote94

According to a trade record of 1750, 425 grams of Chinese tea cost 1 riksdaler 26 skilling.Footnote95 In the early 1760s, a cow was valued at 4 riksdaler 14 skilling, a goat at 29 skilling, a barrow at 2 riksdaler 42 skilling, and a sheepskin bed covering at 3 riksdaler.Footnote96 A bodice in worsted damask was valued at 1 riksdaler 21 skilling, and an apron in printed cotton at 12 skilling.Footnote97 In the 1780s, when 425 grams of coffee could be purchased for 1 riksdaler 12 skilling, a horse was valued at 12 riksdaler, a cow at 3 riksdaler 16 skilling, and an iron pot 1 riksdaler 32 skilling.Footnote98 A skirt in worsted damask was valued at 1 riksdaler 32 skilling, a silk neckerchief at 16 skilling, and a plate at 2 skilling.Footnote99 The examples are few and approximate, but they do indicate that tea, coffee, and worsted fabrics were relatively expensive, while porcelain and accessories like aprons and neckerchiefs could be purchased at a reasonable cost.

In comparison with tea and coffee, which disappeared when consumed, and fragile porcelain, manufactured fabrics may well have been regarded as an investment. Preserved garments in worsted fabrics show that these fabrics could be used and reused for decades.Footnote100 In the early 19th century, the value of clothing was around 20 percent that of the farm households’ movable property.Footnote101 Clothes were clearly important possessions among the upper social classes as well, but they had more and other ways to communicate status and affiliation. Clothing consequently accounts for a small share in their probate inventories.

Summary

This study of foreign and manufactured goods in the Swedish province of Härjedalen – a remote but central transit area for goods moving between the Norwegian coast and the Swedish settlements of Bergslagen and Mälardalen – shows that households were part of the general historiography of consumption outlined by Berg, Roche, Shammas, Stobart, de Vries and Weatherill, among others. However, the findings of tea and coffee utensils, porcelain, printed cotton, silk fabrics and worsted fabrics show that their pattern of consumption was shaped by the area’s characteristics.

The study has outlined three main features behind the farmers’ consumption. Firstly, the increased number of livestock and evidence of trading activities indicate that Härjedalen underwent a period of increased market participation during the late 18th century. The consumption of market goods also increased during this period. Porcelain became more common and was bought in larger quantities from the 1780s onwards. Above all, farm households increased their consumption of manufactured fabrics for clothing and fashionable accessories. Women’s clothing changed the most. Similar changes have been observed in a number of studies on clothing and consumption both in large urban European settings and Scandinavian rural areas.

Secondly, consumption increased but remained within the traditional and socially restrained framework – defined as ‘semi-industrious’. Manufactured fabrics were added to the wardrobe, but the cut and style of clothes did not change much. The key factor lay in the population structure, consisting mainly of landowning farmers and a few households belonging to the upper classes. With its large forests, lack of cities, and small population size, which meant a density of less than one person per square kilometre, Härjedalen hardly facilitated social interactions. People with different social belongings rarely met to exchange new goods and habits. When the farm economy eventually allowed for more consumption, there was little room for new choices. Goods that could be used in familiar ways, such as woollen fabrics for clothes and porcelain for meals, were more likely to be embraced. Tea and coffee seem to have been unthinkable for most farmers and peasants.

While the upper classes used printed cotton in bedding and curtains, farmers and peasants had neckerchiefs and aprons. Of the worsted fabrics, the upper classes used single-coloured camlet, while the farmers preferred colourful and shiny patterned-woven damask and striped calamancoes. The use of silk fabrics was limited to frame caps and neckerchiefs. Gowns, stockings, trousers, and waistcoats in silk fabrics were clothes for people of the upper classes.

The farmers’ use of printed cotton and silk fabrics continued to follow the sumptuary laws after they had ceased to apply. Coffee drinking did not break through until the 1830s or 1840s, nearly twenty years after the general ‘coffee boom’. However, some households pushed the norms. The small presence of tea and coffee utensils, beddings in cotton, and silk fabrics in clothes, belonged to landowning farmers with a commission of trust in legal matters or within the church.

Thirdly, practical aspects such as housing conditions and the everyday organisation of households, which of course depended on economic conditions, were important for households’ valuation of goods. The larger farm dwellings consisted of two rooms with an intermediate chamber. Poor housing and difficulties in heating meant that all household members, servants included, cooked, slept, socialised, and performed handicrafts in the daily room during the winter. This made it difficult to store large quantities of porcelain and use cotton in textiles for the home. Clothing, on the other hand, did not need a home to be displayed, and the Sunday service was a weekly occasion where people gathered and socialised and could show off to one another.

In terms of some general changes in demand, the dominance of heavy woollens, linen, and leather for clothing, and the lack of cotton and linen in bedding, shows that farm households preferred durable materials and did not look for comfort in terms of lighter and softer materials, which was the general trend. On the other hand, for as long as homes were difficult to heat, heavy woollens and fur provided necessary warmth and comfort. In comparison with tea and coffee, which were consumed, and with fragile porcelain, manufactured fabrics appeared as good long-term investments.

To conclude, from the flow of foreign and manufactured goods that reached Härjedalen, by way of the farmers themselves and through peddlers, farm households picked socially acceptable goods that fitted their practical purposes, i.e. for mainly manufactured woollen fabrics for clothes and printed cotton for aprons and neckerchiefs. Consumption increased over time, but stayed largely within traditional limits. However, their demand for finer quality items, such as worsted fabrics made in Norwich and printed cotton from European undertakings, and their trade and transportation of goods across wider areas, definitely made them part of the ongoing commercialisation process.

Archival materials and digital sources

- Bouppteckningar (probate inventories), Berg, Hede and Svegs tingslag, Landsarkivet i Östersund (ÖLA)

- Mantalslängder (tax rolls), Kronofogden i Härjedalens fögderi, Landsarkivet i Östersund (ÖLA)

- Consumer Price Index for Sweden 1290–2014, Rodney Edvinsson and Johan Södergren, www.scb.se, [2021-03-21]

- Medicinhistoriska databasen, Linköping University Electronic Press, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/db.medhist [2021-03-21]

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Pernilla Jonsson and Dag Bäcklund, the Department of Economic History, Uppsala University and the anonymous reviewers and editors of The History of Retailing and Consumption for their constructive criticism and useful comments on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marie Ulväng

Marie Ulväng has a Doctorate in Economic History and is Associate Lecturer in Fashion Studies at the Department of Media Studies, Stockholm University. Her research interests cover material culture, consumption, livelihood, work and gender during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Notes

1 See for example: Weatherill, Consumer Behaviour; Shammas, The Pre-Industrial Consumer; Brewer and Porter, Consumption and the World of Goods; Berg, Goods from the East; Rönnbäck, “An Early Modern Consumer Revolution in the Baltic”; Ilmakunnas and Stobart, A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe; Rydén, Sweden in the eighteenth-century world: Provincial cosmopolitans.

2 de Vries, “The Industrial Revolution,” 249–70; de Vries, The Industrious Revolution; Van Zanden, “Wages and the Standard of Living,” 176–7.

3 Ogilvie, “Consumption, Social Capital, and the ‘Industrious Revolution’,” 287–325; Allen and Weisdorf, “Was there an ‘Industrious Revolution’,” 715–29.

4 Hallén, Överflöd eller livets nödtorft, 33–7; Lilja and Jonsson, “Inadequate Supply and Increasing Demand,” 4–5.

5 Hutchison, R., “An Industrious Revolution in Norway?,” 5, 17; Hutchison, R., “Bites, Nibbles, Sips and Puffs,” 176; Hutchison, A., “Consumption and Endeavour,” 81.

6 Olofsson, “Till ömsesidig nytta,” 41–93; Knutsson, ”Smuggling in the North,” 148–55.

7 Historisk statistik för Sverige, 44.

8 Ibid., 61–2.

9 Magnusson, “Merkantilismens teori och praktik,” 27–45; Häggqvist, ”On the Ocean of Protectionism,” 54–64.

10 Lindberg, “Borgerskap och burskap,” 28–42.

11 Krantz and Schön, Om den svenska konsumtionen under 1800- och 1900-talen, 10.

12 Svensson, Folklig dräkt, 85–7; Ek, Högkonjunkturer, innovationer och den folkliga kulturen, 3–17.

13 Svensson, Bygd och yttervärld; Bringéus, Människan som kulturvarelse, 81–93.

14 Svensson, Folklig dräkt, 45–6, 91–2.

15 Weatherill, “The Meaning of Consumer Behaviour,” 207–8; Smith, Consumption and the Making of Respectability, 223–37; Müller, “The Merchant Houses of Stockholm,” 24–7, 36–39; Andersson, Stadens dignitärer, 190; Illmakunnas, Ett ståndsmässigt liv, 158–61, 226.

16 Christiansen, “Peasant Adaption to Bourgeois Culture,” 98–99; Liby, “Svensk folkdräkt och folklig modedräkt,” 17–36.

17 Weatherill, “The Meaning of Consumer Behaviour,” 211–17; Roche, A History of Everyday Things.

18 de Vries, The Industrious Revolution, 126–33; Roche, A History of Everyday Things, 107–8, 81–220; Shammas, The Pre-industrial Consumer, 95–100; Stobart, The Comforts of Home in Western Europe.

19 Hutchison, “Exotiska varor som har förändrat vardagen,” 127–33; Müller, “Kolonialprodukter i Sveriges handel,” 243–4; Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen 1, 84–109.

20 McCants, “Exotic goods, Popular Consumption,” 445–8; Blondé and Ryckbosch, “Arriving to a Set Table,” 309–27; North, “Material Delight and the Joy of Living,” 157–9.

21 Müller, “Kolonialprodukter i Sveriges,” 239–40; Häggqvist, “On the Ocean of Protectionism,” 84–5; Hodacs, Silk and Tea in the North, 48–81; Macillop, “A North Europe World of Tea”; Müller, “The Swedish East India Trade and International Markets,” 28–44; Janes, “Fine Gottenburgh Tea,” 223–38.

22 Coxe (1784), quoted in Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen, 99.

23 Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen, 99; Sandgren, “Te till de rika, kaffe till de fattiga?,” 38.

24 Hutchison, A., “Consumption and Endeavour,” 81.

25 Hodacs, Silk and Tea in the North, 13; Müller, “Kolonialprodukter i Sveriges handel,” 243–4; Müller, “The Swedish East India Trade,” 35–37; Hutchison, R., “Exotiska varor som har förändrat vardagen,” 131–2; Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen, 97–9, 109–10; Ahlberger, “Det moderna konsumtionssamhället,” 131–3.

26 Müller, “Kolonialprodukter i Sveriges handel,” 234, 244–5.

27 Ibid., 240.

28 Ibid., 244–5; Hutchison, A., “Exotiska varor som har förändrat vardagen,” 130.

29 Hutchison, A., “Exotiska varor som har förändrat vardagen,” 127–8; Müller, “Kolonialprodukter i Sveriges handel,” 237; Häggqvist, “On the Ocean of Protectionism,” 109; Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 276–82.

30 Lundqvist, “Taste for Hot Drinks,” 8.

31 Hutchison, A., “Bites, Nibbles, Sips and Puffs,” 167–8.

32 Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen, 85–7.

33 Murhem and G. Ulväng. “To Buy a Plate,” 197–8; Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen, 84–5.

34 Styles, The Dress of the People, 109–32; Riello, Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World; Lemire, Cotton. Lemire, Fashion’s favourite.

35 Riello, Cotton, 211, 234–7.

36 Roche, The Culture of Clothing,108–10; Medick, “Une culture de la consideration,” 753–74; Roche, A History of Everyday Things, 211–20.

37 Roche, A History of Everyday Things, s. 213–4; de Vries, The Industrious Revolution, 142.

38 Johnson, I den folkliga modedräktens fotspår; Skauge, Folkedrakt motedrakt folkelig mote; Ulväng, Klädekonomi och klädkultur.

39 Hutchison, A., “Consumption and Endeavour,” 31–2.

40 Schön, “Från hantverk till fabriksindustri,” 138; Nyberg, Till salu, 102–9.

41 Henschen, Kattuntryck, 10–29.

42 Ibid., 44–5; Brismark, “Kattun, kunskap och kontakter,” 171–87.

43 For a discussion on luxury consumption and sumptuary laws in Sweden, see: Runefeldt, Att hasta mot undergången; Andersson, “Dangerous Fashions in Swedish Sumptuary Law”.

44 Rasmussen, “Skräddaren, sömmerskan och modet,” 41–5; Andersson, “Foreign Seductions,” 15–29.

45 Lundqvist, “Marknad på väg,” 196.

46 Lundqvist, “Förbjudna tyger,” 194–6.

47 Larsson, “Fäbodväsendet,” 74–113.

48 Ibid., 372–81, 388–91.

49 Bergström, Raihle and Magnusson, Härjedalen, 91.

50 Ulväng, “Klädekonomi och klädkultur,” 105.

51 Schmidt, Resa genom Hälsingland och Härjedalen, 27.

52 Probate inventories: FII:1 nr 12 1766; AIA:8 nr 29 1770, AIA:9 nr 9 1772; AIA:10 nr 35 1773; AIA:16 nr 13 1787; AIA:21 nr 44 1800; AIA:22 nr 3 1800, Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

53 Lindgren, ‘The Modernization of Swedish Credit Markets, 818; Lilja, “Marknad och hushåll,” 77.

54 Ulväng, “Klädekonomi och klädkultur,” 42.

55 Lilja, “Marknad och hushåll,” 200; Lindgren, “The Modernization of Swedish Credit Markets,” 821; Ulväng, “Klädekonomi och klädkultur,” 43–4.

56 Probate inventory: AIA:6 nr 10 1763, Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

57 Probate inventory: AIA:17 nr 10 1789 (two teacups and one copper teapot); AIA:19 nr 27 1796 (five teacups); AIA:24 nr 73 1806 (two teacups); AIA:27 nr 10 1812 (four teacups), Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

58 Probate inventory: AIA:32 nr 6 1817, Hede tingslag, ÖLA.

59 Provinsialläkarrapporter: Vemdalen 1851, Medicinhistoriska databasen, Linköping University.

60 Probate inventory: F:2 nr 1 1764, Hede tingslag, ÖLA.

61 Probate inventories: AIA: 35 nr 3 1819 (länsman); AIA:10 nr 70 1774 (länsman), Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

62 Probate inventory: AI:13 nr 6 1792, Hede tingslag, ÖLA.

63 Modée, Förordning av den 28 september 1736.

64 Sockenbeskrivningar, 229.

65 Ulväng, “Klädekonomi och klädkultur,” 194–8.

66 Hutchison, A., “Consumption and Endeavour,” 32.

67 Rasmussen, “Skräddaren, sömmerskan och modet,” 45.

68 Probate inventories: AIA:17 nr 10 1788; AIA:19 nr 27 1796; AIA:24 nr 73 1806, Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

69 Ahlberger, Konsumtionsrevolutionen, 101.

70 Ibid., 101–3.

71 Modée, Förordning av den 28 september 1736.

72 Probate inventories: AIA: 35 nr 3 1819 (länsman); AIA:10 nr 70 1774 (länsman), Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

73 See Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 270–271, for a discussion on silk and status.

74 Erikson, “Krediter i lust och nöd,” 138–47; Liby, Kläderna gör upplänningen, 15–16; Nylén, Folkdräkter ur Nordiska museets samlingar, 37.

75 Hutchison, A., “Consumption and Endeavour,” 43.

76 Ulväng, “Klädekonomi och klädkultur,” 106.

77 Lundqvist, “Marknad på väg,” 274–5, 284.

78 Ibid., 26–7, 283; Fontaine, History of Pedlars in Europe, 41, 73–93; Shammas, The Pre-industrial Consumer, 254–8.

79 Lundqvist, “Marknad på väg,” 42–71.

80 Ibid., 271–2; Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 188–193.

81 Lundqvist, “Marknad på väg,” 255–6, 324.

82 Lundqvist, “Förbjudna tyger,” 210; Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 145–7.

83 Lundqvist, “Marknad på väg,” 146, 302.

84 Priestley, The Fabric of Stuffs, 33; Style, The Dress of the People, 112–3; Oldland, “Fyne Worsted Whech”; Hol Haugen, “Virkningsfulle tekstilier,” 125–56; Ulväng, “Klädekonomi och klädkultur,” 106–7; Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 248–9, 252–3.

85 Berit Eldvik, Möte med mode, 44–7; Study visit to Bridewell Museum, Norwich 2009; “Klädedräktens magi,” Interreg Norway-Sweden Project on dress in Tröndelagen and Jämtlands län 1750–1905, Jämtlands läns museum, 2005–2007; Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 254, 259–61.

86 Knutsson, “Smuggling in the North,” 152–6, 250–8.

87 Ibid., 250–1, 272–3.

88 Weatherill, “The Meaning of Consumer Behaviour,” 212–6; Blondé and Ryckbosch, “Arriving to a Set Table,” 314–5.

89 Lext, Mantalsskrivningen i Sverige före 1860, 161–2; Ulväng, G., “Hus och gård i förändring.,” 209.

90 Mantalslängd, Sveg 1789, Vol. 220, Kronofogden i Härjedalens fögderi, ÖLA.

91 Mantalslängd, Ljusnedals bruk 1790, vol. 220, Kronofogden i Härjedalens fögderi, ÖLA.

92 Sockenbeskrivningar, 229.

93 Hutchison, A., “Consumption and Endeavour,” 37–9.

94 “Consumer Price Index for Sweden,” Edvinsson and Södergren.

95 Lagerqvist, Vad kostade det?, 128.

96 Probate inventory: AIA:6 Nr 3 1762, Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

97 Probate inventories: AIB:1 nr 2 1763 (bodice); AIA:6a nr 5 1863 (neckerchief, apron), Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

98 Lagerqvist, Vad kostade det?, 131; Probate inventories: AIA:17 nr 10 1788 (horse); AIA:15 nr 33 1785 (cow, iron pot), Svegs tingslag, ÖLA.

99 Probate inventories: AIA:17 nr 10 1788 (apron, plate, skirt); AIA:15 nr 33 1785 (neckercheif), Sveg tingslag, ÖLA.

100 Eldvik, Möte med mode, 50.

101 Ulväng, Klädekonomi och klädkultur, 144.

Bibliography

- Ahlberger, Christer. “Det moderna konsumtionssamhället.” In Kultur och konsumtion i Norden 1750–1950, edited by Johan Söderberg, and Lars Magnusson, 113–134. Helsingfors: FHS, 1997.

- Ahlberger, Christer. Konsumtionsrevolutionen 1 Om det moderna konsumtionssamhällets framväxt 1750–1900. Göteborg: Humanistiska fakulteten, University of Gothenburg, 1996.

- Allen, Robert C., and Jacob Louis Weisdorf. “Was there an ‘Industrious Revolution’ before the Industrial Revolution? An Empirical Exercise for England, c. 1300–1830.” The Economic History Review 64, no. 3 (2011): 715–729.

- Andersson, Eva, I. “Dangerous Fashions in Swedish Sumptuary Law.” In The Right to Dress: Sumptuary Laws in a Global Perspective, 1200–1800, edited by Giorgio Riello, and Ulinka Rublack, 143–164. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Andersson, Eva I. “Foreign Seductions: Sumptuary Laws, Consumption and National Identity in Early Modern Sweden.” In Fashionable Encounters: Perspectives and Trends in Textile and Dress in the Early Modern Nordic World, edited by Tove Mathiassen Engelhardt, Kirsten Toftegaard, Maj Ringgaard, and Marie-Louise Nosch, 15–29. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2014.

- Andersson, Gudrun. Stadens dignitärer: den lokala elitens status- och maktmanifestation i Arboga 1650–1770. Stockholm: Atlantis, 2009.

- Berg, Maxine, ed. Goods from the East, 1600–1800: Trading Eurasia. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Bergström, Erik, Jan Raihle, and Gert Magnusson. Härjedalen: natur och kulturhistoria. Östersund: Jämtlands läns museum, 1993.

- Blondé, Bruno, and Wouter Ryckbosch. “Arriving to a Set Table: The Integration of Hot Drinks in the Urban Consumer Culture of the 18th-century Southern Low Countries.” In Goods from the East, 1600–1800: Trading Eurasia, edited by Maxine Berg, 309–327. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Brewer, John, and Roy Porter, eds. Consumption and the World of Goods. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Bringéus, Arvid. Människan som kulturvarelse. Malmö: Carlssons, 1986.

- Brismark, Anna. “Kattun, kunskap och kontakter, Judiska influenser inom svensk textilindustri.” In Dolda Innovationer. Textila produkter och ny teknik under 1800-talet, edited by Klas Nyberg, and Pia Lundqvist, 171–187. Stockholm: Kulturhistoriska bokförlaget, 2013.

- Christiansen, Palle. “Peasant Adaption to Bourgeois Culture.” Ethnologia Scandinavica (1978): 98–99.

- de Vries, Jan. “The Industrial Revolution and the Industrious Revolution.” The Journal of Economic History 54, no. 2 (1994): 249–270.

- de Vries, Jan. The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behavior and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Ek, Sven B. Högkonjunkturer, innovationer och den folkliga kulturen. Stockholm: Institutet för Folklivsforskning, 1978.

- Eldvik, Berit. Möte med mode: Folkliga kläder 1750–1900 i Nordiska museet. Stockholm: Nordiska museet, 2014.

- Erikson, Maja. “Krediter i lust och nöd: Skattebönder i Torstuna härad, Västmanlands län, 1770–1870.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2018.

- Fontaine, Laurence. History of Pedlars in Europe. London: Polity Press, 1996.

- Häggqvist, Henric. “On the Ocean of Protectionism: The Structure of Swedish Tariffs and Trade 1780–1830.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2015.

- Hallén, Per. Överflöd eller livets nödtorft: Materiell levnadsstandard i Sverige 1750–1900 i jämförelse med Frankrike, Kanada och Storbritannien. Göteborg: Preindustrial Research Group, 2009.

- Henschen Ingegerd and Ingvar. Kattuntryck: svenskt tygtryck 1720–1850. Stockholm: Nordiska museet, 1992.

- Historisk statistik för Sverige Del 1. Befolkning 1720–1967. Stockholm: SCB, 1969.

- Hodacs, Hanna. Silk and Tea in the North: Scandinavian Trade and the Market for Asian Goods in Eighteenth-Century Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Hol Haugen, Björn Sverre. “Virkningsfulle tekstilier: I östnorske bönders draktpraksiser på 1700-tallet.” PhD diss., Oslo University.

- Hutchison, Alan. “Consumption and Endeavour: Motives for the Acquisition of New Consumer Goods in a Region in the North of Norway in the 18th Century.” Scandinavian Journal of History 39, no. 1 (2014): 27–48.

- Hutchison, Ragnhild. “An Industrious Revolution in Norway? A Norwegian Road to the Modern Market Economy?” Scandinavian Journal of History 39, no. 1 (2014): 4–26.

- Hutchison, Ragnhild. “Bites, Nibbles, Sips and Puffs: New Exotic Goods in Norway in the 18th and the First Half of the 19th Century.” Scandinavian Journal of History 36, no. 2 (2011): 156–185.

- Hutchison, Ragnhild. “Exotiska varor som har förändrat vardagen.” In Global historia från periferin: Norden 1600–1850, edited by Leos Müller, Holger Weiss, and Göran Rydén, 117–135. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 2010.

- Illmakunnas, Johanna. Ett ståndsmässigt liv. Familjen von Fersens livsstil på 1700-talet. Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet, 2012.

- Ilmakunnas, Johanna, and Jon Stobart, eds. A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe: Display, Acquisition and Boundaries. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- Janes, Derek Charles. “Fine Gottenburgh Teas: The Import and Distribution of Smuggled Tea in Scotland and the North of England c. 1750–1780.” History of Retailing and Consumption 2, no. 3 (2016): 223–238.

- Johnson, Seija. “I den folkliga modedräktens fotspår: Bondekvinnors välstånd, ställning och modemedvetenhet i Gamlakarleby socken 1740–1800.” PhD diss., Jyväskylä University, 2018.

- Knutsson, Anna. “Smuggling in the North: Globalisation and the Consolidation of Economic Borders in Sweden, 1766–1806.” PhD diss., European University Institute, 2019.

- Krantz, Olle, and Lennart Schön. Om den svenska konsumtionen under 1800- och 1900-talen: två uppsatser. Lund: Ekonomisk-historiska institutionen, Lund University, 1984.

- Lagerqvist, Lars. Vad kostade det? Priser och löner från medeltid till våra dagar. Lund: Historiska Media i samarbete med Kungl. Myntkabinettet, 2015.

- Larsson, Jesper. “Fäbodväsendet 1550–1920: Ett centralt element i Nordsveriges jordbrukssystem.” PhD diss., Sveriges lantbruksuniv, Uppsala, 2009.

- Lemire, Beverly. Fashion’s Favourite: the Cotton Trade and the Consumer in Britain, 1660–1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Lext, Göran. Mantalsskrivningen i Sverige före 1860. Göteborg: Elander, 1968.

- Liby, Håkan. Kläderna gör upplänningen: Folkligt mode – tradition och trender. Uppsala: Upplandsmuseet, 1997.

- Liby, Håkan. “Svensk folkdräkt och folklig modedräkt.” In Modemedvetna museer: Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok 2010, edited by Christina Westergren, and Berit Eldvik, 17–35. Stockholm: Nordiska museets förlag, 2010.

- Lilja, Kristina, and Pernilla Jonsson. “Inadequate Supply and Increasing Demand for Textiles and Clothing: Second-Hand Trade at Auctions as an Alternative Source of Consumer Goods in Sweden, 1830–1900.” Economic History Review 73, no. 1 (2020): 75–105.

- Lilja, Kristina. “Marknad och hushåll: Sparande och krediter i Falun 1820–1910 utifrån ett livscykelperspektiv.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2004.

- Lindberg, Erik. “Borgerskap och burskap: Om näringsprivilegier och borgerskapets institutioner i Stockholm 1820–1846.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2001.

- Lindgren, Håkan. “The Modernization of Swedish Credit Markets, 1840–1905: Evidence from Probate Records.” The Journal of Economic History 62, no. 3 (2002): 810–832.

- Lundqvist, Pia. “Taste for Hot Drinks: The Consumption of Coffee and Tea in Two Swedish Nineteenth-Century Novels.” History of Retailing and Consumption 2, no. 3 (2016): 1–22.

- Lundqvist, Pia. “Förbjudna tyger: Textilsmuggling till Sverige under 1700- och 1800-talen.” In Dolda Innovationer: Textila produkter och ny teknik under 1800-talet, edited by Klas Nyberg, and Pia Lundqvist, 190–213. Stockholm: Kulturhistoriska bokförlaget. 2013.

- Lundqvist, Pia. “Marknad på väg: den västgötska gårdfarihandeln 1790–1864.” PhD diss., University of Gothenburg, 2008.

- Macillop, Andrew. “A North Europe World of Tea: Scotland and the Tea Trade, ca. 1690–1890.” In Goods from the East, 1600–1800: Trading Eurasia, edited by Maxine Berg, 204–308. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Magnusson, Lars. “Merkantilismens teori och praktik: utrikeshandel och manufakturpolitik i sitt idéhistoriska sammanhang.” In Till salu: Stockholms textila handel och manufaktur 1722–1846, edited by Klas Nyberg, 27–45. Stockholm: Stads- och kommunhistoriska institutet, 2010.

- McCants, Anne E. C. “Exotic Goods, Popular Consumption, and the Standard of Living: Thinking about Globalization in the Early Modern World.” Journal of World History 8, no. 14 (2007): 445–448.

- Medick, Hans. “Une culture de la considération. Les vêtements et leur couleur à Laichingen entre 1750 et 1820.” Annales Historie, Sciences Sociales 50, no. 4 (1995): 753–774.

- Modée, G. Reinhold. Utdrag utur alle ifrån den 7. decemb. 1718. Utkomne publique handlingar … Del I–XV. Stockholm: Förordning av den 28 september, 1736.

- Müller, Leos. “Kolonialprodukter i Sveriges handel och konsumtionskultur, 1700–1800.” Historisk tidskrift 124, no. 2 (2004): 225–248.

- Müller, Leos. “The Merchant Houses of Stockholm, c. 1640–1800: A Comparative Study of Early-modern Entrepreneurial Behaviour”. PhD diss., Uppsala University, 1998.

- Müller, Leos. “The Swedish East India Trade and International Markets: Re-Exports of Teas, 1731–1813.” Scandinavian Economic History Review 51, no. 3 (2003): 28–44.

- Murhem, Sofia, and Göran Ulväng. “To Buy a Plate: Retail and Shopping for Porcelain and Faience in Stockholm During the Eighteenth Century.” In A Taste for Luxury in Early Modern Europe, edited by Johanna Ilmakunnas, and Jon Stobart, 197–215. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- North, Michael. ‘Material Delight and the Joy of Living’: Cultural Consumption in the Age of Enlightenment in Germany. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008.

- Nylén, Anna-Nylén. Folkdräkter ur Nordiska museets samlingar. Stockholm: Almqvist och Wiksells Boktryckeri, 1971.

- Ogilvie, Sheilagh. “Consumption, Social Capital, and the ‘Industrious Revolution’ in Early Modern Germany.” The Journal of Economic History 70, no. 2 (2010): 287–325.

- Oldland, John. “‘Fyne Worsted Whech is Almost like Silke’: Norwich’s Double Worsted.” Textile History 42, no. 2 (2011): 181–199.

- Olofsson, Sven. “Till ömsesidig nytta: Entreprenörer, framgång och sociala relationer i centrala Jämtland ca 1810–1850.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2011.

- Priestley, Ursula. The Fabric of Stuffs: The Norwich Textile Industry from 1565. Norwich: Centre of East Anglian Studies, University of East Anglia, 1990.

- Rasmussen, Pernilla. “Skräddaren, sömmerskan och modet: arbetsmetoder och arbetsdelning i tillverkningen av kvinnlig dräkt 1770–1830.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2010.

- Riello, Giorgio. Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Roche, Daniel. A History of Everyday Things: The Birth of Consumption in France, 1600-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Roche, Daniel. The Culture of Clothing: Dress and Fashion in the Ancien Regime. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Rönnbäck, Klas. “An Early Modern Consumer Revolution in the Baltic?” Scandinavian Journal of History 35, no. 2 (2010): 177–197.

- Runefeldt, Leif. Att hasta mot undergången: Anspråk, flyktighet, förställning i debatten om konsumtion i Sverige 1730–1830. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2015.

- Rydén, Göran. Sweden in the Eighteenth-Century World: Provincial Cosmopolitans. Farnham: Ashgate, 2013.

- Sandgren, Fredrik. “Te till de rika, kaffe till de fattiga?” Unpublished essay, Uppsala University, 2002.

- Schmidt, Johann Wilhelm. Resa genom Hälsingland och Härjedalen år 1799. Trondheim: Luejie, 1992.

- Schön, Lennart. “Från hantverk till fabriksindustri: Svensk textiltillverkning 1820–1870.” PhD diss., Lunds University, 1979.

- Shammas, Carole. The Pre-Industrial Consumer in England and America. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.

- Skauge, Jon Fredrik. Folkedrakt motedrakt folkelig mote: Klesskikk i Ordal fogderi og Trondheim by 1790–1835. Trondheim: NTNU, 2005.

- Smith, Woodruff D. Consumption and the Making of Respectability, 1600–1800. New York: Routledge, 2002.

- Sockenbeskrivningar från Jämtland och Härjedalen 1818–1821. Östersund, 1941.

- Stobart, Jon, ed. The Comforts of Home in Western Europe, 1700–1900. London: Bloomsbury, 2020.

- Styles, John. The Dress of the People: Everyday Fashion in Eighteenth-Century England. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

- Svensson, Sigrid. Bygd och yttervärld: Studier över förhållandet mellan nyheter och tradition. Stockholm: Nordiska museet, 1942.

- Svensson, Sigfrid. Folklig dräkt. Lund: LiberLäromedel, 1974.

- Ulväng, Göran. “Hus och gård i förändring: uppländska herrgårdar, boställen och bondgårdar under 1700- och 1800-talens agrara revolution.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2004.

- Ulväng, Marie. “Klädekonomi och klädkultur: Böndernas kläder i Härjedalen.” PhD diss., Uppsala University, 2013.

- van Zanden, Jan L. “Wages and the Standard of Living in Europe, 1500–1800.” European Review of Economic History 3, no. 2 (1999): 175–197.

- Weatherill, Lorna. Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain, 1660–1760. London: Routledge, 1988.

- Weatherill, Lorna. “The Meaning of Consumer Behaviour in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England.” In Consumption and the World of Goods, edited by John Brewer, and Roy Porter, 206–227. London: Routledge, 1993.