ABSTRACT

This paper focuses on contemporary retail history, analysing trends in ground floor retail occupancy within King Street, Manchester, UK, from 1967 onwards, through an analysis of Goad shopping centre plan data over this period. The paper also considers the development of recent narratives relating to occupancy and vacancy within this street via documentary analysis of local media coverage. Over the period in question, analysis of occupancy of individual premises reveals a contrasting pattern of continuity and flux, with varying degrees of retail vacancy and the mix of retailers over the period changing from a heterogenous mix to one where fashion retailers predominate. The paper concludes by addressing the utility of a microhistorical approach in terms of explaining the developments in King Street over this period.

Introduction

There has been much commentary about the recent travails of traditional UK urban shopping destinations, arising from shifting customer requirements and retail industry structural changeFootnote1 and the current impact of the Covid-19 pandemic.Footnote2 Consequently, the future for many retailers – and the high streets in which they are located – is shrouded in uncertainty. In such circumstances, we should perhaps be mindful of Hollander’s call for more retail-oriented historical research that could possibly help inform future industry development.Footnote3 Here, contemporary history is arguably more relevant to facilitate the development of such insights. Consequently, in this paper, by taking a longitudinal approach to analysing occupancy in one street in Manchester, UK, since the mid-1960s, we seek to analyse changes in the patterns of retail activity therein, which could potentially shed light on future developments. In taking this approach, we are mindful of the principles of microhistory, whereby focusing on a specific case in great detail can exemplify general concepts.Footnote4

We begin by discussing the concept of microhistory to provide historiographical contextualisation, and then review relevant literature on the concept of ‘the street’ and approaches to ‘writing and thinking’Footnote5 about such places. Here we focus in particular on the street’s commercial spatial dimensions. The final element of our contextualisation describes the particular street in question, namely King Street, Manchester, before outlining the sources that informed our analysis of its retail occupancy from 1967. Our focus then turns to the changing retail mix of this street, the length of time individual premises were occupied by specific retailers, and the related issue of retail vacancy, with discussion of some underlying recent causes in the light of broader changes in retailing in Manchester city centre over the last forty years. In so doing, we build on and extend the work of Warnaby and Medway in this journalFootnote6 (in particular through an analysis of occupancy of individual outlets over time), thereby identifying general lessons consistent with the precepts of microhistory.

Taking a microhistorical perspective

Magnússon and Szijártó posit three particular factors that characterise a microhistoric approach.Footnote7 The first involves the intensive historical investigation of a well-defined smaller object. Reducing the scale of observationFootnote8 to the ‘microscopic’Footnote9 – accomplished through an intensive analysis of documentary material that hopefully reveals factors previously unobservedFootnote10 – enables the intensive historical investigation of a relatively well-defined smaller ‘object’ – often in the form of a singular place.Footnote11 The second characteristic relates to the fact that the objective of such investigation is ‘much more far reaching than that of a case study: microhistorians always look for the answers for “great historical questions”’Footnote12; and proponents of microhistory suggest that it can exemplify general concepts.Footnote13 A further characteristic identified by Magnússon and Szijártó is the stress on agency, whereby actors at the micro-level ‘are not merely puppets on the hands of great underlying forces of history’ but are ‘active individuals’ and ‘conscious actors’.Footnote14

Magnússon and Szijártó also state that an important microhistorical decision relates to the choice of ‘relevant and significant cases’ that form the objects of such microscopic investigation, suggesting that this choice is bound up in the concept of the ‘exceptional normal’ or ‘normal exceptions’.Footnote15 Identifying and selecting the ‘exceptional normal’ is, according to them a ‘decisive moment’, and is, at least in part, informed by the experience of the microhistorian who ‘imagines a general picture, and suddenly recognizes its pattern when meeting a particular case’.Footnote16 It is acknowledged that these terms are somewhat opaque, but in the following sections, we discuss the decision to focus on retail location from a micro-scale perspective,Footnote17 and more specifically a particular street. Here, we would argue that King Street could be regarded as an exceptional normal/normal exception due to it being long regarded – and described as – one of Manchester city centre’s most important retail locations. Kidd describes King Street, Market Street and St Ann’s Square in the early-Victorian period as constituting Manchester’s ‘respectable business and retail quarter’Footnote18; and from a more contemporary perspective the Manchester City Centre Strategic Plan 2015–2018 notes that King Street is ‘still considered to be one of the city’s most aspirational retail areas’,Footnote19 notwithstanding its recent problems (which we discuss in greater detail below).

‘Writing’ the street: Taking a retail perspective

Twenty years ago, Hankins stated that the street has been somewhat neglected as a specific site for retail research in comparison with other spatial contexts,Footnote20 notwithstanding Hubbard and Lyon’s contention that ‘the street has long been a key laboratory for studies of social life’, especially at the local level.Footnote21 Since then, in his extensive analysis of Maxwell Street, Chicago – in which he discusses ‘writing and thinking place’ more generally – geographer Tim Cresswell describes what he terms ‘local theory’ as ‘both a way of engaging with place and a way of doing theory’, going on to state, that ‘it is different from ways of engaging place that focus on uniqueness and particularity – separating one place from all the others. It is also different from constructing theory that universalizes and generalizes’.Footnote22 This interplay between different spatial scales – and the counterpoint of the particular and the universal – arguably resonates, in a spatial context, with the relationship between the micro-level investigation and the macro-level conclusion that characterises microhistory (and particularly Italian microhistory), as described by Magnússon and Szijártó.Footnote23

Georges Perec states that ‘the parallel alignment of two series of buildings defines what is known as a street’,Footnote24 and suggests that the account of places such as streets should be through the construction of lists of their attributes, including the shops located therein – an approach we adopt in this paper. From a sociological standpoint, Hubbard and Lyon define the street in terms of both form and function.Footnote25 They state most streets are, intrinsically, linear forms that are conduits for various types of flows, which serve to ‘connect people in a variety of significant ways’, and moreover, connect elements of the built environment, ‘providing some form of interaction and relationality’, which may occur at a variety of spatial scales.Footnote26 This is evident in previous work that has discussed the importance of the street to both retail location and operations. Bennison et al., for example, note that retail locations can be examined at various interlinked scales of analysis,Footnote27 from macro-level decisions (e.g. the proposed geographical coverage of a store network), through to the meso-level (e.g. decisions relating to issues such as the delineation of store catchment areas etc.), and even the micro-level of the individual storeFootnote28 – which is of particular relevance to our discussion.

Regarding retail operations, the globalising trends within many supply chains and the internationalisation of retail formatsFootnote29 lead Crewe and Lowe to discuss the emergence of new spatial configurations:

On the one hand the globalisation of retailing continues to weave complex interdependencies between geographically distant locations and tends towards global interconnection and dedifferentiation. On the other hand new patterns of regional specialisation are emphasising the importance of place and reinforcing local uniqueness.Footnote30

Research context: King Street, Manchester

Hubbard and Lyon contend that, ‘if the researcher goes into the field without a clear definition of the street in question, the study may spiral and become one that potentially becomes too socially decontextualized’.Footnote34 Thus, we now provide a spatial contextualisation of the street in question, which fits Moore’s ‘streets of style’ epithet. Recalling the name of a street in Central London mentioned above, and long regarded as one of the pre-eminent locations of luxury shops,Footnote35 King Street has been described as ‘the Bond Street of the North’.Footnote36

King Street is now part of the St Ann’s Square Conservation area,Footnote37 and has 13 listed buildings interspersed along its route.Footnote38 The earliest part of modern Manchester dates to the early twelfth century and was situated on an area of raised land between the rivers Irwell and Irk, in a location that is now occupied by Manchester Cathedral. However, in the early eighteenth century, the centre of the town moved from this medieval area to what became known as St Ann’s Square. In 1708, parliament granted leave to enclose the open pasture land of Acres Field for the building of St Ann’s Church on the condition that the new square should be 30 yards wide to allow the holding of the ‘Acres Fair’, which had been held there since 1229.

Parkinson-Bailey states that St Ann’s Square quickly became a fashionable part of town, and by 1735 the south side of the square, parts of King Street (immediately to the south of St Ann’s Square) and Ridgefield were being built upon with elegant brick houses.Footnote39 In 1747, in the first subsequent major development of the town, leases were granted for buildings to be erected on the ground now bordered by Market Street, Cross Street, King Street and Moseley Street – and in 1753 the lower part of King Street started to be built.

King Street has been described as essentially not one but two streets,Footnote40 located either side of Cross Street. King Street to the east of Cross Street (‘Upper King Street’) became the epicentre of the banking industry in the North West of England, with many notable financial institutions located there in buildings that are now listed as being of architectural significance.Footnote41 Today this area predominantly houses commercial office space in the old bank buildings, along with a handful of retailers (mainly food and beverage operators and some premium fashion brands) and a luxury hotel.

However, our analysis is focused on the western part of King Street, between Cross Street and Deansgate. This ‘other’ King Street is described by Reilly as ‘narrow, intimate and devoted to the retail trade’Footnote42 and dates from the 1840s, when the Corporation of Manchester decided to extend King Street through to Deansgate.Footnote43 This part of King Street (‘lower King Street’) was, as mentioned above, well-established as a shopping street by the Victorian period, characterised by upmarket/luxury retailers. Kidd describes the retail geography of this area of Manchester of the period as follows:

The more discerning, because wealthy, shoppers could be found frequenting the most fashionable retailers around St Ann’s Square, and Exchange Street or along lower King Street. These were places of elegant promenade and exclusive shops selling jewellery, fine dresses, millinery, books and pictures. Laden with purchases the weary shopper might seek refreshment in one of the city’s numerous cafes, tea shops and restaurants. Some might come to rest at Parker’s in St Ann’s Square or Meng and Ecker in St Ann’s Passage [linking St Ann’s Square to King Street]. Whilst many more would search out the nearest Lyons.Footnote44

This heyday continued through the early twentieth century: in 1924, Reilly describes that, when moving along Deansgate:

… one rather stumbles into King Street without realising its character. It is not until one has walked along it a little way that one realises its air of leisured civilisation, so different from the other streets in the town. It is certainly not due to the buildings, which throughout are very ordinary. But so they are in Bond Street, London or Bold Street, Liverpool. The fact of course is that good shops in a narrow street have in themselves a very inviting appearance. You are tempted to cross and recross the street and treat it as a form of the Eastern bazaar, which it really is.Footnote45

Taylor et al. state that in Manchester the opening of the Arndale Centre in the late 1970s shifted the centre of retail gravity further towards the area within which King Street is situated.Footnote46 This locale, they suggest, was subject to gentrification processes, pushing up retail values on the back of a surge in development. Prior to the 1970s, lower King Street was a thoroughfare, but in the mid-1970s was designated as access only for vehicular traffic, and by the late 1970s there was an experimental pedestrianisation scheme in force, which became permanent in the early 1980s.

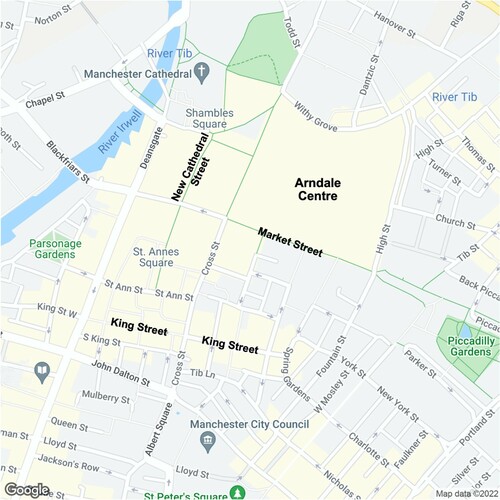

However, in recent years there has been a general perception that King Street’s position as a premier retail location was threatened. The changing pattern of retail development in the city centre – catalysed by the 1996 IRA bombingFootnote47 and the opening of the Trafford CentreFootnote48 out-of-town shopping mall in 1998 – created more locational options for retailers who would have usually gravitated towards King Street. These alternative locations include the redeveloped New Cathedral Street, The Avenue in Spinningfields – an office-led, mixed-use development covering a 22-acre site within the city centre, which is 0.3 miles away to the south of King Street. Established in 2010, The Avenue was described by its developers as ‘Manchester’s first centralised destination for international luxury brands’.Footnote49 Another very attractive location is the extended Arndale Centre, the separate phases of this development opening in October 2005 and April 2006. The characteristics of retail premises in this part of the Arndale Centre were now more in keeping with the locational requirements and customer footfall flows sought by the types of retailers located in King Street – and were made even more attractive to potential tenants when coupled with capital inducements to incentivise relocation there. indicates King Street’s positioning relative to these other retail areas within Manchester city centre.

The 2008–2009 economic crisis saw a significant increase in the number of vacant premises on King Street, which have remained stubbornly high. Unsurprisingly, therefore, ‘[i]mproving the performance of King Street’ was a ‘key priority’ in Manchester’s City Centre Strategic Plan 2015–2018.Footnote50

Research design

The main source of data informing our analysis was Goad shopping centre plans for Manchester, which enabled the tracing of retail occupancy in King Street since their inception in 1967. Goad shopping centre plans of approximately 1000 retail centres of towns and cities throughout the British Isles, (generally with populations over 7500) are regularly updated; larger centres being revised annually and the others biennially.Footnote51 Each Goad shopping centre plan is produced to a uniform scale of 88 feet to one inch (1:1056) and provides a bird’s eye view of the main and subsidiary shopping streets of an urban centre, showing retail fascia names, product/service categories, and the exact location of all retail outlets/vacant premises in terms of their ground floor spatial ‘footprint’ (i.e. frontage and site depths). Other features included relate to the locations of bus stops, subways, pedestrian crossings, one-way traffic flows and pedestrianised areas.Footnote52 Reflecting the limitations of this dataset (Rowley and Shepherd note that Goad plans only record ground floor occupancyFootnote53), we did not analyse the occupancy of the upper storeys of buildings, although observation indicates only one or two of the premises in King Street had retail activity above ground floor level.

The Goad shopping centre plans essentially offer a ‘snapshot’ picture of retail provision in King Street at various times. Plans were analysed at approximately two to three-year intervals from 1967 onwards. Data are reported for the following years: 1967, 1969, 1971, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1980, 1983, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1993, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2018 and 2021. The choice of years was guided by the fact that until the 1980s Goad plans were produced biennially, and thereafter, in relation to Manchester specifically, there are periodic gaps in historic map availability. Their use as a source of spatial data is discussed by Rowley and Shepherd, who note that they ‘provide an excellent opportunity for cross-time comparisons’Footnote54 of retail activity within town and city centres, although Rowley notes that they are ‘by no means perfect’.Footnote55 Indeed, in some of the earlier handwritten maps, details for smaller outlets were illegibleFootnote56 (a drawback rectified in later maps where information is in typescript). Furthermore, Rowley and Shepherd, quoting Berry, note that these plans are essentially descriptive,Footnote57 and that ‘static pattern analysis is incapable of indicating which of a variety of equally plausible but fundamentally different causal processes have given rise to the patterns’.Footnote58

Using Goad shopping centre plans in conjunction with other information sources is also discussed extensively,Footnote59 and following this approach we supplemented our map-based data with documentary analysis of local narratives of the street in the Manchester Evening News and other media forms. This was an attempt to partially overcome the problem of assessing issues of possible causality mentioned above, by seeking to understand the rationale(s) underpinning some of the changes identified from the analysis of Goad plans. Such an approach is particularly apposite when examining data from the early-2000s onwards, when the varying levels of retail vacancy in King Street (arising from more general economic cycles) have resulted in alternating narratives of decline and revival. Quotations from relevant retailers, property industry professionals, place managers and elected officials with an interest in King Street who are mentioned in these media are included below. These insights provide contemporaneous ‘stakeholder’ perspectives on King Street and help to explain, at least in part, some of the trends identified in the analysis of occupancy.

Retail mix

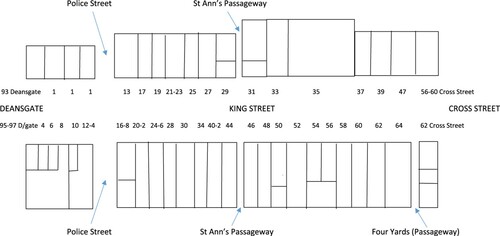

King Street has approximately 40 retail outletsFootnote60 which are represented in schematic form in . In this figure, numbers refer to the street number of each individual retail outlet.

The mix of retailers within King Street has changed over the period of analysis, as shown in and . Product category descriptors are taken from the Goad shopping centre plans – although, where appropriate, some aggregation has occurred (for example, where there are minor inconsistencies in how products sold by the same retailer are described in successive Goad plans).

Table 1. Number of retail outlets by product type in King Street 1967–1993.

Table 2. Number of retail outlets by product type in King Street 1996–2021.

In the late-1960s and through the 1970s, King Street had a quite heterogenous retail mix, consisting of stores covering 18 different product categories. No one product category was predominant, although fashion, footwear, watches/jewellery, financial services, and fur shops were popular. The fur shops had all disappeared by the time of the 1990 Goad plan, undoubtedly reflecting increasing societal concerns about animal rights and cruelty. However, beginning in the mid-1980s (and continuing to its zenith in 2000, with 24 of 39 outlets), fashion retailing became the dominant activity in King Street, reflecting a point made by one property agent in the Manchester Evening News that the Street ‘has been ever changing, and is continuously being re-defined as new tenants come in’.Footnote61 However more recently, whilst still the dominant product category, the number of fashion retailers in King Street has reduced significantly.

Typical of the fashion businesses locating in King Street during the 1990s were those contemporaneously described by Crewe and Lowe as ‘design-oriented, quality women’s fashion retailers who have all successfully positioned themselves between designer stores and the middle market, [and] who retail through a limited number of outlets in a personalised way’.Footnote62 Examples of such retailers cited by Crewe and Lowe include Hobbs Ltd, Monsoon Ltd, Oasis Stores Ltd, Jigsaw and Boules Ltd, all of which have been located on King Street. An important part of the attraction of King Street for these businesses was its upmarket ‘street of style’ reputation. Another important influencing factor was the rising rental levels on the Street. Schofield, in a report in Manchester Confidential, cites one property agent as saying that it has only been national fashion retail businesses that have previously been able to afford – and were prepared to pay – the rents required to have a presence on King Street: and consequently, the Street ‘has never been a seeding ground for smart independent boutiques’.Footnote63

Retail outlet occupation

Occupancy data for ground floor occupancy of individual retail outlets from 1967 is shown in ,Footnote64 which reveal a contrasting pattern of continuity and flux. Some retailers have occupied the same premises for extended periods, notably Hancock’s jewellers which has occupied No. 29 King Street throughout the period of analysis. In addition, there are various examples of retailers expanding and moving premises within King Street. For example, Jaeger occupied No. 14 on Goad plans from 1973, which shows a premises relocation and expansion across the street from Nos. 13–15. After 2017, however, this retailer disappears from plans (Jaeger fell into administration in April 2017). Furthermore, some retailers have relocated from King Street and subsequently returned. Hobbs, for example, is located at No. 27 from the 1986 Goad plan up to 2013, when it relocated to New Cathedral Street (which was part of the post-IRA bomb redevelopment of the city centre). Yet, on the 2017 plan this retailer has returned to the corner of King Street and Deansgate (No. 93 Deansgate). Similarly, Jigsaw is located at Nos. 41–43 King Street in the Goad plans from 1996 to 2000, it then relocated to the redeveloped Triangle facility (i.e. the historic Corn Exchange building in Exchange Square at the top of New Cathedral Street, and again part of the post-IRA bomb city centre redevelopment), only to return to No. 19 King Street by the time of the 2015 Goad plan. However, by the time of the 2021 Goad plan No 19 was again vacant.

Table 3. King Street occupancy by premises 1967–1977.

Table 4. King Street occupancy by premises 1980–1990.

Table 5. King Street occupancy by premises 1993–2003.

Table 6. King Street occupancy by premises 2006–2021.

As mentioned previously, the early/mid-2000s were a time of significant retail change in Manchester, reflecting the development of new retail space targeted at premium retailers in the city centre following property damage sustained in the 1996 IRA bombing. Some previous retail occupants of King Street (e.g. Reiss, Ted Baker) relocated to units opening on New Cathedral Street, near to the new Selfridges and Harvey Nichols department stores. Moreover, by the late 2000s, other locations were also attracting the upmarket retailers formerly located on King Street. One news story in the Manchester Evening News quotes the Chief Executive of CityCo (Manchester’s city centre management organisation) as saying ‘It’s unfortunate that King Street has suffered with the expansion of retail in the city centre’.Footnote65 Relating to this issue, one property letting agent is quoted by Schofield in the media blog Manchester Confidential as follows:

Many shops are finding times tough and those who have the opportunity to do so are looking round for better deals … Existing shopping centres and new retail developments, for example Manchester Arndale and Spinningfields, have been wooing existing retailers with rent-free periods and numerous incentives.Footnote66

This has had implications for how King Street has been perceived, with media reports describing it as having been ‘damaged’ as a retail location, and one Manchester retail property specialist quoted as saying: ‘The trouble is that King Street rents just got too expensive’.Footnote67 These high rental levels (perhaps indicative of the street’s former heyday) were linked to the long leasehold periods that some retailers had previously agreed to in more favourable economic times. There appears to have been some recognition of the impact of this – with one property agent quoted in 2009 as saying:

Rents were a problem but we are moving on this … reducing them significantly or at least keeping them at the same level. Many places have had the same rental rates for eight or nine years. We realise that rents have to be sustainable for the retailer, and in some cases rental rates have dipped substantially. For example, there is one unit on the street which has fallen from £165,000 per year to £120,000.Footnote68

For some, another factor militating against King Street in comparison to these newer locational alternatives, is the Street’s architectural character. Schofield goes on to quote a property letting agent on this subject:

… listed buildings have been subject to not only preservation but restoration clauses. In this way national agencies are trying to hang building restoration on tenants moving into properties. Preservation is one thing but should the tenants be asked to actively restore buildings? We have lost lettings on King Street because of this tactic and its cost implications.Footnote69

Whilst there has been a downward movement on rental levels in many cases, the issue of high business rates remains problematic. This has meant that some stores, whilst attracting good volumes of trade, have struggled to achieve profitability. One store manager in King Street is quoted in the Manchester Evening News on this subject, noting: ‘This is without a doubt the best street in Manchester but the high rents and business rates are putting it in real danger’Footnote70; whilst another states, ‘I blame the rents and rates [for the Street’s situation], they are just too high’.Footnote71 Indeed, the extended period between recent rate revaluations has left some retailers facing business rate bills that do not reflect the current trading position and, arguably, the value of the premises they trade from. That said, as mentioned above, landlords have, perforce, had to accept lower rents and shorter tenancy periods in order to get their properties occupied. Consequently, rental levels on King Street are now perceived as more comparable with other areas of the city centre, which perhaps explains the reduction in vacant properties from a peak of nine in the 2010 Goad plan to four in the 2017 plan. We now move to discuss the issue of retail vacancy on King Street in more detail.

Retail vacancy

The level of retail vacancy has been an issue throughout the period of analysis, but has assumed more importance in recent years. Indeed, there were no retail vacancies on King Street for only three of the 22 Goad plans studied, and in most years, there were between one and three empty premises (notwithstanding the six vacancies noted in 1983 and the five empty units in 1993, with both cases marking periods of UK economic recession). Findlay and Sparks suggest that some degree of retail vacancy within urban locales is inevitable, and indeed desirable.Footnote72 Wrigley and Dolega go further, suggesting that retail ‘churn’ is ‘in stable economic conditions … essential to accommodate and facilitate often rapidly changing retailer/service-provider requirements’ as they adjust to changing levels of market demand.Footnote73

It has only been in the last 12–14 years that retail vacancy has been a significant perceived issue in King Street, with an increase in the number of empty premises after the 2008–2009 financial crisis and associated recession. Resonating with Findlay and Sparks’ contention that retail vacancy arises from a combination of reasons (comprising both national and local factors, as well as market weakness/readjustment), our documentary analysis identified contributory factors emanating from wider economic conditions (indicated by the frequency and chronology of mentions of increased vacancies being consistent with UK financial downturns), as well as some more specific to the Street’s situation, which those responsible for the management of the Street (and its locale) have had to address.

Such factors include maintaining the physical streetscape and ensuring that the aesthetics of vacant premises were appropriate to the Street’s high-end positioning – as one store manager stated: ‘It doesn’t help that some of the empty shops aren’t properly looked after. They could perhaps put pictures up or allow galleries to use them to improve the look of the street’.Footnote74 Another factor perceived to be militating against any initiative(s) to improve such perceptions was the fragmentation of property ownership on King Street, which meant that developing more ‘strategic’ initiatives to improve the situation – for example, managing the retail mix to ensure an appropriate range of retailers aligned with the Street’s desired market position – was problematic. As one property agent identified in 2013: ‘I believe King Street will come back round soon. I think the key is to bring the retailers together to look after the look of the street and the government needs to lower rates to realistic levels’.Footnote75 However, a more pessimistic note is sounded by Schofield in his analysis of King Street’s woes in Manchester Confidential, which is gloomily entitled ‘The Death of King Street’:

What all parties – the City Council, Cityco, MIDASFootnote76, the landlords – agree is that the King has lost its crown, and that something needs to be done. Unfortunately there seems to be no timeframe for banging heads together and coming up with ideas.Footnote77

Such downbeat assessments – and concern about the fortunes of King Street – have somewhat dominated media narratives in recent years, with Cox’s article in the Manchester Evening News, entitled ‘Crisis in shopping mecca King Street as jewel in shops crown loses its shine’, indicative of the general tone adopted. This story reported how concerns regarding the Street’s ongoing commercial viability have motivated action, citing Manchester City Council’s city centre spokesman, Councillor Pat Karney, as saying:

Maybe King Street has to have a big rethink and reinvent itself and work out where it is in the market place, look at what it is offering. Perhaps it needs more cafés … to give people the full experience.

We don’t want to see any empty shops and I will arrange to meet people with legitimate trading concerns in the town hall to go through the issues. One thing for sure is that we will not let King Street have a slow long-term decline.Footnote78

In 2015, the closure in quick succession of the Tommy Hilfiger, Crombie and (long-standing) Jaeger stores prompted the Manchester Evening News to print an online gallery of King Street’s vacant shops.Footnote81 However, this dynamic can work both ways, in that if a few new lettings occur then a narrative of the Street ‘bouncing back’ can be articulated, which may then develop its own momentum. For example, an article in 2011 describing the fashion retailer Aubin & Wills opening a store on King Street ends by quoting one property agent as saying:

This is another great brand for King Street and continues the progress made during the last 12 months. This letting, along with the French brand The Kooples, who are currently fitting out 50 King Street, will further improve the street and enable us to attract further top names to ensure King Street gets back to its best!Footnote82

We have reduced our rents considerably – in many cases by £60,000 a year because this is about supply and demand. Retailers like Jack Wills, Kath Kidston and Dalvey have moved in recently and we are currently in discussions with seven or eight retailers about five very good units which I [am] confident we will fill this year.Footnote83

Such positive narratives have been helped by the fact that, from 2016, there has been an annual King Street Festival over a weekend in early June.Footnote84 This has created a focus of attention on the Street, consistently bringing around 20,000 extra people to the area, which CityCo states is a 65% uplift on a standard, non-event weekend. In fact, towards the end of the period under study (but prior to the Covid-19 pandemic) the number of vacant retail outlets had fallen, with an attendant narrative of ‘resurgence’ starting to become apparent.Footnote85 Such an example is evident in an article from the Manchester Evening News in May 2017 describing various new store openings over the previous 12 months, entitled ‘King Street is reclaiming its crown in retail royalty’.Footnote86

At the time of writing, the difficulties faced by traditional urban shopping destinations mentioned in the introduction have become more evident in relation to King Street. The last Goad plan analysed (dated January 2021, during the Covid-19 pandemic) indicated that 16 outlets were vacant, with some of the previously occupying retailers (e.g. Cath Kidston) being high-profile casualties of this more hostile trading environment. Moreover, these vacancies include two premises with the most extensive spatial footprints – No. 39, and No. 35 (originally dating from 1736). Perhaps indicative of the changing nature of retail occupancy, this latter building has been used as a pop-up store by Klarna, a Swedish bank providing online financial services.Footnote87 Other vacant premises on the Street are promoted in a way which gives similar emphasis to the availability of their space for short-term, ‘pop-up’ retail use, as well as the more usual, long-term retail occupancy. As a response to the perceived narrative of decline, the King Street Partnership has been created ‘to support communication between stakeholders and promote a clear sense of unity within the multi-ownership street’Footnote88 and property company DTZI has been investing in various premises as part of a long-term strategy of creating a retail-led experiential destination on King StreetFootnote89 – such a strategy could, in part, be seen as a means of overcoming some of the negative implications of the fragmentation of property ownership in the Street mentioned previously.

Concluding comments

Our analysis of King Street reveals a complex picture. On the one hand, a significant degree of fixity is evident, with some premises occupied by a single retailer for many years, and in the case of Hancock’s jewellers, throughout the whole of our period of study. On the other hand, there is also evidence of flux, with other premises occupied by a succession of separate, more short-lived tenants. Moreover, we acknowledge that we may have understated the extent of this flux; in that the periods between our ‘snapshots’ of the retail activity on King Street might have witnessed uncaptured instances of very short-lived retail occupancy within certain premises – a trend that may be more pronounced in the future, with the increased use of ‘pop-up’ activities by retailers, not least as an adaptive response to the impacts of Covid-19 on the high street. The analysis of occupancy data in the Goad plans also indicates a move towards increased homogeneity in terms of the product categories sold by retailers on the Street, and a growing predominance of certain product categories over time.

Roth and Klein suggest that the retail environment should be regarded as an ‘open system’,Footnote90 and this notion arguably has some utility in the spatial micro-context of King Street. For example, we have noted how some retailers have moved away from King Street over the period of study, only to later return. These locational trajectories of individual retailers have been influenced by issues within the wider environment. Taking Bennison et al.’s conceptualisation of retail location decisions occurring at macro-, meso- and micro-levels, we can see evidence of retail change in King Street explained by all three of these scales of resolution. In terms of the macro-level, the increasing preponderance in the 1990s of what Crewe and Lowe term ‘design-oriented, quality women’s fashion retailers’Footnote91 saw them making decisions regarding their country-wide locational network across towns and cities to meet the needs of their perceived target market. At the meso-level, within Manchester city centre there is evidence of the ebb and flow of specific districts in terms of their perceived retail attractiveness, with King Street losing out to newer locational alternatives. At the micro-level, we have noted evidence of retailer relocation within King Street, perhaps arising from expiry of leaseholds on premises and/or other considerations (such as a desire for larger premises).

Clearly, and resonating with Rowley’s critique of the essentially descriptive nature of Goad plans, a key issue here is to understand what motivated these locational changes at the different scalar levels. Unfortunately, without an interrogation of those responsible for decisions made at the time (even in this relatively contemporary context), few explanatory rationales are available, and we are left to tease out the possible motivations from what might called circumstantial evidence. This has been done above through our examination of contemporaneous media narratives, with particular emphasis on retail vacancies and the more recent travails of the street. To investigate this in relation to individual retailers would require a piecing together of historic reports and documentation. Alexander highlights the importance of such archival sources to retail historians, but also notes that, notwithstanding efforts to enhance their accessibility to researchers (for example, through digitisation), such information is not available for all companiesFootnote92 – so in the particular spatial context of a street, such investigations would inevitably be incomplete.

Our analysis also suggests the existence of what could be termed a ‘momentum effect’, where there are evident trends underpinning the retail activity in King Street. An example of this can be seen in the product categories sold, with and showing that between 1983 and 2000 the number of fashion retailers increased from nine to 24, with a subsequent decline in numbers thereafter (partly explained by an increase in the number of health and beauty retailers, and more recently, vacant properties). Evident here also is a trend towards agglomeration, defined in terms of the tendency for competing retailers to locate close to one another, or in a proximate geographical area,Footnote93 thereby establishing clusters of retailers selling similar merchandise. Agglomeration is especially evident with higher order comparison goods, such as fashionFootnote94; in other words, the type of goods sold on King Street. Teller and Elms suggest that agglomerations can evolve (e.g. in traditional urban shopping areas) or be created (e.g. as an explicit part of the planning and design of shopping centres).Footnote95 Indeed, some of the media insights used in our analysis revealed an explicit desire on the part of those managing King Street, and property agents responsible for retail lettings in the area, to create an agglomeration of food and beverage retailers to improve the Street’s consumer ‘draw’ – a more overtly strategic approach, which is consistent with principles of place management exemplified in town centre management schemes and, more recently, business improvement districts.Footnote96 More detailed analysis of the efficacy of deliberate attempts by relevant stakeholders to manage the Street’s retail mix over time is an area for further research.

The ‘momentum effect’ is also evident in the past media narratives about King Street, where, for example, both positive and negative trajectories occur depending on the extent to which stores open or close in quick succession. This has led to the articulation of narratives of areal ‘recovery’ or ‘decline’ for different periods in the past. In terms of future research, it suggests that an analysis of past narratives in local news media archives could reveal additional insights into what management initiatives have been used previously on the Street and which of these may have worked well.

In conclusion, our approach – focusing on recent retailing trends in one particular street in Manchester, consistent with the defining factors of microhistory outlined by Magnússon and Szijártó, and resonating with the prosopographical approach characterising much research into retail history,Footnote97 with its focus on a detailed examination of one street – has enabled a more detailed discussion of the interplay between different spatial scales; not only in terms of the micro-scale impact of more macro-level retail industry changes and broader environmental forces, but also how actors at the localised micro-scale exhibit agency in an attempt to influence their situation in the face of these macro-level changes and forces. Such detailed analysis, consistent with, and informed by, the principles of microhistory, seeks to demonstrate Hollander’s contention that retail-oriented historical research could help inform future industry development. Indeed, we believe that similar research in the future – analysing the ebb and flow of the fortunes of specific micro-locations over time (and potentially going back in time further than our relatively contemporary analysis) – could help identify strategies for urban recovery and development going forward.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gary Warnaby

Gary Warnaby is Professor of Retailing and Marketing, based in the Institute of Place Management at Manchester Metropolitan University. Gary’s research interests focus on the marketing of places (particularly in an urban context), and retailing. Results of this research have been published in various academic journals in both the management and geography disciplines. He is co-editor of Rethinking Place Branding: Comprehensive Brand Development for Cities and Regions (Springer, 2015), Designing With Smell: Practices, Techniques and Challenges (Routledge 2017) and A Research Agenda for Place Branding (Edward Elgar, 2021).

Dominic Medway

Dominic Medway is Professor of Marketing at the Institute of Place Management at Manchester Metropolitan University. Dominic’s work is primarily concerned with the complex interactions between places, spaces and those who manage and consume them, reflecting his academic training as a geographer. He is extensively published in a variety of leading academic journals, including: Environment and Planning A, European Journal of Marketing, Journal of Environmental Psychology, Marketing Theory, Mobilities, Space and Culture, Tourism Management and Urban Geography.

Notes

1 For useful summaries of these impacts, see: Parker et al., “Improving the Vitality and Viability”; and Wrigley and Brookes, Evolving High Streets.

2 See Roggeveen and Sethuraman, “How the COVID-19 Pandemic.”

3 Hollander, “A Rearview Mirror Might Help.”

4 For discussions of the tenets of microhistory, see: Ginzberg, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things”; Levi, “On Microhistory”; Magnússon, “The Singularization of History”; and Magnússon and Szijártó, What is Microhistory: Theory and Practice.

5 See Cresswell, Maxwell Street: Writing and Thinking Place.

6 Warnaby and Medway, “Telling the Story of a Street.”

7 Magnússon and Szijártó, What is Microhistory.

8 Ginzberg, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things.”

9 Levi, “On Microhistory.”

10 Ginzberg, “Microhistory: Two or Three Things”; Levi, “On Microhistory.”

11 Brewer, “Microhistory and the Histories.”

12 Magnússon and Szijártó, What is Microhistory, 5.

13 See Levi, “On Microhistory”; Magnússon, “The Singularization of History.”

14 Magnússon and Szijártó, What Is Microhistory, 5.

15 Ibid., 64.

16 Ibid., 64.

17 For extensive discussions on retail location at the micro-scale, see: Brown, Retail Location; and Brown, “Retail Location at the Micro-Scale.”

18 Kidd, Manchester; A History, 54.

19 Manchester City Council, City Centre Strategic Plan, 71.

20 Hankins, “The Restructuring of Retail Capital and the Street.”

21 Hubbard and Lyon, “Introduction: Streetlife – the Shifting Sociologies of the Street,” 937.

22 Cresswell, Maxwell Street: Writing and Thinking Place, 2.

23 Magnússon and Szijártó, What Is Microhistory.

24 Perec, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, 46.

25 Hubbard and Lyon, “Introduction: Streetlife – the Shifting Sociologies of the Street,” 940.

26 Ibid., 940.

27 Bennison, Clarke, and Pal, “Location Decision Making.”

28 See Brown, Retail Location: A Micro-Scale Perspective.

29 See Dawson, Findlay and Sparks, The Retailing Reader.

30 Crewe and Lowe, “Gap on the Map? Towards a Geography,” 1879.

31 Ibid., 1881 – original emphasis.

32 Fernie et al., ‘The Internationalization of the High Fashion Brand.”

33 Moore, Streets of Style: Fashion Designer Retailing.

34 Hubbard and Lyon, “Introduction: Streetlife – the Shifting Sociologies of the Street,” 940.

35 See: Glennie, “Consumption, Consumerism and Urban Form.”

36 See: Cox, “Crisis at Shopping Mecca King Street.”

38 Described in detail by Clare Hartwell in Pevsner Architectural Guides – Manchester.

39 Parkinson-Bailey, Manchester: An Architectural History.

40 Reilly, Some Manchester Streets and Their Buildings.

41 For further details, see: Hartwell, Pevsner Architectural Guides – Manchester.

42 Reilly, Some Manchester Streets and Their Buildings, 24.

43 Bertramsen, “Rethinking the Victorian Department Store.”

44 Kidd, Manchester; A History, 139.

45 Reilly, Some Manchester Streets and Their Buildings, 24–5.

46 Taylor, Evans, and Fraser, A Tale of Two Cities: Global Changes.

47 On Saturday 15 June 1996 the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) detonated a 1500-kilogram lorry bomb on Corporation Street. This caused significant damage to Manchester city centre which took several years to repair and redevelop.

48 The Trafford Centre is a large (over 180,000 m2) indoor shopping centre and leisure complex five miles west of Manchester city centre.

49 Spinningfields, Spinningfields Manchester Media Information.

50 Manchester City Council, City Centre Strategic Plan, 71.

51 Rowley, “Data Bases and Their Integration.”

52 Ibid.

53 Rowley and Shepherd, “A Source of Elementary Spatial Data.”

54 Ibid., 207.

55 Rowley, “Data Bases and Their Integration,” 476.

56 Our attempts to find the missing information from other sources were fruitless, as local archival services did not hold retail directories (such as Slater’s/Kelly’s Retail Directories) after the late 1960s, in part we assume, because of the availability of Goad shopping centre plans.

57 Rowley and Shepherd, “A Source of Elementary Spatial Data,” 207.

58 Berry, “A Paradigm for Modern Geography,” 3.

59 See: Rowley and Shepherd, “A Source of Elementary Spatial Data”; and Rowley, “Data Bases and Their Integration.”

60 The number of retail outlets in King Street varies over the period of analysis due to amalgamations/ partitions of individual premises. This has implications for the street number of individual premises over time, and in the occupancy data by outlet reported in , we have tried to reflect, as best we can, the number of the outlet given on the specific Goad plan relating to that year.

61 Manchester Evening News (MEN), “Jake quits King Street.”

62 Crewe and Lowe, ‘Gap on the Map? Towards a Geography,” 1881.

63 Schofield, “The Death of King Street.”

64 In , the term ‘Offices entrance’ against a street number refers to access points for the commercial premises on the upper storeys.

65 Cox, “Crisis at Shopping Mecca King Street.”

66 Schofield, “The Death of King Street.”

67 Manchester Evening News (MEN), “Is It Full Circle for Square?”

68 Schofield, “The Death of King Street.”

69 Ibid.

70 It should be noted, however, that there has been an expanded retail discount on business rates during the Covid-19 pandemic for eligible retail properties, hospitality and leisure properties in England – see: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/business-rates-expanded-retail-discount-2021-to-2022-local-authority-guidance.

71 Cox, “Struggling Street Needs a Spanish-Style Makeover.”

72 Findlay and Sparks, The Retail Planning Knowledge Base.

73 Wrigley and Dolega, “Resilience, Fragility and Adaptation,” 2347.

74 Cox, “Struggling Street Needs a Spanish-Style makeover.”

75 Cox, “Crisis at Shopping Mecca King Street.”

76 CityCo is Manchester’s city centre management company. MIDAS is the Manchester Investment and Development Agency Service, the city’s inward investment agency.

77 Schofield, “The Death of King Street.”

78 Cox, “Crisis at Shopping Mecca King Street.”

79 Cox, “Struggling Street Needs a Spanish-Style Makeover.”

80 Heward, “Manchester Restaurant Suri.”

81 Stuart, “Shops on King Street.”

82 Manchester Evening News (MEN), “Aubin & Wills Sign Up.”

83 Cox, “Crisis at Shopping Mecca King Street.”

85 Heward, “Kiehl’s Opens First Stand-Alone Manchester Shop.”

86 Begum, “King Street Is Reclaiming Its Crown.”

88 King Street Partnership, Join King Street.

89 Whelan, “DTZI ‘to Play the Long Game’ on King Street.”

90 Roth and Klein, “A Theory of Retail Change.”

91 Crewe and Lowe, “Gap on the Map? Towards a GEOGRAPHY,” 1881.

92 Alexander, ‘The Study of British Retail History.”

93 Teller, ‘Shopping Streets Versus Shopping Malls.”

94 Brown, ‘A Perceptual Approach to Retail Agglomeration.”

95 Teller and Elms, “Urban Place Marketing.”

96 For a discussion of the concept of town centre management, see: Warnaby, Alexander, and Medway, “Town Centre Management in the UK”; and for business improvement districts, see: Grail et al., “Business Improvement Districts in the UK.”

97 A prosopographical approach to retail research focuses on individual companies/institutions – see Alexander, “Objects in the Rearview Mirror.” However, in this paper, we focus on an individual street.

Bibliography

- Alexander, N. “Objects in the Rearview Mirror Might Appear Closer Than They Are.” International Review of Retail, Consumer and Distribution Research 7, no. 4 (1997): 383–403.

- Alexander, A. “The Study of British Retail History: Progress and Agenda.” In The Routledge Companion to Marketing History, edited by D. G. B. Jones and M. Tadajewski, 155–172. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

- Begum, S. “King Street Is Reclaiming Its Crown in Retail Royalty.” Manchester Evening News, May 27, 2016. Accessed November 11, 2019. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/business/king-street-reclaiming-crown-retail-11388318.

- Bennison, D., I. Clarke, and J. Pal. “Location Decision Making: An Exploratory Framework for Analysis.” International Review of Retail, Consumer and Distribution Research 5, no. 1 (1995): 1–20.

- Berry, B. J. L. “A Paradigm for Modern Geography.” In Directions in Geography, edited by R. J. Chorley, 3–21. London: Methuen, 1973 (Cited in Rowley and Shepherd, 1976).

- Bertramsen, H. “Rethinking the Victorian Department Store: Manchester’s Two Emporia: Kendal Milne and Lewis’s 1836–1890.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Lancaster, 2002.

- Brewer, J. “Microhistory and the Histories of Everyday Life.” Cultural and Social History 7, no. 1 (2010): 87–109.

- Brown, S. “A Perceptual Approach to Retail Agglomeration.” Area 19, no. 2 (1987): 131–140.

- Brown, S. Retail Location: A Micro-Scale Perspective. Aldershot: Avebury, 1992.

- Brown, S. “Retail Location at the Micro-Scale: Inventory and Prospect.” Service Industries Journal 14, no. 4 (1994): 542–576.

- Cox, C. “Crisis at Shopping Mecca King Street as Jewel in Shops Crown Loses Its Shine.” Manchester Evening News, April 1, 2013. Accessed November 5, 2019. http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/crisis-shopping-mecca-king-street-2492039.

- Cox, C. “Struggling Street Needs a Spanish-Style Makeover.” Manchester Evening News, April 2, 2013. Accessed April 9, 2021. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/business-owners-along-king-street-2499556.

- Cresswell, T. Maxwell Street: Writing and Thinking Place. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

- Crewe, L., and M. Lowe. “Gap on the Map? Towards a Geography of Consumption and Identity.” Environment and Planning A 27 (1995): 1877–1898.

- Dawson, J., A. Findlay, and L. Sparks. The Retailing Reader. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Fernie, J., C. Moore, A. Lawrie, and A. Hallsworth. “The Internationalization of the High Fashion Brand: The Case of Central London.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 6, no. 3 (1997): 151–162.

- Findlay, A., and L. Sparks. The Retail Planning Knowledge Base Briefing Paper 13: Retail Vacancy. Stirling: Institute for Retail Studies, 2010. Accessed November 11, 2019. http://www.nrpf.org.uk/PDF/nrpftopic13_vacancies.pdf.

- Ginzberg, C. “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know About It.” Critical Inquiry 20 (1993): 10–35.

- Glennie, P. “Consumption, Consumerism and Urban Form: Historical Perspectives.” Urban Studies 35, no. 5–6 (1998): 927–951.

- Grail, J., C. Mitton, N. Ntounis, C. Parker, S. Quin, C. Steadman, G. Warnaby, E. Cotterill, and D. Smith. “Business Improvement Districts in the UK: A Review and Synthesis.” Journal of Place Management and Development 13, no. 1 (2020): 73–88.

- Hankins, K. “The Restructuring of Retail Capital and the Street.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 93, no. 1 (2002): 34–46.

- Hartwell, C. Pevsner Architectural Guides – Manchester. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

- Heward, E. “Kiehl’s Opens First Stand-Alone Manchester Shop in King Street.” Manchester Evening News, December 9, 2015. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/whats-on/gallery/kiehls-opens-first-stand-alone-10573074.

- Heward, E. “Manchester Restaurant Suri Closes after Just Five Months on King Street.” Manchester Evening News, August 8, 2017. Accessed November 11, 2017. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/whats-on/food-drink-news/suri-restaurant-manchester-closed-king-13448238.

- Hollander, S. “A Rearview Mirror Might Help us Drive Forward: A Call for More Historical Studies in Retailing.” Journal of Retailing 62, no. 1 (1986): 7–10.

- Hubbard, P., and D. Lyon. “Introduction: Streetlife – the Shifting Sociologies of the Street.” The Sociological Review 66, no. 5 (2018): 937–951.

- Kidd, A. Manchester; A History. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing, 2006.

- King Street Partnership. Join King Street. 2021. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://kingstreetmcr.co.uk/join-king-street/.

- Levi, G. “On Microhistory.” In New Perspectives on Historical Writing, edited by P. Burke, 93–113. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1993.

- Magnússon, S. G. “The Singularization of History: Social History and Microhistory Within the Postmodern State of Knowledge.” Journal of Social History 36, no. 3 (2003): 701–735.

- Magnússon, S. G., and I. M. Szijártó. What is Microhistory: Theory and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

- Manchester City Council. City Centre Strategic Plan 2015–2018. 2016. Accessed March 23, 2020. https://secure.manchester.gov.uk/downloads/file/24745/city_centre_strategic_plan.

- Manchester City Council. City Centre Strategic Plan 2015–2018. 2016. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.manchester.gov.uk/downloads/file/24745/city_centre_strategic_plan.

- MEN (Manchester Evening News). “Jake quits King Street.” Manchester Evening News, October 2, 2007. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/business/business-news/jake-quits-king-street-640246.

- MEN (Manchester Evening News). “Is It Full Circle for Square?” Manchester Evening News, August 27, 2009. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/business/business-news/is-it-full-circle-for-square-928360.

- MEN (Manchester Evening News). “Aubin & Wills Sign Up for Store at King Street.” Manchester Evening News, June 28, 2011. Accessed February 9, 2021. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/business/property/aubin–wills-sign-up-864050.

- Moore, C. Streets of Style: Fashion Designer Retailing Within London and New York, 261–277. Oxford: Berg, 2000. Cited in Wrigley, N. and M. Lowe. Reading Retail: A Geographical Perspective on Retailing and Consumption Spaces. London: Arnold, 2002.

- Parker, C., N. Ntounis, S. Millington, S. Quin, and F. R. Castillo-Villar. “Improving the Vitality and Viability of the UK Hight Street by 2020: Identifying Priorities and a Framework for Action.” Journal of Place Management and Development 10, no. 4 (2017): 310–348.

- Parkinson-Bailey, J. J. Manchester: An Architectural History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

- Perec, G. Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. London: Penguin, 1997.

- Reilly, C. H. Some Manchester Streets and Their Buildings. London: The University Press of Liverpool Ltd/Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, 1924.

- Roggeveen, A. L., and R. Sethuraman. “How the COVID-19 Pandemic may Change the World of Retailing.” Journal of Retailing 96, no. 2 (2020): 169–171.

- Roth, V. J., and S. Klein. “A Theory of Retail Change.” International Journal of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 3, no. 2 (1993): 167–183.

- Rowley, G. “Data Bases and Their Integration for Retail Geography: A British Example.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 9, no. 4 (1984): 460–476.

- Rowley, G., and P. M. Shepherd. “A Source of Elementary Spatial Data for Town Centre Research in Britain.” Area 8, no. 3 (1976): 201–208.

- Schofield, J. “The Death of King Street.” Manchester Confidential, November 2, 2009. Accessed February 13, 2021. http://old.manchesterconfidential.co.uk/News/The-Death-of-King-Street.

- Spinningfields. Spinningfields Manchester Media Information. 2009. Accessed November 9, 2011. http://www.spinningfields-manchester.com/downloads.

- Stuart, A. “Shops on King Street.” Manchester Evening News, August 31, 2015. Accessed November 11, 2019. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/gallery/shops-on-king-street-9963726.

- Taylor, I., K. Evans, and P. Fraser. A Tale of Two Cities: Global Changes, Local Feeling and Everyday Life in the North of England. London: Routledge, 1996.

- Teller, C. “Shopping Streets Versus Shopping Malls – Determinants of Agglomeration Format Attractiveness from the Consumers’ Point of View.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 18, no. 4 (2008): 381–403.

- Teller, C., and J. R. Elms. “Urban Place Marketing and Retail Agglomeration Customers.” Journal of Marketing Management 28, no. 5/6 (2012): 546–567.

- Warnaby, G., A. Alexander, and D. Medway. “Town Centre Management in the UK: Review, Synthesis and Research Agenda.” International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 8, no. 1 (1998): 15–31.

- Warnaby, G., and D. Medway. “Telling the Story of a Street: Micro Retail Change in Manchester from the 1960s’.” History of Retailing and Consumption 3, no. 1 (2017): 1–7.

- Whelan, D. “DTZI ‘to Play the Long Game’ on King Street.” Place North West, February 8, 2021. Accessed February 8, 2022. https://www.placenorthwest.co.uk/news/dtzi-to-play-the-long-game-on-king-street/.

- Wrigley, N., and E. Brookes. Evolving High Streets: Resilience & Reinvention. Swindon: Economic & Social Research Council/ University of Southampton, 2014.

- Wrigley, N., and L. Dolega. “Resilience, Fragility and Adaptation: New Evidence on the Performance of UK High Streets During Global Economic Crisis and Its Policy Implications.” Environment and Planning A 43, no. 10 (2011): 2337–2363.