ABSTRACT

Walking in the early morning in London in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries you would have come across a new consumption space, the saloop stall. These stalls operated for only a few hours before being packed away. Yet in their time they offered to labouring Londoners, its watchmen and chimney sweeps, a warm respite. Taking a microhistorical approach, this paper provides the first critical examination of these spaces. It looks to establish the temporality of these stalls and how they were situated in the broader urban routines. It also analyses the role materiality played in establishing these spatialities. This paper looks to reframe the stall’s ceramic cups and hot tea urns, demonstrating how they were crucial to creating a space of labour and sociability, removed from the domestic context they have often been associated with. This research is approached via a wide range of sources such as contemporary literature, visual culture and court testimonies. Consideration is given to material and sensorial attributes; factors that inform the creation and use of this space at every turn. It hopes to provide an example of the value taking a material and sensory-based approach when researching itinerant street traders.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In the early nineteenth-century, the literary critic Z was on a crusade against the poet Leigh Hunt and his contemporaries. Through a series of poetic satires called the Cockney School of Poetry, he attacked the refinement of Leigh and his associates.Footnote1 Crucially, Z used the cockney stereotype to suggest a ‘provincial barbarism specific to the Hunt coterie that might be attached to Londoners’ as David Hill Radcliffe argues on the website Lord Byron and His Times. In his final attack, Z accused Hunt of a love of a peculiar drink, saloop. In this critique, saloop is no longer simply a hot beverage but representative of all of labouring, low-class London. To the point that it becomes woven into the very fabric of the city, ‘gurgle[ing] from the fountains of Cheapside’, this is not simply a drink but a geographic space. The question remains: what was saloop? And to what extent can it be associated with the spaces and habits of labouring Londoners?

Saloop was a creamy beverage made from the powdered roots of orchids, initially imported from the Levant, particularly the Anatolia region.Footnote2 Like other hot beverages that arrived in the seventeenth-century, its growth was first facilitated by trading bodies such as the East India Company. It was originally called salep, however there were various corrupted English terms for the drink.Footnote3 This paper uses the term most frequently used in relation to the stall, saloop. Knowledge soon spread of how native roots, such as the cuckoo flower, could be used as an inexpensive substitution.Footnote4 This was demonstrated in the Methodist Magazine which noted in 1817 that domestic saloop cost around 12% of the price of imported varieties at ‘8d or 10d’.Footnote5

Once purchased, this powder would be mixed with water or milk to create a thick drink, as described in various contemporary cookbooks.Footnote6 These texts also recommended the addition of sugar and spices to season the drink, though it is uncertain that such elements would be included on the saloop stall given the prohibitive cost of sugar in the earlier half of the century.Footnote7 The resulting concoction would have been a subtly flavoured drink. Its delicacy making it perfect for those unwell, as evident from the frequent description of it as ‘good for Weak or Consumptive People’ in such books.Footnote8 A good dish to line the stomach and perhaps set someone up for a day’s work. This paper does not look at saloop’s use as a palliative meal, instead it examines a specific moment and space in saloop's history, of its role in daily London routines and the spaces it created.

Likely facilitated by these affordable domestic sources, saloop consumption grew rapidly between 1740 and 1820, with servings of the drink sold at around a penny. This resulted in the creation of a new consumption space, the saloop stall, selling hot dishes of saloop sometimes accompanied by a thick slice of bread. Mentions of the stalls in the Old Bailey Papers (OBP) are limited, comprising 25 cases in total between the 1740s and 1820s. These cases are a rich seam providing both details about the stalls’ use and material culture by its active participants as well as acting as a barometer of the changing popularity of the stalls. Unfortunately, there is no statistical account of how many stalls were active in the period and with only 25 cases it is difficult to estimate the numbers. An issue perhaps compounded by the fact that the hours during which stalls were active, early in the morning, are less represented within the OBP, with crime recorded more frequently later in the day.Footnote9

However, it is possible to detect some trends. Over two-thirds of these cases occurred after the 1780s, suggesting an increase of stalls within this period. The peak occurring in 1800 with six cases that year before dropping to two cases in the next two decades. In addition, the growing popularity of these stalls is supported by the saloop stalls increasing presence in print media from this moment onwards, such as Rowlandson’s The Cries of London (). Their repeated presence suggesting they were a common sight. Throughout these sources, the stall appears to be a particularly labouring-class space, unlike other consumption spaces that developed at the time. There has been little academic interest shown in saloop beyond its inclusion in economic historian William Gervase Clarence-Smith’s chapter on hot drinks in Food and Globalisation.Footnote10 When referenced, it is often described as a brief novelty, as in the case of Joan Thirsk’s Food in Early Modern England, something this paper will challenge.Footnote11

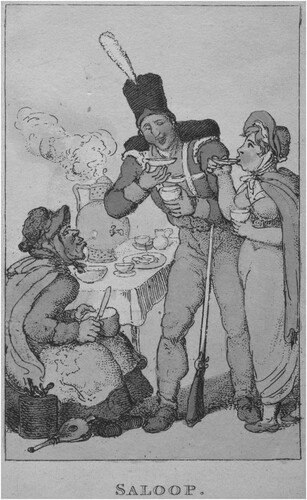

Figure 1. This print gives some sense of the material culture of these spaces, from the bowl on the table to the tools at the seller’s feet. Thomas Rowlandson, Saloop, from Characteristic Sketches of the Lower Orders, London, 1820. Image © British Library Board (C.58.cc.1.(2)).

As little of the stalls’ material culture has survived, an array of sources is needed to reconstruct and analyse this material. Some key sources are pictorial portrayals, such as the genre of prints, The Cries of London, which depict a variety of street hawkers. Additionally, keyword searches of digitised archives including, but not limited to, the British Newspaper Archive and ProQuest revealed just under 20 contemporary writings relating to saloop consumption in London. These dated from the start of the period to the 1860s, from essays by Charles Lamb to anonymous newspaper commentaries. While such materials are not without their issues, these sources are valuable in understanding how the space of the stall and saloop were perceived by society. Further, these writings often contain descriptive details, frequently omitted in the OBP due to its focus on criminal cases.Footnote12

This paper hopes to provide an in-depth analysis of the spatiality of the saloop stall in the streetscape. It offers a microhistorical analysis of the saloop stall, arguing that such case studies allow us to think more broadly about the role of street sellers within London's daily routines and spaces. It uses a design-led methodology to explore the conceptual and physical space of the stall. The common danger of microhistories and commodity biographies is that they craft a ‘grand narrative’, placing the massive responsibility of change onto one item, such as tea.Footnote13 Instead, this paper seeks to place saloop in a dialogue with the broader spectrum of early modern consumption and urban space.

Implicit in this paper's examination of the saloop stall are questions of space and how the spatialities of the stalls were created. Unlike other consumption spaces that grew in the same period, such as the tea garden or coffee house, saloop stalls lacked a defined boundary. Instead, the boundaries of the stall were defined by its material culture.Footnote14 An example of which we can see in the ceramic bowls provided by saloop sellers (see and ). These simple objects would still have influenced a person's experience of space, mooring customers to the space until they finished the drink and returned the bowl they did not own, as in John Richardson's case where he described how he ‘stood at a court in St. Martin's Lane having a pennyworth of saloop’.Footnote15 By limiting Richardson's actions, the bowl helped delineate the socio-geographic space of the saloop stall, creating a unique ‘spatiality’ within the street. It is this material culture, as well as the stall’s attendant sensory elements, that this paper looks to unpick.

Finally, this paper argues for a greater understanding of ephemerality when considering urban streetscapes. Urban spaces underwent immense physical changes in the long eighteenth-century. Improvements in lighting and paving reflected new social practices by the middling and elite such as promenading; as Jon Stobart summarises, ‘society produced space, so space shaped society’.Footnote16 These analyses privilege the built environment and ignore the complexity of the early modern streetscape and its various ephemeral structures.Footnote17 This paper hopes to show how the fleeting structures of these hawkers’ stalls could ‘shape’ the space of the street. This is approached in three parts. Firstly, I will examine who attended the stall and how routine and daily patterns were crucial in solidifying these spaces. The second section will investigate the role of the material culture in shaping these spatialities, focusing on its sensorial effects. The final section will place this material culture in the broader social context and examine what it can suggest about labouring-class engagement with new consumer cultures.

The stall

Saloop stall holders were one of the many itinerant traders that provisioned early modern London. Until the mid nineteenth-century, these sellers helped shape the urban experience whereupon, as Jones argues, many new reforms were aimed at curbing their presence.Footnote18 Over the period there was a general trend away from itinerant vending to more settled informal markets.Footnote19 Often, though not always, sellers operated in a seasonal and temporal manner.Footnote20 This seems to be the case for some sellers such as Tomas Hanvy who in 1785 detailed that he cleaned shoes alongside selling saloop.Footnote21 While it is difficult to know how sellers operated from the limited evidence that survived, it appears many sold saloop on a permanent basis. The majority of the eleven sellers who testified in OBP records referred to themselves as primarily saloop sellers, such as William Miller the elder, who in 1783 stated ‘my business is to sell saloop’.Footnote22 Given the marginal profits to be made of such low-priced dishes, stall holders themselves seem to belong firmly to the labouring classes. As can be inferred from the family occupations of some of the sellers, with Christmas (a shoemaker) and William Miller (a cooper) who described assisting family members with their stalls.Footnote23

Within the limited sample size of the OBP it appears that women were more likely to work as saloop sellers. Of the 17 cases in which the gender of the seller was noted ten of them were women, two were operated by both men and women. Despite the limited sampling there is evidence to suggest this bias was representative of broader trends with stall holders frequently being depicted as old women in illustrations.Footnote24 This predominance of women in this role is not surprising given their prevalence in catering trades. It is less certain if these prints accurately reflected the average age of sellers. There are no explicit references to sellers’ ages but it is clear that some sellers’ ages fell far below that portrayed, such as one woman in 1795 who left her stall under the care of her husband as she laid-in after giving birth.Footnote25

What is clear from OBP records is that the temporal rhythms of the city were central to the experience of the stall. Most saloop sellers rose well before most working Londoners. In this period Londoners generally started work between 6 and 7 am and retired around 10:30 pm unless socialising.Footnote26 While a smaller portion of the cases described selling saloop in the evening, the majority describe operating their stall from the small hours of the morning onwards. For example, in 1789 the seller Catherine Baker recounted leaving to set up her stall at 3:30 am, her routine existing outside of usual behaviour patterns.Footnote27

Who were the customers at this time of day, and why were they drinking saloop? The answer to this question lies in how saloop’s consumption was intertwined with daily routines. This paper will focus on the significant trend of morning consumption, though its other uses bear further study.Footnote28 Saloop is perhaps best understood as a breakfast of convenience, as in the case of John Richardson, who described stopping at a stall on the way to work in 1804.Footnote29 As saloop was affordably priced at a penny or half penny: it fell within the grasp of many labourers, who often would have been reliant, at least in parts, on external food providers.Footnote30 Outside the OBP, this association between breakfast and the saloop stalls frequently appears in articles such as ‘City Scraps’, written in 1864.Footnote31 In this article the writer reflects on the stalls as a breakfast space but explicitly views it as a labouring-class habit, describing how it was so ‘vulgar to breakfast at a street stall’. This connection is less ambiguous in the 1835 Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal article, ‘The Humbler Employments of London’, which described how these stalls started early to supply ‘breakfasts … to many industrious persons whose occupations demand early rising’ and were located in ‘convenient places’ such as by Covent Garden Market.Footnote32

This relationship between saloop stalls and the labouring classes appears to have been deliberately cultivated. These OBP cases fall within the roughly 10 km radius of the centre of London, on the north of the river. When comparing these cases to contemporary maps certain geographic trends become evident. Stalls were often located near areas of industry, with these trends consistent throughout the period.Footnote33 From as early as 1752 to as late as 1802, Saloop stalls were found near the river with at least four located close to wharves. Stalls, such as the one active in Northumberland Gardens by both the Wood & Co and Scotland Yard coal wharves, were in prime positions to catch watermen and the vast shipping workforce that was one of London's largest industries.Footnote34 Stalls located further away from the river also appeared to be near industrial quarters, such as Catherine Baker in 1789, who operated her stall ‘on the corner of Hatton Garden’ in Holborn near both a brewery and a timber yard.Footnote35 Elsewhere the OBP is more explicit as the saloop seller Hannah Shepard described in 1792 how she sat in the same spot for at least three years next to a busy coach yard.Footnote36 That stall holders returned to particular locations supports the argument that they targeted specific audiences.

As apparent from media surrounding them, the audience of the saloop stall was dominated by the labouring poor, such as the 1821 comic novel which described the crowds of dustmen who eagerly received their breakfast.Footnote37 Yet within this there was nuance, as demonstrated in the OBP. A snapshot of its attendees in the first two decades of the 1800s reveals audiences ranged from craftsmen (basket weavers) to labourers (watermen and carters) to those poor enough to steal for a reward of sixpence.Footnote38 One figure who appears throughout the OBP attending stalls, and in depictions of the stalls, , is the Watchman.Footnote39 Frequently, though not always, ill paid watchmen were often associated with the harder, poorer trades of London.Footnote40 Their presence in the stall, both in illustrations and in reality, highlights the perception of the saloop stall as a space for these labouring communities.

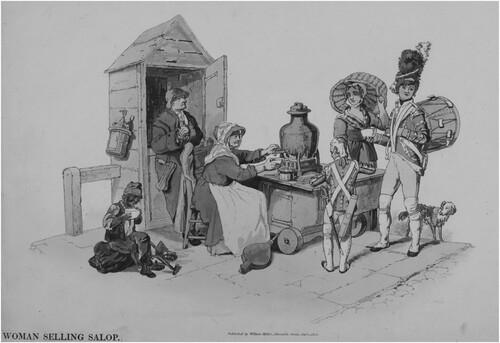

Figure 2. The figures in the image demonstrate the cross-section of society associated with these stalls, specifically its labouring poor. William Henry Pyne, London Street Life by, 1805 image © London Metropolitan Archives (City of London).

Given their ephemerality, it could be tempting to dismiss the stalls as transient. Yet these sellers’ habits reveal a tension within this ephemerality as many street hawkers were established within their neighbourhoods. Despite the saloop stalls’ transitory nature, their permanence in terms of geographical position enabled the sellers to become part of the daily patterns within the streetscapes. When questioned in the OBP, many stallholders referred to selling saloop in consistent and specific locations, such as Abraham Thomas in 1757 and William Miller in 1783.Footnote41 These saloop sellers were not wandering merchants but established in their neighbourhood, part of the city's routines and, as the philosopher Michel de Certeau argued, built the city as much as any architecture.Footnote42 This is demonstrated in the OBP by sellers’ familiarity with the inhabitants of their neighbourhoods. Both Hannah Sheppard in 1792 and Mary Griffiths in 1777 described recognising suspects due to their familiarity with the area, as Sheppard recalled ‘I sit at Mr. Carr's, the corner of St. Paul's Church Yard; I have known the prisoner Pearce three years’.Footnote43 Sheppard’s regularity, and her familiarity with the drivers, all worked to embed her within the space of the neighbourhood.

The senses

Routine was not the only intangible key element of the London streetscape, these were complex intersensory spaces.Footnote44 Senses frequently brought with them associations such as class, helping define spaces in the mental maps of Londoners.Footnote45 As Charlie Taverner asserts, hawkers were vital to constructing these spaces, their sights and sounds giving streets their identity.Footnote46 In turn, these senses also helped construct the specific spatiality of the saloop stall. One particular sense that appeared throughout court records was sight, particularly the sensory perception of the stall's light and its contrast to the darkness in which the saloop sellers often operated. While this period saw reformers, such as John Gwyn, layout plans for new street lighting, the streets of London trailed behind their European counterparts, relying on traditional lighting techniques.Footnote47 New technologies were introduced unevenly, gaslights were only introduced at the end of the period. Complaints regarding lighting quality continued well into the 1870s, often acting more like signposts than true illumination.Footnote48

When faced with morning gloom, light was a crucial aid for saloop sellers. As for many outside the elite, the prohibitive costs of its materials limited light usage to an economic tool.Footnote49 The presence of light is implicitly discernible in the OBP through Londoners’ response to the stall, such as the accused thief William Dixon, who in 1768 turned to a nameless saloop lady to light his candle.Footnote50 Without that light, the stall would be obscured in darkness, hindering access to its equipment and concealing its presence in the street.

But light functioned as much more than a mere tool. It was crucial to defining the space of the stall. As Victoria Kelley argues in her examination of London's informal markets from the mid nineteenth to early twentieth-century, senses and, crucially, perception of light helped define the space of this ‘informal architecture’.Footnote51 Lights were no less critical in the East End markets than they were to the streets of the West End, she argues, highlighting the flaring naphtha lamps that spectacularly illuminated the stalls and helped separate them from the shadowed surrounding streets. This is illustrated by the cases of David Milton and John Cossey, who stopped in 1802 at a saloop stall after successfully pickpocketing Pether Deane.Footnote52 When the watchman Bly was called to testify about his identification of the men, light was the first attribute of the stall that he chose to describe. It was central to how he defined the stall’s space, describing how Milton and Cossey were illuminated, almost spotlit, as they held ‘something like writing-paper towards the light at the stall’.

The sun would have long set by eleven o'clock in October 1802 when Bly sought to trail the figures whom he had heard calling out late at night. The figures were anonymised in the darkness with nothing but their height visible. It was in the stall's light where the figures were identified, and Bly was in turn recognised as the light created a space of reciprocal recognition against the dark unknown. The light bound the stall participants together and encouraged engagement between its participants, such as Milton who invited Bly to take a dish. If later markets’ naphtha lamps’ lights produced a sense of spectacle, then the saloop stalls brazier created a more intimate light. As Wolfgang Schivelbusch argues, ‘any artificially lit area out of doors is experienced as an interior … marked off from the surrounding darkness’.Footnote53 These arguments can be applied to the abovementioned experience of the saloop stall space when lit by the less powerful candle or brazier. It only lit those in its immediate vicinity, while the lack of night vision obscured the space around the stall and created a defined, intimate space.

Sight was not the only sense that helped construct the spatiality of the saloop stall within the street. Touch played its part too, particularly sensations of heat. Warmth was crucial to the saloop stall, from the brazier that warmed the drink and space to the bowls held full of hot saloop. Though reference to warmth is often absent in the OBP, it appears throughout the work of essayists such as Charles Lamb and Henry Mayhew. These sources are not without issues; they are not first-hand accounts and often place the labouring-classes at the bottom of a social and intellectual hierarchy.Footnote54 Despite these biases, they are central to understanding these spaces’ sensory dimensions, often providing a layer of details absent in court records, such as the smell of saloop which attracted passing chimney sweeps and artisans. This element of smell would have been reinforced by the warmth of the stall that billowed out of ‘the grateful steam … with a sumptuous basin’.Footnote55 These descriptions highlight the centrality of warmth to the stall as chimney sweeps gathered around ‘saloop smoking hot’ accompanied by a ‘charcoal grate’. Warmth which would differentiate it from the experience of the broader streetscape.Footnote56

This sense of warmth permeating the stall would likely have attracted customers. The OBP prints and essays show the stalls’ customers were often working some of the hardest, poorest professions. Such a scene was depicted in William Henry Pyne's Costumes of Great Britain in which a watchman, chimney sweep and market hawker attend a saloop stall (). In the accompanying text, Pyne identified the stall's warmth against the bitter London streets as its primary attraction; describing the sellers ‘dealing out gingerbread and warm saloop to their shivering customers, in many a winter storm’.Footnote57 Pyne's illustration reinforced this message, the flaming brazier at the centre and the seller's bellows emphasising the role of heat within the stall space. To understand heat's importance, it is necessary to understand the broader context of access to fuel in the period. While costs dropped over the period, fuel remained, for many, prohibitively expensive, often limiting cooking to once a day.Footnote58 A warm brazier on a cold day might therefore have been attractive to customers who might be dressed in ragged clothing or barefoot, such as Mayhew's chimney sweep.

Perhaps this warmth is what allows us to understand how the saloop stall acted as a social space with visitors staying for conversations as heat, and maybe fellowship, emanated from the stall. As Sara Pennell argues in her research into victuallers in London's early modern period, street food sellers served a deeper need than mere subsistence. Their stalls allowed the labouring-classes to build a wider class-identity and establish bonds, that through shared food and social spaces, ‘the anonymising bonds of labouring life in the capital might be temporarily laid aside’.Footnote59 Throughout my sources the saloop stall was not merely described as a space for quotidian consumption but also as a social space. Some attendees, such as Samuel Plumpton and his companion in 1785, visited the stall as part of their evenings out, while others, like Mary Harwood in 1740, struck up conversations with strangers.Footnote60 This sociability role is perhaps most poetically described in an 1848 article which described a saloop stallholder as ‘in possession of many secrets’ from all the conversations overheard.Footnote61 The stall acted as a continuation of Pennell's developing urban social spaces. Its sensory attributes aided it in this role, from the perception of light that created an intimate space to the sense of warmth from its ruddy grate that attracted people to the space.

In considering the stall as a sociable space it raises questions of gender. As seen elsewhere women were active in this space as sellers but also as customers. Stalls gave individuals a reason to gather on the street, making it a potential venue for trysts. At least in the minds of artists like Rowlandson whose depiction of the stall includes a young lady caught up in a soldier’s charms, , (a popular subject for the artist).Footnote62Additionally, many stalls were active in Drury Lane and Covent Garden, areas popular with sex workers, as their frequent activity lent cover to their work.Footnote63 This highlights the potential for such activities within the stall and at least one attendee confessed to earning her living in this way.Footnote64 These questions of sociability and female presence merit further inquiry as they raise a question of whether the character of the stall fluctuated depending on the time of day the stall was active.

The stall’s social and sensory aspects were facilitated by its material culture, with the brazier at the centre. This use of heating technology was not unique to the saloop stall as many vendors utilised small charcoal braziers to keep various goods warm. Such devices were frequently depicted in contemporary prints, such as the gingerbread seller illustrated in the fittingly named Comfort or the Luxury of Charcoal.Footnote65 The charcoal’s portability the most likely reason it was used in preference to cheaper coal.Footnote66 This wider use of braziers provides context for examining their use (and the accompanying tea-urns) by saloop sellers. It demonstrates that the adaptation of the equipment was not a singular anomaly but part of a growing material culture of street vendors and the labouring classes, though one that has not received attention. While hawkers’ social and economic lives have been analysed, their material culture is only starting to be examined by historians.Footnote67 This material culture brought with it its own design priorities, which raises questions of how these items, such as the saloop stalls’ tea-urn, related to Britain’s broader material culture and of how we can look at this most studied of subjects, tea-ware, in new ways.

Tea-wares

‘Full of saloop and fire under it’ was how Sarah Anderson's tea kettle was described after it was snatched from her as she left to set up her stall in 1784.Footnote68 It was this kettle or tea-urn that formed the centre of her stall and many other stalls, shown in the centre of so many depictions atop the brazier. The cold London street was a far cry from the domestic spaces where these wares were often used and have more frequently been studied. These stalls transformed urns from a tool of polite sociability into a commercial venture. As Arjun Appadurai argues, objects are constantly being redefined: values they bring with them change as they are placed in new contexts. While Appadurai applies these arguments to objects travelling between different cultures, within the saloop stall we see a tale unfold on a micro-level of changing values within the same city, from the tea-table to the street.Footnote69 This section will examine how these goods were reframed through the saloop stall, so it is first necessary to establish their role domestically and their broader social values before analysing how their new roles manifested in design differences.

Tea-urns were part of the myriad new wares that blossomed in the eighteenth-century to facilitate tea consumption and its attendant social practices. These wares were wide and varied with multiple items, such as tea-boilers, tea-kettles and tea-urns, all invented to heat tea with significant crossover in their designs.Footnote70 While Anderson's device was referred to as a kettle, visual representations of the stall depict what we would describe as tea-urns (the term this paper will use for consistency). Early designs for heating tea were technologically simple and were often referred to as Dutch Tea Kettles, kettles with a small lamp underneath.Footnote71 Over time these objects developed with the first recorded English ‘hot water urn’ produced in c.1742.Footnote72 These urns grew in popularity over the next half of the century; their design allowed greater amounts of water to be heated and released via a tap at their base. Such devices were perfectly constructed for new practices of taking tea and had sociability at the heart of their design.

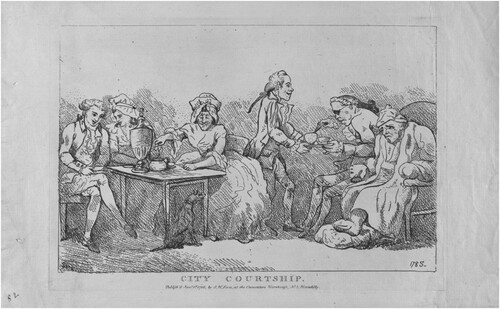

Shaped by their surrounding culture, designed objects act as cultural expressions, containing the potential to reveal their societies’ values.Footnote73 Tea-wares were no exception and were partly shaped by new middling and elite social practices around visiting. Compared to earlier designs, these new tea-urns allowed for a more relaxed visiting experience. Earlier kettle models were placed on a separate stand and required the hostess to repeatedly stand and leave the conversation to collect hot water.Footnote74 Tea-urns reduced this need; the hostess merely turned a tap to fill the teapot as depicted in the print City Courtship (). In addition, tea-urns’ designs could help reinforce class identity. Allowing drinkers to retreat upstairs separated from the kitchen and servants below as Julie Fromer argues, marking one as a space of leisure and the other of labour.Footnote75

Figure 3. The Urn’s easy use is clear in this print as the matron needs only to turn a tap to refresh the stewed leaves in the pot with hot water. Imitator of Thomas Rowlandson, City Courtship, 1786 The Elisha Whittlesey Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (CC0).

The tea-urn's heating system reinforced these values of refined sociability, as it shifted away from the use of lamps to heated iron rods placed in the centre of the urn in the later eighteenth-century. This adaptation allowed tea-urns to follow the more classical urn shape, one which allowed the owner to broadcast their refinement.Footnote76 The desire to display cultural capital was intrinsic to these designs. Indeed, it was their justification for these new systems with the inventor of one, John Wadham, highlighting in his 1774 patent application how this system of rods ‘renders the whole ornamental and agreeable to the sight’.Footnote77 Hot irons further reinforced the connection between these urns and domestic spaces as they were dependent on a fireplace (and likely servants) to heat the irons. These technological choices demonstrate that the tea-urn developed with a clear set of values and purpose: to showcase the host's taste and refinement to visitors within a domestic space.

An analysis of visual culture confirms that tea-urns were linked to values of sociability and domesticity in the cultural imagination of the middling and elite audiences. This can be identified by their use in visual media, from conversation paintings to caricatures, as symbols of wider virtues and refinement, such as in James Gillray’s matrimonial satire Matrimonial-Harmonics ().Footnote78 Here the tea-urn in danger of boiling over represents the tensions within this unhappy marriage, as Gillray played with the object’s association with refinement and domesticity in cultural imagination. It is through this lens of ‘politeness’ and as a reflection of inner refinement that these tea wares have often been analysed.Footnote79 These associations were reinforced by the tea-urn’s design. How then can these ideas of leisure and elite sociability, inherent in the tea-urn, be reconciled with its presence on the saloop stall as an object of commerce within the noisy socio-urban space of a London street?

Figure 4. The use of the tea urn as a visual metaphors in this matrimonial satire by Gillray suggests they were connected to specific values of domesticity in the minds of his audience. James Gillray, Matrimonial Harmonics, 1805. [London: Publisher not named] Image Courtesy of Library of Congress.

![Figure 4. The use of the tea urn as a visual metaphors in this matrimonial satire by Gillray suggests they were connected to specific values of domesticity in the minds of his audience. James Gillray, Matrimonial Harmonics, 1805. [London: Publisher not named] Image Courtesy of Library of Congress.](/cms/asset/5a296628-a592-4209-9bd6-fd9d4dcc0e30/rhrc_a_2178813_f0004_ob.jpg)

These ‘symbolic values’ attached to goods could shift depending on their context and relationship to other goods.Footnote80 Indeed, despite associations with the middling and elite culture, tea-urns could be found throughout the social scale. Tea kettles feature significantly in the recorded list of stolen items in OBP cases, their prevalence suggesting both desirability and growing affordability.Footnote81 A vast array of design elements, such as decoration, size and material, could be adjusted to change the cost of such items. While a gallon-sized silver tea-urn could cost as much as 160 or 147 shillings, depending on decoration, there were examples within the OBP of urns valued at as little as 20 or even 5 shillings.Footnote82 That the 5-shilling urn was described as brown suggests a cheaper material such as copper was used. The usage of these items across the social scale raises the question of whether the significance and value of these objects fluctuated depending where and by whom they were used. Could these changes in value be read in their designs?

Saloop stalls were part of a growing engagement with new hot beverages by the labouring-classes. This emerging consumption did not simply copy dominant middling and elite customs, instead it featured its own patterns and timings, such as beverages taken at work.Footnote83 This difference was exemplified by the use of tea-urns on the saloop stall and street, where they subverted their inherent connections to domesticity. The same properties – heat and large capacity – that allowed women to reduce their work as hostesses made it perfect to use on the streets as an economic tool. Though these sellers’ thoughts have not been recorded, pictorial depictions and other sources suggest these tea-urns underwent conscious design changes. As the seller's priorities changed, these objects underwent a process of vernacularisation.

The designs of saloop tea-urns were not merely copied but adapted to suit the stalls’ needs. There is a sharp difference between tea-urns designed for domestic use and those used on the saloop stalls, where hard-wearing use required them to function efficiently for as long as possible. These depictions show many utilised the various design alterations to make them more affordable. From the common brown colouring to the crude welding marks visible on Pyne's urn, these were rough affairs a world away from the ornate urns that survive in collections like those of the V&A. ‘Ornamental and agreeable to the sight’ they were not, which leads us to their most important difference: heating and the brazier.

As highlighted earlier, heat was crucial to the saloop stalls, both helping to define the space and acting as an attraction. The constant supply of heat was therefore a design priority. While Wadham's design, and others like it, were adapted to domestic spaces, they were impossible to use on the street. Heating irons required a fireplace to warm them. They would cool as they lacked an active heat source. This more aesthetically fashionable technology was therefore rejected for one better suited to the stalls’ spatiality. One which could heat saloop, seller and buyers throughout their long hours spent on the street: the brazier. While no version of non-elite tea-urns survive, they are present throughout visual depictions, the perforated metal and flames indicating their presence. While the description of Sarah Anderson's kettle, ‘with fire under it’, highlights their use within the OBP. This was not a mundane adaptation. It demonstrates a choice by labouring-class sellers to eschew dominant designs and adapt new tea-wares to meet their distinct spaces and practices.

While the saloop stall is just one microhistory, it reveals the complexity within these wares and the need to look at subjects in new ways, particularly regarding class. Indeed, elite objects were frequently hybridised with local culture.Footnote84 In this case, the world of tea-wares merged with the material culture of the street vendors, adding new layers of meaning to the consumption of these goods. Layers which are lost in oversimplified histories of tea or coffee.Footnote85 It can help us understand new spaces in new ways, by prompting us for example to examine the sensory attributes of the saloop stall. Maxine Berg is correct in calling the tea-urn ‘an icon of the eighteenth-century’, but her analysis is limited in only describing its role as a mark of ‘gentility’ in middling and elite social practices.Footnote86 This paper argues it is a far broader ‘icon’ than first imagined, representing the development of new labouring-class practices.

Tea-urns were not the only new wares with which attendees engaged, ceramic dishes formed a key part of the experience. It was in these vessels that the saloop was dished out. No records exist to confirm what particular ceramic was used on the stall, but these wares were most likely creamware.Footnote87 Developed in the 1740s, in response to the demand for new ceramic goods, creamware helped open the market to the labouring class as it could be mass-produced.Footnote88 Cheap but hard-wearing, it was perfect for the stall and the demands of being trekked across London and handed out to strangers.Footnote89 The hardness of this routine is expressed in images such as M Egerton's Street Breakfast, in which cups sit cracked and chipped, a testament to their use.Footnote90 These goods could be sourced at a range of prices from a broad range of suppliers, from warehouses to itinerant traders who operated on an exchange system, swapping old clothes for crockery.Footnote91 Such systems placed these goods within reach of the most straitened traders, such as our typical saloop seller.

The presence of the creamware on the saloop stall serves to underline the increasing accessibility of such wares. With saloop often priced at a penny or a halfpenny, its use would have been prohibited if expensive. The use of these wares grew within the labouring poor, though at a slower rate than other groups.Footnote92 Saloop stalls highlight how increased accessibility was not limited to ownership, though the latter has been the focus of much historical work. It is clear that victualling spaces such as taverns opened up ceramics to new audiences.Footnote93 Creamware was popular throughout the victualling industry in places such as The Kings Arms coffee house in Uxbridge High Street in the 1780s and ‘90s, or in spaces such as Tom's Coffee House.Footnote94 It is important to consider labouring-class engagement in ephemeral spaces because they raise new questions about what engagement meant beyond the confines of ownership.

While caricaturists like Rowlandson mocked attendees using this new material culture, showing figures gauchely ‘saucering’, it is clear that these stalls provided a space for attendees to develop their material knowledge, even if they lacked ownership themselves.Footnote95 These brief engagements with these wares were potent, as Caroline McCaffrey-Howarth notices regarding the use of politically decorated ceramics in taverns.Footnote96 She argues that the combination of such imagery and the specific environment of the tavern meant the wares had the potential to help ‘shape [their] political consciousness’ at a time of limited literacy. While the political dimensions of the saloop stall are unexamined these spaces held similar potential. They allowed labouring customers to develop their material knowledge of new hot beverages and associated goods. Touch would have been key to developing these insights. As it was in the wider retailing space, with shopping spaces allowing customers to engage with new wares.Footnote97 How much greater must that knowledge have been when warmth and taste were added to the experience? Each encounter with the saloop cup was brief, but through the repeated daily routine of the stall, these engagements could accumulate into a wider haptic and material knowledge.

Conclusion

Ephemerality was baked into the material culture of the stall itself: charcoal that would run out, the fire would die down, and the fragile creamware cups would be returned. We should not, as Pennell argues regarding ceramic consumption, fall into the trap of the ‘presumption of object durability’.Footnote98 We must be attuned to the transient nature of materials, which serves to highlight the stall's fleeting experience. The ‘semi-durable’, to use Pennell's term, reflects the stall's contradictory qualities as both an established part of the street and its fundamental impermanence. Though ephemeral, these stalls served an important role and revealed an increasing engagement of labouring Londoners with tea-wares and new material culture. Further, examining the saloop stall as a designed space reveals how wares underwent processes of vernacularisation and that their values were malleable depending on their situation. The tea-urns and creamware used on the stall took on value outside of the roles originally assigned to them. They were not solely tools for middling and elite domestic sociability but helped to craft an altogether different space on the street; enabling the labouring classes to engage with new beverages and social spaces.

These spaces, saloop stalls, would not outlast the early nineteenth-century. The last recorded saloop stall in the OBP was in 1823, and stalls soon passed into cultural memory as a curiosity of the past.Footnote99 This transience does not negate the value of these stalls, neither to their customers nor to those researching them. Though saloop's time was brief, it demonstrated an engagement with the new culture of hot beverages. One which did not simply replicate elite and middling patterns but reimagined material culture in ways that subverted the dominant cultural values and served their own routines. It was this combination of rhythms, senses, and material culture that helped construct the spatiality of the saloop stall within the busy streetscape. Though present for only a few hours, they created a recognisable space and respite for the hawkers, watchmen and chimney sweeps who frequented them. These saloop sellers, like the hot potato vendors, gingerbread makers and other itinerant sellers, helped shaped the urban space, though they did not leave a physical mark.

Saloop stalls disappeared but they paved the way for coffee stalls. While the saloop stall started to fade in the 1820s it was around this time that the coffee stall was first mentioned in the OBP.Footnote100 These spaces started to proliferate using much of the same materials though selling more widely popular beverages such as tea and coffee. This paper proposes that through a microhistory of saloop and ephemeral spaces we can achieve a better understanding of the early modern streetscape. It does not purport to answer all the questions regarding consumption and labouring classes: no single drink could do that. It highlights gaps in the current discussions on consumption, which have perhaps focused too much on tea and the elite and provides more context for further discussions. Saloop stalls were fleeting, ephemeral, spaces yet their legacy of coffee stalls remains with us.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on my MA thesis at the V&A/RCA History of Design, My thanks go to my tutors, the academics at MOLA and archivists the LMA who were so generous with their knowledge as well to the reviewers for their thoughtful comments. Particular thanks go to Alyssa Myers and my tutor Caroline McCaffery-Howarth for their wonderful support and insight.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Freya Purcell

Freya Purcell is a design historian who focuses on social history and urban living in the early modern period. She recently completed the V&A/RCA MA in the History of Design, where her thesis focussed on saloop. She has just completed a researcher in residency for the Archival Network Women Make Cities undertaking original research on Scottish Street sellers and a curatorial traineeship with North Hertfordshire Museum and Curating for Change.

Notes

1 Z, “The Cockney School of Poetry.”

2 Thomas, Treaties, Agreements, and Engagements … , 842, 874 and Peachi, Some Observations Made upon … .

3 This paper has a specifically British focus, however salep continues to be enjoyed in many areas, such as Turkey, where it is often called salep or sahlab.

4 Bryant, Flora Diaetetica, 38–9 among others.

5 Methodist Magazine, “The Works of God Displayed,” 38–9.

6 Nott, The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary and Smith, The Compleat Housewife, 169.

7 Bickham, “Eating the Empire,” 64, 233.

8 Kettilby, A Collection of Above … , 77–8.

9 Voth, “Time and Work in Eighteenth-Century London,” 24.

10 Clarence-Smith, “The Global Consumption of Hot Beverages,” 37–56.

11 Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England, 308.

12 Langbein, The Origins of Adversary, 185.

13 Trentmann, Empire of Things, 79 and Withington, “Where Was the Coffee,” 74.

14 Schatzki, “Timespace and the Organization,” 36–9.

15 OBP, September 1804, George Freak, John Richardson (t18040912-56).

16 Stobart, “Leisure and Shopping in the … ” 481. See also Borsay, “The English Urban Renaissance,” 581–603.

17 Tierney, “Dirty Rotten Sheds,” 235.

18 Jones, “Redressing Reform Narratives,” 62.

19 Kelley, Cheap Street, 51.

20 Pennell, “Great Quantities of Gooseberry Pye,” 235.

21 OBP, June 1785, Thomas Hanvy, (t17850629-114).

22 OBP, July 1783, William William Law, (t17830723-122). Of the other cases, two identified selling alongside doing other work or at certain points of the day, and the remaining two were family members assisting relatives who were primarily identified as saloop sellers.

23 Ibid and OBP, May 1795, Joseph Samuel, (t17950520-42).

24 Of the various prints of stall holders, I examined only one depicted a male vendor in Smith, John Thomas, The Cries of London, plate 28.

25 OBP, Samuel, (t17950520-42).

26 Voth, “Time and Work in Eighteenth-Century London,” 10.

27 OBP, October 1789, William Cunningham, (t17891028-18).

28 A small portion of the cases detail taking saloop late at night as part of drinking such as OBP, September 1785, John Berrow, (t17850914-179).

29 OBP Freak, Richardson (t18040912-56) and similarly the Waterman William Gardner describes taking a morning dish of saloop in OBP, June 1810, Elizabeth Durant, Mary Kite, Elizabeth Ellis (t18100606-70).

30 Pennell, “Great Quantities of Gooseberry Pye,” 230–5.

31 Aleph. “City Scraps,” 3.

32 “The Humbler Employments of London,” 212–13.

33 Cases were compared to John Rocque, A Plan of the Cities of London … and Horwood, Plan of the Cities of London … respectively and can be found mapped on Layers of London under the data set Saloop Sellers of London.

34 Porter, London, 164–6, 171; OBP, September 1768, William Dixon (t17680907-29); OBP, December 1802, David Milton, John Cossey, (t18021201-98); OBP, September 1784, Henry Morgan, (t17840915-1); OBP, Selwood, (t17530607-33); OBP, Hanvy, (t17850629-114).

35 OBP Cunningham, (t17891028-18) similarly the unnamed seller of OBP, April 1807, Mary Berry, (t18070408-93) was located near a cattle yard and brewery.

36 OBP, February 1792, John Lewis, Robert Pearce, (t17920215-7).

37 Egan, Real Life in London, vol ii, 251.

38 OBP, May 1809, William Jones, Moses Fonseca (t18090517-17), OBP, Durant, Kite, Ellis (t18100606-70), OBP, January 1823, Edmund Law, Thomas Webb (t18230115-97) and OBP, May 1805, John Rose (t18050529-41).

39 For example OBP, September 1790, Joseph Pocock, Sarah Watson (t17900915-34).

40 Hitchcock, Down and Out, 154–6.

41 OBP, January 1757, Elizabeth Knotmill, (t17570114-17) and OBP, William William Law, (t17830723-122). Of the eleven sellers who gave testimony five referred to selling in specific locations.

42 De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, 97, 108.

43 OBP, May 1777, John Gibson, (t17770514-29) and OBP Lewis, Pearce, (t17920215-7).

44 Arnout, “Comfort and Safety,” 95.

45 To see more about sense and space see Tullet, Smell in Eighteenth-Century England, 53.

46 Taverner, “Selling Food in the Streets of London,” 124–31.

47 Gwynn, London and Westminster Improved, 17–18 quoted in Ogborn, Spaces of Modernity, 100 and Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night, 88.

48 Otter, Victorian Eye, 221–4.

49 Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night, 7.

50 OBP, Dixon, t17680907-29.

51 Kelley, Cheap Street, 160.

52 OBP, Milton, Cossey, (t18021201-98).

53 Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night, 149 see also Kelley, Cheap Street, 172.

54 Marriott, The Other Empire, 115.

55 Lamb, Essays of Elia, 117–19, unfortunately little other detail is provided as to the character of saloop’s scent.

56 Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, 160.

57 Pyne, Pynes’s British Costumes.

58 Ellis, Coulton, and Mauger, Empire of Tea, 185.

59 Pennell, “Great Quantities of Gooseberry Pye,” 239–40.

60 OBP, September 1785, John Berrow (t17850914-179) and OBP, October 1740, Mary Harwood (t17401015-65).

61 Miller, “Force of Habit,” 404–6.

62 Carter, “Scarlet Fever,” 157–64.

63 Henderson, Disorderly Women, 59.

64 OBP, June 1752, Elizabeth Selwood, Mary M'Daniel, Martha Atkins, (t17530607-33).

65 Charles, Comfort or the Luxury of Charcoal, British Museum see also Ball and Sunderland, An Economic History of London, 12.

66 Pennell, Birth of the English Kitchen, 127.

67 For traditional economic and social histories see Hitchcock, Down and Out, chapter 3; Ball and Sunderland, An Economic History of London, 103; Fontaine, A History of Pedlars in Europe; For historians now considering the material culture of sellers see Taverner, Street Food: Hawkers and the History of London and Susan Curley Meyer, PhD University College Dublin.

68 OBP, May 1784, Joseph Levy, (t17840526-43).

69 Appadurai, The Social Life of Things, 16–17, 44–7.

70 Nancy and Dannehl, Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities.

71 Brown, In Praise of Hot Liquors, 86.

72 Hot Water Urn, “The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection” and Ellis, Coulton, and Mauger, Empire of Tea, 229.

73 Prowen, “Mind in Matter,” 3–5.

74 Wadham, “Tea Fountain or Tea Pot.”

75 Fromer, A Necessary Luxury, 66.

76 Clifford, “Concepts of Invention, Identity and Imitation … ,” 251.

77 Wadham, “Tea Fountain or Tea Pot.”

78 For more on their use in portraiture see Retford, “From the Interior to Interiority,” 291. See also Collet, The Honey-Moon, 1782, Etching, British Museum, London, 1859,0709.675.

79 Richards, Eighteenth-Century Ceramics, 163.

80 Yonan, “Toward a Fusion of Art History … ,” 243.

81 Styles, “Lodging at the Old Bailey,” 72–6.

82 Hughes, “The Georgian Vogue of the Tea-Urn,” 1026–7; OBP, July 1787, James Smith (t17870711-99) and OBP, September 1780, Benjamin Kinder, (t17800913-97).

83 Mintz, “The Changing Roles of Food … ,” 265.

84 Dean, “A Slipware Dish by Samuel Malkin,” 27.

85 Withington, “Where Was the Coffee,” 74.

86 Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain, 163–4.

87 Based on digital conversation with Jaqui Pearce of Mola, 24–25th June 2020.

88 Baker, “Creamware in Context,” 31–2; Massey, “Understanding Creamware,” 25–6.

89 McCaffrey-Howarth, “Revolutionary Histories in Small Things,” 261–2 notes one set of “printed tea-cups and saucers” recorded as costing two shillings in the 1790s.

90 Egerton, Street Breakfast, 1825, Aquatint, London Metropolitan Archives, London, q8035015.

91 Jeffries, “The New Beverages – Tea and Coffee,” 272.

92 Harley, “Consumption and Poverty in the Homes … ,” 93–4.

93 Richards, Eighteenth-Century Ceramics, 155.

94 Based on digital conversation with Jacqui Pearce of Mola, 24–25th June 2020 and Pearce, “Consumption of Creamware,” 242–51.

95 Ellis, Coulton, and Mauger, Empire of Tea, 189.

96 McCaffrey-Howarth, “Revolutionary Histories in Small Things,” 261.

97 Smith, “Sensing Design and Workmanship,” 7.

98 Pennell, “For a Crack or Flaw Despis’d,” 30.

99 OBP, Law, Webb (t18230115-97).

100 OBP, February 1817, John Olsoz, (t18170219-13).

Bibliography

- Aleph. “City Scraps: Early Breakfast Stalls and Coffee Shops.” London City Press, March 5, 1864.

- Appadurai, Arjun. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Arnout, Anneleen. “Comfort and Safety: An Intersensorial History Shopping Streets in Nineteenth Century Amsterdam and Brussels.” In Shopping and the Senses, 1800–1970: A Sensory History of Retail and Consumption, edited by Serena Dyer, 79–100. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022.

- Baker, David. “Creamware in Context.” In Creamware and Pearlware Re-Examined, edited by Roger Massey, 31–42. London: English Ceramic Circle, 2007.

- Ball, Michael, and David Sunderland. An Economic History of London, 1800–1914. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Berg, Maxine. “In Pursuit of Luxury: Global History and British Consumer Goods in the Eighteenth Century.” Past & Present 182, no. 1 (February 1, 2004): 85–142.

- Berg, Maxine. Birth of the English Kitchen, 1600–1850. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2016.

- Bickham, Troy. Eating the Empire: Food and Society in Eighteenth-Century Britain. London: Reaktion Books, 2020.

- Borsay, Peter. “The English Urban Renaissance: The Development of Provincial Urban Culturec.1680–C.1760.” Social History 2, no. 5 (1977): 581–603.

- Brown, Peter B. In Praise of Hot Liquors: The Study of Chocolate, Coffee and Tea-Drinking 1600–1850: An Exhibition at Fairfax House, York 1st September to 20th November 1994. York: York Civic Trust, 1995.

- Bryant, Charles. Flora Diaetetica, or History of Esculent Plants, Both Domestic and Foreign. In Which They Are Accurately Described and Reduced to Their Linnaean Generic and Specific Names. With Their English Names Annexed … The Whole so Methodized, as to Form a Short Introduction to the Science of Botany. London: Printed For B. White, 1783.

- Carter, Louise. “Scarlet Fever: Female Enthusiasm for men in Uniform, 1780–1815.” In Britain’s Soldiers: Rethinking War and Society: 1715–1815, edited by K. Linch and M. McCormack, 155–182. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2014.

- Charles, William. Comfort or the Luxury of Charcoal, 1801, Etching. London: British Museum, 1935. 0522.7.13.

- Clarence-Smith, William. “The Global Consumption of Hot Beverages, C1500 to C1900.” In Food and Globalization: Consumption, Markets and Politics in the Modern World, edited by Nützenadel Alexander and Frank Trentmann, 37–56. Oxford: Berg, 2008.

- Clifford, Helen. “Concepts of Invention, Identity and Imitation in the London and Provincial Metal-Working Trades, 1750–1800.” Journal of Design History 12, no. 3 (1999): 241–255.

- Dean, Darron. “A Slipware Dish by Samuel Malkin: An Analysis of Vernacular Design.” In Design History Reader, edited by Rebecca Houze, 22–28. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019.

- De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

- Hot Water Urn, Silver. “The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection.” Victoria and Albert Museum, LOAN:GILBERT.674:1 to 4-2008, 1742–3.

- Egan, Pierce. Real Life in London, Vol II. London: Methuen & Co, 1905. Originally Published 1821.

- Ellis, Markman, Richard Coulton, and Matthew Mauger. Empire of Tea: The Asian Leaf That Conquered the World. London: Reaktion Books, 2017.

- Fontaine, Laurence. History of Pedlars in Europe. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

- Foucault, Michel, and Jay Miskowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986): 22–27.

- Fromer, Julie. A Necessary Luxury: Tea in Victorian England. Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2008.

- Ginzburg, Carlo, John Tedeschi, and Anne C. Tedeschi. “Microhistory: Two or Three Things That I Know About It.” Critical Inquiry 20, no. 1 (October 1993): 10–35.

- Gowrley, Freya. “Craft(ing) Narratives: Specimens, Souvenirs, and ‘Morsels’ in a La Ronde’s Specimen Table.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction 31, no. 1 (October 2018): 77–97.

- Harley, Joseph. “Consumption and Poverty in the Homes of the English Poor, C. 1670–1834.” Social History 43, no. 1 (December 19, 2017): 81–104.

- Henderson, Tony. Disorderly Women in Eighteenth-Century London: Prostitution and Control in the Metropolis, 1730–1830. Oxon: Routledge, 2013.

- Hill Radcliffe, David. “The Cockney School of Poetry.” lordbyron.org. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://lordbyron.org/contents.php?doc=JoLockh.Cockney.Contents.

- Hitchcock, Tim. Down and out in Eighteenth-Century London. London: Hambledon and London, 2004.

- Horwood, Richard. Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, the Borough of Southwark and Parts Adjoining, Shewing Every House. 1:2,500. London: R. Horwood, 1799.

- Hughes, G. “The Georgian Vogue of the Tea-Urn.” Country Life, October 1962.

- Jeffries, Nigel. “The New Beverages – Tea and Coffee.” In The Spitalfields Suburb 1539 – c 1880 Excavations at Spitalfields Market, London E1, 1991–2007, edited by Chiz Harward, Nick Holder, and Nigel Jeffries, 271–275. London: London Museum of London Archaeology, 2015.

- Jones, Peter T. A. “Redressing Reform Narratives: Victorian London’s Street Markets and the Informal Supply Lines of Urban Modernity.” The London Journal 41, no. 1 (January 2, 2016): 60–81.

- Kettilby, Mary. A Collection of Above Three Hundred Receipts in Cookery, Physick and Surgery: For the Use of All Good Wives, Tender Mothers, and Careful Nurses. London: Richard Wilkin, 1714.

- Lamb, Charles. Essays of Elia. Paris: Baudry’s European Library, 1835.

- Langbein, John. The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Lord, Beth. “Foucault’s Museum: Difference, Representation, and Genealogy.” Museum and Society 4, no. 1 (2015): 1–14.

- Massey, Roger. “Understanding Creamware.” In Creamware and Pearlware Re-Examined, edited by Roger Massey, 15–31. London: English Ceramic Circle, 2007.

- Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor. Vol. 1. London: Griffin, Bohn & Co., 1861.

- McCaffrey-Howarth, Caroline. “Revolutionary Histories in Small Things: Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette on Printed Ceramics, C.1793–1796.” In Small Things in the Eighteenth Century: The Political and Personal Value of the Miniature, edited by Beth Fowkes Tobin and Chloe Wigston Smith, 257–273. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022.

- Miller, Thomas. “The Force of Habit.” Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal, June 1848.

- Mintz, Sidney. “The Changing Roles of Food in the Study of Consumption.” In Consumption and the World of Goods, edited by John Brewer and Roy Porter, 261–273. Routledge, 2013.

- Nancy, Cox, and Karin Dannehl. “Tea – Tea Ware.” In Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities 1550–1820 (Wolverhampton, 2007), British History Online. Accessed December 7, 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/traded-goods-dictionary/1550-1820/tea-tea-ware.

- Nott, John. The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary: Or, the Accomplish’d Housewives Companion. … The Second Edition with Additions … . London: C. Rivington, 1724.

- OBP. October 1740, Mary Harwood (t17401015-65).

- OBP. June 1752, Elizabeth Selwood, Mary M'Daniel, Martha Atkins, (t17530607-33).

- OBP. January 1757, Elizabeth Knotmill, (t17570114-17).

- OBP. September 1768, William Dixon (t17680907-29).

- OBP. May 1777, John Gibson, (t17770514-29).

- OBP. September 1778, Joseph Ruff, (t17780916-13).

- OBP. July 1783, William William Law, (t17830723-122).

- OBP. May 1784, Ann Powis, (t17840526-34).

- OBP. May 1784, Joseph Levy, (t17840526-43).

- OBP. September 1784, Henry Morgan, (t17840915-1).

- OBP. June 1785, Thomas Hanvy, (t17850629-114).

- OBP. September 1785, John Berrow (t17850914-179).

- OBP. January 1823, Edmund Law, Thomas Webb (t18230115-97).

- OBP. September 1790, Joseph Pocock, Sarah Watson (t17900915-34).

- OBP. February 1792, John Lewis, Robert Pearce, (t17920215-7).

- OBP. May 1795, Joseph Samuel, (t17950520-42).

- OBP. December 1802, David Milton, John Cossey, (t18021201-98).

- OBP. July 1803, William Graystone, (t18030706-70).

- OBP. September 1804, George Freak, John Richardson (t18040912-56).

- OBP. May 1805, John Rose (t18050529-41).

- OBP. April 1807, Mary Berry, (t18070408-93).

- OBP. January 1808, Charlotee Brown, Elizabeth Hincks (t18080113-58).

- OBP. May 1809, William Jones, Moses Fonseca (t18090517-17).

- OBP. June 1810, Elizabeth Durant, Mary Kite, Elizabeth Ellis (t18100606-70).

- OBP. January 1823, Edmund Law, Thomas Webb (t18230115-97).

- OBP. September 1780, Benjamin Kinder, (t17800913-97).

- OBP. Feburary 1817, John Olsoz, (t18170219-13).

- OBP. July 1787, James Smith (t17870711-99).

- Ogborn, Miles. Spaces of Modernity: London’s Geographies, 1680–1780. New York: Guilford Press, Cop, 1998.

- Otter, Chris. The Victorian Eye: A Political History of Light and Vision in Britain, 1800–1910. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- Peachi, John. Some Observations Made upon the Root Called Serapias or Salep, Imported from Turkey. Shewing … . London, n.d, 1694.

- Pearce, Jacqueline. “Consumption of Creamware – London Archaeological Evidence.” In Creamware and Pearlware Re-Examined, edited by Roger Massey, 231–253. London: English Ceramic Circle, 2007.

- Penell, Sara. “‘For a Crack or Flaw Despis’d’: Thinking About Ceramic Durability and the ‘Everyday’ in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England.” In Everyday Objects: Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture and Its Meanings, edited by Tara Hamling and Catherine Richardson, 27–40. Farnham: Ashgate, 2010.

- Pennell, Sara. “‘Great Quantities of Gooseberry Pye and Baked Clod of Beef’: Victualling and the Experience of ‘Eating Out’ in Early Modern London.” In Londinopolis: Essays in the Cultural and Social History of Early Modern London, edited by Paul Griffiths Griffiths and Mark Jenner, 228–249. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

- Porter, Roy. London: A Social History. London: Penguin Books, 2000.

- Pyne, William Henry. Pynes’s British Costumes: An Illustrated Survey of Early Eighteenth-Century Dress in the British Isles. Facsimile by Ware: Wordsworth Editions, 1989. (Originally Published 1805).

- Retford, Kate. “From the Interior to Interiority: The Conversation Piece in Georgian England.” Journal of Design History 20, no. 4 (January 1, 2007): 291–307.

- R Hughes Thomas. Treaties, Agreements, and Engagements, between the Honorable East India Company and the Native Princes, Chiefs, and States, in Western India, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, & C … ; Printed for the Government at the Bombay Education Society’s Press, 1851.

- Richards, Sarah. Eighteenth-Century Ceramics: Products for a Civilised Society. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

- Rocque, John. A Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster, and Borough of Southwark; with the Contiguous Buildings. London: John Pine and John Tinney, The British Library, 1746.

- Schatzki, Ted. “Timespace and the Organization of Social Life.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life: Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by Elizabeth Shove Shove, Frank Trentmann, and Richard Wilk, 35–48. Oxford: Berg, 2009.

- Schwarz, L. D. London in the Age of Industrialisation: Entrepreneurs, Labour Force, and Living Conditions, 1700–1850. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Smith, Eliza. The Compleat Housewife, Or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion. London: J. and J. Pemberton, 1739.

- Smith, Kate. “Sensing Design and Workmanship: The Haptic Skills of Shoppers in Eighteenth-Century London.” Journal of Design History 25, no. 1 (January 17, 2012): 1–10.

- Smith, John Thomas. The Cries of London: Exhibiting Several of the Itinerant Traders of Antient and Modern Times: Copied from Rare Engravings or Drawn from the Life. London: John Bowyer Nichols and Son, 1839.

- Stobart, Jon. “Leisure and Shopping in the Small Towns of Georgian England.” Journal of Urban History 31, no. 4 (May 2005): 479–503.

- Styles, John. “Involuntary Consumers? Servants and Their Clothes in Eighteenth-Century England.” Textile History 33, no. 1 (May 2002): 9–21.

- Styles, John. “Lodging at the Old Bailey: Lodgings and Their Furnishing in Eighteenth-Century London.” In Gender, Taste and Material Culture in Britain and North America, 1700–1830, 66–80. London: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Taverner, Charles Robert. “Selling Food in the Streets of London, c. 1600–1750.” PhD Thesis, Birkbeck 2020.

- Taverner, Charlie. Street Food: Hawkers and the History of London. Oxford: Oxford University Press, n.d.

- “The Humbler Employments of London.” Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal, no. 183 (August 1, 1835): 212–213.

- “The Works of God Displayed (1817).” Methodist Magazine Jan.1, 1798–Dec.1821 Vol. 40. London, n.d.

- Thirsk, Joan. Food in Early Modern England: Phases, Fads, Fashions, 1500–1760. London: Continuum, 2009.

- Tierney, Elaine. “‘Dirty Rotten Sheds’: Exploring the Ephemeral City in Early Modern London.” Eighteenth-Century Studies 50, no. 2 (2017): 231–252.

- Trentmann, Frank. Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers, from the Fifteenth Century to the Twenty-First. London: Penguin Books, 2017.

- Tullett, William. Smell in Eighteenth-Century England: A Social Sense. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Voth, Hans-Joachim. “Time and Work in Eighteenth-Century London, Discussion Papers.” Economic and Social History, no. 21 (December 1997): 1–33.

- Wadham, James. “Tea Fountain or Tea Pot.” English Patents of Inventions, Specifications: 1774, 842–900, Volumes 1001-1110 (H.M. Stationery Office, 1856), no.1076.

- Withington, Phil. “Where Was the Coffee in Early Modern England?” The Journal of Modern History 92, no. 1 (March 2020): 40–75.

- Wolfgang, Schivelbusch. Disenchanted Night. Oxford: Berg, 1988.

- Yonan, Michael Elia, and Alden Cavanagh. “Introduction.” In The Cultural Aesthetics of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain, edited by Cavanagh Alden, 1–19. New York: Routledge, 2016.

- Yonan, Michael. “Toward a Fusion of Art History and Material Culture Studies.” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 18, no. 2 (n.d.): 232–248.

- Z. “The Cockney School of Poetry.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magzine 18, no. 103 (October 1825): 155–160.