Abstract

In recent years, both within and beyond academic and clinical spheres, medical and health humanities have become increasingly influential. Drawing from interdisciplinary fields in the humanities, social sciences, and the arts, medical and health humanities present unique lenses for considering nuanced spaces and lived experiences of health and health care; they also help challenge traditional ways that medicine and health care are understood and practiced. This collection brings together practitioners and theorists working broadly in medical health humanities, asking them both to consider their work as temporally and spatially located and to position their practices in conversation with a growing uptake of humanities methods and methodologies in other disciplines. The work of nine contributors uses these themes as a starting point for thinking about the future of medical health humanities in new and potentially even more productive ways.

近年来,医疗与健康人文学科在学术与临床领域之中与之外已渐具影响力。运用人文学科、社会科学与艺术之跨领域田野,医疗与健康人文学科呈现出考量健康与健康照护的细緻空间和生活经验的特殊视角;它们同时有助于挑战医疗与健康照护被理解和实践的传统方式。此一合集汇集致力于广泛的医疗健康人文的从业者与理论家,同时要求他们将其工作视为处于时空之中,并使其实践与其领域中逐渐使用的人文学方法与方法论产生对话。九位贡献者的作品,运用这些主题,作为以崭新且潜在更具创造性的方法思考医疗健康人文学科的未来之起点。

Recientemente, tanto dentro como fuera de la academia y en las esferas clínicas, las humanidades médicas y de la salud se han hecho cada vez más influyentes. Apoyándose en los campos interdisciplinarios de las humanidades, las ciencias sociales y las artes, las humanidades médicas y de la salud presentan lentes únicos para considerar los espacios difuminados y las experiencias de la salud y cuidados asociados; aquellos ayudan también a retar las maneras tradicionales como se entienden y practican la medicina y el cuidado de la salud. Esta colección junta a practicantes y teóricos que en términos generales trabajan en las humanidades médicas y de la salud, pidiéndoles considerar su trabajo como localizado temporal y espacialmente, y posicionar sus prácticas en conversación con la creciente disponibilidad de métodos de las humanidades y metodologías de otras disciplinas. El trabajo de nueve colaboradores usa estos temas como punto de partida para pensar acerca del futuro de las humanidades médicas y de la salud, con nuevas y potencialmente más productivas maneras.

AN INTRODUCTION TO GEOGRAPHIES OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH HUMANITIES: A CROSS-DISCIPLINARY CONVERSATION

Sarah de Leeuw, University of Northern British Columbia and University of British Columbia

Courtney Donovan, San Francisco State University

Nicole Schafenacker, University of Northern British Columbia

A (re)turn to humanities is informing disciplines as diverse as medicine, engineering, geology, public health, and—as GeoHumanities makes clear—geography (Greaves and Evans Citation2000; Fisher and Mahajan Citation2010; Hynes and Swenson Citation2013; Cresswell et al. Citation2015; Dear Citation2015). In this (re)turning to humanities by medicine and health science disciplines, medical health humanities has positioned itself as an area of inquiry with compelling methodological and conceptual approaches. Medical and health sciences share a series of commonalities but are not entirely interchangeable. Both, broadly conceived, are focused on human wellness throughout the life cycle across different times and spaces. Although, as this article explores, the two sciences are changing, they are (at least in the last century) fundamentally rooted in biological and biochemical sciences, often privileging quantitative evidence and reproducible or positivistic empirical knowledge. Medicine is a discrete discipline, with a number of specialty subdisciplines, principally focused on training physicians and emphasizing disease treatment and care. The health sciences, however, are a broad collection of disciplinary efforts, ranging from public health that focuses on disease prevention and health promotion to social determinants of health focusing on a wide range of factors such as gender and economic status that influence well-being (or a lack thereof). We are sensitive to these differences but, in this article, are interested in how both are (re)turning to the humanities—albeit somewhat differently but also with overlaps. Medical sciences, often in the training of clinical practitioners, are increasingly turning to the humanities in efforts to increase empathy of physicians toward patients and to the complex affective experience of illness, including experiences beyond a singular patient. Health sciences, in forms like public health, epidemiology, or social determinants of health studies, are taking note of humanities methodologies and analytic frameworks to add criticality or even semiotic and discursive understandings to health research. Medical health humanities, then, aims to capture and, in practice, account for the intensities of personal (often marginalized) experiences in health care systems: They seek to activate and account for creative and innovative engagements with place that open new (often interdisciplinary) ways of seeing and being in worlds that involve human health and illness (Allen, Citation2016; Jones et al. Citation2017). Indeed, with a privileging of narrative, affect, visual literacy, history, and affective geographic attunement, the medical health humanities are being touted, including by medical clinicians and health researchers and educators, as a novel way of “understanding cultural and historical contexts of medicine and health … [that offer] a deeper, more complex understanding of the human experience … and of the social and cultural challenges related to them” (Bowman Citation2015, 75).

This themed set builds on and extends existing work recognizing the role of geography and other humanities-informed disciplines in and on medicine and health sciences. Although new synergies and provocations are seeing a resurgence manifest for contemporary times and spaces, configurations of health, medicine, geography, and humanities are not entirely new. Although health and medical geographies, as subdisciplines, have focused on different spaces, places, and subjects in unique ways (medical geography more focused on macroscales of epidemiological modeling, analysis of spatial patterns of disease and the spatiality of health care provision; health geography more focused on sociocultural and microscale spatial aspects of care and well-being), the two have shared methodological and epistemological terrains that align with humanities interests, including attention to therapeutic landscapes, the nexus of health and place, and how those nexus and intersections are felt, humanized, and experienced (Gesler Citation1992; Rosenberg Citation1998; Parr Citation2011). Geographic work in these overlapping areas expressly asserts and documents the powerful therapeutic (or deleterious) nature of space and place on well-being; it evidences embodiment and emotion as intertwined with landscape or physical environment; it substantiates social and cultural geographies, alongside ecologies, as fundamental to medical and health care practices and to human well-being or lack thereof (Cameron Citation2012; Donovan Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Madge Citation2014; Atkinson Citation2016; De Leeuw et al. Citation2017). With this in mind, this themed set brings together clinical practitioners, artists, and scholars in humanities and geography (which, as outlined, we understand as overlapping and not mutually exclusive) to reflect on space and place as powerful organizational and affective forces both within medical and health environments and that might enliven and enrichen understandings of providing and receiving care. The nine pieces curated herein cut across diverse disciplines and areas of research, covering a wide range of issues and demonstrating the broad conceptual and rhetorical possibilities within medical-health humanities scholarship and practice. At the heart of these works is a range of creative and narrative possibilities that reframe understandings about what constitutes health and disease, health care, and by extension, health experiences and the spaces and places in which these unfold (Charon Citation2006b; Egnew Citation2009; Galvin and Todres Citation2012). To address these questions of geography in medical health humanities, the authors explore and engage with diverse places, spaces, and scales, dispelling the notions that health experiences and disease prevention take place within, or can be understood in relation to, distinct or easily bounded geographies. The geography–health nexus is not limited, however, to more of these topographic considerations. Looking at spatial and discursive considerations of cells and pathogens or considering the agency of nonsentient objects for people living with different cognitive attunements extends medical-health humanities into more-than-human geographies; reflecting on stories and narratives or thinking about feelings of patients in clinical waiting rooms extends medical health humanities into registers of emotional geographies and geographies of affect. With the arts and the humanities as the basis for interrogating questions that relate to health and medicine, the pieces in this themed set take us beyond traditional sites of care: The first works in this curation address, broadly, the methodological and theoretical terrains of medical health humanities, and the remaining pieces demonstrate the geographies of medical and health humanities in practice. Each of the contributions constitutes expressly spatialized work that pushes against more standardized dis/un/placed or space-neutralized biomedical understandings of health, illness, and human well-being (including where each of those are constituted). The offerings in this curation are making fundamental epistemological claims about re-envisioning, rethinking, and practicing anew both, on the one hand, health and medical sciences and, on the other hand, health and medical geographies: Contributions to this themed set, read in dialogue with each other or as individual entries, offer new ways to engage and enliven the spatiality and humanity of illness and health.

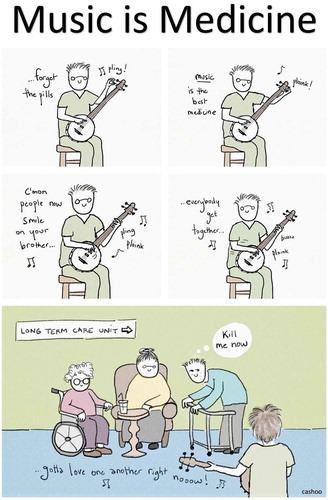

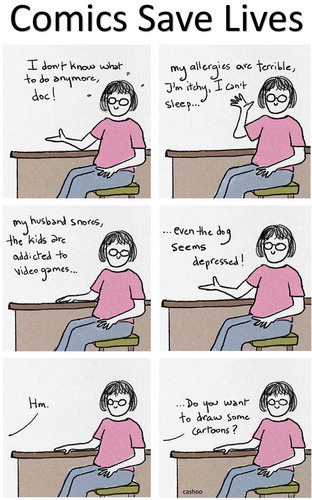

Too often, on opening pages of a standard issue medical textbook, medical and health students are presented explanations about, to use but one of many possible examples—and referencing in part Squier’s article—the immune system. A critical (and deeply complex) regulator of disease processes and outcomes, the immune system is mostly taught to future health care professionals as a decontextualized microscopic biosystem, which students are instructed to define and identify mostly as contained structures and functions that sometimes go askew and require diagnosis and intervention. None of this information is spatialized beyond the confines of a disembodied gut. In her article “At the Membranes of Care,” Charon offered an apt image of a membrane as meeting point between two ways of seeing: “There may be a parallel to be found between the ‘membrane’ between two persons talking … and the cellular membrane, of which we know so much” (Charon Citation2012). The purely clinical view of health and disease, in other words, unfolds within discursive and relational spaces of academic and professional medicine, spaces that often represses a range of other modalities and ways of understanding the world: The stories and voices that speak to the embodied challenges of disease, the medical processes and experiences that offer insight to a life lived (Forney Citation2012; Rousso Citation2013; Stecopoulos Citation2016: see also Frank, this issue). Cell walls and microbes inevitably meet the instabilities of embodiment, uncertainty, and exhaustion, producing complex personal histories that span a range of places, spaces, and scales. With increasing frequency, these omissions have entered personal memoirs, comics, blog posts, and academic literature—many of which are mediums of expression taken up by contributors to this themed set.

Identifying the limits of formal medical training and practice, more and more clinicians and medical researchers similarly recognize the relevance of subjectivity and experience, and for the need to radically recast understandings of mental health, end of life care, and chronic disease (Begley et al. Citation2014; Cowen, Kaufman, and Schoenherr Citation2016). Despite this, there remains the lingering question of how best to capture and represent individual or marginalized experiences or perspectives of health and disease (Riessman Citation2008). The emergence of humanistic medicine in the 1990s offered a starting point for considering the shortcomings of biomedicine and medical education, steeped in the traditions of positivism (Rabow et al. Citation2016). Humanistic medicine helped to illuminate a number of concerns and issues obscuring the patient waiting in the examination room (Plant et al. Citation2015). When pausing to listen, clinicians were reminded again and again that clinical methodologies, which present specific norms of engagement, were closing off voices and perspectives (Kleinman Citation1988; Charon Citation2006b). These voices offered a clear reminder that patients could not be reduced to data points and highlighted the problematics of adhering closely to clinical necessity (DasGupta Citation2008; Galvin and Todres Citation2012). The dialectic between biomedical facts and subjective experience reveals a world of overlooked issues and questions: Health and disease create uncertainty; diagnoses and experiences encompass disparate geographies, crossing scales, blurring the boundaries between places, spaces, and time (Charon Citation2006a; Egnew Citation2009; Galvin and Todres Citation2012; Viney, Callard, and Woods Citation2015). Positivist approaches cannot contain the fluidity of medical realities that speak to the general messiness of everyday life and an illness experience (Frank Citation2001; DasGupta Citation2008; Shapiro Citation2011).

Using diverse approaches, the authors in this themed set also all seek to show processes that ease or constrain the choices of those affected by health and disease. In doing so, the authors help to personalize questions pertaining to broader issues of health and health care. At the same time, the authors enable an imagining of new possibilities, reproducing personal narratives that can be obscured, minimized, or even forgotten with time or within dominant spaces. In what ways do these personal accounts enable thinking about broader systems of care, about touching the lives of many and encompassing public and private spaces? How do creative frameworks unmask significant moments of care, which could be dismissed as inconsequential? With growing frequency, the work within medical health humanities helps to identify that medicine, health, and disease are all categories that give rise to a range of experiences and associations: The medical and health humanities have this in common with geohumanities (Kumagi and Naidu Citation2015). Medical and health humanities likewise demonstrate the ways in which geography is a significant variable, informing a range of contexts and demonstrating the linkages between apparently incommensurable scales such as the microbe and the state (Sobo and Loustaunau Citation2010).

The works in this themed set also test what constitutes valid evidence. In the context of biomedicine, health is tracked precisely: The goal is too often pinpointing specific factors that lead to disease emergence so that the disease can be contained or can be cured (Charon Citation2006a). When the boundaries of health and medicine are reframed to include temporality, intersubjectivity, affect, community, or embodiment, biomedical questions fail to provide a sufficient answer. Once narratives and creative works are included in how health and medicine are named, the idea of truth is upended; closure and containment are less possible (Charon Citation2006b; Charon and Wyer Citation2008; Shapiro Citation2011). The insertion of alternative perspectives and voices is significant, providing much thicker and richer explanations of otherwise discrete categories offered in more standardized medical modalities. More fundamentally, welcoming and validating the worth of alternative forms of knowledge provides a starting point for recognizing the experiences and perspectives of vulnerable individuals and marginalized groups (Viney, Callard, and Woods Citation2015).

The importance of humanities and arts-based approaches is not limited to the practice of medicine or provision of care. Creative and less conventional approaches that convey health and medical issues demonstrate the limits of traditional methods, even in the context of qualitative research and traditional modes of pedagogy (Viney, Callard, and Woods Citation2015). Not unlike the goal of clinical inquires, qualitative methods, including interviews, usually aim to answer a specific question through interweaving firsthand accounts with other forms of evidence. Yet, existing approaches are often limited, and not suited to capture a fleeting emotional experience, the unknowable, or a biological event that happens in the blink of an eye or is saturated with emotion beyond words (Charon Citation2006b; DasGupta Citation2008). Traditional modes of research and pedagogy might not equip students or readers with adequate tools to situate themselves in the physiological, emotional, and embodied experience of someone from another time and place: Again, activating the humanities in both geography and medical health sciences is one effort in tackling these deficiencies (De Leeuw and Hawkins Citation2017; De Leeuw et al. Citation2017).

Traditional methods of both clinical and social science inquiry seek to neatly categorize and contain health and medical issues. Approaches used in the field of medical health humanities reject notions that what constitutes health and medicine has clear geographic or temporal boundaries (Shapiro Citation2011). Formal explanations of health and disease might attempt to locate disease experiences within the confines of conventional spaces and places. More complex and creative understandings of health experiences (both personal and sociocultural) identify that health experiences unfurl and fold back, encompassing and linking together disparate geographies, positionalities, and subjectivities (Berg Citation2015). Similarly, intimate health experiences are not delimited by traditional explanations of time. As a series of interconnected events, health and disease experiences are never stable. Following the diagnosis of an illness, subjectivities, bodies, and cells are constantly changing, suggesting a process of continual becomings and unraveling (Donovan and Ustundag Citation2017). Fluidity and change suggest multiple aesthetic, creative, and conceptual possibilities to represent health and medical processes.

This themed set extends conversations about the possibilities in medical health humanities. The goal is illustrating how diverse geographies shape and thread through health and medical processes. Some contributions begin to position health and medicine in the context of more institutional medical and health geographies: the space of the clinic waiting room; within the disease landscape of rural Tennessee; on the grounds of a nineteenth-century mental asylum (Kearns and Neuwelt; Frank; McGeachan and Parr). All of the essays demonstrate that health and medical processes cannot be catalogued through expected geographic and temporal forms: Waiting rooms and the process of waiting challenge how we traditionally measure the passage of time; institutional discourses of disease position humans at the center, forgetting the critical role of microscopic pathogens in disease narratives; the nuances of mental health are not adequately represented in conventional discourses that overlook how spatiality and embodied practices are at the heart of everyday experiences; personal narratives of disease are inseparable from questions of technology and ethics; and the physical remains of former sites of care (Kearns and Nuewelt; Squier; Beljaars; Coyle and Atkinson; El-Hadi; Shooner; Shklanka; McGeachan and Parr).

The contributions in this themed set offer compelling additions to a conversation we initiated several years ago in a series of panels on geomedical humanities in San Francisco. The essays, poems, visual expressions, and other works suggest many other creative possibilities for presenting a constellation of diverse medical and health narratives and perspectives. We are mindful of many other directions in which future work in geomedical humanities might go. We envision work that identifies and mobilizes politics and the social justice possibilities of geomedical humanities work, more firsthand explorations, a range of theoretical assessments, and opportunities to consider other media and forms of creative expression, including music, video, and emerging digital technologies. We hope this themed set contributes to growing and enlivened exchanges about intersections of geography, humanities, and medical health sciences disciplines.

WHAT IF A WAITING ROOM INVITED US?

Robin Kearns and Pat Neuwelt, University of Auckland

“The doctor will be with you shortly, please take a seat.” Where can I take the seat to? Nowhere outside of this room. I am confined by the four walls and the knowledge that being here is a prerequisite to being seen by the doctor … and, until that time, I am being seen by others—patients, receptionists … people I wouldn’t otherwise choose to spend time with … waiting … in a room, the waiting room.

—R. Kearns, personal journal

The waiting room is an underexamined location in the health care system. For one set of occupants—receptionists—it is a workplace where multiple tasks including greeting arrivals, booking appointments, managing patient queries, and receiving payments are performed. For others—patients—it is a space of pause on the journey to a consultation in which experiences can range from conviviality to anxiety and exasperation (Neuwelt, Kearns, and Browne Citation2015; Neuwelt, Kearns, and Cairns Citation2016).

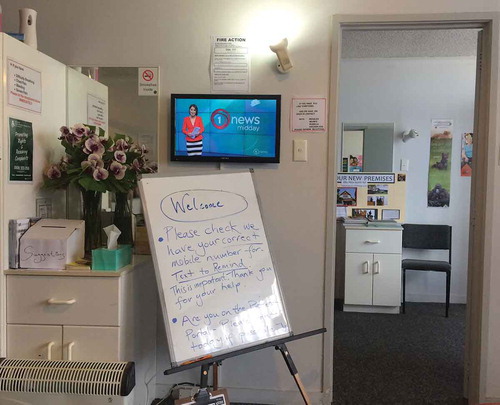

Waiting is the performance self-evidently central to the design and occupation of health care waiting rooms. Most literally, the Oxford English Dictionary tells us that waiting is “the action of remaining stationary or quiescent in expectation of something” (Oxford Dictionaries Citation2017). Expectation is central to the waiting room experience, for there is generally no other reason to be there in the absence of expecting to see a doctor or nurse. It is a container space, ostensibly awaiting patients. Yet, as Bissell (Citation2007) argued, with unintended applicability to the clinical reception context, “the event of waiting is [not] a dead period of stasis … but is instead alive with the potential of being other than this” (278). Could, then, a waiting room invite rather than contain us (see )?

FIGURE 1 The waiting room: Space of containment. Photo by Robin Kearns. (Color figure available online.)

What does it mean to wait? The act of waiting itself allows such questions to arise. Waiting slows us down and brings us to a mooring (Hannam, Sheller, and Urry Citation2006), ties us to a place. There is no complete stillness in this embodied space, though; we shift in our seat, startle in anticipation when a doctor appears to call out a name, feel one’s heartbeat speeding up as anticipation continues. Despite a delusion of comfort, the body moves on through the time of sitting still (Bissell Citation2008; see ).

FIGURE 2 The waiting room: Temporal expansiveness. Photo by Robin Kearns. (Color figure available online.)

The waiting room offers a first impression of what lies beyond and generates a wealth of meanings (Gasparini Citation1995; Arneill and Devlin Citation2002). As a space of transition, waiting rooms lie between the public space outside the site of health care and the private interior site of clinical consultation. They are liminal spaces of betweenness (Entrikin Citation1991), places on the way to somewhere else, in which embodied identities experience pause in the passage from the everyday world to the clinical encounter.

Waiting is a period of punctuated time—a hyphenated and emplaced symbol of the time of transition from person to patient. They sculpt the identity of the “person-patient” through the experience of rooms (hallway, presentation at reception desk, then the waiting room) and moments (entry, greetings, identification of self, being seated, waiting …).

As the clock strays beyond the agreed appointment time, moments hang heavy and time is reframed as a delay. Paradoxically, perhaps, just as the place of waiting is constrained and confined, time can seem unbounded and stretch out into the uncertainty of when we will “be seen.” Waiting is also a process of becoming: not only the transformation into the patient role, but also into the state of being restless, bored, or anxious. Despite the presence of distractions such as artwork, possibilities of waiting being an opportunity for relaxation are often countered by the ever-present expectation of being called for one’s clinical consultation. The waiting room is the arena in which expectation is generated. To wait is to anticipate the future.

The interpenetration of place and time unfolds within the waiting room itself as the experience potentially moves from expectation to entrapment and frustration. Such spaces can be replete with ambivalence: A clock can connect those present to a sense that there is progress and yet a clock can also be a stark reminder of the passage, if not wastage, of time. In some waiting rooms, the clock has been intentionally removed, for it can be a source of anxiety, detracting from efforts to find comfort in the seating (Neuwelt, Kearns, and Browne Citation2015; see ).

FIGURE 3 The waiting room: Mooring on the journey to care. Photo by Robin Kearns. (Color figure available online.)

These rooms, and the moments spent within them, are great levelers; there is no business class at the general practitioner’s surgery. Everyone is there. They generate times of not knowing what’s next: not knowing when one will be summoned, what will happen behind the closed door of the consultation room, and how long it will be until one’s name is called, not knowing if one’s name will be heard within the din of phone calls and conversation. Waiting for the doctor can be like Waiting for Godot—an encounter that seems to never eventuate.

Constructions of time in Western countries involve notions of efficiency, speed, and instant gratification (Griffiths Citation1999). Time is subjected to intense planning and dissected into urgent metrics. Privatized health care is obsessed with annihilating waiting by efficiency. In the competitive U.S. health care market, real-time billboards announce to passers-by how few minutes of waiting will be required if they are the chosen point of health care (see ).

FIGURE 4 Speed as selling point: Englewood, Florida. Photo by Robin Kearns. (Color figure available online.)

Creativity and responsiveness are possible. Hollenberg and Bourgeault (2009, 197) described a clinic that includes a welcoming space called the “living room” where patients wait. It has couches and chairs and a library of donated books. It is where “patients, practitioners, family members and other parts of the community formally and informally interact and socialise” (Hollenberg and Bourgeault Citation2009, 197). An inviting design makes good sense, for there is evidence from controlled trials that the stressful nature of going into hospitals can be mitigated by improved design of waiting spaces (Leather, Beale, and Santos Citation2003). Architectural design has also been shown to influence the culture of health care practice (Gillespie Citation2002).

At South Seas, a primary care clinic in Otara, a predominantly Polynesian suburb of Auckland (Friesen and Kearns Citation2010), creativity and responsiveness is manifestly evident. Key features include staff involvement in choices, colors, and materials; custom-designed furniture, responsive to a range of body shapes and sizes; internal posts resembling those in a Samoan fale made by community-based artists; and culturally significant floor and wall patterning based on traditional tattoo design (see ).

FIGURE 5 Reception desk design, South Seas Health Care, Otara (Auckland, New Zealand). Courtesy South Seas Healthcare. (Color figure available online.)

At South Seas, perhaps most significantly for patients’ emotional comfort, the reception area includes a side desk facing away from where patients check in, where financial transactions can occur. Overall, according to its architect, there was “a conscious response to Polynesiality and we were clear in understanding the need to greet clients and deal with private issues so included an area at one side where they could take people to discuss medical and financial issues. That was on the table from the start” (C. Sage, Design TRIBE, conversation, March 24, 2017; see ).

FIGURE 6 Waiting room design, South Seas Health Care, Otara (Auckland, New Zealand). Courtesy South Seas Healthcare. (Color figure available online.)

To be a patient requires patience, for we invariably spend more time in the waiting area than the consultation room. Times and spaces of waiting—especially in health—have been seen with emotionally colorless eyes and carefully contained pauses on a journey to care. Yet, such rooms and the often-protracted moments they produce, have potential to affirm our humanity (Vanier Citation1998) or, as Gasparini (Citation1995) suggested, “give rise to the experience of surprise” (41). To be surprised is to be invited into conversation, creative distraction, culturally affirming design, varied seating, or spaces in which to retreat from the gaze of others. All this is possible. We have waited too long.

THE INVISIBLE WAR: SCALING AS ENGAGED ANALYSIS

Susan Merrill Squier, Pennsylvania State University

A work of graphic medicine, The Invisible War: A Tale on Two Scales, deploys the geographic concept of scale—“[t]he spatial, temporal, quantitative, or analytical dimensions used to measure and study any phenomenon” (Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn Citation2000, 218)—to redraw the boundaries of war and medicine (Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn 2000, 218; Barr et al. Citation2015). This black-and-white comic toggles between two settings and two groups of actors to shift our conception of warfare away from its human-centered focus and to reposition medicine as a practice whose responsibility extends to, and links, both the microbial and geopolitical realms. Setting I is a casualty clearing station on the Western Front during World War I, where Australian nurse Annie Barnaby is treating a soldier suffering from bacterial dysentery, only to become infected with the devastating disease herself. Setting II is Sister Barnaby’s own gut, to which the shigella flexneri bacteria decamp from the dying soldier. There, they multiply wildly until checked by a particularly adaptive mutant phage virus. Through visual and verbal strategies the comic portrays the connections between microbial and political ecologies, and demonstrates how bacteria, viruses, and insects, and whole armies as well as individual soldiers and nurses, are all significant actors at their different scales.

Although the concept of scale is usually thought of as telescoping between the microscopically small and the spatially extensive, a close look at The Invisible War reveals that there exists a humanities-based register of scale that can be used to intensify the exploration of a biomedical issue in ways of interest to the geohumanities. Social scientists draw on scale to identify, observe, and explain significant patterns and problems; to move propositions from one level of generalization to another; and for the “optimization of some process or function” (Gibson, Ostrom, and Ahn 2000, 218). In addition to the natural and social-science-based uses of scale, this comic incorporates a mode of scale anchored in humanities discourses. The incorporation of poetry, photography, and (social, military, scientific, and cultural) history, as well as rhetorically significant scaled contrasts in verbal registers, provide additional representational and analytic dimensions to this tale of wartime medicine. This humanities-based use of scale demonstrates that institutions of war and medicine are not “scalebound,” that is possessed of only a few, distinct, and stable scalar attributes, but are rather “scaling objects,” possessed of a shifting and nearly infinite set of perspectives and scales (Mandelbrot Citation1981, 45). Mandelbrot’s formulation seems to anticipate the fly that serves as the vector for the shigella infection in The Invisible War: “For practical purposes, a scaling object does not have a scale that characterizes it. Its scales vary also depending upon the viewing points of beholders. The same scaling object may be considered as being of a human’s dimension or of a fly’s dimension.” (Mandelbrot [Citation1981)] 2007, 45)

The pages that follow demonstrate several examples of scaling, ranging from the natural through the social sciences to the humanities. I present them, and then reflect on their implications.

In , we see the shigella bacteria moving through the small intestine and past the bile duct. Juxtaposed to the cross-sections and inset close-up images of the bacteria, we see a level panorama of the foot soldiers marching along the banks of the Somme, as the nurses load the wounded, on stretchers, into the barges. In , we see an aerial view of those barges, as they start downriver to the stationary hospital. In addition to those geographic and biological scale shifts, a humanities-based concept of scaling links and contrasts the bacteria and the barge through the contrast between their respective rhetorical registers. The shigella bacteria make enthusiastic and juvenile exclamations as they speed through the intestine: “Wheeee!” and “Woah! How FAST can we go!”—as the barges, containing their load of wounded soldiers, move off, “Budging the sluggard ripples of the Somme.” The appendix reveals this line to be an intertextual allusion to Wilfred Owen’s “The Hospital Barge.”

The top tier of intensifies the sites of scaling. The text box locates us in Annie’s gut, which “is being reduced to an exploding wasteland,” while its visual imagery references the exploding wasteland of military trench warfare, referenced several pages earlier (Barr et al. Citation2015). The shigella bacteria have by now been individuated by names and speaking styles, and a new group of actors, the phages, acquire their own signature rhetorical style: collective rhyming utterances.

might seem to center on the image of nurse Annie, fighting for her life in the hospital bed as a nurse prays by her side, but in fact the focus of the image is on the battle between the shigella flexneri bacteria and the mutant phages that are destroying them. In a viral call-and-response poetry, they announce their military mission: “We hunt in/the home/protecting/our own.” “You infect/we protect.” The destabilizing effect of this scaling is visualized on , in a Latour litany that moves us from 1,500 km to 70 pm, taking with us a landscape, landscape features, people, buildings, items of food, insects, DNA, and gases.

I have been suggesting that we need to incorporate attention to the humanities-based concept of scale if we are to fully grasp the power of this work of graphic medicine. Let me close with one word of caution, and one of celebration.

First, the caution: Let me draw attention to a representational problem that the verbal rendition of scale inadvertently produces in The Invisible War. Comics are a combination of text and image in deliberate sequence: Here, the text of the comic implicitly seems to rely on what a psychologist might call developmental scaling. The phage virus speaks in childlike rhymes suggesting a children’s book, whereas the shigella bacteria talk in a more adolescent, video-game jargon, and the human beings speak recognizable adult prose or register the enhanced speech of poetry. By this developmental and rhetorical scaling, the comic seems to suggest that experience at the bacterial or microbiological level is trivial in contrast to the human level. Yet from its epigraph, celebrating the concept of symbiosis, to its parallel cartographies of interior and exterior space, the comic instead affirms, equally and at all scales, the victory of symbiosis over conflict. As the commentary beneath the epigraph asserts, “Through a range of symbioses (some brief, some lifelong), microbes have collaborated with all types of life on Earth to create new, emergent forms, including human beings. While some symbioses cause harm, most bring benefits to all involved” (Barr et al. Citation2015).

Now, the celebration. Instead of echoing so much recent work on the Anthropocene era, which has, argued Castree (Citation2014), oscillated between the response of the “inventor-discloser” and that of the “deconstructor-critic,” this comic offers an exciting new model: a humanities-based intervention focused on concern rather than critique. The comic, product of a collaborative effort by “engaged-analyst[s],” bravely moves beyond the silos of academic, artistic, and scientific disciplinarity, inviting a broad range of readers and users (Castree Citation2014, 243). As we finish the comic, and turn to the back cover, we find this agential aspiration made wonderfully manifest in the placement of endorsements. Blurbs by science writers Dorian [sic.] Sagan (“A candidate for the first truly modern, 21st century graphic novel”), David Suzuki (“What a great way to learn some pretty extensive science”), and journalist Ian Warden (a “touching, harrowing story … rivetingly interesting”) give central place to the endorsement of Harry, “year 9 student,” who pronounces this book “a brilliant example of what the human mind can produce.” The note facing the Appendix emphasizes the process-based agenda of this comic as a scaling object by beckoning readers to an almost limitless arena of additional analytic and informative perspectives: “Continue reading to learn more about the science and the history behind the story. And visit www.theinvisiblewar.com.au to download teaching resources, download a digital version of The Invisible War, and more” (Barr et al. Citation2015).

“ASYLUM WEEK” AS A PEDAGOGICAL EXPERIMENT IN GEOHUMANITIES

Cheryl McGeachan and Hester Parr, University of Glasgow

This article approaches Gartnavel Royal Hospital in Glasgow, Scotland, as both ruined asylum and new-build mental health treatment facility, and as a site of pedagogy via foot, archival record, and film. Relating the intentions and experiences of Asylum Week as part of a senior honors degree course in Glasgow University, we wish to animate the mental health asylum as a contemporary space of learning and geohumanities education. We share elements of lectures, a field visit, and workshops that are intended to bring undergraduate students up close to asylum geographies of the past and the present. Creatively presenting extracts from individuals involved in the project, visuals and teaching notes from the walking tour of the old ruined asylum, patient case notes, and film footage from other psychiatric places will reveal how we encounter Gartnavel as a geo-history. Our intention during Asylum Week—and in this article—is to demonstrate how Asylum Week unsettles student assumptions about madness and illness by creatively illuminating shifting forms of medical intervention on the human mind and body.

Timing Asylum Week

Asylum Week defies its temporality and commences the May before the October, as e-mails fly between a university and a hospital, confirming dates and intention. The pedagogical frame for these messages is Embodied Social Geographies, a senior honors degree course in Glasgow University that sets out to encounter human fleshy space via ideas, words, text, image, and footfall. Asylum Week draws out, and on, embodiment as madness, crafted as a series of insights and provocations as to how mad bodies have been contained and cared for in various times and places.

By autumn the leaves are fallen on the long lawns that sweep upward toward the old West and East Wing of the hospital. Tipping the peak of a rounded hill in Glasgow’s West End, the ruins of what were the original buildings of the Gartnavel Royal Hospital in Glasgow still stand defiantly against the worst of the weather (). The asylum is approached not only with reference to these stately present remains, but through an animation of words and worlds that are framed by a version of geohumanities. Like Lorimer and Murray (Citation2015), “[w]e are interested in the ruin as an operating site of experiment, as a forum for open investigation” (58). Refusing the closure suggested by both any conditioned cultural response and the forbidding materiality of aging architecture, Gartnaval is understood through cowalking and coreading its place-time as a location for disrupting stories of mad or ill embodiment.

Coproducing Asylum Through Walking, Talking, and Text

Lecture notes on asylums, gathered via history and geography, convey interdisciplinary sensibilities, dated facts, and academic stories of “the extraordinary spatial history of these diverse spaces” (Philo 2007a, 108). Tangible ripples affect the classroom as calls are made for “stout shoes” and “sensitivity” as we plan itineraries and pack imaginations. The space of the asylum becomes but also unravels. The current consultant psychiatrist welcomes the geographers to Gartnavel’s modern replacement (est. 2007), constructed in the shadow of the first, with talk of “cappuccinos in the café,” spaces for “rights and justice,” “sanctuary,” and the need for respectful medical places (). This slick space, corridored with artful side effects, throws into relief the disciplinary history of medicine’s fall on patient bodies.

FIGURE 13 Students encountering the “Sanctuary” room in Gartnavel’s new hospital building. Photo by Hester Parr. (Color figure available online.)

The contemporary chatty clatter of people returning to their wards disrupts us and lectured narratives. Such spatial occupations appear at odds and distant from the panoptic clinic and its incursions into flesh.

“So the patients go for a walk if they want to?”

We take to our feet. Clues of past lives and practices litter the landscape as the group weaves carefully through the grounds, but the experiential nature of asylum life remains for many, frustratingly, at a distance. With this in mind Asylum Week turns to the inside to explore the “liquidity of architecture” (Cache Citation1995) and the various embodied, emotional, and affectual experiences that asylum inhabitation can take.

“Are the patients always under observation?”

The site walk provokes and unsettles, casting shadows that cross the old and new. New signs of care, treatment, and landscape geographies () cause students to tread uncertainly beside the old ruin.

FIGURE 14 Landscaped walks signposted in the hospital grounds. Photo by Hester Parr. (Color figure available online.)

After tramping the contradictions of Gartnavel via foot, the classroom workshops invite another incursion, this time behind the shuttered doors of the ruin and encountering internal architectures, emotional terrains, and archived bodily experience of mental health care and mental illness. Teaching through the historical materialities of asylum life allows for the appearance other spatial stories.

Dialoguing the Classroom and the Asylum

We begin with ghosts. We consider the experimental practices of psychiatrist R. D. Laing (1927–1985) who implemented spatial reform in Gartnavel during the 1950s (McGeachan Citation2017). Through Laing’s handwritten archival notes and published Lancet article, students are taken into the female refractory ward () and glimpse over sixty women in white cotton dresses scattered across the ward in different poses: some sitting against the walls, lying on the floor, hiding under chairs, or furiously lashing out as they propel themselves down the narrow ward corridors. Laing devised a one-year experiment called “the rumpus room” to spatially reconfigure refractory space with the hope of developing different interpersonal relations between patients and staff. The experiment takes the form of a separate room where twelve of the most isolated patients are taken to work with nurses and given an autonomy previously unavailable in the refractory ward. Students imagine “the rumpus room” from fragments that remain and map out the complex relationships between bodies and environment, enlivening the ghosts of the ward and their sociospatial encounters ()

“What did the room look like, how did it feel to be in the space?”

FIGURE 15 Gartnavel’s East Wing’s refractory ward from the outside. Photo by Hester Parr. (Color figure available online.)

FIGURE 16 Student animations of the “Rumpus Room” experiment. Photo by Hester Parr. (Color figure available online.)

Considering Gartnavel’s dead through the words that remain offers unique opportunities to ponder the lived realities of inhabitation in such spaces; what might it have felt like to feel enclosed, to hear the shuffle of footsteps in the darkened ward, to experience anger at incarceration, to see the pain of others. As such, we hear Frances Beaton silently screaming with frustration as she was taken from the open plan dormitory on the first floor to a single locked room several flights above. She had lashed out again. Traces of her experience persist in the letters she carefully crafted during her time at Gartnavel, buried deep within her case note records (Morrison Citation2013). Patient narratives unsettle understandings of psychiatric history. Questions ripple around the room as students encounter Frances as a person and not just a patient; her hopes, dreams, passions, and frustrations. Words constitute a new complexity of psychiatric understanding. The past presents “felt moments” (Jones Citation2007) etched in diagnostic case files and a flashing personal pen. Flesh appears on institutional bones.

“Was Frances really mad?”

A further classroom workshop questions Gartnavel and its histories of corporeal restraint, by bringing spatially distant “psychiatric bodies” closer via the harsh blink of 1970s strip-lit incarceration. Hurry Tomorrow (Citation1975), a documentary film taking place inside a locked state mental hospital ward in Los Angeles, is shown, jarring our conventional historicisms. Arse-out jags and collapsing men (), weeping at the modern brutalism of a crude psychotropic regime rushes Foucault (Citation1961, Citation1977) back into sight. The film animates patient bodies, a visual docudrama, presented in corporeal frames that evoke lungful gasps. The classroom becomes the asylum as its horror slips affectively from the screen. Someone leaves the room. Asylum Week concludes.

FIGURE 17 Injection scene in Hurry Tomorrow: Stills from http://www.richardcohenfilms.com/hurry_tomorrow_Scenes.html; used with permission of Richard Cohen Films.

Geohumanities in Creative Educational Practice

By offering a snapshot into Asylum Week, and representing a selection of the questions and comments that students made, this article seeks to showcase a disruptive project that experimentally explores the past and present of a psychiatric facility through ideas, words, text, image, and footfall. Questions arise over what Gartnavel, as an interactive and penetrable site, and as an exemplar medical space and place, becomes through the geohumanities practices (Hawkins et al. Citation2015, 213)—a creative juxtapositioning of walks, talks, and different kind of texts—involved in our teaching of embodied social geographies. Arguably, it has become a more confusing space where ideas about psychiatric and medical intervention on minds and bodies come into muddied contrast with the transformation of mental health care across time and space. It also becomes a felt encounter, serving to affect and humanize asylums as diverse place-times. Undertaking this experiment in the medical health humanities of an asylum shows the pedagogical potential of working across different media and through practices designed to encourage critical and creative responses to understanding madness and illness in psychiatric settings.

“I was very surprised and I found it shocking. I learnt a lot about the differences between current mental health care and historical mental health care. It was really an interesting and rare insight.”

“[Asylum Week] allowed a deconstruction of the ‘perfect utopia’ that the medical profession often views as their approach to mental health.”

“Asylum Week was good at getting us to experience the course through our own bodies.”

RIGHTNESS, PLACE, AND HUMANISTIC HEALTH CARE ETHICS: FRAGMENTS OF A MORAL INQUIRY

Arthur W. Frank, University of Calgary

Fragment One: Rightness and Place

Rightness might not always begin with place, but often it does. Novelist and essayist Joan Didion, in notebooks from the 1970s but published only recently, wrote:

Part of it is what looks right to the eye, sounds right to the ear. I am at home in the West. The hills of the coastal ranges look “right” to me, the particular flat expanse of the Central Valley comforts my eye. The place names have the ring of real places to me. I can pronounce the names of the rivers, and recognize the common trees and snakes. I am easy here in a way that I am not easy in other places. (Didion Citation2016)

Didion evoked rightness as a prereflective response to landscape, to certain words including names of things, and to the presence of things as part of what should be there. Rightness is a gestalt recognition of what fits, what has a proper place in a particular place, and what establishes the relation of one’s body to that place. Rightness predisposes experience. Didion (Citation2016) experienced the trees and snakes of California differently than I would. She knew through the relation of her body to a place that is distinctly its own—a place to which we give the honorific name of home. Home is where we are “easy,” as she wrote: “easy here in a way I am not easy in other places.”

Didion’s (Citation2016) sense of rightness as part of a literal landscape can be taken into the world of health care through a segment of the physician and writer Abraham Verghese’s (Citation1994) first book, My Own Country. Verghese had lived a cosmopolitan life in Africa, India, and the northeastern United States before arriving in Johnson City, Tennessee, to practice medicine in the early 1980s. Most of his work was as an infectious disease specialist during the early days of the AIDS epidemic, but he also practiced in the local Veterans Administration (VA) hospital, where his patients had more routine diseases. Here he offered a narrative linking the experience of disease to place.

Over a hundred persons with lung cancer were cared for each year at our VA. It seemed to me that, unlike AIDS, there was no shame in cancer, not lung cancer, not in Tennessee. The patients were in a curious way prepared for it. Anand, my oncologist friend, who was overwhelmed and perhaps slightly disillusioned by the amount of cancer seen at the VA, said to me: “It’s a bloody badge of honor. I happen to be here some Sundays and I’ll see whole families, several generations, around the patient’s bed, with the patient in the center, on the bed, kind of in the role of hero. You fought for your country, you smoked tobacco that the army gave you—the same tobacco that your father grew at home, that you helped harvest and put on stakes and hung up to dry; the same tobacco that John Wayne and Bogart smoked. Then you got lung cancer years later—it’s a goddamn war wound.” (257)

Verghese (Citation1994) told patient J. R. he probably had lung cancer, and J. R. responded with a stoic, “If that’s what it is, that’s what it is” (259). Verghese concluded, “I saw him head off to the smoking room, his hand reaching for the Marlboros in his dressing gown. A chorus of male voices greeted him. He fired up his cigarette and took his place next to his mates and watched Vanna spin the wheel again” (259).

The physicians who are not of that place have to construct a narrative to understand J. R.’s response to the news of having lung cancer. To make sense of their patient, they must relocate themselves in a place that is also a narrative that has its distinctive rightness. Rightness, here as elsewhere, does not necessarily correspond to what is welcome or pleasant. Didion did not necessarily want to encounter a snake, but she knew their names and accepted their fit as part of the landscape. In Tennessee, among J. R. and his mates, lung cancer was not welcome, but it had a rightness, just as it’s right to have a certain television show playing in the background.

In Verghese’s (Citation1994) narrative of lung cancer, rightness extends from place, including the economy specific to the ecology of a place, to historical circumstance—fighting wars—to popular culture; these complement each other in an enlarged landscape. Disease becomes part of this landscape, an accepted consequence of being committed to what a landscape expects of a person. J. R.’s stoicism reflects the force of commitment to his place and its expectations. Verghese’s humanistic insight, his version of narrative medicine, begins with putting his patients in place. A medical textbook might discuss the epidemiological distribution of a disease across places, but for textbook medicine, speaking of “Tennessee, World War II-generation lung cancer” would make no sense.

Fragment Two: Conflicted Rightness in the Clinic

The social scientist Renée Beard (Citation2016) described a sort of place that is not a landscape like Didion’s California or Verghese’s Tennessee, but it is an “environment,” a culturally specific geography. This place is a geriatric assessment unit in a clinic. “The environment within which the neuropsychological battery of tests was administered felt foreign to the overwhelming majority of respondents,” Beard reported, “and the sterile and uniform context created interactions that were awkward since typical norms of engagement did not apply” (94). Talk with its “typical norms of engagement” is part of the rightness that patients bring to the assessment clinic, but the clinic has a different rightness, although no one will say this. Beard’s ethnographic description presents a conflict between what seems right to the physician, allowing him to behave as he does, and everyday rightness of respect during talk.

Mrs. S began telling [the neurologist] about her experiences with depression. This 80-year-old woman was talking about how she always wanted a daughter … and said that when she thinks about the miscarriage 45 years ago she gets particularly upset because maybe that would have been a girl [who would have helped her with her present troubles]. Mrs. S began to cry quietly. At almost the exact moment, the doctor’s pager went off. He immediately grabbed the pager, looked at it, and picked up the phone without excising himself or even making eye contact with Mrs. S. By the time he finished his call, she had fought back her tears and didn’t bring up her depression again (nor did the doctor). (Beard Citation2016, 95)

Two senses of rightness are opposed in this fragment. One rightness might be named “commonsense politeness.” When one person pours out her heart to another, that other has a responsibility to sustain attention to the distressed person. That can be understood as a moral responsibility: an obligation humans have to each other. Rightness would require staying with Mrs. S and deferring the page. A different sense of rightness seems to inform the physician’s behavior; we can call this “clinical necessity.” The neurologist’s sense of rightness concerns the scope of his professional responsibility, what he defines as making a difference in his work, and what he believes he needs to do to manage the amount of work he confronts each day—to serve all his patients. The neurologist’s workplace engenders habits, and what is habitual comes to seem right.

These two senses of rightness sail past each other. The interaction teaches Mrs. S a significant lesson about what she can and cannot expect from health care professionals. Her sense of what it is right to bring to future encounters has been shaped. As Beard (Citation2016) wrote, Mrs. S does not bring up depression again. Many clinicians would count that as a troublesome outcome. The neurologist in question might well respond to criticisms with exasperation, however. Years of training have gone into his sense of the rightness of responding first to the pager as claiming primacy of attention. Or more specifically, responding to the pager is right in the clinic. For many clinicians, how the neurologist acts would have an immediate plausibility. On this workplace-driven account, doing that work entails coming to see certain collateral damage as right. In Beard’s fragment as in Didion’s evocation of California and Verghese’s narrative of his patient J. R., place conveys its distinctive sense of rightness.

Rightness and Ethical Worlds

The anthropologist Webb Keane (Citation2016) came to a conclusion consistent with my sense of rightness: “Given the complex histories of human communities,” he wrote, “we should not assume in advance that their ethical worlds can be fully reconciled with one another or even, in any given instance, remain stable and internally consistent” (100). The medical anthropologist Cheryl Mattingly (Citation2014), reflecting on clinical scenes, said much the same thing: “The terms of disagreement rest upon such profoundly different assumptions that a kind of moral incommensurability or, at least a deep mutual misunderstanding characterizes it, making it very difficult for the quarreling parties to recognize the terms of their difference” (155).

In each of my three narrative fragments, you have to go there to get it. Maybe you even have to be from there. The problems for a humanistic medicine generally, and for bioethics specifically, is how far one person can enter the country of the other, feeling the sense of rightness that is part of that landscape. Across what Mattingly (Citation2014) called moral incommensurabilities, what acts that seem right to some people are intolerable to others? When might acts and attitudes be properly resisted, despite their fit with a place and its rightness? I join those who believe there are a core of human rights and responsibilities that cut across localities. The rightness of place demands respect, but it does not have the last word. In ethical life, there might be no last words.

CONFIDENTIALITY, CREATIVITY, AND ETHNOGRAPHIC FICTION

Lindsay-Ann Coyle and Sarah Atkinson, Durham University

The following extract is drawn from research in the northeast of England with people living with multiple illnesses or disabilities who frequently experience not fitting in, not behaving in expected or acceptable ways, and not feeling valued in various contexts (Coyle Citation2016).

Going to See the Doctor (Again): Kelly’s Experience

The dizziness was just the latest in a long series of problems that I had experienced in recent years and it was getting to the stage whether I wondered if there was any point in consulting a doctor. So what if I have been feeling dizzy? I am getting old and these kinds of things are just part of the course. Unfortunately, I had made the mistake of losing my balance whilst trying to make a cup of tea. That was enough to get my very assertive daughter-in-law straight on the phone to make an appointment to see the long-suffering GP.

In advance of the appointment my mind was running through how I would explain my presence at the surgery. Obviously I would have to speak about the incident involving the cup of tea, making sure to omit details that will take too long to explain in the short time slot provided. But it’s quite hard to stick to “the facts” during these appointments. I’ve grown so weary of trying to work out which specific symptoms might be relevant to making a diagnosis of yet another condition. For instance, at my last appointment I complained about not being able to get to sleep at night. The doctor said this “insomnia” (another problem to add to the list) could be caused by any one of the ailments previously listed in my medical records. It has just become impossible to isolate any one of my existing (or new) symptoms to a particular illness category. So whilst I know that trying to mentally prepare for the next doctor’s appointment is futile, I seem to get anxious in advance of the process. Clearly you have to wonder what the point is in wasting the doctor’s time when I know she won’t be able to work out what’s causing the problem … and finding a solution would be as likely as winning the lottery.

People living with multiple conditions of ill health each experience a distinct and often unique constellation of symptoms, diagnoses, treatments, and responses. In such cases, the conventional reporting formats for qualitative and narrative research render the research participants able to be identified by their peers or the professionals supporting them. As such, protecting their confidentiality is not always possible. In this account, “Kelly” mentions symptoms of dizziness and insomnia that follow other complaints, their associated medication, and that her multiple conditions are of long duration. She mentions her daughter-in-law, who is proactive in pushing her for treatment and, even in this short extract, might be relatively easy to identify. The conventional route to avoid this inadvertent breach in confidentiality is to avoid direct quotations and to summarize types of experience across participants.

This solution, however, loses the power that a firsthand account carries to engage the reader in the everyday experiences of interest to the research. Here, Kelly’s account moves back and forth between the medical and the everyday, the specific diagnoses and the whole life experience of living with multiple conditions. Her voice, variously expressing irritation, resignation, and moments of humor, brings the realities of living with multiple conditions alive by engaging the reader with a person whose character begins to take shape and who we begin to imagine. Without this account, the lack of such characterization constitutes a significant loss to the evidence being offered:

My daughter-in-law had agreed to stay in the waiting room whilst I went into speak to the doctor. There was no need for her find out any more information about my various conditions than she had already amassed. Somehow she now seems to know about every aspect of my past and present bodily problems! I hate that I can’t have complete medical confidentiality now because my problems have become so obvious to other people, with me even having to depend on others to do some things for me. The doctor was smiling as she came to collect me from the waiting room. It must be a front—surely she can’t be that happy when listening to people’s problems all day.

Dr. Carson led me into the room and I took a seat. There always seems to be an awkward silence after we sit down. I’m not sure who should speak first—her or me? I begin by apologising for taking up her time again but say that my daughter-in-law made the appointment because I became dizzy whilst making a cup of tea, causing me to trip over the cat and spill the tea onto my right hand. Before I can say any more, the doctor starts asking me a series of questions: Have I felt dizzy at any other point? Am I eating at regular intervals? Am I taking all of the medication prescribed to me? I always try to follow the advice the doctor gives me but sometimes I feel like she is trying to blame me for some things. Heaven forbid I hadn’t eaten my porridge on the morning I felt dizzy—clearly it would then be my own fault I burnt my hand on the tea. Anyway the chance of my daughter-in-law allowing me to regularly skip meals is slim to none!

The doctor then goes on to ask how I feel “in myself.” But does she really want to hear or even have time to hear the honest answer? The truth is that I don’t feel that I have much to live for now. I’m aged 74 and I’ve had my time. I worked as a teacher for many years and although the work was hard, it was rewarding. I used to be so involved in the community and I felt like I actually made a difference to the lives of the people I taught. Now I just sit at home all of the time. Large parts of the day are filled by watching awful programmes on the TV. Living with chronic pain means that I can’t walk for far so I don’t get out that much. I need to be ferried around to places by people who would rather be doing other things. The only interesting things I can talk to other people about are set in the past—nothing good is going on in the present.

A creative solution to mediate these two undesirable options of risking confidentiality or losing voice is afforded by the ethnographic fiction (Inckle Citation2010; Bruce Citation2014). This is a composite account that draws on and brings together data generated during the research process from various participants and presents them as a single narrative. An ethnographic fiction allows the use of the empirical data to create stories that introduce and explain the importance of key ideas (Inckle Citation2010; Bruce Citation2014). Taken as a whole, any one story is not “true,” but rather it brings together key themes discussed by a number of people in the process of conducting interviews. The story presented here of “Kelly” is such an ethnographic fiction created from accounts of people living with multiple conditions (Coyle Citation2016).

There are several ways that an author can generate this type of work. A more systematic approach aims to remain as faithful as possible to the data and so creates an account that contains a particular proportion of direct (or only slightly amended) quotations from a number of participants. The disadvantage of this approach is the danger of producing quite badly written pieces in which the flow and plot typical of any one account are seriously compromised. An alternative is to generate pieces of ethnographic fiction as characterization, by first thinking about the fictional character that will be the “voice” for the data. The research author reflects on the experiences that participants narrate during the research and seeks to weave the broad themes along with intricate details into a storyline. For example, the piece of ethnographic fiction presented here through the character “Kelly” captures common difficulties reported by many research participants in negotiating clinical encounters and the practices of diagnosis (Coyle and Atkinson Citation2017) within the wider context of their lives. The creative process of producing these fictional characters is no different from other qualitative research that has always to consider how to balance individual and collective experiences (Davidson Citation2003). This creative approach to writing is particularly appealing because it enables ideas to be communicated in an impactful way. For example, these pieces of ethnographic fiction offer potentially a more interesting entry point for discussing the research ideas with participants or research users compared with an academic article. They also allow a significant level of detail that can convey the prolonged and multiple challenges faced by those living with multiple conditions. Although quotations often provide examples of a particular snapshot in time, an ethnographic fiction can communicate information across an array of aspects of experience.

But I know the doctor can’t really help with any of that so I just say to her that I am trying hard to get on with life. Despite this, the doctor suggests we might need a review of my care plan. She thinks it would be beneficial for me to attend a day centre a couple of days per week. I feel like I’m just in that transition stage between independence and complete dependence on others but I don’t really have much choice in it so I agree with her suggestion. Anyway it might be good to get out and see other people. Additionally, the doctor says that she will book me in with the nurse to get blood drawn in the hope of finding out the cause of these dizzy spells. So that’s yet another appointment to attend. I know there are no straight-forward solutions available so I just smile at the doctor as I walk out of her room.

THE PRODUCTION OF PRESENCE: THE INTERNET AND FIRST-PERSON ILLNESS NARRATIVES

Nehal El-Hadi, York University

One of our most powerful forms for expressing suffering and experiences related to suffering is the narrative.

—L. C. Hydén (Citation1997)

Part 1: Narrating Illness

Canadian author Thomas King, in his 2003 Massey lecture, repeatedly stated that “[t]he truth about stories is that that’s all we are” (King Citation2003). He meant, I think, that our personhood comprises all the stories we carry with us: our histories, how we perform ourselves, our ancestries, our possibilities. At its very simplest, a story is a sequence of events related by causality that occur over time. Frank (Citation2009) explained that stories are “the spoken expression of narratives,” where the narrative is “given local instantiation and specific detail” (107); stories are made unique to the storyteller through their own perceptions, memories, and editorial choices.

The role of narrative in the health care setting is to convey the patient’s experience—here, narratives instantiate symptoms, chronicle manifestations of disease, and detail the moments of dis-ease. Patients describe their symptoms and respond to questions, and health care providers begin with the produced illness narrative to determine their approach to investigating, exploring, and treating the condition. The value of narrative to health care provision is established, as it “proposes an ideal of care and provides the conceptual and practical means to strive toward that ideal” (Charon Citation2001). Ensign (Citation2014), however, pointed out that this ideal of care “assumes an ideal encounter between an empathic physician and a cognitively intact, compliant adult patient,” and that narrative medicine “largely ignores the limits of narrative, especially within the contexts of trauma, suffering, and oppression.” Training in narrative competency and humility requires exposure to the illness (and well-being) stories of others beyond the clinical setting, especially recognizing that the narrative encounter between patient and health care provider can replicate or reinforce the same power relations that disadvantage members of certain groups over others, and so,

It will not be enough to listen to the voices of those who have been marginalized, and to understand the historical genesis of oppression. There needs to be the collective willingness to deal with systemic discrimination which structures life opportunities. These are health and health care issues. (Anderson Citation1996, 704)

I am drawn to the role in which narrative shapes the encounters between health care providers and individuals from marginalized populations, specifically, the ways in which health inequities are performed in the exchange (or absence thereof) of knowledge. In addressing health care inequities, then, health care providers require training in narrative humility to address “the hierarchical imbalance of the clinical relationship” (DasGupta Citation2008). In Stevenson’s (Citation2016) call for “an ethics grounded in narrative,” the author presented the case for:

the narrative competency to engage with and respond to the stories of sickness and health that may arise from cultural contexts other than our own, and which explores conceptions of self and community formation, as multiple and diverse and marked by porosity. (Stevenson Citation2016, 367)

Stevenson (Citation2016) was addressing narrative ethics in Indigenous community-based research, indicating that the ability to deconstruct narratives is a vital skill necessary for providing inclusive and effective health care.

In the health care setting, illness narratives emerge during exchanges between the health care provider and the patient (or their proxy) held in specific sites: the examination rooms of clinics, hospital wards, offices—small spaces that are clearly circumscribed by their white or off-white walls, inoffensive décor, and the smell of strong disinfectants. I draw attention to these sites of production deliberately, to advocate for the consideration of online spaces as also being sites of production of illness narratives, especially for individuals who belong to marginalized communities, where “local instantiation and specific detail” (Frank Citation2009, 107) of their illness narratives might emerge in online spaces. Specific sites include personal blogs chronicling the illness experience, community forums or chatrooms built around specific conditions, and social media networks.

The production of presence is the creation, management, and distribution of content and stories that center the marginalized individual and reflect the being-in-the-world of marginalized groups in deliberately authentic and representative ways; these produced narratives then counter dominant hegemonic discourses of everyday life by providing alternate retellings and imaginings of everyday lived experiences. For the patient engaged in the production and consumption of this material, it goes beyond the catharsis of blogging, beyond mere visibility, to an affirmation and acknowledgment of the patient’s life and experiences, and to feelings of connection and belonging. Online user-generated content can do so for the patient by providing visibility and validation, reducing feelings of isolation through access to community and support, providing a source of interpreted information, communicating through a different medium, providing the opportunity for more authentic or intimate communications, and circumventing time limits and distractions, resulting in catharsis from the ability to express.

Government health institutions have established policies on the Internet, from producing Web sites, designing online awareness campaigns, networking health care providers, and monitoring disease outbreaks. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada, 2014 includes a section called “Digital Technology as a Tool for Public Health” that describes the ways that the government can use technology to “improve, promote and monitor health,” including the possibilities presented by social media in “the sharing of information.” The document focuses on digital technology as a tool, and suggests that public health not exacerbate existing inequalities by considering “any barriers that may exist for the user or the recipient, such as language, culture, literacy level, geographic location, etc., to avoid potentially increasing any health inequalities when implementing technology-based tools” (Public Health Agency of Canada Citation2014, 36). What is absent in this document is an acknowledgment of user-generated content as a resource in understanding the experiences of illness and treatment. I hope to provide the starting point for an engagement with these online repositories of first-person illness narratives, suggesting that the study of these first-person narratives can provide valuable data.

In a January 2015 briefing note, the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy noted,

The benefits for health professionals of using social media include an increased number of interactions, shared and tailored information, increased number of sources of health information, spaces where health issues can be shared and discussed by different audiences, and provision of peer, social, and emotional support for the public. (Newbold Citation2015, 3)

For the health care provider, online narratives studied collectively can enrich medical histories, shed light on unknown portions of the patient’s life, provide feedback on treatment and care, provide opportunity for more authentic or intimate connection, assist in advocating on behalf of patients, and reveal patterns and provide insights into the experience of illness.

The amount of user-generated information available online seems limitless with new social media platforms, apps, and blogs appearing on a daily basis. It takes a considerable amount of time to locate information, ascertain its accuracy and veracity, and then deconstruct and analyze the content. Yet, what can be gleaned from this content is valuable. As information generated from big data—large amounts of user-generated uploads—continues to gain influence in policy development and implementation, when it comes to the movement for increased access to personalized medicine there needs to be a push for more nuanced qualitative analysis of softer kinds of online content. For the health care provider, accessing these online narratives requires time and resources (including training); it would be of greater value to have these data gathered and analyzed by researchers, and then incorporated into the training of health care providers.

Part 2: Assemblage: Black Women and Breast Cancer

Black women writers have long been aware of the complex nexus of personal health, larger societal problems, and the challenge of locating the kind of medical care that attends to their needs as whole persons, as articulated in the lack of respect for a worldview centered on spiritual and religious factors that inform issues of wellness and illness.Footnote1

Researchers have known for decades that breast cancer takes a deadlier toll on black women.Footnote2

I ached to talk to women about the experience I had just been through, and about what might be to come, and how were they doing it and how had they done it, But I needed to talk with women who shared at least some of my major concerns and beliefs and visions, who shared at least some of my language.Footnote3

When comparing women under 45, African-Americans are more likely to get breast cancer than whites, according to data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program, cited by the American Cancer Association. … African-American women had a much higher risk of the disease being discovered at the most advanced, deadly stage.Footnote4

And then there’s my hair. Its just weird now. It’s so different now. It’s … ugh. It’s nice hair. I have to admit that much. It’s really soft and shiny. But it’s not Nicole-hair. And then again, it is. It’s just not the Nicole-hair I’m used to. It’s different.Footnote5