Abstract

In this exploratory piece, I read the material and metaphorical world of fashion for insight into the contemporary political condition. Drawing on my participation in a week-long professional training program in fashion and dress curation—hosted by the Victoria & Albert Museum (February 2018) —I examine curatorial practices as a methodological resource for engaging the limited and unstable spatiotemporal and subjective investments of modern politics. I suggest that fashion curation can reimagine and rematerialize political geographies and political subjectivities in the uncertain contexts of global urbanization, decolonization, and other contemporary challenges to political modernity. The narrative approach and visual documentation aim to immerse the reader in an experiential encounter with a curatorial methodology for feeling how the political world might be fashioned otherwise. This contribution works to mobilize and affectively engage readers in material metaphors for the complexities of contemporary spatiality and subjectivity.

在这篇探索性文章中,我解读了时尚的物质世界和隐喻世界,进而去洞察当代政治状况。基于我参加的由维多利亚和阿尔伯特博物馆主办的为期一周的时尚和服装策划专业培训(2018年2月),我考察了策划行为,将其作为一种方法论资源,用于吸引来自于现代政治的有限且不稳定的时空投入和主观投入。我认为,在全球城市化、去殖民化和其他政治现代化面临着挑战的不确定环境下,时尚策划可以重新想象、重新物质化政治地理和政治主观性。本文的叙事方法和视觉文档,旨在让读者沉浸在对策划方法论的体验中,以感受政治世界的时尚化。本文推动并在情感上将读者吸引到当代空间性和主观性的复杂性的物质隐喻。

En este escrito exploratorio, hago una lectura del mundo material y metafórico de la moda para dar perspicacia a la condición política contemporánea. A partir de mi participación en un programa de una semana para entrenamiento profesional sobre moda y curaduría de ropa –patrocinado por el Museo de Victoria & Albert (febrero de 2018)– yo examino las prácticas de curaduría como un recurso metodológico para comprometer las limitadas e inestables inversiones espaciotemporales y subjetivas de la política moderna. Sugiero que la curaduría de la moda puede reimaginar y rematerializar las geografías políticas y las subjetividades políticas en los inciertos contextos de la urbanización global, la descolonización y otros retos contemporáneos de la modernidad política. El enfoque narrativo y la documentación visual apuntan a sumergir al lector en un encuentro experiencial con una metodología curatorial, para sentir de qué otro modo se podría vestir al mundo político. Esta contribución busca movilizar y comprometer afectivamente los lectores en metáforas materiales para las complejidades de la espacialidad y la subjetividad contemporáneas.

FASHION CURATION AS AN AFFECTIVE METHODOLOGYFOR GLOBAL POLITICS

I approach the colonnades of the Sackler Courtyard with anticipation, gratitude, self-doubt, curiosity and a feeling of being totally out of place and exactly where I should be: about to begin a week-long international professional training program in fashion and dress curation. For this brief period, I will have an inside view of the Victoria & Albert Museum and its renowned world-class collections and exhibitions of historical and contemporary fashion, as I participate in dedicated sessions with senior curators, conservators, and mounting specialists, as well as research, marketing, design, and legal staff. From the Sackler Courtyard (), a museum employee leads me past security guards to seminar rooms in the gallery-white new wing, and soon I am embedded, with fifteen other participants from around the world, in an orientation to the complexities of fashion curation. For decades, I have turned to the material and metaphorical world of fashion for insight into the contemporary political condition. As a disciplinary outlier, I am here to investigate curatorial practice as a methodological resource for engaging the limited and unstable spatiotemporal and subjective investments of modern politics: words I stumble over when it is my turn to introduce myself to the gathered group of professional staff and participants.

Throughout the week of training, I pay close attention to esthetic registers, material objects, and my own affective responses. Reflecting on this week through narrative writing and visual documentation helps me capture aspects of material and sensory experience that ultimately exceed both the narrative and the visual. Through this process, fashion curation becomes a productive example of “ … research as practices (and methodologies) which remember that the politics of doing the visual are as material as matter is visual and that both are engaged beyond the ocular” (Rose and Tolia-Kelly Citation2012, 3). This training program inserts me directly into a world of practice that—as I gamely but clumsily tuck and fold, stretch and stitch—profoundly challenges my capacity to do what I set out to do. I come to recognize this as a paradigmatic and essential aspect of any work rooted in practice, where the sense of what might be produced does not materialize precisely as envisioned before beginning.

Just as the immersive experience of multiple modes of practice was central to my learning at the V&A, this piece is offered as an immersive experience of curatorial practices in the world of fashion. While I invite readers to reflect critically on how existing curatorial practices fashion the political world, I also want readers to feel how curatorial practice opens methodologies that work effectively against dominant, narrow stories of what politics is, where and when politics happens, and who gets to fashion politics.

The world of fashion—an everyday global site where practices of individuality and community are materially and metaphorically made—draws disparate phenomena into a complex enactment of people, communities, and politics. If, as Claire Wilcox has suggested, “[c]lothes are the shorthand for being human” (quoted in Taylor Citation2004, 1), then fashion and dress objects are boundary practices: between the fashionable and the ethnographic, the esthetic and the technical, the metropolitan center and the (colonial or rural) periphery, the dressed and undressed, the human and non-human and thus, in a range of related but non-identical registers, between politics and its limits. Though fashion and dress has been taken up seriously and productively within critical geography (e.g. Breward and Gilbert Citation2006; Crewe Citation2017), it has received little disciplinary attention in global politics (except for Behnke Citation2016). Current narratives of destabilization and transition found in the inter-related concerns of global urbanization, decolonization, and ecological protection highlight contemporary insecurities in the established terms of modern political geography and political subjectivity. Fashion is not the only practice that materializes and reimagines these insecurities. However, fashion touches us, intimately, continuously and differentially. It thus has a rare capacity to address issues of identity, collectivity, uncertainty and security in a deeply resonant manner.

Despite analyses of museum politics (Lisle Citation2006; Luke Citation2002; Sylvester Citation2009), fashion exhibitions receive even less disciplinary attention than fashion more broadly. Ling’s (Citation2016) reading of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition China: Through the Looking Glass—on Western fashion’s reflections of Chinese cultural dress—as an instance of positive orientalism is one example. Kuldova’s (Citation2014) description of a curatorial research project that critically engages with exhibitions’ tendencies to use “aesthetics” to mask hierarchies in international and economic power relations is another. These accounts argue that if the political body is a dressed body (Behnke Citation2016; Entwistle Citation2000; Parkins Citation2002), then how (and where, and whose) clothing is exhibited enacts public narratives of appropriate, visible, and sensible spacetimes and subjects of politics. I am viscerally struck by how fashion exhibitions actively reimagine and rematerialize political geographies and political subjectivities in the uncertain contexts of global urbanization, decolonization, and other contemporary challenges to political modernity. This seems clear, but also insufficient. Fashion curation—the work to acquire, conserve, exhibit and interpret garments (De La Haye and Clark Citation2008; Melchior and Svensson Citation2014; Scaturro Citation2018; Taylor Citation2004; Vänskä and Clark Citation2018)—is not confined to isolated political acts of public exhibition. Instead, fashion curation literally and figuratively invites participants to move bodily through material collections as well as spatialized interpretations (Leahy Citation2012), situate themselves within relations and disjunctures (Frisa Citation2008), and experience the esthetic gap (Bleiker Citation2009) between textile objects, material metaphors, and embodied dress practices. As such, it offers an innovative methodology for grasping how we fashion socio-political life through non-determinative somatic experience and embodied practice.

I explore curation as political methodology in this essay, particularly its capacity to engage, through practice, in the materialities and uncertainties of contemporary political objects, concepts, spaces, times, and subjects. The narrative approach and visual documentation aim to immerse the reader in an experiential encounter with a curatorial methodology for feeling how the political world might be fashioned otherwise. I offer an example of how this methodology might be used as a mode of social science research by narrating my own first foray into a co-curated installation of textiles and dress. This installation (part of the Falmouth Art Gallery’s Summer 2019 exhibition Stuff & Nonsense, curated by gallery director Henrietta Boex), invites visitors to participate in an emergent account of how subjectivities, connectivities, and spatiotemporalities are fashioned from the “stuff” of everyday Cornish life. The installation hints at how co-created exhibitions of fashion and dress might narrate, in affective, multi-dimensional, collaborative ways, these intimate and global (Pratt and Rosner Citation2006) practices of political fashioning. In reflecting on these practices, this contribution works to mobilize and affectively engage readers in material metaphors for the complexities of contemporary spatiality and subjectivity.

FEELING MY WAY TOWARD AFFECTIVE KNOWLEDGES

I wander through exhibition spaces grand and obscure, metropolitan and regional, taking in every fashion exhibition I can: marveling at silhouette, form, texture, color; imagining the weight or froth or flick or swish of a garment; moving through orchestrated yet undeterminable spatialized narratives; engaging in my own readings of the positioning of mounts and wording of interpretive labels. I feel how the practice of curating dress and adornment offers unexplored pathways for “a different kind of encounter with space, bodies, senses, time, objects and materials” (Lisle and Johnson Citation2018, 4). Such alternative modes of encounter are a crucial response to contemporary political uncertainty and are evident in the way that analyses of visual-esthetic-material sites are stretching into engagements with critical creative practice. From my time moving through exhibition spaces, I sense that fashion curation suggests ways of working productively with difficult tensions, paradoxes and uncertainties that plague political analysis: between materiality and immateriality; object and concept; esthesis and techné; presence and absence; chronological linear history and the looping temporalities of narrative, nostalgia and conservation; two-dimensional and three-dimensional space (De La Haye and Clark Citation2008, 154, 155, 158; Mida Citation2015; Scaturro Citation2018). Within its careful planning and structuring, the exhibition is explored and engaged differently each time, by each visitor, creating multiple and indeterminable paths through these analytical challenges.

And then I find myself, not in an exhibition space, but at The Clothworkers’ Center for the Study and Conservation of Textiles and Fashion. The Clothworkers’ Center is the current off-site fashion storage and research facility of the V&A, housed in Blythe House in nearby Kensington Olympia. We crowd into an industrial elevator and rise through the floors, architecturally reinforced to support the weight of so many garments and their intricate storage system of rails and drawers, movable racks and wheeled plinths. We are introduced to the back of house “ghost labor” that Scaturro (Citation2018, 23–27) describes as the necessary material but too often invisible companion to the high-profile front-of-house activities of the fashion curator. Here, at The Clothworkers’ Center, fashion conservators stitch in object ascension labels by hand. They determine the dimensions of garment bags for safe storage. Sewn by volunteers, each bag is shaped to fit a unique object, which itself is also made, often by hand. They balance ethical, material and esthetic requirements in every touch, “with the ultimate goal being that the conservator’s hand should not be seen once the object is put on display” (Scaturro Citation2018, 27; emphasis in original). Staff at The Clothworkers’ Center facilitate access to the material objects in the collection not only for the curatorial teams but also for researchers and the interested public. The Center is thus a crucial site for the development of in-depth object-based knowledge (De La Haye and Clark Citation2008)

Everything here, everywhere I look, is a testament to hours of work and is now an object with a distinct meld of technical and esthetic capacity. Fashion and dress curation, both within the exhibition and in the back of house, is without doubt a distinctive encounter with the generative energies of visual spectacle. Yet it is so fundamentally, so clearly material, embodied, and multi-sensory. As such, it stages an intersection between two forms of political economies. In the first, affective economies give material form to subjects and objects through circulating repetitions of emotions that are both sticky and slippery (Ahmed Citation2004). In the second, esthetic economies stabilize the value of objects (and with them, subjects) through every instance of touch and selection by holders of embodied knowledge (Entwistle Citation2009). The intersection of these political economies within fashion curation—with their attendant configurations of political space, time and subjectivity—collides in my imagination, sparking sensations of excitement and trepidation for possible interdisciplinary and trans-sector collaborations.

Yet I also experience a jarring juxtaposition between these multiple forms of accumulated material heft and the airy, ghostly presence of individualized white garment bags and white mounts in various stages of specification for an intended but absent garment (). I am haunted by what is not material in this space, the hauntologies of absent subjects and missing bodies (Mida Citation2015), which evoke the uncertain and unstable subjects of contemporary politics. If “at the center [of fashion curation] there is always the imagined body, the past real body for which the installation [of objects] is a surrogate” (De La Haye and Clark Citation2008, 160), then this encounter can be read as a metonym for the presence of the surrogate subject of politics: always already a projection into the past and the future; always already an installation of the materiality of embodied subjectivity. I feel myself as this uncertain subject figure, both under wraps and exposed as a novice within this professional field, bereft of any sense of expertise or experience that might give me a place here. While moving physically through the space of The Clothworkers’ Center, I begin to feel first-hand the somatic knowledge generated by curation as a hands-on practice that circulates affect and establishes value. However, I also feel the fractures and partial enactments that come from locating myself within an under-determined position: no longer secure in my identity as a lecturer, certainly not identifying as a professional curator or conservator.

My research into the material metaphors of contemporary political subjectivity and space begins to feel different as a result of this self-displacement within a site of knowledge production through hands-on practice. Judith Clark (De La Haye and Clark Citation2008, 160) suggests that curators take “the presumed truth of an object” as a place to start in developing a curatorial thesis, but that the juxtaposition of material presence and multiple absences in an object necessarily entails other narratives to emerge. If fashion curation challenges modern epistemologies of politics as rational, objective and disembodied and opens modes of knowing as somatic, circulatory, collaborative, and relational, it also challenges modern ontologies of politics as centralized, controlling authority and opens modes of non-determinative, fractured, and perpetually, productively insecure enactments. I become increasingly aware of embodying and working within the conditions of political and methodological uncertainty I seek to understand.

FASHIONING POLITICS AGAINST THE “MATRIX OF SOVEREIGNTY”

There are so many garments to marvel over at The Clothworkers’ Center: the original Dior bar jacket and full skirt from the debut New Look collection (1947); Alexander McQueen couture, under white wrap but briefly exposed for our gawking and giddy appreciation; centuries of kimono displaying shifting fashions as responses to internal sumptuary laws, competing empires, and emerging international trade patterns; a state gown of thickly embroidered metallic vine and beaded, pearled flowers, worn by Queen Elizabeth II in France in 1957, designed by Norman Hartnell to evoke namesake “Flowers of the Fields of France” (). This dress is an obvious site of the performative enactment of sovereignty and the shifting practices to embody its glory and majesty (Behnke Citation2016), a material metaphor for political security in the figure of the sovereign and the structure of sovereignty. But to read it in this manner is to activate what Huysmans (Citation2003) calls “the matrix of sovereignty:” the primary capacity of sovereignty to center itself as the only possible configuration of politics. Any possible disruption to the ontological question of “the political” by locating it in this particular dress is narrowed, by this matrix, to the question of how sovereignty produces or performs itself under given conditions or within given contexts.

Yet insofar as material metaphors create both meaning and form by establishing one concept or entity in relational terms with another (Fishel Citation2017; Lakoff and Johnson Citation1980; Shapiro Citation1985–1986), the ways in which this dress is politically operative extend beyond performative visualizations of sovereignty. The sumptuousness of the gown, its visceral extension of the subject into its surrounding space via embroidered flowers that grow outwards from the duchesse satin skirt, its circulation through published images and television footage at the time and during its periods of subsequent exhibition, emphasize how contemporary political subjects and spaces are sustained by both esthetic economies of value (Entwistle Citation2009) and affective atmospheres of nationalism (Closs Stephens Citation2016). The body of the wearer as a young monarch imposes itself on the materiality of the gown, most vividly on the bodice, surprisingly short and narrow; yet the materiality of the dress similarly imposes requirements on its subject, the internal corseting producing a slip of a waistline above the full, crinolined skirt, weighted as it is with the substantial embroidery. It is through the materialities of the dress itself that the subject is both confirmed as absent and yet still experienced as a felt body: the physical specificities of the body for whom the gown was made; the temporal specificities, as this subject body has altered over the intervening years such that the dress will never be worn again, except by an inert, carefully shaped mount; and the material and temporal afterlives of the gown, as it is carefully flipped in its storage drawer every six months to avoid flattening the namesake French flowers and Napoleonic bees.

Insofar as this is understood as a “visual” analysis, my encounter with “Flowers of the Fields of France” as a state dress demonstrates how “sovereignty always deploys a regime of visuality: it always makes itself visible” (Behnke 106: 117). However, The Clothworkers’ Center clarifies that curatorial practice engages politics beyond such performative accounts of the visuality of sovereignty. The work of storage and conservation exhibits the tension between the enactment of material agency (Squire Citation2015) and of vulnerability, immateriality, and impermanence, and thus the limits of sovereign ontologies of politics. This tension is paralleled in the materiality and impermanence of the storage facility itself: while only opened in 2013, after an extensive renovation project to create a suitable state-of-the-art space (including the reinforced floors and custom racks and drawers), the center will be permanently closed in December 2020, as the collections will be moved to the new Collections and Research Center, part of the V&A East in Stratford. Blythe House, a Government-owned building that also housed storage facilities for the British Museum and the Science Museum, was put up for sale in 2015. It was one of many properties identified as out-of-date, unfit for their current purposes, and more suitable for private property redevelopment into residences and hotels. “Flowers of the Fields of France,” worn by Queen Elizabeth in 1957, will come to rest in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in 2023, as an intersection of nationalist Olympic narratives, neoliberal austerity, and global urban regeneration and displacement in both central and east London. The practices involved in conserving, storing, and exhibiting this one gown—one among many, as the V&A has one of the largest collections of fashion, dress, and textiles in the world—are practices that articulate political limits not governed by the matrix of sovereignty ().

EMPLACING AND DISPLACING THE URBAN-FASHION NEXUS

I spend an inordinate amount of time photographing textures and patterns, in fabrics and garments and in the V&A buildings in South Kensington and Kensington Olympia (). I want to explore the patterns of political logics, other than the logic of sovereignty, which might be operative in this context. Specifically, I want to understand the patterns of practice that fashion political worlds under conditions of transition and uncertainty. In doing so, I am following hints in sources as diverse as Derrida (Citation2001, 333) and Law and Mol (Citation2001, 610–612) that material metaphors merge into patterns of practice, feeling, investment and enactment that can be used to trace topologically how logics of political configurations are made to “stick” and to “slide,” just as much as forms of political subjectivity (Ahmed Citation2004, 118–119). Throughout my time at the V&A, pattern becomes a productive and playful hinge concept, given its obvious relevance to textiles, to the construction of garments, and to the considered, design-oriented material spaces I move through. Pattern addresses temporality, dimensionality, and potentiality from multiple perspectives. On the one hand, a visual (or sonic) pattern becomes recognizable through its repetition in space and time. On the other hand, a “technical” pattern, as a collection of pieces designed to constitute a whole, “is a two-dimensional transition between the three-dimensional body and the finished piece of clothing … [that] carries within it the potential garment and, therefore, the potential body” (Debo 2003, quoted in Pecorari Citation2014, 55). The “landscape of the pattern” (Pecorari Citation2014, 55) that I work to map emerges in multiple scales and dimensions: from the textural specificity of woodwork, embroidery, tiled floors, and staircases, to painted and printed fabrics, to the repetition of new terms as conceptual frames and new techniques as practical scaffolding.

FIGURE 5 Patterns of the urban-fashion nexus. (Details, clockwise from top-left: wooden-panel cupboards at the Clothworkers’ Center, Blythe House, Kensington Olympia; tile in the Sackler Courtyard, Exhibition Road entrance, V&A; Edo-period kimono fabric, tie-dyed with saffron; textile undergoing conservatorial work, Clothworkers’ Center; Evening Cloak, Matilda Etches, 1949, on display in Gallery 40, V&A; 1930s dress, synthetic fabric, acquired with portrait of wearer/owner)

Many of these patterns—which emerge from the built environment of urban London, its prominence as a colonial metropole, and its claims as one of the four dominant modern Fashion Cities—speak less to the political logic of the matrix of sovereignty and more to the political logic expressed by the modern Western configuration of an urban-fashion nexus (Gilbert Citation2006; Wilson Citation2006). Where a “matrix” is the holistic environment of social, cultural, political and economic conditions under which something emerges (thus with all the claims of universality that sovereignty mobilizes), a “nexus” is the intersection of two distinct practices in a moment, site, or confluence (with all the echoes of the particularism that has been used to counter the excesses of sovereignty). Both express a logic of political configuration. Neither of these logics is neutral; neither is a solution to the other.

The urban-fashion nexus describes how practices of urbanism and fashion became co-constitutive of political space and subjectivity in modernity. The textured and textiled patterns through which the urban fabric emerges might disrupt forms of subjective and spatial ordering constituted by the state, but these patterns demonstrate that the urban-fashion nexus has functioned as its own site of hierarchical political ordering. These practices of ordering become clear in the colonial roots of urban planning as a discipline and the colonial roots of the V&A as an institution born from an exhibition of Empire’s wealth and progress. They become clear in the patterns that position the colonized and the rural as dual encounters with the limits of “fashion,” as either anthropological or ethnographic garments, or as parochial, practical, traditional country dress. While the logic of the urban-fashion nexus sometimes intersects with and amplifies the logic of sovereignty, sometimes it is divergent: the patterns of the urban fabric, when overlaid onto the patterns of the matrix of sovereignty, create a moirée pattern, syncopated, full of intensities and gaps.

I start to envision a curated exhibition of fashion and dress objects that puts these multiple patterns into play, using the shared space and time to activate an engagement with the multiple dimensions, scales, and temporalities of contemporary political life; to activate an affiliative sense of political subjectivity shaped but not limited by either the matrix of sovereignty or the urban-fashion nexus. Such an exhibition, if possible, would effectively and affectively materialize an alternative spatiotemporal logic (Law and Mol Citation2001) for emergent configurations of politics and political subjectivity.

WORKING HANDS MAKING (UP) RESEARCH

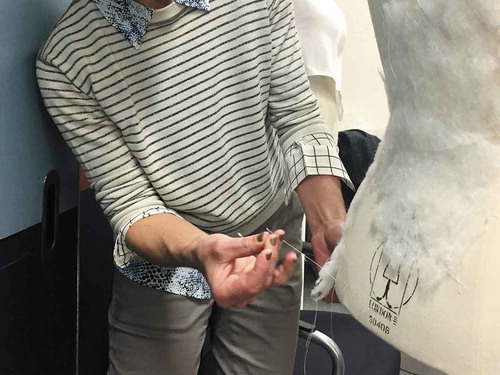

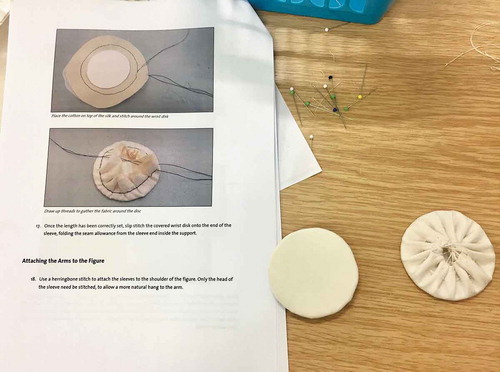

Somewhere past the intricacies of the ceramic staircase we pass through a narrow temporary hallway framed in plywood and decorated with posters from previous exhibitions. Notebooks in hand, we crowd into a utilitarian room, blank and preparatory with its white tiles and white work tables (). Today we are being taught how to modify standardized mounts to display dress objects. In the first room, we will practice thinning and layering cotton wool to pad hips and breasts, use a long, curved tailor’s needle and clumsy herringbone stitches to tack the padding into place, and then stretch and pin fine cotton jersey smoothly over the amplified shapes (). If we have been successful, our replica corsets will now fit snuggly into the mount, producing the requisite sense of a body pushed and shaped into place by the garment, the garment filled, and warmed by the body. In the next room, we will find mounts with pale silk skin at the neck and shoulders, the slim white femininity of the forms echoing the forms of subjective ordering that the “world” of fashion has enacted and for which it is now increasingly being held to account. We are learning here how to build the limbs required by specific garments and will work in teams to make padded cotton arms with shaped elbows and silk wrist-caps. I touch a sewing machine for the first time in decades and can’t run a straight stitch or turn a tight corner. I am better sewing, by hand, the silk wrist-caps, taking particular pleasure in creating patterns of careful spacing and repetition (). Bent over our work, we are both busy and free to discuss how this curatorial training fits with our disparate geographic and institutional settings.

I feel unsettled by the rush to complete these arms, all-to-aware of the disparity between the sample we were given and the finished pieces we have created. As we work collectively, these operative gaps multiply outwards and merge into a finished product that is both single and more than that, a tangible record of hands, touches, intentions, failures and completions. This work cuts through the mythologies of singular actors, linear capacities, and the controls of authorship. It demonstrates, through stitches, pleats and puckers, how curation works at the unstable intersection of practices that reconfigure authority, knowledge and order (Dewdney, Dibosa, and Walsh Citation2013) and practices that are rooted, etymologically and politically, in extending care to objects and, through them, to each other (DeSilvey Citation2017). The practice-based work of curation that I engage here—encompassing the work of conservation and mounting—works against all the mythologies of academic research and writing that my training invested in me. To understand it, I have to extend from social science qualitative and interpretive methods, based on textual analysis, that have been my familiar territory of academic knowledge production, to the methodologies of creative research practice (Leavy Citation2015; Smith and Dean Citation2009). I find it transformative, not only for my research, but for my teaching and my relationships with my students. Required to engage in a creative practice-based research project of their own, in my Politics of Fashion module, my students begin to experience the same sense of being an uncertain academic subject that I now have, and we grapple collectively with this somatic encounter with the uncertain politics of methodology and knowledge production.

COLLECTIVELY CURATING THE UNCERTAIN POLITICALSUBJECT OF CORNWALL

I am trying to twist lengths of wire around branches and in through hooks embedded in wood planks, while my colleagues hold branches splayed against the wall in hopes of creating a tree-like shape out of these prunings. We are working together, and with others not present in the gallery that day, to install a temporary cloutie tree. This installation invites visitors to participate in narrating how the textiles, fabrics and garments of their everyday lives connect them both to Cornwall and places beyond (). This summer exhibition at the Falmouth Art Gallery, titled “Stuff & Nonsense,” includes a collection of shrines that consider how and why we curate the stuff of our lives. Reconfiguring the public “audience” within a collaborative and participatory frame (Golding and Modest Citation2013), gallery director Henrietta Boex has invited contributions from artists, community groups, and others. I begin work with a loose collective of colleagues from the University of Exeter (including Garry Tregidga, Institute of Cornish Studies; Caitlin DeSilvey, Geography; Bryony Onciul, History; and Joanie Willett, Politics) on a shrine that becomes called “The Stuff of Place.” We root our shrine geographically in the Celtic cloutie tree: the fabric strips of wishes and prayers tied to trees over natural springs which are still visible at Madron Well, Carn Euny, and other sites in Cornwall. We root it etymologically in the original French meaning of the word stuff: the rough textiles meant for making up clothes or furniture. We envision using characteristic dress and textiles in Cornwall to evoke the varied patterns of affiliations of place and people, with strips of textiles chosen and tied like offerings on our gallery-installed cloutie tree. We imagine rotating displays of garments—bardic blues and Cornish rugby shirts, tartans and neoprene—that shift the story with each new pairing.

The Stuff of Place seeks to map a specific landscape of the patterns that constitute Cornwall not only as a place of transition and change but also as a place-beyond-place (Massey Citation2005) and what could be called a place-within-place. Having recently evaluated every item of “stuff” in my life and moved very little of it with me from Canada to Cornwall, I have thought and felt deeply how my stuff, including my dress objects, relates to my feelings of location and dislocation in relation to my place in the world and my own sense of self. We all have a version of this story, whether we are born and raised in Cornwall, moved here from up country or overseas, or come as a visitor in the annual summer temporary migrations. Our collective shrine is designed to shift as the days go on, as garments are moved and rotated, as fabric strips layer and obscure, creating new patterns of political subjectivity and geography to be felt and documented.

The gallery procures donated textiles from Seasalt and the branches that become the tree and offers all the technical support and material fixings needed for install—other than the secondhand mirror we purchase to mimic the water of a spring. It looks somewhat like the cloutie tree in our minds, and yet it does not proceed quite as imagined. We are unable to locate the other planned textiles and our garments, too few to rotate, become permanently fixed to our figurative farm fencing, along with relevant texts for visitors to peruse. We have leaf-shaped tags and Seasalt textile strips for people to write their offerings, but phrased as “wishes” on our interpretive label, the offerings diverge profoundly from our intended themes. Despite this divergence, seeing the shrine at the end of the summer—laden with fabric and miniature objects, articulating shared and idiosyncratic hopes and fears—it feels very much like a conversation we’d hoped to open (). And in so doing, it materializes the forms of collective embodied practice and indeterminate somatic knowledge that have drawn me to immerse myself in curation as an affective methodology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work emerges from time spent listening to and learning from curators, museum professionals and scholars in diverse disciplines. I offer thanks and recognition for their generosity and patience: to Sonnet Stanfill and all the staff and participants on the V&A professional training course in Curating Fashion and Dress, London, February 2018; to ICOM conference on Fashion and Innovation, Utrecht, June 2018; to Emma McClendon, Associate Fashion Curator, Museum at FIT, New York, October 2018 and April 2019; to V&A/Care for the Future’s Contested Heritage workshop, London November 2018; to Daan van Dartel and Tropenmuseum/RCMC Workshop Curating Fashion in and out of Ethnography, Amsterdam, January 2019; to Ninke Bloemberg, Centraal Museum, Utrecht, January 2019; and to Henrietta Boex, Falmouth Art Gallery. I also recognize the curatorial work and associated learning gained from visiting the following fashion exhibitions: Fashioned By Nature (Curator Edwina Ehrman), V&A, London; Balenciaga (Curator Cassie Davies-Strodder), V&A, London; Viktor & Rolf (Curator Thierry-Maxime Loriot), Kunsthal, Rotterdam; Jan Taminiau (Art Director Maarten Spruyt), Centraal Museum, Utrecht; Fabric Africa (Curator Lisa Graves), Bristol Museum and Art Gallery; Pink (Curator Valerie Steele), Museum at FIT, New York.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Delacey Tedesco

DELACEY TEDESCO is a Lecturer in the Department of Politics at the University of Exeter in Cornwall, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research addresses patterns of security and insecurity in contemporary politics and international relations generated by the unstable aporetic boundaries of nature, the city, the subject, and sovereignty. More recent work investigates these problematics through global fashion and everyday dress practices, developing political fashion curation as an innovative methodology for critical social science research.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed, S. 2004. Affective economies. Social Text 79 (22/2):117–39. doi:10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

- Behnke, A., ed. 2016. The international politics of fashion: Being fab in a dangerous world. London: Routledge.

- Bleiker, R. 2009. Aesthetics and world politics. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Breward, C., and D. Gilbert, eds. 2006. Fashion’s world cities. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Closs Stephens, A. 2016. The affective atmospheres of nationalism. Cultural Geographies 23 (2):181–98. doi:10.1177/1474474015569994.

- Crewe, L. 2017. The geographies of fashion. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- De La Haye, A., and J. Clark. 2008. One object: Multiple interpretations. Fashion Theory 2 (12):137–69. doi:10.2752/175174108X298962.

- Derrida, J. 2001. From restricted economy to general economy: A Hegelianism without reserve. In Writing and difference, 317–50. London: Routledge.

- DeSilvey, C. 2017. Curated decay: Heritage beyond saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Dewdney, A., D. Dibosa, and V. Walsh. 2013. Post-critical museology: Theory and practice in the art museum. London and New York: Routledge.

- Entwistle, J. 2000. The fashioned body: Fashion, dress, and modern social theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Entwistle, J. 2009. The aesthetic economy of fashion: Markets and value in clothing and modelling. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Fishel, S. 2017. The microbial state: Global thriving and the body politic. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Frisa, M. L. 2008. The curator’s risk. Fashion Theory 12 (2):171–80. doi:10.2752/175174108X298971.

- Gilbert, D. 2006. From Paris to Shanghai: The changing geographies of fashion’s world cities. In Fashion’s world cities, ed. C. Breward and D. Gilbert, 3–32. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Golding, V., and W. Modest, eds. 2013. Museums and communities: Curators, collections and collaborations. London and New York: Bloomsbury.

- Huysmans, J. 2003. Discussing sovereignty and transnational politics. In Sovereignty in transition, ed. N. Walker, 209–27. London: Hart Publishing.

- Kuldova, T. 2014. Fashion exhibition as a critique of contemporary museum exhibitions: The case of “fashion India: Spectacular capitalism.” Critical Studies in Fashion & Beauty 5 (2):313–36. doi:10.1386/csfb.5.2.313_1.

- Lakoff, G., and M. Johnson. 1980. Conceptual metaphor in everyday language. The Journal of Philosophy 77 (8):453–86. doi:10.2307/2025464.

- Law, J., and A. Mol. 2001. Situating technoscience: An inquiry into spatialities. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 19:609–21. doi:10.1068/d243t.

- Leahy, H. R. 2012. Museum bodies: The politics and practices of visiting and viewing. London and New York: Routledge.

- Leavy, P. 2015. Method meets art: Art-based research practice. 2nd ed. New York and London: The Guildford Press.

- Ling, L. H. M. 2016. “Eastern moon” in “Western waters” reflecting back on the East China Sea. In The international politics of fashion: Being fab in a dangerous world, ed. A. Behnke, 69–96. London: Routledge.

- Lisle, D. 2006. Sublime lessons: Education and ambivalence in war exhibitions. Millennium 34 (3):841–62. doi:10.1177/03058298060340031701.

- Lisle, D., and H. J. Johnson. 2018. Lost in the aftermath. Security Dialogue 50 (1):20–39. doi:10.1177/0967010618762271.

- Luke, T. W. 2002. Museum politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Massey, D. 2005. For space. London: SAGE Publications.

- Melchior, M. R., and B. Svensson, eds. 2014. Fashion and museums: Theory and practice. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Mida, I. 2015. Animating the body in museum exhibitions of fashion and dress. Dress 41 (1):37–51. doi:10.1179/0361211215Z.00000000038.

- Parkins, W., ed. 2002. Introduction: (Ad)dressing citizens. In Fashioning the body politic, 1–17. Oxford and New York: Berg.

- Pecorari, M. 2014. Contemporary fashion history in museums. In Fashion, and museums: Theory and practice, eds. M. R. Melchior and B. Svensson, 46–60. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Pratt, G., and V. Rosner. 2006. Introduction: The global & the intimate. Women’s Studies Quarterly 34 (1/2):13–24.

- Rose, G., and D. P. Tolia-Kelly, eds. 2012. Visuality/materiality: Images, objects and practices. London and New York: Routledge.

- Scaturro, S. 2018. Confronting fashion’s death drive: Conservation, ghost labor and the material turn within fashion curation. In Fashion curating: Critical practice in the museum and beyond, ed. A. Vänskä and H. Clark, 21–38. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Shapiro, M. J. 1985–1986. Metaphor in the philosophy of the social sciences. Cultural Critique 2:191–214. doi:10.2307/1354206.

- Smith, H., and R. T. Dean, eds. 2009. Practice-led research, research-led practice in the creative arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Squire, V. 2015. Reshaping critical geopolitics? The materialist challenge. Review of International Studies 41 (1):139–59. doi:10.1017/S0260210514000102.

- Sylvester, C. 2009. Art/museums: International relations where we least expect it. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, L. 2004. Establishing dress history. Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

- Vänskä, A., and H. Clark, eds. 2018. Fashion curating: Critical practice in the museum and beyond. London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Wilson, E. 2006. Urbane fashion. In Fashion’s world cities, ed. C. Breward and D. Gilbert, 33–42. Oxford and New York: Berg.