Abstract

This paper explores the history and political significance of black horsemen and horsewomen, using the appearance of mounted protesters at the 2020 Black Lives Matter rallies in the US to consider the role of the horse as both an adjunct of authority, in symbol and in material power, and as a partner in forms of protest and resistance. This paper begins with the brute power of the horse, and through its military and policing duties, its role supporting state authority. But we underline the racial framing of “the man on horseback,” using this figure not merely as a metaphor for military authority but as a representation of racialized power and as an adjunct to racial regimes. The significance of this figure is explored through the history of black horse riders and the “threat” that the image of the black rider poses to majority white culture. We examine the political value of placing black horse riders in the position of authority long claimed by white men and celebrated in public statuary and in art. The final section considers the black horsewoman, however, warning against disconnecting the martial model of masculinity from gender privileges as well as racial ones. The paper uses the example of black horsewomanship to argue for a better understanding of the partnership between human and nonhuman. In the performative politics of assembly that we call “political dressage” we suggest a distinctively more-than-human variety of “counter-conduct.”

;本文探讨了黑人男女骑手的历史和政治意义,以美国2020年“黑人的生命也重要”(Black Lives Matter)集会上出现的骑马抗议者为例,探讨了马作为权威的符号象征和物质力量、作为抗议和抵制的伙伴作用。本文从马的蛮力开始,包括它的军事和警务职责,以及它在支持国家权威中的作用。但我们强调,“骑马的人”的种族框架,不仅是军事权威的隐喻,而且是种族化权力的表达和种族政权的附属品。通过黑人骑手的历史、黑人骑手形象对主流白人文化的“威胁”,探讨了这一形象的意义。我们研究了将黑人骑手置于白人长期以来宣称的、在公共雕塑和艺术中得到赞誉的权威的政治价值。然而,本文最后章节考虑了黑人女骑手,警告不要将军事化的男子气概与性别特权、种族特权割离。本文以黑人骑手为例,论证了如何更好地理解人类与非人类之间的伙伴关系。在我们称之为“政治盛装舞步”的表演性集会政治中,我们提出了各种超人类的“反行为”。

Este artículo explora la historia e importancia política de jinetes negros y negras, usando la apariencia de manifestantes montados a caballo en los mítines de Las Vidas Negras Importan del 2020, en Estados Unidos, para considerar el papel del caballo tanto como un adjunto de la autoridad, en poder simbólico y material, así como pareja en las diversas formas de protesta y resistencia. El artículo empieza con el poder bruto del caballo, y a través de sus deberes militares y de policía, con su rol de apoyar la autoridad estatal. Pero nosotros subrayamos el marco racial “del hombre a caballo”, usando esta figura no meramente como metáfora de la autoridad militar sino como representación del poder racializado y como adjunto de regímenes raciales. La importancia de esta figura es explorada a través de la historia de jinetes de caballos negros y de la “amenaza” que la imagen del jinete negro plantea para la cultura de la mayoría blanca. Examinamos el valor político de colocar a los jinetes negros en la posición de autoridad que durante largo tiempo fue reclamada por hombres blancos y celebrada en la estatuaria pública y en las artes. La sección final considera las mujeres negras jinetes, sin embargo, advirtiendo contra la desconexión del modelo marcial de masculinidad desde los privilegios de género lo mismo que los raciales. El artículo usa el ejemplo de la equitación femenina negra en busca de una mejor comprensión de la asociación entre lo humano y lo no humano. En la política performativa de reunión que llamamos “doma de exhibición política” sugerimos una variedad distintivamente más-que-humana de “contra-conducta”.

Horses are storied animals. They bear the narrative weight of millennia of human-equine history, and when ridden the resulting hybrid of human and animal is freighted with an enduring significance. The myth and image of the “centaur” has been frequently appropriated in our collective imaginary, from the most ancient times to the most modern, principally to advance the perspective of a special partnership, so close and intimate that the distinction between species seems to be transcended. But we must also resist the putative harmony of horse and human, knowing that the construction of the horse as a symbol of liberty and freedom is more than matched by the business of dominance and control. Centaur imagery cannot crowd out our awareness of the power of one species over another, nor the power of some human beings and communities over others, accompanied or abetted by this control over animals.

The complex and politically overdetermined figuration of horse and rider is the subject of this paper, which stems from witnessing the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in the USA in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis on 25 May 2020. We offer this paper not as a direct contribution to understanding and eliminating the racial and social injustices that BLM and its sister movements have highlighted, but as a sidelight on one of the most intriguing aspects of the US rallies in the summer of 2020: the presence of black horsemen and women (for media coverage see Allaire Citation2020; Nicholl Citation2020; Thompson-Hernández Citation2020). These protestors included Brianna Noble, pictured with her horse Dapper Dan in Oakland in what is one of the most famous and well-circulated images ().

FIGURE 1 Brianna Noble and Dapper Dan, Oakland, CA, May 29, 2020. Photography by Shira Bezalel, all rights reserved. Reproduced by permission of Shira Bezalel

At the Austin, Texas rally in June 2020, Ilanah Taves was struck by the sight of these riders, parading, halting, or trotting alongside the crowds of protesters brought out onto the streets to support the families of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and the many before them. These riders were immersed in the action of the protests, which began at Huston-Tillotson University (an historically black college) and which culminated at the Texas State Capitol Building. Perhaps the most invigorating moment of the protest came when the crowd of thousands halted at the gates of the state building and, as if staged, one man on horseback galloped through the center of the crowd creating his own pathway. The rhythmic pounding of the horse’s hooves on the concrete pierced the loudest cries for justice and, for just a moment, everything was still, and all eyes were on the cowboy and his horse.

As a horseperson herself, Ilanah was immediately aware of the expertise and training needed to keep these horses under control in these most demanding conditions. What was striking was not just the presence of the horses, but the skill to ride them and the horses’ own comportment, all the things we recognize when we speak of horsemanship, manège, or “dressage.” Power and authority are clearly vital perspectives here, and we remember that Foucault (Citation1977, 136) used “dressage” as a shorthand for the production of docile human bodies, and that this “discipline” is exacted on and from and with nonhuman animals (Hansen Citation2017). The conjoining of human and horse allows for a specific dynamic that raises pointed questions about the microphysics of power. This is true even if this disciplinary power is revalued as training, skillful, mutual, and compassionate, which Haraway (Citation2008, 44; see also Patton Citation2003) has called a “pedagogy of positive bondage.” The connotations of “bondage” are of course profoundly uncomfortable in a racialized context, where power over horses must be interpreted via the history of white power and privilege.

In this paper, we show first that the horse as symbol becomes racialized in a number of significant ways, and weaponized in historical contexts that are at once various and familiar. By virtue of stature alone, we have to accept that the horse rider embodies and establishes a hierarchy. Such a powerful tool to communicate authority will inevitably fall into the hands of those already situated in a position to exercise power over others. In a setting such as the BLM protests, we can hardly be unaware that the default horse rider is both male and white and often uniformed. The dominant whitewashed equestrian imaginary perpetuates the erasure of black horse riding in American popular culture: the skill of the protest riders and the discipline of the horses was far less significant to the local media because the riders were black, as Ilanah immediately noted. But this recognition of the political peculiarities of the black rider led us to reflect on the wider racial politics involved in the human-horse partnership, something that we go on to explore by adding race to the history of “the man on horseback.”

Only by understanding this history, we think, can the counter politics of partnership between horses and black men and women be properly understood, perhaps especially where black women are concerned. Certainly, a “kinship born of mutual subordination” (Bennett Citation2020, 2), is evident in the responses of protestors like Keiara Wade of the Compton Cowboys: “These horses feel whatever we feel, and they are hurting right now because we are hurting right now, too” (Thompson-Hernández Citation2020). But we want to speak too of the exhibition of skill in the partnership of horses and black protestors, and what this means: the ways in which humans and horses are bound together not just in shared suffering but in concerted political action, in the kind of “performative politics of assembly” examined by Judith Butler (Citation2015), among others. Here, we consider the possibility of both horsemanship and horsewomanship as a kind of “counter-conduct,” to adapt the Foucauldian language, and since we place a special emphasis on the gendering of this horse/human partnership, the ungainly term “horsepersonship” is entirely justified. Our narrative arc thus moves from the horse as a symbol of power and a tool of the powerful to the horse’s figuration as an icon and ally of the kind of resistance that BLM represents. We move in conclusion to the significance of manège or “dressage” as a gendered as well as racialized practice, and we suggest the concept of a “political dressage,” taking into account the contribution of horse and rider, and the political culture in which their partnership is placed. We iconize this political equestrianism in the culminating discussion of the involvement of black women protestors and their horses, and Brianna Noble and Dapper Dan in particular.

THE MAN ON HORSEBACK

Let us start with the horse as an extension of state power and, it follows, white supremacy. Here, any discussion of the power of the horse rider can hardly avoid Samuel Finer’s classic work The Man on Horseback: The Role of the Military in Politics (Finer Citation1962). Finer’s essay remains an essential account of the ambiguous, fateful relationship between civil government and the military. It remains a timely reminder that political rule is underwritten by the threat of armed force against both political and civil enemies. Finer’s work has been so influential that the phrase “The Man on Horseback” is a standard shorthand for the military establishment, and it is as resonant as ever in cases of political instability and civil “emergency,” where military intervention is an all too familiar threat. There are good discussions of the military’s place in the postcolonial polity, for instance (see Hashim Citation2015; Meyersson Citation2016), and as the antagonist of civilian supremacy (Danopoulos Citation1992). Finer (Citation1974) himself considered the constitutional and unconstitutional role of the military in the era of decolonization, which of course raises the special significance of race, colonialism, and indigeneity.

Finer is not concerned with the role of the horse as a military technology, however. The word horse hardly appears outside of the title, and most of Finer’s attention is devoted to periods when the military significance of the horse has waned to the point of almost complete insignificance. That should not stop us underlining the horse’s agency as an instrument of war and as an instrument of police, the latter in the very civil society that Finer portrays as vulnerable to military incursions. But the role of the horse in enforcing social order is a lacuna not just in Finer’s work but in subsequent discussion. There is a tendency in the largely admiring literature on the police horse to emphasize the animal’s approachability rather than its more obviously forceful advantages in what is euphemistically called “low intensity conflict” (that is, mobility, surprise, security, and intimidation: see Onoszko Citation1991, 20, cited by De Vries and Swart Citation2012, 419). So the first lesson for us is that we must not erase the actual horse in our recognition that “The man on horseback is the predominant figure of history” (Winn Citation1903). These words come from the American anarchist Ross Winn (a native of Texas himself), and we note that Winn long preempts Finer in his analysis of the capitalist state’s dependence on a force that it only pretends to abjure. There is no idealization of civil society in Winn’s arguments: violence is not imported by the military, in the coups d’état that distinguish places denigrated as “banana republics”; violence, and you hardly have to be an anarchist like Winn to accept this, is a feature even of what Finer somewhat complacently portrayed as “mature” political cultures.

It is true that Ross Winn subordinates discussion of the horse almost as effectively as Finer, but animal studies and animal history has readily revealed the brute power of the horse as the instrument of violence and symbol of authority. This is obvious for the early modern period: the horse has become a central reference for the study of early modern regimes in Europe and further afield. But the obvious danger of this work is that the modern age, including the contemporary world, seems by comparison less “saturated” by the horse, either real or symbolic (see Guest and Mattfeld Citation2019). We can hardly help but frame such discussions with the supposed disappearance of the horse in our times. Ulrich Raulff’s (Citation2017) Farewell to the Horse: The Final Century of Our Relationship is exemplary in this regard. In his fine account, the “centaurian pact” between human and horse is definitively over: the man on horseback has dismounted in favor of the armored car, or even the tank.

The metaphor lives on even if the barrack stables have been cleared, of course: the aura of authority that surrounds the man on horseback is something of an ever present. It is the very image of state sovereignty. Falconet’s sculpture of Peter the Great, Van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I, David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps, Clark Mills’ monumental statue of George Washington: the rider can be repurposed for any and all regimes. This should not lead us to think that we are only dealing in symbolism, however. It is all too easy to neglect the fact that horses continue to be a power in the streets, so that the “man on horseback” has a literal significance even today. The role of police horses, as noted, is strangely neglected even for those who are interested in the horse in the modern city. Clay McShane and Joel Tarr observe, but only in passing, that policemen were among the few individuals who rode horses in cities, and that the horses themselves had to be highly trained: “Mounted police trained their horses to use six gaits, switch leads, angle off runaways, and slow down and push crowds sideways—a training process that could take six months” (McShane and Tarr Citation2007, 41). There is a temptation to see these trained and tractable horses just as tools of “crowd control,” of policing in at most a semi-military sense, neglecting for instance the routine deployment of horses against protestors and others. The army may retreat to the barracks, but the mounted police remain a common enough sight, even in those “mature” polities that pride themselves on democratic accountability.

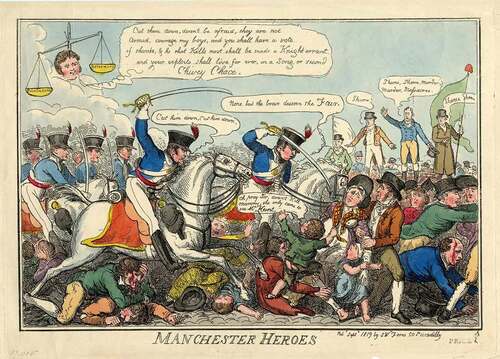

Think here of the mounted militia, the ancestors of the mounted police. The aristocratic heavy cavalry of the middle ages ceded place to the more numerous, more economically accoutred light horseman of the early modern period, a process that Bruce Boehrer (Citation2005) terms the “bourgeoisification of the horse.” But social devaluation is not democratization. The horse remains the premier ally of authority, even if the elites became somewhat more open. And as for the poor, they remain under the hooves of this modern form of sovereign power. Consider the fate of England’s Peterloo protesters in 1819 (): Percy Shelley famously pictures the Manchester yeomanry as Anarchy, sitting astride a white horse, trampling Hope underfoot, a scene of horror:

FIGURE 2 George Cruikshank, Manchester Heroes, 1819. Copyright the Trustees of the British Museum and reproduced under creative commons license

The recent rise of horse history neglects the military/paramilitary significance of the mounted police, and this is true even when we think of colonial as well as class power. Colonial states continued to rely on the cavalry and mounted militias throughout the nineteenth century, and well beyond, even if the flashing sabers were replaced by carbines. In Canada and Australia, for instance, “colonial governments relied upon mounted police forces to facilitate Indigenous people’s subjugation to colonial law and aid the establishment of agricultural and early industrial capitalist economies through land acquisition and settlement” (Nettelbeck and Smandych Citation2010, 357). The horse was fully employed in the dismantling of indigenous sovereignty. In South Africa, to give another example, the mounted military and the mounted police were complementary when it came to pacifying the townships in the late twentieth century (De Vries and Swart Citation2012).

We in the West may feel ourselves at some remove from the brutality of apartheid South Africa, but it was the British who exported the model of mounted police to such colonies. Moreover, whilst the cavalry and the yeomanry may be gone, the weaponized horse has not. We might note with Roth (Citation1998) the separate development of the Texas Rangers and their equivalents elsewhere in the US: key examples of the semi–military irregular or “volunteer” tradition, men whose duties ranged from “Indian fighting” to runaway slave catching to straight police work. Elsewhere, military parades, or the sight of police horses in the streets, are common occurrences, even in polities priding themselves on civil and political rights. As instruments of war horses have been and continue to be significant (Forrest Citation2017, 309–368), and the same conclusion must be reached when we think of internal “pacification.”

And all of the above has a special significance when it comes to questions of race, so much so that the “man on horseback” might be rephrased (with apology) as “The Man on horseback,” nodding to the personification of the police, authority in general, and the system in which black people are victimized. This may seem a stretch, but when put in the context of the history of slavery, it is distressingly easy to justify. Rhys Isaac, for instance, in his celebrated account of eighteenth-century Virginia, specifically draws attention to the view from the back of a horse, the viewpoint of the planter and his fellow “proud men on horseback” being “some three feet higher” (Isaac Citation1982, xxv, 53) than that of the black people and slaves who tilled the fields. In this racialized phenomenology, the lives of black and white people are fundamentally set apart by the height of a horse, even when the animal is not being directly mustered against the downtrodden. In Trevor Burnard’s gloss, “the authority of ‘proud men on horseback’ and the values they espoused were widely accepted as the basis for considerable social order” (Burnard Citation2002, 125).

The racial significance of the ridden horse, positioned above and alongside the slave, has been confirmed in more recent work (Lambert Citation2015, Citation2018). From this perspective, the horse is not merely the most aristocratic of animals, but a fundamental adjunct of authority, whether we are talking of brute force or hegemonic power, and whatever combination of class, caste, or race is concerned. Since we are being specific here, let us simply say that in slave societies, and the Jim Crow regimes that succeeded them, the ridden horse is the symbol of racial subordination. We do not want to reproduce the images here, since the widely shared photographs and videos of his arrest compound the victimization, but the 2019 image of a homeless black man being led by two mounted police officers through the streets of Galveston at the end of a rope is perfectly representative of this aspect of the racial politics of the human-horse bond. And in Galveston, where slavery continued for 2 years after emancipation, this image was bound to evoke the Texas Rangers’ brutal involvement in slave catching. The Houston NAACP president protested in outraged disbelief that this was 2019, not 1819, but we would only add that “the man on horseback” has never lost his racial significance.

THE BLACK MAN ON HORSEBACK

The disappearance of the mounted soldier (occasional ceremonial duties excepted) leaves most of us in the West experiencing the horse in the city as an auxiliary to civilian power, its duties limited to the maintenance of public order. There are plenty of neutral situations where the police horse is indispensable, and not every protestor or rioter or “hooligan” deserves our sympathy just because they are on foot and the police are on horseback. Still, we ignore the sheer mass and force of the horse and its rider at our peril. Here, for instance, is a relatively recent account of the contemporary world, meant to draw attention to the great gulf that separates us from our early modern forebears:

In the modern developed world, the appearance of horses in a peaceful public space (police horses in a town centre, say, or horses with their riders on a hack, stopping for refreshment at a food and drink outlet) typically draws a small crowd. Children approach diffidently to touch and stroke the horses, adults stand back, looking. Horses are unexpected visitors in contemporary everyday life: not quite exotic, but not familiar either. This estrangement between humans and horses has occurred abruptly and relatively recently. (Edwards and Graham Citation2011, 1)

It is unfair on the authors to take them too much to task, but from the perspective of the streets, and not just with recent events in mind, this image is romanticized and depoliticized. There are innumerable instances of popular protest being met with mounted assault. The working classes have clearly borne the brunt of this assault, and even the mounted police unit with the best public relations—Canada’s Mounties—have a rather less media-friendly history of deployment against indigenous peoples, immigrants, labor radicals and striking workers (see for instance Baker Citation1991). In many other countries, such as in the UK, mounted charges against protesters such as the so-called Battle of Orgreave during the Miners’ Strike of 1984 live in the memory as recent instances of Shelley’s “Anarchy.” But special mention should be made of the horse being deployed against black protestors in the US. There are too many examples to give. Even if we were to take just one city, we note that mounted police were deployed on the streets of Harlem in 1935 to quell the “race riots” that followed the police shooting of a black youth. The man who directed the operations was Commissioner Samuel Battle, himself the son of slaves, and honored in 1964 as “the father of all Negroes in the [New York] Police Department.” But that same year of 1964 saw the mounted police charge a restive crowd in Harlem, following the police killing of a Bronx ninth grader, James Powell. The same could be said of disturbances and protests in 1967, and indeed in many other years. Horses have been used time and again against protesting crowds (rather than merely to confront “rioters”), and if more recent confrontations in New York have not had explicit racial significance, black Americans could hardly be blamed for seeing the horse as an instrument of white authority. From these “race riots” through the civil rights era to Black Lives Matter today, the mounted police will likely not register as merely the infrequently seen but largely friendly face of civil authority, the keepers of the peace.

We should quickly emphasize that the men on horseback, be they army, irregular volunteers, police, or others, were never exclusively white. In many colonial states, authorities predominantly relied on nonwhite horsemen. In South Africa, for instance, two-thirds of the Cape Mounted Police established in 1822 were Hottentots (see Roth Citation1998). We are not really concerned here with the history of black cavalrymen in the US (since their formation in 1866, around 20% of post-Civil War cavalrymen were black) or of black mounted police (from at least as early as 1804 in New Orleans: see Rousey Citation1987), save just to note that they were there. Nor are we competent to review black equestrianism in any detail. We note the recovery of the history of the “black cowboy” (Allaire Citation2020; Thompson-Hernández Citation2020) which is a welcome counter narrative to white Western myths; even if the term “cowboy” has racist connotations, it can be and has been reclaimed. We can also reflect on the significance of black Americans in the horse industry before and after emancipation, as skilled wranglers, stable lads, hostlers and grooms, jockeys, trainers, rodeo and stunt riders (see for instance Dallow Citation2019). All this is worthy of note, and there is much historical recovery still to be done. But it is not enough.

Rather than merely including the black man and woman in the history of human-equine partnerships, which is a well-intentioned but politically limited move, we want instead to underline the historical partnership between black Americans and horses, particularly in the context of US slavery and subsequent racial violence. We need to note, for instance, that black mounted policemen became increasingly rare in the era of Jim Crow, and that black jockeys, once prominent, even dominant (Black Past Citationn.d.; Hotaling Citation1999) were shut out from the American version of the Sport of Kings. Moreover, we must straightforwardly recognize that black Americans’ participation in equestrian culture was at best ambivalent where racism was concerned (see Mooney Citation2014). Since they occupied such a privileged position, horses such as thoroughbreds were “especially charged mediators between nature and culture,” whilst the black men who stood alongside them or even sat in the saddle were left “neither fully inside culture nor outside nature” (Dallow Citation2019, 118). Under conditions of slavery and into Reconstruction, the close association of black man and horse arguably reinforced racism as much as it challenged it.

More positively, we should remember that horse racing and horse and carriage rides were a notable part of Juneteenth or Jubilee Day celebrations as far back as the late nineteenth century. Juneteenth seems first to have been celebrated in the very last state to be reached by the Union Army, in Texas, beginning a year after emancipation, on 19 June 1866 (Public Domain Review Citationn.d.), and the ethos of celebration and carnival needs to be tempered by the black community’s awareness of contemporary struggles. Juneteenth was regularly celebrated with horseback parades as well as the familiar floats and marching bands. There are plenty of examples, such as in Austin in 1979, Oakland in 2012, and trail riders have been present at recent celebrations, long before the current Black Lives Matter movement (see Hill Citation2007; Yaeger Citation2019). In those less overtly confrontational times, the black horse rider is unfamiliar (to white audiences) but largely an innocuous sight, covered in mainstream local media in commemorative and celebrative vein. Here, the rhetoric of inclusion and remembrance takes over completely, as with Oakland’s annual Black Cowboy Parade and Festival: “Yeehaw! Black cowboys will ride in Oakland on Saturday” (Hill Citation2007). But such positive and essentially liberal-progressive readings should not blind us to the fact that the presence of horses in black politics as well as in the black experience is not new. Since racial injustice has never escaped black communities, we suggest that these forms of parading might also be thought of a pointedly political paseo: a public presence or parade of black people on and alongside the horses that have been reappropriated from white society. We can think of this as the kind of performative political assembly explored by Judith Butler (Citation2015). This is not straightforward, but we know already that we are not speaking only of human bodies and beings, that humans and animals are caught up in complex relations of vulnerability, dependency and mutual sustenance, and that animals cannot be excluded from the politics of the street and the “right to appear” in public.

One question follows: given the history of black people and horses in the US, why might black equestrians appear not just outlandish, but threatening? We venture to argue that in these sharper and more agonized days, the mere sight of black people on horseback, along with the raised fists and the BLM slogans, takes on different connotations. Here, considered or unconsidered racism likely distorts white vision. Without casting aspersions against unspecified offenders, we have to wonder whether the image of the black horseman engenders white anxiety or perhaps even panic. The 1960s and 1970s Planet of the Apes films, for instance, which are transparently narratives of race and race conflict (Greene Citation1998) trade on the vertiginous image (again, for white society) of apes on horseback. In the 1968 film, this is our introduction to the inversion of species authority, and, in case the message is not clear, the apes on horseback are gorilla stormtroopers whose blackness is emphasized by their clothing and their horses (these horses were apparently dyed black for the production). These gorillas are also engaged in a “human hunt,” evoking runaway slave hunters and great white hunter tropes. They are also amongst the most obviously “racist” or supremacist of the apes, endorsing medical experimentation and making exhibits out of human beings: all of course charges that can be laid at the door of white and settler society. Here, in this highly offensive imagery, what has been called “anthropological anxiety” or more specifically “ape anxiety” (Bernstein Citation2001; Parson Citation2016; Richter Citation2011) is figured as race anxiety, with the white man dethroned and his place taken by “damn, dirty apes.” As Susan McHugh has argued, whites become animalized, but black people are not humanized.

The politics of “animal-racial masking” (McHugh Citation2000, 42) essayed in the Planet of the Apes films works not simply through the ape-human (and ape-ape) hierarchies, however. The horse is conscripted in the imagination of racial and species difference. Horses are after all “the first visible agents of ape culture, consistently framed by guns” (McHugh Citation2000, 59), and “the gorillas’ black leather riding boots and padded vests reflect their dangerous work of using and subduing animals, but also visually identify them with lesser animals, namely the black horses they ride, within ape culture” (McHugh Citation2000, 57). The horse thus acts to reinforce the apes’ less-than-human status, and this all transfers—in the civil rights era, remember—to revolutionary blackness. The films, and we would take in the recent versions, do open up a space for more critical and sympathetic responses, since they narrate the dissolution of white American male authority, but the ham-fistedly progressive messaging is hampered by the affective appeal, the sheer thrill and horror (to white audiences) of apes-horses-guns. As Majid Yar summarizes, the treatment of race relations in the various Planet of the Apes films “articulates, in allegorical form, both white liberal support for an integrationist project of ethnic inclusion and that same constituency’s anxieties about a militant and revolutionary Black Power movement that wishes to fundamentally subvert the existing system of racialized privilege” (Yar Citation2015, 52).

Rather than relying on popular culture and its “public myths,” we might turn in relief to black people’s responses to the mythic authority of the white horseman. Easily most prominent is Kehinde Wiley’s recent monumental sculpture, Rumors of War, which was exhibited in Times Square, New York, before taking up its permanent residence in Richmond, Virginia (). Rumors of War is a colossal 29-foot high bronze sculpture of a young black man, in contemporary dress (hoodie, high-tops, headphones), astride a horse portrayed in classic passant or walking pose. Wiley based the sculpture and its scale on the Richmond monument to Colonel J. E. B. Stuart, a hero to the Confederacy, and he has said that he wants his contribution to Monument Row to speak not just to the neighboring monuments, but also to the people looking up at those statues, particularly the young black men and women who view them from below.

FIGURE 3 Kehinde Wiley, Rumors of War, 2019, Virginia Museum of Fine Art, Richmond, VA. Reproduced by permission of the Virginia Museum of Fine Art

There are degrees and layers of “anachronism” here, and we do not simply mean the contemporary dress of the black male rider. Recognizing the “diminishing interrelational dependence that exists between humans and horses” (Gare Citation2019, 63), any depiction of a human-equine partnership invokes the antiquity of that history, and also its seeming redundancy. In the late twentieth century, when the horse has become an exceptional subject in art, rather than the norm that it once was, any painting or sculpture of a man on horseback seems “out of time,” just as the black man on horseback seems culturally “out of place.” That, presumably, is the point, or part of it. The mounted black man as a figure of authority, pride, and power appears to arrive late to the party, to the business of pomp and parading, precisely because he never received the invitation. It is not simply a matter of making up for lost time, however, or of filling up a diversity quota. Wiley’s works are “about time” for rather different reasons, given that Wiley’s canvas is the whiteness of history itself. Wiley’s earlier painting, Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2006), one of a series also entitled Rumors of War, repurposes the compromised past, in this case Jacques-Louis David, to this effect: reproducing the rearing horse, but substituting for the Emperor a black man in fatigues, Timberlands, and headband:

The rider, clothed in army–issue camouflage, is, I believe, an unmistakably serious nod to the many, many, young men of color who are often in the front lines of battle. There’s nary a hint of a general’s starched uniform, only the gold mantle that every soldier deserves to wear. Moreover, the headband wrapped around the forehead and tied in back invokes other battles, other peoples, their nobility illustrated in posture, and proud strong facial features, in response to centuries of belittling images. (Pratt Citation2020)

Here, as with the other paintings and the great sculpture that culminates the project, the iconography of black men and horses is not designed simply as a frisson for predominantly white audiences in the context of restive blackness. Instead, Wiley revisits the mythos of the man on horseback, drawing attention to its unearned or stolen cultural authority, and even satirizing it, whilst at the same time keying into and claiming the kind of nobility, dignity and power routinely refused to black people. “Old paintings use the perspective of a horseman: of a man looking down,” remarks Shklovsky (Citation2017, 269), and Wiley emphasizes just what black people gain from looking up to the black man on horseback. It is also potentially a threat, though, to white audiences not used to being looked down upon. Here, Wiley’s work is inevitably reminiscent of the powerful portraits of Toussaint L’Ouverture on horseback (). These images of the coachman and horse handler turned Haitian revolutionary leader are arresting because of the unsettling unfamiliarity of black men and women in this position: “Those few contemporary instances where people of African descent are shown riding are striking because they contest the dominant association between whiteness and equestrianism” (Lambert Citation2015, 627–628).

THE BLACK WOMAN ON HORSEBACK

The history of the horse is in part an extension of white supremacy, then, though horses have become partners or perhaps even allies for black activism and its prefigurative politics. The horse is a delivery vehicle for countercultural commentary, and there is certainly no denying the monumental magnificence of Wiley’s work. Placed as it is in conversation with the conventions of equestrian statuary, Rumors of War makes a stark and unapologetic claim to our attention. But we must approach the cultural consumption of Wiley’s work with a degree of caution. Rumors of War has been warmly welcomed by the art establishment as a necessary counterbalancing: “By replacing European aristocrats with black subjects, Wiley points out the absence of African Americans from such historical narratives” (VFMA Citation2016). This argument is right, but in placing the injustice to black people in history and culture, with Wiley’s intervention a kind of revisionism or reset, we are taken out of the history of the present and the political statement that Rumors of War makes.

Moreover, we need to follow Wiley’s lead in critiquing the conventions of gender as well as of racial privilege: not hastily to haul black men down from the plinths and pedestals, lately occupied, but rather to revisit the martial models of masculinity we have inherited from colonial history and white privilege. Wiley has quite deliberately emphasized the fact that the person on horseback is not just black, but a black man. He has said that when he casts from models on the streets, he looks for “alpha male behavior and sensibility” (Kehinde Wiley Studios Citationn.d.), though he is alert to how this may conflict with their presence. In a complementary project, Wiley has trained his focus on women in recent work, as “a means to broaden the conversation”: these paintings, “An Economy of Grace,” feature African-American women, cast from the streets of New York City, in poses and fashions based on the historical portraiture of women. But their enfolding floral and botanical backgrounds and foregrounds, with the emphasis on couture, arguably tends to reinforce the subordinate position of women in Western art and society, even as these women’s presence subverts it. In short, our attention is drawn back toward the powerfully exclusive codes of gender, rather than only a revisionist recovery of the black presence, this plea for “a more complete and inclusive American story” (Horsetalk Citation2019).

In this regard, the Rumors of War sculpture does something rather different from and rather less than the earlier paintings, which are certainly more explicit about masculinity and its history. Being very critical, the force of Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps and its companion paintings has been lost, even as the imagery has been scaled up and monumentalized, its public presence made impossible to ignore. Most importantly, Wiley’s commentary on military masculinity, the sly send-up of Napoleon and the entire white posse of kings and generals, now has rather a secondary place, as the Second Gulf War context of the paintings has given way to Black Lives Matter, the conflict in Iraq replaced with conflict in the streets, the exploitation of soldiers with civilian deaths at the hands of police officers. The aestheticization of power and masculinity, and the compromise that art makes with the state in the exercise of violence: these are themes that are now a little too easy to ignore. So we might bring that commentary back to bear, particularly where the argument for “counterbalancing” is at stake. Is it really enough to put black men in the saddle, as placeholders for all black people?

We have so far deferred the question of gender, but at the risk of stating the obvious the “man on horseback” is by definition and default a masculine figure (even if a select few female monarchs get to ride in review of the troops). The black woman is even further from the seat of power, and whilst horses and horse culture have become more feminized in Western culture with the decline of the cavalry, black women were hardly welcomed to the gymkhanas. The association of black people and animals/animality is a critical commonplace, but it is worth stressing the special vulnerability and victimization of black women. Here, again with apologies for the imagery, the black woman has been portrayed as more mule than mare: “Under capitalist class relations, animals can be worked, sold, killed, and consumed, all for profit. As ‘mules,’ African–American women become susceptible to such treatment” (Collins Citation2009, 150). Patricia Hill Collins references Zora Neal Thurston’s 1937 characterization of the black woman as “de mule uh de world,” no more than living machines, part of the scenery (Collins Citation2009, 51; see also Bennett Citation2020, 114–139), and so about as far from the aristocrats of the horse world as you can get.

Once again, however, there are notable exceptions. Training of horses was not entirely closed off to women, who could perform equally as well as men in manège or dressage, the equestrian ballet that performs and exhibits both the art of mastery and the partnership between human and animal. This was still, naturally, an elite pursuit. But this is why the spectacle of black horsewomen is such a draw—women like the écuyères or amazones who performed in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century circuses and theaters (see Weil Citation2019). If we turn away from the US, the black horsewoman who took the name Selika Lazevski (see Forrest Citation2018) provides a striking figure of contemplation. Lazevski performed haute école dressage in the French circus during the Belle Epoque, and though we know very little about her, she stares out at us in the studio photographs taken in 1891, as part of a series on the presence of black people in fin-de-siècle France.

We are a long way from America, and we might wonder what a turn-of-the-century French amazone has to say about black men and women on horseback in contemporary protests. Does she have anything to provide save novelty value, a touch of noir for an audience of predominantly white men? Kari Weil (Citation2019) has underlined the ways in which such circus or theater acts are eroticized performances, where mastery of the animal is perhaps secondary to the display of flesh and femininity, and she notes the racial connotations of the education/training of horse and rider. It is certainly hard to avoid the racializing and sexualizing gaze. Even the skilled horsewoman is a hybrid of masculine and feminine, as well as human and horse, and Selika Lazevski’s racial significance only complicates her position. This “messy co-becoming” (Mattfeld Citation2017, 10) is capable of variant readings, however, depending on position: as Susanna Forrest points out, even the borrowed name, an exotic introduced into nineteenth-century European popular culture, connotes dignity as well as titillation:

To a black American woman born in a time of slavery, Selika meant a queen, a black woman ennobled; to French sportsmen, Escoffier, and authors of cheap novels seeking shorthand, Selika was darkness, a touch of the exotic, a meeting of animal and female. (Forrest Citation2018)

We might still take the black female equestrian as an exemplar, then, since putting the emphasis on black horsewomanship feels like a necessary riposte in a culture where the cowboy remains the model of manhood. The Renaissance scholar Bruce Boehrer reminds us that horsemanship was deemed one of the essential attributes of a gentleman, and the ability of the rider to command an animal weighing up to 1000 kg was a measure of his status as a man (Boehrer Citation2005). But for a woman to achieve the same mastery was something that commanded respect. The manège separated those born to rule from the plebeian, and the education of horse and rider essentially performed the right relations between sovereign and subject (Mattfeld Citation2017, 10), but these arguments could extend to people otherwise socially and politically marginalized. Selika Lazevski’s example shows that the associations with gentility and the acknowledgment of skill that came with being able to manage a horse, were in principle available not just to black people but to black women in particular. Black women like Lazevski could demonstrate their mastery at the same time as calling into question the boundaries between human and animal, between men and women, between black and white. Monica Mattfeld has argued that for men “a partnership with a horse was essential to their understanding of the world and their place in it” (Mattfeld Citation2017, 2), but this is no less true for women like Lazevski, performing their gender just as men performed theirs, and influencing public and political discourse as they did so.

With this fragmentary and partial history in mind, how might we view someone like Brianna Noble, the horsewoman who rode to the protests in Oakland ()? Astride her horse Dapper Dan, Noble provided an unmissable photo opportunity, something of which she was well aware. “It wasn’t a very planned thing,” Noble told the Guardian: “I was just pissed, sitting at home and seeing the video of George Floyd. I felt helpless and thought to myself: ‘I’m just another protester if I go down there alone, but no one can ignore a black woman sitting on top of a horse.” Noble stated that she was fully aware of the media’s interest in framing protest as “riot,” focussing on the destruction and looting carried out by a few, rather than the peaceful protest of the many (we might note by contrast the coverage in the UK press of PC Nicky Vernon, who suffered a collapsed lung and broken collarbone when her police horse bolted during the London disturbances). But for Brianna Noble this was an opportunity to reset the standard narrative of policing and protest:

I know that what makes headlines is breaking windows and people smashing things … So I thought: “Let’s go out and give the media something to look at that is positive and change the narrative.”

No one can doubt that she succeeded, on that May day. But Noble’s wider ambitions have been to “change the narrative” about equestrianism, too easily seen as exclusive of all but the rich white elite, by providing opportunities for individuals and communities not typically allowed into equestrian culture and the benefits of working with horses. And Noble is clearly centrally concerned with the welfare of horses too. Noble trains feral and wild horses (Bravo Citation2020; Crawford Citation2020; Rodriguez Citation2020), but she also works with rescued horses, one of whom is the horse that she rode to the BLM rally: the horse Dapper Dan is just as central to this narrative. In this sense, the disenfranchised and precarious “bodies in alliance” (Butler Citation2015) that perform political protest by their presence in the streets can be animal as well as human, acting in concert across the species boundary and the history that divides black people and beasts. Noble is an exemplary figure for us because she has accomplished this politics with her horse Dapper Dan. It is their behavior as a partnership that provides the most resonant story here: disciplined and dignified, Noble and Dapper Dan have participated in a kind of political theater:

I get horses that are generally older. They’ve kind of fallen through the cracks. I do feral horses, I do wild horses, horses that have never been touched, and I train them. So we go out, we do parades, we go do different trail rides. Dapper Dan is a horse that I picked up to do just that with. I picked him up for $500, which is really, really cheap because he was a very difficult-to-handle animal. Then I got him and I was like, what did I get myself into? He was just so awful—and I cried. He was a very, very hard-to-handle horse. I never in my wildest dreams imagined that he would turn into the horse that he is today. He went from just kind of a horse that I got stuck with to, you know, really showing his true colors. And now he’s my partner that has my back. (Rodriguez Citation2020)

This is political theater, for sure, but we prefer to think of it as a form of political assembly that requires patient training, loving care, and consummate skill, on the part of horse and rider. We would like in fact to term this a political dressage, honoring the contribution of both species, over and above the ability to command obedience. Manège or dressage is a performance that requires more than just mastery, the power over animals and their disciplined bodies. All equestrianism requires this kind of partnership, the co-training of humans and animals, but the events of summer 2020 demonstrate that this partnership is exemplary in the politics of racial and social justice that BLM exemplifies. We might even say that Noble has decolonized dressage, because she has taken the art of horsemanship, which has been the property of the cultivated and colonial elite for centuries, and made it inclusive in ways that go beyond putting black people in the saddle, important as that is. She and other black equestrians have changed the narrative about black protest but also begun to reimagine the place of the horse in political struggles.

CONCLUSIONS

We do not want to skate over the human domination of the animal that is at the heart of dressage: horses are trained, typically with varying degrees of force and coercion, to withstand, for instance, the bewildering condition of being in a human crowd. Mastery of the horse, through the whip, the bridle and the bit, used coercively or in paternalistic fashion, is also an obvious analogue for the subjection of the slave and the racially abjected. Corinne Hansen has argued in this regard that horses are subject to “a relentlessly colonial imagination in which they figure in our narratives as willing partners in disciplinary practices” (Hansen Citation2017, 156). It is also a training of the human being, the internalized policing of the self that constitutes civility and politeness. Nor do we want to valorize the dignity and discipline of such polite and peaceful protest as a kind of reproach to other forms of resistance. Ross Winn, in 1903, argued that peaceful protest is never enough, and argued the necessity of a revolutionary man on horseback:

If you had a fellow in a box and you were sitting comfortably on the cover, you would naturally commend him for keeping quiet. The political, financial and priestly parasites of our blessed social order have the rest of humanity in a box. They are comfortable seated on the lid. They esteem the non-resistants underneath very highly. If everybody in the box were non-resistants, or even passive resistants, all would be lovely for the sitters on the box cover. Nothing would so much disturb them as the presence in the box of a man on horseback. (Winn Citation1903)

But if “the man on horseback will put a final period to the American republic” (Winn Citation1903), some of us at least would hope that this does not mean a return to cavalry charges, literally or metaphorically. We would not welcome the notion of the horse as simply a tool of revolution, another use for the living machine that the animal represents. What Noble and her fellow mounted protestors offer is something else, something closer to the kind of “counter-conduct” that Foucault offers as a form of resistance to the more sinister implications of disciplinary power (see Lorenzini Citation2016). Working with horses that may themselves have been “rescued,” Noble offers a pointed reclaiming of “horsemanship” from the powers that be. If dressage is defined as “making or setting straight” (Hansen Citation2017, 141), then we might imagine that the partnership exhibited here between human and horse, the control and discipline they display in the face of unimaginable provocation, is an object lesson to the rest of us. If “the study of counter-conduct is itself an intellectual and ethical practice of subject formation, and is crucial to the different selves we seek to become (Odysseos, Death, and Malmvig Citation2016, 156), we might extend this to the relationships between humans and other species, so that the training of humans and nonhumans might just become an example of a more hopeful politics.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Philip Howell

PHILIP HOWELL is Reader in Historical Geography, Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His research interests include the historical geography of companion animals and the contemporary politics of animal-human relations.

Ilanah Taves

ILANAH TAVES is a doctoral student in the Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research focuses on human responses to coyote adaptation in parts of the United States, and the human-wildlife interface in contemporary cities more generally.

REFERENCES

- Allaire, C. 2020. “We’ve been here all along, doing it with style”: The lesser-known history of the Black cowboy. Vogue, June 5. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://www.vogue.com/article/bacl-cowboy-protest.

- Baker, W. M. 1991. The miners and the mounties: The royal North West mounted police and the 1906 Lethbridge strike. Labour/Le Travail 27:55–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/25130245.

- Bennett, J. 2020. Being property once myself: Blackness and the end of man. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bernstein, S. D. 2001. Ape anxiety: Sensation fiction, evolution and the genre question. Journal of Victorian Culture 6:250–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/jvc.2001.6.2.250.

- Black Past. n.d. The sport of kings and a select few African Americans. Black Past. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.blackpast.org/blog/the-sport-of-kings-and-a-select-few-african-americans/.

- Boehrer, B. T. 2005. Shakespeare and the social devaluation of the horse. In The culture of the horse: Status, discipline, and identity in the early modern world, ed. K. Raber and T. J. Tucker, 91–111. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bravo, T. 2020. The woman who rode her horse through an Oakland protest wants to see more people of color in a white world. San Francisco Chronicle, June 5. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/The-woman-who-rode-her-horse-through-an-Oakland-15318709.php.

- Burnard, T. 2002. Creole gentlemen: The Maryland elite, 1691–1776. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 2015. Notes toward a performative politics of assembly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Collins, P. H. 2009. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Crawford, I. 2020. Who are the voices at the protests? The people behind the mics, masks, and signs. Oakland Voices, June 19. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://oaklandvoices.us/2020/06/19/who-are-the-voices-at-the-protests-the-people-behind-the-mics-masks-and-signs/.

- Dallow, J. 2019. Narratives of race and racehorses in the art of Edward Troye. In Equestrian cultures: Horses, human society, and the discourse of modernity, ed. K. Guest and M. Mattfel, 110–27. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Danopoulos, C. P. 1992. Farewell to the man on horseback: Intervention and civilian supremacy in modern Greece. In From military to civilian role, ed. C. P. Danopoulos, 38–63. London: Routledge.

- De Vries, J. J. P., and S. Swart. 2012. The South African defence force and horse mounted infantry operations, 1974–1985. Scientia Militaria 40:398–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.5787/40-3-1028.

- Edwards, P., and E. Graham. 2011. Introduction: The horse as cultural icon. In The horse as cultural icon: The real and the symbolic horse in the early modern world, ed. P. Edwards and E. Graham, 1–33. Leiden: Brill.

- Finer, S. E. 1962. The man on horseback: The role of the military in politics. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

- Finer, S. E. 1974. The man on horseback– 1974. Armed Forces and Society 1:5–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X7400100102.

- Forrest, S. 2017. The age of the horse: An equine journey through human history. London: Atlantic Books.

- Forrest, S. 2018. Selika: Mystery of the Belle Epoque. The Paris Review, February 9. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/02/09/selika-lost-mystery-belle-epoque/.

- Foucault, M. 1977. Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. Trans. A. Sheridan. New York, NY: Random House.

- Gare, R. 2019. The aura of dignity: On connection and trust in the photographs of Charlotte Dumas. In Equestrian cultures: Horses, human society, and the discourse of modernity, ed. K. Guest and M. Mattfeld, 54–70. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Greene, E. 1998. “Planet of the Apes” as American myth: Race, politics, and popular culture. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

- Guest, K., and M. Mattfeld, Eds. 2019. Equestrian cultures: Horses, human society, and the discourse of modernity. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Hansen, N. C. 2017. Dressage: Training the equine body. In Foucault and animals, ed. M. Chrulew and D. J. Wadiwel, 132–60. Leiden: Brill.

- Haraway, D. 2008. When species meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hashim, A. S. 2015. “The man on horseback”: The role of the military in the Arab revolutions and in their aftermaths, 2011–2015. Middle East Perspectives, October 20. doi:https://doi.org/10.23976/PERS.2015005.

- Hill, A. 2007. Yeehaw! Black cowboys will ride in Oakland on Saturday. East Bay Times, October 5. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2007/10/05/yeehaw-black-cowboys-will-ride-in-oakland-on-saturday/.

- Horsetalk. 2019. Huge equestrian sculpture an “important national conversation.” Horsetalk, October 1. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.horsetalk.co.nz/2019/10/01/equestrian-sculpture-important-national-conversation/.

- Hotaling, E. 1999. The great Black jockeys: The lives and times of the men who dominated America’s first national sport. New York, NY: Prima.

- Isaac, R. 1982. The transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Kehinde Wiley Studios. n.d. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://kehindewiley.com.

- Lambert, D. 2015. Master–horse–slave: Mobility, race and power in the British West Indies, c.1780–1838. Slavery & Abolition 36:618–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0144039X.2015.1025487.

- Lambert, D. 2018. Runaways and strays: Rethinking (non-)human agency in Caribbean slave societies. In Historical animal geographies, ed. S. E. Wilcox and S. Rutherford, 185–98. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lorenzini, D. 2016. From counter-conduct to critical attitude: Michel Foucault and the art of not being governed quite so much. Foucault Studies 21:7–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.22439/fs.v0i0.5011.

- Mattfeld, M. 2017. Becoming centaur: Eighteenth-century masculinity and English horsemanship. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press.

- McHugh, S. B. 2000. Horses in blackface: Visualizing race as species difference in “Planet of the Apes”. South Atlantic Review 65:40–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3201811.

- McShane, C., and J. A. Tarr. 2007. The horse in the city: Living machines in the nineteenth century. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Meyersson, E. 2016. Political man on horseback: Coups and development. SITE, April 5. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.hhs.se/contentassets/5f04e6ceade84bf882ec6bf118022f7c/meyersson_coups_development.pdf.

- Mooney, K. C. 2014. Race horse men: How slavery and freedom were made at the racetrack. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Nettelbeck, A., and R. Smandych. 2010. Policing indigenous peoples on two colonial frontiers: Australia’s mounted police and Canada’s North-West Mounted police. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 43:356–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1375/acri.43.2.356.

- Nicholl, A. 2020. Some Black Lives Matter protesters have been riding horses to protests. Lil Nas X gave one of them props on Twitter. Insider, June 5. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.insider.com/protesters-ride-horses-black-lives-matter-protest-lil-nas-x-2020-6.

- Odysseos, L., C. Death, and H. Malmvig. 2016. Interrogating Michel Foucault’s counter-conduct: Theorising the subjects and practices of resistance in global politics. Global Society 30:151–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2016.1144568.

- Onoszko, P. B. G. 1991. Horse-mounted troops in low intensity conflict. Carlisle Barracks, PA: US Army War College.

- Parson, S. 2016. Ape anxiety: Intelligence, human supremacy, and Rise and Dawn of the Planet of the Apes. In Screening the nonhuman: Representations of animal others in the media, ed. A. E. George and J. L. Schatz, 91–101. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Patton, P. 2003. Language, power, and the training of horses. In Zoontologies: The question of the animal, ed. C. Wolfe, 83–99. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Pratt, A. B. 2020. Black men on horseback. Arteidolia, May. Accessed June 25, 2020. http://www.arteidolia.com/black-men-on-horseback-paul-beatty-and-kehinde-wiley-take-history-for-a-wild-ride/.

- Public Domain Review. n.d. Early photographs of Juneteenth celebrations. Public Domain Review. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/juneteenth-photographs.

- Raulff, U. 2017. Farewell to the horse: The final century of our relationship. London: Penguin.

- Richter, V. 2011. Literature after Darwin: Human beasts in Western fiction, 1859-1939. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rodriguez, J. F. 2020. Oakland’s protest rider on why she took to horseback for George Floyd. KQED, June 2. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.kqed.org/news/11822227/oaklands-protest-rider-on-why-she-took-to-horseback-for-george-floyd.

- Roth, M. 1998. Mounted police forces: A comparative history. Policing: An International Journal 21:707–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13639519810241700.

- Rousey, D. C. 1987. Black police in New Orleans during reconstruction. The Historian 49:223–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6563.1987.tb01914.x.

- Shklovsky, V. 2017. Viktor Shklovsky: A Reader. Trans. by Alexandra Berlina. London: Bloomsbury.

- Thompson-Hernández, W. 2020. Evoking history, Black cowboys take to the streets. New York Times, June 9. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/09/us/black-cowboys-protests-compton.html.

- VFMA. 2016. Kehinde Wiley: A New Republic. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts press release, April 26. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.vmfa.museum/pressroom/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/04/04-25-16-Final-Wiley.pdf.

- Weil, K. 2019. Circus studs and equestrian sports in turn-of-the-century France. In Equestrian cultures: Horses, human society, and the discourse of modernity, ed. K. Guest and M. Mattfeld, 179–200. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Winn, R. 1903. The man on horseback. Winn’s Firebrand II, December 7. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ross-winn-the-man-on-horseback.pdf.

- Yaeger, L. 2019. Taking it to the streets: Celebrating Juneteenth in Austin, Texas. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.vogue.com/article/celebrating-juneteenth-in-austin-texas.

- Yar, M. 2015. Dangerous others: “Race” and crime after the apocalypse. In Crime and the imaginary of disaster: Post-apocalyptic fictions and the crisis of social order, ed. M. Yar, 40–56. London: Palgrave Pivot.