Abstract

This article attends to how contemporary artists Otobong Nkanga and Libita Sibungu work with mineral residues to locate and reimagine Namibian mining geographies among the material durations of colonialism and racial capitalism. Drawing on Black geographies, postcolonial and performance studies, I suggest that Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s respective methods of presencing uneven accumulations and embodied and geological temporalities constitute residual repertoires. From Nkanga’s work at the Green Hill in Tsumeb, to Sibungu’s traversal of diasporic mining geographies between Namibia and the UK, both artists trace mineral circulations through visual, sonic, and performance elements, finding ways to render forces of dispossession, genocide, struggle, and their afterlives (partially) perceptible. This work questions and repurposes institutionalized forms of representation whose visual and archival modes contribute to ongoing corporeal and material extraction. Critically intervening in and seeking to transform extractive geo-aesthetics, Nkanga and Sibungu generate speculative repertoires for other possible futures of mineral proximity.

Chinese

本文关注当代艺术家Otobong Nkanga和Libita Sibungu如何利用矿物残留物, 寻找并重新设想殖民主义和种族资本主义物质时代的纳米比亚采矿地理。基于黑人地理、后殖民和表演的研究, 我认为, Nkanga和Sibungu采用的对不均匀堆积和具身化地质时间性的自然流现方法, 构成了“残留曲目”。Nkanga在Tsumeb的Green Hill作品和Sibungu对纳米比亚到英国的采矿地理的探访, 通过视觉、声音和表演元素来追溯矿物循环, (部分)感知了剥削、种族灭绝、斗争及其延续。基于固有形式的表达, 其视觉和记录模式有助于对肉体和矿物的持续开采。本文质疑并改变了表达的这些固有形式。Nkanga和Sibungu对采矿地理美学进行批判式干预和探索, 构建了与矿物的未来关系的尝试性曲目。

Spanish

Este artículo versa sobre el modo como los artistas contemporáneos Otobong Nkanga y Libita Sibungu trabajan con residuos minerales para ubicar y reimaginar las geografías mineras de Namibia, entre las duraciones materiales del colonialismo y del capitalismo racial. Basándome en las geografías negras y en los estudios poscoloniales y de performance, sugiero que los respectivos métodos de Nkanga y Sibungu para presentar las acumulaciones desiguales, y las temporalidades geológicas encarnadas, constituyen repertorios residuales. Del trabajo de Nkanga en el Green Hill de Tsumeb, hasta el recorrido de las geografías mineras diaspóricas de Sibungu, entre Namibia y el Reino Unido, ambos artistas rastrean las circulaciones de minerales a través de elementos visuales, sonoros y performativos, descubriendo formas de hacer perceptibles (de modo parcial) las fuerzas de la desposesión, el genocidio, la lucha y sus secuelas. Este trabajo cuestiona y reformula formas institucionalizadas de representación cuyos modos visuales y de archivo contribuyen a la extracción material y corporal en curso. Interviniendo críticamente en la geoestética extractiva, buscando transformarla, Nkanga y Sibungu generan repertorios especulativos para otros futuros posibles de la proximidad mineral.

INTRODUCTION

In the spring of 2015, the artist Otobong Nkanga followed an old railway route from Swakopmund, a city on the Atlantic coast of Namibia, to Tsumeb, a town in the north of the country. In the late nineteenth century, European explorers and prospectors discovered the “Green Hill” in Tsumeb, named after its remarkably high range and concentration of minerals, in particular the oxidized copper that gave the ground its green tint. In 1900, during colonial rule in what was then German South West Africa, the Otavi Mining and Railway Company (Otavi Minen- und Eisenbahn-Gesellschaft/OMEG) started mining the Green Hill. Between 1903 and 1906, the company built a 350-mile railway to transport the extracted minerals and ore. During that time, the indigenous Ovaherero people rose up against German colonial forces, who responded with genocidal violence. The railway was built in part by Ovaherero people who were being held in concentration camps and forced to work on German infrastructural projects (Steinmetz Citation2007, 206). Reaching Tsumeb over a century later along the same railway, Nkanga found abandoned buildings, miners’ houses, and a hole mined to exhaustion where the Green Hill had been.

This article considers how Nkanga (b. 1974, Nigeria) and another contemporary artist, Libita Sibungu (b. 1987, UK), attend to the relationship between material residues of extraction and shifting colonial dynamics in their work concerning mining geographies in Nambia and beyond. I explore how these artists bring forms of residue and debris to the surface of their respective work as ways of interrogating and reimagining the relationship between geopolitics and aesthetics in sites of extraction shaped by colonialism and racial capitalism. I argue that Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s artistic practices—considered individually and in dialogue—recite and re-site the (post)colonial detritus of Namibian mining geographies in ways that presence their uneven material accumulations and multiple embodied and geological temporalities. I theorize these practices as residual repertoire, drawing together approaches from Black, (post)colonial and performance studies with close analysis of and situated responses to Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s work.

The first section of the article elaborates the notion of residual repertoire in the context of Black geographies and geo-aesthetics, bringing into dialogue methods and concepts put forward by Katherine McKittrick, Ann Laura Stoler, and Diana Taylor. I suggest that residual repertoire contributes to a geo-aesthetic vocabulary attentive to the spatio-temporal dynamics and bodily performances of mineral extraction materializing a “racialized optic razed on the earth” (Yusoff Citation2018, 14). Residual repertoire brings attention to the ways that Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s work exposes and seeks to intervene in feedback loops between material extraction and aesthetic modalities that repeatedly render (certain) spaces and bodies exhaustible. The middle section expands on these ideas through analysis of a series of Nkanga’s works based on her research at the Green Hill, including the installation Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine (Kadist, Paris, 2015c) and the tapestry The Weight of Scars (2015e). I attend to how Nkanga develops a shifting repertoire of visual motifs and embodied practices to trace the Green Hill’s geologic formations and colonial and extractive entanglements across multiple spatio-temporal scales. Importantly, her work also facilitates critical reflection on visual modes institutionalized through (post)colonial state archives and the (European) gallery space, as sites differentially implicated in extractive dynamics of knowledge and aesthetic production.

The latter part of the article brings Nkanga’s work into dialogue with Sibungu’s installation Quantum Ghost (Gasworks, London, 2019). Quantum Ghost combines visual, sonic, and performance elements to re-site diasporic remnants from Sibungu’s familial history in the geopolitics of extraction and anticolonial struggle in Namibia. Although Sibungu’s work is less widely known than Nkanga’s, I suggest that her residual repertoires practise geo-aesthetics that fold geological and ancestral temporalities into speculative and material forms of memory and corporeal transformation. In this context, I trace the complex potentials of situated, embodied response to Sibungu’s visual and sound work. Finally, I consider the closing performance of Quantum Ghost alongside Nkanga’s live performance work Diaoptasia (Tate, London, 2015), attending to the possibilities of mineral intimacy the artists generate from and beyond the fractures of racialized extraction.

RESIDUAL REPERTOIRE

The notion of residual repertoire I elaborate here seeks to contribute to understandings of the relationship between aesthetics, geographies of extraction, and systems of racial capitalism, and efforts to facilitate and attune to potentially disruptive political and aesthetic materializations across more-than-human bodies and interactions (Brigstocke and Gassner Citation2021; Last Citation2017). As a geo-aesthetic approach, residual repertoire draws together concepts and methods from Black geographies, (post)colonial studies, and performance studies, while also responding to the specific theoretical and methodological prompts of Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s art.

Foundational work in Black geography by Clyde Woods and Katherine McKittrick articulates the theoretical capacities of Black aesthetic and spatial practices emergent from conditions of racialized and gendered dispossession and violence (McKittrick Citation2006, Citation2021; McKittrick and Woods Citation2007; Woods Citation1998). Such practices, McKittrick argues, offer materially and historically situated critiques of the geographical inscriptions of race, colonial power, capitalist extraction, and ecocide while performing the creative labour of rendering these geographies an “alterable terrain” (McKittrick Citation2006, xvii). In Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s focus on mining geographies, the terrain is already dug up, excavated, circulated and accumulated as various forms of material value and debris unevenly distributed across bodies and spaces along global racial and class lines. Their work necessitates attention to the geologic matter of generating “alterable terrain[s]” of spatial knowledge and memory.

In conversation with curators Clare Molloy and Fabian Schöenich in the first major publication on her work, Nkanga (Citation2017, 165–66) describes her artistic concern with “spaces of excavation, which leave a scarred landscape.” Instead of positioning excavated landscapes as sites of loss and destruction, Nkanga foregrounds their material connections to buildings and structures elsewhere, “each building being both the result of the excavation of a mountain and also the cause of holes in different parts of the world.” In response to Nkanga’s work, Denise Ferreira da Silva (Citation2017b, 248) argues that the continued expropriation of material and speculative value from Black(ened) bodies and spaces is crucial to global racial capitalism yet is obscured through the rendering of such value as “raw material.” Such logics are also integral to the formation of the Anthropocene as a conceptual and material formation. As Kathryn Yusoff (Citation2018, xii) argues, Black(ened) bodies and nonhuman matter were “presse[d]… into intimacy” through colonialism and slavery, forming the foundations for ongoing racialized infrastructures of environmental dispossession, extraction, and exhaustion.

Both Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s work connect racialized sites of mineral extraction to aesthetic production and display, building on Aimé Césaire’s (Citation1969, 52–53) geopoetic proposition that “not a corner of this world but carries my thumb-print/and my heel-mark on the backs of skyscrapers and my dirt/in the glitter of jewels!” “Instead of building a new monument to commemorate the absence or the act of emptying,” Nkanga (Citation2017, 165) asks, “[c]ould the emptied space be the monument?” Nkanga’s works Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine (Citation2015a), The Weight of Scars (Citation2015e), and Diaoptasia (Citation2015b) experiment with multiple visual and performative tactics for approximating “spaces of excavation” as not only “emptied space[s]” but also residual sites of violence, resurgence, and the production of waste materials, slag patches and scarred earth from the implicated location of the gallery space. Relatedly, Sibungu’s Quantum Ghost (2019) mobilizes the aesthetic capacity of debris in photographic, sonic, and sculptural practices as spectral presences and lively materialities in the deep temporal and unevenly durational afterlives of the mine.

Across these relations and differences, both artists offer forms for thinking through what Ann Laura Stoler (Citation2013, 2) calls “imperial debris,” or “the uneven temporal sedimentations in which imperial formations leave their marks.” Important here is Stoler’s emphasis on ongoing processes of “decimation, displacement, and reclamation” that manifest materially beyond the demarcated events of transition from colonial to postcolonial power, foregrounding the layered and multiple temporalities of colonial geographies. Gabrielle Hecht (Citation2018) further draws out the relationship between material and metaphor in her discussion of mining in South Africa through three “registers of residual governance” at work in the “afterlife of extraction.” These registers include “the governance of residues” involving the physical and conceptual management of waste and toxicity, “governance as afterthought” to already polluted and toxified lives and lands, and “governance that treats people as residual,” as waste.

I suggest that residue operates in Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s work as a material (if often illegible) archive of the accumulating, mutative impacts of racial and colonial violence across bodies and earth. Both artists also put pressure on the archive as a site of colonial knowledge production. Here, performance theorist Diana Taylor’s (Citation2003) account of “the archive and the repertoire” as modes of knowledge transmission offers a way to attend to the embodied, iterative, and speculative performances of memory and knowing in Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s work. Taylor (Citation2003, 19) writes that the archive generally refers to “supposedly enduring materials (i.e., texts, documents, buildings, bones)” while the repertoire refers to the more seemingly “ephemeral … embodied practice/knowledge (i.e., spoken language, dance, sports, ritual).” The repertoire “both keeps and transforms choreographies of meaning,” transferring social knowledge, memory, and embodied forms of processing trauma absented or erased by the archive, although the archive and the repertoire frequently work in tandem both in the operations of the (colonial) state and in performances of resistance or decolonial memory. Space is an important aspect across both modes; Taylor notes that the word archive etymologically refers to the building or place where records are kept, while the interdependent relationship between place and embodied action contour the possibilities of the repertoire.

Foregrounding imperial debris in ideas of the repertoire brings attention to transcorporeal agencies (Alaimo Citation2008) and porosities (King Citation2019) that index—but are not limited to—lingering racialized and colonial processes that unevenly waste and remake material environments. As I show in what follows, Nkanga’s and Sibungu’s residual repertoires contend with the specific materialities and mineral, colonial, and socio-political histories of what is now Namibia, which rarely appear in Black and critical geographic scholarship.Footnote1 They also necessitate staying with difficult questions of relation to the wasted, remnant, and scarred and the ways they are (re)produced or transformed in situated aesthetic encounters. In this context, I return to Nkanga’s work around Tsumeb.

MINING NAMIBIA: COLONIAL HISTORIES AND NKANGA’S GEO-AESTHETICS

Undergrounds (Remains of the Green Hill I)

Mineral extraction and colonial violence are closely entangled in what is now Namibia, although its colonial history cannot be reduced to the pursuit of mineral wealth. As George Steinmetz (Citation2007, 136) notes, for the first two decades of Germany’s colonial rule, European companies in the region were either largely inactive or searching for minerals and raw materials without making a profit. However, the completion of the Otavi railway in 1906 and the discovery of diamonds in the Namib desert in 1908 brought a “booming rush” (Melber Citation2014, 112) of explorations and investments by foreign mining companies. After the Union of South Africa invaded during WWI and were given mandatory power over South West Africa by the League of Nations, they initiated an exploitative contract labour system in which workers were segregated by gender, age, and ethnicity, and often transported away from their homes to bolster the burgeoning mining economy (Cooper Citation1999).Footnote2 In the second half of the century, Namibia became embedded in Cold War geopolitics as the Rössing mine supplied North America, Japan, and Western Europe with uranium. As Hecht (Citation2012, 96–105) describes, in the late 1960s and 1970s the British state and British-based multinational mining corporation Rio Tinto-Zinc (RTZ) manoeuvred around public and UN pressure for anti-apartheid politics, influenced by the anticolonial liberation movement the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO). Seeking to maintain a uranium supply from Rössing, these state and corporate actors contributed to the promotion of capitalist ethics as conditions for postcolonial sovereignty in Namibia.Footnote3 Following independence in 1990, mining remains the largest contributor to the Namibian economy. The Tsumeb mine stayed in operation for most of the twentieth century under a combination of American, British, and South African ownership, and the addition of a copper smelter in the 1960s led to the further growth of the town, with the mine providing an important source of azurite and dioptase. In the mid-1990s, a dip in metal prices, increasingly infeasible deep mining operations, and strikes by mineworkers put the Tsumeb mine out of action (Bruce, Southwood, and Schofield Citation2015). Although the post-independence owners Ongopolo Mining and Processing (OMP) brought about a resurgence in copper mining and smelting in the region, the mine at the Green Hill has been largely abandoned (Lanham Citation2005).

Remains of the Green Hill (2015c, ) is a video piece in the exhibition Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine (Citation2015a; see more images at https://kadist.org/program/nkanga-comot-exhibit/), one of a series of interconnected exhibitions Nkanga made following her time in Tsumeb.Footnote4 In the video, Nkanga interviews OMP’s former managing director Andre Neethling. Neethling laments the abandonment of the mine and argues for the need to industrialize Namibia in order to compete in global markets, claiming that “the time for Africa has come.” The interview is overlaid with images and footage of the mine site, including a spontaneous performance Nkanga undertook there; in one still from the film, she faces away from the camera, addressing the hole, body poised and hands raised, with rocks balanced on top of her head. The only visible green are the bushes that have grown around the edges of the hole, inside of which are scattered debris and tyres, against a horizon of old buildings and mining machinery.

FIGURE 1 Otobong Nkanga, Remains of the Green Hill, 2015, video still from performance, HD, 16:9, stereo sound, 5 minutes 48 seconds. Reproduced with permission.

Nkanga remakes the “emptied space” as “monument,” ephemeral in embodied performance yet enduring (in a different form) through recording. In Taylor’s (Citation2003, 20) terms, “the actions that are the repertoire do not remain the same”; the repertoire “both keeps and transforms choreographies of meaning” and plays upon the frictions and fractures between performer and role. Nkanga’s siting of her body in the scarred landscape suggests it is not only buildings and large-scale infrastructures that bear the unearthed matters of excavated sites. It is also corporeal lives unevenly made, sustained, and wasted by extracted materials (Yusoff Citation2013), from the fossil fuels powering everyday movement, to minerals in makeup (a recurring phenomenon in Nkanga’s aesthetics) and rare earth elements in smartphones. What is not immediately obvious in Remains of the Green Hill but becomes more apparent in the Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine exhibition is that the bodies sustained by extraction have an underneath: the racialized corporeal and inhuman energies subsumed within “raw material” (Ferreira da Silva Citation2017b), with dynamics of extraction and violence specific to Namibia.

Borrow You Mine

Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine registers accumulations of colonial violence in Namibian minescapes while also engaging with state and colonial archives to question the visual modes through which such histories are rendered il/legible. The title of the exhibition uses Nigerian Pidgin English, which Nkanga glosses as “take your eyes away, I’ll lend you mine.” This title—which for many (but not all) viewers in European art spaces might require translation—requests or perhaps demands critical reflexivity around who is looking, how they are looking, and from where. Nkanga interrupts assumptions of access to Black(ened) geographies and knowledges while drawing attention to the implicatedness of European aesthetics and art spaces in what Yusoff (Citation2021) calls the “spatial and subtending relations” of the “mine as paradigm,” a repeating material-symbolic scenario of extraction.

The large wall drawing () that made up one side of the exhibition includes several motifs that recur across Nkanga’s oeuvre. The left-hand panels of the mural feature a molecular or constellatory structure of archival photographs pertaining to the Tsumeb mine’s twentieth-century history, taken from the National Archives of Namibia. The middle panel links the constellation via painted lines to a black patch, unevenly shaped, with a gridded design overlaying it. The right-hand panels show a disembodied, puppet-like arm, holding one of several spikes that pierce through chunks of fractured blue-green rock. The arms and spikes reiterate and reconfigure elements from other visual and performance-based artworks, feeding into the repertory quality of Nkanga’s aesthetics. For example, in Solid Maneuvers (Citation2015d), the puppet arms that appear in many of Nkanga’s drawings were reconstituted by performers’ physical bodies. The performers were invited or directed to perform a repertoire of acts—rubbing, swiping, stroking, dropping, clamping, and throwing mineral sand and debris—with machine-like movements. As Nkanga (Citation2015b) describes in an interview with Catherine Wood, performativity occurs across her artistic practice as a way of “taking care” with minor “gesture[s]” and “movements.” Materialized through different media, Nkanga’s motifs perform a repertoire of recurring processes and gestures as increments of larger colonial geographies of extraction and their potential transformation.

FIGURE 2 Otobong Nkanga, Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine, 2015, wall drawing, acrylic, inkjet print on paper, spray paint, c. 260 × 1400 cm. Otobong Nkanga, Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine, KADIST Art Foundation, Paris, 2015c. Photo: Aurélien Mole. Reproduced with permission.

However, Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine also brings attention to located specificities of violence and the representational modes of their archiving in colonial and institutional historical records. On the mural, the earliest photographs in the constellation date from around 1903–1906 and show labourers building the OMEG railway, which cut directly through the lands of the Ovaherero people. Environmental historian Philipp N. Lehmann (Citation2014) suggests that the railway was a triggering factor for the Ovaherero’s 1904 uprising against the German colonial regime. The Ovaherero people were resisting ongoing land dispossession and proposals for reservations, labour exploitation, brutality and sexual violence, and the longer-term impacts of a devastating Rinderpest epidemic at the end of the nineteenth century that wiped out almost all the country’s cattle. In response to the Ovaherero’s actions, and a separate rebellion by the Nama people, German colonial forces undertook a targeted genocidal campaign, first killing Ovaherero and Nama people or driving them into the desert, then detaining them in concentration camps and forced labour (Lehmann Citation2014; Steinmetz Citation2007).Footnote5 Between 1904 and 1908, an estimated 60–80% of Ovaherero people and 50% of Nama people died (Hammerstein Citation2016).

This genocidal violence was underpinned by colonial organizations of the human, nonhuman, race, and environment. Drawing on a range of sources including German colonial statements and letters, and Ovaherero written and oral accounts, Katharina von Hammerstein (Citation2016) traces notions of the “human,” “nonhuman” and “nature” in the genocide. She quotes General Lothar von Trotha, the Commander in Chief of German South West Africa who announced the “annihilation order” against Ovaherero and Nama people. Von Trotha claimed that “[a]gainst ‘nonhumans’ one cannot conduct war ‘humanely’” and elsewhere described the genocide as a “race war” (Hammerstein Citation2016, 276–77). This violent rendering of people as nonhuman contrasts with other accounts of more-than-human relation in archives of the genocide. For example, describing what happened in the desert, Ovaherero Lutheran pastor Andreas Kukuri wrote that “people moved around unsuccessfully in the middle of the veld that had no water, until the living beings, the cattle and humans, all died of thirst” (Hammerstein Citation2016, 274–75). Kukuri suggests a co-relationship between the cattle and the Ovaherero that the colonizers attempted to exploit, but which also might exceed colonial grammars of the nonhuman. Elsewhere, Lehmann (Citation2014) traces how German military accounts presented the violence as a battle not only against people rendered “nonhuman” but also against the “hostile nature” the colonizers had struggled to conquer and control ever since entering the region. The collapse between the Ovaherero and “hostile nature” suggests the co-constitutively material and discursive positioning of Ovaherero people and nonhuman natures as obstacles to colonial extraction through a paradigm of conquest, with the “alien environment” operating as an “explanatory framework for the difficulties and failures” in colonial wars against “an opponent who was allegedly racially inferior” (Lehmann Citation2014, 554).

These contexts are important for the modes of visual and archival representation that Nkanga engages in Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine. None of the photographs in the mural shows the genocide in a legible way. In one of the images, a group of workers building the Otavibahn are lined up, carrying a pole, their arms outstretched and bodies perpendicular to the evenly spaced railway sleepers. Nkanga’s book Luster and Lucre (Citation2017, 274) includes a caption for the image, “Otavibahn railroad workers, ca. 1903–1906,” attributed to the National Archives of Namibia at Windhoek. There is no further information on who the labourers are or who took the photograph. In the next image, connected along the assemblage and appearing on facing pages in Nkanga’s book, the landscape is more visibly scarred and the image less cohesive; people are standing still in varying positions, many holding long-handled tools, some facing away but still seemingly static rather than engaged in the “work” that the caption suggests. Two young boys stand by a pipe underneath the railway track, looking directly, even piercingly, at the camera.

Saidiya Hartman (Citation2008, 5) cautions against the “libidinal investment in violence” often reproduced through treating archives as the means of knowledge about the past. Reflecting on the Namibian archival context, Zoé Samudzi (Citation2019) comments: “When I was in the National Archives in Namibia, there was a note on a number of genocide-era documents explaining that they had been destroyed, stolen, or sent back to Germany.” However, she notes, the relative “absence of evidence” of the genocide “is not evidence of absence”; rather, it remains present in European “scientific methods, epistemes, and discourses.”Footnote6 These epistemes, I suggest, include visual and aesthetic economies. Tina Campt (Citation2017) proposes “listening to images” as a way of challenging the equation of the visual with (extractable) knowledge in aesthetic encounters shaped by racial dynamics of looking. As a counter-practice when working with archival photographs of the Black diaspora, Campt “listens” to seemingly mundane details and affects as the “frequencies,” “resonances,” and “practices of refusal” of the dispossessed. In this context, the gaze of the photograph’s subjects can be listened to in a “tense” that is not “necessarily heroic or intentional” or “loud and demanding” yet retains the potential to be “disruptive” (Campt Citation2017, 17).

The photograph’s subjects do not become fully legible; the dis-composed scene of “Otavibahn railway workers” and their varying gazes unsettles photographic conventions at a time when photography was gaining importance as a means of colonial ethnographic knowledge production, and a decontextualized consumer product of colonial memorabilia and landscape aesthetics in German South West Africa (Silvester, Hayes, and Hartmann Citation1998, 13). By contrast, Nkanga situates the photograph in a constellation of other images that show mineworkers at Tsumeb across the twentieth century, and a mass meeting of SWAPO (the militant liberation force that would later become independent Namibia’s first democratically elected party) in Tsumeb in 1977. These images are further constellated with the drawings of punctured minerals, display cases containing physical minerals from Tsumeb, and Nkanga’s recurring motifs that extend beyond the singular iteration of the exhibition. Situated as part of a repertoire of the enduring afterlives of racialized extraction, the photograph of the railway workers registers and disrupts a visual economy that renders Ovaherero corporeal labours and violences as “raw material” (Ferreira da Silva Citation2017b) for ongoing racialized knowledge production and its material residues.

Unwanted Material (Remains of the Green Hill II)

In Remains of the Green Hill, Nkanga asks Andre Neethling about the “black patch” she noticed over the hill from Tsumeb. Neethling responds:

The black material is slag, it’s an unwanted product from the smelting process, it’s molten rock, it’s slag. That is normally just being dumped at the smelter and you create a site where you store it, and then what we did there was this big 14 tonne dump over the last 80 years or so that was fine powder. So if you use one of these tailings dumps where you dump your tailings, your unwanted material, and it’s operational, you circulate water because you transport the material with water, and then it settles, and the water comes back and you just use it. But when [the mining company] becomes redundant and there’s no water it becomes a major dust hazard. So sometimes in winter it’s this big, big cloud, it’s wind blown dust. (Nkanga Citation2015c)

Staying with the “black patch” turns us towards The Weight of Scars (Nkanga Citation2015e), a tapestry that Nkanga made for the exhibition Bruises and Lustre (MuHKA, Antwerp, 2015) that treats the ground itself as archive (). The tapestry features two figures (each with several puppet-like arms) assembled in a tug-of-war scene, pulling at a molecular or mineral-shaped constellation of images.Footnote8 Unlike in Comot, the images within the constellation are not from national archives but were taken by Nkanga, showing the remains of the mine from a range of scales and angles. One image shows a pipeline stretching into the distance, another is a close-up shot of cracked rock; there are abandoned bricks, bits of corrugated metal, holes and broken ground. All are devoid of people or other signs of life, yet the images do not seem static, particularly when assembled as part of The Weight of Scars’ dynamic constellation, set against an oceanic or cosmic backdrop of woven mohair, cotton, and synthetic threads, contoured with continental lines or hairline fractures, pockmarked with orange flecks and sinkholes. Damaged, wasted, fissured, exhausted through the lingering of political economies and ecologies of extraction and other temporalities of geological activity, these fragments of mineral landscapes remain mutative and in-process, unfolding on multiple scales. Attending to Nkanga’s work as residual repertoire draws out the layered, fractured temporalities that patches of slag and clouds of dust bear in sites of extraction. But how might these residues materialize future traces otherwise to Anthropocene spatio-temporal inscriptions of an unevenly exhausted earth?

FIGURE 3 Otobong Nkanga, The Weight of Scars, Citation2015e, woven textile (yarns: viscose, mohair, polyester, organic cotton, linen, acryl), inkjet prints on 10 laser-cut forex plates, four parts, 253 × 153 cm each, total size 253 × 612 cm. IN SITU: Otobong Nkanga, Bruises and Lustre/Kneuzingen en Glans, Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen/Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (MuHKA), Antwerp, 2015. Photo: Christine Clinckx (MuHKA). Reproduced with permission.

HACKED FUTURES: QUANTUM GHOST

Bringing Nkanga’s work into dialogue with Libita Sibungu’s offers ways to consider how processes of racialized colonial violence and inhuman temporalities embedded in “raw material” can be exposed but also folded into speculative imaginaries of other material arrangements. Like Nkanga, Sibungu activates the material capacities of archives beyond the re-presentation of extraction. Drawing from familial diasporic histories, archival documents, and found objects and materials, Quantum Ghost (2019) connects mining geographies in Namibia and the UK. Sibungu’s father, a member of SWAPO during the anticolonial and anti-apartheid struggle against South Africa, went into exile in the 1980s, came to Britain, and studied mining engineering at the Camborne School of Mines in Cornwall.

Where Nkanga’s aesthetics create a connective tissue between geographies of excavation and material infrastructures in a global context, Sibungu suggests another connective logic through diaspora. While there are multiple elements to this connection, the continuity of mining calls attention to planetary patterns of geological extraction and the structuring of racialized and classed labour. As suggested in the previous section, the geopolitics of mining were part of the dynamics of SWAPO’s transition from a largely left-wing anticolonial movement to a postcolonial state power promoting free market economic policies. Ellie Hamrick and Haley Duschinski (2018) argue that state narratives of Namibian national liberation often centre SWAPO but gloss over this shift, and frequently minimize the Ovaherero and Nama genocide and the systemic inequalities that Ovaherero and Nama peoples still face (SWAPO has historically been largely composed of the Ovambo majority ethnic group).

Meanwhile, studying mining in exile in the UK, Sibungu’s father entered a context where the Cornish tin mining industry, by then thousands of years old, was collapsing with the end of the International Tin Council agreement. Cheaper mining elsewhere (particularly in the Global South) and the Thatcher-led Conservative government policy of stamping out what the government saw as failing industries contributed to this process.Footnote9 Tracing these geopolitical entanglements from Namibia to the UK, Sibungu develops a repertoire from the remnants, the leftover stuff and its material, agential capacities. Turning to Quantum Ghost, I suggest that these residues assembled into a geo-aesthetics foreground temporal modalities underneath and beyond colonialism’s timelines of progress and decline, and racial capitalism’s growth cycles of boom and bust through “spatial fixes” of accumulation by dispossession (Harvey Citation2001; Moore Citation2015).

In its iteration at Gasworks, a small gallery close to an old gasometer in Oval, South London, Quantum Ghost opened onto a series of photograms printed on slick, glossy paper, appearing to emanate light (; see more images at https://www.gasworks.org.uk/exhibitions/libita-clayton-2019-01-24/). Unlike photographs, photograms do not require a camera; they are produced by placing objects directly onto the surface of photographic paper and then exposing it to light. Imprinted in these images—which resemble galaxies, constellations, X-rays—are mining rubbish, familial items, and scraps of newspaper documenting SWAPO’s activities during the liberation struggle. These materials are compressed into blackness, darkness, earth; in the layering and overexposure of the work, some of the objects become translucent, almost spectral, their solidity and permanence held in question. Notably, the photograms do not offer legible forms or narratives of identity and history; they are non-monumental in comparison to the “memorial politics” of state narratives of post-independence Namibia (Zuern Citation2012; Hamrick and Duschinski Citation2018). These incompletions and opacities suggest the fracturing and fragmentation of diasporic identity but also material agencies that might disrupt the primacy of “human” legibilities.

FIGURE 4 Libita Sibungu, Quantum Ghost, Gasworks, London, 2019. Installation view. Photo: Andy Keate. Reproduced with permission.

Drawing on the work of late nineteenth-century geologist and photographer William Jerome Harrison, Joanna Zylinska (Citation2018, 51–52) describes photography as “a light-induced process of fossilization occurring across different media” including soils and minerals as both a part of and apart from the materials used for photography as an art practice. Photography contains “an actual material record of life rather than just its memory trace”; it exposes material energies and processes in and as the making of representations, inscriptions, archives. This more-than-human agency, Sibungu’s and Nkanga’s work suggests, bears historical geographies of racialized, inhuman extraction—silver for silver gelatine emulsion, rare earths for camera lenses and studio lighting, tin for solder, fossil-fuelled bodies—across the uneven earth.

Drawing attention to these dynamics in the process of their performance suggests a repertory capacity at the level of material media, the detritus not only produced but also materially held by the photograms’ glossy surfaces. Combined with a critique of racialized extraction, Sibungu’s repertoire asks what it would take to undermine aesthetic space, turn it inside out. In the following paragraphs I seek to respond to the challenges of this question through an embodied, materially reflexive approach to Quantum Ghost, moving between tenses to aid attention to the work’s repertory processes. Such an approach is shaped by whiteness as the default positionality of the aesthetic subject in the racialized visual economies this article has discussed, and the reproductions I enact as a white critic moving through the physical and online archived spaces of the work. However, Nkanga’s (and, I suggest, Sibungu’s) work also “punctures the presumed transparency of the subject of aesthetic culture, whose whole ethical framework rests on a formulation of universality” (Ferreira da Silva Citation2017a), materializing broken, unevenly toxified, and im/possible conditions of response from the “position of the unthought” (Hartman and Wilderson Citation2003).

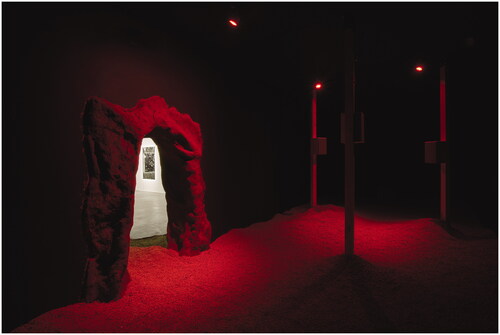

Across from the photograms’ opaque and spectral debris is a second entrance, a cave or tunnel mouth made from clay, sand, and straw (). The cave opens into a smaller, darker space with a floor covered in gravel whose crunch underfoot echoes more intensely deeper within the structure, which the exhibition guide compares to an ear canal. Inside, the lighting is deep red, and the stones are piled up around wooden posts with speakers, forming an undulating landscape. The quartz in the gravel glitters in the low, ambient light. A multi-channel sound piece plays on loop, layered: sounds of hacking and chipping away at rock, water flowing and bubbling, a low thudding that could be blood in the ears, pressure in the mine, and the voices of workers, perhaps spirits too. The loudest “voice” is distorted, slowed down and bent to the degree that its articulations blur into each other, thick, saturated, sticky. A voice of oil and water, voice of the slowly moving earth, repeating, viscously, “so soft.” High over the top, in a different pitch and rhythm, is a chorus, rising and falling in call and response with ancestors and/or future beings. They sing and lament as ghosts of the archive, future fossils, recurring lives and excesses in the debris of the overturned earth, through the water which bubbles up unexpectedly, polluted groundwater, erosional flow. Time is not linear or singular but multidimensional, multilayered.

FIGURE 5 Libita Sibungu, Quantum Ghost, Gasworks, London, 2019. Installation view. Photo: Andy Keate. Reproduced with permission.

“The miner’s ear,” the anthropologist Rosalind Morris (Citation2008, 96) writes, “is attuned to the sounds of catastrophe: sirens, rumbling, explosions, a gush of water where only a dripping should have been heard, coughing, the burble of fluid in the lungs… or too much silence.” The cumulative corporeal and transcorporeal impacts of “repeated exposure to loud, often repetitive and percussive noise,” Morris continues, contribute to a “spiraling deafness,” transforming “voices into mere sound and… many voices into constant but diminishing noise,” while the inhalation of particulate matter from the mine can lead to respiratory conditions and silicosis. The gallery space is not the mine, and the silence of the aesthetic subject is not the silence of the miner rendered through the absorption of residual matter unearthed and organised by colonialism and racial capitalism. Yet a “Black feminist poethics,” in Ferreira da Silva’s (Citation2017b) terms, works to expose or “blacklight” the expropriation of value from Black(ened) bodies and lands in the constitution of the aesthetic.

The live performance that closed Quantum Ghost, in which Sibungu was joined by collaborators Jol Thomson, Demelza Toy Toy, and Hannah Catherine Jones, re-sounded these material intimacies, extractive logics, and temporal disjunctions as repertoire. Over a mass of wires and sound technology equipment, Sibungu spoke into a microphone, producing the same deep, sticky tone as the voice in the installation. She also used other forms of articulation and gesture—chewing, taking off and shaking her jewellery, made from mined metals, in her palm—to make sound. Fed through the microphone and sound system, these minor gestures transformed into the sound of rocks. Meanwhile, close by, Jones sang and played a theremin, an instrument that does not require physical contact but instead works through the manipulation of a surrounding electromagnetic field. With these more-than-human, quasi-supernatural elements, intimacy and contingency felt quantum, operating beyond physical touch or the linear logics of cause and effect.

In the exhibition notes, Sibungu cites Black Quantum Futurism (BQF), a theory and practice developed by lawyer Rasheedah Phillips and musician Camae Ayewa (Moor Mother), collaborative artists and community activists in Philadelphia. BQF draws on African and Afrofuturist conceptions of temporality, and quantum physics. As Phillips (Citation2015, 11) describes, BQF is a speculative, collective approach to “living and experiencing reality by way of the manipulation of space-time in order to see into possible futures and/or collapse space-time into a desired future in order to bring about that future’s reality.” Sibungu’s suturing of the quantum and the geologic via BQF suggests another way of listening to the photograms in the gallery. This listening might happen through a “tense” of Black feminist futurity that will have had to bear the unknowability of what debris, heavy bodies, and visual and sonic noise might make in their endurance (Campt Citation2017). Inhuman agencies and their overlapping, colliding, slipping, frictional temporalities become part of a residual repertoire of mineral intimacies, their violent productions and otherwise futural potentials.

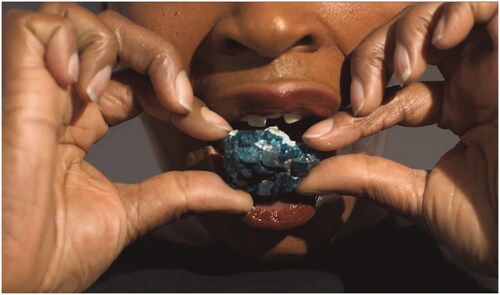

Placed in proximity to Quantum Ghost, Nkanga’s online live performance piece Diaoptasia (2015b, ) renders these futures as “uneven, hackly, splintery, earthly.” By contrast with the sticky vocals, “so soft,” in Quantum Ghost, Diaoptasia takes place in a language that is “fractured.” The performance opens with Nkanga appearing to swallow a lump of green rock—presumably dioptase, which has a high silica content—implying the work of minerals in and through the body, bioaccumulating, mutating, enabling, depending on social positioning in uneven geographies of exposure. Such geographies materialize imperial debris in action for those populations and more-than-human ecologies that are continually exposed, even in ostensibly postcolonial settings. In her conversation with curator Catherine Wood after the performance, Nkanga refers to the way that languages of articulation “fractured” by colonialism can be “hacked, broken, turned” to become “something else, which is also a way of resistance.” Like in Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine, Nkanga’s use of Nigerian Pidgin shifts orientations to a Global South positioning where “as I dey tanda so, my eyes dey torchlight for una North” (which Nkanga glosses as “as I stand here, my eyes send to a torchlight to you in the North”).Footnote10 From (t)here, Diaoptasia suggests:

Our future is to live with bruises,

Uneven, hackly, splintery, earthly

Sometimes brittle, sectile, malleable, flexible

and elastic

Will we be able to resist

the crushing, tearing, bending and breaking?

Could we be easily broken

Into powder by the cutting and hammering?

Would we be pounded

Into thin sheets like brass or copper?

Will we be bent to not return

To our original form when stress is released?

Would we be bent like a string

Only to return to the original form when stress

is released? (Nkanga Citation2017, 47)

FIGURE 6 Otobong Nkanga, Diaoptasia, 2015b, conceived for online live streaming, performed by Nkanga, photographic images printed on paper, mounted on wooden boards, body fitting wooden, paper, and tape sculpture, hair-sculptured copper wires, minerals (azurite, dioptase, malachite, chrysocolla), glitter, makeup powder, metal rods, sound, 35 min, BMW Tate Live: Performance Room, Tate Modern, London, November 26, 2015. Reproduced with permission.

In their repertory practices, both Nkanga and Sibungu materialize the transcorporeal embodiment of mineral aesthetic and political economies as the conditions of the present, but also open out speculative futures grounded in ongoing material processes and particular geographies. In doing so, they generate “hacked” sensory registers that at once expose colonial fracturing, and speculate around malleable futures of mineral intimacy. As Kara Keeling (Citation2019, 2) notes, speculative imaginaries are not liberatory in themselves; fossil fuel companies also use speculation and “scenario-building” practices to map out possibilities for continued accumulation, often through geographical (and colonial) metaphors of exploration. However, I suggest that Nkanga and Sibungu develop materially grounded speculative practices as methods to reinhabit lingering residual proximities and to bend colonial coordinates of spacetime without legible knowledge of the outcome in advance.

UNEARTHING, UNENDING

In this article I have argued that Nkanga and Sibungu layer visual, sonic, and performance practices to re-excavate material and symbolic economies at work in the residual geo-aesthetics of racialized colonial extraction. In Nkanga’s repertoires, both the hole and the archive are sites of imperial debris to be attended to and reassembled in constellatory configurations that make scarred landscapes (and those exhausted and exposed by them) perceptible otherwise. Questioning the visual modalities of the colonial archive, Nkanga reorients towards the underneaths, shimmering surfaces, and uneven spatialities of aesthetic production and circulation. Sibungu’s practice finds and makes crevices of opacity in material diasporic archives, activating debris as constitutive of other modes of embodied sensing, and looping, fissuring time and memory. These residual repertories fold the spectral intimately into the earthly, futures into pasts brought into unrest.

The artworks I have attended to in this article generate unfinished methods of unearthing geographies of violence but also listening for and making from the residual noise of what lingers, clogs, and outlasts, sometimes in illegible or unrecognisable forms. Could these works open up an earth-writing where the detritus of racial capitalist space-making resonates differently? Crucially, these Black repertory geo-aesthetics suggest a refusal to end and of the end as spatio-temporal boundary: the end of colonialism with postcolonial independence in the context of global racial capitalism; the end of an exhausted mine with its lingering bodily and ecological effects; the end of the world in the Anthropocene with its racialized logics of catastrophe. The end of specific, interconnected, repeating scenes of extraction, Nkanga and Sibungu suggest, cannot occur through transparent recuperation or repair, conceptually reproducing the colonization of the future. Rather, their work prompts reckoning with the mess, debris and afterlives, through unevenly implicated practices of sensing otherworlds already reverberating and opaque in fractured, unfinished earths.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Professor Deborah Dixon and the two anonymous reviewers for their insights and suggestions. Earlier versions of this work were presented at the Art in the Anthropocene conference (Trinity College Dublin, 2019), the ASLE-UKI biennial conference (University of Plymouth, 2019), and the Inhuman Memory conference (King’s College London, 2022)—thank you to attendees for comments and questions. Otobong Nkanga and Libita Sibungu kindly granted permission to reproduce images of their work.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kate Lewis Hood

KATE LEWIS HOOD is a Research Associate on the Smart Forests project in the Department of Sociology at the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 1SB, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. Kate’s doctoral research at Queen Mary University of London focused on how Black and Indigenous poetic practices address material environments transformed by colonialism, racial and extractive capitalism, and assemble other socio-ecological possibilities.

Notes

1 Examples of scholarship that attends to the relationships between material residues and racialization in different geographies includes Pavithra Vasudevan’s (Citation2021) work on the “racialized industrial toxicity” of aluminium in North Carolina, and Vanessa Agard-Jones’s (Citation2014) work on pesticides and body burdens in Martinique.

2 The Union of South Africa, a united self-governing dominion of the British Empire, was established in 1910. During WWI, South African Prime Minister Louis Botha supported the Allied powers and invaded German South West Africa, and after the war the League of Nations gave South Africa mandatory power over the former German colony. See Melber (Citation2014).

3 Hecht (Citation2012) offers a detailed account of British strategies, including relabelling Namibian uranium as a British product or transporting it in unmarked containers to elude mounting domestic and international pressure not to use Namibian uranium. By 1976, Hecht notes, SWAPO signalled in private meetings with members of the British government that while they would continue publicly to contest extraction at Rössing, a post-independence SWAPO government would not disturb RTZ’s presence there.

4 These exhibitions are: In Pursuit of Bling (8th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2014), Crumbling Through Powdery Air (Portikus, Frankfurt, 2015), Comot Your Eyes Make I Borrow You Mine (Kadist, Paris, 2015), and Bruises and Lustre (Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp MuHKA, Antwerp, 2015).

5 When Commander in Chief Lothar von Trotha’s “annihilation order” came to an end in 1905, there was a shift from extermination of Ovaherero and Nama peoples to a focus on labour, but conditions in the camps meant that in practice the colonial regime was still intent on inflicting suffering (Steinmetz Citation2007).

6 Samudzi (Citation2021) attends to the relationship between racialization and spatial and knowledge production operative in the genocide, focusing on the colonial taking and retaining of skulls of deceased Ovaherero and Nama peoples incarcerated in the concentration camps and their use in European constitutions of racial science.

7 Hamrick and Duschinski (Citation2018) argue that SWAPO’s “One Namibia, One Nation” slogan ostensibly unites all ethnic groups in the country while in practice distributing resources, including those from Global North development aid and (albeit limited) German reparations for the genocide, primarily to Ovambo people.

8 In arrangement, The Weight of Scars also resembles (and further dynamizes) an earlier drawing, Social Consequences I: Crisis (2009).

9 In the nineteenth century, hundreds of thousands of Cornish people had emigrated owing to the lack of mining work in Cornwall, often moving to British colonies and other places in the New World where mineral deposits had been discovered. Recent work on the remnants of mining in Cornwall has focused on the heritage industry; for example, Peter Oakley (Citation2018) describes the complex maintenance and management or “contrived dereliction” required to present an appropriate “aesthetic of decay” for mining heritage sites.

10 This attention to visioning is also implicit in Diaoptasia’s title: dia is the Greek for through, during, across (OED); optasia means “vision…appearance,” “the act of exhibiting oneself to view” (Liddell-Scott-Jones); and dioptase is “a translucent silicate of copper, crystallizing in six-sided prisms, called emerald copper ore” (OED) found in abundance at Tsumeb mine.

REFERENCES

- Agard-Jones, V. 2014. Spray. Somatosphere, May 27. Accessed August 19, 2022. http://somatosphere.net/2014/spray.html/.

- Alaimo, S. 2008. Trans-corporeal feminisms and the ethical space of nature. In Material feminisms, ed. S. Alaimo and S. J. Hekman, 237–64. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Brigstocke, J., and G. Gassner. 2021. Materiality, race, and speculative aesthetics. GeoHumanities 7 (2): 359–69. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2021.1977163.

- Bruce, I., M. Southwood, and L. Schofield, eds. 2015. History: The eighties and nineties. Tsumeb.com. Accessed January 12, 2021. http://www.tsumeb.com/en/history/the-80s-and-90s/.

- Campt, T. M. 2017. Listening to images. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Césaire, A. 1969. Return to my native land, trans. John Berger, and Anna Bostock. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Cooper, A. D. 1999. The institutionalization of contract labour in Namibia. Journal of Southern African Studies 25: 121–38.

- Ferreira da Silva, D. 2017a. 1 (life) ÷ 0 (blackness) = ∞ – ∞ or ∞/∞: On matter beyond the equation of value. e-flux 79. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/79/94686/1-life-0-blackness-or-on-matter-beyond-the-equation-of-value/.

- Ferreira da Silva, D. 2017b. Blacklight. In Otobong Nkanga: Luster and Lucre, ed. C. Molloy, F. Schöneich, and P. Pirotte, 245–53. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Hammerstein, K. 2016. The Herero: Witnessing Germany’s “Other Genocide.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 20 (2): 267–86. doi:10.1080/17409292.2016.1143742.

- Hamrick, E., and H. Duschinski. 2018. Enduring injustice: Memory politics and Namibia’s Genocide reparations movement. Memory Studies 11 (4): 437–54. doi:10.1177/1750698017693668.

- Hartman, S. 2008. Venus in two acts. Small Axe 12 (2): 1–14.

- Hartman, S., and F. B. Wilderson III. 2003. The position of the unthought. Qui Parle 13 (2): 183–201.

- Harvey, D. 2001. Globalization and the ‘Spatial Fix’. Geographische Revue 2: 23–30.

- Hecht, G. 2012. Being nuclear: Africans and the global uranium trade. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Hecht, G. 2018. Residue. Somatosphere, January 8. Accessed August 19, 2022. http://somatosphere.net/2018/residue.html/.

- Keeling, K. 2019. Queer times, black futures. New York: New York University Press.

- King, T. L. 2019. The Black Shoals: Offshore formations of black and native studies. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Lanham, A. 2005. From copper closure to African copper centre. Mining Weekly, February 11. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://www.miningweekly.com/article/from-copper-closure-to-african-copper-centre-2005-02-11.

- Last, A. 2017. We are the world? Anthropocene cultural production between Geopoetics and Geopolitics. Theory, Culture & Society 34 (2–3): 147–68. doi:10.1177/0263276415598626.

- Lehmann, P. N. 2014. Between Waterberg and Sandveld: An environmental perspective on the German–Herero War of 1904. German History 32 (4): 533–58. doi:10.1093/gerhis/ghu105.

- McKittrick, K., and C. Woods, eds. 2007. Black geographies and the politics of place. Boston: South End Press.

- McKittrick, K. 2006. Demonic grounds: Black women and the cartographies of struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- McKittrick, K. 2021. Dear science and other stories. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Melber, H. 2014. Understanding Namibia: The trials of independence. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Moore, J. W. 2015. Capitalism in the web of life: Ecology and the accumulation of capital. London: Verso.

- Morris, R. C. 2008. The Miner’s Ear. Transition 98: 96–115.

- Nkanga, O. 2015a. Comot your eyes make I borrow you mine. Exhibition and wall drawing. Paris: KADIST Art Foundation.

- Nkanga, O. 2015b. Diaoptasia. Tate Performance Room | BMW Tate Live, November 26, 2015. Video. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://youtu.be/iR8_t1AM0dw.

- Nkanga, O. 2015c. Remains of the Green Hill. Video. Paris: KADIST Art Foundation.

- Nkanga, O. 2015d. Solid Maneuvers. Performance, December 17. Antwerp: MuHKA.

- Nkanga, O. 2015e. The Weight of Scars. Woven textile. Antwerp: MuHKA.

- Nkanga, O. 2017. Otobong Nkanga: Luster and Lucre, ed. C. Molloy, F. Schöneich, and P. Pirotte. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Oakley, P. 2018. After mining: Contrived dereliction, dualistic time and the moment of rupture in the presentation of mining heritage. The Extractive Industries and Society 5 (2):274–80.

- Phillips, R. 2015. Constructing a theory and practice of Black Quantum futurism. In Black Quantum Futurism: Theory & practice, Volume One, ed. R. Phillips, 11–30. Philadelphia: House of Future Sciences Books.

- Samudzi, Z. 2021. Looting the archive: German Genocide and Incarcerated Skulls. Social and Health Sciences 19 (2): 10490. doi:10.25159/2957-3645/10490.

- Samudzi, Z. 2019. A memory, A Relic. Open Space, November 6. Accessed January 12, 2021. https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2019/11/a-memory-a-relic/.

- Sibungu, L. 2019. Quantum Ghost. Installation. London: Gasworks.

- Silvester, J., P. Hayes, and W. Hartmann. 1998. This ideal Conquest’: Photography and colonialism in namibian history. In The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the making of Namibian history, ed. P. Hays, J. Silvester, and W. Hartmann, 10–9. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press.

- Steinmetz, G. 2007. The Devil’s Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Stoler, A. L. 2013. The Rot Remains’: From Ruins to Ruination. In Imperial Debris: On ruins and ruination, ed. by A. L. Stoler, 1–35. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Taylor, D. 2003. The archive and the repertoire: Performing cultural memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Vasudevan, P. 2021. An intimate inventory of race and waste. Antipode 53 (3): 770–90. doi:10.1111/anti.12501.

- Woods, C. 1998. Development arrested: The blues and plantation power in the Mississippi Delta. New York: Verso.

- Yusoff, K. 2013. Geologic life: Prehistory, climate, futures in the anthropocene. Environment and Planning D 31 (5): 779–95. doi:10.1068/d11512.

- Yusoff, K. 2018. A Billion Black anthropocene or none. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Yusoff, K. 2021. Mine as paradigm. e-flux Architecture, July 2021. Accessed September 7, 2021. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/survivance/381867/mine-as-paradigm/.

- Zuern, E. 2012. Memorial politics: Challenging the Dominant Party’s narrative in Namibia. The Journal of Modern African Studies 50 (3): 493–518. doi:10.1017/S0022278X12000225.

- Zylinska, J. 2018. Photography after extinction. In. After extinction, ed. R. Grusin, 51–70. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.