ABSTRACT

International cybersecurity capacity building emerged in the mid-2000s as a mechanism for countries and organisations to assist each other, across borders, in protecting the safe, secure and open use of the digital environment. In parallel with this practical cooperation, the international community negotiated norms and confidence building measures to support peace and stability in cyberspace. The purpose of this paper is threefold. Having critiqued previous definitions and frameworks for cybersecurity capacity building, the paper proposes alternatives that both better represent actual practice and are of more use to the negotiations on stability in cyberspace. The proposed framework shifts capacity building beyond developed-developing country relationships and stresses the many goals that it serves. The paper then explores the relationship between cybersecurity capacity building, norms and confidence building measures. It contends that capacity building does not just support norms and confidence building measures, but is also an instance of them, and it benefits from norms of its own. The paper concludes by considering the proposals for cybersecurity capacity building principles that emerged from the 2019–2021 round of cyberspace diplomacy at the United Nations and by recommending the next steps.

Introduction

The digitisation of economies, governments and societies has been a transformative process, bringing many benefits for those it has reached. States, industry and development agencies want to expand the reach of this digitisation and are investing heavily in the availability and application of information communication technologies (ICTs). They are also mindful of the need to ensure safe, secure and open access to these ICTs in the face of rapidly growing cybersecurity threats. This need to protect the resilience and openness of the digital environment is an individual and collective concern. Harm or restrictions experienced in any one country or organisation have the potential to cause problems throughout the interconnected global digital system.

Cybersecurity capacity building is a form of international cooperation that emerged in the mid-2000s to share the knowledge and skills that are needed to protect the digital environment. It is a form of cooperation that has been used by many different communities of practice, from technical incident responders to police officers tackling cybercrime to civil society trainers. Together they form a patchwork that this paper refers to as the cybersecurity capacity building community. As in any community, some parts come together frequently, while others meet and collaborate rarely. However, they are all connected by a shared interest in helping governments, organisations and individuals, in countries other than their own, to develop the capacities they need to protect their safe, secure and open access to ICTs.

States have a complex relationship to cybersecurity, being both the source and target of the most sophisticated and harmful threats. Several countries are in a technological race for the most advanced capabilities to protect their own systems and explore, or act within, their opponents’. Behind these front runners, most countries are interested in what second- or third-tier capabilities they can purchase for defensive, intelligence or offensive purposes.

All countries have agreed, through 20 years of negotiations, that the use of these capabilities should be constrained by international law and norms of responsible state behaviour. They have also agreed that measures are needed to build trust and confidence between countries so that the chance of misunderstanding is reduced, and stand-offs can be more easily de-escalated.

In 2019, the United Nations launched a new round of negotiations on these issues to further develop the norms and confidence building measures (CBMs) proposed in earlier rounds and to explore more deeply the role that cybersecurity capacity building should play in supporting them. This paper responds to that process by asking the following questions. How do we define cybersecurity capacity building? What is its relationship to norms and CBMs? How does the latest round of UN negotiations advance the principle-based approach to cybersecurity capacity building and what should the next steps be?

First, this paper considers several definitions of cybersecurity capacity building and the developed-developing, donor-beneficiary framework they often presuppose. It proposes a new definition and framework that better reflects the realities of capacity building and better serves the norms and confidence building agenda. Second, the paper argues that the relationships between cybersecurity capacity building, norms and confidence building measures are more complex than previously described: capacity building is an enabler of norms and CBMs, but could also be an instance of them, and it benefits from its own set of norms. Third, the paper proposes some improvements to the capacity building principles proposed by the UN Open-Ended Working Group and recommends three next steps: communication and consultation on the principles; fleshing the principles out with content; and consolidating feedback and proposals into a set of developed principles with global, multistakeholder support.

Background

The history of cybersecurity from the earliest incident to the start of international cybersecurity capacity building spans approximately 30 years. The first computer virus was created in 1971, and the first prosecution for a cybercrime was in response to a piece of damaging code naïvely released into the young internet in 1988 (Akhgar, Staniforth, and Bosco Citation2014). By the late 1990s, disruption to the internet and email was causing sufficient harm to prompt serious international policy discussion. Russia introduced the first UN resolution on ICTs and international stability in 1998 (United Nations General Assembly Citation1999; Brunner Citation2020). Four years later, the idea of cybersecurity capacity was also on international agendas. In 2002, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Plenipotentiary in Marrakesh passed Resolution 130, giving the ITU a mandate for ‘building confidence and security in the use of ICTs’ (International Telecommunications Union Citation2002, 336). That same year, NATO included the need for capacity building in its report, ‘Vulnerability of the Interconnected Society’ (North Atlantic Treaty Organization Citation2002, 12). Although the seed had been planted, it would take a few more years before the first capacity building projects began in earnest. At the time of writing, the Cybil Portal repository of cybersecurity capacity building projects shows the earliest project starting in 1998, but it isn’t until 2005 that a second project is recorded and not until 2009 that the number of projects per year exceeds 10 (Cybil Portal Citation2021).

Since the mid-2000s, international cybersecurity capacity building has steadily grown and professionalised but it has had a low profile. I estimate the number of cybersecurity capacity building projects has passed the thousand mark, but these have small budgets in comparison with projects in mainstream international development. Programmes over $10 million are rare. The cybersecurity capacity building community suffers from silos because it draws in people and projects from a wide variety of parent communities (Pawlak and Barmpaliou Citation2017). However, several coordinating mechanisms, notably including the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE), and a few proactive regional economic community organisations, have begun breaking these silos down.

In contrast, the work of developing an international stability framework for cyberspace has been characterised by spurts of activity in higher profile negotiating rounds and milestone agreements. In 2013, the UN Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of ICT in the Context of International Security (GGE) delivered a consensus report that agreed ‘international law, and in particular the Charter of the United Nations, is applicable, and is essential in maintaining peace and stability and promoting an open, secure, peaceful and accessible ICT environment’ (United Nations General Assembly Citation2013). This was reaffirmed in the GGE’s second round report in 2015, along with a refined set of norms for responsible state behaviour (United Nations General Assembly Citation2015). In parallel, between 2012 and 2016, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe developed a set of 16 CBMs (OSCE Permanent Council Citation2016). Together these initiatives put in place the three key pillars of the stability framework: an agreement that international law applies; a set of norms for state behaviour; and a set of CBMs.

The forum for the latest round of negotiations has been two parallel United Nations initiatives that were launched in 2019: the UN Group of Government Experts (GGE) and a UN Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG). There were differences in the groups’ mandates and composition,Footnote1 but both discussed how to advance the three pillars of international law, norms and CBMs, and what role capacity building should play. The OEWG issued its final substantive report on 10 March 2021 and the GGE presented its report in May.

The need for capacity building has been firmly established in previous GGE rounds and the literature (Pawlak Citation2016a; Hitchens and Gallagher Citation2019; Homburger Citation2019). As the GGE 2015 report puts it: ‘While [normative] measures may be essential to promote an open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful ICT environment, their implementation may not immediately be possible, in particular for developing countries, until they acquire adequate capacity’ (United Nations General Assembly Citation2015).

A Research ICT Africa discussion paper provides a practical example of why norms and CBMs depend upon capacity building (Research ICT Africa Citation2019). The context for their example is that the GGE 2015 report calls upon countries to share information about ICT vulnerabilities and available remedies as a norm of responsible government behaviour. However, governments can only do this if they have the technical capacity to identify useful vulnerability and threat information and the intergovernmental relationships to then share it with the appropriate points of contact in other countries. Research ICT Africa pointed to data from the International Telecommunications Union that indicated only 13 African countries had a team – called a national Cyber Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT) – to do this work as of March 2019. Without such a team, a country would find it very difficult, if not impossible, to implement the norm. Capacity building can help by assisting countries in setting up these missing CSIRTs.

Cyber security capacity building also supports the negotiation of norms and CBMs. Projects can provide training to help diplomats take part in the UN negotiations (Cybil Portal Citationn.d.; Amazouz Citation2016). Furthermore, community events can provide a platform for communicating about, and engaging with, the processes developing norms and CBMs. For example, the GFCE and African Union Commission used the 2019 GFCE Annual Meeting in Addis Ababa to help African policy-makers and stakeholders engage with the norms and CBMs debate by inviting the GGE and OEWG to hold outreach meetings in parallel with the event (United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs Citation2019).

Methodology

This paper’s discussion of definitions and frameworks for cybersecurity capacity building is informed by a literature review of academic and grey literature using variations of the field’s name as the search term. To understand how capacity building is being discussed within the GGE and OEWG, the paper draws on the author’s experience of the last GGE, the final substantive report of the OEWG (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021) and related documentation on the UN website, public submissions to their consultation exercises and interviews with two diplomats involved with the negotiations.

The roots of the term cybersecurity capacity building

Most international relations papers can briefly define their terms before moving on to the substance of their argument. However, there is no agreed definition of cybersecurity capacity building. Even the name of the field itself is still to be settled. There has been little discussion of this in the literature. Furthermore, the definition we use for cybersecurity capacity building, and the framework of relations between countries assumed by that definition, affect its contribution to norms and CBMs. Therefore, the first half of this paper will explore what cybersecurity capacity building is and why our framing of it matters for the negotiations at the UN.

The concept of capacity building has its origins in 1940s public administration. Half a century later, it was adopted by the international development community (Pawlak Citation2016b). In 2002, a UN report to the Secretary General described it as a means to help beneficiary countries ‘invent, develop and maintain institutions and organisations that are capable of learning and bringing about their own continuing transformation, so that they can better play a dynamic role to sustain national development processes’(United Nations Citation2002, 14). In international development, the term capacity building is a contested concept (Connelly Citation2007). One critique of it is that the definition has been left ambiguous deliberately to avoid accountability to those whose capacity is meant to be built (Connelly Citation2007; Wilén Citation2009, 338).

Cybersecurity is also a hotly contested concept (Dunn Cavelty and Wenger Citation2020, 8). The European Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) conducted a comparison of definitions and proposed the following as a standardisation:

Cybersecurity shall refer to security of cyberspace, where cyberspace itself refers to the set of links and relationships between objects that are accessible through a generalised telecommunications network, and to the set of objects themselves where they present interfaces allowing their remote control, remote access to data, or their participation in control actions within that Cyberspace. (ENISA et al. Citation2015, 7)

The cybersecurity capacity building community has combined these two contested concepts to form the name of their new field. They have then introduced two additional complexities: many practitioners replace ‘cybersecurity’ with ‘cyber’; and some replace ‘capacity building’ with ‘capacity development’. As a result, the community uses at least four different combination terms to describe what they do.Footnote2

This paper will not make a case for one variation of the term over the others. Instead, it will adopt the term most used in strategic policy documents – cybersecurity capacity building – while noting that this may be overtaken in popularity by one of the alternatives.

Definitions of cybersecurity capacity building

Just as there are several variations on the term cybersecurity capacity building, so there is no standardised definition of it. Several alternatives have been proposed in the literature, but with a limited critical discussion of their respective merits. The definition the capacity building community chooses for itself will influence both the future development of the field and the role it plays in the international cyber stability framework. The definition affects the boundaries of the field, the methodologies used for activities, and the expectations the community has about the sort of relationships states should have with each other and with non-state actors. Here I group the definitions in the literature into four clusters.

The first two clusters of definitions were identified by Homburger, who found from her own literature review that ‘cybersecurity capacity building is often defined as the support provided to developing countries with the aim to increase access to and benefit from cyberspace’Footnote3 or ‘a way to empower individuals, communities and governments to achieve their developmental goals by reducing digital security risks’Footnote4 (Homburger Citation2019, 227).

There is a third cluster of definitions in the literature that stem from Pawlak’s (Citation2014) proposal that cyber capacity building is ‘an umbrella concept for all types of activities (e.g. human resources development, institutional reform or organisational adaptations) that safeguard and promote the safe, secure and open use of cyberspace’, where cyberspace is ‘a digital environment (i.e. the internet, telecommunications networks or computer systems) that people use as means to achieve their social, economic or political goals’ (Pawlak Citation2014, 6). This definition was later adopted by Muller (Citation2015).

Finally, there are two other definitions in the literature that can group in a fourth cluster. The first of these is the definition in the EU’s Operational Guidelines, which says, ‘capacity building in the cyber domain aims to build functioning and accountable institutions to respond effectively to cybercrime and to strengthen a country's cyber resilience’ (European Commission et al. Citation2018, 10). The second is from Barbero, who defines cybersecurity capacity building

as the development and reinforcement of processes, competences, resources and agreements aimed at strengthening national capabilities, at developing collective capabilities and at facilitating international cooperation and partnerships in order to respond effectively to the cyber-related challenges of the digital age. (Barbero and Berglund Citation2021, 4)

A critique of cybersecurity capacity building definitions and frameworks

A feature of the definitions that Homburger found most common in the literature is that they place development at their heart: cybersecurity capacity building is either for developing countries or it is to achieve development goals. I believe that such definitions are flawed and that there are better frameworks for cybersecurity capacity building than ones built upon the distinction between developed and developing countries. This is not to say that development theory and practice should not be better represented in cybersecurity capacity building – a recommendation with which I agree (Pawlak and Barmpaliou Citation2017, 17).

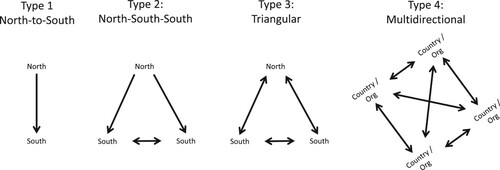

The framework of developed countries helping developing ones appears so often in the literature on cybersecurity capacity building that it is worth exploring some of its variations and a better alternative. The least accurate definitions of cybersecurity capacity building imply that it occurs in only one direction: between a donor in the Global North and a beneficiary in the Global South (Type 1, North-to-South in ). Some definitions improve on this by recognising that capacity building also occurs between Global South countries (Type 2, North–South–South). A further improvement is to note that the capacity of the more developed partner is also strengthened through these capacity building relationships (Type 3, Triangular). What has not been made explicit in any of the literature is that there is one further step we can take to improve the definition by including the capacity building that occurs in North–North partnerships.Footnote5 The end result is a multidirectional framework of cybersecurity capacity building in which any country could potentially assist any other country (Type 4). Given the complexity of the network of relationships between cybersecurity capacity building actors, most of whom are not governments, I contend that it would be unhelpful to continue using their location in the Global North or South as the primary way to categorise them.

In addition to overlooking capacity building activities through which developed countries assist each other, the developed-developing framework suffers from three further weaknesses. The first being that it presupposes that economic development is the key determinant of whether a country is a giver or a taker of cybersecurity capacity building assistance. However, economically developing countries can have stronger cybersecurity capabilities than economically developed ones.

Homburger’s solution is to adapt the donor-beneficiary framework so that it is based on levels of ICT development (Homburger Citation2019, 228). However, this still leaves a variant of the original problem, in that it now excludes activities through which ICT-capable countries help build each other’s cybersecurity capacity. Homburger’s solution also faces a practical challenge, which is that, unlike economic development, there is no authoritative system for categorising countries by levels of ICT or cybersecurity development.Footnote6

A second weakness in the traditional donor-beneficiary framework is that it is state-centric. However, many cybersecurity projects are funded and implemented by non-state actors – including individuals, companies, academia and civil society – who do not fit neatly into the categories of a developed donor or developing beneficiary (Calandro and Berglund Citation2019, 4).

Non-state and non-traditional actors are increasingly important in international development too. This has been met with proposals ‘to construct an aid architecture for the twenty-first century that broadens the current system to be inclusive of both existing and potential new players and new modalities’ (Fengler and Kharas Citation2010, 2). In other words, the architecture and frameworks of international development are themselves in transition. As a new multidisciplinary field, cybersecurity capacity building has the opportunity to create its own architecture and frameworks, suited to its own circumstances and reflective of the broad range of parent communities and their modalities. It should do much more to engage with, and learn from, international development, but it does not need to adopt its traditional, state-centric donor-beneficiary framework.

Learning from the development literature, we can identify another weakness with adopting the donor-beneficiary framework: it encourages privileging the financial component of a project over other resource inputs (Contu and Girei Citation2013, 222). Thinking in terms of donors and beneficiaries feeds a tendency to downplay both the non-financial inputs of the ‘beneficiary’ – such as staff time and political capital – and the benefits of the project to the ‘donor’. Using other frameworks can reduce this bias. In fact, the multidirectional framework positively encourages us to treat every partnership as unique and avoid assumptions about what each party is contributing and gaining.

The third flaw in the developed-developing, donor-beneficiary framework afflicts those definitions that make development the aim of cybersecurity capacity building. While it is certainly true that cybersecurity capacity building can contribute to sustainable development (Morgus Citation2018), this is not the only possible goal. Cybersecurity capacity building projects also take their objectives from other parent communities, including security, justice, foreign policy, government, business, internet governance, technical standards, human rights and digital access. With such a wide range of possible goals, it would be better to build a definition of cybersecurity capacity building upon the nature of its activity rather than the higher-level aims it serves.

A better framework and definition for cybersecurity capacity building

In contrast to a developed-developing, state-centric framework, this paper recommends a multidirectional, multistakeholder framework for cybersecurity capacity building. There are signs that the international development community itself is moving in this direction (Horner Citation2020).

In this proposed framework, the capacity building community is drawn from several parent communities, each with their own higher-level goals (e.g. crime reduction, freedom online, security, development, etc.). The cyber capacity building activities of each parent community share the proximate objective of developing cyber capacities, but in the service of the higher-level goals of their own community. Increasingly, those in the cybersecurity capacity building field are recognising the potential for activities to contribute to sustainable development goals, but not all activities do. Because the framework is multidirectional, there is no constraint on the permutations of state and non-state actors who can work together, nor on the directions in which knowledge, skills and resources can be transferred. The framework does not inherently divide states or non-state actors into ‘givers’ and ‘takers’ and recognises the many different forms that contributions to, and benefits from, an activity can take.

Among the definitions in the literature, Pawlak’s umbrella concept is compatible with this proposed framework and has the benefit of being more comprehensive than those of the EU or Barbero. Building upon Pawlak’s own definition, this paper proposes the following refinement: International cybersecurity capacity building is an umbrella concept for all types of activity in which individuals, organisations or governments collaborate across borders to develop capabilities that mitigate risks to the safe, secure and open use of, and relationship with, the digital environment.

This definition seeks to:

Be clear that the scope is international capacity building, not domestic.

Describe the nature of the activity rather than the many possible motivations and aims behind it.

Use a central definitional concept – risk mitigation – that could apply to all types of cybersecurity capacity building.

Allow for the capacity building to occur between any countries, regardless of their development status.

Recognise the broad range of actors and stakeholders involved in capacity building.Footnote7

Take a positive approach, based upon security for rather than security from.

Recognise that some citizens are not direct users of ICT, but are nonetheless affected by it.Footnote8

Signpost the importance of access and rights, which must be protected as security is strengthened.Footnote9

As far as possible, use terminology the public will understand.Footnote10

The OEWG’s definition and framework of cybersecurity capacity building

Having discussed several example definitions and proposed an alternative, we will consider the definition and framework emerging from the latest round of UN negotiations. As before, we will use the OEWG’s final report of March 2021.

The OEWG report does not contain an explicit definition of cybersecurity capacity building. However, there are several sentences in the opening paragraphs of its capacity building section from which we can infer the elements of the definition or framework underlying the report. The report says:

Capacity-building helps to develop the skills, human resources, policies, and institutions that increase the resilience and security of States so they can fully enjoy the benefits of digital technologies … . Ensuring an open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful ICT environment requires effective cooperation among States to reduce risks to international peace and security. Capacity-building is an important aspect of such cooperation and a voluntary act of both the donor and the recipient. (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021, 8)

We can identify several positive features in this: it is built upon a description of the nature of the activity, rather than the actors’ motivations; it takes the positive approach of describing security for, rather than security from; it looks beyond security to an ‘open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful ICT environment’; and it uses simple, jargon-free language. However, this paper recommends two improvements for future updates.

First, the report’s implied definition and framework of cybersecurity capacity building are state-centric. The role of non-state actors is acknowledged elsewhere in the report, but here where the nature and benefits of capacity building are described, they are overlooked. The report instead focuses upon the ‘security of States’ and cooperation ‘among States’. This is a missed opportunity as the report itself noted that COVID-19 ‘highlighted the necessity of … maintaining a human-centric approach’ (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021, 2).

Second, the description of capacity building starts out by helpfully placing all states on an equal footing. There is no distinction implied between developed and developing countries when it says ‘capacity-building helps … the security of States’, and when it encourages ‘co-operation among States’. However, the report then puts cybersecurity capacity building within the framework of ‘the donor and the recipient’: a distinction it uses twice (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021, 9). In the same section, the report says that capacity building should be aimed at facilitating the ‘genuine involvement of developing countries in relevant discussions and fora and strengthening the resilience of developing countries in the ICT environment’ (emphasis added). The report further notes the ‘value of South–South, South–North, triangular, and regionally focused cooperation’. This overlooks North–North cooperation and is rooted in a North/South, developed/developing framing of capacity building, rather than the multidirectional model this paper proposes.

Capacity building’s three-dimensional relationship to norms and confidence building measures: enabler, instance and dependent

The OEWG’s 2021 report, the GGE reports and the literature agree that capacity building plays an important enabling function for norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace and confidence building measures (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021, 8). Homburger argues that ‘international norms presuppose the capacity of states to implement them. Therefore, capacity building arises as a necessary tool for the implementation of those norms as well as to bridge the inequalities in ICT development’ (Homburger Citation2019, 226). However, the relationship between capacity building norms and CBMs is more complicated than this. Capacity building can enable norms and CBMs of state behaviour in cyberspace, but it could also be a norm of state behaviour and a CBM, and finally it is developing norms for its own field.

Cybersecurity capacity building would be a norm of state behaviour in cyberspace if states agreed that all responsible governments should engage in it, where the opportunity and need arises, and where resources allow. I believe this could be agreed. The norms the UNGGE agreed in 2015 already include that ‘states should cooperate to increase stability and security in the use of ICTs and to prevent harmful practices’ and capacity building is a globally endorsed form of cooperation.

Cybersecurity capacity building would be a confidence building measure if the very act of collaborating to implement joint projects could build confidence and trust, which there is evidence that it can (Herbert Citation2014, 5). Importantly, it is not just any project that can serve a CBM function. Design matters, including the good practice principle that the project should have an equal impact upon all parties involved, which is a feature missing from most projects at the moment (Mason and Siegfried Citation2013, 76).

The cyber capacity building community has norms of responsible behaviour, but they are almost exclusively referred to as principles. Nonetheless, they serve the same function of defining guidelines and expectations for how capacity building actors should behave.

Ideally, the three dimensions of the relationship would connect to form a virtuous circle. More actors would engage in the capacity building if it were acknowledged as the responsible thing within a norms framework and signposted as one of the available tools for building confidence. In turn, the capacity building they engage in would be more effective if the field had its own globally agreed principles or norms. Some of this better-supported and better-delivered capacity building would be used to enable the other norms of responsible behaviour in cyberspace and CBMs. If this could be demonstrated to be effective, then it would in turn attract more actors to engage and the circle would be continued.

Principles for cybersecurity capacity building

The recent UN negotiations made four contributions to cybersecurity capacity building: they raised the profile of capacity building; they encouraged states to support and participate in it; they advanced the adoption of a principles-based approach; and they proposed further processes – another Open-Ended Working Group until 2025 and a possible Programme of Action – that have the potential to assist capacity building in the future. It is too soon to evaluate the impact of the first two of these contributions and the future UN processes have still to be defined. Therefore, this paper will consider the OEWG’s contribution to principles and provide recommendations on the next steps.

The OEWG 2021 report’s contribution to a principles-based approach to capacity building is best considered within the context of relevant literature and preceding initiatives. The literature makes two strong arguments for cybersecurity capacity building to adopt a principles-based approach on the grounds of efficacy and the avoidance of harm. The case from efficacy is made by Hohmann, Pirang, and Benner (Citation2017) who recommended five principles that would improve cybersecurity capacity building: coordination and cooperation; integration of cybersecurity and development expertise; ownership by the recipient-country; sustainability of efforts; and continued and mutual learning. The argument from harm is made by Pawlak and Barmpaliou, who argued that a normative framework of principles would provide checks and balances that reduce the risk of projects developing cyber capacities that are later misused (Pawlak and Barmpaliou Citation2017). They also argue that adopting a principles-based approach would place cybersecurity capacity building within the international development tradition, which would improve efficacy.

The work of the international development community to negotiate and implement principles provides a reference point, precedent and source of lessons (Pawlak and Barmpaliou Citation2017, 139). From 2003 to 2011, the development community held a series of High-Level Fora on Aid Effectiveness. At the last of these meetings in Busan, the community agreed a transformative set of principles, concrete actions, monitoring mechanisms and an ongoing dialogue process to maintain momentum. This Busan Partnership for Effective Development contains four key principles: ownership of development priorities by developing countries; focus on results; promotion of inclusive development partnerships; and building openness, trust and mutual respect.

Other parent communities of cybersecurity capacity building also have relevant lessons for negotiating and applying principles. These include:

the TREVI working groups process for advancing international policing cooperation;

international regime theory from security studies;

the governance bodies of the technical layers of the internet (e.g. ICANN, IEEE, IETF);

initiatives to coordinate multistakeholder principles for internet governance (e.g. the World Summit on the Information Society process, Internet Governance Forum and NETmundial);

digital access initiatives, such as the UN Secretary-General’s Roadmap on Digital Cooperation; and, of course,

efforts to agree on norms and CBMs for stability in cyberspace, such as the GGE, OEWG, OECD CBMs, Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace, Global Conference on Cyberspace and the Paris Call.

Prior to the latest round of UN Negotiations, parts of the cybersecurity capacity building community were already aware of the benefits of a principles-based approach and had taken the first steps in adopting one. In 2015, the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise included values and principles within its founding documents, and in 2017, it further elaborated these in its Delhi Communiqué on a GFCE Global Agenda for Cyber Capacity BuildingFootnote11 (Global Forum on Cyber Expertise Citation2017). The Delhi Communiqué contains a dozen principles, four of which are explicitly inspired by those in the Busan Partnership for Effective Development: national ownership of capacity development priorities; focus on sustainable results; partnerships; and trust, transparency and accountability. The Delhi Communiqué now forms the foundation for the GFCE’s coordination and knowledge-sharing work.

In 2018, the European Union agreed on a detailed set of cybersecurity capacity building principles and a principles-based approach for its own projects (Council of the European Union Citation2018). This, too, reaffirmed the Busan principles. It then augmented them by establishing that the EU’s cyber diplomacy principles – for example, open access to the internet for all – would also apply to its capacity building activities.

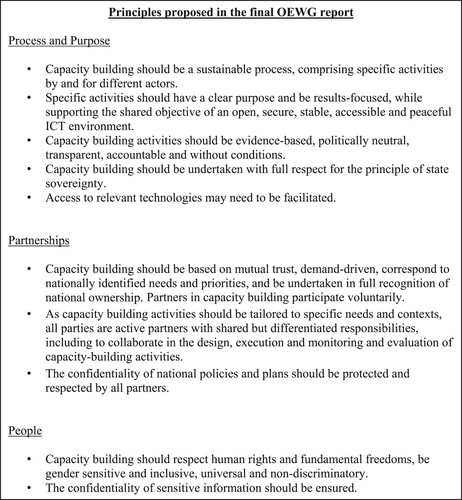

Against this backdrop, the OEWG has proposed its own set of 10 principles () (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021). All four of the Busan principles are reflected within these, although the role of non-government actors and multistakeholderism could be made more explicit, as they are in the GFCE’s Delhi Communiqué.

In assessing the OEWG’s proposed principles, we can consider what they miss out and what they have included that is not contained within the GFCE or EU principles. Starting with omissions, the OEWG report has not incorporated three principles proposed by Hohmann et al: coordination and cooperation; integration of cybersecurity and development expertise; and continued and mutual learning. All three of these are positively referenced elsewhere in the OEWG report, but not included in the list of principles.

Of the three principles, Hohmann et al. proposed, coordination has the strongest claim to being added to the OEWG’s list. The need for better coordination is a recurring theme in the literature (Muller Citation2015; Hohmann, Pirang, and Benner Citation2017; Pawlak and Barmpaliou Citation2017; Hameed et al. Citation2018) and was one of the three key findings from the GFCE’s 2020 Pacific meeting (Lagakali and Aitken Citation2020). Furthermore, it was included as a principle in the second pre-draft of the report (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2020), but not in the final version.

Turning to what new principles the OEWG has proposed, there are three innovations to consider. First, the OEWG has made explicit within its principles the goal of an open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful ICT environment, and the values of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, gender sensitivity, inclusion and non-discrimination. This contrasts with the GFCE’s decision to set out its goals, values and principles separately in the Delhi Communiqué.

Second, the OEWG has added principles regarding the protection of confidential national plans and the potential need to facilitate access to technology. While the latter is closer to an observation than a principle, neither should raise concerns in the wider cyber capacity building community.

Third, the OEWG has proposed adding a principle of respect for state sovereignty. This has been imported from the OEWG’s work on the norms of state behaviour in cyberspace. However, the challenging behaviours affecting stability in cyberspace are not the same as those affecting cybersecurity capacity building. Introducing a principle of state sovereignty implies that there has been a significant problem with states using capacity building to violate state sovereignty in the past. Without evidence of this, the principle could create more difficulties than it solves. It implies there is a problem where there may be none and will cause concern among the wider cyber capacity building community regarding how some states intend to interpret this assertion of their sovereignty in a multistakeholder field.

The OEWG’s decision to omit some previously proposed principles, while including at least one that is arguably unnecessary, creates a need to consult more widely if their proposal is to receive broad assent within the cyber capacity building community. There is also a need to agree on what these principles mean in practice and how their implementation should be supported and measured. This could be achieved through a process of communication, consultation, content generation and consolidation.

Communication and consultation on the principles

The OEWG process has broadened the number of states committing to principles of cybersecurity capacity building from the 59 that have endorsed the GFCE’s Delhi Communique to all UN members.Footnote12 That is a significant achievement, but it does not include non-government actors. Some non-government actors have already endorsed the GFCE’s principles, and some participated in consultation meetings around the OEWG process, but that still leaves a large gap in multistakeholder engagement and buy-in. Given the importance of non-state actors in capacity building, any principles should have broad, multistakeholder support.

The first step in broadening the support for new principles, and raising awareness of them, could be a communication and consultation campaign. This is something that the UN has expertise in, but it could be supported and delivered by a wide range of actors, including those who have already organised multistakeholder events around the OEWG process.

Presenting the outreach as an opportunity to provide feedback, and a consultation, implies that there is scope for suggestions and perspectives to be acted upon in some future iteration of the principles. This brings us to content development and consolidation.

Content for the principles

One lesson from the Busan Partnership is that agreeing on high-level principles is not the end of the process. Principles have a better chance of being implemented when they have content beneath the headline. The community needs to know what it means to implement the principle in practice and how its implementation can be measured.

Content should be developed for all the OEWG principles, but the one I believe would most benefit from it is the second: ‘specific activities should have a clear purpose and be results-focused while supporting the shared objective of an open, secure, stable, accessible and peaceful ICT environment’ (United Nations Open-Ended Working Group Citation2021, 8). The OEWG report already provides some insight into what the ‘shared objective’ might consist of, through its examples of cyber capacity building projects. The GFCE’s Delhi Communiqué goes further by breaking down the types of national cyber capacity that all countries should have, and which projects could support.Footnote13 However, neither has described what success in achieving the objective would look like and how it would be measured.

During the OEWG negotiations, a proposal came from France, Egypt and 41 other countries that would move the field closer to having a more detailed understanding of the shared objective. The proposal was for a UN Programme of Action that would, inter alia, define the most urgent capacity building needs (France, Egypt et al. Citation2020, 2). This would require both defining the needs the field is addressing and prioritising them for urgency.

In addition to defining its objectives and metrics, the field of cyber capacity building should establish the current baseline of relevant conditions and capacity. Only by comparing the shared objectives to a baseline assessment can we know how much capacity building is needed to reach it and prioritise efforts.

Research ICT Africa’s submission to the OEWG process suggested that national capacity assessment models could provide such baseline information (Research ICT Africa Citation2019, 5). These models also provide a yardstick against which progress in capacity building can be measured at both the programme and global agenda level. Some capacity building programmes, such as the UK’s Digital Access Programme (DAP), are already planning and evaluating multi-year capacity building partnerships with countries using these assessments.

With better-defined objectives, baselines and measures of progress, the capacity building community can produce a better evidence base and results-based narrative to attract support and investment, including from communities such as international development, where these things are preconditions for programmes (Pawlak and Barmpaliou Citation2017). The Global Cybersecurity Capacity Centre is already using the evidence they have collected from the application of their national capacity maturity model to measure the positive impacts of increasing cybersecurity capacity for end-users of ICTs (Dutton et al. Citation2019) and identify which interventions work (Hameed et al. Citation2018).

Developing options for the content of the principles and considering the feedback from the communication and consultation campaign would require research and dialogue. This need not happen through a single mechanism and could occur in parallel processes. Within the UN, a new phase of the Open-Ended Working Group will run from 2021 to 2025, as per UN Resolution 75/240 (United Nations General Assembly Citation2021). The OEWG final report also made reference to the proposal for a UN Programme of Action. Either of these could develop content for the cybersecurity capacity building principles, drawing lessons from other areas of UN work with significant multistakeholder involvement such as the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space or the Internet Governance Forum. However, content could also be developed in parallel processes outside the UN, as it was for the norms and confidence building measures for stability in cyberspace. Such processes could include regional organisations defining what the principles mean for their own region and the use of multistakeholder collaborations, as occurred with the Global Commission on Stability in Cyberspace and the Global Commission on Internet Governance. The Global Forum on Cyber Expertise also has a role in continuing the development of the principles they agreed in 2017, taking account of the OEWG recommendations.

Consolidation

After the communication, consultation and content generation, a process of consolidation would be needed to draw together the parallel strands of work that had been underway. The same has occurred with norms and confidence building measures in cyberspace, with the UN Group of Government Experts, and more recently the Open-Ended Working Group, acting as a forum for this consolidation. Each new round of the UN GGE, and more recently of the OEWG, has been an opportunity for governments to discuss the ideas emerging in these other processes and adopt those that they agree upon. The UN could similarly be a forum for converging and consolidating progress in developing the principles of cyber capacity building. However, it is not the only option.

The foreign policy community has held several international conferences to advance stability in cyberspace that supported cyber capacity building and could provide an alternative model for a principles consolidation process. These include the 2015 Global Conference on Cyberspace in The Hague, which launched the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise and the 2017 Global Conference on Cyberspace in Delhi, at which the principles in the Delhi Communiqué were agreed. The advantage of this model is that it lends itself to a more multistakeholder approach. However, any future conference would need to ensure a wider representation of states. Furthermore, the conference would need a preparatory process that did the work of consolidating the earlier consultation and content generation workstreams. The conference event itself only cements the consolidation and resolves any outstanding differences of view at a more senior level.

Conclusion

Cybersecurity capacity building is a relatively young field of international cooperation, with contested parent concepts. Many of the commonly used definitions for it are built upon a developed-developing, donor-beneficiary framework. A more accurate definition would focus on the nature of cybersecurity capacity building activity and advance a framework of multidirectional, multistakeholder partnerships. Such a definition and framework would also happen to be of more use to the ongoing negotiations on cyberspace norms and confidence building measures at the United Nations.

Although the cybersecurity capacity building community should make less use of older international development frameworks, it should make much more use of development’s latest good practice and the lessons learned. Especially in four areas that will be critical to the future of capacity building: agreeing principles; promoting real partnerships; defining shared objectives; and improving coordination.

The 2021 report of the UN Open-Ended Working Group advanced the development of principles of cybersecurity capacity building begun by the Global Forum on Cyber Expertise. This paper recommends a process of communication, consultation, content generation and consolidation to finalise a principles framework that is actionable and measurable. Although all principles are important, any principle related to the field’s objectives is especially so. Unpacking the detail of what the OEWG report described as a shared objective and agreeing on how to prioritise national capacity building needs would be a significant step forward in giving the field a compelling narrative to attract investment and focus efforts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Collett

Robert Collett is a researcher, adviser and trainer specialising in cybersecurity capacity building. He is a Chatham House Associate Fellow and founder of Developing Capacity Ltd. From 2019 to 2020, he was the UK’s first seconded senior adviser to the Global Forum of Cyber Expertise (GFCE). Prior to this, he ran, and grew threefold, the UK’s international cyber security capacity building programmes. He has a 17-year track record leading programmes and policy initiatives as a UK diplomat, working at the intersection of foreign policy, security and development. During this period, he led the strategic communications for NATO’s Provincial Reconstruction Team in Helmand and managed a series of challenging projects from de-mining to countering violent extremism and cyber security.

Notes

1 The GGE consists of 25 national experts, while the OEWG is open to all interested states. The OEWG’s mandate covers a slightly wider set of issues, including whether to establish a regular institutional open-ended dialogue within the UN.

2 There are also alternative orthographies for both parts of the term: cybersecurity, cyber-security and cyber security; capacity-building and capacity building.

3 Homburger cited the following sources: EUISS (Citation2013), Klimburg and Zylberberg (Citation2015, 7) and Schia (Citation2018).

4 This formulation originated in 2014 as Pawlak’s definition of cybersecurity. It was then repurposed by Hohmann et al. as a definition of cybersecurity capacity building (Hohmann, Pirang, and Benner Citation2017) and later adopted by Hameed et al. (Citation2018) and Homburger herself.

5 Examples of previous North–North capacity building activities include: cybercrime exercising; personnel secondments; strengthening universities and research programmes; student scholarships; sharing threat intelligence; providing advice and training on technical skills (from incident response to threat analysis); advisory projects on standards schemes; and sharing public awareness campaign material.

6 The World Bank’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) provides an authoritative categorisation for economic development. The only categorisation system covering all countries for cybersecurity is the ITU’s Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI). The GCI is considerably behind the DAC in respect of its authority, its resources, the robustness of its model and the quality of evidence it can draw on.

7 The definition refers to ‘individuals, organisations and governments’, where organisations should be understood to include, inter alia, companies, regional economic communities, international organisations, academia and civil society. The definition does not use the terms multistakeholder or actors as these are less easily understood by non-specialists.

8 This is why the definition says ‘ … use of, and relationship with … ’

9 The definition does this by using the phrase ‘safe, secure and open’ (my italics).

10 ‘Digital environment’ is used in the place of cyberspace for this reason.

11 Signed by 41 countries and 28 international organisations and companies.

12 All members of the GFCE have endorsed the Delhi Communiqué and its principles, either at the time it was issued in 2017 or as a prerequisite for joining subsequently. The 59 national members are included in the membership list here: https://thegfce.org/member-overview/.

13 The five thematic categories of capacity are: strategy and policy; incident response and critical information infrastructure protection; countering cybercrime; culture and skills; and standards. These are further broken down by GFCE working groups, who coordinate and share knowledge around each theme.

References

- Akhgar, Babak, Andrew Staniforth, and Francesca Bosco. 2014. Cyber Crime and Cyber Terrorism Investigator’s Handbook. Waltham, Massachusetts: Syngress.

- Amazouz, Souhile. 2016. “African Diplomats Train to Stand Their Ground in Cyber Negotiations – Global Forum on Cyber Expertise.Pdf.” The GFCE. Accessed June 20 2016. https://thegfce.org/african-diplomats-train-to-stand-their-ground-in-cyber-negotiations/.

- Barbero, Fabio, and Nils Berglund. 2021. “Cybersecurity Capacity Building and Donor Coordination in the Western Balkans.” https://www.dcaf.ch/sites/default/files/imce/Events/CybersecurityConference_DiscussionPaperPanel%203_CapacityBuildingDonorCoordination.pdf.

- Brunner, Isabella. 2020. “1998–UNGA Resolution 53/70 ‘Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security’and Its Influence on the International Rule of Law in Cyberspace.” Austrian Review of International and European Law Online 23 (1): 183–200.

- Calandro, Enrico, and Nils Berglund. 2019. “Unpacking Cyber-Capacity Building in Shaping Cyberspace Governance: The SADC Case.” In GIGAnet annual symposium. Berlin. https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/33_Calandro_Berglund_Unpacking-Cyber-Capacity-Building-1.pdf.

- Connelly, Steve. 2007. “Mapping Sustainable Development as a Contested Concept.” Local Environment 12 (3): 259–278.

- Contu, Alessia, and Emanuela Girei. 2013. “NGOs Management and the Value of ‘Partnerships’ for Equality in International Development: What’s in a Name?”: Human Relations, July. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713489999.

- Council of the European Union. 2018. “EU External Cyber Capacity Building Guidelines - Council Conclusions (26 June 2018).” 10496/18. Brussels: European Union. https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10496-2018-INIT/en/pdf.

- Cybil Portal. 2021. “Charts - Cybil Portal.” Cybil Portal. Accessed April 19 2021. https://cybilportal.org/trends-and-data/.

- Cybil Portal. n.d. “Capacity Building Workshops on International Cyber Negotiations (UNGGE and OEWG).” Cybil Portal. n.d. https://cybilportal.org/projects/capacity-building-workshops-on-international-cyber-negotiations-ungge-and-oewg/.

- Dunn Cavelty, Myriam, and Andreas Wenger. 2020. “Cyber Security Meets Security Politics: Complex Technology, Fragmented Politics, and Networked Science.” Contemporary Security Policy 41 (1): 5–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1678855.

- Dutton, William H., Sadie Creese, Ruth Shillair, and Maria Bada. 2019. “Cybersecurity Capacity: Does It Matter? (2019).” Journal of Information Policy 9: 280–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.9.2019.0280.

- ENISA, Charles Brookson, S. Cadzow, R. Eckmaier, J. Eschweiler, B. Gerber, A. Guarino, K. Rannenberg, J. Shamah, and S. Gorniak. 2015. “Definition of Cybersecurity-Gaps and Overlaps in Standardisation.” Heraklion, ENISA.

- EUISS. 2013. “Capacity Building in Cyberspace: Taking Stock | European Union Institute for Security Studies.” Accessed November 19 2013. https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/capacity-building-cyberspace-taking-stock.

- European Commission, Patryk Pawlak, Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development. Institute for Security Studies. Paris. 2018. Operational Guidance for the EUs International Cooperation on Cyber Capacity Building.

- Fengler, Wolfgang, and Homi J. Kharas. 2010. Delivering Aid Differently: Lessons from the Field. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- France, Egypt et al. 2020. “The Future of Discussions on ICTs and Cyberspace at the UN.” https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/joint-contribution-poa-future-of-cyber-discussions-at-un-10-08-2020.pdf.

- Global Forum on Cyber Expertise. 2017. “The Delhi Communiqué on a GFCE Global Agenda for Cyber Capacity Building.” Global Forum on Cyber Expertise. https://thegfce.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/DelhiCommunique.pdf.

- Hameed, Faisal, Ioannis Agrafiotis, Carolin Weisser, Michael Goldsmith, and Sadie Creese. 2018. “Analysing Trends and Success Factors of International Cybersecurity Capacity-Building Initiatives.” https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:50e9c5aa-4f3d-40f0-a0a0-ff538b735291.

- Herbert, Siân. 2014. “Lessons from Confidence Building Measures.” GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a089a4e5274a31e00001c2/hdq1131.pdf.

- Hitchens, Theresa, and Nancy W. Gallagher. 2019. “Building Confidence in the Cybersphere: A Path to Multilateral Progress.” Journal of Cyber Policy 4 (1): 4–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2019.1599032.

- Hohmann, Mirko, Alexander Pirang, and Thornston Benner. 2017. “Advancing Cybersecurity Capacity Building: Implementing a Principle-Based Approach.” Global Public Policy Institute (GPPi). https://www.gppi.net/media/Hohmann__Pirang__Benner__2017__Advancing_Cybersecurity_Capacity_Building.pdf.

- Homburger, Zine. 2019. “The Necessity and Pitfall of Cybersecurity Capacity Building for Norm Development in Cyberspace.” Global Society 33 (2): 224–242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2019.1569502.

- Horner, Rory. 2020. “Towards a New Paradigm of Global Development? Beyond the Limits of International Development.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (3): 415–436. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519836158.

- International Telecommunications Union. 2002. “Final Acts of the Plenipotentiary Conference (Marrakesh, 2002).” http://search.itu.int/history/HistoryDigitalCollectionDocLibrary/4.17.43.en.100.pdf.

- Klimburg, Alexander, and Hugo Zylberberg. 2015. “Cyber Security Capacity Building: Developing Access.” https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/52122747.pdf.

- Lagakali, Cherie, and Klée Aitken. 2020. “The GFCE Meets the Pacific.” Organisation Blog. Pacific Online. 16 February 2020. https://pacificonline.org/portfolio-item/the-gfce-meets-the-pacific/.

- Mason, Simon JA, and Matthias Siegfried. 2013. “Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) in Peace Processes.” In Managing Peace Processes: Process Related Questions. A Handbook for AU Practitioners. Vol. 1. https://css.ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/center-for-securities-studies/pdfs/AU_Handbook_Confidence_Building_Measures.pdf.

- Morgus, Robert. 2018. Securing Digital Dividends: Mainstreaming Cybersecurity in International Development. New America.

- Muller, Lilly Pijnenburg. 2015. “Cyber Security Capacity Building in Developing Countries: Challenges and Opportunities.” 3. NUPI Report. NUPI. https://nupi.brage.unit.no/nupi-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/284124/NUPI+Report+03-15-Muller.pdf?sequence=3.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 2002. “Vulnerability of the Interconnected Society.” https://www.nato.int/science/publication/nation_funded/doc/262-VIS%20Final%20Rep-Oct%202002.pdf.

- OSCE Permanent Council. 2016. “Decision No.1202 OSCE Confidence-Building Measures to Reduce the Risks of Conflict Stemming from the Use of Information and Communications Technologies.” https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/d/a/227281.pdf.

- Pawlak, Patryk. 2014. Riding the Digital Wave: The Impact of Cyber Capacity Building on Human Development. EUISS Reports 21. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS). https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/riding-digital-wave-%E2%80%93-impact-cyber-capacity-building-human-development.

- Pawlak, Patryk. 2016a. “‘Confidence-Building Measures in Cyberspace: Current Debates and Trends’. International Cyber Norms: Legal.” Policy & Industry Perspectives, 129–153.

- Pawlak, Patryk. 2016b. “Capacity Building in Cyberspace as an Instrument of Foreign Policy.” Global Policy 7 (1): 83–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12298.

- Pawlak, Patryk, and Panagiota-Nayia Barmpaliou. 2017. “Politics of Cybersecurity Capacity Building: Conundrum and Opportunity.” Journal of Cyber Policy 2 (1): 123–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2017.1294610.

- Research ICT Africa. 2019. “Bridging the Cyber Norms Debate with Evidence.” Discussion Paper. Research ICT Africa. https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Discussion-Paper-OEWG-Intersessional-Meeting.pdf.

- Schia, Niels. 2018. “The Cyber Frontier and Digital Pitfalls in the Global South.” Third World Quarterly, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1408403.

- United Nations. 2002. ‘United Nations System Support for Capacity Building’. E/2002/58. New York: United Nations. https://www.un.org/esa/documents/ecosoc/docs/2002/e2002-58.pdf.

- United Nations General Assembly. 1999. UNGA Resolution 53/70 Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security. UN Doc A/RES/53/70.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2013. Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security. UN Doc A/68/98*.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2015. Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security. UN Doc A/70/174*. https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/174.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2021. UNGA Resolution 75/240 Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security. UN Doc A/RES/75/240. https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/75/240.

- United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. 2019. “Regional Consultations Series of the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing Responsible State Behaviour in Cyberspace in the Context of International Security.” https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/collated-summaries-regional-gge-consultations-12-3-2019.pdf.

- United Nations Open-Ended Working Group. 2020. “Second ‘Pre-Draft’ of the Report of the OEWG on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security.” UN. https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/200527-oewg-ict-revised-pre-draft.pdf.

- United Nations Open-Ended Working Group. 2021. “Final Substantive Report of the Open-Ended Working Group on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security.” https://front.un-arm.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Final-report-A-AC.290-2021-CRP.2.pdf.

- Wilén, Nina. 2009. “Capacity-Building or Capacity-Taking? Legitimizing Concepts in Peace and Development Operations.” International Peacekeeping 16 (3): 337–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13533310903036392.