Abstract

Background

Viral hepatitis is a leading cause of mortality globally, comparable to that of HIV and TB. Most hepatitis deaths are related to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) associated with chronic hepatitis B and C infections. To examine the progress towards the elimination goals set in the global health sector strategy for viral hepatitis, we aimed to assess the impact of mortality-indicative morbidity.

Methods

We retrieved inpatients and day cases hospital discharges data from the Eurostat hospital activities database, and analysed ICD-10 and ICD-9 specific codes related to primary HCC and non-alcohol related cirrhosis registered by European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) countries and United Kingdom (UK) for 2004 to 2015.

Results

In 2015, 20 countries (45.7% of total EU/EEA/UK population) reported 13,236 (Range 0–6294) day cases and 36,012 (4–9097) inpatients discharges of HCC. Romania, Croatia, Luxembourg and UK reported increasing day cases discharge rates between 2004 and 2015; while HCC inpatients discharge rates increased overall during this period. There were 13,865 (0–5918) day cases and 56,176 (3–29,118) inpatients discharges reported for cirrhosis across the 20 countries in 2015. Over the 12 years, day cases discharge rates for cirrhosis increased in Romania, Croatia and UK. Though higher than for day cases, cirrhosis inpatients discharge rates remained stable.

Conclusions

The hospital burden of HCC and cirrhosis is high, with considerable inpatient load including sustained increasing trends in HCC discharge rates. Further interpretation in light of local health system contexts, and more robust harmonised data are needed to better understand the impact of the viral hepatitis epidemic in the region.

Introduction

Viral hepatitis is a leading cause of death from infectious disease in the world, with about 1.46 million deaths per year, a figure comparable to that of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis (TB), but only recently recognised as public health priority by the global community [Citation1,Citation2]. The World Health Organisation (WHO)’s first Global Health Sector Strategy for viral hepatitis (GHSS) adopted by the sixty-ninth World Health Assembly in May 2016, aims at eliminating hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a public health threat by 2030 [Citation1]. The strategy seeks reductions of 30% in incidence of HBV/HCV and 10% of mortality by 2020, subsequently achieving 90% and 65% reductions in HBV/HCV incidence and mortality by 2030, respectively.

Approximately 96% of viral hepatitis deaths are due to late health outcomes of chronic HBV and HCV infections including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [Citation3]. In the European Union (EU), European Economic Area (EEA) and United Kingdom (UK) where an estimated 4.7 and 3.9 million people have chronic HBV and HCV infection respectively [Citation4], just under 300,000 deaths were estimated to be attributable to HBV and HCV between 2010 and 2015 [Citation5]. Recent reports, however, suggest that mortality from liver cancer continues to increase across most European countries [Citation5–7]. In order to have a better understanding around the progress towards the elimination targets and to provide countries with information on the impact of the viral hepatitis epidemics, data on morbidity should also be considered.

Chronic HBV and HCV infections are major risk factors for chronic liver disease, but chronic liver disease can also be caused by a range of other factors, including alcohol use, obesity, immune and genetic disorders. Estimates of the prevalence of cirrhosis from modelling studies show considerable variation between countries, with most cases in Europe caused by alcohol use and viral hepatitis infection [Citation7]. The relative contribution of these risk factors to cirrhosis also varies between countries with alcohol the most important contributor in Western and Northern European countries and viral hepatitis, especially hepatitis C, a greater factor in Southern and Eastern European countries [Citation7].

Data on complications (HCC, liver cirrhosis and HCC-liver cirrhosis co-morbidity) associated with newly diagnosed cases of hepatitis B and C across the 30 EU/EEA countries and UK are collected through The European Surveillance System (TESSy) coordinated by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). However, disease specific data on outcomes reported to TESSy are largely incomplete [Citation8,Citation9], and this limits any analysis or interpretation of the data. In addition, the data only represent cases that are diagnosed, notified to national authorities and then reported on to ECDC, and provide only a limited overview of the morbidity associated with the infections.

To better understand the burden of disease associated with chronic hepatitis in the region, the current study explored and examined the most recent hospital data on mortality-associated complications of HBV and HCV infections. The analysis aimed to describe and compare, the temporal and geographical trends in frequencies and rates for outpatient and inpatient hospital episodes of HCC and liver cirrhosis in EU/EEA countries and UK.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study involved a retrospective analysis of data submitted to Eurostat [Citation10] by 30 EU/EEA countries and UK.

Data and data sources

Data available as of 11 January 2018 in the Eurostat hospital activities database [Citation10], on day cases and inpatients discharges of primary HCC and liver cirrhosis for the period 2004–2015 were considered. A hospital discharge is defined as the formal release of a patient from a hospital after a procedure or course of treatment (episode of care), and occurs when treatment has been finalised, a patient signs out against medical advice, transfers to another health care institution or care ends because of death. A discharge can refer to inpatients or day cases. An inpatient is a patient who is formally admitted (‘hospitalised’) to an institution for treatment and/or care and stays for a minimum of one night or more than 24 h in the institution/hospital providing inpatient care. Day case comprises of day care medical and paramedical services (episode of care) delivered to patients who are formally admitted for diagnosis, treatment or other types of health care with the intention of discharging the patient on the same day [Citation11]. The dataset was in an aggregated format without unique identifiers, and excluded demographic parameters like age and sex to allow for linkage. Therefore, by definition and data format, each hospital discharge is not associated with one unique patient.

In the database, discharge diagnoses were classified according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10), 9th revision (ICD-9) or the International Shortlist for Hospital Morbidity Tabulation (ISHMT) (). Data relating to alcoholic liver cirrhosis of the liver i.e. K70.3 (ICD-10), 5710_5713 (ICD-9) and 1115 (ISHMT), were specifically excluded.

Table 1. Classification codes for HCC and cirrhosis considered for inclusion in the analysis.

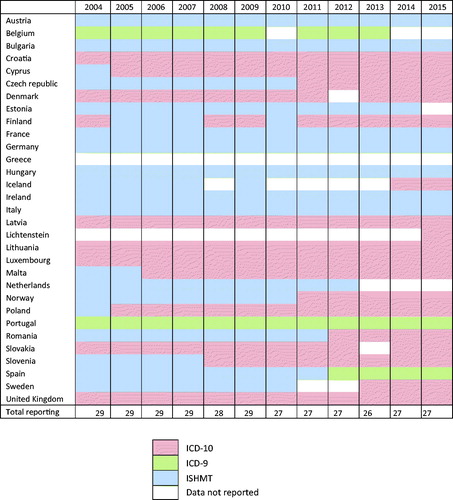

presents the reporting patterns and classifications used by country and year for this 12-year period. Thirty EU/EEA countries and UK reported hospital data related to HCC and cirrhosis to Eurostat between 2004 and 2015. While twenty-two countries reported consistently, Lichtenstein reported only for 2015 and no data were available for Greece during the entire period. Countries reported more using the ICD-10 classification and less of the ISHMT over time; ten countries and one country changed from ISHMT to ICD-10 and to ICD-9, respectively.

Data analysis

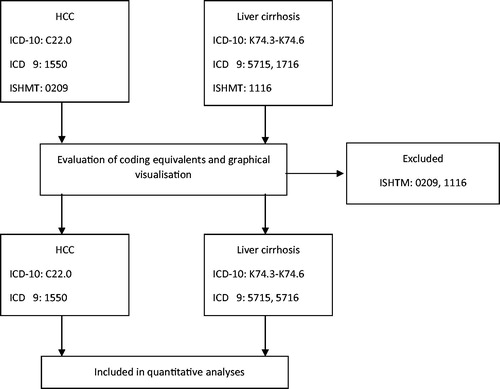

Initially, a comparative evaluation of the three different case classifications of the data (ISHMT, ICD-9, ICD-10) was undertaken to understand if the data classified using these different classifications could be considered together, or if the data must be analysed separately (). To do this, ISHMT and ICD-9 codes were mapped against ICD-10 equivalents. The original ICD-9 codes as reported by countries were converted to ICD-10 equivalents using the General Equivalence Mappings (GEM) conversion utility tool [Citation12]. We also performed backward conversion of ICD-10 codes to ICD-9 to check for differences or identify other equivalent codes. Similarly, original ISHMT codes as reported, were converted to ICD-10 equivalents using the ISHMT–Eurostat/OECD/WHO Version 2008-11-10 [Citation13].

Table 2. ICD-9 and ISHMT equivalents for: ICD10 code C22.0 – HCC and ICD-10 code K74.3-74.6 – liver cirrhosis.

Evaluation of coding equivalents and a graphical visualisation of the data (Supplementary Figure 1) indicated the breadth of the ISHMT 0209 and 1116 for both HCC and cirrhosis respectively, compared to the equivalent codes for ICD-10 and ICD-9. Data from countries reporting data using only the ISHMT classification, as well as the periods for which some countries used this classification were thus excluded from further analyses. ICD-9 was considered to have comparable case sensitivity and specificity for both HCC and cirrhosis to ICD-10 for the objectives of this study. Countries that used the ICD-9 and ICD-10 classifications were included in all analyses (Supplementary Figure 1(B, D)). Only Norway reported 4-character codes using ICD-10. The 3-character code K74 for cirrhosis used by all countries, except Norway, included all types of cirrhosis and fibrosis (excluding congenital and alcoholic fibrosis/cirrhosis), and as such, all data coded with K74.0 – K74.6 for Norway was included for better comparability. The codes selection process is summarised in .

Data management and analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (2016). Pivot tables were used to aggregate data by country and generate trends graphs. Crude rates per 100,000 population, calculated as numbers in the dataset divided by denominators available from the Eurostat population database [Citation14], were provided by Eurostat. The data format did not allow for calculation of age or gender standardised rates. Time trends in frequency and rates by country for cases of HCC and cirrhosis were assessed, and compared between countries.

Results

HCC

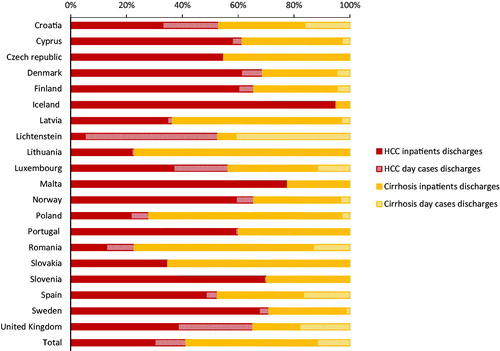

For 2015, 13,236 day cases (Range 0–6294) and 36,012 inpatients (4–9097) discharges of HCC were reported by 19 EU/EEA countries and UK (45.7% of the total EU/EEA/UK population), which equated to 5.6(0–96.3) day cases and 15.3 (7.3–29.5) inpatients discharges per 100,000 population among reporting countries (). The UK (6294), Romania (4448) and Poland (825) reported the highest numbers of day cases discharges in 2015. For inpatients discharges, the UK (9097), Spain (7467), Romania (5856) and Poland (2791) had the highest numbers. In all countries, except Liechtenstein, inpatients exceeded day cases discharges () (EU/EEA/UK day cases discharges: inpatients discharges ratio 1: 2.7 (1.3 – ∞)). In 2015, Liechtenstein (96.3), Romania (22.4), Croatia (12.5), Luxembourg (9.8) and the UK (9.7) had the highest day cases discharges per 100,000 while Romania (29.5), Finland (24.8), Croatia (20.8) and Slovenia (20.4) reported the highest rates of inpatients discharges.

Figure 3. Proportions of total HCC and non-alcohol related cirrhosis hospital discharges by country, EU/EEA and UK, 2015.

Table 3. HCC and non-alcohol related liver cirrhosis day cases and inpatients: Numbers and rates per 100,000 population of discharges by country, EU/EEA and UK, 2015.

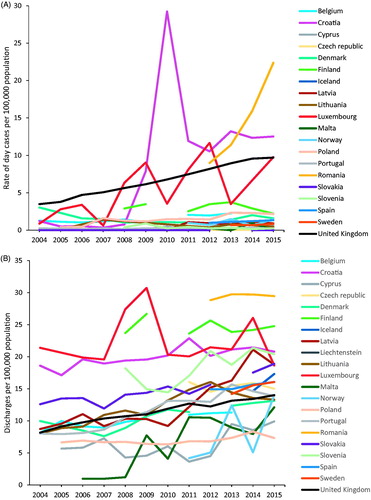

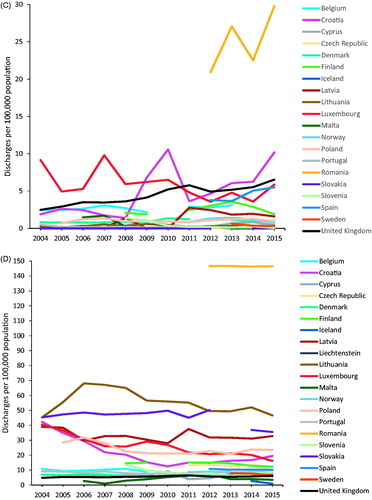

Between 2004 and 2015, the number of day cases discharges increased alongside the number of reporting countries from 2724 reported by 10 countries in 2004, to 13,236 reported by 20 countries in 2015. Inpatients discharges also increased over this period from 10,305 reported from 10 countries to 36,012 cases in 20 countries. The UK in particular, that accounted for 47.6% of day cases and 25.3% of inpatients discharges in 2015, recorded consistently sharp increases throughout the 12-year period; from 2085 to 6294 day cases (200% increase) and 4887 to 8433 inpatients discharges (72% increase). Between 2012 and 2015, the period for which data were available, the number of day cases discharges in Romania more than doubled, from 1802 to 4448 while inpatient discharges remained stable at between 5785 and 5946 per year. In the majority of reporting countries (15/20 in 2015), rates of HCC day cases remained stably below 5 per 100,000 population for the entire period between 2004 and 2015 (). However, higher and increasing trends were registered by Romania, Croatia, UK and Luxembourg. The rates of inpatients discharges increased steadily across all reporting countries overall during the 12 years (), with 55.9% increase among six countries (Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Portugal and the UK) that reported consistently during this period from 8.8 to 14.5.

Figure 4. Discharges per 100,000 population by country, EU/EEA and UK, 2004–2015. (A) HCC day cases—excluding Liechtenstein. (B) HCC inpatients. (C) Cirrhosis day cases—excluding Liechtenstein. (D) Cirrhosis inpatients.

Cirrhosis

Nineteen EU/EEA countries and UK (45.7% of the total EU/EEA/UK population) reported 13,865 (0–5918) day cases and 56,176 (3–29,118) inpatients discharges of liver cirrhosis in 2015; corresponding to 5.9 (0–29.8) day cases and 23.9 (0.9–146.5) inpatients discharges per 100,000 population, respectively (). In 2015, Romania (5981), the UK (4245) and Spain (2556) reported the highest numbers of day cases discharges. For inpatients discharges Romania (29,118), Poland (8983), Spain (4745) and the UK (3976) had the highest numbers. Inpatients exceeded day cases discharges (EU/EEA/UK day cases discharges: inpatients discharges ratio 1: 4.1 (1.9–∞)) in all countries except the UK and Liechtenstein (). Liechtenstein (83.0), Romania (29.8), Croatia (10.2) and the UK (6.5), had highest rates of day cases discharges of liver cirrhosis per 100,000 population in 2015 while Romania (146.5), Lithuania (46.7), Slovakia (35.5) and Latvia (32.8) reported the highest inpatients discharge rates.

Between 2004 and 2015, there were increases in the numbers of day cases discharges and reporting countries, from 2074 to 13,865 cases and from 10 to 20 countries, respectively. Inpatients discharges also increased from the 13,043 cases reported by 10 countries in 2004 to 56,176 cases from 20 countries in 2014. Romania, the UK and Spain registered the highest increases in day cases discharges of cirrhosis during the periods for which data were available. In the 12-year period between 2004 and 2015, day cases discharge rates of cirrhosis () were stable and below 5 per 100,000 population in most countries (14/20 countries in 2015); but with increasing trends in Romania, Croatia, the UK and Spain. Romania had exceptionally high day cases discharge rates (Range 20.9–29.8) between 2012 and 2015 when data were available. Inpatients discharge rates were stable during the reporting period (), 18/20 countries recorded rates below 40 per 100,000 in 2015, and among the six countries that reported consistently over the 12 years there was a 13.8% decrease. Romania had exceptionally high but stable inpatient discharge rates (146.3–146.7), for the period for which data were available.

Discussion

The present study examined hospital data on HCC and cirrhosis to better understand the potential impact of the viral hepatitis epidemics in the EU/EEA, as the region aims to meet the elimination targets for HBV and HCV set in the GHSS. In monitoring the progress towards the target 65% reductions in HBV/HCV related mortality, the evaluation of the burden of HCC and cirrhosis that cause most of the deaths from viral hepatitis is important, as mortality-indicative data are limited.

We found that the overall hospital burden of HCC and cirrhosis in the region was high in 2015, which when averted through HCV elimination strategies have the potential to offset hundreds of millions euros in disease-related costs for EU/EEA countries by 2035 [Citation15]. Large numbers of both inpatient and outpatient episodes were reported, with considerable variation between countries. The large burden of chronic liver diseases, including HCC and cirrhosis, in Europe is mostly attributable to alcohol use, HCV and HBV [Citation16], although the relative contributions of these conditions vary across countries [Citation17]. The HCC hospital data related to all possible causes, and we observed from our analyses that the high rates of combined hospital burden (outpatient plus inpatient discharges) reported by Luxembourg and lowest (Poland and Malta) corroborated HCC prevalence estimates for 2016 reported from the global burden of disease (GBD) study [Citation16]. Our analyses of the data for cirrhosis excluded alcoholic liver disease and we observed that the highest hospital burden in Romania, was also consistent with findings from the GBD modelling [Citation16]. Aetiologically, this observed high hospital burden in Romania could reflect the HCV (3.2%) and HBV (4.4%) prevalence estimates in the general population, identified by a recent systematic review to be among the highest in the region [Citation4]. These prevalence estimates were also similar to findings of an earlier review [Citation18]. Malta and Iceland had a relatively lower hospital burden of liver cirrhosis which also paralleled the low prevalence of liver cirrhosis in these countries found in the GBD study [Citation16].

Inpatients discharges occurred more frequently than day cases, for both HCC (2.7 times more) and cirrhosis (4.0 times more) in the majority of countries, with higher numbers and rates for hospitalised cirrhosis than HCC. In-hospital viral cirrhosis cases are reported in the literature to commonly present with life-threatening complications such as ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome; with inpatient deaths reported to occur in 16% and 18% of HBV and HCV cirrhosis patients, respectively [Citation19]. The higher occurrence of admissions, severity of illness and high mortality indicate patients with advanced disease, with substantial associated costs to healthcare systems. Indeed, one study in Valencia estimated that on average a cirrhotic and HCC patient generated annual hospital costs of 5273 Euros and 6350 Euros, respectively [Citation20]. Admissions for these conditions could, however, represent the whole spectrum of care from diagnostics, initiation of treatment to post-therapeutic monitoring and this is likely to vary between countries where policies relating to standards and practices of care may differ. This could explain why Iceland, Malta and Slovakia reported no day cases of liver cirrhosis in 2015. Differences in reimbursement payments for hospital admissions and outpatients may also be a factor accounting for the variation observed.

Cirrhosis hospitalisation rates were also higher than for HCC over the entire 12-year period in the majority of reporting countries, which probably reflects the higher burden of disease relating to cirrhosis compared to HCC [Citation7]. Owing to the chronic course of disease, the longer duration of cirrhosis leads to a higher burden. However, they remained largely stable across countries during this period, contrary to modelling studies that have forecasted an increasing burden of liver cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases [Citation7,Citation16] as well as liver cirrhosis attributable to HCV until 2030 [Citation21,Citation22]. This discrepancy may be due to general improvements in the medical care of patients with cirrhosis over the reporting period, and later on through the impact of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) programmes for HCV patients which have been rolled out in the region and found to be effective in significantly reducing hospitalisations in cirrhotic patients with HCV infection [Citation23]. Liver transplants for which cirrhotic patients would have been hospitalised, have also been stagnant during the reporting period of this study owing to donor shortages [Citation24]. Patients with viral cirrhosis, especially those with decompensated disease, are recommended to be prioritised for treatment as it improves liver function, quality of life, survival and reduces the risk of progression to HCC [Citation25,Citation26].

In comparison, the increasing trends in HCC hospitalisation rates between 2004 and 2015 across the region that we observed are consistent with the predictions from modelling studies [Citation7,Citation16]. Trends in alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes and obesity could explain part of the findings, but HBV and HCV combined, is the predominant aetiological determinant of HCC in many EU/EEA countries [Citation16]. Viral hepatitis disproportionately affects hard to reach high risk populations including people who inject drugs [Citation7] and migrants [Citation27,Citation28]; poorer access to care particularly by vulnerable populations may also explain these trends that indicate that chronic viral hepatitis patients have continued to advance to HCC. A further possible explanation for the increasing trends in HCC may relate to the continued risk of HCC following successful clearance of the virus after treatment with antiviral therapy, with the greatest impact of treatment seen in the reduction in HCV related end stage liver disease including liver cirrhosis [Citation29].

Day case hospital burden for both HCC and cirrhosis remained largely stable, except in Croatia, Romania and the UK that reported marked increases in rates. For the UK, these trends plausibly demonstrate manifestation of end stage liver disease among ageing chronically infected population, reflecting the high incidence of HCV in previous decades amidst low treatment coverage [Citation29,Citation30]. These outpatient trends may also be influenced by HCV treatment patterns in recent years following the marked increases in access to DAAs only after 2014, especially between 2017 and 2018 in the UK [Citation29]. Also based on the findings from a recent survey that as many as 72% of HCV antibody positive PWID, a marginalised population, had attended care to see a hepatologist in 2017 [Citation29], increased outpatient visits could be more likely to be observed in future hospital episode data. Such improved access to care for cirrhotic patients on an outpatient basis could also explain the sharp increases in day cases observed in Croatia and Romania, particularly in the later years of this analysis. Considering the safety, effectiveness and short-term regimen profile of DAAs and in a bid to reach marginalised communities, HCV treatment programmes have been targeted for implementation through community and outreach settings in the UK and this may also impact on future hospital burden of liver disease.

The data presented various limitations. First, while a considerable number of countries (54.3% of total EU/EEA population) that were using ISHMT and non-reporting were dropped from the analysis, a major limitation of the present study is that ICD-10 and ICD-9 diagnoses for HCC and liver cirrhosis are not disaggregated by aetiology. The data coded by ICD-10 and ICD-9 included HCC from all causes, not just viral hepatitis but this coding permitted for the exclusion of alcoholic liver cirrhosis (K70.3). The GEM tool also converts codes based solely on coding inferences, without consideration for contextual or patient information. While this suited the format of our data, it could not link cirrhosis or HCC to any underlying aetiology. Owing to the lack of a common identifier to enable linkage of discharge data to unique patients and their underlying diagnoses, it was also not possible to differentiate HBV from HCV or to relate it to other non-viral causes such as obesity and type 2 diabetes.

A further limitation is that the Eurostat numbers reported do not reflect unique patients, but rather cumulative episodes of hospital attendances and admissions; one patient could have more than one episode of care. As such, we could not deduce the number of patients per country by year considered in this analysis. This could have led to a potential overestimation of the attributable burden to HCC and cirrhosis, and biased the perception of both HCC and cirrhosis hospital ‘cases’. No case-based variables including age and gender were available in this aggregated dataset either, to perform further in-depth analyses. Another limitation is that national practices and reporting required greater consideration to understand inter-country differences in the data, but the published literature in this area was limited. Indications for hospital admissions may differ between countries; and patients in private care may not be fully reflected in the data [Citation18], with varying proportions of such patients across countries.

Though the present study’s results are confounded by overlapping aetiologies and national practices, outpatient attendance and hospital admissions do provide an overview of viral hepatitis associated morbidity because HBV and HCV patients still present to hospital with end-stage liver disease as well as for assessment and initiation on antiviral treatment when indicated in some countries. Country-specific contextual information detailing these stages along the care pathway from diagnosis to treatment as outpatient or inpatient services could have clarified our findings, but were not available.

Although available information from epidemiological studies indicates that new infections of HBV and HCV have been decreasing in many EU/EEA countries [Citation7], the burden of HCC and viral cirrhosis is expected to continue increasing. This increase reflects the high HBV and HCV incidence in previous decades [Citation24,Citation31] as well as immigration of individuals with hepatitis B and C from countries of intermediate or high endemicity [Citation22,Citation27,Citation28], which has resulted in a large number of infected individuals who are mostly undiagnosed. Whilst it was estimated that in 2017, some European countries had reached an estimated quarter of infected patients with DAAs [Citation16], the yet to be observed plateau or decreasing trends in end-stage liver diseases could be an indication of the challenge ahead in reducing mortality-associated morbidity to meet the 2030 mortality targets [Citation32]. The aetiology of HCC and liver cirrhosis in the region is heterogeneous, and there is evidence of persisting risk of HCC after viral clearance among those with advanced liver disease and pre-existing risk factors for liver disease [Citation29]. To operationalise timely management of HCV, HBV, as well as co-infections and co-morbid liver diseases, addressing existing barriers within the cascade of care from prevention, testing, diagnosis to treatment [Citation33] is critical. In parallel, interventions aimed at mitigating the other modifiable risk factors of liver cirrhosis and HCC: alcohol consumption, type 2 diabetes and obesity require concerted efforts. Viral hepatitis and alcohol combined, are the underlying cause for most of the liver disease burden in the EU/EEA [Citation7]. However, the prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in Europe is estimated to be between 2 to 44% among the general population, and up to about 70% in type 2 diabetes patients [Citation24] and NAFLD will increasingly contribute to liver disease-associated hospital burden, mortality and healthcare costs, particularly in those countries where obesity and overweight are surging [Citation7].

Conclusion

The present study provides some insight into the substantial hospital burden of HCC and cirrhosis across the EU/EEA in recent years, indicating considerable likely costs to health systems. Trends in the data are challenging to interpret owing to coding limitations and the absence of contextual information on local service provision and care pathways. Available data highlight the need for more robust harmonised data on the viral hepatitis continuum of care, morbidity and mortality to better understand the impact of the epidemic and guide intensified public health action towards elimination of HBV and HCV. In this regard, national level records with cross-linkages between viral hepatitis diagnoses, treatment, hospitalisation and mortality are warranted for further in-depth analyses relating to incidence, mortality and survival.

Author contributions

AON conducted the data management, analyses, interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. ED conceptualised the study, interpreted the results and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors reviewed and approved the final text.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (204 KB)Acknowledgments

Ilze Burkevica and Margarida Domingues de Carvalho at Eurostat who provided data support. Otilia Mårdh at ECDC for reviewing and providing feedback on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy for viral hepatitis 2016–2021. 2016. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_32-en.pdf

- World Health Organization. Global Hepatitis Report 2017 Geneva 2017. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255016/9789241565455-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1081–1088.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic review on hepatitis B and C prevalence in the EU/EEA. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/systematic-review-hepatitis-B-C-prevalence.pdf

- Duarte G, Williams CJ, Vasconcelos P, et al. Capacity to report on mortality attributable to chronic hepatitis B and C infections by Member States: An exercise to monitor progress towards viral hepatitis elimination. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(7):878–882.

- Aspinall EJ, Hutchinson SJ, Goldberg DJ, et al. Monitoring response to hepatitis B and C in EU/EEA: testing policies, availability of data on care cascade and chronic viral hepatitis-related mortality - results from two surveys HIV Med. 2018;19:1:11–15.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. HEPAHEALT Project Report. Risk Factors and the Burden of Liver Disease in Europe and selected Central European countrie [Internet]. 2018. [2018 Sept 8, 2018 Sept 10]. Available from: https://ilc-congress.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/hepahealth/EASL-HEPAHEALTH-Report.pdf

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis B In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2015. 2017. Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/AER_for_2015-hepatitis-B.pdf

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis C In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2015 2017. Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/AER_for_2015-hepatitis-C.pdf

- Eurostat. Database of healthcare. Healthcare activites. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/health/health-care/data/database

- Eurostat. Health care activities (hlth_act). Reference Metadata in Euro SDMX Metadata Structure (ESMS) 2018. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/hlth_act_esms.htm#meta_update1534239524015

- General Equivalence Mappings (GEM). Available from: https://icd10coded.com/convert/?code=5712

- Eurostat/OECD/WHO. International shortlist for hospital morbidity tabulation (ISHMT) 2008 Jan 11; 2018. (Version 2008-11-10). Available from: http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/implementation/hospitaldischarge.htm

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January by age and sex. Available from: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=demo_pjan&lang=en

- Gountas I, Sypsa V, Papatheodoridis G, et al. Economic evaluation of the hepatitis C elimination strategy in Greece in the era of affordable direct-acting antivirals. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(11):1327–1340.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global burden of disease study 2016. Global Health Data Exchange. 2016. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2016

- Pimpin L, Cortez-Pinto H, Negro F, et al. Burden of liver disease in Europe: Epidemiology and analysis of risk factors to identify prevention policies. J Hepatol. 2018;69:718–735.

- Hahne SJ, Veldhuijzen IK, Wiessing L, et al. Infection with hepatitis B and C virus in Europe: a systematic review of prevalence and cost-effectiveness of screening. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:181.

- Silva MJ, Rosa MV, Nogueira PJ, et al. Ten years of hospital admissions for liver cirrhosis in Portugal. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(11):1320–1326.

- Barrachina Martinez I, Giner Duran R, Vivas-Consuelo D, et al. Direct hospitalization costs associated with chronic Hepatitis C in the Valencian Community in 2013. Rev Esp Salud Publica. 2018;92:e201804002.

- Hatzakis A, Chulanov V, Gadano AC, Bergin C, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections with today's treatment paradigm - volume 2. J. Viral Hepat. 2015;22(Suppl 1):26–45.

- Razavi H, Waked I, Sarrazin C, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with today's treatment paradigm. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21 (Suppl 1):34–59.

- Hill LA, Delmonte RJ, Andrews B, et al. Treatment of hepatitis C with direct-acting antivirals significantly reduces liver-related hospitalizations in patients with cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(11):1378–1383.

- Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, et al. Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58(3):593–608.

- EASL. Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):461–511.

- EASL. 2017 Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017;67(2):370–398.

- Falla AM, Ahmad AA, Duffell E, et al. Estimating the scale of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the EU/EEA: a focus on migrants from anti-HCV endemic countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):42.

- Ahmad AA, Falla AM, Duffell E, et al. Estimating the scale of chronic hepatitis B virus infection among migrants in EU/EEA countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):34.

- Public Health England. Hepatitis C in England: 2018 report 2018 08 September 2018. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/693917/HCV_in_England_2018.pdf

- Harris RJ, Thomas B, Griffiths J, et al. Increased uptake and new therapies are needed to avert rising hepatitis C-related end stage liver disease in England: modelling the predicted impact of treatment under different scenarios. J Hepatol. 2014;61(3):530–537.

- Sweeting MJ, De Angelis D, Brant LJ, et al. The burden of hepatitis C in England. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14(8):570–576.

- European Union HCV Collaborators. Hepatitis C virus prevalence and level of intervention required to achieve the WHO targets for elimination in the European Union by 2030: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(5):325–336.

- Marshall AD, Cunningham EB, Nielsen S, et al.; International Network on Hepatitis in Substance Users (INHSU). Restrictions for reimbursement of interferon-free direct-acting antiviral drugs for HCV infection in Europe. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(2):125–133.